Abstract

Background:

Catheter ablation (CA) is a standard treatment for atrial fibrillation (AF); however, some patients experience worsening heart failure (WHF) afterward. The H2FPEF and HFA-PEFF scores are validated tools for HFpEF risk stratification, but their predictive value for WHF after CA in patients with preclinical heart failure (HF) remains unclear.

Method:

This retrospective, single-center observational study included 257 AF patients with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≥50% and no history or symptoms of HF who underwent first-time CA between February 2017 and September 2022. Patients were classified as high HFpEF score group if they had H2FPEF score ≥6 or HFA-PEFF score ≥5. The primary endpoint was WHF: HF hospitalization, initiation of oral diuretics, or intravenous administration of diuretics.

Results:

Among 257 patients, 54 (21.01%) were classified as high HFpEF score group. WHF incidence was significantly higher in the high HFpEF score group than in the low HFpEF score group (log-rank p < 0.001), while AF recurrence did not differ significantly (log-rank p = 0.546). In Firth's penalized logistic regression analysis, high HFA-PEFF score (HR 6.52, 95% CI 1.54–23.21, p = 0.014) and AF recurrence (HR 8.18, 95% CI 1.80–77.60, p = 0.005) appeared to be potential independent predictors of WHF.

Conclusions:

In this exploratory analysis, the HFA-PEFF score potentially represent an independent predictor of WHF after CA in AF patients with preclinical HF and preserved LVEF.

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common arrhythmia, with a growing prevalence worldwide (1). AF is associated with a significant risk of mortality and morbidity, including dementia, stroke, heart failure (HF), and reduced quality of life (2–4). Despite the availability of diverse treatment strategies, effective and individualized management of AF remains a clinical challenge.

Catheter ablation (CA) is widely adopted for rhythm control in patients with AF. While radiofrequency ablation has been the conventional approach, newer techniques such as cryoablation, hot balloon ablation, and pulsed-field ablation are increasingly used in clinical practice (5–7). CA has been routinely performed for approximately three decades, and the number of procedures continues to increase annually (8–10). Importantly, some patients undergoing CA may already be at risk for HF, even if they are in an asymptomatic, preclinical stage. The incidence of newly developed HF after ablation has been reported as 1.1 per 100 patient-year (11). This underscores the need to establish HF risk stratification as part of post-CA management, which has traditionally focused on preventing AF recurrence and the discontinuation of anticoagulant therapy (12–15). Among the various forms of HF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) is particularly relevant to risk stratification, as it shares several pathophysiological mechanisms with AF (16, 17). The H2FPEF and HFA-PEFF scores are commonly used to diagnose and predict HFpEF (18, 19), yet their utility in predicting HF events after CA remains unclear. In this study, we aimed to evaluate the incidence of WHF events following initial CA for AF and to determine whether HFpEF scoring systems—specifically the H2FPEF and HFA-PEFF scores—can aid in post-ablation risk stratification, particularly for identifying patients at risk of de novo WHF in the preclinical stage of HF.

Materials and methods

Study design and patient population

This single-center, retrospective observational study was conducted at Niigata University Medical and Dental Hospital. We included patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≥ 50% who underwent their first-time CA for AF between February 2017 and September 2022. All patients underwent pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) and were followed until November 2024. Eligible patients were considered to be in a preclinical HF, defined by the following criteria: no prior hospitalization for HF, New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class I, and no use of loop diuretics at the time of admission. The diagnosis of AF was established based on a prior electrocardiogram or 24-hour Holter monitoring. All echocardiographic examinations were performed in the clinical laboratories of our institution within 1 year prior to the CA session. LVEF was assessed using a two-dimensional echocardiographic method. Patients were excluded if they met any of the following criteria: (1) missing key echocardiographic parameters required to calculation of the H2FPEF and HFA-PEFF scores—specifically, tricuspid regurgitation pressure gradient, inferior vena cava diameter, or E/e′ ratio, (2) second or subsequent sessions, (3) moderate to severe aortic stenosis, (4) hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, or (5) history of dialysis. Among the excluded patients, only age and sex data were available for comparison, whereas information on AF subtype and heart failure states was not collected. Medical history, comorbidities, medications, and laboratory data were collected from electronic medical records. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by the institutional ethics committee.

H2FPEF and HFA-PEFF score

The H2FPEF score consists of six domains: (1) Heavy (Body mass index >30 kg/m2, 2 points), (2) Hypertension (2 or more antihypertensive medicines, 1 point), (3) AF (3 points), (4) Pulmonary Hypertension (Estimated Pulmonary artery systolic pressure >35 mmHg, 1 point), (5) Elder (Age > 60 years, 1 point), and (6) Filling Pressure (E/e′ > 9, 1 point). The total score ranges from 0 to 9, and a score ≥6 is defined as high risk for HFpEF (18). The HFA-PEFF score consists of 3 domains: (1) Functional (septal e′, lateral e′, E/e′, tricuspid regurgitation velocity, or global longitudinal strain), (2) Morphological (left atrial volume index, left ventricular mass index, relative wall thickness, or left ventricular wall thickness), and (3) Biomarker: N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) or brain natriuretic peptide (BNP). The HFA-PEFF score is categorized into major and minor criteria, with each fulfilled major criterion assigned 2 points and each fulfilled minor criterion assigned 1 point. The total score ranges from 0 to 6, with a score of ≥5 indicating a high likelihood of HFpEF (19). These scores were created originally for diagnosis of HFpEF, and it is unknown whether these scores can predict WHF. Both scores have been reported to have similar diagnostic abilities for HFpEF (20, 21); therefore, we combined them and examined the prognostic values for WHF to provide more comprehensive risk assessment. In this study, patients were classified into high HFpEF score group if they had either the H2FPEF score ≥6 or the HFA-PEFF score ≥5. The cutoff values for each score were based on the original definitions.

Procedure details of catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation

PVI or extended PVI was performed in all patients using either cryoballoon, radiofrequency ablation, or hot balloon ablation. Additional procedures—including left atrial posterior wall isolation, superior vena cava isolation, and cavotricuspid isthmus ablation—were performed at the discretion of the operator. Procedure-related complications resulting in delayed hospital discharge occurred in 9 patients. These included one case of access site bleeding, one retroperitoneal hematoma, four cases requiring permanent pacemaker implantation due to sick sinus syndrome, and three cases of cardiac tamponade requiring pericardial drainage. No procedure-related deaths occurred during the study period.

