Abstract

Introduction:

Limited single-center studies suggest that intensified blood pressure (BP) control in patients with asymptomatic elevated BP during non-cardiac admissions may lead to worse outcomes. In this study, we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis exploring the safety of intensified BP control vs. a more conservative approach in patients with asymptomatic elevated BP during non- cardiac admissions and at discharge, focusing on stroke, acute kidney injury (AKI), myocardial infarction (MI), and length of stay (LOS).

Methods:

Four retrospective propensity score-matched cohort studies (n = 77,448) were included. The intensified BP control group (n = 38,724) received newly initiated, increased dose, intravenous (IV), or pro re nata (PRN) antihypertensive medication, including PRN with scheduled therapy. The non-intensified group (n = 38,724) included patients continuing their preadmission regimen, scheduled, or with no PRN antihypertensives. Follow-up began after the first inpatient antihypertensivedose or at discharge and continued until (1) 30 days postdischarge, (2) hospitaldischarge, or (3) both, depending on the study. Patients with hypertensive emergencies, stroke, MI, or aortic dissection at admission were excluded.

Results:

Intensified BP control was associated with increased odds of stroke (OR 3.77; 95% CI 1.38–10.27; p < 0.010), AKI (OR 1.23; 95% CI 1.13–1.33; p < 0.00001), and longer LOS (MD 1.17; 95% CI 1.11–1.93; p < 0.00001). No statistically significant increase of MI was noted (OR 2.04; 95% CI 0.85–4.89, p = 0.11). Intensified BP control during non-cardiac hospitalizations and at discharge was linked to higher odds of stroke, AKI, and prolonged hospitalization.

Conclusions:

A more conservative approach may be safer in the absence of acute indications for BP lowering. Prospective, randomized inpatient BP trials, particularly those distinguishing interventions initiated during hospitalization vs. at discharge are warranted to clarify causal relationships and guide evidence-based inpatient BP management.

Systematic Review Registration:

https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/566609, identifier CRD42024566609.

1 Introduction

Hypertension affects approximately 50% of individuals aged over 20 years and remains a significant risk factor for cardiovascular diseases, stroke, and mortality (1, 2). Among hospitalized patients, the prevalence of hypertension is particularly high, ranging from 50.5% to 72% (3). The intensification of antihypertensive treatment during hospitalization has been inconsistent, resulting in 37%–77% of hypertensive patients remaining hypertensive at the time of discharge (3). Furthermore, many patients with inpatient hypertension continue to have uncontrolled BP during outpatient follow-up (3), underscoring the need for improved management strategies. However, changes in medication regimens may put patients at higher risk of adverse events (4). A study in an emergency department found that inpatient blood pressure readings can differ significantly from the patient's home blood pressure level (5). Moreover, patients discharged on substantially intensified antihypertensive regimens have been reported to experience hypotension during follow-up visits (5).

The 2017 and 2019 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/guidelines do not recommend a specific approach for asymptomatic patients with elevated blood pressure in hospitalized settings (6, 7). However, subsequent observational studies suggest that more intensified blood pressure control may be associated with adverse outcomes (3, 8). The 2024 American Heart Association scientific statement consolidates findings from previous studies and recommends that treatment be reserved for select cases, emphasizing observation in the absence of symptoms, noting the need for further studies to clarify whether clinical benefits exist for asymptomatic patients with markedly elevated blood pressure (9). Because of the ongoing lack of randomized controlled trials with data regarding the risks and benefits of blood pressure control in asymptomatic patients, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the safety of intensified BP control during non-cardiac hospitalizations and at discharge in patients with asymptomatic elevated BP.

2 Methods

2.1 Eligibility criteria

We considered studies eligible for inclusion if they (1) were randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or non-randomized cohorts, (2) compared intensified vs. non-intensified management of elevated blood pressure during hospital admission OR on discharge, (3) patients with non-cardiac admissions.

The intensified BP control group was defined as patients receiving a newly initiated, increased dose, intravenous (IV), or pro re nata (PRN) antihypertensive medication, including PRN combined with scheduled therapy. The non-intensified blood pressure control group was defined as patients who continued on their preadmission regimen, scheduled, or had no PRN antihypertensive medication in the regimen. Non-cardiac admission was defined as conditions that do not require specific blood pressure control goals and regimens (studies with patients who had a hypertensive emergency, stroke, MI, or aortic dissection on admission/during hospitalization were excluded).

Patient follow-up began either after the first inpatient dose of antihypertensive medication or at discharge and continued until (1) 30 days postdischarge, OR (2) hospital discharge, OR (3) hospital stay and 30 days’ postdischarge, depending on the study design. Studies were excluded if they (1) lacked a control group or (2) involved a cardiac cause of admission. Definitions of intensified blood pressure control varied slightly across studies and are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1

| Study, year | Patients, n | Blood pressure control criteria | Follow-up period | When intensification occurred | Age,b years | Male, % | Previous stroke, I-BP/nI-BP | HTN, % | SBP on admission, mm Hg, mean | Previous MI, % | Arrhythmias | CKD, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| i-BP/nI-BP | I-BP/nI-BP | I-BP/nI-BP | I-BP/nI-BP | I-BP/nI-BP | I-BP/nI-BP | I-BP/nI-BP | I-BP/nI-BP | I-BP/nI-BP | ||||

| Anderson, 2019 (4) | 2,028/2,028 | New or higher-dose anti-HTNa/before admission regimen | 30 days after discharge | At discharge | 76.8/76.6 | 97.5/97.8 | 17.4./18.6 | NA | 138.3/137.9 | 5.5/5 | 32/31.2 | NA |

| Rastogi, 2020 (8) | 4,520/4,520 | IV anti-HTNa medication or new class of oral anti-HTNa/before admission regimen | Hospitalization and 30 days after discharge | On admission | 69.8/69.7 | 44/43.3 | 7.2/7.2 | 53/52.4 | 138.1/138.1 | 1.8/1.7 | 12.3/11.8 | 14.3/14.7 |

| Mohandas, 2021(26) | 4,219/4,219 | PRNbBP + Scheduled BP/Scheduled BP | Hospitalization | On admission | 62 ± 16/ 63 ± 15 | 45/45 | 33/34 | 90/89 | 157/156 | 15/15 | N/A | 40/41 |

| Caneles, 2025(27) | 27,957/27,957 | PRNbBP/No PRN BP | Hospitalization | On admission | 71.0 ± 11.8/71.4 ± 11.5 | 96.7/96.8 | 12.8/12.8 | 76.8/76.7 | 155.7/154.7 | N/A | N/A | 26.3/27.6 |

Baseline characteristics of the included studies.

