Abstract

Objective:

The aim of this work is to evaluate the effect of digital intervention technologies on blood pressure management and medication adherence in hypertensive individuals aged 18–59 years and to explore pathways for precise health management.

Methods:

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published up to April 2025 were systematically searched in PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, and four major Chinese databases (China National Knowledge Infrastructure, Chinese Biomedical Literature Database, Wanfang Data, and Vip Journal Integration Platform). The intervention group received digital interventions such as mobile health apps, remote monitoring, or smart wearable devices, while the control group received routine health education. The Cochrane Risk of Bias tool was used for literature quality assessment, and data analysis was performed using RevMan 5.4 software.

Results:

A total of 12 studies (n = 1,879) were finally included. Meta-analysis revealed the following: (1) Systolic blood pressure (SBP) decreased by 2.95 mmHg (WMD = −2.95, 95%CI: −4.22 to −1.69). (2) Diastolic blood pressure (DBP) decreased by 3.34 mmHg (WMD = −3.34, 95%CI: −4.63 to −2.06). (3) Medication adherence significantly improved (MD = 2.39, 95%CI: 0.98–3.79, P = 0.0009). Considerable heterogeneity was observed in adherence outcomes (I² = 93%). Subgroup analysis based on intervention duration indicated a significant effect within the 24-week subgroup (MD = 2.75, 95%CI: 0.67–4.83), while the 12-week subgroup did not reach statistical significance (MD = 1.85, 95%CI: −0.82–4.52).

Conclusion:

Digital health interventions can improve blood pressure control in young and middle-aged hypertensive patients and show potential to enhance medication adherence. However, the observed high heterogeneity and differential effects based on intervention duration suggest that effectiveness may vary. This study provides evidence-based support for the application of digital tools in chronic disease management, while highlighting the need for more tailored and standardized approaches.

1 Introduction

Currently, the prevalence of hypertension in Chinese adults is 25.2% (1), with a significant trend toward younger age groups. Due to factors such as occupational stress and concerns about medication use, younger and middle-aged patients demonstrate significantly lower treatment adherence compared with elderly patients, resulting in low awareness rates (20.8%–38.0%), treatment rates (12.0%–27.3%), and control rates (4.3%–9.1%) (2). Emergency data reveal that over 90% of patients with hypertensive emergencies do not receive inpatient treatment (3), highlighting the challenges of out-of-hospital management. Traditional health education has problems such as insufficient standardization of implementation and limited coverage cycles (4). Digital health technologies, by overcoming time and space constraints, create a new path for building precise intervention models. This study aims to evaluate the intervention value of digital technologies in specific populations through evidence-based methods.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Inclusion criteria

(1) Study subjects: Individuals aged 18–59 years who met the diagnostic criteria of the Chinese Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Hypertension (2018) [i.e., systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥90 mmHg] were selected. (2) Intervention measures: The intervention group used digital health technologies (mobile health apps, remote monitoring, smart wearable devices, etc.), while the control group received routine health education. (3) Outcome indicators: SBP, DBP, and medication adherence (assessed by scales such as MASES-SF and Hill—Bone Scale) were used as indicators. (4) Study type: RCTs were utilized.

2.2 Search strategy

The following electronic databases were systematically searched from their inception to April 2025: PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, and four major Chinese databases (China National Knowledge Infrastructure, Chinese Biomedical Literature Database, Wanfang Data, and Vip Journal Integration Platform). The search terms used included the following: (hypertension OR “high blood pressure”) AND (mHealth OR “digital intervention” OR telemedicine) AND (adherence OR compliance). In addition, the references of relevant articles were manually traced to identify any further eligible studies.

2.3 Quality assessment

Two researchers independently conducted the following: (1) literature screening and data extraction; (2) methodological quality assessment using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool (4); and (3) disagreements were resolved through third-party arbitration. Quality grading was defined such that Grade A (low risk of bias) required meeting all six criteria.

2.4 Statistical analysis

RevMan 5.4 software was used for all statistical analyses: (1) continuous variables expressed as weighted mean difference (WMD) or standardized mean difference (SMD); (2) heterogeneity testing (random-effects model was applied when I² ≥ 50%); (3) publication bias assessment (Egger’s test); and (4) sensitivity analysis to verify the robustness of conclusions.