Study outcome

The primary outcome was WHF including follow events, defined by any of the following events: HF hospitalization, initiation of oral diuretics, or intravenous administration of diuretics (22–24). The oral diuretics include loop and thiazide diuretics. The initiation of thiazide diuretics was defined as WHF only when prescribed as diuretics therapy to relieve congestion and not for antihypertensive treatment. The secondary outcome was the AF recurrence or other supraventricular arrythmias. AF recurrence was defined as any documented episode detected on a 12-lead electrocardiogram, 24-hour Holter monitor, or implantable devices (permanent pacemaker, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, or cardiac resynchronization therapy devices) after the 3-month blanking period. For 24-hour Holter and device monitoring, AF episodes lasting ≥30 s were considered clinically significant. All events were corrected from the medical records.

Statistical analysis

Patients were categorized into two groups based on HFpEF risk: high HFpEF score group and low HFpEF score group, using the H2FPEF and HFA-PEFF criteria. Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed data or number (%). Group comparisons were performed using the Student's t-test for normally distributed data or the Mann–Whitney U test for non-normally distributed data. There were no missing data in the variables used for the analysis. Time-to-event outcomes including WHF and AF recurrence were assessed using Kaplan–Meier survival analysis, and differences between groups were evaluated with the log-rank test. In univariate regression analysis using Firth's penalized method, the following variables were examined: high H2FPEF score, high HFA-PEFF score, AF recurrence, age, male sex, hypertention, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, ischemic heart disease, beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi) or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI), MRAs, SGLT2i, hemoglobin (Hb), and creatinine (Cr). The variance inflation factor between the H2FPEF and HFA-PEFF scores was 1.1. In multivariate regression analysis using Firth's penalized method, high HFA-PEFF score and AF recurrence were included as independent variables. The sensitivity analysis including age, sex, HFA-PEFF score and AF recurrence were performed by Firth's penalized regression. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed to assess the predictive performance of the H2FPEF and HFA-PEFF scores for WHF. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using JMP version 17 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and R software version 4.4.2 (R Foundation, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Participants and baseline characteristics

