Abstract

Background:

The optimal revascularization approach for intermediate- and high-risk individuals with severe aortic stenosis (AS) and concomitant coronary artery disease (CAD) remains uncertain, particularly regarding the comparative short- and mid- to long-term outcomes of transcatheter aortic valve replacement with percutaneous coronary intervention (TAVR + PCI) vs. surgical aortic valve replacement with coronary artery bypass grafting (SAVR + CABG).

Methods:

A systematic search of major databases was conducted up to March 2025 to identify studies comparing TAVR + PCI vs. SAVR + CABG in this population. Meta-analyses were performed using a random-effects model to estimate pooled odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Evidence quality was assessed using the GRADE framework.

Results:

Thirteen studies comprising 53,869 patients were analyzed. Compared with SAVR + CABG, TAVR + PCI was associated with lower 30-day risks of stroke, myocardial infarction, and acute kidney injury, but higher permanent pacemaker implantation. No differences were found in all-cause mortality, major vascular complications, or major bleeding. In mid- to long-term follow-up (≥2 years), the TAVR + PCI group exhibited increased risks of all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction, and repeat revascularization, with similar stroke rates between strategies. Certainty of evidence ranged from very low to moderate.

Conclusions:

In intermediate- and high-risk patients with severe AS and concomitant CAD, TAVR + PCI appears to confer short-term safety advantages but may be associated with less favorable mid- to long-term outcomes compared with SAVR + CABG. These findings support individualized revascularization strategies that balance early procedural safety against longer-term risks and highlight the need for further randomized trials with extended follow-up.

Systematic Review Registration:

https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD420251000317, PROSPERO CRD420251000317.

1 Introduction

Severe aortic stenosis (AS) represents a prevalent valvular heart disease in the elderly, with incidence increasing significantly with age (1). Studies have reported that 15% to 81% of individuals with AS have concomitant coronary artery disease (CAD), with a higher prevalence observed in older populations (2–4). These patients experience increased cardiovascular risk due to impaired myocardial perfusion and left ventricular dysfunction (5, 6). Determining the optimal coronary revascularization approach in individuals undergoing aortic valve replacement remains a complex and unresolved clinical issue, particularly in those with advanced age and extensive coronary disease.

Traditionally, surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) with coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) has been considered the standard approach for eligible individuals, as it provides complete revascularization and durable valve function. Accordingly, SAVR combined with CABG has historically been favored in younger patients and those with acceptable surgical risk profiles (5, 6). However, SAVR + CABG is associated with higher surgical trauma, prolonged recovery, and increased perioperative complications, particularly in intermediate- and high-risk individuals. Recent advances in transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) have facilitated the widespread adoption of TAVR + PCI as a minimally invasive alternative, especially in elderly and high-risk populations (3, 7). According to the 2025 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the Management of Valvular Heart Disease, TAVR is recommended for anatomically suitable patients aged ≥70 years with tricuspid severe AS, while the choice between TAVR and SAVR in other candidates should be guided by a multidisciplinary Heart Team integrating clinical risk, anatomical feasibility, imaging findings, and patient preference (6). These evolving treatment strategies underscore the need for comparative evidence on the clinical outcomes of TAVR + PCI vs. SAVR + CABG in individuals with AS and concomitant CAD (8, 9).

Several studies have evaluated TAVR + PCI, with some comparing it to SAVR + CABG (10–13). However, most evidence has focused on short-term outcomes (e.g., mortality, stroke, acute kidney injury), while evidence beyond the early post-procedural period remains limited and heterogeneous (14–17). Although some studies have reported outcomes beyond two years, their findings are highly heterogeneous. From a clinical perspective, outcomes beyond two years are more appropriately considered mid-term rather than definitive long-term endpoints, particularly in the context of valve durability and coronary disease progression (17). Additionally, substantial heterogeneity exists across studies regarding patient risk stratification, revascularization strategies, and study designs, contributing to variability in reported outcomes (14). In particular, for patients with complex CAD (e.g., high SYNTAX scores), PCI may result in incomplete revascularization, potentially compromising mid- to long-term prognosis, whereas CABG may provide more sustained hemodynamic benefits (18). Against this background of heterogeneous and incomplete primary evidence, a rigorous synthesis of available data remains essential to clarify the relative benefits and limitations of contemporary interventional and surgical strategies.

Several meta-analyses have previously synthesized evidence comparing TAVR + PCI with SAVR + CABG in patients with AS and concomitant CAD, including those by Sakurai et al. (14), Baudo et al. (19), and Emara et al. (20). While these studies provided important insights into perioperative outcomes and overall survival, they differed substantially in inclusion periods, surgical risk profiles, follow-up definitions, and analytical approaches. In particular, most prior syntheses pooled heterogeneous patient populations across a broad risk spectrum or emphasized aggregate outcomes without predefined temporal stratification, thereby limiting their applicability to contemporary, guideline-based decision-making in intermediate- and high-risk patients. In contrast, the present study focuses specifically on intermediate- and high-risk individuals, as operationally defined by contemporary surgical risk models and clinical characteristics, and applies a structured comparison across predefined short-term and ≥2-year follow-up horizons. By incorporating evidence exclusively from randomized controlled trials and high-quality cohort studies, this meta-analysis aims to reduce clinical heterogeneity, enhance temporal interpretability of outcomes, and align evidence synthesis with current clinical practice patterns and evolving guideline recommendations.

This meta-analysis aims to systematically compare short- and mid- to long-term outcomes of TAVR + PCI vs. SAVR + CABG in intermediate- and high-risk patients with severe AS and concomitant CAD. By incorporating evidence from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and cohort studies, we seek to address existing heterogeneity and generate clinically relevant, methodologically rigorous conclusions to inform treatment selection, guide personalized decision-making, and support future updates to practice guidelines.

2 Methods

2.1 Protocol registration

This meta-analysis was conducted in adherence to the Cochrane Handbook and PRISMA 2020 guidelines (21), and was prospectively registered in PROSPERO (CRD420251000317). The PRISMA 2020 checklist is provided in Supplementary Table S1.

2.2 Search strategy

A comprehensive literature search was performed in PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library up to March 1, 2025. The search was guided by the PICOS framework, encompassing Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes, and Study design. Relevant MeSH terms and free-text keywords related to the interventions and comparators—such as “aortic stenosis”, “TAVR”, “PCI”, “SAVR”, and “CABG”—were employed. No restrictions were imposed on population, outcome, or study design to ensure comprehensive coverage. Supplementary Table S2 outlines the complete search strategy applied across all databases.

2.3 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Study eligibility was determined according to predefined PICOS criteria:

- (i)

Population

Severe AS: defined by at least one of the following: Imaging (e.g., echocardiography, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging) demonstrating an aortic valve area < 1.0 cm

2or mean pressure gradient ≥ 40 mmHg; confirmed by catheter-based or surgical intervention as severe aortic stenosis.

Coexisting CAD: Presence of at least one diameter stenosis > 70% in major coronary arteries and/or >50% diameter stenosis in the left main coronary artery, as assessed by invasive coronary angiography. Coronary computed tomography angiography findings were considered only if confirmed by invasive angiography or functionally significant (fractional flow reserve ≤ 0.80 or instantaneous wave-free ratio ≤ 0.89).

Risk Stratification: Intermediate- and high-risk individuals were identified based on surgical risk, clinical characteristics, and anatomical burden, meeting at least one of the following criteria:

(1) Age ≥75 years; (2) age ≥70 years with additional high-risk features (e.g., frailty, significant comorbidities); (3) EuroSCORE II ≥4% or STS score ≥4%; (4) multivessel or complex coronary artery disease (e.g., SYNTAX score >22, left main plus LAD disease, or three-vessel disease); (5) comorbidities known to increase surgical risk—such as diabetes, chronic kidney disease with eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, malignancy, or cognitive impairment; (6) left ventricular ejection fraction ≤35%; (7) New York Heart Association class III or IV.

These criteria were used to operationalize intermediate- or high-risk status for study inclusion, informed by established surgical risk models (including STS-PROM and EuroSCORE II) and the conceptual framework of contemporary guidelines, rather than to define treatment-recommendation thresholds.

- (ii)

Intervention

- (iii)

Comparison

- (iv)

Outcomes

Short-term outcomes: 30-day all-cause mortality, 30-day myocardial infarction, 30-day stroke, 30-day acute kidney injury, 30-day major vascular complications, 30-day major bleeding, and 30-day permanent pacemaker implantation.

Mid- to long-term outcomes (≥2 years): all-cause mortality during follow-up, myocardial infarction during follow-up, revascularization during follow-up, stroke during follow-up.

Outcome definitions were prespecified to follow those reported in the original studies. To avoid potential bias, no

post hocreclassification was performed. To ensure transparency, all outcome definitions were systematically extracted and are summarized in

Supplementary Table S3(short-term outcomes) and

Supplementary Table S4(mid- to long-term outcomes), allowing readers to assess potential heterogeneity.

- (v)

Study design

Published RCTs and cohort studies.

