Abstract

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is the most common inherited cardiac disease and a leading cause of sudden cardiac death (SCD) in young adults and athletes. It exhibits marked clinical variability, which may be influenced by genetic background and environmental factors. Although MYBPC3 is the most frequently implicated gene, data from Latin American and admixed populations remain scarce. In this study, we describe three unrelated Ecuadorian patients with clinically diagnosed HCM who harbored MYBPC3 variants. Two patients carried likely pathogenic mutations (p.Glu258Lys and p.His875Profs*8), while novel missense variants (p.Ala536Pro and p.Thr274Met) were identified as variants of uncertain significance (VUS). Additional variants were detected in TTN, MYLK2, RYR1, SDHA, APOB, and JPH2, but given their classification as VUS or a lack of association with HCM, they are described only as incidental findings. An ancestry analysis revealed heterogeneous contributions of Native American, European, and African backgrounds, reflecting the admixed composition of the Ecuadorian population. This case series underscores the phenotypic heterogeneity of HCM, even among patients with MYBPC3 variants, and highlights the importance of genomic testing in underrepresented populations to improve diagnosis, family screening, and SCD risk stratification.

Introduction

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is one of the most common autosomal dominant inherited cardiac diseases, with an estimated prevalence of 1 in 200–500 individuals in the general population (1). Recent estimates suggest that approximately 20 million people are affected worldwide, although only approximately 10% of cases are clinically recognized (2). The diagnosis of HCM is based on the presence of unexplained left ventricular hypertrophy in a non-dilated ventricle, typically identified by echocardiography or cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (3). HCM represents one of the leading causes of sudden cardiac death (SCD), particularly in young adults and athletes (4). Despite advances in imaging and risk stratification, the clinical course of HCM remains highly variable, ranging from asymptomatic individuals with near-normal life expectancy to patients who develop severe heart failure, arrhythmias, or SCD (3).

Molecular genetics has transformed the understanding of HCM. Pathogenic variants in genes encoding sarcomeric proteins account for up to 60% of cases, with MYBPC3 and MYH7 being the most frequently implicated (5). Variants in MYBPC3 are especially common and include both truncating and missense changes. Truncating variants are typically associated with haploinsufficiency through nonsense-mediated RNA decay (NMD) and ubiquitin–proteasome system (UPS) degradation, while the clinical impact of missense variants is more heterogeneous (5–7). The wide phenotypic spectrum of HCM likely reflects the combined effects of primary sarcomeric variants, variable penetrance, and non-genetic influences (8).

Although most genetic studies have been conducted in North American and European cohorts, Latin American and admixed populations remain underrepresented in the literature (9). The genetic diversity of these populations, shaped by varying proportions of Native American, European, and African ancestry, provides a unique context to explore the molecular and phenotypic variability of HCM. Characterizing these cohorts is crucial to improve risk stratification, expand the catalog of variants with clinical relevance, and enhance the understanding of ancestry-related contributions to disease expression (9, 10).

In this study, we describe the clinical and genomic evaluation of three unrelated Ecuadorian patients with HCM. This case series aims to explore genotype–phenotype correlations, assess the potential contribution of additional cardiomyopathy-associated variants, and consider the role of genetic ancestry in an admixed population. By doing so, we seek to expand the understanding of HCM in underrepresented populations and highlight the value of genomic testing for diagnosis, family screening, and SCD risk stratification.

Case presentation

Three unrelated Ecuadorian patients with HCM and family histories suggestive of hereditary cardiac disease were included in this study. The diagnosis of HCM was established clinically, without initial genetic confirmation. Clinical diagnosis was based on symptoms, family history, and echocardiographic findings following established adult and pediatric criteria. The clinical diagnosis of HCM prompted genomic testing and ancestry analysis. To carry out these analyses, peripheral blood samples were collected, and genomic DNA was extracted and quantified following standard protocols. DNA quality and concentration were verified fluorometrically. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) was performed at the Centro de Investigación Genética y Genómica (CIGG), UTE University, using the TruSight Cardio panel (Illumina), which analyzes 174 genes associated with inherited cardiac disorders. Sequencing was conducted on a MiSeq platform, and variant interpretation followed ACMG guidelines, integrating population frequency data, in silico predictions, and genotype–phenotype correlation. The interpretation of the genomic findings was performed jointly by cardiologists and geneticists to ensure accurate clinical–genetic correlation. In addition, genetic ancestry was evaluated using a validated panel of 46 ancestry-informative insertion/deletion markers (AIMs-InDels). Genotyping was performed by using PCR and capillary electrophoresis, and ancestry inference was carried out with STRUCTURE software (v2.3.4), yielding proportional estimates of Native American, European, and African ancestry.

