Abstract

Lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] is a well recognised contributor in the development of cardiovascular disease. Unlike other lipoproteins, Lp(a) levels are primarily genetically determined, and in most individuals remain largely stable throughout life. Elevated Lp(a) is common in the general population, and various international guidelines now recommend at least one lifetime measurement of Lp(a) and its inclusion into an individual's cardiovascular risk assessment. Despite this, Lp(a) is still rarely measured, even in patients with known cardiovascular risk factors. Critically, the therapeutic landscape for Lp(a)-lowering medications is rapidly evolving with multiple drugs showing considerable promise in late-stage clinical trials. The strength and consistency of the evidence now cement Lp(a) as an essential biomarker of cardiovascular health. Failure to incorporate measurement of Lp(a) into clinical practice will continue to underestimate an individual's risk of CVD. Now is the time for Lp(a) to move from a neglected biomarker to a widely known and measured essential component of cardiovascular risk assessment.

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death worldwide, with over 19.4 million deaths reported in 2021 (1). It is estimated that by adapting to lifestyle changes, 75% of cardiovascular mortality can be reduced (2). However, for some individuals, a residual risk of CVD remains despite a reduction in traditional risk factors (3). Lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] has been established as an independent and causal risk factor for the development of CVD (4). Various guidelines including those issued by the European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS) and the National Lipid Association (NLA) recommend the measurement of Lp(a) in adults to identify individuals at high cardiovascular risk (5, 6). Despite this well-known relationship, Lp(a) is not routinely measured as part of cardiovascular risk assessments. In this perspective article, we argue that the omission of widespread Lp(a) testing represents a critical gap in contemporary cardiovascular risk assessments. We suggest that cardiovascular risk assessment must evolve from a narrow focus on modifiable lifestyle factors to a more comprehensive model that integrates the genetically determined risk, Lp(a). This article highlights historical barriers that have hindered widespread adoption of Lp(a) testing and outlines strategies to overcome them. Furthermore, this article discusses the rapidly evolving landscape of Lp(a)-lowering therapies, which may provide targeted benefit to individuals with elevated Lp(a) and residual cardiovascular risk. Considering the high proportion of the population who are estimated to have high Lp(a), and the potential approval of novel therapies, it is critical that Lp(a) is urgently incorporated into standard cardiovascular risk assessment.

Lp(a) and its impact on cardiovascular health

Understanding of Lp(a) and its effects on cardiovascular health is currently limited among the general public. Lp(a) is a variant of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, which is synthesised in the liver (7). In contrast to LDL-cholesterol, which is strongly influenced by diet and pharmacotherapy, Lp(a) levels remain relatively stable throughout a person's life (7). Non-genetic factors can also influence blood levels of Lp(a), including comorbidities such as chronic kidney disease, thyroid dysfunction, acute inflammation and medications (5). Unlike other lipoproteins, lifestyle changes are typically ineffective at lowering Lp(a) levels.

Lp(a) contributes to CVD through four main mechanisms: atherogenesis, thrombosis, calcification, and vascular inflammation (8). Lp(a) is estimated to be 5–6 times more atherogenic than LDL-cholesterol (9). Lp(a) is the predominant carrier of oxidised phospholipids in blood; oxidised phospholipids activate the innate immune system causing inflammation and calcification (8). Lp(a) may also contribute to thrombosis through antifibrinolytic interaction with platelets due to structural similarities with plasminogen (9). Numerous large-scale studies have established that Lp(a) is a causal factor in the development of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) and aortic valve stenosis (4). Data from the Copenhagen General Population Study reported that elevated Lp(a) levels are associated with increased risk for the development of aortic valve stenosis, myocardial infarction, heart failure and ischaemic stroke (5, 6).

Challenges with routine screening for Lp(a) in clinical practice

Despite research demonstrating the importance of measuring Lp(a) in cardiovascular risk assessments, Lp(a) is not routinely measured. For example, in a recent study of six medical centres in the University of California health system, Lp(a) testing was only undertaken for 0.3% of patients, and in <4% of patients with a personal history of cardiovascular disease (10). Similarly, in a German study of 2018 health records from 9 million patients, only 0.34% of these individuals received an Lp(a) test (11). The lack of routine Lp(a) measurements may be due, in part to the multiple challenges associated with the measurement and reporting of Lp(a).

