Abstract

Introduction:

Sex and advanced age may influence anatomical complexity and clinical outcomes after endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair (EVAR). This study evaluated the impact of sex and age ≥ 80 years on peri-operative and long-term outcomes following EVAR.

Methods:

We conducted a 13-year, single-center retrospective cohort study of 512 patients (311 men, 201 women) who underwent EVAR for infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysm between 2010 and 2023. Patients were stratified by sex and by age (<80 vs. ≥80 years). The primary endpoint was long-term all-cause mortality. Secondary endpoints included perioperative outcomes, Type I endoleak incidence, and reintervention rates. Mortality predictors were assessed using Cox proportional hazards regression. Median follow-up time was 95 months.

Results:

Women and octogenarians had significantly larger aneurysm diameters and greater aortic neck angulation (both p < 0.001). Type I endoleak incidence was significantly higher in women (26.4% vs. 11.9%, p < 0.001) and in patients ≥80 years (32.2% vs. 11.4%, p < 0.001). Cox regression demonstrated that age ≥80 years increased mortality risk 2.43-fold [hazard ratio (HR) = 2.430; 95% confidence interval: 1.430–4.127; p = 0.001], whereas sex was not an independent predictor of mortality (p = 0.185).

Discussion:

Octogenarians exhibited markedly higher mortality risk, and women presented with more challenging vascular anatomy and a higher rate of Type I endoleaks. These findings are consistent with reported anatomical and outcome disparities in high-risk AAA populations.

Conclusion:

These results emphasize that tailored pre-operative planning, device selection, and long-term follow-up strategies may optimise outcomes in elderly and female patients and align with contemporary vascular surgery guidelines.

1 Introduction

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is an irreversible, progressive, and degenerative vascular pathology characterized by enlargement to at least twice the expected transverse diameter for the individual's age and body surface area in any segment of the infradiaphragmatic aorta (1, 2). AAA is one of the leading causes of cardiovascular mortality in the elderly (3). Its prevalence of AAA is significantly increasing, particularly in men aged ≥65 years, with rising diagnosis rates also reported in women (4). Endovascular treatment, a minimally invasive method, has emerged as an alternative to open surgical repair for AAA (5). Age, female sex, complex aneurysm anatomy, and cardiac, pulmonary, and renal comorbidities are associated with higher rates of postoperative complications following AAA treatment (6). Endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) has become an essential option for patients with high perioperative risk because its associated morbidity and mortality are lower than those of conventional treatments (7, 8).

However, evidence suggests that EVAR offers greater benefit in men. Several studies have reported that differences in female vascular anatomy are associated with increased perioperative mortality, higher complication rates, and a greater need for secondary intervention (9–17). In this context, contemporary guidelines, such as the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) 2024 Clinical Practice Guidelines, emphasize nuanced patient selection and long-term surveillance tailored to demographic factors, including sex and advanced age (18).

Despite these findings, few large, contemporary single-center studies have comprehensively evaluated the combined influence of female sex and advanced age (≥80 years) on EVAR outcomes over long-term follow-up. Most available literature focuses on only one demographic factor or relies on database analyses that lack detailed anatomical parameters. Importantly, there is a gap in understanding how the unique anatomical challenges in women (e.g., smaller vessels, greater angulation) interact with the systemic and procedural complexities of octogenarians when both factors coexist. This study aims to address this gap by evaluating the effects of sex and age on outcomes in patients who underwent EVAR for AAA at a single institution over 13 years. The findings may help refine treatment strategies for these patient groups.

2 Materials and methods

We identified 512 patients who underwent EVAR for infrarenal AAA between 2010 and 2023. Of these, 311 were male (60.7%), 201 were female (39.3%), and 152 (29.6%) were aged ≥80 years. The study was approved by the Ordu University Clinical Research Ethics Committee (decision no. 2023/364; 27/12/2023). The cohort included patients with intact infrarenal AAA. Patients with ruptured AAAs were excluded to avoid confounding outcome analyses and to focus on elective cases.

Patients were evaluated for EVAR candidacy based on anatomical criteria determined through preoperative contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) and, when indicated, angiography. Anatomical inclusion was based on the feasibility of standard EVAR device placement in accordance with contemporary vascular surgery guidelines, rather than strict predefined anatomical thresholds. Patients who underwent concurrent visceral interventions or thoracic endovascular aortic repair were excluded.

The choice of endograft devices was guided by evolving surgical preferences and patient anatomy. In total, 204 patients received a Gore Excluder device, and 308 received a Medtronic Endurant device. Radiological images and peri- and post-procedural data were recorded prospectively in an established database and analyzed retrospectively. Informed consent was obtained from all patients before the procedure. This prospective data collection provides a robust foundation and minimizes the limitations associated with purely retrospective data retrieval.

2.1 Endovascular repair technique

EVAR was performed in the angiography unit under general or regional anesthesia in a sterile operating environment. Standard bilateral femoral artery exposure via surgical cutdown was used, and 5,000 units of heparin were administered in accordance with standard device instructions for use.

2.2 Follow-up

After discharge, patients were followed up at 1, 6, and 12 months, and annually thereafter. Follow-up included CT angiography or abdominal color Doppler ultrasonography at each visit to ensure the reliability and validity of the longitudinal assessment. The median follow-up duration was 95 months (range: 2–13 years), providing confidence in the study's comprehensiveness and the reliability of its conclusions.

2.3 Study endpoints

The primary endpoint of this study was long-term all-cause mortality. Secondary endpoints included the following:

- ▪

Perioperative outcomes: operation time and hospital length of stay

- ▪

Aneurysm morphology: aneurysm diameter, aortic neck diameter, neck length, and aortic neck angulation

- ▪

Complication rates: incidence of Type I, II, and III endoleaks

- ▪

Long-term outcomes: need for secondary reinterventions (e.g., balloon angioplasty, bypass, cuff placement)

2.4 Statistical analysis

Before analysis, the dataset was reviewed to identify and correct missing values, errors, and outliers. Descriptive analysis included frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and measures of central tendency (mean, median) and variability (standard deviation, interquartile range) for numerical data. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests were employed to evaluate the normal distribution of the data. Skewness and kurtosis (and their z-scores) were also evaluated. Levene's test was used to verify the homogeneity of variances.