Subject 1

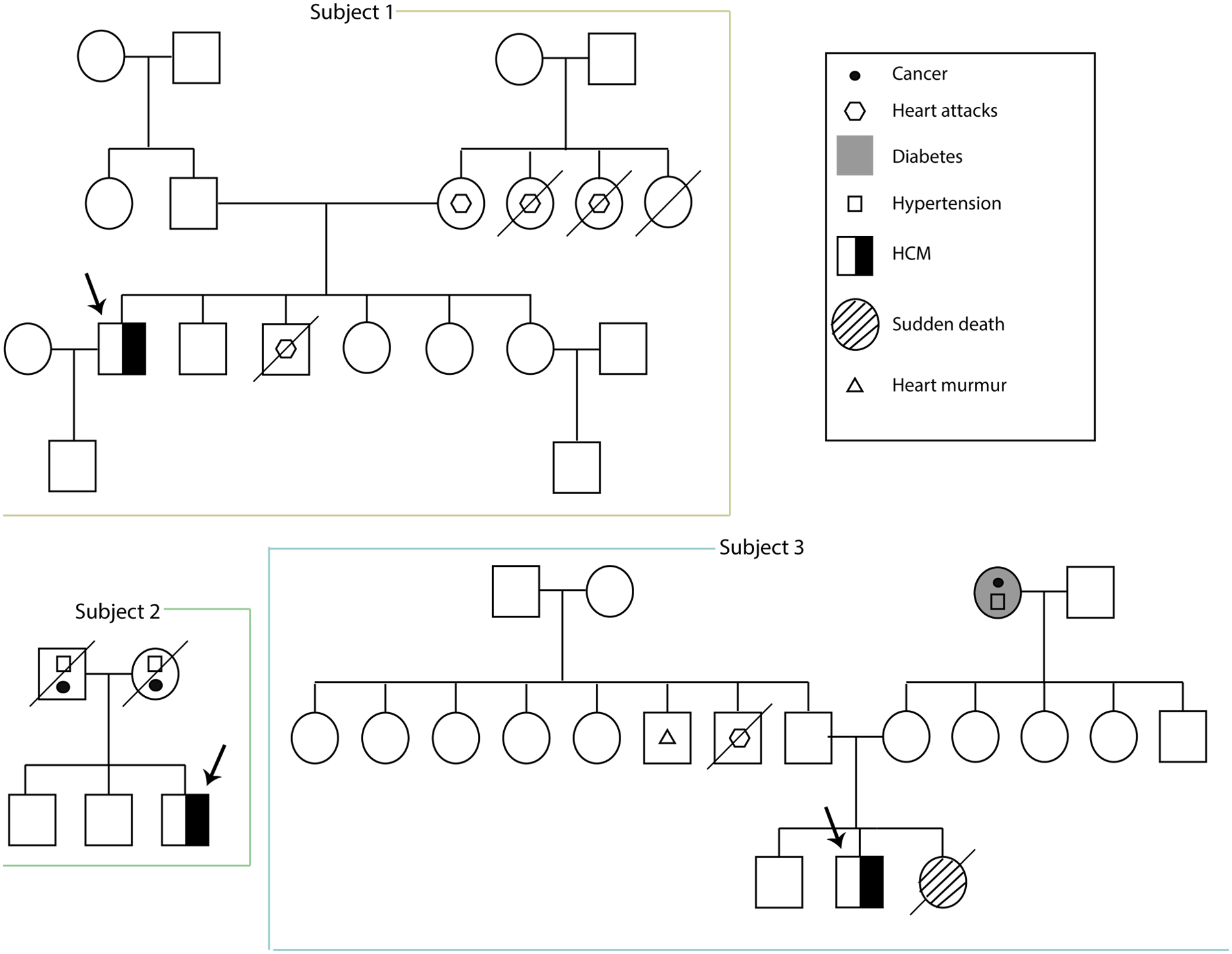

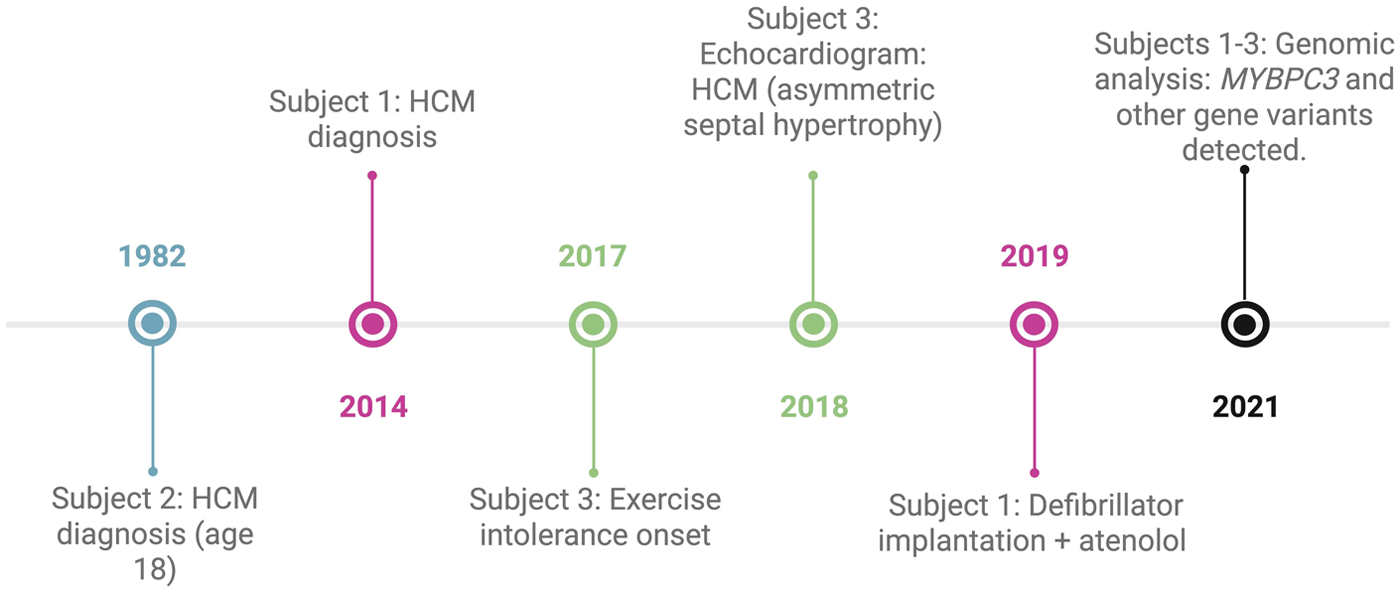

A 44-year-old male from Guaranda was diagnosed with HCM in 2014. His medical history included long-term atenolol therapy and implantation of an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) in 2019 for primary prevention, based on an estimated 5-year SCD risk of 3.9% according to the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) risk model. Transthoracic echocardiography demonstrated asymmetric septal hypertrophy, with a maximal interventricular septal thickness of 24 mm, dynamic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction (maximum gradient 40 mmHg), and systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve. Left ventricular systolic function was preserved (ejection fraction 70%), with evidence of grade II diastolic dysfunction. Family history was notable for first-degree relatives with myocardial infarction (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Familial pedigrees of three unrelated male patients (subjects 1–3) with HCM. The proband in each family is indicated by an arrow.

Genetic testing revealed a likely pathogenic variant in MYBPC3 (p.Glu258Lys). Additional findings included two variants of uncertain significance (VUS) in TTN (p.Arg3224Gly) and MYLK2 (p.Gln525Arg) (Table 1). The ancestry profile demonstrated a predominant Native American component (46.7%), with European (38.5%) and African (14.8%) contributions.

Table 1

| Subject | Age (years) | Gender | Gene | Genetic variant c.notation/p.notation | Consequencea | Classification reference SNP | ACMG guidelines (1, 11) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 44 | Male | MYBPC3 | NM_000256.3 | Missense | Likely pathogenic | PS4, PP1, PS3, PM2, PP3, PP5 |

| c.772G>A | |||||||

| p.(Glu258Lys) | rs397516074 | ||||||

| TTN | NM_001267550.2 | Missense | VUS | PM2 | |||

| c.9670A>G | |||||||

| p.(Arg3224Gly) | |||||||

| MYLK2 | NM_033118.3 | Missense | VUS | PM2, BP4 | |||

| c. 1574A>G | |||||||

| p.(Gln525Arg) | |||||||

| 2 | 57 | Male | MYBPC3 | NM_000256.3 | Missense | VUS | PM2, PP3 |

| c.1606G>C | |||||||

| p.(Ala536Pro) | |||||||

| TTN | NM_001267550.2 | Missense | VUS | PM2 | |||

| c.22148A>G | |||||||

| p.(Asn7383Ser) | |||||||

| RYR1 | NM_000540.2 | Missense | VUS | PM2, PP2 | |||

| c.9494G>A | |||||||

