Abstract

Background:

During transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) procedures, traditional wire pacing demonstrates safety and efficacy profiles similar to, or even superior to, right ventricular pacing. However, it still has disadvantages such as high thresholds and impedance and unstable pacing in some patients.

Methods:

Our center pioneered the following J-wire pacing technique: inserting a J-wire through the auxiliary access 8F sheath (for balloon-expandable valves) or the main access 20F sheath (for self-expanding valves) into the descending aorta and aligning it at the same height as the left ventricular wire creates a loop circuit between the J-wire and the left ventricular wire after the balloon or prosthesis has been inserted into the annulus. This study included a total of 26 patients. The impedance and threshold of traditional wire pacing and J-wire pacing were measured, and the pacing method with the lower threshold was selected as the intraoperative pacing method.

Results:

All 26 patients were assigned to the J-wire pacing group, achieving a 100% surgical success rate. The proportion of patients with a pacing threshold ≤5 V was significantly higher compared to traditional wire pacing (76.92% vs. 0%), while the proportion with a threshold ≥10 V was significantly lower (0% vs. 38.46%).

Conclusions:

J-wire pacing offers improved safety and effectiveness compared to traditional wire pacing in TAVR procedures. We herein share this single-center experience, hoping to provide novel insights for the refinement of TAVR procedures.

Introduction

With the advancement of transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) techniques, the minimally invasive TAVR approach has been increasingly adopted by medical centers. Wire pacing is a crucial component of minimalist TAVR. It not only shortens procedure time, reduces fluoroscopy time, and lowers patient costs but also avoids the risk of pericardial tamponade associated with right ventricular (RV) pacing. Currently, there are three traditional wire pacing modalities. In all, the cathode is connected to the left ventricular (LV) wire via an alligator clip. The anode can be either (1) clipped to the skin incision of the femoral artery sheath, (2) clipped to a 5 mL syringe needle inserted through the skin at the groin, or (3) connected to a grounding pad adhered to the chest wall over the left ventricular apex. Extensive research has confirmed that traditional wire pacing techniques offer safety and efficacy comparable to RV pacing (1, 2). Recently, Yildirim et al. demonstrated that traditional wire pacing may be superior to RV pacing in terms of both safety and effectiveness (3). However, in clinical practice, we have observed that traditional wire pacing is associated with relatively high impedance and thresholds and, in some patients, it was unstable. Given that the maximum output voltage of temporary pacemakers is 20 V, some patients who undergo the aforementioned pacing methods cannot achieve pacing at voltages greater than twice their threshold, as required by clinical protocols (2), due to excessively high thresholds. This may lead to loss of capture during the procedure, potentially resulting in unacceptable complications such as displacement of the valve or balloon or damage to the valve leaflets.

Methods

The inclusion criteria were based on the 2023 Chinese Clinical Practice Guideline for TAVR. The exclusion criteria included the following: (1) presence of pre-existing right bundle branch block, bifascicular block, or type II second-degree atrioventricular block; or (2) patients with pre-existing high-grade atrioventricular block or third-degree atrioventricular block who had not received a permanent pacemaker.

