Abstract

Background:

Limited data are available on clinical characteristics and outcomes in patients with culprit or non-culprit left main coronary artery (LMCA) stenosis between ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and non-STEMI.

Methods:

This study aimed to compare treatment pattern and outcome between STEMI and non-STEMI according to culprit and non-culprit LMCA stenosis. We examined 572 patients with LMCA stenosis from the Korean Acute Myocardial Infarction Registry–National Institute of Health database. Major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) were defined as all-cause death, nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI), repeat revascularization, cerebrovascular accident, rehospitalizations, and stent thrombosis.

Results:

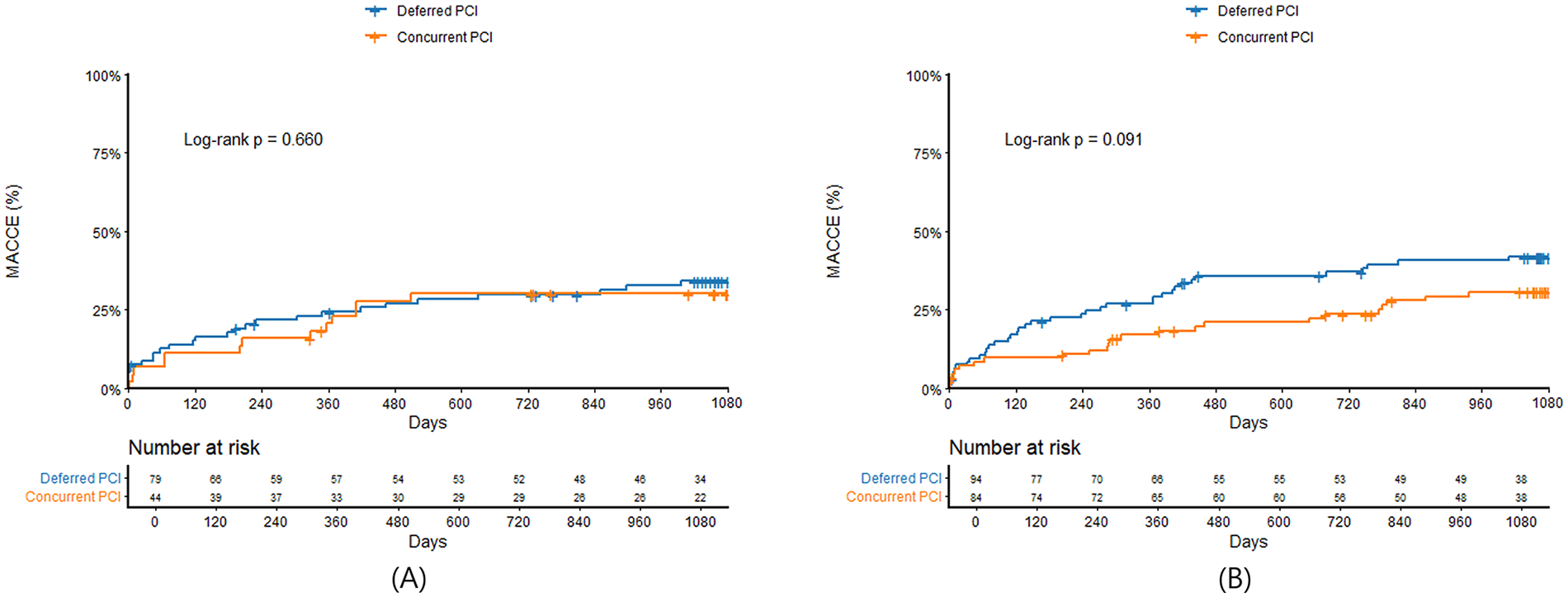

In patients with culprit LMCA stenosis, cardiogenic shock (50.5% vs. 12.1%; P < 0.001) and use of mechanical hemodynamic support (48.5% vs. 11.0%; P < 0.001) were significantly greater in STEMI than in non-STEMI. In-hospital mortality (32.3% vs. 8.1%, P < 0.001) and 3-year MACCE (56.6% vs. 42.2%; log-rank P = 0.003) were significantly higher in STEMI. Intravascular ultrasound improved outcomes of culprit LMCA stenosis (23.1% vs. 68.1%, log-rank P = 0.001). Acute kidney injury, multiple organ failure, and cardiopulmonary resuscitation were independently associated with MACCE in STEMI. In patients with non-culprit LMCA stenosis, there were no significant differences in MACCE between STEMI and non-STEMI (31.3% vs. 34.8%, log-rank P = 0.530). Concurrent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) for non-culprit LMCA stenosis during PCI for other culprit vessel segments did not improve MACCE in STEMI (29.5% vs. 32.9%; log-rank P = 0.660).

Conclusions:

PCI for culprit LMCA stenosis is challenging in both STEMI and non-STEMI despite appropriate mechanical hemodynamic support. Concurrent PCI for non-culprit LMCA stenosis in STEMI does not improve MACCE.