Exclusion Criteria: Low-risk patients (EuroSCORE II <4% or STS score <4%) and studies assessing isolated TAVR, PCI, SAVR, or CABG were excluded. Hybrid revascularization strategies (e.g., minimally invasive or robotic-assisted CABG + PCI) were excluded. Studies without extractable data on short- or mid- to long-term outcomes were excluded. For overlapping patient populations, RCTs were prioritized over observational studies. If multiple observational studies shared overlapping populations, priority was given to those featuring a greater number of participants, extended duration of follow-up, or more rigorous statistical adjustments (e.g., propensity score matching) to minimize bias and ensure analytical consistency. Non-original research, including case reports, letters, editorials, conference abstracts, review articles, unpublished data, and non-English studies, was excluded.

2.4 Literature screening and data extraction

Data extraction was independently performed by XF and XGZ. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion or consultation with a third author (XMC) until consensus was reached. The extracted data included: author and year, country/region, study design, follow-up duration, sample size, patient age, sex, baseline comorbidities, TAVR approach, time interval between PCI and TAVR procedures, risk stratification, and clinical outcomes. The definitions of short-term and mid- to long-term outcomes were adopted as reported in the original studies. To enhance transparency and allow comparison of heterogeneity in event classification, the specific definitions used across included studies are summarized in Supplementary Table S3 (short-term outcomes) and Supplementary Table S4 (mid- to long-term outcomes).

2.5 Risk of bias within studies

For RCTs, the risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration's Risk of Bias tool, which evaluates five key domains: randomization process, allocation concealment, blinding, outcome data completeness, and reporting bias (22). For cohort studies, the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) was employed to evaluate study quality across three domains: selection, comparability, and outcome assessment, with higher scores reflecting a lower risk of bias (23). Studies with scores ≥7 were considered of high quality. Discrepancies in the assessment process were resolved by consensus or, if consensus could not be reached, through arbitration by a third author.

2.6 Data analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Review Manager (version 5.4, Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK). For short-term binary outcomes, odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used. For mid- to long-term outcomes (≥2 years), hazard ratios (HRs) were prespecified as the preferred effect measure. Where HRs were not reported and Kaplan–Meier curves were unavailable for estimation, crude event counts were extracted and ORs were calculated as an alternative effect measure. Between-study heterogeneity was evaluated using Cochran's Q and the I2 statistic, with heterogeneity considered substantial if the Q test P-value was <0.10 or I2 exceeded 50%. In such cases, a random-effects model was applied to derive pooled estimates. Sensitivity analyses and risk of bias assessments were conducted to ensure result robustness. Where applicable, subgroup analyses explored sources of heterogeneity based on study design, follow-up time, and sample size. Funnel plots were generated in RevMan to visualize potential publication bias. For outcomes reported in ≥3 studies, Egger's regression test (Stata version 18.0, StataCorp) was used to quantify small-study effects, with P < 0.05 indicating significant asymmetry.

2.7 GRADE assessment

Evidence quality for both short- and mid- to long-term outcomes was appraised using the GRADE framework (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation), which considers study design, risk of bias, consistency, directness, precision, and publication bias. Based on these domains, evidence was rated as high, moderate, low, or very low quality (24).

3 Results

3.1 Study selection and Patients' characteristics

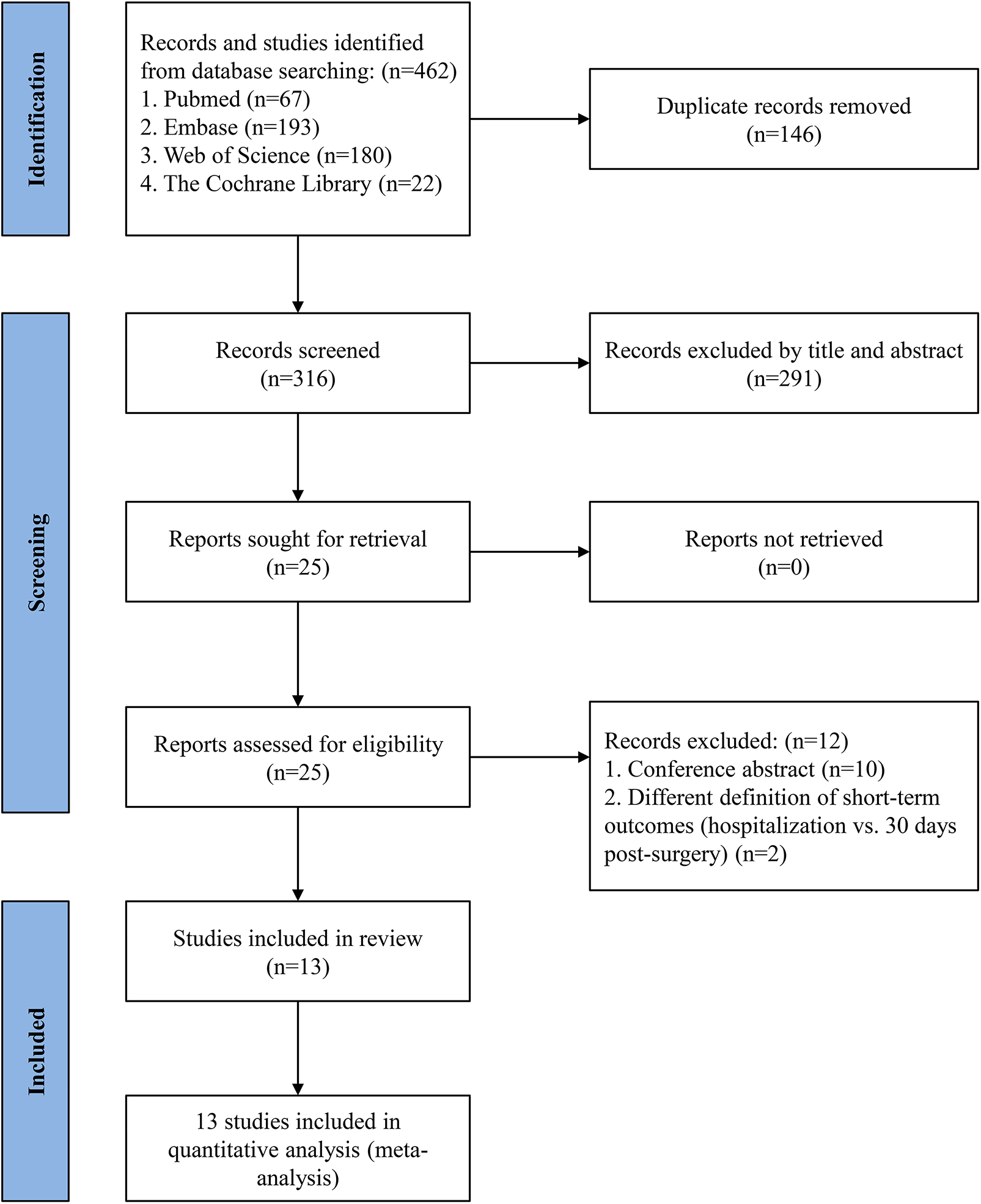

A comprehensive literature search identified 462 articles, including 67 from PubMed, 193 from Embase, 22 from the Cochrane Library, and 180 from Web of Science. After full-text review of 25 records, 10 conference abstracts and 2 studies defining short-term outcomes as those occurring during hospitalization were excluded, as they did not align with the 30-day post-operative definition used in this analysis. Ultimately, 13 studies (25–37) were included, comprising a total of 53,869 patients — 24,913 receiving TAVR + PCI and 28,956 undergoing SAVR + CABG.

The 13 included studies comprised 2 RCTs (26, 34) and 11 cohort studies (25, 27–33, 35–37) (3 prospective and 8 retrospective). Included individuals had a mean age of 75.1 years, with 60.1% were being male (n = 32,377). The duration of follow-up varied across studies, ranging from 30 days to 9.2 years. A summary of study characteristics and patient demographics is presented in Tables 1, 2. Figure 1 outlines the study selection process, while the risk of bias assessment is detailed in Supplementary Figure S1 and Supplementary Table S5.

