Abstract

Background:

Esophageal fistula (EF) is a rare but devastating complication following atrial fibrillation (AF) ablation. Data regarding the impact of age on EF are scarce.

Objective:

To study the impact of age on the management and prognosis of EF following catheter ablation for AF.

Methods:

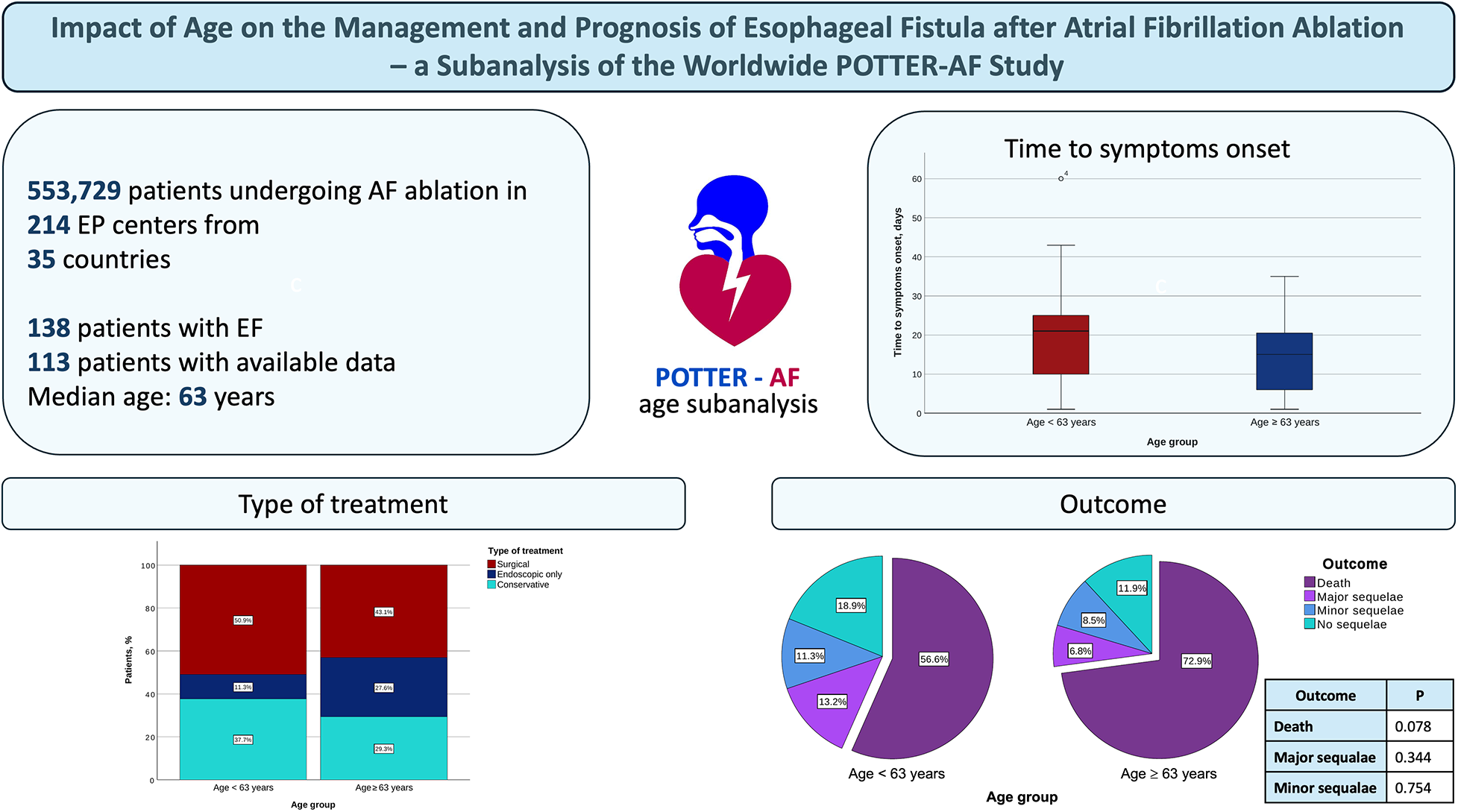

The POTTER-AF study is a worldwide registry on EF following catheter ablation for AF. A total of 553,729 patients underwent AF ablation in 214 centers between 1996 and 2022. Of them, 138 patients experienced EF, and data regarding age, management, and prognosis were available in 113 patients. The population was divided based on the median age.

Results:

