Abstract

Heart rate variability (HRV), the variation in intervals between consecutive heartbeats, reflects autonomic nervous system function and has been studied as a potential biomarker in cardiovascular disease (CVD). While reduced HRV has been linked to arrhythmias, heart failure, and ischaemic heart disease, findings across studies are mixed and its prognostic value remains debated. This review evaluates HRV's diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic roles in CVD. HRV can reveal autonomic dysfunction early, predict outcomes such as sudden cardiac death and recurrent myocardial infarction, and track recovery after cardiac events. It also shows promise in monitoring comorbid conditions like heart failure and depression that exacerbate cardiovascular risk. Advancements in wearable technology and machine learning are expanding HRV's potential. Wearable devices enable continuous, non-invasive HRV monitoring, while machine learning algorithms enhance the precision and predictive power of HRV analysis. These innovations may facilitate real-time data collection and tailored treatment plans, though their clinical utility requires validation in larger, prospective trials. Key challenges remain, including measurement variability, lack of standardisation, and limited incremental prognostic value over established risk factors. This review highlights HRV's emerging role in personalised cardiovascular care while acknowledging the substantial research needed before widespread clinical adoption.

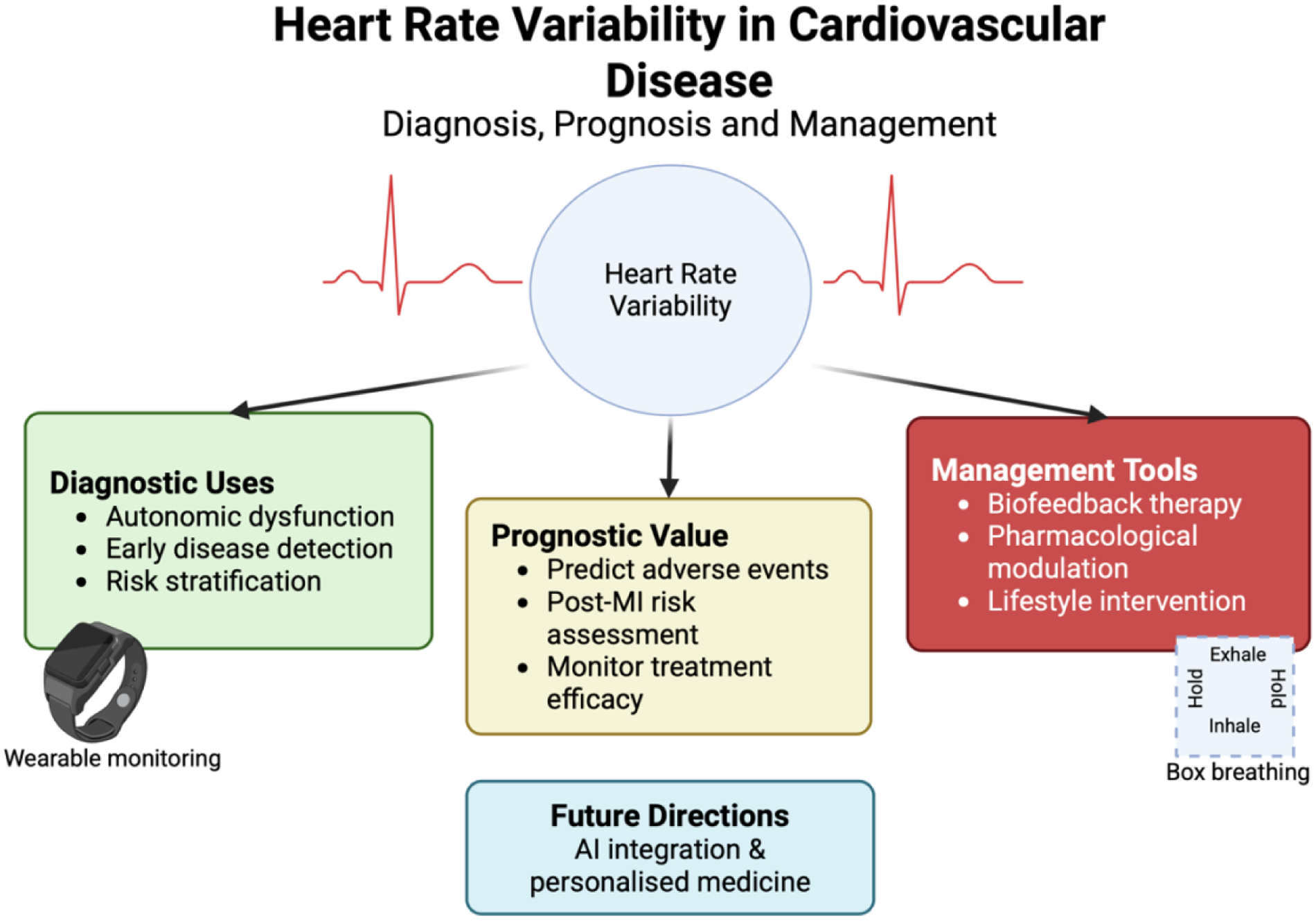

Graphical Abstract

Heart rate variability (HRV) in cardiovascular disease. HRV reflects autonomic regulation of cardiac function and has been studied across three clinical domains: diagnostic applications (autonomic dysfunction, early disease detection, risk stratification), prognostic value (prediction of adverse events, post–myocardial infarction risk, treatment monitoring), and management tools (biofeedback therapy, pharmacological modulation, and lifestyle interventions). Advances in wearable monitoring enable longitudinal HRV assessment, while future directions include artificial intelligence–assisted analysis and personalised medicine. Box breathing is shown as an example of a structured breathing technique used in HRV biofeedback.

1 Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) remain the leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, accounting for over 20 million deaths annually (1). Early detection, risk stratification, and effective management are critical in reducing its health and economic burden. Heart rate variability (HRV) has been studied as a biomarker linking autonomic nervous system (ANS) regulation and cardiovascular health. However, its role remains under investigation, as associations are not always consistent and may attenuate when adjusted for conventional risk factors.

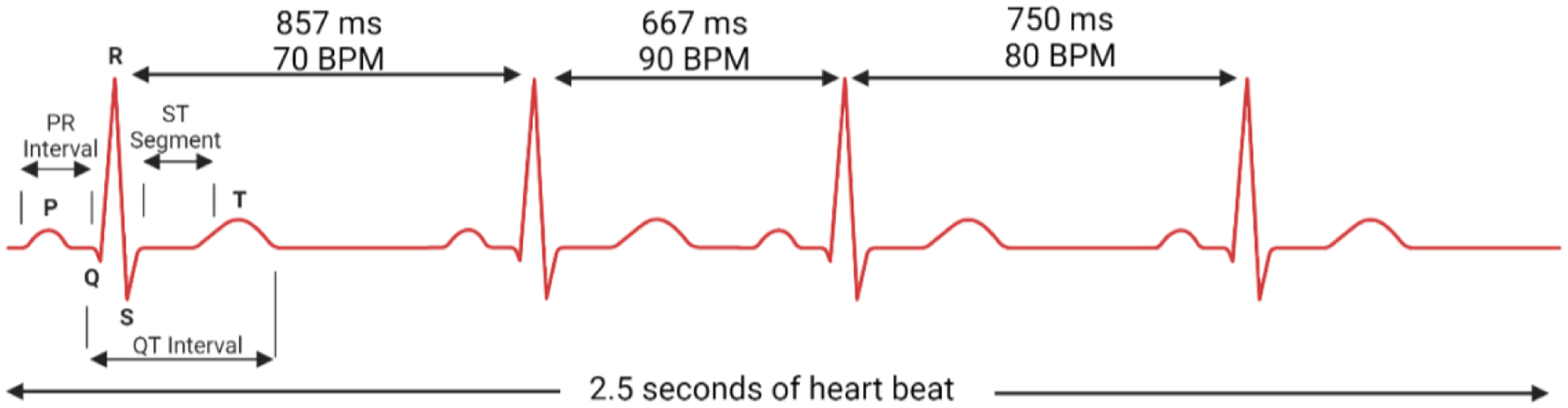

HRV is defined as the temporal variation between consecutive heartbeats, often measured as R-R intervals on an electrocardiogram (ECG) (Figure 1) (2). One key component of HRV is respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA)—whereby heart rate increases during inspiration and decreases during expiration. RSA is most prominent in young, healthy individuals, reflecting robust autonomic regulation. RSA optimises gas exchange, enhances cardiac efficiency, and stabilises blood pressure (3–5). However, in CVD, RSA is often diminished or lost, indicating autonomic dysfunction (6).

Figure 1

Heart rate variability visualised with R-R interval changes.

The aim of this review is to provide a structure and balanced synthesis of the role of HRV in cardiovascular disease. We review HRV domains and their clinical applications, evaluate evidence across disease context, and highlight challenges, inconsistencies, and future directions.

2 Methods

We constructed a structured literature search to inform this narrative review. Searches were performed in Pubmed databases between January 1980 and December 2024, supplemented by manual screening of reference lists and relevant review articles.

Search strategy: We used combinations of the terms “heart rate variability” OR “HRV” AND “cardiovascular disease,” “myocardial infarction,” “heart failure,” “arrhythmia,” “sudden cardiac death,” “autonomic dysfunction,” in the title and abstract fields.

We included studies published in English, assessing HRV (time-, frequency-, or nonlinear-domain measures) in the context of cardiovascular disease, risk stratification, or treatment outcomes. We include observational studies, randomised controlled trials, and meta-analyses. We excluded case reports, conference abstracts, and animal studies unless directly relevant to mechanistic insights. We also excluded studies without clear HRV methodology.