CKD, chronic kidney disease; HTN, hypertension; I-BP, intensified blood pressure group; MI, myocardial infarction; N/A, not available; nI-BP, non-intensified blood pressure group; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Antihypertensive medication.

As needed.

2.2 Data source and search strategy

We systematically searched PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane from inception to January 2025 using the terms “inpatient blood pressure control outcomes” and (Hospitalized OR Inpatient OR Non-cardiac) AND (Blood pressure OR Hypertension OR Antihypertensive medication OR Blood pressure control) AND (Intensified OR Conservative OR As needed OR PRN OR Intravenous antihypertensive) AND (Stroke OR Acute Kidney Injury OR AKI OR Myocardial Infarction OR MI OR Length of Stay OR Hospital stay OR Mortality). In addition, we manually searched the references from all included studies for additional studies. Two authors (YK and NB) independently screened titles and abstracts and fully evaluated the articles for eligibility based on prespecified criteria. Discrepancies were resolved in a panel discussion between authors. The prospective meta-analysis protocol was registered at the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; #CRD42024566609) in July 2024.

2.3 Endpoints, meta-regression, and sensitivity analysis

The outcomes of interest were acute kidney injury (AKI), stroke, myocardial infarction (MI), and length of stay (LOS). We performed a sensitivity analysis for studies in which blood pressure (BP) intensification occurred only during hospital stay to isolate the effect of BP intensification during hospitalization. Between-study heterogeneity was investigated using random-effects meta-regression (restricted maximum likelihood estimator with Hartung–Knapp adjustment), testing the effect of mean age, baseline systolic blood pressure (SBP), and comorbidities (% hypertension, stroke, and CKD) on the pooled effect size. In addition, we performed a leave-one-out sensitivity analysis to explore the impact of separate studies on the cumulative analysis for stroke and AKI.

2.4 Quality assessment

Non-randomized studies were assessed using the Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies of Interventions tool (ROBINS-I) (10). Two independent authors (YK and NB) conducted the risk of bias assessment. Disagreements were resolved through consensus after discussing the reasons for the discrepancies. Publication bias was evaluated using a funnel-plot analysis of point estimates about study size.

2.5 Statistical analysis

This systematic review and meta-analysis was performed and reported by following the Cochrane Collaboration Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) Statement guide (11). Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to compare treatment effects for categorical endpoints. Continuous outcomes were compared using standardized mean differences (MD). Heterogeneity was assessed using I2 statistics and the Cochran Q test; p-values <0.10 and I2 > 25% were considered indicative of significant heterogeneity. We applied the random-effects model with the Restricted Maximum-Likelihood (REML) estimator. A statistical analysis was performed using ReviewManager (Cochrane Center, The Cochrane Collaboration, Denmark) and R (4.5.1 version).