Table 1

| Author (Year) | Study design | Region | Intervention treatment | Control group | Total sample size (N) | TAVR approach | PCI-to-TAVR interval | Patient risk classification | Follow-up duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taghiyev et al. (25) | Retrospective cohort | Germany | TAVR + PCI | SAVR + CABG | 80 | Transfemoral | All PCI procedures were conducted within a 90-day window preceding TAVR or concurrently with the TAVR procedure | Intermediate risk | 9.2 years |

| Kedhi et al. (26) | RCT | Europe | TAVR + FFR-guided PCI | SAVR + CABG | 172 | Transfemoral and transsubclavian | All PCI procedures were conducted within a 40-day window preceding TAVR or concurrently with the TAVR procedure | High risk | 1 year |

| Jagadeesan et al. (27) | Retrospective cohort | United States | TAVR + PCI | SAVR + CABG | 37,822 | Transfemoral | Elective PCI performed within 3 months before or after TAVR; Non-emergent PCI conducted during TAVR hospitalization | Intermediate and high risk | 5 years |

| Amat-Santos et al. (28) | Retrospective cohort | Spain | TAVR + PCI | SAVR + CABG | 508 | Transfemoral | All PCI procedures were conducted within a 40-day window preceding TAVR or concurrently with the TAVR procedure | Intermediate and high risk | 5 years |

| Ullah et al. (29) | Retrospective cohort | United States | TAVR + PCI | SAVR + CABG | 11,361 | Transfemoral and transapical | All PCI procedures were performed either within a 3 months period preceding the TAVR procedure or concurrently with the TAVR procedure. | High risk | 30 days |

| McInerney et al. (30) | Retrospective cohort | Spain | TAVR + PCI | SAVR + CABG | 1,548 | NA | All PCI procedures were performed within 6 months prior to TAVR | Intermediate and high risk | 30 days |

| Lérault et al. (31) | Retrospective cohort | France | TAVR + PCI | SAVR + CABG | 241 | Transfemoral, transcarotid, transsubclavian, transaortic, and transapical | NA | High risk | 3.3 years |

| Elderia et al. (32) | Retrospective cohort | Germany | TAVR + PCI | SAVR + CABG | 478 | Transfemoral, transapical, and transsubclavian/axillary | All PCI procedures were performed within 6 months prior to TAVR | High risk | 30 days |

| Alperi et al. (33) | Retrospective cohort | North America and Europe | TAVR + PCI | SAVR + CABG | 312 | Transfemoral | All PCI procedures were performed within 3 months prior to TAVR or concurrently with the TAVR procedure | Intermediate risk | 5 years |

| Søndergaard et al. (34) | RCT | United States, Canada, and Europe | TAVR + PCI | SAVR + CABG | 332 | Transfemoral and transapical | All PCI procedures were performed within 7 days prior to TAVR | Intermediate risk | 2 years |

| Baumbach et al. (35) | Prospective cohort | Germany | TAVR + PCI | SAVR + CABG | 576 | Transfemoral and transapical | All PCI procedures were conducted within a 12 months window preceding TAVR | High risk | 30 days |

| Barbanti et al. (36) | Prospective cohort | Italy | TAVR + PCI | SAVR + CABG | 472 | Transfemoral | All PCI procedures were performed within 6 months prior to TAVR, or PCI and TAVR performed concurrently in the same session | Intermediate and high risk | 3 years |

| Wendt et al. (37) | Prospective cohort | Germany | TAVR + PCI | SAVR + CABG | 243 | Transfemoral and transapical | All PCI procedures were performed within 12 months before TAVR | High risk | 6 years |

Characteristics of included studies.

TAVR, rranscatheter aortic valve replacement; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; SAVR, surgical aortic valve replacement; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; RCT, randomized controlled trial; FFR, fractional flow reserve; NA, not available.

Table 2

| Author (year) | Total sample size (N) | I/C (n) | Mean age (years) I/C | Male, n (%) I/C | Hypertension, n (%) I/C | Diabetes, n (%) I/C | CKD, n (%) I/C | LVEF, mean ± SD (%) I/C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taghiyev et al. (25) | 80 | 40/40 | 79.6/78.3 | 26 (65.0)/32 (80.0) | NA | NA | NA | 55.5 ± 9.2/52.4 ± 11.5 |

| Kedhi et al. (26) | 172 | 91/81 | 76.3/76.6 | 59 (64.8)/59 (72.8) | 69 (75.8)/65 (80.2) | 27 (29.6)/27 (33.3) | 15 (16.5)/15 (18.5) | 54.6 ± 9.4/54.4 ± 8.8 |

| Jagadeesan et al. (27) | 37,822 | 17,413/20,409 | 77.1/72.7 | 11,192 (64.3)/15,734 (77.1) | NA | 7,574 (43.5)/8,533 (41.8) | 5,715 (32.8)/4,839 (23.7) | NA |

| Amat-Santos et al. (28) | 508 | 254/254 | 77.9/77.4 | 88 (34.6)/80 (31.5) | NA | 118 (46.5)/114 (44.9) | 99 (39.0)/51 (20.1) | 55.2 ± 12.7/57.1 ± 11.0 |

| Ullah et al. (29) | 11,361 | 5,358/6,003 | 79.6/70.2 | 2,357 (44.0)/394 (6.6) | 4,755 (88.7)/5,088 (84.8) | 842 (15.7)/1,043 (17.4) | 2,176 (40.6)/573 (9.5) | NA |

| McInerney et al. (30) | 1,548 | 774/774 | 79.7/80.3 | 493 (63.7)/439 (56.7) | 446 (57.6)/391 (50.5) | 318 (41.1)/348 (45) | 155 (20.0)/226 (29.2) | NA |

| Lérault et al. (31) | 241 | 150/91 | 84.0/73.0 | 89 (59.3)/67 (73.6) | 115 (76.7)/75 (82.4) | 61 (40.7)/46 (50.5) | NA | 60.0 ± 11.9/60 ± 8.2 |

| Elderia et al. (32) | 478 | 237/241 | 81.4/71.9 | 140 (59.1)/185 (76.8) | 220 (92.8)/228 (94.6) | 76 (32.0)/95 (39.4) | 41 (17.2)/48 (19.9) | NA |

| Alperi et al. (33) | 312 | 156/156 | 79.5/79.0 | 90 (66.5)/85 (64) | 167 (84.8)/163 (82.7) | 72 (46.2)/63 (40.4) | NA | 52.1 ± 13.2/52.9 ± 12.9 |

| Søndergaard et al. (34) | 332 | 169/163 | 79.5 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Baumbach et al. (35) | 576 | 112/464 | 81.3/78.7 | NA | 73 (65.2)/296 (63.8) | 33 (29.5)/180 (38.8) | 56 (51.1)/123 (26.5) | 51.3 ± 2.6/55.7 ± 13.8 |

| Barbanti et al. (36) | 472 | 236/236 | 80.7/80.5 | 128 (54.2)/132 (55.9) | NA | 77 (32.6)/80 (33.9) | NA | NA |

| Wendt et al. (37) | 243 | 59/184 | 80.0/75.0 | 26 (44.1)/84(45.7) | NA | 19(32.2)/36 (19.6) | NA | 49.4 ± 13.0/53.4 ± 12.5 |

Patient demographics and baseline clinical characteristics.

I, intervention group; C, control group; NA, not available; CKD, chronic kidney disease; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; SD, standard deviation.

Figure 1

PRISMA flow diagram of study selection.

The two RCTs were assessed with the Cochrane Collaboration's Risk of Bias tool and showed low risk of bias, while the 11 cohort studies scored 7–9 on the NOS, indicating high quality.

