Abstract

Cardiorenal syndrome (CRS) refers to the pathophysiological interaction between cardiac dysfunction and kidney injury. Traditional CRS research has focused primarily on the impact of left heart failure on renal function. However, increasing evidence suggests that abnormalities in right heart function, particularly tricuspid regurgitation (TR), critically exacerbate the progression of CRS by promoting renal venous congestion, worsening kidney function, and further aggravating right heart failure. With the aging population and prolonged survival of patients with heart failure, the prevalence of TR has significantly increased and has a substantial impact on prognosis. Therefore, there is an urgent need to reassess the role of TR in heart–kidney interactions. This review summarizes the pathophysiology, clinical evidence, and treatment strategies of TR in the context of CRS, with the aim of raising awareness of the right-heart-centered perspective. Kidney injury caused by right heart dysfunction is driven by multiple mechanisms, among which elevated right atrial pressure and consequent renal venous congestion appear to be more important than reduced renal perfusion caused by low cardiac output alone. In patients with moderate or severe TR, renal function deteriorates significantly, whereas interventional treatment that reduces TR can improve right heart function and lower the risk of adverse events. Future research should challenge the traditional left-heart-dominant paradigm, focusing on mechanistic studies, early assessment and risk stratification, interventional therapy, and the synergistic effects of new drug combinations. Addressing current limitations and research gaps is crucial to overcoming therapeutic bottlenecks and improving long-term outcomes in patients with chronic cardiorenal syndrome.