When assessing the evidence, we prioritised large prospective studies, meta-analyses, and studies with 24-hour Holter recordings. Where only short-term (e.g., 5-minute) HRV data were available, this is explicitly noted. This structured approach aimed to minimise selection bias while acknowledging that the review is narrative rather than systematic.

3 HRV metrics and analytical domains

HRV can be assessed using three principal approaches: time-domain, frequency-domain, and non-linear methods, each capturing different aspects of autonomic regulation. In this review, “decreased HRV” refers to values below those in age- and sex-matched healthy control populations, or relative declines within individuals over time. Reduced HRV generally reflects diminished vagal modulation. However, some indices can paradoxically increase in settings of sympathetic overactivation or pathological autonomic instability.

3.1 Time-domain measures

Time-domain indices of HRV quantify the variability in the interbeat interval between successive heartbeats (NN intervals) (Table 1). The most widely used include the standard deviation of NN intervals (SDNN), the root mean square of successive differences (RMSSD), and the proportion of adjacent NN intervals differing by >50 ms (pNN50). SDNN is often considered a marker of both sympathetic and parasympathetic influences. RMSSD and pNN50 primarily reflect short-term variability mediated by vagal activity. SDNN from 24-hour Holter recordings consistently predicts mortality after myocardial infarction and in heart failure (7–10).

Table 1

| Parameter | Unit | Description | Change with decreased HRV | Clinical significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR max—HR min | bpm | Average difference between the highest and lowest heart rates during each respiratory cycle. | ↓ | Reflects overall heart rate adaptability; reduced values indicate impaired autonomic regulation |

| pNN50 | % | Percentage of successive RR intervals that differ by more than 50 ms. | ↓ | Indicates parasympathetic activity; lower values suggest reduced vagal tone |

| SDANN | ms | Standard deviation of the average NN intervals for each 5 min segment of a 24 h HRV recording | ↓ | Reflects long-term variability; reduced values indicate impaired circadian rhythm |

| SDNN | ms | Standard deviation of NN intervals. Reflects overall variability. | ↓ | A global measure of HRV; lower values are associated with increased cardiovascular risk |

| SDNN index (SDNNI) | ms | Mean of the standard deviation of all the NN intervals for each 5 min segment of a 24 h HRV recording | ↓ | Similar to SDNN but provides a more granular view of variability over time |

| SDRR | ms | Standard deviation of RR intervals | ↓ | Reflects overall variability; reduced values indicate impaired autonomic regulation |

| RMSSD | ms | Root mean square of successive RR interval differences. Indicates short-term variability and parasympathetic activity. | ↓ | A key marker of vagal tone; lower values suggest reduced parasympathetic values |

Heart rate variability time-domain measures.

Bpm, beats per minute; HRV, heart rate variability; Interbeat interval, time interval between successive heartbeats; NN intervals, interbeat intervals from which artifacts have been removed; RR intervals, interbeat intervals between all successive heartbeats.

3.2 Frequency-domain measures

Frequency-domain measurements decompose HRV into spectral components (Table 2). The high-frequency (HF) band (0.15–4 Hz) reflects parasympathetic modulation and is closely related to respiratory sinus arrhythmia (11). The low-frequency (LF) band (0.04–0.15 Hz) is considered a marker of both sympathetic and parasympathetic input, although its interpretation remans debated (12). The LF/HF ratio has often been used as a proxy for sympathovagal balance, but this view is controversial, as LF is not a pure marker of sympathetic tone (13–16). Very-low-frequency (VLF) and ultra-low-frequency (ULF) bands require long-term recordings and are sensitive to methodological differences, limiting their reproducibility across studies.

Table 2

| Parameter | Unit | Description | Change with decreased HRV | Clinical significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ULF power | ms2 | Absolute power of the ultra-low-frequency band (<0.003 Hz) | ↓ | Reflects very slow oscillations, often linked to thermoregulation and circadian rhythms |

| VLF power | ms2 | Absolute power of the very-low-frequency band (0.0033–0.04 Hz) | ↑ | Associated with sympathetic activity and hormonal regulation; elevated in stress or disease |

| LF peak | Hz | Peak frequency of the low-frequency band (0.04–0.15 Hz) | No change/slight shift to higher frequency | Reflects baroreceptor activity; shifts may indicate autonomic imbalance |

| LF power | ms2 | Absolute power of the low-frequency band (0.04–0.15 Hz). Reflects both sympathetic and parasympathetic influences. | ↑ | Indicates sympathetic dominance when elevated; often associated with stress or heart failure |

| HF peak | Hz | Peak frequency of the high-frequency band (0.15–0.4 Hz). Reflects parasympathetic activity. | No change | Linked to respiratory sinus arrhythmia; stable values suggest preserved vagal tone |

| HF power | ms2 | Absolute power of the high-frequency band (0.15–0.4 Hz) | ↓ | A direct measure of parasympathetic activity; reduced values indicate vagal withdrawal |

| LF/HF | % | Ratio of LF-to-HF power. Often used as an index of sympathovagal balance. | ↑ | Higher values indicate sympathetic dominance; associated with stress, anxiety, or CVD |

Heart rate variability frequency-domain measures and changes typical of decreased heart rate variability.

CVD, cardiovascular disease; HF, high frequency; HRV, heart rate variability; LF, low frequency; ULF, Ultra-low frequency; VLF, very low frequency.

The length of ECG data acquisition influences the reliability of HRV indices. Frequency-domain analysis requires sufficient window sizes: while 5-minute recordings allow reliable estimation of high- and low-frequency power, they cannot resolve VLF or ULF components, which generally require 24-hour Holter monitoring. Similarly, time-domain measures such as SDNN are highly dependent on recording duration. Despite suggestions that as little as 10 s of data may provide HRV estimates, this is not recommended for prognostic use (17, 18). The lack of consensus on the minimum recording duration required for reliable HRV analysis further contributes to heterogeneity across studies (2, 13, 19, 20).

3.3 Non-linear HRV measures

In addition to time- and frequency-domain approaches, non-linear methods have been developed to capture the complex, fractal-like behaviour of heart rate dynamics (21). These techniques are based on the recognition that cardiovascular regulation is not strictly linear, and that traditional indices may overlook subtle patterns of autonomic control.

One of the most common non-linear approaches is the Poincare plot, a scatterplot of each R-R interval against the subsequent time interval (22). From this, two descriptors are derived: SD1, reflecting short-term variability, and SD2, reflecting long-term variability. A reduction in both SD1 and SD2 have been linked to increased cardiovascular mortality (23).

Detrended fluctuation analysis (DFA) is another non-linear approach, which characterises fractal scaling; lower short-term scaling exponent α1 has been associated with sudden cardiac death (SCD) and heart failure mortality (24, 25). Entropy-based measures, such as multiscale entropy, assess signal complexity; lower entropy typically indicates reduced physiological adaptability and has been associated with worse outcomes in patients with heart failure (26).

Together, time, frequency and nonlinear measures form a complementary toolkit. Understanding their distinctions is essential for critically appraising the HRV literature and interpreting results across cardiovascular disease contexts.