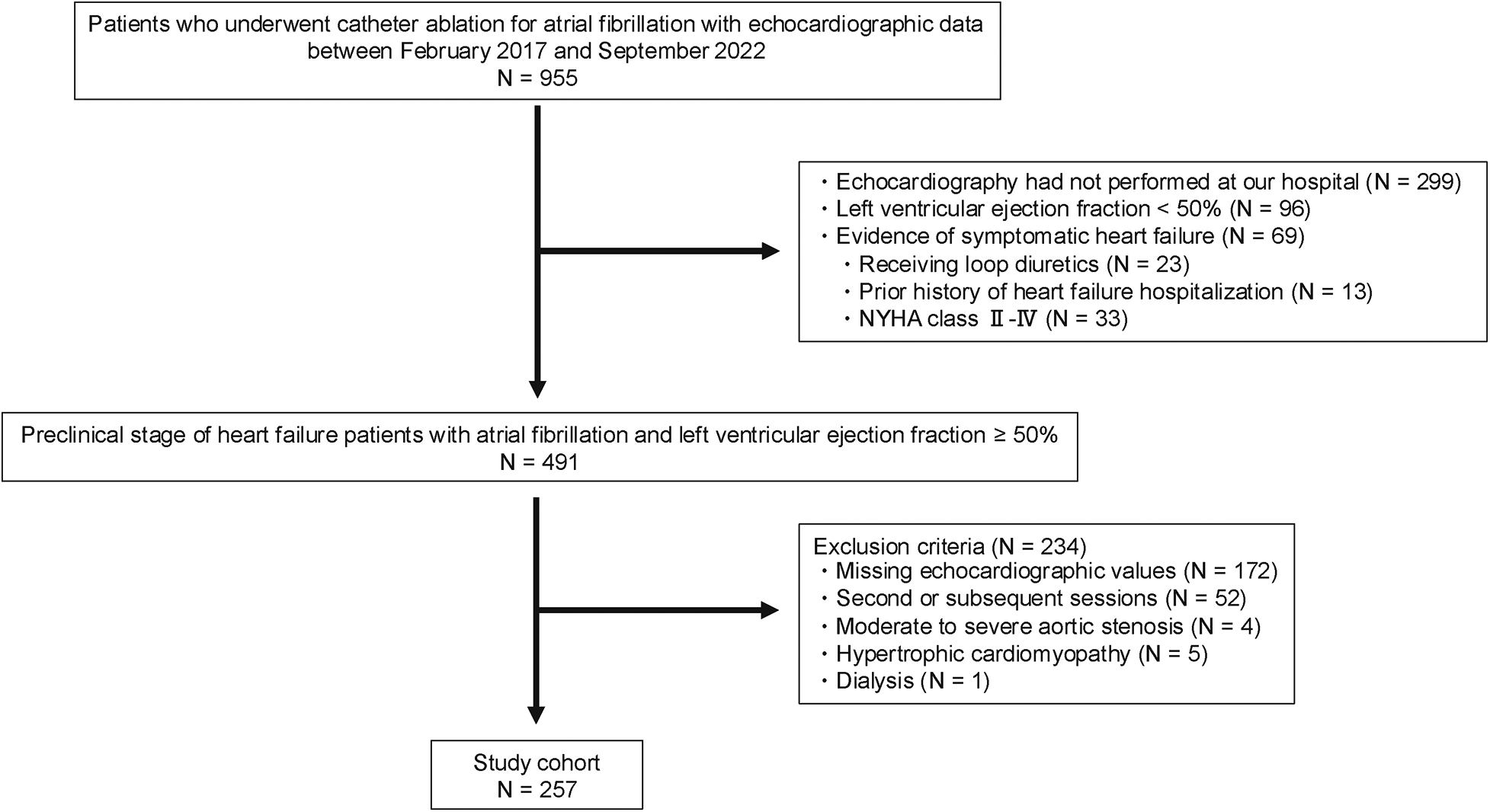

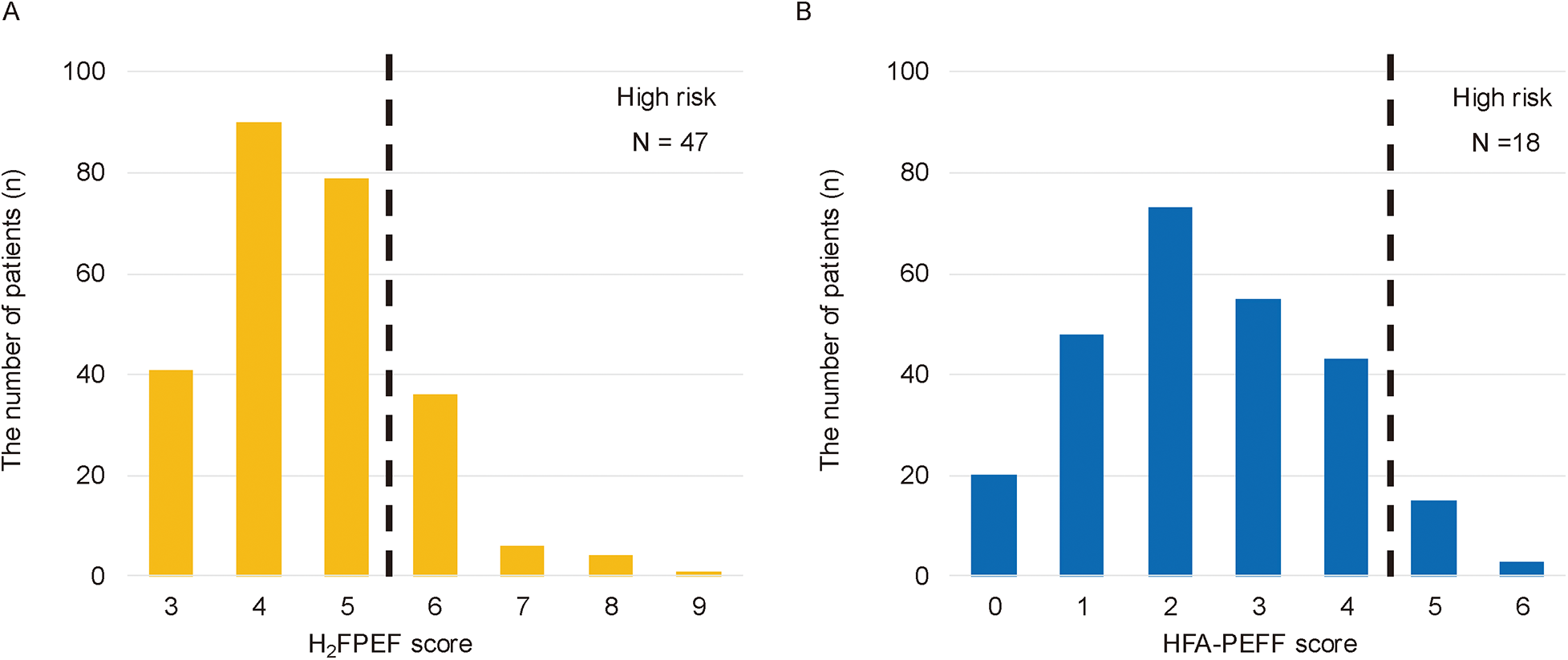

Among the 955 patients who underwent first-time CA for AF between February 2017 and September 2022, 299 were excluded due to echocardiographic examinations conducted at outside facilities. An additional 96 patients were excluded due to a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) < 50%, and 69 patients were excluded because of the evidence of symptomatic HF. Of the remaining 491 patients with preclinical HF, 234 were further excluded due to missing echocardiographic parameters (e.g., tricuspid regurgitation pressure gradient, inferior vena cava diameter, or E/e′ ratio; n = 172), second or subsequent CA sessions (n = 52), moderate to severe aortic stenosis (n = 4), hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (n = 5), or dialysis (n = 1). Finally, 257 patients were included in the analysis (Figure 1). Of these, 54 (21.01%) were classified into the high HFpEF score group and 203 into the low HFpEF score group based on HFpEF risk scores (Figure 2).

Figure 1

Flowchart of patient inclusion and exclusion in this study. NYHA, New York Heart Association.

Figure 2

The distribution of patients by H2FPEF or HFA-PEFF scores. The 47 patients (18.29%) were classified into the high HFpEF score group based on the H2FPEF score ≥6 (A), and the 18 patients (7.00%) based on the HFA-PEFF score ≥5 (B) The eleven patients overlapped between the two groups; therefore, a total of the 54 patients were categorized as the high HFpEF score group.

Baseline patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The overall mean age was 65 ± 10 years, 69.65% of patients were male, and the mean LVEF was 65.29 ± 6.06%. Compared with the low HFpEF score group, the high HFpEF score group was older (71 vs. 64 years, p < 0.001) and had a lower proportion of males (48.15% vs. 75.37%, p < 0.001). In addition, the high HFpEF score group had lower Hb levels (13.64 ± 1.43 vs. 14.30 ± 1.40 g/dL, p = 0.003), higher BNP levels (111.26 ± 93.61 vs. 62.30 ± 61.10 pg/mL, p < 0.001), and higher usage rates of beta-blockers (66.77% vs. 49.75%, p = 0.025), ACEi or ARBs (59.26% vs. 28.08%, p < 0.001). There were no significant differences between the groups in LVEF (p = 0.258) or AF pattern (paroxysmal vs. persistent, p = 0.549). There were no significant differences between the included and excluded patients (65 ± 10 vs. 64 ± 11 years, p = 0.095), or sex (male: 69.65% vs. 71.38%, p = 0.650).

Table 1

| Baseline characteristics | Total N = 257 | Low HFpEF score group N = 203 | High HFpEF score group N = 54 | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 65 ± 10 | 64 ± 11 | 71 ± 6 | <0.001 |

| Male, n (%) | 179 (69.65) | 153 (75.37) | 26 (48.15) | <0.001 |

| Height, cm | 165.78 ± 9.39 | 167.11 ± 8.91 | 160.79 ± 9.54 | <0.001 |

| Weight, kg | 64.95 ± 11.99 | 65.33 ± 11.45 | 63.53 ± 13.86 | 0.327 |

| BMI, kg/cm2 | 23.53 ± 3.42 | 23.27 ± 2.94 | 24.52 ± 4.72 | 0.090 |

| Medical history | ||||

| Persistent atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 91 (35.41) | 70 (34.48) | 21 (38.89) | 0.549 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 131 (50.97) | 89 (43.84) | 42 (77.78) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 32 (12.45) | 22 (10.84) | 10 (18.52) | 0.145 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 71 (27.63) | 53 (26.11) | 18 (33.33) | 0.298 |

