Abstract

Objective:

This systematic review, including a meta-analysis, aimed to investigate the efficacy and safety of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) in preventing and resolving radial artery occlusion (RAO) following transradial artery access.

Methods:

We synthesized evidence from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) identified in PubMed, CENTRAL, Scopus, and Web of Science up to May 2025. Using Stata MP v. 17, we employed a fixed-effects model to report dichotomous outcomes, presenting relative risk ratio (RR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI). Trial sequential analysis (TSA) was conducted to investigate the robustness and reliability of the cumulative evidence.

Results:

Four RCTs with 970 participants were included. DOACs significantly decreased the incidence of RAO [RR: 0.49, 95% (0.31, 0.79), p < 0.001]. However, in terms of RAO resolution, there were no differences between groups [RR: 1.22, 95% CI (0.80, 1.88), p = 0.36]. Moreover, there were no differences between groups regarding the incidence of hematoma [RR: 0.56, 95% (0.12, 2.61), p = 0.46], minor bleeding [RR: 1.55, 95% (0.72, 3.32), p = 0.26], and major bleeding [RR: 2.41, 95% (0.48, 12.25), p = 0.36]. There were no incidences of arteriovenous fistula, pseudoaneurysm, or compartment syndrome throughout the trials.

Conclusion:

DOACs significantly prevented the incidence of RAO, although TSA indicates that this finding is not yet conclusive. No significant differences were found between groups regarding RAO resolution or the incidence of hematoma, minor bleeding, or major bleeding.

Systematic Review Registration:

https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/, identifier CRD420251063999.

1 Introduction

Transradial artery access (TRA) has become the preferred method for most coronary catheterization procedures, exhibiting a reduced incidence of access-related complications compared to the transfemoral approach (1, 2). TRA offers several advantages, including rapid hemostasis, prompt patient mobilization, and a decreased incidence of all-cause mortality, major bleeding, and vascular complications (3). Therefore, the European Society of Cardiology and the American Heart Association recommend TRA as the standard approach, instead of transfemoral access, for all patients undergoing invasive coronary interventions when performed by skilled operators (4, 5). However, in 30%–40% of cases, patients are released without confirmation of radial artery patency. In addition, Doppler examination or plethysmography is used in fewer than 10% of patients, where radial artery patency is assessed (6–8).

Therefore, radial artery occlusion (RAO) has been the most concerning complication following TRA. The rate of RAO in patients who have undergone TRA has varied from less than 1%–33% (1, 9). While often asymptomatic, the potential occurrence of RAO may contraindicate subsequent ipsilateral TRA procedures, thus restricting future radial artery utilization for coronary artery bypass grafting or hemodialysis access (10). The primary pathogenesis of RAO after a TRA procedure is thrombus formation, resulting from the combined effects of endothelial and vascular injury, local hypercoagulability, and decreased blood flow (3, 11, 12). Hence, the significance of sufficient procedural anticoagulation in mitigating early RAO incidence is recognized, yet consensus on the optimal anticoagulation regimen remains lacking (3, 13).

Despite the adoption of best practices such as patent hemostasis, RAO persists in a significant proportion of patients, necessitating the exploration of pharmacological adjuncts (1). Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) have emerged as effective and safe oral anticoagulants (OACs) in multiple settings (14–16), and several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have recently investigated DOACs to prevent and resolve RAO following TRA with promising results (17–20). Therefore, the primary aim of this systematic review, including a meta-analysis, was to evaluate whether the addition of DOACs to standard care is effective and safe for preventing or resolving RAO.

2 Methods

2.1 Protocol registration

This systematic review was prospectively registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (CRD420251063999). The systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (21) and the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (22).

2.2 Data sources & search strategy

On 17 May 2025, an electronic search was conducted by AbA across the following databases: Web of Science (WOS), PubMed, EMBASE, Scopus, and CENTRAL. The search strategy included the following entry terms: “(anticoagulat* OR “direct oral anticoagulant*” OR DOAC* OR NOAC* OR apixaban OR rivaroxaban OR edoxaban OR dabigatran) AND (“radial artery” OR “radial artery occlusion” OR “radial artery spasm” OR transradial).” Our search strategy employed unrestricted access to most databases; however, Scopus searches were limited to titles and abstracts. Supplementary Table S1 provides a detailed account of the specific search terms and results for each database. A comprehensive review of the reference lists from the included trials was conducted to minimize the risk of excluding relevant studies.

2.3 Eligibility criteria

RCTs were included if they met the following PICO criteria: population (P), patients who underwent transradial cardiovascular interventions; intervention (I), DOACs, including rivaroxaban, apixaban, edoxaban, or dabigatran, regardless of the dosing protocol for either prevention of RAO incidence or treatment of established RAO; control (C), no treatment or another anticoagulant; and outcomes (O): primary outcome was the incidence of RAO up to 30 days following procedure and secondary outcomes included established RAO resolution and adverse events (hematoma, minor bleeding, major bleeding, arteriovenous fistula, compartment syndrome, and pseudoaneurysm). Furthermore, our analysis excluded quasi-randomized trials, conference presentations/proceedings, observational studies, in vitro research, and review articles.

2.4 Study selection

Covidence was used by two independent reviewers (AlA and OA) for thorough screening. After eliminating duplicates, a two-stage evaluation process was employed: initial title and abstract screening, followed by a full-text review of the remaining records. Disagreements were settled through discussion and consensus.

2.5 Data extraction

A pilot extraction of relevant publications was conducted to develop an Excel extraction form after obtaining the full texts of eligible publications. The form was structured into three sections: (1) summary characteristics of the included trials (study ID, country, study design, sample size, treatment protocols, main inclusion criteria, and follow-up duration); (2) baseline characteristics of the included participants (age, gender, and comorbidities); and (3) outcomes [the incidence of RAO up to 30 days following the procedure, established RAO resolution, and the adverse events (hematoma, minor bleeding, major bleeding, arteriovenous fistula, compartment syndrome, and pseudoaneurysm)]. Two reviewers independently extracted the data (AlA and OA), resolving disagreements through discussion with a senior author. Dichotomous data were documented as event rates, whereas continuous data were summarized using means and standard deviations.

