Abstract

Background:

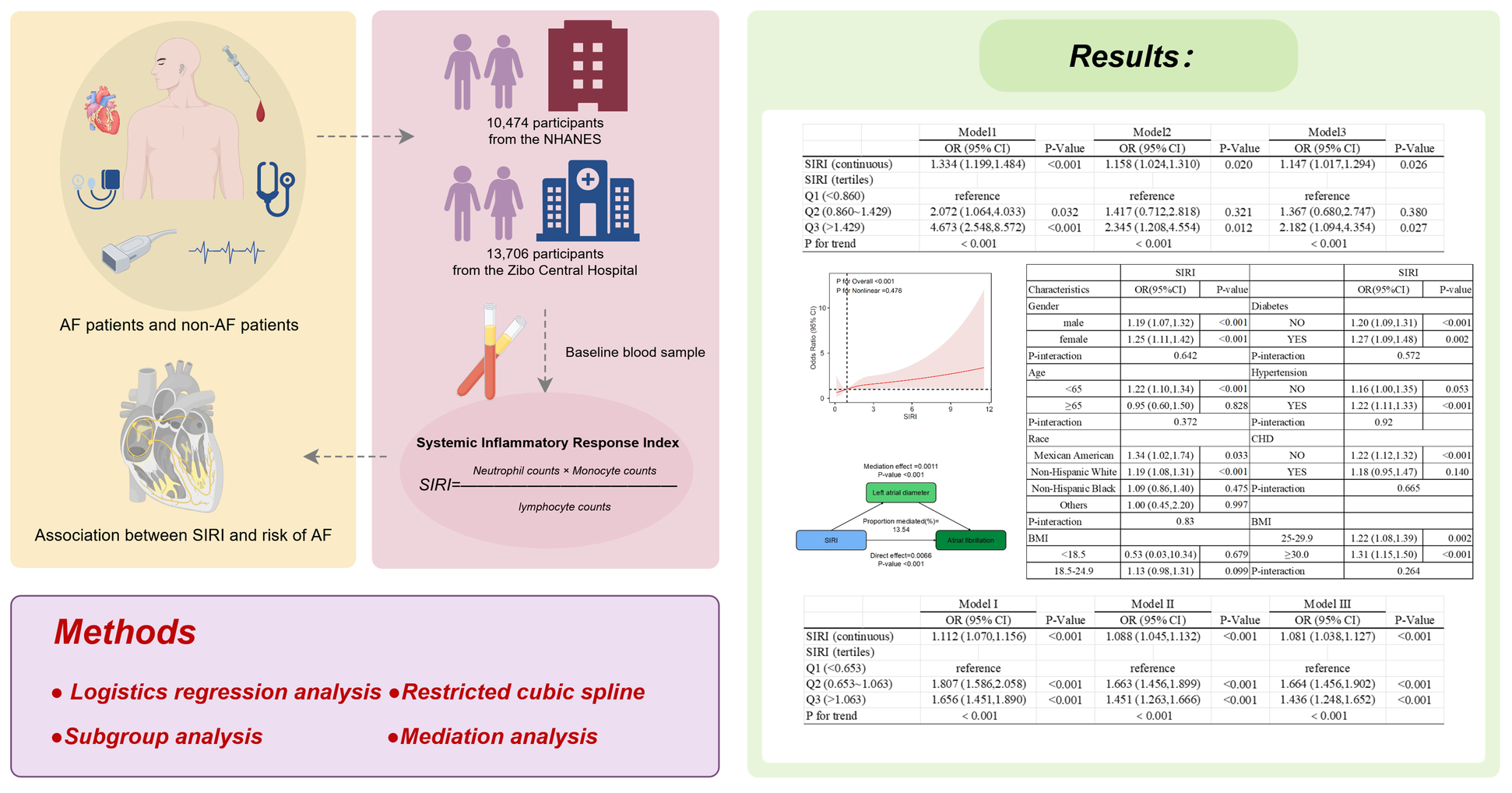

Inflammation plays a central role in the pathogenesis of atrial fibrillation (AF), a common cardiac arrhythmia. Complete blood count (CBC)-derived markers of inflammation, including the systemic inflammatory index (SII) and systemic inflammatory response index (SIRI), have emerged as novel biomarkers of systemic inflammation. Although small prior studies have reported associations between certain inflammatory markers and AF, their limited sample sizes and potential baseline imbalances prevent definitive conclusions. Using a large population-based cohort, this study examines the association between CBC-derived inflammatory markers—SIRI, SII, monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio (MLR), aggregate index of systemic inflammation (AISI), neutrophil-monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio (NMLR), neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR)—and the risk of AF, and investigates potential mediating mechanisms by integrating clinical data.

Methods:

This cross-sectional analysis included 10,474 adults aged ≥20 years from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2013–2020 and was validated in 13,707 adults aged ≥20 years from Zibo Central Hospital 2015–2024. Seven inflammatory markers were derived from CBC data and categorized into low, medium, and high quartiles according to their distributions. A weighted multivariable logistic regression adjusted for confounders, including age, sex, hypertension, and diabetes. Associations between inflammatory markers and atrial fibrillation were expressed as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Restricted cubic spline (RCS) regression assessed nonlinear relationships. Subgroup and interaction analyses evaluated the influence of demographic and clinical factors. Finally, a mediation model examined the mediating role of left atrial diameter.

Results:

Of the 10,474 participants in the NHANES database, 136 (1.3%) were diagnosed with AF. After full adjustment, the highest SIRI tertile showed a significantly increased risk of AF compared with the lowest tertile (OR = 2.182; 95% CI: 1.094–4.354; P = 0.027). RCS analysis revealed a linear positive association between SIRI and AF risk (overall P > 0.05). Subgroup analyses and interaction tests indicated that the positive association between SIRI and AF persisted across different conditions (all p-value for interaction > 0.05). Results were then validated using the case management system of Zibo Central Hospital. In that cohort, after full adjustment, the highest SIRI tertile again had a significantly increased risk of AF vs. the lowest tertile (OR = 1.436; 95% CI: 1.248–1.652; P < 0.001). Mediation analysis indicated that LA diameter mediated 13.54% of the association between SIRI and AF.

Conclusion:

This study suggests that elevated SIRI may represent a potential biomarker and is associated with an increased risk of AF, and found that left atrial diameter may partially mediate this relationship, suggesting SIRI as a potential inflammatory biomarker for AF prediction. Although other CBC-derived markers did not show significant associations, the results underscore inflammation's role in AF pathogenesis. Further longitudinal studies are needed to validate these findings and clarify the underlying mechanisms.

Graphical Abstract

Created using Figdraw.

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common sustained arrhythmia and is linked to higher risks of stroke, heart failure, and death, contributing to rising cardiovascular incidence and mortality (1, 2). The estimated prevalence of AF in adults is 2% to 4%, and its incidence is climbing rapidly, with 12.1 million people projected to be affected by 2030. Prevalence increases with age: it is under 0.5% in the 40–50 age group and reaches 5% to 15% by age 80, and it occurs more often in men than in women. In high-risk patients, the annual risk of thromboembolic stroke can reach 9%, and mortality is doubled (3).

Peripheral blood cells and their inflammatory factors play a crucial role in the occurrence and maintenance of AF and are important therapeutic targets for intervention. Previous studies have shown that macrophages, monocytes, lymphocytes and their products (such as IL-1β, IL-6) IL-8 and TNF-α are involved in the pathogenesis of AF (4–10). Macrophages, monocytes lymphocytes and other immune cells are involved in regulating the differentiation of CD4+ T cells and B cells, promoting the occurrence of local inflammatory response, and inducing the occurrence of AF. In addition, monocytes and macrophages can secrete IL-1 β which activates downstream proteins to increase susceptibility to AF after binding to the receptor. In addition, Platelets can also promote the occurrence and maintenance of AF through TGF-β-dependent mechanisms (11). Left atrial diameter is an indispensable index to evaluate left atrial function. During atrial fibrillation, abnormal electrical signals in the atrium lead to atrial systolic and diastolic dysfunction, which can cause atrial enlargement in the long term. In addition, left atrial enlargement is also an important risk factor for AF. Long-term hypertension, valvular heart disease and other diseases can lead to increased left atrial pressure or volume load, causing structural and functional changes of atrial myocytes, thereby increasing the risk of atrial fibrillation, forming a vicious circle. Plasma levels of inflammatory markers, such as IL-6, are associated with left atrial diameter and may promote atrial structural remodeling in patients with AF, leading to the occurrence of AF (12, 13). AF is an inflammatory disease and peripheral blood cells and their inflammatory factors play a crucial role in its pathogenesis and progression. However, there is limited research available on the relationship between AF and CBC-derived inflammatory markers.

CBC-derived inflammatory markers include neutrophils, lymphocytes, platelets, and monocytes. These markers are employed to predict outcomes in various inflammation-related diseases. The NLR has shown improved prognostic value for cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality and related outcomes (14–16). The SII and SIRI are recently proposed composite biomarkers that combine immune cell subsets with platelet counts (17, 18). Researchers have widely applied these indices to examine links between chronic inflammation and diverse conditions such as cancer, metabolic disorders, and other inflammatory diseases (19, 20). Although some studies report associations between SII or SIRI and atrial fibrillation (AF) in stroke patients and in paroxysmal AF (21, 22), the evidence derives mainly from small clinical cohorts, and no definitive conclusion has been reached, underscoring the need for population-level investigation.

The relationships between other CBC-derived inflammatory markers and AF have not been fully evaluated. To our knowledge, the association between CBC-derived inflammatory markers and left atrial diameter has not been clearly established. Therefore, we conducted a cross-sectional study using the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) database and the inpatient case system of Zibo Central Hospital to further examine these associations. We assessed links between inflammatory markers and AF, investigated associations between additional inflammatory markers and AF, and identified potential mediators of the inflammatory marker–AF relationship using mediation analysis. The primary objective of this study was to assemble evidence on biomarkers that might enable earlier detection of AF.