Comparisons between two independent groups were performed using the independent-samples t-test or Mann–Whitney U-test based on parametric assumptions. Associations between categorical variables were examined using the Chi-square test. Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was performed to assess the effects of demographic characteristics and treatment duration on mortality outcomes, with sex, age group, and treatment duration included as predictor variables. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. Variable selection for the multivariate Cox model was guided by the need to maintain a robust model and avoid multicollinearity among anatomical variables (e.g., neck angulation, aneurysm diameter) as well as overfitting due to limited events. This approach improves the generalizability and stability of our main findings. Statistical significance was set at α = 0.05. Analyses were conducted using R (version 4.4.1), IBM SPSS (version 26), and MedCalc (version 21).

3 Results

In the study population, smoking prevalence was significantly higher among males (p < 0.001) and similarly higher in patients under 80 years of age (p = 0.008). All cases presented with AAA, and 90% underwent spinal anesthesia. Hypertension (46.8%) was the most prevalent comorbidity, followed by diabetes mellitus (17.9%) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (15.1%). Comorbidity distribution did not differ significantly across sex or age groups (p > 0.05). Demographic characteristics are presented in Tables 1, 2.

Table 1

| Variable | Gender | Age | Total (N) | Column (%) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | p | <80 | >=80 | p | ||||||||||||

| N | Row | Column | N | Row | Column | N | Row | Column | N | Row | Column | ||||||

| Smoke | Yes | 155 | 85.2 | 49.8 | 27 | 14.8 | 13.4 | <0.001 | 141 | 77.5 | 39.2 | 41 | 22.5 | 27.0 | 0.008 | 182 | 35.5 |

| No | 156 | 47.3 | 50.2 | 174 | 52.7 | 86.6 | 219 | 66.4 | 60.8 | 111 | 33.6 | 73.0 | 330 | 64.5 | |||

| HT | Yes | 170 | 60.7 | 54.7 | 110 | 39.3 | 54.7 | 0.989 | 202 | 72.1 | 56.1 | 78 | 27.9 | 51.3 | 0.319 | 280 | 54.7 |

| No | 141 | 60.8 | 45.3 | 91 | 39.2 | 45.3 | 158 | 68.1 | 43.9 | 74 | 31.9 | 48.7 | 232 | 45.3 | |||

| DM | Yes | 78 | 61.9 | 25.1 | 48 | 38.1 | 23.9 | 0.758 | 87 | 69.0 | 24.2 | 39 | 31.0 | 25.7 | 0.720 | 126 | 24.6 |

| No | 233 | 60.4 | 74.9 | 153 | 39.6 | 76.1 | 273 | 70.7 | 75.8 | 113 | 29.3 | 74.3 | 386 | 75.4 | |||

| COPD | Yes | 51 | 58.6 | 16.4 | 36 | 41.4 | 17.9 | 0.656 | 54 | 62.1 | 15.0 | 33 | 37.9 | 21.7 | 0.065 | 87 | 17.0 |

| No | 260 | 61.2 | 83.6 | 165 | 38.8 | 82.1 | 306 | 72.0 | 85.0 | 119 | 28.0 | 78.3 | 425 | 83.0 | |||

| CAD | Yes | 71 | 64.0 | 22.8 | 40 | 36.0 | 19.9 | 0.432 | 72 | 64.9 | 20.0 | 39 | 35.1 | 25.7 | 0.156 | 111 | 21.7 |

| No | 240 | 59.9 | 77.2 | 161 | 40.1 | 80.1 | 288 | 71.8 | 80.0 | 113 | 28.2 | 74.3 | 401 | 78.3 | |||

| CAS | No | 311 | 60.7 | 100.0 | 201 | 39.3 | 100.0 | NA | 360 | 70.3 | 100.0 | 152 | 29.7 | 100.0 | NA | 512 | 100.0 |

| PAD | Yes | 28 | 80.0 | 9.0 | 7 | 20.0 | 3.5 | 0.016 | 25 | 71.4 | 6.9 | 10 | 28.6 | 6.6 | 0.881 | 35 | 6.8 |

| No | 283 | 59.3 | 91.0 | 194 | 40.7 | 96.5 | 335 | 70.2 | 93.1 | 142 | 29.8 | 93.4 | 477 | 93.2 | |||

| CKD | Yes | 11 | 73.3 | 3.5 | 4 | 26.7 | 2.0 | 0.311 | 13 | 86.7 | 3.6 | 2 | 13.3 | 1.3 | 0.159 | 15 | 2.9 |

| No | 300 | 60.4 | 96.5 | 197 | 39.6 | 98.0 | 347 | 69.8 | 96.4 | 150 | 30.2 | 98.7 | 497 | 97.1 | |||

| Malignancy | No | 311 | 60.7 | 100.0 | 201 | 39.3 | 100.0 | NA | 360 | 70.3 | 100.0 | 152 | 29.7 | 100.0 | NA | 512 | 100.0 |

| CD | Yes | 9 | 52.9 | 2.9 | 8 | 47.1 | 4.0 | 0.503 | 13 | 76.5 | 3.6 | 4 | 23.5 | 2.6 | 0.572 | 17 | 3.3 |

| No | 302 | 61.0 | 97.1 | 193 | 39.0 | 96.0 | 347 | 70.1 | 96.4 | 148 | 29.9 | 97.4 | 495 | 96.7 | |||

| Total | 311 | 60.7 | 100.0 | 201 | 39.3 | 100.0 | 360 | 70.3 | 100.0 | 152 | 29.7 | 100.0 | 512 | 100.0 | |||

Demographic characteristics of the patients (1).

HT, hypertension; DM, diabetes mellitus; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CAD, coronary artery disease; CAS, carotid artery stenosis; PAD, peripheral artery disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CD, cerebrovascular disease; NA, not applicable.

Bold values indicate statistically significant results (p < 0.05).

