Abstract

Background:

Patients with heart valve disease (VHD) combined with pulmonary hypertension (PH) have a higher risk for hospital-acquired pneumonia. We aimed to analyze the risk factors and construct a valid nomogram model for predicting hospital-acquired pneumonia among those patients.

Methods:

Patients with VHD combined with PH who underwent heart valve replacement were collected. The perioperative risk factors for hospital-acquired pneumonia were analyzed by univariable and logistic regression, and then a nomogram prediction model was constructed and validated.

Results:

A total of 377 patients were included, and 81 cases developed postoperative hospital-acquired pneumonia, with an incidence of 21.49%. The results of multifactorial analysis showed that preoperative anemia, ASA score >grade III, duration of surgery ≥313 min, duration of endotracheal intubation ≥3 d, duration of indwelling gastric tube ≥1 d, and bioprosthetic valve usage were the risk factors for the occurrence of postoperative hospital-acquired pneumonia (P < 0.05). The model validation results showed that patients judged to be at high risk of hospital-acquired pneumonia are consistent with the actual situation, indicating that the model has good predictive efficacy.

Conclusions:

The constructed six-variable nomogram prediction model has satisfying efficacy in predicting hospital-acquired pneumonia after valve replacement in patients with VHD combined with PH. It is significant for early identification and future quality improvement to reduce the risk of hospital-acquired pneumonia.

Background

Valvular heart disease (VHD) is a common heart disease worldwide. Previous surveys showed regional variations in the prevalence of VHD, with 2.5% in the United States, 11.3% in the United Kingdom, and 9.65% in the Chinese population (1, 2). The causes of VHD are complex, and the prolonged duration of the disease severely impairs patients' physical function and their quality of life (3). As the disease progresses, patients may also develop cardiac insufficiency and hemodynamic changes (4). Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is a common comorbidity of VHD, and its occurrence is closely related to valvular disease and heart failure (5–7). The study showed that 32.4% of patients with heart disease had comorbid PH (8). Combined PH exacerbates the impairment of cardiopulmonary function in patients with VHD, leading to a poor prognosis and raising the risk of death (9, 10).

Currently, the primary clinical treatment for VHD patients is heart valve replacement surgery (11, 12). Valve replacement is a complex cardiac procedure with a high risk of postoperative hospital-acquired pneumonia (13). Hospital-acquired pneumonia can further exacerbate patients' postoperative cardiopulmonary burden, leading to poor prognosis and even death (14). Previous studies have shown that the incidence of hospital-acquired pneumonia after valve replacement ranged from 11.4% to 33.33% (13, 15–18). Various risk factors contribute to its occurrence. It has been reported that PH is an independent risk factor for the development of postoperative hospital-acquired pneumonia, which indicates that patients with VHD combined with PH are at high risk of developing hospital-acquired pneumonia after valve replacement (16). Furthermore, studies indicated that postoperative pneumonia was significantly associated with perioperative factors such as the duration of surgery, blood cell transfusion, etc. (17).

The nomogram model is based on the regression model, which can integrate various risk factors, using graphical and visualization methods. It is suitable for individualized prediction of the probability of postoperative hospital-acquired pneumonia in patients with high clinical utility (19). Few studies have analyzed the risk factors and constructed nomogram models for predicting hospital-acquired pneumonia after valve replacement among patients with VHD combined with PH. For example, a previous study evaluated the predictive value of procalcitonin in ventilator-associated pneumonia after cardiac valve replacement but did not construct a prediction model (20). Therefore, this study will fill the research gap. The hypotheses are that a) the significant perioperative risk factors for hospital-acquired pneumonia after valve replacement in patients with VHD combined with PH can be identified; b) the constructed nomogram model has good validity for predicting hospital-acquired pneumonia.

Methods

Participants

The clinical data of 377 patients with VHD complicated by PH who were treated at a tertiary general hospital in Shandong Province from January 2022 to December 2023 were retrospectively collected. Inclusion criteria: (1) age ≥18 years old; (2) those who were diagnosed with heart valve disease combined with pulmonary hypertension, which was measured by transthoracic echocardiography (defined as pulmonary artery pressure plus central venous pressure >60 mm Hg) before the operation, and met the diagnostic criteria of the Chinese Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension (2021 edition) (21); (3) those who underwent cardiac valve replacement treatment; (4) those who had complete medical records. Exclusion criteria: (1) people with congenital heart disease combined with pulmonary hypertension; (2) people with a postoperative combination of infections in other parts of the body; (3) people with other severe organic lesions, hearing, and mental disorders; (4) people with preoperative pulmonary infection.

Data collection

The clinical data of participants were obtained from the hospital information system, laboratory information system, and the hospital infection surveillance system, including demographic, diagnostic, treatment data, and surgical information. The physicians and infection management experts reviewed all the infected cases and entered into the hospital infection surveillance system. Diagnostic specialists were blinded to other patients' data. The hospital-acquired pneumonia was diagnosed based on criteria by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The study was approved by the hospital ethics committee (KYLL-2020-149). The need for patients informed written consent was waived by the hospital ethics committee.

