Abstract

Introduction:

Drug-coated balloons (DCBs) constitute a vital therapeutic approach in the interventional management of coronary heart disease. Nevertheless, the risk factors for predicting target lesion revascularization (TLR) and major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) specifically within the elderly population following DCB angioplasty remain incompletely understood. The study is to explore the relationship between estimated pulse wave velocity (ePWV) values and the risk of TLR and MACE in elderly patients undergoing DCB treatment, and to explore the optimal ePWV cutoff for clinical risk stratification.

Methods:

A total of 423 participants were stratified into quartiles based on their ePWV values. Baseline characteristics were compared among these quartiles. The associations between ePWV and the risk of TLR and MACE were evaluated using Cox regression models, adjusted for multiple covariates. Kaplan–Meier analysis with the log-rank test was utilized to assess survival differences. The optimal ePWV cutoff for risk stratification was identified through maximally selected rank statistics. Subgroup analyses were performed to examine interactions between ePWV and clinical variables.

Results:

Differences emerged across ePWV quartiles for age, TLR, and MACE (all P < 0.05). Multivariate Cox regression revealed that elevated ePWV was associated with a higher risk of TLR (per unit increase: adjusted HR 1.46, 95% CI 1.18–1.79, P < 0.001) and MACE. A dose-response relationship was observed, with the highest ePWV quartile exhibiting the highest risk compared to the lowest. Kaplan–Meier curves showed differences in survival across quartiles (TLR: log-rank P = 0.012; MACE: P < 0.05). The optimal ePWV cutoff was identified at 10.91 m/s, differentiating high- and low-risk groups (log-rank P < 0.05). Notably, subgroup analysis revealed sex-based interactions for both TLR and MACE, with the predictive value being consistently more pronounced in females.

Conclusion:

Elevated ePWV was associated with a higher risk of TLR and MACE. An exploratory cutoff for ePWV at 10.91 m/s was identified, stratifying patients into distinct clinical risk groups.

Introduction

Coronary artery disease (CAD) continues to be the primary cause of global mortality, with its impact intensified by aging populations and increasing rates of metabolic risk factors (1). Endovascular therapy, especially utilizing drug-coated balloons (DCBs), has transformed CAD management by lowering restenosis rates and enhancing long-term patency, particularly in complex lesions (e.g., small vessels, in-stent restenosis) (2–5). DCB technology facilitates effective revascularization and reduces the duration of dual antiplatelet therapy (4), which is especially crucial for elderly patients at high risk of bleeding, those with abnormal glucose metabolism, or those experiencing acute coronary syndrome.

Arterial stiffness, a critical mediator in CAD progression, reflects profound structural and functional alterations within the vascular wall, preceding the development of subclinical dysfunction (6). Furthermore, it can also serve as a predictive factor for in-stent restenosis (7, 8). Traditionally assessed via pulse wave velocity (PWV), the gold standard for gauging stiffness, its clinical application faces hurdles due to high costs and technical demands (9). Estimated PWV (ePWV), derived from readily accessible parameters like age and mean blood pressure, offers a low-cost, non-invasive alternative. It demonstrates a correlation with measured PWV and carries proven prognostic significance in CAD (10–12).

Recent studies demonstrate that ePWV stands out as a predictor of all-cause mortality in CAD patients, exhibiting a striking threshold effect. Once ePWV exceeds 11.15 m/s, the risk rises (10). Importantly, the success of DCB treatment is heavily contingent upon vascular physiology. Post-procedural hemodynamics, lesion calcification, and systemic vascular dysfunction are all established drivers of target lesion revascularization (TLR) and major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) (13). Given that ePWV provides a direct measure of systemic arterial stiffness, a fundamental upstream driver of vascular dysfunction, it follows that ePWV is a promising predictor of responses to DCB treatment in CAD. Nevertheless, concrete evidence directly linking ePWV to DCB outcomes remains sparse.

This study examines and contextualizes the relationship between ePWV and DCB therapy outcomes in CAD. We explore the correlation between arterial stiffness, assessed by ePWV, and DCB treatment outcomes, while also highlighting critical research gaps and charting future directions.

