Abstract

Background:

The monocyte-to-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio (MHR) has emerged as a novel biomarker for cardiovascular outcomes. However, its role in atrial fibrillation (AF) remains unclear. This meta-analysis aimed to evaluate the diagnostic efficacy of MHR in predicting AF risk.

Methods:

We systematically searched PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science up to March 20, 2025. The primary outcome was to assess the diagnostic accuracy of MHR for predicting AF using summary receiver operating characteristic (SROC) curve analysis. The secondary outcome was to explore the relationship between MHR and AF risk. Pooled odds ratio (OR), sensitivity, specificity, and area under the curve (AUC) were calculated.

Results:

A total of 13 studies comprising 5,499 participants were included. Elevated MHR was independently associated with an increased AF risk (OR = 1.21; 95% CI, 1.11–1.31; P < 0.001). The pooled sensitivity and specificity were 0.85 (95% CI, 0.71–0.93) and 0.68 (95% CI, 0.60–0.75), yielding an area under the SROC curve of 0.80 (95% CI, 0.76–0.83). Subgroup analyses revealed significant diagnostic performance variations by AF phenotype: MHR had the highest sensitivity (0.91; 95% CI 0.74–1.00) and AUC (0.94; 95% CI 0.91–0.96) in non-procedural AF, followed by post-ablation recurrence (sensitivity = 0.86, AUC = 0.83) and new-onset AF (sensitivity = 0.80, AUC = 0.83). Large-sample studies (>600) showed lower sensitivity (0.71 vs. 0.90) but higher specificity (0.78 vs. 0.60) than small-sample studies (≤600). No significant publication bias was detected (p = 0.45).

Conclusions:

MHR demonstrates moderate diagnostic accuracy for AF risk prediction and is better suited as a screening or complementary biomarker than a standalone diagnostic tool. Its diagnostic performance varies significantly by AF phenotype and clinical context. Given the limited number of studies, significant heterogeneity, and unstandardized MHR cut-offs, large-scale prospective studies with standardized protocols are warranted to validate these findings and facilitate targeted clinical application.

Systematic Review Registration:

https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/, identifier CRD420251030225.

1 Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF), characterized by rapid and irregular activation of the atrium, is one of the most common clinical arrhythmias, and its incidence is increasing, partly due to the global ageing population (1). The diagnosis of AF primarily relies on electrocardiograms (ECGs). The foundation of AF management includes heart rate control, anticoagulation, and rhythm control for patients whose symptoms are significantly affected by the condition. Despite advances in diagnosis and treatment, the incidence of AF remains high. By 2050, the number of patients affected by AF is projected to increase 2.5-fold, with more than half aged 80 or older (2). In the US, 6–12 million people will suffer from AF by 2050, while in Europe, 17.9 million will be affected by 2060 (3). AF not only leads to impaired cardiac function and increases the risk of heart failure, stroke, and mortality, but it also significantly affects patients' quality of life, thereby placing a substantial burden on healthcare systems and the economy (4). Early identification of high-risk populations for AF and timely implementation of interventions are essential to reduce its incidence and associated complications and to uncover potential therapeutic targets. Therefore, the discovery of effective biomarkers that can predict AF is of great importance.

The pathophysiological mechanisms underlying AF are intricate and multifactorial, involving inflammation, oxidative stress, apoptosis, fibrosis, and genetic factors. These processes contribute to structural and electrophysiological alterations during atrial remodeling (5, 6). Inflammation plays a crucial role in forming the atrial substrate, facilitating both structural and electrical remodeling by releasing pro-inflammatory cytokines and other inflammatory molecules, thereby heightening susceptibility to AF (7). Furthermore, inflammation disrupts calcium homeostasis and impairs connexin function, which are linked to AF triggers and heterogeneous atrial conduction (8). Oxidative stress results from an imbalance between reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and the body's antioxidant defenses. This condition fosters a pro-inflammatory state, leading to tissue damage, cardiac remodeling, and AF progression (9). Consequently, numerous studies have explored the relationship between inflammatory biomarkers and AF. A variety of inflammatory biomarkers, such as high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), interleukin-2 (IL-2), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), have been associated with both the risk and progression of AF (10, 11).

The monocyte-to-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio (MHR) is a novel biomarker reflecting inflammation, oxidative stress, and metabolic syndrome. First proposed by Kanbay et al. in 2014, MHR has been found to be associated with adverse cardiovascular events in patients with chronic kidney disease (12). Since then, MHR has been extensively studied, particularly in the context of risk stratification and prognosis for cardiovascular diseases (13). Monocytes originate from hematopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow and are a major component of the human immune system. Activated monocytes can stimulate the production of inflammatory cytokines and pro-oxidants, thereby contributing to endothelial injury and atherosclerosis formation (14, 15). High-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) promotes reverse cholesterol transport, enabling the removal of excess cholesterol from peripheral tissues to the liver. HDL-C exhibits anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antithrombotic, and anti-atherosclerotic properties, all of which positively influence cardiovascular outcomes (16). Elevated MHR levels indicate greater systemic inflammation and immune activation. Combining monocyte and HDL-C parameters may provide more valuable information about inflammation and oxidative stress status than either parameter alone. Moreover, MHR stands out as a highly accessible biomarker in clinical settings due to its affordability and widespread availability. Interestingly, recent studies have highlighted the predictive role of MHR in AF development. However, there is no consensus on the capacity of MHR for AF prediction. We therefore conducted this systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate whether MHR could serve as a predictive biomarker for AF and to inform clinical management.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Data source and protocol registration

The present systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 recommendations (17) and registered in PROSPERO (CRD420251030225). A literature search was performed across three databases (PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science) to identify relevant studies up to March 20, 2025. The search strategy was as follows: (“monocyte to HDL-cholesterol ratio” OR “monocyte/HDL-cholesterol ratio” OR “monocyte to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio” OR “monocyte/high-density lipoprotein ratio” OR “monocyte/HDL ratio” OR “monocyte to HDL ratio” OR “MHR”) AND (“atrial fibrillation” OR “AF”). The included studies had no language or geographic restrictions. Additionally, we reviewed the reference lists of relevant original studies and major review articles to identify further relevant studies.

2.2 Study inclusion and exclusion criteria

Articles were included in this meta-analysis if they met the following criteria: (1) study type including randomized controlled trials, prospective or retrospective cohort studies, case-control studies, or cross-sectional studies; (2) reported the hazard ratio (HR) or odds ratio (OR) with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the association between MHR and the risk of AF; (3) evaluated the diagnostic performance of MHR in AF; (4) provided available data to directly or indirectly calculate true positive (TP), false positive (FP), false negative (FN), and true negative (TN) values to construct the 2 × 2 table; (5) had a clearly established diagnosis of AF in accordance with current guideline definitions. Exclusion criteria were established as follows: (1) letters, editorials, conference presentations, studies without a control group, case reports, and non-human studies; (2) studies with inaccessible full text or missing data; (3) duplicate or overlapping publication; (4) studies with a high risk of bias or controversial design.

2.3 Data extraction and quality assessment

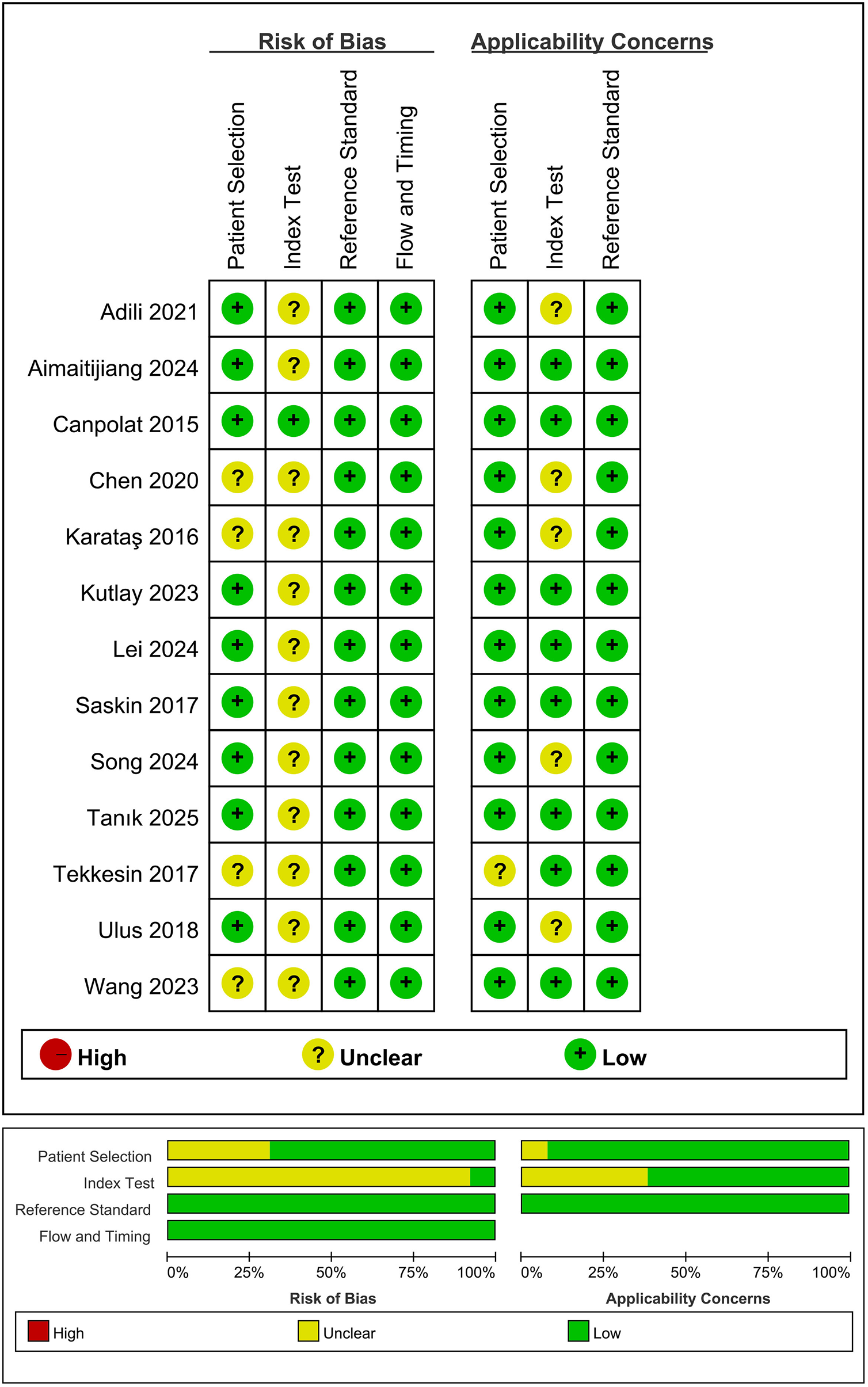

Two authors independently extracted the following data: name of the first author, year of publication, country, study design, sample sizes, age, gender, study periods year, MHR cut-off values, sensitivity, specificity, rates of postoperative AF, and follow-up period. Monocyte counts were standardized to cells/µL. For studies reporting HDL-C in mmol/L, we converted it to mg/dL using the conversion factor: 1 mmol/L = 38.67 mg/dL. The methodological quality of each included study was independently evaluated by two authors using the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies-2 (QUADAS-2) tool (18). The QUADAS-2 tool assesses four main domains: patient selection, index test, reference standard, and flow and timing. The risk of bias in each domain was assessed and categorized as high, low, or unclear. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion or consultation with a third reviewer. The quality assessment was conducted using Review Manager (Version 5.4). The green portion indicates compliance with the standard requirements, the red portion signifies non-compliance, and the yellow portion represents uncertainty.

