Abstract

With the increasing incidence and prevalence of atherosclerosis (AS), it has become a major global public health concern. While interventional surgery and Western medicines are effective in treating AS, their adverse effects are noteworthy. Traditional Chinese medicine offers the advantage of low side effects and significant therapeutic effects, making its active ingredients potential candidates for new medicine development. Panax notoginseng saponin (PNS), a compound derived from the natural drug panax notoginseng, has shown significant efficacy in AS treatment by targeting six main aspects: anti-inflammation, regulation of lipid metabolism, anti-oxidative stress, inhibition of vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration, inhibition of angiogenesis, and regulation of autophagy. This study reviews the pharmacological mechanisms of PNS in AS treatment, as well as its biological properties, in vivo metabolism, synthesis, and regulation, providing insights for future research.

1 Introduction

Atherosclerosis (AS) is a long-lasting chronic inflammatory disease of large and medium-sized arteries (1); it can further develop into a wide range of cardiovascular diseases (CVD) such as coronary heart disease and cerebral infarction (2). CVD, the incidence of which increases gradually with age, are major diseases that seriously jeopardize human health and life and are the leading cause of death and reduced quality of life worldwide (3, 4). As a result, there is an urgent need to ramp up research on therapeutic drugs for AS. The pathology of AS is characterized by impaired endothelial lipid deposition or inflammatory response in the arteries, platelet aggregation in the endothelium, foam cell formation, and formation of atherosclerotic plaques, leading to lumen narrowing and wall thickening (5). In addition, the plaque formative process includes intra-plaque bleeding, plaque bursting, and calcification, which leads to the formation of blood clots, arterial vascular occlusion, and ischemia or necrosis of tissues or organs (6), which in severe cases can lead to acute myocardial infarction, cerebral infarction and other diseases. Nowadays, AS has now become a major public health problem of global concern.

With the development of medical technology, the efficacy of interventional and revascularization procedures for the treatment of atherosclerotic disease is remarkable, but they can greatly increase the economic burden on society and patients. The main medication drugs for AS include statins and aspirin, which generally require lifelong use. Numerous studies have proven drug resistance and adverse effects of statins and aspirin when taken for long periods (7–9). Statins and proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin 9 (PCSK 9) inhibitors decrease low-density lipoprotein (LDL)-cholesterol to low levels, but do not eliminate the cardiovascular risk of other factors contributing to AS or the atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease pathway (10). As a result, the search for new therapeutic approaches and natural drugs in treating AS has received much attention. Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) has significant efficacy in treating CVD, with enjoys strengths multi-targeting, low cost, and less negative effects, and is becoming increasingly popular worldwide (11); it treats CVD by regulating lipid metabolism, oxidative stress, inflammatory response, and other mechanisms (12).

Panax notoginseng saponin (PNS) is the main component of panax notoginseng. Modern studies have proved that PNS have various pharmacologic effects, such as adjusting lipid metabolism (13), anti-inflammatory (14), anti-oxidative stress (15), anti-cancer and regulating intestinal microbiota (16). PNS is widely used in treating AS, CVD, diabetes, cancer and other diseases (17, 18). This paper describes six aspects of the role of PNS on AS and its mechanism from anti-inflammation, regulation of lipid metabolism, anti-oxidative stress, inhibition of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) proliferation and migration, inhibition of angiogenesis and regulation of autophagy. In addition, we present PNS sources, metabolism, synthesis and regulation. Our review will provide a basis for the clinical value of PNS.

2 Biological characteristics of panax notoginseng

2.1 The name of panax notoginseng

Panax notoginseng (Burk.) F. H. Chen has been used for more than 600 years and is one of the herbs widely used in TCM. Panax notoginseng belongs to the pentacarpaceae family and was first recorded in the “Compendium of Materia Medica (1785)” written by Shizhen Li, abbreviated as tian qi, jin buhuan, which can stop bleeding, disperse blood and relieve pain. It is widely used in treating CVD, such as AS, ischemic brain injury, and occlusive vasculitis.

2.2 The primary active component of panax notoginseng saponin

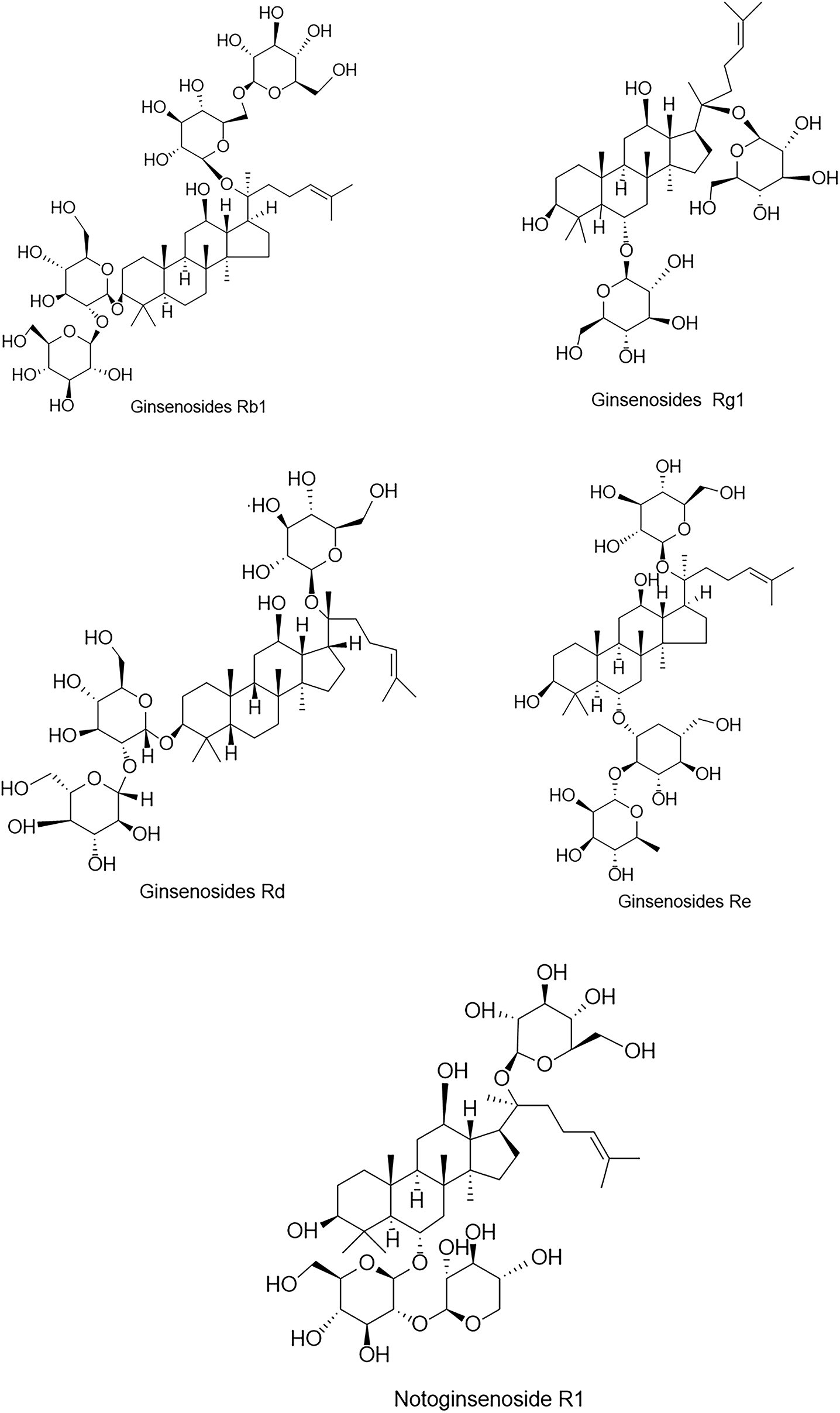

Panax notoginseng containing about 200 compounds, including saponins, flavonoids, cyclic peptides, sterols, and amino acids, etc., of which PNS is the major activity component of panax notoginseng (19). PNS are predominantly dammarane triterpenes with 20 (S)-protobirdiol or 20 (S)-protobirditriol aglycon moieties and contain about 30 kinds of saponins, among them, ginsenosides Rb1 (Rb1), ginsenosides Rg1 (Rg1), ginsenosides Rd (Rd), ginsenosides Re (Re) and notoginsenoside R1 (NGR1) were the most abundant (20), and their chemical structures (Figure 1). Drugs with PNS as the main ingredient include xueshuantong injection, xuesaitong injection, etc., which are widely used in treating acute myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, and cerebral infarction (21–25).