Methods

Data selection and study design

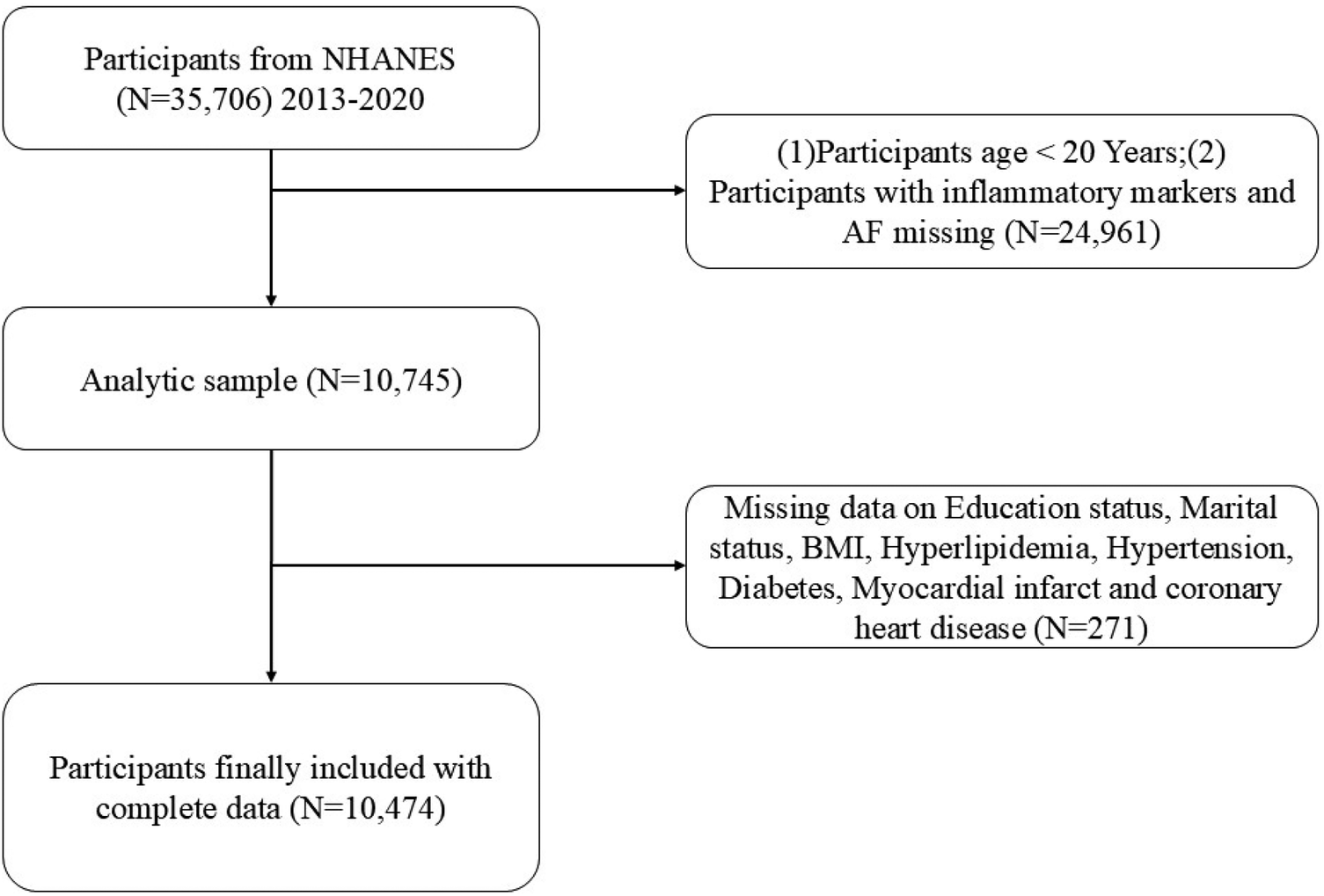

The NHANES employs a complex sampling design to produce a representative sample of the US population every two years. Its primary purpose is to assess the health and nutritional status of Americans. The NHANES program was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Center for Health Statistics, and each participant provided written informed consent. The survey includes demographic, dietary, physical examination, laboratory, and questionnaire data. A total of 10,474 participants aged 20 years and older were included across four survey cycles from 2013 to 2020 (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Flowchart of the participant selection from NHANES 2013–2020.

In addition, through the inpatient case management system of Zibo Central Hospital, from 2015 to 2024. Information on eligible participants diagnosed with atrial fibrillation met inclusion criteria and after exclusion criteria, a total of 13,707 patients aged 20 years or older were included. Exclusion criteria included a history of congenital heart disease, valvular heart disease, left ventricular systolic dysfunction, cardiomyopathy, previous cardiac surgery, thyroid disease, recent infection, autoimmune or inflammatory diseases, and malignant tumors with a life expectancy shorter than 1 year or those suffering from other end-stage diseases.

The definition of inflammatory markers

Based on the obtained peripheral blood cell counts, we calculated seven inflammation biomarkers: SIRI,MLR,AISI,NMLR,NLR,PLR and SII. The calculations were defined as: SIRI=neutrophil counts×monocyte counts/lymphocyte counts, MLR = monocyte counts/lymphocyte counts, AISI=neutrophil counts×platelet counts×monocyte counts/lymphocyte counts, NMLR=(monocyte counts + neutrophil counts)/lymphocyte counts, NLR=neutrophil counts/lymphocyte counts, PLR=platelet counts/lymphocyte counts, SII=platelet counts×neutrophil counts/lymphocyte counts.

The definition of AF

In the NHANES database, according to the 10th revision of the International Classification of Diseases, the primary outcome of the study was atrial fibrillation (code I48) (23).

In the inpatient case management system of Zibo Central Hospital. All participants underwent a 12-lead ECG and were examined by a cardiologist. The diagnosis of AF is based on irregular R-R intervals, absence of regular P waves, and disordered atrial activation on ECG.

Echocardiography

Transthoracic echocardiography was performed in all participants to record the anteroposterior diameter of the left atrium.

The covariates

In the NHANES database, we included the following covariates: age (years), gender (male/female), race (Mexican American/non-Hispanic White/non-Hispanic Black/other races), and educational attainment classified as less than high school, high school or equivalent, and more than high school. Body Mass Index (BMI) was categorized as <18.5, 18.5–24.9, 25–29.9, and ≥30 kg/m2, corresponding to underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obesity, respectively. Smoking status was classified as current smokers (100 cigarettes or more in lifetime, currently smoking some days or every day) or never smokers (including those who never smoked [<100 cigarettes in lifetime] or former smokers [100 cigarettes or more in lifetime, but now never smoke]). Activity status was classified as active (engaging in moderate or vigorous work, exercise, and recreational activities) or inactive (engaging in non-moderate or non-vigorous work, exercise, and recreational activities). Hypertension was defined as (I) average systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg, (II) average diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg, (III) current use of antihypertensive medication, or (IV) self-reported hypertension. Diabetes was defined as self-reported diagnosis of diabetes and use of diabetes medication or insulin. Hyperlipidemia was classified according to the Adult Treatment Panel III (ATP 3) of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) as total cholesterol ≥200 mg/dL, triglycerides ≥150 mg/dL, HDL <40 mg/dL in males and <50 mg/dL in females, or low-density lipoprotein ≥130 mg/dL. Alternatively, individuals who reported using cholesterol-lowering drugs were also classified as having hyperlipidemia. Coronary heart disease (CHD) was defined as self-reported coronary heart disease. Myocardial infarction (MI) was defined as self-reported myocardial infarction. In inpatient Case Management System of Zibo Central Hospital, we collected comprehensive patient data, including age, gender, hypertension, diabetes, BMI and other related indicators. Clinical examination and laboratory test results were also collected. Including lymphocyte count, monocyte count, neutrophil count, platelet count, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), total cholesterol (TC), triglyceride (TG), low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDLC), high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDLC), blood glucose level (GLU), Serum uric acid concentration, serum creatinine level.

Statistical methods

This study used the NHANES database. Because the NHANES sampling design is complex, participant data from 2013 to 2020 were weighted according to the analysis and reporting guidelines to ensure national representativeness. Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and categorical variables as proportions. Differences in baseline characteristics between non-AF and AF groups were assessed using weighted Student's t-tests for continuous variables and weighted chi-square tests for categorical variables. Inflammatory markers were categorized into tertiles based on their unweighted distributions within the NHANES cohort for analysis. First, survey-weighted multivariable logistic regression was used to assess the association between inflammatory markers and AF in three models. We first analyzed a crude model (Model 1). Next, we adjusted for age, gender, race, and education level (Model 2). Finally, we adjusted for age, gender, race, education level, BMI, smoking status, activity status, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, myocardial infarction, and coronary heart disease (Model 3). These three multivariable logistic regression models were used to estimate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the relationship between inflammatory markers and AF. Additionally, we generated restricted cubic spline (RCS) plots to assess potential nonlinear associations between inflammatory markers and AF. We also conducted subgroup and interaction analyses across all covariates to evaluate the robustness of the findings. Similarly, we used the inpatient case management system of Zibo Central Hospital to analyze patients' baseline characteristics. Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and categorical variables are presented as proportions. Differences in baseline characteristics between the non-AF and AF groups were compared using t-tests for continuous variables and weighted chi-square tests for categorical variables.We also applied survey multivariate logistic regression to assess the association between inflammatory markers and AF. First, we fitted an unadjusted model (Model I). Next, we adjusted for age, sex, BMI, hypertension, and diabetes (Model II). Finally, we additionally adjusted for ALT, AST, triglycerides, cholesterol, HDL, LDL, blood glucose, uric acid, and creatinine (Model III). These three models were used to estimate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the associations between inflammatory markers and AF. In addition, we used mediation analysis to quantify the direct effect of SIRI on AF risk and the indirect effect mediated by atrial diameter.