Statistical analysis

SPSS 22.0 and R 4.1.3 software were used for data analysis and nomogram model construction. Variables with normal distribution were expressed as mean ± standard deviation, and the t-test was used for intergroup comparison; the count data was expressed as rate or percentage, and the χ2-test was used for intergroup comparison; some continuous variables, including preoperative length of stay, duration of surgery, duration of the aortic block, duration of extracorporeal circulation, etc. were transformed into dichotomous variables according to the best cut-off value which was determined through Youden index in ROC curve analysis. The variables with statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) after univariate analyses were included in the multifactorial logistic regression analysis (forward-LR method). Independent risk factors for postoperative hospital-acquired pneumonia were analyzed based on the screened independent risk factors, and a nomogram model was drawn using R software and its related program package. The Bootstrap method (repeated sampling 1,000 times) was adopted to validate the model internally. The calibration curves, the (corrected) C-index, the Hosmer-Lemeshow test, the clinical decision curve, and the clinical impact curve were used to assess the predictive efficacy of the model. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Results

Postoperative hospital-acquired pneumonia in patients with VHD combined with PH

Among 377 patients with VHD combined with PH receiving heart valve replacement surgery, there were 172 male and 205 female patients, with an average age of 57.21 ± 10.43 years, and a total of 81 patients developed postoperative hospital-acquired pneumonia, with an incidence of 21.49%.

Univariate analysis of clinical data of patients with VHD combined with PH

Age, preoperative anemia, heart failure, valve material, preoperative hospital stay, left ventricular ejection fraction, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score, duration of operation, duration of aortic block, postoperative intensive care unit (ICU) stay, days of endotracheal intubation, days of non-invasive mechanical ventilation, days of central venous catheterization, days of indwelling gastric tube, duration of extracorporeal circulation, postoperative low cardiac output syndrome were statistically significant (P < 0.05) between groups, and the differences in New York Heart Association (NYHA) cardiac function classification, intraoperative blood transfusion, and body mass index between the two groups were not statistically significant, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1

| Variables | Infected group | Uninfected group | F | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 81) | (n = 296) | ||||

| Gender | Male | 33 | 139 | 0.991 | 0.319 |

| Female | 48 | 157 | |||

| Age | 60.04 ± 10.17 | 56.44 ± 10.38 | −2.778 | 0.006a | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.30 ± 4.14 | 24.04 ± 3.67 | 1.571 | 0.117 | |

| Smoking | Yes | 11 | 66 | 2.973 | 0.085 |

| No | 70 | 230 | |||

| Alcohol usage | Yes | 12 | 62 | 1.515 | 0.218 |

| No | 69 | 234 | |||

| Hypertension | Yes | 21 | 81 | 0.067 | 0.796 |

| No | 60 | 215 | |||

| Diabetes | Yes | 7 | 22 | 0.131 | 0.717 |

| No | 74 | 274 | |||

| Preoperative LOS (d) | <8 | 33 | 162 | 4.984 | 0.026a |

| ≥8 | 48 | 134 | |||

| Preoperative anemia | Yes | 18 | 23 | 13.704 | <0.001a |

| No | 63 | 273 | |||

| NYHA | I–II | 17 | 85 | 1.925 | 0.165 |

| III–IV | 64 | 211 | |||

| Heart failure | Yes | 20 | 43 | 4.721 | 0.030a |

| No | 61 | 253 | |||

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (%) | <50 | 17 | 34 | 4.908 | 0.027a |

| ≥50 | 64 | 262 | |||

| ASA score | ≤III | 57 | 262 | 16.081 | <0.001a |

| >III | 24 | 34 | |||

| Open surgery | Yes | 81 | 289 | 0.870 | 0.351 |

| No | 0 | 7 | |||

| Duration of surgery (min) | <313 | 35 | 204 | 18.114 | <0.001a |

| ≥313 | 46 | 92 | |||

| Valve Materials | Mechanical valves | 43 | 215 | 11.251 | 0.001a |

| Biological valves | 38 | 81 | |||

| Intraoperative blood transfusion | Yes | 77 | 275 | 0.478 | 0.490 |

| No | 4 | 21 | |||

| Duration of Aortic block (min) | <145 | 56 | 247 | 8.255 | 0.004a |

| ≥145 | 25 | 49 | |||

| Duration of Extracorporeal circulation (min) | <209 | 54 | 253 | 14.876 | <0.001a |

| ≥209 | 27 | 43 | |||

| LOS in ICU (d) | <6 | 33 | 215 | 28.741 | <0.001a |

| ≥6 | 48 | 81 | |||

| Number of days of tracheal intubation (d) | <3 | 49 | 280 | 66.559 | <0.001a |

| ≥3 | 32 | 16 | |||

| Days of non-invasive mechanical ventilation (d) | <1 | 68 | 286 | 15.681 | <0.001a |

| ≥1 | 13 | 10 | |||

| Days of central venous catheterization (d) | <11 | 39 | 210 | 14.740 | <0.001a |

| ≥11 | 42 | 86 | |||

| Number of days of indwelling gastric tube (d) | <1 | 57 | 289 | 62.645 | <0.001a |

| ≥1 | 24 | 7 | |||

| Postoperative low cardiac output syndrome | Yes | 14 | 5 | 29.141 | <0.001a |

| No | 67 | 291 | |||

Univariate analysis of clinical data of patients with VHD combined with PH.

represents P < 0.05.

BMI, body mass index; ICU, intensive care unit; NYHA, New York Heart Association; LOS, length of stay; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists.

The 16 variables showing statistical significance on univariate analysis were included as independent variables in multifactorial logistic regression (forward-LR method) analysis. The results showed that preoperative anemia, ASA score >grade III, operative time ≥313 mins, and days of tracheal intubation ≥3d, days of bioprosthetic valve and indwelling gastric tube ≥1d were independent risk factors for postoperative hospital-acquired pneumonia in patients with VHD combined with PH (P < 0.05), as shown in Table 2.