3.2 Short-term outcomes

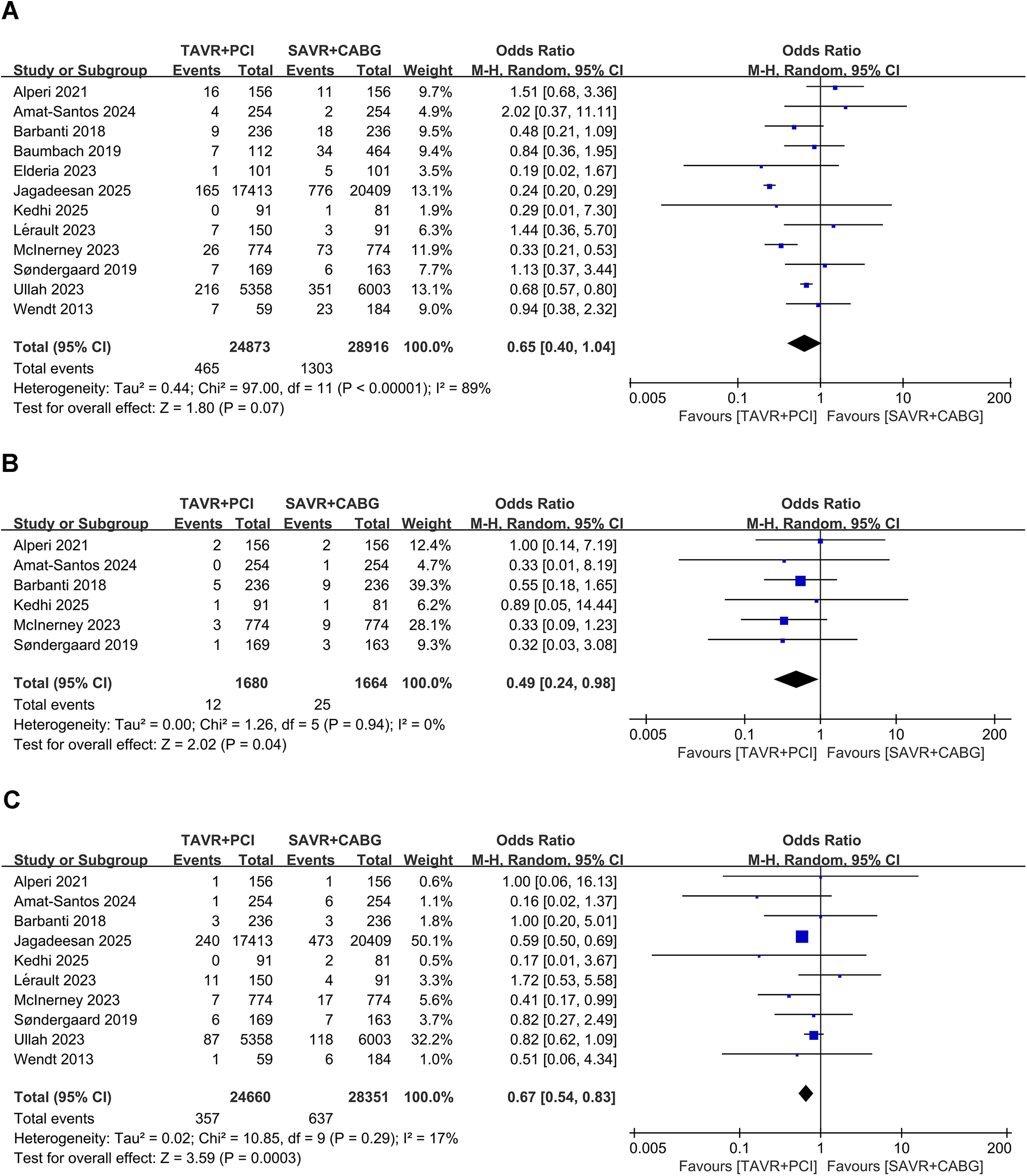

3.2.1 30-day all-cause mortality

Twelve studies involving 53,789 patients (TAVR + PCI: 24,873; SAVR + CABG: 28,916) were analyzed. Pooled analysis showed no significant difference between groups (OR, 0.65; 95% CI: 0.40–1.04, P = 0.07) with substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 89%, P < 0.00001) (Figure 2A). Funnel plot analysis indicated symmetry (Supplementary Figure S2A), and Egger's test (P = 0.270) did not suggest significant publication bias.

Figure 2

Forest plots for short-term clinical outcomes in intermediate- and high-risk patients undergoing TAVR + PCI vs. SAVR + CABG. (A) 30-day all-cause mortality, (B) 30-day myocardial infarction, and (C) 30-day stroke.

3.2.2 30-day myocardial infarction

Six studies involving 3,344 patients (TAVR + PCI: 1,680; SAVR + CABG: 1,644) were analyzed. Pooled analysis showed a significantly lower risk of 30-day myocardial infarction in the TAVR + PCI group (OR, 0.49; 95% CI: 0.24–0.98, P = 0.04) with no heterogeneity (I2 = 0%, P = 0.94) (Figure 2B). Funnel plot analysis indicated symmetry (Supplementary Figure S2B), and Egger's test (P = 0.811) suggested no publication bias.

3.2.3 30-day stroke

Ten studies involving 53,011 patients (TAVR + PCI: 24,660; SAVR + CABG: 28,351) were analyzed. The risk of 30-day stroke was significantly reduced in the TAVR + PCI group compared with SAVR + CABG (OR, 0.67; 95% CI: 0.54–0.83, P = 0.0003), with low heterogeneity (I2 = 17%, P = 0.29) (Figure 2C). Funnel plot analysis demonstrated good symmetry (Supplementary Figure S2C), and Egger's test (P = 0.890) indicated no significant publication bias.

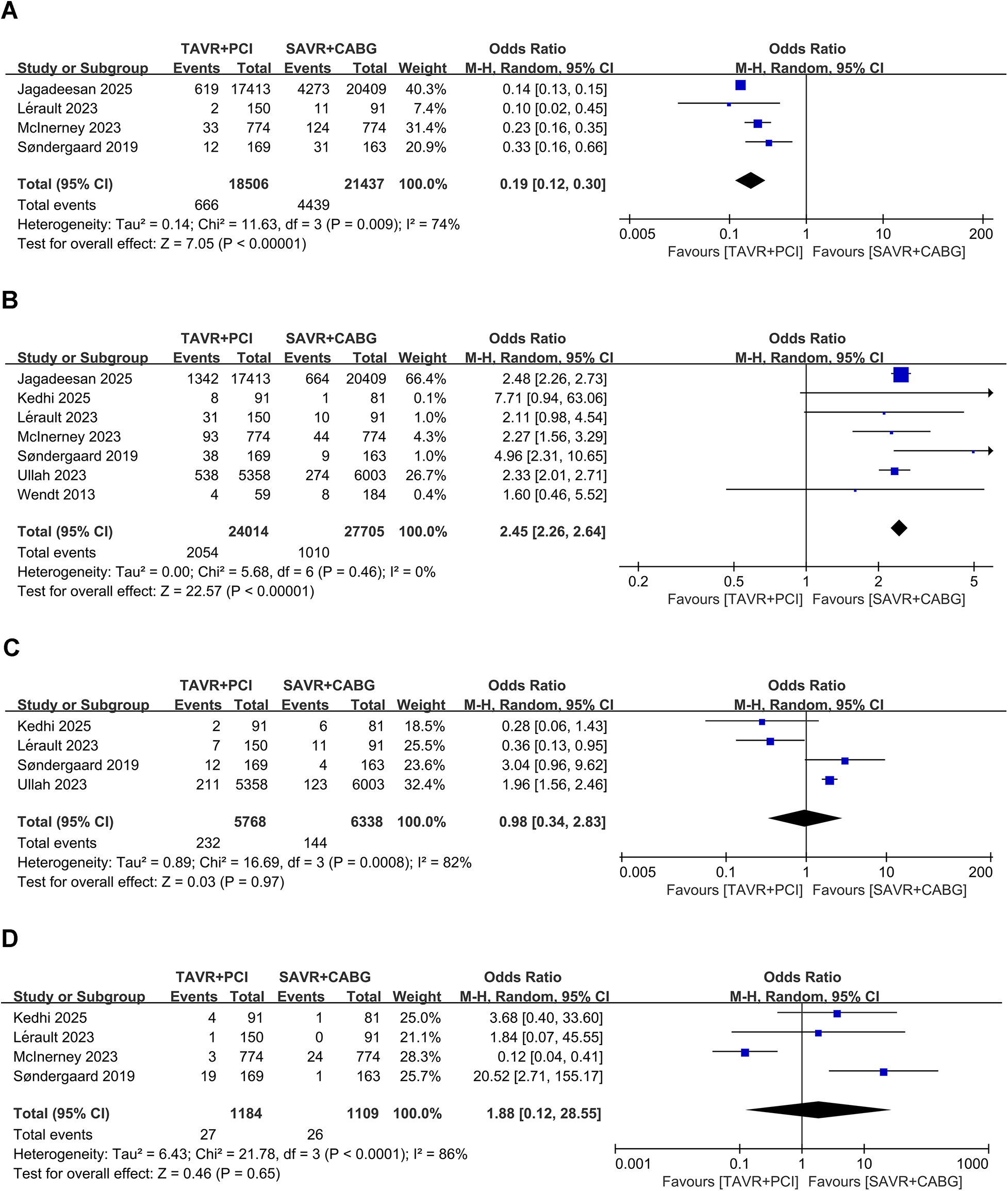

3.2.4 30-day acute kidney injury

Four studies involving 39,943 patients (TAVR + PCI: 18,506; SAVR + CABG: 21,437) were analyzed. TAVR + PCI was associated with a significantly lower incidence of 30-day acute kidney injury compared with SAVR + CABG (OR, 0.19; 95% CI: 0.12–0.30, P < 0.00001), although substantial heterogeneity existed (I2 = 74%, P = 0.009) (Figure 3A). Funnel plot analysis suggested symmetry (Supplementary Figure S3A), and Egger's test (P = 0.326) did not indicate significant publication bias.

Figure 3

Forest plots for short-term procedural complications in intermediate- and high-risk patients undergoing TAVR + PCI vs. SAVR + CABG. (A) 30-day acute kidney injury, (B) 30-day permanent pacemaker implantation, (C) 30-day major bleeding, and (D) 30-day major vascular complications.

3.2.5 30-day permanent pacemaker implantation

Seven studies involving 51,719 patients (TAVR + PCI: 24,014, SAVR + CABG: 27,705) were analyzed. Pooled analysis showed a significantly higher 30-day permanent pacemaker implantation rate in the TAVR + PCI group (OR, 2.45; 95% CI: 2.26–2.64, P < 0.00001), with no heterogeneity (I2 = 0%, P = 0.46) (Figure 3B). Funnel plot showed symmetry (Supplementary Figure S3B), and Egger's test (P = 0.586) suggested no significant publication bias.

3.2.6 30-day major bleeding

Four studies involving 12,106 patients (TAVR + PCI: 5,768, SAVR + CABG: 6,338) were analyzed. The pooled analysis showed no significant difference in the risk of 30-day major bleeding between TAVR + PCI and SAVR + CABG (OR, 0.98; 95% CI: 0.34–2.83; P = 0.97), although substantial heterogeneity was observed (Figure 3C). Funnel plot showed symmetry (Supplementary Figure S3C), and Egger's test (P = 0.336) indicated no significant publication bias.

3.2.7 30-day major vascular complications

Four studies involving 2,293 patients (TAVR + PCI: 1,184, SAVR + CABG: 1,109) were analyzed. Pooled results showed no significant difference between groups (OR, 1.88; 95% CI: 0.12–28.55, P = 0.65), with substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 74%, P < 0.001) (Figure 3D). Funnel plot showed symmetry (Supplementary Figure S3D), and Egger's test (P = 0.269) suggested no significant publication bias.