| Ischemia heart disease, n (%) | 14 (5.45) | 9 (4.43) | 5 (9.26) | 0.192 |

| Clinical score | ||||

| CHADS2 score | 1.21 ± 1.10 | 1.12 ± 1.14 | 1.52 ± 0.84 | 0.001 |

| CHA2DS2VAsc score | 2.09 ± 1.48 | 1.89 ± 1.46 | 2.85 ± 1.32 | <0.001 |

| HAS-BLED score | 0.97 ± 0.89 | 0.91 ± 0.92 | 1.20 ± 0.74 | 0.003 |

| H2FPEF score | 4.58 ± 1.12 | 4.16 ± 0.73 | 6.17 ± 0.86 | <0.001 |

| HFA-PEFF score | 2.3 ± 1.38 | 2.06 ± 1.19 | 3.80 ± 1.22 | <0.001 |

| Laboratory date | ||||

| Hb, g/dL | 14.16 ± 1.43 | 14.30 ± 1.40 | 13.64 ± 1.43 | 0.003 |

| Cr, mg/dL | 0.84 ± 0.18 | 0.84 ± 0.17 | 0.84 ± 0.21 | 0.790 |

| BNP, pg/mL | 72.59 ± 71.76 | 62.30 ± 61.10 | 111.26 ± 93.61 | <0.001 |

| Echocardiography | ||||

| Heart rate, bpm | 72.22 ± 17.83 | 72.77 ± 18.29 | 70.17 ± 15.99 | 0.424 |

| LVDd, mm | 46.72 ± 4.39 | 46.82 ± 4.38 | 46.35 ± 4.47 | 0.489 |

| LVDs, mm | 29.96 ± 3.85 | 30.10 ± 3.85 | 29.46 ± 3.82 | 0.243 |

| LVEF, % | 65.29 ± 6.06 | 65.06 ± 6.19 | 66.14 ± 5.53 | 0.258 |

| IVST, mm | 9.38 ± 1.31 | 9.31 ± 1.29 | 9.64 ± 1.36 | 0.099 |

| PWT, mm | 9.07 ± 1.08 | 8.99 ± 1.07 | 9.36 ± 1.09 | 0.025 |

| septal e′, m/s | 8.45 ± 2.21 | 8.78 ± 2.34 | 7.31 ± 1.11 | 0.063 |

| E/E′ | 8.09 ± 2.39 | 7.33 ± 1.72 | 10.74 ± 2.59 | <0.001 |

| LAVI, mL/m2 | 41.50 ± 15.51 | 39.73 ± 14.58 | 48.09 ± 17.20 | <0.001 |

| TRV, m/s | 1.85 ± 0.83 | 1.74 ± 0.90 | 2.22 ± 0.25 | 0.103 |

| Drug | ||||

| Beta-blockers, n (%) | 137 (53.31) | 101 (49.75) | 36 (66.67) | 0.025 |

| ACE inhibitors or ARBs, n (%) | 89 (34.63) | 57 (28.08) | 32 (59.26) | <0.001 |

| ARNI, n (%) | 1 (0.39) | 1 (0.49) | 0 (0.00) | 0.492 |

| MRAs, n (%) | 6 (2.34) | 3 (1.48) | 3 (5.56) | 0.112 |

| SGLT2 inhibitors, n (%) | 4 (1.56) | 3 (1.48) | 1 (1.85) | 0.847 |

Patients characteristics.

ACEi, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors; ARBs, angiotensin Ⅱ receptor blockers; ARNI, angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor; BMI, body mass index; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; Cr, creatinine; Hb, hemoglobin; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; IVST, intraventricular septum thickness; LAVI, left atrial volume index; LVDd, left ventricular end-diastolic diameter; LVDs, left ventricular end-systolic diameter; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MRAs, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists; PWT, posterior wall thickness; SGLT2i, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors; TRV, tricuspid regurgitant velocity. Data are represented as mean ± standard deviation or number (%). P values were compared with low HFpEF score and high HFpEF score groups.

Incidence of worsening heart failure: primary endpoint analysis

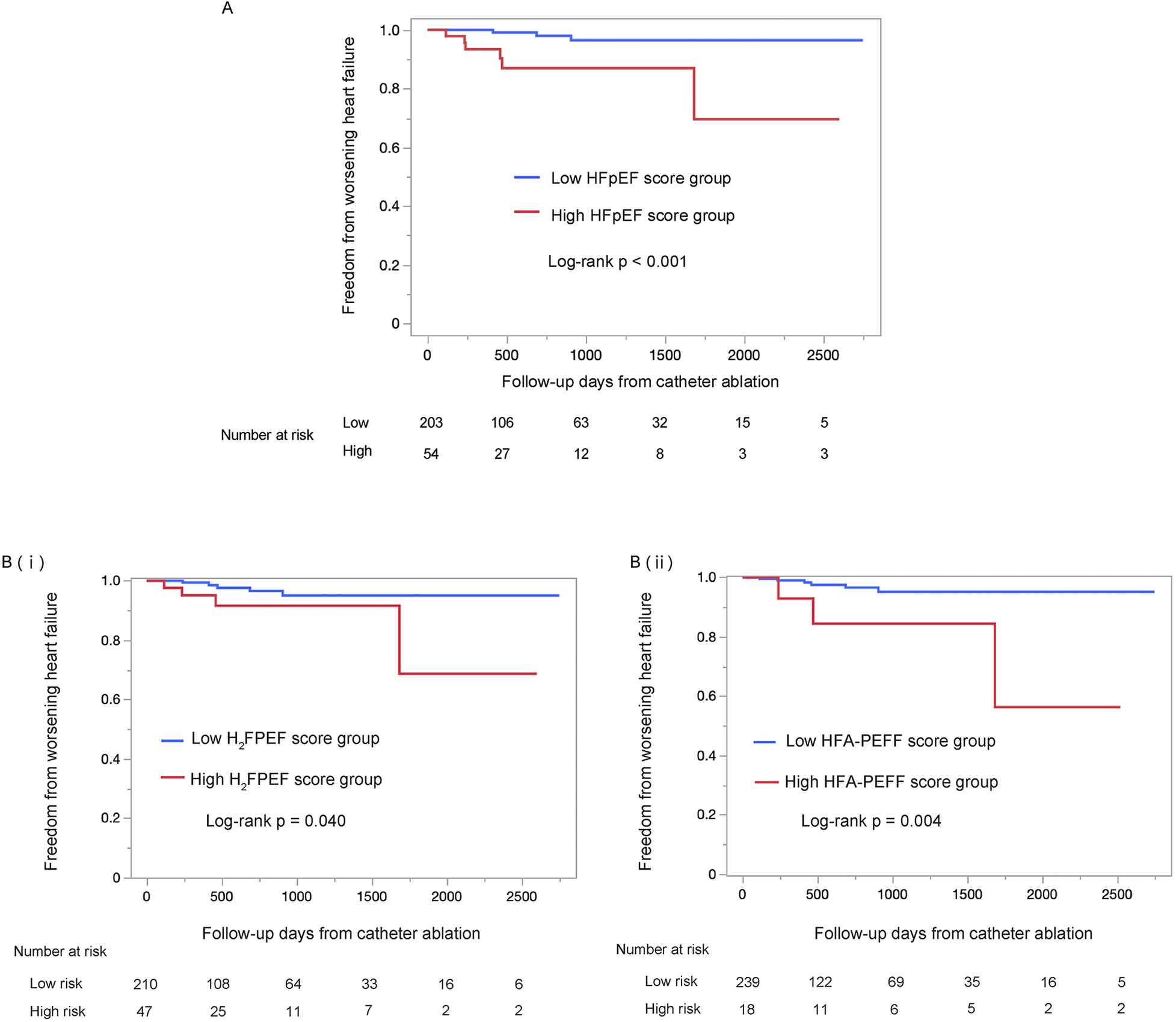

The median follow-up period was 557 days (interquartile range: 275–1,264 days), during which 9 WHF events occurred. WHF events were significantly more frequent in the high HFpEF score group than in the low HFpEF score group (log-rank p < 0.001; Figure 3A). This trend remained consistent when patients were stratified by either the H2FPEF score or the HFA-PEFF score individually [log-rank p = 0.040; Figure 3B(i), log-rank p = 0.004; Figure 3B(ii)]. In the low HFpEF score group, there were two initiations of oral diuretics, and one HF hospitalization. In contrast, in the high HFpEF score group, there were four initiations of oral diuretics, one intravenous admission of diuretics, and one HF hospitalization. No heart failure related deaths occurred during the follow-up period in either group. Detailed information on WHF events is provided in Supplementary Tables S1, S2.