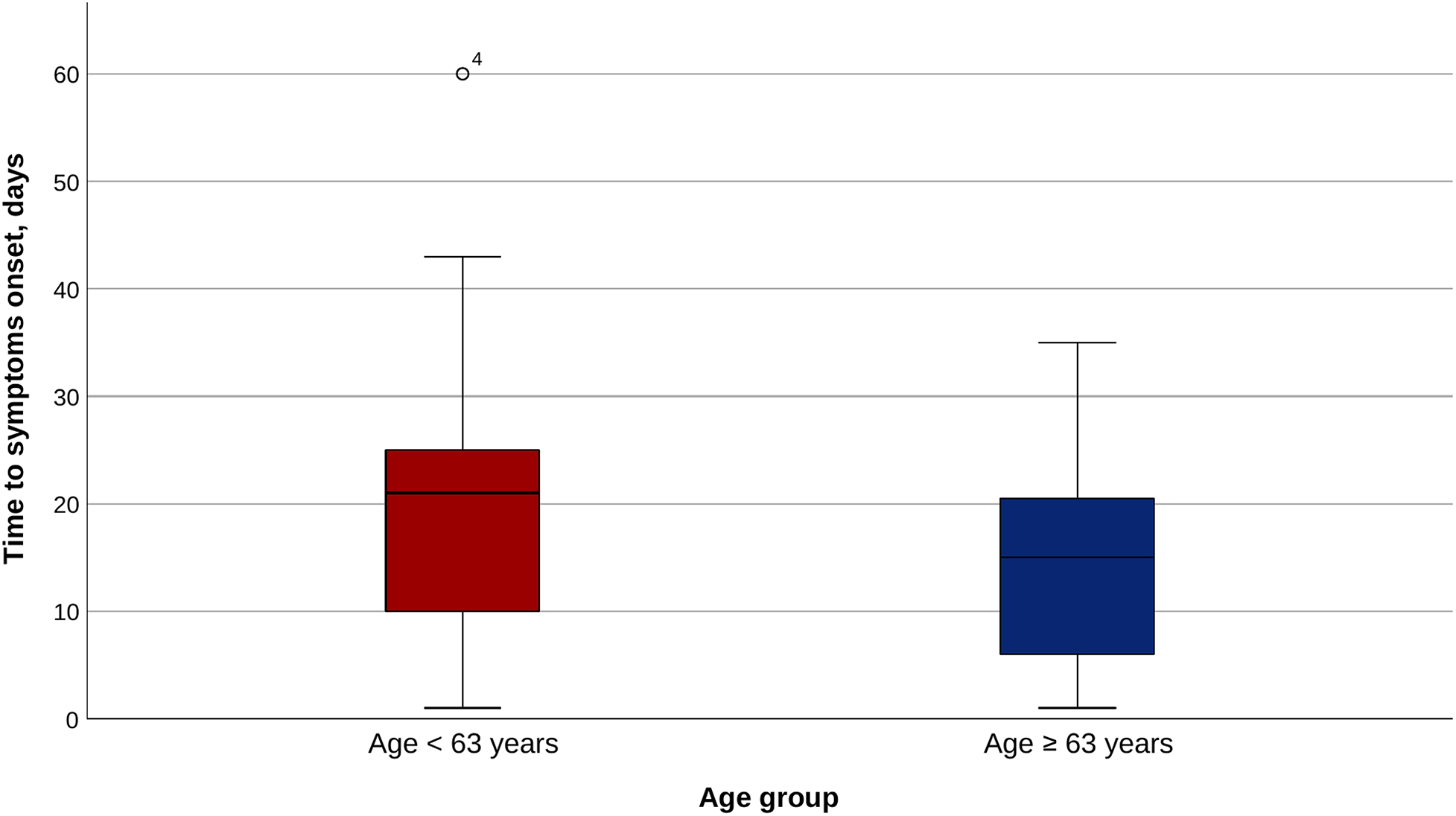

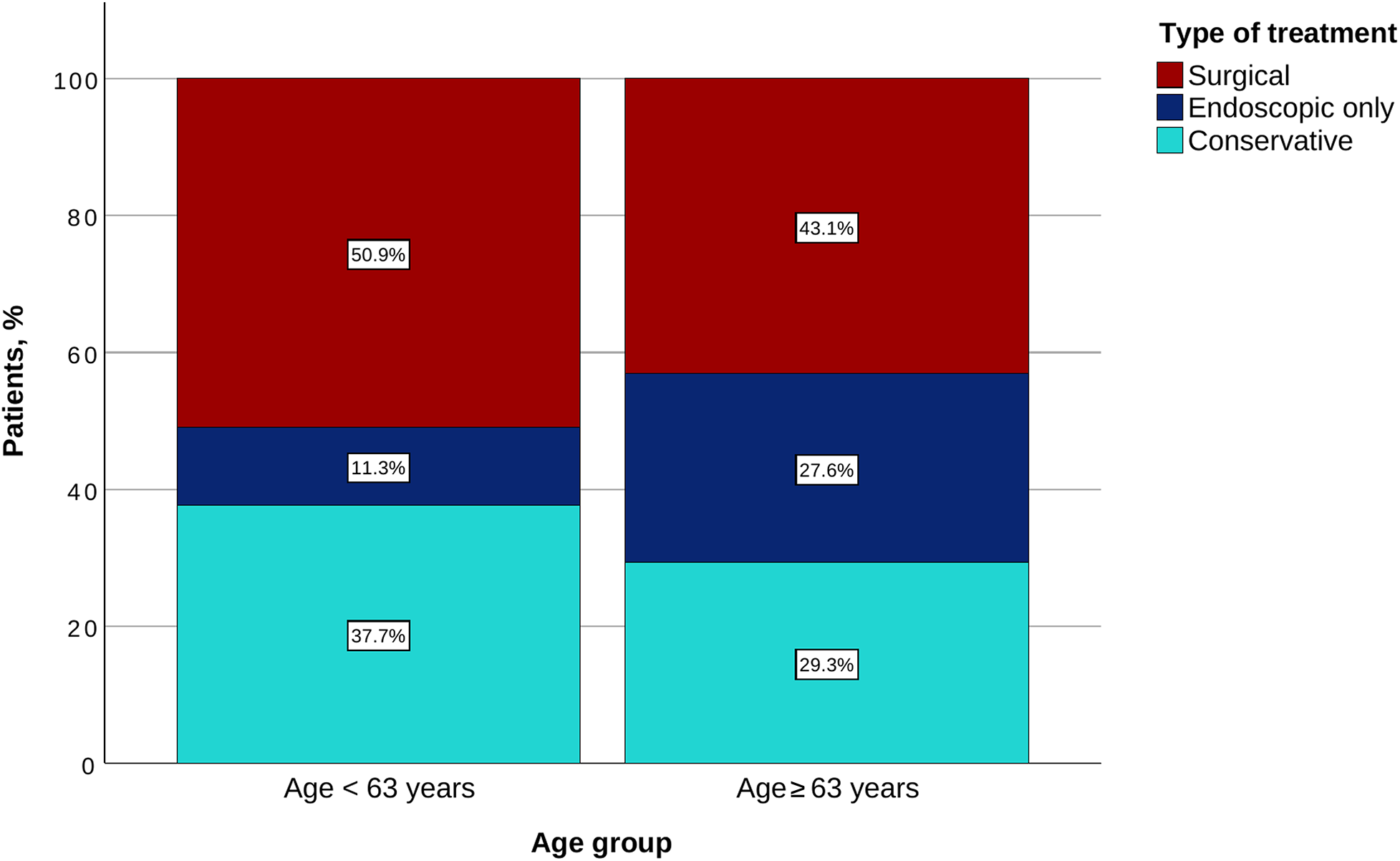

The median age was 63 years; 54 patients were <63 years old (Group 1), and 59 patients were ≥63 years old (Group 2). The groups were similar regarding procedural characteristics. The older population had a shorter time to symptom onset [15.0 (6.0, 21.0) vs. 21.0 (10.0, 25.3) days; p = 0.031]. Group 2 was less likely to receive a brain CT or MRI for diagnosis (25.9% vs. 45.3%; p = 0.046). The older population was more likely to undergo endoscopic treatment without surgery (27.6% vs. 11.3%; p = 0.035). Conservative and surgical treatments were used in similar proportions. A trend toward higher fatality was noted in the older patients (72.9% vs. 56.6%; p = 0.078).

Conclusion:

The older population had a shorter time to symptom onset, was less likely to receive a brain CT or MRI, and more likely to be treated by an endoscopic approach only. The older patient group showed a trend toward a higher fatality.

Graphical Abstract

AF, atrial fibrillation; EF, esophageal fistula; EP, electrophysiological.

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common arrhythmia in adults, and its prevalence is expected to double in the next few decades, posing a high burden on the healthcare systems worldwide (1, 2). Catheter ablation is the cornerstone of the rhythm control strategy and is recommended as first-line therapy in patients with paroxysmal AF and second-line therapy in those with persistent AF (2, 3).

Due to solid validation and increased operator experience, thermal ablation remains the most used technology today, with cryoballoon- and radiofrequency-based catheter ablation performed on a wide scale worldwide (4–8). Although the safety profile of these technologies improved over time due to significant technological improvements, thermal-related complications such as pulmonary vein stenosis, phrenic nerve palsy, and esophageal fistulas (EFs) cannot be completely avoided (9–14).

EF is rare but has a high fatality rate (11, 12, 14, 15). The recently published POTTER-AF study was the largest to date to investigate the incidence, management, and prognosis of EF following AF and atrial tachycardia ablation. The study reported an overall EF incidence of 0.025% and an overall fatality of 65.8%, rising up to 89.5% among patients treated conservatively (11). The anatomical proximity between the left atrium and the esophagus is a determining factor in the development of EF, and the lack of fatty tissue between the two structures increases the risk (16). In obese patients, the risk of EF formation is therefore decreased (17). There are several hypotheses on the development of atrioesophageal fistula after catheter ablation including direct thermal effects, ischemia of the esophageal mucosa via occlusion of an esophageal artery, or nerve lesions resulting in motility disorders (16, 17). As an empirical measure, mucosal protection via proton pump inhibitors (PPI) postprocedurally might be efficient in preventing the complication and is widely implemented (3, 18, 19). Esophageal temperature measurement was also suggested to prevent the development of EF; however, the current data are contradictory (14, 20).

One of the most important patient characteristics with a significant impact on ablation success and safety is age. It has been shown that advanced age is associated with a higher risk of atrial arrhythmia recurrence and a higher incidence of major cardiac adverse events (21, 22). However, the impact of age on the management and outcome of EF is unknown.

This subanalysis of the POTTER-AF study aimed to investigate the impact of patients’ age on the management and outcome of EF following catheter ablation for AF.