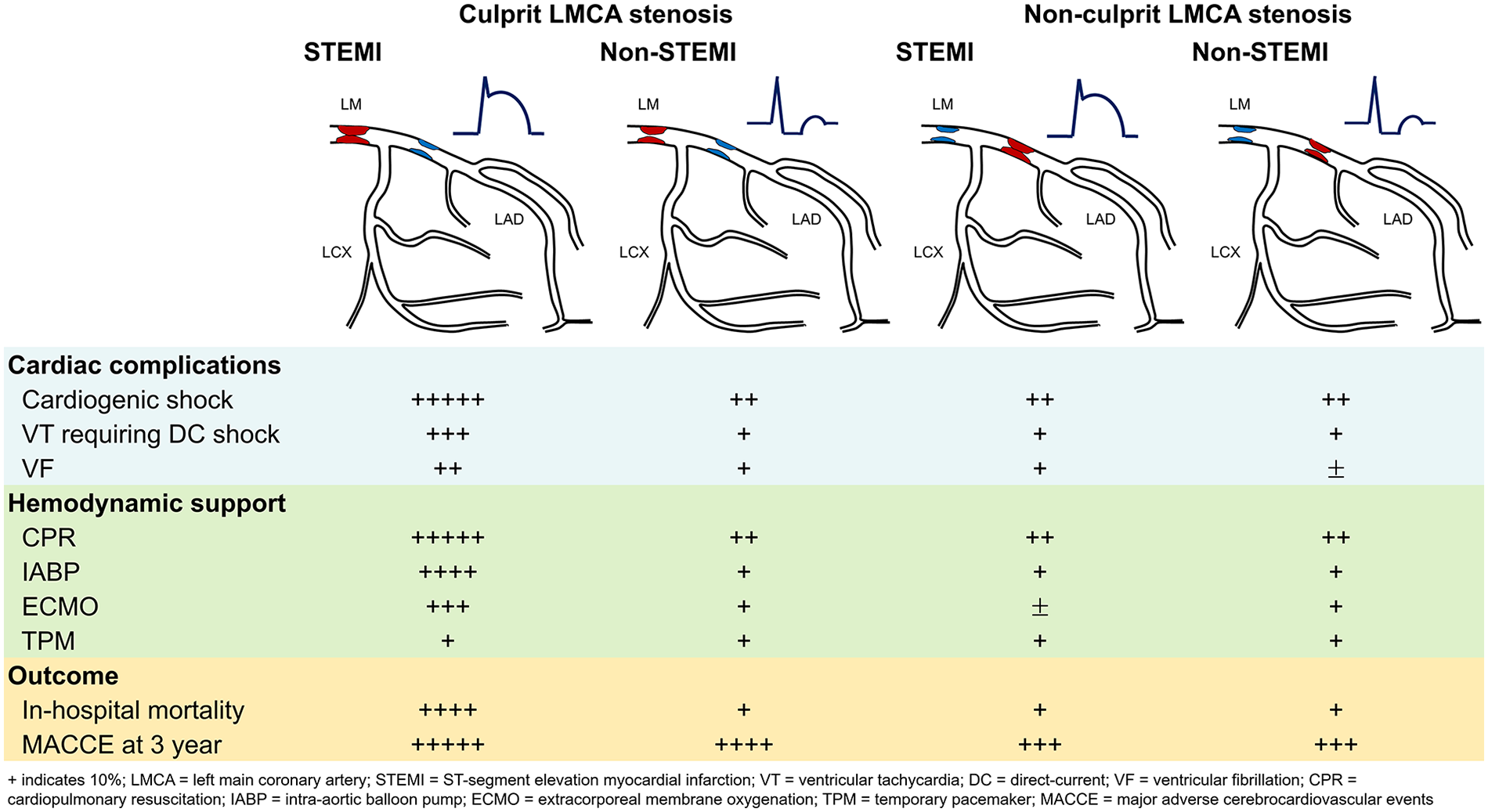

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Advances in interventional techniques have improved the clinical outcome of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) of unprotected left main coronary artery (LMCA) stenosis compared with coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG) (1–5). Therefore, the number of PCI for LMCA stenosis has significantly increased over time. Recently, the guideline for PCI of LMCA has been upgraded from class III to class I in low anatomical complexity or class IIa in intermediate anatomical complexity in the European Society of Cardiology based on the results from a recent randomized controlled trial and meta-analysis (6–8). This indicates that the current guideline regarded PCI as an appropriate alternative to CABG in LMCA stenosis with low to intermediate anatomical complexity. However, in the context of acute myocardial infarction (AMI), PCI for LMCA stenosis is still associated with higher mortality and morbidity rates. Although the benefit of intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) examination has been proven in LMCA stenosis, the use of IVUS is not always possible in hemodynamically unstable patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) or non-STEMI. Moreover, limited data are available about the outcome of concurrent PCI for non-culprit LMCA stenosis at the time of PCI for other culprit vessel segments. Therefore, we aimed to compare treatment pattern and outcome between STEMI and non-STEMI according to culprit and non-culprit LMCA stenosis.

Methods

Study design and patient population

The Korean Acute Myocardial Infarction Registry (KAMIR) is prospective, open, observational, multicenter, online registry of Korean patients with AMI supported by the National Institute of Health (NIH) since November 2011. AMI was diagnosed on the presence of acute myocardial injury detected by abnormal cardiac biomarkers in the setting of evidence of acute myocardial ischemia (9). Other details about KAMIR have been published (10).

All data about patients and procedural details were collected at the time of admission and followed prospectively at each hospital. Data were recorded on a web page-based report form with electronic encryption in the NIH database. This research was supported by a fund (2013-E63005-02) by Research of Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The protocol was approved by the ethics committee of each participating institution, and all patients gave written informed consent to participate in the study.

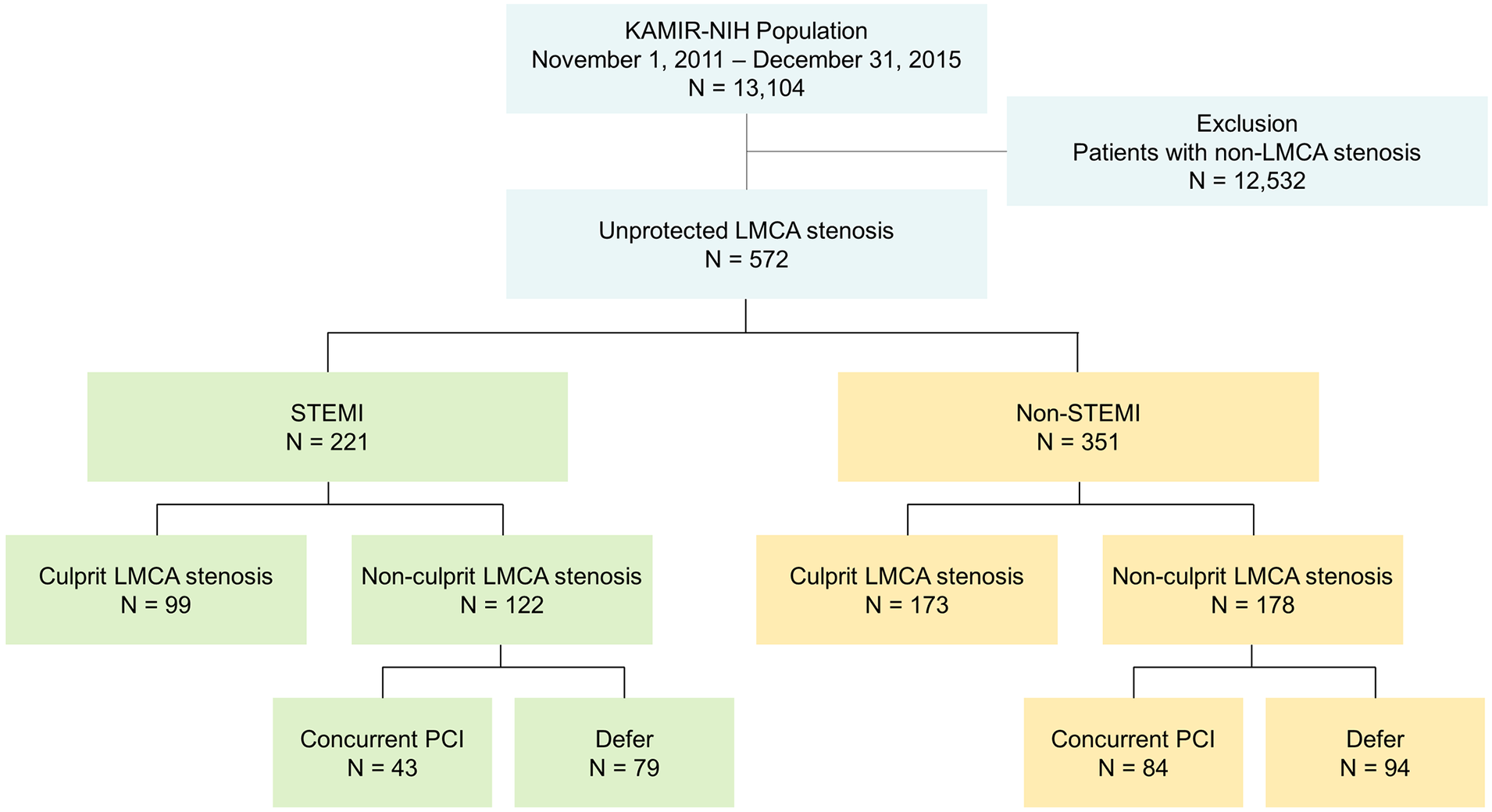

Between November 2011 and December 2015, 13,104 patients (9,686 men; mean age = 64.0 ± 12.6 years old) from 20 PCI centers who were diagnosed with AMI at admission were recruited (Figure 1). Among them, 572 patients with unprotected LMCA stenosis who underwent coronary angiography were finally analyzed in this study. Conceptual categorization of LMCA stenosis is shown in Supplementary Figure S1. A culprit lesion was defined as the lesion involved in the initial AMI, and a non-culprit lesion as any lesion in the entire coronary tree outside the culprit lesion. Culprit lesion was identified based on the findings by a coronary angiography as well as an electrocardiogram and transthoracic echocardiogram. Non-culprit lesion was defined as any lesion with ≥ 50% angiographic stenosis or a fractional flow reserve ≤0.80 in a ≥2.5 mm vessel. In patients with STEMI (n = 221), PCI for LMCA stenosis during index procedure was performed in 142 patients including 99 (44.8%) culprit LMCA stenoses and 43 (19.5%) non-culprit LMCA stenoses. In patients with non-STEMI (n = 351), PCI for LMCA stenosis during index procedure was performed in 257 non-STEMI patients including 173 (49.3%) culprit LMCA stenoses and 84 (23.9%) non-culprit LMCA stenoses. PCI was deferred in 79 (35.7%) non-culprit LMCA stenoses in STEMI and 94 (26.8%) in non-STEMI.

