Abstract

Introduction:

Telmisartan is a long-acting angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB) with unique pharmacologic properties, including partial PPAR-γ activation. Its comparative effectiveness against other ARBs in real-world populations remains unclear.

Methods:

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using the TriNetX Global Collaborative Network, including hypertensive patients aged 55–85 years without prior stroke, heart failure, or myocardial infarction. After 1:1 propensity score matching, 41,598 patients were included in each group.

Results:

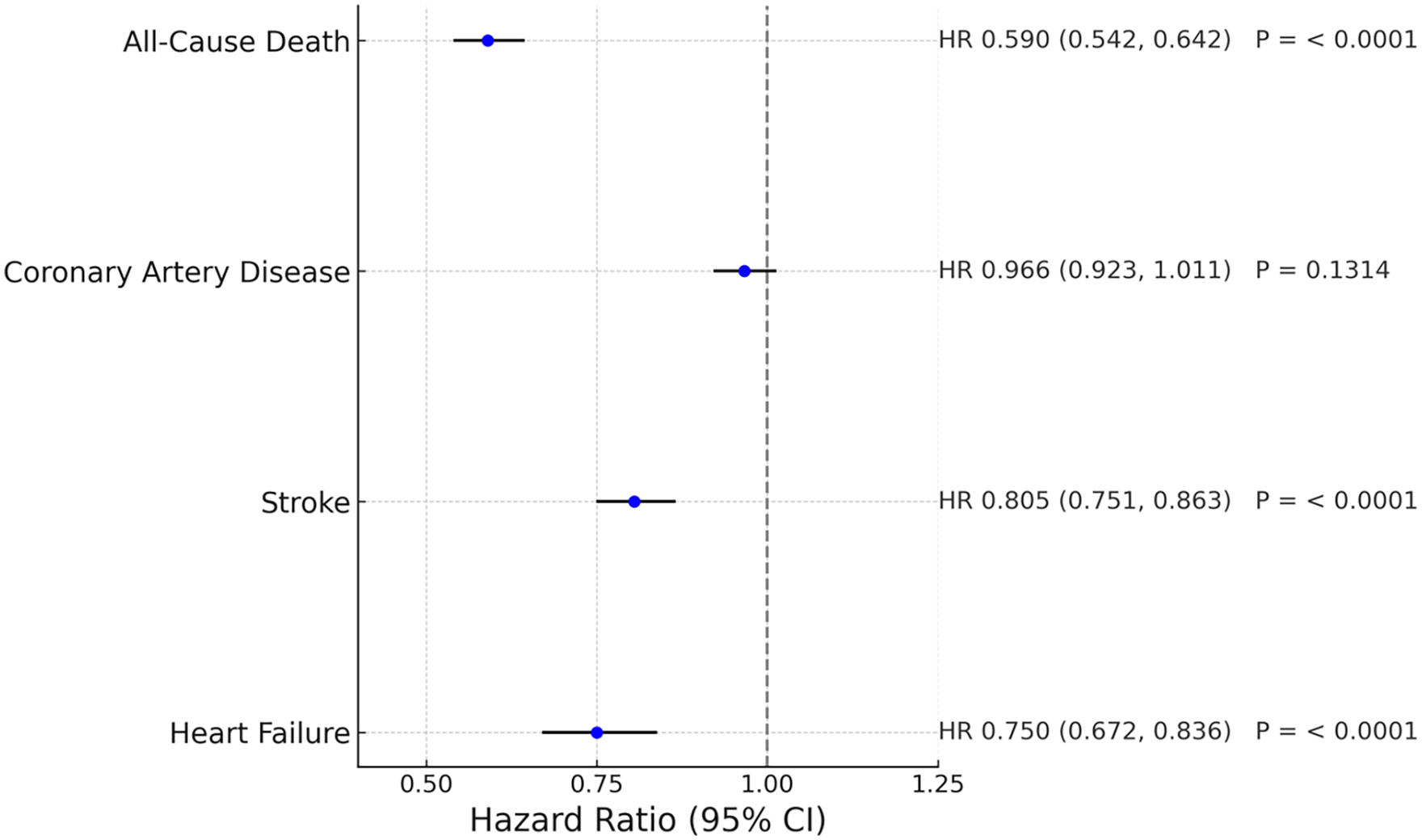

Telmisartan use was associated with a significantly lower risk of stroke (HR 0.805, 95% CI 0.751–0.863), heart failure (HR 0.75, 95% CI 0.672–0.836), and all-cause mortality (HR 0.59, 95% CI 0.542–0.642) compared to other ARBs. Subgroup analyses showed consistent benefits across sex, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and hyperlipidemia.

Conclusions:

In this large real-world matched cohort of over 83,000 patients, telmisartan was associated with superior cardiovascular and cerebrovascular outcomes compared to other ARBs, supporting its potential as a preferred antihypertensive agent in high-risk populations.

Practical applications

This real-world evidence study, involving over 2 million patients, suggests that telmisartan may offer additional protective benefits beyond blood pressure control—particularly in reducing the risk of stroke, heart failure, and all-cause mortality—compared to other commonly used ARBs. Given its long-acting profile and unique anti-inflammatory and metabolic properties, telmisartan may be especially beneficial for patients with hypertension who also have diabetes, chronic kidney disease, or dyslipidemia. These findings have meaningful implications for clinicians, pharmaceutical decision-makers, and public health professionals seeking effective, well-tolerated treatments for high-risk hypertensive populations. By informing drug selection based on long-term cardiovascular outcomes, this research supports the personalized optimization of antihypertensive therapy in routine care.

Introduction

Hypertension is a well-established risk factor for cardiovascular disease and has been consistently linked to increased risks of coronary artery disease, heart failure, stroke, and all-cause mortality in large-scale epidemiological studies (1). The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) further demonstrated that individuals with both hypertension and elevated lipoprotein(a) levels have a significantly greater risk of cardiovascular events compared to those without hypertension (2). A broad range of antihypertensive agents—including calcium channel blockers (3), beta-blockers (4), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) (5)—are routinely employed in clinical practice to reduce hypertension-related cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

Telmisartan is a highly selective angiotensin II type 1 (AT1) receptor blocker approved for the treatment of hypertension (6), either in monotherapy or in combination with other antihypertensive agents (7, 8). Its long elimination half-life ensures sustained 24-hour blood pressure control, supporting its role as an effective first-line therapy for essential hypertension (9, 10). Clinical trials have demonstrated telmisartan's sustained efficacy, and it is well tolerated across a broad range of patient populations, including the elderly and individuals with comorbid conditions such as type 2 diabetes and renal impairment (11–13). Additionally, telmisartan has been associated with improvements in insulin sensitivity (11, 14, 15), lipid metabolism (16), and may offer potential neuroprotective benefits (17–19).

While several studies have highlighted the potential superiority of telmisartan in reducing hypertension-related cardiovascular events, recent real-world evidence suggests that its cardiovascular outcomes may be comparable to those of other ARBs in hypertensive patients (20), although additional real-world data are warranted to further strengthen claims of its superior cardiovascular benefits. This study aims to evaluate the cardiovascular protective effects of telmisartan relative to other ARBs using real-world evidence.

Methods

Data source

This retrospective cohort study utilized the TriNetX platform, a global federated health research network that provides access to deidentified electronic health records from numerous large healthcare organizations (HCOs). The platform integrates data from both electronic health records and insurance claims into a comprehensive longitudinal dataset. Available information includes patient demographics, diagnoses [coded using the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM)], procedures [using ICD-10 Procedure Coding System (ICD-10-PCS) and Current Procedural Terminology (CPT)], medications (coded via the Veterans Affairs National Formulary), laboratory results [coded using Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes (LOINC)], and healthcare utilization metrics.

The data for this study were obtained on July 12, 2025, from the TriNetX Global Collaborative Network, which is comprised of 147 HCOs and includes records from over 170 million patients. Further methodological details and validation of the platform have been described in prior publications (21, 22).

Ethics statement

All data used in this study were de-identified, thereby exempting the requirement for informed consent. The TriNetX platform complies with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Additionally, this study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of our institution.