1 Introduction

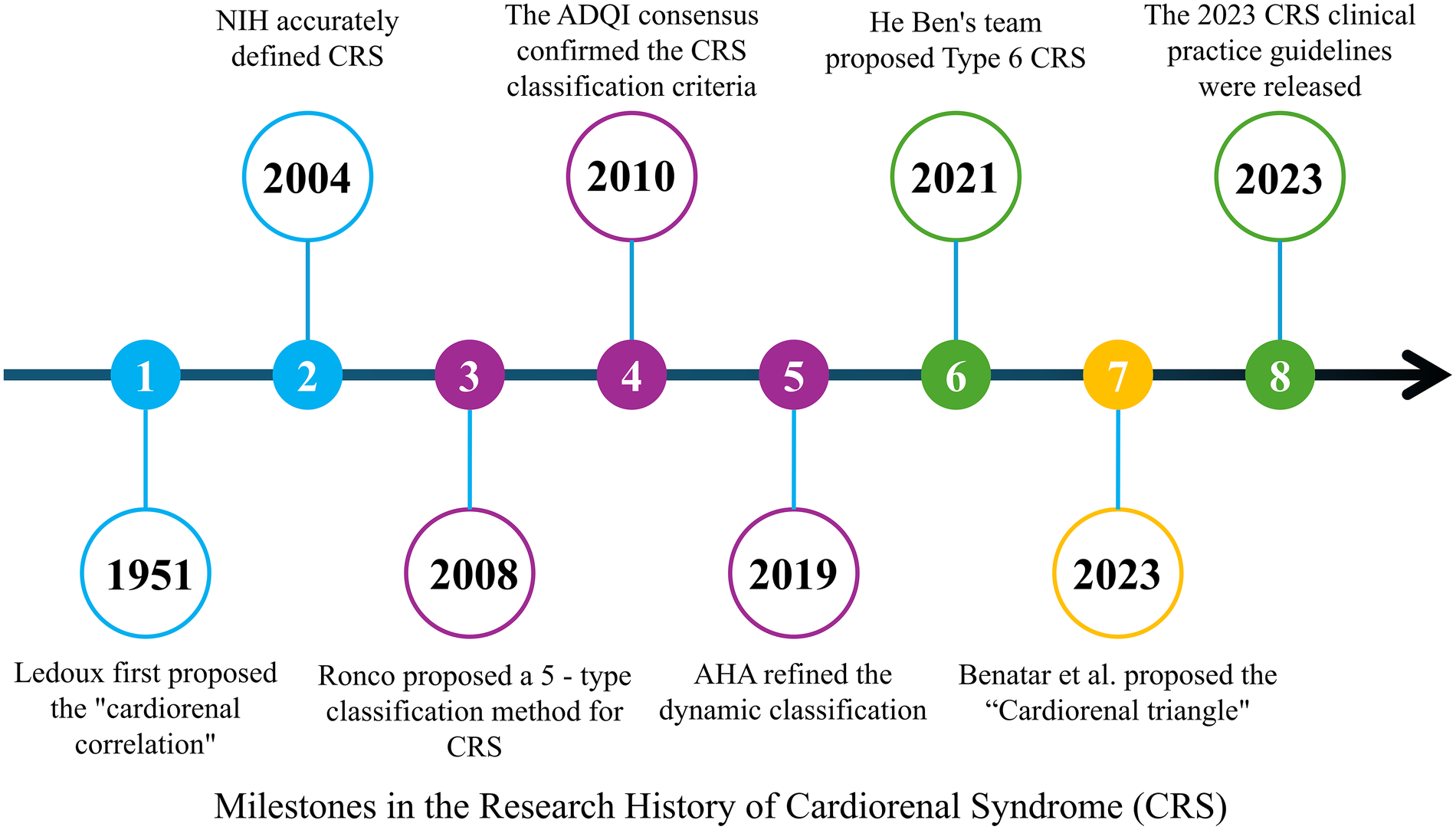

The concept of heart–kidney interaction can be traced back to clinical observations by Ledoux in 1951, which described the mutual influence between cardiac and renal dysfunction (1). In 2004, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) formally defined this bidirectional interaction as cardiorenal syndrome (CRS) (2). Although He Ben and colleagues later proposed a chronic secondary form of CRS (CRS type 6) (3), the five-type classification system proposed by Ronco et al. in 2008 remains widely used in clinical practice. This system categorizes CRS into five types based on pathogenesis and temporal characteristics, with the most common forms being kidney dysfunction caused by acute or chronic heart failure (CRS types 1 and 2) (Figure 1) (4–6).

Figure 1

Milestones in the research history of cardiorenal syndrome (CRS). A timeline summarizing key milestones in CRS research, from Ledoux's initial proposal of the “cardiorenal correlation” in 1951, to the NIH definition of CRS in 2004, the five-type classification by Ronco et al. in 2008, the dynamic refinement by the AHA in 2019, the proposal of CRS type 6 by He Ben in 2021, and the publication of the 2023 clinical practice guidelines for CRS.

Traditional CRS research has primarily focused on left ventricular (LV) dysfunction and reduced cardiac output. However, existing evidence suggests that left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) does not clearly correlate with estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) (7). In contrast, right heart dysfunction has long been under-recognized in the CRS paradigm. Tricuspid regurgitation, often regarded as a secondary manifestation of right heart failure, has frequently been considered to have limited independent clinical significance.

Benatar and colleagues recently introduced the concept of a “TR–right ventricular function–renal congestion” cardiorenal triangle, describing how TR leads to right ventricular (RV) dysfunction and venous congestion, which in turn results in renal dysfunction (8). Emerging data suggest that TR is not only a hallmark of right heart failure but may also act as a major driving factor in heart–kidney dysfunction. The strong association between TR and adverse outcomes in CRS has become increasingly evident as the prevalence of TR rises with population aging and improved survival in heart failure (9, 10). This poses a significant threat to public health.

Therefore, it is imperative to reassess the role of TR in heart–kidney interactions and to recognize the critical contribution of right heart function—particularly TR—to chronic cardiorenal syndrome (Table 1).

Table 1

| Type | Name | Pathophysiology | Typical clinical manifestations | Common triggers/underlying causes | Treatment strategies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRS-1 | Acute Cardiorenal Syndrome | Acute heart failure leading to renal hypoperfusion, causing AKI | Oliguria, increased blood creatinine 24–72 h post-acute heart failure or myocardial infarction | Acute myocardial infarction, decompensated heart failure | Optimize cardiac output; Diuretics; RRT if necessary |

| CRS-2 | Chronic Cardiorenal Syndrome | Chronic heart failure leading to long-term low perfusion, accelerating CKD progression | Progressive eGFR decline ≥3 months, proteinuria | Dilated cardiomyopathy, etc. | RAAS inhibitors, Beta-blockers, Volume management |

| CRS-3 | Acute Renal-Heart Syndrome | AKI causing volume overload, leading to acute myocardial injury/arrhythmia | Acute pulmonary edema, ventricular arrhythmias after AKI | Ischemic AKI, etc. | Remove renal injury triggers; Volume control; Dialysis support |

| CRS-4 | Chronic Renal-Heart Syndrome | CKD causing uremic toxins that accelerate cardiovascular remodeling | CKD patients with left ventricular hypertrophy | Diabetic nephropathy, etc. | Antihypertensive treatment, Anemia correction, Calcium-phosphate metabolism regulation, Cardiovascular protection |

| CRS-5 | Acute Secondary Cardiorenal Syndrome | Systemic diseases triggering inflammatory storms leading to concurrent heart and kidney dysfunction | Multiple organ failure | Sepsis, SLE, etc. | Control primary disease; Organ support |

Based on ronco et al.'s five-type CRS classification.