Data analysis was conducted using Empower Stats (version 4.0), Stata MP 16.0 and R studio (version 4.3.0). Finally, all statistical tests were two-sided, and a p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

General characteristics of the study population

Using the NHANES 2013–2020 dataset, we analyzed 10,474 participants. The cohort had a mean age of 54.21 ± 16.56 years and comprised 43.08% males and 56.92% females. Participants were classified as AF patients (n = 136) or non-AF patients (n = 10,338). Significant differences between the AF and non-AF groups were observed for age, sex, race, education level, BMI, smoking status, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, coronary heart disease, and CBC-derived indicators (all p < 0.05). Marital status did not differ between the groups. Compared with participants without AF, those with AF were more often older, male, predominantly non-Hispanic white, more highly educated, and had higher BMI. Additionally, the prevalence of comorbidities was higher among patients with AF, including hypertension, diabetes, myocardial infarction, and coronary heart disease (Table 1). Using the inpatient case system of Zibo Central Hospital, we identified 13,706 participants. The mean age was 63.50 ± 11.65 years; males comprised 50.67% and females 49.33% of the sample. Participants were classified into an AF group (n = 1722) and a non-AF group (n = 11,984). Most laboratory indices differed significantly between the AF and non-AF groups, with the exception of alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and glucose (all p < 0.05). In addition, patients with AF had a higher incidence of comorbidities such as hypertension and diabetes (Supplementary Table S1).

Table 1

| Variables | Overall | Non - AF | AF | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 10,474) | (n = 10,338) | (n = 136) | ||

| Age | 54.21 ± 16.56 | 53.97 ± 16.46 | 71.45 ± 9.99 | <0.001 |

| Gender | 0.009 | |||

| Male | 43.08 | 42.93 | 53.61 | |

| Female | 56.92 | 57.07 | 46.39 | |

| Race | <0.001 | |||

| Mexican American | 10.71 | 10.81 | 3.96 | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 71.61 | 71.37 | 88.52 | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 9.91 | 10.02 | 2.37 | |

| Others | 7.77 | 7.80 | 5.15 | |

| Education level | 0.013 | |||

| <High school | 11.45 | 11.55 | 4.56 | |

| High school | 23.72 | 23.63 | 30.04 | |

| College or more | 64.83 | 64.82 | 65.40 | |

| Marital status | 0.487 | |||

| Married | 60.16 | 60.12 | 62.94 | |

| Unmarried | 39.84 | 39.88 | 37.06 | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 0.018 | |||

| <18.5 | 1.17 | 1.18 | 3.21 | |

| 18.5–24.9 | 22.10 | 21.06 | 25.99 | |

| 25–29.9 | 31.62 | 31.09 | 33.94 | |

| ≥30.0 | 45.11 | 46.67 | 36.86 | |

| Smoking status | <0.001 | |||

| Ever | 26.69 | 26.36 | 49.56 | |

| Never | 53.48 | 53.61 | 44.05 | |

| Current | 19.83 | 20.03 | 6.39 | |

| Activity status | 0.135 | |||

| Active activities | 74.99 | 75.07 | 69.70 | |

| Non-active activities | 25.01 | 24.93 | 30.30 | |

| Hyperlipidemia | <0.001 | |||

| YES | 61.08 | 61.35 | 41.89 | |

| NO | 38.92 | 38.65 | 58.11 | |

| Diabetes | 0.152 | |||

| YES | 18.63 | 18.56 | 23.18 | |

| NO | 81.37 | 81.44 | 76.82 | |

| Hypertension | <0.001 | |||

| YES | 55.34 | 55.04 | 76.46 | |

| NO | 44.66 | 44.96 | 23.54 | |

| Myocardial infarct | <0.001 | |||

| YES | 5.33 | 5.22 | 12.65 | |

| NO | 94.67 | 94.78 | 87.35 | |

| CHD | <0.001 | |||

| YES | 6.19 | 5.99 | 20.41 | |

| NO | 93.81 | 94.01 | 79.59 | |

| CBC count,103/μL | ||||

| Lymphocyte count | 2.16 ± 3.09 | 2.17 ± 3.11 | 1.80 ± 0.64 | 0.156 |

| Neutrophils count | 4.41 ± 1.72 | 4.40 ± 1.72 | 4.61 ± 1.68 | 0.158 |

| Monocyte count | 0.60 ± 0.21 | 0.60 ± 0.21 | 0.66 ± 0.21 | <0.001 |

| Platelet count | 239.74 ± 62.69 | 240.11 ± 62.74 | 213.52 ± 53.31 | <0.001 |

| CBC-derived indicators | ||||

| SIRI | 1.40 ± 1.00 | 1.39 ± 0.99 | 2.00 ± 1.63 | <0.001 |

| MLR | 0.31 ± 0.14 | 0.31 ± 0.14 | 0.41 ± 0.23 | <0.001 |

| AISI | 339.60 ± 281.70 | 338.23 ± 279.45 | 435.87 ± 398.13 | <0.001 |

| NMLR | 2.61 ± 1.39 | 2.60 ± 1.38 | 3.32 ± 1.87 | <0.001 |

| NLR | 2.30 ± 1.2974 | 2.29 ± 1.29 | 2.91 ± 1.68 | <0.001 |

| PLR | 124.61 ± 50.61 | 124.49 ± 50.40 | 132.93 ± 63.07 | 0.044 |

| SII | 549.87 ± 352.59 | 548.80 ± 351.50 | 624.71 ± 415.57 | 0.009 |

Baseline characteristics of participants included in NHANES.

Data were n (%) or mean ± SD.

Relationship between atrial fibrillation and inflammatory markers in the NHANES

In Model 1, all the inflammation markers derived from complete blood cell count, namely SIRI, MLR, AISI,NMLR, NLR, PLR and SII, were positively correlated with AF, with OR values of 1.334 (95% CI: 1.199, 1.282; P < 0.001), 14.621 (95% CI: 6.802, 31.430; P < 0.001), 1.001 (95% CI: 1.000, 1.001; P = 0.001), 1.200 (95% CI: 1.124, 1.283; P < 0.001), 1.198 (95% CI: 1.118, 1.283; P < 0.001), 1.003 (95% CI: 0.999, 1.006; P < 0.001), and 1.000 (95% CI: 1.000, 1.001; P = 0.014), respectively. In Model 2 and 3, the correlations between SIRI and MLR and AF remained stable, with OR values of 1.158 (95% CI: 1.024, 1.310; P = 0.020), 1.147 (95% CI: 1.017, 1.294; P = 0.026) and 3.060 (95% CI: 1.258, 7.441; P = 0.014), 2.775 (95% CI: 1.163, 6.618; P = 0.021), respectively. However, in Model 2 and 3, AISI was not significantly correlated with AF, with OR values of 1.000 (95% CI: 0.999, 1.001; P = 0.175), 1.000 (95% CI: 1.000, 1.001; Moreover, the association results of NMLR, NLR, PLR, and SII were similar to AISI showing no significant correlation with AF (P > 0.05).When inflammation markers were categorized by tertiles, Model 1 showed that the middle SIRI tertile (Q2) and highest SIRI tertiles (Q3) had greater odds of AF than the lowest tertiles (Q1), with ORs of 2.072 (95% CI: 1.064, 4.033; P = 0.032) and 4.673 (95% CI: 2.548, 8.572; P < 0.001), respectively. In Models 2 and 3, the highest SIRI tertiles (Q3) remained positively associated with AF vs. Q1, with an OR of 2.345 (95% CI: 1.208, 4.554; P = 0.012). In Model 1, compared with the lowest MLR tertile (Q1), the middle MLR tertiles (Q2) and the highest MLR tertiles (Q3) were positively associated with AF, with ORs of 2.277 (95% CI: 1.040, 4.983; P = 0.039) and 5.477 (95% CI: 2.854, 10.509; P < 0.001), respectively. However, In Model 2 and Model 3, neither the middle MLR tertiles (Q2) nor the highest MLR tertiles (Q3) showed a significant association with AF (P > 0.05). The association patterns for AISI and MLR mirrored those observed for MLR. In Model 1, compared with the lowest tertile (Q1), the highest NLR tertiles (Q3) was positively associated with AF, with an OR of 3.165 (95% CI: 1.708, 5.87; P < 0.001). However, in Models 2 and 3, neither the middle NLR tertiles (Q2) nor the highest NLR tertiles (Q3) differed significantly from the lowest NLR tertiles (Q1) with respect to AF. The ORs were 1.200 (95% CI: 0.621, 2.321; P = 0.587), 1.138 (95% CI: 0.582, 2.227; P = 0.706), 1.615 (95% CI: 0.847, 3.076; P = 0.145), and 1.507 (95% CI: 0.787, 2.883; P = 0.216), respectively. The three NLR tertiles produced association results similar to those of NMLR. Across Models 1, 2, and 3, none of the three tertiles of PLR or SII was significantly associated with atrial fibrillation (P > 0.05) (Table 2).

