Abstract

Objective:

To analyze the clinical epidemiological characteristics, treatment trends, and risk factors for in-hospital mortality in patients with aortic dissection (AD) at a single center, so as to provide references for early diagnosis and intervention in the emergency department.

Methods:

A retrospective analysis was conducted on the medical records of 1343 AD patients admitted between 2011 and 2024. Statistical descriptions were performed for baseline characteristics, clinical manifestations, imaging classification, treatment, and outcomes. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were employed to identify independent risk factors for in-hospital mortality.

Results:

Among the 1,343 patients, 82.7% were male, with a mean age of 52.7 ± 12.4 years; 71.3% had hypertension. Stanford type A and type B AD accounted for 41.7% and 58.3%, respectively. Acute onset was observed in 76.5% of patients, with chest pain (66.4%) being the most common symptom. The onset of AD showed seasonal (peak in winter, especially December) and diurnal (76.6% of cases presented between 12:00 and 23:00) clustering trends. The rate of surgery was 62.0%, showing an increasing trend over the years. The overall mortality rate was 10.0% (95% CI: 8.4%–11.8%), with type A mortality (16.9%, 95% CI: 14.2%–19.9%) significantly higher than that of type B (4.0%, 95% CI: 2.7%–5.7%). Multivariate analysis identified acute onset (OR = 3.484),chest pain (OR = 1.658), increased heart rate (OR = 1.017), Stanford type A (OR = 3.959) and larger false lumen diameter (OR = 1.357) as independent risk factors for in-hospital mortality (all P < 0.05). Surgery treatment (OR = 0.194) was a protective factor against in-hospital mortality,

Conclusion:

This study indicates that AD predominantly affects middle-aged and elderly males with hypertension, with distinct temporal and seasonal patterns. Acute onset, chest pain, type A dissection, higher heart rate, non-surgical, and larger false lumen diameter significantly increase the risk of in-hospital mortality, highlighting the need for increased vigilance in emergency clinical practice.

1 Introduction

Aortic dissection (AD) is a highly lethal cardiovascular emergency, with a globally increasing incidence in recent years. The epidemiological characteristics of AD in the Chinese population differ significantly from those in Western countries, manifesting as an earlier onset age (approximately 10 years younger on average), a higher prevalence but poorer control of hypertension, and more prominent risk factors such as smoking (1–3). Large-scale studies indicate that uncontrolled hypertension can double the risk of AD (4, 5). However, large-sample studies detailing the evolution of clinical characteristics and their association with outcomes in domestic AD patient populations remain relatively scarce. Regarding prognosis, in-hospital mortality for AD remains high (6). Internationally, risk assessment scoring systems like German Registry for Aortic Dissection type A score exist (7), but their applicability in the Chinese population requires further validation. Most current domestic studies have not comprehensively integrated demographic characteristics, clinical manifestations, and imaging data (e.g., Stanford classification, vascular diameters) to analyze their combined impact on prognosis. Therefore, this study analyzed complete clinical data from 1,343 AD patients between 2011 and 2024, aiming to detail its epidemiological characteristics and thoroughly investigate key factors influencing in-hospital outcomes, thereby providing evidence-based support for improving the prognosis of AD patients.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study population