Table 2

| Variable | Gender | p | Age | p | Total | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | <80 | >=80 | |||||||||||||

| N | Row | Column | N | Row | Column | N | Row | Column | N | Row | Column | |||||

| Type of Anesthesia | General | 30 | 58.8 | 9.6 | 21 | 41.2 | 10.4 | 0.767 | 36 | 70.6 | 10.0 | 15 | 29.4 | 9.9 | 0.964 | 51 |

| Spinal | 281 | 61.0 | 90.4 | 180 | 39.0 | 89.6 | 324 | 70.3 | 90.0 | 137 | 29.7 | 90.1 | 461 | |||

| Iliac Angle | Yes | 90 | 59.2 | 28.9 | 62 | 40.8 | 30.8 | 0.645 | 78 | 51.3 | 21.7 | 74 | 48.7 | 48.7 | <0.001 | 152 |

| No | 221 | 61.4 | 71.1 | 139 | 38.6 | 69.2 | 282 | 78.3 | 78.3 | 78 | 21.7 | 51.3 | 360 | |||

| Endoleak | No | 264 | 65.8 | 84.9 | 137 | 34.2 | 68.2 | <0.001 | 304 | 75.8 | 84.4 | 97 | 24.2 | 63.8 | <0.001 | 401 |

| Type 1 | 37 | 41.1 | 11.9 | 53 | 58.9 | 26.4 | 41 | 45.6 | 11.4 | 49 | 54.4 | 32.2 | 90 | |||

| Type 2 | 8 | 53.3 | 2.6 | 7 | 46.7 | 3.5 | 12 | 80.0 | 3.3 | 3 | 20.0 | 2.0 | 15 | |||

| Type 3 | 2 | 33.3 | 0.6 | 4 | 66.7 | 2.0 | 3 | 50.0 | 0.8 | 3 | 50.0 | 2.0 | 6 | |||

| Secondary Intervention | No | 261 | 64.6 | 83.9 | 143 | 35.4 | 71.1 | N.A | 306 | 75.7 | 85.0 | 98 | 24.3 | 64.5 | N.A | 404 |

| Balloon angioplasty | 13 | 48.1 | 4.2 | 14 | 51.9 | 7.0 | 13 | 48.1 | 3.6 | 14 | 51.9 | 9.2 | 27 | |||

| Bypass | 14 | 77.8 | 4.5 | 4 | 22.2 | 2.0 | 13 | 72.2 | 3.6 | 5 | 27.8 | 3.3 | 18 | |||

| Bypass+ balloon angioplasty | 9 | 56.3 | 2.9 | 7 | 43.8 | 3.5 | 9 | 56.3 | 2.5 | 7 | 43.8 | 4.6 | 16 | |||

| Cuff | 7 | 21.9 | 2.3 | 25 | 78.1 | 12.4 | 12 | 37.5 | 3.3 | 20 | 62.5 | 13.2 | 32 | |||

| Cuff+bypass | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100.0 | .5 | 1 | 100.0 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |||

| Additional stent | 2 | 33.3 | 0.6 | 4 | 66.7 | 2.0 | 3 | 50.0 | 0.8 | 3 | 50.0 | 2.0 | 6 | |||

| PTCA | 2 | 66.7 | 0.6 | 1 | 33.3 | 0.5 | 1 | 33.3 | 0.3 | 2 | 66.7 | 1.3 | 3 | |||

| PTCA+ balloon angioplasty | 2 | 50.0 | 0.6 | 2 | 50.0 | 1 | 1 | 25.0 | 0.3 | 3 | 75.0 | 2.0 | 4 | |||

| PTCA+cuff | 1 | 100.0 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100.0 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |||

Demographic characteristics of the patients (2).

PTCA, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty; N.A, not applicable.

Bold values indicate statistically significant results (p < 0.05).

A gender-based assessment revealed that women had significantly larger aneurysm diameters (67.88 ± 10.20 mm vs. 66.11 ± 8.90 mm, p = 0.039) and greater aortic neck angulation (56.98 ± 15.74° vs. 43.68 ± 14.76°, p < 0.001) than men. When evaluated by age, patients ≥80 years had significantly larger aneurysm diameters (72.95 ± 11.73 mm vs. 64.21 ± 6.84 mm, p < 0.001) and greater neck angulation (56.53 ± 17.97° vs. 45.67 ± 14.68°, p < 0.001). These comparisons are presented in Table 3.

Table 3

| Variable | Gender | Age | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | p | <80 | >=80 | p | |||||||||||||||||

| Mean | SD | Median | IQR | Mean | SD | Median | IQR | Mean | SD | Median | IQR | Mean | SD | Median | IQR | |||||||

| Aneurysm diameter | 66.11 | 8.90 | 64.52 | 59.84 | 70.36 | 67.88 | 10.20 | 66.00 | 60.25 | 71.44 | 0.039 | 64.21 | 6.84 | 63.18 | 59.35 | 68.44 | 72.95 | 11.73 | 70.59 | 64.10 | 78.46 | <0.001 |

| Neck distance | 2.45 | 0.69 | 2.40 | 2.00 | 2.80 | 2.40 | 0.59 | 2.30 | 2.10 | 2.60 | 0.370 | 2.54 | 0.66 | 2.50 | 2.10 | 3.00 | 2.17 | 0.55 | 2.20 | 1.85 | 2.50 | <0.001 |

| Aortic neck diameter | 25.86 | 3.71 | 26.32 | 23.78 | 28.55 | 26.85 | 3.27 | 26.38 | 24.55 | 29.31 | 0.025 | 25.79 | 3.38 | 25.69 | 23.94 | 28.31 | 27.33 | 3.80 | 28.35 | 25.23 | 30.22 | <0.001 |

| Aortic neck angle | 43.68 | 14.76 | 43.00 | 33.00 | 53.00 | 56.98 | 15.74 | 58.00 | 45.00 | 66.00 | <0.001 | 45.67 | 14.68 | 45.00 | 35.00 | 56.00 | 56.53 | 17.97 | 56.00 | 45.00 | 69.00 | <0.001 |

| Right iliac artery diameter | 19.21 | 6.29 | 17.66 | 15.31 | 21.15 | 20.41 | 7.23 | 19.22 | 16.32 | 22.30 | 0.046 | 18.94 | 6.27 | 17.39 | 15.31 | 20.32 | 21.44 | 7.33 | 19.65 | 17.41 | 23.43 | <0.001 |

| Left iliac artery diameter | 19.96 | 6.16 | 18.52 | 16.00 | 22.22 | 21.07 | 6.40 | 19.65 | 16.71 | 22.54 | 0.014 | 19.46 | 5.41 | 18.45 | 16.00 | 21.47 | 22.62 | 7.52 | 21.31 | 16.93 | 24.81 | <0.001 |

The comparison results of clinical measurements across gender levels.

SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range.

Bold values indicate statistically significant results (p < 0.05).

Operation duration was longer in women (52.44 ± 11.30 min vs. 49.81 ± 9.72 min, p = 0.005) and in patients ≥80 years (54.57 ± 11.07 min vs. 49.27 ± 9.75 min, p < 0.001). Length of hospital stay was also significantly longer in both women and patients ≥80 years (p < 0.001). Time-related outcomes are presented in Table 4.

Table 4

| Variable | Gender | Age | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | p | <80 | >=80 | p | |||||||||||||||||

| Mean | SD | Median | IQR | Mean | SD | Median | IQR | Mean | SD | Median | IQR | Mean | SD | Median | IQR | |||||||

| Follow-up time | 90.95 | 37.91 | 95 | 69 | 122 | 94.50 | 32.51 | 96 | 76 | 120 | 0.260 | 93.84 | 35.95 | 96.5 | 72 | 122 | 88.80 | 35.62 | 88.5 | 72 | 116.5 | 0.115 |

| Operation time | 49.81 | 9.72 | 50 | 45 | 55 | 52.44 | 11.30 | 50 | 45 | 60 | 0.005 | 49.27 | 9.75 | 45 | 45 | 55 | 54.57 | 11.07 | 55 | 45 | 62.5 | <0.001 |

| Hospitalisation duration | 1.29 | 0.50 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1.54 | 0.63 | 1 | 1 | 2 | <0.001 | 1.26 | 0.49 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1.68 | 0.62 | 2 | 1 | 2 | <0.001 |

The comparison of time measurements at gender levels.

SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range.

Bold values indicate statistically significant results (p < 0.05).

Type I endoleak rates were higher in women (26.4%) compared to men (11.9%) and in patients ≥80 years (32.2%) compared to younger patients (11.4%) (p < 0.001). These rates include both intraoperative and late Type I endoleaks. Iliac angulation was notably more common in patients ≥80 years (48.7% vs. 21.7%, p < 0.001). Associations with iliac angulation are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5

| Variable | Male | Female | < 80 years of age | >= 80 years of age | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Row (%) | Column (%) | N | Row (%) | Column (%) | N | Row (%) | Column (%) | N | Row (%) | Column (%) | |||||

| Iliac angle | Yes | 90 | 59.2 | 28.9 | 62 | 40.8 | 30.8 | 0.645 | 78 | 51.3 | 21.7 | 74 | 48.7 | 48.7 | <0.001 | 152 |

| No | 221 | 61.4 | 71.1 | 139 | 38.6 | 69.2 | 282 | 78.3 | 78.3 | 78 | 21.7 | 51.3 | 360 | |||

| Graft type | Polyester | 181 | 59.2 | 58.2 | 125 | 40.8 | 62.2 | 0.369 | 208 | 68.0 | 57.8 | 98 | 32.0 | 64.5 | 0.158 | 306 |

| PTFE | 130 | 63.1 | 41.8 | 76 | 36.9 | 37.8 | 152 | 73.8 | 42.2 | 54 | 26.2 | 35.5 | 206 | |||

| Graft leg thrombosis | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | 0.359 | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | 0.626 | 152 | |||||

| 58.43 | 39.79 | 47.67 | 28.19 | 56.88 | 41.49 | 51.30 | 27.01 | |||||||||

| Graft type | Polyester | 61.00 | 42.51 | 41.67 | 22.26 | 0.082 | 56.00 | 42.71 | 52.29 | 29.84 | 0.778 | 181 | ||||

| PTFE | 43.00 | 5.72 | 71.67 | 41.93 | 0.358 | 61.75 | 39.23 | 46.67 | 2.89 | 0.545 | 130 | |||||

The results of the associations between iliac angulation gender and age groups.

PTFE, politetrafloroetilen; SD, standard deviation.

Bold values indicate statistically significant results (p < 0.05).

The comparison results of ex-status and ex-period measurements are presented in Table 6. The median follow-up period for the entire cohort was 95 months (range: 2–13 years). Of the 512 patients, 454 (88.7%) were censored (alive or lost to follow-up at the end of the study period). Cox regression analysis revealed that age ≥80 years increased mortality risk by 2.43-fold (HR = 2.430, 95% CI: 1.430–4.127, p = 0.001), whereas sex was not independently associated with mortality (HR = 1.426, 95% CI: 0.843–2.411, p = 0.185). Cox regression results are presented in Table 7.

Table 6

| Variable | Gender | p | Age | p | Total | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | <80 | >=80 | |||||||||||||

| N | Row | Column | N | Row | Column | N | Row | Column | N | Row | Column | |||||

| E×Cause | No | 283 | 62.3 | 91.0 | 171 | 37.7 | 85 | NA | 330 | 72.7 | 91.7 | 124 | 27.3 | 81.5 | NA | 454 |

| MI | 11 | 47.8 | 3.5 | 12 | 52.2 | 6.0 | 15 | 65.2 | 4.2 | 8 | 34.8 | 5.3 | 23 | |||

| CVD | 11 | 42.3 | 3.5 | 15 | 57.7 | 7.5 | 8 | 30.8 | 2.2 | 18 | 69.2 | 11.8 | 26 | |||

| Cancer | 5 | 71.4 | 1.7 | 2 | 28.6 | 1.0 | 6 | 85.7 | 1.7 | 1 | 14.3 | 0.7 | 7 | |||

| Rupture | 1 | 50.0 | 0.3 | 1 | 50.0 | 0.5 | 1 | 50.0 | 0.3 | 1 | 50.0 | 0.7 | 2 | |||

| Total | 311 | 60.7 | 100.0 | 201 | 39.3 | 100.0 | 360 | 70.3 | 100.0 | 152 | 29.7 | 100.0 | 512 | |||

| Ex (Year) | N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | p | N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | p | 58 | |

| 28 | 8.46 | 2.91 | 30 | 11.73 | 10.49 | 0.110 | 30 | 9.80 | 7.07 | 28 | 10.54 | 8.85 | 0.727 | |||

The comparison results of ex status and ex period measurements across gender and age groups.

MI, myocardial infarction; CVD, cerebrovascular disease; SD, standard deviation.