2 Pathophysiological mechanisms of heart-kidney interaction from the right heart perspective

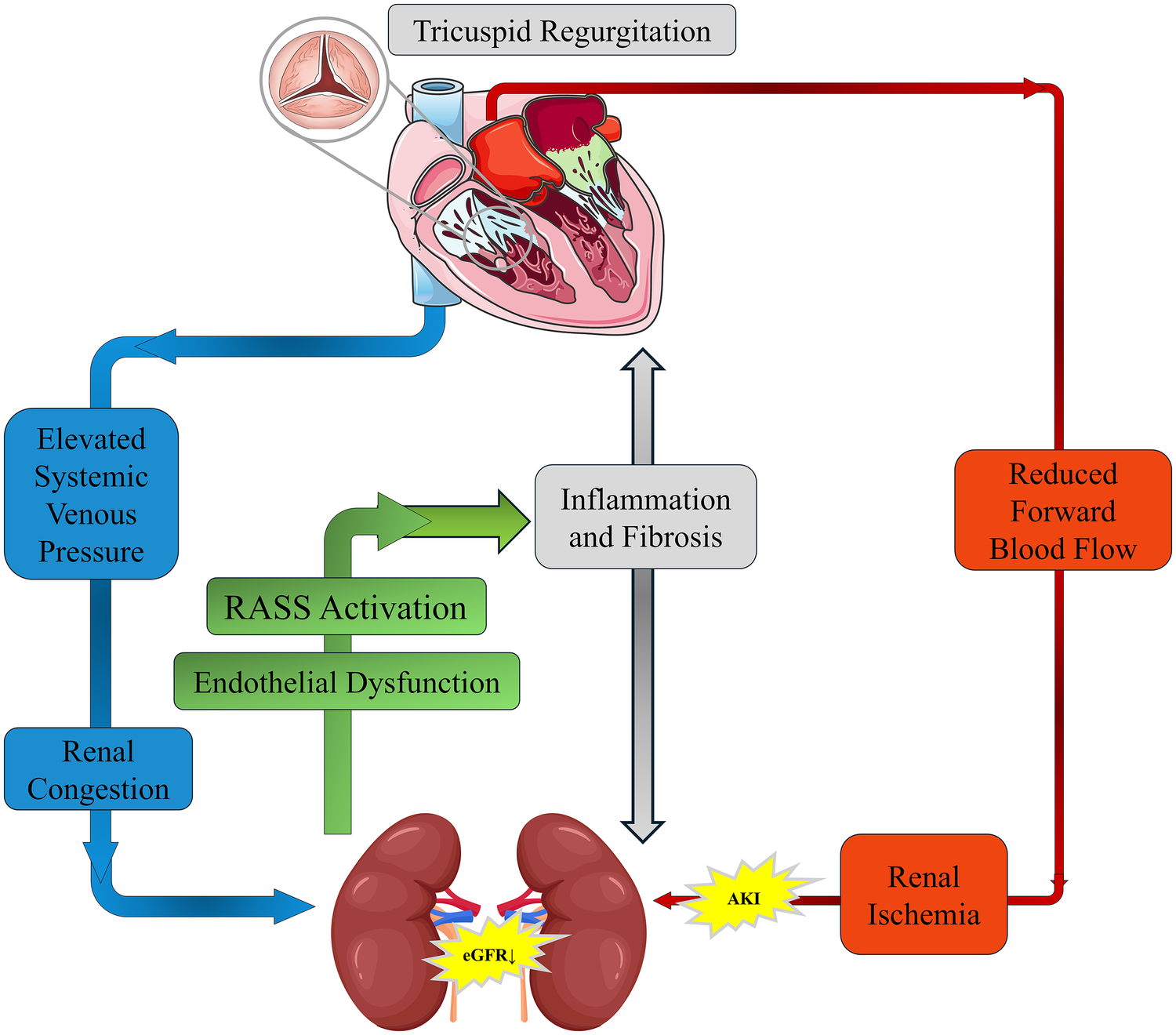

From the right heart perspective, kidney injury in chronic heart failure is driven by multiple interrelated mechanisms, with hemodynamic remodeling as the initiating event. In contrast to the traditional left-heart-centered view, elevated right atrial pressure and renal venous congestion (“backward failure”) appear to be more crucial than reduced renal perfusion pressure due to low cardiac output (“forward failure”).

Clinical studies have demonstrated that LVEF does not have a direct correlation with eGFR (7). Data from the ESCAPE trial confirmed that increased renal interstitial hydrostatic pressure can compress peritubular capillaries, directly damaging renal parenchyma and impairing filtration (11). Persistent elevation of central venous pressure (CVP) thus contributes significantly to renal dysfunction.

Right ventricular volume overload leads to leftward displacement of the interventricular septum, limiting LV diastolic filling and further lowering cardiac output. This creates a vicious cycle of “low cardiac output–high venous pressure,” exacerbating systemic tissue hypoperfusion and pre-renal injury. Clinically, this is manifested as diuretic resistance and abnormal redistribution of cortical–medullary blood flow (7).

At the neurohormonal and inflammatory level, renal congestion triggers activation of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS). Angiotensin II maintains compensatory GFR by constricting efferent arterioles but at the cost of glomerular hyperfiltration damage. Along with aldosterone, angiotensin II promotes cardiac and renal fibrosis through TGF-β–mediated pathways. Venous congestion also induces endothelial dysfunction (eNOS uncoupling with reduced NO and increased ROS) and systemic inflammatory responses (12), accelerating cardiomyocyte and renal tubular cell apoptosis as well as epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) via the NF-κB pathway.

Anemia and dysregulation of the erythropoietin (EPO) axis further contribute to metabolic decompensation. Right-heart-associated hepatic congestion upregulates hepcidin, leading to functional iron deficiency (13). Chronic inflammation blunts EPO receptor sensitivity, diminishing the dual protective effects of the PI3 K/Akt pathway in suppressing apoptosis and fibrosis in both cardiac and renal tissues (14, 15). Altogether, these processes form a “congestion–fibrosis–metabolic imbalance” closed-loop progression model (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Pathophysiological mechanisms of tricuspid regurgitation (TR) in cardiorenal syndrome (CRS). Schematic representation of how TR exacerbates CRS by increasing systemic venous pressure and causing renal congestion, leading to RAAS activation, inflammation, and fibrosis. Concurrently, reduced forward blood flow results in renal ischemia and AKI. These mechanisms interact to create a vicious cycle that progressively impairs both cardiac and renal function.