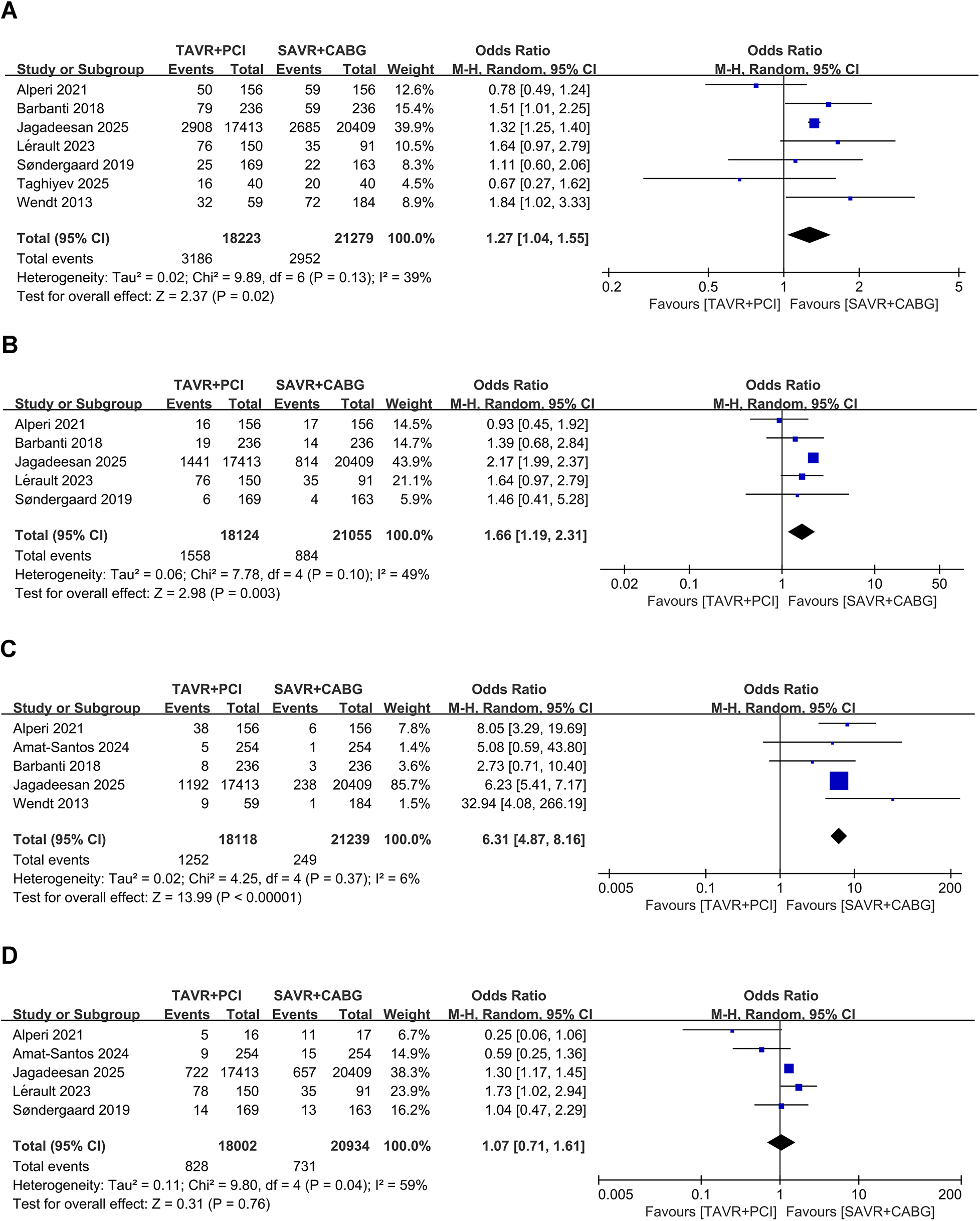

3.3 Mid- to long-term outcomes

3.3.1 All-cause mortality during follow-up

Seven studies that included 39,502 patients (TAVR + PCI: 18,223, SAVR + CABG: 21,279) were analyzed. Pooled analysis showed higher all-cause mortality during follow-up in the TAVR + PCI group (OR, 1.27; 95% CI: 1.04–1.55, P = 0.02), with low heterogeneity (I2 = 39%, P = 0.13) (Figure 4A). Funnel plot appeared symmetrical (Supplementary Figure S4A), and Egger's test revealed no evidence of significant publication bias (P = 0.616).

Figure 4

Forest plots for mid- to long-term outcomes in intermediate- and high-risk patients undergoing TAVR + PCI vs. SAVR + CABG. (A) All-cause mortality during follow-up, (B) myocardial infarction during follow-up, (C) revascularization during follow-up, and (D) stroke during follow-up.

3.3.2 Myocardial infarction during follow-up

Five studies including 39,179 patients (TAVR + PCI: 18,124, SAVR + CABG: 21,055) were analyzed. Pooled analysis showed a significantly higher risk of myocardial infarction during follow-up in the TAVR + PCI group (OR, 1.66; 95% CI: 1.19–2.31, P = 0.003), with low heterogeneity (I2 = 49%, P = 0.10) (Figure 4B). However, funnel plot asymmetry was observed (Supplementary Figure S4B), and Egger's test (P = 0.013) indicated significant publication bias.

3.3.3 Revascularization during follow-up

Four studies that included 38,849 patients (TAVR + PCI: 17,864, SAVR + CABG: 20,985) were analyzed. Pooled analysis showed a significantly higher revascularization incidence during follow-up in the TAVR + PCI group (OR, 6.49; 95% CI: 4.08–10.33, P < 0.00001), with no significant heterogeneity (I2 = 29%, P = 0.24) (Figure 4C). The funnel plot appeared symmetrical (Supplementary Figure S4C), and Egger's test (P = 0.772) indicated no substantial publication bias.

3.3.4 Stroke during follow-up

Five studies involving 38,936 patients (TAVR + PCI: 18,002, SAVR + CABG: 20,934) were analyzed. Pooled analysis indicated no significant difference in stroke incidence during follow-up between TAVR + PCI and SAVR + CABG (OR, 1.23; 95% CI 0.88–1.73; P = 0.23), with moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 44%, P = 0.15) (Figure 4D). Funnel plot showed no apparent asymmetry (Supplementary Figure S4D), and Egger's test indicated no significant publication bias (P = 0.27).

3.4 Subgroup analyses

Subgroup analyses were conducted based on prespecified variables, including study design (randomized controlled trials vs. observational studies), sample size (<300 vs. ≥300 participants), and follow-up duration (<5 years vs. ≥5 years). For mid- to long-term all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction, and stroke, a significantly higher risk associated with TAVR + PCI was observed in studies with ≥5 years of follow-up, indicating a potential time-dependent trend. In the analysis of 30-day major bleeding, studies with smaller sample sizes favored TAVR + PCI, whereas larger studies showed the opposite effect, suggesting a possible small-study bias. Detailed results of these subgroup analyses are presented in Table 3 (short-term outcomes) and Table 4 (mid- to long-term outcomes). For other outcomes with high statistical heterogeneity—such as 30-day all-cause mortality, acute kidney injury, and major vascular complications—no consistent subgroup effects were observed across prespecified variables. Although several included studies reported the timing of PCI relative to TAVR, the intervals varied substantially—from a few days to over 12 months—and were inconsistently reported. This procedural heterogeneity likely reflects differences in clinical presentation and institutional protocols, and precluded reliable stratified analysis based on revascularization timing. Similarly, coronary anatomical complexity (e.g., SYNTAX score, left main disease) was not consistently reported across studies, limiting our ability to assess subgroup effects by lesion burden.

Table 3

| Subgroup | 30-day all-cause mortality | 30-day myocardial infarction | 30-day stroke | 30-day major vascular complications | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | OR (95%CI) | P value | I 2 | Study | OR (95%CI) | P value | I 2 | Study | OR (95%CI) | P value | I 2 | Study | OR (95%CI) | P value | I 2 | |

| Total | 12 | 0.65 (0.40,1.04) | 0.07 | 89% | 6 | 0.49 (0.24,0.98) | 0.04 | 0% | 10 | 0.67 (0.54,0.83) | 0.0003 | 17% | 4 | 1.88 (0.12,18.18) | 0.65 | 86% |

| Study design | ||||||||||||||||

| RCT | 2 | 0.98 (0.34,2.80) | 0.97 | 0% | 2 | 0.48 (0.08,2.79) | 0.41 | 0% | 2 | 0.68 (0.24,1.94) | 0.48 | 0% | 2 | 9.20 (1.63,52.03) | 0.01 | 26% |

| Cohort | 10 | 0.63 (0.38,1.04) | 0.07 | 90% | 4 | 0.49 (0.23,1.05) | 0.07 | 0% | 8 | 0.67 (0.52,0.87) | 0.003 | 30% | 2 | 0.31 (0.02,3.88) | 0.36 | 59% |

| Sample size | ||||||||||||||||

| <300 participants | 4 | 0.84 (0.42,1.69) | 0.63 | 0% | 1 | 0.89 (0.05,14.44) | 0.93 | / | 3 | 0.92 (0.28,3.02) | 0.89 | 19% | 2 | 2.94 (0.48,18.18) | 0.25 | 0% |