| p.(Cys3165 Tyr) | |||||||

| 3 | 17 | Male | MYBPC3 | NM_000256.3 | Frameshift Indels | Likely pathogenic | PVS1, PM2 |

| c.2624_2625del | |||||||

| p.(His875Profs*8) | |||||||

| MYBPC3 | NM_000256.3 | Missense | VUS | PM2,PP3 | |||

| c.821C>T | |||||||

| p.(Thr274Met) | |||||||

| SDHA | NM_004168.3 | Frameshift Indels | VUS | PVS1 | |||

| c.1945_1946del | |||||||

| p.(Leu649Glufs*4) | |||||||

| APOB | NM_000384.2 | Missense | VUS | PM2, BP6 | |||

| c.3443T>A | |||||||

| p.(Leul148His) | |||||||

| JPH2 | NM_020433.4 | Missense | VUS | PM2, BP4 | |||

| c. 1615G>A | |||||||

| p. (Ala539Thr) |

Description of the genetic variants identified in patients diagnosed with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM). Variants were classified according to ACMG-AMP guidelines.

All variants are heterozygous; 1PVS1: Predicted null variant (e.g., nonsense and frameshift) in a gene where loss of function is a known mechanism of disease; PS4: Prevalence of the variant in affected individuals significantly increased compared with controls; PP1: Cosegregation with disease in multiple affected family members; PS3: Functional studies supportive of a damaging effect on the gene or gene product; PM2: Absent or rare in population databases; PP3: Multiple computational lines of evidence support a deleterious effect; PP5: Reputable source reports the variant as pathogenic; BP4: Computational evidence supports a benign effect; BP6: Reputable source reports the variant as benign; PP2: Missense variant in a gene with a low rate of benign missense variation and where missense variants are a common mechanism of disease.

Subject 2

A 57-year-old male from Zaruma was diagnosed with HCM at age 18 (Figure 1). He reported no regular pharmacological treatment. His family history included parental hypertension and cancer (Figure 2).

Figure 1

Clinical and genomic timelines of three Ecuadorian patients with HCM. Each case is represented by a distinct color: pink for subject 1, blue for subject 2, green for subject 3, and black for events shared across all three cases.

Genetic testing identified only variants of uncertain significance: MYBPC3 (p.Ala536Pro), TTN (p.Asn7383Ser), and RYR1 (p.Cys3165Tyr) (Table 1). Furthermore, an ancestry analysis showed a predominance of European ancestry (56.2%), with Native American (24.5%) and African (19.3%) components.