2.4 Primary and secondary outcome

The primary outcome was to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of MHR for predicting AF using summary receiver operating characteristic (SROC) curve analysis. The secondary outcome was to assess the pooled odds ratio (OR) for the association between MHR and AF risk.

2.5 Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using STATA, version 14.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX) and R software (version 4.5.0). Both Cochrane's Q test and the I2 statistic were used to assess heterogeneity across studies. A P-value < 0.10 or I2 > 50% indicated statistically significant heterogeneity. We chose the random-effects model to synthesize results when heterogeneity was significant; otherwise, the fixed-effects model was applied. When heterogeneity was present, meta-regression and subgroup analysis were used to explore its sources. Meta-Disc 1.4 software was used to assess threshold effects using the Spearman correlation coefficient between the logarithm of sensitivity and 1-specificity. When the P-value was < 0.05, the threshold effect was considered significant. Overall diagnostic accuracy was evaluated by plotting the summary receiver operating characteristic (SROC) curve. The area under the curve (AUC) was calculated as a measure of diagnostic performance. An AUC > 0.7 was considered a significant predictor of risk (19). When there was no evidence of a threshold effect, the bivariate random-effects model was applied to estimate pooled sensitivity, specificity, positive likelihood ratio (+LR), negative likelihood ratio (−LR), diagnostic score, and diagnostic odds ratio (DOR). Publication bias was assessed using the Deeks' funnel plot asymmetry test. In all analyses, a P value of 0.05 was employed to assess statistical significance.

3 Results

3.1 Search results and studies characteristics

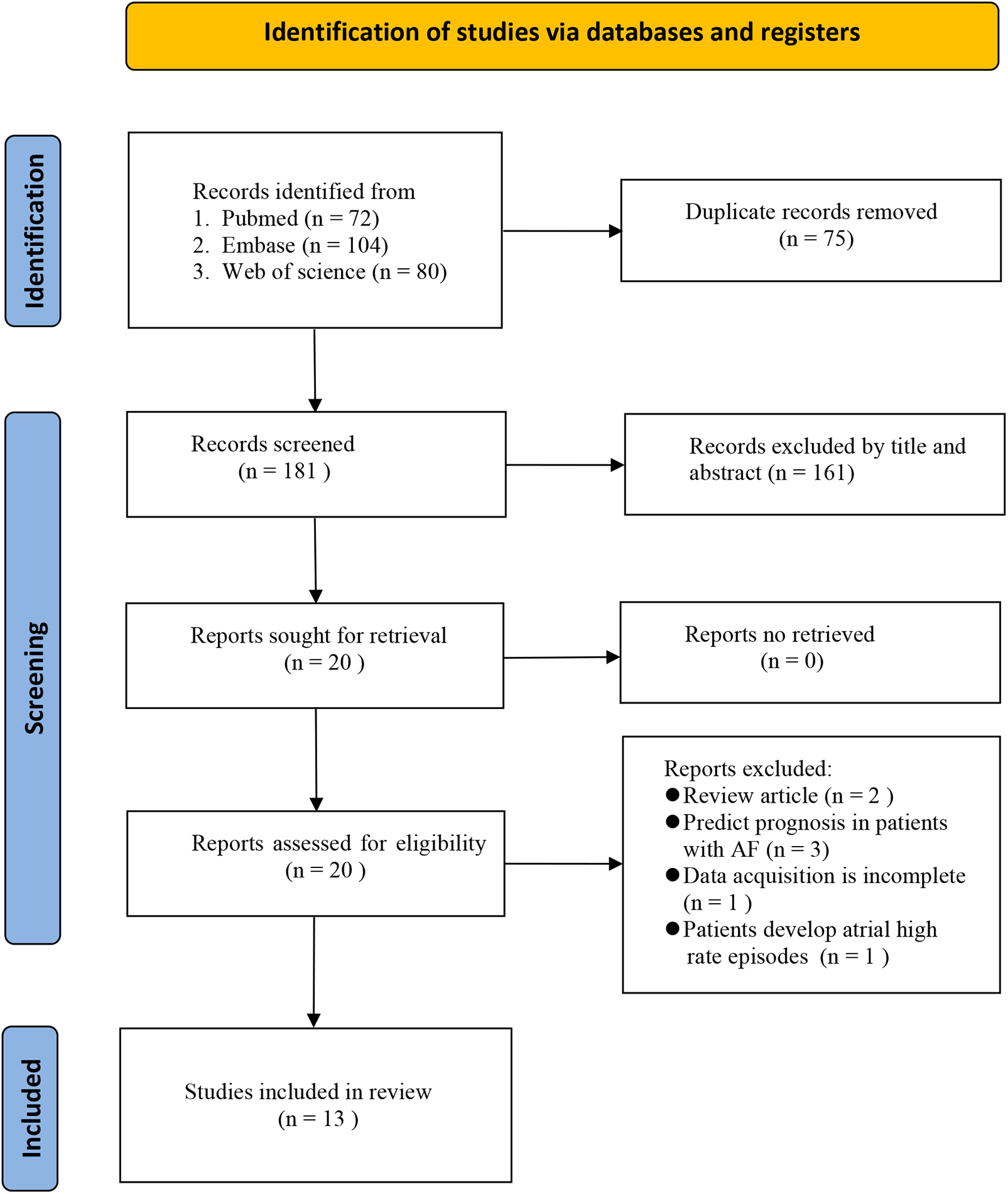

The literature screening flow diagram is shown in Figure 1. A total of 256 studies were retrieved from the three databases using the search strategy. We identified 75 duplicates and excluded them. The remaining 181 studies were screened by title and abstract to identify relevant studies. After excluding 161 studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria, 20 were eligible for comprehensive full-text review. Seven articles were excluded after full-text review for the following reasons: review articles (n = 2), prognostic prediction in patients with AF (n = 3), incomplete data acquisition (n = 1), and patients developing atrial high-rate episodes (n = 1). Finally, thirteen eligible studies involving 5,499 participants were included and analyzed (20–32).

Figure 1

Flow diagram of study selection.

The main characteristics and findings of the included studies are presented in Table 1. Sample sizes ranged from 131 to 817, and mean patient age ranged from 53.5 to 74.4 years; the overall proportion of males was high. Follow-up periods ranged from 3 to 25.1 months. Among the included studies, one study was prospective (20), and the remaining twelve were retrospective (21–32). Seven studies were conducted in Turkey (20–24, 28, 32), and six in China (25–27, 29–31). Five studies investigated the relationship between MHR and new-onset AF after coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) (21–24, 32). Six studies reported an association between MHR and AF recurrence after radiofrequency maze procedure and catheter ablation (20, 25, 26, 29–31). According to the QUADAS-2 results (Figure 2), all 13 included studies were of high quality. The index test was identified as the primary source of high risk, as the diagnostic cut-off values were based on predefined thresholds. In contrast, the other domains of the studies showed a lower risk of bias.

Table 1

| Author/year | Country | Study design | Study periods year | Study population | Patients (n) | Male (%) | Mean age years | Follow-up (month) | Rates of postoperative AF | Cut-off | Sensitivity | Specificity | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canpolat 2015 | Turkey | Prospective | 2010–2013 | Patients with AF after cryoballoon ablation | 402 | 227 (56.5%) | 53.5 ± 10.9 | 20.6 ± 6 | 23.6% | 11.48 | 85% | 74% | 0.85 |

| Karataş 2016 | Turkey | Retrospective | 2009–2013 | Patients with STEMI after PCI | 621 | 464 (74.7%) | 57 ± 11.9 | 22 | 64.4% | 25.81 | 75% | 80% | 0.84 |

| Saskin 2017 | Turkey | Retrospective | 2010–2014 | After CABG | 662 | 541 (81.7%) | 60.9 ± 6.9 | NA | 23.1% | 18.50 | 86.9% | 72.5% | 0.84 |

| Tekkesin 2017 | Turkey | Retrospective | 2015 | After CABG | 311 | 205 (65.9%) | 60.1 ± 8.7 | NA | 22.8% | 8.55 | NA | NA | 0.84 |

| Ulus 2018 | Turkey | Retrospective | 2016–2017 | Patients with ACS after PCI | 308 | 202 (65.6%) | 74.4 ± 6.5 | NA | 17.5% | 15.87 | 75.9% | 65.0% | 0.75 |

| Chen 2020 | China | Retrospective | 2015–2018 | Patients with AF after RFCA | 125 | 69 (55.2%) | 61.2 ± 9.3 | 25.1 ± 12.0 | 37.6% | NA | NA | NA | 0.71 |

| Adili 2021 | China | Retrospective | 2018–2019 | Patients with AF after RF maze procedure | 131 | 54 (41.2%) | 60 (54–67) | 3 | 53.4% | 8.53 | 89% | 54% | 0.77 |

| Wang 2023 | China | Retrospective | 2019–2022 | AF patients and controls | 817 | 504 (61.7%) | 61.9 ± 9.8 | NA | NA | 16.94 | 42.7% | 85.2% | 0.60 |

| Kutlay 2023 | Turkey | Retrospective | 2019–2021 | AF patients and controls | 241 | 115 (47.7%) | 65.7 ± 9.9 | NA | NA | 15.00 | 100% | 56% | 0.80 |

| Song 2024 | China | Retrospective | 2019–2021 | Patients with AF after catheter ablation | 438 | 268 (61.2%) | 62 (54–66) | NA | 26.3% | NA | NA | NA | 0.64 |

| Aimaitijiang 2024 | China | Retrospective | 2015–2018 | Patients with AF after cryoablation | 570 | 100 (17.5%) | 66 ± 9.3 | 24 | 19.8% | 7.50 | 76% | 44% | 0.60 |

| Lei 2024 | China | Retrospective | 2020–2022 | Patients with AF after RFCA | 210 | 141 (67.1%) | 54.4 ± 8.7 | 12 | 37.1% | 8.68 | 93.59% | 65.91% | 0.83 |

| Tanık 2025 | Turkey | Retrospective | 2017–2018 | Patients with STEMI after PCI | 663 | 572 (86.3%) | 55.8 ± 12.9 | NA | 5.1% | 26.54 | 70.59% | 72.45% | 0.77 |

Basic characteristics of studies included into the meta-analysis.