Methods

Study population

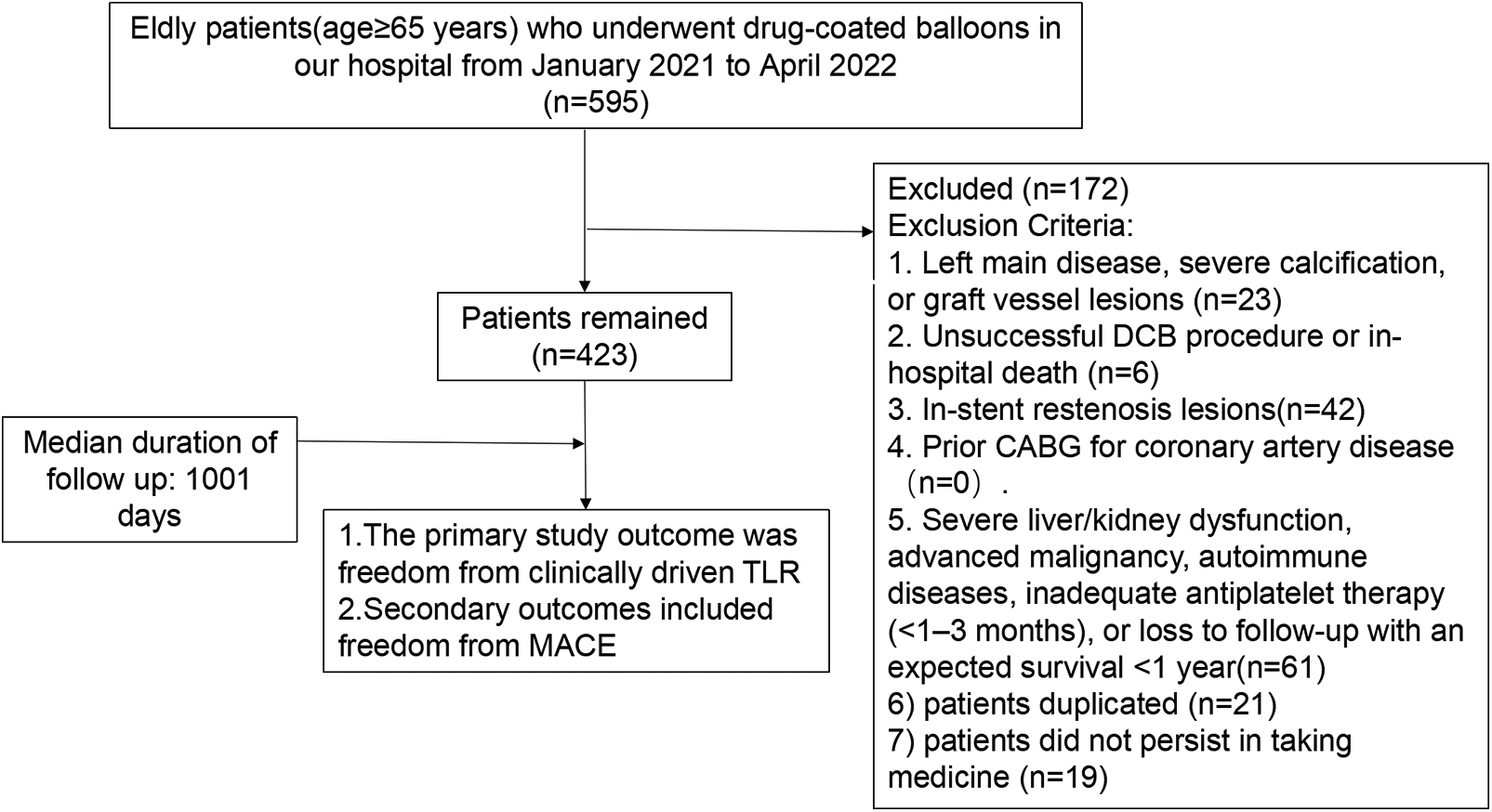

This retrospective observational study enrolled 423 elderly patients (aged ≥65 years) with de novo coronary artery lesions who underwent drug-coated balloon (DCB) treatment between January 2021 and June 2022. The inclusion criteria comprised meeting the indications for DCB treatment (14), achieving a TIMI flow grade of III post-angioplasty without type C or higher dissection, lesions amenable to complete coverage by a single DCB, and the availability of comprehensive clinical data. Key exclusion criteria included left main disease, severe calcification, or graft vessel lesions; an unsuccessful DCB procedure or in-hospital mortality; in-stent restenosis lesions; a history of CABG; severe liver/kidney dysfunction, advanced malignancy, autoimmune diseases, inadequate antiplatelet therapy (<1–3 months), loss to follow-up, or an expected survival of less than one year. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University (Approval No.: XYFY2022-KL242-01). This study is an unregistered retrospective study and included a data availability statement. The flow chart for this study is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Flow chart of our study.

DCB intervention procedure

The lesion preparation process adhered to standardized protocols (13), which included pre-dilating with conventional balloons (at a balloon-to-artery ratio of 0.8-1.0. Cutting balloons were employed when necessary to minimize the risk of dissection. Paclitaxel-iopromide DCB angioplasty was performed using either a Jetsail Drug-Coated Balloon (MicroPort Medical, Shanghai, China) or a Sily Drug-Coated Balloon (Yinyi Biotech, Suzhou, China), inflated to the manufacturer's recommended pressure and maintained for 60 seconds. Procedural success was defined as achieving a TIMI flow grade III, with residual stenosis ≤30%, and no dissection. Bailout stenting was conducted if these criteria were not met. All patients received dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT: aspirin + P2Y12 inhibitor) for a minimum of three months post-procedure, followed by single antiplatelet therapy. Systematically, guideline-recommended secondary prevention medications were adhered to.

Calculation of ePWV

ePWV was calculated according to the formula validated for populations with major clinical risk factors, as established by the Reference Values for Arterial Stiffness Collaboration (15). Since all participants in this study were patients with coronary heart disease, the following equation was used (16, 17):[where MBP = DBP + 0.4 × (SBP - DBP); SBP = systolic blood pressure, DBP = diastolic blood pressure].

Follow-Up

Patients were followed at 1, 6, 12, 24, and 36 months post-procedure. Pre-procedure ePWV was measured at rest, repeated every six months in the first year, and annually thereafter. Standardized follow-ups were performed by trained researchers through outpatient visits or telephone interviews. The primary outcome was freedom from clinically driven target lesion revascularization (TLR), defined as reintervention within 5 mm of the original treated segment for >50% angiographic diameter stenosis with symptomatic worsening (18). Secondary outcomes included major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), a composite of cardiac death, non-fatal acute myocardial infarction, and TLR. All events were adjudicated by investigators at participating centers.

Data collection

Demographic, clinical, and laboratory data were collected, including the following demographics: age, sex, smoking status, hypertension, diabetes, and history of stroke or heart failure. Laboratory tests encompassed white blood cell count, C-reactive protein (CRP), mean corpuscular volume, red cell distribution width, alkaline phosphatase, fasting glucose, and lipid profile (total cholesterol, triglycerides, HDL-C, LDL-C). Angiographic data included the number of diseased vessels, lesion location, use of cutting balloon, pre-dilation pressure, and lesion diameter/length. Lesion complexity was quantified using the SYNTAX Score II 2020, retrospectively calculated using the online SYNTAX Score II calculator (19), incorporating key angiographic and clinical parameters. Assessments were performed independently by two cardiologists, with discrepancies resolved by consensus.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range), and categorical variables as frequencies (percentages). Patients were stratified into quartiles based on ePWV values. Baseline characteristics were compared using ANOVA, Kruskal–Wallis, or chi-square tests, as appropriate. Associations between ePWV and risks of TLR and MACE were evaluated using unadjusted and multivariable-adjusted Cox proportional hazards models, with results expressed as hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). The test for trend was performed by entering the quartile rank (1, 2, 3, and 4) as a continuous variable into the Cox regression models. Survival curves were plotted using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared with the log-rank test. The optimal ePWV cutoff for predicting TLR was identified by maximally selected rank statistics. Subgroup analyses were performed to examine interactions between ePWV and key clinical variables. All analyses were conducted using R version 4.3.3 and Zstats 1.0, with a two-sided p-value < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 423 participants were categorized into quartiles based on their ePWV values (Q1-Q4). During the follow-up period, 44 patients (10.40%) experienced target lesion revascularization (TLR), and 54 patients (12.77%) experienced major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), which included 44 cases of TLR, 8 cases of cardiac death, and 2 cases of non-fatal acute myocardial infarction. Significant differences were observed across the quartiles for several key variables. Both systolic and diastolic blood pressure showed progressive increases from the first to the fourth quartile (P < 0.001), as did ePWV values and patient age (P < 0.001). The incidence of TLR and MACE varied among quartiles (P = 0.011 and P = 0.002, respectively), with the lowest rates in the first quartile and the highest in the fourth (Table 1). No significant differences were observed in body surface area (BSA), Syntax score, or most laboratory parameters, as well as in categorical variables such as comorbidities and medication use.