Study design

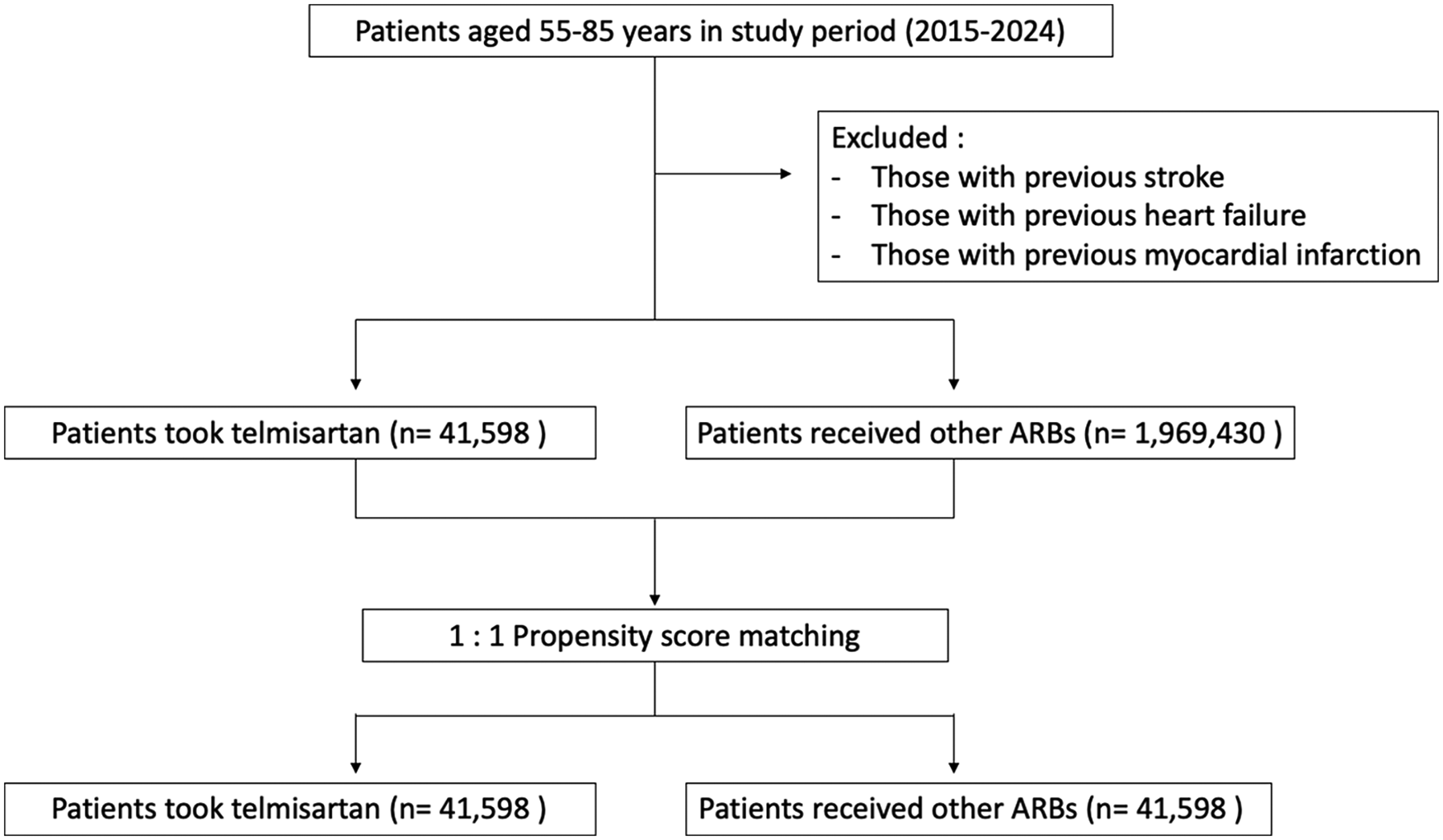

The cohort construction process and patient selection criteria are illustrated in Figure 1. Patients who received telmisartan without exposure to any other ARBs (azilsartan, candesartan, olmesartan, losartan, valsartan, eprosartan, or irbesartan) and had a documented refill of telmisartan after two months of the initial prescription, were assigned to the “telmisartan” cohort. Patients who received losartan without exposure to any other ARBs (azilsartan, candesartan, olmesartan, valsartan, eprosartan, telmisartan or irbesartan), and had a documented refill of losartan after two months of the initial prescription, were assigned to the “losartan” cohort. The “Valsartan” cohort was established accordingly with patients exclusively receiving valsartan and had a documented refill of valsartan after two months of the initial prescription. Those who received ARBs other than telmisartan were classified into the “other ARBs” cohort. The date of the first prescription was defined as the index event. Patients younger than 55 or older than 85 years, as well as those with a prior history of heart failure, stroke, or myocardial infarction, were excluded from the analysis.

Figure 1

Study design and cohort construction.

The primary outcomes of interest were stroke (both ischemic and intracranial hemorrhage, ICD-10-CM: G46, I60 −I63, I65 −I67, I69; ICD-9-CM: 433, 433.0 −433.9, 434, 434.0, 434.1, 434.9), coronary heart disease (ICD-10-CM: I20-I25), heart failure (ICD-10-CM: I50) and all-cause mortality. The observation period began one day after the initial administration of the drug (the index event) and extended up to five years post-administration.

Statistical analysis and data visualization

Propensity score matching (PSM) was performed using the built-in functionality of the TriNetX platform to create 1:1 matched cohorts based on selected covariates. The matching process utilized a greedy nearest-neighbor algorithm with a caliper of 0.1 pooled standard deviations, ensuring a maximum allowable difference in propensity scores of less than 0.1. Matching variables included age at index date, sex (male), and ethnicity (Hispanic or Latino, White, Asian, Black or African American, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, American Indian or Alaska Native). Additional clinical and treatment-related variables included essential hypertension (ICD-10-CM: I10), secondary hypertension (ICD-10-CM: I15), disorders of lipoprotein metabolism and other lipidemias (ICD-10-CM: E78), chronic kidney disease (ICD-10-CM: N18), and baseline use of the following medications: beta-blockers (VA: CV100), calcium channel blockers (VA: CV200), diuretics (VA: CV700), ACE inhibitors (VA: CV800), antiarrhythmics (VA: CV300), antianginals (VA: CV250), oral hypoglycemic agents (VA: HS502), platelet aggregation inhibitors (VA: BL117), warfarin (RxNorm: 11289), and other anticoagulants (VA: BL110).

From the TriNetX Analytics platform, survival analyses were conducted using time-to-event data. Kaplan–Meier (KM) survival curves were constructed to estimate the cumulative incidence of outcomes over time, stratified by treatment cohorts (e.g., telmisartan vs. other ARBs). For visual clarity, KM curves were plotted with time expressed in years (converted from days), and survival probabilities were displayed on the y-axis. The x-axis was limited to 5 years of follow-up, and the y-axis was scaled to highlight differences near the upper survival range (e.g., 0.60–1.00). Forest plots were generated to compare hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for clinical outcomes between cohorts. HRs were derived using Cox proportional hazards models available on the TriNetX platform, with other ARBs serving as the reference group. Forest plots were created without logarithmic scaling, and x-axis limits were adjusted to optimize visibility of the CI ranges. Point estimates were represented by symbols and horizontal lines indicating the 95% CI, with annotations displaying the exact HR and CI values. All plots were produced using Python (v3.10) with the matplotlib and pandas libraries.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 41,598 patients were included in the telmisartan cohort, and 1,969,430 patients were included in the comparator group receiving other angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), following the exclusion of individuals with prior stroke, heart failure, or myocardial infarction (Table 1). Patients in the telmisartan group were more likely to be of Asian ethnicity, whereas a greater proportion of Black or African American individuals were observed in the other ARBs group. Baseline age and sex distribution were comparable between cohorts. Regarding concomitant medications, the telmisartan cohort had a higher prevalence of platelet aggregation inhibitor use, while patients in the other ARBs group more frequently received antiarrhythmics and anticoagulants.