| ≥300 participants | 8 | 0.63 (0.37,1.07) | 0.09 | 92% | 5 | 0.47 (0.23,0.96) | 0.04 | 0% | 7 | 0.65 (0.53,0.81) | <0.0001 | 18% | 2 | 1.48 (0.01,271.89) | 0.88 | 95% |

| Subgroup | 30-day acute kidney injury | 30-day major bleeding | 30-day permanent pacemaker implantation | |||||||||||||

| Study | OR (95% CI) | P value | I 2 | Study | OR (95% CI) | P value | I 2 | Study | OR (95% CI) | P value | I 2 | |||||

| Total | 4 | 0.19 (0.12,0.30) | <0.00001 | 74% | 4 | 0.98 (0.34,2.83) | 0.97 | 82% | 7 | 2.45 (2.26,2.64) | <0.00001 | 0% | ||||

| Study design | ||||||||||||||||

| RCT | 1 | 0.33 (0.16,0.66) | 0.002 | / | 2 | 0.99 (0.10,10.21) | 1.00 | 82% | 2 | 5.22 (2.55,10.70) | <0.00001 | 0% | ||||

| Cohort | 3 | 0.17 (0.11,0.26) | <0.00001 | 69% | 2 | 0.90 (0.17,4.74) | 0.90 | 91% | 5 | 2.42 (2.24,2.62) | <0.00001 | 0% | ||||

| Sample size | ||||||||||||||||

| <300 participants | 1 | 0.10 (0.12,0.30) | <0.00001 | 74% | 2 | 0.33 (0.14,0.78) | 0.01 | 0% | 3 | 2.20 (1.18,4.11) | 0.01 | 0% | ||||

| ≥300 participants | 3 | 0.20 (0.12,0.34) | <0.00001 | 82% | 2 | 1.99 (1.60,2.48) | <0.00001 | 0% | 4 | 2.45(2.19,2.73) | <0.00001 | 24% | ||||

Subgroup analysis of short-term outcomes in intermediate- and high-risk patients undergoing TAVR + PCI vs. SAVR + CABG.

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; RCT, randomized controlled trial; I², heterogeneity index.

Table 4

| Subgroup | All-cause mortality during follow-up | Myocardial infarction during follow-up | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | OR (95% CI) | P value | I 2 | Study | OR (95% CI) | P value | I 2 | |

| Total | 7 | 1.27 (1.04,1.55) | 0.02 | 39% | 5 | 1.66 (1.19,2.31) | 0.003 | 49% |

| Follow-up | ||||||||

| <5 years | 3 | 1.24 (0.78,1.96) | 0.36 | 66% | 3 | 1.36 (0.94,1.96) | 0.10 | 0% |

| ≥5 years | 4 | 1.30 (1.05,1.61) | 0.02 | 21% | 2 | 2.17 (1.98,2.37) | <0.00001 | 0% |

| Sample size | ||||||||

| <300 participants | 3 | 1.39 (0.83,2.33) | 0.21 | 47% | 1 | 1.64 (0.97,2.79) | 0.07 | / |

| ≥300 participants | 4 | 1.22 (0.96,1.54) | 0.10 | 47% | 4 | 1.58 (1.00,2.49) | 0.05 | 56% |

| Subgroup | Stroke during follow-up | Revascularization during follow-up | ||||||

| Study | OR (95% CI) | P value | I 2 | Study | OR (95% CI) | P value | I 2 | |

| Total | 4 | 1.23 (0.88,1.73) | 0.23 | 44% | 4 | 6.49 (4.08,10.33) | <0.00001 | 29% |

| Follow-up | ||||||||

| <5 years | 2 | 0.95 (0.25,3.62) | 0.94 | 80% | 2 | 5.28 (1.87,14.90) | 0.002 | 43% |

| ≥5 years | 2 | 1.30 (1.16,1.44) | <0.00001 | 0% | 2 | 10.20 (2.30,45.27) | 0.002 | 59% |

| Sample size | ||||||||

| <300 participants | / | / | / | / | 1 | 32.94 (4.08,266.19) | 0.001 | / |

| ≥300 participants | / | / | / | / | 3 | 6.21 (5.41,7.13) | <0.00001 | 0% |

Subgroup analysis of Mid- to long-term outcomes in intermediate- and high-risk patients undergoing TAVR + PCI vs. SAVR + CABG.

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; I2, heterogeneity index.

3.5 Sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity analyses were conducted using leave-one-out procedures to assess the robustness of the pooled estimates. For most outcomes, sequential exclusion of individual studies yielded consistent results, indicating overall stability. An exception was observed in the analysis of 30-day major vascular complications, where omission of the study by McInerney et al. (30) substantially increased the pooled effect size (OR, 6.83; 95% CI: 1.61–28.95), suggesting high sensitivity to this study. Additional sensitivity tests were performed by excluding studies with disproportionately high weights or potential concerns regarding cohort overlap or inconsistent endpoint definitions. These analyses demonstrated that the direction and magnitude of treatment effects remained largely unchanged, supporting the reliability of the overall findings. The full leave-one-out sensitivity results are presented in Supplementary Figures S5–S7.

3.6 GRADE evidence quality assessment

This meta-analysis assessed 11 clinical outcomes across short- and mid- to long-term endpoints. Overall GRADE evidence quality ranged from very low to moderate. Evidence certainty for 30-day permanent pacemaker implantation and revascularization during follow-up was rated as moderate, mainly due to a substantial effect size, with no major concerns about bias, inconsistency, or imprecision. For other outcomes, evidence certainty ranged from very low to low. Evidence for 30-day all-cause mortality, 30-day myocardial infarction, 30-day stroke, and 30-day major bleeding was downgraded due to imprecision, while evidence for 30-day acute kidney injury, 30-day major vascular complications, and myocardial infarction during follow-up was downgraded due to serious inconsistency. Additionally, myocardial infarction during follow-up was affected by publication bias (Supplementary Table S6).

4 Discussion

This meta-analysis included 13 studies with a total of 53,869 intermediate- and high-risk individuals with severe AS and concomitant CAD. The analysis systematically compared short- and mid- to long-term outcomes between TAVR + PCI and SAVR + CABG. In the short term, TAVR + PCI was associated with lower risks of stroke, myocardial infarction, and acute kidney injury, with no significant difference in all-cause mortality. However, the incidence of permanent pacemaker implantation was notably higher. Over mid- to long-term follow-up (≥2 years), TAVR + PCI was associated with increased risks of all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction, and repeat revascularization, whereas stroke risk remained comparable. Subgroup analyses confirmed the short-term advantages of TAVR + PCI across study designs and sample size stratifications. However, in studies with extended follow-up durations (≥5 years), TAVR + PCI showed a persistently higher risk of all-cause mortality and myocardial infarction during follow-up, raising concerns regarding mid- to long-term durability. The GRADE assessment indicated that evidence quality ranged from very low to moderate.

These short-term findings are consistent with the PARTNER 2 (38) and SURTAVI (2) trials, which demonstrated comparable short-term mortality between TAVR and SAVR, with reduced stroke incidence favoring TAVR. However, these trials did not specifically address concomitant CAD requiring revascularization. By incorporating evidence from RCTs and high-quality cohort studies, the present analysis further supports the short-term safety benefits of TAVR + PCI. Similar results were reported by Sakurai et al. (14), who identified no significant difference in 30-day mortality but lower acute kidney injury and higher pacemaker implantation rates with TAVR + PCI. Notably, that analysis lacked stratification by surgical risk, potentially contributing to heterogeneity. By focusing specifically on intermediate- and high-risk individuals, this meta-analysis additionally identified reduced risks of stroke and myocardial infarction with TAVR + PCI, findings not clearly emphasized in previous meta-analyses. Among the included studies, the TCW trial by Kedhi et al. (26) provided RCT-level evidence supporting favorable short-term outcomes with TAVR + PCI in elderly patients with anatomically suitable CAD, though limited by short follow-up and exclusion of patients with complex coronary anatomy. The short-term benefits of TAVR + PCI may be attributed to its minimally invasive nature, avoiding cardiopulmonary bypass and reducing procedural trauma, thereby lowering the risks of stroke, hypoperfusion-related injury, and acute kidney injury. PCI also facilitates timely revascularization, potentially reducing perioperative myocardial infarction. The increased rate of permanent pacemaker implantation following TAVR is likely related to atrioventricular node injury, particularly with self-expanding valves, as documented in prior studies.

Regarding mid- to long-term outcomes, the present findings align with the EXCEL (39) and SYNTAX (40) trials, which demonstrated superior mid- to long-term outcomes with CABG compared to PCI in patients with complex CAD. Although these trials did not include patients undergoing aortic valve intervention, the current analysis extends their conclusions to a high-risk AS population. The increased rates of myocardial infarction and repeat revascularization observed with TAVR + PCI may reflect incomplete revascularization or disease progression in untreated segments. In contrast, CABG provides durable distal perfusion via bypass grafts, which may contribute to mid- to long-term myocardial protection. Valve durability may also influence mid- to long-term outcomes. While early-generation TAVR valves showed structural deterioration within 5–8 years, surgical bioprosthetic valves typically last 10–15 years (41). However, more recent studies (e.g., PARTNER 2/3 and FRANCE-TAVI studies) (38, 42, 43) suggest that newer transcatheter valves exhibit improved durability, though further validation through mid- to long-term follow-up is necessary. Paravalvular leak following TAVR may lead to chronic volume overload, potentially affecting ventricular remodeling and mid- to long-term survival. Despite the worse mid- to long-term outcomes, stroke incidence during follow-up did not differ significantly between groups, possibly reflecting differences in antithrombotic strategies, baseline atrial fibrillation burden, and sample size.