Table 7

| Variables in the equation | Overall model performance | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | B | SE | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp(B) | 95.0% CI for Exp(B) | -2LL | Chi-square | p | |

| Lower | Upper | ||||||||||

| Age (>=80) | 0.888 | 0.270 | 10.786 | 1 | 0.001 | 2.430 | 1.430 | 4.127 | 570.069 | 15.716 | <0.001 |

| Gender (female) | 0.355 | 0.268 | 1.755 | 1 | 0.185 | 1.426 | 0.843 | 2.411 | |||

The results of Cox survival regression analysis based on gender and age groups.

B, coefficients; SE, standard error; df, degrees of freedom; Sig., significance; Exp(B), hazard ratios; CL, confidence interval; -2LL, log-likelihood ratio.

Bold values indicate statistically significant results (p < 0.05).

The primary causes of long-term mortality were myocardial infarction and cerebrovascular events. There was no 30-day mortality in this elective cohort. The overall secondary reintervention rate was 18.6% (n = 95), and the most common procedures were cuff placement (n = 32) and balloon angioplasty (n = 27).

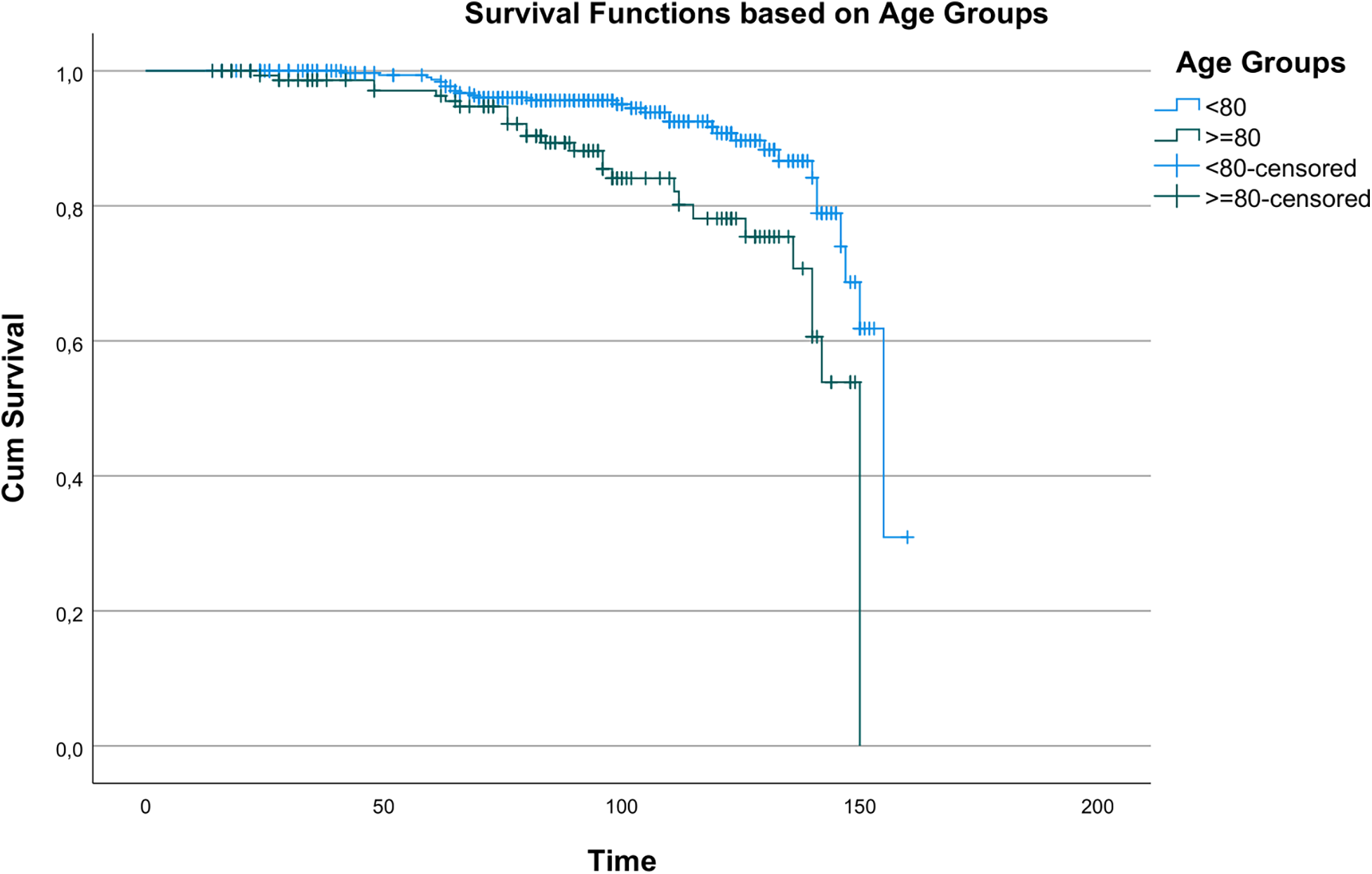

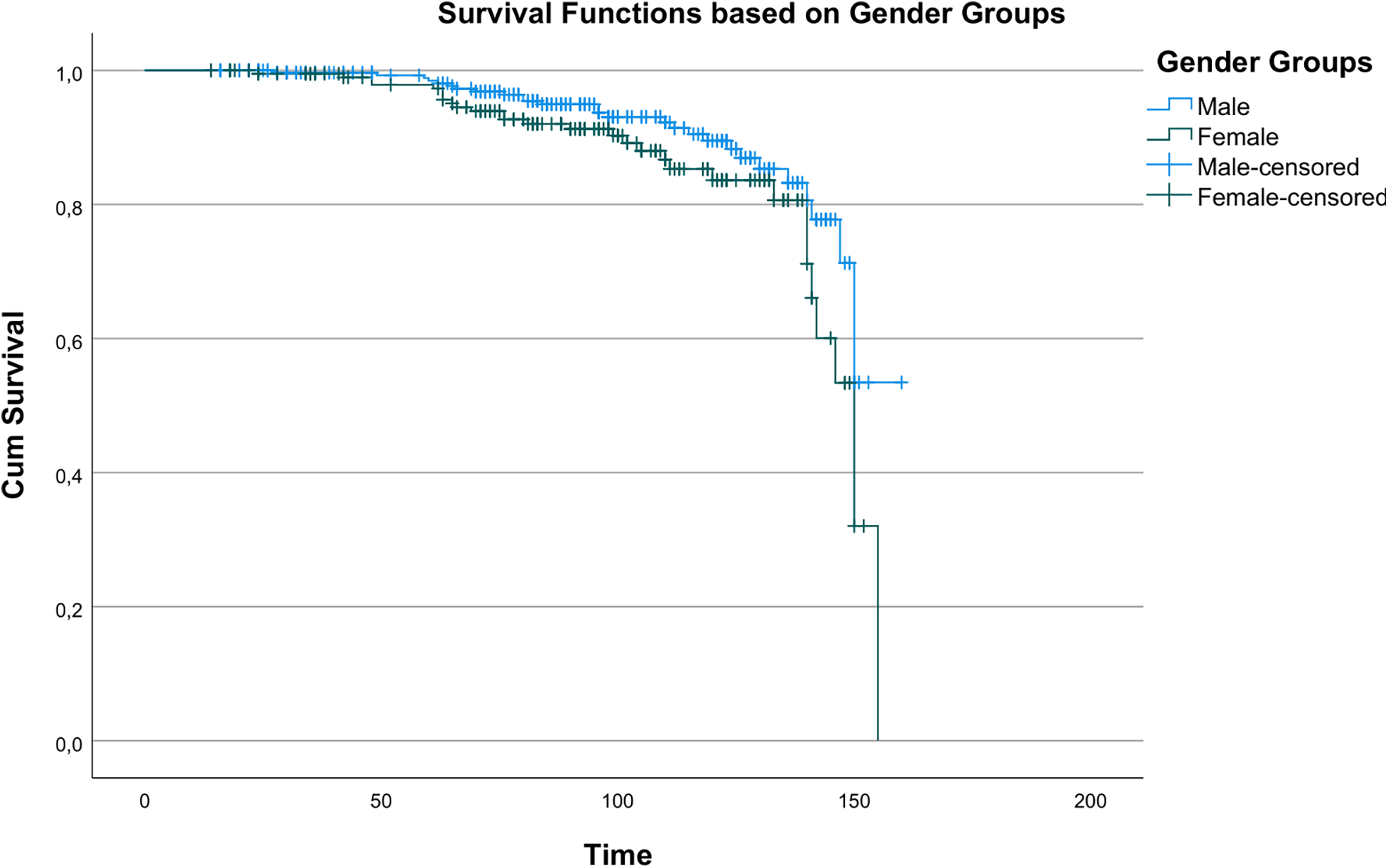

Kaplan–Meier analysis revealed statistically significant differences in survival between age groups (χ2 = 14.196, p < 0.001), indicating age as a key determinant of long-term survival. Survival curves by age are shown in Figure 1. A statistically significant but less pronounced survival difference was observed between men and women (χ2 = 3.890, p = 0.049), as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1

Kaplan–Meier survival curves showing overall survival according to age groups (<80 vs. ≥80 years).

Figure 2

Kaplan–Meier survival curves showing overall survival according to gender groups (male vs. Female).

4 Discussion

Many studies have demonstrated a strong association between smoking and AAA; smoking increases the incidence and prevalence of AAA as well as the risk of rupture (19). In our study cohort, smoking prevalence was higher in men and in patients under 80 years. Lottman et al. similarly reported that smokers tend to be younger, although they identified no sex-based differences, which is contrary to our finding (20).

In our study, 90% of patients underwent spinal anesthesia; no differences between sex and age groups were observed. By contrast, Cheng et al. reported greater use of general anesthesia (65.3%), followed by spinal anesthesia (13.5%) and local and monitored anesthesia care (14.2%). They observed a significant difference between local/monitored and general anesthesia regarding hospital stay and operative time, but no significant difference in the effect of anesthesia type on mortality and morbidity (21). Current ESVS guidelines offer a weak recommendation favoring locoregional anesthesia over general anesthesia in elective EVAR (18).