Table 1

| Initial group | Propensity score-matched group | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Telmisartan (n = 41,598) |

Other ARBs (n = 1,969,430) | p value | SMD | Telmisartan (n = 41,598) |

Other ARBs (n = 41,598) | p value | SMD | |||||

| Demographics | ||||||||||||

| Age at baseline (years) | 64.5 ± 8.11 | 64.2 ± 8.25 | < 0.0001 | 0.04 | 64.5 ± 8.11 | 64.5 ± 8.14 | 0.38 | 0.01 | ||||

| Male (%) | 21,297 | 51.20% | 889,491 | 45.17% | < 0.0001 | 0.12 | 21,297 | 51.20% | 21,309 | 51.23% | 0.73 | 0.00 |

| Race (n, %) | ||||||||||||

| White | 17,063 | 41.02% | 1,186,972 | 60.27% | < 0.0001 | 0.39 | 17,063 | 41.02% | 17,098 | 41.10% | 0.81 | 0.00 |

| Asian | 6,448 | 15.50% | 128,078 | 6.50% | < 0.0001 | 0.29 | 6,448 | 15.50% | 6,268 | 15.07% | 0.08 | 0.01 |

| Black or African American | 3,698 | 8.89% | 252,134 | 12.80% | < 0.0001 | 0.13 | 3,698 | 8.89% | 3,687 | 8.86% | 0.89 | 0.00 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 1,736 | 4.17% | 102,852 | 5.22% | < 0.0001 | 0.05 | 1,736 | 4.17% | 1,679 | 4.04% | 0.32 | 0.01 |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 96 | 0.23% | 5,244 | 0.27% | 0.16 | 0.01 | 96 | 0.23% | 103 | 0.25% | 0.62 | 0.00 |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 86 | 0.21% | 7,633 | 0.39% | < 0.0001 | 0.03 | 86 | 0.21% | 87 | 0.21% | 0.94 | 0.00 |

| Diagnosis (n, %) | ||||||||||||

| Disorders of lipoprotein metabolism | 8,515 | 20.47% | 540,197 | 27.43% | < 0.0001 | 0.16 | 8,515 | 20.47% | 8,560 | 20.58% | 0.70 | 0.00 |

| Chronic kidney disease (CKD) | 1,385 | 3.33% | 86,904 | 4.41% | < 0.0001 | 0.06 | 1,385 | 3.33% | 1,297 | 3.12% | 0.08 | 0.01 |

| Medication uses (n, %) | ||||||||||||

| Antilipemic agents | 9,845 | 23.67% | 461,435 | 23.43% | 0.26 | 0.01 | 9,845 | 23.67% | 9,717 | 23.36% | 0.30 | 0.01 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 5,877 | 14.13% | 281,627 | 14.30% | 0.32 | 0.00 | 5,877 | 14.13% | 5,786 | 13.91% | 0.36 | 0.01 |

| Beta blockers | 5,633 | 13.54% | 302,358 | 15.35% | < 0.0001 | 0.05 | 5,633 | 13.54% | 5,536 | 13.31% | 0.32 | 0.01 |

| Oral hypoglycemic agents | 4,764 | 11.45% | 214,089 | 10.87% | < 0.001 | 0.02 | 4,764 | 11.45% | 4,648 | 11.17% | 0.20 | 0.01 |

| Diuretics | 4,743 | 11.40% | 298,284 | 15.15% | < 0.0001 | 0.11 | 4,743 | 11.40% | 4,680 | 11.25% | 0.49 | 0.00 |

| Platelet aggregation inhibitors | 4,229 | 10.17% | 167,048 | 8.48% | < 0.0001 | 0.06 | 4,229 | 10.17% | 4,155 | 9.99% | 0.39 | 0.01 |

| ACE inhibitors | 2,810 | 6.76% | 193,014 | 9.80% | < 0.0001 | 0.11 | 2,810 | 6.76% | 2,600 | 6.25% | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| Antiarrhythmics | 2,693 | 6.47% | 210,636 | 10.70% | < 0.0001 | 0.15 | 2,693 | 6.47% | 2,555 | 6.14% | 0.05 | 0.01 |

| Anticoagulants | 2,275 | 5.47% | 148,904 | 7.56% | < 0.0001 | 0.08 | 2,275 | 5.47% | 2,056 | 4.94% | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| Antianginals | 1,638 | 3.94% | 59,765 | 3.04% | < 0.0001 | 0.05 | 1,638 | 3.94% | 1,560 | 3.75% | 0.16 | 0.01 |

| Warfarin | 175 | 0.42% | 15,767 | 0.80% | < 0.0001 | 0.05 | 175 | 0.42% | 148 | 0.36% | 0.13 | 0.01 |

Baseline characteristics of the study cohort before and after propensity score matching.

ARB, Angiotensin receptor blockers; SMD, standardized mean difference.

After propensity score matching, 41,598 patients were retained in each cohort for the analyses of heart failure and all-cause mortality. For stroke and coronary artery disease (CAD), the final analytic populations were slightly smaller due to differences in data availability and endpoint completeness (Table 2).

Table 2

| Events | Total number for analysis | 5-year cumulative rate (%) | Hazard ratio, 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart failure | ||||

| Other ARBs | 41,598 | 801 (1.926%) | 1.0 | Ref. |

| Telmisartan | 41,598 | 540 (1.298%) | 0.75 (0.672,0.836) | < 0.0001 |

| Stroke | ||||

| Other ARBs | 40,026 | 1,868 (4.667%) | 1.0 | Ref. |

| Telmisartan | 40,219 | 1,383 (3.439%) | 0.805 (0.751,0.863) | < 0.0001 |

| Coronary artery disease | ||||

| Other ARBs | 36,331 | 3,924 (10.801%) | 1.0 | Ref. |

| Telmisartan | 36,376 | 3,529 (9.701%) | 0.966 (0.923,1.011) | 0.1314 |

| All-cause death | ||||

| Other ARBs | 41,538 | 1,529 (3.681%) | 1.0 | Ref. |

| Telmisartan | 41,524 | 810 (1.951%) | 0.59 (0.542,0.642) | < 0.0001 |

Major clinical outcomes comparing telmisartan and other ARBs.