Subject 3

A 19-year-old male from Ibarra presented with a history of exertional intolerance since childhood, characterized by fatigue and presyncope first documented in 2017 (Figure 1). Perinatal history included late preterm birth and neonatal jaundice secondary to maternal preeclampsia. Family history was notable for a sister who died at three months of age from presumed sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), although this cannot be classified as confirmed sudden cardiac death because of the lack of autopsy data. Additional relatives had cardiovascular conditions, including a paternal uncle with myocardial infarction at 58, another with a heart murmur, and a grandmother with hypertension (Figure 2).

A transthoracic echocardiogram performed in 2018 showed asymmetric interventricular septal hypertrophy, with septal thickness evaluated according to pediatric age- and body-size–adjusted reference standards, which at the time of the study were interpreted by the pediatric cardiologist as consistent with HCM. Left ventricular systolic function was preserved. The study also identified a bicuspid aortic valve with preserved opening and mild functional impairment. No additional structural abnormalities were observed. These findings supported the diagnosis of non-obstructive HCM with asymmetric septal hypertrophy and an associated bicuspid aortic valve.

A genomic analysis identified a likely pathogenic frameshift variant in MYBPC3 (p.His875Profs*8), together with a VUS in the same gene (p.Thr274Met). Additional VUS were detected in SDHA (p.Leu649GlufsTer4), APOB (p.Leu1148His), and JPH2 (p.Ala539Thr) (Table 1). An ancestry analysis revealed a predominant Native American component (69.6%), with European (22.4%) and African (8.0%) contributions.

Discussion

This report describes the clinical and genomic features of three unrelated Ecuadorian patients with HCM carrying variants in MYBPC3, the gene most frequently implicated in this disorder. Two variants, p.Glu258Lys and p.His875Profs*8, were classified as likely pathogenic, whereas p.Ala536Pro and p.Thr274Met were classified as VUS. Together, these findings expand the molecular spectrum of MYBPC3-related HCM and represent the first characterization of such cases in Ecuador, underscoring the importance of genomic studies in underrepresented admixed populations.

Consistent with previous reports, MYBPC3 variants in this series were associated with marked phenotypic variability (12–14). Such heterogeneity was observed even in monozygotic twins carrying the same pathogenic MYBPC3 variant (p.G263Ter), who exhibited distinct degrees of penetrance and clinical severity (15). All three probands in our cohort were male and developed HCM during adolescence or early adulthood. Two displayed high-risk clinical features, ICD implantation in Subject 1 and a family history of SCD in Subject 3, highlighting the potential for malignant arrhythmias even within a small cohort. This variability among carriers of pathogenic MYBPC3 variants likely reflects the combined influence of genetic, environmental, and modifier factors on disease expression and progression (12–14).

The MYBPC3 gene encodes cardiac myosin-binding protein C (cMyBP-C), a sarcomeric protein that interacts with actin, myosin, and titin and plays a critical role in regulating myocardial contractility. Truncating MYBPC3 variants typically introduce premature stop codons, leading to reduced protein levels through nonsense-mediated RNA decay (NMD) and degradation by the ubiquitin–proteasome system (UPS), resulting in haploinsufficiency (16). In Subject 3, we identified a novel truncating variant, p.His875Profs*8, classified as likely pathogenic and consistent with the proband's phenotype of non-obstructive HCM with asymmetric septal hypertrophy. Similar truncating MYBPC3 variants have been associated with left ventricular hypertrophy and ventricular tachycardia, supporting haploinsufficiency as the main disease mechanism (16).

In addition to truncating variants, three MYBPC3 missense variants were detected: p.Glu258Lys in Subject 1, p.Ala536Pro in Subject 2, and p.Thr274Met in Subject 3. The p.Glu258Lys variant has been reported in several individuals with HCM and has been classified as pathogenic in multiple studies (17–20), supporting its role in the severe phenotype observed in Subject 1. In contrast, p.Ala536Pro and p.Thr274Met have not been previously described in HCM patients and are currently classified as VUS (21, 22).

With respect to p.Ala536Pro, a substitution at the same residue (p.Ala536Gly) was described in a 13-year-old proband with HCM (23), suggesting functional relevance of this region of MYBPC3. Although alanine and proline share similar biochemical properties, substitutions at this residue may still influence protein stability, alter sarcomeric interactions, or affect protein turnover through NMD/UPS pathways. Nevertheless, available evidence is insufficient to establish pathogenicity, and the contribution of p.Ala536Pro to the phenotype of Subject 2 remains uncertain. Additional segregation and functional studies are required to better define its clinical relevance (12).

A similar level of caution applies to p.Thr274Met, detected in Subject 3. Although methionine has biochemical properties that are different from those of threonine, computational models have predicted no major structural or functional impact for this substitution (22). The coexistence of a missense variant with a truncating MYBPC3 mutation raises the possibility of cumulative effects on protein dosage; however, this remains uncertain and cannot be inferred without segregation or functional data.

Variants in additional genes were also identified. Subject 1 harbored MYLK2 p.Gln525Arg. MYLK2 encodes myosin light chain kinase 2, a calcium/calmodulin-dependent enzyme that is predominantly expressed in the skeletal muscle and phosphorylates the regulatory light chain of myosin (24). Pathogenic MYLK2 variants have been reported in association with midventricular hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and cardiac repolarization abnormalities, including inverted T waves on electrocardiogram, as described in carriers of the p.Lys324Glu mutation (25, 26). Although the p.Gln525Arg variant has not been previously described in patients with HCM, its location within a conserved kinase domain raises the possibility of functional relevance (25).