AF, atrial fibrillation; STEMI, ST segment elevation myocardial infarction; ACS, acute coronary syndrome; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; RF, radiofrequency; RFCA, radiofrequency catheter ablation.

Figure 2

Quality assessment of included studies based on QUADAS-2 tool criteria.

3.2 Meta-analysis

3.2.1 The relationship between MHR and AF risk

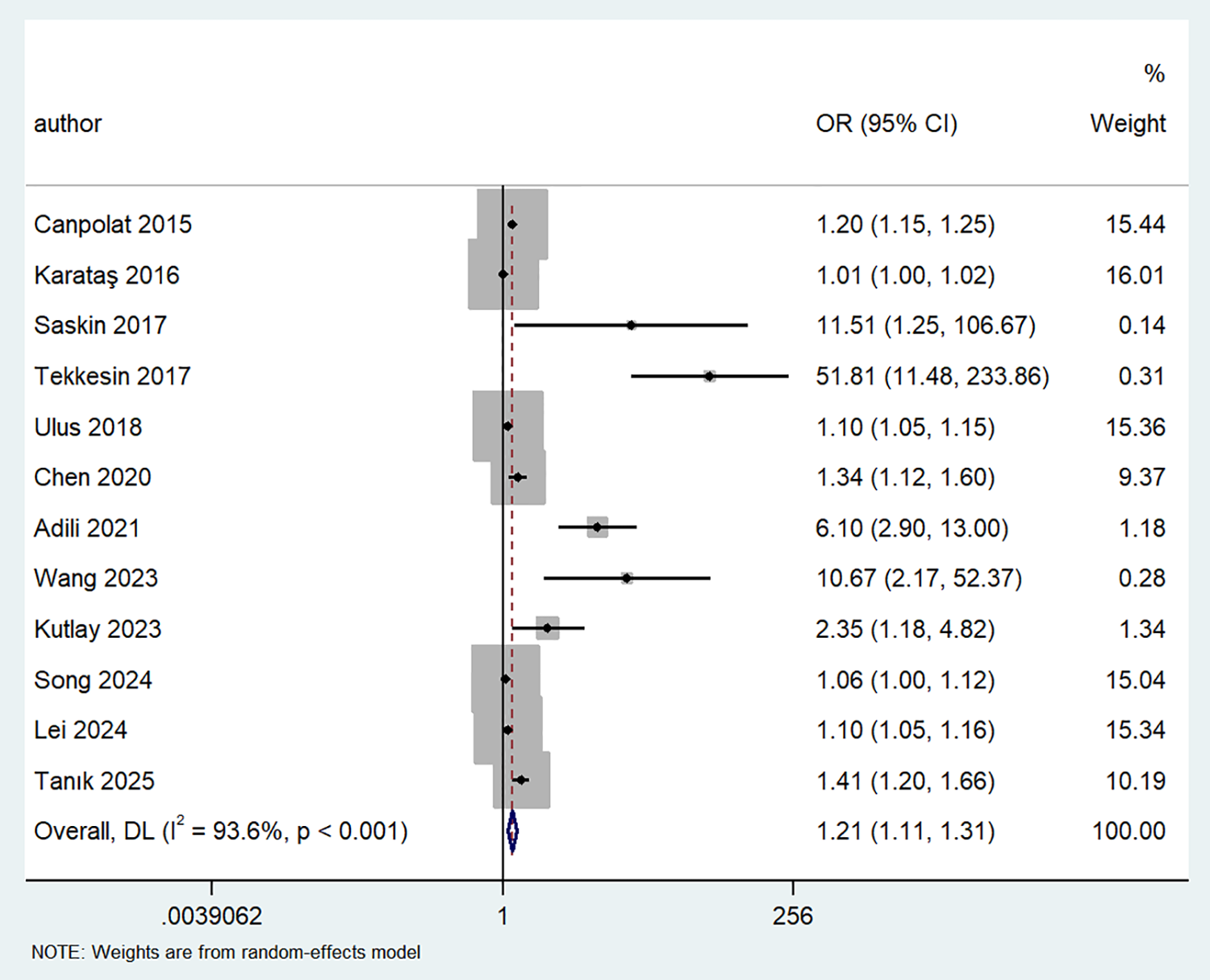

Twelve studies examined the association between MHR and AF risk, using a random-effects model (I2 = 93.6%, P < 0.001) to pool the effect size. The results showed a significant correlation between MHR and AF risk (OR = 1.21, 95% CI: 1.11–1.31, P < 0.001), indicating that MHR was an independent predictor of AF (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Forest plot showing the odds ratio for AF in patients with high vs. low MHR levels.

3.2.2 Analysis of the threshold effect

In diagnostic meta-analyses, sources of heterogeneity include threshold and non-threshold effects. The SROC curve did not exhibit the typical “shoulder-arm” shape, and Spearman's correlation coefficient between sensitivity and log(1−specificity) was 0.6 (P = 0.067, P > 0.05), indicating no significant heterogeneity attributable to the threshold effect and supporting pooling of the data.