2.6 Risk of bias and certainty of evidence

The revised Cochrane Collaboration tool for RCTs (ROB 2) was employed to evaluate the risk of bias in the included studies (23). Two reviewers (M.S.A and Y.H.A.) independently assessed each study, examining domains such as selection bias, performance bias, reporting bias, attrition bias, and other potential sources of bias. Disagreements were resolved through a consensus-building process. In addition, the certainty of the evidence was evaluated using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) framework (24, 25). This assessment considered factors such as inconsistency, imprecision, indirectness, publication bias, and risk of bias. Each factor was individually analyzed, with decisions clearly justified and documented. Any discrepancies in the evaluation were addressed through discussion to reach a mutually agreed-upon resolution.

2.7 Statistical analysis

Data analysis was conducted using Stata MP, version 17 (StataCorp). Dichotomous outcomes were analyzed using the risk ratio (RR), with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The fixed-effect model was the primary approach; however, a random-effects model was adopted in the presence of significant heterogeneity. Heterogeneity among the included studies was assessed using the chi-squared test and the I-squared statistic (I2), with a p-value of <0.1 for the chi-square test and an I2 value of 50% or higher indicating significant heterogeneity. To account for the observed clinical heterogeneity and investigate the stability of the pooled results, we conducted leave-one-out sensitivity analysis. Publication bias was not assessed, as all evaluated outcomes included fewer than 10 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) (26). Finally, trial sequential analysis (TSA) was conducted to assess the robustness and conclusiveness of the meta-analytic results. TSA considered the size of the information and the cumulative z-curve to determine the sufficiency and robustness of the available evidence. Boundary controls were established to manage the risks associated with Type I and Type II errors. TSA was conducted using the trial sequential analysis software (27).

3 Results

3.1 Search results and study selection

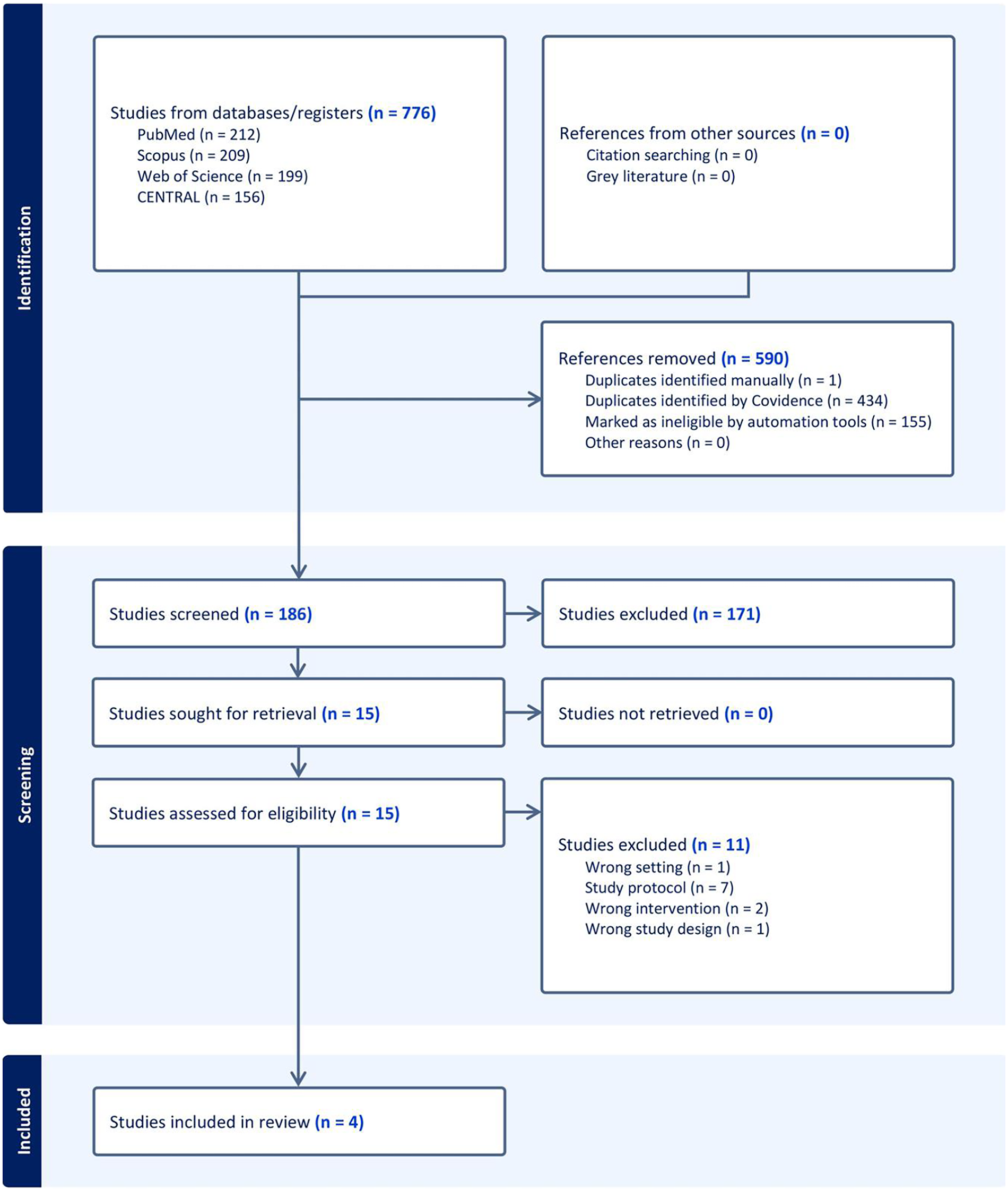

Following a literature search, 776 studies were identified. Covidence automatically removed 590 irrelevant records, leaving 186 records to be screened. Following title and abstract screening, 171 studies were excluded for failing to meet the inclusion criteria, leaving 15 full-text articles for further assessment. Of these, 11 studies were excluded (Supplementary Table S2), leaving four RCTs (17–20) to be included in qualitative and quantitative analyses (Figure 1).