In addition, TTN variants were identified in both Subject 1 (p.Arg3224Gly) and Subject 2 (p.Asn7383Ser). The p.Arg3224Gly variant has been previously reported in an individual with ventricular fibrillation (27), while the p.Asn7383Ser variant has not been previously described. TTN is essential for sarcomeric structure, providing mechanical stability and acting as a molecular scaffold that coordinates interactions with multiple contractile and signaling proteins (16). Although TTN missense variants are common in the general population and most lack diagnostic value in HCM (28), emerging evidence indicates that a small subset of TTN missense variants can contribute to disease when supported by segregation and functional data. For example, a recent study in a Chinese HCM pedigree identified a TTN missense variant p.Arg6745Cys that segregated with affected family members and was predicted to impair protein function, supporting its pathogenic role (29). These findings suggest that TTN missense variants cannot be categorically dismissed (28); however, the variants identified in our patients do not currently meet criteria for pathogenicity or modifier status, and their clinical significance therefore remains uncertain.

In addition, Subject 2 harbored the RYR1 p.Cys3165Tyr variant, which has not been previously associated with HCM. Pathogenic variants in RYR1 are classically linked to early-onset myopathies (30). RYR1 encodes ryanodine receptor 1, a sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release channel that plays a central role in excitation–contraction coupling (31). While its expression is predominant in the skeletal muscle, RYR1 is also detected in cardiac and vascular tissues, where it contributes to intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis (32). Experimental studies have suggested that alterations in RYR1 expression or function may promote left ventricular hypertrophy by modulating calcium flux and myocardial remodeling (33). The p.Cys3165Tyr variant has not been reported in patients with HCM; however, its localization within a regulatory domain indicates that further investigation would be required to determine whether it has any physiological relevance in the context of this case.

Subject 3 carried the SDHA p.Leu649Glufs*4 and APOB p.Leu1148His variants. SDHA encodes a subunit of mitochondrial complex II (succinate dehydrogenase), a critical component of oxidative phosphorylation (34). Although SDHA is not an established gene for primary sarcomeric HCM, pathogenic SDHA variants have been reported in association with cardiomyopathy exhibiting hypertrophic features, most often as part of multisystem mitochondrial disease (34, 35). Notably, the same SDHA p.Leu649Glufs*4 variant has been described in a young woman with mitochondrial disease presenting with left ventricular hypertrophy and cardiomyopathy in the setting of compound heterozygous SDHA variants (36). These observations support cardiac involvement as a component of SDHA-related disease; however, they do not establish SDHA as a cause of isolated HCM. In the present case, the absence of additional clinical or biochemical features suggestive of mitochondrial dysfunction precludes attribution of the HCM phenotype to the SDHA variant, and its contribution therefore remains uncertain.

In addition to the SDHA variant, Subject 3 also carried APOB p.Leu1148His. APOB encodes apolipoprotein B, the principal structural component of low-density lipoprotein (37), and pathogenic variants in this gene are primarily associated with familial hypercholesterolemia, leading to elevated LDL cholesterol levels and an increased risk of premature atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (38). Although APOB is not related to sarcomeric HCM and does not contribute to the development of myocardial hypertrophy, APOB variants may be clinically relevant by increasing overall cardiovascular risk (39) through dyslipidemia and ischemic mechanisms, which can predispose to adverse cardiac events, including sudden cardiac death, particularly in the presence of underlying structural heart disease (40).

Subject 3 also carried a JPH2 missense variant (p.Ala539Thr). JPH2 encodes junctophilin-2, a structural protein essential for the formation of junctional membrane complexes that facilitate excitation–contraction coupling in cardiomyocytes. While JPH2 is not a canonical sarcomeric gene, a pathogenic JPH2 mutation (p.Thr161Lys) was implicated as a non-sarcomeric candidate gene for HCM in Finnish families, where it was associated with ventricular hypertrophy, arrhythmia, and conduction abnormalities (41).

In this context, Subject 3 carried a complex genetic profile, including a truncating MYBPC3 variant (p.His875Profs*8), an additional MYBPC3 missense variant (p.Thr274Met), a truncating SDHA variant (p.Leu649Glufs*4), the APOB p.Leu1148His variant, and the JPH2 p.Ala539Thr variant. The MYBPC3 truncating variant represents the most compelling genetic explanation for the HCM phenotype. In contrast, the SDHA and JPH2 variants cannot be assigned a causal or modifying role with the available data and are best interpreted as secondary or incidental findings. The APOB p.Leu1148His variant likewise does not support a causal or modifying role in HCM; however, it may represent a relevant comorbidity that could contribute to overall cardiovascular risk in the presence of a confirmed sarcomeric disease substrate. Clarification of the individual or combined relevance of these secondary variants will require segregation analysis and functional studies.

Altogether, our findings illustrate how MYBPC3 variants, particularly truncating mutations such as p.His875Profs*8, contribute to phenotypic severity and may increase susceptibility to malignant arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death. Additional variants detected in non-sarcomeric or non-HCM genes are reported as part of the broader genetic profile, although their clinical relevance in HCM remains uncertain. Subject 1, who required implantable cardioverter-defibrillator implantation, and Subject 3, with a strong family history of sudden cardiac death, exemplify the critical need for careful surveillance and timely clinical intervention. Collectively, these cases underscore the importance of integrating genomic findings with conventional risk stratification tools to optimize preventive strategies against SCD.