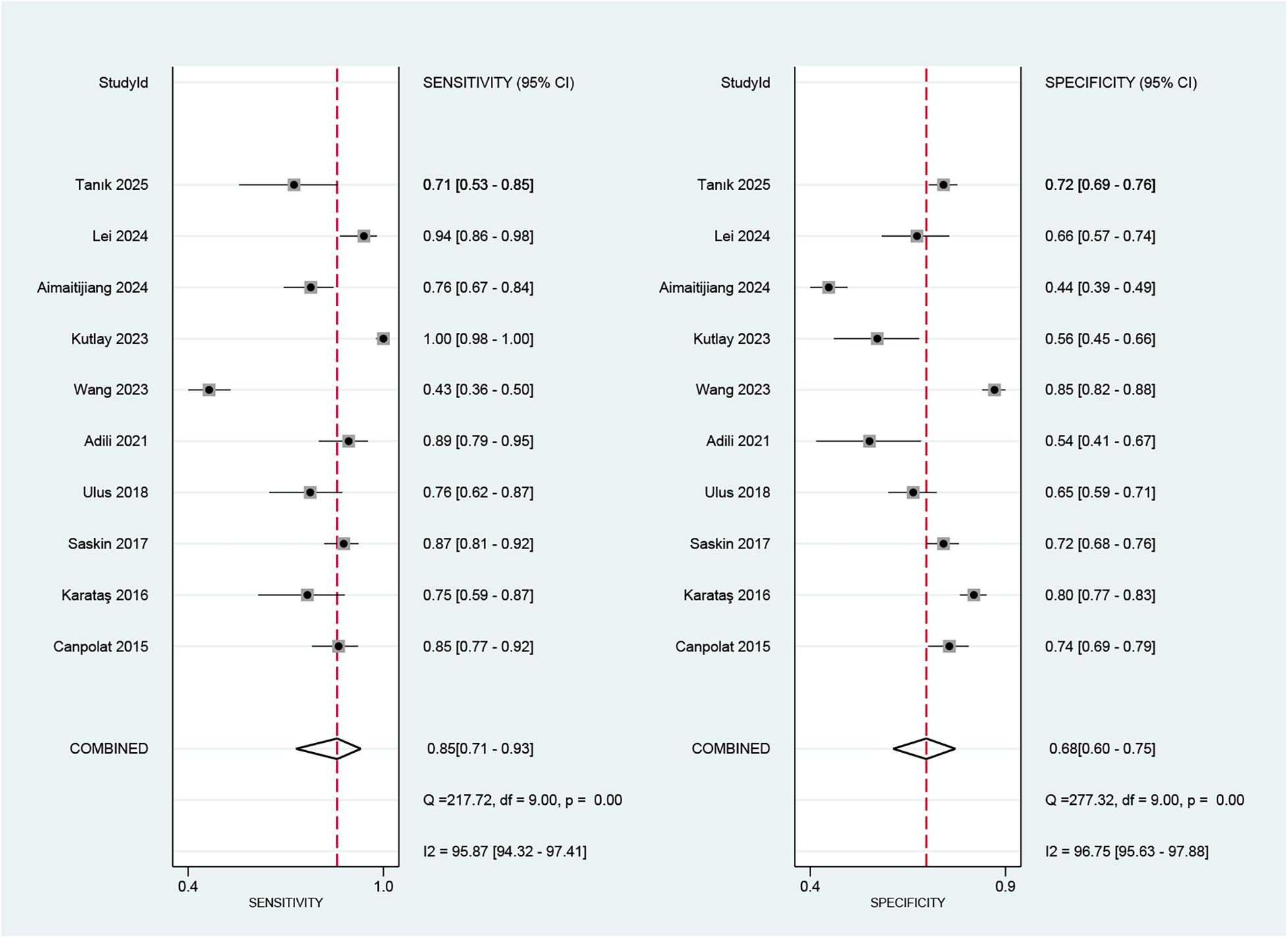

3.2.3 Diagnostic efficacy of MHR in predicting AF

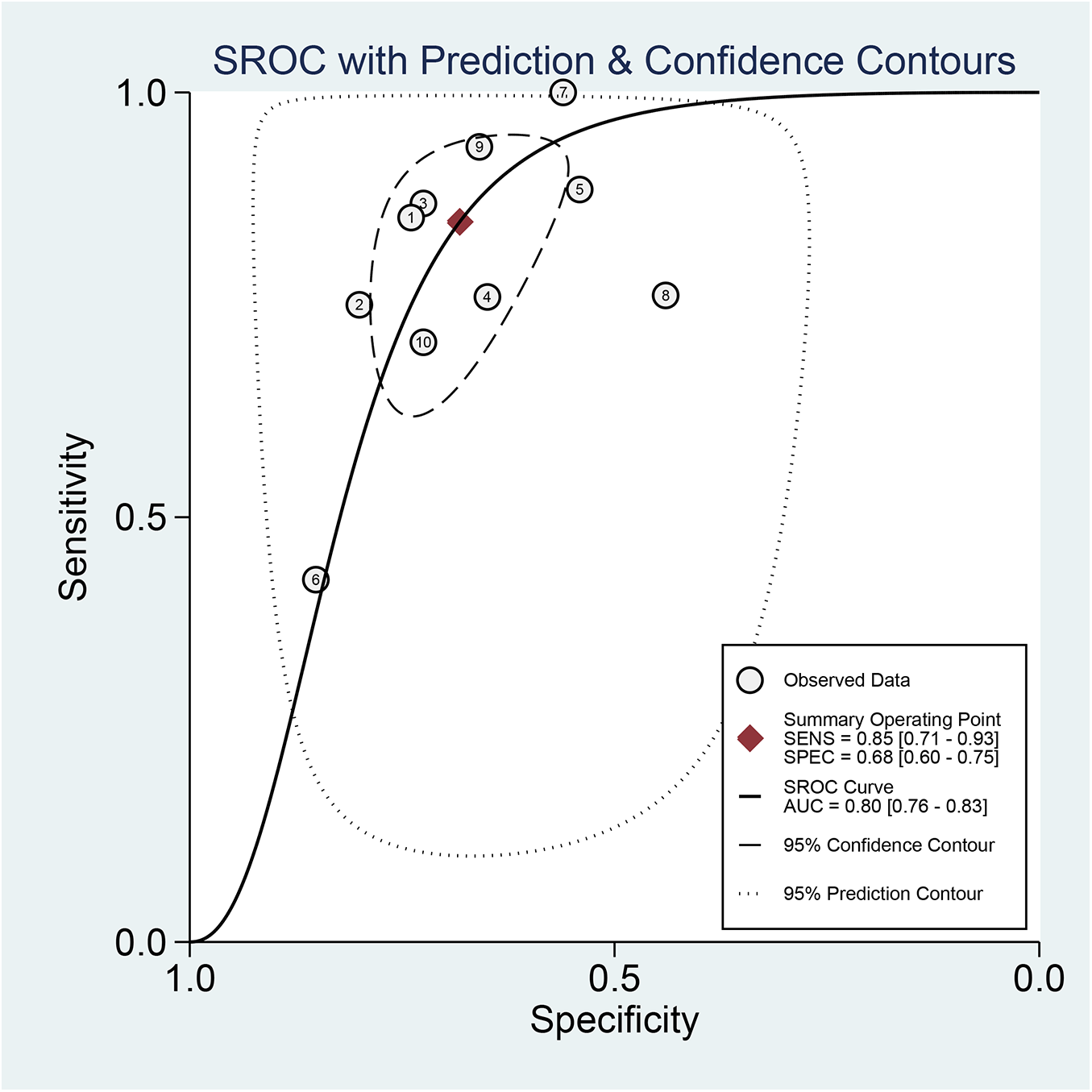

Regarding the diagnostic accuracy of MHR, the pooled sensitivity was 0.85 (95% CI: 0.71–0.93), and the specificity was 0.68 (95% CI: 0.60–0.75). Significant heterogeneity was observed across studies. The I2values were 95.87% (95% CI: 94.32–97.41) for sensitivity and 96.75% (95% CI: 95.63–97.88) for specificity (Figure 4). As shown in Supplementary Figure S1, the +LR and −LR were reported as 2.67 (95% CI: 2.16–3.30) and 0.22 (95% CI: 0.12–0.42), respectively. The diagnostic score and DOR presented in (Supplementary Figure S2) were 2.48 (95% CI: 1.78–3.18) and 11.94 (95% CI: 5.90–24.17), respectively. The SROC curve in Figure 5 showed an AUC of 0.80 (95% CI: 0.76–0.83), suggesting moderate diagnostic accuracy.

Figure 4

Forest plot depicting the combined sensitivity and specificity of the MHR in predicting AF.

Figure 5

Analysis of SROC curve showing the predictive effectiveness of MHR concerning AF.

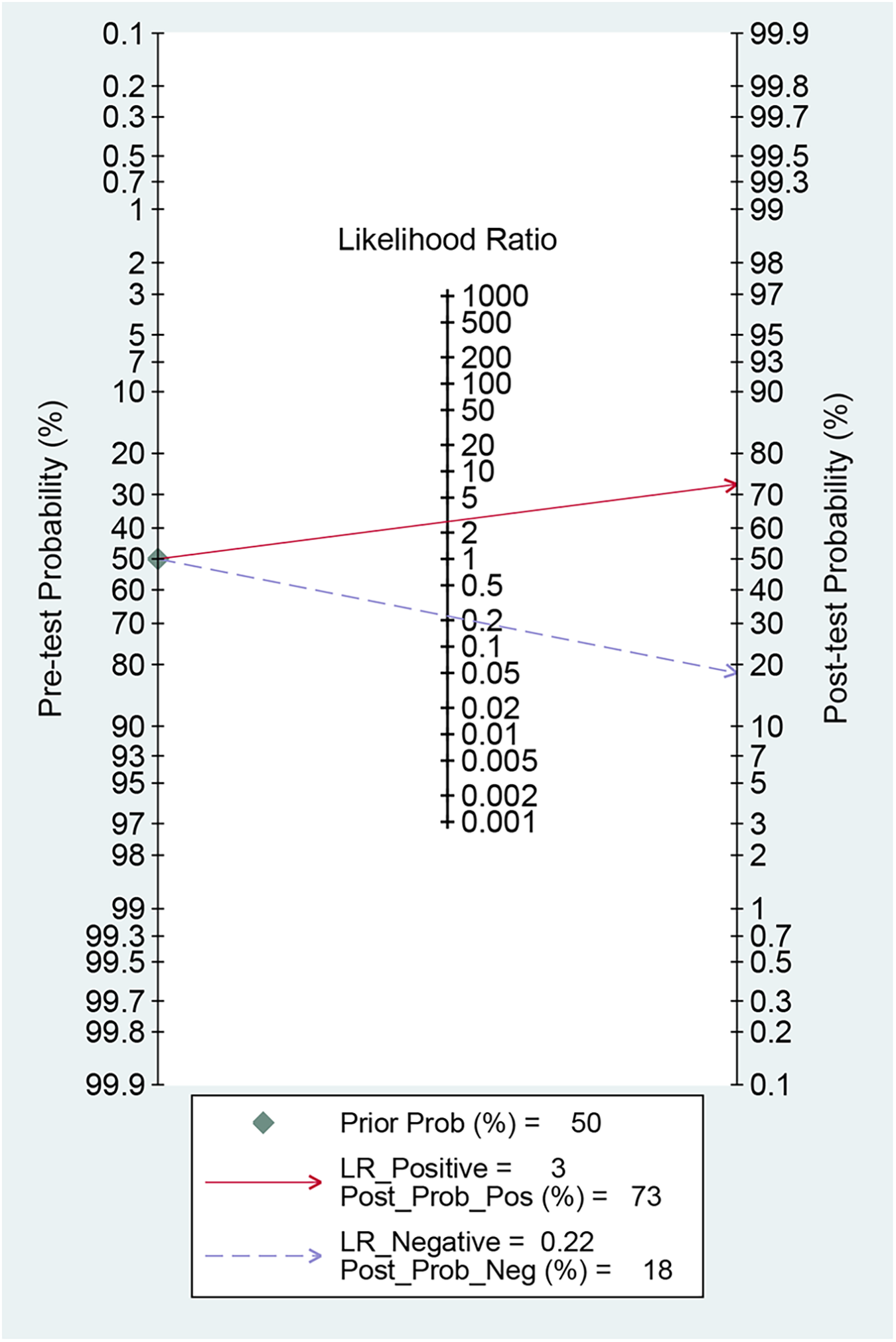

3.2.4 Fagan nomogram for post-test probabilities

Fagan's nomogram is a graphical tool used to evaluate the clinical utility of diagnostic tests by quantifying post-test probabilities. The current analysis yielded a +LR of 3.00 and a −LR of 0.22. Consequently, with a pre-test probability set at 50%, the post-test probability of AF increased to 73% for a positive MHR test; conversely, it decreased to 18% for a negative test. These results indicate that a positive MHR test significantly elevates the likelihood of AF to 73%, while a negative test reduces this probability to 18% relative to the pre-test probability (Figure 6).

Figure 6

Fagan nomogram for assessing the clinical utility of MHR for predicting AF.