Figure 1

Chemical structures of the five major components in PNS.

2.3 Biosynthesis and regulation of ginsenosides in Panax notoginseng saponin

The biosynthesis of ginsenosides involves three stages: formation of the ginsenoside skeleton, glycosome synthesis, and modification of the skeleton (26). The biosynthesis of ginsenosides involves the mevalonic acid (MVA) pathway in the cytoplasm and the methylerythritol phosphate (MEP), which are largely similar in Panax notoginseng (27). First, the terpenoid precursor isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP) and its isomer dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP) are synthesized, then converted into geranyl pyrophosphate and farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP). Two molecules of FPP combine via squalene synthase to form squalene (28). Squalene is converted by squalene epoxidase and dammarane diol synthase into 2,3-epoxysqualene, which undergoes hydroxylation by cytochrome P450 enzymes and glycosylation by uridine diphosphate-dependent glycosyltransferases to ultimately form ginsenosides (29). Transcription factors participate in the synthetic regulation of PNS by upregulating the expression levels of PnSS, PnSE, and PnDS, thereby increasing the levels of R1, Rg1, Re, Rb1, and Rd (30). PnNAC2 binds to PnSS, PnSE, and PnDS, activating their transcription to promote the synthesis of PNS (31).

2.4 The in vivo metabolism of panax notoginseng saponin

PNS exhibit poor absorption in human blood and have very low oral bioavailability. In recent years, increasing research has focused on the biotransformation of exogenous substances and drug metabolism mediated by the gut microbiota (32). Research indicates that glycosylation is the primary metabolic pathway for panaxosides through the gut microbiota, with the main metabolites being α-F1, protopanaxatriol (PPT), α-Rh 2, ginsenoside compound K (GCK), and protopanaxadiol (PPD) (33). Researchers employed UPLC-MS/MS to determine the concentrations of 28 PNS components in rat plasma and investigated the pharmacokinetics. Results indicated that Rb1, Rg1, R1, Re, and Rd were the primary plasma components detected after PNS administration. Following oral dosing, Rb1 and Rd accounted for 60% of total PNS exposure, while Rg1 and R1 accounted for only 0.7%. Re was not detected in plasma. The primary metabolites in vivo were PPD, PPT, and CK. PPD-type ginsenosides may be the primary pharmacologically active components in the body following oral administration. PPD-type glycosides such as Rb1 and Rd are first biochemically transformed to diglycosylated ginsenoside F2 and then to monoglycosylated GCK, and finally metabolized into deglycosylated ginsenoside PPD (34). The biotransformation pathways of PNS in gut microbiota-mediated metabolic processes include products of isomerization, hydration, dehydration, hydrogenation, dehydrogenation, oxidation, and acetylation reactions. The primary metabolites in vivo and in vitro are GCK and Rh2, with deglycosylation reactions being the main metabolic pathway (35).

3 Effect and mechanism of panax notoginseng saponin in atherosclerosis

Numerous research studies have identified hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, hyperuricemia, homocysteinemia, smoking, and obesity as risk factors for AS. Recent investigations have shown that PNS, a natural drug, has potential in treating AS by modulating lipid metabolism and inflammation, inhibiting VSMCs proliferation and migration, and improving vascular endothelial cell injury (36–38). With significant efficacy and minimal side effects, PNS could be a promising option for AS treatment. Reviewing existing literature, PNS is observed to have effects in six key areas: anti-inflammation, regulation of lipid metabolism, anti-oxidative stress, inhibition of VSMCs proliferation and migration, inhibition of angiogenesis, and autophagy. This paper aims to provide a comprehensive review of the mechanisms by which PNS acts against AS, focusing on these six aspects.

3.1 Anti-inflammatory

AS is usually recognized as a chronic inflammatory disease, which is itself a process of inflammatory response, with a variety of inflammatory cells and inflammatory factors playing important roles in all stages of its pathogenesis (39, 40). The recruitment of leukocytes and pro-inflammatory cytokines plays a key role in the early stages of AS (41). In advanced stages of AS, inflammation also plays an important part, mainly manifested by the infiltration of large numbers of macrophages and other inflammatory cytokines into the vessel wall and the secretion of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which degradation of collagen fibers in the extracellular matrix of plaques, leading to plaque rupture, bleeding and thrombosis (42).

Adhesion of monocytes to vascular endothelial cells is an essential step in the atherosclerotic process (43). Monocytes play a determining role in the expression of endothelial cell-associated adhesion molecules, which mediate the transendothelial migration of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), thereby generating an inflammatory response (44). PNS has been shown to inhibit monocyte adhesion to the endothelium and the expression of TNF-α induced endothelial adhesion molecules (such as ICAM-1 and VCAM-1), thereby inhibiting endothelial cell hyperadhesiveness (45). In addition, numerous studies have reported that the massive release of inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β is a major contributor to AS. Oxidized low-density lipoprotein (ox-LDL) transiently stimulates endothelial cells, leading to an increase in the production of pro-inflammatory factors via the phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways, which is manifested by the infiltration of large numbers of macrophages and other inflammatory cytokines into the vascular wall and the secretion of MMPs that degrade collagen fibres in the extracellular matrix of the plaque, leading to plaque rupture, haemorrhage and bleeding (46). Su et al. (47) study found that PNS was able to reduce ox-LDL induced TNF-α and IL-1β expression levels in EA. hy926 cells, thus play a role in treating AS. Macrophage polarization and inflammatory responses play an important role in regulating plaque stability, and Rb1 increases IL-4 and IL-13 production and signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 (STAT6) phosphorylation and promotes anti-inflammatory M2 macrophage polarization to enhance atherosclerotic plaque stability (48).

It has been demonstrated that miR-221-3p is upregulated in AS and is involved in the pathogenesis of AS (49). Toll-like receptor-4 (NLR4) expression is upregulated in atherosclerotic plaques, and NLR4 mediates tumor nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) activation, leading to the overproduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α (50). NGR1 inhibits TLR4/NF-κB pathway activation by increasing miR-221 -3p expression and inhibits ox-LDL-induced apoptosis and inflammatory responses in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) (51). Increasing evidence suggests that activation of MAPK and nuclear NF-κB may lead to reactive oxygen species (ROS) overproduction and upregulation of VCAM-1, ICAM-1 and monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) (52). It has been hypothesized that excessive ROS production upregulates the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and adhesion molecules, thereby promoting the progression of AS (53). Dou et al. (54) found that in the aortic root of apolipoprotein e-deficient apoE-/-mice, PNS blocked ROS production, which in turn inhibited the receptor for advanced glycation end-products (RAGE)/MAPK signaling pathway, deactivated NF-κB, and reduced expression of the pro-inflammatory factors VCAM-1, ICAM-1, and MCP-1. Su et al. (47) also found that PNS can inhibit ox-LDL induced inflammatory cytokine production by activating peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR-γ), which inhibits NF-κB and MAPK activation.

3.2 Regulation of lipid metabolism

Disorders of lipid metabolism are independent risk factors for AS (55). Excess serum lipids penetrate the blood vessel wall and deposit in the artery lining, triggering early atherosclerotic damage (56). Cholesterol and the accumulation of cholesterol lipids are major components of atherosclerotic plaque. A large number of studies have shown that elevated levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), triglycerides (TG), and total cholesterol (TC), as well as decreased levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), are closely are closely linked to the onset and the development of atherosclerosis (57). Experimental studies in the AS model of apoE-/-mice showed that PNS significantly decreased TG, TC, and LDL-C levels and significantly increased HDL-C levels (58).

The ox-LDL may be involved in the progression of atherosclerotic lesions via foam cells. In the apoE-Ko AS mouse model, blood levels of ox-LDL were elevated, and PNS decreased blood levels of ox-LDL in mice (59). It is well known that low-density lipoprotein is a major causative factor in AS. The low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) mediates the uptake and degradation of LDL in plasma, whereas PCSK9 binds to the extracellular structural domain of LDLR and mediates the degradation of LDLR (60, 61). 20(S)-protopanaxadiol is a class of constituents of PNS (19); it binds directly to the extracellular structural domain of the LDLR and inhibits the interaction between PCSK9 and the LDL receptor, thereby raising LDLR levels and alleviating atherosclerosis (62).