3 Results

3.1 Literature screening process

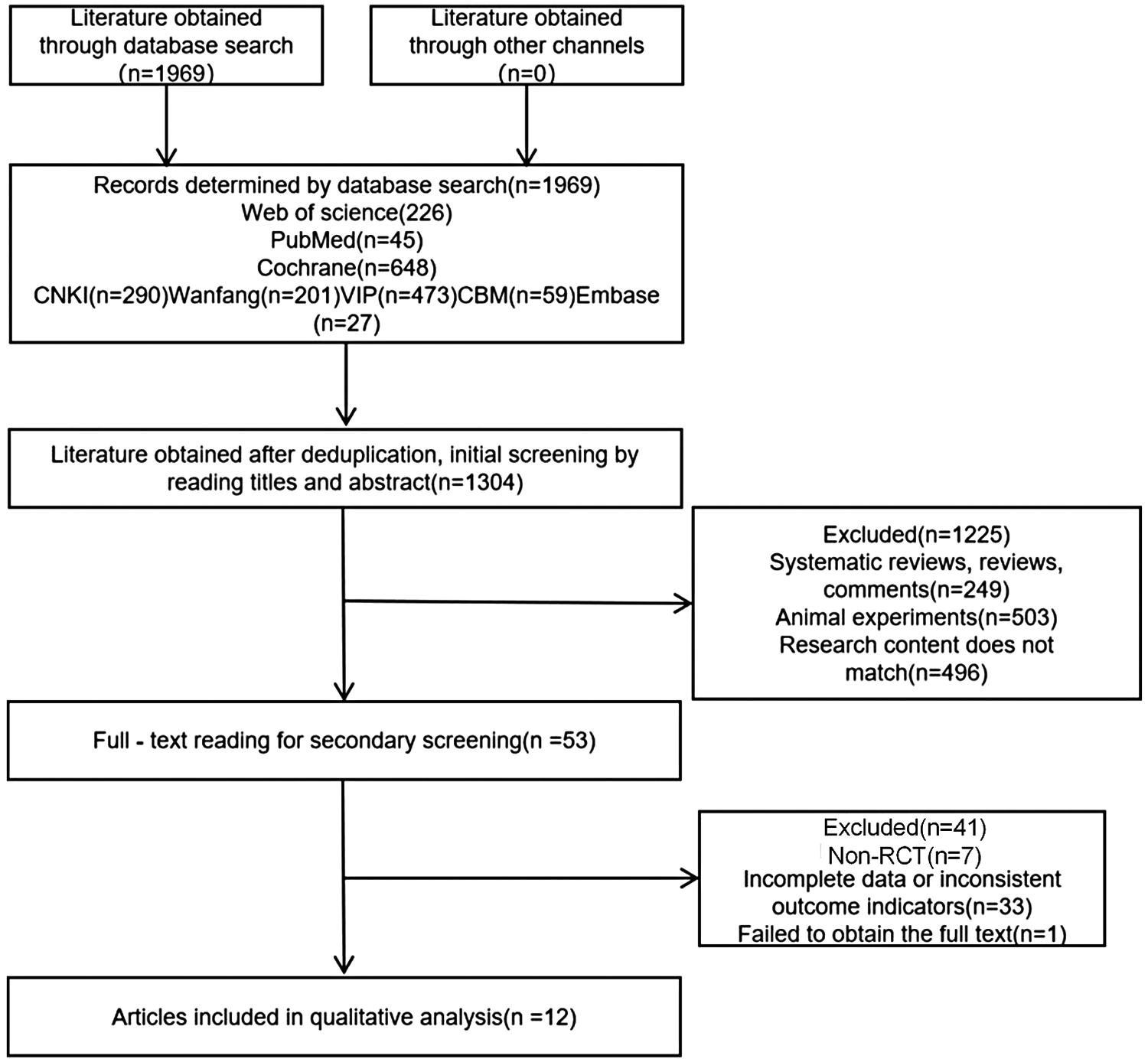

A total of 1,969 articles were initially retrieved. After deduplication, title and abstract screening, and full-text evaluation, 12 RCTs (5–16) were finally included, involving 1,879 patients (938 in the intervention group and 941 in the control group). The basic characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 1 and Figure 1.