Figure 1

PRISMA flow chart of the screening process.

3.2 Characteristics of included studies

Four trials with a total of 970 participants were included (17–20). Two trials investigated DOACs for RAO prophylaxis (17, 19) and another two used DOACs to treat established RAO (18, 20). Three trials used rivaroxaban (17–19), and one used apixaban (20). No eligible RCTs evaluating dabigatran or edoxaban were identified during the search process. The control group consisted of watchful waiting with no treatment in three trials (17–19), and one trial used enoxaparin as a control (20). Further details on the treatment protocols, study design, and patient information are provided in Tables 1, 2.

Table 1

| Study ID | Study design | Country | Total participants | DOACs | Control | Treatment/prophylaxis | RAO diagnostic method | Timing of RAO assessment | Definition of RAO | Primary outcome | Follow-up duration | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug | Dosing protocol | |||||||||||

| Amirpour et al. (20) | RCT | Iran | 30 | Apixaban | 2.5 mg/twice daily | No treatment | Treatment | Doppler ultrasonography | Baseline: symptomatic onset postprocedure; Follow-up: 30 days postprocedure | Absence of forward blood flow detected in triphasic waves | Radial artery recanalization | 30 days |

| Hammami et al. (RIVARAD) (17) | RCT | Tunisia | 521 | Rivaroxaban | 10 mg for 7 days after the procedure | No treatment | Prevention | Doppler ultrasonography | Follow-up: 30 days postprocedure | No antegrade flow signal | Rate of radial artery occlusion at 30 days | 30 days |

| Liang et al. (RESTORE) (19) | RCT | China | 382 | Rivaroxaban | 10 mg for 7 days after the procedure | Placebo | Prevention | Doppler ultrasonography | Screening: 24 h postprocedure; Follow-up: 30 days postprocedure | No antegrade flow signal | Rate of radial artery occlusion at 24 h | 30 days |

| Maadani et al. (18) | RCT | Iran | 37 | Rivaroxaban | 15 mg twice daily for 21 days, followed by 20 mg daily for 7 days | Enoxaparin (1 mg/kg twice daily) for 28 days | Treatment | Doppler ultrasonography | Screening: Within 24 h postprocedure; Follow-up: 28 days postrandomization | Complete absence of blood flow (total thrombotic occlusion) | Radial artery recanalization | 28 days |

Summary characteristics of the included RCTs.

RAO, radial artery occlusion; RCT, randomized controlled trial; DOACs, direct oral anticoagulants.

Table 2

| Study ID | Number of patients | Age (years), mean (SD) | Gender (male), N (%) | Comorbidities | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DOACs | Control | DOACs | Control | DOACs | Control | HTN | DM | Smoking | Stoke | |||||

| DOACs | Control | DOACs | Control | DOACs | Control | DOACs | Control | |||||||

| Amirpour et al. (20) | 15 | 15 | 59.14 (12.85) | 59.73 (11.43) | 12 (80) | 6 (40) | 8 (53.3) | 4 (26.7) | 6 (40) | 4 (26.7) | 6 (40) | 1 (6.7) | NA | NA |

| Hammami et al. (RIVARAD) (17) | 259 | 262 | 59.41 ± 10 | 60.1 ± 9 | 185 (71.4) | 167 (63.7) | 137 (52.9) | 147 (56.1) | 114 (44) | 137 (52.3) | 135 (52.1) | 115 (43.9) | NA | NA |

| Liang et al. (RESTORE) (19) | 191 | 191 | 64.3 ± 10.1 | 64.0 ± 10.0 | 117 (61.3) | 126 (66.0) | 131 (68.6) | 126 (66.0) | 60 (31.4) | 58 (30.4) | 65 (34.0) | 69 (36.1) | 8 (4.2) | 7 (3.7) |

| Maadani et al. (18) | 20 | 17 | 54.5 ± 15.2 | 56.0 ± 8.5 | 3 (15) | 8 (47.1) | 11 (55.0) | 11 (64.7) | 6 (30.0) | 5 (29.4) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

Baseline characteristics of the participants.

DOACs, direct oral anticoagulants; SD, standard deviation; N, number of patients; HTN, hypertension; DM, diabetes mellitus.