Lipid macrophages, often referred to as foam cells, are the central component of plaques and are characteristic of atherosclerotic plaques (63). Foam cells are formed from the uptake of lipids oxidised by activated monocytes/macrophages. In this process, modified lipoproteins enter the cell via a receptor and excess neutral lipids are stored as lipid droplets (64). ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 (ABCA1) reduces excess lipids in the cell, thereby preventing foam cell formation (65). PNS can reduce cholesterol ester by upregulating ABCA1 expression and lowering cholesterol ester levels, thereby inhibiting foam cell formation (66). ABCA1 and ATP-binding cassette transporter G1 (ABCG1) mediate cellular cholesterol efflux in the presence of receptors (e.g., HDL), and the liver X receptor alpha (LXRα) can directly regulate ABCA1 and ABCG1 expression (67). PNS was found to increase transcriptional activation of the LXRα gene promoter and subsequently upregulate ABCA1 and ABCG1 (36). Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) participates in atherosclerosis development by regulating glycolysis and macrophage polarization. Studies indicate that in mouse atherosclerosis models, PNS effectively suppresses abnormal glycolysis induced by HIF-1α overexpression, thereby inhibiting M1 macrophage polarization while promoting M2 macrophage polarization and modulating sphingolipid metabolism (68).

3.3 Anti-oxidant stress

Oxidant stress is a condition in which the body is stimulated by internal and external factors, leading to an increase in the production of ROS, resulting in an imbalance between oxidative and anti-oxidant effects in the body (69). ROS react with LDL to form ox-LDL (70); ox-LDL induces endothelial cells to express cell adhesion factors, which stimulate monocyte to macrophage differentiation and mediate lipid accumulation; it also induces the expression of CD36 and p-selectin in platelets, which promotes platelet activation and the release of chemokines, resulting in epithelial dysfunction, foam cell formation, which the promotion of atherosclerotic plaque formation (71). Numerous studies have shown that upregulation of anti-oxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), reduced glutathione (GSH), and glutathione peroxidase (GPx) levels in artery wall inhibits endothelial dysfunction and ox-LDL formation (72).

Inhibition of oxidative stress by PNS is gaining widespread attention. Nuclear factor E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) is a protein that regulates endogenous antioxidant defense and plays a crucial role in activating the downstream heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) to counteract intracellular ROS and anti oxidative stress (73). In a mouse model of diabetic nephropathy, PNS up-regulated GSH and SOD expression and down-regulated malondialdehyde (MDA) expression by modulating the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway (74); in vitro experiments, NGR1 reduced the mitochondrial damage induced, limited the increase of ROS, promoted the expression of Nrf2 and HO-1, and reduced HK-2 cell apoptosis (75). PNS activated the PI3K/protein kinase (Akt)/Nrf2 pathway and up-regulates HO-1 expression, thereby anti-oxidant stress injury and ameliorating cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury (76, 77). Zhang et al. (15) 0.2 mM H2O2 treated HUVECs for 12 h, and the cell survival rate of HUVECs was about 70%. Subsequently, HUVECs with different concentrations (20–200 mg/mL) of PNS were treated for 24 h. It was found that the cell survival rate could be increased by 37% at 200 mg/mL PNS. Compared with the control group, PNS significantly improved the stability of the cytoskeleton and maintained the normal morphology and physiological function of the cells. It has been shown that Rb1 ameliorates H2O2-induced HUVEC senescence and dysfunction through the Sirtuin-1/AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) pathway (78). In the rat AS model, serum NO and SOD contents were increased and TNF-α contents were reduced by PNS or Rb1 treatment. In vitro PNS or Rb1 treatment alleviated H2O2-mediated cytotoxicity in endothelial cells, down-regulated ox-LDL induction of p38 and VCAM-1 expression (79).

3.4 Inhibition of vascular smooth muscle cells proliferation and migration

VSMCs play a crucial role in the formation of AS. In the early stage, the migration and proliferation of VSMCs within the intima contribute to the formation of atherosclerotic plaques, and in the late stage, VSMCs form a fibrous cap to stabilize vulnerable plaques; also participate directly in the process of AS formation through the formation of macrophage foam cells (80). VSMCs are one of the major cellular components that maintain vascular tone and function. Studies have demonstrated that abnormal proliferation of VSMCs induces the development of AS when the endothelium is damaged.

The levels of cyclin D1 and cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (CDK4) as positive regulators of the VSMCs cycle, and P21 protein as a negative regulator of the VSMCs cycle. In one study, in VSMCs cultured after platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) stimulation, TPNS decreased cyclin D1 and CDK4 content and increased P21 protein content, thereby inhibiting the proliferation of VSMCs (81). VSMCs were isolated from the thoracic aorta of rats and incubated with different concentrations of PNS (0.2–0.8 ug/ml), and then the cells were stimulated with PDGF for 24 h. The results showed that PNS significantly inhibited the proliferation of VSMCs by up-regulating the expression of P53, Bax, and caspase-3 proteins, and down-regulating the expression of Bcl-2 protein, induced apoptosis of VSMCs after proliferation (37). Resistin is an adipokine primarily expressed in human monocyte/macrophage lineage cells, and pathological concentrations of resistin promote VSMC proliferation and migration (82, 83). The PI3K/Akt pathway is a classical pathway for VSMCs proliferation and migration, and activation of PI3K activates phosphorylation of the downstream factor Akt to inhibit VSMCs proliferation and migration (84). Rb1 inhibits pathological concentrations of resistin that inhibition VSMC proliferation and migration, and can decrease the expression of ROS and increase the expression of SOD (85). It was shown that NGR1 inhibits VSMC proliferation and migration by inhibiting the PI3K/Akt pathway and regulating actin dynamics (86).

3.5 Inhibition of angiogenesis

During AS, intraplaque angiogenesis promotes AS progression and plaque destabilization. Cell adhesion molecules are highly expressed in plaque neovascularization, thereby further facilitating recruiting of inflammatory cells into the plaque (87). Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is a pro-angiogenic factor that induces VEGF expression to promote angiogenesis under hypoxic conditions. The main receptors for VEGF, VEGF-1 and VEGF-2, play crucial roles in intraplaque angiogenesis. Activation of VEGF-1 receptor results in migration of inflammatory cells and release of inflammatory factors, and activation of VEGF-2 stimulates angiogenesis, migration, and proliferation of endothelial cells (88).

It was found that PNS could alleviate atherosclerotic plaque angiogenesis and attenuate the process of AS. It was demonstrated that CD34 promotes VEGF-induced neovascularization germination and is involved in neovascularization in the retinal periphery (89). In the apoE-Ko mouse model, PNS down-regulated expressions of VEGF, CD34, and NADPH oxidase 4 (NOX4) proteins, reducing plaque area and the number of plaque neovascularization (90). In a rabbit iliac artery balloon endothelial stripping injury model, PNS downregulated the expression of VEGF and MMP-2, promoted endothelial cell regeneration, and reduced extracellular matrix thickening (91). Pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) is an anti-angiogenic cytokine that inhibits VEGF-induced angiogenesis by inducing endothelial cell apoptosis and enhancing VEGF-1 cleavage (92). MiR-33a reduces cholesterol efflux and inhibits VEGF-2 signaling and angiogenesis in vitro. In an in vitro experiment, Rb1 was found to exert anti-angiogenic effects by regulating miR-33a and PEDF expression (93).

3.6 Regulation of autophagy

Autophagy is a highly conserved cellular degradation and recycling process in all eukaryotes. Increasing evidence suggests that autophagy plays a key role in suppressing inflammation and apoptosis, promoting efferocytosis and cholesterol efflux. Autophagy markers p62 and LC3-II are expressed in atherosclerotic plaques. Their reduction cause dead cells to accumulate in the arterial wall and contribute to plaque destabilization (94). P62 is the most prototypical substrate for selective autophagy, acting as a signaling hub that can determine cell survival by activating the TNF receptor-associated factor 6/NF-κB pathway or cell death by promoting caspase aggregation (95).