Figure 1

Flow diagram of the study subjects. KAMIR-NIH, Korea Acute Myocardial Infarction Registry-National Institutes of Health registry; LMCA, left main coronary artery; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

All procedures were performed with standard interventional techniques. Access site selection before the diagnostic or therapeutic procedure was at the discretion of the treating physician. Antiplatelet therapy and periprocedural anticoagulation followed the standard regimen. Before the procedure, all patients received a loading dose of aspirin (300 mg) and clopidogrel (300 mg or 600 mg) or prasugrel (60 mg) or ticagrelor (180 mg) at the discretion of the attending physician. In the catheterization laboratory, anticoagulation with a bolus of unfractionated heparin (75–100 U/kg) was administered to achieve an activated clotting time of >300 s. During the procedure, the use of IVUS and/or hemodynamic support such as intra-aortic balloon pump, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, and cardiopulmonary resuscitation was at the operator's discretion. Routine use of post-procedure unfractionated heparin was not recommended except for patients requiring an intra-aortic balloon pump and/or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor inhibitor was left to the discretion of the attending interventional cardiologist. After the procedure, use of guideline-directed medical therapy was mandatory, and the duration of dual antiplatelet agents was at the operator's discretion.

Clinical outcomes

Major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) at 3 years were defined as all-cause death, nonfatal MI, repeat revascularization including repeated PCI and CABG, cerebrovascular accident including both ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke, rehospitalizations defined as all-cause readmissions without restriction to diagnostic category, and stent thrombosis. During the follow-up period, clinical outcome data were obtained by reviewing medical records and interviewing patients by telephone.

Statistical analyses

Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables and as percentages for categorical variables. Comparisons between baseline variables were assessed using Student's t-test for continuous variables and Pearson's chi-squared test for categorical variables. Patients were categorized into culprit LMCA stenosis and non-culprit LMCA stenosis. Baseline characteristics, angiographic and procedural findings, and outcomes were compared between STEMI and non-STEMI according to culprit LMCA stenosis and non-culprit LMCA stenosis. To determine predictors of MACCE, Cox proportional-hazards regression models were used to provide adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Variables with P < 0.05 in univariate analyses such as baseline characteristics including age > 70-year-old, male sex, Killip class > 1, hypertension, complications including atrial fibrillation, acute kidney injury, multi-organ failure, cardiogenic shock, ventricular tachycardia requiring cardioversion, and treatment of complications including cardiopulmonary resuscitation, intra-aortic balloon pump, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation were included in multivariate analysis model. MACCE were compared using Kaplan–Meier survival curves. For all analyses, a two-sided P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS statics (version 30.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and R software (version 4.5.2; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Ethics statement

This study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kyungpook National University School of Medicine (approval No. 2022-01-011) and informed consent was submitted by all patients when they were enrolled.

Results

Baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. Overall, mean age was 67.0 ± 11.6 years old and 448 patients were men. In patients with culprit LMCA stenosis, patients with STEMI had significantly lower systolic blood pressure (P < 0.001), higher Killip class (P < 0.001), higher prevalence of previous angina (P = 0.015), and lower left ventricular ejection fraction (P < 0.001). The use of beta blockers (P = 0.002), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin II receptor blockers (P < 0.001), and statin (P < 0.001) was significantly lower in STEMI compared with non-STEMI. In patients with non-culprit LMCA stenosis, patients with STEMI had significantly lower systolic blood pressure (P = 0.001). The use of clopidogrel (P = 0.017) was lower while the use of ticagrelor (P < 0.001) was greater in STEMI compared with non-STEMI. There was no significant difference in use of dual-antiplatelet therapy between STEMI and non-STEMI in both culprit (P = 0.671) and non-culprit LMCA stenosis (P = 0.569).

Table 1

| Variables | Culprit LMCA stenosis | P value | Non-culprit LMCA stenosis | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STEMI (n = 99) | Non-STEMI (n = 173) | STEMI (n = 122) | Non-STEMI (n = 178) | |||

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age (year) | 65.6 ± 12.4 | 67.0 ± 12.0 | 0.374 | 68.0 ± 11.8 | 67.1 ± 10.6 | 0.538 |

| Male | 81 (81.8%) | 130 (75.2%) | 0.204 | 99 (81.1%) | 138 (77.5%) | 0.450 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.5 ± 3.3 | 23.7 ± 3.3 | 0.638 | 24.2 ± 3.2 | 23.8 ± 3.1 | 0.414 |

| Initial presentation | ||||||

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 97.2 ± 38.8 | 127.9 ± 35.4 | <0.001 | 120.6 ± 30.6 | 133.3 ± 32.6 | 0.001 |

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 83.3 ± 27.7 | 84.5 ± 21.4 | 0.713 | 78.1 ± 20.6 | 82.6 ± 20.6 | 0.061 |

| Killip class >1 | 61 (61.6%) | 56 (32.4%) | <0.001 | 30 (24.6%) | 44 (24.7%) | 0.980 |

| Past medical history | ||||||

| Hypertension | 51 (51.5%) | 93 (53.8%) | 0.722 | 68 (55.7%) | 104 (58.4%) | 0.644 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 37 (37.4%) | 63 (36.4%) | 0.875 | 39 (32.0%) | 69 (38.8%) | 0.228 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 12 (12.1%) | 21 (12.1%) | 0.997 | 13 (10.7%) | 24 (13.5%) | 0.464 |

| Current smoking | 37 (37.4%) | 49 (28.3%) | 0.122 | 36 (29.5%) | 57 (32.0%) | 0.644 |

| Previous MI | 11 (11.1%) | 12 (6.9%) | 0.234 | 15 (12.3%) | 19 (10.7%) | 0.664 |

| Previous angina | 11 (11.3%) | 40 (23.1%) | 0.015 | 13 (10.7%) | 29 (16.3%) | 0.167 |

| LVEF by volume (%) | 40.5 ± 12.0 | 51.6 ± 13.8 | <0.001 | 48.6 ± 11.4 | 50.3 ± 12.6 | 0.260 |

| Medical therapy | ||||||

| Aspirin | 96 (97.0%) | 171 (98.8%) | 0.268 | 120 (98.4%) | 178 (100.0%) | 0.087 |

| Clopidogrel | 75 (75.8%) | 147 (85.0%) | 0.059 | 96 (78.7%) | 158 (88.8%) | 0.017 |

| Prasugrel | 13 (13.1%) | 17 (9.8%) | 0.403 | 14 (11.5%) | 17 (9.6%) | 0.591 |

| Ticagrelor | 21 (21.2%) | 36 (20.8%) | 0.937 | 39 (32.0%) | 24 (13.5%) | <0.001 |

| Dual-Antiplatelet | 96 (97.0%) | 170 (98.3%) | 0.671 | 120 (98.4%) | 177 (99.4%) | 0.569 |

| Beta-blockers | 58 (58.6%) | 133 (76.9%) | 0.002 | 97 (79.5%) | 143 (80.3%) | 0.860 |

| ACE-Is/ARBs | 51 (51.5%) | 130 (75.1%) | <0.001 | 87 (71.3%) | 131 (73.6%) | 0.663 |

| Statins | 64 (64.6%) | 150 (86.7%) | <0.001 | 107 (87.7%) | 162 (91.0%) | 0.355 |

Baseline characteristics of study subjects.