Table 1

| Variables | Q1 (n = 106) | Q2 (n = 105) | Q3 (n = 106) | Q4 (n = 106) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ePWV | 10.47 (10.17,10.73) | 11.39 (11.13,11.65) | 12.32 (12.06,12.45) | 13.58 (13.05,14.24) | <.001 |

| Age, years | 67.00 (66.00,69.00) | 70.00 (67.00,71.00) | 72.00 (69.00,75.00) | 77.00 (74.00,80.75) | <.001 |

| BSA, m2 | 1.66 (1.60,1.70) | 1.65 (1.60,1.70) | 1.65 (1.60,1.70) | 1.64 (1.60,1.69) | 0.128 |

| Male, n (%) | 70 (66.04) | 63 (60.00) | 64 (60.38) | 67 (63.21) | 0.784 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 61 (57.55) | 61 (58.10) | 74 (69.81) | 70 (66.04) | 0.175 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 28 (26.42) | 34 (32.38) | 37 (34.91) | 22 (20.75) | 0.100 |

| Previous stroke, n (%) | 14 (13.21) | 20 (19.05) | 14 (13.21) | 19 (17.92) | 0.521 |

| Previous HF, (%) | 14 (13.21) | 6 (5.71) | 9 (8.49) | 15 (14.15) | 0.146 |

| AF, n (%) | 6 (5.66) | 6 (5.71) | 7 (6.60) | 12 (11.32) | 0.333 |

| Previous PCI, n (%) | 29 (27.36) | 18 (17.14) | 31 (29.25) | 30 (28.30) | 0.153 |

| Smoker, n (%) | 26 (24.53) | 18 (17.14) | 21 (19.81) | 24 (22.64) | 0.573 |

| WBC (*109/L) | 6.25 (5.23,7.38) | 6.20 (5.20,7.00) | 6.10 (5.30,7.20) | 5.80 (5.03,6.60) | 0.242 |

| Mean Cell Volume (fl) | 93.15 (90.53,95.70) | 93.00 (90.70,96.20) | 92.46 (91.00,95.35) | 93.70 (92.03,95.70) | 0.110 |

| Red cell distribution width (%) | 12.90 (12.60,13.28) | 12.80 (12.40,13.20) | 12.91 (12.50,13.20) | 12.82 (12.43,13.20) | 0.625 |

| Hs-CRP (mg/L) | 2.88 (1.38,7.91) | 2.95 (1.45,7.10) | 2.55 (0.90,6.36) | 2.50 (0.93,6.22) | 0.707 |

| ALP (U/L) | 72.00 (65.00,85.00) | 76.00 (63.00,88.00) | 78.98 (63.00,86.81) | 76.32 (65.50,85.75) | 0.544 |

| Serum creatinine (umol/L) | 66.00 (55.00,75.00) | 64.00 (55.00,72.00) | 65.86 (59.01,72.75) | 67.06 (57.25,78.00) | 0.316 |

| Blood glucose (mmol/L) | 5.55 (4.88,6.25) | 5.61 (5.06,7.01) | 5.68 (5.12,6.92) | 5.35 (4.88,6.21) | 0.141 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 3.84 (3.20,4.59) | 4.12 (3.50,4.76) | 4.14 (3.24,4.71) | 4.01 (3.42,4.75) | 0.360 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.40 (1.05,1.82) | 1.38 (1.03,1.94) | 1.34 (0.99,1.73) | 1.35 (0.96,1.67) | 0.667 |

| HDL (mmol/L) | 1.04 (0.87,1.19) | 1.10 (0.90,1.23) | 1.06 (0.92,1.17) | 1.06 (0.93,1.21) | 0.691 |

| LDL (mmol/L) | 2.17 (1.65,2.89) | 2.42 (1.92,3.11) | 2.46 (1.80,3.02) | 2.30 (1.88,3.01) | 0.439 |

| Syntax score | 13.50 (9.00,16.00) | 14.00 (12.00,15.00) | 13.00 (12.00,15.00) | 14.00 (12.00,15.00) | 0.775 |

| Drug ballon diameter (mm) | 2.50 (2.00,2.50) | 2.00 (2.00,2.50) | 2.50 (2.00,2.69) | 2.50 (2.00,2.75) | 0.327 |

| Drug ballon length (mm) | 20.00 (20.00,26.00) | 20.00 (20.00,30.00) | 20.00 (20.00,30.00) | 20.00 (20.00,26.00) | 0.804 |

| Moderate calcification, n (%) | 16 (15.09) | 17 (16.19) | 28 (26.42) | 26 (24.53) | 0.093 |

| Cutting Balloon, n (%) | 64 (60.38) | 61 (58.10) | 62 (58.49) | 66 (62.26) | 0.922 |

| Aspirin, n (%) | 102 (96.23) | 103 (98.10) | 101 (95.28) | 99 (93.40) | 0.416 |

| P2Y12inhibitor, n (%) | 0.837 | ||||

| Clopidogrel, n (%) | 53 (50.00) | 46 (43.81) | 50 (47.17) | 51 (48.11) | |

| Ticagrelor, n (%) | 53 (50.00) | 59 (56.19) | 56 (52.83) | 55 (51.89) | |

| Number of diseased vessels, n (%) | 0.085 | ||||

| 1 | 29 (27.36) | 19 (18.10) | 22 (20.75) | 13 (12.26) | |

| 2 | 30 (28.30) | 45 (42.86) | 40 (37.74) | 47 (44.34) | |

| 3 | 47 (44.34) | 41 (39.05) | 44 (41.51) | 46 (43.40) | |

| TLR, n (%) | 2 (1.89) | 13 (12.38) | 15 (14.15) | 14 (13.21) | 0.011 |

| MACE, n (%) | 3 (2.83) | 13 (12.38) | 18 (16.98) | 20 (18.87) | 0.002 |

Baseline characteristics.

HF, heart failure; MCV, mean cell volume; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; WBC, white blood cell count; RDW, red cell distribution width; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; SCr, serum creatinine; ePWV, estimated pulse wave velocity; TLR, target lesion revascularization; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events.

Bold values indicate statistical significance (P < 0.05).

Variables associated with increased risk of Tlr were analyzed with Cox regression survival analysis

To prevent overfitting given the limited number of events, only variables showing significant associations (P < 0.05) in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate models (Supplementary Tables S1 and S2). Cox regression analysis revealed an association between ePWV and TLR risk, whether analyzed as a continuous variable or categorized by quartiles. Each unit increase in ePWV correlated with heightened TLR risk across all models, exhibiting an adjusted HR of 1.46 (95% CI: 1.18∼1.79; P < 0.001) in the multivariate model. Quartile analysis revealed a pronounced dose-response relationship (P for trend < 0.05), with Q4 exhibiting the highest risk compared to Q1 (Table 2). Similarly associations emerged for MACE, findings across both crude and adjusted models (Table 2).

Table 2A

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95%CI) | P | HR (95%CI) | P | |

| ePWV | 1.43 (1.16∼1.76) | <.001 | 1.46 (1.18∼1.79) | <.001 |

| ePWV quantile | ||||

| Q1 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | ||

| Q2 | 6.83 (1.54∼30.25) | 0.011 | 7.38 (1.66∼32.83) | 0.009 |

| Q3 | 7.78 (1.78∼34.03) | 0.006 | 9.02 (2.03∼40.17) | 0.004 |

| Q4 | 7.63 (1.74∼33.59) | 0.007 | 9.00 (2.02∼40.03) | 0.004 |

| P for trend | 0.007 | 0.002 | ||

Association of ePWV and ePWV quantile with TLR.

HR, Hazard Ratio; CI, Confidence Interval.

Model 1: Crude.

Model 2: P2Y12inhibitor, Moderate calcification, Previous stent, Hs-CRP.

Bold values indicate statistical significance (P < 0.05).