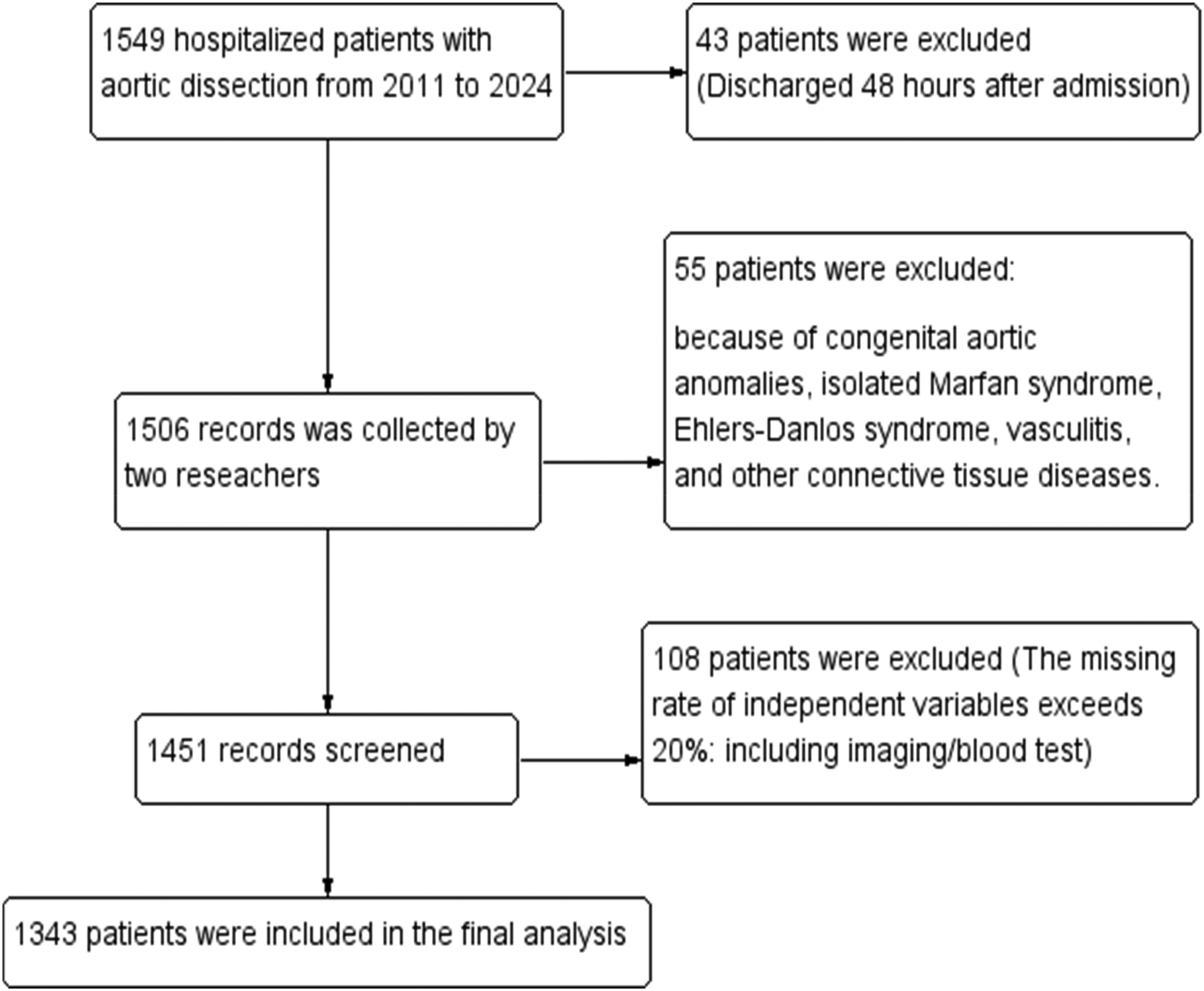

The study included patients with imaging-confirmed AD admitted to the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University between January 2011 and December 2024. Medical records were accessed via the Hospital Information System (HIS), and data were extracted independently by two researchers (Figure 1). To mitigate information bias, data abstraction was performed by two independent investigators using a standardized case report form, with discrepancies resolved by a third senior clinician. All imaging parameters were re-measured by two experienced vascular radiologists blinded to the clinical outcomes, and inter-observer agreement was assessed. AD diagnosis was confirmed by computed tomography angiography (CTA), and typing followed the Stanford criteria (8). Medical history included hypertension, diabetes, smoking (≥10 cigarettes/day for ≥5 years), and alcohol consumption [>2 liang (approx. 100 g) of white liquor or >2 bottles of beer per day]. The diagnosis of hypertension is defined according to the 2024 European Hypertension Guidelines (≥140/90 mmHg) (9). The diagnosis of diabetes requires at least two abnormal laboratory values, such as a fasting plasma glucose ≥126 mg/dL (≥7.0 mmol/L), an HbA1c ≥ 6.5% (≥48 mmol/mol), or a random blood glucose ≥200 mg/dL (≥11.1 mmol/L) (10). Death was defined as: (1) All-cause death occurring during the index hospitalization at the study site, regardless of cause. Death must be formally documented in the hospital record. (2) Patient without biological reflex discharged from study hospital with ongoing mechanical circulatory support, mechanical ventilation, or high-dose vasopressors, with a documented plan for immediate transfer to home. According to the guidelines, patients with aortic dissection are classified into acute phase, subacute phase, and chronic phase based on the time of onset (4).

Figure 1

Flowchart of patient with AD enrollment.

2.2 Statistical analysis

Data were processed using Excel and SPSS 26.0. Quantitative data approximately following a normal distribution are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (x¯ ± s), while skewed data are expressed as median (Q1, Q3). Categorical data were compared using the chi-square (χ²) test, and continuous data using the t-test. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were used to identify risk factors for mortality. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3 Results

3.1 Analysis of clinical characteristics of aortic dissection

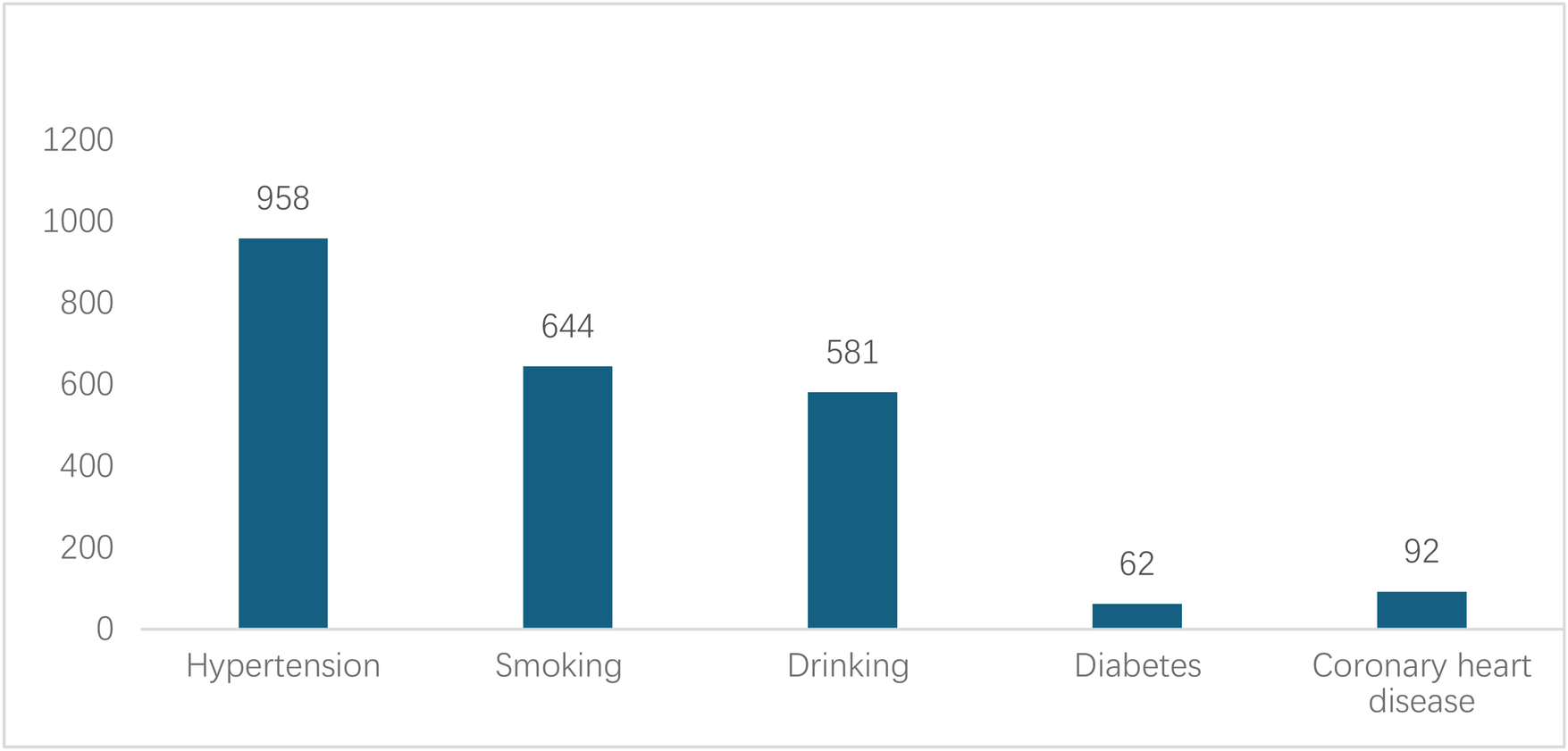

A total of 1343 eligible cases were included, comprising 1110 males and 233 females (male-to-female ratio 4.76:1), with a mean age of 52.7 ± 12.4 years. On admission, 958 patients (71.3%, 95% CI: 68.8%–73.7%) had hypertension; 62 (4.6%) had diabetes mellitus; 644 (48.0%) had a history of smoking; 581 (43.3%) had a history of heavy smoking; and 92 (6.9%) had coronary artery disease (Figure 2). The proportions of Stanford type A and B AD were 41.7% and 58.3%. Age (t = −4.516, P < 0.001), hypertension (χ² = 14.828, P < 0.001), and diabetes (χ² = 4.289, P = 0.038) were significantly associated with Stanford classification. Smoking (χ² = 1.907, P = 0.167) and alcohol consumption (χ² = 3.390, P = 0.079) showed no significant statistical association with Stanford classification (Table 1).

Figure 2

Medical history of patients with AD.

Table 1

| Stanford type | Case | Age | Hypertension | Diabetes | Drinking | Smoking |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 560 | 51.06 ± 11.03 | 368 | 18 | 258 | 284 |

| B | 783 | 53.90 ± 11.05 | 590 | 44 | 323 | 363 |

| t/χ² | −4.516 | 14.828 | 4.289 | 3.390 | 1.907 | |

| p-value | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.038 | 0.079 | 0.167 | |

The age, combined hypertension, diabetes, drinking and smoking history of 1343 Stanford type A and B AD patients.