In the apoE-/-mouse AS model, Rb1 upregulates Bcl-2/Bax expression, decreases p62 expression, promotes LC3 conversion from type I to type II, and promotes autophagy to inhibit apoptosis (96). Macrophage autophagy is the most widely studied type of autophagy, and AMPK is the major kinase regulating macrophage autophagy (97); ox-LDL promotes macrophage conversion to foam cells and macrophage apoptosis promotes plaque necrosis, leading to plaque instability. Rb1 increased the expression of autophagy-related gene 5 (Atg5) and ABCA1, induced macrophage autophagy, reduced lipid accumulations in macrophage foam cells, and enhanced the stabilization of plaques (98). Evidence suggests that AMPK regulates autophagy through downstream signaling pathways, thereby inhibiting apoptosis and inflammation, promoting cholesterol efflux (99). Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) is activated in advanced atherosclerotic plaque macrophages and drives plaque necrosis by inhibiting expression of the efferocytosis receptor macrophage c-mer tyrosine kinase, whose upregulation promotes plaque stability (100). In a mouse model of acute myocardial infarction, PNS promotes autophagy in cardiomyocytes by promoting the phosphorylation of AMPK and CaMKII, upregulating LC3II/I expression and downregulating p62 expression (101). Rg1 activates the AMPK/mTOR pathway, upregulates the expression of Atg5, Beclin1, LC3, and downregulating p62 expression promotes autophagy, and inhibits apoptosis (102). Mitochondrial autophagy is an important process for the elimination of dysfunctional mitochondria regulation of multiple autophagies plays a very important role in both the early and late processes of AS (103). PNS regulates the expression of PTEN-induced putative kinase 1 (PINK1), promotes mitochondrial autophagy, reduces ROS accumulation, and also modulates calcium homeostasis dysregulation (104).

Hypoxia or ischemia induces HIF-1α activation, which maintains cell survival by activating the downstream protein BCL2 interacting protein (BNIP3), which induces mitochondrial autophagy direct binding to LC3 (105). In a rat model of myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury, PNS upregulated the expression of HIF-1α, BNIP3, Atg5, LC3, and Beclin-1 in myocardial tissues, which demonstrated that PNS enhances mitochondrial autophagy via the HIF-1α/BNIP3 pathway (106).

4 Dose-response relationship and clinical translation considerations

As shown in Table 1, the optimal concentration of Panax notoginsenosides in vitro cell models is typically around 20 μM, while in AS animal models, the optimal oral dosage generally ranges from 60 to 120 mg/kg/day. Different monomers exhibit varying concentrations required to act on distinct pathways, demonstrating target specificity. Converting animal doses to human equivalent doses is a critical step in preclinical research. Taking the effective dose of 60 mg/kg/d for PNS in mouse studies as an example, preliminary estimation based on body surface area conversion suggests a rough human equivalent dose of approximately 6.6 mg/kg/d. Current dose calculations remain theoretical projections; actual clinical dosages must be determined through rigorous clinical trials. Current research still faces significant limitations: First, most studies utilize PNS extracts with inconsistent ratios of individual components, making precise dose-response relationships difficult to define. Second, research on PNS's oral bioavailability, tissue distribution, and metabolic conversion remains insufficient, complicating the correlation between effective in vitro concentrations and required in vivo dosages.

Table 1

| Compounds/extracts | Model | Target/mechanism | Optimal dose | Administration time | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PNS | ApoE-/- mouse | Modulation of inflammatory responses and lipid regulation | 12.0 mg/Kg/d | 8 weeks | (45) |

| PNS | HCAECs | Modulation of inflammatory responses and lipid regulation | 300 μg/ml | 24 h | (45) |

| NGR1 | EA.hy926 cell | Activates PPARγ expression and inhibits NF-κB and MAPK activation | 100 μM | 24 h | (47) |

| Rb1 | Macrophage | Macrophage polarization | 20 μM | 24 h | (48) |

| PNS | ApoE-/- mouse | Inhibits RAGE/MAPK signaling pathways | 60 mg/Kg/d | 4 weeks | (54) |

| PNS | ApoE-/- mouse | Inhibits NF-κB signaling pathway | 180 mg/Kg/d | 8 weeks | (58) |

| PNS | ApoE-KO mouse | lipid regulation | 60 mg/Kg/d | 12 weeks | (59) |

| PPD | HepG2 cells | Inhibit LDLR degradation | 10 μM | 24 h | (62) |

| PPD | ApoE-KO mouse | Inhibit LDLR degradation | 60 mg/Kg/d | 12 weeks | (62) |

| PNS | Macrophage | ABCA 1, LXR1 | 80 mg/L | 24 h | (66) |

| PNS | ApoE-/- mouse | HIF-1α | 120 mg/Kg/d | 4 weeks | (36) |

| PNS | RAW264.7 cells | HIF-1α | 150 μg/mL | 24 h | (36) |

| PNS | Microvascular endothelial cells of the brain | Activates PI3K/Akt/Nrf2 | |||

| Antioxidant Signaling Pathway | 400μg/mL | 24h | 78 | ||

| PNS | Mouse microvascular cerebral endothelial cells | NrF2, NF-κB | 400 μg/mL | 24 h | (77) |

| Rb1 | HCAECs | Activates SIRT1/AMPK pathway | 20 μM | 24 h | (78) |

| PNS | HCAECs | Inhibits NrF2, p38 -VCAM-1 Signal Pathway | 100 μg/ml | 24 h | (79) |

| PNS | VSMCs | p53, Bax, caspase-3 and Bcl-2 | 800 μg/mL | 24 h | (37) |

| Rb1 | HCAECs | ROS, SOD | 20 μM | 24 h | (85) |

| NGR1 | HCASMCs | PI3K/Akt signaling | 10 μM | 24 h | (86) |

| PNS | ApoE-KO mouse | NOX4, VEGF | 60 mg/Kg/d | 12 weeks | (90) |

| Rb1 | HCASMCs | miR-33 a/PPAR-γ | 20 μM | 24 h | (93) |

| Rb1 | ApoE-/- mice | Inflammation, lipid metabolism, regulation of autophagy | 10 mg/Kg/d | 8 weeks | (96) |

| Rg1 | Raw264.7 macrophages | AMPK/mTOR signaling pathway | 50 μM | 48 h | (102) |

PNS dosage schedule for AS treatment.