Table 2

| Characteristics | Model1 | Model2 | Model3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P-Value | OR (95% CI) | P-Value | OR (95% CI) | P-Value | |

| SIRI (continuous) | 1.334 (1.199,1.484) | <0.001 | 1.158 (1.024,1.310) | 0.020 | 1.147 (1.017,1.294) | 0.026 |

| SIRI (tertiles) | ||||||

| Q1 (<0.860) | reference | reference | reference | |||

| Q2 (0.860∼1.429) | 2.072 (1.064,4.033) | 0.032 | 1.417 (0.712,2.818) | 0.321 | 1.367 (0.680,2.747) | 0.380 |

| Q3 (>1.429) | 4.673 (2.548,8.572) | <0.001 | 2.345 (1.208,4.554) | 0.012 | 2.182 (1.094,4.354) | 0.027 |

| P for trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| MLR (continuous) | 14.621 (6.802,31.430) | <0.001 | 3.060 (1.258,7.441) | 0.014 | 2.775 (1.163,6.618) | 0.021 |

| MLR (tertiles) | ||||||

| Q1 (<0.231) | reference | reference | reference | |||

| Q2 (0.231∼0.320) | 2.277 (1.040,4.983) | 0.039 | 1.506 (0.673,3.368) | 0.319 | 1.495 (0.676,3.304) | 0.321 |

| Q3 (>0.320) | 5.477 (2.854,10.509) | <0.001 | 2.004 (0.970,4.138) | 0.060 | 1.933 (0.936,3.991) | 0.075 |

| P for trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| AISI (continuous) | 1.001 (1.000,1.001) | 0.001 | 1.000 (0.999,1.001) | 0.175 | 1.000 (1.000,1.001) | 0.137 |

| AISI(tertiles) | ||||||

| Q1 (<191.546) | reference | reference | reference | |||

| Q2 (191.546∼340.979) | 1.963 (1.078,3.570) | 0.027 | 1.567 (0.839,2.924) | 0.158 | 1.563 (0.828,2.95) | 0.168 |

| Q3 (>340.979) | 2.409 (1.407,4.123) | 0.001 | 1.564 (0.892,2.742) | 0.118 | 1.523 (0.838,2.768) | 0.168 |

| P for trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| NMLR (continuous) | 1.200 (1.124,1.283) | <0.001 | 1.082 (0.998,1.173) | 0.057 | 1.077 (0.992,1.169) | 0.076 |

| NMLR (tertiles) | ||||||

| Q1 (<1.871) | reference | reference | reference | |||

| Q2 (1.871∼2.706) | 1.610 (0.836,3.100) | 0.155 | 1.200 (0.621,2.321) | 0.587 | 1.138 (0.582,2.227) | 0.706 |

| Q3 (>2.706) | 3.165 (1.708,5.87) | <0.001 | 1.615 (0.847,3.076) | 0.145 | 1.507 (0.787,2.883) | 0.216 |

| P for trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| NLR (continuous) | 1.198 (1.118,1.283) | <0.001 | 1.080 (0.991,1.176) | 0.077 | 1.076 (0.986,1.174) | 0.099 |

| NLR (tertiles) | ||||||

| Q1 (<1.625) | reference | reference | reference | |||

| Q2 (1.625∼2.385) | 1.545 (0.801,2.981) | 0.195 | 1.191 (0.613,2.315) | 0.606 | 1.141 (0.591,2.201) | 0.694 |

| Q3 (>2.385) | 2.851 (1.505,5.404) | 0.001 | 1.530 (0.785,2.981) | 0.212 | 1.427 (0.738,2.757) | 0.290 |

| P for trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| PLR (continuous) | 1.003 (0.999,1.006) | <0.001 | 1.000 (0.997,1.004) | 0.877 | 1.001 (0.997,1.00) | 0.755 |

| PLR (tertiles) | ||||||

| Q1 (<97.836) | reference | reference | reference | |||

| Q2 (97.836∼132.778) | 1.162 (0.671,2.014) | 0.593 | 1.152 (1.152,2.041) | 0.628 | 1.213 (0.689,2.135) | 0.504 |

| Q3 (>132.778) | 1.180 (0.714,1.948) | 0.519 | 0.876 (0.527,1.457) | 0.611 | 0.938 (0.562,1.566) | 0.806 |

| P for trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| SII (continuous) | 1.000 (1.000,1.001) | 0.014 | 1.000 (0.999,1.000) | 0.464 | 1.000 (1.000,1.001) | 0.407 |

| SII (tertiles) | ||||||

| Q1 (<368.412) | reference | reference | reference | |||

| Q2 (368.412∼569.625) | 0.894 (0.509,1.571) | 0.697 | 0.803 (0.454,1.420) | 0.451 | 0.804 (0.441,1.466) | 0.476 |

| Q3 (>569.625) | 1.545 (0.922,2.588) | 0.099 | 1.200 (0.705,2.043) | 0.502 | 1.205 (0.693,2.095) | 0.508 |

| P for trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

Logistic regression analysis on atrial fibrillation in NHANES.

OR Odds Ratio, CI Confidence Interval.

Model 1 was not adjusted for any confounders.

Model 2 was adjusted for gender, age, race and education level.

Model 3 was adjusted for gender, age, race,education level, BMI, activity status, smoke status, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarct, CHD.

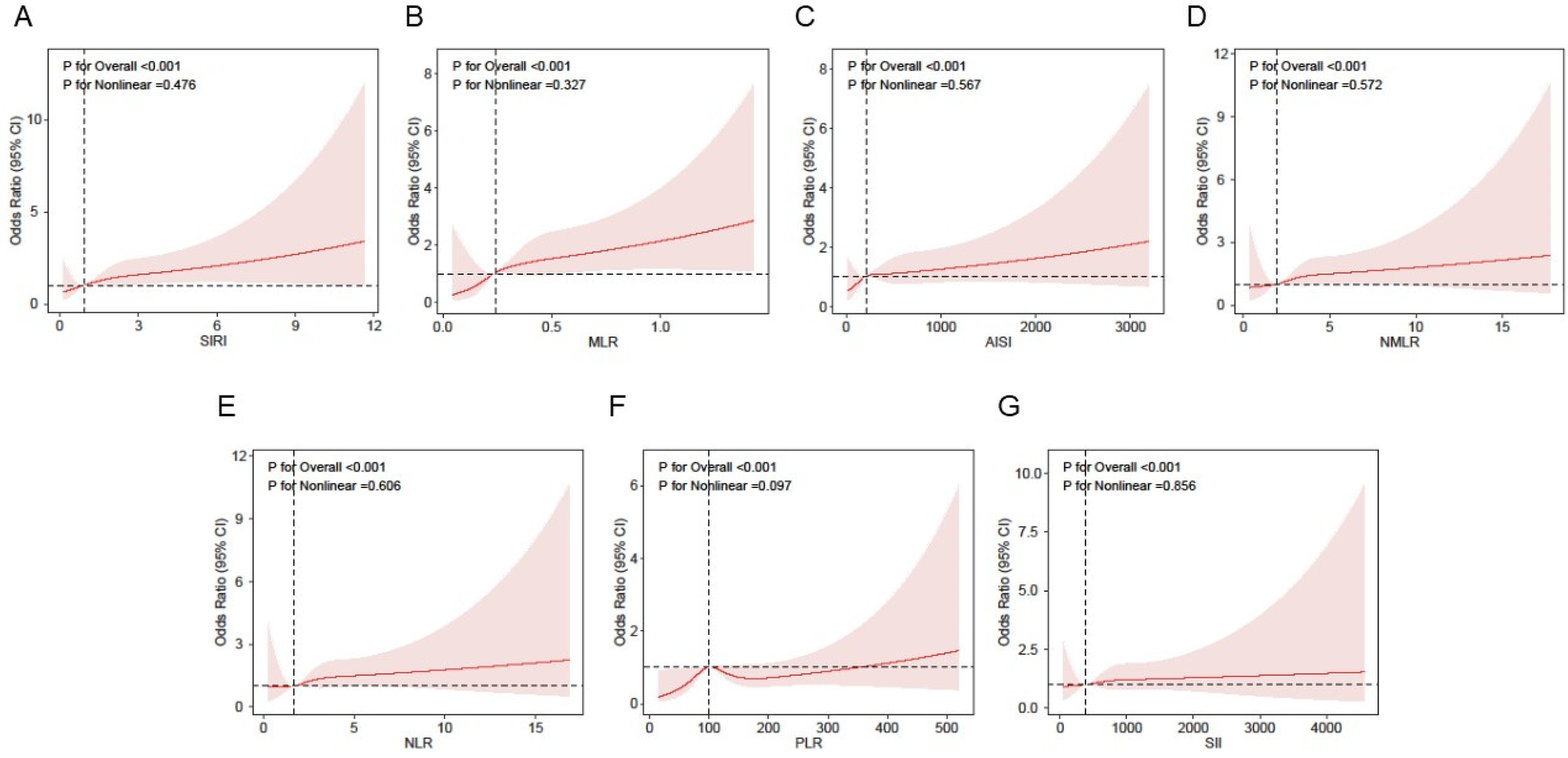

Nonlinearity analysis using RCS

Figure 2 presents RCS curves that further depict the association between inflammatory markers and atrial fibrillation. After adjusting for gender, age, race, education level, BMI, smoking status, activity status, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, coronary heart disease, and myocardial infarction, the adjusted results show a significant positive association between inflammatory markers and atrial fibrillation, with a linear increasing trend (P < 0.001;P for non-linear P > 0.05).

Figure 2

Association between inflammatory markers and AF using a restricted cubic spline regression model in NHANES. Adjusted for gender, age, race,education level, BMI, activity status, smoking status, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarct and CHD. (A) Association of SIRI with AF risk. (B) Association of MLR with AF risk. (C) Association of AISI with AF risk. (D) Association of NMLR with AF risk. (E) Association of NLR with AF risk. (F) Association of PLR with depression risk. (G) Association of SII with AF risk. SIRI, systemic inflammation response index; MLR, monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio; AISI, aggregate index of systemic inflammation; NMLR, neutrophil-monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio PLR, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio; SII, systemic inflammatory index.

The subgroup analysis and interaction test

To assess the robustness of the positive association between inflammatory markers and atrial fibrillation, we performed subgroup analyses by age (categorized), gender (categorized), race (Mexican American/Non-Hispanic White/Non-Hispanic Black/Other), BMI (categorized), hypertension (No, Yes), diabetes (No, Yes), and coronary heart disease (No, Yes). All covariates were included in each subgroup model except the stratification variable. We observed no significant interactions between inflammatory markers and any of these potential confounders (all P-value for interaction > 0.05) (Table 3).