As for ancestry, Subjects 1 and 3 showed a higher proportion of Native American background. HCM has not been shown to have a higher prevalence in any specific ethnic group (16). However, studies have reported that Black patients are diagnosed at a younger age than white patients, despite exhibiting a lower frequency of sarcomeric mutations (42). In our cohort, the admixed ancestry background did not allow establishing a clear association between ethnicity and HCM susceptibility, particularly given the high proportion of European ancestry in Subject 2. Therefore, a more comprehensive characterization of HCM in admixed populations is needed to determine whether ancestry influences disease pathogenesis, severity, or prognosis.

Several limitations in this study should be acknowledged. Further exploration of the family pedigrees was limited by the unavailability or lack of consent from additional relatives. Moreover, access to the complete medical records of the patients was restricted, which prevented a more detailed analysis of clinical evolution, treatment response, and follow-up. Although familial HCM was suspected in all three cases, the absence of confirmed diagnoses in previous generations raises the possibility that some MYBPC3 variants could represent de novo events or show incomplete penetrance. Future cascade genetic testing in extended family members will be essential to clarify segregation and inheritance patterns and refine genetic risk assessment.

Conclusion

This study provides a clinical and genomic characterization of three unrelated Ecuadorian individuals with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy harboring variants in MYBPC3, as well as additional variants in TTN, MYLK2, RYR1, SDHA, APOB, and JPH2, reinforcing the marked phenotypic heterogeneity of HCM even among patients with variants in the same primary disease gene. The identification of likely pathogenic truncating MYBPC3 variants supports haploinsufficiency, mediated by nonsense-mediated RNA decay and proteasomal degradation, as a central mechanism of disease pathogenesis. In contrast, missense variants and variants detected in non-sarcomeric or non-HCM genes were classified as variants of uncertain significance, underscoring the challenges of variant interpretation and emphasizing the need for segregation analyses and functional studies to clarify their potential clinical relevance.

From a clinical perspective, the presence of high-risk features in two probands, namely implantable cardioverter-defibrillator implantation and a strong family history of sudden cardiac death, highlights the importance of vigilant surveillance and individualized risk stratification in patients with MYBPC3-related HCM. These findings emphasize the value of integrating genomic information with established clinical risk markers to inform preventive strategies against malignant arrhythmias and SCD.

Finally, the admixed Native American, European, and African ancestry observed in this cohort underscores the importance of expanding genomic studies in underrepresented populations. A broader inclusion of diverse ancestries will be essential to improve variant interpretation, refine risk assessment, and advance understanding of the genetic architecture and clinical expression of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy across populations.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original datasets presented in this study are publicly available in a community-supported repository. The data can be accessed in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under accession number PRJNA1399500: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/PRJNA1399500.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Universidad UTE (approval number CEISH-2021-016). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

EP-C: Methodology, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. PG-R: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. RT-T: Methodology, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. VR-P: Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SC-U: Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RI-C: Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. JL-B: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology. LM-C: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. AC-A: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AZ: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Supervision, Conceptualization, Project administration.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. The publication fees for this article were covered by Universidad UTE. No additional external funding was received for the conduct of this study.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence, and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors, wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Maron BA Wang RS Carnethon MR Rowin EJ Loscalzo J Maron BJ et al What causes hypertrophic cardiomyopathy? Am J Cardiol. (2022) 179:74–82. 10.1016/J.AMJCARD.2022.06.017

2.

Cadena-Ullauri S Guevara-Ramirez P Ruiz-Pozo V Tamayo-Trujillo R Paz-Cruz E Sánchez Insuasty T et al Case report: genomic screening for inherited cardiac conditions in Ecuadorian mestizo relatives: improving familial diagnose. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2022) 9:1037370. 10.3389/FCVM.2022.1037370

3.

Antunes MdO Scudeler TL . Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc. (2020) 27:100503. 10.1016/J.IJCHA.2020.100503

4.

Marian AJ Braunwald E . Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: genetics, pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and therapy. Circ Res. (2017) 121(7):749–70. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.311059

5.

Lopes LR Ho CY Elliott PM . Genetics of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: established and emerging implications for clinical practice. Eur Heart J. (2024) 45(30):2727–34. 10.1093/EURHEARTJ/EHAE421

6.

Helms AS Thompson AD Glazier AA Hafeez N Kabani S Rodriguez J et al Spatial and functional distribution of MYBPC3 pathogenic variants and clinical outcomes in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ Genom Precis Med. (2020) 13(5):396–405. 10.1161/CIRCGEN.120.002929

7.

Carrier L Schlossarek S Willis MS Eschenhagen T . The ubiquitin-proteasome system and nonsense-mediated mRNA decay in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc Res. (2009) 85(2):330–8. 10.1093/CVR/CVP247

8.

Klasfeld SJ Knutson KA Miller MR Fauman EB Berghout J Moccia R et al Common genetic modifiers influence cardiomyopathy susceptibility among the carriers of rare pathogenic variants. Hum Genet Genom Adv. (2025) 6(3):100460. 10.1016/J.XHGG.2025.100460

9.

Lopez JD Tovar V Giraldo HL Naranjo MC Florez N Olaya P Carrillo D Gomez JE . Race/ethnicity and clinical outcomes in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: insights from a Latin American center. Preprints.org. Published online (2025). 10.20944/preprints202502.2020.v1

10.