The first major challenge in the adoption of Lp(a) is linked to the measurement variability in the size of the Lp(a) isoforms. The molecular weight of Lp(a) isoforms can vary from 275 to 800 kDa due to variability in the size of the apolipoprotein(a) domain (12). As Lp(a) immunoassays typically use polyclonal antibodies which bind to the apolipoprotein(a) domain, detection of Lp(a) varies widely depending on the antibodies used, with Lp(a) typically underestimated in individuals with small isoforms and overestimated in those with larger isoforms (13). These differences in Lp(a) detection contributed to conflicting results in early Lp(a) population studies where the relationship between Lp(a) levels and cardiovascular risk was unclear because of the use of isoform sensitive assays (12). Historically, these differences in measurement reduced confidence in Lp(a) as a consistent marker of CVD. Modern Lp(a) immunoassays rely on the use of multiple calibrators which span a large range of Lp(a) concentrations and apolipoprotein(a) isoforms to determine Lp(a) levels more accurately and mitigate isoform size differences (7). Although no Lp(a) assay is entirely isoform insensitive, currently assays based on Denka Seiken reagents, which employ the use of five calibrators, that contain a range of apolipoprotein(a) isoforms, are regarded as the most isoform insensitive (12). The Northwest Research Lipid Laboratory in the University of Washington provides an Lp(a) certification process which compares the performance of Lp(a) immunoassays to a monoclonal antibody-based ELISA (12). A remaining issue concerns the internationally accepted calibrator material (WHO/IFCC SRM-2B) for Lp(a) which is almost depleted (14). A new mass spectrometry-based reference has been developed (15) with new serum reference materials estimated to be provided by the International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine in 2025 (16). It is critical that once new standards are available, that Lp(a) assays are updated and aligned to the new material to ensure consistency of Lp(a) measurements.

Differences in the measurement units reported by different immunoassays are the second challenge in the adoption of Lp(a). Historically, Lp(a) assays were reported in mass units, which incorrectly assume that the mass of Lp(a) proteins are consistent (7). To account for this, consensus guidelines now recommend reporting of Lp(a) in molar units (17). While conversion factors between molar and mass units exist, these conversions are approximate estimates and may be inaccurate depending on an individual's Lp(a) isoform size and are generally not recommended (5). These inconsistencies in Lp(a) reporting have impacted the confidence in use of Lp(a) in clinical practice with results given in different units contributing to confusion with risk interpretation but adherence to the consensus guidelines will mitigate this issue.

In efforts to standardise the measurement of Lipoprotein(a), HEART UK, a UK-based cholesterol charity, issued a consensus statement in 2019 with recommendations on the measurement of Lp(a) in laboratories (18). These recommendations suggest: (i) Lp(a) should be measured using a method with appropriate antibodies where the effect of isoform size is minimised and calibrators are certified to the WHO/IFCC reference material, (ii) Lp(a) concentrations are reported in nmol/L units, (iii) conversion between mass and molar units is inaccurate and should be discouraged and, (iv) the use of assays using Denka-based reagents with WHO/IFCC reference material reported in nmol/L (18). However, in a 2021 survey of UK clinical laboratories, only 5% of laboratories had fully implemented the HEART UK recommendations with most laboratories unsure of the Lp(a) methods they were using (13). It is imperative that laboratories readily adopt the HEART UK recommendations to ensure that widespread Lp(a) testing is consistent and doesn't contribute to any further measurement confusion.

The third challenge in the adoption of Lp(a) is the lack of a universal consensus on what ‘cut-off’ level should be used to assign an individual as having high Lp(a) levels (9). Cardiovascular risk increases linearly with rising Lp(a) concentrations, but the absolute risk attributable to Lp(a) depends heavily on the presence of other cardiovascular risk factors, which makes determination of precise ‘cut-off’ levels challenging (19). Despite this, various groups have suggested different thresholds to determine increased risk of CVD for a given Lp(a) level. The EAS defined three Lp(a) risk categories based on Lp(a) level: rule-in risk [Lp(a) > 125 nmol/L or >50 mg/dL], grey zone [Lp(a) 75–125 nmol/L or 30–50 mg/dL] and rule out risk [Lp(a) < 75 nmol/L or <30 mg/dL] (5). Conversely, HEART UK defines four cardiovascular risk categories based on Lp(a) levels: minor risk (32–90 nmol/L; 18–40 mg/dL), moderate risk (90–200 nmol/L; 40–90 mg/dL), high risk (200–400 nmol/L; 90–180 mg/dL) and very high risk (400 nmol/L; 180 mg/dL) (17). In recent years, there have been some efforts to standardise cut-off thresholds. For example, in 2019 guidelines from the NLA, an Lp(a) level ≥100 nmol/L (≥50 mg/dL) cut-off was recommended to indicate high risk (20). In 2024, the NLA changed their recommendations to align with the EAS risk cut-off of >125 nmol/L (>50 mg/dL) (6). Differences in the clinical interpretation of Lp(a) risk thresholds continue to hinder the integration of Lp(a) into clinical practice guidelines. The incorporation of Lp(a) consensus risk thresholds into guidelines issued by clinical organisations such as the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) would go a long way to consolidating clinical approaches to Lp(a) risk assignment.

Historically it has been challenging to measure Lp(a) for the reasons presented above, however, improvements in immunoassays, standards and clinical guidelines have mitigated these challenges to allow for confident routine measurement of Lp(a) as part of cardiovascular risk assessments. Importantly, measurement of Lp(a) using the most readily available assay (whether reported in molar or mass units) is preferable than no measurement of Lp(a) (21).