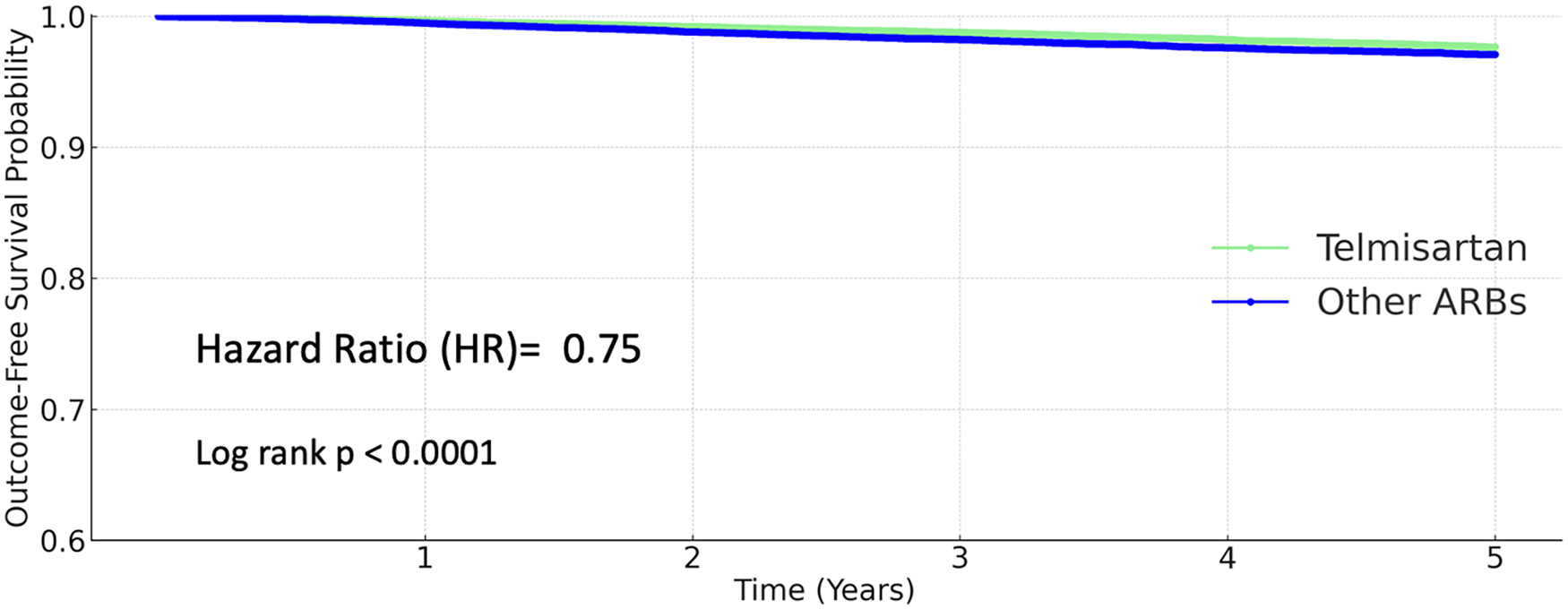

Heart failure

During the 5-year follow-up period, heart failure occurred in 801 patients (1.926%) receiving other ARBs and in 540 patients (1.298%) receiving telmisartan. The 5-year cumulative incidence of heart failure was significantly lower in the telmisartan group. Telmisartan was associated with a 25% relative risk reduction compared to other ARBs (HR 0.75, 95% CI 0.672–0.836; P < 0.0001; Figure 2).

Figure 2

Kaplan–Meier curves for heart failure (telmisartan vs. other ARBs).

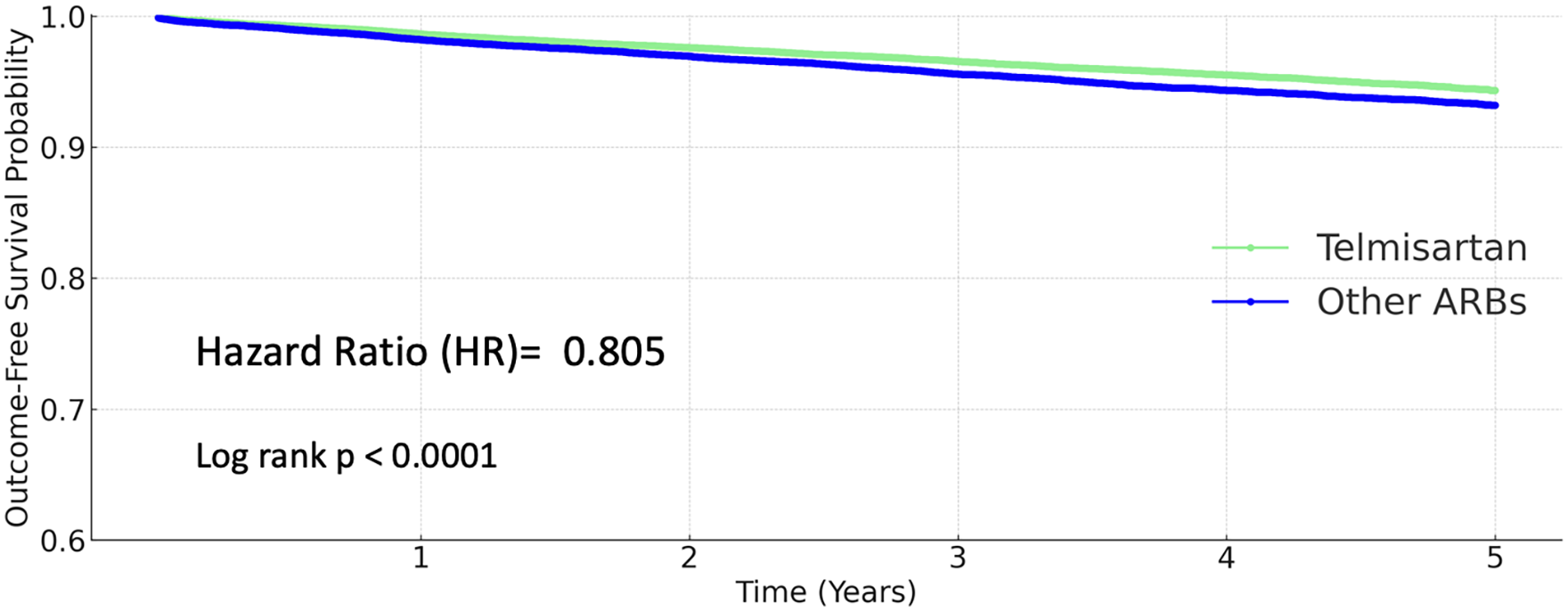

Stroke

Among patients receiving other ARBs, 1,868 strokes (4.667%) occurred, compared to 1,383 events (3.439%) in the telmisartan group. Telmisartan use was associated with a significantly lower risk of stroke (HR 0.805, 95% CI 0.751–0.863; P < 0.0001; Figure 3).

Figure 3

Kaplan–Meier curves for stroke (telmisartan vs. other ARBs).

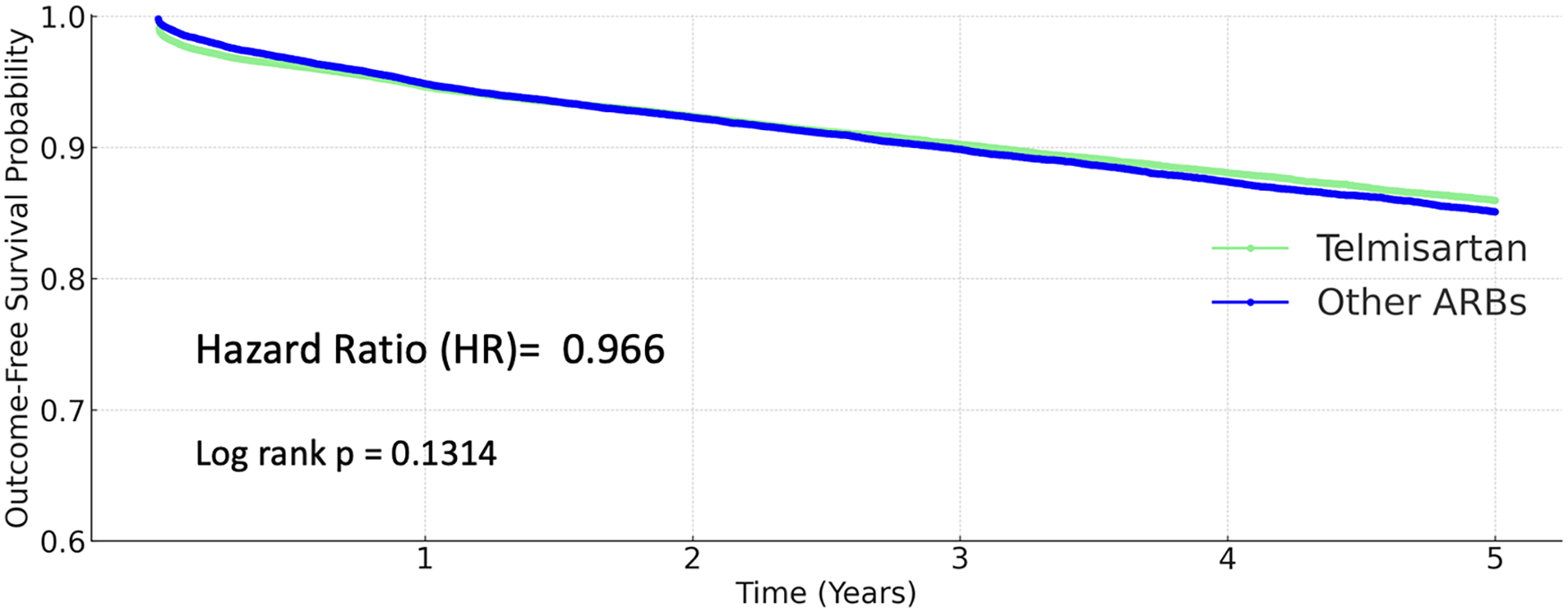

Coronary artery disease

A total of 3,924 coronary artery disease events (10.801%) occurred in the other ARB group, and 3,529 events (9.701%) in the telmisartan group. However, the difference was not statistically significant (HR 0.966, 95% CI 0.923–1.011; P = 0.1314; Figure 4).