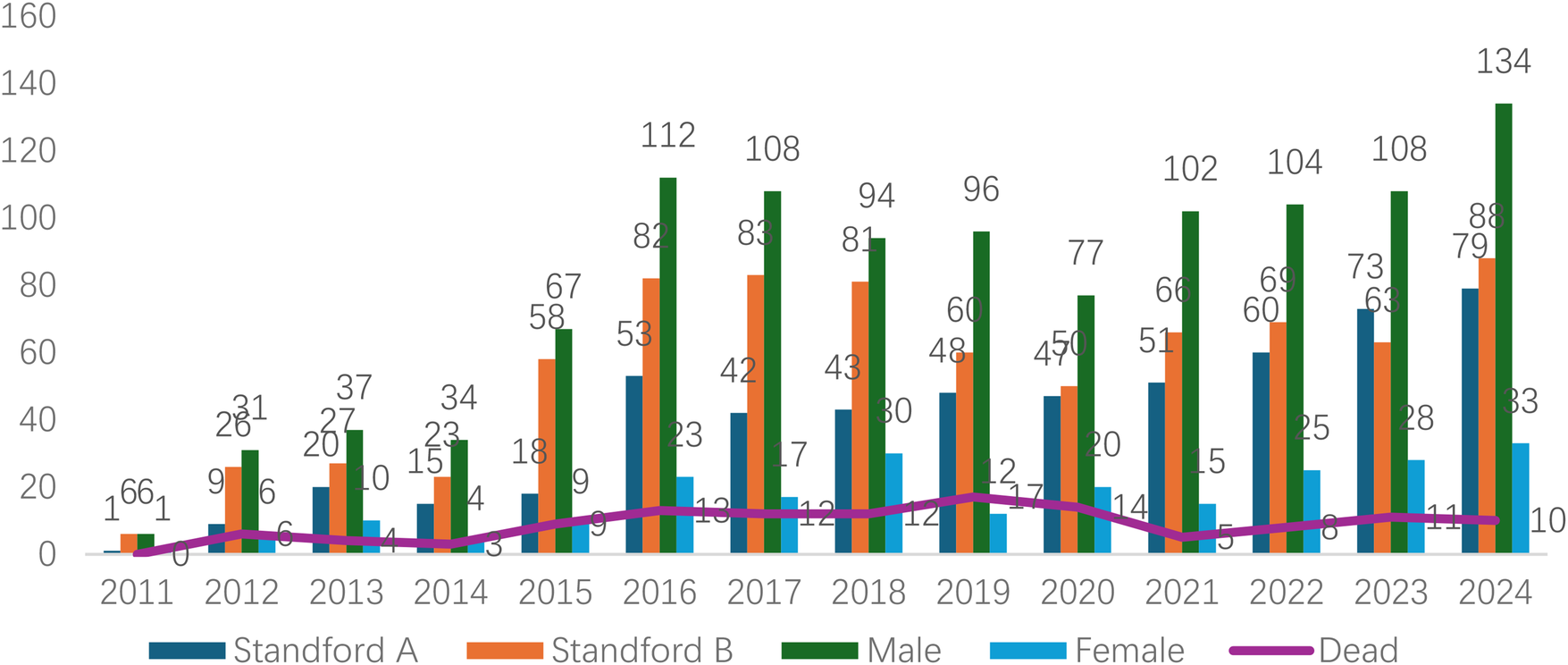

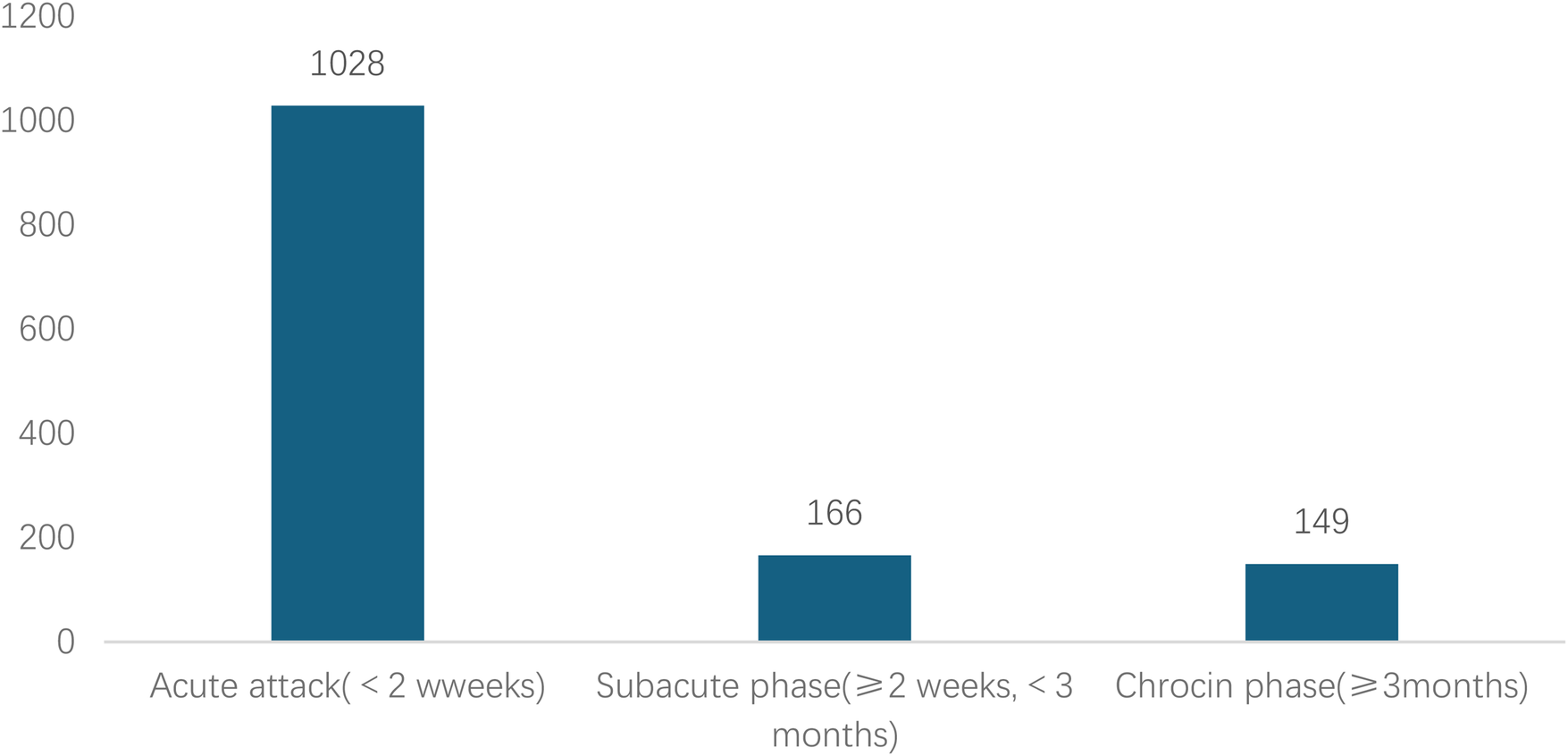

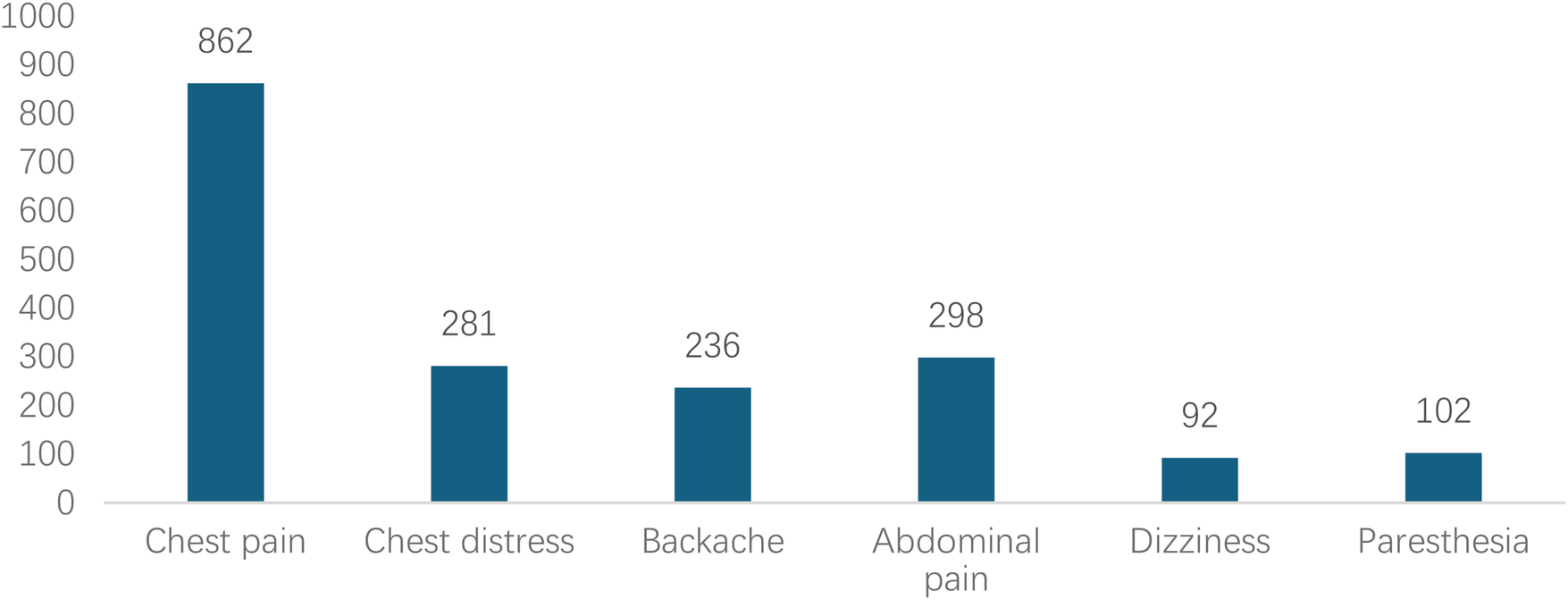

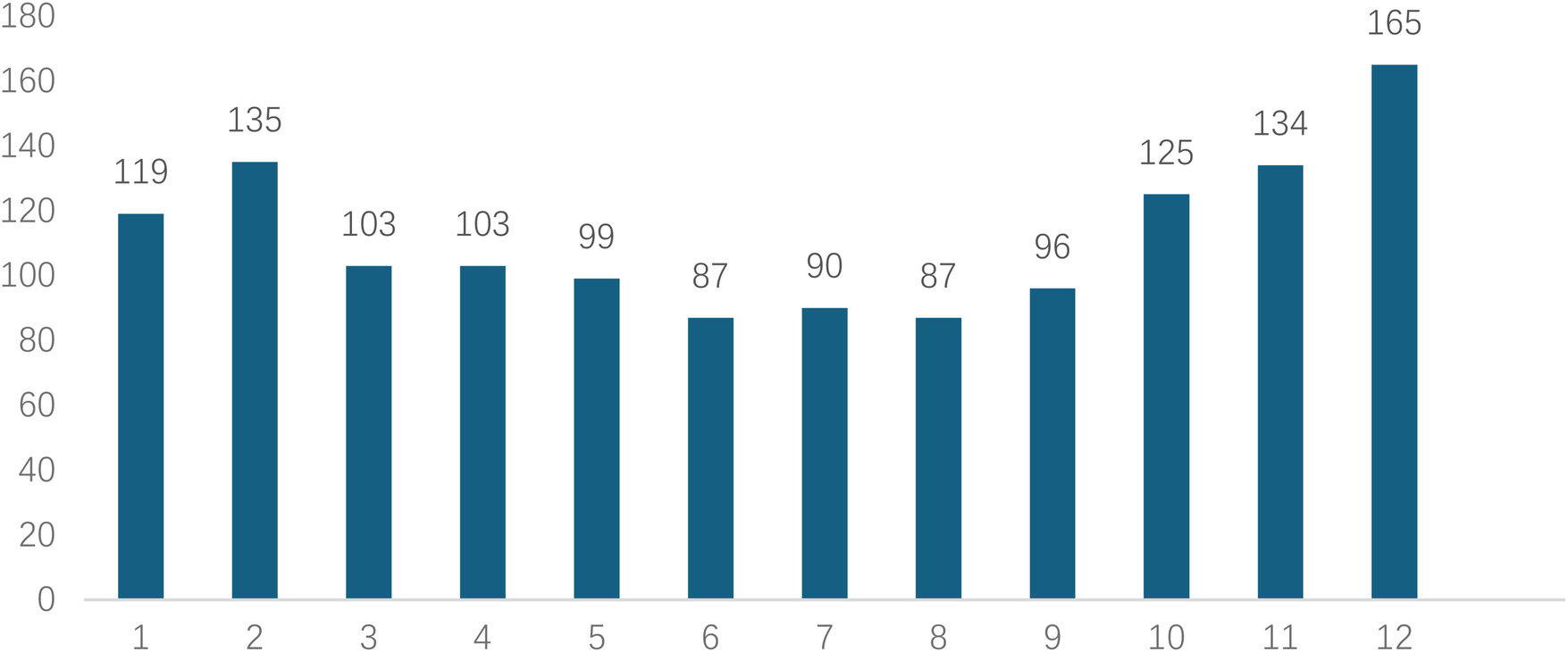

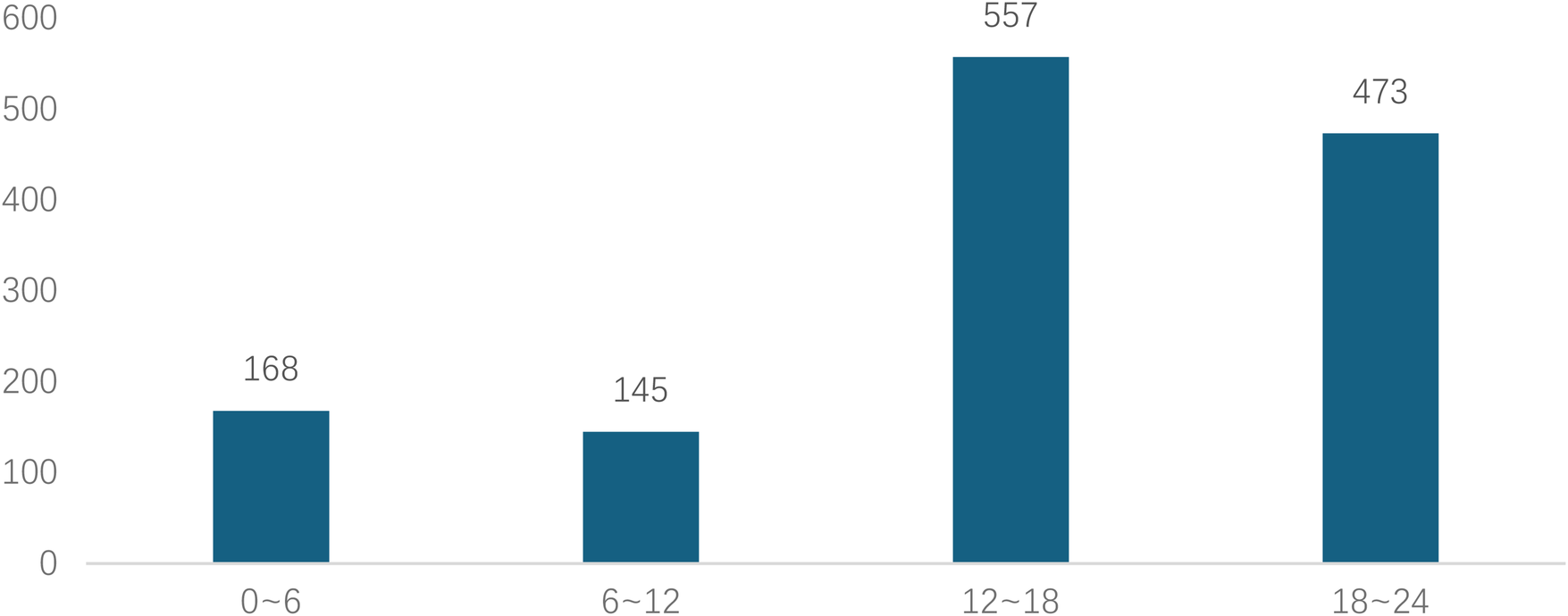

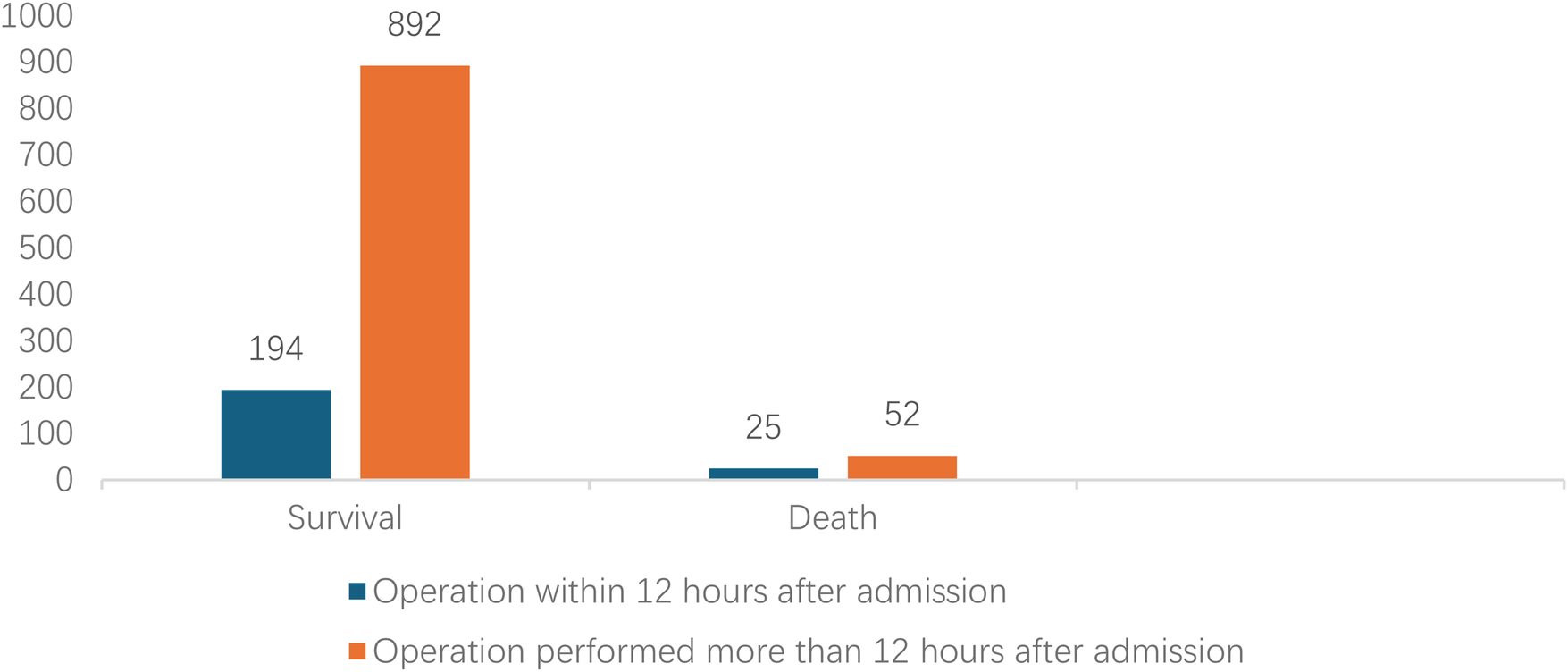

Analyzed in 5-year intervals: The overall number of AD cases showed an increasing trend from 2010 to 2024, with growth trends observed from 2011 to 2015 and 2021 to 2024, and a slight decline from 2016-2020. The overall mortality rate was maintained below 10% (Figure 3). Mortality rates were 16.9% for type A and 4.0% for type B dissections. The readmission rate post-AD surgery was 7.4% (87/1163). The majority of AD patients presented with acute onset 76.5% (Figure 4). Regarding presenting symptoms, chest pain was most frequent (892, 66.4%), followed by abdominal pain (Figure 5). AD incidence showed a tendency towards winter and spring seasons, peaking in December (Figure 6). The emergency department admitted the