Population burden of Lp(a) and its risk implications

Global modelling studies estimate that more than 1.8 billion people have an elevated Lp(a) level (22). Lp(a) concentrations vary across ethnic groups due to genetic differences. Black and South Asian individuals have higher median Lp(a) levels compared with White and Chinese individuals, based on data from the UK Biobank (19). Despite these population differences, the relative risk associated with elevated Lp(a) (>150 nmol/L) appears consistent across groups (19).

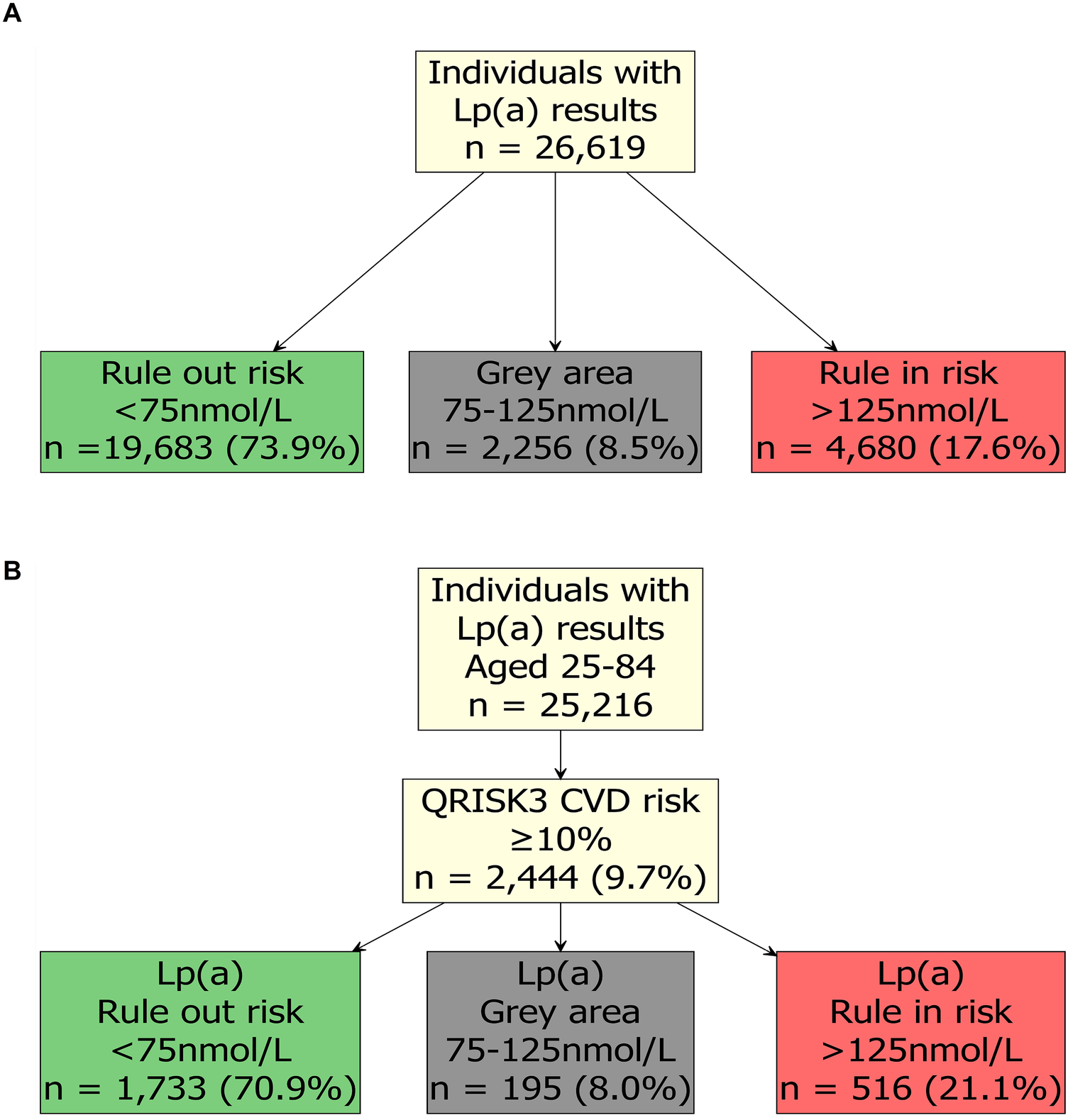

Cardiovascular risk rises linearly with increasing Lp(a) concentrations, but the absolute risk depends strongly on the coexistence of other risk factors. As a result, current CVD risk assessment tools that do not incorporate Lp(a), such as QRISK3, may substantially underestimate true risk. We examined anonymised retrospective data from health-aware individuals who attended a Randox Health Clinic in the UK for general health screening checks. In this UK-based cohort, 17.6% (4,680/26,619) of individuals with Lp(a) results were identified as ‘rule in’, (increased risk of CVD), based on EAS guidelines (Figure 1A). A further 8.5% (2,256/26,619) had Lp(a) results in the ‘grey area’ (75–125 nmol/L), and 73.9% (19,683/26,619) were identified as ‘rule out’ (not at increased risk) (Figure 1A). Considering how common elevated Lp(a) is, it is important that at-risk individuals are made aware of their increased risk of CVD [based on Lp(a)], and the importance of the management of controllable CVD risk factors, such as elevated blood pressure, LDL-cholesterol, and glucose (5). Moreover, it may also be beneficial for individuals in the grey area to be retested, at a future date, for Lp(a); a recent study found that 53% of individuals in the grey area transitioned to different risk categories following a repeat Lp(a) measurement (23).