Methods

Study design

The POTTER-AF study is an international, multicenter, anonymized, invitation-based registry, which was conducted at the Department of Rhythmology, University Heart Centre Lübeck under the auspices of the Working Group of Cardiac Electrophysiology of the German Cardiac Society (AGEP, DGK). It was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Lübeck, Germany (AZ 21–291), and by the local ethics committees of all participating institutions and was registered at clinicaltrials.gov with the identification number NCT05273645. As this study represents a retrospective analysis of anonymized data, patient consent was not obtained. The study has been conducted in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. Experienced electrophysiological centers were invited worldwide (11).

Data were recorded retrospectively and electronically via a standardized online questionnaire using SurveyMonkey. Patients who had an atrioesophageal fistula, esophageal–pericardial fistula, or esophageal perforation after catheter ablation were included in the POTTER-AF study. There were no exclusion criteria.

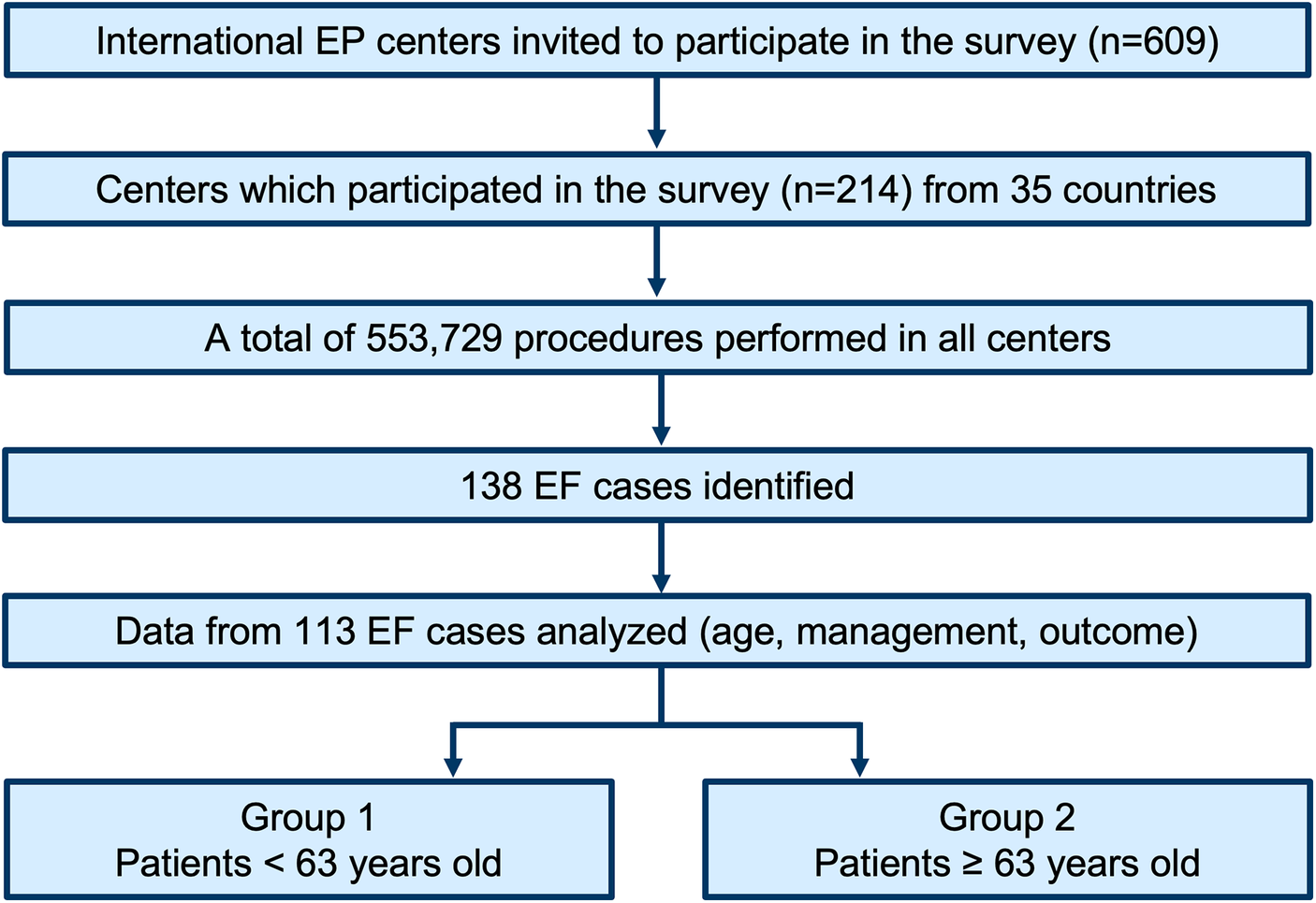

The present work is an age-based subanalysis of the POTTER-AF study, designed to evaluate the influence of age on the management and outcomes of EF following catheter ablation for AF. In addition, the analysis characterizes age-specific differences in baseline and procedural variables. The study population was divided into two cohorts according to the median age: Group 1 comprised patients younger than the median, and Group 2 included those with a median age or older.

Statistical analysis

All categorical variables were reported as absolute and relative frequencies and were compared using Fisher's exact test or the χ2 test, as appropriate. Continuous variables were tested for normal distribution using the Shapiro–Wilk test. They were reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD) in the case of normal distribution, otherwise as median and interquartile range (first quartile, third quartile). Continuous variables were compared using the non-paired Student's t-test when normally distributed and the Mann–Whitney U test otherwise. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 28.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics)

Results

Patient population

A total of 553,729 patients underwent ablation procedures for AF or atrial tachycardia in 214 electrophysiological centers from 35 countries between 1996 and 2022. Of them, 138 (0.025%) patients experienced postprocedural EF, and data regarding the age, management, and prognosis were available in 113 patients. The median age of the population was 63 years. A total of 54 (47.8%) patients experiencing EF were younger than 63 years old (Group 1), and 59 (52.2%) patients were at least 63 years old (Group 2) (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Study flowchart. EF, esophageal fistula; EP, electrophysiological.

The baseline characteristics of the two groups are depicted in Table 1. Almost half of the patients in each group were females (44.4% vs. 48.3%; p = 0.708). No difference was noted between the groups regarding the median body mass index (26.5 vs. 26.3, p = 0.813). Regarding the comorbidities, Group 2 was more likely to suffer from coronary artery disease (25.0% vs. 9.8%; p = 0.046) and hypertension (72.9% vs. 42.6%; p = 0.001). As expected, a CHA2DS2-VASc score lower than 3 was less frequent in the older population (39.0% vs. 82.7%; p < 0.001). There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups regarding the incidence of structural heart disease, congestive heart failure, diabetes, vascular disease, chronic kidney disease, and history of esophageal/gastric disease.

Table 1

| Characteristics | Age < 63 | Age ≥ 63 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female sex, n (%) | 24/54 (44.4%) | 28/58 (48.3%) | 0.708 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 26.5 (24.4, 28.3) | 26.3 (22.7, 29.4) | 0.813 |

| Structural heart disease, n (%) | 12/53 (22.6%) | 22/59 (37.3%) | 0.104 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, % | 60.0 (50.0, 65.0) | 60.0 (52.5, 64.0) | 0.837 |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 5/51 (9.8%) | 14/56 (25.0%) | 0 . 046 |

| Congestive heart failure, n (%) | 7/52 (13.5%) | 11/58 (19.0%) | 0.607 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 23/54 (42.6%) | 43/59 (72.9%) | 0 . 001 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 8/54 (14.8%) | 7/59 (11.9%) | 0.783 |

| Vascular disease, n (%) | 6/41 (14.6%) | 8/45 (17.8%) | 0.775 |

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 3/42 (7.1%) | 7/46 (15.2%) | 0.320 |

| History of esogastric pathology, n (%) | 5/50 (10%) | 3/56 (5.4%) | 0.471 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc score < 3 | 43/52 (82.7%) | 23/59 (39.0%) | <0 . 001 |

| PPI before ablation, n (%) | 14/51 (27.5%) | 9/55 (16.4%) | 0.238 |

| Paroxysmal AF, n (%) | 23/54 (42.6%) | 25/59 (42.4%) | 1 |

| Previous AF/atrial tachycardia ablation, n (%) | 5/54 (9.3%) | 5/59 (8.5%) | 1 |

Baseline characteristics.