Table 2

| Variables | β | standard error | Wald χ² | P value | OR | 95%CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative anemia | 0.860 | 0.412 | 4.359 | 0.037a | 2.363 | 1.054–5.297 |

| ASA score >III | 0.777 | 0.355 | 4.778 | 0.029a | 2.174 | 1.084–4.362 |

| Duration of surgery ≥313 min | 0.659 | 0.302 | 4.776 | 0.029a | 1.933 | 1.070–3.491 |

| Biological valves | 0.862 | 0.301 | 8.224 | 0.004a | 2.369 | 1.314–4.270 |

| Number of days of indwelling gastric tube ≥1 d | 1.768 | 0.561 | 9.922 | 0.002a | 5.860 | 1.950–17.610 |

| Number of days of tracheal intubation ≥3 d | 1.211 | 0.438 | 7.653 | 0.006a | 3.358 | 1.424–7.922 |

Multifactor logistic regression of postoperative hospital-acquired pneumonia in patients with VHD combined with PH.

represents P < 0.05.

ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% Confidence interval.

Construction and validation of a nomogram model for the risk of postoperative hospital-acquired pneumonia in patients with VHD combined with PH

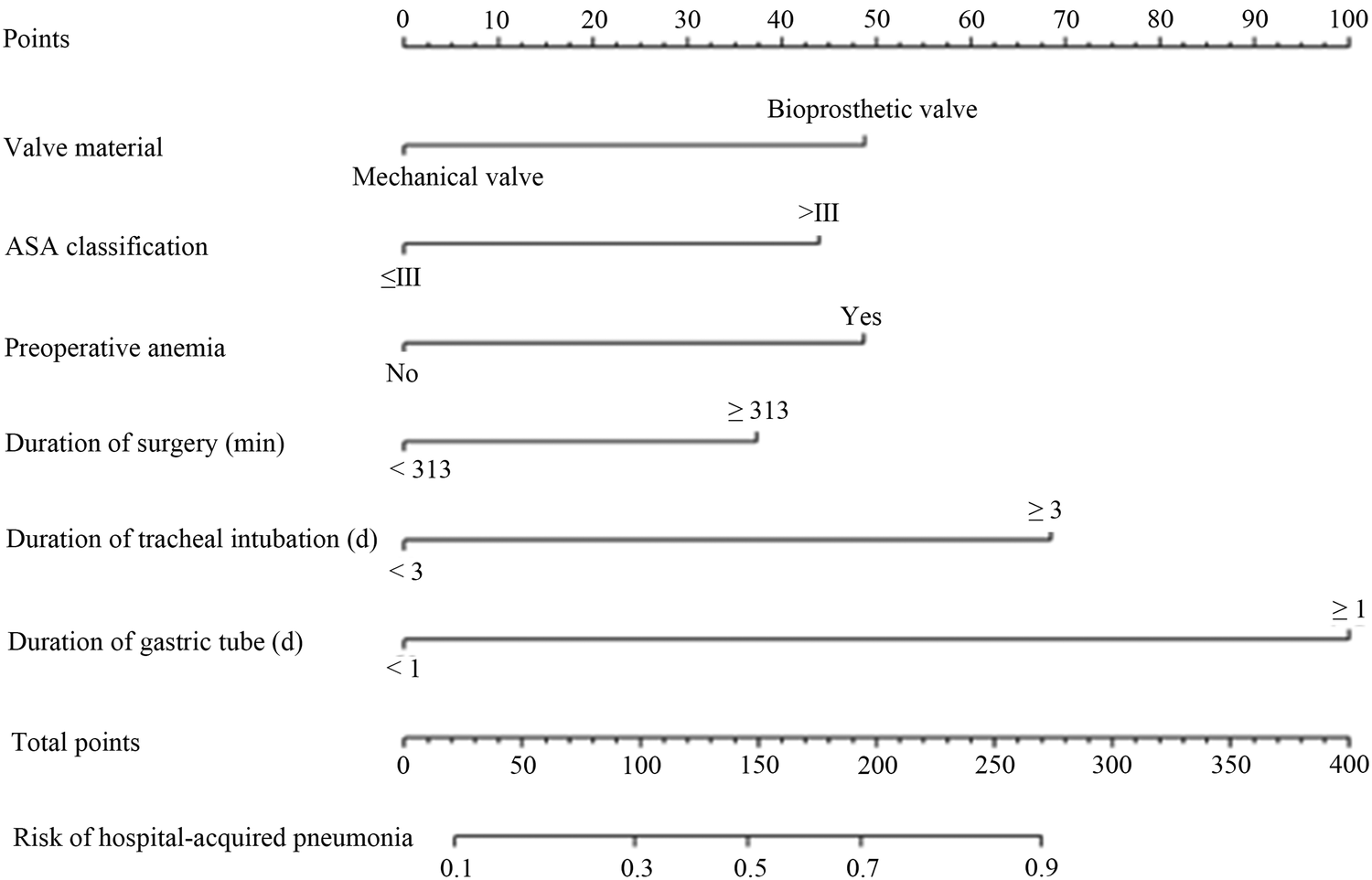

Based on the six independent risk factors obtained from the above regression analysis, a nomogram model for the risk of postoperative hospital-acquired pneumonia in patients with VHD combined with PH was drawn, as seen in Figure 1. The method of applying the nomogram was as follows: the six scores of valve materials, the ASA score, the preoperative anemia, the duration of the operation, the number of days of tracheal intubation, and the number of days of the gastric tube in place were summed to a total score, which represents different risks of infections. For example, a patient received a bioprosthetic valve, had an ASA score ≤ Grade III, presented with anemia preoperatively, underwent surgery lasting <313 min, required endotracheal intubation for <3 days, and had a nasogastric tube in place for <1 day. The six-item scores were 50 points, 0 points, 50 points, 0 points, and 0 points, resulting in a total score of 100 points. The corresponding hospital-acquired pneumonia risk probability on the total score axis is 30%.