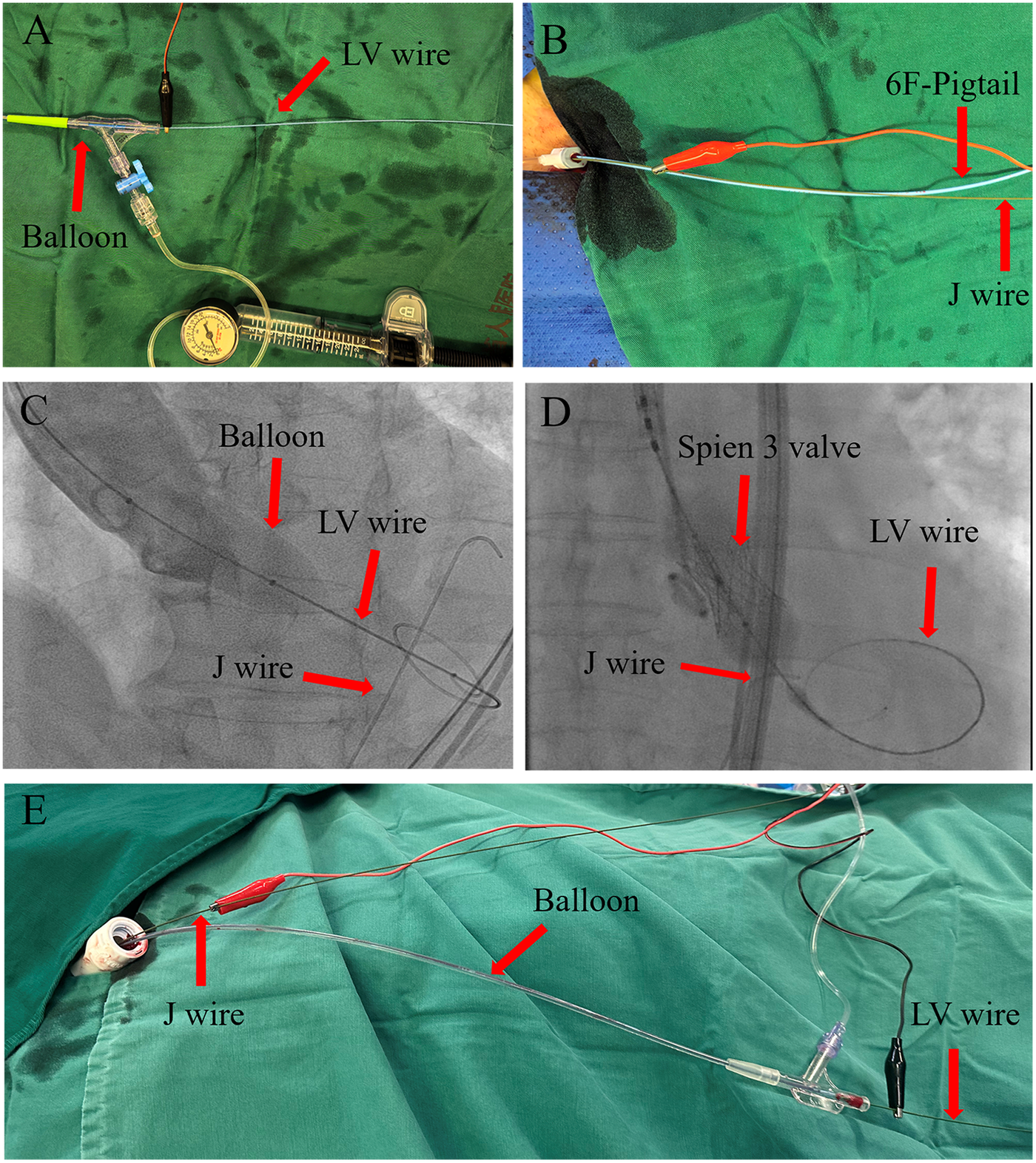

Our center discovered that inserting a J-wire through the auxiliary access 8F sheath (for balloon-expandable valves; Figures 1A,B) or the main access 20F sheath (for self-expanding valves; Figure 1E) into the descending aorta and aligning it at the same height as the left ventricular wire (Figures 1C,D) creates a loop circuit between the J-wire and the LV wire (4) after the balloon or prosthesis has been inserted into the annulus. Pacing through this loop circuit significantly reduces the impedance and threshold of wire pacing, thereby expanding its applicability and enhancing its effectiveness and safety. We hereby share our experiences of this technique at this center. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hainan Provincial People's Hospital (Approval No. EC-JS-2024-134-01) and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Figure 1