Table 2B

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95%CI) | P | HR (95%CI) | P | |

| ePWV | 1.51 (1.25∼1.82) | <.001 | 1.50 (1.25∼1.80) | <.001 |

| ePWV quantile | ||||

| Q1 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | ||

| Q2 | 4.55 (1.30∼15.98) | 0.018 | 5.77 (1.63∼20.46) | 0.007 |

| Q3 | 6.26 (1.85∼21.27) | 0.003 | 8.14 (2.36∼28.12) | <.001 |

| Q4 | 7.28 (2.16∼24.49) | 0.001 | 8.85 (2.60∼30.19) | <.001 |

| P for trend | <.001 | <.001 | ||

Association of ePWV and ePWV quantile with MACE.

HR, Hazard Ratio; CI, Confidence Interval.

Model 1: Crude.

Model 2: P2Y12inhibitor, Previous stent, Syntax score, Drug ballon diameter, Hs-CRP.

Bold values indicate statistical significance (P < 0.05).

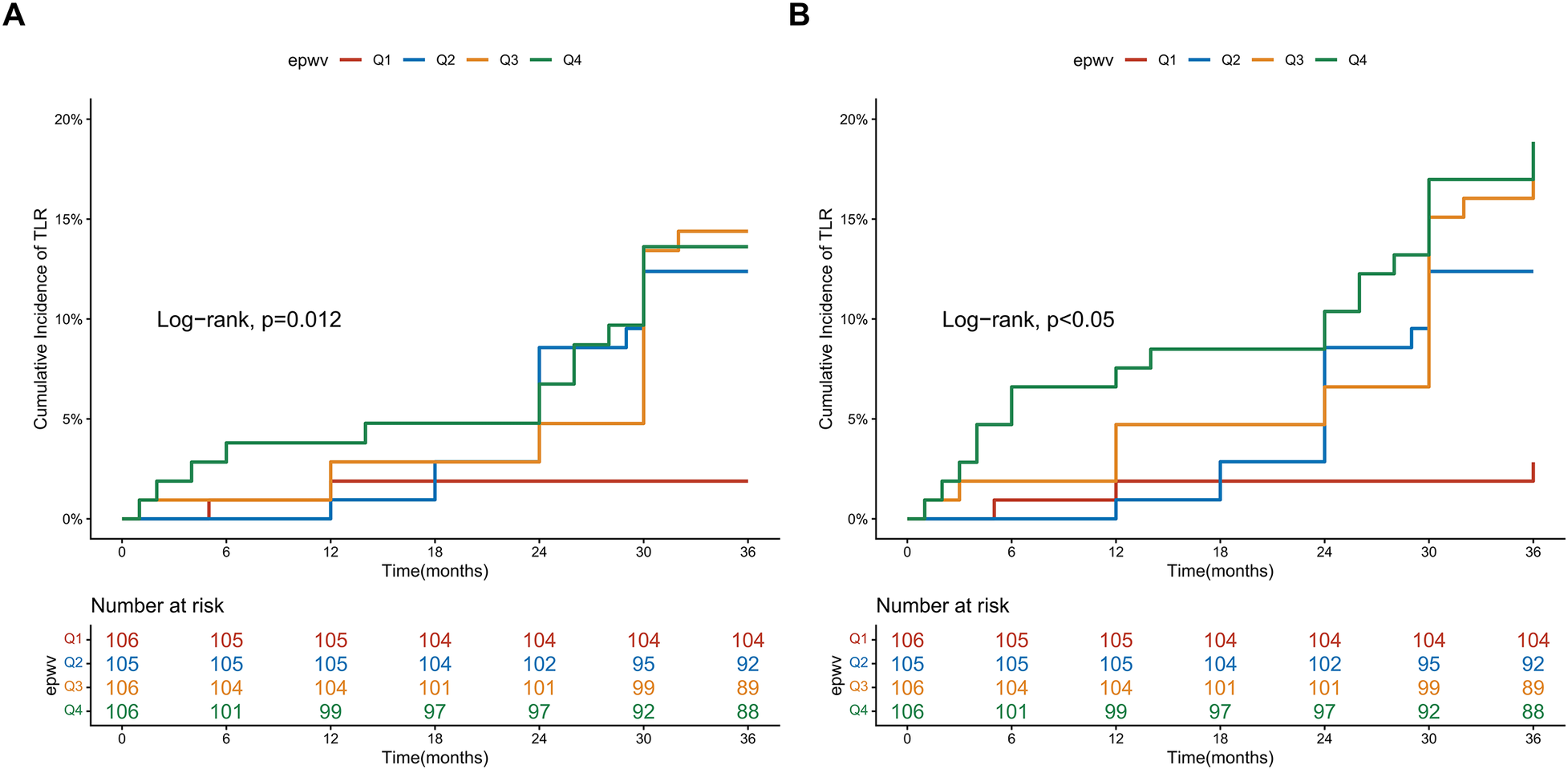

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis by ePWV quartiles

Kaplan–Meier analysis demonstrated differences in TLR-free survival across ePWV quartiles (log-rank test, P = 0.012) (Figure 2A). The Q1 group (lowest ePWV) exhibited the highest survival probability, whereas the Q4 group showed the lowest, with Q2 and Q3 showing intermediate risks. A similar graded pattern was observed for MACE (log-rank test, P < 0.05) (Figure 2B). The observed irregularities and overlapping of survival curves are likely attributable to the limited sample size and number of events in this single-center cohort.

Figure 2

Kaplan–meier survival curves for clinical outcomes stratified by ePWV quartiles. (A) Kaplan–Meier estimates for freedom from TLR; (B) Kaplan–Meier estimates for freedom from MACE.