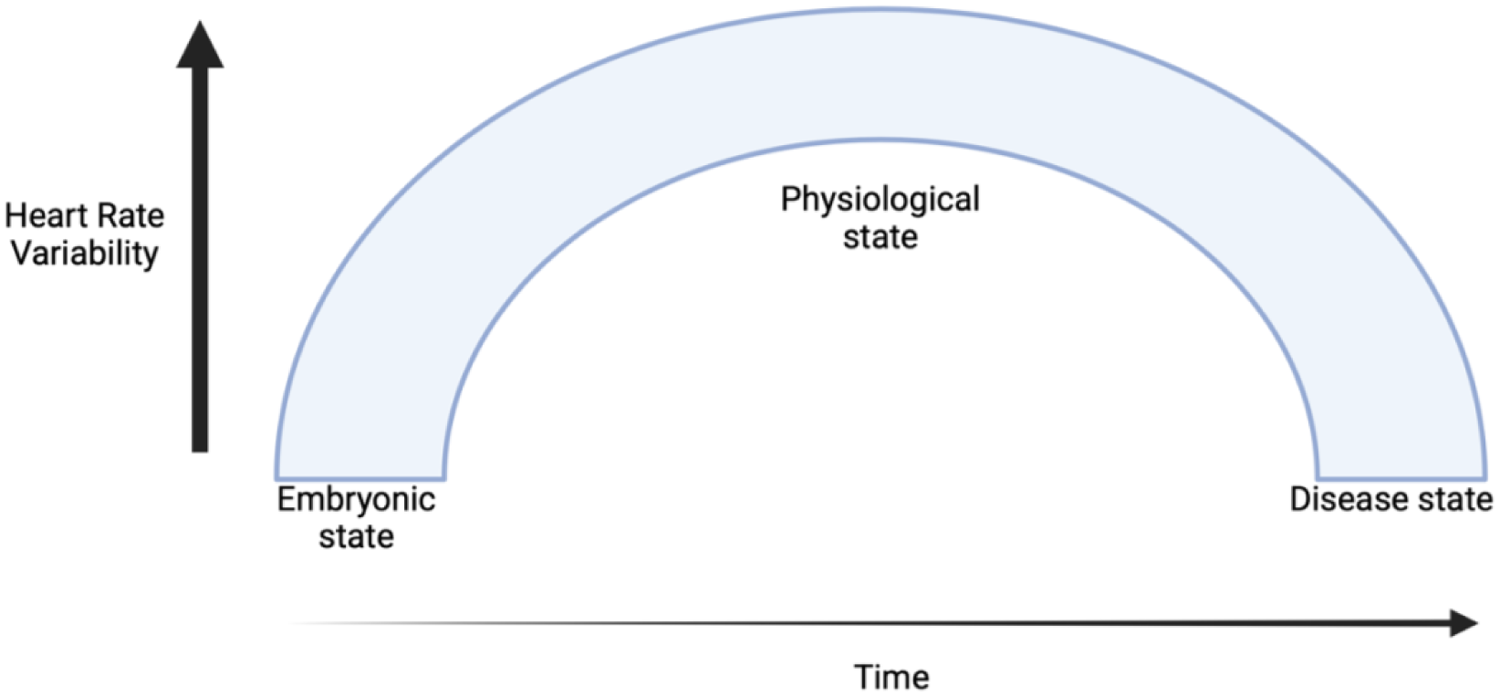

4 Physiological development of HRV

HRV reflects the dynamic balance between the sympathetic and parasympathetic branches of the ANS, which govern the body's cardiovascular responses to internal and external stimuli. The emergence of HRV begins during embryogenesis, when the foetal heart and ANS gradually mature, and reflects early autonomic regulation of cardiovascular function (27). Throughout healthy development, HRV increases, reaching its peak in early adulthood (Figure 2). A healthy ANS demonstrates high variability in R-R intervals. However, in the presence of heart failure, HRV declines, reflecting autonomic dysfunction and predicts increased risk of SCD (28).

Figure 2

Progression of heart rate variability from embryogenesis through healthy development and into disease states. HRV increases during healthy development, peaking in early adulthood, but declines in cardiovascular disease, reflecting autonomic dysfunction and increased cardiovascular risk.

4.1 Clinical thresholds, interpretation and application

Clinical thresholds have been proposed to identify patients at elevated cardiovascular risk. The European Society of Cardiology suggest that SDNN <50 ms represent severely depressed HRV, with <100 ms considered moderately reduced (19). For short-term recordings, RMSSD <15 ms suggests parasympathetic deficiency. However, thresholds vary by age, sex, and recording conditions (29). Importantly, abnormally elevated HRV may represent dysregulated rather than optimised autonomic function. Some studies have observed U-shaped relationships between HRV and outcomes, particularly in elderly populations (30–33).

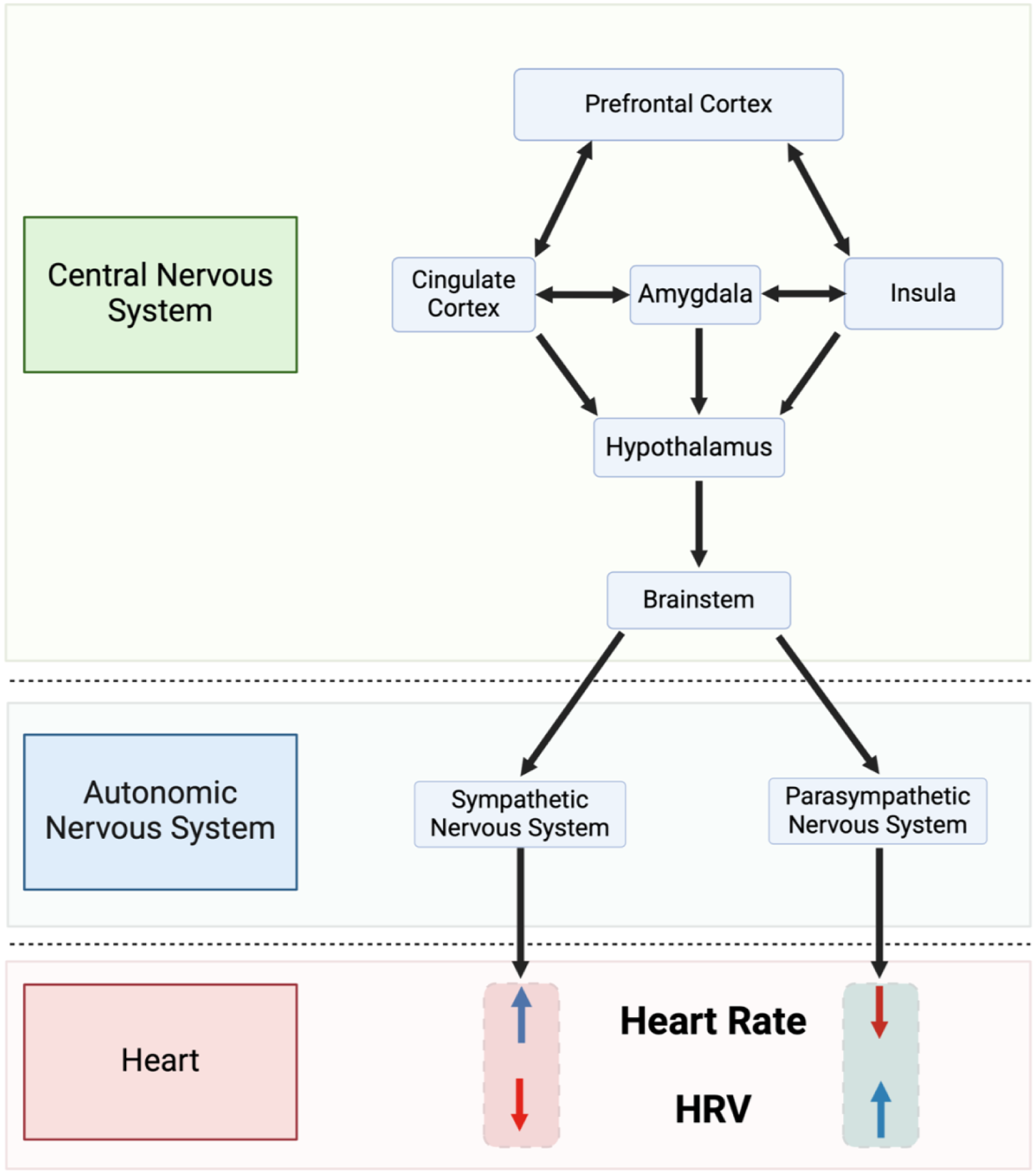

The significance of HRV lies in its ability to serve as a sensitive and early indicator of autonomic dysfunction, often preceding overt clinical manifestations of disease (34). Unlike static measures such as blood pressure or cholesterol levels, HRV captures real-time fluctuations in autonomic activity (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Simplified depiction of the neurovisceral integration model described by thayer and sternberg (35). HRV, heart rate variability.

5 HRV as a diagnostic marker

HRV provides an accessible, non-invasive method to quantify autonomic imbalance, but interpretation assumes intact sinus node function and stable atrioventricular (AV) conduction. In conditions such as sick sinus syndrome, atrial fibrillation (AF), or advanced AV block, variability in R-R intervals no longer reflects autonomic modulation or sinus rhythm. Instead, irregularity may arise from intrinsic nodal dysfunction or arrhythmic events.

5.1 Metabolic dysregulation

Reduced HRV has been associated with metabolic abnormalities. The Toon Health Study (2009–2012) assessed 1,899 individuals without diabetes medication using a 75-gram oral glucose tolerance test and short-term (5-minute) HRV recordings (36). Lower HRV metrics correlated with higher indices of insulin resistance. However, HRV explained only a small proportion of the variance in metabolic outcomes. The study also has broader limitations. The cross-sectional design prevents establishing causality, and the study's homogenous Japanese population limit generalisability. Future longitudinal studies with diverse populations would strengthen these findings and clarify whether HRV changes precede or follow metabolic dysfunction.

5.2 Inflammation

Reduced HRV has also been associated with heightened localised and systemic inflammation, which are recognised contributors to atherosclerosis and other cardiovascular complications (37, 38). First described by Tracey in 2002, the “inflammatory reflex” is a complex of efferent signals in the vagus nerve suppressing macrophage-mediated release of peripheral cytokines in response to inflammatory triggers (39). A meta-analysis by Williams et al. (2019) clarified the relationship between HRV and inflammation, identifying that higher HRV, particularly vagal HRV, was associated with lower levels of inflammation. A maladaptive diminishing of parasympathetic nervous system activity and overactivity of the sympathetic nervous system has been proposed to contribute to a pro-inflammatory state (40).

5.3 Psychological stress and depression

Chronic stress, which disrupts ANS balance, has been linked to both reduced HRV and an increased incidence of CVD (41). A meta-analysis by Kim et al. (2018) surveyed studies that provided a rationale for using HRV as a psychological stress indicator and identified that the most frequently reported factor contributing to changes in HRV variables was a reduction in parasympathetic activity (41). Rebalancing the ANS through vagal stimulation has been shown to limit infarct size and inflammatory response to myocardial ischaemia and reperfusion in male rats that underwent myocardial ischaemia for 30 min and reperfusion for 24 h (42). The anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic properties of the nicotinic pathway were proposed to be the underlying mechanism.

5.4 Electrophysiological disorders

HRV has been explored as a marker of arrhythmic risk. A meta-analysis identified that patients with low HRV without known CVD have a 32%–45% increased risk of a first cardiovascular event, although heterogeneity was substantial and incremental predictive value was unclear (19). Most evidence derives from older cohorts, and relevance in the era of reperfusion and guideline-directed therapy is uncertain.