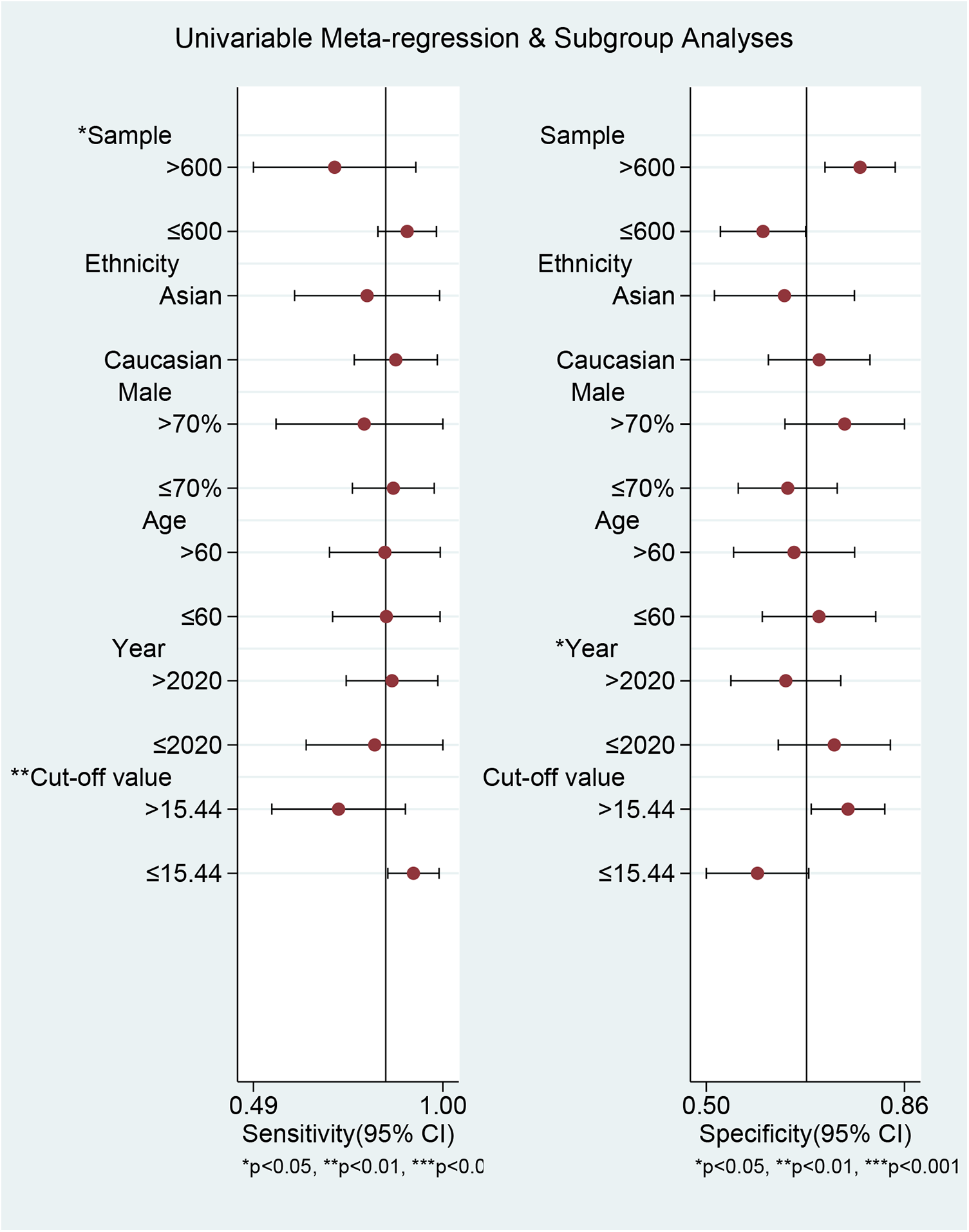

3.2.5 Meta-regression and subgroup analysis

We conducted meta-regression and subgroup analyses to explore sources of heterogeneity in sensitivity and specificity across the included studies. The variables included were sample size, ethnicity, mean age, proportion of males, article publication year, cut-off value, and study population (Figure 7; Table 2). We found that sample size and cut-off value significantly contributed to heterogeneity in sensitivity but not in specificity. In contrast, publication year significantly affected heterogeneity in specificity but not in sensitivity. The joint model results indicated that sample size and cut-off value subgroups significantly affected heterogeneity in both sensitivity and specificity. When stratified by sample size, pooled sensitivity was higher in small-sample studies (≤600) at 0.90 (95% CI: 0.83–0.98) than in large-sample studies (>600) at 0.71 (95% CI: 0.49–0.93), whereas specificity (0.60 vs. 0.78) and AUC (0.74 vs. 0.82) showed the opposite trend. Ethnicity stratification revealed that studies involving Caucasian populations had higher sensitivity [0.87 (95% CI: 0.76–0.99)], specificity [0.71 (95% CI: 0.61–0.80)], and AUC [0.79 (95% CI: 0.75–0.82)] than those involving Asian populations [sensitivity: 0.80 (95% CI: 0.60–0.99), specificity: 0.64 (95% CI: 0.51–0.77), AUC: 0.77 (95% CI: 0.73–0.80)]. Stratification by male proportion showed higher sensitivity in the lower proportion group (≤70%: 0.87 vs. >70%: 0.79), albeit with lower specificity (0.65 vs. 0.75) and AUC (0.78 vs. 0.83). Stratification by age showed identical sensitivity [0.85 (95% CI: 0.70–0.99)] in older and younger patients, but superior specificity (>60 years: 0.71 vs. ≤60 years: 0.66) and AUC (>60 years: 0.84 vs. ≤60 years: 0.77) in older patients. Studies published after 2020 had slightly higher sensitivity [0.86 (95% CI: 0.74–0.99)] than those published in or before 2020 [0.82 (95% CI: 0.64–1.00)], while specificity (0.64 vs. 0.73) and AUC (0.77 vs. 0.86) showed the inverse pattern. Studies employing a diagnostic cut-off value >15.44 reported lower sensitivity (0.72 vs. 0.92) but higher specificity (0.76 vs. 0.59) and AUC (0.80 vs. 0.75) than those using lower thresholds. Study population stratification revealed that studies focusing on non-procedural AF phenotypes had the highest sensitivity [0.91 (95% CI: 0.74–1.00)] and AUC [0.94 (95% CI: 0.91–0.96)], followed by those conducted in AF recurrence (sensitivity: 0.86; specificity: 0.60; AUC: 0.83) and new-onset AF (sensitivity: 0.80; specificity: 0.73; AUC: 0.83).

Figure 7

The results of meta-regression and subgroup analyses.

Table 2

| Parameter | Category | Number of studies | Sensitivity | Pb | Specificity | Pb | Joint model analysis | AUC | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pooled sensitivity (95% CI) | I2% | Pa | Pooled specificity (95% CI) | I2% | Pa | LRTchi2 | Pc | I2 (%) (95% CI) | ||||||

| Sample size | >600 | 4 | 0.71 (0.49–0.93) | 92.77 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.78 (0.72–0.84) | 92.66 | 0.00 | 0.72 | 8.31 | 0.02 | 76 (47–100) | 0.82 (0.78–0.85) |

| ≤600 | 6 | 0.90 (0.83–0.98) | 79.52 | 0.00 | 0.60 (0.52–0.68) | 89.96 | 0.00 | 0.74 (0.70–0.78) | ||||||

| Ethnicity | Asian | 4 | 0.80 (0.60–0.99) | 95.94 | 0.00 | 0.29 | 0.64 (0.51–0.77) | 97.37 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 2.43 | 0.30 | 18 (0–100) | 0.77 (0.73–0.80) |

| Caucasian | 6 | 0.87 (0.76–0.99) | 60.58 | 0.00 | 0.71 (0.61–0.80) | 89.67 | 0.00 | 0.79 (0.75–0.82) | ||||||

| Male proportion | >70% | 3 | 0.79 (0.55–1.00) | 69.34 | 0.03 | 0.41 | 0.75 (0.64–0.86) | 83.44 | 0.00 | 0.57 | 1.77 | 0.41 | 0 (0–100) | 0.83 (0.77–0.89) |

| ≤70% | 7 | 0.87 (0.76–0.98) | 95.23 | 0.00 | 0.65 (0.56–0.74) | 95.45 | 0.00 | 0.78 (0.74–0.81) | ||||||

| Age | >60 | 5 | 0.85 (0.70–0.99) | 97.73 | 0.00 | 0.67 | 0.66 (0.55–0.77) | 97.53 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.48 | 0.79 | 0 (0–100) | 0.77 (0.73–0.81) |

| ≤60 | 5 | 0.85 (0.70–0.99) | 71.06 | 0.01 | 0.71 (0.60–0.81) | 90.22 | 0.00 | 0.84 (0.80–0.87) | ||||||

| Publication year | >2020 | 6 | 0.86 (0.74–0.99) | 96.39 | 0.00 | 0.98 | 0.64 (0.54–0.74) | 96.60 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 1.37 | 0.50 | 0 (0–100) | 0.77 (0.73–0.80) |

| ≤2020 | 4 | 0.82 (0.64–1.00) | 49.67 | 0.12 | 0.73 (0.63–0.84) | 86.75 | 0.00 | 0.86 (0.83–0.89) | ||||||

| Cut off | >15.44 | 5 | 0.72 (0.54–0.90) | 90.44 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.76 (0.69–0.83) | 93.98 | 0.00 | 0.83 | 7.65 | 0.02 | 74 (42–100) | 0.80 (0.77–0.84) |

| ≤15.44 | 5 | 0.92 (0.85–0.99) | 82.90 | 0.00 | 0.59 (0.50–0.69) | 90.80 | 0.00 | 0.75 (0.71–0.79) | ||||||

| Study population | New-onset AF | 4 | 0.80 (0.72–0.87) | 61.58 | 0.05 | / | 0.73 (0.65–0.81) | 86.96 | 0.00 | / | / | / | / | 0.83 (0.79–0.86) |

| AF recurrence | 4 | 0.86 (0.81–0.92) | 78.43 | 0.00 | / | 0.60 (0.51–0.70) | 96.24 | 0.00 | / | / | / | / | 0.83 (0.80–0.86) | |

| Non-procedural AF | 2 | 0.91 (0.74–1.00) | 94.37 | 0.00 | / | 0.73 (0.58–0.89) | 97.46 | 0.00 | / | / | / | / | 0.94 (0.91–0.96) | |

Meta-regression analysis and subgroup analysis.

95% CI, 95% confidence interval; Pa, value for heterogeneity within each subgroup; Pb, value for heterogeneity between subgroups with meta-regression analysis; Pc, value for joint model estimates; AUC, area under the curve.

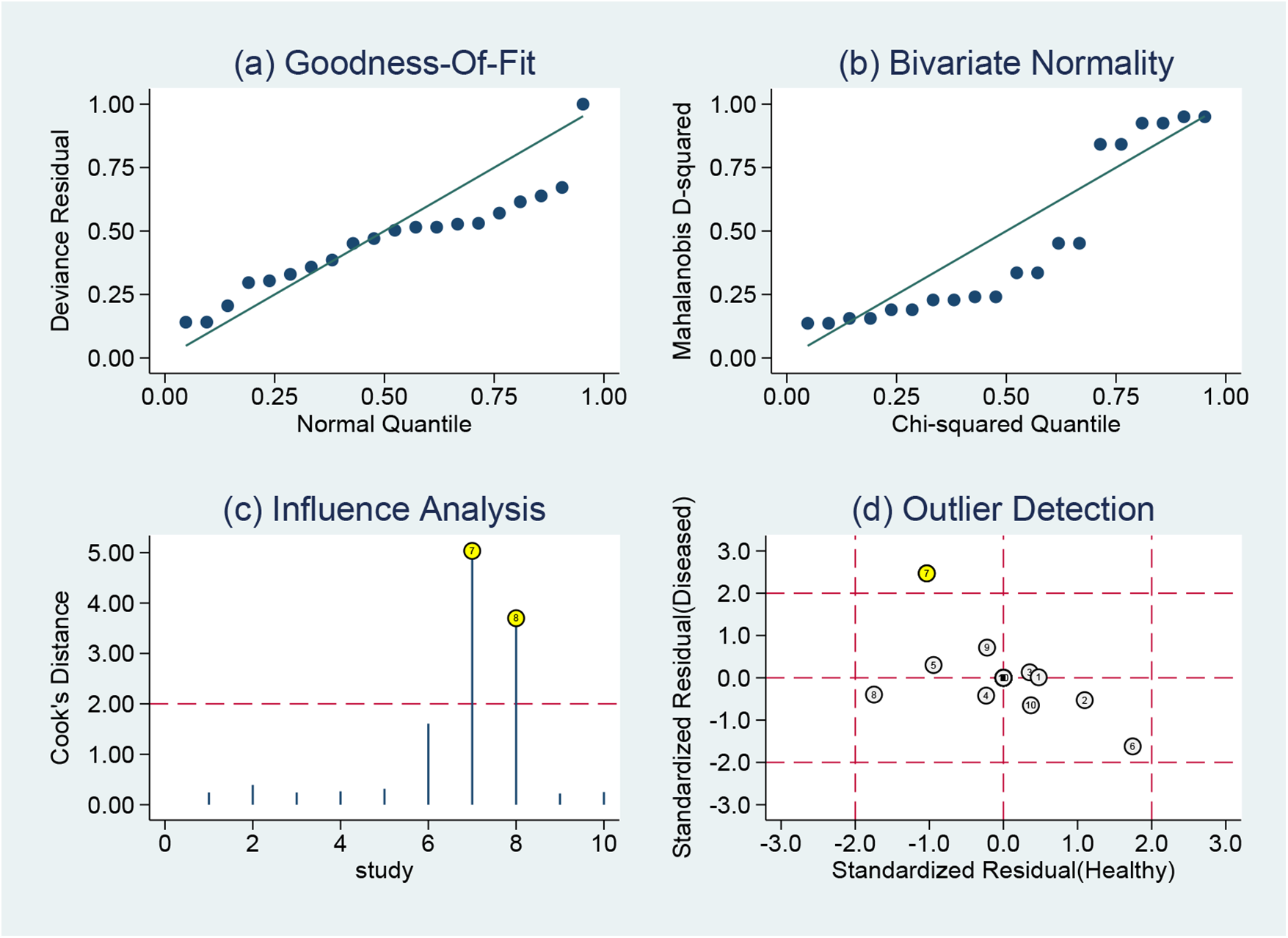

3.2.6 Sensitivity analysis

Goodness-of-fit and bivariate normality tests confirmed the suitability and reliability of using a bivariate mixed-effects model for meta-analysis (Figures 8a,b). Sensitivity analysis identified two studies (28, 30) that strongly influenced study weights (Figure 8c), while outlier detection revealed one aberrant study (28) (Figure 8d). Subsequent reanalysis was performed after excluding these two studies (Supplementary Table S1). Results showed that pooled sensitivity decreased from 0.85 to 0.80, whereas pooled specificity increased from 0.68 to 0.73. Additionally, pooled +LR rose from 2.67 to 2.94, and the pooled −LR increased from 0.22 to 0.27. The pooled DOR declined from 11.94 to 10.91. Finally, the AUC of the SROC curve improved from 0.80 to 0.81. The effect sizes from the reanalysis remained relatively robust relative to the pooled results before excluding the two studies, indicating that the findings of this study were stable.