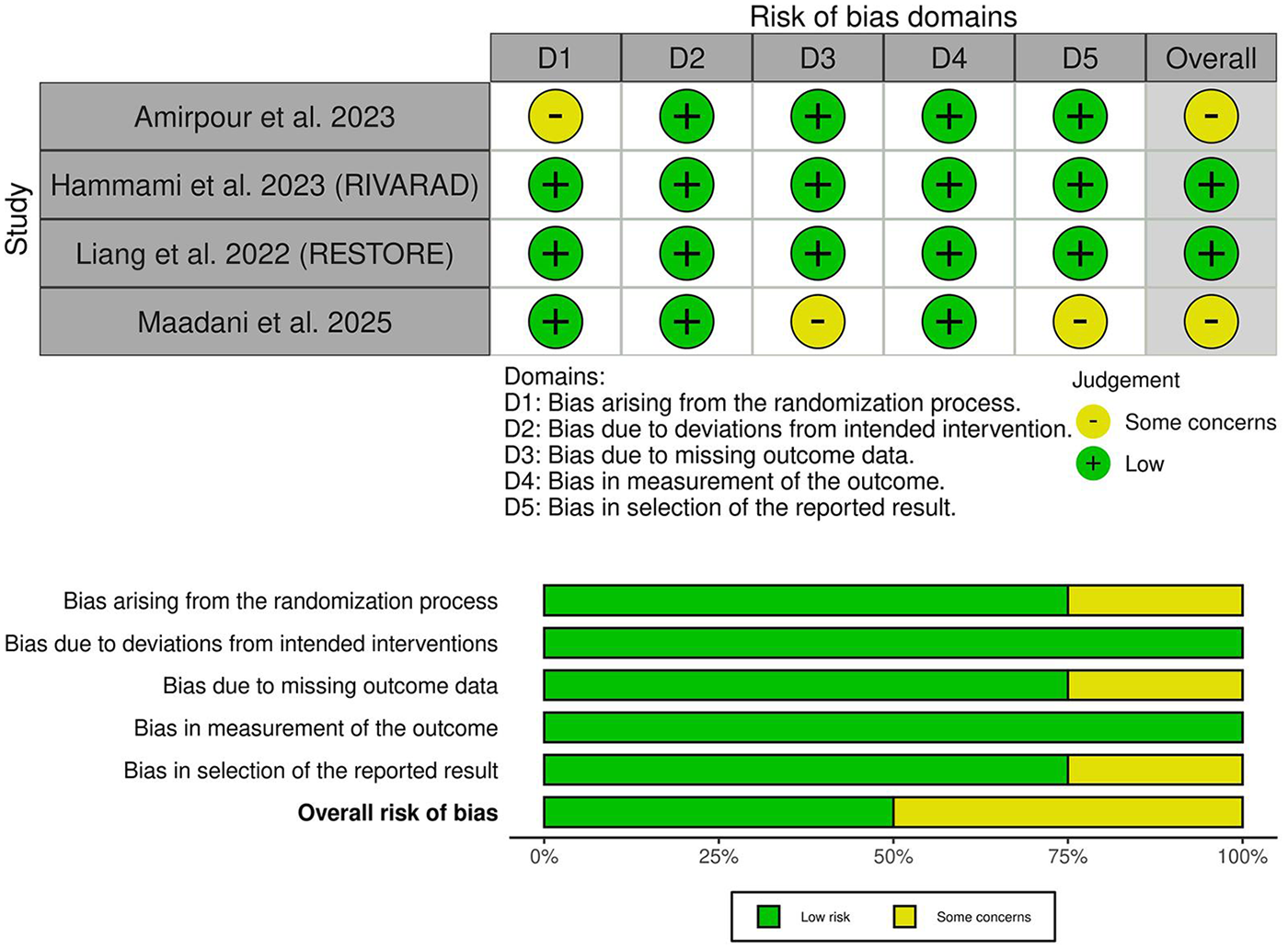

3.3 Risk of bias and certainty of evidence

Two trials demonstrated an overall low risk of bias (17, 19), while two trials showed some concerns of bias (18, 20) (Figure 2). Amirpour et al. showed some concerns regarding selection bias due to a lack of information about the randomization process (20). In contrast, Maadani et al. raised concerns about attrition bias due to the 15% drop in patients in the control group without clear justification (18). The GRADE certainty of evidence is summarized in Table 3.

Figure 2

Quality assessment of risk of bias in the included trials. The upper panel presents a schematic representation of risks (low = green, some concerns = yellow, high = red) for specific types of biases in the studies reviewed. The lower panel presents risks (low = green, some concerns = yellow, high = red) for the subtypes of biases of the combination of studies included in this review.

Table 3

| Certainty assessment | Summary of findings | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants (studies) follow-up |

Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication bias | Overall certainty of evidence | Study event rates (%) | Relative effect (95% CI) |

Anticipated absolute effects | ||

| With (Control) | With (DOACs) | Risk with (Control) | Risk difference with (DOACs) | ||||||||

| Radial artery occlusion | |||||||||||

| 835 (2 RCTs) |

Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Very serious | None | ⊕⊕◯◯ Lowa |

52/419 (12.4%) | 24/416 (5.8%) |

RR 0.49

(0.31 to 0.79) |

52/419 (12.4%) | 63 fewer per 1,000 (from 86 fewer to 26 fewer) |

| Radial artery occlusion resolution | |||||||||||

| 100 (3 RCTs) |

Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Extremely seriousa | None | ⊕◯◯◯ Very lowa |

24/52 (46.2%) | 31/48 (64.6%) |

RR 1.22

(0.80 to 1.88) |

24/52 (46.2%) | 102 more per 1,000 (from 92 fewer to 406 more) |

| Hematoma | |||||||||||

| 835 (2 RCTs) |

Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Extremely seriousa | None | ⊕◯◯◯ Very lowa |

4/419 (1.0%) | 2/416 (0.5%) |

RR 0.56

(0.12 to 2.61) |

4/419 (1.0%) | 4 fewer per 1,000 (from 8 fewer to 15 more) |

| Minor bleeding | |||||||||||

| 940 (3 RCTs) |

Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Very seriousa | None | ⊕⊕◯◯ Lowa |

10/470 (2.1%) | 16/470 (3.4%) |

RR 1.55

(0.72 to 3.32) |

10/470 (2.1%) | 12 more per 1,000 (from 6 fewer to 49 more) |

| Major bleeding | |||||||||||

| 940 (3 RCTs) |

Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Extremely seriousa | None | ⊕◯◯◯ Very lowa |

1/470 (0.2%) | 4/470 (0.9%) |

RR 2.41

(0.48 to 12.25) |

1/470 (0.2%) | 3 more per 1,000 (from 1 fewer to 24 more) |

GRADE evidence profile.

CI, confidence interval; RR, risk ratio; explanations.

Bold values indicate statistically significant results.

A wide confidence interval with a low number of events.