J-wire pacing procedure. (A–D) J-wire pacing in a balloon-expandable valve. After the balloon or prosthetic valve is advanced over the left ventricular (LV) wire to the aortic sinus, the J-wire is inserted through the auxiliary access 8F sheath and advanced to the descending aorta, with its tip aligned with the LV wire. The red alligator clip (anode) is connected to the J-wire and the black alligator clip (cathode) to the LV wire. (E) J-wire pacing in a self-expandable valve. After the balloon or prosthetic valve is advanced over the LV wire to the aortic sinus, the J-wire is inserted through the 20F sheath and advanced to the descending aorta, with its tip aligned with the LV wire. The red alligator clip (anode) is connected to the J-wire and the black alligator clip (cathode) to the LV wire.

We pre-tested the threshold and impedance of the three traditional wire pacing methods and the J-wire pacing method. The pacing method with the lowest impedance and threshold was selected for intraoperative pacing; no randomization was performed, as the optimal method was chosen directly.

For the selected pacing method:

If the threshold was ≤5 V, a pacing voltage of 10 V was used during balloon dilation and valve deployment.

If the threshold was >5 V, a voltage twice the threshold value was used for pacing.

If the threshold was >10 V, right ventricular pacing was employed instead.

The primary endpoints were the safety and efficacy of the pacing. Efficacy was defined as stable and effective capture by the selected pacing method during balloon dilation and/or valve deployment, achieving a systolic blood pressure ≤60 mmHg with no loss of capture. Safety was determined by procedural safety and the occurrence of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) within 30 days.

Methods for measuring the threshold and impedance

Impedance measurement: Using the Medtronic 5,318 temporary pacemaker (range: 200 Ω–4,000 Ω), set the voltage to 5 V and the pacing rate to the patient's baseline heart rate plus 30 beats per minute (bpm). Measure the impedance. Values below 200 Ω are recorded as 200 Ω, and values above 4,000 Ω are recorded as 4,000 Ω.

Threshold measurement: Using the Medtronic 5,318 temporary pacemaker, start with a voltage of 10 V and decrease it in increments of 1 V. The pacing rate is set to the patient's baseline heart rate plus 30 bpm. The lowest voltage that achieves stable capture for at least 10 s is defined as the threshold.

Implementation of J-Wire pacing

After the balloon or prosthetic valve is advanced over the LV wire to the aortic sinus, position the J-wire in the descending aorta at the same height as the LV wire. Connect the anode to the proximal segment of the J-wire extracorporeal sheath and the cathode to the proximal segment of the LV wire extracorporeal sheath, thereby establishing the pacing loop circuit. Measure the threshold and impedance for this configuration. The J-wire is advanced after the balloon or prosthetic valve is positioned in the aortic sinus and is withdrawn before the balloon or prosthetic valve is removed (Figure 1).

Statistical analysis

SPSS 20.0 was used for all the statistical analyses. Quantitative data are expressed as the mean ± SD or median ± quartiles. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to verify the normal distribution of the data. Student's paired t-test was used for between-group comparisons. One-way ANOVA was used to analyze comparisons among groups, and the least significant difference post hoc test or Tamhane's T2 test was used for multiple comparisons. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used for comparisons between groups with non-normally distributed data. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