5.5 Coronary artery disease

Patients with documented CAD exhibit reduced HRV, reflecting altered autonomic regulation of cardiac function. This reduction appears across multiple HRV indices, including time-domain measures and frequency-domain parameters (43, 44). In the ARM-CAD study, there was a linear relationship between CAD severity and LF power, regardless of anatomical location of coronary stenoses (44). Similar findings were reported in Feng et al. (45). Unlike the ARM-CAD study, Feng and colleagues identified that the degree of reduction in time-domain HRVs was dependent on CAD location. The studies did demonstrate that HRV might serve as a non-invasive indicator of disease burden. However, limitations include small sample sizes and short-term recordings, which may limit generalisability.

6 HRV as a prognostic tool

HRV has been studied as a prognostic tool in cardiovascular disease. Reduced variability across time- and frequency-domain indices has been associated with higher risk of mortality, arrhythmias, and recurrent cardiac events. However, findings are inconsistent, and predictive value often diminishes after accounting for conventional risk factors.

6.1 Predicting adverse outcomes

Lower HRV indices have been associated with increased risk stroke, SCD and mortality after an MI (46–48). In patients with diabetes or hypertension, reduced HRV is associated with an increased likelihood of silent myocardial ischaemia (49). In heart failure populations, depressed HRV reflects sympathetic activation and vagal withdrawal and is consistent with arrhythmic death (50). Nonetheless, HRV has not consistently improved risk prediction models beyond established variables. Methodological heterogeneity—retrospective analyses, variable follow-up, and differing HRV protocols—limits comparability.

6.2 Temporal patterns

Beyond average values, emerging evidence suggests that temporal instability in HRV may add prognostic information. In post-MI cohorts, decreased day-to-day stability predicted mortality independent of mean HRV values (51). Similarly, in heart failure, abrupt declines in HRV preceded acute decompensation by several days, suggesting a role for continuous monitoring (52).

6.3 Specific cardiovascular conditions

6.3.1 Post-MI

A study by Zuanetti and colleagues (1996) identified that in patients who received thrombolysis following an MI, reduced values for all time-domain indexes of HRV were predictive for higher risk of mortality (53). More recently, a prospective cohort study by Pukkila et al., (2025) evaluated repeated 24-hour HRV recordings in post-MI patients and found that HRV parameters correlated with infarct severity and left ventricular function, but their independent prognostic value for future cardiac events diminished after adjustment for left ventricular ejection fraction and GRACE score (54). These findings suggest that HRV may complement, rather than replace, established post-MI risk-stratification tools. Supporting this, Karp and colleagues’ (2009) showed that even ultra-short measurements (10 s ECG segments obtained at admission) predicted two-year mortality after MI (55), indicating that brief HRV assessments can still provide meaningful prognostic information.

6.3.2 CAD

HRV has shown prognostic value in patients with CAD. Tsuji and colleagues (1996) analysed ECG recordings from Framingham Heart Study patients who were free of clinically apparent CAD or congestive heart failure to assess the relationship between HRV metrics and the risk of heart disease (56). Lower HRV was associated with an increased risk of a new cardiac event, demonstrating that HRV by ambulatory monitoring offers prognostic information beyond that provided by the evaluation of traditional CVD risk factors.

The prognostic potential of HRV extends to patients undergoing revascularisation procedures. Thanh et al. (2023) investigated the role of pre-operative HRV in predicting AF in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting (57). They found that reduced pre-operative HRV—particularly lower time-domain measures such as SDNN and RMSSD—predicted post-operative AF within 7 days of surgery, but these associations diminished over longer follow-up periods. Frequency-domain components such as HF power, were not predictive. These findings suggest that impaired overall autonomic variability, rather than isolated parasympathetic withdrawal, contributes to post-operative AF risk in the immediate recovery phase.

6.3.3 Ventricular arrhythmias and SCD

Reduced HRV predicts ventricular arrhythmias and SCD in high-risk cohorts. In a prospective study by Galinier and colleagues, 190 patients with chronic heart failure in sinus rhythm were followed for 22 months (58). The study found that a daytime LF power of < 33 ln(ms2) was an independent predictor of SCD, with a relative risk of 2.8. For AF, associations are more complex. Contrary to the linear relationship observed with ventricular arrhythmias, the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) study found that both reduced and excessive HRV parameters increased AF risk, with the highest incidence in individuals at either extreme (59). This finding highlights a broader issue: HRV relationships with outcomes are sometimes U-shaped or paradoxical, complicating interpretation and limiting its reliability as a standalone biomarker.

6.3.4 Congestive heart failure

La Rovere and colleagues (2003) identified that short-term HRV strongly predicted SCD in heart failure patients (28). Specifically, they found that reduced LF power of HRV was associated with an increased risk of SCD, independent of other established risk factors. Beyond SCD, persistently low HRV in heart failure patients is also associated with recurrent hospitalisation (60). This association indicates that deteriorating autonomic function may precede clinical decompensation, potentially providing an opportunity for pre-emptive intervention.

7 Therapeutic contexts

HRV has been explored not only as a biomarker but as a target for therapeutic modulation. Evidence is promising across lifestyle, pharmacological, and device-based interventions, yet findings are inconsistent and clinical translation remains limited.

7.1 Behavioural and lifestyle interventions

Exercise-based interventions have demonstrated benefits in improving HRV. Regular aerobic exercise, such as walking, cycling, or swimming, has been shown to enhance HRV (61). HIIT has been identified as a potential strategy to enhance HRV in post-MI patients. HIIT has been associated with modest improvements in HRV metrics, although the clinical relevance of these findings remains uncertain (62).

Dietary modifications have been associated with differences in autonomic function. In a twin study of 276 men, adherence to a Mediterranean diet was linked with higher HRV across multiple time- and frequency-domain indices, suggesting improved autonomic balance and potentially lower cardiovascular risk (63). Smoking has been associated with blunted vagal modulation and higher sympathetic dominance, reflected by lower SDNN and RMSSD and higher LF/HF ratios in long-term smokers (64). These studies highlight associations between lifestyle factors and HRV; however, they are observational, and causality cannot be inferred.

By providing real-time feedback on autonomic status, HRV monitoring—particularly when integrated into wearable technologies—may help tailor personalised exercise, stress-management and recovery strategies (65, 66). However, it remains unclear whether changes in HRV actively mediate the clinical benefits of these lifestyle interventions ore merely reflect parallel physiological adaptations such as improved metabolic function, reduced inflammation, or enhanced cardiovascular fitness.

7.2 Autonomic modulation therapies

Recent advances in biofeedback therapy, pharmacological agents, and VNS have highlighted the potential benefits of HRV modulation in clinical practice.

7.2.1 Biofeedback therapy

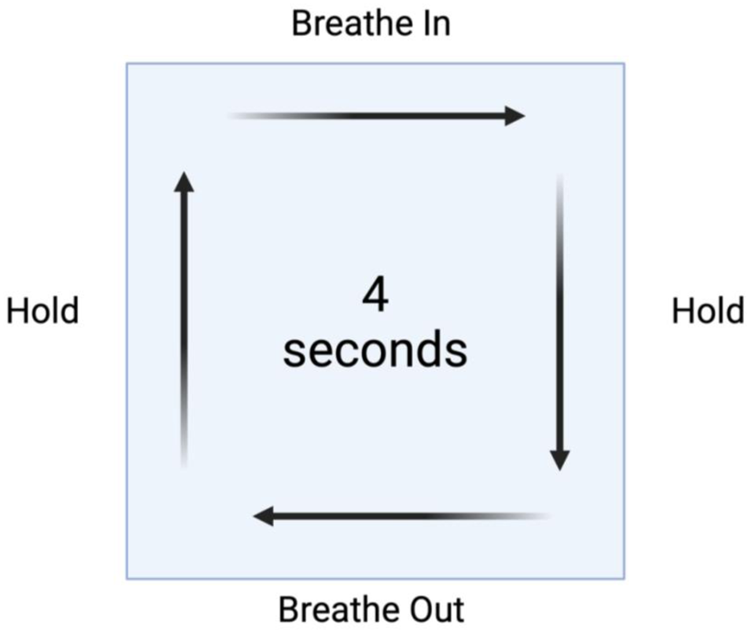

Biofeedback therapy employs real-time physiological feedback to enhance autonomic regulation. HRV biofeedback focuses on synchronising breathing patterns with heart rate to increase parasympathetic activity (67). A common breathing technique used in HRV biofeedback is box breathing (also known as square breathing), which involves inhaling, holding the breath, exhaling, and holding again for equal durations, typically following a 4-4-4-4-second pattern (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Box breathing method for heart rate variability. This method involves inhaling, holding the breath, exhaling, and holding again for equal durations, typically following a 4-4-4-4 s pattern.

Although direct peer-reviewed evidence for box-breathing remains limited, slow-paced breathing at approximately 5–7 breaths per minute has been shown to increase HRV indices such as RMSSD and HF power, reflecting enhanced parasympathetic tone and vagal modulation of HRV (67, 68). Such breathing-based HRV biofeedback interventions have also been associated with improvements in mood and reductions in perceived stress. Paced-breathing techniques are therefore potential tools within HRV biofeedback to promote autonomic balance and psychological wellbeing.

7.2.2 Pharmacological modulation

Pharmacological agents can play a role in modulating HRV by targeting specific autonomic pathways. Beta-blockers have been shown to improved HRV metrics in heart failure patients (69). Similarly, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers have demonstrated efficacy in improving HRV by modulating neurohormonal activity, particularly in patients with heart failure and hypertension (70, 71). These agents decrease systemic inflammation and oxidative stress, through inhibition of reactive oxygen species, CRP and pro-inflammatory interleukins, indirectly contributing to enhanced autonomic regulation (72, 73).