3 Results

3.1 Study selection and baseline characteristics

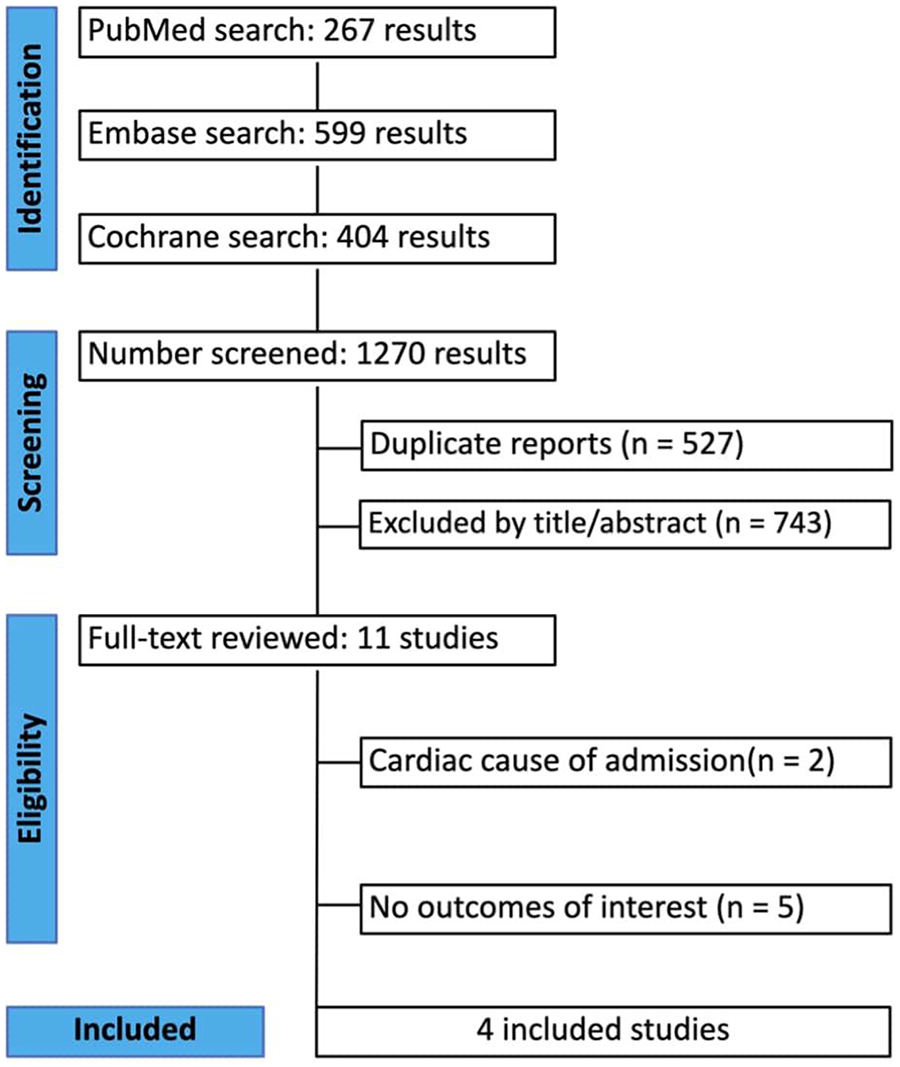

Our systematic search yielded 1,270 results. After removing duplicate records and ineligible studies, 11 studies remained and were fully reviewed based on the inclusion criteria. Of these, four retrospective propensity score–matched cohort studies, comprising 77,448 patients, were included. Comprehensive details of the study selection are given in Figure 1.

Figure 1

A PRISMA flow diagram of study screening and selection.

A total of 38,724 patients received an intensified blood pressure control regimen, while 38,724 patients received a non-intensified blood pressure control regimen. The mean SBP in the intensified group was 147.3 mmHg, compared with 146.7 mmHg in the non-intensified group. The mean age was 69.9 years in the intensified management arm and 70.1 years in the conservative arm. In the intensified group, 70.8% of patients were male, while 70.7% were male in the non-intensified group. Table 1 summarizes the main characteristics of the included studies. Outcome-level sample sizes varied across studies and are mentioned in the pooled analysis section and Figures 2–5 for each specific outcome.

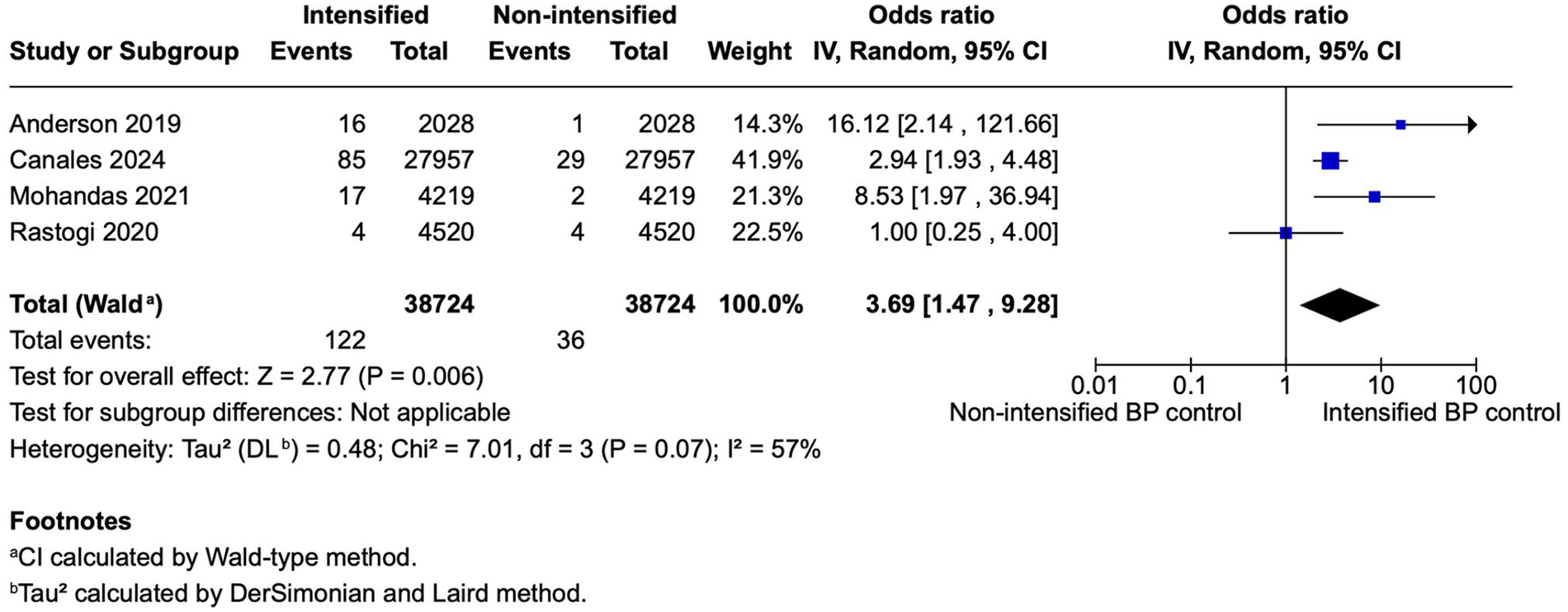

Figure 2

A forest plot showing the odds of stroke between intensified and non-intensified inpatient blood pressure control strategies. Each study is represented by a blue square, proportional to its weight in the random-effects model, and the horizontal lines indicate the 95% CI. The pooled OR is shown as a black diamond. A random-effects model (restricted maximum-likelihood method) was applied with confidence intervals calculated using the Wald-type method. Overall, intensified BP control was associated with a significantly higher odds of adverse events compared with non-intensified control (pooled OR = 3.77, 95% CI 1.38–10.27, p = 0.010; I2 = 63%). BP, blood pressure; CI, confidence interval; IV, inverse variance; OR, odds ratio; REML, restricted maximum-likelihood; Wald, Wald-type method.