Figure 8

Sensitivity analysis results of MHR in diagnosing AF: (a) goodness of fit, (b) bivariate normality, (c) influence analysis, and (d) outlier detection.

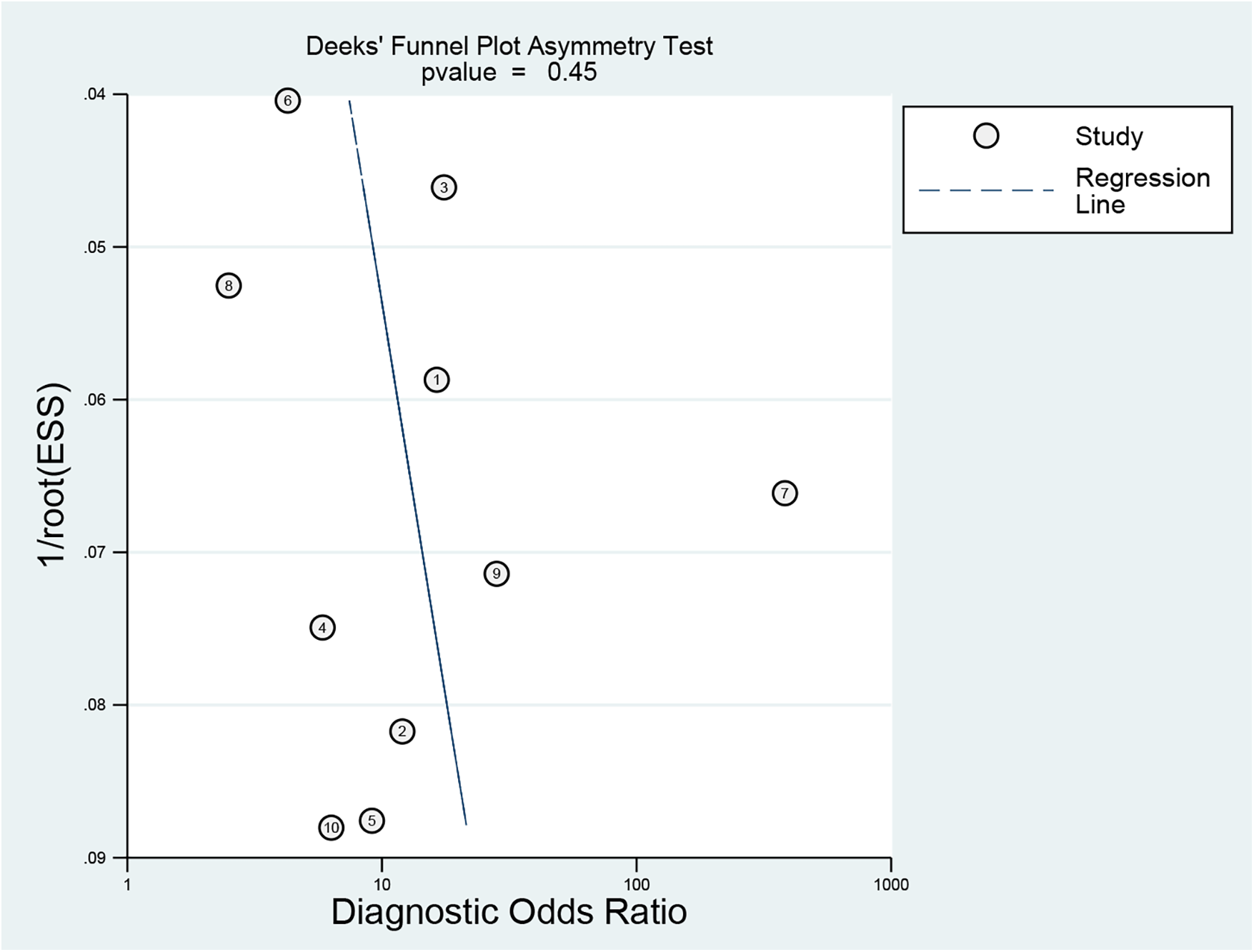

3.2.7 Publication bias

Linear regression analysis was used to assess funnel plot asymmetry. The Deeks' funnel plot was symmetrical, indicating no evidence of publication bias (P = 0.45) (Figure 9).

Figure 9

Funnel plot for publication bias assessment of included studies.

4 Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this meta-analysis is the first to evaluate the association between MHR and AF, incorporating data from 5,499 patients across thirteen studies. The findings indicate that elevated MHR is independently associated with a 21% increased risk (OR, 1.21; 95% CI: 1.11–1.31) of developing AF. Regarding diagnostic accuracy, the pooled sensitivity and specificity of the MHR for predicting AF were 0.85 and 0.68, respectively, with an area under the SROC curve of 0.80. According to this result, the MHR exhibits moderate diagnostic accuracy for AF risk prediction. However, given the significant heterogeneity across the different studies, caution is warranted in generalizing and interpreting these findings.

AF is one of the most prevalent arrhythmias and poses a significant challenge in daily clinical practice. Major adverse outcomes associated with AF include stroke, heart failure, sudden cardiac arrest, cognitive impairment, depression, and increased mortality. Although the precise pathogenesis of AF remains incompletely understood, current evidence indicates that inflammation and oxidative stress are central to its onset, persistence, and progression (4). Atrial tissue biopsies from AF patients show inflammatory infiltrates and oxidative damage, which are absent in non-AF control subjects (33). Moreover, AF can induce inflammation during atrial remodeling by recruiting inflammatory cells that release ROS, cytokines, and growth factors, resulting in increased extracellular matrix deposition and subsequent pathological atrial remodeling (34). The interaction between oxidative stress and inflammation further amplifies matrix remodeling and exacerbates atrial fibrosis (35). Activated inflammatory cells and mediators contribute to endothelial dysfunction and platelet activation, fostering a prothrombotic state and linking inflammation to thrombosis in AF (10). Previous studies have indicated that drugs with immunomodulatory properties, including glucocorticoids, HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins), and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, may be effective strategies for intervening in AF progression (36).

WBC count and its subtypes are established markers of inflammation. Monocytes, comprising approximately 2% to 8% of total WBCs, are essential components of the innate immune system. They play a critical role in the development and progression of cardiovascular diseases by contributing to atherosclerotic plaque formation and promoting plaque instability (15). As key effector cells in the inflammatory response, monocytes are pivotal mediators in AF. Although the precise mechanisms remain incompletely defined, several potential pathways have been identified. Monocytes activate the inflammatory cascade by adhering to injured vascular endothelial cells (37) and inducing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α, transforming growth factor-α, platelet-derived endothelial growth factor, macrophage colony-stimulating factor, and insulin-like growth factor. These cytokines intensify local and systemic inflammation, ultimately resulting in atrial tissue damage (20, 37–39). Monocytes also generate ROS and reactive nitrogen species (RNS), which exacerbate oxidative stress and induce injury and apoptosis in atrial myocytes (40). Additionally, they secrete factors including transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), promoting atrial fibroblast proliferation and collagen deposition, thereby initiating atrial structural remodeling (41). Furthermore, monocytes can alter ion channel expression and function, disrupting the electrophysiological stability of atrial myocytes (42). Fontes et al. demonstrated that patients who developed AF after cardiac surgery exhibited heightened leukocyte activation, with monocyte activation particularly pronounced (43).

Dyslipidemia is a recognized risk factor for both atherosclerotic vascular disease and AF. HDL-C is the only lipoprotein inversely correlated with atherosclerosis and is distinguished by its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties. HDL-C inhibits the expression of endothelial adhesion molecules, prevents monocyte infiltration into the arterial wall, reduces the release of inflammatory factors, and decreases oxidative stress (44). Conversely, low HDL-C levels are associated with increased inflammation. Statins and experimental agents can enhance HDL-C's anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting macrophage inflammatory activity (37). HDL-C also facilitates reverse cholesterol transport, which reduces lipid deposition in atrial tissue, suppresses fibrosis and extracellular matrix remodeling (45), promotes cellular cholesterol efflux, regulates vascular inflammation and vasomotor function, and reduces thrombus formation (46). Additionally, HDL modulates ion channel function and calcium homeostasis, thereby altering atrial electrophysiological properties and increasing susceptibility to AF (47). Reduced HDL-C levels compromise these protective effects, further contributing to AF development and progression (27). Epidemiological studies support the association between HDL-C and AF risk. For instance, an extensive cohort study of 28,449 AF-free individuals (mean follow-up: 4.5 ± 2.7 years) found that low HDL-C was independently associated with new-onset AF in women (48). Similarly, a cross-sectional analysis of 13,724 participants (including 708 with AF) demonstrated an inverse association between higher HDL-C levels and AF risk in individuals younger than 75 years (49).

The MHR reflects the balance between inflammation and oxidative stress, which is driven by the pro-inflammatory activity of monocytes and the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties of HDL-C. Many studies have established MHR as a significant predictor of both early and late recurrence of AF following catheter ablation (20, 25, 26, 29–31). Moreover, MHR is associated with AF occurrence, particularly in patients with new-onset AF after CABG or PCI (21–24, 27, 28, 32). In addition, a study by Deng et al. reported that elevated MHR is associated with the presence of left atrial appendage thrombus (LAAT) and spontaneous echo contrast (SEC) in patients with non-valvular AF, suggesting that MHR can serve as an independent predictor of LAAT or SEC in this population (50). Moreover, the degree of inflammation in AF patients is positively correlated with MHR levels (27, 51). Elevated MHR indicates a shift toward a net pro-remodeling state, characterized by increased inflammation, enhanced oxidative stress, and a higher fibrotic tendency (52). These factors collectively disrupt atrial electrophysiological and structural homeostasis, positioning MHR as a sensitive biomarker of the systemic pathological environment that develops during AF progression. Future research should explore specific inflammatory and oxidative stress pathways involved in AF development and progression, as well as the interactions between MHR and these pathways, thereby providing a foundation for developing targeted therapeutic strategies to reduce the incidence of AF.