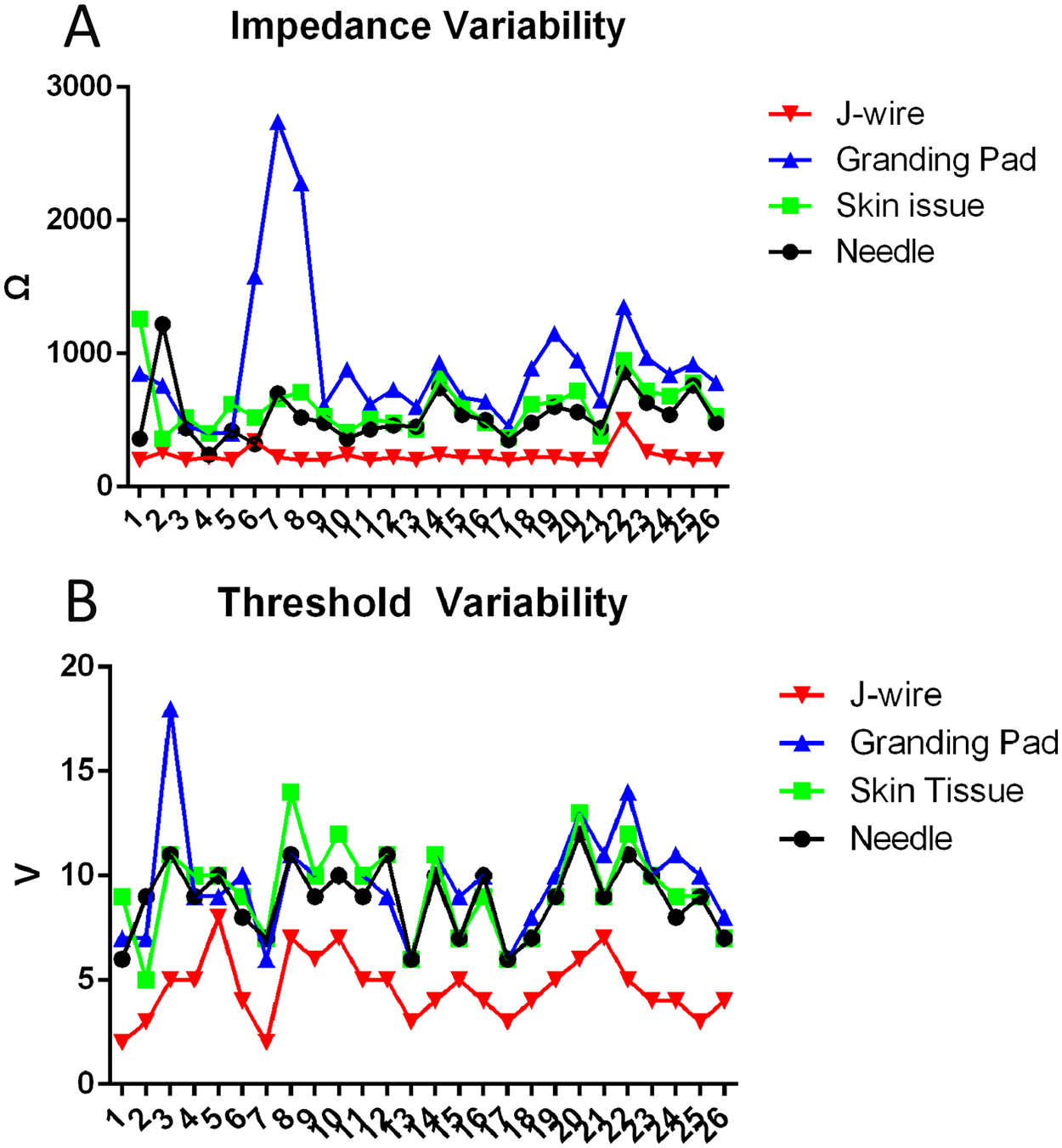

Since June 2024, our center has performed a total of 26 TAVR procedures for aortic stenosis. J-wire pacing had lower impedance (200 ± 20 Ω, P < 0.05) and pacing thresholds (4.5 ± 1 V, P < 0.05) compared to the traditional wire pacing methods. The proportion of patients with a lower impedance (≤200 Ω, 46.15%, P < 0.05) and lower pacing threshold (≤5 V, 76.92%, P < 0.05) was significantly higher and the proportion of those with a higher threshold (≥10 V, 0%, P < 0.05) was significantly lower with J-wire pacing compared to traditional wire pacing. Moreover, the J-wire pacing demonstrated better pacing impedance homogeneity, with low impedance variability, but a similar threshold variability to those of the other three methods (Figure 2). All the patients (100%) ultimately underwent pacing using the J-wire pacing technique. The impedance and threshold values for the four wire pacing methods are presented in Table 1.