Figure 3

![Forest plot showing four studies comparing intensified versus non-intensified blood pressure control. Each study displays odds ratios and confidence intervals, with a total odds ratio of 1.22 [1.14, 1.31]. Data include events, totals, and weights, with a significant overall effect (Z = 5.54, P < 0.00001). Heterogeneity is low with I² = 26%.](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1691926/xml-images/fcvm-13-1691926-g003.webp)

A forest plot showing the odds of AKI between intensified and non-intensified inpatient BP control strategies. Individual study estimates are represented by blue squares proportional to study weight, with the horizontal lines denoting 95% CIs. The pooled effect estimate (black diamond) was calculated using a random-effects model based on the REML method, with CIs derived using the Wald-type approach. Overall, intensified BP control was associated with a modest but statistically significant increase in the odds of adverse events compared with non-intensified control (pooled OR = 1.23, 95% CI 1.13–1.33; p < 0.00001). Between-study heterogeneity was moderate (I2 = 38%). AKI, acute kidney injury; BP, blood pressure; CI, confidence interval; IV, inverse variance; OR, odds ratio; REML, restricted maximum-likelihood; Wald, Wald-type method.

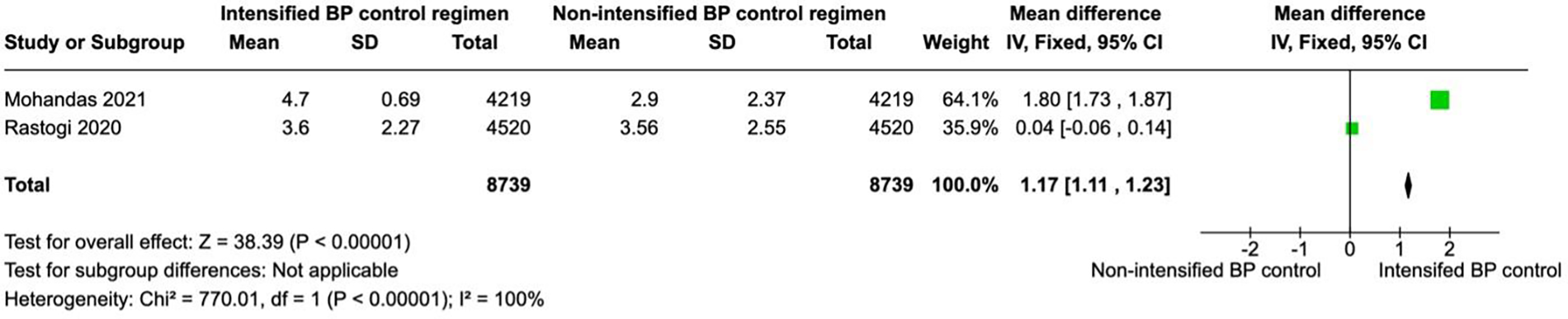

Figure 4

A forest plot showing the length of stay in intensified and non-intensified blood pressure control groups. Each study is represented by a green square proportional to its weight, with the horizontal lines indicating 95% CIs. The pooled mean difference (black diamond) was calculated using a fixed-effects inverse-variance model. Overall, patients in the intensified BP control group had a significantly higher length of stay SBP compared with those in the non-intensified group (pooled mean difference = 1.17 mm Hg, 95% CI 1.11–1.23; p < 0.00001). Heterogeneity across studies was high (I2 = 100%, p < 0.00001). BP, blood pressure; CI, confidence interval; IV, inverse variance.