Values are counts, n (%), or median and interquartile range (Q1, Q3) as appropriate. PPI, proton pump inhibitors; AF, atrial fibrillation.

Bold indicates statistically significant values.

Symptom onset and diagnosis

The median time to symptom onset was 21.0 (10.0, 25.3) days in Group 1 and 15.0 (6.0, 21.0) days in Group 2 (p = 0.031), while the median time to EF diagnosis was 23.0 (14.5, 32.0) days and 19.0 (14.3, 29.0), respectively (p = 0.240; Figure 2). There was no significant difference between the groups regarding the initial symptoms, as well as regarding the further complications developed (Table 2).

Figure 2

Time to symptom onset in the two age groups.

Table 2

| Characteristics | Age < 63 | Age ≥ 63 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial symptoms | |||

| Duration until initial symptoms, days | 21.0 (10.0, 25.3) | 15.0 (6.0, 21.0) | 0 . 031 |

| Duration until EF diagnosis, days | 23.0 (14.5, 32.0) | 19.0 (14.3, 29.0) | 0.240 |

| Duration from initial symptoms until EF diagnosis, days | 2.0 (1.0, 6.0) | 4.0 (0.5, 10.5) | 0.411 |

| Duration from procedure until hospital admission, days | 21.0 (12.0, 26.8) | 18.5 (12.3, 27.0) | 0.763 |

| Fever, n (%) | 33/54 (61.1%) | 34/59 (57.6%) | 0.848 |

| Chest pain/odynophagia, n (%) | 29/54 (53.7%) | 31/59 (52.5%) | 1 |

| Neurological signs, n (%) | 26/54 (48.1%) | 25/59 (42.4%) | 0.574 |

| Other symptoms, n (%) | 30/54 (55.6%) | 44/59 (74.6%) | 0.047 |

| Further complications | |||

| Stroke, n (%) | 10/48 (20.8%) | 14/54 (25.9%) | 0.642 |

| Septic shock, n (%) | 26/48 (54.2%) | 32/54 (59.3%) | 0.690 |

| Coma, n (%) | 22/48 (45.8%) | 25/54 (46.3%) | 1 |

| Cardiac arrest, n (%) | 9/48 (18.8%) | 11/54 (20.4%) | 1 |

| Tamponade, n (%) | 6/48 (12.5%) | 4/54 (7.4%) | 0.510 |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding, n (%) | 10/48 (20.8%) | 8/54 (14.8%) | 0.448 |

| Other complications, n (%) | 14/48 (29.2%) | 16/54 (29.6%) | 1 |

Initial symptoms and further complications.

Values are counts, n (%), or median and interquartile range (Q1, Q3) as appropriate. EF, esophageal fistula.

Bold indicates statistically significant values.

When analyzing the diagnostic methods, Group 2 was less likely to undergo a brain computed tomography (CT) or brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (25.9% vs. 45.3%; p = 0.046). There was no statistically significant difference between the use of chest CT, endoscopy, or echocardiography (Table 3).

Table 3

| Characteristics | Age < 63 | Age ≥ 63 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic method | |||

| Chest CT, n (%) | 43/53 (81.1%) | 46/58 (79.3%) | 1 |

| Endoscopy, n (%) | 11/53 (20.8%) | 13/58 (22.4%) | 1 |

| Echocardiography, n (%) | 12/53 (22.6%) | 16/58 (27.6%) | 0.663 |

| Brain CT or brain MRI, n (%) | 24/53 (45.3%) | 15/58 (25.9%) | 0.046 |

| Others, n (%) | 12/53 (22.6%) | 7/58 (12.1%) | 0.207 |

| Type of esophageal fistula | |||

| Atrioesophageal fistula | 52/54 (96.3%) | 56/59 (94.9%) | 1 |

| Esophageal perforation | 0/54 (0.0%) | 1/59 (1.7%) | 1 |

| Esophageal–pericardial fistula | 2/54 (3.7%) | 2/59 (3.4%) | 1 |

Diagnosis methods and type of esophageal fistula.

Values are counts, n (%). CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Bold indicates statistically significant values.

No difference was noted between the groups regarding the proportions of atrioesophageal fistula, esophageal perforation, and esophageal–pericardial fistula (Table 3).

Procedural characteristics

The two populations were similar in terms of sedation type, energy source, and ablation techniques used, as well as in terms of esophageal temperature probe utilization (Table 4). General anesthesia was used in 44.4% of patients in Group 1 vs. 49.2% of patients in Group 2 (p = 0.707). Most of the patients underwent a radiofrequency-based catheter ablation (94.4% in Group 1 vs. 98.3% in Group 2; p = 0.347). An esophageal temperature probe was used in 24.1% of patients in Group 1 and in 25.4% of patients in Group 2 (p = 1).

Table 4

| Characteristics | Age < 63 | Age ≥ 63 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conscious sedation, n (%) | 11/54 (20.4%) | 6/59 (10.2%) | 0.188 |

| Deep analgosedation, n (%) | 15/54 (27.8%) | 19/59 (32.2%) | 0.683 |

| General anesthesia, n (%) | 24/54 (44.4%) | 29/59 (49.2%) | 0.707 |

| Use of thermal probe, n (%) | 13/54 (24.1%) | 15/59 (25.4%) | 1 |

| Procedure duration, minutes | 141.5 (105.0, 183.0) | 148.5 (112.5, 180.0) | 0.895 |

| Radiofrequency, n (%) | 51/54 (94.4%) | 58/59 (98.3%) | 0.347 |

| Cryoballoon, n (%) | 2/54 (3.7%) | 1/59 (1.7%) | 0.605 |

| Laser balloon, n (%) | 1/54 (1.9%) | 0/59 (0.0%) | 0.478 |

| RF duration, minutes | 38.5 (25.3, 59.1) | 38.0 (21.0, 48.0) | 0.346 |

| PVI circumferential, n (%) | 48/49 (98.0%) | 50/55 (90.9%) | 0.210 |

| PVI segmental ostial, n (%) | 1/49 (2.0%) | 0/55 (0.0%) | 0.471 |

| PVI anatomical, n (%) | 1/49 (2.0%) | 5/55 (9.1%) | 0.210 |

| PPI postprocedural, n (%) | 39/50 (78.0%) | 42/59 (71.2%) | 0.511 |

Procedural characteristics.

Values are counts, n (%), or median and interquartile range (Q1, Q3) as appropriate. RF, radiofrequency; PVI, pulmonary vein isolation; PPI, proton pump inhibitors.