Figure 3

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis of the worsening heart failure between the low HFpEF score and the high HFpEF score groups, using the log-rank test. The high HFpEF score group was defined as patients who had either the H2FPEF score ≥6 or the HFA-PEFF score ≥5 (A). The analysis using each score individually are shown in (B) (i) and (ii), respectively. The high HFpEF score group was defined as H2FPEF score ≥6 (i) or HFA-PEFF score ≥5 (ii). HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction.

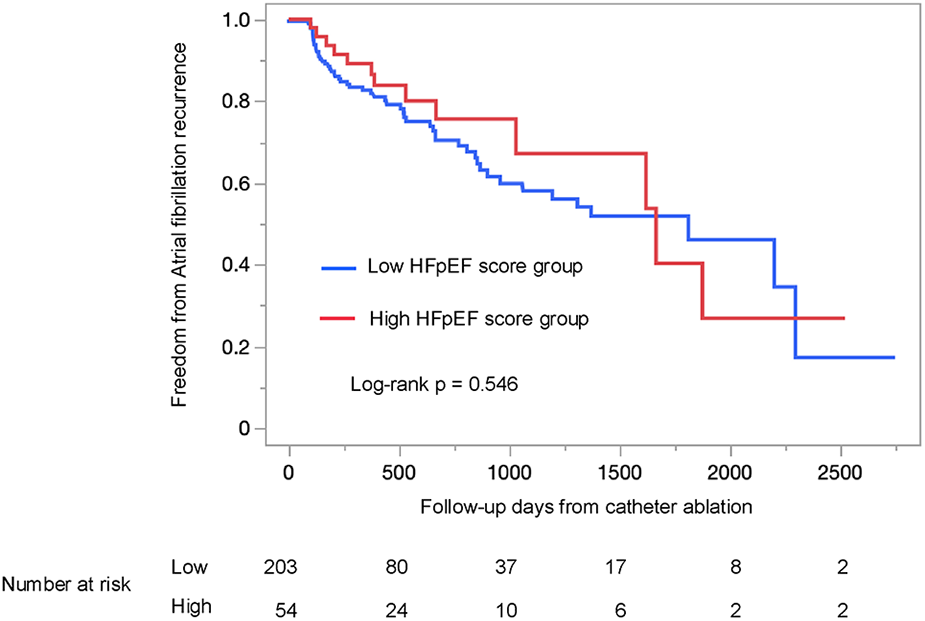

Atrial fibrillation recurrence rates: secondary endpoint analysis

The AF recurrence rate did not significantly differ between the two groups (log-rank p = 0.546; Figure 4). This trend remained consistent when patients were stratified by either the H2FPEF score or the HFA-PEFF score individually (log-rank p = 0.597; Supplementary Figure S1A, log-rank p = 0.639; Supplementary Figure S1B).

Figure 4

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis of atrial fibrillation recurrence between the low HFpEF score and the high HFpEF score groups, using the log-rank test. The high HFpEF score group was defined as patients who had either the H2FPEF score ≥6 or the HFA-PEFF score ≥5. HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction.

Risk factors for worsening heart failure

In univariable regression analysis using Firth's penalized method, both the high HFA-PEFF score and AF recurrence were significantly associated with WHF (Table 2). In multivariate analysis using Firth's penalized method, the high HFA-PEFF score and AF recurrence remained to be potential independent predictors of WHF (HR 6.52, 95% CI 1.54–23.21, p = 0.014; HR 8.18, 95% CI 1.80–77.60, p = 0.005, respectively). In addition, the sensitivity analysis using Firth's penalized regression was performed including age, sex, high HFA-PEFF score, and AF recurrence. The High HFA-PEFF score and AF recurrence remained significantly associated with WHF (HR 7.14, 95% CI 1.50–32.06, p = 0.015; HR 7.79, 95% CI 1.71–74.06, p = 0.006, respectively), while age and sex were not significant (Supplementary Table S3).

Table 2

| Covariates | Univariate | Multivariate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p value | HR | 95% CI | p value | |

| High H2FPEF score | 3.71 | (0.99–13.14) | 0.051 | |||

| High HFA-PEFF score | 6.66 | (1.57–23.67) | 0.013 | 6.52 | (1.54–23.21) | 0.014 |

| AF recurrence | 8.29 | (1.82–78.68) | 0.005 | 8.18 | (1.80–77.60) | 0.005 |

| Age | 1.00 | (0.94–1.07) | 0.985 | |||

| Male | 0.63 | (0.18–2.65) | 0.476 | |||

| Hypertension | 1.15 | (0.30–5.47) | 0.827 | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.58 | (0.17–7.08) | 0.627 | |||

| Dyslipidemia | 2.10 | (0.56–7.41) | 0.254 | |||

| Ischemic heart disease | 1.11 | (0.01–8.87) | 0.946 | |||

| Beta-blockers | 0.31 | (0.06–1.16) | 0.084 | |||

| ACE inhibitors or ARBs | 2.07 | (0.59–7.74) | 0.252 | |||

| ARNI | 12.66 | (0.10–107.93) | 0.208 | |||

| MRAs | 6.00 | (0.63–27.49) | 0.102 | |||

| SGLT2 inhibitors | 5.92 | (0.05–50.30) | 0.337 | |||

| Hb | 1.22 | (0.76–1.98) | 0.414 | |||

| Cr | 0.27 | (0.01–5.11) | 0.472 | |||

Firth's penalized regression analysis for worsening heart failure after first-time catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation.

ACEi, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors; AF, atrial fibrillation; ARBs, angiotensinⅡreceptor blockers; ARNI, angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor; CI, confidence interval; Cr, creatinine; Hb, hemoglobin; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HR, hazard ratio; MRAs, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists; SGLT2i, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors.