Data expressed as mean ± SD or number (percent).

LMCA, left main coronary artery; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; MI, myocardial infarction; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; ACE-Is, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blockers.

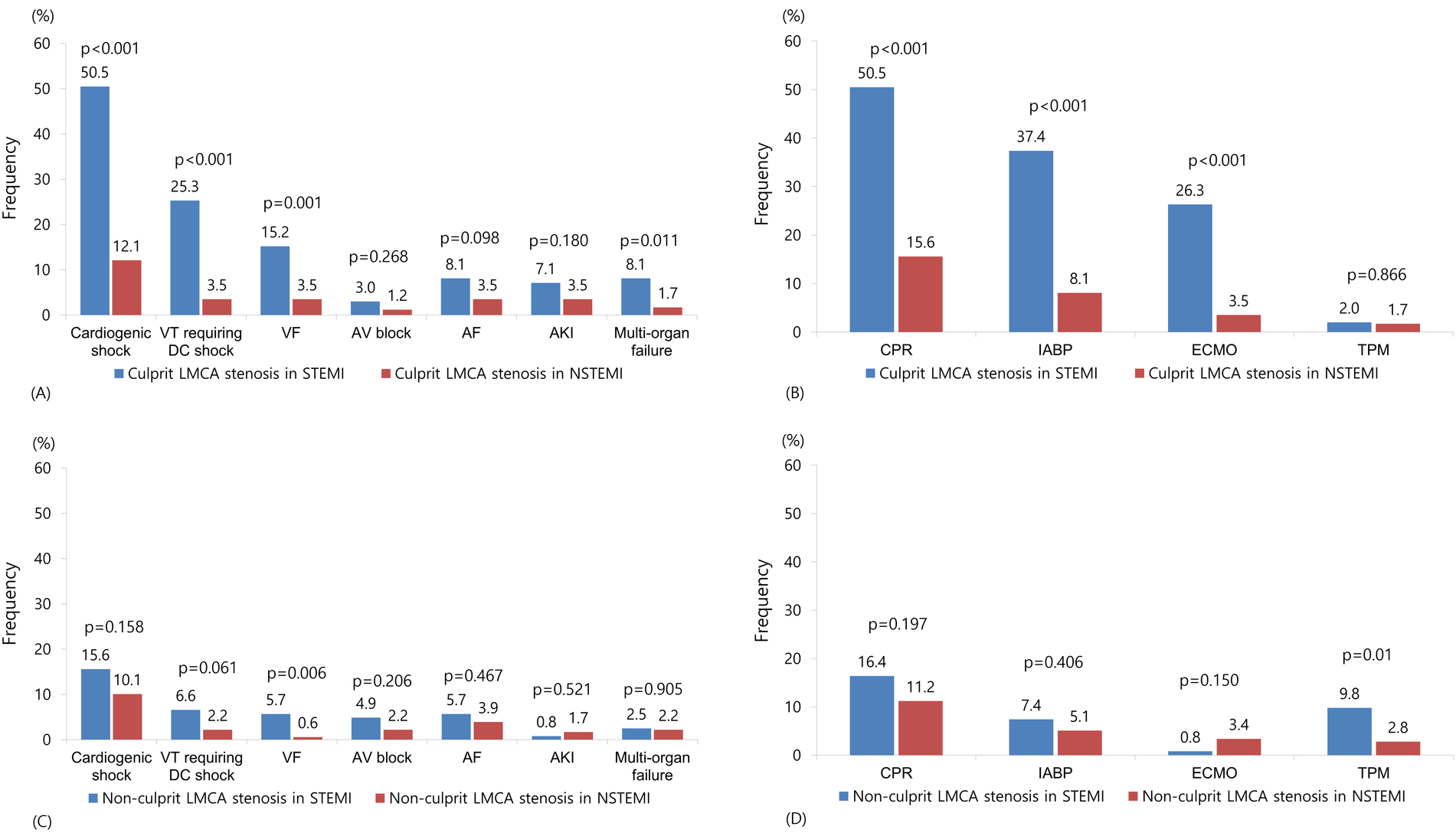

Angiographic and procedural characteristics are summarized in Table 2. In patients with culprit LMCA stenosis, patients with STEMI had significantly lower pre TIMI 0 flow (P < 0.001) and lower post TIMI 3 flow (P = 0.012). IVUS (P < 0.001) was less frequently used in STEMI compared with non-STEMI. Among complications, cardiogenic shock (P < 0.001), ventricular tachycardia requiring cardioversion (P < 0.001), ventricular fibrillation (P = 0.001), and multi-organ failure (P = 0.011) were more frequent in STEMI (Figure 2A). Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (P < 0.001), intra-aortic balloon pump (P < 0.001), and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (P < 0.001) were more frequently used in STEMI (Figure 2B). In patients with non-culprit LMCA stenosis, patients with STEMI had significantly lower pre TIMI 0 flow (P < 0.001) and lower post TIMI 3 flow (P = 0.012). The total number of stents (P = 0.049) and the use of IVUS (P < 0.001) was lower in STEMI compared with non-STEMI. Among complications, ventricular fibrillation (P = 0.006) was more frequent in STEMI (Figure 2C). Temporary pacemaker (P = 0.01) was more frequently used in STEMI (Figure 2D).

Table 2

| Variables | Culprit LMCA stenosis | P value | Non-culprit LMCA stenosis | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STEMI (n = 99) | Non-STEMI (n = 173) | STEMI (n = 122) | Non-STEMI (n = 178) | |||

| No. of diseased vessel | ||||||

| LM isolated (%) | 22 (22.2%) | 33 (19.1%) | 0.534 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | >0.999 |

| LM complex (%) | 77 (77.8%) | 140 (80.9%) | 0.534 | 122 (100.0%) | 178 (100.0%) | >0.999 |

| Lesion type | 0.217 | 0.378 | ||||

| Type A (%) | 2 (2.0%) | 7 (4.0%) | 1 (0.8%) | 4 (2.2%) | ||

| Type B1 (%) | 9 (9.1%) | 18 (10.4%) | 9 (7.4%) | 19 (10.7%) | ||

| Type B2 (%) | 42 (42.4%) | 89 (51.4%) | 32 (26.2%) | 54 (30.3%) | ||

| Type C (%) | 46 (46.5%) | 59 (34.1%) | 80 (65.6%) | 101 (56.7%) | ||

| Pre TIMI 0 (%) | 61 (61.6%) | 163 (94.2%) | <0.001 | 53 (43.4%) | 131 (73.6%) | <0.001 |

| Post TIMI 3 (%) | 90 (90.9%) | 169 (97.7%) | 0.012 | 111 (91.0%) | 172 (96.6%) | 0.038 |

| Stent type | 0.257 | 0.064 | ||||

| BMS (%) | 1 (1.1%) | 1 (0.6%) | 1 (0.9%) | 4 (2.4%) | ||

| EES (%) | 47 (50.5%) | 79 (48.2%) | 71 (64.0%) | 84 (51.2%) | ||

| ZES (%) | 19 (20.4%) | 49 (29.9%) | 15 (13.5%) | 45 (27.4%) | ||

| BES (%) | 11 (11.8%) | 21 (12.8%) | 17 (15.3%) | 22 (13.4%) | ||

| Other DES (%) | 15 (16.1%) | 14 (8.5%) | 7 (6.3%) | 9 (5.5%) | ||

| Stent no. | 1.72 ± 0.93 | 1.86 ± 1.08 | 0.290 | 1.80 ± 1.16 | 2.09 ± 1.33 | 0.049 |

| Stent length (mm) | 23.5 ± 14.9 | 22.9 ± 13.4 | 0.722 | 31.7 ± 19.0 | 31.1 ± 19.2 | 0.790 |

| IVUS (%) | 26 (26.5%) | 88 (52.4%) | <0.001 | 38 (32.2%) | 79 (47.0%) | 0.012 |

Angiographic characteristics of study subjects.