Figure 1

Lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] results from health-aware individuals. (A) Lp(a) results and risk level in health-aware individuals according to European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS) guidelines. (B) QRISK3 score and Lp(a) results in health-aware individuals according to NICE and EAS guidelines. Results were from individuals that attended a Randox Health Clinic for a health check within the UK between July 2023 and June 2025. Serum Lp(a) levels were determined by Randox Clinical Laboratory Services (RCLS; ISO17025 accredited) using a Lipoprotein(a) assay (LP3403, Randox Laboratories Ltd.) on an RX Imola analyser (Randox Laboratories Ltd.) and Lp(a) categories were assigned ‘rule out’ risk (green), ‘grey area’ (grey) and ‘rule in’ risk (red) based on the European Atherosclerosis Society guidelines (5). Consent was provided by the individuals for their data to be used for research purposes, and the analysis was reviewed and approved by Ulster University, School of Biomedical Sciences Ethics Filter Committee (Project Number: FCBMS-25-104-A). 10-year QRISK3 (2017) score was estimated using the QRISK3 package (https://cran.r-project.org/package=QRISK3).

To simulate how these individuals would be assigned cardiovascular risk following UK NICE guidelines (24), we estimated their 10-year QRISK3 (2017) score using the QRISK3 package (https://cran.r-project.org/package=QRISK3) in R (25). As NICE only recommends use of QRISK3 for people aged 25–84, we excluded n = 1,403 individuals outside of this age range. In this cohort, 9.7% (2,444/25,216) had an estimated QRISK3 score of 10%, or greater (Figure 1B). For patients with a QRISK3 score of 10% or more, the standard approach to treatment in the UK is statin therapy alongside lifestyle modification (26). Alarmingly, in individuals who had a ≥10% QRISK3 score, 21.1% (516/2,444) also had a ‘rule in’ risk level of Lp(a) > 125 nmol/L (Figure 1B); these individuals may require more intensive lipid-lowering management and monitoring. Individuals in the ‘grey area’ [8.0% (195/2,444)] may require an additional test to define their Lp(a) risk.

Inclusion of Lp(a) in cardiovascular risk assessments

Given its strong association with cardiovascular events, and the limitations of current risk models, there is a compelling case for including Lp(a) in CVD risk calculators such as QRISK3. The Lipoprotein(a) taskforce has called for standardisation of Lp(a) screening and measurement, inclusion of Lp(a) into CVD risk calculators, and inclusion of Lp(a) within clinical guidelines (27). Recently, at an Lp(a) Global Summit, the Brussels International Declaration on Lp(a) Testing and Management was published calling for integration of Lp(a) into Global Cardiovascular health plans, establishment of Lp(a) testing policy, and a commitment to ensure systematic Lp(a) testing is offered to all individuals, at least once (28).

Various studies have demonstrated that inclusion of Lp(a) levels into existing CVD risk calculators such as SCORE and PREVENT would improve estimation of cardiovascular risk (29–33). Inclusion of Lp(a) into pre-existing risk calculators would assist clinicians in identifying individuals at high risk who might otherwise be missed. Furthermore, early identification would allow for more aggressive management of modifiable risk factors, potentially reducing the risk of heart attacks and strokes.

Various online tools such as the Lp(a) clinical guidance calculator (https://www.lpaclinicalguidance.com/) have been developed to assess risk of heart attack and stroke by age 80. In a recent case study of a patient who had an abnormal lipid profile, and a family history of CVD, the patient's risk of heart attack or stroke was calculated as 17%. However, with the inclusion of Lp(a) in the risk calculation, the patient's updated risk of heart attack or stroke more than doubled, to 40% (34). Additionally, the Lp(a) clinical guidance calculator estimates how risk can be decreased by lowering blood pressure and LDL-cholesterol levels. As Lp(a) measurement becomes more integrated into clinical practice, visualisation tools will become important in helping clinicians and individuals to understand the risk and how lifestyle, or medication interventions can help to mitigate risk.

Lp(a) treatment and novel therapies

A further complication in the clinical management of elevated Lp(a) levels is the lack of approved medication options to lower Lp(a) levels. Lipoprotein apheresis can significantly reduce Lp(a) levels by >60% (35), but is typically reserved for patients who have high cholesterol levels which are unresponsive to medication, or those with familial hypercholesterolemia (36). Additionally, lipid apheresis is limited to specialist lipid clinics, is expensive and requires repeat apheresis appointments (8, 35).