highest number of AD patients between 12:00 and 23:00 daily, accounting for 76.6% of all hospitalized cases (Figure 7). Current AD treatments broadly include conservative medical management, endovascular intervention, and open surgical repair. The number of endovascular interventions has steadily increased, accounting for 62% (701/1130) of the 1130 patients who underwent procedures (Figure 8).

Figure 3

Frequency distribution and death trend of AD (A/B) in male and female patients from 2011 to 2024.

Figure 4

Time from symptom onset to hospital visit for patients with AD.

Figure 5

Distribution of chief complaints in patients with AD during their visit.

Figure 6

Monthly distribution of visits for patients with AD.

Figure 7

Time to medical consultation after symptom onset (24-hour system) for patients with AD.

Figure 8

Comparison clinical prognosis of different surgical timing.

3.2 Logistic regression analysis of in-hospital mortality in aortic dissection

Variables included in the analysis were gender, age, chief complaint, past medical history and medication use, imaging features of the dissection, patient vital signs, and treatment method. Univariate logistic regression analysis revealed that acute onset, chest pain, dizziness, conservative management, Stanford type A, faster heart rate, higher systolic blood pressure, higher diastolic blood pressure, larger maximum diameter of the affected vessel, and larger maximum false lumen diameter were significant factors associated with increased in-hospital mortality (P < 0.05). Multivariate logistic regression analysis identified acute onset (<2 weeks) (OR = 3.484), chest pain (OR = 1.658), higher heart rate (OR = 1.016), Stanford type A (OR = 3.959) and larger false lumen diameter (OR = 1.357) as independent risk factors for in-hospital mortality (P < 0.05). Surgical treatment was a protective factor against in-hospital mortality (OR = 0.194) (Table 2).