3 Clinical evidence of TR-related cardiorenal syndrome

3.1 Relationship between tricuspid regurgitation and right heart function

Tricuspid regurgitation is both an important clinical manifestation and a marker of right heart dysfunction. Most TR is functional or secondary, with pathophysiological mechanisms primarily linked to RV dysfunction and right atrial (RA) dilation. Right ventricular dysfunction leads to RV dilation and geometric distortion, stretching the tricuspid annulus and impairing coaptation of the valve leaflets. Right atrial enlargement further exacerbates TR severity, perpetuating a vicious cycle (16).

TR, in turn, worsens right heart dysfunction. The more severe the TR, the higher the risk of RV failure and poor prognosis. In an echocardiographic study by Towheed et al. (17), TR significantly impacted postoperative outcomes following left-sided valvular surgery by worsening RV dysfunction. The incidence of RV dysfunction in patients with TR was noticeably higher than in those without TR (28.7% vs. 18.4%, P < 0.05), and the postoperative incidence of heart failure was also higher (15.6% vs. 6.2%, P < 0.05). Moreover, the 30-day mortality rate in patients with moderate-to-severe TR was significantly higher compared to patients with mild or no TR (25.3% vs. 10.2% and 3.8%, respectively; P < 0.05).

Conversely, reducing TR can improve right heart function and clinical outcomes. Tanaka et al. (18) reported that in patients with RV dysfunction (RVFAC <35%) undergoing transcatheter tricuspid edge-to-edge repair (T-TEER), those with improved RV function (increase in RVFAC) had a significantly lower risk of the composite endpoint of death or heart failure hospitalization within one year (HR 0.35; 95% CI 0.14–0.89; P = 0.028). Patients with smaller baseline RV diameter and greater reduction in TR were more likely to experience improvement in RV function, underscoring the prognostic relevance of effective TR reduction.

3.2 Relationship between tricuspid regurgitation and renal function

TR can also accelerate kidney injury through two main mechanisms: elevated systemic venous pressure and reduced effective forward flow. Elevated systemic venous pressure results from increased right atrial pressure and CVP, leading to retrograde transmission of pressure to the renal veins. This renal venous congestion reduces the net filtration pressure across the glomerular capillaries, thereby decreasing GFR and causing kidney dysfunction. In parallel, reduced cardiac output due to RV dysfunction further compromises renal perfusion.

Historically, insufficient renal perfusion due to elevated CVP has been referred to as “renal congestion,” while renal hypoperfusion related to left heart pump failure is classically termed “cardiorenal syndrome.” However, these mechanisms often coexist and interact in patients with combined right and left heart disease.

A cohort study by Butcher et al. (19) showed that 45% of patients with moderate or severe TR had significant kidney dysfunction (eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2). The presence of RV dysfunction (TAPSE <14 mm) further increased the risk of renal injury (OR 1.49; 95% CI 1.11–1.99; P = 0.008), indicating that TR is independently associated with kidney impairment and that RV–renal coupling is clinically important.

Further analysis demonstrated that renal function parameters in patients with moderate-to-severe TR were significantly worse than in those with mild TR (eGFR 37.2 vs. 45.6 mL/min/1.73 m2, Δ=8.4; P < 0.001; serum urea nitrogen 21.4 vs. 16.8 mg/dL; P < 0.001). These patients also showed RA enlargement (RA volume index >40 mL/m2) and elevated right ventricular systolic pressure (RVSP ≥40 mmHg), reflecting the integrated impact of right-sided hemodynamics on renal function (19).

Chen et al. (20) reported that even when cardiac output was not significantly reduced, elevated CVP independently contributed to the development of acute kidney injury (AKI). For every 1 mmHg increase in CVP, the risk of AKI increased by 9.2% (OR 1.092; 95% CI 1.047–1.138), providing direct evidence for the role of CVP-mediated renal congestion.

In a large retrospective cohort of 11,135 critically ill patients, Sun et al. (21) found that those with CVP >13.2 mmHg (highest quartile) had a 2.1-fold higher risk of AKI compared with those with CVP ≤8.29 mmHg (OR 3.12; 95% CI 2.78–3.50). When CVP ≥15 mmHg, the rate of renal function deterioration accelerated markedly (P < 0.001), suggesting a pathological threshold effect for elevated CVP. Collectively, these studies highlight that the backward pressure effect of TR on the kidney may be more deleterious than forward flow reduction alone.

4 Treatment strategies and approaches from the right heart perspective

Management of CRS has traditionally emphasized pharmacological therapies aimed at reducing cardiac load, improving LV function, and preserving renal function. From a right-heart-centered perspective, however, both the limitations of conventional therapies and the emerging role of TR-targeted interventions must be reconsidered.

4.1 Pharmacological therapies

The mainstay treatments in chronic heart failure include angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitors (ARNIs), β-blockers, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists. Although these agents improve LV remodeling and overall prognosis, their effect on TR and right-sided congestion is often indirect and limited.