The most cost-effective approach to managing risk attributable to elevated Lp(a) involves comprehensive risk reduction through the optimisation of all other modifiable cardiovascular risk factors (5). This includes aggressive control of non-HDL cholesterol, blood pressure, blood glucose, and lifestyle factors such as smoking cessation, physical activity, and dietary improvements. Since Lp(a) levels are largely unaffected by lifestyle changes or conventional lipid-lowering therapies like statins, clinicians must focus on holistic cardiovascular risk management (37).

Reductions in Lp(a) can be achieved using proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors, such as alirocumbab and evolocumab. In trials evaluating evolocumab usage for LDL cholesterol reduction, post hoc analyses showed reductions in Lp(a) levels by 15.5%–31.3% (9). Similarly, alirocumab administration reduced Lp(a) levels by ∼30% on average (9). However, PCSK9 inhibitors were not developed to specifically target Lp(a) and have not been approved for lowering Lp(a) levels (38).

Although there is currently an absence of approved medications specifically targeting Lp(a), the therapeutic landscape is rapidly evolving. Several novel pharmacological agents which target Lp(a) synthesis are in various stages of clinical development, with many showing promise in significantly lowering Lp(a) levels (Supplementary Table S1). Three Lp(a)-lowering drugs which are currently undergoing phase III clinical trials are Pelacarsen, Olpasiran and Lepodisiran (38). All three therapies target liver synthesis of the apolipoprotein(a) mRNA, either as antisense oligonucleotide therapy (Pelacarsen) (39) or a small interfering RNA (Olpasiran and Lepodisiran). Each of the therapies have demonstrated remarkable reductions of Lp(a) levels of 80% (Pelacarsen) (40), 101.1% (Olpasiran) (41) and 94% (Lepodisiran) (42). Ongoing phase III clinical trials [Lp(a)HORIZON (39), OCEAN(a) Outcomes (https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05581303) and ACCLAIM-Lp(a) (https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06292013)] will assess the efficacy of the therapies in reducing Lp(a) levels.

Despite current development in Lp(a) lowering therapies, it is not clear how much of a reduction in Lp(a) is needed for a clinically relevant reduction in cardiovascular events (9). The results of ongoing phase III trials will be critical in determining whether these reductions translate into meaningful clinical outcomes, such as fewer MACE events. As the evidence base grows, these therapies may soon offer targeted treatment options for individuals with elevated Lp(a).

Importantly, the establishment of widespread Lp(a) testing is an essential first step in identifying which individuals will require Lp(a) lowering treatments. Consistency between Lp(a) measurements will prove fundamental to tracking reductions in Lp(a) and will be critical in proving the efficacy of Lp(a) lowering drugs. Pharmaceutical companies should be aware of the issues regarding Lp(a) measurement and should ensure they use the most appropriate Lp(a) assays when assessing treatment efficacy.