Table 2

| Variable | Death/total number | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95%CI) | P-value | OR (95%CI) | P-value | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 106/1110 | 1.124 (0.682,1.854) | 0.254 | ||

| Female | 20/233 | Ref. | |||

| Age (year) | |||||

| ∼40 | 28/186 | 1.772 (0.218,14.393) | 0.592 | ||

| 40∼, | 71/797 | 0.978 (0.123,7.750) | 0.983 | ||

| 60∼, | 26/349 | 0.805 (0.099,6.535) | 0.839 | ||

| 80∼ | 1/11 | Ref. | |||

| Chest pain | |||||

| Yes | 99/862 | 2.182 (1.404,3.391) | 0.001 | 1.658 (1.031,2.666) | 0.037 |

| No | 27/481 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Chest distress | |||||

| Yes | 25/281 | 0.929 (0.587,1.470) | 0.754 | ||

| No | 101/1062 | Ref. | |||

| Backache | |||||

| Yes | 17/236 | 1.407 (0.827,2.394) | 0.208 | ||

| No | 109/1107 | Ref. | |||

| Abdominal pain | |||||

| Yes | 22/298 | 1.387 (0.859,2.239) | 0.181 | ||

| No | 104/1045 | Ref. | |||

| Paresthesia | |||||

| Yes | 8/102 | 0.810 (0.384,1.708) | 0.580 | ||

| No | 118/1241 | Ref. | |||

| Dizziness | |||||

| Yes | 3/92 | 0.309 (0.096,0.991) | 0.048 | 0.310 (0.095,1.017) | 0.053 |

| No | 123/1251 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Hypertension | |||||

| Yes | 88/958 | 0.924 (0.619,1.378) | 0.697 | ||

| No | 38/385 | Ref. | |||

| Diabetes | |||||

| Yes | 8/62 | 1.460 (0.679,3.142) | 0.333 | ||

| No | 118/1281 | Ref. | |||

| Smoking | |||||

| Yes | 56/644 | 0.856 (0.592,1.238) | 0.408 | ||

| No | 70/699 | Ref. | |||

| Drinking | |||||

| Yes | 53/581 | 0.947 (0.653,1.374) | 0.776 | ||

| No | 73/762 | Ref. | |||

| Coronary heart disease | |||||

| Yes | 8/92 | 0.914 (0.432,1.935) | 0.815 | ||

| No | 118/1251 | Ref. | |||

| Symptom onset time | |||||

| <2 weeks | 107/1028 | 4.211 (1.529,11.602) | 0.005 | 3.486 (1.190,10.209) | 0.023 |

| ≥2 weeks, <3 months | 15/166 | 3.601 (1.168,11.105) | 0.026 | 3.110 (0.945,10.236) | 0.062 |

| ≥3months | 4/149 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Heart rate (bpm) | 84 ± 16 | 1.016 (1.006,1.027) | 0.002 | 1.017 (1.006,1.029) | 0.003 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 145 ± 25 | 0.989 (0.982,0.997) | 0.005 | 0.999 (0.988,1.009) | 0.798 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 83 ± 16 | 0.980 (0.968,0.991) | 0.000 | 0.993 (0.977,1.010) | 0.416 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.8 (22.6,26.6) | 0.982 (0.940,1.026) | 0.422 | ||

| Stanford Type | |||||

| A | 95/560 | 4.956 (3.251,7.555) | 0.000 | 3.959 (2.484,6.308) | 0.000 |

| B | 31/783 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Maximum diameter of diseased blood vessels (cm) | 4.2 ± 1.2 | 1.157 (1.011,1.325) | 0.034 | 0.913 (0.739,1.127) | 0.397 |

| Maximum diameter of false lumen (cm) | 2.2 ± 0.9 | 1.247 (1.064,1.461) | 0.006 | 1.357 (1.064,1.732) | 0.014 |

| Size of interlayer rupture (cm) | 1.2 ± 0.5 | 1.153 (0.850,1.564) | 0.359 | ||

| 50% thrombosis in the false lumen of the sandwich | |||||

| Yes | 18/286 | 0.590 (0.352,0.990) | 0.046 | 0.625 (0.356,1.095) | 0.101 |

| No | 108/1057 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Aortic vascular calcification | |||||

| Yes | 75/861 | 0.806 (0.554,1.173) | 0.806 | ||

| No | 51/282 | Ref. | |||

| Aortic dissection with ≥ 2 false lumens | |||||

| Yes | 19/186 | 1.116 (0.667,1.868) | 0.675 | ||

| No | 107/1157 | Ref. | |||

| Aortic dissection with ≥ 2 ruptures | |||||

| Yes | 18/177 | 1.109 (0.655,1.877) | 0.700 | ||

| No | 108/1166 | Ref. | |||

| Surgery | |||||

| Yes | 77/1163 | 0.190 (0.127,0.282) | 0.000 | 0.194 (0.125,0.301) | 0.000 |

| No | 49/180 | Ref. | Ref. | ||

Logistic regression analysis of factors related to aortic dissection mortality from 2011 to 2024.

4 Discussion

This study analyzed clinical data from 1,343 AD patients over 14 years, systematically elucidating the epidemiological characteristics, clinical features, temporal distribution patterns, evolution of treatment strategies, and independent risk factors for in-hospital mortality. It is representative among similar domestic single-center studies, and its findings have significant implications for understanding the disease burden of AD in the Chinese population, optimizing clinical management pathways, and improving patient outcomes.

A direct comparison of our findings with data from large multinational registries, most notably the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD), reveals both important consistencies and distinct regional characteristics. Demographically, our cohort was notably younger (mean age 52.7 years) than typical IRAD populations (mean age in the mid-60 s) and had a more pronounced male predominance (M:F ratio 4.76:1 vs. approximately 2:1 in IRAD) (11–13). While hypertension remains the paramount risk factor across all studies, its prevalence and potentially differing control rates may contribute to the earlier disease onset observed in our setting, alongside other population-specific risk factor profiles and potential genetic or environmental influences (2, 13, 14). Regarding management, the significant shift toward thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR), which accounted for 62% of procedures in our study, aligns with the global trend toward endovascular-first strategies for Stanford type B dissections, as reflected in recent IRAD analyses and guideline recommendations (5, 15). However, the specific rates of surgical versus non-surgical treatment for Stanford type A dissections may vary based on regional expertise and patient selection criteria. In terms of outcomes, the markedly higher in-hospital mortality for Stanford type A (16.9%) compared to Stanford type B (4.0%) dissection is a universal finding, starkly illustrated by IRAD data which reports a mortality of 1%–2% per hour early in Stanford type A dissection (12). Our overall mortality rate of 10.0% and the pattern of risk factors (e.g., Stanford type A classification, larger false lumen diameter) are consistent with the core lessons from international registries (6). The lower mortality for Stanford type B dissection in our cohort may be associated with the high rate of timely TEVAR, underscoring the impact of evolving treatment paradigms on prognosis.