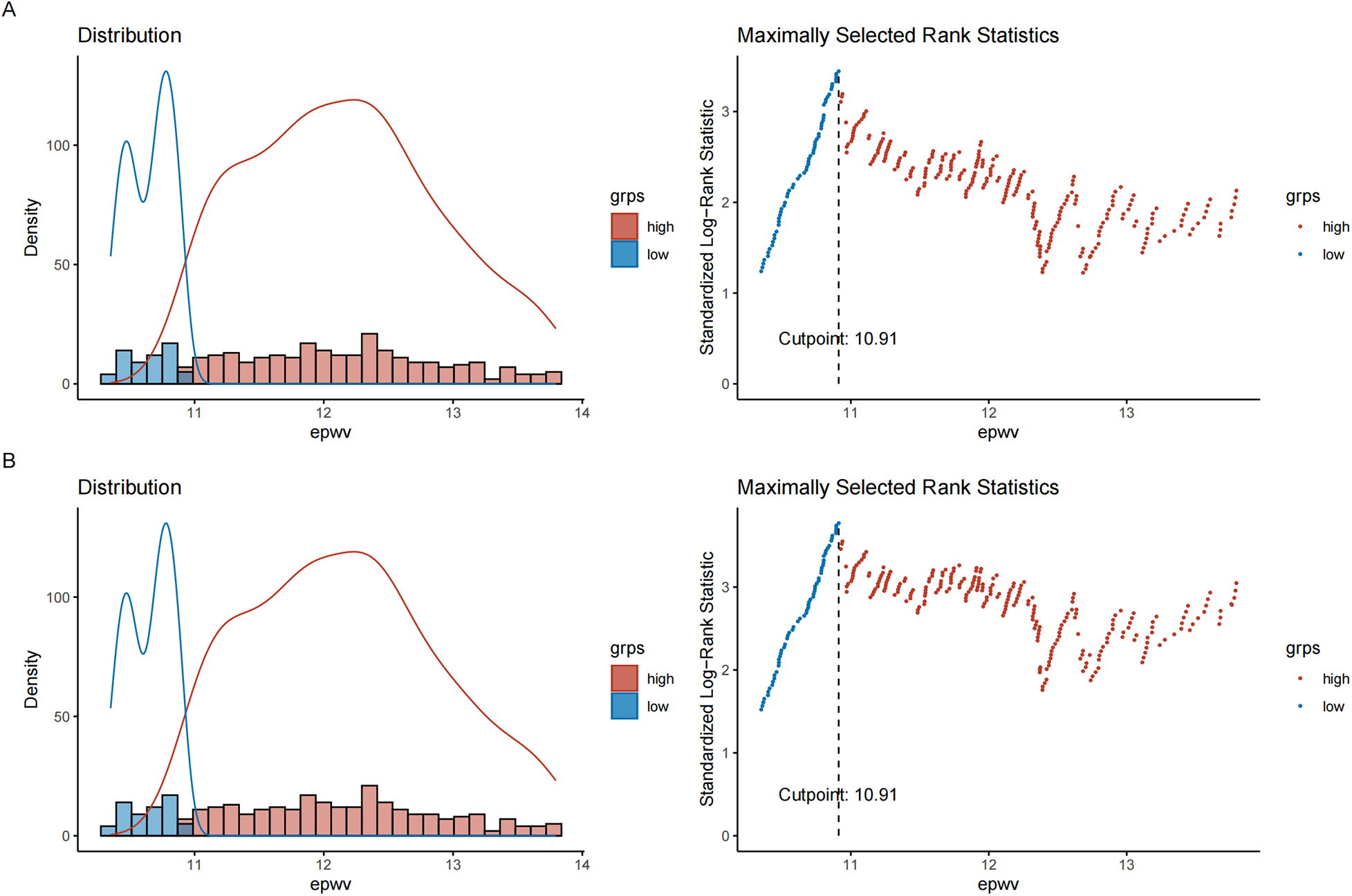

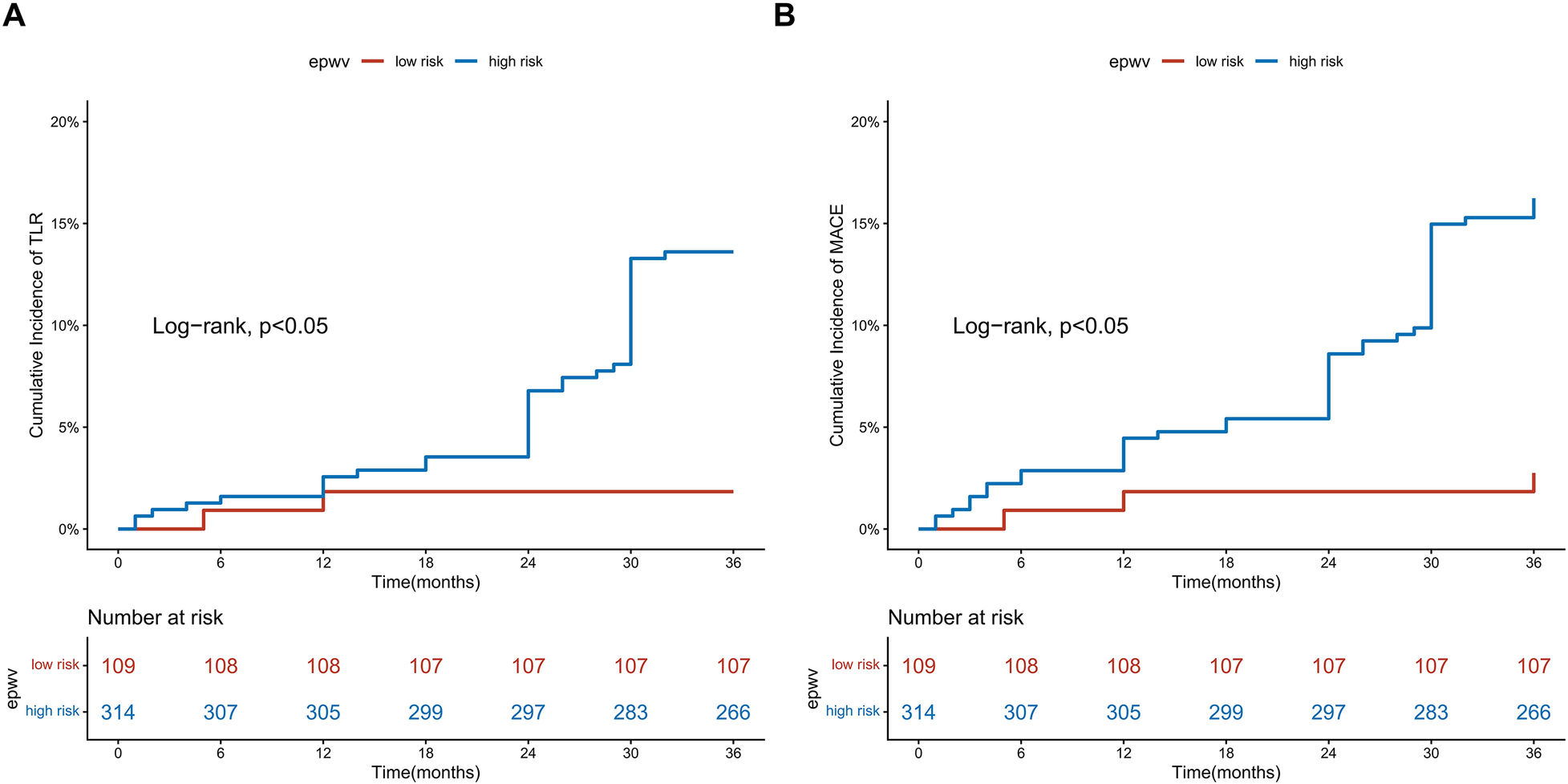

Establishing the optimal ePWV threshold for risk stratification

Maximally selected rank statistics identified an optimal ePWV cutoff of 10.91 m/s for predicting TLR and MACE risk, corresponding to the maximum standardized log-rank statistic. Kaplan–Meier curves demonstrated a difference in outcomes between the high-risk (ePWV ≥ 10.91 m/s) and low-risk (ePWV < 10.91 m/s) groups (log-rank test, P < 0.05) (Figure 3). Throughout the follow-up period, the high-risk group showed lower rates of TLR-free and MACE-free survival compared to the low-risk group (Figure 4).

Figure 3

Identification of the optimal ePWV cutoff value using maximally selected rank statistics. (A) The optimal cutoff for predicting TLR; (B) The optimal cutoff for predicting MACE. The vertical dashed line indicates the determined optimal cutoff value of 10.91 m/s, which corresponds to the maximum standardized log-rank statistic.

Figure 4

Kaplan–meier survival analysis stratified by the optimal ePWV cutoff value. (A) Freedom from TLR; (B) Freedom from MACE. Patients were stratified into low-risk (<10.91 m/s) and high-risk (≥10.91 m/s) groups.