Management and outcome

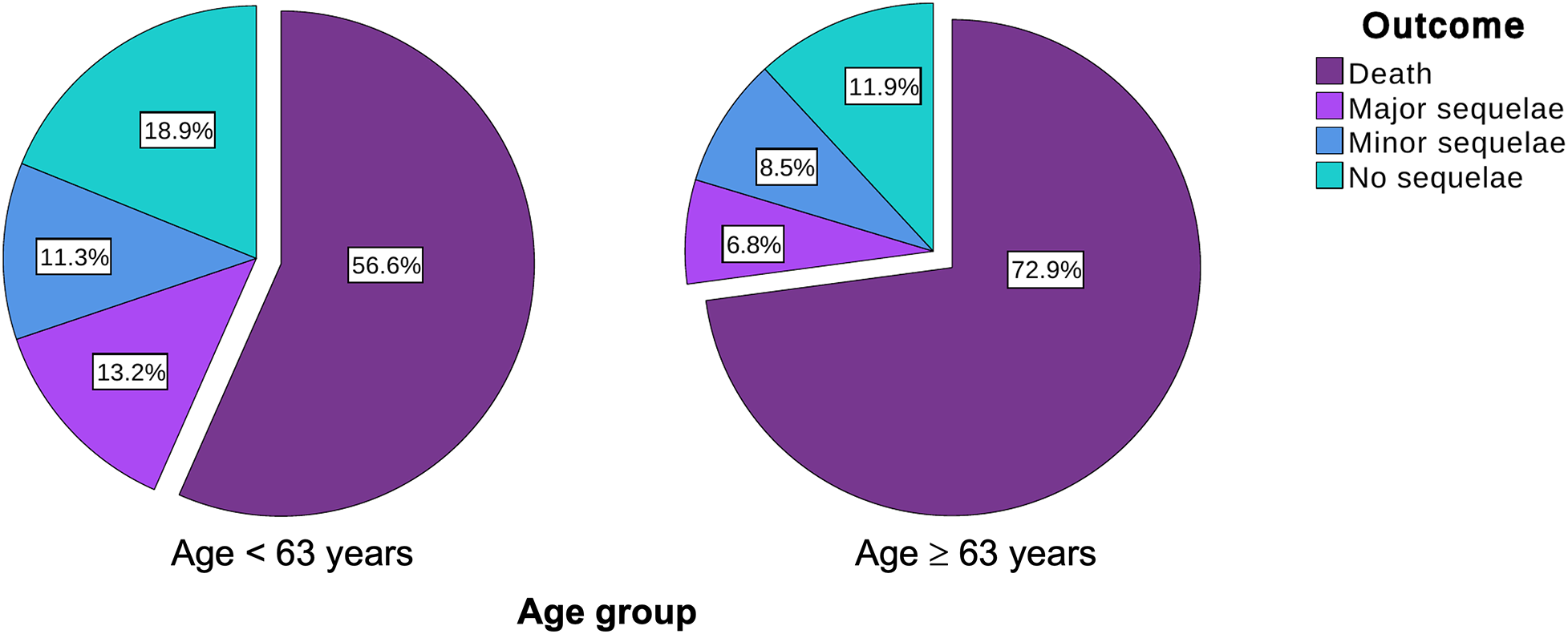

The older population was more likely to undergo a direct endoscopic treatment without surgery (27.6% vs. 11.3%; p = 0.035), while there was no difference regarding the rate of surgical treatment. The conservative treatment was used in similar proportions (37.7% in Group 1 vs. 29.3% in Group 2; p = 0.421) (Table 5 and Figure 3). A clear trend toward a higher fatality was noted in the older population (72.9% vs. 56.6%; p = 0.078). The incidence of major and minor sequelae was similar for both groups (Table 5 and Figure 4).

Table 5

| Characteristics | Age < 63 | Age ≥ 63 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Esophageal surgery, n (%) | 27/53 (50.9%) | 25/58 (43.1%) | 0.450 |

|

22/53 (41.5%) | 23/58 (39.7%) | 0.849 |

| Endoscopic treatment, n (%) | 11/53 (20.8%) | 18/58 (31.0%) | 0.281 |

|

6/53 (11.3%) | 16/58 (27.6%) | 0.035 |

| Conservative treatment, n (%) | 20/53 (37.7%) | 17/58 (29.3%) | 0.421 |

Management.

Values are counts, n (%). Under “endoscopic treatment” are reported all patients who underwent any endoscopic intervention, irrespective of whether they also received surgical treatment. Under “esophageal surgery” are reported all patients who underwent any surgical intervention, regardless of concurrent endoscopic treatment. The subcategories listed with bullet points indicate the number of patients in each group who received exclusively endoscopic or exclusively surgical treatment.

Figure 3

Type of treatment for each age group.

Figure 4

Outcome for each age group.

The fatality of EF was significantly higher in patients managed conservatively compared with that of patients treated invasively (endoscopically and/or surgically) in both Group 1 (80.0% vs. 40.6%, p = 0.009) and Group 2 (100.0% vs. 61.0%, p = 0.003).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to date to evaluate the impact of age on EF management and prognosis following catheter ablation for AF or AT. The main findings of the study are as follows:

The time to symptom onset was significantly shorter in the older population.

Brain CT or MRI was less commonly used among older patients.

Direct endoscopic treatment was used more often in the older population.

Conservative therapy was used in similar proportions of patients.

The older patients showed a trend toward a higher fatality.

Age is the main risk factor for developing AF and for its progression from paroxysmal to persistent type (

1). In some studies, age is shown to predict the postprocedural complication rates after AF ablation; however, the current data are contradictory (

21–

28).

Regarding EF following catheter ablation for AF, it has been shown that the treatment, either endoscopic or surgical, can improve the outcome in these patients (11, 14, 29, 30). For this reason, the early diagnosis and initiation of therapy are crucial to reduce mortality. An important limitation in this case is the relatively late onset of symptoms following AF ablation, which can lead to a delayed diagnosis (11, 14, 29, 30). As demonstrated in the POTTER-AF study, the patients with an early EF detection received an early treatment via endoscopy or esophageal surgery and showed a lower fatality as compared with those with late detection, who more often received a conservative treatment (11). The present study demonstrated a shorter time to symptom onset in the elderly population, which might be at least partially explained by the frailer status of these patients. However, this difference did not translate into a lower fatality in this group, probably due to the impact of age itself on the prognosis.

When a clinical suspicion for EF occurs, the most frequently used modality for diagnosis is chest CT (11, 22, 29, 30). Transthoracic echocardiography is not sensitive enough, and transesophageal echocardiography should be avoided, as it may worsen the situation (30, 31). Esophagogastroscopy or nasogastric tube insertion might also be detrimental, as it can open the tissue flap and increase the blood flow through the fistula and aggravate systemic air embolism (32). In the present study, the most common diagnostic method was the chest CT, with similar rates in both groups. However, in the elderly population, the rate of brain CT and brain MRI was lower compared with the younger population, although the incidence of neurological symptoms was similar between the groups.

In the present study, direct endoscopic treatment without surgery was significantly more often used in the elderly group, while the surgical treatment was slightly more common in the younger population, without reaching the statistical significance level. This observation might however be biased by the clinical status of the patients, which is expected to be more deteriorated in the older group, leading to a lower rate of surgical interventions. As previously discussed, the use of a conservative approach was associated with a higher fatality as compared with endoscopic or surgical approaches (11, 12, 29, 30). In this study, the use of a conservative approach was slightly more common in the younger population, without reaching statistical significance. Given the retrospective nature of this study, the criteria guiding treatment decisions cannot be derived from our dataset. Nevertheless, several hypotheses may help explain this counterintuitive observation. One possibility is that younger patients appeared clinically more stable at presentation, prompting clinicians to opt for a conservative strategy. However, considering the high lethality of this condition, such an approach may be misleading, as conservatively managed patients generally exhibit poorer outcomes. Another contributing factor could be a longer time from symptom onset to diagnosis observed in younger individuals, potentially influencing clinical decision-making. A further explanation may relate to the perceived greater physiological reserve in younger patients, leading to the expectation that they might recover without aggressive intervention.