Our results both align with and diverge from patterns reported in major international registries such as IRAD, highlighting population-specific characteristics. For instance, consistent with IRAD, we identified hypertension as the predominant risk factor and Stanford Type A dissection as a major driver of mortality (11, 12). However, our cohort was notably younger (mean age 52.7 vs. mid-60s in IRAD) and had a higher male preponderance (M:F 4.76:1 vs. ∼2:1), underscoring potential differences in risk factor exposure, genetics, or healthcare-seeking behavior in our region (13). The higher incidence in males may be related to hormonal levels (promoting vascular pathological remodeling) and higher exposure rates to factors like smoking and alcohol consumption (14). Hypertension was the most prominent comorbidity in this cohort (71.3%), highlighting uncontrolled hypertension as the most important preventable and controllable risk factor for AD in the Chinese population. Persistent hypertension exerts significant mechanical stress on the aortic wall, leading to medial elastic fiber fragmentation and smooth muscle cell loss, predisposing it to tear under specific triggers (16, 17), Consistent with domestic studies (18), history of hypertension was significantly associated with Stanford classification (p < 0.001). Although the proportion of hypertension was slightly lower in Stanford type A than Stanford type B patients, the absolute number remains substantial, suggesting that strict blood pressure control is the cornerstone of AD primary prevention, regardless of type. Furthermore, smoking history (48%) and heavy alcohol consumption history (43.3%) were significant concomitant risk factors, likely acting synergistically with hypertension by accelerating atherosclerosis and directly damaging vascular endothelium to promote AD occurrence (19). In contrast, the prevalence of diabetes (4.6%) and coronary artery disease (6.9%) was lower, consistent with the pathophysiological mechanism of AD being primarily mechanical damage to the vessel wall rather than atherothrombotic occlusion (20, 21).

Consistent with literature (22, 23), chest pain (66.4%) was the core clinical symptom. Notably, over 30% of patients presented with atypical symptoms such as abdominal pain, back pain, or even lower limb paresthesia, which can easily lead to misdiagnosis, delayed treatment, and missed opportunities for intervention. Multivariate logistic analysis further confirmed that presentation with chest pain was an independent risk factor for in-hospital mortality (OR = 1.658, p = 0.037). This might be because chest pain is more frequently associated with the more lethal Stanford type A dissection, and its severity reflects the acuity and seriousness of the tearing process. The proportions of Stanford type A and B dissections were 41.7% and 58.3%, respectively, aligning with some large domestic and international studies (24). Stanford type A patients were younger on average (51.06 vs. 53.90 years, p < 0.001), suggesting that younger individuals with inherent wall defects (e.g., genetic disorders like Marfan syndrome) or more dramatic blood pressure fluctuations might be more susceptible to dissections involving the ascending aorta, which are also more perilous (25).

AD incidence exhibited distinct “dual-peak” distributions: a seasonal peak in winter (culminating in December) and a diurnal peak from noon to night (12:00–23:00, accounting for 76.6%). Temperature drops in winter cause peripheral vasoconstriction, potentially leading to sudden blood pressure surges and increased aortic wall stress (26, 27).The diurnal peak likely correlates with the circadian rhythm of blood pressure (typically higher in the morning and afternoon) and daytime triggers like physical activity and emotional stress (28). These findings suggest that emergency departments should maintain heightened vigilance for AD during these peak periods and seasons, and relevant teams should be prepared for urgent responses. Endovascular intervention (Thoracic Endovascular Aortic Repair; TEVAR) has become the predominant treatment, accounting for 62% (701/1130) of procedures. This aligns with global trends in vascular surgery techniques and is often the preferred treatment for complicated Stanford type B dissections (15). In contrast, this study revealed that the mortality rate of Stanford type B dissection was significantly lower than that of Stanford type A (4% vs. 16.9%).

Multivariate analysis strongly confirmed that surgical treatment served as a protective factor, significantly reducing the risk of death by 80.6% (OR = 0.194, p < 0.001), while non-surgical treatment was associated with high risk. Through univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis, we accurately identified independent risk factors influencing in-hospital mortality in AD patients, which is crucial for clinical risk stratification and prognosis evaluation. Among patients with aortic dissection, the surgical mortality rate during the acute phase was significantly higher than that in the subacute phase. This difference may stem from the pathological features of acute dissection, such as the risk of rapidly progressing tears, susceptibility to organ ischemia or rupture, leading to poorer postoperative outcomes (29). Stanford type A dissections readily involve the pericardium (causing cardiac tamponade), coronary arteries (causing myocardial infarction), aortic valve (causing acute heart failure), and brachiocephalic vessels (causing stroke). Their natural history is extremely perilous, with mortality increasing by 1%–2% per hour within the first 24 hours (12). This result re-emphasizes that for Stanford type A dissection, emergency surgical repair must be organized without delay upon diagnosis; any delay can be fatal. Heart rate is a composite indicator reflecting pain, anxiety, and potential hypovolemia (due to hemorrhage). Sustained tachycardia signifies extreme sympathetic activation, indicating unstable conditions and higher risk of cardiovascular events (30). A large false lumen diameter implies more extensive thrombus formation, more severe true lumen compression and organ mal-perfusion, and also reflects potentially wider tear extent and more severe compromise of aortic wall integrity, increasing the risk of rupture (31).

5 Limitations and future directions

This study has several limitations. First, its single-center, retrospective design inherently carries risks of selection bias and information bias. The patient population and treatment patterns may reflect the specific referral patterns, clinical expertise, and institutional protocols of our center, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other healthcare settings. Second, detailed information such as specific types of antihypertensive medications and pre-admission blood pressure control levels were not extensively collected and analyzed. Finally, this study lacks long-term follow-up data. Therefore, our analysis and conclusions are necessarily confined to in-hospital mortality and complications. We cannot draw inferences regarding long-term survival, re-intervention rates, disease progression, or quality of life beyond the index hospitalization. This limits the comprehensive assessment of the comparative long-term efficacy of different treatment strategies. Future research efforts could focus on: (1) Establishing multicenter, prospective AD registry studies incorporating more detailed variables; (2) Further exploring optimized strategies and perioperative management for type A dissection surgery to further reduce its mortality; (3) Conducting follow-up studies on mid- to long-term complications after TEVAR.

6 Conclusion

As a large single-center study from a tertiary cardiovascular hospital in China, the patient population, management protocols, and outcomes may reflect local practices and patient demographics. Therefore, the generalizability of our specific findings, particularly regarding treatment trends and mortality rates, to other regions or healthcare systems should be interpreted with appropriate caution.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by First Affiliated Hospital Of Guangxi Medical University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

YX: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CqH: Writing – review & editing. CyH: Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. YW: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. YL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. RW: Software, Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. GL: Data curation, Methodology, Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This research was supported by the Guangxi Clinical Key Specialty – Emergency Nursing Fund (QTKT20253792).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcvm.2026.1706284/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Chen D Fang K Luo M Xiao Y Zhao Y Shu C . Aortic dissection incidence and risk factor analysis: findings from the China Kadoorie biobank. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. (2025) 69(4):611–618. 10.1016/j.ejvs.2024.12.003

2.

Hibino M Otaki Y Kobeissi E et al Blood pressure, hypertension, and the risk of aortic dissection incidence and mortality: results from the J-SCH study, the UK biobank study, and a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Circulation. (2022) 145(9):633–644. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.056546

3.

Hibino M Verma S Jarret CM et al Temporal trends in mortality of aortic dissection and rupture in the UK, Japan, the USA and Canada. Heart. (2024) 110(5):331–336. 10.1136/heartjnl-2023-323042

4.