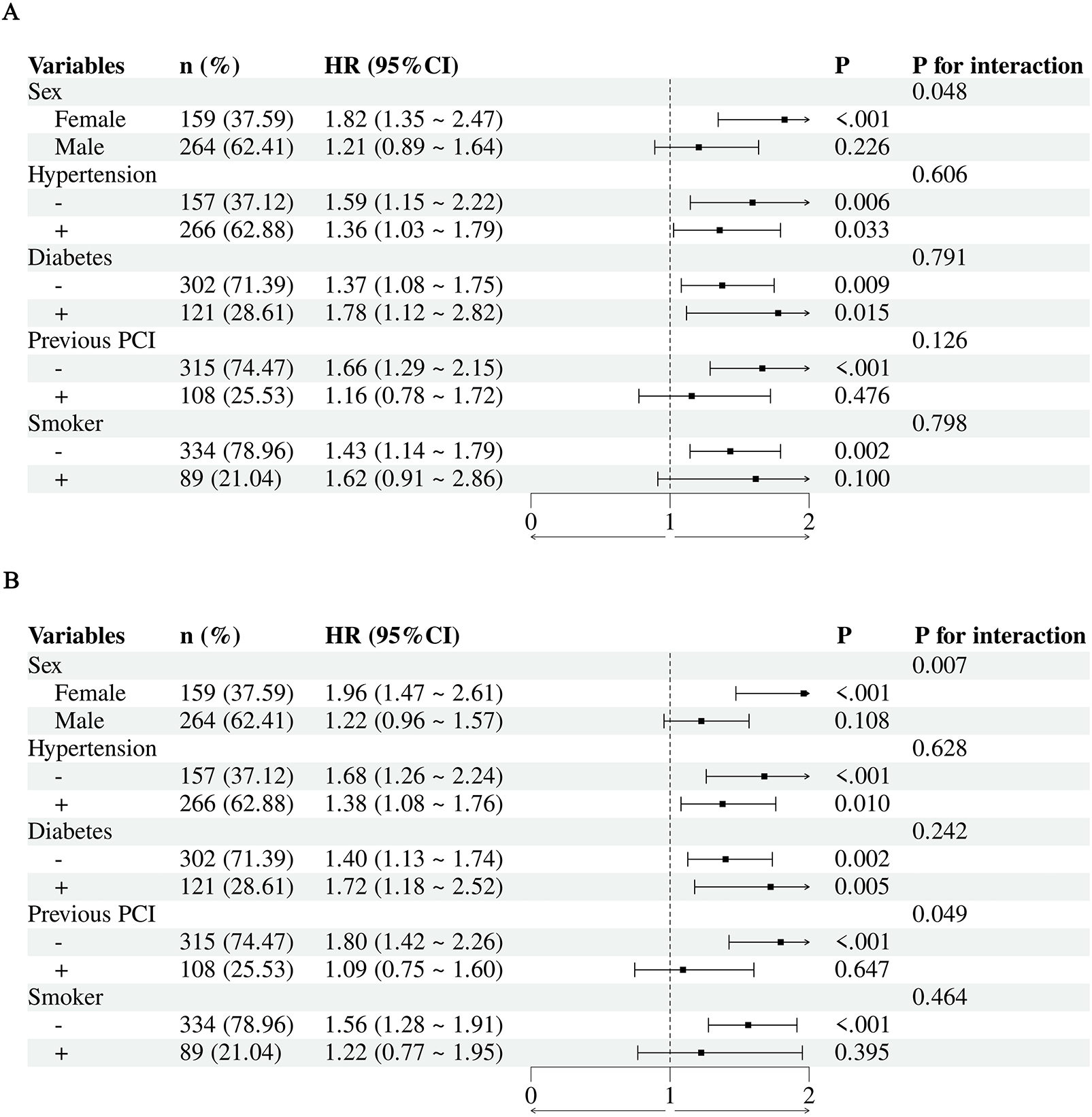

Subgroup analysis

This subgroup analysis of 423 patients explored factors influencing target lesion revascularization (TLR) and major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE). Overall, the analysis demonstrated an elevated risk in the total population (HR 1.46, 95% CI 1.18–1.79, P < 0.001) (Figure 5A). Notably, interactions by sex were observed for both TLR and MACE (P < 0.05) (Figures 5A,B). The association was consistently more pronounced in females compared to males for both endpoints, suggesting that elderly female patients may be particularly vulnerable to the risks associated with elevated ePWV. In contrast, no significant interactions were observed across other subgroups stratified by hypertension, diabetes, smoking history, or prior PCI.

Figure 5

Forest plots of subgroup analyses. (A) HR for TLR across different subgroups; (B) HR for MACE across different subgroups.

Sensitivity analyses

To verify the reliability of our findings, we performed comprehensive sensitivity analyses. We evaluated the association between ePWV and clinical outcomes using different adjustment models. The adjusted HR for ePWV per 1 m/s increase remained robust, at 2.58 for TLR and 2.43 for MACE (Supplementary Table S3). Additionally, analyses excluding participants with extreme ePWV values (top and bottom 2%) yielded consistent findings, with HRs of 1.35 for TLR and 1.47 for MACE (Supplementary Table S4).

Discussion

This study demonstrates that elevated estimated pulse wave velocity (ePWV) was associated with a higher risk of target lesion revascularization (TLR) and major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) in elderly patients with coronary heart disease after drug-coated balloon (DCB) angioplasty.

DCB angioplasty represents a “stent-free” interventional approach, delivering potent antiproliferative drugs directly to inhibit neointimal hyperplasia while eliminating the need for permanent metallic implants. Compared with drug-eluting stents (DES), DCB significantly simplifies the procedural technique, reduces contrast volume requirements, and shortens dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) duration—rendering it particularly advantageous for patients at high bleeding risk (20). Clinical trials confirm DCB achieves comparable clinical efficacy to DES in treating de novo lesions, supporting its broader implementation (21). Nonetheless, the occurrence rates of TLR and MACE following DCB intervention remain a significant clinical concern, particularly within complex anatomies or high-risk patient subgroups, potentially limiting its widespread adoption.

Our investigation reveals that ePWV exhibits an association with heightened risks of TLR and MACE in patients undergoing DCB treatment. The pronounced dose-response relationship across ePWV quartiles, coupled with an elevated hazard in the highest quartile. Notably, the wide 95% CI indicates substantial imprecision in the point estimate of HR due to the limited number of events, and the point estimates are too imprecise to be taken literally. Furthermore, the empirically derived ePWV cutoff of 10.91 m/s provides a clinically actionable risk stratification threshold, aiding identification of patients with substantially elevated TLR risk during long-term follow-up. Importantly, this cutoff is exploratory as it was established in the current cohort, and it requires external validation in independent populations to confirm robustness and generalizable utility.