A trend toward higher fatality (i.e., the proportion of patients who died from EF among those who developed it) was observed in the older population. This finding should be taken into account when discussing the risks and benefits of catheter ablation for AF in this age group.

Regardless of age, it is important to emphasize that conservative management is associated with a worse prognosis, and an interventional or surgical approach should be pursued whenever feasible (11, 14).

Limitations

This is a subanalysis of a retrospective, invitation-based, international registry and comes with several specific limitations. First, the incidence of EF in the two age-based groups could not be determined due to the study design. Of note, the prevalence of mediastinal changes diagnosed by endosonography was not age dependent, so we cannot exclude that the observed age differences represent an accidental observation (33). Second, only data from patients exhibiting EF were collected, so the assessment of predictors of EF occurrence was not possible. Third, the decision regarding the management, as well as the outcome, could have been biased due to comorbidities, critical illness, and operability of the patients. Data on preoperative physical health status, such as the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score, which could have provided valuable insights into the decision-making process, were not available for this analysis. Fourth, due to the retrospective character of the registry, not all data were available for the whole population. Fifth, given the method of data acquisition via an invited survey, underreporting of these complications and the loss of detailed individual patient information cannot be excluded.

Conclusions

This is the first study to date to report on the impact of age on the management and outcome of EF following catheter ablation for AF. Older patients had initial symptoms earlier, and brain CT or brain MRI was used less commonly as a diagnostic modality in this population. Older patients who developed EF after catheter ablation were more frequently treated with direct endoscopic interventions and showed a trend toward higher fatality.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because data supporting the POTTER-AF study are curated at the Clinical Trial Unit of the Department of Rhythmology, University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein, Germany. These data are not shared openly but are available on reasonable request from the corresponding authors. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to RT, tilz6@hotmail.com.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Lübeck AZ 21–291. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants' legal guardians/next of kin because this is a registry study. All data were collected retrospectively and anonymized. No intervention was conducted as part of the study.

Author contributions

SP: Writing – original draft, Validation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. ZD: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. VS: Project administration, Data curation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. HPü: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. PS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CSo: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CV: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KC: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. PM: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. EG: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. ML: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. SW: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. TB: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. LI: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. AF: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. RS: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. SR: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AS: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. MaK: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CW: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. D-IS: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. DG: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. MB: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DR: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. UW: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AB: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. AMe: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LE: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. OK: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. CSt: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. MiK: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. DN: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LR: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DL: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. PV: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. BM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JVi: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AA: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. CG: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LF: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. SB: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. YG: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AC: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. PJ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AMi: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. LJ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RG: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HPo: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. ZK: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JL: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AlM: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. FB: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AZ: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. YS: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. OP: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. NA: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CM: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. JC: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. BA: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. GL: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. EÖ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HY: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. SC: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KY: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. MS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. EJ-P: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. OI: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. KO: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KE: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. HK: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JNC: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. VR: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. AN: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HB: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. BY: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. JVo: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. K-HK: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. JM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AK: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. C-HH: Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. RT: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Validation, Investigation, Supervision, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Project administration, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to all participating centers and investigators for their valuable contributions to this survey.

Conflict of interest

RT is a consultant for Boston Scientific, Philips, Medtronic Biosense Webster, and Abbott Medical; is a shareholder and medical director at Active Health; received speaker honoraria from Boston Scientific, Biotronik, Biosense Webster, Abbott Medical, Lifetech, and Pfizer; received research grants from Abbott, Biotronik, Medtronic, Biosense Webster, and Lifetech; and received travel grants from Abbott, Biosense Webster, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and Philips. SP is a medical consultant at Active Health and received travel grants and congress grants from Lifetech and educational grants and speaker grants from Abbott Medical. K-HK reports grants and personal fees from Abbott Vascular, Medtronic, and Biosense Webster, outside the submitted work. C-HH received travel and research grants from Boston Scientific, Lifetech, Biosense Webster, and CardioFocus and speaker honoraria from Medtronic, Boston Scientific, Biosense Webster, CardioFocus, C.T.I. GmbH, and Doctrina Med. He is also a consultant for Boston Scientific, Lifetech, Biosense Webster, and CardioFocus. JVo received speaker honoraria from Abbott, Boston Scientific, Impulse Dynamics, Pfizer, and Doctrina Med. HPü received honoraria or consultation fees from Bayer, Daiichi Sankyo, Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, Abbott, Biosense Webster, Boston Scientific, and Medtronic and has participated in a company-sponsored speaker's bureau for Biosense Webster, Abbott, Medtronic, and Boston Scientific. MM is a consultant and speaker for Abbott Medical, Biosense Webster, Medtronic, and Boston Scientific. PS: advisory board for Biosense Webster, Boston Scientific, Abbott, and Medtronic. CSo received research support and lecture fees from Medtronic, Abbott, Boston Scientific, and Biosense Webster. In addition, CSo is a consultant for Medtronic, Boston Scientific, and Biosense Webster. CV received consulting honoraria from Biotronik and Medtronic and training and speaker's honoraria from Medtronic, Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), and Zoll. SW received consulting fees from Abbott, Biosense Webster, Boston Scientific, Bristol Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Medtronic, and Daiichi Sankyo and grants from Abbott and Boston Scientific. LI received consultant honoraria and/or lecture honoraria and/or and travel grants from Abbott Medical, Bayer, Berlin-Chemie, Biosense Webster, Biotronik, Bristol Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, Medtronic, and Novartis. SR is a consultant for Medtronic, Abbott, and Biotronik and member of the Medtronic European Conduction System Pacing Advisory Board. MK received honoraria for teaching, proctoring, lectures, advisory board activities, and participation in clinical trials and travel grants. CW received lecture fees from Biosense Webster. UW received lecture fees from Abbott Medical and Medtronic Inc. AMe received consultant fees from Medtronic, CardioFocus, Biosense Webster, and Boston Scientific and travel grants and lecture honoraria from Medtronic, CardioFocus, Biosense Webster, Boston Scientific, Lifetech, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer, and Philips EPD. LE discloses consultant fees, speaking honoraria, and travel expenses from Abbott, Bayer Healthcare, Biosense Webster, Biotronik, Boehringer, Boston Scientific, Bristol Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, Medtronic, Pfizer, and Sanofi Aventis. Research support has been provided by the German Research Foundation (DFG) and German Heart Foundation outside the submitted work. CSt reports grants and lecture fees from Biosense Webster and Medtronic and served as a proctor for Biosense Webster and Medtronic. He also reports grants from the Swiss Heart Foundation, the Foundation for Cardiovascular Research Basel, and the University of Basel. LR received research grants from Medtronic, the Swiss National Foundation, the Swiss Heart Foundation, the Immanuel and Ilse Straub Foundation, and the Sitem-Insel Support Fund, all outside the submitted study. He received speaker fees/honoraria from Biosense Webster, Boston Scientific, Abbott, and Medtronic. CG: research grants from MicroPort CRM; consultant, MicroPort CRM, Boston Scientific, Abbott, and Medtronic; honoraria, Biotronik, Medtronic, AstraZeneca, BMS/Pfizer, and Biosense Webster. LF reports consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, BMS/Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Medtronic, Novo Nordisk, and Novartis and lecture fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, BMS/Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Zoll. SB is a consultant for Medtronic, Boston Scientific, MicroPort, and Zoll. PJ received grant from Biosense Webster, Medtronic, Abbott, and Boston Scientific. CM has received speaker honoraria and consultancy fees from Boston Scientific, Medtronic, Biosense Webster, and Adagio. JC serves as a consultant for Biosense Webster and Johnson & Johnson. GL received speaker honoraria from Biosense Webster, Medtronic, and Abbott. EÖ reports payment from the healthcare industry to his institution for personal services, including honoraria, consultancy, and advisory board from Biosense Webster and Medtronic. HY is a proctor for Abbott, Medtronic, and Biosense Webster. SC received travel grants and speaker's honoraria from Medtronic, Biosense Webster, and Abbott and is a proctor of Medtronic and Biotronik. EJ-P received consultant fees from Biotronik, Medtronic, Abbott, and Boston Scientific. KO received remuneration from Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, Johnson & Johnson, and Medtronic. JC reports research support from Circa Scientific. VR reports no disclosures directly related to this manuscript. Unrelated to this work, he has served as a consultant for and has equity in multiple healthcare companies: Anumana, APN Health, Append Medical, AquaHeart, AtaCor, Atraverse, Autonomix, BioSig, CardiaCare, CardioFocus, CardioNXT/AFTx, Circa Scientific, CoRISMA, Cortex-Boston Scientific, Corvia Medical, Dinova-Hangzhou DiNovA EP Technology, East End Medical, EP Frontiers, Field Medical, Focused Therapeutics, HeartBeam, HRT, InterShunt, Javelin, Kardium, Laminar-J&J MedTech, LuxMed, MedLumics, Orchestra Biomed, PhysioMaps, Pulse Biosciences, Restore Medical, Sirona Medical, SoundCath-Boston Scientific, and Volta Medical. Unrelated to this work, he has served as a consultant for Abbott, Adagio Medical, AtriAN, BioTel Heart, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, Cairdac, Cardionomic, Conformal Medical, CoreMap, FIRE1, Impulse Dynamics, J&J MedTech, Medtronic, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, and Philips. Unrelated to this work, he has equity in DRS Vascular, Manual Surgical Sciences, NewPace, Nyra Medical, SoundCath, SureCor, and VizaraMed. AN is a consultant for Abbott, Baylis, Biosense Webster, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, and Medtronic. DS: research grants, Abbott, Medtronic, and Johnson & Johnson; advisory board, Pfizer and Abbott; speaker fee, Abbott, Medtronic, and Johnson & Johnson. JM received speaker fees and/or honoraria for lectures and scientific advice from Biotronik, Medtronic, MicroPort, Milestone Pharmaceutical, Sanofi, and Zoll.