Figure 4

Kaplan–Meier curves for coronary artery disease (telmisartan vs. other ARBs).

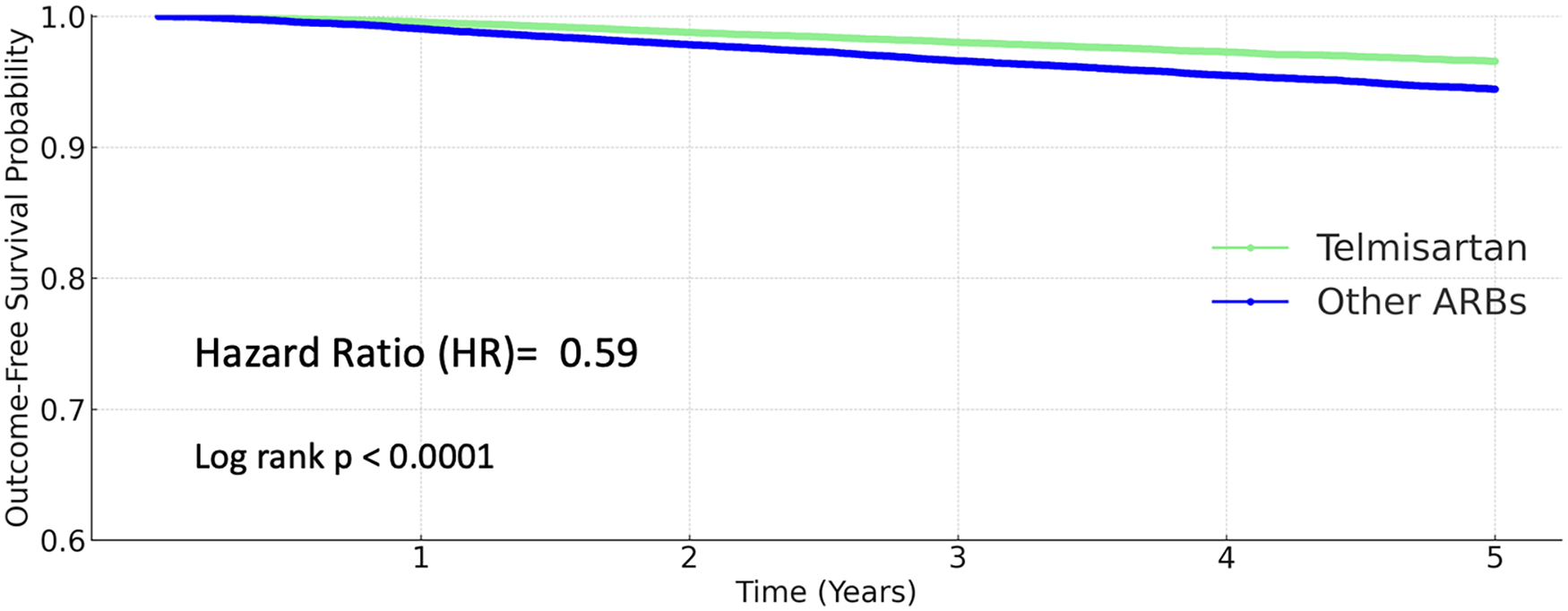

All-cause mortality

Telmisartan use was associated with a markedly reduced risk of all-cause death. The 5-year mortality rate was 3.681% in the other ARBs group and 1.951% in the telmisartan group. The hazard ratio for death with telmisartan was 0.59 (95% CI 0.542–0.642; P < 0.0001; Figure 5).

Figure 5

Kaplan–Meier curves for all-cause mortality (telmisartan vs. other ARBs).

Hazard ratios and 95% confidence interval of all the major outcomes were summarized in a forest plot (Figure 6).

Figure 6

Forest plot of major clinical outcomes comparing telmisartan and other ARBs.

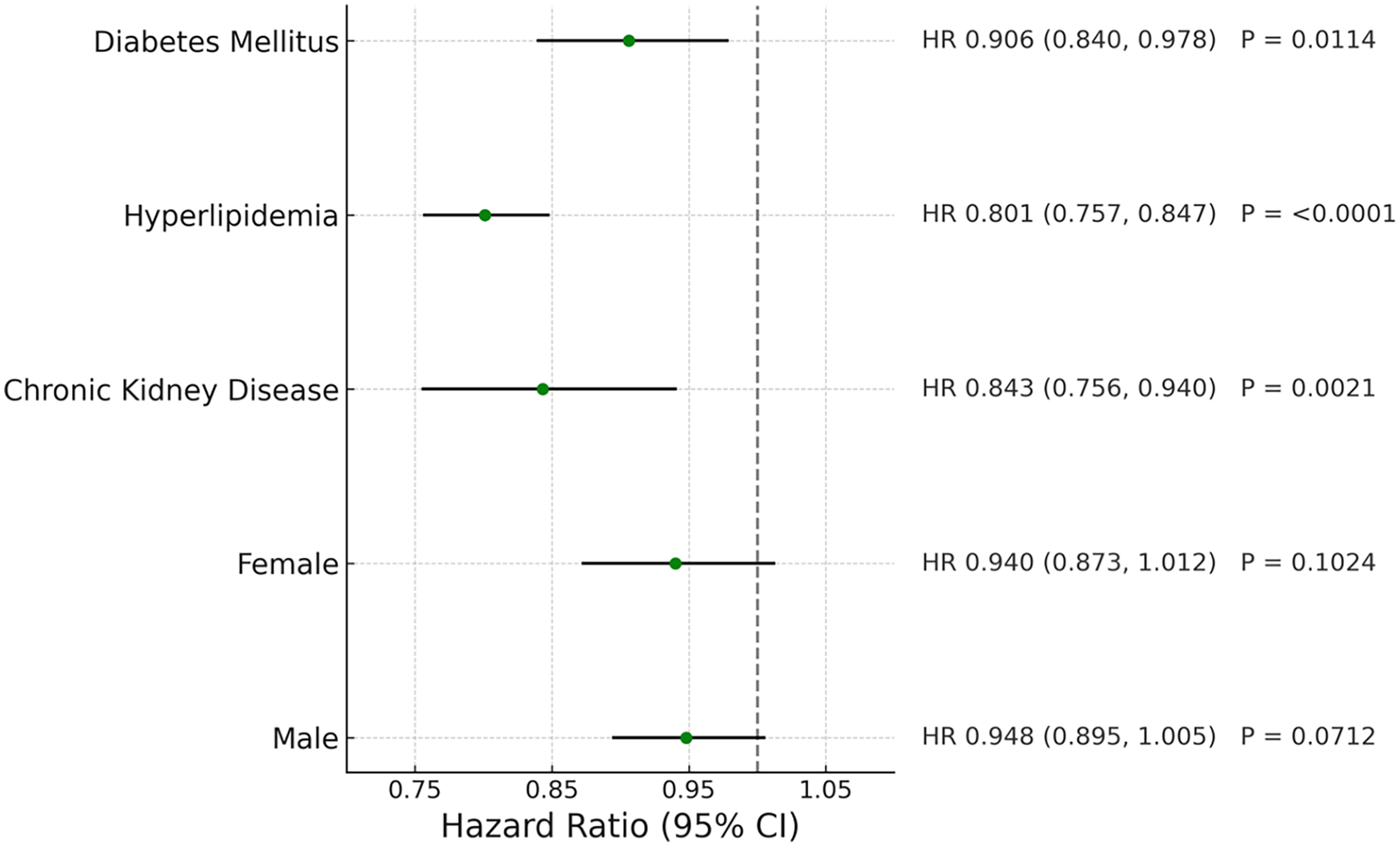

Subgroup analysis

A sensitive analysis stratified by sex, CKD, hyperlipidemia and diabetes in this cohort is shown in Table 3. In both male and female patients, telmisartan use was associated with reduced risks of stroke, heart failure, and all-cause death (P < .05 for both sexes across these outcomes), with no association to coronary artery disease (P = ns).