Loop diuretics (e.g., furosemide) rapidly relieve systemic congestion by reducing preload, but excessive or chronic use may lead to intravascular volume depletion and prerenal hypoperfusion. This, in turn, can worsen kidney function through RAAS activation and sympathetic overdrive (22). Clinical data indicate that for every 40 mg/day increase in loop diuretic dosage, the annual rate of eGFR decline increases by approximately 1.2 mL/min/1.73 m2 (22). Long-term high-dose diuretic use may also induce electrolyte disturbances (e.g., hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia) and vacuolar degeneration of renal tubular epithelial cells, promoting tubulointerstitial fibrosis (23).

RAAS inhibitors (ACEIs/ARBs, ARNIs) reduce cardiovascular events and mitigate LV remodeling; however, their dose-dependent hypotension and reduction in renal perfusion pressure may accelerate renal function decline in susceptible patients (24). The MERIT-HF trial (25) systematically excluded patients with eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2, resulting in limited evidence regarding the safety and efficacy of β-blockers and other standard heart failure therapies in those with moderate-to-severe chronic kidney disease (CKD). In real-world practice, approximately one-third of patients with CRS type 2 must reduce or discontinue disease-modifying drugs because of hypotension, hyperkalemia, or worsening renal function, creating a “therapeutic ceiling” (26).

Newer agents such as sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) and soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) stimulators have been shown to delay renal function decline and improve outcomes in chronic heart failure (27). However, their direct impact on TR severity and right-sided venous congestion remains to be clarified, and TR-specific pharmacotherapy is still lacking.

4.2 Interventional and surgical therapies

The indications for surgical tricuspid valve repair or replacement have traditionally been narrow, and perioperative risk is high, particularly in patients with advanced RV dysfunction, severe pulmonary hypertension, or multiple comorbidities. As a result, many patients with significant TR are referred late or not considered for surgery.

With the advent of transcatheter techniques, interventional treatment for TR has become an important therapeutic option. Transcatheter tricuspid valve repair or replacement, including edge-to-edge repair systems such as TriClip, has shown promising results in reducing TR severity and improving functional status in high-risk patients (28). Early data suggest that effective reduction in TR may translate into improved right heart function, relief of venous congestion, and potentially better renal outcomes, although long-term data in CRS populations are still limited.

Surgical repair or replacement remains an effective option for selected patients with severe TR, particularly when performed early, before irreversible RV remodeling and organ dysfunction occur. Early surgery can reverse right heart dysfunction and improve survival, especially in patients undergoing concomitant left-sided valve surgery (29, 30). The challenge lies in refining patient selection, timing, and perioperative management to optimize outcomes.

5 Future perspectives

5.1 Early assessment of right heart function

Early assessment of right heart function requires integration of multimodality imaging and circulating biomarkers. In echocardiography, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE; <1.6 cm indicating poor prognosis) and the right ventricular–pulmonary artery coupling ratio [TAPSE/systolic pulmonary artery pressure (SPAP)] are key parameters for monitoring RV systolic function (31–33). Three-dimensional echocardiography can more accurately characterize tricuspid valve morphology and mechanisms of functional TR, offering advantages over two-dimensional imaging for preprocedural planning (34).

Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR), as the gold standard for right heart volumetric assessment, can quantify RV size, function, and remodeling, and is particularly useful in patients with severe TR or complex congenital anatomy (35–37).

In terms of biomarkers, CA-125 can independently predict venous congestion (38), while bioactive adrenomedullin (bioADM) reflects congestion and biventricular filling pressures (39). Soluble ST2 (sST2) is associated with myocardial fibrosis and remodeling (40), and urinary albumin excretion may reflect the severity of renal congestion. Novel AKI biomarkers such as TIMP-2×IGFBP7, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL), and cystatin C can further refine multi-organ function assessment and provide early warning signals of kidney injury in CRS (41, 42).

5.2 Multi-angle, multi-indicator clinical trial research

Clinical studies have shown that RV functional parameters and pulmonary hemodynamics are strong predictors of postoperative outcomes. Masiero et al. reported that for every 10 mmHg increase in pulmonary artery pressure or every 5 mm decrease in TAPSE, the risk of mortality after mitral valve transcatheter edge-to-edge repair increased by 17% and 18%, respectively (43). A meta-analysis including 8,672 patients found that pulmonary hypertension (HR = 1.70) and TR significantly increased mortality risk after transcatheter mitral valve repair; each 10 mmHg increase in systolic pulmonary artery pressure was associated with a 17% increase in relative risk (44).

These findings underscore the importance of dynamic preoperative monitoring of right heart function (e.g., TAPSE, RV–pulmonary artery coupling, pulmonary pressures) for risk stratification. Future clinical trials should incorporate multi-angle and multi-indicator assessment of right heart function, including TR severity, RV mechanics, venous congestion markers, and renal outcomes, to better define optimal therapeutic strategies.

5.3 Therapeutic innovation and personalized strategies

Pharmacological treatment currently focuses on diuretics to relieve congestion. Vasodilators such as phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors may benefit patients with pulmonary hypertension and RV dysfunction (29). However, TR-specific pharmacologic agents remain an unmet need.