Figure 2

Impedance and threshold variability in different pacing methods. (A) Impedance variability in different pacing methods. J-wire pacing exhibits the lowest pacing impedance variability, while the ground pad shows the greatest impedance variability. (B) Threshold variability in different pacing methods. The threshold variability appears to be similar across all four methods.

Table 1

| Needle | Skin tissue | Grounding pad | J-wire | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Impedance (Ω) | 480 ± 110* | 592.31 ± 194.68* | 760 ± 360* | 200 ± 20 |

| Threshold (V) | 9 ± 1.73* | 9.35 ± 2.21* | 10 ± 3* | 4.5 ± 1 |

| ≤200 Ω ratio | 0* | 0* | 0* | 12 (46.15%) |

| >4,000 Ω ratio | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ≤5 V ratio | 0* | 0* | 0* | 20 (76.92%) |

| ≥10 V ratio | 10 (38.46%)* | 12 (46.15%)* | 15 (57.69%)* | 0 |

| Number and proportion of enrolled patients (Pcs and %) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 26 (100%) |

The pacing threshold and impedance of J-wire pacing vs. traditional wire pacing, along with their distribution characteristics.

Needle: the anode was clipped to a 5 mL syringe needle that was inserted through the skin at the groin. Skin tissue: the anode was clipped to the skin incision in the femoral artery sheath. Grounding pad: the anode was connected to a grounding pad that was adhered to the chest wall over the left ventricular apex. J-wire: J-wire pacing.

Compared with J-wire pacing, P < 0.05.