Conclusion

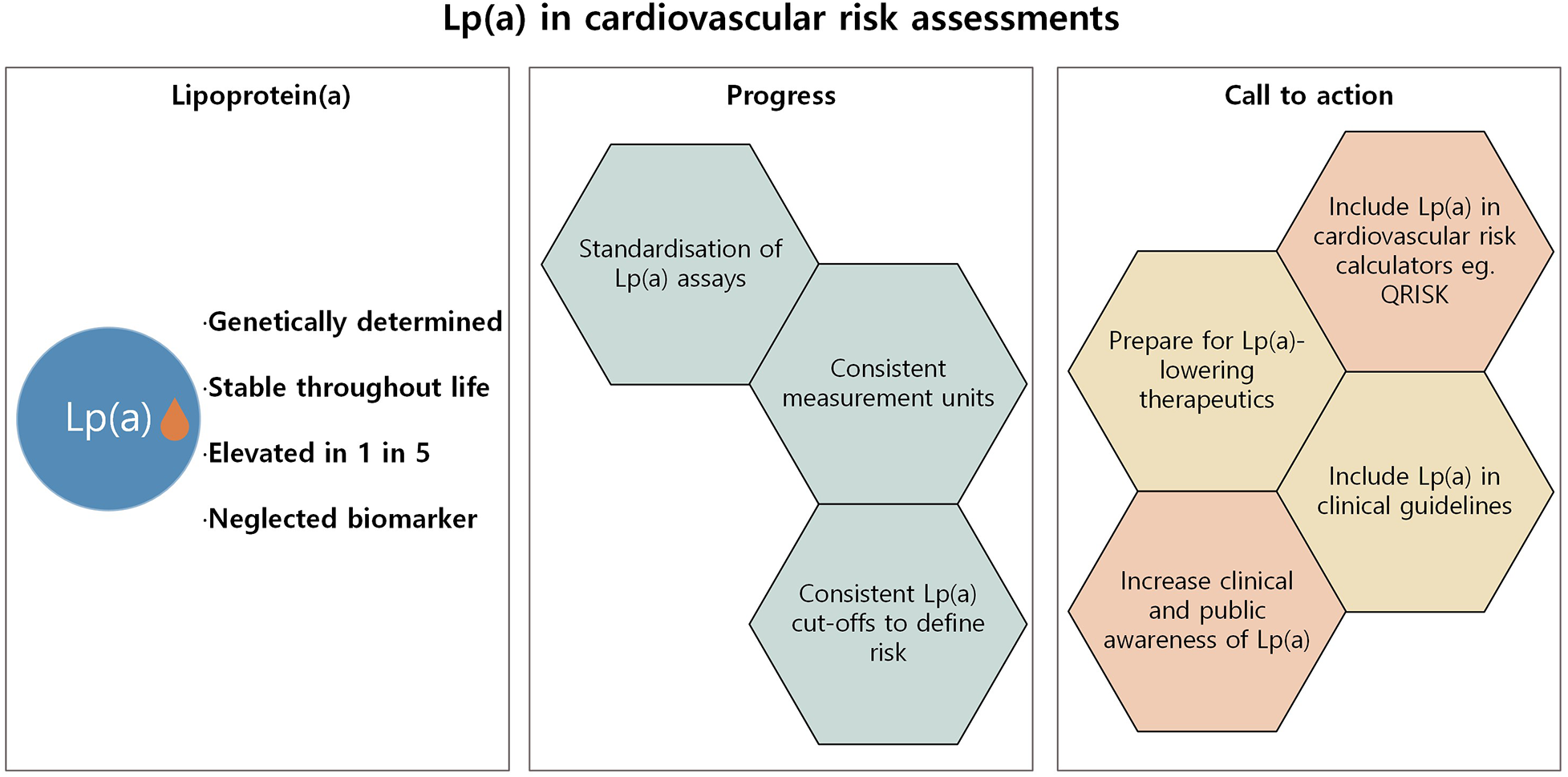

Lp(a) represents a critical, yet often overlooked, component of cardiovascular risk (Figure 2). As a genetically determined and largely unmodifiable risk factor, elevated Lp(a) poses a significant threat to heart and vascular health, independent of traditional lipid markers. The Brussels International Declaration has made the call clear: integrate Lp(a) into global cardiovascular health strategies, establish testing policies, and ensure every individual is tested at least once. Cardiovascular risk assessments must evolve to include Lp(a) allowing for proactive intervention which is key to preventing life-altering cardiovascular events for millions of individuals worldwide. There is a need now to increase awareness among clinicians and the general public of Lp(a) as an essential marker of cardiovascular health. With improved awareness, evolving clinical guidelines, and promising therapies on the horizon, now is the time for Lp(a) to become an integral part of cardiovascular risk assessments.

Figure 2

Summary of progress and further action required to integrate Lp(a) into cardiovascular risk assessments.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ulster University School of Biomedical Sciences Ethics Filter Committee (Project Number: FCBMS-25-104-A). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

AI: Data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JW: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. MK: Writing – review & editing. LM: Writing – review & editing. JC-M: Writing – review & editing. TK-A: Writing – review & editing. JL: Writing – review & editing. LD: Writing – review & editing. PF: Conceptualization, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. MR: Conceptualization, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

AI, JW, MK, LM, JL and MR are employees of Randox Laboratories Ltd., but hold no shares in the company. PF is the Managing Director and owner of Randox Laboratories Ltd. MR is an employee of Randox Health Ltd., but holds no shares in the company. JC-M is Chief Medical Officer and TK-A is Director of Medicine at Andarta Health and Performance, a private healthcare institute that has received support and funding from Randox Healthcare Ltd.

The remaining author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcvm.2025.1710557/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

IHME. Global Burden of Disease 2021: Cardiovascular Diseases- Level 2 Cause (2024). Available online at:www.thelancet.com(Accessed June 23, 2025).

2.

Panattoni G Desimone P Toto F Meringolo F Jacomelli I Rebecchi M et al Cardiovascular risk assessment in daily clinical practice: when and how to use a risk score. Eur Heart J. (2025) 27:i16–21. 10.1093/eurheartjsupp/suae100

3.

Dhindsa DS Sandesara PB Shapiro MD Wong ND . The evolving understanding and approach to residual cardiovascular risk management. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2020) 7:88. Frontiers Media S.A. 10.3389/fcvm.2020.00088

4.

Doherty S Hernandez S Rikhi R Mirzai S De Los Reyes C McIntosh S et al Lipoprotein(a) as a causal risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep. (2025) 19:8. Springer. 10.1007/s12170-025-00760-1

5.

Kronenberg F Mora S Stroes ESG Ference BA Arsenault BJ Berglund L et al Lipoprotein(a) in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and aortic stenosis: a European atherosclerosis society consensus statement. Eur Heart J. (2022) 43:3925–46. Oxford University Press. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehac361

6.

Koschinsky ML Bajaj A Boffa MB Dixon DL Ferdinand KC Gidding SS et al A focused update to the 2019 NLA scientific statement on use of lipoprotein(a) in clinical practice. J Clin Lipidol. (2024) 18(3):e308–19. 10.1016/j.jacl.2024.03.001

7.

Reyes-Soffer G Ginsberg HN Berglund L Duell PB Heffron SP Kamstrup PR et al Lipoprotein(a): a genetically determined, causal, and prevalent risk factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. (2022) 42(1):E48–60. 10.1161/ATV.0000000000000147

8.