Table 3

| Characteristics | SIRI | MLR | AISI | NMLR | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR(95%CI) | P-value | OR(95%CI) | P-value | OR(95%CI) | P-value | OR(95%CI) | P-value | |

| Gender, n (%) | ||||||||

| Male | 1.19 (1.07,1.32) | <0.001 | 4.76 (2.13,10.61) | <0.001 | 1.00 (1.00,1.00) | 0.041 | 1.16 (1.07,1.26) | <0.001 |

| Female | 1.25 (1.11,1.42) | <0.001 | 10.72 (3.99,28.83) | <0.001 | 1.00 (1.00,1.00) | 0.015 | 1.13 (1.02,1.24) | 0.016 |

| P-interaction | 0.642 | 0.343 | 0.605 | 0.521 | ||||

| Age, n (%) | ||||||||

| <65 | 1.22 (1.10,1.34) | <0.001 | 4.83 (2.40,9.73) | <0.001 | 1.00 (1.00,1.00) | 0.007 | 1.14 (1.06,1.22) | <0.001 |

| ≥65 | 0.95 (0.60,1.50) | 0.828 | 1.82 (0.12,26.66) | 0.661 | 1.00 (1.00,1.00) | 0.534 | 0.96 (0.68,1.37) | 0.831 |

| P-interaction | 0.372 | 0.809 | 0.302 | 0.458 | ||||

| Race, n (%) | ||||||||

| Mexican American | 1.34 (1.02,1.74) | 0.033 | 156.99 (11.24,2193.13) | <0.001 | 1.00 (1.00,1.00) | 0.335 | 1.20 (0.94,1.53) | 0.146 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 1.19 (1.08,1.31) | <0.001 | 4.69 (2.27,9.71) | <0.001 | 1.00 (1.00,1.00) | 0.053 | 1.13 (1.05,1.22) | <0.001 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1.09 (0.86,1.40) | 0.475 | 4.69 (2.27,9.71) | 0.487 | 1.00 (1.00,1.00) | 0.370 | 1.02 (0.75,1.37) | 0.920 |

| Others | 1.00 (0.45,2.20) | 0.997 | 16.51 (0.07,4095.58) | 0.319 | 1.00 (0.99,1.00) | 0.445 | 0.81 (0.28,2.33) | 0.694 |

| P-interaction | 0.830 | 0.110 | 0.833 | 0.777 | ||||

| BMI, n (%) | ||||||||

| <18.5 | 0.53 (0.03,10.34) | 0.679 | 7.94 (0.00,100489.56) | 0.667 | 1.00 (0.98,1.01) | 0.562 | 0.94 (0.17,5.30) | 0.948 |

| 18.5–24.9 | 1.13 (0.98,1.31) | 0.099 | 4.13 (0.84,20.43) | 0.082 | 1.00 (1.00,1.00) | 0.257 | 1.09 (0.94,1.28) | 0.251 |

| 25–29.9 | 1.22 (1.08,1.39) | 0.002 | 4.73 (1.97,11.31) | <0.001 | 1.00 (1.00,1.00) | 0.015 | 1.12 (1.03,1.23) | 0.009 |

| ≥30.0 | 1.31 (1.15,1.50) | <0.001 | 16.97 (5.98,48.15) | <0.001 | 1.00 (1.00,1.00) | 0.132 | 1.23 (1.11,1.36) | <0.001 |

| P-interaction | 0.264 | 0.345 | 0.439 | 0.306 | ||||

| Diabetes, n (%) | ||||||||

| NO | 1.20 (1.09,1.31) | <0.001 | 8.14 (4.00,16.56) | <0.001 | 1.00 (1.00,1.00) | 0.033 | 1.14 (1.07,1.23) | <0.001 |

| YES | 1.27 (1.09,1.48) | 0.002 | 4.92 (1.50,16.13) | 0.008 | 1.00 (1.00,1.00) | 0.053 | 1.17 (1.03,1.33) | 0.017 |

| P-interaction | 0.572 | 0.266 | 0.848 | 0.899 | ||||

| Hypertension, n (%) | ||||||||

| NO | 1.16 (1.00,1.35) | 0.053 | 5.26 (1.64,16.86) | 0.005 | 1.00 (1.00,1.00) | 0.297 | 1.10 (0.98,1.24) | 0.117 |

| YES | 1.22 (1.11,1.33) | <0.001 | 6.74 (3.26,13.94) | <0.001 | 1.00 (1.00,1.00) | 0.011 | 1.16 (1.08,1.25) | <0.001 |

| P-interaction | 0.920 | 0.919 | 0.965 | 0.742 | ||||

| CHD, n (%) | ||||||||

| NO | 1.22 (1.12,1.32) | <0.001 | 7.30 (3.79,14.06) | <0.001 | 1.00 (1.00,1.00) | 0.005 | 1.17 (1.09,1.25) | <0.001 |

| YES | 1.18 (0.95,1.47) | 0.140 | 3.48 (0.55,22.02) | 0.186 | 1.00 (1.00,1.00) | 0.285 | 1.04 (0.87,1.24) | 0.675 |

| P-interaction | 0.665 | 0.339 | 0.984 | 0.112 | ||||

| Characteristics | NLR | PLR | SII | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR(95%CI) | P-value | OR(95%CI) | P-value | OR(95%CI) | P-value | |

| Gender, n (%) | ||||||

| Male | 1.17 (1.07,1.28) | <0.001 | 1.00 (1.00,1.01) | 0.264 | 1.00 (1.00,1.00) | 0.052 |

| Female | 1.12 (1.01,1.25) | 0.038 | 1.00 (1.00,1.00) | 0.955 | 1.00 (1.00,1.00) | 0.542 |

| P-interaction | 0.470 | 0.416 | 0.455 | |||

| Age, n (%) | ||||||

| <65 | 1.14 (1.05,1.23) | 0.001 | 1.00 (1.00,1.00) | 0.583 | 1.00 (1.00,1.00) | 0.063 |

| ≥65 | 0.95 (0.64,1.40) | 0.784 | 1.00 (0.99,1.01) | 0.450 | 1.00 (1.00,1.00) | 0.355 |

| P-interaction | 0.445 | 0.365 | 0.175 | |||

| Race, n (%) | ||||||

| Mexican American | 1.18 (0.89,1.57) | 0.236 | 1.00 (0.99,1.01) | 0.749 | 1.00 (1.00,1.00) | 0.925 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 1.14 (1.05,1.23) | 0.002 | 1.00 (1.00,1.00) | 0.719 | 1.00 (1.00,1.00) | 0.208 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1.01 (0.71,1.43) | 0.975 | 1.00 (0.99,1.01) | 0.914 | 1.00 (1.00,1.00) | 0.801 |

| Others | 0.71 (0.20,2.50) | 0.59 | 0.97 (0.94,1.01) | 0.170 | 1.00 (0.99,1.00) | 0.148 |

| P-interaction | 0.776 | 0.324 | 0.408 | |||

| BMI, n (%) | ||||||

| <18.5 | 0.86 (0.12,6.19) | 0.885 | 1.03 (0.99,1.08) | 0.180 | 1.00 (0.99,1.01) | 0.720 |

| 18.5–24.9 | 1.10 (0.92,1.30) | 0.291 | 1.00 (0.99,1.01) | 0.543 | 1.00 (1.00,1.00) | 0.770 |

| 25–29.9 | 1.13 (1.02,1.24) | 0.015 | 1.00 (1.00,1.01) | 0.158 | 1.00 (1.00,1.00) | 0.079 |

| ≥30.0 | 1.23 (1.10,1.37) | <0.001 | 1.00 (1.00,1.00) | 0.992 | 1.00 (1.00,1.00) | 0.342 |

| P-interaction | 0.315 | 0.517 | 0.503 | |||

| Diabetes, n (%) | ||||||

| NO | 1.15 (1.06,1.23) | <0.001 | 1.00 (1.00,1.00) | 0.525 | 1.00 (1.00,1.00) | 0.241 |

| YES | 1.18 (1.02,1.35) | 0.024 | 1.00 (1.00,1.01) | 0.732 | 1.00 (1.00,1.00) | 0.125 |

| P-interaction | 0.878 | 0.873 | 0.532 | |||

| Hypertension, n (%) | ||||||

| NO | 1.10 (0.96,1.26) | 0.160 | 1.00 (1.00,1.01) | 0.770 | 1.00 (1.00,1.00) | 0.640 |

| YES | 1.16 (1.07,1.26) | <0.001 | 1.00 (1.00,1.00) | 0.569 | 1.00 (1.00,1.00) | 0.098 |

| P-interaction | 0.758 | 0.844 | 0.819 | |||

| CHD, n (%) | ||||||

| NO | 1.17 (1.09,1.26) | <0.001 | 1.00 (1.00,1.00) | 0.217 | 1.00 (1.00,1.00) | 0.036 |

| YES | 1.03 (0.85,1.25) | 0.752 | 1.00 (0.99,1.00) | 0.620 | 1.00 (1.00,1.00) | 0.992 |

| P-interaction | 0.114 | 0.233 | 0.355 | |||

Subgroup analysis for the association between inflammatory markers and AF.

The model was adjusted for gender(categorical),age (categorical), race (Mexican American/non-Hispanic White/non-Hispanic Black/other races), BMI (categorical), Hypertension(No, Yes),Diabetes (No, Yes), and CHD(No, Yes). All covariates in the subgroup analysis models were adjusted, excepting the stratification variable itself.

Relationship between AF and inflammation markers

Our results show a significant association between higher SIRI and greater odds of AF. Model I reported an OR of 1.112 (95% CI 1.070,1.156; P < 0.001). Model II likewise showed a significant association (OR: 1.088; 95% CI 1.045,1.132; P < 0.001). In Model III the association persisted (OR: 1.081; 95% CI 1.038,1.127; P < 0.001). In a sensitivity analysis treating SIRI as a categorical variable, participants in the highest tertile had a 43.6% increased risk of AF compared with those in the lowest tertile (OR: 1.436; 95% CI 1.248,1.652; P < 0.001) (Table 4).