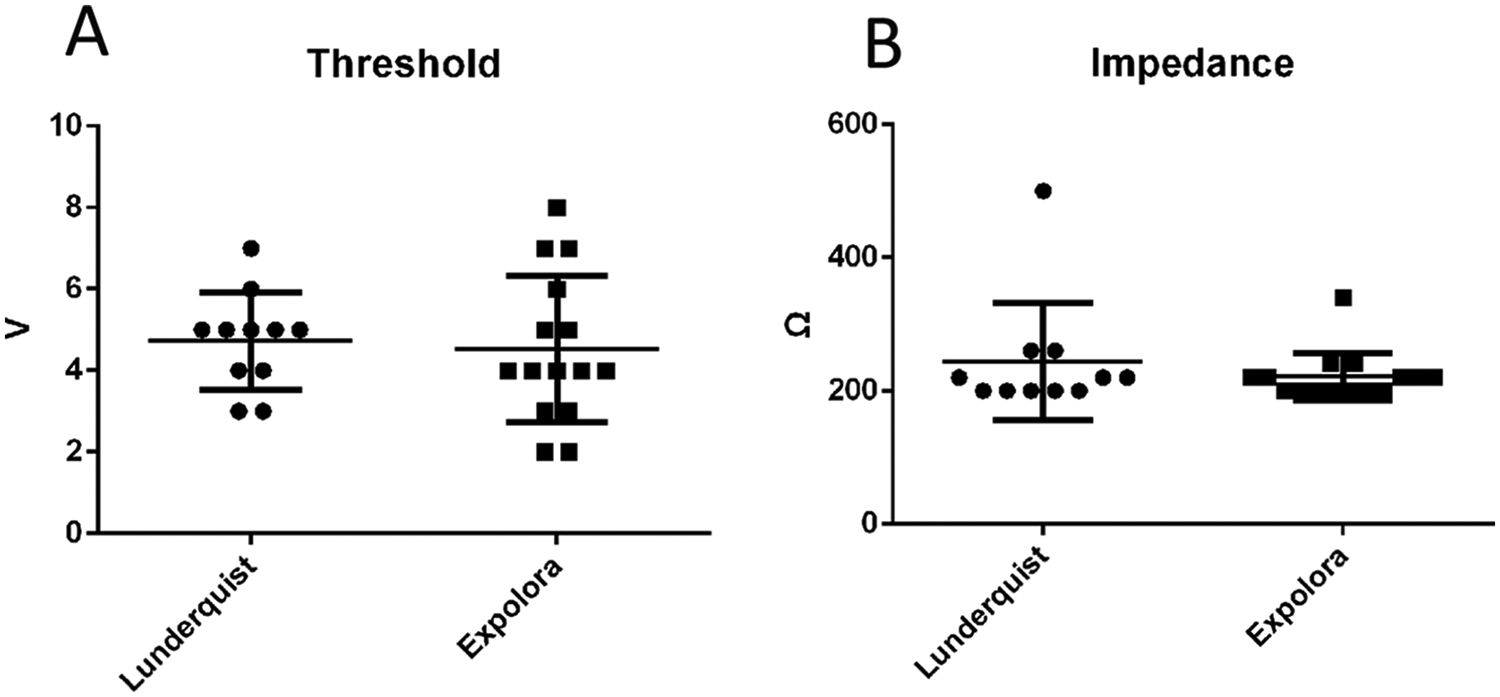

Patient baseline characteristics, procedural details, and 30-day MACE outcomes are listed in Table 2. Among these cases, self-expanding valves were used in 19 cases (73.08%) and balloon-expandable valves were used in seven cases (26.92%). Furthermore, the procedural success rate was 100% and one valve was implanted per patient. Moreover, the incidence of moderate-to-severe paravalvular leaks post-procedure, the incidence of pericardial tamponade, the rate of pacemaker implantation during hospitalization or within 30 days, and the 30-day heart failure readmission rate were all 0%. Finally, survival at 30 days was 100%. A subgroup analysis revealed no significant differences in impedance and threshold between the Lunderquist wire (William Cook European Aps, Denmark) and the Explora wire (Peijia Medial (Suzhou) Co., Ltd, China) groups (Figure 3). One patient developed a new-onset small-area intracerebral hemorrhage and was discharged on postoperative day 22 following TAVR after treatment. After TAVR, the transaortic max gradient significantly decreased (21.88 ± 8.52 mmHg vs. 106.35 ± 77.25 mmHg, P < 0.05), hemoglobin showed a slight decrease (107.42 ± 19.35 g/L vs. 119.69 ± 21.00 g/L, P < 0.05), and NT-proBNP exhibited a downward trend, though it did not reach statistical significance (1,213 ± 3,226.5 vs. 3,327.5 ± 7,298, P = 0.061). There were no significant differences in creatinine levels or left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF).

Table 2

| Characteristic | J-wire pacing |

|---|---|

| Number/percentage | 26 (100%) |

| Age (years) | 72.81 ± 8.16 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 18 (69.23%) |

| Female | 8 (30.77) |

| Body mass index | 22.59 ± 5.11 |

| Hypertension | 16 (61.54%) |

| Diabetes | 8 (30.77%) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1 (3.85%) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 5 (19.23%) |

| Coronary artery disease | 6 (23.08%) |

| Stroke | 5 (23.08%) |

| Previous aortic valve replacement | 0 |

| Previous pacemaker | 0 |

| Creatinine (pre-op vs. post-op), μmol/L | 103.08 ± 78.70 vs. 104.31 ± 107.88 |

| Hemoglobin (pre-op vs. post-op), g/L | 119.69 ± 21.00 vs. 107.42 ± 19.35* |

| LVEF (pre-op vs. post-op) | 58.92 ± 9.00 vs. 60.46 ± 7.76 |

| Transaortic max gradient, mmHg (pre-op vs. post-op) | 106.35 ± 77.25 vs. 21.88 ± 8.52* |