Table 1

| First author | Publication year | Sample size (intervention group/control group) | Baseline blood pressure (mmHg)—intervention group (SBP/DBP) | Baseline blood pressure (mmHg)—control group (SBP/DBP) | Intervention—intervention group | Intervention—control group | Intervention period (weeks) | Outcome indicators |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabaci (6) | 2025 | 41/41 | 132.39 ± 13.09/84.15 ± 10.79 | 129.76 ± 13.69/81.27 ± 10.3 | HiperDostum smartphone application (based on the health belief model, including education modules, medication plans, medication reminder systems, and bi-weekly notifications) | Routine medical services | 12 | Medication adherence self-efficacy scale (MASES-SF), systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP) |

| Bhandari (7) | 2022 | 100/100 | 134 ± 19.5/84 ± 1.6 | 137 ± 25.3/86 ± 13.4 | Short message intervention (three times a week for 3 months) | Routine care | 12 | Adherence indicators (Hill Bone Scale), medication adherence self-efficacy, hypertension knowledge score, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure |

| Still (9) | 2020 | 30/30 | 138.51/81.97 | 138.51/85.28 | Online education + home blood pressure monitoring + medication management App + nurse consultation | Enhanced routine care (including home blood pressure monitoring) | 12 | Medication adherence (Hill–Bone Scale), systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure |

| Sun (5) | 2024 | 23/31 | 135.43 ± 17.48/78.39 ± 8.81 | 136.94 ± 18.44/76.03 ± 9.20 | WeChat-based digital intervention (health education + behavior change techniques) | Routine health education + self-management manual | 12 | Exercise time (MET—min/week), medication adherence score, blood pressure monitoring frequency (% daily monitoring), body weight (kg), SEVRa, learning performance score, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure |

| Yuting (8) | 2023 | 66/68 | 152.59 ± 23.44/92.85 ± 14.94 | 148.85 ± 20.70/91.34 ± 15.31 | Wearable blood pressure monitoring device + smartphone APP (reminders, medication reports, medical guidance, family support) | Routine community management | 12 | Waist circumference, hypertension adherence, self-efficacy, physical health, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure |

| Xueying (10) | 2024 | 33/34 | 130.91 ± 7.80/83.21 ± 6.6 | 133.21 ± 5.87/83.30 ± 4.19 | Routine medication care + medication literacy promotion program | Routine medication care | 12 | Medication literacy level, medication adherence, medication self-efficacy, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure |

| Qing (11) | 2019 | 100/100 | 152.01 ± 12.13/93.17 ± 7.37 | 153.26 ± 13.06/92.41 ± 8.46 | WeChat platform-extended nursing intervention based on attribution theory | Routine community care under the family doctor contract model | 24 | Systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, self-management, medication adherence |

| Na (12) | 2023 | 56/56 | 150.13 ± 10.724/92.472 ± 3.262 | 150.11 ± 10.547/93.056 ± 3.853 | Intervention program based on the Cox health behavior interaction model (health lectures, mobile phone push, remote counseling, hands-on experience, telephone interaction, patient exchange meetings, WeChat follow-up, etc.) | Routine health education intervention | 24 | BMI, total self-management score, self-efficacy score, medication adherence score, blood pressure control effectiveness rate, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure |

| Huicai (13) | 2019 | 131/131 | 144.56 ± 17.98/93.58 ± 13.65 | 144.14 ± 15.94/90.44 ± 11.26 | O2O model (WeChat platform + offline guidance) | Community contract-based services | 24 | Systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, hypertension-related knowledge |

| Online WeChat platform health education + offline home visits and health education lectures | ||||||||

| Lijuan (14) | 2020 | 50/50 | 134.86 ± 8.24/83.64 ± 5.65 | 135.98 ± 11.42/82.64 ± 4.06 | Routine community chronic management | Routine community chronic management (stated as control group in the original text, organized as per the figure) | 24 | Systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, medication adherence, blood pressure control rate, hypertension knowledge awareness rate, self-management behavior |

| Lijuan (15) | 2018 | 100/100 | 149.65 ± 16.78/95.72 ± 6.82 | 148.87 ± 17.87/96.71 ± 5.98 | Complication simulation experience education + routine education | Routine education | 4 | Systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, medication adherence, ATRABS level |

| Hypertension knowledge score (total score 22 points), treatment adherence (total 112 points) | ||||||||

| Bei (16) | 2018 | 115/111 | 144.56 ± 17.98/93.58 ± 13.65 | 1441. 4 ± 15.94/90.44 ± 11.26 | WeChat-based mobile medical intervention (weekly health education content push + online consultation + offline appointment) | Community contract-based services (health records + health education lectures + telephone follow-up) | 24 | Systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, BMI (kg/m²), medication adherence (total 112 points) |

Characteristics of included studies.