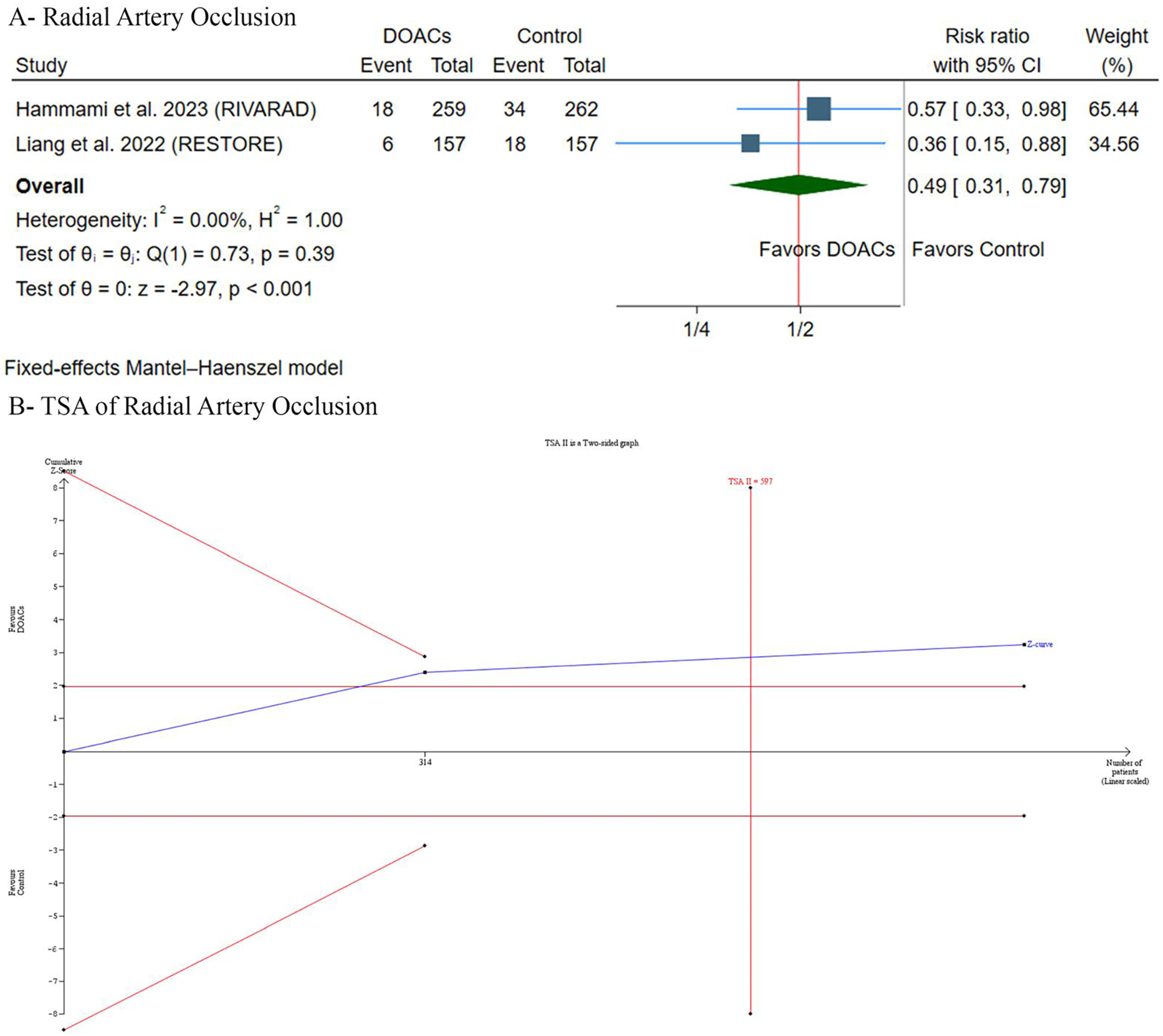

3.4 Primary outcome: radial artery occlusion incidence

DOACs significantly decreased the incidence of RAO [RR: 0.49, 95% (0.31, 0.79), p < 0.001] (Figure 3A). Pooled studies were homogeneous (p = 0.39, I2 = 0%). TSA suggested a trend favoring DOACs, as the Z-curve crossed the conventional statistical significance boundary. However, it did not cross the more conservative TSA-adjusted boundary, and the required information size of participants had not yet been reached (Figure 3B). Therefore, while current evidence suggests a benefit with DOACs, the findings are not yet conclusive according to the TSA, and further research may be needed to strengthen the findings and mitigate the risk of random errors in this cumulative analysis.

Figure 3

(A) Forest plot of radial artery occlusion incidence comparing. DOACs versus control. (B) Trial sequential analysis of radial artery occlusion incidence. RR, risk ratio; CI, confidence interval.