| NT-proBNP (pre-op vs. post-op), ng/L | 3,327.5 ± 7,298 vs. 1,213 ± 3,226.5 |

| SAPIEN 3 valve | 7 (26.92%) |

| Taurus Elite valve | 15 (57.69%) |

| Venus A valve | 4 (15.38%) |

| LV wire: Lunderquist | 11 (42.31%) |

| LV wire: Explora | 15 (57.69%) |

| Efficacy of pacing stimulation | 26 (100%) |

| Pre-dilation | 22 (88%) |

| Post-dilation | 8 (30.77%) |

| One prosthetic heart valve device implanted | 26 (100%) |

| Procedural success | 26 (100%) |

| Postprocedural paravalvular leak | |

| None | 8 (30.77%) |

| Trivial | 8 (30.77%) |

| Mild | 10 (38.46%) |

| Incidence of pericardial tamponade | 0 |

| J-wire access site vascular complications | 0 |

| 30-day heart failure readmission rate | 0 |

| Rate of temporary or permanent pacemaker implantation within 30 days | 0 |

| Incidence of 30-day stroke | 1 |

| Incidence of 30-day myocardial infarction | 0 |

Patient baseline characteristics, procedural details, and 30-day MACE outcomes.

LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LV, left ventricular.

P < 0.05.

Figure 3

Threshold and impedance in the Lunderquist wire and Explora wire groups. (A) Thresholds in the Lunderquist wire and Explora wire groups. There was no significant difference between the groups. (B) Impedance in Lunderquist wire and Explora wire groups. There was no significant difference between the groups.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that the J-wire pacing technique is straightforward and technically simple. In our preliminary studies, we found that positioning the J-wire in the aortic arch or aortic sinus did not reduce its pacing impedance or threshold (4). Instead, it carried risks of aortic injury and interference with valve deployment. Therefore, we opted to place the J-wire in the descending aorta at the same height as the left ventricular guidewire. Compared to traditional wire pacing methods, it retains their established advantages while effectively overcoming key limitations. First, it significantly reduces the pacing threshold and impedance. The intraoperative pacing voltage was maintained at least twice the pacing threshold, a requirement that could not be consistently met with traditional guidewire pacing due to its inherently high threshold. This protocol thus fully guaranteed pacing efficacy, thereby mitigating the risks of leaflet laceration, valve displacement, or procedural failure resulting from loss of capture, expanding the applicability of wire pacing, and enhancing its safety and efficacy. The lower impedance and threshold observed with J-wire pacing compared to traditional guidewire pacing may be attributed to the closer proximity of the J-wire to the left ventricular guidewire, along with the effective electrical isolation provided by the balloon or valve delivery system and the arterial sheath between the two wires. A subgroup analysis indicated no significant difference in impedance or threshold between the Lunderquist wire and the Explora wire groups, suggesting that the type of guidewire had no notable impact on these parameters. Additionally, the surgical success rate was 100% in both groups. Second, J-wire pacing avoids the risk of tissue injury associated with subcutaneous needle puncture or clamping of subcutaneous tissue with alligator clips. Third, it eliminates involuntary muscle contractions around the puncture needle or alligator clips during pacing. Traditional wire pacing demonstrates similar or even superior safety and efficacy profiles compared to right ventricular pacing. Right ventricular pacing not only leads to a higher risk of groin hematoma and cardiac tamponade but also prolongs both procedural and fluoroscopy times, increasing the financial burden on patients. Tjong et al. (5) reported a vascular complication incidence of 2.0% and cardiac perforation incidence of 1.6% in patients who underwent right ventricular pacing. Multiple studies have confirmed a higher vascular and cardiac perforation complication rate in right ventricular pacing than in LV pacing (3). Due to ethical considerations, this study did not directly compare J-wire pacing with RV pacing nor did it establish a randomized control group. Instead, it directly compared J-wire pacing with conventional guidewire pacing and selected the method with the lowest threshold and impedance as the preferred pacing approach. All 26 patients (100%) were assigned to the J-wire pacing group and the procedural success rate was 100%. J-wire pacing may demonstrate superior safety and efficacy compared to traditional wire pacing methods. Consequently, when compared to RV pacing, J-wire pacing is likely non-inferior, or potentially even superior, in terms of both safety and efficacy.