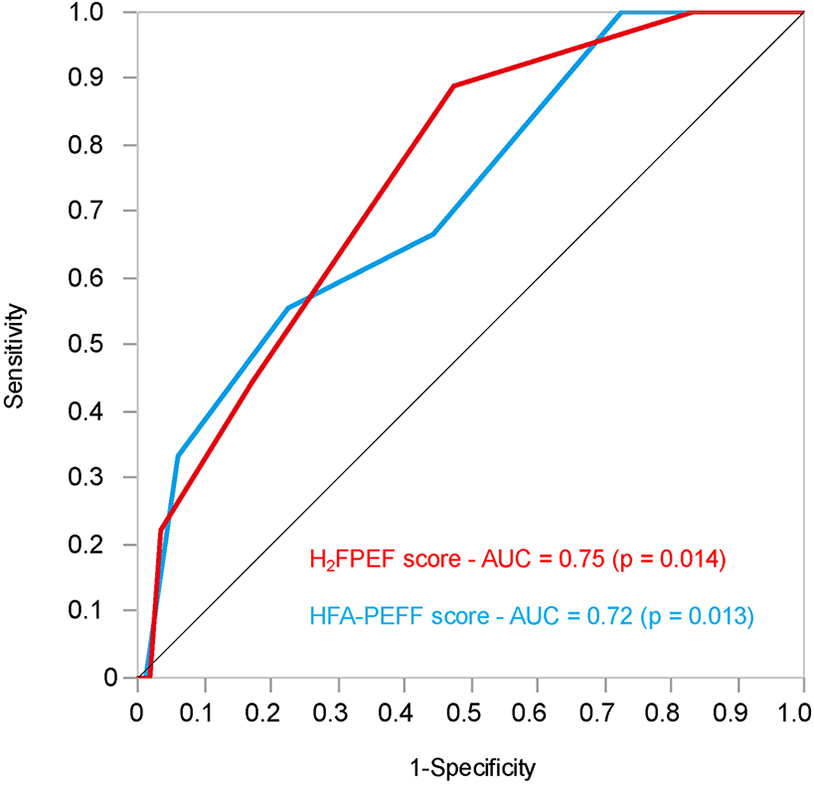

Receiver operating characteristics analysis for predicting worsening heart failure of the H2FPEF and HFA-PEFF scores

To evaluate the predictive performance of the H2FPEF and HFA-PEFF scores for WHF after CA for AF, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was performed (Figure 5). The area under the curve (AUC) values for the H2FPEF and HFA-PEFF scores were 0.75 (p = 0.014) and 0.72 (p = 0.013), respectively. An H2FPEF score ≥6 yielded a sensitivity of 44.44% and specificity of 82.66%, while an HFA-PEFF score ≥5 yielded a sensitivity of 33.33% and specificity of 94.00%. The optimal cutoff values for predicting WHF after first-time CA for AF were 5 for the H2FPEF score (sensitivity 88.89%, specificity 52.42%) and 4 for HFA-PEFF score (sensitivity 55.66%, specificity 77.42%).

Figure 5

The receiver operating characteristics analysis of the H2FPEF and HFA-PEFF scores to predict the worsening heart failure after first-time catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation in patients with preserved ejection fraction. AUC, area under the curve.

Discussion

This study revealed the following five findings: (1) Among asymptomatic patients with preclinical HF and preserved LVEF who underwent CA for AF, approximately 20% were classified as high risk for HFpEF according to either of the two risk scores systems; (2) Patients in the high HFpEF score group had a significantly higher incidence of WHF than those in the low score group; (3) There was no significant difference in AF recurrence between the two groups; (4) A high HFA-PEFF score and AF recurrence were identified as independent risk factors of WHF in multivariate analysis, and (5) The most appropriate cut-off values for predicting WHF after first-time CA for AF were 5 for the H2FPEF score and 4 for the HFA-PEFF score in this study. These results may suggest that evaluating HFpEF risk in patients with preclinical HF undergoing first-time CA for AF is important, regardless of procedural success. Moreover, when using these scores for risk stratification, alternative cutoff values may be more appropriate for predicting WHF in this population.

Non-negligible incidence of worsening heart failure events

In this study, nearly 20% of preclinical HF patients with preserved LVEF who underwent CA for AF were classified as high risk for HFpEF, and WHF events occurred in 9 out of 257 patients (3.50%) during the follow-up period. The study population corresponds to stage A or B HF, and previous reports indicate that 1%–6% of such patients progress to stage C or D within 4 years (25). However, limited evidence exists regarding HF progression in patients with stage A or B who have preserved LVEF and coexisting AF. Our finding—that a substantial proportion of asymptomatic AF patients were stratified as high risk, and that a non-negligible number subsequently developed WHF—suggests underlying vulnerability in this population. AF contributes to HF development and progression via mechanisms such as impaired atrial contractility and structural remodeling, including left atrial fibrosis and dilation (16). Conversely, HF can promote AF through elevated sympathetic activity, increased left ventricular filling pressure (26), atrial remodeling and dysfunction (27). These bidirectional interactions suggest a mutually reinforcing pathophysiological relationship between AF and HF. In addition, the coexistence of AF and HFpEF is associated with poor prognosis, including higher mortality and increased risk of WHF (28). Thus, in pre-clinical HF patients with AF, it is important to evaluate atrial and diastolic function (29). In our study, high HFpEF score group experienced a higher incidence of WHF after first-time CA for AF. These findings suggest that some patients with AF-related HF may already have a subclinical but advanced HF state prior to CA—one that CA alone may not fully address. Several previous studies have validated the prognostic value of HFpEF risk scores for HF (30, 31); however, few studies have examined the prognostic values of HFpEF risk scores for de novo HF in preclinical HF patients with AF. This study indicated that pre-CA risk stratification using these scores could be useful tools to guide post-CA management for WHF.

Implications for long-term management of heart failure after catheter ablation

Long-term management after successful CA for AF has become an increasingly important clinical issue. In particular, the prevention of AF recurrence and decisions regarding the continuation of anticoagulation therapy remain topics of ongoing debate. Reported recurrence rates range from 20% to 40% (32), indicating the importance of post CA follow-up. Pre-procedural risk stratification and post-procedural strategies—including corticosteroids, ACEi, and SGLT2i—have been explored to mitigate recurrence (12–14). Although current guidelines do not provide specific recommendations for recurrence prevention, close monitoring is especially important in patients identified as high risk. Established risk factors for AF recurrence include age, left atrial size, duration of AF, and a history of CA (33, 34). However, in this study, HFpEF scores did not predict AF recurrence, suggesting their limited role in recurrence risk assessment.