Data expressed as mean ± SD or number (percent).

LMCA, left main coronary artery; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; LM, left main; BMS, bare-metal stent; EES, everolimus eluting stent; ZES, zotarolumus eluting stent; BES, biolimus eluting stent; DES, drug-eluting stent; IVUS, intravascular ultrasound.

Figure 2

Frequency of complications and hemodynamic support in patients with culprit (A,B) or non-culprit (C,D) LMCA stenosis. VT, ventricular tachycardia; DC, direct current; VF, ventricular fibrillation; AV, atrioventricular; AF, atrial fibrillation; AK, acute kidney injury; LMCA, left main coronary artery; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; TPM, temporary pacemaker.

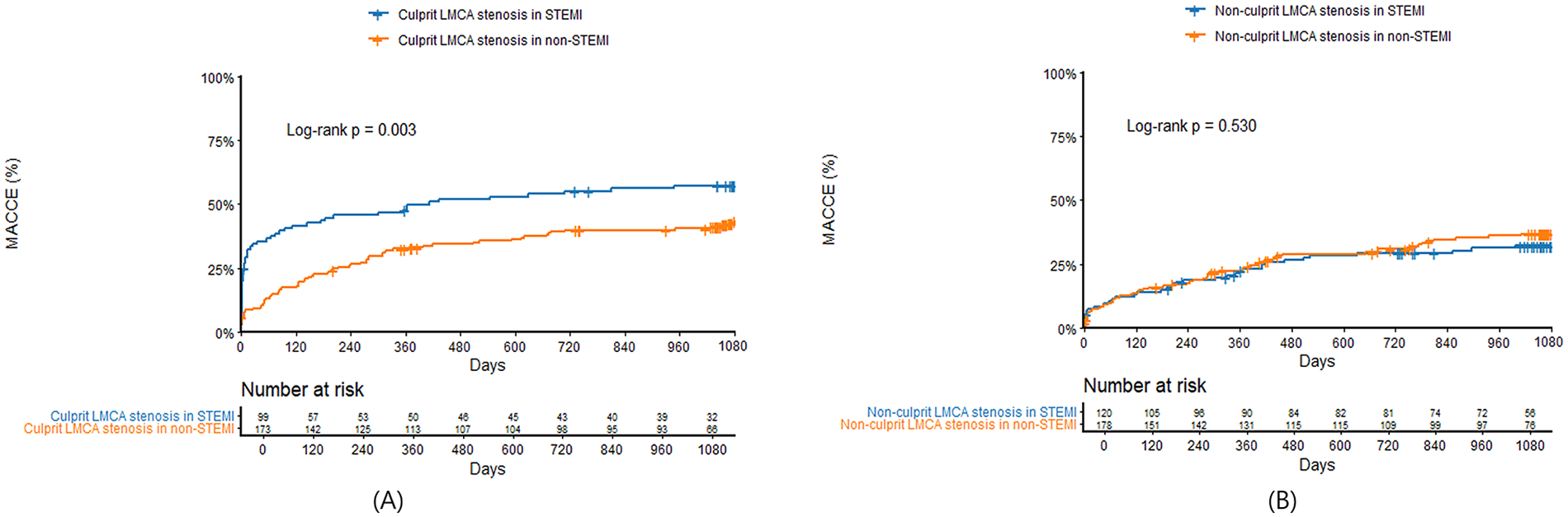

Clinical outcomes were presented in Table 3. In patients with culprit LMCA stenosis, in-hospital mortality was significantly higher in STEMI compared with non-STEMI (32.3% vs. 8.1%, P < 0.001). In landmark analysis at the 30-day time point, MACCE before 30 days were significantly higher in STEMI patients with culprit LMCA stenosis compared with non-STEMI (34.3% vs. 9.2%, log-rank P < 0.001), but there was no significant difference between the two groups after 30 days (25.0% vs. 30.1%, log-rank P = 0.455). MACCE at 3 years was significantly higher in STEMI compared with non-STEMI (56.6% vs. 42.2%, log-rank P = 0.003) (Figure 3A), which was mainly driven by all-cause mortality (43.4% vs. 24.9%, log-rank P < 0.001) and cardiac mortality (38.4% vs. 19.1%, log-rank P < 0.001). In patients with non-culprit LMCA stenosis, there were no significant differences in in-hospital mortality (7.4% vs. 7.3%, P = 0.981) and 3-year MACCE (31.3% vs. 34.8%, log-rank P = 0.530) (Figure 3B) between STEMI and non-STEMI. In subgroup analysis, patients were divided into concurrent PCI during index procedure and deferred PCI for non-culprit LMCA stenosis. Compared with deferred PCI for non-culprit LMCA stenosis, concurrent PCI during index procedure tended to be lower in 3-year MACCE in non-STEMI (28.6% vs. 40.4%; log-rank P = 0.091), but not in STEMI (29.5% vs. 32.9%; log-rank P = 0.660) (Figures 4A,B). There was no significant difference between Figures 4A,B (interaction P = 0.578).

Table 3

| Outcomes | Culprit LMCA stenosis | P value | Non-culprit LMCA stenosis | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STEMI (n = 99) | Non-STEMI (n = 173) | STEMI (n = 122) | Non-STEMI (n = 178) | |||

| Primary outcome | ||||||

| MACCE | 56 (56.6%) | 73 (42.2%) | 0.003 | 38 (31.3%) | 62 (34.8%) | 0.530 |

| Secondary outcome | ||||||

| Death | 43 (43.4%) | 43 (24.9%) | <0.001 | 17 (13.9%) | 26 (14.6%) | 0.580 |

| Cardiac death | 38 (38.4%) | 33 (19.1%) | <0.001 | 13 (10.7%) | 16 (9.0%) | 0.997 |

| Noncardiac death | 5 (5.1%) | 10 (5.8%) | 0.790 | 4 (3.3%) | 10 (5.6%) | 0.347 |

| Nonfatal MI | 5 (5.1%) | 13 (7.5%) | 0.855 | 3 (2.5%) | 11 (6.2%) | 0.129 |

| Revascularization | 10 (10.1%) | 22 (12.7%) | 0.881 | 19 (15.6%) | 34 (19.1%) | 0.385 |

| Repeat PCI | 8 (8.1%) | 19 (11.0%) | 0.957 | 18 (14.8%) | 29 (16.3%) | 0.672 |

| CABG | 2 (2.0%) | 3 (1.7%) | 0.613 | 1 (0.8%) | 5 (2.8%) | 0.233 |

| CVA | 3 (3.0%) | 1 (0.6%) | 0.047 | 1 0.8%) | 1 (0.6%) | 0.813 |

| Rehospitalization | 6 (6.1%) | 14 (8.1%) | 0.881 | 6 (4.9%) | 11 (6.2%) | 0.624 |

| Stent thrombosis | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.6%) | 0.520 | 1 (0.8%) | 1 (0.6%) | 0.793 |

Clinical outcomes of study subjects.