Table 3

| Events | Group | Hazard ratio, 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | |||

| Heart failure | |||

| Other ARBs | 1.0 | Ref. | |

| Telmisartan | 0.668 (0.578,0.773) | <0.0001 | |

| Stroke | |||

| Other ARBs | 1.0 | Ref. | |

| Telmisartan | 0.837 (0.757,0.925) | 0.0005 | |

| Coronary artery disease | |||

| Other ARBs | 1.0 | Ref. | |

| Telmisartan | 0.948 (0.895,1.005) | 0.0712 | |

| All-cause death | |||

| Other ARBs | 1.0 | Ref. | |

| Telmisartan | 0.691 (0.616,0.776) | <0.0001 | |

| Female | |||

| Heart failure | |||

| Other ARBs | 1.0 | Ref. | |

| Telmisartan | 0.711 (0.605,0.835) | <0.0001 | |

| Stroke | |||

| Other ARBs | 1.0 | Ref. | |

| Telmisartan | 0.847 (0.766,0.937) | 0.0012 | |

| Coronary artery disease | |||

| Other ARBs | 1.0 | Ref. | |

| Telmisartan | 0.94 (0.873,1.012) | 0.1024 | |

| All-cause death | |||

| Other ARBs | 1.0 | Ref. | |

| Telmisartan | 0.638 (0.559,0.729) | <0.0001 | |

| Chronic kidney disease | |||

| Heart failure | |||

| Other ARBs | 1.0 | Ref. | |

| Telmisartan | 0.736 (0.618,0.877) | 0.0006 | |

| Stroke | |||

| Other ARBs | 1.0 | Ref. | |

| Telmisartan | 0.754 (0.652,0.871) | 0.0001 | |

| Coronary artery disease | |||

| Other ARBs | 1.0 | Ref. | |

| Telmisartan | 0.843 (0.756,0.94) | 0.0021 | |

| All-cause death | |||

| Other ARBs | 1.0 | Ref. | |

| Telmisartan | 0.786 (0.657,0.941) | 0.0086 | |

| Hyperlipidemia | |||

| Heart failure | |||

| Other ARBs | 1.0 | Ref. | |

| Telmisartan | 0.631 (0.555,0.717) | <0.0001 | |

| Stroke | |||

| Other ARBs | 1.0 | Ref. | |

| Telmisartan | 0.819 (0.756,0.888) | <0.0001 | |

| Coronary artery disease | |||

| Other ARBs | 1.0 | Ref. | |

| Telmisartan | 0.801 (0.757,0.847) | <0.0001 | |

| All-cause death | |||

| Other ARBs | 1.0 | Ref. | |

| Telmisartan | 0.71 (0.628,0.804) | <0.0001 | |

| Diabetes mellitus | |||

| Heart failure | |||

| Other ARBs | 1.0 | Ref. | |

| Telmisartan | 0.768 (0.659,0.895) | 0.0007 | |

| Stroke | |||

| Other ARBs | 1.0 | Ref. | |

| Telmisartan | 0.781 (0.7,0.871) | <0.0001 | |

| Coronary artery disease | |||

| Other ARBs | 1.0 | Ref. | |

| Telmisartan | 0.906 (0.84,0.978) | 0.0114 | |

| All-cause death | |||

| Other ARBs | 1.0 | Ref. | |

| Telmisartan | 0.704 (0.613,0.808) | <0.0001 | |

Subgroup analysis on the risk of major outcomes.

For patients with diabetes, CKD and hyperlipidemia, telmisartan use was associated with reduced risks of stroke, coronary artery disease, heart failure and all-cause mortality as shown in Figure 7 (P < .05).

Figure 7

Forest plot of coronary artery disease in different patient groups.

We also conducted a smaller analysis comparing telmisartan with specific drugs. Before propensity score matching, the telmisartan cohort included 44,317 patients, whereas the losartan cohort comprised 1,243,749 patients. After propensity score matching, two balanced cohorts were generated for outcome analysis. In the matched comparison, 1,088 heart failure events occurred in the losartan group and 690 in the telmisartan group (HR 0.699, 95% CI 0.636–0.769). For stroke, 2,289 events occurred among losartan users and 1,684 among telmisartan users (HR 0.794, 95% CI 0.746–0.846). Coronary artery disease was observed in 4,809 patients in the losartan cohort and 4,592 in the telmisartan cohort (HR 1.048, 95% CI 1.007–1.092). For all-cause mortality, 1,906 deaths occurred in the losartan cohort and 887 in the telmisartan cohort (HR 0.512, 95% CI 0.473–0.554) (Table 4).

Table 4

| Events | Total number for analysis | 5-year cumulative rate (%) | Hazard ratio, 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart failure | ||||

| Losartan | 48,688 | 1,088 (2.235%) | 1.0 | Ref. |

| Telmisartan | 48,688 | 690 (1.417%) | 0.699 (0.636,0.769) | < 0.0001 |

| Stroke | ||||

| Losartan | 47,313 | 2,289 (4.838%) | 1.0 | Ref. |

| Telmisartan | 47,278 | 1,684 (3.562%) | 0.794 (0.746,0.846) | < 0.0001 |

| Coronary artery disease | ||||

| Losartan | 44,161 | 4,809 (10.89%) | 1.0 | Ref. |

| Telmisartan | 42,901 | 4,592 (10.704%) | 1.048 (1.007,1.092) | 0.0223 |

| All-cause death | ||||

| Losartan | 48,606 | 1,906 (3.921%) | 1.0 | Ref. |

| Telmisartan | 48,628 | 887 (1.824%) | 0.512 (0.473,0.554) | < 0.0001 |

Major clinical outcomes comparing telmisartan and losartan.

Before propensity score matching, the telmisartan cohort included 44,317 patients, whereas the valsartan cohort comprised 313,188 patients. After propensity score matching, two balanced cohorts were generated for outcome analysis. In the matched comparison, 1,498 heart failure events occurred in the valsartan group and 716 in the telmisartan group (HR 0.480, 95% CI 0.439–0.525). For stroke, 1,991 events occurred in the valsartan cohort and 1,751 in the telmisartan cohort (HR 0.875, 95% CI 0.821–0.933). Coronary artery disease was observed in 4,760 valsartan users and 4,733 telmisartan users (HR 0.980, 95% CI 0.941–1.020). For all-cause mortality, 1,516 deaths occurred in the valsartan cohort and 900 in the telmisartan cohort (HR 0.600, 95% CI 0.552–0.651) (Table 5).

Table 5

| Events | Total number for analysis | 5-year cumulative rate (%) | Hazard ratio, 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart failure | ||||

| Valsartan | 50,309 | 1,498 (2.978%) | 1.0 | Ref. |

| Telmisartan | 50,309 | 716 (1.423%) | 0.48 (0.439,0.525) | < 0.0001 |

| Stroke | ||||

| Valsartan | 48,134 | 1,991 (4.136%) | 1.0 | Ref. |

| Telmisartan | 48,841 | 1,751 (3.585%) | 0.875 (0.821,0.933) | < 0.0001 |

| Coronary artery disease | ||||

| Valsartan | 43,334 | 4,760 (10.984%) | 1.0 | Ref. |

| Telmisartan | 44,393 | 4,733 (10.662%) | 0.98 (0.941,1.02) | 0.3259 |

| All-cause death | ||||

| Valsartan | 50,256 | 1,516 (3.017%) | 1.0 | Ref. |

| Telmisartan | 50,249 | 900 (1.791%) | 0.6 (0.552,0.651) | < 0.0001 |

Major clinical outcomes comparing telmisartan and valsartan.