In this study, we focused on the incidence of WHF after CA. CA for patients with AF and concomitant HF has been generally associated with improved exercise tolerance, increased LVEF, and reduced HF hospitalizations, regardless of baseline LVEF (35–37). These findings suggest that recurrent AF may contribute to the development or WHF. Indeed, in our multivariate analysis, AF recurrence was identified as an independent risk factor for WHF. Careful monitoring is therefore warranted in patients who experience AF recurrence after CA, regardless of their HFpEF risk status. Conversely, in this study, patients classified as high risk by HFpEF scoring systems experienced a higher incidence of WHF events after CA. This finding indicates that WHF can develop independently of AF recurrence, highlighting the need to establish predictive strategies that are distinct from recurrence-based assessments. In addition, only the HFA-PEFF score was identified as an independent predictor of WHF, whereas H2FPEF score was not. Although exploratory, the HFA-PEFF score may have better prognostic ability for predicting WHF. This may be because the H2FPEF score mainly consists of general risk factors such as body mass index and age, whereas the HFA-PEFF score includes more HF-specific parameters, including echocardiographic indices. Finally, we used the H2FPEF and HFA-PEFF scores to stratify HF risk and categorized patients according to previously reported thresholds. However, these thresholds were originally developed for the diagnosis of HFpEF, not for predicting future HF events (18, 19). Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis identified optimal cut-off values of 5 points for the H2FPEF score and 4 points for the HFA-PEFF score. These results may suggest that revised thresholds may be more appropriate for predicting WHF after CA; however, the estimates of the AUC and the optimal cut-off values are likely to be unstable because of the small number of WHF events. Therefore, the validation in a larger population is required in future studies.

Limitation

There are some limitations in this study. First, initiation of thiazide diuretics was included as part of the definition of WHF, although this is not commonly used for this purpose in recent clinical studies. Second, symptomatic patients may not have been completely excluded from the study cohort. Patients with HF who were not taking loop diuretics may have been included. Third, this is a single-center, retrospective observational study with a relatively small cohort size and a limited number of events. The study results, especially those from the Cox regression analysis, may be unstable because age and sex, which were significantly different at the baseline, were not included in the model. Although the results were similar in the sensitivity analysis, the statistical model may have been overfitted and the study results require cautious interpretation. Fourth, the ROC analysis requires cautious interpretation because of the small number of WHF events. Finally, the study data were retrospectively extracted from medical records, which may limit the generalizability of the findings.

Conclusion

In this exploratory analysis, the HFA-PEFF score potentially represent an independent predictor of WHF after first-time CA for AF in patients with preclinical HF and preserved LVEF (≥50%). This score may be useful for WHF management after CA for AF; however, further validation in a larger population is required before these findings can be applied clinically.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the deidentified participant data will not be shared. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Shinya Fujiki, sfujiki@med.niigata-u.ac.jp.

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Niigata University (Approval no.: Niigata University 2024-0251). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

SH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SF: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. AM: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. SS: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. IH: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. KT: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. YS: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. HT: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. TKu: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. NS: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. RS: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. YI: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. YH: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. SO: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. HK: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. TT: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. TKa: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. TI: Conceptualization, Project administration, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Acknowledgments

This study was registered with the University Hospital Medical Information Network in Japan (UMIN Registration Number: UMIN- 000056827).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used Chat GPT in order to correct grammatical mistakes.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcvm.2025.1704164/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Schnabel RB Yin X Gona P Larson MG Beiser AS McManus DD et al 50 Year trends in atrial fibrillation prevalence, incidence, risk factors, and mortality in the Framingham heart study: a cohort study. Lancet. (2015) 386:154–62. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61774-8

2.

de Bruijn RFAG Heeringa J Wolters FJ Franco OH Stricker BHC Hofman A et al Association between atrial fibrillation and dementia in the general population. JAMA Neurol. (2015) 72:1288. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.2161

3.

Wolf PA Abbott RD Kannel WB . Atrial fibrillation as an independent risk factor for stroke: the Framingham study. Stroke. (1991) 22:983–8. 10.1161/01.STR.22.8.983

4.

Wang TJ Larson MG Levy D Vasan RS Leip EP Wolf PA et al Temporal relations of atrial fibrillation and congestive heart failure and their joint influence on mortality: the Framingham heart study. Circulation. (2003) 107:2920–5. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000072767.89944.6E

5.

Wazni OM Dandamudi G Sood N Hoyt R Tyler J Durrani S et al Cryoballoon ablation as initial therapy for atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. (2021) 384:316–24. 10.1056/NEJMoa2029554

6.

Sohara H Takeda H Ueno H Oda T Satake S . Feasibility of the radiofrequency hot balloon catheter for isolation of the posterior left atrium and pulmonary veins for the treatment of atrial fibrillation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. (2009) 2:225–32. 10.1161/CIRCEP.108.817205

7.

Reddy VY Koruth J Jais P Petru J Timko F Skalsky I et al Ablation of atrial fibrillation with pulsed electric fields. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. (2018) 4:987–95. 10.1016/j.jacep.2018.04.005

8.

Joglar JA Chung MK Armbruster AL Benjamin EJ Chyou JY Cronin EM et al 2023 ACC/AHA/ACCP/HRS guideline for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. (2024) 149:e1–156. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001193

9.

Nogami A Kurita T Abe H Ando K Ishikawa T Imai K et al JCS/JHRS 2019 guideline on non-pharmacotherapy of cardiac arrhythmias. Circ J. (2021) 85:1104–244. 10.1253/circj.CJ-20-0637

10.

Hsu JC Darden D Du C Marine JE Nichols S Marcus GM et al Initial findings from the national cardiovascular data registry of atrial fibrillation ablation procedures. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2023) 81:867–78. 10.1016/j.jacc.2022.11.060

11.

Ngo L Woodman R Denman R Walters TE Yang IA Ranasinghe I . Longitudinal risk of death, hospitalizations for atrial fibrillation, and cardiovascular events following catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation: a cohort study. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. (2023) 9:150–60. 10.1093/ehjqcco/qcac024

12.

Koyama T Tada H Sekiguchi Y Arimoto T Yamasaki H Kuroki K et al Prevention of atrial fibrillation recurrence with corticosteroids after radiofrequency catheter ablation. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2010) 56:1463–72. 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.04.057

13.

Peng L Li Z Luo Y Tang X Shui X Xie X et al Renin-angiotensin system inhibitors for the prevention of atrial fibrillation recurrence after ablation - a meta-analysis. Circ J. (2020) 84:1709–17. 10.1253/circj.CJ-20-0402

14.

Liu H-T Wo H-T Chang P-C Lee H-L Wen M-S Chou C-C . Long-term efficacy of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor therapy in preventing atrial fibrillation recurrence after catheter ablation in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Heliyon. (2023) 9:e16835. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e16835

15.