5 Conclusions and future perspectives

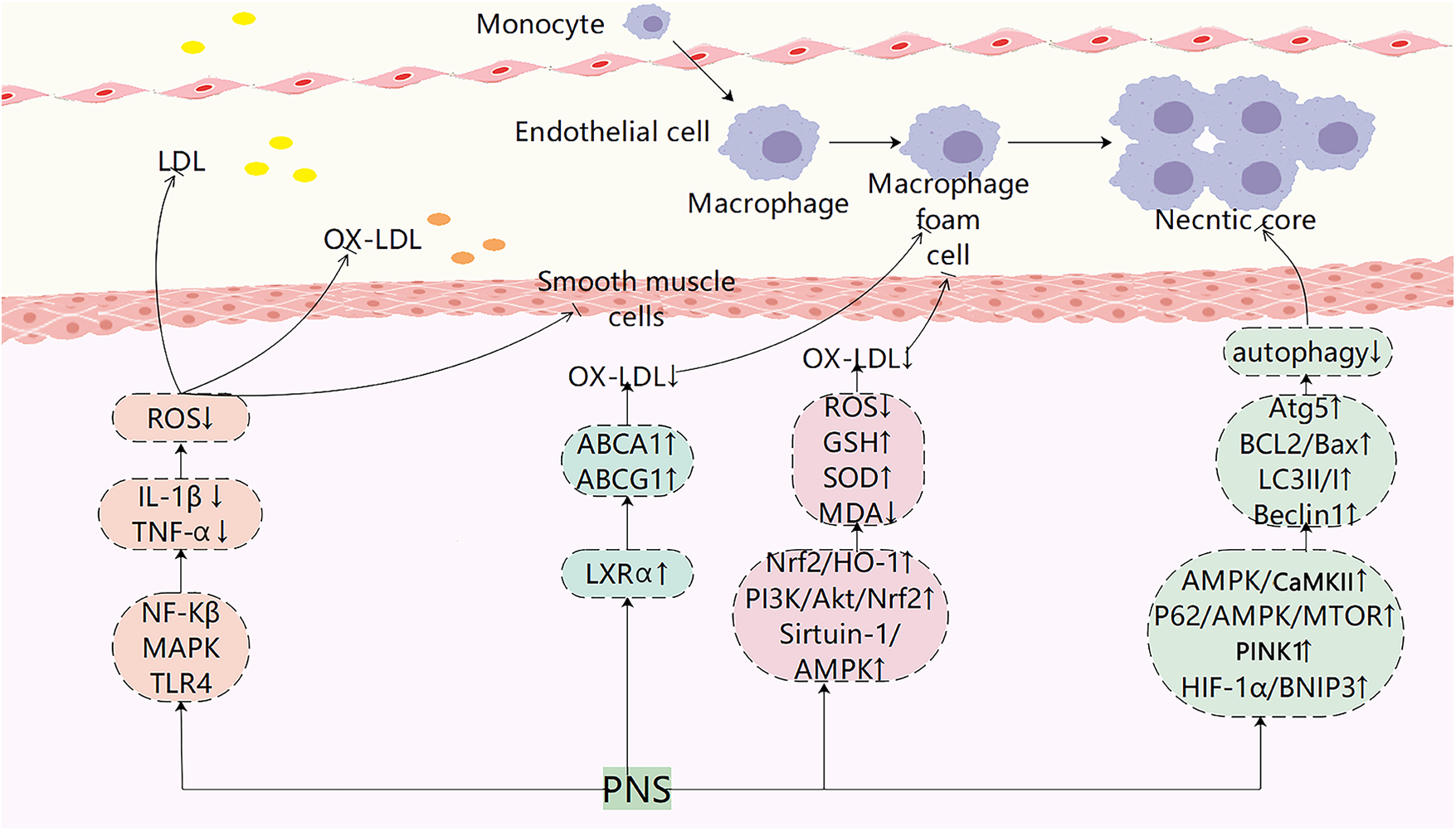

This research provides strong evidence supporting the use of PNS in the clinical treatment of AS. Recent studies have shown significant progress in the foundational understanding of AS with PNS interventions (Figure 2; Table 2). PNS has been found to modulate key pathways such as PI3K, MAPK, and TLR4/NF-κB, leading to reduced expression of inflammatory factors like TNF-α and IL-1β, as well as decreased cholesterol deposition. Additionally, PNS blocks pathways like Nrf2/HO-1, PI3K/Akt/Nrf2, AMPK, and HIF-1α/BNIP3, resulting in lower ROS levels, enhanced antioxidant defenses, protection of VSMCs and endothelial cells, and promotion of autophagy. AS emerging research areas such as exosomes, intestinal flora, and ferroptosis gain traction in AS studies, further investigations are warranted to explore the potential of PNS in regulating these mechanisms for AS treatment. Compared to other plant saponins (such as ginsenoside Rc) or phenolic compounds (such as curcumin), PNS demonstrates unique potential for multi-pathway synergistic effects in combating AS. However, the clinical application of PNS still faces significant challenges: First, its low oral bioavailability, primarily related to intestinal metabolism and permeability; second, the complex composition of PNS, where the specific monomer or combination playing a key role and its definitive target proteins remain to be confirmed; third, existing studies are predominantly preclinical models, lacking high-quality human evidence-based medical data. To address these limitations, future research should focus on: enhancing bioavailability through structural modifications or novel delivery systems; precisely identifying molecular targets using chemical biology approaches; and conducting rigorously designed randomized controlled clinical trials to provide novel perspectives and insights.

Figure 2

Pharmacological mechanisms of PNS in atherosclerotic plaque evolution. PNS exerts anti-atherosclerotic effects by modulating multiple signaling pathways, including suppressing inflammatory responses, regulating lipid metabolism, reducing LDL oxidation, inhibiting foam cell formation, suppressing smooth muscle cell migration, and regulating autophagy.

Table 2

| Chemicals | Effect | Mechanisms | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| PNS | Anti-inflammatory | Inhibition of adhesion factor expression and lipid lowering | (45) |

| NGR1 | Activates PPARγ expression and inhibits NF-κB and MAPK activation | (47) | |

| Rb1 | Promotes anti-inflammatory M2 macrophage polarization | (48) | |

| NGR1 | Inhibition of TLR4/NF-κB pathway activation | (51) | |

| PNS | Reduced RAGE/MAPK pathway expression and inhibited NF-κB activation | (54) | |

| PNS | Regulation of lipid metabolism | inhibited NF-κB activation, lipid lowering | (58) |

| PNS | Reduction of lipid levels and down-regulation of CD40 and MMP-9 expression | (59) | |

| PNS | Upregulation of LXRα, ABCA1 and ABCG1 expression | (36, 66) | |

| PNS, NGR1 | Anti-oxidant stress | Upregulation of the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway against oxidative stress | (74, 75) |

| PNS | Activation of PI3K/Akt/Nrf2 pathway and upregulation of HO-1 expression against oxidative stress injury | (76, 77) | |

| PNS | Improve cell viability and maintain cytoskeleton stability | (15) | |

| Rb1 | Activation of Sirtuin-1/AMPK pathway against cellular senescence | (78) | |

| PNS, Rb1 | Inhibition of ROS/TNF-α/p38/VCAM-1 pathway inhibits monocyte adhesion | (79) | |

| PNS | Inhibition of VSMC proliferation and migration | Inhibition of ERK pathway activation to suppress VSMC proliferation | (81) |

| PNS | Up-regulation of p53, Bax, and caspase-3 expression and down-regulation of Bcl-2 expression inhibited proliferation and induced apoptosis in VSMCs | (37) | |

| Rb1 | Inhibition of VSMC proliferation and migration | (85) | |

| NGR1 | Inhibition of PI3K/Akt pathway activation suppresses VSMCs proliferation | (86) | |

| PNS | Inhibition of angiogenesis | Downregulation of VEGF and NOX4 expression reduces plaque angiogenesis | (90) |

| PNS | Promote endothelial regeneration and reduce endothelial thickening | (91) | |

| Rb1 | Regulation of miR-33a and PEDF expression exerts anti-angiogenic effects through PPAR-γ signaling pathway | (93) | |

| Rb1 | Regulation of autophagy | Regulation of BCL-2 family-associated apoptosis to promote autophagy | (96) |

| Rb1 | Increases AMPK phosphorylation and induces macrophage autophagy | (98) | |

| PNS | Activation of the AMPK/CaMKII pathway promotes autophagy | (101) | |

| Rb1 | Activation of AMPK/mTOR pathway promotes macrophage autophagy | (102) | |

| PNS | Induction of PINK1 expression regulates autophagy | (104) | |

| PNS | Activation of the HIF-1α/BNIP3 pathway enhances mitochondrial autophagy in myocardial tissue | (106) |

Mechanism of action of PNS in aS.

Statements

Author contributions

LX: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JC: Writing – original draft. LL: Writing – review & editing. FY: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. Yunnan University of Traditional Chinese Medicine Joint University-Hospital Fund Project (XYLH2024016) and Yunnan Provincial Joint Special Project for basic research in Traditional Chinese Medicine (202501AZ070001-320).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Gencer S Evans BR van der Vorst EPC Döring Y Weber C . Inflammatory chemokines in atherosclerosis. Cells. (2021) 10(2):226. 10.3390/cells10020226

2.

Nayor M Brown KJ Vasan RS . The molecular basis of predicting atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk. Circ Res. (2021) 128(2):287–303. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.315890

3.

Bergmark BA Mathenge N Merlini PA Lawrence-Wright MB Giugliano RP . Acute coronary syndromes. Lancet. (2022) 399(10332):1347–58. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02391-6

4.

GBD 2017 Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980–2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet. (2018) 392(10159):1736–88. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32203-7

5.

Libby P . The changing landscape of atherosclerosis. Nature. (2021) 592(7855):524–33. 10.1038/s41586-021-03392-8

6.

Kavurma MM Rayner KJ Karunakaran D . The walking dead: macrophage inflammation and death in atherosclerosis. Curr Opin Lipidol. (2017) 28(2):91–8. 10.1097/MOL.0000000000000394

7.

Tomaszewski M Stępień KM Tomaszewska J Czuczwar SJ . Statin-induced myopathies. Pharmacol Rep. (2011) 63(4):859–66. 10.1016/s1734-1140(11)70601-6

8.

Preiss D Sattar N . Statins and the risk of new-onset diabetes: a review of recent evidence. Curr Opin Lipidol. (2011) 22(6):460–6. 10.1097/MOL.0b013e32834b4994

9.

Chiarito M Sanz-Sánchez J Cannata F Cao D Sturla M Panico C et al Monotherapy with a P2Y12 inhibitor or aspirin for secondary prevention in patients with established atherosclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. (2020) 395(10235):1487–95. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30315-9

10.

Puylaert P Zurek M Rayner KJ De Meyer GRY Martinet W . Regulated necrosis in atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. (2022) 42:11. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.122.318177

11.

Hao P Jiang F Cheng J Ma L Zhang Y Zhao Y . Traditional Chinese medicine for cardiovascular disease: evidence and potential mechanisms. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2017) 69(24):2952–66. 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.04.041

12.

Jiang Y Zhao Q Li L Huang S Yi S Hu Z . Effect of traditional Chinese medicine on the cardiovascular diseases. Front Pharmacol. (2022) 13:806300. 10.3389/fphar.2022.806300

13.

Zhang C Zhang B Zhang X Wang M Sun X Sun G . Panax notoginseng saponin protects against diabetic cardiomyopathy through lipid metabolism modulation. J Am Heart Assoc. (2022) 11(4):e023540. 10.1161/JAHA.121.023540

14.