Importantly, interpretation of these findings should be contextualized within the framework of the 2025 ESC/EACTS Guidelines (6) for the management of valvular heart disease, which emphasize individualized, Heart Team–based decision-making that integrates clinical risk, anatomical complexity, imaging findings, and patient preference, rather than relying solely on chronological age or surgical risk scores. In this context, the present results underscore that while TAVR + PCI may offer short-term procedural advantages, particularly in frail or high-risk patients, it may be associated with less favorable mid- to long-term outcomes in individuals with complex coronary anatomy or a longer life expectancy. Accordingly, patients with multivessel or anatomically complex CAD, in whom complete revascularization is more reliably achieved with CABG, may derive greater mid- to long-term benefit from SAVR + CABG, provided surgical risk is acceptable. Conversely, it is equally important to recognize clinical scenarios in which TAVR + PCI may not be recommended or technically feasible, including unfavorable annular or aortic root anatomy, inadequate vascular access, the need for concomitant surgical procedures (e.g., ascending aortic repair or other valve interventions), or specific valve morphologies such as certain bicuspid aortic valve phenotypes. These considerations reinforce that TAVR + PCI should not be viewed as a universal substitute for surgery but rather as one component of a tailored treatment strategy. At the same time, surgical treatment may be infeasible in selected patient subsets—such as those with porcelain aorta, prohibitive redo sternotomy risk, or advanced frailty—in whom TAVR + PCI may represent a feasible, and in some cases the only practical, option for combined valve intervention and coronary revascularization. The present findings therefore highlight the necessity of balancing early procedural safety against longer-term risks when selecting revascularization and valve strategies in this complex population.

This meta-analysis provides an updated and comprehensive synthesis comparing TAVR + PCI and SAVR + CABG in this intermediate- and high-risk patients with severe AS and concomitant CAD. Methodological rigor—including adherence to PRISMA guidelines, GRADE assessment, and pre-specified subgroup and sensitivity analyses—strengthens the robustness of the findings. Nonetheless, several limitations warrant discussion. First, substantial heterogeneity was observed across included studies in terms of patient characteristics, procedural details (e.g., valve type, access route), and operator experience, which may have influenced effect estimates. Second, PCI timing relative to TAVR varied widely, ranging from staged to simultaneous procedures, and was inconsistently reported, limiting the feasibility of stratified analyses by timing. Third, detailed coronary anatomical data (e.g., SYNTAX score, left main disease) were inconsistently reported, constraining lesion-complexity–based comparisons. Fourth, although HRs were prespecified as the preferred effect measure for mid- to long-term outcomes, most included studies only reported crude event counts and did not provide HRs or extractable Kaplan–Meier curves. Consequently, ORs derived from event numbers were used as an alternative, which may not fully capture the temporal dimension of outcomes and could have influenced the precision of mid- to long-term risk estimates. Fifth, outcome definitions were not fully standardized across studies (e.g., some applied VARC-2 or VARC-3 criteria, while others did not specify criteria). Although we systematically summarized all reported definitions in Supplementary Tables S3 and S4, such inconsistency may have contributed to residual heterogeneity, particularly for revascularization, where most studies did not distinguish target-lesion vs. any-vessel events, planned vs. unplanned staged procedures, or graft-failure–related reinterventions. Sixth, while procedural and anatomical effect modifiers (e.g., access route, valve type, PCI timing, completeness of revascularization, and SYNTAX strata) were considered a priori, their implementation was limited by non-uniform reporting and lack of harmonized definitions across studies; as a result, only consistently available subgroup variables—follow-up duration (<5 vs. ≥5 years) and study size (<300 vs. ≥300)—could be analyzed uniformly, with study design explored where feasible. Seventh, although two RCTs were included, the evidence base was predominantly derived from observational studies and therefore remains vulnerable to selection bias and residual confounding, even when adjustment techniques—such as propensity score matching or multivariable regression—were applied at the individual study level in some cohorts. Lastly, the overall certainty of evidence ranged from low to very low, primarily due to inconsistency and imprecision, underscoring the need for additional high-quality data. In the context of the 2025 ESC/EACTS Guidelines, these limitations highlight the need for cautious interpretation when extrapolating comparative effectiveness to individual clinical decision-making. Future research should therefore prioritize well-powered randomized trials with extended follow-up, standardized time-to-event outcome reporting, and stratification by coronary anatomy and clinical risk. Equally important, harmonized reporting of procedural and anatomical variables—including access route, valve type, PCI timing with explicit staged vs. concomitant definitions, completeness of revascularization, and quantitative SYNTAX categories—as well as consistent adoption of standardized outcome definitions (e.g., VARC-3), will be essential to enhance comparability across studies. Meta-analyses incorporating patient-level data and guideline-aligned outcome frameworks may further improve evidence quality and clinical applicability.

5 Conclusion

TAVR + PCI is associated with lower early periprocedural complications but may carry higher mid- to long-term risks compared with SAVR + CABG, although the certainty of evidence is limited by observational data and heterogeneity. Treatment decisions should be individualized, considering CAD complexity, revascularization completeness, valve type, and procedural timing. These findings underscore the importance of balancing early procedural safety against potential mid- to long-term risks when selecting treatment strategies in patients with severe AS and concomitant CAD. Further randomized trials with standardized outcome definitions and extended follow-up are warranted.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author contributions

XF: Data curation, Validation, Resources, Visualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – original draft. XZ: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Methodology, Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. FW: Validation, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources. SF: Visualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Resources. XC: Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Visualization, Project administration, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcvm.2026.1640906/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Coffey S Roberts-Thomson R Brown A Carapetis J Chen M Enriquez-Sarano M et al Global epidemiology of valvular heart disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. (2021) 18(12):853–64. 10.1038/s41569-021-00570-z

2.

Van Mieghem NM Deeb GM Søndergaard L Grube E Windecker S Gada H et al Self-expanding transcatheter vs surgical aortic valve replacement in intermediate-risk patients: 5-year outcomes of the SURTAVI randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol. (2022) 7(10):1000–8. 10.1001/jamacardio.2022.2695

3.

Faroux L Guimaraes L Wintzer-Wehekind J Junquera L Ferreira-Neto AN Del Val D et al Coronary artery disease and transcatheter aortic valve replacement: jACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2019) 74(3):362–72. 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.06.012

4.

Millan-Iturbe O Sawaya FJ Lønborg J Chow DHF Bieliauskas G Engstrøm T et al Coronary artery disease, revascularization, and clinical outcomes in transcatheter aortic valve replacement: real-world results from the east Denmark heart registry. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. (2018) 92(4):818–26. 10.1002/ccd.27440

5.

Otto CM Nishimura RA Bonow RO Carabello BA Erwin JP 3rd Gentile F et al 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. (2021) 162(2):e183–353. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2021.04.002

6.

Praz F Borger MA Lanz J Marin-Cuartas M Abreu A Adamo M et al 2025 ESC/EACTS guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J. (2025) 46(44):4635–736. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaf194

7.

Faroux L Campelo-Parada F Munoz-Garcia E Nombela-Franco L Fischer Q Donaint P et al Procedural characteristics and late outcomes of percutaneous coronary intervention in the workup Pre-TAVR. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. (2020) 13(22):2601–13. 10.1016/j.jcin.2020.07.009

8.

Collet JP Thiele H Barbato E Barthélémy O Bauersachs J Bhatt DL et al 2020 ESC guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. (2021) 42(14):1289–367. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa575

9.

Sengupta PP Kluin J Lee SP Oh JK Smits A . The future of valvular heart disease assessment and therapy. Lancet. (2024) 403(10436):1590–602. 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)02754-X

10.

Patlolla SH Schaff HV Dearani JA Stulak JM Crestanello JA Greason KL . Aortic stenosis and coronary artery disease: cost of transcatheter vs surgical management. Ann Thorac Surg. (2022) 114(3):659–66. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2021.08.028

11.

Abugroun A Osman M Awadalla S Klein LW . Outcomes of transcatheter aortic valve replacement with percutaneous coronary intervention versus surgical aortic valve replacement with coronary artery bypass grafting. Am J Cardiol. (2020) 137:83–8. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2020.09.040

12.

Penkalla A Pasic M Drews T Buz S Dreysse S Kukucka M et al Transcatheter aortic valve implantation combined with elective coronary artery stenting: a simultaneous approach†. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. (2015) 47(6):1083–9. 10.1093/ejcts/ezu339

13.

Patterson T Clayton T Dodd M Khawaja Z Morice MC Wilson K et al ACTIVATION (Percutaneous coronary inTervention prIor to transcatheter aortic VAlve implantaTION): a randomized clinical trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. (2021) 14(18):1965–74. 10.1016/j.jcin.2021.06.041

14.