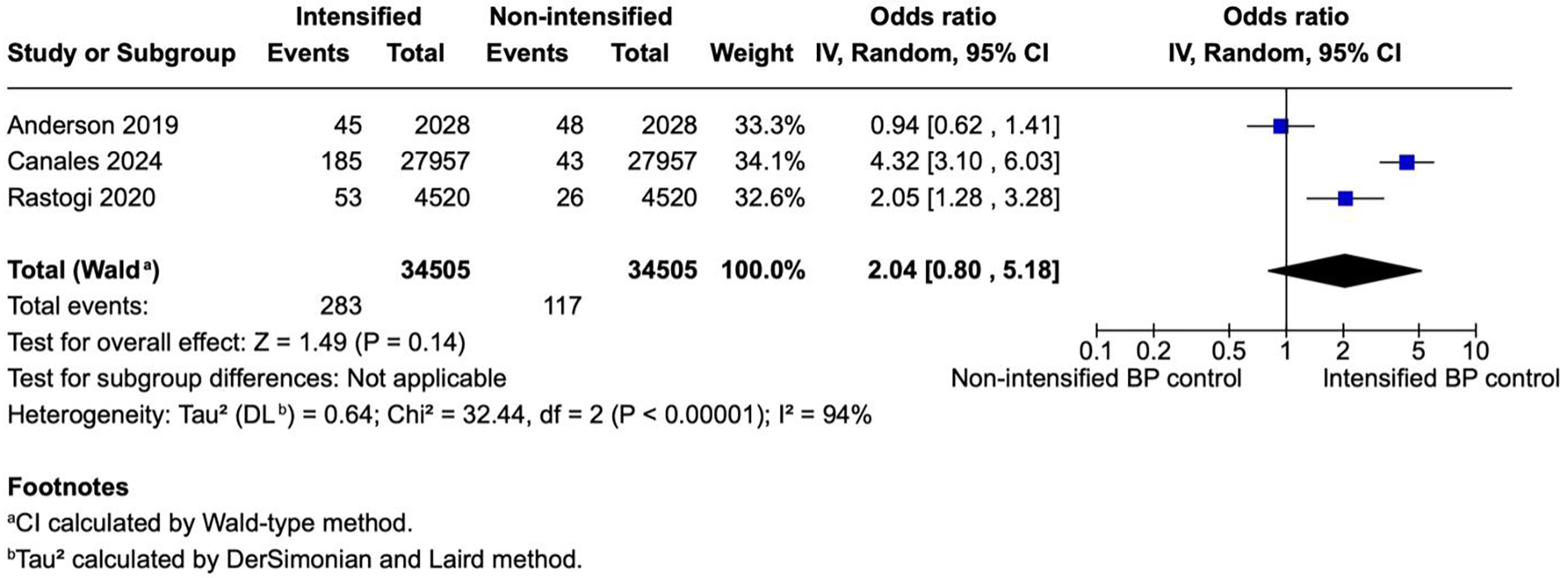

Figure 5

A forest plot showing the odds of myocardial infarction in intensified and non-intensified blood pressure control groups. Individual studies are represented by blue squares proportional to their weight, with the horizontal lines indicating 95% CIs. The pooled estimate (black diamond) was calculated using a random-effects model (restricted maximum-likelihood method) with CIs derived by the Wald-type approach. Across three retrospective cohort studies, intensified BP control was associated with a non-significant trend toward higher odds of MI event (pooled OR = 2.04, 95% CI 0.85–4.89; p = 0.11). Substantial between-study heterogeneity was observed (I2 = 93%, p < 0.00001). BP, blood pressure; CI, confidence interval; IV, inverse variance; MI, myocardial infarction; OR, odds ratio; REML, restricted maximum-likelihood; Wald, Wald-type method.

3.2 Pooled analysis of all studies

3.2.1 Incidence of stroke

Four studies (N = 77,448) reported stroke outcomes, including 38,724 patients per group. The pooled analysis showed significantly higher odds of stroke in the intensified blood pressure control group compared with the non-intensified control group (OR 3.77; 95% CI 1.38–10.27; p < 0.010; Figure 2). Heterogeneity was moderate, with I2 = 63%.

3.2.2 Incidence of AKI

Four studies (N = 71,380) reported AKI outcomes, including 35,690 patients per group. The pooled analysis showed significantly higher odds of AKI in the intensified blood pressure control group compared with the non-intensified control group (OR 1.23; 95% CI 1.13–1.33; p < 0.00001; Figure 3). Heterogeneity was low, with I2 = 38%.

3.2.3 Length of stay

Two studies (N = 17,478) reported hospital length of stay, with 8,739 patients in each group. Intensified blood pressure control was associated with a significantly longer length of stay than non-intensified blood pressure control (MD 1.17; 95% CI 1.11–1.23; p < 0.01; Figure 4). The results showed a high heterogeneity with I2 = 100%.

3.2.4 Myocardial infarction

Three studies (N = 69,010) reported MI outcomes, including 34,505 patients per group. There was no statistically significant difference in the odds of myocardial infarction between the intensified blood pressure control group and the non-intensified blood pressure control group (OR 2.04; 95% CI 0.85–4.89; p = 0.11; Figure 5). The results showed a high heterogeneity with I2 = 9%.

3.2.5 Meta-regression

To explore sources of between-study heterogeneity, we used univariable random-effects meta-regression models (Hartung–Knapp adjustment). As shown in Table 2, mean age was significantly associated with the pooled effect size (β = 0.089, 95% CI 0.043–0.136; p = 0.014). Each additional year of mean age corresponded to an approximately 9% increase in the odds of adverse outcomes, fully explaining between-study heterogeneity (R2 = 100%).

Table 2

| Moderator | β (log OR) | 95% CI | p-value | Exp (β) (OR) | R 2 (%) | Direction of association |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (years) | 0.089 | 0.043–0.136 | 0.014 | 1.09 per +1 year | 100 | Older cohorts → higher risk |

| SBP (mm Hg) | –0.039 | –0.159–0.082 | 0.30 | 0.96 per +1 mm Hg | 31 | Non-significant, slight negative trend |

| Hypertension (% per 10 points) | –0.246 | –2.71–2.22 | 0.43 | 0.78 per +10% | 42 | Non-significant |

| Prior stroke (% per 10 points) | –0.412 | –2.84–2.02 | 0.28 | 0.66 per +10% | 86 | Non-significant |

| CKD (% per 10 points) | –0.421 | –2.62–1.78 | 0.25 | 0.66 per +10% | 92 | Non-significant |

Univariable meta-regression results (Hartung–Knapp REML models).

Random-effects meta-regression analyses were performed using the Hartung–Knapp–Sidik–Jonkman adjustment and restricted maximum-likelihood estimation to explore potential study-level modifiers of the pooled odds ratio. Among evaluated moderators, mean age was significantly associated with the overall effect size (β = 0.089, 95% CI 0.043–0.136; p = 0.014), indicating that each additional year of mean age corresponded to an approximately 9% increase in the odds of adverse outcomes and accounted for all between-study heterogeneity (R2 = 100%). Systolic blood pressure on admission, prevalence of hypertension, prior stroke, and chronic kidney disease showed no statistically significant associations (all p > 0.05).

In contrast, other study-level characteristics—including admission SBP (β = –0.039, p = 0.30), prevalence of hypertension (β = –0.246, p = 0.43), prior stroke (β = –0.412, p = 0.28), and chronic kidney disease (β = –0.421, p = 0.25)—were not significantly associated with the pooled effect size. These non-significant trends suggested a possible but weak inverse relationship between higher comorbidity burden and outcome, with minimal explanatory contribution to heterogeneity (R2 = 31%–92%).

3.2.6 Sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity analyses restricted to studies with BP intensification during hospitalization revealed a statistically significant association with MI (OR 3.08; 95% CI 1.46–6.30; p = 0.003; I2 = 84%; Supplementary Figure S3). A similar result to a pooled analysis was yielded for stroke (OR 2.88; 95% CI 1.16–7.16; p = 0.02; I2 = 55%; Supplementary Figure S1) and AKI (OR 1.22; 95% CI 1.13–1.33; p < 0.00001; I2 = 47%; Supplementary Figure S2).

A leave-one-out sensitivity analysis was performed to explore the impact of separate studies on the cumulative analysis for stroke and AKI. Overall, the results remained similar to those of the primary analysis. The sensitivity analysis results are presented in Supplementary Figures S4, S5.