Table 4

| Characteristics | Model Ⅰ | Model Ⅱ | Model Ⅲ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P-Value | OR (95% CI) | P-Value | OR (95% CI) | P-Value | |

| SIRI (continuous) | 1.112 (1.070,1.156) | <0.001 | 1.088 (1.045,1.132) | <0.001 | 1.081 (1.038,1.127) | <0.001 |

| SIRI (tertiles) | ||||||

| Q1 (<0.653) | reference | reference | reference | |||

| Q2 (0.653∼1.063) | 1.807 (1.586,2.058) | <0.001 | 1.663 (1.456,1.899) | <0.001 | 1.664 (1.456,1.902) | <0.001 |

| Q3 (>1.063) | 1.656 (1.451,1.890) | <0.001 | 1.451 (1.263,1.666) | <0.001 | 1.436 (1.248,1.652) | <0.001 |

| P for trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

Logistic regression analysis on atrial fibrillation.

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Model Ⅰ was not adjusted for any confounders.

Model Ⅱ was adjusted for gender, age, BMI, hypertension and diabetes.

Model Ⅲ was adjusted for gender, age, BMI, hypertension, diabetes, ALT, AST, TC, TG, LDLC, HDLC, GLU, Serum uric acid concentration, serum creatinine level.

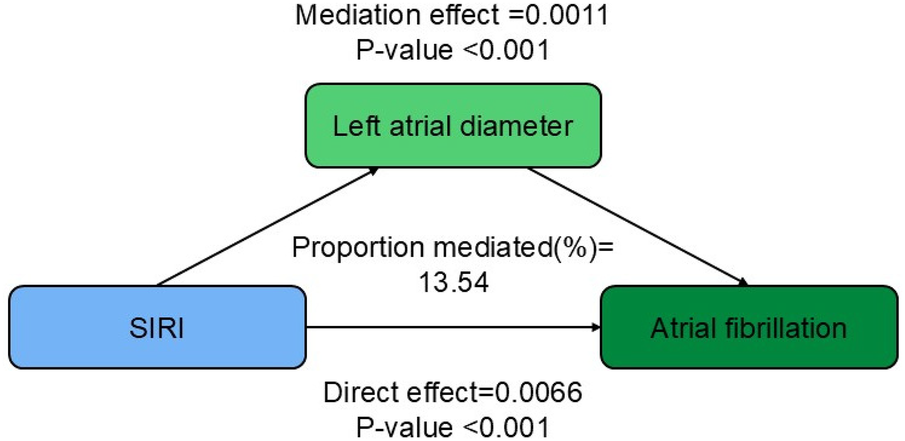

Mediation analysis

The mediation analysis shown in Figure 3 indicates that an increase in SIRI is consistently associated with a higher risk of AF, even after adjusting for covariates. The results further indicate that part of this association is mediated by left atrial diameter, with a mediation proportion of 13.54% (P < 0.001).

Figure 3

Path diagram of the mediation analysis of left atrial diameter on the relationship between SIRI and AF.

Discussion

This cross-sectional study included 10,474 eligible participants from NHANES and 13,706 eligible participants from Zibo Central Hospital. We examined the association between inflammatory markers derived from complete blood cell counts and AF. After adjusting for multiple covariates, SIRI showed a statistically significant positive association with AF, indicating that higher SIRI correlates with greater AF risk. Restricted cubic spline analysis revealed a linear dose–response relationship between these inflammatory markers and AF risk. Interaction tests and subgroup analyses stratified by selected clinical parameters and comorbidities found no significant interactions. Notably, left atrial diameter partially mediated the association between SIRI and AF.

Inflammation is closely linked to the onset and persistence of atrial fibrillation. Inflammatory mediators produced by mononuclear macrophages, such as TNF-α and IL-6, promote atrial myocyte degeneration and fibrosis and slow conduction, thereby contributing to both structural and electrical remodeling that can initiate and sustain atrial fibrillation (4, 7). Conversely, in patients with atrial fibrillation the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) is activated because of reduced cardiac function and hypertension (24). Ang II enhances neutrophil recruitment and stimulates secretion of inflammatory cytokines including IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α (25). This establishes a vicious cycle in which left atrial diameter, a key structural marker, is tightly associated with inflammation and with atrial fibrillation. Atrial fibrillation produces abnormal atrial electrical activity that impairs systolic and diastolic function and, over time, leads to atrial enlargement; left atrial enlargement in turn is an important risk factor for atrial fibrillation. Notably, plasma concentrations of inflammatory markers such as IL-6 correlate positively with LA diameter (12, 13), indicating that inflammation may exacerbate AF progression by promoting atrial structural remodeling, particularly left atrial enlargement. In recent years, inflammatory indices derived from whole blood cells (e.g., SIRI, MLR, AISI, NMLR, NLR, PLR, and SII) have emerged as robust biomarkers across diverse diseases (26–31). Among these, the systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) outperforms many conventional markers in predicting disease progression and evaluating clinical outcomes, a finding supported by multicenter data. In patients with coronary heart disease, SIRI correlates strongly with disease severity (32, 33). Studies across varied populations indicate that SIRI can stratify atrial fibrillation risk and inform individualized management, offering a practical tool for early identification of high-risk individuals (21, 34). Other work links SIRI to cardiovascular and all-cause mortality, underscoring the role of systemic inflammation in prevention strategies (20). Finally, in acute coronary syndrome, higher post–percutaneous coronary intervention SIRI predicts increased risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) (26, 35).

In the baseline characteristics, patients with atrial fibrillation had a significantly higher mean body mass index (BMI) than those without atrial fibrillation, indicating that obesity may be an important risk factor for the onset and progression of atrial fibrillation. This finding aligns with extensive epidemiological evidence showing that obesity is independently associated with the incidence and prevalence of atrial fibrillation (36). Epicardial adipose tissue (EAT), a specialized fat depot located between the myocardial surface and the visceral pericardium, has recently emerged as a key mediator linking obesity to atrial fibrillation, particularly by promoting atrial remodeling through inflammatory mechanisms. In obesity, EAT volume increases markedly, and the inflammatory mediators it secretes can drive atrial structural remodeling by multiple pathways. Systemically, obesity provokes a proinflammatory state that amplifies EAT inflammatory activity, leading to left atrial fibrosis and chamber enlargement and thereby facilitating atrial fibrillation (37). Local changes also contribute: in human and sheep models of atrial fibrillation, subepicardial adipose tissue shows thickening and fibrotic infiltration (38); these changes reinforce one another and create a vicious cycle. Research indicates that patients with elevated SIRI have significantly greater volumes of EAT (39, 40). Moreover, EAT mediates the relationship between SIRI and myocardial fibrosis, implying that systemic inflammation can exacerbate myocardial fibrosis indirectly by altering EAT function. Goette et al. identified left atrial fibrosis and enlargement of the inner diameter as core structural remodeling features of ACM that directly increase AF risk (41). Pierucci et al. elucidated the inflammatory mechanisms associated with ACM and highlighted the pro-inflammatory role of EAT. EAT releases pro-inflammatory factors that facilitate local inflammatory infiltration and atrial fibrosis, thereby contributing to the onset and persistence of atrial fibrillation (42).

Atrial structural and electrical remodeling constitute key pathophysiological substrates for AF. Atrial fibrosis, a hallmark of structural remodeling, disrupts local electrical coupling, facilitates reentrant circuits and regional conduction block, and thereby creates a substrate for AF. The heart's dense autonomic innervation—sympathetic, parasympathetic, and intrinsic cardiac ganglia—exerts a major influence on atrial electrophysiology and arrhythmogenesis. Interventions that reduce autonomic innervation or activation lower the incidence of atrial arrhythmias, indicating that autonomic modulation can help prevent AF (43). Clinically, atrial enlargement predicts AF development. Cardiac magnetic resonance, speckle-tracking echocardiography, electroanatomic voltage mapping, and circulating biomarkers permit quantitative assessment of myocardial fibrosis and inform treatment decisions and recurrence risk in patients with AF. Underlying heart diseases (such as hypertension, valvular heart disease, and heart failure) can exacerbate atrial fibrosis through multiple mechanisms. Chronic pressure or volume overload raises atrial wall tension and activates mechanosensitive signaling pathways, which upregulate pro-fibrotic gene expression. Activation of neuroendocrine systems, such as the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, further promotes inflammation and fibrotic remodeling.

This study indicates that the association between SIRI and AF risk is partly mediated by left atrial diameter, reinforcing the link between inflammation and atrial remodeling in atrial fibrillation pathogenesis. This discovery holds potential implications for clinical practice, especially for the selection of ablation treatment strategies for atrial fibrillation. For assessing the level of systemic inflammation, it may help identify those patient groups with more active atrial remodeling, who may face a higher risk of recurrence after ablation due to persistent structural and electrical remodeling. Prior work shows that pre-ablation SII predicts recurrence after cryoballoon ablation (44), and that an increased NLR on day 1 after radiofrequency catheter ablation independently predicts early recurrence (≤3 months) in atrial fibrillation patients (45). Different ablation modalities also appear to differentially affect the inflammatory milieu; for example, radiofrequency catheter ablation may elicit greater inflammation than cryoballoon ablation (46). Future studies should test whether inflammatory markers can guide individualized selection of ablation technique or timing to improve procedural success and reduce recurrence.

Several anti-inflammatory strategies show promise in cardiovascular disease. Colchicine, a recognized anti-inflammatory agent, has demonstrated mechanistic effects in atrial fibrillation in animal studies (47), including inhibition of IL-6 release triggered by IL-1β, attenuation of subsequent atrial fibrosis, and modulation of ion channel gene expression and signaling pathways. These findings indicate potential utility for inflammation-driven arrhythmias. Corticosteroids have been used in inflammatory cardiomyopathy despite dose-limiting side effects, and targeted study of an AF subpopulation with clear systemic inflammation may be warranted (48). More selective approaches include biological agents such as IL-6 inhibitors, which are approved for autoimmune diseases. Current evidence shows that tocilizumab significantly reduces new-onset atrial fibrillation in patients with severe COVID-19 (49). Given IL-6's role in atrial remodeling and its association with left atrial enlargement, IL-6 blockade may offer a novel strategy to diminish atrial inflammatory matrix and slow progression of atrial fibrillation.