Sakurai Y Yokoyama Y Fukuhara S Takagi H Kuno T . Complete transcatheter versus surgical approach stenosis with coronary artery disease: a systematic and meta-analysis. Jo Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. (2024) 167(4):1305–1313.e9. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2022.08.006

15.

Guo Y Zhang W Wu H . Percutaneous versus surgical approach to aortic valve replacement with coronary revascularization: a systematic review andmeta-analysis. Perfusion. (2024) 39(6):1152–60. 10.1177/02676591231178894

16.

Tarus A Tinica G Bacusca A Artene B Popa IV Burlacu A . Coronary revascularization during treatment of severe aortic stenosis: a meta-analysis of the complete percutaneous approach (PCI plus TAVR) versus the complete surgical approach (CABG plus SAVR). J Card Surg. (2020) 35(8):2009–16. 10.1111/jocs.14814

17.

Kotronias RA Bray JH Scarsini R Rajasundaram S Terentes-Printzios D Maria D et al Transcatheter aortic valve replacement and percutaneous coronary intervention versus surgical aortic valve replacement and coronary artery bypass grafting in patients with severe aortic stenosis and concomitant coronary artery disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. (2020) 96(5):1113–25. 10.1002/ccd.29110

18.

Zhang J Jiang T Hou Y Chen F Yang K Sang W et al Five-year outcomes comparing percutaneous coronary intervention with drug-eluting stents versus coronary artery bypass grafting in patients with left main coronary artery disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Atherosclerosis. (2020) 308:50–6. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2020.06.024

19.

Bacha Z Javed J Khattak F Qadri M Shoaib M Shah IM et al Transcatheter versus surgical approach for the treatment of aortic stenosis in patients with concomitant coronary artery disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. (2025) 106(3):1661–73. 10.1002/ccd.31697

20.

Emara A Emara M Gadelmawla AF Murad MR Aboeldahab H Elgendy MS et al Transcatheter versus surgical treatment in aortic stenosis with coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis of time-to-event data on 162,305 patients. Heart Lung. (2026) 75:184–97. 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2025.09.018

21.

Page MJ McKenzie JE Bossuyt PM Boutron I Hoffmann TC Mulrow CD et al The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int J Surg. (2021) 88:105906. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105906

22.

Sterne JAC Savović J Page MJ Elbers RG Blencowe NS Boutron I et al Rob 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. Br Med J. (2019) 366:l4898. 10.1136/bmj.l4898

23.

Wells G Shea B O'Connell D Peterson J Welch V Losos M et al The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analyses. (2011). Available online at:https://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp(Accessed January 8, 2026).

24.

Guyatt G Oxman AD Akl EA Kunz R Vist G Brozek J et al GRADE Guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol. (2011) 64(4):383–94. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.026

25.

Taghiyev ZT Jaeger KE Fuchs MV Roth P Doerr O Boening A . Renal function after combined treatment for coronary disease and aortic valve replacement. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. (2025) 3(8):639–48. 10.1055/a-2493-1495

26.

Kedhi E Hermanides RS Dambrink JE Singh SK Ten Berg JM van Ginkel D et al Transcatheter aortic valve implantation and fractional flow reserve-guided percutaneous coronary intervention versus conventional surgical aortic valve replacement and coronary bypass grafting for treatment of patients with aortic valve stenosis and complex or multivessel coronary disease (TCW): an international, multicentre, prospective, open-label, non-inferiority, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. (2025) 404(10471):2593–602. 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)02100-7

27.

Jagadeesan V Mehaffey JH Kawsara MA Chauhan D Hayanga JWA Mascio CE et al Transcatheter vs surgical aortic valve replacement in medicare beneficiaries with aortic stenosis and coronary artery disease. Ann Thorac Surg. (2025) 119(4):843–51. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2024.12.016

28.

Amat-Santos IJ Garcia-Gomez M Avanzas P Jimenez-Diaz V Alonso-Briales JH Hernandez J et al Surgical vs transcatheter treatment in patients with coronary artery disease and severe aortic stenosis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. (2024) 17(21):2472–85. 10.1016/j.jcin.2024.09.003

29.

Ullah W Sarvepalli D Kumar A Zahid S Saleem S Muhammadzai HZU et al Trends and outcomes of combined percutaneous (TAVI plus PCI) and surgical approach (SAVR plus CABG) for patients with aortic valve and coronary artery disease: a national readmission database (NRD) analysis. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. (2023) 102(5):946–57. 10.1002/ccd.30832

30.

McInerney A Marquez MG Tirado-Conte G Bernal J Fernandez-Perez C Jimenez-Quevedo P et al In-hospital outcomes following percutaneous versus surgical intervention in the treatment of aortic stenosis and concomitant coronary artery disease. Rev Esp Cardiol. (2023) 76(8):600–8. 10.1016/j.recesp.2022.12.011

31.

Lérault A Villecourt A Decottignies-Dienne T Tassan-Mangina S Heroguelle V Di Cesare A et al Catheter versus surgical approach for the management of concomitant aortic stenosis and coronary artery disease: an inverse probability treatment weighting analysis. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. (2023) 116(3):117–25. 10.1016/j.acvd.2022.12.004

32.

Elderia A Gerfer S Eghbalzadeh K Adam M Baldus S Rahmanian P et al Surgical versus interventional treatment of concomitant aortic valve stenosis and coronary artery disease. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. (2023) 71(08):620–31. 10.1055/a-2003-2105

33.

Alperi A Mohammadi S Campelo-Parada F Munoz-Garcia E Nombela-Franco L Faroux L et al Transcatheter versus surgical aortic valve replacement in patients with complex coronary artery disease. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. (2021) 14(22):2490–9. 10.1016/j.jcin.2021.08.073

34.

Søndergaard L Popma JJ Reardon MJ Van Mieghem NM Deeb GM Kodali S et al Comparison of a complete percutaneous versus surgical approach to aortic valve replacement and revascularization in patients at intermediate surgical risk results from the randomized SURTAVI trial. Circulation. (2019) 140(16):1296–305. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.039564

35.

Baumbach H Schairer ER Wachter K Rustenbach C Ahad S Stan A et al Transcatheter aortic valve replacement- management of patients with significant coronary artery disease undergoing aortic valve interventions: surgical compared to catheter-based approaches in hybrid procedures. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. (2019) 19(1):108. 10.1186/s12872-019-1087-2

36.

Barbanti M Buccheri S Capodanno D D'Errigo P Ranucci M Rosato S et al Transcatheter or surgical treatment of severe aortic stenosis and coronary artery disease: a comparative analysis from the Italian OBSERVANT study. Int J Cardiol. (2018) 270:102–6. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.06.011

37.

Wendt D Kahlert P Lenze T Neuhäuser M Price V Konorza T et al Management of high-risk patients with aortic stenosis and coronary artery disease. Ann Thorac Surg. (2013) 95(2):599–605. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.07.075

38.

Leon MB Smith CR Mack MJ Makkar RR Svensson LG Kodali SK et al Transcatheter or surgical aortic-valve replacement in intermediate-risk patients. N Engl J Med. (2016) 374(17):1609–20. 10.1056/NEJMoa1514616

39.

Stone GW Sabik JF Serruys PW Simonton CA Généreux P Puskas J et al Everolimus-eluting stents or bypass surgery for left main coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. (2016) 375(23):2223–35. 10.1056/NEJMoa1610227

40.

Serruys PW Morice MC Kappetein AP Colombo A Holmes DR Mack MJ et al Percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary-artery bypass grafting for severe coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. (2009) 360(10):961–72. 10.1056/NEJMoa0804626

41.

Kostyunin AE Yuzhalin AE Rezvova MA Ovcharenko EA Glushkova TV Kutikhin AG . Degeneration of bioprosthetic heart valves: update 2020. J Am Heart Assoc. (2020) 9(19):e018506. 10.1161/JAHA.120.018506

42.

Mack MJ Leon MB Thourani VH Makkar R Kodali SK Russo M et al Transcatheter aortic-valve replacement with a balloon-expandable valve in low-risk patients. N Engl J Med. (2019) 380(18):1695–705. 10.1056/NEJMoa1814052

43.

Auffret V Lefevre T Van Belle E Eltchaninoff H Iung B Koning R et al Temporal trends in transcatheter aortic valve replacement in France: FRANCE 2 to FRANCE TAVI. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2017) 70(1):42–55. 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.04.053

Summary

Keywords

aortic stenosis, coronary artery bypass grafting, coronary artery disease, meta-analysis, percutaneous coronary intervention, surgical aortic valve replacement, transcatheter aortic valve replacement

Citation

Fang X, Zhang X, Wei F, Feng S and Chen X (2026) Comparing TAVR + PCI vs. SAVR + CABG across short- and mid- to long-term horizons in patients with severe aortic stenosis and concomitant CAD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 13:1640906. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2026.1640906

Received

04 June 2025

Revised

11 January 2026

Accepted

12 January 2026

Published

30 January 2026

Volume

13 - 2026

Edited by

Omer Dzemali, University Hospital Zürich, Switzerland

Reviewed by

Zoltan Ruzsa, University of Szeged, Hungary

Luca Koechlin, University Hospital Zürich, Switzerland

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Fang, Zhang, Wei, Feng and Chen.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Xiaomei Chen xmxmchenxiaomei@163.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.