7.2.3 VNS

VNS is a device-based therapy that activates the vagus nerve to enhance parasympathetic output. Preclinical studies in animal models—including in rats and canines—have shown that both invasive (implantable) and non-invasive (transcutaneous) VNS can improve HRV and attenuate cardiac dysfunction (74, 75). A Japanese study in rabbits found that intermittent VNS, but not constant VNS, increased the vagal component of HRV (76). Translation of these findings into human applications remains challenging. The ANTHEM-HF study (2014) showed promising results in humans with heart failure, but the NECTAR-HF trial demonstrated improvements in quality of life without significant effects on cardiac remodelling, highlighting the uncertainties about translation from animal models (77, 78).

7.3 Disease-specific applications

7.3.1 Ventricular arrhythmias and SCD prevention

Pharmacological agents that modulate autonomic tone—particularly beta-blockers—reduce sympathetic activity and improve overall cardiac stability. While these agents have been shown to increase HRV in heart-failure populations, a large meta-analysis of 24,799 patients across 30 randomised control trials attributes the 31% reduction in SCD risk to the drug's direct anti-arrhythmic effect, rather than a proven causal link with HRV improvement (79).

Other autonomic modulation techniques, such as renal denervation and cardiac sympathetic ablation, aim to reduce excessive sympathetic drive that predisposes to arrhythmias (80–82). Evidence of HRV improvement following these procedures is limited, and most data comes from small series or case reports (83, 84). Such interventions illustrate the potential role of therapies that block sympathetic activity in arrhythmia management, though their relationship with HRV changes remain largely theoretical due to limited or absent HRV measurement within these studies.

7.3.2 CAD management

HRV analysis could become an integral component of comprehensive CAD management, informing decisions across the spectrum of care from primary prevention to post-event rehabilitation. In primary prevention, HRV assessment might help identify individuals with subclinical autonomic dysfunction who may benefit from more aggressive risk factor modification. Hillebrand et al. (2013) found that individuals with low HRV had a 32%–45% increased risk of first cardiovascular events, suggesting that HRV could enhance traditional risk stratification models (85). Manresa-Rocamora and colleagues showed that HRV-guided training improves HRV parameters to a greater extent than predefined training in patients with CAD (86). These findings demonstrate that HRV could serve as a valuable surrogate endpoint for assessing the efficacy of rehabilitation interventions.

7.3.3 Congestive heart failure

In heart failure patients, interventions that improve HRV—such as VNS and beta-blockers—have been associated with improved cardiac output (69, 77, 87, 88). These benefits reflect improved baroreflex sensitivity, stabilisation of autonomic control, and enhanced myocardial efficiency. Recent advancements in pacing technology have further highlighted the potential of HRV modulation in heart failure. Shanks et al. (2022) demonstrated the therapeutic benefit of restoring RSA in an ovine model of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (89). The study found that RSA pacing significantly increased cardiac output by 1.4 L/min (20%) compared to conventional monotonic pacing. This improvement was accompanied by a reduction in apnoeas, reversal to cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, and restoration of T-tubule structure, which are critical for force generation in cardiomyocytes. Importantly, the study also observed a decrease in systemic vascular resistance, suggesting that RSA pacing not only enhanced cardiac function but also promotes reverse remodelling.

7.4 Mental health interventions

Depression, anxiety, and chronic stress are associated with autonomic dysregulation and increased CVD risk. HRV serves as a measurable link between psychological and cardiovascular health, offering insights into how mental health interventions influence autonomic balance. A meta-analysis by Pizzoli and colleagues (2021) identified that HRV biofeedback in depressed patients increased HRV levels, closer to that observed in healthy populations, and there was a concomitant improvement in depressive symptoms (90). Biofeedback in combination with usual treatment led to a greater reduction in depression symptoms compared to the group who received only regular treatment. In addition, the group that received biofeedback also showed increased HF HRV during both resting and stress conditions, indicating improved ANS function (91).

Other mental health interventions, such as mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) and cognitive-behavioural therapy, have also demonstrated efficacy in improving HRV in patients with CVD (92, 93). It is thought that MBSR techniques, which involve meditation and focused breathing, enhance parasympathetic activity and reduce sympathetic overdrive (94). Cognitive-behavioural therapy, targets negative thought patterns and behaviours that contribute to stress, driving significant HRV improvements following therapy (92).

8 Challenges and risks associated with HRV modulation

8.1 Patient heterogeneity

The efficacy of interventions like biofeedback or VNS is influenced by baseline autonomic function, age, comorbidities, and psychological health play. Patients with severely impaired autonomic systems or those with chronic conditions like diabetes may not respond as effectively as healthier individuals. Psychological factors such as stress, anxiety or depression can confound HRV outcomes, complicating the interpretation of results and necessitating personalised approaches.

8.2 Methodological variability

The absence of standardised protocols for HRV measurement and intervention adds to the complexity of its application. Inconsistencies in HRV findings across studies often stem from methodological heterogeneity, including differences in data acquisition duration (short-term vs. 24-hour recordings), and in the analytical domain applied (time-, frequency-, or non-linear measures) (2, 13, 66). Furthermore, disparities in the performance of wearable HRV monitors vs. traditional ECG systems contribute to inconsistent reliability, creating barriers for widespread adoption (65, 66). Standardising these protocols is essential for ensuring consistency, reliability, and comparability.

Accurate HRV assessment relies on precise detection of R waves and correct identification of R-R intervals. Signal noise, reduced R-wave amplitude, and ectopic activities such as premature atrial or ventricular contraction can distort variability metrics. Although most analysis software incorporates artefact detection and correction algorithms, these approaches differ in stringency, and residual errors can bias HRV outcomes, particularly in patients with arrhythmias or conduction abnormalities. Transparent reporting of preprocessing steps is therefore essential for reproducibility.

8.3 Limited long-term data

The short-term focus of most studies on HRV modulation presents another limitation. While immediate challenges in HRV indices have been observed following interventions such as biofeedback or VNS, the long-term benefits of these changes remain uncertain. Questions persist regarding the sustainability of improved HRV over months or years, as well as the durability of associated clinical outcomes like reduced hospitalisations or improved quality of life.

Similarly, the long-term safety of some interventions, especially invasive techniques like VNS, remains insufficiently studied. Risks such as nerve damage, infections, or unintended effects on other autonomic functions warrant thorough investigation through longitudinal research. However, non-invasive techniques such as box-breathing are already being integrated into the programming of wearable technology and present a much lower-risk method of integrating HRV modulation techniques into everyday life.

8.4 Potential adverse effects

Potential adverse effects pose risks, even for non-invasive HRV modulation techniques. Although biofeedback therapy is generally safe, some patient(s may experience frustration or dependency when desired HRV improvements are not achieved (95). VNS, whether invasive or transcutaneous, can result in side effects such as dizziness, hoarseness, and, in rare cases, complications from the implantation process (77, 78). Pharmacological interventions that enhance HRV, such as beta-blockers, can cause side effects such as bradycardia, fatigue, or mood disturbances. A careful risk-benefit analysis is therefore essential.

8.5 Ethical and accessibility concerns

Ethical and accessibility concerns also emerge with the increasing reliance on wearable devices and advanced technologies. The high cost of devices and therapy sessions may limit access for underserved populations, exacerbating healthcare disparities. Data privacy is another concern, as wearable HRV monitoring generates large volumes of sensitive health information that could be vulnerable to breaches. Moreover, over-reliance on automated systems for HRV analysis without adequate clinical oversight could result in suboptimal or inappropriate treatment strategies. Equitable healthcare policies, robust cybersecurity measures, and integrated clinical-patient decision-making frameworks are needed to address these issues.

8.6 Technological challenges

Technological challenges further complicate the implementation of HRV modulation. While wearable devices offer convenience, their accuracy in capturing subtle HRV changes often falls short of traditional ECG systems. Machine learning algorithms, which play a significant role in analysing HRV data, may suffer from biases if trained on non-representative datasets. Additionally, achieving real-time therapeutic adjustments based on HRV monitoring is technologically demanding, requiring advanced processing capabilities and seamless device interoperability.

8.6.1 Translational gaps between research and clinical practice

Finally, there is a translational gap between research and clinical practice. Despite evidence supporting HRV modulation, its integration into routine healthcare remains limited. Many clinicians are unfamiliar with HRV metrics and their clinical significance, while resource constraints in healthcare systems hinder the adoption of new technologies. Bridging this gap will require educational initiatives to train clinicians, improved user-friendly devices, and scalable implementation strategies that can be adapted across diverse healthcare settings.

9 Future directions

The exploration of HRV in CVD management has uncovered numerous applications and opportunities. However, several areas warrant further investigation to maximise its potential. These future directions include developing personalised therapeutic protocols, integrating artificial intelligence (AI) and big data, and expanding applications to comorbid conditions.

9.1 Personalised therapeutic protocols

Personalised HRV modulation strategies could integrate genetic, lifestyle, and physiological data to create individualised care plans. Genomic studies could identify polymorphisms influencing autonomic regulation and HRV responsiveness. Combining lifestyle modifications with continuous monitoring may optimise therapeutic outcomes. Furthermore, individual variations in baseline autonomic function and disease progression necessitate adaptive protocols. Tailored biofeedback therapies, pharmacological regimens, or device-based interventions could enhance efficacy while minimising side effects.

For patients with ICDs, there is emerging interest in exploring how HRV metrics might potentially inform device programming strategies. The autonomic information provided by HRV analysis could potentially complement traditional programming approaches, with the goal of reducing inappropriate shocks while maintaining protective efficacy against life-threatening arrhythmias, as well as optimising the individual's quality of life. This area remains largely theoretical and requires robust prospective studies before clinical application but represents a promising direction for research that could ultimately improve patient quality of life without compromising patient safety.