Figure 1

A nomogram predicting the risk of hospital-acquired pneumonia after valve replacement in patients with VHD combined with PH. Each variable's value was given a score on the point scale axis. A total core could be easily calculated by adding each single score, and by projecting the total score to the lower total point scale, we could estimate the probability of hospital-acquired pneumonia.

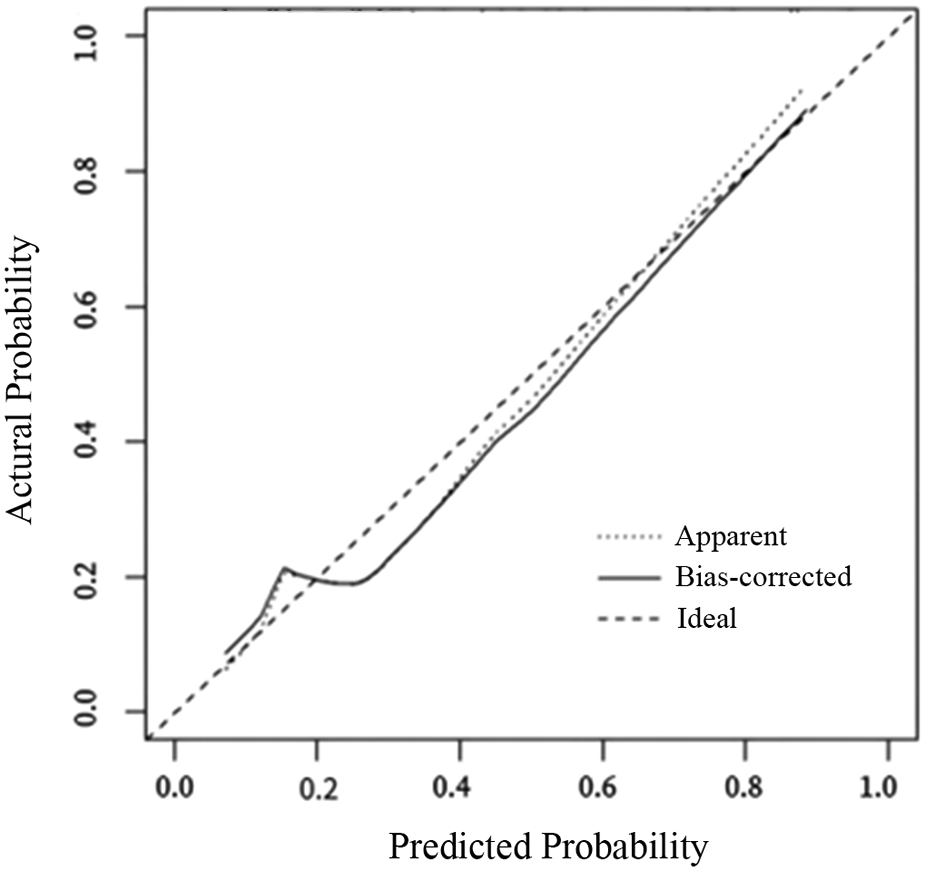

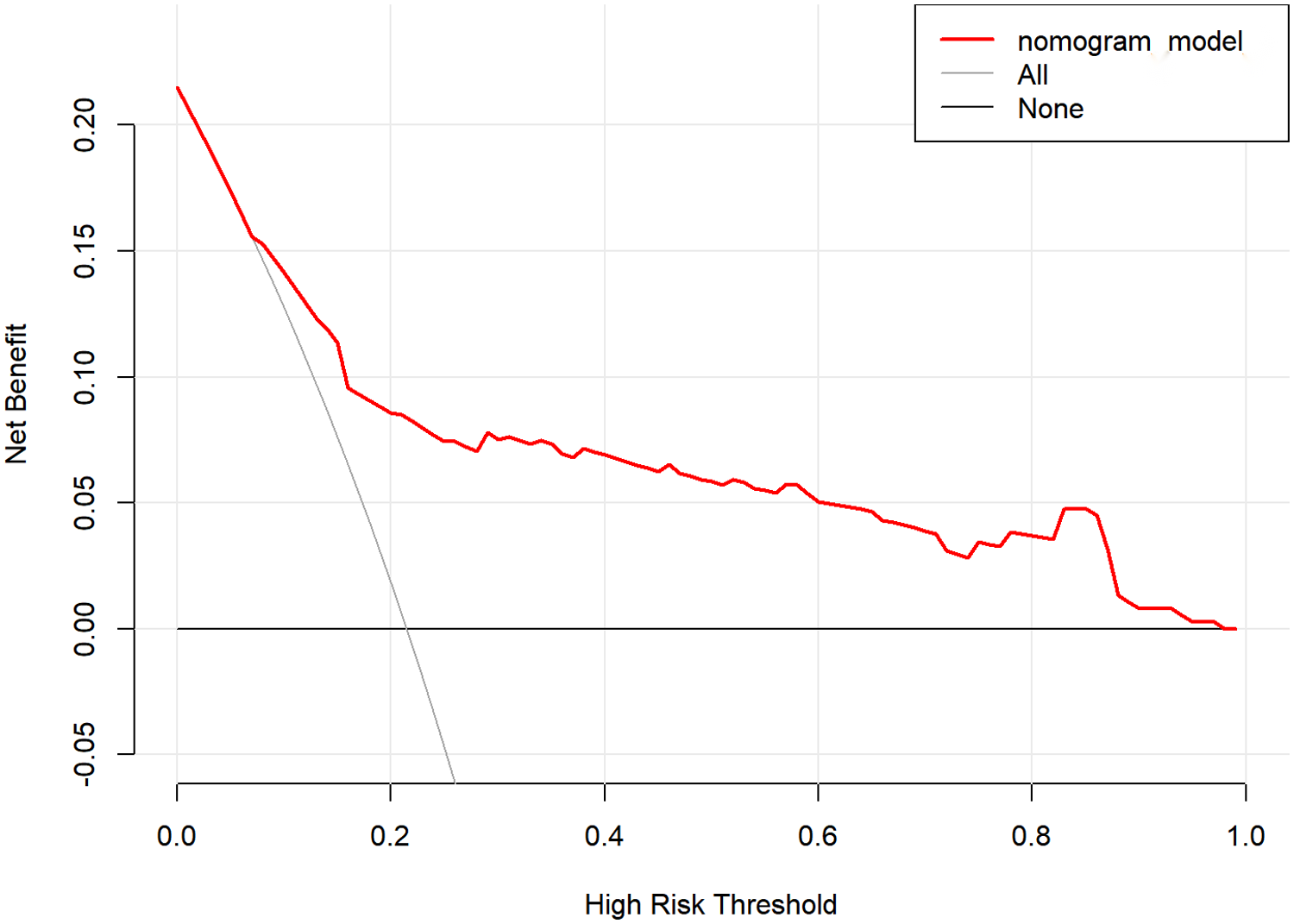

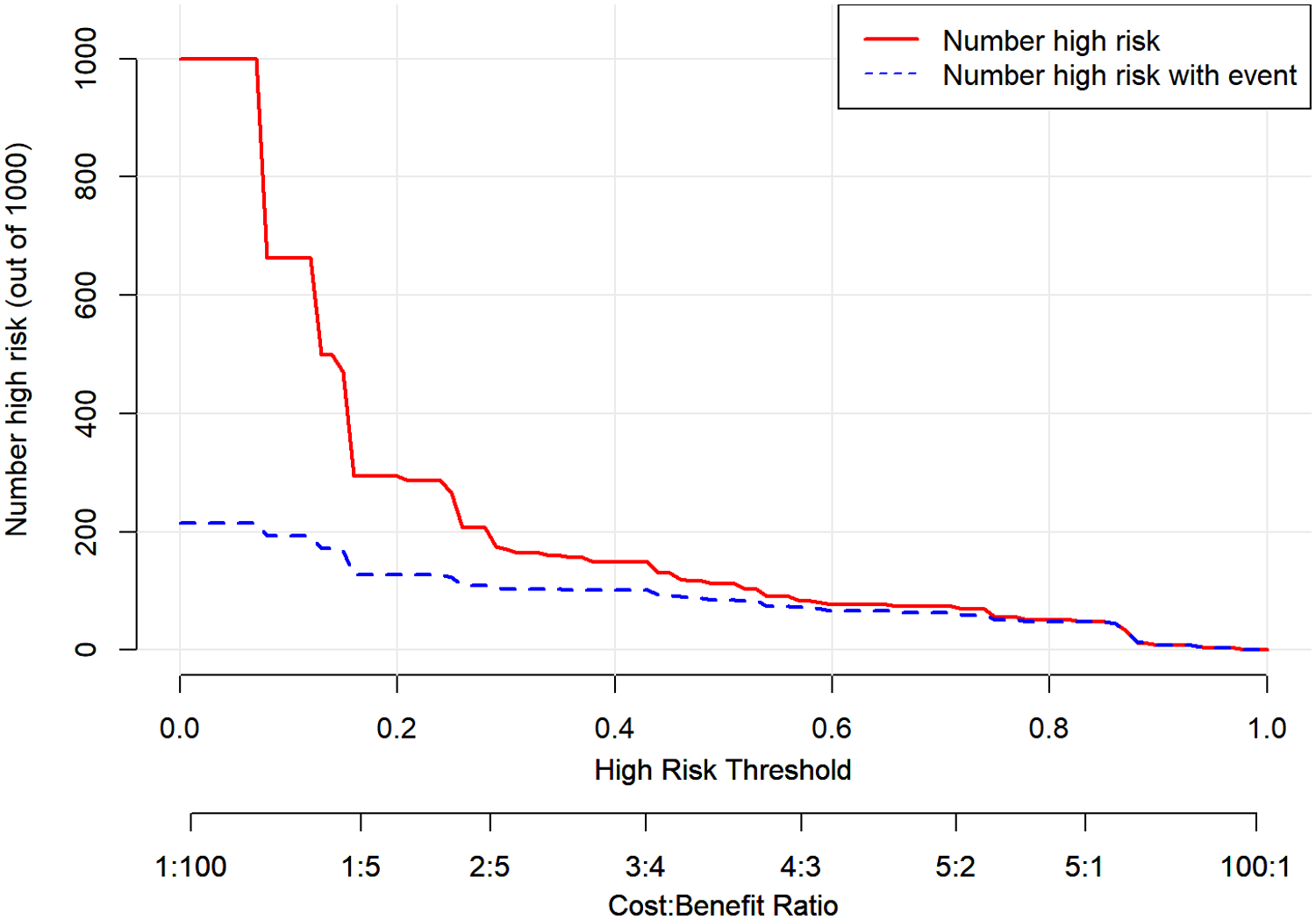

The internal validation results of the model showed that the C-index was 0.782 (95% CI: 0.723–0.841), and the corrected C-index was 0.770; the Hosmer-Lemeshow test was P = 0.511; the calibrated curves of the nomogram model were close to the ideal curves, which indicated that the model had a reasonable degree of accuracy, as seen in Figure 2. The clinical decision curve showed that the model had a high net benefit value in the range of 10%–95%, with good clinical validity, see Figure 3. The clinical impact curve showed that when the threshold probability was greater than 0.5, the number of people judged by the model to be at high risk of postoperative hospital-acquired pneumonia was highly matched to the number of people who developed postoperative hospital-acquired pneumonia, with a high clinical validity rate, see Figure 4.

Figure 2

The calibration curves for the nomogram. The x-axis represents the nomogram-predicted probability, and the y-axis represents the actual probability of hospital-acquired pneumonia. A perfect prediction would correspond to the 45 ° dashed line. The dotted line represents the entire cohort (n = 377), and the solid line is bias-corrected by bootstrapping (B = 1,000 repetitions), indicating observed nomogram performance.

Figure 3

Decision curve of the nomogram model.

Figure 4

Clinical impact curve of the nomogram model.

Discussion

The present study identified six independent perioperative risk factors for postoperative hospital-acquired pneumonia in patients with VHD combined with PH. The nomogram model has good internal validation and significant clinical value in that it can help to identify high-risk patients during the early postoperative period. This study added clinical evidence and theoretical value to the occurrence of hospital-acquired pneumonia in patients with VHD combined with PH.