The remaining author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. During the preparation of this work, the authors used ChatGPT—OpenAI to improve the language and readability of the manuscript. After using this tool/service, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence, and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

AF, atrial fibrillation; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; CT, computed tomography; EF, esophageal fistula; EP, electrophysiological; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PPI, proton pump inhibitors; PVI, pulmonary vein isolation; SD, standard deviation.

References

1.

Kornej J Börschel CS Benjamin EJ Schnabel RB . Epidemiology of atrial fibrillation in the 21st century. Circ Res. (2020) 127(1):4–20. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.316340

2.

Van Gelder IC Rienstra M Bunting KV Casado-Arroyo R Caso V Crijns HJGM et al 2024 ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J. (2024) 45(36):3314–414. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehae176

3.

Tzeis S Gerstenfeld EP Kalman J Saad EB Sepehri Shamloo A Andrade JG et al 2024 European Heart Rhythm Association/Heart Rhythm Society/Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society/Latin American Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus statement on catheter and surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation. Europace. (2024) 26(4):euae043. 10.1093/europace/euae043

4.

Heeger CH Sano M Popescu SS Subin B Feher M Phan H-L et al Very high-power short-duration ablation for pulmonary vein isolation utilizing a very-close protocol—the FAST AND FURIOUS PVI study. EP Europace. (2023) 25(3):880–8. 10.1093/europace/euac243

5.

Heeger CH Popescu SS Inderhees T Nussbickel N Eitel C Kirstein B et al Novel or established cryoballoon ablation system for pulmonary vein isolation: the prospective ICE-AGE-1 study. Europace. (2023) 25(9):euad248. 10.1093/europace/euad248

6.

Heeger C Bohnen J Popescu S Meyer-Saraei R Fink T Sciacca V et al Experience and procedural efficacy of pulmonary vein isolation using the fourth and second generation cryoballoon: the shorter, the better? J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. (2021) 32(6):1553–60. 10.1111/jce.15009

7.

Heeger CH Popescu SS Saraei R Kirstein B Hatahet S Samara O et al Individualized or fixed approach to pulmonary vein isolation utilizing the fourth-generation cryoballoon in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: the randomized INDI-FREEZE trial. EP Europace. (2021) 24(6):921–7. 10.1093/europace/euab305.

8.

Kuck KH Brugada J Fürnkranz A Metzner A Ouyang F Chun KRJ et al Cryoballoon or radiofrequency ablation for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. (2016) 374(23):2235–45. 10.1056/NEJMoa1602014

9.

Heeger CH Sohns C Pott A Metzner A Inaba O Straube F et al Phrenic nerve injury during cryoballoon-based pulmonary vein isolation: results of the worldwide YETI registry. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. (2022) 15(1):e010516. 10.1161/CIRCEP.121.010516

10.

Heeger CH Ștefan PS Sohns C Pott A Metzner A Inaba O et al Impact of cryoballoon application abortion due to phrenic nerve injury on reconnection rates: a YETI subgroup analysis. EP Europace. (2023) 25(2):374–81. 10.1093/europace/euac212

11.

Tilz RR Schmidt V Pürerfellner H Maury P Chun KRJ Martinek M et al A worldwide survey on incidence, management and prognosis of oesophageal fistula formation following atrial fibrillation catheter ablation: the POTTER-AF study. Eur Heart J. (2023) 44:2458–69. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad250

12.

Tilz RR Pürerfellner H Kuck KH Merino JL Schmidt V Vogler J et al Underreporting of complications following AF ablation: comparison of the manufacturer and user facility device experience FDA database and a voluntary invitation-based registry: the POTTER-AF 3 study. Heart Rhythm. (2025) 22(6):1472–9. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2024.09.060

13.

Fender EA Widmer RJ Hodge DO Cooper GM Monahan KH Peterson LA et al Severe pulmonary vein stenosis resulting from ablation for atrial fibrillation. Circulation. (2016) 134(23):1812–21. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.021949

14.

Tilz RR Popescu SS Pürerfellner H Kuck KH Xiang K Uzunoglu EC et al Impact of ablation energy on mortality after oesophageal fistula and injury complicating atrial fibrillation ablation procedures: results from a worldwide FDA database, the POTTER-AF 2 study. Eur Heart J Open. (2025) 5(6):oeaf146. 10.1093/ehjopen/oeaf146

15.

Della Rocca DG Magnocavallo M Natale VN Gianni C Mohanty S Trivedi C et al Clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment of atrioesophageal fistula resulting from atrial fibrillation ablation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. (2021) 32(9):2441–50. 10.1111/jce.15168

16.

Leung LWM Akhtar Z Sheppard MN Louis-Auguste J Hayat J Gallagher MM . Preventing esophageal complications from atrial fibrillation ablation: a review. Heart Rhythm O2. (2021) 2(6):651–64. 10.1016/j.hroo.2021.09.004

17.

Ishidoya Y Kwan E Dosdall DJ Macleod RS Navaravong L Steinberg BA et al Short-term natural course of esophageal thermal injury after ablation for atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. (2022) 33(7):1450–9. 10.1111/jce.15553

18.

Bodziock G Norton C Montgomery J . Prevention and treatment of atrioesophageal fistula related to catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation. J Innov Card Rhythm Manag. (2019) 0(5):3634–40. 10.19102/icrm.2019.100505

19.

Zellerhoff S Lenze F Eckardt L . Prophylactic proton pump inhibition after atrial fibrillation ablation: is there any evidence?Europace. (2011) 13(9):1219–21. 10.1093/europace/eur139

20.