Figure 1

Flowchart of literature screening.

3.2 Characteristics of included studies

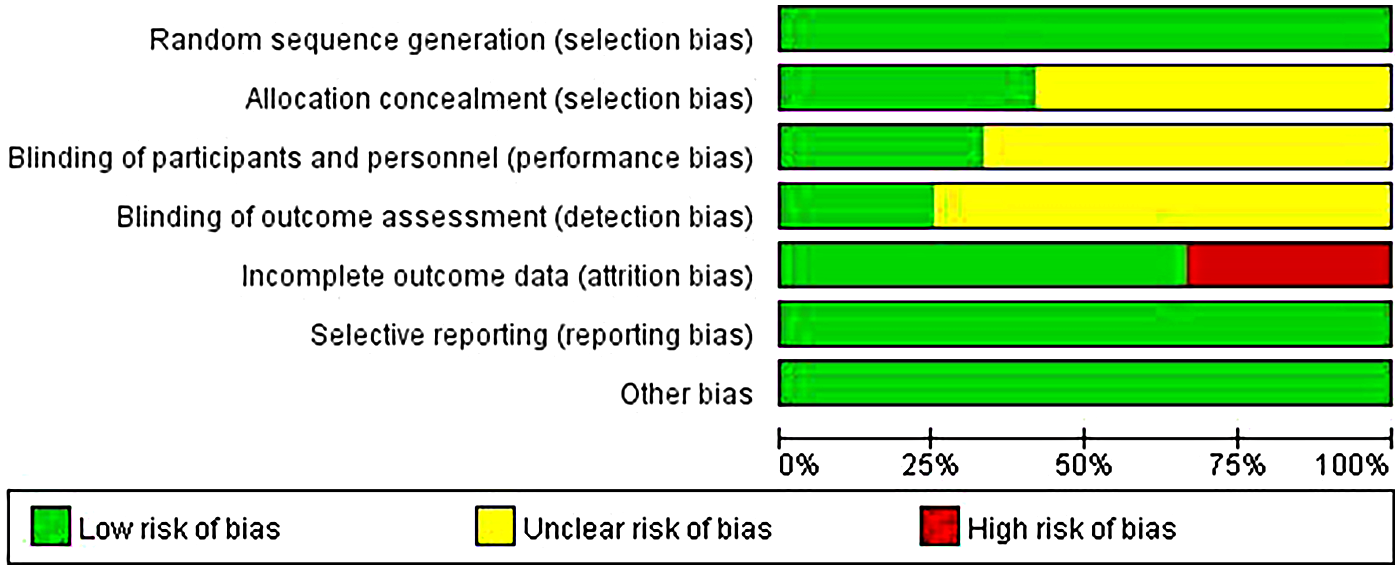

3.2.1 Quality assessment

The quality of included literature: Three studies were Grade A (6, 7, 14) (low risk of bias) and nine studies were Grade B (5, 8, 13, 15) (moderate risk of bias). The main sources of bias were insufficient allocation concealment and lack of blinding, as shown in Table 2 and Figure 2.