Data expressed as number (percent).

LMCA, left main coronary artery; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; MACCE, major adverse cerebrocardiovascular event; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CVA, cerebrovascular accident.

Figure 3

Kaplan–Meier survival curves comparing 3-year major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events between STEMI and non-STEMI in patients with culprit (A) or non-culprit (B) LMCA stenosis. LMCA, left main coronary artery; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; MACCE, major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Figure 4

Kaplan–Meier survival curves comparing 3-year major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events between concurrent PCI and deferred PCI for non-culprit LMCA stenosis in STEMI (A) and non-STEMI (B) LMCA, left main coronary artery; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; MACCE, major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Cardiac complications, hemodynamic support, and outcomes in patients with culprit or non-culprit LMCA stenosis are summarized in Graphic abstract. The culprit LMCA stenosis in STEMI was an independent predictor of 3-year MACCE (HR 1.83, 95% CI 1.27–2.63; P = 0.001), whereas the non-culprit LMCA stenosis in STEMI (HR 0.85, 95% CI 0.56–1.29; P = 0.462), concomitant PCI of non-culprit LMCA in STEMI (HR 1.03, 95% CI 0.52–2.07; P = 0.914) and non-STEMI (HR 0.66, 95% CI 0.39–1.10; P = 0.112) was not an independent predictor of 3-year MACCE after adjusting for confounding variables. In STEMI patients with culprit LMCA stenosis, acute kidney injury (HR 8.85, 95% CI 2.44–32.11; P = 0.001), multi-organ failure (HR 4.95, 95% CI 1.66–14.72; P = 0.004), and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (HR 2.24, 95% CI 1.02–4.90; P = 0.044) was an independent predictor of 3-year MACCE (Table 4). When IVUS was performed, 3-year MACCE was significantly lower in IVUS users compared with non-IVUS users (33.3% vs. 57.9%, log-rank P < 0.001), particularly in STEMI (23.1% vs. 68.1%, log-rank P < 0.001), but not in non-STEMI (36.4% vs. 48.8%, log-rank P = 0.078) (Supplementary Figure S2). IVUS use was an independent predictor of 3-year MACCE (HR 0.72, 95% CI 0.53–0.98; P = 0.041) after adjusting for confounding variables.

Table 4

| Variables | Hazard ratio | 95% Confidence interval | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline characteristics | |||

| Age >70 year-old | 1.87 | 0.87–3.98 | 0.105 |

| Male | 0.87 | 0.39–1.93 | 0.745 |

| Killip class >1 | 1.73 | 0.83–3.59 | 0.139 |

| Hypertension | 1.49 | 0.78–2.84 | 0.218 |

| Complications | |||

| Atrial fibrillation | 0.35 | 0.11–1.05 | 0.062 |

| Acute kidney injury | 8.85 | 2.44–32.1 | 0.001 |

| Multi-organ failure | 4.95 | 1.66–14.7 | 0.004 |

| VT requiring DC cardioversion | 0.93 | 0.45–1.93 | 0.855 |

| Treatment of complications | |||

| Cardiopulmonary resuscitation | 2.24 | 1.02–4.90 | 0.044 |

| IABP | 0.89 | 0.41–1.92 | 0.767 |

| ECMO | 1.82 | 0.83–3.95 | 0.129 |

Cox proportional-hazards model for 3-year major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events.

VT, ventricular tachycardia; DC, direct current; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

Discussion

The principal findings of this large observational study are as follows. First, although hemodynamic support devices were more frequently used in STEMI, challenging clinical scenarios and events were significantly greater for culprit LMCA stenosis in STEMI than non-STEMI. Second, IVUS improved outcome of culprit LMCA stenosis even in STEMI. Third, in patients with non-culprit LMCA stenosis, there was no significant difference in outcome between STEMI and non-STEMI. Fourth, concurrent PCI for non-culprit LMCA stenosis tended to improve outcome in non-STEMI, but not in STEMI, although this trend was not statistically significant.

To the best of our knowledge, there were only few studies comparing clinical characteristics and outcome of LMCA stenosis between STEMI and non-STEMI according to culprit and non-culprit lesion. Although emergent PCI for LMCA stenosis is still challenging even for an experienced interventional cardiologist, limited data are available on these challenging clinical scenarios. Our study provides comprehensive data for current status of PCI for culprit or non-culprit LMCA stenosis in STEMI and non-STEMI. The most intriguing finding of this study is that clinical events of LMCA stenosis in both STEMI and non-STEMI are significantly higher than those of previously published studies. Previous studies reported in-hospital mortality of about 10% in STEMI and 6%–7% in non-STEMI treated with LMCA stenosis (11–14), compared to 32.3% in-hospital mortality in STEMI and 8.1% in-hospital mortality in non-STEMI treated as culprit LMCA stenosis in our study.

There are several plausible explanations why the mortality rate in our study is higher than previous studies and why our STEMI patients have higher mortality than non-STEMI patients with culprit LMCA stenosis. First, the prevalence of hemodynamically unstable patients is higher in our study. In previous studies, only 8%–12% of STEMI patients who underwent primary PCI for culprit LMCA stenosis had cardiogenic shock or cardiac arrest (11–13). However, cardiogenic shock and cardiopulmonary resuscitation were observed in 50% of our STEMI patients with culprit LMCA stenosis. In addition, cardiogenic shock and life-threatening ventricular arrhythmia was more frequently observed in STEMI compared with non-STEMI. Previous studies reported a 66% prevalence of cardiogenic shock and a 61% in-hospital mortality in patients treated with emergency PCI for LMCA stenosis (15, 16). Furthermore, the use of optimal medical therapy, including beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers, and statins, was significantly lower in patients with STEMI than in those with non-STEMI who had culprit LMCA stenosis, which is thought to be attributable to the higher risk of hemodynamic instability, potential contraindications, and the greater severity of clinical presentation. Optimal medical therapy is well known to improve the prognosis of patients with AMI. Therefore, the lower use of these medications likely contributed to the observed differences in clinical outcomes. These data are in line with our results and explain why our STEMI patients with LMCA stenosis have remarkably high in-hospital mortality and during the follow-up.

Second, severity of LMCA stenosis accompanied by concurrent lesions of other coronary segments may affect outcome. More than 80% of our patients with LMCA stenosis have various degrees of multivessel stenosis in other coronary segment, compared with 40%–60% in other previous reports. The prognosis of patients with LMCA stenosis with additional lesions on other vessel segments is worse than patients with isolated LMCA stenosis. This indicates that LMCA stenosis with widespread pattern of anatomical lesions has more ischemic burden and substrate for ventricular arrhythmia, hence the reason why our study showed a higher cardiac mortality rate than previous studies.

Third, patients with LMCA stenosis usually have a heterogeneous condition. Therefore, various degrees of developing in-hospital noncardiac complications may affect outcome. In our study, developing acute kidney injury and multi-organ failure during hospitalization was a major determinant of clinical outcomes. The prevalence of these complications was significantly higher in STEMI with culprit LMCA stenosis compared with non-STEMI patients. This is another reason why our STEMI patients have higher mortality than non-STEMI patients with culprit LMCA stenosis. Not surprisingly, in patients with non-culprit LMCA stenosis, no significant difference was found in outcome between STEMI and non-STEMI because there was no difference in the prevalence of noncardiac complications and cardiac complications between the two groups.