These findings corroborate with prior research underscoring the prognostic importance of arterial stiffness in cardiovascular disease. Our results align with previous studies establishing ePWV as a predictor of adverse outcomes in CAD patients (10, 22). In a landmark study encompassing 12,792 U.S. adults, each 1 m/s increase in ePWV demonstrated a association with a 15% higher all-cause mortality risk (HR 1.15, 95% CI 1.10–1.20) following comprehensive multivariable adjustment. Individuals within the highest ePWV quartile faced a more than twofold surge in mortality risk (HR 2.24, 95% CI 1.72–2.92), reinforcing ePWV's status as a mortality predictor (23). Moreover, a male cohort study further solidified this relationship, revealing that elevated ePWV predicted heightened cardiovascular risk. Each 1 m/s increase was linked to a 13% rise in cardiovascular events (HR 1.13, 95% CI 1.06–1.21), even after accounting for conventional risk factors (24).

The specific contributions of ePWV in clarifying the mechanisms on outcomes following DCB treatment remain unclear. The following potential explanations are proposed. Long-term uncontrolled hypertension, a primary driver of arterial stiffness, accelerates atherosclerosis and restenosis, potentially mediating ePWV's predictive value. Elevated arterial stiffness can harm the delicate microstructure of blood vessels, triggering microvascular dysfunction, impairing arterial buffering capacity, and increasing the risk of vascular disease (25), thereby creating a vulnerable vascular environment. Crucially, elevated ePWV correlates with more complex coronary lesions, impaired vascular healing, and adverse hemodynamics (26, 27). These factors may translate into higher restenosis rates and increased adverse events post-DCB treatment. Beyond this, frailty, prevalent in elderly populations, correlates with arterial stiffness and predicts poor post-intervention outcomes via age-related declines in physiological reserve (28). While direct clinical evidence within CAD is currently limited, future research should rigorously evaluate ePWV alongside established prognostic markers. ePWV serves as a reflection of systemic vascular dysfunction and may enhance outcome prediction following endovascular therapies like DCBs (8).

Notably, sex stratified analyses revealed a pronounced interaction among elderly female patients, who exhibited an elevated risk. This finding underscores the important role of sex specific vascular pathophysiology in clinical outcomes. Postmenopausal estrogen loss accelerates arterial stiffness through endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and calcification. Inherent sex-based arterial differences, including smaller vessel diameter and reduced remodeling, further amplify hemodynamic vulnerability and compromise post-intervention healing (29). However, this sex-related finding preliminary and exploratory.

The prognostic value of ePWV in elderly patients undergoing DCB therapy should be interpreted in light of evolving evidence on DCB technology. The REC-CAGEFREE I trial (30), which showed paclitaxel-coated balloons (PCBs) to be inferior to sirolimus-eluting stents, reflects outcomes specific to one DCB platform in a particular clinical setting. Importantly, DCB platforms are heterogeneous. Emerging evidence indicates sirolimus-coated balloons (SCBs) may offer advantages or noninferiority over PCBs, including a lower binary restenosis rate in bifurcation lesions (31) and demonstrated noninferiority in late lumen loss for treating in-stent restenosis (32). These lesion types are common among elderly patients. These differences likely stem from variations in drug pharmacokinetics and coating technology. Future studies stratifying outcomes by both vascular stiffness (ePWV) and DCB platform are needed to refine patient selection for this high-risk elderly population.

This single-center retrospective study has limitations. First, selection bias cannot be ruled out due to strict exclusion criteria and the single-center design, potentially limiting generalizability. Second, unmeasured confounders, such as medication adherence or socioeconomic status, may have influenced outcomes. Third, statistical stability was limited by insufficient event counts in subgroups and multicollinearity when simultaneously adjusting for age and blood pressure (Supplementary Tables S5 & S6), which likely contributed to inflated hazard ratios. Fourth, the ePWV formula lacks specific validation in elderly PCI patients. Finally, the 3-year follow-up may miss late events, and the findings indicate correlation rather than causality.

Conclusion

Elevated ePWV correlates with elevated risks of TLR and MACE in elderly coronary heart disease patients following drug-coated balloon angioplasty. The exploratory cutoff value of 10.91 m/s represents a promising tool for risk assessment; however, its clinical application requires additional validation.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University (Approval No.: XYFY2022-KL242-01). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The ethics committee/institutional review board waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation from the participants or the participants' legal guardians/next of kin because As this was a retrospective analysis involving no intervention toward the subjects, a waiver of informed consent was formally granted by the same ethics committee (Approval No.: XYFY2022-KL242-01). All personally identifiable information was anonymized in the dataset prior to analysis.

Author contributions

FZ: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JS: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. LB: Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. WB: Conceptualization, Software, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Acknowledgments

The authors are deeply grateful to the study participants and the clinical staff for their invaluable support and contributions to this research.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcvm.2026.1706461/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Roth GA Mensah GA Johnson CO Addolorato G Ammirati E Baddour LM et al Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk factors, 1990-2019: update from the GBD 2019 study. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2020) 76(25):2982–3021. 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.11.010

2.

Yeh RW Shlofmitz R Moses J Bachinsky W Dohad S Rudick S et al Paclitaxel-Coated balloon vs uncoated balloon for coronary in-stent restenosis: the AGENT IDE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. (2024) 331(12):1015–1024. 10.1001/jama.2024.1361

3.

Cortese B Di Palma G Guimaraes MG Piraino D Orrego PS Buccheri D et al Drug-Coated balloon versus drug-eluting stent for small coronary vessel disease: PICCOLETO II randomized clinical trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. (2020) 13(24):2840–2849. 10.1016/j.jcin.2020.08.035

4.

Camaj A Leone PP Colombo A Vinayak M Stone GW Mehran R et al Drug-Coated balloons for the treatment of coronary artery disease: a review. JAMA Cardiol. (2025) 10(2):189–198. 10.1001/jamacardio.2024.4244

5.

Gitto M Sticchi A Chiarito M Novelli L Leone PP Mincione G et al Drug-Coated balloon angioplasty for de novo lesions on the left anterior descending artery. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. (2023) 16(12):e013232. 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.123.013232

6.

Stanek A Grygiel-Gorniak B Brozyna-Tkaczyk K Myslinski W Cholewka A Zolghadri S . The influence of dietary interventions on arterial stiffness in overweight and obese subjects. Nutrients. (2023) 15(6). 10.3390/nu15061440

7.

Kim BS Ahn JH Shin JH Kang MG Kim KH Bae JS et al Long-term prognostic implications of brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Front Med (Lausanne). (2024) 11:1384981. 10.3389/fmed.2024.1384981

8.

Huang Y Zhang S Ye X Huang Z Xiong Z Zhong X et al Impact of arterial stiffness on in-stent restenosis in the era of drug-eluting stents. Rev Cardiovasc Med. (2025) 26(6):23847. 10.31083/RCM23847

9.

Bargiotas I Mousseaux E Yu WC Venkatesh BA Bollache E de Cesare A et al Estimation of aortic pulse wave transit time in cardiovascular magnetic resonance using complex wavelet cross-spectrum analysis. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. (2015) 17(1):65. 10.1186/s12968-015-0164-7

10.