Limitations

This study confirms the safety and efficacy of J-wire pacing. However, the following limitations should be acknowledged: (1) Single-center experience with limited sample size: This report represents a single-center experience with a small number of cases and larger, multi-center studies are needed to validate these findings; (2) Lack of randomized comparison to RV pacing: This study did not employ a randomized controlled design comparing J-wire pacing directly to RV pacing and randomized controlled trials are required to definitively establish the comparative safety and efficacy of J-wire pacing vs. RV pacing; (3) Sheath size limitation for balloon-expandable valves: In cases using balloon-expandable valves, the 14F femoral sheath could not simultaneously accommodate both the valve delivery system and the J-wire. Therefore, the auxiliary access sheath had to be upgraded to an 8F sheath to facilitate J-wire insertion; and (4) Potential for sheath oozing: In some patients, predominantly those receiving balloon-expandable valves, the slow oozing of blood from the hub of the arterial sheath was observed after J-wire insertion. To mitigate this, we minimized the time the J-wire remained in the descending aorta by withdrawing it after balloon or valve positioning and immediately prior to balloon or delivery system removal.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

This study involving humans was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hainan Provincial People's Hospital (Approval No. EC-JS-2024-134-01). This study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

RM: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LZ: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. WL: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. SW: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. The present study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 82160074) and the Hainan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 820MS131 and 822RC811).

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend our appreciation to Dr. Haixia Tang and Dr. Duozhi Wu for their guidance.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Hilling-Smith R Cockburn J Dooley M Parker J Newton A Hill A et al Rapid pacing using the 0.035-in. retrograde left ventricular support wire in 208 cases of transcatheter aortic valve implantation and balloon aortic valvuloplasty. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. (2017) 89(4):783–6. 10.1002/ccd.26720

2.

Blusztein D Raney A Walsh J Nazif T Woods C Daniels D . Best practices in left ventricular pacing for transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Struct Heart. (2023) 7(6). 10.1016/j.shj.2023.100213

3.

Yildirim A Genc O Evlice M Pacaci E Sezici E Cabbar Karakurt B et al Comparative analysis of direct routine left ventricular guidewire pacing and right ventricular pacing: faster and safer approach to TAVR. Kardiol Pol. (2025) 83:850–60. 10.33963/v.phj.106555

4.

Ma R Liao W Zhang L Wang S . Case report: optimized guidewire pacing in transcatheter aortic valve replacement combined with complex PCI in a patient with severe aortic stenosis and regurgitation. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2025) 12. 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1515954

5.

Tjong FVY Ruijter UW Beurskens NEG Knops RE . A comprehensive scoping review on transvenous temporary pacing therapy. Netherlands Hear J. (2019) 27:462–73. 10.1007/s12471-019-01307-x

Summary

Keywords

aortic stenosis, J-wire pacing, right ventricular pacing, traditional wire pacing, transcatheter aortic valve replacement

Citation

Ma R, Zhang L, Liao W and Wang S (2026) Optimizing the wire pacing technique in transcatheter aortic valve replacement procedures: the experience of using J-wire pacing at a single center. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 12:1709297. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1709297

Received

20 September 2025

Revised

07 December 2025

Accepted

29 December 2025

Published

27 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Andreas Kalogeropoulos, Mitera Hospital, Greece

Reviewed by

Damyan Boychev, Sofiamed University Hospital, Bulgaria

Tohru Takaseya, Kurume University, Japan

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Ma, Zhang, Liao and Wang.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Sheng Wang cardiohn@163.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.