Valve replacement is the primary treatment method for patients with VHD combined with PH, which is a complex and invasive procedure with a high risk of postoperative hospital-acquired pneumonia. PH can cause lung injury in patients, which further increases the risk of postoperative hospital-acquired pneumonia in patients (22). The results of this study showed that 81 out of 377 surgical patients had postoperative hospital-acquired pneumonia, with an incidence of 21.49%, which was much higher than the 13.15% reported by Wei Runsheng et al. (15) but lower than the 33.3% reported by Zhao Ying et al. (18) This may be related to the differences in the population included in the study. Postoperative hospital-acquired pneumonia not only affects patients' lung function and increases postoperative cardiopulmonary burden but also increases treatment difficulties and risk of death (15). Therefore, it is important to construct a nomogram model for the risk of postoperative hospital-acquired pneumonia in patients with VHD combined with PH for early identification of high-risk patients.

The results of this study showed that ASA score >grade III, operative time ≥313 min, preoperative anemia, bioprosthetic valves, days of tracheal intubation ≥3d, and days of indwelling gastric tube ≥1d were the independent risk factors for postoperative hospital-acquired pneumonia after valve replacement surgery in patients with VHD combined with PH. A study reported by Morikane and other scholars showed that high ASA scores were strongly associated with postoperative infections after cardiac surgery, which is in line with the present study (23). The higher the ASA score grading, the poorer the patient's preoperative physical status and the higher the surgical and anesthetic risk. Patients with high ASA scores usually had poor surgical tolerance and higher risks of postoperative infections. The ASA score has been verified to have a good predictive effect on perioperative morbidity and mortality (24). Previous studies have shown that the duration of surgery is an independent risk factor for hospital-acquired infections in heart valve replacement, which is in line with the present study (16, 17). The risk of postoperative hospital-acquired pneumonia was higher in patients with a duration of surgery of ≥313 mins, and the reasons for this may be related to the long duration of surgery resulting in the prolonged exposure of the patient's organism to the external environment