9.2 Integration of AI and big data

Another promising avenue is the integration of AI and big data analytics, which are poised to greatly advance HRV-based interventions. AI can process complex HRV metrics, uncovering patterns that predict disease progression or treatment response. Real-time algorithms could dynamically adjust therapeutic interventions based on HRV trends. By integrating HRV with other biomarkers, predictive models could stratify patients by risk and recommend proactive measures.

9.3 Comorbid conditions

HRV modulation also holds promise beyond primary cardiovascular disorders, particularly in managing conditions where autonomic dysfunction is a key component. Future research should explore its role in diabetes management, where HRV-based interventions could mitigate the progression of diabetic neuropathy and improve glucose regulation. In mental health disorders, HRV-guided therapies, including biofeedback and VNS, may enhance outcomes. The anti-inflammatory effects of enhanced parasympathetic activity suggest a role for HRV modulation in conditions like rheumatoid arthritis and fibromyalgia.

9.4 Long-term and multi-dimensional studies

Expanding HRV applications necessitates robust, long-term studies to validate efficacy across diverse populations and settings. Studies should also assess the synergistic effects of combining HRV modulation with traditional therapies like pharmacological treatments or physical rehabilitation. Moreover, multi-dimensional outcomes, including psychological well-being, systemic inflammation, and healthcare costs, should be evaluated to comprehensively assess the impact of HRV-based strategies.

9.5 Standardisation

The challenges outlined in Section

8of this manuscript highlight a core barrier to HRV's clinical translation: heterogeneity at every stage of acquisition, analysis and interpretation. These inconsistencies make comparison between studies difficult and limit the reliability of HRV as a diagnostic or prognostic tool. Consequently, standardisation is a critical prerequisite for the clinical adoption of HRV analysis. Before any composite “HRV Score” can be considered, the underlying parameters and acquisition methods must be harmonised. Current inconsistencies in recording duration, sampling frequency, and artefact correction significantly affect reproducibility. A valid framework would require standardised criteria for:

- -

Data acquisition—minimum sampling frequency (e.g., >250 Hz), specification of ECG channel configuration, and signal preprocessing protocols including noise filtering and artefact removal.

- -

Analytical consistency—verification of signal stationarity, consistent segment lengths for frequency analysis, and transparent reporting of the algorithms used for spectral decomposition or non-linear metrics.

- -

Patient stratification—definition of population subgroups by age, sex, comorbidities, and medication use to ensure comparability across studies.

Only after these techniques and clinical standards are implemented can a multi-parametric HRV composite score be developed. Such a composite should rely on validated, reproducible metrics weighted according to independently verified prognostic strength. A consensus-driven framework would help ensure that any proposed HRV index or “score” truly reflects physiological reality.

10 Conclusion

The future of HRV in CVD management lies in its integration into personalised, data-driven, and multidisciplinary approaches. By harnessing advances in technology and expanding its applications, HRV may contribute to cardiovascular care as an adjunctive tool. However, its widespread adoption will depend on resolving issues of standardisation, reproducibility, and demonstration of added prognostic value beyond established risk factors.

Statements

Author contributions

BW: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. EB: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. PL: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. AM: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

ACS, acute coronary syndrome; AF, atrial fibrillation; AI, artificial intelligence; ANS, autonomic nervous system; ARM-CAD, alternative risk markers in coronary artery disease; CAD, coronary artery disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; ECG, electrocardiogram; HRV, heart rate variability; HF, high-frequency; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; LF, low-frequency; MBSR, mindfulness-based stress reduction; MI, myocardial infarction; NN50+, number of RR intervals increased >50 ms; RMSSD, root mean square of successive RR interval differences; RSA, respiratory sinus arrhythmia; SCD, sudden cardiac death; SDNN, standard deviation of NN intervals; ULF, ultra-low frequency; VLF, very-low frequency; VNS, vagus nerve stimulation.

References

1.

Lindstrom M DeCleene N Dorsey H Fuster V Johnson CO LeGrand KE et al Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risks collaboration, 1990–2021. JACC. (2022) 80:2372–425. 10.1016/j.jacc.2022.11.001

2.

Shaffer F Ginsberg JP . An overview of heart rate variability metrics and norms. Front Public Health. (2017) 5:258. 10.3389/fpubh.2017.00258

3.

Elstad M Walløe L Holme NLA Maes E Thoresen M . Respiratory sinus arrhythmia stabilizes mean arterial blood pressure at high-frequency interval in healthy humans. Eur J Appl Physiol. (2015) 115:521–30. 10.1007/s00421-014-3042-3

4.

Yasuma F Hayano JI . Respiratory sinus arrhythmia: why does the heartbeat synchronize with respiratory rhythm?Chest. (2004) 125:683–90. 10.1378/chest.125.2.683

5.

Ben-Tal A Shamailov SS Paton JFR . Evaluating the physiological significance of respiratory sinus arrhythmia: looking beyond ventilation-perfusion efficiency. J Physiol. (2012) 590:1989–2008. 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.222422

6.

Hayano J Sakakibara Y Yamada M Ohte N Fujinami T Yokoyama K et al Decreased magnitude of heart rate spectral components in coronary artery disease. Its relation to angiographic severity. Circulation. (1990) 81:1217–24. 10.1161/01.CIR.81.4.1217

7.

Nolan J Batin PD Andrews R Lindsay SJ Brooksby P Mullen M et al Prospective study of heart rate variability and mortality in chronic heart failure results of the United Kingdom heart failure evaluation and assessment of risk trial (UK-heart). Circulation. (1998) 98(15):1510–6. 10.1161/01.CIR.98.15.1510

8.

La Rovere MT Thomas Bigger J Marcus FI Mortara A Schwartz PJ . Baroreflex sensitivity and heart-rate variability in prediction of total cardiac mortality after myocardial infarction. Lancet. (1998) 351:478–84. 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)11144-8

9.

Aronson D Mittleman MA Burger AJ . Measures of heart period variability as predictors of mortality in hospitalized patients with decompensated congestive heart failure. Am J Cardiol. (2004) 93:59–63. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2003.09.013

10.

Singh N Mironov D Armstrong PW Ross AM Langer A . Heart rate variability assessment early after acute myocardial infarction: pathophysiological and prognostic correlates. Circulation. (1996) 93:1388–95. 10.1161/01.CIR.93.7.1388

11.

Grossman P Taylor EW . Toward understanding respiratory sinus arrhythmia: relations to cardiac vagal tone, evolution and biobehavioral functions. Biol Psychol. (2007) 74:263–85. 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2005.11.014

12.

Reyes del Paso GA Langewitz W Mulder LJM van Roon A Duschek S . The utility of low frequency heart rate variability as an index of sympathetic cardiac tone: a review with emphasis on a reanalysis of previous studies. Psychophysiology. (2013) 50:477–87. 10.1111/psyp.12027

13.

Billman GE . The LF/HF ratio does not accurately measure cardiac sympatho-vagal balance. Front Physiol. (2013) 4:26. 10.3389/fphys.2013.00026

14.

Randall DC Brown DR Raisch RM Yingling JD Randall WC Sa WCR . SA nodal parasympathectomy delineates autonomic control of heart rate power spectrum.

15.

Hopf H-B Skyschally A Heusch G Peters J . Low-frequency spectral power of heart rate variability is not a specific marker of cardiac sympathetic modulation. Anesthesiology. (1995) 82:609–19. Available online at:https://journals.lww.com/anesthesiology/fulltext/1995/03000/low_frequency_spectral_power_of_heart_rate.2.aspx10.1097/00000542-199503000-00002

16.

Pagani M Lombardi F Guzzetti S Sandrone G Rimoldi O Malfatto G et al Power spectral density of heart rate variability as an index of sympatho-vagal interaction in normal and hypertensive subjects. J Hypertens Suppl. (1984) 2:S383–5. Available online at:http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/6599685

17.

Krause E Vollmer M Wittfeld K Weihs A Frenzel S Dörr M et al Evaluating heart rate variability with 10 s multichannel electrocardiograms in a large population-based sample. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2023) 10:1144191. 10.3389/fcvm.2023.1144191

18.

Nussinovitch U Politi Elishkevitz K Katz K Nussinovitch M Segev S Volovitz B et al Reliability of ultra-short ECG indices for heart rate variability. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. (2011) 16:117–22. 10.1111/j.1542-474X.2011.00417.x

19.

Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Heart rate variability standards of measurement, physiological interpretation, and clinical use. Circulation. (1996) 93:1043–65. 10.1161/01.CIR.93.5.1043

20.

Bourdillon N Schmitt L Yazdani S Vesin JM Millet GP . Minimal window duration for accurate HRV recording in athletes. Front Neurosci. (2017) 11:456. 10.3389/fnins.2017.00456

21.

Voss BA Schulz S Schroeder R Baumert M Caminal P . Methods derived from nonlinear dynamics for analysing heart rate variability. Philos Trans A Math Phys Eng Sci. (2009) 367:277–96. 10.1098/rsta.2008.0232

22.

Henriques TS Mariani S Burykin A Rodrigues F Silva TF Goldberger AL . Multiscale poincaré plots for visualizing the structure of heartbeat time series. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. (2016) 16:252. 10.1186/s12911-016-0252-0

23.

Kubičková A Kozumplík J Nováková Z Plachý M Jurák P Lipoldová J . Heart rate variability analysed by poincaré plot in patients with metabolic syndrome. J Electrocardiol. (2016) 49:23–8. 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2015.11.004

24.