Belbin GM Nieves-Colón MA Kenny EE Moreno-Estrada A Gignoux CR . Genetic diversity in populations across Latin America: implications for population and medical genetic studies. Curr Opin Genet Dev. (2018) 53:98–104. 10.1016/J.GDE.2018.07.006

11.

Richards S Aziz N Bale S Bick D Das S Gastier-Foster J et al Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. (2015) 17(5):405–24. 10.1038/GIM.2015.30

12.

Tudurachi BS Zăvoi A Leonte A Țăpoi L Ureche C Bîrgoan SG et al An update on MYBPC3 gene mutation in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Int J Mol Sci. (2023) 24(13):10510. 10.3390/IJMS241310510

13.

Micheu MM Popa-Fotea NM Oprescu N Bogdan S Dan M Deaconu A et al Yield of rare variants detected by targeted next-generation sequencing in a cohort of Romanian Index patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Diagnostics. (2020) 10(12):1061. 10.3390/DIAGNOSTICS10121061

14.

Sepp R Hategan L Csányi B Borbás J Tringer A Pálinkás ED et al The genetic architecture of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in Hungary: analysis of 242 patients with a panel of 98 genes. Diagnostics. (2022) 12(5):1132. 10.3390/DIAGNOSTICS12051132

15.

Rodríguez Junquera M Salgado M González-Urbistondo F Alén A Rodríguez-Reguero JJ Silva I et al Different phenotypes in monozygotic twins, carriers of the same pathogenic variant for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Life. (2022) 12(9):1346. 10.3390/LIFE12091346

16.

Marian AJ . Molecular genetic basis of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. (2021) 128(10):1533–53. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.121.318346

17.

Höller V Seebacher H Zach D Schwegel N Ablasser K Kolesnik E et al Myocardial deformation analysis in mybpc3 and myh7 related sarcomeric hypertrophic cardiomyopathy—the Graz hypertrophic cardiomyopathy registry. Genes (Basel). (2021) 12(10):1469. 10.3390/GENES12101469

18.

Suay-Corredera C Pricolo MR Herrero-Galán E Velázquez-Carreras D Sánchez-Ortiz D García-Giustiniani D et al Protein haploinsufficiency drivers identify MYBPC3 variants that cause hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Biol Chem. (2021) 297(1):100854. 10.1016/J.JBC.2021.100854

19.

García-Vielma C Lazalde-Córdova LG Arzola-Hernández JC González-Aceves EN López-Zertuche H Guzmán-Delgado NE et al Identification of variants in genes associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in Mexican patients. Mol Genet Genomics. (2023) 298(6):1289–99. 10.1007/S00438-023-02048-8

20.

NCBI-ClinVar. NM_000256.3(MYBPC3):c.772G>T (p.Glu258Ter). NCBI (2025). Available online at:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/variation/3020531/(Accessed August 7, 2025).

21.

NCBI-ClinVar. NM_000256.3(MYBPC3):c.1606G>C (p.Ala536Pro). NCBI (2025). Available online at:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/variation/1015909/?oq=((1009722[AlleleID]))&m=NM_000256.3(MYBPC3):c.1606G%3EC%20(p.Ala536Pro)(Accessed August 11, 2025).

22.

NCBI-ClinVar. NM_000256.3(MYBPC3):c.821C>T (p.Thr274Met). NCBI (2025). Available online at:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/variation/846235/(Accessed August 11, 2025).

23.

Miller EM Wang Y Ware SM . Uptake of cardiac screening and genetic testing among hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathy families. J Genet Couns. (2013) 22(2):258–67. 10.1007/S10897-012-9544-4

24.

Qin X Li P Qu HQ Liu Y Xia Y Chen S et al FLNC And MYLK2 gene mutations in a Chinese family with different phenotypes of cardiomyopathy. Int Heart J. (2021) 62(1):127–34. 10.1536/IHJ.20-351

25.

Wang L Zuo L Hu J Shao H Lei C Qi W et al Dual LQT1 and HCM phenotypes associated with tetrad heterozygous mutations in KCNQ1, MYH7, MYLK2, and TMEM70 genes in a three-generation Chinese family. EP Europace. (2016) 18(4):602–9. 10.1093/EUROPACE/EUV043

26.

Wang J Guo RQ Guo JY Zuo L Lei C-H Shao H et al Investigation of myocardial dysfunction using three-dimensional speckle tracking echocardiography in a genetic positive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy Chinese family. Cardiol Young. (2018) 28(9):1106–14. 10.1017/S1047951118000860

27.

Paz-Cruz E Ruiz-Pozo VA Cadena-Ullauri S Guevara-Ramirez P Tamayo-Trujillo R Ibarra-Castillo R et al Associations of MYPN, TTN, SCN5A, MYO6 and ELN mutations with arrhythmias and subsequent sudden cardiac death: a case report of an Ecuadorian individual. Cardiol Res. (2023) 14(5):409–15. 10.14740/CR1552

28.

Jolfayi AG Kohansal E Ghasemi S Naderi N Hesami M MozafaryBazargany M et al Exploring TTN variants as genetic insights into cardiomyopathy pathogenesis and potential emerging clues to molecular mechanisms in cardiomyopathies. Sci Rep. (2024) 14(1):1–37. 10.1038/s41598-024-56154-7

29.

Dong J Liu M Chen Q Zha L . A case study identified a new mutation in the TTN gene for inherited hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Int J Gen Med. (2025) 18:447–58. 10.2147/IJGM.S505865

30.