3.5 Secondary outcomes

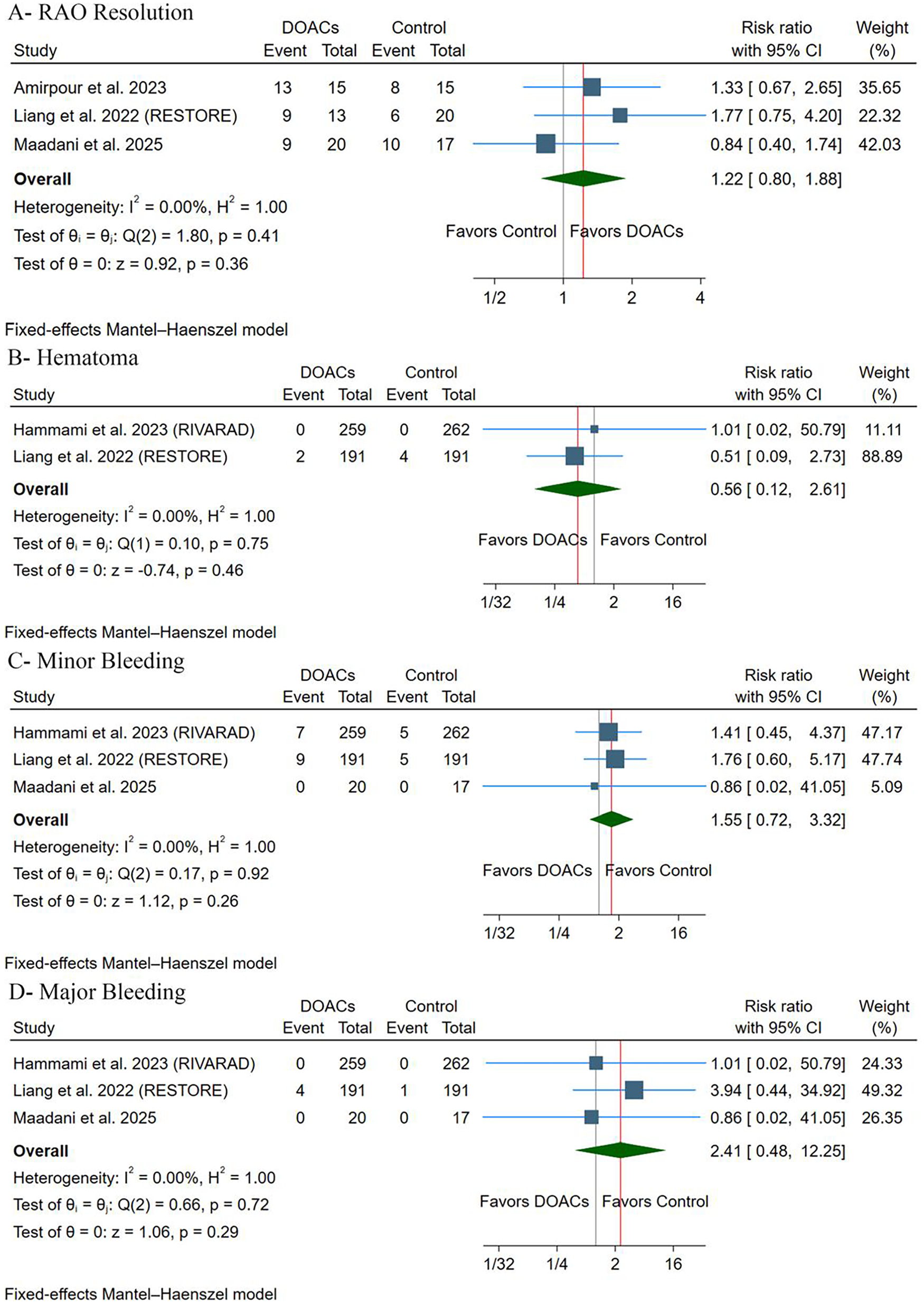

3.5.1 RAO resolution

There were no differences observed between groups [RR: 1.22, 95% (0.80, 1.88), p = 0.36] (Figure 4A). Pooled studies were homogeneous (p = 0.41, I2 = 0%). Leave-one-out sensitivity analysis revealed that the results were stable, with no significant statistical difference observed across exclusion scenarios (Supplementary Figure S1).

Figure 4

(A) Radial artery occlusion resolution. (B) Hematoma. (C) Minor bleeding. (D) Major bleeding. RR, risk ratio; CI, confidence interval.

3.5.2 Adverse events

There were no differences between groups regarding the incidence of hematoma [RR: 0.56, 95% (0.12, 2.61), p = 0.46] (Figure 4B), minor bleeding [RR: 1.55, 95% (0.72, 3.32), p = 0.26] (Figure 4C), or major bleeding [RR: 2.41, 95% (0.48, 12.25), p = 0.36] (Figure 4D). Pooled studies were homogeneous in terms of hematoma (p = 0.75, I2 = 0%), minor bleeding (p = 0.92, I2 = 0%), and major bleeding (p = 0.72, I2 = 0%). There were no cases of arteriovenous fistula, pseudoaneurysm, or compartment syndrome throughout the included trials. Leave-one-out sensitivity analysis revealed that the results were stable, with no significant statistical difference observed in all exclusion scenarios for minor bleeding (Supplementary Figure S2) and major bleeding (Supplementary Figure S3).

4 Discussion

After synthesizing evidence from four RCTs involving 970 patients, DOACs were effective in preventing the incidence of RAO after TRA procedures but not in resolving the already established RAO. In addition, DOACs were well tolerated, with no difference compared to the control groups regarding the incidence of hematoma and bleeding, and no reported cases of arteriovenous fistula, pseudoaneurysm, or compartment syndrome across the included trials.

A significant risk factor for RAO is thrombus formation after endothelial injury with reduced blood flow after sheath and catheter insertion (12). Repeated radial artery cannulation may lead to intimal hyperplasia and increased intima-media thickness, thereby contributing to adverse arterial wall remodeling and an increased risk of RAO (28). Stagnant blood during hemostasis can lead to thrombus formation, potentially causing vessel occlusion (1). Reducing compression time and sheath size minimizes the risk of RAO by lessening endothelial injury (29). Maintaining the radial artery's long-term function after transradial artery catheterization is crucial for optimal patient outcomes. Therefore, it is crucial to urgently investigate effective preventive and abortive measures of RAO.

The contradictory effect of DOACs—preventing but not resolving RAO—is worth further investigation. RAO can result from endothelial damage and reduced blood flow caused by sheath and catheter insertion, as well as procedural manipulations, which activate the coagulation cascade, leading to the formation of thrombi and causing radial artery thrombosis (30). Artery compression by local edema or hematoma is another contributing factor (31). Early administration of DOACs may prevent this cascade of events, explaining their preventative efficacy. However, DOACs may need a more prolonged period to resolve an established RAO. Liang et al. reported that the 24 h RAO rate was similar in the rivaroxaban and control groups, indicating that a single 10 mg postprocedural dose of rivaroxaban may be insufficient to prevent early RAO (19). This might be because the RAO occurred before the rivaroxaban took effect, since it was given after the bleeding had stopped. Therefore, the thrombus persisted due to the insufficient duration of rivaroxaban's effect, resulting in a lower radial artery recanalization rate (19).

Moreover, baseline differences in RAO risk factors may have contributed to this effect. Modifiable patient risk factors include diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, peripheral artery disease, multivessel cardiovascular disease, and kidney diseases (3). Unmodifiable patient risk factors include ethnicity (South Asian descent), female gender, low body mass index, older age, reduced radial artery diameter, and prior catheterizations at the same arterial access site (3). In addition, modifiable procedural factors include insufficient anticoagulation, extended procedure times, multiple catheter use, radial artery spasm, repeated arterial punctures, and prolonged or occlusive postoperative hemostasis (3). Larger sheaths and mismatches between sheath and artery size (indicated by a high sheath-to-artery ratio) can damage the vessel wall, increasing the risk of RAO (10, 29).