and increased exposure to infectious pathogens. A large number of studies reported that preoperative anemia was closely associated with adverse outcomes such as infection after cardiac surgery, supporting its inclusion as a predictive variable in risk prediction models (25–27). The reason may be related to the fact that preoperative anemia increases the intraoperative transfusion rate and the risk of postoperative complications, leading to an increased risk of postoperative infection in patients.

This study found that valve material was strongly associated with postoperative hospital-acquired pneumonia. Using bioprosthetic valves was an independent risk factor for postoperative hospital-acquired pneumonia in patients with VHD combined with PH. The previous studies showed that the incidence of adverse events such as postoperative endocarditis and reoperation was higher in patients with bioprosthetic valves than with mechanical valves (28, 29). Therefore, valve materials should be selected based on the patient's actual situation in clinical work, and mechanical valves may be a better choice for the population with VHD combined with PH. Zhao Ying et al. found that the extubating time of tracheal intubation was a risk factor for postoperative hospital-acquired pneumonia after valve replacement (18), and the present study similarly found that the number of tracheal intubation days ≥3d was independently associated with postoperative hospital-acquired pneumonia. Tracheal intubation leads to the communication between the patient's airway and the external environment, which makes it easier for pathogenic bacteria to invade the respiratory tract, and prolonged intubation is highly irritating to the organism, which is prone to cause respiratory mucosal damage and increased secretion, leading to an increased risk of postoperative hospital-acquired pneumonia in patients. Indwelling nasogastric tube is closely associated with respiratory complications, mostly related to intubation into the trachea by mistake and aspiration (30). In this study, we found that the risk of postoperative hospital-acquired pneumonia in patients with VHD combined with PH increased with prolongation of the postoperative indwelling gastric tubes. Therefore, intubation and nasogastric operation should be strictly observed in clinical work; accurate intubation, prevention of mis-aspiration, and early extubation are preferred.