Isselbacher EM Preventza O Hamilton BJR et al 2022 ACC/AHA guideline for the diagnosis and management of aortic disease: a report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. (2022) 146(24):e334–e482. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001106

5.

Mazzolai L Teixido-Tura G Lanzi S et al 2024 Esc guidelines for the management of peripheral arterial and aortic diseases. Eur Heart J. (2024) 45(36):3538–3700. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehae179

6.

Bossone E Eagle KA Nienaber CA et al Acute aortic dissection: observational lessons learned from 11 000 patients. Circulation. (2024) 17(9):123–7. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.123.010673

7.

Lin XF Gao HQ Wu QS Xie YL Chen LW Xie LF . Validation of the GERAADA score for predicting 30-day mortality rate in acute type A aortic dissection: a single-center study in China. J Am Heart Assoc. (2025) 14(17):e040838. 10.1161/JAHA.125.040838

8.

Evangelista A Sitges M Jondeau G et al Multimodality imaging in thoracic aortic diseases: a clinical consensus statement from the European association of cardiovascular imaging and the European Society of Cardiology working group on aorta and peripheral vascular diseases. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. (2023) 24(5):e65–e85. 10.1093/ehjci/jead024

9.

Lauder L Weber T Böhm M et al European guidelines for hypertension in 2024: a comparison of key recommendations for clinical practice. Nat Rev Cardiol. (2025) 22(9):675–688. 10.1038/s41569-025-01187-2

10.

Brockamp C Landgraf R Muller UA Muller-Wieland D Petrak F Uebel T . Clinical practice guideline: shared decision making, diagnostic evaluation, and pharmacotherapy in type 2 diabetes. Dtsch Arztebl Int. (2023) 120(47):804–10. 10.3238/arztebl.m2023.0219

11.

Carbone A Ranieri B Castaldo R et al Sex differences in type A acute aortic dissection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol. (2023) 30(11):1074–1089. 10.1093/eurjpc/zwad009

12.

Harris KM Nienaber CA Peterson MD . Early mortality in type A acute aortic dissection insights from the international registry of acute aortic dissection. JAMA Cardiol. (2022) 7(10):1009–1015. 10.1001/jamacardio.2022.2718

13.

Huckaby LV Sultan I Trimarchi S . Sex-based aortic dissection outcomes from the international registry of acute aortic dissection. Ann Thorac Surg. (2022) 113(2):498–505. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2021.03.100

14.

Crousillat D Briller J Aggarwal N et al Sex differences in thoracic aortic disease and dissection: JACC review topic of the week. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2023) 82(9):817–827. 10.1016/j.jacc.2023.05.067

15.

Hellgren T Beck AW Behrendt CA et al Thoracic endovascular aortic repair practice in 13 countries: a report from VASCUNET and the international consortium of vascular registries. Ann Surg. (2022) 276(5):e598–e604. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004561

16.

Shahbad R Kamenskiy A Razian SA Jadidi M Desyatova A . Effects of age, elastin density, and glycosaminoglycan accumulation on the delamination strength of human thoracic and abdominal aortas. Acta Biomater. (2024) 189:413–426. 10.1016/j.actbio.2024.10.010

17.

Sun C Qin T Kalyanasundaram A Elefteriades J Sun W Liang L . Biomechanical stress analysis of type-A aortic dissection at pre-dissection, post-dissection, and post-repair states. Comput Biol Med. (2025) 184:109310. 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2024.109310

18.

Jihong Z Liwen D Weibo G et al The impact of hypertension on the prognosis of acute aortic dissection. Chin J Emerg Med. (2019) 28(5):614–18. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-0282

19.

Rodrigues BJ Meester J Luyckx I Peeters S Verstraeten A Loeys B . The genetics and typical traits of thoracic aortic aneurysm and dissection. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. (2022) 23:223–253. 10.1146/annurev-genom-111521-104455

20.

Jiang H Zhao Y Jin M et al Colchicine inhibits smooth muscle cell phenotypic switch and aortic dissection in mice-brief report. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. (2025) 45(6):979–984. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.124.322252

21.

Li S Fu W Wang L . Role of macrophages in aortic dissection pathogenesis: insights from preclinical studies to translational prospective. Sci China Life Sci. (2024) 67(11):2354–2367. 10.1007/s11427-024-2693-5

22.

Liu WT Lin CS Tsao TP et al A deep-learning algorithm-enhanced system integrating electrocardiograms and chest x-rays for diagnosing aortic dissection. Can J Cardiol. (2022) 38(2):160–68. 10.1016/j.cjca.2021.09.028

23.

Ziya X Chenling Y Guorong G et al Clinical characteristics and prognosis analysis of 580 patients with aortic dissection. Chin J Emerg Med. (2016) 25(2):644–9. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-0282

24.

Campia U Rizzo SM Snyder JE et al Impact of atrial fibrillation on in-hospital mortality and stroke in acute aortic syndromes. Am J Med. (2021) 134(11):1419–1423. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2021.06.012

25.

Holmes KW Markwardt S Eagle KA et al Cardiovascular outcomes in aortopathy: genTAC registry of genetically triggered aortic aneurysms and related conditions. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2022) 79(21):2069–2081. 10.1016/j.jacc.2022.03.367

26.

Chen J Gao Y Jiang Y et al Low ambient temperature and temperature drop between neighbouring days and acute aortic dissection: a case-crossover study. Eur Heart J. (2022) 43(3):228–235. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab803

27.

Kato K Nishino T Otsuka T Seino Y Kawada T . Nationwide analysis of the relationship between low ambient temperature and acute aortic dissection-related hospitalizations. Eur J Prev Cardiol. (2025) 32(4):317–324. 10.1093/eurjpc/zwae278

28.

Gumz ML Shimbo D Abdalla M et al Toward precision medicine: circadian rhythm of blood pressure and chronotherapy for hypertension - 2021 NHLBI workshop report. Hypertension. (2023) 80(3):503–522. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.122.19372

29.

Xie E Yang F Liu Y et al Timing and outcome of endovascular repair for uncomplicated type B aortic dissection. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. (2021) 61(5):788–797. 10.1016/j.ejvs.2021.02.026

30.

Hendriks PM van den Bosch AE Kors JA et al Heart rate: an accessible risk indicator in adult congenital heart disease. Heart. (2024) 110(6):402–407. 10.1136/heartjnl-2023-323233

31.

Filiberto AC Novak Z Azizzadeh A et al Outcomes of high risk and complicated type B aortic dissections treated with thoracic endovascular aortic repair. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. (2025) 70(2):229–236. 10.1016/j.ejvs.2025.04.023

Summary

Keywords

aortic dissection, epidemiology, in-hospital mortality, risk factors, Stanford classification

Citation

Xu Y, Huang C, Huang C, Wang Y, Luo Y, Wei R and Liang G (2026) Analysis of epidemiological characteristics and prognosis based on 1,343 cases of aortic dissection from a regional single center. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 13:1706284. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2026.1706284

Received

16 September 2025

Revised

12 January 2026

Accepted

21 January 2026

Published

06 February 2026

Volume

13 - 2026

Edited by

Massimo Bonacchi, University of Florence, Italy

Reviewed by

Vladimir Uspenskiy, Almazov National Medical Research Centre, Russia

Jianjian Sun, East China Normal University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Xu, Huang, Huang, Wang, Luo, Wei and Liang.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Yansong Xu hbxys81@163.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.