Chen C Bao W Chen C Chen L Wang L Gong H . Association between estimated pulse wave velocity and all-cause mortality in patients with coronary artery disease: a cohort study from NHANES 2005-2008. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. (2023) 23(1):412. 10.1186/s12872-023-03435-0

11.

Liu Z Kuang J Yan W Zhu Y Yang X Xu Y . Mediating role of arterial stiffness in the association between physical activity and cardiovascular disease risk: a prospective cohort study. Sci Rep. (2025) 15(1):38740. 10.1038/s41598-025-22442-z

12.

Chen T Yin H Zhou Y Liang M . Relationship between estimated pulse wave velocity trajectories and cardiovascular disease risk in patients with cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic syndrome stages 0-3. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. (2025) 35(11):104192. 10.1016/j.numecd.2025.104192

13.

Jeger RV Eccleshall S Wan Ahmad WA Ge J Poerner TC Shin ES et al Drug-Coated balloons for coronary artery disease: third report of the international DCB consensus group. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. (2020) 13(12):1391–1402. 10.1016/j.jcin.2020.02.043

14.

Jeger RV Farah A Ohlow MA Mangner N Mobius-Winkler S Leibundgut G et al Drug-coated balloons for small coronary artery disease (BASKET-SMALL 2): an open-label randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet. (2018) 392(10150):849–856. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31719-7

15.

Reference Values for Arterial Stiffness C. Determinants of pulse wave velocity in healthy people and in the presence of cardiovascular risk factors: ‘establishing normal and reference values’. Eur Heart J. (2010) 31(19):2338–2350. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq165

16.

Cheng W Kong F Pan H Luan S Yang S Chen S . Superior predictive value of estimated pulse wave velocity for all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality risk in U.S. General adults. BMC Public Health. (2024) 24(1):600. 10.1186/s12889-024-18071-2

17.

Zhou Z Liu X Xian W Wang Y Tao J Xia W . Estimated pulse wave velocity added additional prognostic information in general population: evidence from national health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES) 1999-2018. Int J Cardiol Cardiovasc Risk Prev. (2024) 20:200233. 10.1016/j.ijcrp.2023.200233

18.

Garcia-Garcia HM McFadden EP Farb A Mehran R Stone GW Spertus J et al Standardized End point definitions for coronary intervention trials: the academic research consortium-2 consensus document. Circulation. (2018) 137(24):2635–2650. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.029289

19.

Farooq V van Klaveren D Steyerberg EW Meliga E Vergouwe Y Chieffo A et al Anatomical and clinical characteristics to guide decision making between coronary artery bypass surgery and percutaneous coronary intervention for individual patients: development and validation of SYNTAX score II. Lancet. (2013) 381(9867):639–650. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60108-7

20.

Rissanen TT Uskela S Eranen J Mantyla P Olli A Romppanen H et al Drug-coated balloon for treatment of de-novo coronary artery lesions in patients with high bleeding risk (DEBUT): a single-blind, randomised, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. (2019) 394(10194):230–239. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31126-2

21.

Korjian S McCarthy KJ Larnard EA Cutlip DE McEntegart MB Kirtane AJ et al Drug-Coated balloons in the management of coronary artery disease. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. (2024) 17(5):e013302. 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.123.013302

22.

Laugesen E Olesen KKW Peters CD Buus NH Maeng M Botker HE et al Estimated pulse wave velocity is associated with all-cause mortality during 8.5 years follow-up in patients undergoing elective coronary angiography. J Am Heart Assoc. (2022) 11(10):e025173. 10.1161/JAHA.121.025173

23.

Heffernan KS Jae SY Loprinzi PD . Association between estimated pulse wave velocity and mortality in U.S. Adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2020) 75(15):1862–1864. 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.02.035

24.

Jae SY Heffernan KS Park JB Kurl S Kunutsor SK Kim JY et al Association between estimated pulse wave velocity and the risk of cardiovascular outcomes in men. Eur J Prev Cardiol. (2021) 28(7):e25–e27. 10.1177/2047487320920767

25.

Xu M Wang W Chen R Zhou L Hu H Qiao G et al Individual and combined associations of estimated pulse wave velocity and systemic inflammation response index with risk of stroke in middle-aged and older Chinese adults: a prospective cohort study. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2023) 10:1158098. 10.3389/fcvm.2023.1158098

26.

Gu Y Han X Liu J Li Y Li Z Zhang W et al Prognostic significance of estimated pulse wave velocity in critically ill patients with coronary heart disease: analysis from the medical information mart for intensive care IV database. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. (2025) 11(6):739–746. 10.1093/ehjqcco/qcae076

27.

Zhang J Jia X Li H Yang Q . Temporal and joint associations of hypertension and estimated pulse wave velocity with incident cardiovascular diseases: a population-based cohort study. Eur J Med Res. (2025) 30(1):572. 10.1186/s40001-025-02843-6

28.

Jiang X Cai Y Wu X Huang B Chen Y Zhong L et al The multiscale dynamics of beat-to-beat blood pressure fluctuation mediated the relationship between frailty and arterial stiffness in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. (2022) 77(12):2482–2488. 10.1093/gerona/glac035

29.

Boczar KE Boodhwani M Beauchesne L Dennie C Chan K Wells GA et al Estimated aortic pulse wave velocity is associated with faster thoracic aortic aneurysm growth: a prospective cohort study with sex-specific analyses. Can J Cardiol. (2022) 38(11):1664–1672. 10.1016/j.cjca.2022.07.013

30.

Tao L He X Shen G Wu M He Y Ma L et al Drug-Coated balloon angioplasty vs up-front stenting for de novo CAD: 3-year follow-up of REC-CAGEFREE I trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2025). 10.1016/j.jacc.2025.10.027

31.

Zhou Y Hu Y Zhao X Chen Z Li C Ma L et al Sirolimus-coated versus paclitaxel-coated balloons for bifurcated coronary lesions in the side branch: the SPACIOUS trial. EuroIntervention. (2025) 21(6):e307–e317. 10.4244/EIJ-D-24-00742

32.

Liu H Li Y Fu G An J Chen S Zhong Z Liu B Qiu C Ma L Cong H Li H Tong Q He B Jin Z Zhang J Yuan H Qiu M Zhang R Han Y . Sirolimus- vs paclitaxel-coated balloon for the treatment of coronary in-stent restenosis: the SIBLINT-ISR randomized trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2025;18(8):963–971. 10.1016/j.jcin.2024.12.024

Summary

Keywords

coronary heart disease, drug-coated balloon, elderly, major adverse cardiovascular events, target lesion revascularization

Citation

Zhang F, Shen J, Bo L and Bao W (2026) Association of estimated pulse wave velocity with outcomes following drug-coated balloon therapy in elderly coronary artery disease patients. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 13:1706461. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2026.1706461

Received

16 September 2025

Revised

11 January 2026

Accepted

28 January 2026

Published

13 February 2026

Volume

13 - 2026

Edited by

Tommaso Gori, Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, Germany

Reviewed by

Zhe Zhou, The First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University, China

Maria Emfietzoglou, Massachusetts Eye & Ear Infirmary and Harvard Medical School, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Zhang, Shen, Bo and Bao.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Wei Bao bw18752115786@163.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.