This study aggregated data from various AF clinical scenarios to assess the predictive value of MHR, based on three primary rationales. First, inflammation and oxidative stress are core pathological mechanisms underlying AF, supporting the theoretical applicability of MHR across different scenarios. Second, all included studies utilized unified AF diagnostic criteria consistent with current clinical guidelines. Third, this approach aimed to systematically validate the broad clinical utility of MHR. However, this pooling introduced significant heterogeneity, which was not attributable to threshold effects (Spearman correlation, P = 0.067). Sample size significantly influenced diagnostic sensitivity: studies with larger samples (>600 patients) demonstrated lower pooled sensitivity than smaller studies (0.71 vs. 0.90, P = 0.02), suggesting that small-sample studies may overestimate sensitivity due to selection bias, whereas larger studies with rigorous designs provide more reliable results. The MHR cut-off value also affected sensitivity: a cut-off >15.44 was associated with lower sensitivity than a cut-off of 15.44 or less (0.72 vs. 0.92, P = 0.01), reflecting a diagnostic trade-off between reducing misdiagnosis and increasing missed diagnoses. The lack of a standardized MHR cut-off across studies further contributed to heterogeneity. Publication year primarily impacted specificity, with studies published after 2020 exhibiting lower specificity (0.64 vs. 0.73, P = 0.02), potentially due to more complex study populations (e.g., higher comorbidity prevalence) or the use of more lenient cut-offs, while sensitivity remained stable, confirming MHR's consistent ability to identify AF risk. This study thoroughly evaluated multiple potential sources of heterogeneity and confirmed subgroup analysis results using a joint model. Nevertheless, limited number of studies in some subgroups may have reduced statistical power, necessitating cautious interpretation. Additional unexplained heterogeneity may arise from differences in MHR detection methods, population characteristics, and clinical settings. Specifically, distinct inflammatory profiles and atrial remodeling processes associated with different AF phenotypes and these clinical contexts may also influence MHR's predictive performance, representing a key contributor to heterogeneity.

Several hematological indices, including the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) (53), lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio (LMR) (54), and systemic immune–inflammation index (SII) (55), have demonstrated predictive value in patients with AF. A key clinical question is which of these indices offers the most substantial predictive value for AF. Kutlay et al. conducted a retrospective study to investigate the relationship between hematological indices and AF risk, and found that MHR (AUC = 0.797) was significantly superior to NLR (AUC = 0.646), LMR (AUC = 0.659), and SII (AUC = 0.662) in predicting AF (28). In another retrospective study, Karataş et al. reported that MHR (AUC = 0.843) also exhibited greater predictive power for new-onset AF compared to NLR (AUC = 0.642) (21). These findings indicate that MHR provides a distinct advantage over other hematological markers in predicting AF.

Chen et al. recently conducted a meta-analysis of 21 studies involving 63,687 patients with AF to assess the prognostic value of traditional inflammatory markers derived from neutrophils, lymphocytes, and platelets—specifically the platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), NLR, and SII (56). This analysis confirmed that elevated NLR is significantly associated with the risk of adverse outcomes in AF patients, including all-cause mortality, stroke, AF recurrence, and left atrial thrombosis. However, evidence regarding PLR and SII remains limited and inconsistent across studies. By comparison, the present study examines the association between MHR, an emerging inflammatory-metabolic marker, and the risk of AF onset. While Chen et al. clarified the prognostic role of NLR in AF, the current findings emphasize the potential value of MHR in AF risk prediction. These studies are complementary in their research focus. Both analyses acknowledge limitations related to the number of included studies, methodological heterogeneity, and lack of standardization. Notably, the present results highlight the importance of metabolic factors in the comprehensive assessment of AF-related inflammatory markers. Collectively, these findings enhance understanding of the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying AF and provide a foundation for optimizing clinical risk stratification and management of AF patients.

This meta- analysis identifies a significant association between MHR and AF risk. Although MHR demonstrated high diagnostic sensitivity for AF, its moderate specificity and limited positive likelihood ratios indicate it is better suited as a screening or complementary biomarker rather than a standalone diagnostic tool. As AF is partially preventable (57), the development of novel risk-stratification biomarkers is essential for early identification and intervention. In clinical practice, MHR is particularly suitable for initial AF risk stratification in community or primary care settings because of its simplicity and cost-effectiveness. It helps identify individuals at high risk of AF, supporting timely lifestyle interventions or targeted electrocardiographic screening. However, in settings with low AF prevalence, such as the general population or routine outpatient clinics, the relatively high false-positive rate may result in unnecessary investigations, patient anxiety, and increased healthcare costs. Therefore, MHR is more appropriately applied to high- risk subgroups, such as patients after cardiac surgery or those with metabolic abnormalities. Preoperative monitoring of MHR can effectively predict AF occurrence or recurrence in patients undergoing catheter ablation or perioperative cardiac surgery, thereby informing decisions about intensive cardiac monitoring or prophylactic antiarrhythmic therapy. Combining MHR with established clinical risk parameters, such as the APPLE score, has been shown to further improve predictive accuracy for postoperative AF recurrence after catheter ablation (29). Whether the combination of MHR and the CHA2DS2-VASc score provides incremental value for stroke risk prediction in patients with non-valvular AF remains unresolved. The incremental prognostic value of MHR over established AF risk stratification scores is currently hypothetical. It requires prospective validation using quantitative metrics such as net reclassification improvement, integrated discrimination improvement, or decision curve analysis.

Several potential limitations should be considered in this meta-analysis. First, most included studies were retrospective, introducing unavoidable selection bias and residual confounding. Second, MHR cut-off values varied substantially across studies, likely reflecting differences in laboratory units and measurement methodologies. This variability may have impeded inconsistent diagnostic outcomes across institutions and hindered the standardized clinical implementation of MHR. Third, the QUADAS-2 assessment indicated that non-predefined or data-driven cut-off values may lead to overfitting, potentially overestimating diagnostic performance and compromising the robustness and generalizability of the pooled results. Fourth, the analysis relied solely on a single MHR measurement. Integrating MHR with additional biomarkers (e.g., hs-CRP, IL-6) and clinical scores (APPLE, CHA2DS2-VASc) using machine- learning models, as well as dynamic continuous MHR monitoring, may provide a more comprehensive assessment of disease status and improve predictive accuracy. Fifth, all included studies were conducted in China and Turkey, which may introduce regional selection bias. Future research should focus on multicentre prospective studies, standardisation of MHR detection protocols, development of universal diagnostic thresholds, and incorporation of dynamic monitoring to enhance clinical utility.

5 Conclusion

In conclusion, this meta-analysis demonstrates that elevated MHR is independently associated with a 21% increase in the risk of AF (OR = 1.21; 95% CI, 1.11–1.31; P < 0.001). The pooled sensitivity and specificity of MHR for AF prediction are 0.85 and 0.68, respectively, with an area under the SROC curve of 0.80, which suggests moderate diagnostic accuracy for AF risk prediction. MHR is more appropriately positioned as a screening or complementary biomarker rather than a standalone diagnostic tool for AF. Notably, the diagnostic performance of MHR may differ by AF phenotype and clinical context. However, given the limited number of included studies, lack of standardized measurement methods, and absence of unified reference ranges, future research should prioritize large-scale prospective studies, standardized methodologies, and the establishment of uniform cut-off thresholds. Beyond validating the predictive accuracy of MHR for AF risk, further efforts should aim to promote its routine implementation in clinical practice.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author contributions

XM: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YW: Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. XW: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. XY: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. LG: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFC3601301).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcvm.2026.1620841/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Figure S1Forest plot depicting the likelihood ratio of the MHR in predicting AF.

Supplementary Figure S2Forest plot depicting the diagnostic score and diagnostic odds ratio of the MHR in predicting AF.

References

1.

Tsao CW Aday AW Almarzooq ZI Anderson CAM Arora P Avery CL et al Heart disease and stroke statistics-2023 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. (2023) 147:e93–621. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001123

2.

Go AS Hylek EM Phillips KA Chang Y Henault LE Selby JV et al Prevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation in adults: national implications for rhythm management and stroke prevention: the AnTicoagulation and risk factors in atrial fibrillation (ATRIA) study. JAMA. (2001) 285:2370–5. 10.1001/jama.285.18.2370

3.

Lippi G Sanchis-Gomar F Cervellin G . Global epidemiology of atrial fibrillation: an increasing epidemic and public health challenge. Int J Stroke. (2021) 16:217–21. 10.1177/1747493019897870

4.

Lau DH Nattel S Kalman JM Sanders P . Modifiable risk factors and atrial fibrillation. Circulation. (2017) 136:583–96. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.023163

5.

Sagris M Vardas EP Theofilis P Antonopoulos AS Oikonomou E Tousoulis D . Atrial fibrillation: pathogenesis, predisposing factors, and genetics. Int J Mol Sci. (2021) 23:6. 10.3390/ijms23010006

6.

Heijman J Linz D Schotten U . Dynamics of atrial fibrillation mechanisms and comorbidities. Annu Rev Physiol. (2021) 83:83–106. 10.1146/annurev-physiol-031720-085307

7.

Ihara K Sasano T . Role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of atrial fibrillation. Front Physiol. (2022) 13:862164. 10.3389/fphys.2022.862164

8.

Hu YF Chen YJ Lin YJ Chen SA . Inflammation and the pathogenesis of atrial fibrillation. Nat Rev Cardiol. (2015) 12:230–43. 10.1038/nrcardio.2015.2

9.

Pfenniger A Yoo S Arora R . Oxidative stress and atrial fibrillation. J Mol Cell Cardiol. (2024) 196:141–51. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2024.09.011

10.

Guo Y Lip GY Apostolakis S . Inflammation in atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2012) 60:2263–70. 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.04.063

11.

Issac TT Dokainish H Lakkis NM . Role of inflammation in initiation and perpetuation of atrial fibrillation: a systematic review of the published data. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2007) 50:2021–8. 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.06.054

12.

Kanbay M Solak Y Unal HU Kurt YG Gok M Cetinkaya H et al Monocyte count/HDL cholesterol ratio and cardiovascular events in patients with chronic kidney disease. Int Urol Nephrol. (2014) 46:1619–25. 10.1007/s11255-014-0730-1

13.

Ganjali S Gotto AM Jr Ruscica M Atkin SL Butler AE Banach M et al Monocyte-to-HDL-cholesterol ratio as a prognostic marker in cardiovascular diseases. J Cell Physiol. (2018) 233:9237–46. 10.1002/jcp.27028

14.

Woollard KJ Geissmann F . Monocytes in atherosclerosis: subsets and functions. Nat Rev Cardiol. (2010) 7:77–86. 10.1038/nrcardio.2009.228

15.

Ghattas A Griffiths HR Devitt A Lip GY Shantsila E . Monocytes in coronary artery disease and atherosclerosis: where are we now?J Am Coll Cardiol. (2013) 62:1541–51. 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.07.043

16.