In this study, we constructed a nomogram model for the risk of hospital-acquired pneumonia after valve replacement in patients with VHD combined with PH based on the multifactorial logistic regression analysis results. We used various methods to validate the predictive efficacy of the model, such as the C-index, the corrected C-index, the corrected curve, and the Hosmer-Lemeshow test. The results showed that the model had good predictive efficacy. In addition, the clinical validity of the model was verified in this study using clinical decision curves and clinical impact curves (31), and the results showed that the net benefit value of the model was high in the range of 10%–95%. The model determined that the number of high-risk individuals was a high match to the actual number of infected individuals when the threshold probability was greater than 0.5. Therefore, the model has good predictive efficacy and clinical validity.

There were some limitations in the present study. First, the samples were from a single center and were not validated in other hospitals. Additionally, our study converted certain continuous variables into binary variables based on the best cut-off values. This may result in information loss and potentially reduce model accuracy, although dichotomized continuous variables may have more clinical relevance. Last, the sample size did not support external validation of the model. Subsequent large-sample, multi-center studies are needed to validate the model further and make it truly applicable to clinical practice.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study found that ASA score > grade III, duration of operation ≥313 min, preoperative anemia, bioprosthetic valve, days of tracheal intubation ≥3d, and days of indwelling gastric tube ≥1d were independent perioperative risk factors for postoperative hospital-acquired pneumonia after valve replacement in patients with VHD combined with PH. The established nomogram model has good internal validity and predictive efficacy, which is conducive to the early screening of hospital-acquired pneumonia after valve replacement. Future multi-center studies with large samples are needed to validate the model further.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by The Ethics Commission of Qilu Hospital of Shandong University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The need for written informed consent to participate in this study was waived by the hospital ethics committee.

Author contributions

YL: Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. XW: Data curation, Investigation, Software, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. SW: Conceptualization, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. YC: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was supported by Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province, China (Grant No. ZR2022QH386) and the funding agency has no role in the study.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Chung CH Wang YJ Lee CY . Epidemiology of heart valve disease in Taiwan: a population-based cohort study. Int Heart J. (2021) 62(5):1026–34. 10.1536/ihj.21-044

2.

Coffey S Roberts-Thomson R Brown A Carapetis J Chen M Enriquez-Sarano M et al Global epidemiology of valvular heart disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. (2021) 18(12):853–64. 10.1038/s41569-021-00570-z

3.

Yang Y Wang Z Chen Z Zhang L Li S Zheng C et al Current status and etiology of valvular heart disease in China: a population-based survey. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. (2021) 21(1):339. 10.1186/s12872-021-02154-8

4.

Dziadzko V Clavel MA Dziadzko M Medina-Inojosa JR Michelena H Maalouf J et al Outcome and undertreatment of mitral regurgitation: a community cohort study. Lancet. (2018) 391(10124):960–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30473-2

5.

Fang JC Demarco T Givertz MM Borlaug BA Lewis GD Rame JE et al World health organization pulmonary hypertension group 2: pulmonary hypertension due to left heart disease in the adult—a summary statement from the pulmonary hypertension council of the international society for heart and lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. (2012) 31(9):913–33. 10.1016/j.healun.2012.06.002

6.

Breitling S Ravindran K Goldenberg NM Kuebler WM . The pathophysiology of pulmonary hypertension in left heart disease. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. (2015) 309(9):L924–41. 10.1152/ajplung.00146.2015

7.

Caravita S Faini A D’Araujo SC Carolino D’Araujo S Dewachter C Chomette L et al Clinical phenotypes and outcomes of pulmonary hypertension due to left heart disease: role of the pre-capillary component. PLoS One. (2018) 13(6):e0199164. 10.1371/journal.pone.0199164

8.

Alamri AK Ma CL Ryan JJ . Left heart disease-related pulmonary hypertension. Cardiol Clin. (2022) 40(1):69–76. 10.1016/j.ccl.2021.08.007

9.

Farber HW Gibbs S . Under pressure: pulmonary hypertension associated with left heart disease. Eur Respir Rev. (2015) 24(138):665–73. 10.1183/16000617.0059-2015

10.

Pullamsetti SS Mamazhakypov A Weissmann N Seeger W Savai R . Hypoxia-inducible factor signaling in pulmonary hypertension. J Clin Invest. (2020) 130(11):5638–51. 10.1172/JCI137558

11.

Desai A Desouza SA . Treatment of pulmonary hypertension with left heart disease: a concise review. Vasc Health Risk Manag. (2017) 13:415–20. 10.2147/VHRM.S111597

12.

Xiangbin P Yaling H Shengshou H . Chinese Guideline for the clinical application of transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Natl Med J China. (2023) 103(12):886–900. 10.3760/cma.j.cn112137-20221106-02332

13.

Porterie J Kalavrouziotis D Dumont E Paradis JM De Larochellière R Rodes-Cabau J et al Clinical impact of the heart team on the outcomes of surgical aortic valve replacement among octogenarians. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. (2023) 165(3):1010–1019.e5. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2021.03.030

14.