Discussion

Telmisartan is distinguished among angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) by its high lipophilicity and long elimination half-life, allowing for sustained 24-hour blood pressure control. This pharmacokinetic advantage is particularly relevant for mitigating early morning blood pressure surges, which are known to increase the risk of cerebrovascular events such as stroke (23–25). In addition, telmisartan acts as a partial agonist of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR-γ), a nuclear receptor involved in glucose and lipid metabolism. This pleiotropic activity has been linked to anti-inflammatory effects, endothelial stabilization, and improved insulin sensitivity, which may contribute to both neuroprotective and cardioprotective benefits (7, 26–32).

In our study, telmisartan use was associated with significantly lower risks of stroke, heart failure, and all-cause mortality compared to other ARBs. These associations were consistent across key subgroups, including patients with diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and hyperlipidemia—populations in which telmisartan's pleiotropic mechanisms may offer additional clinical value. The large, real-world nature of our cohort, comprising over 1.9 million patients and a well-matched analytic sample of 41,598 individuals in each treatment group, enhances the generalizability of our findings. Moreover, the consistency of the observed treatment effects across diverse clinical strata strengthens the internal validity of the results and suggests that telmisartan may confer benefits beyond blood pressure reduction alone.

In the ARB-specific analyses comparing telmisartan with losartan and valsartan, the overall pattern of hazard ratios for heart failure, stroke, and all-cause mortality was directionally similar across both comparisons, with consistently lower estimates observed in the telmisartan cohorts. The primary distinction between the two analyses emerged in the coronary artery disease outcome. In the telmisartan–losartan comparison, the hazard ratio for coronary artery disease was slightly above unity (favoring losartan), whereas in the telmisartan–valsartan comparison the estimate was close to 1.0 with no statistically significant difference. This divergence suggests that the coronary artery disease findings may vary depending on the specific ARB comparator, potentially reflecting differences in prescribing patterns, population characteristics, or residual confounding that persists in real-world data despite matching. Nevertheless, when viewed together, the two comparisons provide a broader context for interpreting how telmisartan performs relative to individual ARBs in routine clinical settings.

Our findings also align with several landmark clinical trials of telmisartan. The ONTARGET trial demonstrated that telmisartan was non-inferior to ramipril in reducing major cardiovascular events in patients with vascular disease or diabetes with end-organ damage and was associated with fewer adverse effects and better treatment adherence (12). Similarly, the TRANSCEND trial, which focused on ACE inhibitor–intolerant patients, showed that telmisartan was well-tolerated and modestly reduced the risk of the composite outcome of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, or stroke (13). The PRoFESS trial, which evaluated telmisartan for secondary stroke prevention, did not find a significant reduction in recurrent stroke risk (33). However, the PRoFESS population included patients with recent ischemic stroke, whereas our cohort excluded individuals with a history of stroke or cardiovascular disease. This key difference in baseline risk may help explain the discrepancy in outcomes and suggests that telmisartan may be more effective in primary prevention settings or among patients without established cerebrovascular disease.

Other trials have further explored telmisartan's renal and cardiovascular effects. In the AMADEO trial, telmisartan demonstrated superior efficacy to losartan in reducing proteinuria among patients with diabetic nephropathy (34, 35). The DETAIL study found that telmisartan and enalapril offered comparable long-term renal protection in type 2 diabetic patients with early nephropathy (36, 37). Despite heterogeneity in trial populations and endpoints, a consistent finding across all major studies—including our own—is telmisartan's favorable safety and tolerability profile. Due to the smaller patient numbers in the telmisartan cohorts and possible differences between cohorts, the generalizability of our findings may be somewhat limited. Nevertheless, these results provide real-world evidence and the potential wider use of telmisartan and might guide future well-controlled clinical trials.

Nonetheless, several limitations inherent to our retrospective, observational design should be acknowledged. First, although propensity score matching was employed to minimize baseline differences, residual confounding from unmeasured variables, such as frailty, socioeconomic status, and baseline blood pressure control, was not accounted for. Second, our use of data from the TriNetX platform—while extensive—relies on the accuracy and completion of electronic health records, which may vary across participating institutions. Third, detailed information on medication dosage, duration of therapy, and adherence was not available in the structured dataset, precluding dose-response analyses or evaluations of cumulative exposure. Fourth, the relatively small population of telmisartan-using patients added more confounding to the comparison between telmisartan and other drugs in this genre.

Conclusion

In this large-scale, real-world cohort study leveraging the TriNetX Global Collaborative Network, we evaluated cardiovascular outcomes in more than 1.9 million patients with hypertension and identified 41,598 well-matched individuals in each treatment group. Telmisartan use was consistently linked to reduced risks of stroke, heart failure, and all-cause mortality compared with other ARBs. These findings, observed across key clinical subgroups, suggest that telmisartan may offer incremental cardiovascular and cerebrovascular benefits beyond blood pressure control. While further prospective studies are needed to confirm causality, our results support consideration of telmisartan as a potentially advantageous therapeutic option for hypertensive patients at elevated cardiovascular risk.

Statements

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the TriNetX Global Health Research Network. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study and are not publicly available. Data may be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Taichung Veterans General Hospital. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants' legal guardians/next of kin as all data used in this study were de-identified. The TriNetX platform adheres to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) standards.

Author contributions

T-YC: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Y-CL: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. G-YL: Resources, Writing – review & editing. H-CH: Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was financially supported by Taichung Veterans General Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan (TCVGH-1144601B and TCVGH-PNCHU1149102) and National Science and Technology Council, Republic of China (NSTC 113-2320-B-005 -008 -MY3).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. During the preparation of this work the authors used ChatGPT and Primo in order to improve the readability. After using this tool/service, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and will take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Redon J Tellez-Plaza M Orozco-Beltran D Gil-Guillen V Pita Fernandez S Navarro-Perez J et al Impact of hypertension on mortality and cardiovascular disease burden in patients with cardiovascular risk factors from a general practice setting: the ESCARVAL-risk study. J Hypertens. (2016) 34(6):1075–83. 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000930

2.

Rikhi R Bhatia HS Schaich CL Ashburn N Tsai MY Michos ED et al Association of lp(a) (lipoprotein[a]) and hypertension in primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: the MESA. Hypertension. (2023) 80(2):352–60. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.122.20189

3.

Costanzo P Perrone-Filardi P Petretta M Marciano C Vassallo E Gargiulo P et al Calcium channel blockers and cardiovascular outcomes: a meta-analysis of 175,634 patients. J Hypertens. (2009) 27(6):1136–51. 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3283281254

4.

Wiysonge CS Bradley HA Volmink J Mayosi BM Mbewu A Opie LH . Beta-blockers for hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2017) 2012(8):CD002003. 10.1002/14651858.CD002003.pub5

5.

Li EC Heran BS Wright JM . Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors versus angiotensin receptor blockers for primary hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2014) 2014(8):CD009096. 10.1002/14651858.CD009096.pub2

6.

McDermott MM Bazzano L Peterson CA et al Effect of telmisartan on walking performance in patients with lower extremity peripheral artery disease: the TELEX randomized clinical trial. JAMA. (2022) 328(13):1315–25. 10.1001/jama.2022.16797

7.

Benson SC Pershadsingh HA Ho CI Chittiboyina A Desai P Pravenec M et al Identification of telmisartan as a unique angiotensin II receptor antagonist with selective PPARgamma-modulating activity. Hypertension. (2004) 43(5):993–1002. 10.1161/01.HYP.0000123072.34629.57

8.

Battershill AJ Scott LJ . Telmisartan: a review of its use in the management of hypertension. Drugs. (2006) 66(1):51–83. 10.2165/00003495-200666010-00004

9.

Rodgers A Salam A Schutte AE Cushman WC de Silva HA Di Tanna GL et al Efficacy and safety of a novel low-dose triple single-pill combination of telmisartan, amlodipine and indapamide, compared with dual combinations for treatment of hypertension: a randomised, double-blind, active-controlled, international clinical trial. Lancet. (2024) 404(10462):1536–46. 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)01744-6

10.