Another novel finding of our results is that our study provides important data regarding the role of IVUS and multivessel PCI on outcome in AMI patients with LMCA stenosis. First, our analysis supports the use of IVUS in PCI for hemodynamically stable patients with culprit LMCA stenosis even in AMI, as the current guideline recommends IVUS for assessing severity of stable LMCA stenosis (Class IIa) (6, 17–19). However, the role of IVUS in hemodynamically unstable patients remains controversial.

Second, our analysis does not support concurrent PCI of non-culprit LMCA stenosis during the primary PCI for other culprit vessel segments in STEMI. However, interestingly, multivessel PCI including non-culprit LMCA stenosis improved outcome in non-STEMI. The mechanisms of this dichotomy are somewhat unclear. Although other studies showed possible benefit with non-culprit vessel PCI in hemodynamically stable AMI patients (20–23), recent randomized controlled trial showed that multivessel PCI was not better than culprit-only PCI in patients with cardiogenic shock and AMI (24, 25). Therefore, it seems that the high prevalence of cardiogenic shock and ventricular arrhythmia in STEMI patients with non-culprit LMCA stenosis may be at least partially responsible. The current guideline also does not recommend routine PCI of non-culprit lesion during primary PCI in cardiogenic shock (class III).

Our research has several limitations to consider. First, since the KAMIR-NIH was an observational study, we cannot completely exclude the possibility of residual confounding factors. Therefore, our results should only be regarded as hypothesis generating. Second, the choice of PCI for LMCA stenosis was not randomized and left to the operator's best discretion. In addition, PCI strategy for non-culprit lesion and use of hemodynamic support devices were also left to the operator's discretion. Third, we were not able to control unmeasured factors such as individual operator experience, hospital resources, and regional practice variations for treatment choices which may affect outcomes. Therefore, differences in technical skills among each operator may cause bias; hence the results need to be interpreted with caution. Fourth, anatomic complexity such as bifurcation lesions, calcifications and so on may impact treatment decision and outcome. However, anatomic complexity was not controlled in our registry. Furthermore, previous studies have mainly demonstrated short-term outcomes (26), whereas our study provides updated data on 3-year MACCE and independent prognostic factors in STEMI patients with culprit LMCA stenosis. Therefore, the limitations should not undermine the strength of this study that includes overall patient encounters in day-to-day clinical practice.

In conclusion, PCI for culprit LMCA stenosis is still challenging for both STEMI and non-STEMI despite appropriate mechanical hemodynamic support. Clinical events remain high in both culprit and non-culprit LMCA stenosis in STEMI and non-STEMI. Concurrent PCI for non-culprit LMCA stenosis improves outcome in non-STEMI. However, further studies are required regarding the role of concurrent PCI for non-culprit LMCA stenosis during primary PCI for other culprit vessel segments.

Statements

Data availability statement

This study is based on data from The Korean Acute Myocardial Infarction Registry (KAMIR) (https://www.ksmi.re.kr/eng/). The datasets presented in this article are not readily available: the KAMIR database is managed by the central coordinating center, and access to the data is granted to researchers solely for research purposes upon formal request. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to corresponding author (Janghoon Lee, ljhmh75@knu.ac.kr).

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by The Institutional Review Board of Kyungpook National University School of Medicine (approval No. 2022-01-011). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

HK: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Methodology, Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. JL: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration. BP: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. YP: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. JP: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. NK: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. YW: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. DY: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. HP: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. YC: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. MJ: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. J-SP: Investigation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This research was supported by a fund (2013-E63005-02) by Research of Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the contribution of the KAMIR-NIH investigators: Myung Ho Jeong, MD (The lead investigator), Gwangju Veterans Hospital, Gwangju, Republic of Korea, Tae Hoon Ahn, MD, Department of Cardiology, Gil Medical Center, Gachon University College of Medicine, Incheon, Republic of Korea, Ki-Bae Seung, MD, Cardiology Division, Department of Internal Medicine, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Republic of Korea, Chong-Jin Kim, MD, Kyunghee University Hospital at Gangdong, Seoul, Republic of Korea, Shung Chull Chae, MD, Department of Internal Medicine, Kyungpook National University Hospital, Daegu, Republic of Korea, Jin-Yong Hwang, MD, Department of Internal Medicine, Gyeonsang National University School of Medicine, Gyeongsang National University Hospital, Jinju, Republic of Korea, Seung-Ho Hur, MD, Keimyung University Dongsan Medical Center, Cardiovascular Medicine, Deagu, Republic of Korea, SeungWoon Rha, MD, Cardiovascular Center, Korea University Guro Hospital, Seoul, Republic of Korea, Kwang Soo Cha, MD, Pusan National University Hospital, Busan, Republic of Korea, Chang-Hwan Yoon, MD, Cardiovascular Center, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seongnam, Republic of Korea, Hyo-Soo Kim, MD, Cardiovascular Center, Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea, Hyeon-Cheol Gwon, MD, Heart Vascular and Stroke Institute, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea, Jung-Hee Lee, MD, Division of Cardiology, Yeungnam University Medical Center, Yeungnam University College of Medicine, Daegu, Republic of Korea, Seok Kyu Oh, MD, Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Wonkwang University School of Medicine, Iksan, Republic of Korea, Junghan Yoon, MD, Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Yonsei University Wonju College of Medicine, Wonju Severance Christian Hospital, Wonju, Republic of Korea, Jei Keon Chae, MD, Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Chonbuk National University Medical School, Jeonju, Republic of Korea, Seung-Jae Joo, MD, Department of Internal Medicine, Jeju National University College of Medicine, Jeju, Republic of Korea, In-Whan Seong, MD, Department of Internal Medicine, Chungnam National University Hospital, Chungnam National University of Medicine, Daejeon, Republic of Korea, Kyung-Kuk Hwang, MD, Department of Internal Medicine, Chungbuk National University College of Medicine, Chungbuk Regional Cardiovascular Center, Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Chungbuk National University Hospital, Cheongju, Republic of Korea, Doo-Il Kim, MD, Department of Internal Medicine, Inje University College of Medicine, Haeundae Paik hospital, Busan, Republic of Korea.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcvm.2025.1682741/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Figure S1Conceptual categorization of left main coronary artery stenosis of this study. LMCA, left main coronary artery; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

Supplementary Figure S2Kaplan–Meier survival curves for 3-year major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events between IVUS and non-IVUS use for culprit LMCA stenosis in overall (A), STEMI (B), and non-STEMI (C). IVUS, intravascular ultrasound; LMCA, left main coronary artery; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

References

1.

Boudriot E Thiele H Walther T Liebetrau C Boeckstegers P Pohl T et al Randomized comparison of percutaneous coronary intervention with sirolimus-eluting stents versus coronary artery bypass grafting in unprotected left main stem stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2011) 57:538–45. 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.09.038

2.

Brener SJ Galla JM Bryant R III Sabik JF III Ellis SG . Comparison of percutaneous versus surgical revascularization of severe unprotected left main coronary stenosis in matched patients. Am J Cardiol. (2008) 101:169–72. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.08.054

3.

Buszman PE Kiesz SR Bochenek A Peszek-Przybyla E Szkrobka I Debinski M et al Acute and late outcomes of unprotected left main stenting in comparison with surgical revascularization. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2008) 51:538–45. 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.09.054

4.

Chieffo A Magni V Latib A Maisano F Ielasi A Montorfano M et al 5-year outcomes following percutaneous coronary intervention with drug-eluting stent implantation versus coronary artery bypass graft for unprotected left main coronary artery lesions the Milan experience. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. (2010) 3:595–601. 10.1016/j.jcin.2010.03.014

5.