Luo H Vong CT Tan D Zhang J Yu H Yang L et al Panax notoginseng saponins modulate the inflammatory response and improve IBD-like symptoms via TLR/NF-[formula: see text]B and MAPK signaling pathways. Am J Chin Med (Gard City N Y). (2021) 49(4):925–39. 10.1142/S0192415X21500440

15.

Zhang M Guan Y Xu J Qin J Li C Ma X et al Evaluating the protective mechanism of panax notoginseng saponins against oxidative stress damage by quantifying the biomechanical properties of single cell. Anal Chim Acta. (2019) 1048:186–93. 10.1016/j.aca.2018.10.030

16.

Xu Y Wang N Tan HY Li S Zhang C Zhang Z et al Panax notoginseng saponins modulate the gut microbiota to promote thermogenesis and beige adipocyte reconstruction via leptin-mediated AMPKα/STAT3 signaling in diet-induced obesity. Theranostics. (2020) 10(24):11302–23. 10.7150/thno.47746

17.

Gao J Yao M Zhang W Yang B Yuan G Liu JX et al Panax notoginseng saponins alleviates inflammation induced by microglial activation and protects against ischemic brain injury via inhibiting HIF-1α/PKM2/STAT3 signaling. Biomed Pharmacother. (2022) 155:113479. 10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113479

18.

Xu C Wang W Wang B Zhang T Cui X Pu Y et al Analytical methods and biological activities of Panax notoginseng saponins: recent trends. J Ethnopharmacol. (2019) 236:443–65. 10.1016/j.jep.2019.02.035

19.

Wang T Guo R Zhou G Zhou X Kou Z Sui F et al Traditional uses, botany, phytochemistry, pharmacology and toxicology of Panax notoginseng (Burk.) F.H. Chen: a review. J Ethnopharmacol. (2016) 188:234–58. 10.1016/j.jep.2016.05.005

20.

Li L Sheng Y Zhang J Guo D . Determination of four active saponins of Panax notoginseng in rat feces by high-performance liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr Sci. (2005) 43(8):421–5. 10.1093/chromsci/43.8.421

21.

Wang A Li Y Wang Z Xin G You Y Sun M et al Proteomic analysis revealed the pharmacological mechanism of Xueshuantong injection in preventing early acute myocardial infarction injury. Front Pharmacol. (2022) 13:1010079. 10.3389/fphar.2022.1010079

22.

Xi J Wei R Cui X Liu Y Xie Y . The efficacy and safety of Xueshuantong (lyophilized) for injection in the treatment of unstable angina pectoris: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Pharmacol. (2023) 14:1074400. 10.3389/fphar.2023.1074400

23.

Lyu J Xie Y Sun M Zhang L . Efficacy and safety of Xueshuantong injection on acute cerebral infarction: clinical evidence and GRADE assessment. Front Pharmacol. (2020) 11:822. 10.3389/fphar.2020.00822

24.

Hua Y Shao M Wang Y Du J Tian J Wei K et al Xuesaitong injection treating acute myocardial infarction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). (2021) 100(37):e27027. 10.1097/MD.0000000000027027

25.

Duan X Zhang D Wang K Wu J Zhang X Zhang B et al Comparative study of xuesaitong injection and compound salvia miltiorrhizae injection in the treatment of acute cerebral infarction: a meta-analysis. J Int Med Res. (2019) 47(11):5375–88. 10.1177/0300060519879292

26.

Hou M Wang R Zhao S Wang Z . Ginsenosides in Panax genus and their biosynthesis. Acta Pharm Sin B. (2021) 11(7):1813–34. 10.1016/j.apsb.2020.12.017

27.

Zhao S Wang L Liu L Liang Y Sun Y Wu J . Both the mevalonate and the non-mevalonate pathways are involved in ginsenoside biosynthesis. Plant Cell Rep. (2014) 33(3):393–400. 10.1007/s00299-013-1538-7

28.

Luo H Sun C Sun Y Wu Q Li Y Song J et al Analysis of the transcriptome of Panax notoginseng root uncovers putative triterpene saponin-biosynthetic genes and genetic markers. BMC Genomics. (2011) 12(Suppl 5):S5. 10.1186/1471-2164-12-S5-S5

29.

Augustin JM Kuzina V Andersen SB Bak S . Molecular activities, biosynthesis and evolution of triterpenoid saponins. Phytochemistry. (2011) 72(6):435–57. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2011.01.015

30.

Niu Y Luo H Sun C Yang TJ Dong L Huang L et al Expression profiling of the triterpene saponin biosynthesis genes FPS, SS, SE, and DS in the medicinal plant Panax notoginseng. Gene. (2014) 533(1):295–303. 10.1016/j.gene.2013.09.045

31.

Huang Y Shi Y Hu X Zhang X Wang X Liu S et al PnNAC2 promotes the biosynthesis of Panax notoginseng saponins and induces early flowering. Plant Cell Rep. (2024) 43(3):73. 10.1007/s00299-024-03152-8

32.

Koppel N Maini Rekdal V Balskus EP . Chemical transformation of xenobiotics by the human gut microbiota. Science. (2017) 356(6344):eaag2770. 10.1126/science.aag2770

33.

Chen MY Shao L Zhang W Wang CZ Zhou HH Huang WH et al Metabolic analysis of Panax notoginseng saponins with gut microbiota-mediated biotransformation by HPLC-DAD-Q-TOF-MS/MS. J Pharm Biomed Anal. (2018) 150:199–207. 10.1016/j.jpba.2017.12.011

34.

Fu X Chen K Li Z Fan H Xu B Liu M et al Pharmacokinetics and oral bioavailability of Panax Notoginseng saponins administered to rats using a validated UPLC-MS/MS method. J Agric Food Chem. (2023) 71(1):469–79. 10.1021/acs.jafc.2c06312

35.

Guo YP Shao L Chen MY Qiao RF Zhang W Yuan JB et al In Vivo metabolic profiles of Panax notoginseng saponins mediated by gut microbiota in rats. J Agric Food Chem. (2020) 68(25):6835–44. 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c01857

36.

Fan JS Liu DN Huang G Xu ZZ Jia Y Zhang HG et al Panax notoginseng saponins attenuate atherosclerosis via reciprocal regulation of lipid metabolism and inflammation by inducing liver X receptor alpha expression. J Ethnopharmacol. (2012) 142(3):732–8. 10.1016/j.jep.2012.05.053

37.

Xu L Liu JT Liu N Lu PP Pang XM . Effects of Panax notoginseng saponins on proliferation and apoptosis of vascular smooth muscle cells. J Ethnopharmacol. (2011) 137(1):226–30. 10.1016/j.jep.2011.05.020

38.

Liu J Jiang C Ma X Wang J . Notoginsenoside fc attenuates high glucose-induced vascular endothelial cell injury via upregulation of PPAR-γ in diabetic sprague-dawley rats. Vasc Pharmacol. (2018) 109:27–35. 10.1016/j.vph.2018.05.009

39.

Zhu Y Xian X Wang Z Bi Y Chen Q Han X et al Research progress on the relationship between atherosclerosis and inflammation. Biomolecules. (2018) 8:3. 10.3390/biom8030080

40.

Libby P Buring JE Badimon L Hansson GK Deanfield J Bittencourt MS et al Atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. (2019) 5(1):56. 10.1038/s41572-019-0106-z

41.

Wolf D Ley K . Immunity and inflammation in atherosclerosis. Circ Res. (2019) 124(2):315–27. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.313591

42.

Liu Y Yu H Zhang Y Zhao Y . TLRs are important inflammatory factors in atherosclerosis and may be a therapeutic target. Med Hypotheses. (2008) 70(2):314–6. 10.1016/j.mehy.2007.05.030

43.

Wu M Li X Wang S Yang S Zhao R Xing Y et al Polydatin for treating atherosclerotic diseases: a functional and mechanistic overview. Biomed Pharmacother. (2020) 128:110308. 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110308

44.

Shi C Pamer EG . Monocyte recruitment during infection and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. (2011) 11(11):762–74. 10.1038/nri3070

45.

Wan JB Lee SM Wang JD Wang N He CW Wang YT et al Panax notoginseng reduces atherosclerotic lesions in ApoE-deficient mice and inhibits TNF-alpha-induced endothelial adhesion molecule expression and monocyte adhesion. J Agric Food Chem. (2009) 57(15):6692–7. 10.1021/jf900529w

46.