3.2.7 Quality assessment

No studies were considered at high risk of bias as described in Supplementary Table S1. In the funnel plot (Supplementary Figure S6), studies occupied symmetrical distribution according to weight and converged toward the pool effect as the weight increase.

4 Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis of four studies involving 77,448 patients evaluated the clinical outcomes associated with intensified vs. non-intensified blood pressure (BP) management at admission and discharge in asymptomatic patients with elevated BP. Intensified BP control was associated with a significantly higher odds of stroke (OR 3.77), AKI (OR 1.23), and a longer hospital stay (MD 1.17 days). While the pooled analysis did not show a statistically significant increase in myocardial infarction (MI), a sensitivity analysis limited to in-hospital BP intensification demonstrated a significant association. This analysis addresses a critical gap in inpatient hypertension management, where evidence-based guidance remains limited.

Asymptomatic elevated blood pressure (BP) was reported to be present in 50%–72% of hospitalizations (3). In patients with hypertensive emergency, the approach to blood pressure control is well established; however, a majority of hospital encounters with elevated blood pressure do not have an indication to pursue tight blood pressure control. The 2019 American Heart Association guideline does not recommend a specific approach because of the lack of evidence (7); however, the 2024 AHA Scientific Statement recommends observation while highlighting that further studies are needed to clarify whether there is a clinical benefit for asymptomatic patients with markedly elevated blood pressure (9).

Elevated BP readings can be a concerning finding during a hospital stay. A survey of 181 residents across three US hospitals revealed that 44% would initiate or adjust antihypertensive treatment if the SBP ranged from 140 to 159 mmHg (12). In clinical practice, elevated BP readings often prompt PRN antihypertensive administration, driven by cardiovascular risk profiles, nursing alarms, and vital sign thresholds (9). This reactive approach can induce BP variability by overcorrection and withholding of scheduled antihypertensives, potentially creating a self-perpetuating cycle.

The hospital environment is teeming with reversible causes for elevated BP. Key contributors include anxiety, sleep deprivation, psychological stress, and pain, all of which need to be carefully assessed and managed. Various inpatient medications such as IV fluids, corticosteroids, and NSAIDs can also elevate BP. Moreover, inaccurate home medication reconciliation can lead to rebound hypertension. A retrospective review found that 41% of patients prescribed PRN antihypertensive medications did not receive their usual home BP regimen while hospitalized. Addressing these factors is crucial for effective BP management and preventing unnecessary complications (13).

4.1 Mechanisms

Autoregulation is a mechanism that enables organs such as the brain, heart, and kidneys to maintain stable blood perfusion by adjusting their vasculature resistance in response to fluctuations in perfusion pressure (14). In individuals with normal blood pressure, the brain's vascular resistance adjusts over a wide range of mean arterial pressures to maintain consistent blood flow (15). However, in patients with chronically elevated blood pressure, the autoregulatory curve shifts to the right, with a subsequent risk of hypoperfusion when administering antihypertensive medication, as the precise lower limit of autoregulation in individual hypertensive patients is often unknown (15). This shift in autoregulation could help explain the study's findings, where intensified blood pressure control was associated with significantly higher odds of stroke and AKI. Meta-regression identified mean age as a significant effect modifier, suggesting that older inpatient populations derive less benefit—or greater harm—from intensified BP control. This aligns with evidence that age-related vascular stiffness and autonomic dysregulation may reduce tolerance for rapid BP lowering (16).

4.2 Stroke

Elevated BP is a well-established and highly impactful modifiable risk factor for stroke (17). The slight difference in mean SBP between groups (147.3 vs. 146.7 mmHg) seems insufficient to explain the observed adverse outcomes. However, mean values may obscure clinically significant fluctuations in BP. BP variability, not captured in these averages, could be a more important driver of stroke risk. Given the rightward shift in the autoregulatory curve among chronically hypertensive patients, intensified BP lowering may reduce perfusion below the autoregulatory threshold, increasing stroke risk. Intensified BP control can lead to substantial BP fluctuations, which might be more harmful than consistently elevated BP (18). Higher BP fluctuations after stroke are associated with a higher risk of death within 90 days (19). Paradoxically, while efforts to control BP are aimed at preventing adverse outcomes, including stroke, such intensified management may inadvertently increase the risk of stroke.

Crucial variables such as atrial fibrillation were reported only in one study, and their corresponding CHADS-VASc scores were not reported in any of the studies, which may lead to variations in the stroke risk between cohorts. The use of multiple blood pressure medications and different routes of administration, along with variable definitions of “intensified” and “non-intensified” groups and their patients, together with the lack of randomized trials, appears to significantly contribute to the moderate heterogeneity of results, which was corroborated in our sensitivity analysis.

4.3 AKI

AKI is a common clinical event that affects up to 15% of hospitalized patients (20). A total of 20%–50% of AKI patients develop progressive CKD, while 3%–15% reach end-stage kidney disease, all associated with increased mortality (21). Hypertension and hypotension are well-known risk factors for AKI; however, BP variability may also contribute. Our finding of increased AKI risk (OR 1.22) may reflect not only hypotension but also BP variability, as supported by perioperative studies demonstrating AKI risk from fluctuations in SBP independent of mean BP (22). Another study in patients undergoing surgery for acute aortic dissection showed that patients with AKI had higher SBP variability (23). Underlying chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a known risk factor for AKI (24); however, it is unlikely to account for a higher AKI rate in the intensified BP control group because of a similar rate of CKD in both groups. One included study had a high proportion of UTI admissions—a known AKI risk factor (4, 25). However, both groups had similar UTI rates, and the exclusion of this study did not alter the pooled AKI estimate.