Lee MS Kapoor N Jamal F Czer L Aragon J Forrester J et al Comparison of coronary artery bypass surgery with percutaneous coronary intervention with drug-eluting stents for unprotected left main coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2006) 47:864–70. 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.09.072

6.

Neumann FJ Sousa-Uva M Ahlsson A Alfonso F Banning AP Benedetto U et al ESC scientific document group. 2018 ESC/EACTS guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J. (2019) 40:87–165. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy394

7.

Stone GW Kappetein AP Sabik JF Pocock SJ Morice MC Puskas J et al Five-year outcomes after PCI or CABG for left main coronary disease. N Engl J Med. (2019) 381:1820–30. 10.1056/NEJMoa1909406

8.

Giacoppo D Colleran R Cassese S Frangieh AH Wiebe J Joner M et al Percutaneous coronary intervention vs coronary artery bypass grafting in patients with left main coronary artery stenosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Cardiol. (2017) 2:1079–88. 10.1001/jamacardio.2017.2895

9.

Thygesen K Alpert JS Jaffe AS Chaitman BR Bax JJ Morrow DA et al Fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction (2018). J Am Coll Cardiol. (2018) 72:2231–64. 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.08.1038

10.

Kim JH Chae SC Oh DJ Kim HS Kim YJ Ahn Y et al Multicenter cohort study of acute myocardial infarction in Korea - interim analysis of the Korea acute myocardial infarction registry-national institutes of health registry. Circ J. (2016) 80:1427–36. 10.1253/circj.CJ-16-0061

11.

Pedrazzini GB Radovanovic D Vassalli G Sürder D Moccetti T Eberli F et al Primary percutaneous coronary intervention for unprotected left main disease in patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction the AMIS (acute myocardial infarction in Switzerland) plus registry experience. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. (2011) 4:627–33. 10.1016/j.jcin.2011.04.004

12.

Lee MS Sillano D Latib A Chieffo A Zoccai GB Bhatia R et al Multicenter international registry of unprotected left main coronary artery percutaneous coronary intervention with drug-eluting stents in patients with myocardial infarction. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. (2009) 73:15–21. 10.1002/ccd.21712

13.

Montalescot G Brieger D Eagle KA Anderson FA Jr FitzGerald G Lee MS et al Unprotected left main revascularization in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. (2009) 30:2308–17. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp353

14.

Buszman PP Bochenek A Konkolewska M Trela B Kiesz RS Wilczyński M et al Early and long-term outcomes after surgical and percutaneous myocardial revascularization in patients with non–ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes and unprotected left main disease. J Invasive Cardiol. (2009) 21:564–9.

15.

Hurtado J Bermúdez EP Redondo B Ruiz JL Blanes JRB de Lara JG et al Emergency percutaneous coronary intervention in unprotected left main coronary arteries. Predictors of mortality and impact of cardiogenic shock. Rev Esp Cardiol. (2009) 62:1118–24. 10.1016/s1885-5857(09)73326-2

16.

Jeger RV Radovanovic D Hunziker PR Pfisterer ME Stauffer JC Erne P et al Ten-year trends in the incidence and treatment of cardiogenic shock. Ann Intern Med. (2008) 149:618–26. 10.7326/0003-4819-149-9-200811040-00005

17.

Fassa AA Wagatsuma K Higano ST Mathew V Barsness GW Lennon RJ et al Intravascular ultrasound-guided treatment for angiographically indeterminate left main coronary artery disease: a long-term follow-up study. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2005) 45:204–11. 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.09.066

18.

Park SJ Kim YH Park DW Lee SW Kim WJ Suh J et al Impact of intravascular ultrasound guidance on long-term mortality in stenting for unprotected left main coronary artery stenosis. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. (2009) 2:167–77. 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.108.799494

19.

Hernandez JM Hernandez FH Alfonso F Rumoroso JR Lopez-Palop R Sadaba M et al Prospective application of pre-defined intravascular ultrasound criteria for assessment of intermediate left main coronary artery lesions results from the multicenter LITRO study. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2011) 58:351–8. 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.02.064

20.

Wald DS Morris JK Wald NJ Chase AJ Edwards RJ Hughes LO et al Randomized trial of preventive angioplasty in myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. (2013) 369:1115–23. 10.1056/NEJMoa1305520

21.

Engstrøm T Kelbæk H Helqvist S Høfsten DE Kløvgaard L Holmvang L et al Complete revascularisation versus treatment of the culprit lesion only in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction and multivessel disease (DANAMI-3—pRIMULTI): an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. (2015) 386:665–71. 10.1016/s0140-6736(15)60648-1

22.

Gershlick AH Khan JN Kelly DJ Greenwood JP Sasikaran T Curzen N et al Randomized trial of complete versus lesion-only revascularization in patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention for STEMI and multivessel disease: the CvLPRIT trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2015) 65:963–72. 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.12.038

23.

Mehta SR Wood DA Storey RF Mehran R Bainey KR Nguyen H et al Complete revascularization with multivessel PCI for myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. (2019) 381:1411–21. 10.1056/NEJMoa1907775

24.

Thiele H Akin I Sandri M Fuernau G de Waha S Meyer-Saraei R et al PCI strategies in patients with acute myocardial infarction and cardiogenic shock. N Engl J Med. (2017) 377:2419–32. 10.1056/NEJMoa1710261

25.

Thiele H Akin I Sandri M de Waha-Thiele S Meyer-Saraei R Fuernau G et al One-year outcomes after PCI strategies in cardiogenic shock. N Engl J Med. (2018) 379:1699–710. 10.1056/NEJMoa1808788

26.

Sim DS Ahn Y Jeong MH Kim YJ Chae SC Hong TJ et al Clinical outcome of unprotected left main coronary artery disease in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Int Heart J. (2013) 54:185–91. 10.1536/ihj.54.185

Summary

Keywords

acute myocardial infarction, unprotected left main coronary artery, percutaneous coronary intervention, complete revascularization, prognosis

Citation

Kim HN, Lee JH, Park BE, Park YJ, Park JS, Kim NK, Wi Y, Yang DH, Park HS, Cho Y, Jeong MH and Park J-S (2026) Outcome of contemporary unprotected left main percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 12:1682741. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1682741

Received

09 August 2025

Revised

27 November 2025

Accepted

30 November 2025

Published

09 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Seokhun Yang, Seoul National University Hospital, Republic of Korea

Reviewed by

Seung Hun Lee, Chungnam National University Hospital, Republic of Korea

Sungjoon Park, Seoul National University Hospital, Republic of Korea

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Kim, Lee, Park, Park, Park, Kim, Wi, Yang, Park, Cho, Jeong and Park.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Jang Hoon Lee ljhmh75@knu.ac.kr

ORCID Hong Nyun Kim orcid.org/0000-0002-9903-1848 Jang Hoon Lee orcid.org/0000-0002-7101-0236 Bo Eun Park orcid.org/0000-0002-5245-9863 Yoon Jung Park orcid.org/0000-0001-5132-226X Jong Sung Park orcid.org/0000-0001-8594-5983 Nam Kyun Kim orcid.org/0000-0001-8457-0403 Dong Heon Yang orcid.org/0000-0002-1646-6126 Hun Sik Park orcid.org/0000-0001-7138-1494 Yongkeun Cho orcid.org/0000-0001-9455-0190 Myung Ho Jeong orcid.org/0000-0003-2424-810X Jong-Seon Park orcid.org/0000-0001-5242-2756

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.