Bekkering S Quintin J Joosten LA van der Meer JW Netea MG Riksen NP . Oxidized low-density lipoprotein induces long-term proinflammatory cytokine production and foam cell formation via epigenetic reprogramming of monocytes. Arterioscler, Thromb, Vasc Biol. (2014) 34(8):1731–8. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.303887

47.

Su P Du S Li H Li Z Xin W Zhang W . Notoginsenoside R1 inhibits oxidized low-density lipoprotein induced inflammatory cytokines production in human endothelial EA.hy926 cells. Eur J Pharmacol. (2016) 770:9–15. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.11.040

48.

Zhang X Liu MH Qiao L Zhang XY Liu XL Dong M et al Ginsenoside Rb1 enhances atherosclerotic plaque stability by skewing macrophages to the M2 phenotype. J Cell Mol Med. (2018) 22(1):409–16. 10.1111/jcmm.13329

49.

Xue Y Wei Z Ding H Wang Q Zhou Z Zheng S et al MicroRNA-19b/221/222 induces endothelial cell dysfunction via suppression of PGC-1α in the progression of atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. (2015) 241(2):671681. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.06.031

50.

Li H Jiao Y Xie M . Paeoniflorin ameliorates atherosclerosis by suppressing TLR4-mediated NF-κB activation. Inflammation. (2017) 40(6):2042–51. 10.1007/s10753-017-0644-z

51.

Zhu L Gong X Gong J Xuan Y Fu T Ni S et al Notoginsenoside R1 upregulates miR-221–3p expression to alleviate ox-LDL-induced apoptosis, inflammation, and oxidative stress by inhibiting the TLR4/NF-κB pathway in HUVECs. Braz J Med Biol Res. (2020) 53(6):e9346. 10.1590/1414-431x20209346

52.

Hoefen RJ Berk BC . The role of MAP kinases in endothelial activation. Vasc Pharmacol. (2002) 38(5):271–3. 10.1016/s1537-1891(02)00251-3

53.

Zhang F Kent KC Yamanouchi D Zhang Y Kato K Tsai S et al Anti-receptor for advanced glycation end products therapies as novel treatment for abdominal aortic aneurysm. Ann Surg. (2009) 250(3):416–23. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b41a18

54.

Dou L Lu Y Shen T Huang X Man Y Wang S et al Panax notogingseng saponins suppress RAGE/MAPK signaling and NF-kappaB activation in apolipoprotein-E-deficient atherosclerosis-prone mice. Cell Physiol Biochem. (2012) 29(5-6):875–82. 10.1159/000315061

55.

Wang HH Garruti G Liu M Portincasa P Wang DQ . Cholesterol and lipoprotein metabolism and atherosclerosis: recent advances in reverse cholesterol transport. Ann Hepatol. (2017) 16(Suppl. 1: s3-105):s27–42. 10.5604/01.3001.0010.5495

56.

Cui Y Liu J Huang C Zhao B . Moxibustion at CV4 alleviates atherosclerotic lesions through activation of the LXRα/ABCA1 pathway in apolipoprotein-E-deficient mice. Acupunct Med. (2019) 37(4):237–43. 10.1136/acupmed-2016-011317

57.

van der Vorst EPC Theodorou K Wu Y Hoeksema MA Goossens P Bursill CA et al High-density lipoproteins exert pro-inflammatory effects on macrophages via passive cholesterol depletion and PKC-NF-κB/STAT1-IRF1 signaling. Cell Metab. (2017) 25(1):197–207. 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.10.013

58.

Yang H Liu Z Hu X Liu X Gui L Cai Z et al Protective effect of Panax Notoginseng saponins on apolipoprotein-E-deficient atherosclerosis-prone mice. Curr Pharm Des. (2022) 28(8):671–7. 10.2174/1381612828666220128104636

59.

Liu G Wang B Zhang J Jiang H Liu F . Total panax notoginsenosides prevent atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-knockout mice: role of downregulation of CD40 and MMP-9 expression. J Ethnopharmacol. (2009) 126(2):350–4. 10.1016/j.jep.2009.08.014

60.

Lagace TA . PCSK9 And LDLR degradation: regulatory mechanisms in circulation and in cells. Curr Opin Lipidol. (2014) 25(5):387–93. 10.1097/MOL.0000000000000114

61.

Seidah NG Abifadel M Prost S Boileau C Prat A . The proprotein convertases in hypercholesterolemia and cardiovascular diseases: emphasis on proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin 9. Pharmacol Rev. (2017) 69(1):33–52. 10.1124/pr.116.012989

62.

Huang YW Zhang M Wang LT Nie Y Yang JB Meng WL et al 20(S)-Protopanaxadiol decreases atherosclerosis in ApoE KO mice by increasing the levels of LDLR and inhibiting its binding with PCSK9. Food Funct. (2022) 13:13. 10.1039/d2fo00392a

63.

Webb NR Moore KJ . Macrophage-derived foam cells in atherosclerosis: lessons from murine models and implications for therapy. Curr Drug Targets. (2007) 8(12):1249–63. 10.2174/138945007783220597

64.

Kruth HS . Macrophage foam cells and atherosclerosis. Front Biosci. (2001) 6(1):D429–55. 10.2741/Kruth

65.

Wang Y Chen Z Liao Y Mei C Peng H Wang M et al Angiotensin II increases the cholesterol content of foam cells via down-regulating the expression of ATP-binding cassette transporter A1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. (2007) 353(3):650–4. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.12.067

66.

Jia Y Li ZY Zhang HG Li HB Liu Y Li XH . Panax notoginseng saponins decrease cholesterol ester via up-regulating ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 in foam cells. J Ethnopharmacol. (2010) 132(1):297–302. 10.1016/j.jep.2010.08.033

67.

Calkin AC Tontonoz P . Liver x receptor signaling pathways and atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. (2010) 30(8):1513–8. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.191197

68.

Li H Shang Z Shen A Huang X Lu A Zhang Z et al Panax notoginseng saponin mitigates glycolysis to regulate macrophage polarization and sphingolipid metabolism via hypoxia-inducible factor-1 to alleviate atherosclerosis. Phytomedicine. (2025) 149:157506. 10.1016/j.phymed.2025.157506

69.

Kattoor AJ Pothineni NVK Palagiri D Mehta JL . Oxidative stress in atherosclerosis. Curr Atheroscler Rep. (2017) 19(11):42. 10.1007/s11883-017-0678-6

70.

Batty M Bennett MR Yu E . The role of oxidative stress in atherosclerosis. Cells. (2022) 11(23):3843. 10.3390/cells11233843

71.

Khatana C Saini NK Chakrabarti S Saini V Sharma A Saini RV et al Mechanistic insights into the oxidized low-density lipoprotein-induced atherosclerosis. Oxid Med Cell Longevity. (2020) 2020:5245308. 10.3390/cells11233843

72.

Tousoulis D Psaltopoulou T Androulakis E Papageorgiou N Papaioannou S Oikonomou E et al Oxidative stress and early atherosclerosis: novel antioxidant treatment. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. (2015) 29(1):75–88. 10.1007/s10557-014-6562-5

73.

Pang C Zheng Z Shi L Sheng Y Wei H Wang Z et al Caffeic acid prevents Acetaminophen-induced liver injury by activating the Keap1-Nrf2 antioxidative defense system. Free Radical Biol Med. (2016) 91:236–46. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.12.024

74.

Mi W Yu M Yin S Ji Y Shi T Li N . Analysis of the renal protection and antioxidative stress effects of Panax notoginseng saponins in diabetic nephropathy mice. J Immunol Res. (2022) 2022:3610935. 10.1155/2022/3610935

75.

Zhang B Zhang X Zhang C Shen Q Sun G Sun X . Notoginsenoside R1 protects db/db mice against diabetic nephropathy via upregulation of Nrf2-mediated HO-1 expression. Molecules (Basel). (2019) 24(2):247. 10.3390/molecules24020247

76.

Hu S Wu Y Zhao B Hu H Zhu B Sun Z et al Panax notoginseng saponins protect cerebral microvascular endothelial cells against oxygen-glucose deprivation/reperfusion-induced barrier dysfunction via activation of PI3K/akt/Nrf2 antioxidant signaling pathway. Molecules (Basel). (2018) 23(11):2781. 10.3390/molecules23112781

77.

Hu S Liu T Wu Y Yang W Hu S Sun Z et al Panax notoginseng saponins suppress lipopolysaccharide-induced barrier disruption and monocyte adhesion on bEnd.3 cells via the opposite modulation of Nrf2 antioxidant and NF-κB inflammatory pathways. Phytother Res. (2019) 33(12):3163–76. 10.1002/ptr.6488

78.