In the interventional field, transcatheter tricuspid edge-to-edge repair (TEER) significantly reduces TR severity and has been associated with lower mortality and fewer heart failure hospitalizations in high-risk populations (30, 45). Patients achieving TR ≤1 + after TEER tend to have better outcomes, suggesting that the degree of TR reduction is clinically meaningful. Ongoing research aims to refine device technology, procedural techniques, and patient selection criteria.

Surgical treatment (tricuspid valve repair or replacement) continues to play an important role, especially when performed earlier in the disease course. Future efforts should focus on integrating surgical and transcatheter strategies, optimizing the timing of referral, and combining structural interventions with guideline-directed medical therapy and CRS-specific care pathways.

5.4 Current limitations and research gaps

Despite increasing recognition of the right-heart-centered perspective in CRS, several important limitations and knowledge gaps remain:

5.4.1 Lack of randomized controlled trials (RCTs)

Most evidence linking TR, RV dysfunction, and renal outcomes comes from observational studies, registries, or post hoc analyses. High-quality RCTs specifically evaluating TR-targeted therapies in CRS populations are scarce.

5.4.2 Heterogeneous assessment of TR and RV function

Definitions of TR severity, imaging protocols, and cutoffs (e.g., for TAPSE or RVFAC) vary across studies, limiting comparability and generalizability. Standardized, guideline-based assessment is needed.

5.4.3 Limited long-term data on transcatheter TR interventions

While early results of TEER and transcatheter replacement are promising, long-term effects on survival, renal function, and hospitalization rates in CRS patients are not yet well established.

5.4.4 Incomplete mechanistic understanding

The precise pathways linking renal venous congestion to tubulointerstitial fibrosis, metabolic dysregulation, and progression from AKI to CKD in CRS remain incompletely understood, particularly in the presence of chronic systemic inflammation.

5.4.5 Lack of right-heart-specific biomarkers

Although several biomarkers reflect congestion or fibrosis, few are specific to right-sided hemodynamics or RV–renal interaction. Development and validation of such biomarkers could significantly enhance risk stratification and treatment guidance.

5.4.6 Optimal timing of TR intervention is unclear

It remains uncertain at which stage of RV remodeling, pulmonary hypertension, or renal impairment TR intervention provides maximal benefit with acceptable risk. Prospective studies focusing on timing thresholds are needed.

Addressing these gaps will be essential to move from descriptive associations toward precise, mechanism-based, and individualized therapeutic strategies in chronic cardiorenal syndrome.

Statements

Author contributions

XY: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LT: Writing – original draft. JL: Writing – review & editing. YZ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. The author(s) verify and take full responsibility for the use of generative AI in the preparation of this manuscript. Generative AI was used exclusively for language editing and refinement. All AI-generated content was thoroughly reviewed and approved by the authors to ensure accuracy and clarity.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Sun Z Luo Y Wang X Chang T Chang M Cui Y et al Association between tricuspid regurgitation and heart failure outcomes: a meta-analysis. ESC Heart Fail. (2025) 12(4):2643–51. 10.1002/ehf2.15303

2.

Bongartz LG Cramer MJ Doevendans PA Joles JA Braam B . The severe cardiorenal syndrome:‘Guyton revisited’. Eur Heart J. (2005) 26(1):11–7. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi020

3.

Zhang Y Jiang Y Yang W Shen L He B . Chronic secondary cardiorenal syndrome: the sixth innovative subtype. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2021) 8:639959. 10.3389/fcvm.2021.639959

4.

Xi R Mumtaz MA Xu D Zeng Q . Tricuspid regurgitation complicating heart failure: a novel clinical entity. Rev Cardiovasc Med. (2024) 25(9):330. 10.31083/j.rcm2509330

5.

Holgado JL Lopez C Fernandez A Sauri I Uso R Trillo JL et al Acute kidney injury in heart failure: a population study. ESC Heart Failure. (2020) 7(2):415–22. 10.1002/ehf2.12595

6.

Felbel D von Winkler J Paukovitsch M Gröger M Walther E Andreß S et al Effective tricuspid regurgitation reduction is associated with renal improvement and reduced heart failure hospitalization. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2024) 11:1452446. 10.3389/fcvm.2024.1452446

7.

Welle GA Hahn RT Lindenfeld J Lin G Nkomo VT Hausleiter J et al New approaches to assessment and management of tricuspid regurgitation before intervention. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. (2024) 17(7):837–58. 10.1016/j.jcin.2024.02.034

8.

Forado-Benatar I Caravaca-Pérez P Rodriguez-Espinosa D Guzman-Bofarull J Cuadrado-Payán E Moayedi Y et al Tricuspid regurgitation, right ventricular function, and renal congestion: a cardiorenal triangle. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2023) 10:1255503. 10.3389/fcvm.2023.1255503

9.

Kobayashi T Matsue Y Fujimoto Y Maeda D Kagiyama N Kitai T et al The prevalence and impact of changes in the severity of secondary TR during hospitalization in acute heart failure. Eur Heart J. (2024) 45(Suppl_1):ehae666. 1938. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehae666.1938

10.