Ganjali S Momtazi AA Banach M Kovanen PT Stein EA Sahebkar A . HDL abnormalities in familial hypercholesterolemia: focus on biological functions. Prog Lipid Res. (2017) 67:16–26. 10.1016/j.plipres.2017.05.001

17.

Page MJ McKenzie JE Bossuyt PM Boutron I Hoffmann TC Mulrow CD et al The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Br Med J. (2021) 372:n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71

18.

Whiting PF Rutjes AW Westwood ME Mallett S Deeks JJ Reitsma JB et al QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. (2011) 155:529–36. 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00009

19.

Swets JA . Measuring the accuracy of diagnostic systems. Science. (1988) 240:1285–93. 10.1126/science.3287615

20.

Canpolat U Aytemir K Yorgun H Şahiner L Kaya EB Çay S et al The role of preprocedural monocyte-to-high-density lipoprotein ratio in prediction of atrial fibrillation recurrence after cryoballoon-based catheter ablation. Europace. (2015) 17:1807–15. 10.1093/europace/euu291

21.

Karataş MB Çanga Y İpek G Özcan KS Güngör B Durmuş G et al Association of admission serum laboratory parameters with new-onset atrial fibrillation after a primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Coron Artery Dis. (2016) 27:128–34. 10.1097/MCA.0000000000000333

22.

Saskin H Serhan Ozcan K Yilmaz S . High preoperative monocyte count/high-density lipoprotein ratio is associated with postoperative atrial fibrillation and mortality in coronary artery bypass grafting. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. (2017) 24:395–401. 10.1093/icvts/ivw376

23.

Tekkesin AI Hayiroglu MI Zehir R Turkkan C Keskin M Cinier G et al The use of monocyte to HDL ratio to predict postoperative atrial fibrillation after aortocoronary bypass graft surgery. North Clin Istanb. (2017) 4:145–50. 10.14744/nci.2017.53315

24.

Ulus T Isgandarov K Yilmaz AS Vasi I Moghanchızadeh SH Mutlu F . Predictors of new-onset atrial fibrillation in elderly patients with acute coronary syndrome undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Aging Clin Exp Res. (2018) 30:1475–82. 10.1007/s40520-018-0926-9

25.

Chen SA Zhang MM Zheng M Liu F Sun L Bao ZY et al The preablation monocyte/ high density lipoprotein ratio predicts the late recurrence of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation after radiofrequency ablation. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. (2020) 20:401. 10.1186/s12872-020-01670-3

26.

Adili A Wang Y Zhu X Cao H Fan F Tang X et al Preoperative monocyte-to-HDL-cholesterol ratio predicts early recurrence after radiofrequency maze procedure of valvular atrial fibrillation. J Clin Lab Anal. (2021) 35:e23595. 10.1002/jcla.23595

27.

Wang L Zhang Y Yu B Zhao J Zhang W Fan H et al The monocyte-to-high-density lipoprotein ratio is associated with the occurrence of atrial fibrillation among NAFLD patients: a propensity-matched analysis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). (2023) 14:1127425. 10.3389/fendo.2023.1127425

28.

Kutlay Ö Yalım Z Aktan AK . Inflammatory biomarkers derived from whole blood cell count in atrial fibrillation patients. Kardiologiia. (2023) 63:50–5. 10.18087/cardio.2023.8.n2336

29.

Song W Chen Y Chen XH Chen JH Xu Z Gong KZ et al Significance of the APPLE score and the monocyte-HDL cholesterol ratio in predicting late recurrence of atrial fibrillation following catheter ablation based on a retrospective study. BMJ Open. (2024) 14:e081808. 10.1136/bmjopen-2023-081808

30.

Aimaitijiang M Gulisitan A Zhai Z Atawula A Jiang C . The predictive value of monocyte-related inflammatory factors for recurrence of atrial fibrillation after cryoablation. Cryobiology. (2024) 116:104945. 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2024.104945

31.

Lei Y Hu L . The predictive value of monocyte count to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio combined with left atrial diameter for post-radiofrequency ablation recurrence of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation in patients. J Cardiothorac Surg. (2024) 19:670. 10.1186/s13019-024-03136-5

32.

Tanık VO Tunca Ç Kalkan K Kivrak A Özlek B . The monocyte-to-HDL-cholesterol ratio predicts new-onset atrial fibrillation in patients with acute STEMI. Biomark Med. (2025) 19:121–8. 10.1080/17520363.2025.2459590

33.

Hadi HA Alsheikh-Ali AA Mahmeed WA Suwaidi JM . Inflammatory cytokines and atrial fibrillation: current and prospective views. J Inflamm Res. (2010) 3:75–97. 10.2147/JIR.S10095

34.

Liu X Zhang W Luo J Shi W Zhang X Li Z et al TRIM21 deficiency protects against atrial inflammation and remodeling post myocardial infarction by attenuating oxidative stress. Redox Biol. (2023) 62:102679. 10.1016/j.redox.2023.102679

35.

Neuman RB Bloom HL Shukrullah I Darrow LA Kleinbaum D Jones DP et al Oxidative stress markers are associated with persistent atrial fibrillation. Clin Chem. (2007) 53:1652–7. 10.1373/clinchem.2006.083923

36.

Williams EA Russo V Ceraso S Gupta D Barrett-Jolley R . Anti-arrhythmic properties of non-antiarrhythmic medications. Pharmacol Res. (2020) 156:104762. 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.104762

37.

Medrano-Bosch M Simón-Codina B Jiménez W Edelman ER Melgar-Lesmes P . Monocyte-endothelial cell interactions in vascular and tissue remodeling. Front Immunol. (2023) 14:1196033. 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1196033

38.

Imhof BA Aurrand-Lions M . Adhesion mechanisms regulating the migration of monocytes. Nat Rev Immunol. (2004) 4:432–44. 10.1038/nri1375

39.

Yang J Zhang L Yu C Yang XF Wang H . Monocyte and macrophage differentiation: circulation inflammatory monocyte as biomarker for inflammatory diseases. Biomark Res. (2014) 2:1. 10.1186/2050-7771-2-1

40.

Mittal M Siddiqui MR Tran K Reddy SP Malik AB . Reactive oxygen species in inflammation and tissue injury. Antioxid Redox Signal. (2014) 20:1126–67. 10.1089/ars.2012.5149

41.

Dzeshka MS Lip GY Snezhitskiy V Shantsila E . Cardiac fibrosis in patients with atrial fibrillation: mechanisms and clinical implications. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2015) 66:943–59. 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.06.1313

42.

Lei M Salvage SC Jackson AP Huang CL . Cardiac arrhythmogenesis: roles of ion channels and their functional modification. Front Physiol. (2024) 15:1342761. 10.3389/fphys.2024.1342761

43.

Fontes ML Mathew JP Rinder HM Zelterman D Smith BR Rinder CS et al Atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery/cardiopulmonary bypass is associated with monocyte activation. Anesth Analg. (2005) 101:17–23. 10.1213/01.ANE.0000155260.93406.29

44.

Stannard AK Khan S Graham A Owen JS Allen SP . Inability of plasma high-density lipoproteins to inhibit cell adhesion molecule expression in human coronary artery endothelial cells. Atherosclerosis. (2001) 154:31–8. 10.1016/s0021-9150(00)00444-5

45.

Ouimet M Barrett TJ Fisher EA . HDL and reverse cholesterol transport. Circ Res. (2019) 124:1505–18. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.119.312617

46.

Rhainds D Tardif JC . From HDL-cholesterol to HDL-function: cholesterol efflux capacity determinants. Curr Opin Lipidol. (2019) 30:101–7. 10.1097/MOL.0000000000000589

47.

Jomard A Osto E . High density lipoproteins: metabolism, function, and therapeutic potential. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2020) 7:39. 10.3389/fcvm.2020.00039

48.

Watanabe H Tanabe N Yagihara N Watanabe T Aizawa Y Kodama M . Association between lipid profile and risk of atrial fibrillation. Circ J. (2011) 75:2767–74. 10.1253/circj.cj-11-0780

49.

Harrison SL Lane DA Banach M Mastej M Kasperczyk S Jóźwiak JJ et al Lipid levels, atrial fibrillation and the impact of age: results from the LIPIDOGRAM2015 study. Atherosclerosis. (2020) 312:16–22. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2020.08.026

50.

Deng Y Zhou F Li Q Guo J Cai B Li G et al Associations between neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio and monocyte to high-density lipoprotein ratio with left atrial spontaneous echo contrast or thrombus in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. (2023) 23:234. 10.1186/s12872-023-03270-3

51.

Satilmis S . Role of the monocyte-to-high-density lipoprotein ratio in predicting atrial high-rate episodes detected by cardiac implantable electronic devices. North Clin Istanb. (2018) 5:96–101. 10.14744/nci.2017.35761

52.

Arabi A Abdelhamid A Nasrallah D Al-Haneedi Y Assami D Alsheikh R et al Monocyte-to-HDL ratio (MHR) as a novel biomarker: reference ranges and associations with inflammatory diseases and disease-specific mortality. Lipids Health Dis. (2025) 24:343. 10.1186/s12944-025-02755-8

53.

Im SI Shin SY Na JO Kim YH Choi CU Kim SH et al Usefulness of neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio in predicting early recurrence after radiofrequency catheter ablation in patients with atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol. (2013) 168:4398–400. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.05.042

54.

Yang X Zhao S Wang S Cao X Xu Y Yan M et al Systemic inflammation indicators and risk of incident arrhythmias in 478,524 individuals: evidence from the UK biobank cohort. BMC Med. (2023) 21:76. 10.1186/s12916-023-02770-5

55.

Bağcı A Aksoy F . Systemic immune-inflammation index predicts new-onset atrial fibrillation after ST elevation myocardial infarction. Biomark Med. (2021) 15:731–9. 10.2217/bmm-2020-0838

56.

Chen X Zhang X Fang X Feng S . Association of inflammatory markers with clinical outcomes in atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2025) 12:1504163. 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1504163

57.

Du X Dong J Ma C . Is atrial fibrillation a preventable disease?J Am Coll Cardiol. (2017) 69:1968–82. 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.02.020

Summary

Keywords

atrial fibrillation, biomarker, inflammation, meta-analysis, monocyte-to-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio

Citation

Meng X, Wen Y, Wang X, Yang X and Gao L (2026) Predictive value of the monocyte-to-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio in atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 13:1620841. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2026.1620841

Received

01 May 2025

Revised

05 January 2026

Accepted

09 January 2026

Published

02 February 2026

Volume

13 - 2026

Edited by

Rui Providencia, University College London, United Kingdom

Reviewed by

Uğur Canpolat, Hacettepe University Faculty of Medicine, Türkiye

Veysel Ozan Tanik, Ankara Etlik City Hospital, Türkiye

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Meng, Wen, Wang, Yang and Gao.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Xiaolei Yang yangxl1012@yeah.net Lianjun Gao gaoljmd@126.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.