Duarte Lau F Giugliano RP . Lipoprotein(a) and its significance in cardiovascular disease: a review. JAMA Cardiol. (2022) 7:760–9. American Medical Association. 10.1001/jamacardio.2022.0987

9.

Greco A Finocchiaro S Spagnolo M Faro DC Mauro MS Raffo C et al Lipoprotein(a) as a pharmacological target: premises, promises, and prospects. Circulation. (2025) 151:400–15. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.124.069210

10.

Bhatia HS Hurst S Desai P Zhu W Yeang C . Lipoprotein(a) testing trends in a large academic health system in the United States. J Am Heart Assoc. (2023) 12(18):e031255. 10.1161/JAHA.123.031255

11.

Stürzebecher PE Schorr JJ Klebs SHG Laufs U . Trends and consequences of lipoprotein(a) testing: cross-sectional and longitudinal health insurance claims database analyses. Atherosclerosis. (2023) 367:24–33. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2023.01.014

12.

Cegla J France M Marcovina SM Neely RDG . Lp(a): when and how to measure it. Ann Clin Biochem. (2021) 58:16–21. SAGE Publications Ltd. 10.1177/0004563220968473

13.

Ansari S Garmany Neely RD Payne J Cegla J . The current status of lipoprotein (a) measurement in clinical biochemistry laboratories in the UK: results of a 2021 national survey. Ann Clin Biochem. (2024) 61(3):195–203. 10.1177/00045632231210682

14.

International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine. Update on Reference Materials for Apolipoproteins (2021). Available online at:https://ifcc.org/ifcc-scientific-division/sd-working-groups/wg-apo-ms/ (Accessed August 8, 2025)

15.

Ruhaak LR Romijn FPHTM Begcevic Brkovic I Kuklenyik Z Dittrich J Ceglarek U et al Development of an LC-MRM-MS-based candidate reference measurement procedure for standardization of serum apolipoprotein (a) tests. Clin Chem. (2023) 69(3):251–61. 10.1093/clinchem/hvac204

16.

International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine. Metrological Traceability of Serum Apolipoproteins: Transitioning to an SI-Traceable Reference Measurement System (2024). Available online at:https://ifcc.org/ifcc-scientific-division/sd-working-groups/wg-apo-ms/ (Accessed August 8, 2025)

17.

Kenkre JS Mazaheri T Neely RDG Soran H Datta D Penson P et al Standardising lipid testing and reporting in the United Kingdom; a joint statement by HEART UK and the association for laboratory medicine. Ann Clin Biochem. (2025) 62:257–86. SAGE Publications Ltd. 10.1177/00045632251315303

18.

Cegla J Neely RDG France M Ferns G Byrne CD Halcox J et al HEART UK consensus statement on lipoprotein(a): a call to action. Atherosclerosis. (2019) 291:62–70. Elsevier Ireland Ltd. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2019.10.011

19.

Patel AP Wang M Pirruccello JP Ellinor PT Ng K Kathiresan S et al Lp(a) (lipoprotein[a]) concentrations and incident atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease new insights from a large national biobank. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. (2021) 41(1):465–74. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.120.315291

20.

Wilson DP Jacobson TA Jones PH Koschinsky ML McNeal CJ Nordestgaard BG et al Use of lipoprotein(a) in clinical practice: a biomarker whose time has come. A scientific statement from the national lipid association. J Clin Lipidol. (2019) 13(3):374–92. 10.1016/j.jacl.2019.04.010

21.

Sosnowska B Toth PP Razavi AC Remaley AT Blumenthal RS Banach M . 2024: the year in cardiovascular disease—the year of lipoprotein(a). research advances and new findings. Arch Med Sci. (2025) 21:355–73. Termedia Publishing House Ltd. 10.5114/aoms/202213

22.

Tsimikas S Stroes ESG . The dedicated “lp(a) clinic”: a concept whose time has arrived?Atherosclerosis. (2020) 300:1–9. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2020.03.003

23.

Harb T Ziogos E Blumenthal RS Gerstenblith G Leucker TM . Intra-individual variability in lipoprotein(a): the value of a repeat measure for reclassifying individuals at intermediate risk. Eur Heart J Open. (2024) 4(5):oeae064. 10.1093/ehjopen/oeae064

24.

NICE. Cardiovascular Disease: Risk Assessment and Reduction, Including Lipid Modification (2023). Available online at:www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng238 (Accessed August 22, 2025).

25.

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing (2021). Available online at:https://www.R-project.org/ (Accessed February 22, 2024)

26.

NICE. CVD risk Assessment and Management: Scenario: Management of People with an Estimated Risk of 10% or More (2025). Available online at:https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/cvd-risk-assessment-management/management/cvd-risk-10percent-or-more/ (Accessed August 22, 2025)

27.

Lp(a) Taskforce. A Call to Action from the Lipoprotein(a) Taskforce (2023). https://www.heartuk.org.uk/downloads/health-professionals/a-call-to-action-from-the-lipoprotein(a)-taskforce---august-2023.pdf (Accessed 18 June 2025).