Wang N Fulcher J Abeysuriya N McGrady M Wilcox I Celermajer D et al Tricuspid regurgitation is associated with increased mortality independent of pulmonary pressures and right heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. (2019) 40(5):476–84. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy641

11.

Nohria A Hasselblad V Stebbins A Pauly DF Fonarow GC Shah M et al Cardiorenal interactions: insights from the ESCAPE trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2008) 51(13):1268–74. 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.08.072

12.

Fu P Arcasoy MO . Erythropoietin protects cardiac myocytes against anthracycline-induced apoptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. (2007) 354(2):372–8. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.01.044

13.

Jie KE Verhaar MC Cramer M-JM Van Der Putten K Gaillard CA Doevendans PA et al Erythropoietin and the cardiorenal syndrome: cellular mechanisms on the cardiorenal connectors. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. (2006) 291(5):F932–F44. 10.1152/ajprenal.00200.2006

14.

Riksen NP Hausenloy DJ Yellon DM . Erythropoietin: ready for prime-time cardioprotection. Trends Pharmacol Sci. (2008) 29(5):258–67. 10.1016/j.tips.2008.02.002

15.

Palazzuoli A Silverberg DS Iovine F Calabrò A Campagna MS Gallotta M et al Effects of β-erythropoietin treatment on left ventricular remodeling, systolic function, and B-type natriuretic peptide levels in patients with the cardiorenal anemia syndrome. Am Heart J. (2007) 154(4):645. e9–. e15. 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.07.022

16.

Sugimoto T Okada M Ozaki N Kawahira T Fukuoka M . Influence of functional tricuspid regurgitation on right ventricular function. Ann Thorac Surg. (1998) 66(6):2044–50. 10.1016/S0003-4975(98)01041-8

17.

Towheed A Sabbagh E Gupta R Assiri S Chowdhury MA Moukarbel GV et al Right ventricular dysfunction and short-term outcomes following left-sided valvular surgery: an echocardiographic study. J Am Heart Assoc. (2021) 10(4):e016283. 10.1161/JAHA.120.016283

18.

Tanaka T Sugiura A Kavsur R Öztürk C Wilde N Zimmer S et al Changes in right ventricular function and clinical outcomes following tricuspid transcatheter edge-to-edge repair. Eur J Heart Fail. (2024) 26(4):1015–24. 10.1002/ejhf.3183

19.

Butcher SC Fortuni F Dietz MF Prihadi EA van Der Bijl P Ajmone Marsan N et al Renal function in patients with significant tricuspid regurgitation: pathophysiological mechanisms and prognostic implications. J Intern Med. (2021) 290(3):715–27. 10.1111/joim.13312

20.

Chen X Wang X Honore PM Spapen HD Liu D . Renal failure in critically ill patients, beware of applying (central venous) pressure on the kidney. Ann Intensive Care. (2018) 8:1–7. 10.1186/s13613-018-0439-x

21.

Sun R Guo Q Wang J Zou Y Chen Z Wang J et al Central venous pressure and acute kidney injury in critically ill patients with multiple comorbidities: a large retrospective cohort study. BMC Nephrol. (2022) 23(1):83. 10.1186/s12882-022-02715-9

22.

Butler J Forman DE Abraham WT Gottlieb SS Loh E Massie BM et al Relationship between heart failure treatment and development of worsening renal function among hospitalized patients. Am Heart J. (2004) 147(2):331–8. 10.1016/j.ahj.2003.08.012

23.

Liang KV Williams AW Greene EL Redfield MM . Acute decompensated heart failure and the cardiorenal syndrome. Crit Care Med. (2008) 36(1):S75–88. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000296270.41256.5C

24.

Sampath-Kumar R Rück A Manouras A Ben-Yehuda O Lund LH Shahim B . Evaluation and management principles for chronic right heart failure and tricuspid regurgitation. Curr Heart Fail Rep. (2025) 22(1):32. 10.1007/s11897-025-00720-1

25.

Hjalmarson Å Goldstein S Fagerberg B Wedel H Waagstein F Kjekshus J et al Effects of controlled-release metoprolol on total mortality, hospitalizations, and well-being in patients with heart failure: the metoprolol CR/XL randomized intervention trial in congestive heart failure (MERIT-HF). JAMA. (2000) 283(10):1295–302. 10.1001/jama.283.10.1295

26.

De Vecchis R Baldi C . Cardiorenal syndrome type 2: from diagnosis to optimal management. Ther Clin Risk Manag. (2014) 2014:949–61. 10.2147/TCRM.S63255

27.

Solomon SD McMurray JJ Claggett B de Boer RA DeMets D Hernandez AF et al Dapagliflozin in heart failure with mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. (2022) 387(12):1089–98. 10.1056/NEJMoa2206286

28.

Mahboob E Samad MA Carver C Chaudhry SAA Fatima T Abid M et al Triclip G4: a game-changer for tricuspid valve regurgitation treatment. Curr Probl Cardiol. (2024) 49:102687. 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2024.102687

29.