Hammami et al. found that smoking, the female sex, and a history of TRA punctures predicted the occurrence of RAO (17). Among smoking women in their cohort with a history of TRA puncture, RAO occurred in 50%. Contributing factors may include the smaller radial artery diameter in women compared to men, the known prothrombotic effects of tobacco use, and the possibility of repeated trauma to the artery. However, their multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that a week of postoperative rivaroxaban (10 mg daily) and the heparin given during the procedure independently predicted a lower incidence of 1-month RAO, with no adverse bleeding observed (17). On the other hand, none of the factors considered—age, sex, BMI, smoking, diabetes, hypertension, statin use, antiplatelet regimen (single or dual), intervention duration, and radial artery diameter—were associated with RAO resolution as reported by Amirpour et al. (20). Nevertheless, most research to date has focused on factors associated with the incidence of RAO, rather than its resolution.

Our pooled analysis has the following limitations: First, we included a limited number of RCTs with a small number of patients, given the context of the overall number of patients undergoing TRA; hence, our results require further confirmation. Second, the geographical representation of the included sample is limited to Asia, further limiting the generalizability of our findings. Third, due to limited data, we could not conduct a meta-regression analysis to investigate the potential effect of different confounders on our results. Fourth, GRADE assessment and TSA indicated that current evidence remains imprecise, warranting careful interpretation of our findings.

In terms of clinical implications, our results suggest that a short-term prophylactic course of DOACs could be a valuable adjunctive strategy in routine practice. Both the RIVARAD and RESTORE trials utilized a regimen of Rivaroxaban 10 mg daily for 7 days following the procedure, demonstrating a significant reduction in 30-day RAO without an increase in major bleeding events (17, 19). This strategy could be especially beneficial for patients at high risk, who are likely to experience occlusion, despite following best practices. For example, Hammami et al. identified female sex, smoking, and previous transradial puncture as independent predictors of RAO (17). Therefore, in cases with difficult patent hemostasis, or for high-risk groups such as those with small radial arteries or smokers, clinicians may consider a short period of low-dose DOACs following discharge to decrease the risk of vessel loss.

Further large-scale RCTs are warranted to investigate the following: First, the optimal DOAC regimen remains unclear. Additional research is necessary to determine the safety and efficacy of a brief, high-dose DOAC regimen. The comparative safety and efficacy of DOACs versus other anticoagulants, such as low-molecular-weight heparin, remain unclear. Second, future trials should investigate the efficacy of DOACs in conjunction with other preventive measures, such as nitroglycerin administration, maintaining a sheath-to-artery ratio of less than one, and prophylactic ipsilateral compression of the ulnar artery (3). Third, the factors that may confound the use of DOACs in RAO resolution remain unclear, warranting further investigation.

5 Conclusion

This meta-analysis suggests that DOACs are a promising adjunctive strategy for reducing the incidence of RAO. However, generalization to all radial procedures is premature, as these findings, based on GRADE assessment and TSA, require further confirmation. Moreover, due to the limited number of RCTs, the evidence remains uncertain, making it difficult to draw a definitive conclusion regarding the efficacy of DOACs in resolving established RAO.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

AmA: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Resources, Conceptualization, Project administration. AbA: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Visualization, Resources, Project administration. MAlz: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Project administration, Resources, Methodology. AlA: Project administration, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis. OaA: Writing – original draft, Data curation, Investigation, Resources, Formal analysis. MAla: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Investigation. YA: Writing – original draft, Resources. AAli: Writing – review & editing, Resources, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis. OmA: Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Resources. AbdA: Investigation, Validation, Writing – review & editing, Software, Methodology, Resources, Data curation, Visualization, Project administration, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcvm.2026.1653388/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Abdelazeem B Abuelazm MT Swed S Gamal M Atef M Al-Zeftawy MA et al The efficacy of nitroglycerin to prevent radial artery spasm and occlusion during and after transradial catheterization: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Cardiol. (2022) 45:1171–83. 10.1002/clc.23906

2.

Ferrante G Rao SV Jüni P Da Costa BR Reimers B Condorelli G et al Radial versus femoral access for coronary interventions across the entire spectrum of patients with coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. (2016) 9:1419–34. 10.1016/j.jcin.2016.04.014

3.

Didagelos M Afendoulis D Pagiantza A Moysidis D Papazoglou A Kakderis C et al Treatment of radial artery occlusion after transradial coronary catheterization: a review of the literature and proposed treatment algorithm. Hellenic J Cardiol. (2025) 84:81–95. 10.1016/j.hjc.2025.01.008

4.

Lawton JS Tamis-Holland JE Bangalore S Bates ER Beckie TM Bischoff JM et al ACC/AHA/SCAI guideline for coronary artery revascularization: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2021) 2022(79):e21–129. 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.09.006

5.

Byrne RA Rossello X Coughlan JJ Barbato E Berry C Chieffo A et al ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes: developed by the task force on the management of acute coronary syndromes of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. (2023) 2024(13):55–161. 10.1093/ehjacc/zuad107

6.

Rigattieri S Valsecchi O Sciahbasi A Tomassini F Limbruno U Marchese A et al Current practice of transradial approach for coronary procedures: a survey by the Italian Society of Interventional Cardiology (SICI-GISE) and the Italian Radial Club. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. (2017) 18:154–9. 10.1016/j.carrev.2017.01.005

7.

Shroff AR Fernandez C Vidovich MI Rao S V Cowley M Bertrand OF et al Contemporary transradial access practices: results of the second international survey. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. (2019) 93:1276–87. 10.1002/ccd.27989

8.

Bertrand OF Rao SV Pancholy S Jolly SS Rods-Cabau J Larose É et al Transradial approach for coronary angiography and interventions: results of the first international transradial practice survey. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. (2010) 3:1022–31. 10.1016/j.jcin.2010.07.013

9.

Rashid M Kwok CS Pancholy S Chugh S Kedev SA Bernat I et al Radial artery occlusion after transradial interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. (2016) 5:e002686. 10.1161/JAHA.115.002686

10.

Bernat I Aminian A Pancholy S Mamas M Gaudino M Nolan J et al Best practices for the prevention of radial artery occlusion after transradial diagnostic angiography and intervention: an international consensus paper. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. (2019) 12:2235–46. 10.1016/j.jcin.2019.07.043

11.