Previous studies have shown differences across sex in comorbidities among patients undergoing AAA repair. Nevidomskyte et al. reported that women had a lower prevalence of coronary artery disease but were more likely to have COPD compared to men (22). Our cohort showed similar distributions of comorbidities across sex and age groups: hypertension (46.8%), diabetes mellitus (17.9%), and COPD (15.1%).

Another notable finding in our study was that larger iliac artery diameters were observed in women and in patients over 80 years old. This contrasts with the findings of Tran et al., who reported that, despite similar body mass index (BMI) values between sexes, women had significantly smaller luminal adventitial diameters in the common iliac, external iliac, and common femoral arteries. Their study concluded that women generally have a considerably smaller iliofemoral arterial system than men (23).

We also observed that women exhibited larger aneurysm diameters and greater aortic neck angulation. This finding aligns partly with Ayo et al., who reported greater aortic neck angulation in women but no significant difference in aneurysm diameter (24). Interestingly, our female patients presented with larger aneurysm diameters (67.88 ± 10.20 mm vs. 66.11 ± 8.90 mm, p = 0.039). This finding contrasts with much of the Western literature, which typically reports smaller aortic dimensions in women. We attribute this difference to delayed diagnosis and lower participation in screening among women, which may result in more advanced progression of aneurysm at the time of EVAR.

Similarly, our elderly cohort showed greater aneurysm diameter and neck angulation, which is consistent with findings by Locham et al. (25). Donnel et al. observed that increasing age, larger neck diameter, shorter neck length, and greater angulation were associated with higher rates of Type I endoleaks (26). Our higher Type I endoleak rates are attributable to the challenging anatomies of our cohort (characterized by short neck length and high angulation) as well as the extended follow-up duration, which enables detection of late-onset endoleaks related to neck dilation or device migration.

Recent literature continues to highlight gender-related disparities in EVAR outcomes. A prospective, single-center study by Soares et al. found higher perioperative mortality rates in women undergoing aortoiliac aneurysm repair (27). This observation aligns with our findings about increased procedural difficulty for women, evidenced by their significantly higher Type I endoleak rates and greater anatomical complexity. While our Kaplan–Meier analysis showed a somewhat significant sex-based survival difference (p = 0.049), sex did not remain an independent predictor of mortality in the multivariate Cox regression model. This suggests that advanced age accounts for much of the observed disparity, which is consistent with other registry data (27).