This study is the first to comprehensively evaluate the association between whole blood count–derived inflammatory markers and atrial fibrillation (AF) using large-scale population data from NHANES and inpatient records from Zibo Central Hospital, and to validate SIRI as a novel, readily available inflammatory predictor of AF. The left atrial diameter partially mediates the relationship between SIRI and AF risk. Although the data lack information on specific AF etiologies, which may account for some heterogeneity of results across AF subtypes, we consistently observed lower lymphocyte counts and higher SIRI values in patients with AF compared with non-AF patients, suggesting a link between AF onset and systemic inflammation. These findings introduce additional inflammatory metrics for AF risk stratification. We recommend incorporating CBC-derived inflammatory markers, particularly SIRI, into AF risk assessment frameworks to improve monitoring of inflammatory status and support earlier intervention in high-risk individuals.

This study is the first to suggest SIRI as a novel and readily available inflammatory marker that is significantly associated with AF risk in large population data, with left atrial diameter acting as a partial mediator. These findings provide a new inflammatory marker for risk stratification of AF; It provides a basis for screening and early intervention of AF high-risk population. Although this study had a cross-sectional design and causality cannot be inferred, the results provide an important foundation for future prospective intervention studies. We suggest that CBC-derived inflammatory markers, especially SIRI, should be included in the AF risk assessment system, and the monitoring and management of inflammatory states should be strengthened in clinical practice. This study has several important limitations. First, the cross-sectional design precludes the determination of causal directions, necessitating consideration of the potential for reverse causality. The observed elevation in inflammatory markers may indicate a consequence of atrial fibrillation rather than its etiology, or there may exist a mutually reinforcing cycle between the two. Future research should focus on elucidating causal sequences through longitudinal cohort studies or interventional experimental designs. Second, AF was ascertained exclusively by ICD codes and self-report, which may introduce misclassification bias when asymptomatic or paroxysmal cases are common. Third, inflammatory markers were measured once, so intra-individual variability is not captured and the uncertainty in association estimates is increased. Fourth, although multiple covariates were adjusted for residual confounding remains possible. The dataset lacks some potentially important confounders, including specific use of statins, corticosteroids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and anticoagulants, which can directly influence inflammation and atrial fibrillation risk. In addition, NHANES does not include canonical inflammatory markers such as IL-6 and TNF-α, limiting deeper exploration of inflammatory pathways. This study used the anteroposterior diameter of the left atrium (LAD) to represent left atrial size and examined its potential mediating role between systemic inflammation and atrial fibrillation. Although left atrial volume (LAV) is considered a more comprehensive and accurate measure of left atrial structure, we selected left atrial diameter (LAD) in this study for the following reasons. First, in routine echocardiographic practice, LAD is more widely available and standardized. Second, prior studies have established an association between LAD and atrial fibrillation risk. We acknowledge, however, that LAD as a linear metric may not fully capture geometric remodeling or functional change of the left atrium. Incorporating three-dimensional measures such as LAV in future studies would better delineate the pathological link between inflammation and atrial structural changes. Finally, our hospital dataset derives from a retrospective clinical diagnosis and treatment database. In routine practice, particularly when screening and managing large, heterogeneous inpatient populations, the scope of cardiac ultrasound is often constrained by clinical indications, available resources, and documentation practices. The database primarily contains basic echocardiographic parameters, such as the left atrial anteroposterior diameter (LAD) used in this study. More refined measures—left atrial volume index (LAVI), tissue Doppler–derived diastolic indices (e.g., E/e'), estimated pulmonary artery systolic pressure (PASP), and left ventricular global longitudinal strain (GLS)—which offer greater pathophysiological discrimination, are recorded far less frequently in our dataset. As a result, large-scale, statistically robust analyses of these variables are not feasible. In the NHANES and Zibo Central Hospital cohorts, we adjusted for multiple cardiovascular risk factors and comorbidities. However, the extremely small number of young atrial fibrillation cases precluded a subgroup analysis focused on the young population. Consequently, this study cannot provide specific risk estimates for that subgroup. These limitations indicate that our conclusions require confirmation in more rigorous prospective studies that incorporate precise electrocardiographic diagnosis, a panel of biomarkers, and more comprehensive medication data. Overall, this study supplies population-based cross-sectional evidence supporting the inflammatory hypothesis of atrial fibrillation and establishes a hypothesis-generating foundation for future mechanistic and clinical research.

Conclusion

The results showed that SIRI was significantly and positively associated with increased risk of AF, and further mediation analysis suggested that left atrial diameter enlargement was a potential mediating pathway in this association. However, it is necessary to further explore the causal relationship between these inflammatory markers and AF in the future.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the ethics review board of the National Center for Health Statisticsthe Medical Ethics Expert Committee of Zibo Central Hospital. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

DW: Writing – original draft. GZ: Writing – review & editing. JL: Writing – review & editing. YX: Writing – review & editing. HL: Writing – review & editing. BL: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This study was supported by Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (grant numbers: ZR2023MH136). Taishan Scholars Program of Shandong Province tsqn, China (NO.tsqn202306402). China Association of Chinese Medicine scientific research project (2024HH-010).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the participants and staff of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey and the National Center for Environmental Health for their valuable contributions.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcvm.2025.1724217/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Andrade J Khairy P Dobrev D Nattel S . The clinical profile and pathophysiology of atrial fibrillation: relationships among clinical features, epidemiology, and mechanisms. Circ Res. (2014) 114(9):1453–68. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.303211

2.

Nattel S Dobrev D . Electrophysiological and molecular mechanisms of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Nat Rev Cardiol. (2016) 13(10):575–90. 10.1038/nrcardio.2016.118

3.

Hindricks G Potpara T Dagres N Arbelo E Bax JJ Blomström-Lundqvist C et al 2020 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European association for cardio-thoracic surgery (EACTS): the task force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the european society of cardiology (ESC) developed with the special contribution of the european heart rhythm association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. (2021) 42(5):373–498. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa612

4.

Liew R Khairunnisa K Gu Y Tee N Yin NO Naylynn TM et al Role of tumor necrosis factor-α in the pathogenesis of atrial fibrosis and development of an arrhythmogenic substrate. Circ J Off J Jpn Circ Soc. (2013) 77(5):1171–9. 10.1253/circj.CJ-12-1155

5.

Monnerat G Alarcón ML Vasconcellos LR Hochman-Mendez C Brasil G Bassani RA et al Macrophage-dependent IL-1β production induces cardiac arrhythmias in diabetic mice. Nat Commun. (2016) 7:13344. 10.1038/ncomms13344

6.

Sawaya SE Rajawat YS Rami TG Szalai G Price RL Sivasubramanian N et al Downregulation of connexin40 and increased prevalence of atrial arrhythmias in transgenic mice with cardiac-restricted overexpression of tumor necrosis factor. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. (2007) 292(3):H1561–1567. 10.1152/ajpheart.00285.2006

7.

Harada M Van Wagoner DR Nattel S . Role of inflammation in atrial fibrillation pathophysiology and management. Circ J Off J Jpn Circ Soc. (2015) 79(3):495–502. 10.1253/circj.CJ-15-0138

8.

Rudolph V Andrié RP Rudolph TK Friedrichs K Klinke A Hirsch-Hoffmann B et al Myeloperoxidase acts as a profibrotic mediator of atrial fibrillation. Nat Med. (2010) 16(4):470–4. 10.1038/nm.2124

9.

Cabaro S Conte M Moschetta D Petraglia L Valerio V Romano S et al Epicardial adipose tissue-derived IL-1β triggers postoperative atrial fibrillation. Front Cell Dev Biol. (2022) 10:893729. 10.3389/fcell.2022.893729

10.

Hu YF Chen YJ Lin YJ Chen SA . Inflammation and the pathogenesis of atrial fibrillation. Nat Rev Cardiol. (2015) 12(4):230–43. 10.1038/nrcardio.2015.2

11.

Liu Y Lv H Tan R An X Niu XH Liu YJ et al Platelets promote ang II (angiotensin II)-induced atrial fibrillation by releasing TGF-β1 (transforming growth factor-β1) and interacting with fibroblasts. Hypertens Dallas Tex 1979. (2020) 76(6):1856–67. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.15016

12.

Psychari SN Apostolou TS Sinos L Hamodraka E Liakos G Kremastinos DT . Relation of elevated C-reactive protein and interleukin-6 levels to left atrial size and duration of episodes in patients with atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. (2005) 95(6):764–7. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.11.032

13.

Hazarapetyan L Zelveian PH Grigoryan S . Inflammation and coagulation are two interconnected pathophysiological pathways in atrial fibrillation pathogenesis. J Inflamm Res. (2023) 16:4967–75. 10.2147/JIR.S429892

14.

Tokgoz S Kayrak M Akpinar Z Seyithanoğlu A Güney F Yürüten B . Neutrophil lymphocyte ratio as a predictor of stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis Off J Natl Stroke Assoc. (2013) 22(7):1169–74. 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2013.01.011

15.

Kaya H Ertaş F Soydinç MS . Association between neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio and severity of coronary artery disease. Clin Appl Thromb Off J Int Acad Clin Appl Thromb. (2014) 20(2):221. 10.1177/1076029613499821

16.

Horne BD Anderson JL John JM Weaver A Bair TL Jensen KR et al Which white blood cell subtypes predict increased cardiovascular risk? J Am Coll Cardiol. (2005) 45(10):1638–43. 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.02.054

17.

Hu B Yang XR Xu Y Sun YF Sun C Guo W et al Systemic immune-inflammation index predicts prognosis of patients after curative resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res Off J Am Assoc Cancer Res. (2014) 20(23):6212–22. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0442

18.