Zheng Z Wang M Cheng C Liu D Wu L Zhu J et al Ginsenoside Rb1 reduces H2O2 induced HUVEC dysfunction by stimulating the sirtuin 1/AMP activated protein kinase pathway. Mol Med Rep. (2020) 22(1):247–56. 10.3892/mmr.2020.11096

79.

Fan J Liu D He C Li X He F . Inhibiting adhesion events by Panax notoginseng saponins and ginsenoside Rb1 protecting arteries via activation of Nrf2 and suppression of p38—vCAM-1 signal pathway. J Ethnopharmacol. (2016) 192:423–30. 10.1016/j.jep.2016.09.022

80.

Durham AL Speer MY Scatena M Giachelli CM Shanahan CM . Role of smooth muscle cells in vascular calcification: implications in atherosclerosis and arterial stiffness. Cardiovasc Res. (2018) 114(4):590–600. 10.1093/cvr/cvy010

81.

Zhang W Chen G Deng CQ . Effects and mechanisms of total Panax notoginseng saponins on proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells with plasma pharmacology method. J Pharm Pharmacol. (2012) 64(1):139–45. 10.1111/j.2042-7158.2011.01379.x

82.

Ding Q Chai H Mahmood N Tsao J Mochly-Rosen D Zhou W . Matrix metalloproteinases modulated by protein kinase cε mediate resistin-induced migration of human coronary artery smooth muscle cells. J Vasc Surg. (2011) 53(4):1044–51. 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.10.117

83.

Calabro P Samudio I Willerson JT Yeh ET . Resistin promotes smooth muscle cell proliferation through activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathways. Circulation. (2004) 110(21):3335–40. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000147825.97879.E7

84.

Han J Tan C Pan Y Qu C Wang Z Wang S et al Andrographolide inhibits the proliferation and migration of vascular smooth muscle cells via PI3K/AKT signaling pathway and amino acid metabolism to prevent intimal hyperplasia. Eur J Pharmacol. (2023) 959:176082. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2023.176082

85.

Lu W Lin Y Haider N Moly P Wang L Zhou W . Ginsenoside Rb1 protects human vascular smooth muscle cells against resistin-induced oxidative stress and dysfunction. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2023) 10:1164547. 10.3389/fcvm.2023.1164547

86.

Fang H Yang S Luo Y Zhang C Rao Y Liu R et al Notoginsenoside R1 inhibits vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation, migration and neointimal hyperplasia through PI3K/akt signaling. Sci Rep. (2018) 8(1):7595. 10.1038/s41598-018-25874-y

87.

Sedding DG Boyle EC Demandt JAF Sluimer JC Dutzmann J Haverich A et al Vasa vasorum angiogenesis: key player in the initiation and progression of atherosclerosis and potential target for the treatment of cardiovascular disease. Front Immunol. (2018) 9:706. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00706

88.

Melincovici CS Boşca AB Şuşman S Mărginean M Mihu C Istrate M et al Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)—key factor in normal and pathological angiogenesis. Roman J Morphol Embryol. (2018) 59(2):455–67.

89.

Siemerink MJ Hughes MR Dallinga MG Gora T Cait J Vogels IM et al CD34 promotes pathological epi-retinal neovascularization in a mouse model of oxygen-induced retinopathy. PLoS One. (2016) 11(6):e0157902. 10.1371/journal.pone.0157902

90.

Qiao Y Zhang PJ Lu XT Sun WW Liu GL Ren M et al Panax notoginseng saponins inhibits atherosclerotic plaque angiogenesis by down-regulating vascular endothelial growth factor and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase subunit 4 expression. Chin J Integr Med. (2015) 21(4):259–65. 10.1007/s11655-014-1832-4

91.

Chen SW Li XH Ye KH Jiang ZF Ren XD . Total saponins of Panax notoginseng protected rabbit iliac artery against balloon endothelial denudation injury. Acta Pharmacol Sin. (2004) 25(9):1151–6.

92.

Rychli K Huber K Wojta J . Pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) as a therapeutic target in cardiovascular disease. Expert Opin Ther Targets. (2009) 13(11):1295–302. 10.1517/14728220903241641

93.

Lu H Zhou X Kwok HH Dong M Liu Z Poon PY et al Ginsenoside-Rb1-mediated anti-angiogenesis via regulating PEDF and miR-33a through the activation of PPAR-γ pathway. Front Pharmacol. (2017) 8:783. 10.3389/fphar.2017.00783

94.

Poznyak AV Nikiforov NG Wu WK Kirichenko TV Orekhov AN . Autophagy and mitophagy as essential components of atherosclerosis. Cells. (2021) 10(2):443. 10.3390/cells10020443

95.

Mizushima N Komatsu M . Autophagy: renovation of cells and tissues. Cell. (2011) 147(4):728–41. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.026

96.

Zhou P Xie W Luo Y Lu S Dai Z Wang R et al Inhibitory effects of ginsenoside Rb1 on early atherosclerosis in ApoE-/- mice via inhibition of apoptosis and enhancing autophagy. Molecules (Basel). (2018) 23(11):2912. 10.3390/molecules23112912

97.

Parzych KR Klionsky DJ . An overview of autophagy: morphology, mechanism, and regulation. Antioxid Redox Signaling. (2014) 20(3):460–73. 10.1089/ars.2013.5371

98.

Qiao L Zhang X Liu M Liu X Dong M Cheng J et al Ginsenoside Rb1 enhances atherosclerotic plaque stability by improving autophagy and lipid metabolism in macrophage foam cells. Front Pharmacol. (2017) 8:727. 10.3389/fphar.2017.00727

99.

Ou H Liu C Feng W Xiao X Tang S Mo Z . Role of AMPK in atherosclerosis via autophagy regulation. Sci China Life Sci. (2018) 61(10):1212–21. 10.1007/s11427-017-9240-2

100.

Tao W Yurdagul A Jr Kong N Li W Wang X Doran AC et al siRNA nanoparticles targeting CaMKIIγ in lesional macrophages improve atherosclerotic plaque stability in mice. Sci Transl Med. (2020) 12(553):eaay1063. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aay1063

101.

Wang D Lv L Xu Y Jiang K Chen F Qian J et al Cardioprotection of Panax Notoginseng saponins against acute myocardial infarction and heart failure through inducing autophagy. Biomed Pharmacother. (2021) 136:111287. 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111287

102.

Yang P Ling L Sun W Yang J Zhang L Chang G et al Ginsenoside Rg1 inhibits apoptosis by increasing autophagy via the AMPK/mTOR signaling in serum deprivation macrophages. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai). (2018) 50(2):144–55. 10.1093/abbs/gmx136

103.

Duan M Chen H Yin L Zhu X Novák P Lv Y et al Mitochondrial apolipoprotein A-I binding protein alleviates atherosclerosis by regulating mitophagy and macrophage polarization. Cell Commun Signaling. (2022) 20(1):60. 10.1186/s12964-022-00858-8

104.

Chen J Li L Bai X Xiao L Shangguan J Zhang W et al Inhibition of autophagy prevents Panax Notoginseng saponins (PNS) protection on cardiac myocytes against endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress-induced mitochondrial injury, Ca2+ homeostasis and associated apoptosis. Front Pharmacol. (2021) 12:620812. 10.3389/fphar.2021.620812

105.

Zhang Y Liu D Hu H Zhang P Xie R Cui W . HIF-1α/BNIP3 signaling pathway-induced-autophagy plays protective role during myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Biomed Pharmacother. (2019) 120:109464. 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109464

106.

Liu XW Lu MK Zhong HT Wang LH Fu YP . Panax Notoginseng saponins attenuate myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury through the HIF-1α/BNIP3 pathway of autophagy. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. (2019) 73(2):92–9. 10.1097/FJC.0000000000000640

Summary

Keywords

anti-inflammation, anti-oxidant stress, atherosclerosis, panax notoginseng, panax notoginseng saponin, pharmacological effect

Citation

Xiong L, Liu D, Cheng J and Yin T (2026) Research progress on the mechanism of panax notoginseng saponin in the treatment of atherosclerosis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 13:1659763. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2026.1659763

Received

04 July 2025

Revised

07 January 2026

Accepted

12 January 2026

Published

05 February 2026

Volume

13 - 2026

Edited by

Desh Deepak Singh, Amity University Jaipur, India

Reviewed by

Jelica Grujic-Milanovic, University of Belgrade, Serbia

Priyanka Kothari, Amity University Rajasthan, India

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Xiong, Liu, Cheng and Yin.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Long Xiong x1591251@163.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.