Mizobuchi A Osawa K Tanaka M Yumoto A Saito H Fuke S . Detrended fluctuation analysis can detect the impairment of heart rate regulation in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Cardiol. (2021) 77:72–8. 10.1016/j.jjcc.2020.07.027

25.

Hernesniemi JA Pukkila T Molkkari M Nikus K Lyytikäinen LP Lehtimäki T et al Prediction of sudden cardiac death with ultra-short-term heart rate fluctuations. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. (2024) 10:2010–20. 10.1016/j.jacep.2024.04.018

26.

Costa M Healey JA . Multiscale entropy analysis of Complex heart rate dynamics: discrimination of age and heart failure effects. Comput Cardiol. (2003) 705–8. Available online at:http://physionet.org10.1109/CIC.2003.1291253

27.

Van Leeuwen P Geue D Lange S Hatzmann W Grönemeyer D . Changes in the frequency power spectrum of fetal heart rate in the course of pregnancy. Prenat Diagn. (2003) 23:909–16. 10.1002/pd.723

28.

La Rovere MT Pinna GD Maestri R Mortara A Capomolla S Febo O et al Short-term heart rate variability strongly predicts sudden cadiac death in chronic heart failure patients. Circulation. (2003) 107:565–70. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000047275.25795.17

29.

Bekenova N Vochshenkova T Aitkaliyev A Imankulova B Turgumbayeva Z Kassiyeva B et al Heart rate variability in relation to cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy among patients at an urban hospital in Kazakhstan. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2024) 21:1653. 10.3390/ijerph21121653

30.

Almeida-Santos MA Barreto-Filho JA Oliveira JLM Reis FP da Cunha Oliveira CC Sousa ACS . Aging, heart rate variability and patterns of autonomic regulation of the heart. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. (2016) 63:1–8. 10.1016/j.archger.2015.11.011

31.

Ogliari G Mahinrad S Stott DJ Jukema JW Mooijaart SP Macfarlane PW et al Resting heart rate, heart rate variability and functional decline in old age. CMAJ. (2015) 187:E442–9. 10.1503/cmaj.150462

32.

Stein PK Barzilay JI Chaves PH Mistretta SQ Domitrovich PP Gottdiener JS et al Novel measures of heart rate variability predict cardiovascular mortality in older adults independent of traditional cardiovascular risk factors: the cardiovascular health study (CHS) novel HRV predicts CV mortality in the elderly. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. (2008) 19:1169–74. 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2008.01232.x

33.

De Bruyne MC Kors JA Hoes AW Klootwijk P Dekker JM Hofman A Van Bemmel JH Grobbee DE . Both Decreased and Increased Heart Rate Variability on the Standard 10-Second Electrocardiogram Predict Cardiac Mortality In the Elderly The Rotterdam Study. Available online at:https://academic.oup.com/aje/article/150/12/1282/53122

34.

Olivieri F Biscetti L Pimpini L Pelliccioni G Sabbatinelli J Giunta S . Heart rate variability and autonomic nervous system imbalance: potential biomarkers and detectable hallmarks of aging and inflammaging. Ageing Res Rev. (2024) 101:102521. 10.1016/j.arr.2024.102521

35.

Thayer JF Sternberg E . Beyond heart rate variability. Ann N Y Acad Sci. (2006) 1088:361–72. 10.1196/annals.1366.014

36.

Saito I Hitsumoto S Maruyama K Nishida W Eguchi E Kato T et al Heart rate variability, insulin resistance, and insulin sensitivity in Japanese adults: the toon health study. J Epidemiol. (2015) 25:583–91. 10.2188/jea.JE20140254

37.

Cooper TM McKinley PS Seeman TE Choo TH Lee S Sloan RP . Heart rate variability predicts levels of inflammatory markers: evidence for the vagal anti-inflammatory pathway. Brain Behav Immun. (2015) 49:94–100. 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.12.017

38.

Williams DP Koenig J Carnevali L Sgoifo A Jarczok MN Sternberg EM et al Heart rate variability and inflammation: a meta-analysis of human studies. Brain Behav Immun. (2019) 80:219–26. 10.1016/j.bbi.2019.03.009

39.

Tracey KJ . The inflammatory reflex. Nature. (2002) 420:853–9. 10.1038/nature01321

40.

Abboud FM . In search of autonomic balance: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. (2010) 298:R1449–67. 10.1152/ajpregu.00130.2010

41.

Kim HG Cheon EJ Bai DS Lee YH Koo BH . Stress and heart rate variability: a meta-analysis and review of the literature. Psychiatry Investig. (2018) 15:235–45. 10.30773/pi.2017.08.17

42.

Calvillo L Vanoli E Andreoli E Besana A Omodeo E Gnecchi M et al Vagal stimulation, through its nicotinic action, limits infarct size and the inflammatory response to myocardial ischemia and reperfusion. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. (2011) 5:500–7. 10.1097/FJC.0b013e31822b7204

43.

Evrengul H Tanriverdi H Kose S Amasyali B Kilic A Celik T Turhan H. The relationship between heart rate recovery and heart rate variability in coronary artery disease. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. (2006) 11:154–62. 10.1111/j.1542-474X.2006.00097.x

44.

Kotecha D New G Flather MD Eccleston D Pepper J Krum H . Five-minute heart rate variability can predict obstructive angiographic coronary disease. Heart. (2012) 98:395–401. 10.1136/heartjnl-2011-300033

45.

Feng J Wang A Gao C Zhang J Chen Z Hou L et al Altered heart rate variability depend on the characteristics of coronary lesions in stable angina pectoris. Anadolu Kardiyol Derg. (2015) 15:496–501. 10.5152/akd.2014.5642

46.

Liu W Xin Y Sun M Liu C Yin X Xu X et al Relationship between heart rate variability traits and stroke: a mendelian randomization study. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. (2025) 34:108251. 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2025.108251

47.

Maheshwari A Norby FL Soliman EZ Adabag S Whitse EA Alonso A et al Low heart rate variability in a 2-minute electrocardiogram recording is associated with an increased risk of sudden cardiac death in the general population: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. PLoS One. (2016) 11:e0161648. 10.1371/journal.pone.0161648

48.

Rueda-Ochoa OL Osorio-Romero LF Sanchez-Mendez LD . Which indices of heart rate variability are the best predictors of mortality after acute myocardial infarction? Meta-analysis of observational studies. J Electrocardiol. (2024) 84:42–8. 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2024.03.006

49.

Kaze AD Fonarow GC Echouffo-Tcheugui JB . Cardiac autonomic dysfunction and risk of silent myocardial infarction among adults with type 2 diabetes. J Am Heart Assoc. (2023) 12:e029814. 10.1161/JAHA.123.029814

50.

Lorvidhaya P Addo K Chodosh A Iyer V Lum J Buxton AE . Sudden cardiac death risk stratification in patients with heart failure. Heart Fail Clin. (2011) 7:157–74. 10.1016/j.hfc.2010.12.001

51.

Akikallio THM¨ Tapanainen JM Tulppo MP Huikuri HV . Clinical applicability of heart rate variability analysis by methods based on nonlinear dynamics. Card Electrophysiol Rev. (2002) 6:250–5. 10.1023/A:1016381025759

52.

van Es VAA van Leunen MMCJ de Lathauwer ILJ Verstappen CCAG Tio RA Spee RF et al Predicting acute decompensated heart failure using circadian markers from heart rate time series. ESC Heart Fail. (2025) 12:4095–107. 10.1002/ehf2.15395

53.

Zuanetti G Neilson JMM Latini R Santoro E Maggioni AP Ewing DJ . Prognostic significance of heart rate variability in post-myocardial infarction patients in the fibrinolytic era: the GISSI-2 results. Circulation. (1996) 94:432–6. 10.1161/01.CIR.94.3.432

54.

Pukkila T Rankinen J Lyytikäinen LP Oksala N Nikus K Räsänen E et al Repeated heart rate variability monitoring after myocardial infraction – cohort profile of the MI-ECG study. IJC Heart and Vasculature. (2025) 57:101619. 10.1016/j.ijcha.2025.101619

55.

Karp E Shiyovich A Zahger D Gilutz H Grosbard A Katz A . Ultra-short-term heart rate variability for early risk stratification following acute st-elevation myocardial infarction. Cardiology. (2009) 114:275–83. 10.1159/000235568

56.

Tsuji H Larson MG Venditti FJ Manders ES Evans JC Feldman CL et al Impact of reduced heart rate variability on risk for cardiac events: the framingham heart study. Circulation. (1996) 94:2850–5. 10.1161/01.CIR.94.11.2850

57.

Thanh N Hien N Son P Pho D Son P . Heart rate variability and its role in predicting atrial fibrillation in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft. Int J Gen Med. (2023) 16:4919–30. 10.2147/ijgm.s435901

58.

Galinier M Pathak A Fourcade J Androdias C Curnier D Varnous S et al Depressed low frequency power of heart rate variability as an independent predictor of sudden death in chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. (2000) 21:475–82. 10.1053/euhj.1999.1875

59.

Habibi M Chahal H Greenland P Guallar E Lima JAC Soliman EZ et al Resting heart rate, short-term heart rate variability and incident atrial fibrillation (from the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA)). Am J Cardiol. (2019) 124:1684–9. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2019.08.025

60.

Hadase M Azuma A Zen K Asada S Kawasaki T Kamitani T et al Very low frequency power of heart rate variability is a powerful predictor of clinical prognosis in patients with congestive heart failure. Circ J. (2004) 68:343–7. 10.1253/circj.68.343

61.