4.4 Myocardial infarction

In contrast to the pooled analysis, the sensitivity analysis limited to in-hospital BP intensification showed significantly increased MI risk. This discrepancy may be due to the use of intravenous antihypertensive medications during hospitalization, which can cause abrupt reductions in perfusion pressure. The shorter follow-up in the sensitivity analysis may capture early adverse events from such interventions, while the longer follow-up in the pooled analysis may dilute these effects by reflecting overall cardiovascular risk. However, the presence of only two studies in the sensitivity analysis and high heterogeneity warrant careful interpretation of these results. Despite high statistical heterogeneity (e.g., I2 = 94% for myocardial infarction and 100% for length of stay), quantitative pooling was retained to provide an overall estimate under a random-effects model. The decision to pool was based on the clinical and methodological comparability of included studies; each study examined intensified vs. standard blood pressure management in non-cardiac hospitalizations using similar definitions of exposure and outcomes. Furthermore, directionality of effects was largely consistent across studies, suggesting a shared underlying effect despite differences in magnitude. Quantitative synthesis thus complements the narrative summary by providing a global measure of association, while acknowledging uncertainty due to heterogeneity.

4.5 Strengths and limitation

The findings from the current study should be interpreted as hypothesis-generating within the context of its limitations. First, all included studies were observational despite adjustment using propensity score matching; the individual patient risk for stroke and AKI was not considered. Second, there were mild variations in the definition of intensified and non-intensified blood pressure across the studies, despite the same principle: patients received more antihypertensive medication in the intensified group compared with the conservative management group. Our analysis is limited by significant heterogeneity, potentially due to the use of various antihypertensive classes and administration routes. Potential confounders may be the more frequent IV administration route and more frequent hydralazine use in the intensified BP control group. These factors highlight the need for further randomized studies to answer these clinical questions. All studies included only older adults, with a mean age of approximately 70; thus, our findings are not generalizable to younger populations.

A notable methodological heterogeneity among the included studies relates to the timing of blood pressure (BP) intensification. In their study, Anderson et al. (4) initiated antihypertensive intensification only at hospital discharge, whereas the remaining studies (8, 26, 27) implemented treatment adjustments during the inpatient stay. This distinction carries clinical significance, as in-hospital intensification exposes patients to the acute hemodynamic fluctuations and autoregulatory challenges associated with the hospital environment—factors that are largely absent when therapy is initiated at discharge. Consequently the Anderson et al. (4) study primarily reflects outpatient hemodynamic adaptation rather than true inpatient exposure. When this study was excluded in a subgroup analysis, the direction and magnitude of associations for stroke, AKI, and MI remained consistent with the overall pooled estimates, suggesting that the main findings were robust and not driven by timing-related differences. Nonetheless, these results highlight the need for future investigations to distinguish between inpatient and discharge-only BP management, as these represent distinct clinical interventions with potentially divergent risk profiles.

Future research should focus on prospective, randomized controlled trials designed specifically to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of intensified BP management in the inpatient setting. Such trials should be stratified by the timing of intervention—that is, whether blood pressure intensification occurs during hospitalization or is initiated at discharge, as the pathophysiological and clinical contexts may differ substantially. Incorporating standardized BP targets, consistent adverse event definitions, and follow-up into the postdischarge period will be essential. In addition, future studies should address modifiable inpatient contributors to transient BP elevation, such as anxiety, pain, medication reconciliation, and iatrogenic fluid shifts, to better inform intervention thresholds and avoid overtreatment.

6 Conclusion

In this meta-analysis of patients with non-cardiac admissions, our findings suggest that intensified blood pressure control during admission and on discharge was associated with significantly higher odds of stroke, AKI, and prolonged length of stay. The increased chance of MI was not statistically significant. These findings, derived exclusively from retrospective observational cohorts, underscore the potential harm of intensified blood pressure control and highlight the urgent need for prospective, randomized inpatient BP trials, particularly those comparing interventions initiated during hospitalization vs. at discharge to establish causal relationships and optimize inpatient hypertension management.

Statements

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. The data can be found here: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.3007; https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.7501; https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.121.17279; https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2024.6213.

Author contributions

YK: Methodology, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Software, Investigation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Formal analysis. NB: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Methodology. PA-S: Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. ER: Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. IS: Data curation, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. AS: Resources, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Methodology. KG: Writing – review & editing, Resources, Visualization, Software, Writing – original draft. MS: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Software, Resources. SB: Resources, Writing – review & editing. ES: Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Validation, Methodology, Project administration.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence, and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors, wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcvm.2026.1691926/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis; PROSPERO, International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews; RCT, randomized controlled trial; ROBINS—I, Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies of Interventions; PRN, pro re nata (as needed); AKI, acute kidney injury; CKD, chronic kidney disease.

References

1.

Weder AB . Treating acute hypertension in the hospital. Hypertension. (2011) 57(1):18–20. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.164194

2.

Prospective Studies Collaboration. Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet. (2002) 360(9349):1903–13. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11911-8

3.

Axon RN Cousineau L Egan BM . Prevalence and management of hypertension in the inpatient setting: a systematic review. J Hosp Med. (2011) 6(7):417–22. 10.1002/jhm.804

4.

Anderson TS Jing B Auerbach A Wray CM Lee S Boscardin WJ et al Clinical outcomes after intensifying antihypertensive medication regimens among older adults at hospital discharge. JAMA Intern Med. (2019) 179(11):1528–36. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.3007

5.

Tanabe P Persell SD Adams JG McCormick JC Martinovich Z Baker DW . Increased blood pressure in the emergency department: pain, anxiety, or undiagnosed hypertension?Ann Emerg Med. (2008) 51(3):221–9. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.10.017

6.

Whelton PK Carey RM Aronow WS Casey DE Collins KJ Dennison Himmelfarb C et al 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice guidelines. Hypertension. (2018) 71(6):e13–e115. 10.1161/hyp.0000000000000065

7.

Arnett DK Blumenthal RS Albert MA Buroker AB Goldberger ZD Hahn EJ et al 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a report of the American college of cardiology/american heart association task force on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. (2019) 140(11):e596–646. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000678

8.