Kanaoka K Nishida T Iwanaga Y Nakai M Tonegawa-Kuji R Nishioka Y et al Oral anticoagulation after atrial fibrillation catheter ablation: benefits and risks. Eur Heart J. (2024) 45:522–34. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad798

16.

Anter E Jessup M Callans DJ . Atrial fibrillation and heart failure: treatment considerations for a dual epidemic. Circulation. (2009) 119:2516–25. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.821306

17.

Coiro S Verdecchia P Angeli F . When the responsibility for a crime is shared between several actors. The case of hypertensive heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Intern Med. (2024) 120:29–31. 10.1016/j.ejim.2023.11.022

18.

Reddy YNV Carter RE Obokata M Redfield MM Borlaug BA . A simple, evidence-based approach to help guide diagnosis of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circulation. (2018) 138:861–70. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.034646

19.

Pieske B Tschöpe C de Boer RA Fraser AG Anker SD Donal E et al How to diagnose heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: the HFA–PEFF diagnostic algorithm: a consensus recommendation from the heart failure association (HFA) of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. (2019) 40:3297–317. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz641

20.

Sepehrvand N Alemayehu W Dyck GJB Dyck JRB Anderson T Howlett J et al External validation of the H2 F-PEF model in diagnosing patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. Circulation. (2019) 139:2377–9. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.038594

21.

Barandiarán Aizpurua A Sanders-van Wijk S Brunner-La Rocca H-P Henkens M Heymans S Beussink-Nelson L et al Validation of the HFA-PEFF score for the diagnosis of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. (2020) 22:413–21. 10.1002/ejhf.1614

22.

Madelaire C Gustafsson F Stevenson LW Kristensen SL Køber L Andersen J et al One-year mortality after intensification of outpatient diuretic therapy. J Am Heart Assoc. (2020) 9:e016010. 10.1161/JAHA.119.016010

23.

Fudim M Egolum U Haghighat A Kottam A Sauer AJ Shah H et al Surveillance and alert-based multiparameter monitoring to reduce worsening heart failure events: results from SCALE-HF 1. J Card Fail. (2025) 31:661–75. 10.1016/j.cardfail.2024.08.050

24.

Chaudhary RS Hussain SMD Wang Y-S Komtebedde J Hasenfuß G Borlaug BA et al Expanded definition of worsening heart failure. JACC Heart Fail. (2025) 13:102571. 10.1016/j.jchf.2025.102571

25.

Young KA Scott CG Rodeheffer RJ Chen HH . Progression of preclinical heart failure: a description of stage A and B heart failure in a community population. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. (2021) 14:e007216. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.120.007216

26.

Vandenberk B Haemers P Morillo C . The autonomic nervous system in atrial fibrillation—pathophysiology and non-invasive assessment. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2024) 10:1327387. 10.3389/fcvm.2023.1327387

27.

Borlaug BA Sharma K Shah SJ Ho JE . Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2023) 81:1810–34. 10.1016/j.jacc.2023.01.049

28.

Sartipy U Dahlström U Fu M Lund LH . Atrial fibrillation in heart failure with preserved, mid-range, and reduced ejection fraction. JACC Heart Fail. (2017) 5:565–74. 10.1016/j.jchf.2017.05.001

29.

Beltrami M Palazzuoli A Padeletti L Cerbai E Coiro S Emdin M et al The importance of integrated left atrial evaluation: from hypertension to heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Int J Clin Pract. (2018) 72:e13050. 10.1111/ijcp.13050

30.

Sumiyoshi H Tasaka H Yoshida K Yoshino M Kadota K . Heart failure score and outcomes in patients with preserved ejection fraction after catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation. ESC Heart Fail. (2024) 11:2986–98. 10.1002/ehf2.14876

31.

Ariyaratnam JP Mishima RS Kadhim K Emami M Fitzgerald JL Thiyagarajah A et al Utility and validity of the HFA-PEFF and H2FPEF scores in patients with symptomatic atrial fibrillation. JACC Heart Fail. (2024) 12:1015–25. 10.1016/j.jchf.2024.01.015

32.

Kobza R Hindricks G Tanner H Schirdewahn P Dorszewski A Piorkowski C et al Late recurrent arrhythmias after ablation of atrial fibrillation: incidence, mechanisms, and treatment. Heart Rhythm. (2004) 1:676–83. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2004.08.009

33.

Kornej J Hindricks G Arya A Sommer P Husser D Bollmann A . The APPLE score—a novel score for the prediction of rhythm outcomes after repeat catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation. PLoS One. (2017) 12:e0169933. 10.1371/journal.pone.0169933

34.

Winkle RA Jarman JWE Mead RH Engel G Kong MH Fleming W et al Predicting atrial fibrillation ablation outcome: the CAAP-AF score. Heart Rhythm. (2016) 13:2119–25. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2016.07.018

35.

Hunter RJ Berriman TJ Diab I Kamdar R Richmond L Baker V et al A randomized controlled trial of catheter ablation versus medical treatment of atrial fibrillation in heart failure (the CAMTAF trial). Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. (2014) 7:31–8. 10.1161/CIRCEP.113.000806

36.

Marrouche NF Brachmann J Andresen D Siebels J Boersma L Jordaens L et al Catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation with heart failure. N Engl J Med. (2018) 378:417–27. 10.1056/NEJMoa1707855

37.

Chieng D Sugumar H Segan L Tan C Vizi D Nanayakkara S et al Atrial fibrillation ablation for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. JACC Heart Fail. (2023) 11:646–58. 10.1016/j.jchf.2023.01.008

Summary

Keywords

atrial fibrillation, catheter ablation, H2FPEF score, HFA-PEFF score, HFpEF

Citation

Hirayama S, Fujiki S, Maekawa A, Sato S, Ikesugi H, Tanaka K, Sekiya Y, Tsuchiya H, Kumaki T, Suzuki N, Sakai R, Ikami Y, Hasegawa Y, Otsuki S, Kayamori H, Takayama T, Kashimura T and Inomata T (2026) HFA-PEFF score as a predictor of worsening heart failure after first-time catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation in patients with preclinical heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 12:1704164. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1704164

Received

12 September 2025

Revised

18 December 2025

Accepted

23 December 2025

Published

20 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Matteo Cameli, University of Siena, Italy

Reviewed by

Stefano Coiro, Hospital of Santa Maria della Misericordia in Perugia, Italy

Mehrdad Mahalleh, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Iran

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Hirayama, Fujiki, Maekawa, Sato, Ikesugi, Tanaka, Sekiya, Tsuchiya, Kumaki, Suzuki, Sakai, Ikami, Hasegawa, Otsuki, Kayamori, Takayama, Kashimura and Inomata.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Shinya Fujiki sfujiki@med.niigata-u.ac.jp

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.