Qi Q Zhuang L Shen Y Geng Y Yu S Chen H et al A novel systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) for predicting the survival of patients with pancreatic cancer after chemotherapy. Cancer. (2016) 122(14):2158–67. 10.1002/cncr.30057

19.

Dziedzic EA Gąsior JS Tuzimek A Paleczny J Junka A Dąbrowski M et al Investigation of the associations of novel inflammatory biomarkers-systemic inflammatory index (SII) and systemic inflammatory response index (SIRI)-with the severity of coronary artery disease and acute coronary syndrome occurrence. Int J Mol Sci. (2022) 23(17):9553. 10.3390/ijms23179553

20.

Xia Y Xia C Wu L Li Z Li H Zhang J . Systemic immune inflammation index (SII), system inflammation response index (SIRI) and risk of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality: a 20-year follow-up cohort study of 42,875 US adults. J Clin Med. (2023) 12(3):1128. 10.3390/jcm12031128

21.

Lin KB Fan FH Cai MQ Yu Y Fu CL Ding LY et al Systemic immune inflammation index and system inflammation response index are potential biomarkers of atrial fibrillation among the patients presenting with ischemic stroke. Eur J Med Res. (2022) 27(1):106. 10.1186/s40001-022-00733-9

22.

Zhao X Huang L Hu J Jin N Hong J Chen X . The association between systemic inflammation markers and paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. (2024) 24(1):334. 10.1186/s12872-024-04004-9

23.

Gu XH Li W Li H Guo X He J Liu Y et al β-blockades and the risk of atrial fibrillation in patients with cardiovascular diseases. Front Pharmacol. (2024) 15:1418465. 10.3389/fphar.2024.1418465

24.

De Jong AM Maass AH Oberdorf-Maass SU Van Veldhuisen DJ Van Gilst WH Van Gelder IC . Mechanisms of atrial structural changes caused by stretch occurring before and during early atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc Res. (2011) 89(4):754–65. 10.1093/cvr/cvq357

25.

Friedrichs K Adam M Remane L Mollenhauer M Rudolph V Rudolph TK et al Induction of atrial fibrillation by neutrophils critically depends on CD11b/CD18 integrins. PLoS One. (2014) 9(2):e89307. 10.1371/journal.pone.0089307

26.

Fan W Wei C Liu Y Sun Q Tian Y Wang X et al The prognostic value of hematologic inflammatory markers in patients with acute coronary syndrome undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Clin Appl Thromb Off J Int Acad Clin Appl Thromb. (2022) 28:10760296221146183. 10.1177/10760296221146183

27.

Zhai G Liu Y Wang J Zhou Y . Association of monocyte-lymphocyte ratio with in-hospital mortality in cardiac intensive care unit patients. Int Immunopharmacol. (2021) 96:107736. 10.1016/j.intimp.2021.107736

28.

Wang Q Zhong W Xiao Y Lin G Lu J Xu L et al Pan-immune-inflammation value predicts immunotherapy response and reflects local antitumor immune response in rectal cancer. Cancer Sci. (2025) 116(2):350–66. 10.1111/cas.16400

29.

Li Y Ge S Liu J Li R Zhang R Wang J et al Peripheral blood NMLR can predict 5-year all-cause mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. (2025) 20:95–105. 10.2147/COPD.S488877

30.

Templeton AJ McNamara MG Šeruga B Vera-Badillo FE Aneja P Ocaña A et al Prognostic role of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in solid tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. (2014) 106(6):dju124. 10.1093/jnci/dju124

31.

Templeton AJ Ace O McNamara MG Al-Mubarak M Vera-Badillo FE Hermanns T et al Prognostic role of platelet to lymphocyte ratio in solid tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev Publ Am Assoc Cancer Res Cosponsored Am Soc Prev Oncol. (2014) 23(7):1204–12. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-0146

32.

Chen W He Y Xie C Yang R Liu Y Li L et al Association of systemic inflammatory response index (SIRI) with severity of coronary artery disease in patients with coronary heart disease: a CSCD-TCM plus study. Angiology. (2025) 20:33197251390178. 10.1177/00033197251390178

33.

He T Luo Y Wan J Hou L Su K Zhao J et al Analysis of the correlation between the systemic inflammatory response index and the severity of coronary vasculopathy. Biomol Biomed. (2024) 24(6):1726–34. 10.17305/bb.2024.10747

34.

Xu H Li T Yang M Zheng Y Zhu X Chen L et al Association between systemic inflammation response index and atrial fibrillation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a multicenter cross-sectional study. Front Med. (2025) 12:1666658. 10.3389/fmed.2025.1666658

35.

Han K Shi D Yang L Wang Z Li Y Gao F et al Prognostic value of systemic inflammatory response index in patients with acute coronary syndrome undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Ann Med. (2022) 54(1):1667–77. 10.1080/07853890.2022.2083671

36.

Middeldorp ME Kamsani SH Sanders P . Obesity and atrial fibrillation: prevalence, pathogenesis, and prognosis. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. (2023) 78:34–42. 10.1016/j.pcad.2023.04.010

37.

Poggi AL Gaborit B Schindler TH Liberale L Montecucco F Carbone F . Epicardial fat and atrial fibrillation: the perils of atrial failure. Eur Eur Pacing Arrhythm Card Electrophysiol J Work Groups Card Pacing Arrhythm Card Cell Electrophysiol Eur Soc Cardiol. (2022) 24(8):1201–12. 10.1093/europace/euac015

38.

Haemers P Hamdi H Guedj K Suffee N Farahmand P Popovic N et al Atrial fibrillation is associated with the fibrotic remodelling of adipose tissue in the subepicardium of human and sheep atria. Eur Heart J. (2017) 38(1):53–61. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv625

39.

Wang W Zhu R Wang W Gao Y Liu J Wu L et al The relationship between myocardial fibrosis in hypertensive patients with preserved ejection fraction and the severity of systemic inflammatory status is mediated by epicardial adipose tissue: a multicenter cohort study. J Clin Hypertens Greenwich Conn. (2025) 27(11):e70182. 10.1111/jch.70182

40.

Zhu R Wang W Gao Y Li B Wang W Liu J et al Chronic inflammation in patients with chronic coronary syndrome who have been taking lipid-lowering drugs as a residual risk factor - a bidirectional synergistic correlation with epicardial adipose tissue. J Inflamm Res. (2025) 18:16531–44. 10.2147/JIR.S571886

41.

Goette A Corradi D Dobrev D Aguinaga L Cabrera JA Chugh SS et al Atrial cardiomyopathy revisited-evolution of a concept: a clinical consensus statement of the European heart rhythm association (EHRA) of the ESC, the heart rhythm society (HRS), the Asian Pacific heart rhythm society (APHRS), and the Latin American heart rhythm society (LAHRS). Eur Eur Pacing Arrhythm Card Electrophysiol J Work Groups Card Pacing Arrhythm Card Cell Electrophysiol Eur Soc Cardiol. (2024) 26(9):euae204. 10.1093/europace/euae204

42.

Pierucci N Mariani MV Iannetti G Maffei L Coluccio A Laviola D et al Atrial cardiomyopathy: new pathophysiological and clinical aspects. Minerva Cardiol Angiol. (2025) 23:2. 10.23736/S2724-5683.25.06725-0

43.

Wang S Zhou X Huang B Wang Z Zhou L Chen M et al Spinal cord stimulation suppresses atrial fibrillation by inhibiting autonomic remodeling. Heart Rhythm. (2016) 13(1):274–81. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.08.018

44.

Kaplan E Ekızler FA Saribaş H Tak BT Cay S Korkmaz A et al Effectiveness of the systemic immune inflammation index to predict atrial fibrillation recurrence after cryoablation. Biomark Med. (2023) 17(2):101–9. 10.2217/bmm-2022-0515

45.

Im SI Shin SY Na JO Kim YH Choi CU Kim SH et al Usefulness of neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio in predicting early recurrence after radiofrequency catheter ablation in patients with atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol. (2013) 168(4):4398–400. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.05.042

46.

Yano M Egami Y Yanagawa K Nakamura H Matsuhiro Y Yasumoto K et al Comparison of myocardial injury and inflammation after pulmonary vein isolation for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation between radiofrequency catheter ablation and cryoballoon ablation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. (2020) 31(6):1315–22. 10.1111/jce.14475

47.

Wu Q Liu H Liao J Zhao N Tse G Han B et al Colchicine prevents atrial fibrillation promotion by inhibiting IL-1β-induced IL-6 release and atrial fibrosis in the rat sterile pericarditis model. Biomed Pharmacother Biomedecine Pharmacother. (2020) 129:110384. 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110384

48.

Zhang H Lai Y Zhou H Zou L Xu Y Yin Y . Prednisone ameliorates atrial inflammation and fibrosis in atrial tachypacing dogs. Int Heart J. (2022) 63(2):347–55. 10.1536/ihj.21-249

49.

Binder MS Timmerman C Marof B Wu Y Bankole A Heletz I . The cardiovascular effects of interleukin-6 inhibition in patients with severe coronavirus-19 infection. J Int Med Res. (2025) 53(4):3000605251324590. 10.1177/03000605251324590

Summary

Keywords

atrial fibrillation, left atrial diameter, NHANES, system inflammation response index, systemic inflammation markers

Citation

Wang D, Zhou G, Liu J, Xiu Y, Li H and Li B (2026) Association and impact of inflammatory markers and cardiac structure on atrial fibrillation risk: a study integrating NHANES with real-world data. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 12:1724217. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1724217

Received

17 October 2025

Revised

22 December 2025

Accepted

24 December 2025

Published

13 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Nicola Pierucci, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy

Reviewed by

Raimondo Pittorru, University of Padua, Italy

Tommaso Recchioni, Umberto 1 Hospital, Italy

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Wang, Zhou, Liu, Xiu, Li and Li.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Bo Li libosubmit@163.com Haiying Li 2627328593@qq.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.