Schoene K Arya A Grashoff F Knopp H Weber A Lerche M et al Oesophageal probe evaluation in radiofrequency ablation of atrial fibrillation (OPERA): results from a prospective randomized trial. EP Europace. (2020) 22(10):1487–94. 10.1093/europace/euaa209

21.

Bunch TJ May HT Bair TL Jacobs V Crandall BG Cutler M et al The impact of age on 5-year outcomes after atrial fibrillation catheter ablation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. (2016) 27(2):141–6. 10.1111/jce.12849

22.

Liu A Lin M Maduray K Han W Zhong J-Q . Clinical manifestations, outcomes, and mortality risk factors of atrial-esophageal fistula: a systematic review. Cardiology. (2022) 147(1):26–34. 10.1159/000519224

23.

Bahnson TD Giczewska A Mark DB Russo AM Monahan KH Al-Khalidi HR et al Association between age and outcomes of catheter ablation versus medical therapy for atrial fibrillation: results from the CABANA trial. Circulation. (2022) 145(11):796–804. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.055297

24.

França MRQ Morillo CA Carmo AAL Mayrink M Miranda RC Naback ADN et al Efficacy and safety of catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation in elderly patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. (2024) 67(7):1691–707. 10.1007/s10840-024-01755-5

25.

Hosseini SM Rozen G Saleh A Vaid J Biton Y Moazzami K et al Catheter ablation for cardiac arrhythmias. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. (2017) 3(11):1240–8. 10.1016/j.jacep.2017.05.005

26.

Numminen A Penttilä T Arola O Inkovaara J Oksala N Mäkynen H et al Treatment success and its predictors as well as the complications of catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation in a high-volume centre. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. (2022) 63(2):357–67. 10.1007/s10840-021-01011-0

27.

Lee WC Wu PJ Chen HC Fang HY Liu PY Chen MC . Efficacy and safety of ablation for symptomatic atrial fibrillation in elderly patients: a meta-analysis. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2021) 8:734204. 10.3389/fcvm.2021.734204

28.

Nielsen J Kragholm KH Christensen SB Johannessen A Torp-Pedersen C Kristiansen SB et al Periprocedural complications and one-year outcomes after catheter ablation for treatment of atrial fibrillation in elderly patients: a nationwide Danish cohort study. J Geriatr Cardiol. (2021) 18(11):897–907. 10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2021.11.005

29.

Gandjbakhch E Mandel F Dagher Y Hidden-Lucet F Rollin A Maury P . Incidence, epidemiology, diagnosis and prognosis of atrio-oesophageal fistula following percutaneous catheter ablation: a French nationwide survey. EP Europace. (2021) 23(4):557–64. 10.1093/europace/euaa278

30.

Han HC Ha FJ Sanders P Spencer R Teh AW O’Donnell D et al Atrioesophageal fistula: clinical presentation, procedural characteristics, diagnostic investigations, and treatment outcomes. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. (2017) 10(11):e005579. 10.1161/CIRCEP.117.005579

31.

O’Kane D Pusalkar A Topping W Spooner O Roantree E . An avoidable cause of cardioembolic stroke. Acute Med J. (2014) 13(3):126–8. 10.52964/AMJA.0361

32.

Kim YG Shim J Lee KN Lim JY Chung JH Jung JS et al Management of atrio-esophageal Fistula induced by radiofrequency catheter ablation in atrial fibrillation patients: a case series. Sci Rep. (2020) 10(1):8202. 10.1038/s41598-020-65185-9

33.

Zellerhoff S Ullerich H Lenze F Meister T Wasmer K Mönnig G et al Damage to the esophagus after atrial fibrillation ablation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. (2010) 3(2):155–9. 10.1161/CIRCEP.109.915918

Summary

Keywords

age, atrial fibrillation, catheter ablation, complication, esophageal fistula

Citation

Popescu SS, Demirtakan ZG, Schmidt V, Pürerfellner H, Sommer P, Sohns C, Veltmann C, Steven D, Chun KRJ, Maury P, Gandjbakhch E, Laredo M, Willems S, Beiert T, Iden L, Füting A, Spittler R, Richter S, Schade A, Kuniss M, Wunderlich C, Shin D-I, Grosse Meininghaus D, Bonsels M, Reek D, Wiegand U, Bauer A, Metzner A, Eckardt L, Krahnefeld O, Sticherling C, Kühne M, Nguyen DQ, Roten L, Linz D, van der Voort P, Mulder BA, Vijgen J, Almorad A, Guenancia C, Fauchier L, Boveda S, De Greef Y, Da Costa A, Jais P, Milhem A, Jesel L, Garcia R, Poty H, Khoueiry Z, Seitz J, Laborderie J, Mechulan A, Brigadeau F, Zhao A, Saludas Y, Piot O, Ahluwalia N, Martin C, Chen J, Antolic B, Leventopoulos G, Özcan EE, Yorgun H, Cay S, Yalin K, Sobhy Botros M, Jędrzejczyk-Patej E, Inaba O, Okumura K, Ejima K, Khakpour H, Catanzaro JN, Reddy V, Natale A, Blessberger H, Yang B, Vogler J, Kuck K-H, Merino JL, Keelani A, Heeger C-H and Tilz RR (2026) Impact of age on the management and prognosis of esophageal fistula after atrial fibrillation ablation—a subanalysis of the worldwide POTTER-AF study. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 12:1708499. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1708499

Received

18 September 2025

Revised

30 November 2025

Accepted

26 December 2025

Published

11 February 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Rui Providencia, University College London, United Kingdom

Reviewed by

Philipp Halbfass, Klinikum Oldenburg, Germany

Laura Filaire, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire (CHU) de Saint-Étienne, France

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Popescu, Demirtakan, Schmidt, Pürerfellner, Sommer, Sohns, Veltmann, Steven, Chun, Maury, Gandjbakhch, Laredo, Willems, Beiert, Iden, Füting, Spittler, Richter, Schade, Kuniss, Wunderlich, Shin, Grosse Meininghaus, Bonsels, Reek, Wiegand, Bauer, Metzner, Eckardt, Krahnefeld, Sticherling, Kühne, Nguyen, Roten, Linz, van der Voort, Mulder, Vijgen, Almorad, Guenancia, Fauchier, Boveda, De Greef, Da Costa, Jais, Milhem, Jesel, Garcia, Poty, Khoueiry, Seitz, Laborderie, Mechulan, Brigadeau, Zhao, Saludas, Piot, Ahluwalia, Martin, Chen, Antolic, Leventopoulos, Özcan, Yorgun, Cay, Yalin, Sobhy Botros, Jędrzejczyk-Patej, Inaba, Okumura, Ejima, Khakpour, Catanzaro, Reddy, Natale, Blessberger, Yang, Vogler, Kuck, Merino, Keelani, Heeger and Tilz.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Roland Richard Tilz tilz6@hotmail.com Sorin S. Popescu sorin.popescu29@yahoo.ro

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

‡ Present Addresses: Ahmad Keelani, Department of Rhythmology, Bad Berka Central Clinic, GermanyChristian-H. Heeger, Department of Rhythmology, Asklepios Hospital Altona, Hamburg, Germany

ORCID Sorin S. Popescu orcid.org/0000-0002-5469-8833 Helmut Pürerfellner orcid.org/0000-0002-8965-8495 Christian Veltmann orcid.org/0000-0001-7587-1124 Christian Sticherling orcid.org/0000-0001-8428-7050 Rodrigue Garcia orcid.org/0000-0001-9350-2437 Christian-H. Heeger orcid.org/0000-0002-9014-8097 Roland Richard Tilz orcid.org/0000-0002-0122-7130

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.