Muller DWM Farivar RS Jansz P Bae R Walters D Clarke A et al Transcatheter mitral valve replacement for patients with symptomatic mitral regurgitation: a global feasibility trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2017) 69(4):381–91. 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.10.068

15.

Wei RS Gao HT Qi HW Chen XW Yan XJ Wang LH . Influencing factors for postoperative pulmonary infection in cardiac valve replacement patients and changes of myocardial enzymes. Chin J Nosocomiol. (2019) 29(21):3266–74. 10.11816/cn.ni.2019-183643

16.

Wu G Fu Y Feng W Liu C Li J Gao H et al Prevalence and risk factors for ventilator-associated pneumonia after cardiac surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thorac Dis. (2024) 16(9):5946–57. 10.21037/jtd-24-324

17.

Barnett NM Liesman DR Strobel RJ Wu X Paone G DeLucia A et al The association of intraoperative and early postoperative events with risk of pneumonia following cardiac surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. (2023) 168(4):1144–1154.e3. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2023.09.056

18.

Zhao Y Liu S Liu S Yan QF Wang S . Related factors for pulmonary infections in patients undergoing heart valve replacement and countermeasure. Chin J Nosocomiol. (2017) 27(17):3948–51. 10.11816/cn.ni.2017-170339

19.

Li Y Li S Zhu J Wang Z Zhang X . Establishment and validation of clinical prediction model and prognosis of perioperative pneumonia in elderly patients with hip fracture complicated with preoperative acute heart failure. BMC Surg. (2024) 24(1):369. 10.1186/s12893-024-02668-w

20.

Song YY Zhang B Gu JW Zhang YJ Wang Y . The predictive value of procalcitonin in ventilator-associated pneumonia after cardiac valve replacement. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. (2020) 80(5):423–6. 10.1080/00365513.2020.1762242

21.

Wan J Zhai Z . Hot point problems in clinical diagnosis, treatment and management of pulmonary hypertension: comparison and interpretation of 2022 ESC/ERS guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension and Chinese guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary artery hypertension (2021 edition).Chin Gen Pract. (2023) 26(3):255–61. 10.12114/j.issn.1007-9572.2022.0692

22.

Tichelbäcker T Dumitrescu D Gerhardt F Stern D Wissmüller M Adam M et al Pulmonary hypertension and valvular heart disease. Herz. (2019) 44(6):491–501. 10.1007/s00059-019-4823-6

23.

Morikane K Honda H Yamagishi T Suzuki S . Differences in risk factors associated with surgical site infections following two types of cardiac surgery in Japanese patients. J Hosp Infect. (2015) 90(1):15–21. 10.1016/j.jhin.2014.11.022

24.

Irlbeck T Zwissler B Bauer A . ASA Classification : transition in the course of time and depiction in the literature. Anaesthesist. (2017) 66(1):5–10. 10.1007/s00101-016-0246-4.

25.

Padmanabhan H Siau K Curtis J Ng A Menon S Luckraz H et al Preoperative Anemia and outcomes in cardiovascular surgery: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Thorac Surg. (2019) 108(6):1840–8. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2019.04.108

26.

Ripoll JG Smith MM Hanson AC Schulte PJ Portner ER Kor DJ et al Sex-Specific associations between preoperative Anemia and postoperative clinical outcomes in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Anesth Analg. (2021) 132(4):1101–11. 10.1213/ANE.0000000000005392

27.

de Faria LB Mejia OV Miana LA Lisboa LAF Manuel V Jatene MB et al Anemia in cardiac surgery—can something bad get worse? Braz J Cardiovasc Surg. (2021) 36(2):165–71. 10.21470/1678-9741-2020-0304

28.

Kulik A Bédard P Lam BK Bedard P Rubens F Hendry P et al Mechanical versus bioprosthetic valve replacement in middle-aged patients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. (2006) 30(3):485–91. 10.1016/j.ejcts.2006.06.013

29.

Head SJ Çelik M Kappetein AP . Mechanical versus bioprosthetic aortic valve replacement. Eur Heart J. (2017) 38(28):2183–91. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx141

30.

Motta APG Rigobello MCG Silveira RdC Gimenes FRE . Nasogastric/nasoenteric tube-related adverse events: an integrative review. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. (2021) 29:e3400. 10.1590/1518-8345.3355.3400

31.

Kerr KF Brown MD Zhu K Janes H . Assessing the clinical impact of risk prediction models with decision curves: guidance for correct interpretation and appropriate use. J Clin Oncol. (2016) 34(21):2534–40. 10.1200/JCO.2015.65.5654

Summary

Keywords

heart valve disease, hospital-acquired pneumonia, nomogram, postoperative recovery, pulmonary hypertension, valve replacement

Citation

Liu Y, Wang X, Wang S and Cao Y (2026) Nomogram prediction model for pneumonia after valve replacement in patients with heart valve disease. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 13:1670003. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2026.1670003

Received

21 July 2025

Revised

03 January 2026

Accepted

12 January 2026

Published

30 January 2026

Volume

13 - 2026

Edited by

Sri Harsha Patlolla, Mayo Clinic, United States

Reviewed by

Marija Zdraveska, Saints Cyril and Methodius University of Skopje, North Macedonia

Yanhai Meng, Peking Union Medical College & Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Liu, Wang, Wang and Cao.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Yingjuan Cao caoyj@sdu.edu.cn

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.