Dalal J Guha S Reddy YVC Ponde CK Shrivastava S Badani R et al Telmisartan plus amlodipine as the preferred initial combination in newly diagnosed Indian patients with hypertension: an expert consensus statements. J Assoc Physicians India. (2023) 71(12):56–61. 10.59556/japi.71.0407

11.

Suksomboon N Poolsup N Prasit T . Systematic review of the effect of telmisartan on insulin sensitivity in hypertensive patients with insulin resistance or diabetes. J Clin Pharm Ther. (2012) 37(3):319–27. 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2011.01295.x

12.

Investigators O, YusufSTeoKKPogueJDyalLCoplandIet alTelmisartan, ramipril, or both in patients at high risk for vascular events. N Engl J Med. (2008) 358(15):1547–59. 10.1056/NEJMoa0801317

13.

Telmisartan Randomised AssessmeNt Study in ACEiswcDI, YusufSTeoKAndersonCPogueJDyalLet alEffects of the angiotensin-receptor blocker telmisartan on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients intolerant to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. (2008) 372(9644):1174–83. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61242-8

14.

Benndorf RA Rudolph T Appel D Schwedhelm E Maas R Schulze F et al Telmisartan improves insulin sensitivity in nondiabetic patients with essential hypertension. Metab Clin Exp. (2006) 55(9):1159–64. 10.1016/j.metabol.2006.04.013

15.

Li L Luo Z Yu H Feng X Wang P Chen J et al Telmisartan improves insulin resistance of skeletal muscle through peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-delta activation. Diabetes. (2013) 62(3):762–74. 10.2337/db12-0570

16.

Chujo D Yagi K Asano A Muramoto H Sakai S Ohnishi A et al Telmisartan treatment decreases visceral fat accumulation and improves serum levels of adiponectin and vascular inflammation markers in Japanese hypertensive patients. Hypertens Res. (2007) 30(12):1205–10. 10.1291/hypres.30.1205

17.

Fu XX Wei B Cao HM Duan R Deng Y Lian HW et al Telmisartan alleviates Alzheimer’s disease-related neuropathologies and cognitive impairments. J Alzheimers Dis. (2023) 94(3):919–33. 10.3233/JAD-230133

18.

Kume K Hanyu H Sakurai H Takada Y Onuma T Iwamoto T . Effects of telmisartan on cognition and regional cerebral blood flow in hypertensive patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Geriatr Gerontol Int. (2012) 12(2):207–14. 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2011.00746.x

19.

Wen X Otoo MN Tang J Brothers T Ward KE Asal N et al Angiotensin receptor blockers for hypertension and risk of epilepsy. JAMA Neurol. (2024) 81(8):866–74. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2024.1714

20.

Yum Y Kim JH Joo HJ Kim YH Kim EJ . Three-year cardiovascular outcomes of telmisartan in patients with hypertension: an electronic health record-based cohort study. Am J Hypertens. (2024) 37(6):429–37. 10.1093/ajh/hpae012

21.

Palchuk MB London JW Perez-Rey D Drebert ZJ Winer-Jones JP Thompson CN et al A global federated real-world data and analytics platform for research. JAMIA Open. (2023) 6(2):ooad035. 10.1093/jamiaopen/ooad035

22.

Ludwig RJ Anson M Zirpel H Thaci D Olbrich H Bieber K et al A comprehensive review of methodologies and application to use the real-world data and analytics platform TriNetX. Front Pharmacol. (2025) 16:1516126. 10.3389/fphar.2025.1516126

23.

Kario K Shimada K Pickering TG . Clinical implication of morning blood pressure surge in hypertension. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. (2003) 42(Suppl 1):S87–91. 10.1097/00005344-200312001-00019

24.

Bilo G Grillo A Guida V Parati G . Morning blood pressure surge: pathophysiology, clinical relevance and therapeutic aspects. Integr Blood Press Control. (2018) 11:47–56. 10.2147/IBPC.S130277

25.

Renna NF Ramirez JM Murua M Bernasconi PA Repetto JM Verdugo RA et al Morning blood pressure surge as a predictor of cardiovascular events in patients with hypertension. Blood Press Monit. (2023) 28(3):149–57. 10.1097/MBP.0000000000000641

26.

Jung AD Kim W Park SH Park JS Cho SC Hong SB et al The effect of telmisartan on endothelial function and arterial stiffness in patients with essential hypertension. Korean Circ J. (2009) 39(5):180–4. 10.4070/kcj.2009.39.5.180

27.

Terashima M Kaneda H Nasu K Matsuo H Habara M Ito T et al Protective effect of telmisartan against endothelial dysfunction after coronary drug-eluting stent implantation in hypertensive patients. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. (2012) 5(2):182–90. 10.1016/j.jcin.2011.09.022

28.

Siragusa M Sessa WC . Telmisartan exerts pleiotropic effects in endothelial cells and promotes endothelial cell quiescence and survival. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. (2013) 33(8):1852–60. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300985

29.

Cao Z Yang Y Hua X Wu R Wang J Zhou M et al Telmisartan promotes proliferation and differentiation of endothelial progenitor cells via activation of akt. Chin Med J (Engl). (2014) 127(1):109–13. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0366-6999.20122896

30.

Li H Lu W Cai WW Wang PJ Zhang N Yu CP et al Telmisartan attenuates monocrotaline-induced pulmonary artery endothelial dysfunction through a PPAR gamma-dependent PI3K/akt/eNOS pathway. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. (2014) 28(1):17–24. 10.1016/j.pupt.2013.11.003

31.

Jin Z Tan Q Sun B . Telmisartan ameliorates vascular endothelial dysfunction in coronary slow flow phenomenon (CSFP). Cell Biochem Funct. (2018) 36(1):18–26. 10.1002/cbf.3313

32.

Zhan X Chen W Chen J Lei C Wei L . Telmisartan mitigates high-glucose-induced injury in renal glomerular endothelial cells (rGECs) and albuminuria in diabetes mice. Chem Res Toxicol. (2021) 34(9):2079–86. 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.1c00159

33.

Yusuf S Diener HC Sacco RL Cotton D Ounpuu S Lawton WA et al Telmisartan to prevent recurrent stroke and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. (2008) 359(12):1225–37. 10.1056/NEJMoa0804593

34.

Bakris G Burgess E Weir M Davidai G Koval S Investigators AS . Telmisartan is more effective than losartan in reducing proteinuria in patients with diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int. (2008) 74(3):364–9. 10.1038/ki.2008.204

35.

Bichu P Nistala R Khan A Sowers JR Whaley-Connell A . Angiotensin receptor blockers for the reduction of proteinuria in diabetic patients with overt nephropathy: results from the AMADEO study. Vasc Health Risk Manag. (2009) 5(1):129–40.

36.

Barnett AH Bain SC Bouter P Karlberg B Madsbad S Jervell J et al Angiotensin-receptor blockade versus converting-enzyme inhibition in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. (2004) 351(19):1952–61. 10.1056/NEJMoa042274

37.

Barnett AH . Preventing renal complications in diabetic patients: the diabetics exposed to telmisartan and enalaprIL (DETAIL) study. Acta Diabetol. (2005) 42(Suppl 1):S42–49.

Summary

Keywords

Telmisartan, angiotensin receptor blockers, hypertension, stroke, mortality, real-world evidence

Citation

Chen T-Y, Lin Y-C, Liu G-Y and Hung H-C (2026) Comparative effectiveness of telmisartan vs. other angiotensin receptor blockers in reducing hypertension-related cerebrovascular and cardiovascular events: a real-world retrospective study using the TriNetX network. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 12:1715032. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1715032

Received

14 October 2025

Revised

04 December 2025

Accepted

16 December 2025

Published

22 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

DeLisa Fairweather, Mayo Clinic Florida, United States

Reviewed by

Yogesh Ahire, KBHSS Trusts Institute of Pharmacy, India

Huijin Lee, Seoul National University Hospital, Republic of Korea

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Chen, Lin, Liu and Hung.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Hui-Chih Hung hchung@dragon.nchu.edu.tw Guang-Yaw Liu liugy@csmu.edu.tw

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.