Bharucha-Goebel DX Santi M Medne L Zukosky K Dastgir J Shieh PB et al Severe congenital RYR1-associated myopathy: the expanding clinicopathologic and genetic spectrum. Neurology. (2013) 80(17):1584–9. 10.1212/WNL.0B013E3182900380

31.

Biancalana V Rendu J Chaussenot A Mecili H Bieth E Fradin M et al A recurrent RYR1 mutation associated with early-onset hypotonia and benign disease course. Acta Neuropathol Commun. (2021) 9(1):1–10. 10.1186/S40478-021-01254-Y

32.

Guerra LA Lteif C Huang Y Flohr RM Nogueira AC Gawronski BE et al Genetic variation in RYR1 is associated with heart failure progression and mortality in a diverse patient population. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2025) 12:1529114. 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1529114

33.

Hong KW Shin DJ Lee SH Son N-H Go M-J Lim J-E et al Common variants in RYR1 are associated with left ventricular hypertrophy assessed by electrocardiogram. Eur Heart J. (2012) 33(10):1250–6. 10.1093/EURHEARTJ/EHR267

34.

White G Tufton N Akker SA . First-positive surveillance screening in an asymptomatic SDHA germline mutation carrier. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab Case Rep. (2019) 2019(1):19-0005. 10.1530/EDM-19-0005

35.

Courage C Jackson CB Hahn D Nuoffer J Gallati S Schaller A . SDHA Mutation with dominant transmission results in complex II deficiency with ocular, cardiac, and neurologic involvement. Am J Med Genet A. (2017) 173(1):225–30. 10.1002/AJMG.A.37986

36.

Ürey BC Ceylan AC Çavdarll B Ürey BC Çavdarlı B Çıtak Kurt AN et al Two patients diagnosed as succinate dehydrogenase deficiency: case report. Mol Syndromol. (2023) 14(2):171. 10.1159/000527538

37.

Rodríguez-Jiménez C de la Peña G Sanguino J Poyatos-Peláez S Carazo A Martínez-Hernández PL et al Identification and functional analysis of APOB variants in a cohort of hypercholesterolemic patients. Int J Mol Sci. (2023) 24(8):7635. 10.3390/IJMS24087635

38.

Salgado M Díaz-Molina B Cuesta-Llavona E Aparicio A Fernández M Alonso V et al Opportunistic genetic screening for familial hypercholesterolemia in heart transplant patients. J Clin Med. (2023) 12(3):1233. 10.3390/JCM12031233

39.

NCBI-ClinVar. VCV000928133.12—ClinVar—NCBI. NCBI (2025). Available online at:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/variation/928133/?oq=((908407[AlleleID]))&m=NM_000384.3(APOB):c.3443T%3EA%20(p.Leu1148His)(Accessed August 12, 2025).

40.

Marziliano N Medoro A Mignogna D Saccon G Folzani S Reverberi C et al Sudden cardiac death caused by a fatal association of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (MYH7, p.Arg719Trp), heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia (LDLR, p.Gly343Lys) and SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.7 infection. Diagnostics. (2021) 11(7):1229. 10.3390/DIAGNOSTICS11071229

41.

Vanninen SUM Leivo K Seppälä EH Aalto-Setälä K Pitkänen O Suursalmi P et al Heterozygous junctophilin-2 (JPH2) p.(Thr161Lys) is a monogenic cause for HCM with heart failure. PLoS One. (2018) 13(9):e0203422. 10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0203422

42.

Eberly LA Day SM Ashley EA Jacoby DL Jefferies JL Colan SD et al Association of race with disease expression and clinical outcomes among patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. JAMA Cardiol. (2020) 5(1):83–91. 10.1001/JAMACARDIO.2019.4638

Summary

Keywords

cardiovascular disease, Ecuadorian, genetics, genomics, healthcare, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

Citation

Paz-Cruz E, Guevara-Ramírez P, Tamayo-Trujillo R, Ruiz-Pozo VA, Cadena-Ullauri S, Ibarra-Castillo R, Laso-Bayas JL, Meza-Chico L, Cabrera-Andrade A and Zambrano AK (2026) Case Report: Genomic and clinical insights into MYBPC3-related hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in Ecuadorian patients: implications for sudden cardiac death risk. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 12:1693244. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1693244

Received

26 August 2025

Revised

15 December 2025

Accepted

29 December 2025

Published

21 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

DeLisa Fairweather, Mayo Clinic Florida, United States

Reviewed by

Catalina García-Vielma, Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social Delegación Nuevo León Centro de Investigación Biomédicas del Noreste, Mexico

María López Blázquez, Gregorio Marañón Hospital, Spain

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Paz-Cruz, Guevara-Ramírez, Tamayo-Trujillo, Ruiz-Pozo, Cadena-Ullauri, Ibarra-Castillo, Laso-Bayas, Meza-Chico, Cabrera-Andrade and Zambrano.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Ana Karina Zambrano anazambrano17@hotmail.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

ORCID Elius Paz-Cruz orcid.org/0000-0003-0062-6030 Patricia Guevara-Ramírez orcid.org/0000-0002-4829-3653 Rafael Tamayo-Trujillo orcid.org/0000-0001-9059-3281 Viviana A. Ruiz-Pozo orcid.org/0000-0001-9301-2614 Santiago Cadena-Ullauri orcid.org/0000-0001-8463-6046 Alejandro Cabrera-Andrade orcid.org/0000-0001-9702-6618 Ana Karina Zambrano orcid.org/0000-0003-4102-3965

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.