Rastogi R Sheehan MM Hu B Shaker V Kojima L Rothberg MB . Treatment and outcomes of inpatient hypertension among adults with noncardiac admissions. JAMA Intern Med. (2021) 181(3):345–52. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.7501

9.

Bress AP Anderson TS Flack JM Ghazi L Hall ME Laffer CL et al The management of elevated blood pressure in the acute care setting: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertension. (2024) 81(8):e94–e106. 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000238

10.

Sterne JA Hernán MA Reeves BC Savović J Berkman ND Viswanathan M et al ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. Br Med J. (2016) 355:i4919. 10.1136/bmj.i4919

11.

Page MJ McKenzie JE Bossuyt PM Boutron I Hoffmann TC Mulrow CD et al The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Br Med J. (2021) 372:n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71

12.

Neal Axon R Garrell R Pfahl K Fisher JE Zhao Y Egan B et al Attitudes and practices of resident physicians regarding hypertension in the inpatient setting. J Clin Hypertens. (2010) 12(9):698–705. 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2010.00309.x

13.

Gaynor MF Wright GC Vondracek S . Retrospective review of the use of as-needed hydralazine and labetalol for the treatment of acute hypertension in hospitalized medicine patients. Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis. (2018) 12(1):7–15. 10.1177/1753944717746613

14.

Meng L Wang Y Zhang L McDonagh DL . Heterogeneity and variability in pressure autoregulation of organ blood flow: lessons learned over 100+ years. Crit Care Med. (2019) 47(3):436–48. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003569

15.

Ruland S Aiyagari V . Cerebral autoregulation and blood pressure lowering. Hypertension. (2007) 49(5):977–8. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.087502

16.

Herzog MJ Müller P Lechner K Stiebler M Arndt P Kunz M et al Arterial stiffness and vascular aging: mechanisms, prevention, and therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. (2025) 10(1):282. 10.1038/s41392-025-02346-0

17.

Gaciong Z Siński M Lewandowski J . Blood pressure control and primary prevention of stroke: summary of the recent clinical trial data and meta-analyses. Curr Hypertens Rep. (2013) 15(6):559–74. 10.1007/s11906-013-0401-0

18.

de Havenon A Fino NF Johnson B Wong K-H Majersik JJ Tirschwell D et al Blood pressure variability and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with prior stroke. Stroke. (2019) 50(11):3170–6. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.026293

19.

de Havenon A Saini M Bath P Majersik J , Collaboration obotV. Abstract 93: increased blood pressure variability after acute ischemic stroke increases the risk of death. Stroke. (2019) 50(Suppl_1):A93–A. 10.1161/str.50.suppl_1.93

20.

Kister TS Remmler J Schmidt M Federbusch M Eckelt F Isermann B et al Acute kidney injury and its progression in hospitalized patients-results from a retrospective multicentre cohort study with a digital decision support system. PLoS One. (2021) 16(7):e0254608. 10.1371/journal.pone.0254608

21.

Xu L Li C Li N Zhao L Zhu Z Zhang X et al Incidence and prognosis of acute kidney injury versus acute kidney disease among 71 041 inpatients. Clin Kidney J. (2023) 16(11):1993–2002. 10.1093/ckj/sfad208

22.

Park S Lee H-C Jung C-W Choi Y Yoon HJ Kim S et al Intraoperative arterial pressure variability and postoperative acute kidney injury. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. (2020) 15(1):35–46. 10.2215/CJN.06620619

23.

Li Y Zheng T Zhu J Chen Y Chen Y Sun S . Variability of blood pressure and risk of postoperative acute kidney injury in patients undergoing surgery for acute aortic dissection: a 11-year single-center study. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). (2023) 25(5):463–9. 10.1111/jch.14654

24.

Kurzhagen JT Dellepiane S Cantaluppi V Rabb H . AKI: an increasingly recognized risk factor for CKD development and progression. J Nephrol. (2020) 33(6):1171–87. 10.1007/s40620-020-00793-2

25.

Hsiao CY Yang HY Hsiao MC Hung PH Wang MC . Risk factors for development of acute kidney injury in patients with urinary tract infection. PLoS One. (2015) 10(7):e0133835. 10.1371/journal.pone.0133835

26.

Mohandas R Chamarthi G Bozorgmehri S Carlson J Ozrazgat-Baslanti T Ruchi R et al Pro Re nata antihypertensive medications and adverse outcomes in hospitalized patients: a propensity-matched cohort study. Hypertension. (2021) 78(2):516–24. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.121.17279

27.

Canales MT Yang S Westanmo A Wang X Hadley D Ishani A et al As-Needed blood pressure medication and adverse outcomes in VA hospitals. JAMA Intern Med. (2025) 185(1):52–60. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2024.6213

Summary

Keywords

blood pressure, intensified management, conservative management, non-cardiac hospitalizations, inpatient hypertension

Citation

Kushnir Y, Barrera N, Arias-Sanchez P, Romero E, Statnii I, Stolear A, Golovataya K, Solorzano MF, Baghdadi S and Shkolnik E (2026) Intensified blood pressure control during hospital admission and on discharge: a systematic review and meta-analysis of retrospective cohort studies. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 13:1691926. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2026.1691926

Received

24 August 2025

Revised

02 November 2025

Accepted

02 January 2026

Published

05 February 2026

Volume

13 - 2026

Edited by

Evgeny Belyavskiy, MVZ of the German Heart Center of the Charité GmbH, Germany

Reviewed by

Anna Lebedeva, Technical University Dresden, Germany

Neethi Dasu, Jefferson University Hospitals, Philadelphia, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Kushnir, Barrera, Arias-Sanchez, Romero, Statnii, Stolear, Golovataya, Solorzano, Baghdadi and Shkolnik.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Yevhen Kushnir eugenkushnir1@gmail.com Nelson Barrera barrerafigueroa.nelsonmd@gmail.com Evgeny Shkolnik evgeny.shkolnik@yale.edu

†These authors share first authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.