Yonetsu T Kakuta T Lee T Takayama K Kakita K Iwamoto T et al Assessment of acute injuries and chronic intimal thickening of the radial artery after transradial coronary intervention by optical coherence tomography. Eur Heart J. (2010) 31:1608–15. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq102

12.

Kotowycz MA Dẑavík V . Radial artery patency after transradial catheterization. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. (2012) 5:127–33. 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.111.965871

13.

Rymer JA Rao S V . Preventing acute radial artery occlusion: a battle on multiple fronts. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. (2018) 11:2251–3. 10.1016/j.jcin.2018.09.018

14.

Abuelazm M Abdelazeem B Katamesh BE Gamal M Simhachalam Kutikuppala LV Kheiri B et al The efficacy and safety of direct oral anticoagulants versus standard of care in patients without an indication of anti-coagulants after transcatheter aortic valve replacement: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Med. (2022) 11:6781. 10.3390/JCM11226781

15.

Abuelazm M Mahmoud A Ali S Gamal M Elmezayen A Elzeftawy MA et al The efficacy and safety of direct factor Xa inhibitors versus vitamin K antagonists for atrial fibrillation in patients on hemodialysis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). (2023) 36:736–43. 10.1080/08998280.2023.2247958

16.

Awad AK Abuelazm M Adhikari G Amin AM Elhady MM Awad AK et al Antithrombotic strategies after transcatheter aortic valve replacement in patients without an indication of oral anticoagulants: a network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Cardiol Rev. (2024). 10.1097/CRD.0000000000000791

17.

Hammami R Abid S Jihen J Triki Z Ben Mrad I Kammoun A et al Prevention of radial artery occlusion with rivaroxaban after trans-radial access coronary procedures: the RIVARAD multicentric randomized trial. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2023) 10:1–9. 10.3389/fcvm.2023.1160459

18.

Maadani M Ardestani SS Rafiee F Rezaei-Kalantari K Rabiee P Kia YM et al Rivaroxaban versus enoxaparin in patients with radial artery occlusion after transradial coronary catheterization: a pilot randomization trial. Vasc Specialist Int. (2025) 41:2–7. 10.5758/vsi.240103

19.

Liang D Lin Q Zhu Q Zhou X Fang Y Wang L et al Short-term postoperative use of rivaroxaban to prevent radial artery occlusion after transradial coronary procedure: the RESTORE randomized trial. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. (2022) 15:E011555. 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.121.011555

20.

Amirpour A Zavar R Seifipour A Sadeghi M Shirvani E Kermani-Alghoraishi M et al Apixaban, a novel oral anticoagulant, use to resolute arterial patency in radial artery occlusion due to cardiac catheterization; a pilot randomized clinical trial. ARYA Atheroscler. (2023) 19:18–26. 10.48305/arya.2023.41915.2909

21.

Page MJ McKenzie JE Bossuyt PM Boutron I Hoffmann TC Mulrow CD et al The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst Rev. (2021) 375(10):n71. 10.1186/s13643-021-01626-4

22.

Higgins JPTTJ Chandler J Cumpston M Li T Page MJWV . editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons (2023).

23.

Sterne JAC Savović J Page MJ Elbers RG Blencowe NS Boutron I et al Rob 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. Br Med J. (2019) 366:l4898. 10.1136/BMJ.L4898

24.

Guyatt GH Oxman AD Kunz R Vist GE Falck-Ytter Y Schünemann HJ . Rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations: what is “quality of evidence” and why is it important to clinicians?BMJ Br Med J. (2008) 336:995. 10.1136/BMJ.39490.551019.BE

25.

Guyatt GH Oxman AD Vist GE Kunz R Falck-Ytter Y Alonso-Coello P et al Rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations: GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ Br Med J. (2008) 336:924. 10.1136/BMJ.39489.470347.AD

26.

Lin L Chu H . Quantifying publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. (2018) 74:785–94. 10.1111/biom.12817

27.

TSA—ctu.dk. (2021). Available online at:http://ctu.dk/tsa/(Accessed December 17, 2024).

28.

Sakai H Ikeda S Harada T Yonashiro S Ozumi K Ohe H et al Limitations of successive transradial approach in the same arm: the Japanese experience. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. (2001) 54:204–8. 10.1002/ccd.1268

29.

Majeed Z Tariq MH Ahmed A Usama M Amin AM Khan A et al Comparison of sheathless and sheathed guiding catheters in transradial percutaneous coronary interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis: sheathless vs sheathed catheter for PCI. J Interv Cardiol. (2024) 2024. 10.1155/2024/2777585

30.

Tsigkas G Papanikolaou A Apostolos A Kramvis A Timpilis F Latta A et al Preventing and managing radial artery occlusion following transradial procedures: strategies and considerations. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. (2023) 10:283. 10.3390/jcdd10070283

31.

Pancholy SB Patel V Pancholy SA Patel AT Patel GA Shah SC et al Comparison of diagnostic accuracy of digital plethysmography versus duplex ultrasound in detecting radial artery occlusion after transradial access. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. (2021) 27:52–6. 10.1016/j.carrev.2020.07.025

Summary

Keywords

angiography, apixaban, edoxaban, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), rivaroxaban, transradial

Citation

Alsubaiei AA, Alfehaid AA, Alzayed MM, Artam AS, Almutairi OT, Alajmi MSA, Alaraibi YH, Alibrahim AA, Alawadhi OF and Alharran AM (2026) Direct oral anticoagulants are effective in preventing but not resolving radial artery occlusion: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 13:1653388. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2026.1653388

Received

30 June 2025

Revised

13 January 2026

Accepted

19 January 2026

Published

11 February 2026

Volume

13 - 2026

Edited by

Hugo Ten Cate, Maastricht University Medical Centre, Netherlands

Reviewed by

Simona Minardi, University of L'Aquila, Italy

José G. Paredes-Vázquez, Tecnologico de Monterrey, Mexico

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Alsubaiei, Alfehaid, Alzayed, Artam, Almutairi, Alajmi, Alaraibi, Alibrahim, Alawadhi and Alharran.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Abdullah M. Alharran Abdullahah@agu.edu.bh

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.