Schwartz LA Rozenbaum Z Ghantous E Kramarz J Biner S Ghermezi M et al Impact of right ventricular dysfunction and tricuspid regurgitation on outcomes in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. (2017) 30(1):36–46. 10.1016/j.echo.2016.08.016

30.

Besler C Unterhuber M Rommel KP Unger E Hartung P von Roeder M et al Nutritional status in tricuspid regurgitation: implications of transcatheter repair. Eur J Heart Fail. (2020) 22(10):1826–36. 10.1002/ejhf.1752

31.

Rudski LG Lai WW Afilalo J Hua L Handschumacher MD Chandrasekaran K et al Guidelines for the echocardiographic assessment of the right heart in adults: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography: endorsed by the European Association of Echocardiography, a registered branch of the European Society of Cardiology, and the Canadian Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. (2010) 23(7):685–713. 10.1016/j.echo.2010.05.010

32.

L'Official G Vely M Kosmala W Galli E Guerin A Chen E et al Isolated functional tricuspid regurgitation: how to define patients at risk for event? ESC Heart Failure. (2023) 10(3):1605–14. 10.1002/ehf2.14189

33.

Fortuni F Butcher SC Dietz MF van der Bijl P Prihadi EA De Ferrari GM et al Right ventricular–pulmonary arterial coupling in secondary tricuspid regurgitation. Am J Cardiol. (2021) 148:138–45. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2021.02.037

34.

Hahn RT . State-of-the-art review of echocardiographic imaging in the evaluation and treatment of functional tricuspid regurgitation. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. (2016) 9(12):e005332. 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.116.005332

35.

Valsangiacomo Buechel ER Mertens LL . Imaging the right heart: the use of integrated multimodality imaging. Eur Heart J. (2012) 33(8):949–60. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr490

36.

Khalique OK Cavalcante JL Shah D Guta AC Zhan Y Piazza N et al Multimodality imaging of the tricuspid valve and right heart anatomy. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging. (2019) 12(3):516–31. 10.1016/j.jcmg.2019.01.006

37.

Hahn RT Thomas JD Khalique OK Cavalcante JL Praz F Zoghbi WA . Imaging assessment of tricuspid regurgitation severity. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging. (2019) 12(3):469–90. 10.1016/j.jcmg.2018.07.033

38.

Soler M Miñana G Santas E Núñez E de la Espriella R Valero E et al CA125 Outperforms NT-proBNP in acute heart failure with severe tricuspid regurgitation. Int J Cardiol. (2020) 308:54–9. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2020.03.027

39.

Goetze JP Balling L Deis T Struck J Bergmann A Gustafsson F . Bioactive adrenomedullin in plasma is associated with biventricular filling pressures in patients with advanced heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. (2021) 23(3):489–91. 10.1002/ejhf.1937

40.

Defilippi C Daniels LB Bayes-Genis A . Structural heart disease and ST2: cross-sectional and longitudinal associations with echocardiography. Am J Cardiol. (2015) 115(7):59B–63B. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.01.042

41.

Tasić D Radenkovic S Stojanovic D Milojkovic M Stojanovic M Deljanin Ilic M et al Crosstalk of various biomarkers that might provide prompt identification of acute or chronic cardiorenal syndromes. Cardiorenal Med. (2016) 6(2):99–107. 10.1159/000437309

42.

Palazzuoli A Ruocco G Pellegrini M De Gori C Del Castillo G Franci B et al Comparison of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin versus B-type natriuretic peptide and cystatin C to predict early acute kidney injury and outcome in patients with acute heart failure. Am J Cardiol. (2015) 116(1):104–11. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.03.043

43.

Masiero G Arturi F Soramio EB Fovino LN Fabris T Cardaioli F et al Impact of updated invasive right ventricular and pulmonary hemodynamics on long-term outcomes in patients with mitral valve transcatheter edge-to-edge repair. Am J Cardiol. (2025) 234:99–106. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2024.11.010

44.

Meijerink F de Witte SM Limpens J de Winter RJ Bouma BJ Baan J . Prognostic value of pulmonary hypertension, right ventricular function and tricuspid regurgitation on mortality after transcatheter mitral valve repair: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart, Lung and Circulation. (2022) 31(5):696–704. 10.1016/j.hlc.2021.11.017

45.

Doenst T Bonow RO Bhatt DL Falk V Gaudino M . Improving terminology to describe coronary artery procedures: jACC review topic of the week. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2021) 78(2):180–8. 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.05.010

Summary

Keywords

cardiorenal syndrome (CRS), renal venous congestion, right ventricular dysfunction (RV dysfunction), transcatheter tricuspid intervention, tricuspid regurgitation (TR)

Citation

Yin X, Tang L, Liu J and Zhang Y (2026) The right heart perspective in chronic cardiorenal syndrome: the key role of right heart function and tricuspid regurgitation innovation. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 12:1710898. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1710898

Received

22 September 2025

Revised

07 December 2025

Accepted

11 December 2025

Published

12 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Maria Nunes, Federal University of Minas Gerais, Brazil

Reviewed by

Gabriel A. L. Carmo, Federal University of Minas Gerais, Brazil

Canan Akman, Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart University, Türkiye

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Yin, Tang, Liu and Zhang.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Yongheng Zhang mfqq_258383@sohu.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.