In our study, myocardial infarction and cerebrovascular events were found to be prominent causes of mortality. While age ≥80 years showed a significantly higher risk of death (two-fold increase), gender had no significant effect on the mortality rate. This observation is consistent with established evidence of the association of AAA with myocardial infarction and claudication in men aged over 65 years and with cerebrovascular events in women (28–30). Despite some reports suggesting higher mortality in women (13% higher) (31), our analysis did not identify sex as an independent predictor. A recent prospective cohort study by Soares et al. similarly reported a significantly higher perioperative mortality rate in octogenarians (10% vs. 4%, p = 0.036). This confirms our Cox regression finding, which identified age ≥ 80 as an independent factor increasing mortality risk by 2.43-fold. However, in contrast to our Kaplan–Meier analysis, which showed a significant reduction in long-term survival for the elderly (p < 0.001), the study found that survival rates and freedom from reintervention at 1,080 days were statistically similar between octogenarians and non-octogenarians. This difference may be attributed to the shorter follow-up duration (1,080 days vs. our 13-year range) or differences in patient selection. This reinforces the need for continuous, long-term surveillance data (32).

We observed a divergence between the Kaplan–Meier analysis, which indicated a statistically significant difference in survival based on sex (p = 0.049), and the multivariate Cox regression model, which revealed no independent effect of sex on mortality (p = 0.185). This discrepancy suggests that the apparent survival disadvantage observed for women in the univariate analysis is likely not due to sex itself, but rather to its association with strong confounding factors, particularly advanced age, which serves as a powerful independent predictor of mortality in our multivariate model.

These findings underscore the importance of comprehensive anatomical evaluation and appropriate selection of stent-grafts before EVAR. We advocate for surgeons to implement more rigorous postoperative follow-up and early intervention strategies for this patient demographic. Our study has limitations. First, the retrospective design and observational nature of the survey introduce inherent limitations that may impact the findings, such as potential selection bias and reliance on the available data. We also recognize the absence of BMI values in our analysis and that vascular diameters were not categorized separately as luminal and adventitial, which we consider shortcomings of our study. Given that gender and age groupings influenced the study's integrity, we believe it would be beneficial to investigate gender and age parameters in separate studies. Furthermore, we may not have fully captured the long-term effects and complications associated with EVAR in patients with severe neck angulation.

Additionally, the use of different endograft devices for EVAR introduces a potential source of variability in our results. The utilization of endografts was not standardized throughout the study period; 204 patients were treated with the Gore Excluder device, while 308 patients received the Medtronic Endurant device. Finally, it is important to note that the follow-up period for the study varied from 2 to 13 years. Extending the follow-up duration may yield more comprehensive results.

5 Conclusion

Our study reaffirms the importance of demographic factors such as age and sex in the treatment of endovascular aneurysms. We observed that an increased aneurysm diameter, a widened aortic neck angle, and higher endoleak rates are prevalent in women and older age groups, which contribute to greater technical difficulties and postoperative risks for these populations. While our findings indicate that mortality is age-dependent, we did not observe a significant effect of sex. Therefore, tailoring treatment approaches to each patient's unique clinical and anatomical characteristics is essential for improving clinical outcomes and ensuring long-term survival.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethics Committee of Ordu University Faculty of Medicine. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

EO: Visualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. KT: Software, Investigation, Data curation, Resources, Validation, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration. MU: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Data curation. FB: Software, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Data curation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Han SM Patel K Rowe VL Perese S Bond A Weaver FA . Ultrasound-determined diameter measurements are more accurate than axial computed tomography after endovascular aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. (2010) 51(6):1381–7. 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.01.033

2.

Teutelink A Muhs BE Vincken KL Bartels LW Cornelissen SA Moll FL . Use of dynamic computed tomography to evaluate pre- and postoperative aortic changes in AAA patients undergoing endovascular aneurysm repair. J Endovasc Ther. (2007) 14:44–9. 10.1583/06-1976.1

3.

trial participants EVAR . Endovascular aneurysm repair versus open repair in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm (EVAR trial 1): randomized controlled trial. Lancet. (2005) 365:2179–86. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66627-5

4.

Lederle FA Johnson GR Wilson SE Chute EP Littooy FN Bandyk D et al Prevalence and associations of abdominal aortic aneurysm detected through screening. Ann Intern Med. (1997) 126(6):441–9. 10.7326/0003-4819-126-6-199703150-00004

5.

Badger S Forster R Blair PH Ellis P Kee F Harkin DW . Endovascular treatment for ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2017) 5(5):CD005261. 10.1002/14651858.CD005261.pub4

6.

Alberga AJ Karthaus EG van Zwet EW de Bruin JL van Herwaarden JA Wever JJ et al Outcomes in octogenarians and the effect of comorbidities after intact abdominal aortic aneurysm repair in The Netherlands: a nationwide cohort study. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. (2021) 61:920–8. 10.1016/j.ejvs.2021.02.047

7.

Wanhainen A Verzini F Van Herzeele I Allaire E Bown M Cohnert T et al Editor’s choice—European society for vascular surgery (ESVS) 2019 clinical practice guidelines on the management of abdominal aorto-iliac artery aneurysms. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. (2019) 57:8–93. 10.1016/j.ejvs.2019.11.026

8.

Spanos K Nana P Behrendt CA Kouvelos G Panuccio G Heidemann F et al Management of abdominal aortic aneurysm disease: similarities and differences among cardiovascular guidelines and NICE guidance. J Endovasc Ther. (2020) 27:889–901. 10.1177/1526602820951265

9.

Norman PE Powell JT . Abdominal aortic aneurysm: the prognosis in women is worse than in men. Circulation. (2007) 115:2865–9. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.671859

10.

Mehta M Byrne WJ Robinson H Roddy SP Paty PSK Kreienberg PB et al Women derive less benefit from elective endovascular aneurysm repair than men. J Vasc Surg. (2012) 55:906–13. 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.11.047

11.

Grootenboer N van Sambeek MR Arends LR Hendriks JM Hunink MGM Bosch JL . Systematic review and meta-analysis of sex differences in outcome after intervention for abdominal aortic aneurysm. Br J Surg. (2010) 97:1169–79. 10.1002/bjs.7134

12.