28.

Kronenberg F Bedlington N Ademi Z Geantă M Silberzahn T Rijken M et al The Brussels international declaration on lipoprotein(a) testing and management. Atherosclerosis. (2025) 406:119221. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2025.119218

29.

Verbeek R Sandhu MS Hovingh GK Sjouke B Wareham NJ Zwinderman AH et al Lipoprotein(a) improves cardiovascular risk prediction based on established risk algorithms. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2017) 69:1513–5. Elsevier USA. 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.01.017

30.

Trinder M Uddin MM Finneran P Aragam KG Natarajan P . Clinical utility of lipoprotein(a) and LPA genetic risk score in risk prediction of incident atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. JAMA Cardiol. (2021) 6(3):287–95. 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.5398

31.

Bhatia HS Ambrosio M Razavi AC Alebna PL Yeang C Spitz JA et al AHA PREVENT equations and lipoprotein(a) for cardiovascular disease risk: insights from MESA and the UK biobank. JAMA Cardiol. (2025) 10:810–8. 10.1001/jamacardio.2025.1603

32.

Willeit P Kiechl S Kronenberg F Witztum JL Santer P Mayr M et al Discrimination and net reclassification of cardiovascular risk with lipoprotein(a) prospective 15-year outcomes in the bruneck study. JACC. (2014) 64:851–60. 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.03.061

33.

Ghavami M Abdshah A Esteghamati S Hafezi-Nejad N Nakhjavani M Esteghamati A . Serum lipoprotein(a) and reclassification of coronary heart disease risk; application of prediction in a cross-sectional analysis of an ongoing Iranian cohort. BMC Public Health. (2023) 23(1):2402. 10.1186/s12889-023-17332-w

34.

Ansari S Cegla J . Lipoprotein(a) measurement—how, why and in whom?Br J Cardiol. (2024) 31:S10–5. 10.5837/bjc.2024.s03

35.

Vogt A . Lipoprotein(a)-apheresis in the light of new drug developments. Atheroscler Suppl. (2017) 30:38–43. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosissup.2017.05.025

36.

Safarova MS Moriarty PM . Lipoprotein apheresis: current recommendations for treating familial hypercholesterolemia and elevated lipoprotein(a). Curr Atheroscler Rep. (2023) 25(7):391–404. 10.1007/s11883-023-01113-2

37.

Reyes-Soffer G Yeang C Michos ED Boatwright W Ballantyne CM . High lipoprotein(a): actionable strategies for risk assessment and mitigation. Am J Prev Cardiol. (2024) 18:100651. Elsevier B.V. 10.1016/j.ajpc.2024.100651

38.

Katsiki N Vrablik M Banach M Gouni-Berthold I . Lp(a)-lowering agents in development: a new era in tackling the burden of cardiovascular risk?Pharmaceuticals. (2025) 18:753. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI). 10.3390/ph18050753

39.

Cho L Nicholls SJ Nordestgaard BG Landmesser U Tsimikas S Blaha MJ et al Design and rationale of Lp(a)HORIZON trial: assessing the effect of lipoprotein(a) lowering with pelacarsen on major cardiovascular events in patients with CVD and elevated Lp(a). Am Heart J. (2025) 287:1–9. 10.1016/j.ahj.2025.03.019

40.

Tsimikas S Karwatowska-Prokopczuk E Gouni-Berthold I Tardif JC Baum SJ Steinhagen-Thiessen E et al Lipoprotein(a) reduction in persons with cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. (2020) 382(3):244–55. 10.1056/NEJMoa1905239

41.

O’Donoghue ML Rosenson RS Gencer B López JAG Lepor NE Baum SJ et al Small interfering RNA to reduce lipoprotein(a) in cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. (2022) 387(20):1855–64. 10.1056/NEJMoa2211023

42.

Nissen SE Ni W Shen X Wang Q Navar AM Nicholls SJ et al Lepodisiran — a long-duration small interfering RNA targeting lipoprotein(a). N Engl J Med. (2025) 392(17):1673–83. 10.1056/NEJMoa2415818

Summary

Keywords

atherosclerosis, cardiovascular disease, Lipoprotein(a), Lp(a), risk assessment, screening, stroke, QRISK3

Citation

Irvine A, Watt J, Kurth MJ, Mooney L, Clark-McKellar J, Keteepe-Arachi T, Lamont JV, Dowey LR, Fitzgerald P and Ruddock MW (2026) Lipoprotein(a): the neglected risk factor in cardiovascular health. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 12:1710557. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1710557

Received

22 September 2025

Revised

02 December 2025

Accepted

09 December 2025

Published

09 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Menno Hoekstra, Leiden University, Netherlands

Reviewed by

Loni Berkowitz, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Chile

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Irvine, Watt, Kurth, Mooney, Clark-McKellar, Keteepe-Arachi, Lamont, Dowey, Fitzgerald and Ruddock.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Mark W. Ruddock mark.ruddock@randox.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.