Routledge FS Campbell TS Mcfetridge-Durdle JA Bacon SL . Improvements in heart rate variability with exercise therapy. Can J Cardiol. (2010) 26:303. 10.1016/s0828-282x(10)70395-0

62.

Carrasco-Poyatos M López-Osca R Martínez-González-Moro I Granero-Gallegos A . HRV-guided training vs traditional HIIT training in cardiac rehabilitation: a randomized controlled trial. Geroscience. (2024) 46:2093–106. 10.1007/s11357-023-00951-x

63.

Dai J Lampert R Wilson PW Goldberg J Ziegler TR Vaccarino V . Mediterranean Dietary pattern is associated with improved cardiac autonomic function among middle-aged men: a twin study. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. (2010) 3:366–73. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.905810

64.

Barutcu I Metin A Kaya D Turkmen M Karakaya O Melek M et al Cigarette Smoking and Heart Rate Variability: Dynamic Influence of Parasympathetic and Sympathetic Maneuvers.

65.

Bayoumy K Gaber M Elshafeey A Mhaimeed O Dineen EH Marvel FA et al Smart wearable devices in cardiovascular care: where we are and how to move forward. Nat Rev Cardiol. (2021) 18:581–99. 10.1038/s41569-021-00522-7

66.

Alugubelli N Abuissa H Roka A . Wearable devices for remote monitoring of heart rate and heart rate variability—what we know and what is coming. Sensors. (2022) 22:8903. 10.3390/s22228903

67.

Lalanza JF Lorente S Bullich R García C Losilla JM Capdevila L . Methods for heart rate variability biofeedback (HRVB): a systematic review and guidelines. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. (2023) 48:275–97. 10.1007/s10484-023-09582-6

68.

Meehan ZM Shaffer F . Do Longer exhalations increase HRV during slow-paced breathing?Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. (2024) 49:407–17. 10.1007/s10484-024-09637-2

69.

Pousset F Copie X Lechat P Jaillon P Boissel J-P Hetzel M et al Effects of bisoprolol on heart rate variability in heart failure. Am J Cardiol. (1996) 77:612–7. 10.1016/S0002-9149(97)89316-2

70.

MacIorowska M Krzesiński P Wierzbowski R Gielerak G . Heart rate variability in patients with hypertension: the effect of metabolic syndrome and antihypertensive treatment. Cardiovasc Ther. (2020) 2020:8563135. 10.1155/2020/8563135

71.

Binkley PF Haas GJ Starling RC Nunziata E Hatton PA Leier CV et al Sustained augmentation of parasympathetic tone with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition in patients with congestive heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. (1993) 21:655–61. 10.1016/0735-1097(93)90098-L

72.

Awad K Zaki MM Mohammed M Lewek J Lavie CJ Banach M . Effect of the renin-angiotensin system inhibitors on inflammatory markers: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Mayo Clin Proc. (2022) 97:1808–23. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2022.06.036

73.

Dandona P Dhindsa S Ghanim H Chaudhuri A . Angiotensin II and inflammation: the effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition and angiotensin II receptor blockade. J Hum Hypertens. (2007) 21:20–7. 10.1038/sj.jhh.1002101

74.

Annoni E Tolkacheva E. Acute Hemodynamic Effects of Vagus Nerve Stimulation in Conscious Hypertensive Rats. (2018). 10.0/Linux-x86_64

75.

Zhang Y Popović ZB Bibevski S Fakhry I Sica DA Van Wagoner DR et al Chronic vagus nerve stimulation improves autonomic control and attenuates systemic inflammation and heart failure progression in a canine high-rate pacing model. Circ Heart Fail. (2009) 2:692–9. 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.873968

76.

Iwao T Yonemochi H Nakagawa M Takahashi N Saikawa T Ito M . Effect of constant and intermittent vagal stimulation on the heart rate and heart rate variability in rabbits. Jpn J Physiol. (2000) 50:33–9. 10.2170/jjphysiol.50.33

77.

Premchand RK Sharma K Mittal S Monteiro R Dixit S Libbus I et al Autonomic regulation therapy via left or right cervical vagus nerve stimulation in patients with chronic heart failure: results of the ANTHEM-HF trial. J Card Fail. (2014) 20:808–16. 10.1016/j.cardfail.2014.08.009

78.

Zannad F De Ferrari GM Tuinenburg AE Wright D Brugada J Butter C et al Chronic vagal stimulation for the treatment of low ejection fraction heart failure: results of the NEural cardiac TherApy foR heart failure (NECTAR-HF) randomized controlled trial. Eur Heart J. (2015) 36:425–33. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu345

79.

Al-Gobari M El Khatib C Pillon F Gueyffier F . Beta-blockers for the prevention of sudden cardiac death in heart failure patients: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. (2013) 13:52. 10.1186/1471-2261-13-52

80.

Sharp TE Lefer DJ . Renal denervation to treat heart failure. Annu Rev Physiol. (2021) 83:39–58. 10.1146/annurev-physiol-031620-093431

81.

Fengler K Ewen S Höllriegel R Rommel KP Kulenthiran S Lauder L et al Blood pressure response to main renal artery and combined main renal artery plus branch renal denervation in patients with resistant hypertension. J Am Heart Assoc. (2017) 6:e006196. 10.1161/JAHA.117.006196

82.

Fengler K Höllriegel R Okon T Stiermaier T Rommel KP Blazek S et al Ultrasound-based renal sympathetic denervation for the treatment of therapy-resistant hypertension: a single-center experience. J Hypertens. (2017) 35:1310–7. 10.1097/HJH.0000000000001301

83.

Hayase J Patel J Narayan SM Krummen DE . Percutaneous stellate ganglion block suppressing VT and VF in a patient refractory to VT ablation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. (2013) 24:926–8. 10.1111/jce.12138

84.

Tan AY Abdi S Buxton AE Anter E . Percutaneous stellate ganglia block for acute control of refractory ventricular tachycardia. Heart Rhythm. (2012) 9:2063–7. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2012.07.030

85.

Hillebrand S Gast KB De Mutsert R Swenne CA Jukema JW Middeldorp S et al Heart rate variability and first cardiovascular event in populations without known cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis and dose-response meta-regression. Europace. (2013) 15:742–9. 10.1093/europace/eus341

86.

Manresa-Rocamora A Sarabia JM Guillen-Garcia S Pérez-Berbel P Miralles-Vicedo B Roche E et al Heart rate variability-guided training for improving mortality predictors in patients with coronary artery disease. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:10463. 10.3390/ijerph191710463

87.

De Ferrari GM Crijns HJGM Borggrefe M Milasinovic G Smid J Zabel M et al Chronic vagus nerve stimulation: a new and promising therapeutic approach for chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. (2011) 32:847–55. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq391

88.

Lin JL Chan HL Du CC Lin IN Lai CW Lin KT et al Long-term β-blocker therapy improves autonomic nervous regulation in advanced congestive heart failure: a longitudinal heart rate variability study. Am Heart J. (1999) 137:658–65. 10.1016/S0002-8703(99)70219-X

89.

Shanks J Abukar Y Lever NA Pachen M LeGrice IJ Crossman DJ et al Reverse re-modelling chronic heart failure by reinstating heart rate variability. Basic Res Cardiol. (2022) 117:4. 10.1007/s00395-022-00911-0

90.

Pizzoli SFM Marzorati C Gatti D Monzani D Mazzocco K Pravettoni G . A meta-analysis on heart rate variability biofeedback and depressive symptoms. Sci Rep. (2021) 11:6650. 10.1038/s41598-021-86149-7

91.

Park SM Jung HY . Respiratory sinus arrhythmia biofeedback alters heart rate variability and default mode network connectivity in major depressive disorder: a preliminary study. Int J Psychophysiol. (2020) 158:225–37. 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2020.10.008

92.

Beresnevaitė M Benetis R Taylor GJ Rašinskienė S Stankus A Kinduris S. Original Research Reports Impact of a Cognitive Behavioral Intervention on Health-Related Quality of Life and General Heart Rate Variability in Patients Following Cardiac Surgery: An Effectiveness Study. Available online at:www.psychosomaticsjournal.org

93.

El-Malahi O Mohajeri D Bäuerle A Mincu R Rothenaicher K Ullrich G et al The effect of stress-reducing interventions on heart rate variability in cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Life. (2024) 14:749. 10.3390/life14060749

94.

Nijjar PS Puppala VK Dickinson O Duval S Duprez D Kreitzer MJ et al Modulation of the autonomic nervous system assessed through heart rate variability by a mindfulness based stress reduction program. Int J Cardiol. (2014) 177:557–9. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.08.116

95.

Jenkins S Cross A Osman H Salim F Lane D Bernieh D et al Effectiveness of biofeedback on blood pressure in patients with hypertension: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hum Hypertens. (2024) 38:719–27. 10.1038/s41371-024-00937-y

Summary

Keywords

cardiovascular disease, heart rate variability, sudden cardiac death, vagus nerve stimulation, wearable device

Citation

Wang BX, Brennand E, Le Page P and Mitchell ARJ (2026) Heart rate variability in cardiovascular disease diagnosis, prognosis and management. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 12:1680783. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1680783

Received

06 August 2025

Revised

09 December 2025

Accepted

22 December 2025

Published

26 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Bo Gregers Winkel, University of Copenhagen, Denmark

Reviewed by

Jesper Mølgaard, University of Copenhagen, Denmark

Thomas Everett, Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Wang, Brennand, Le Page and Mitchell.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Brian Xiangzhi Wang brian.wang1@nhs.net

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.