Chung C Tadros R Torres M Malik R Ellozy S Faries P et al Evolution of gender-related differences in outcomes from two decades of endovascular aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. (2015) 61(4):843–52. 10.1016/j.jvs.2014.11.006

13.

Deery SE Soden PA Zettervall SL Shean KE Bodewes TCF Pothof AB et al Sex differences in mortality and morbidity following repair of intact abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. (2017) 65:1006–13. 10.1016/j.jvs.2016.08.100

14.

Lo RC Bensley RP Hamdan AD Wyers M Adams JE Schermerhorn ML . Gender differences in abdominal aortic aneurysm presentation, repair, and mortality in the vascular study group of new England. J Vasc Surg. (2013) 57(5):1261–8. 10.1016/j.jvs.2012.11.039

15.

Ouriel K Greenberg RK Clair DG O'Hara PJ Srivastava SD Lyden SP . Endovascular aneurysm repair: gender-specific results. J Vasc Surg. (2003) 38:93–8. 10.1016/S0741-5214(03)00127-7

16.

Gloviczki P Huang Y Oderich GS Duncan AA Kalra M Fleming MD et al Clinical presentation, comorbidities, and age but not female gender predict survival after endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg. (2015) 61(4):853–61.e2. 10.1016/j.jvs.2014.12.004

17.

Abedi NN Davenport DL Xenos E Sorial E Minion DJ Endean ED . Gender and 30-day outcome in patients undergoing endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR): an analysis using the ACS NSQIP dataset. J Vasc Surg. (2009) 50:486–91. 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.04.047

18.

Wanhainen A Van Herzeele I Bastos Goncalves F Bellmunt Montoya S Berard X Boyle JR et al Editor’s choice—European society for vascular surgery (ESVS) 2024 clinical practice guidelines on the management of abdominal aorto-iliac artery aneurysms. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. (2024) 67(2):192–331. 10.1016/j.ejvs.2023.11.002

19.

Koole D Moll FL Buth J Hobo R Zandvoort HJA Pasterkamp G et al The influence of smoking on endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. (2012) 55(6):1581–6. 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.12.018

20.

Lottman PE van Marrewijk CJ Fransen GA Laheij RJ Buth J . Impact of smoking on endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm surgery outcome. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. (2004) 27(5):512–8. 10.1016/j.ejvs.2004.01.007

21.

Cheng M Chen Q McCaslin MT Chun L Lew W Barleben A . Endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair: does anesthesia type matter?Ann Vasc Surg. (2019) 61:284–90. 10.1016/j.avsg.2019.04.031

22.

Nevidomskyte D Shalhub S Singh N Farokhi E Meissner MH . Influence of gender on abdominal aortic aneurysm repair in the community. Ann Vasc Surg. (2016) 39:128–36. 10.1016/j.avsg.2016.06.012

23.

Tran K Dorsey C Lee JT Chandra V . Gender-related differences in iliofemoral arterial anatomy among abdominal aortic aneurysm patients. Ann Vasc Surg. (2017) 44:171–8. 10.1016/j.avsg.2017.01.025

24.

Ayo D Blumberg SN Gaing B Baxter A Mussa FF Rockman CB . Gender differences in aortic neck morphology in patients undergoing elective endovascular aneurysm repair. Ann Vasc Surg. (2016) 30:100–4. 10.1016/j.avsg.2015.09.002

25.

Locham S Mathlouthi A Dakour-Aridi H Malas MB . Favorable outcomes in octogenarians with hostile neck undergoing endovascular repair using EndoAnchors. Ann Vasc Surg. (2021) 74:194–203. 10.1016/j.avsg.2021.01.110

26.

O'Donnell TFX McElroy IE Mohebali J Boitano LT Lamuraglia GM Kwolek CJ et al Late type 1A endoleaks: associated factors, prognosis, and management strategies. Ann Vasc Surg. (2022) 80:273–82. 10.1016/j.avsg.2021.08.057

27.

de Athayde Soares R Nasser AI Amaro K Pecego CS Matielo MF Martins Cury MV et al The influence of gender in open surgery and endovascular repair in the treatment of nonruptured aortoiliac aneurysms. Ann Vasc Surg. (2025) 112:278–86. 10.1016/j.avsg.2024.12.048

28.

Sakalihasan N Limet R Defawe OD . Abdominal aortic aneurysm. Lancet. (2005) 365(9470):1577–89. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66459-8

29.

Kanagasabay R Gajraj H Pointon L Scott RAP . Comorbidity in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Med Screen. (1996) 3(4):208–10. 10.1177/096914139600300410

30.

Duong W Grigorian A Yuen S Nahmias J Kabutey N Lekawa M . Increased mortality in octogenarians undergoing endovascular aortic aneurysm repair for smaller aneurysms warrants caution. Ann Vasc Surg. (2024) 99:175–85. 10.1016/j.avsg.2023.07.107

31.

Ramkumar N Suckow BD Arya S Sedrakyan A Mackenzie TA Goodney PP . Association of sex with repair type and long-term mortality in adults with abdominal aortic aneurysm. JAMA Netw Open. (2020) 3(2):e1921240. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.21240

32.

Soares R dA Nasser AI Amaro K Pecego CS Nakamura ET Sacilotto R et al The influence of octagenarians in endovascular repair for aortoiliac aneurysms: long-term outcomes in a prospective cohort. Ann Vasc Surg. (2025) 117:111–20. 10.1016/j.avsg.2025.04.106

Summary

Keywords

abdominal aortic aneurysm, endovascular procedures, age factors, sex characteristics, treatment outcome, endoleak

Citation

Ozer E, Tayfur K, Urkmez M and Borulu F (2026) Influence of sex and advanced age on outcomes after endovascular aneurysm repair: a 13-year single-center retrospective cohort study. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 12:1687919. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1687919

Received

18 August 2025

Revised

20 November 2025

Accepted

16 December 2025

Published

08 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Assad Haneya, Heart Center Trier, Germany

Reviewed by

Kenneth Tran, Stanford Healthcare, Stanford, United States

Rafael De Athayde Soares, Hospital do Servidor Público Estadual, Brazil

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Ozer, Tayfur, Urkmez and Borulu.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Ersin Ozer ersinozer@live.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

ORCID Ersin Ozer orcid.org/0000-0002-7065-0004

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.