Table 2

| First author | Randomization | Allocation concealment | Blinding | Blinding | Completeness of result data | Selective reporting of research results | Other bias sources | Literature quality grade |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Research subject/implementer of intervention) | (Outcome assessor) | |||||||

| Yang (12) | Random number table method | Concealed allocation sequence | Unclear | Unclear | Five lost to follow-up (two in control group, three in intervention group) | None | None | Grade B |

| Qing (11) | Random number table method | Not mentioned | Unclear | Unclear | None | None | None | Grade B |

| Xueying (10) | Computer random number table method | Allocation sequence concealed | Unclear | Yes | Five lost to follow-up (three in intervention group, two in control group) | None | None | Grade B |

| Arabaci (6) | Randomized controlled trial | Allocation sequence concealed | Yes | Yes | None | None | None | Grade A |

| Bhandari (7) | Randomized controlled trial | Allocation concealed | Yes | Yes | None | None | None | Grade A |

| Still (9) | Randomized controlled trial | Not mentioned | Unclear | Unclear | None | None | None | Grade B |

| Sun (5) | Random number table method | Not mentioned | Unclear | Unclear | 14 lost to follow-up | None | None | Grade B |

| Yuting (8) | Randomized controlled trial | Not mentioned | Unclear | Unclear | 14 lost to follow-up | None | None | Grade B |

| Bei (16) | Computer randomization | Not mentioned | Unclear | Unclear | Not reported | None | None | Grade B |

| Lichang (15) | Random number table method | Not mentioned | Unclear | Unclear | None | None | None | Grade B |

| Huicai et al. (13) | Random grouping | Not mentioned | Unclear | Unclear | Not reported | None | None | Grade B |

| Lijuan (14) | Computer randomization | Allocation concealed | Yes | Yes | None | None | None | Grade A |

Methodological quality assessment of included literature.

Figure 2

Bar chart of risk of bias for included studies. Bar chart generated after methodological quality assessment of 12 included studies using the Cochrane risk of bias tool.

3.3 Results of meta-analysis

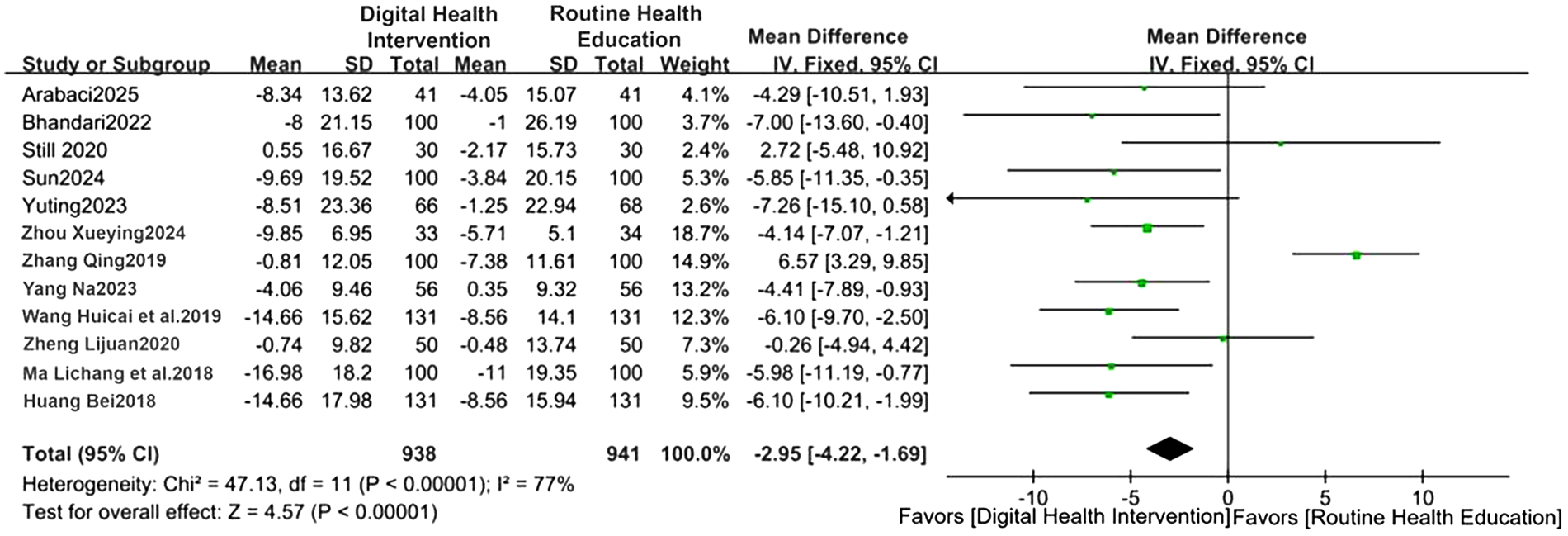

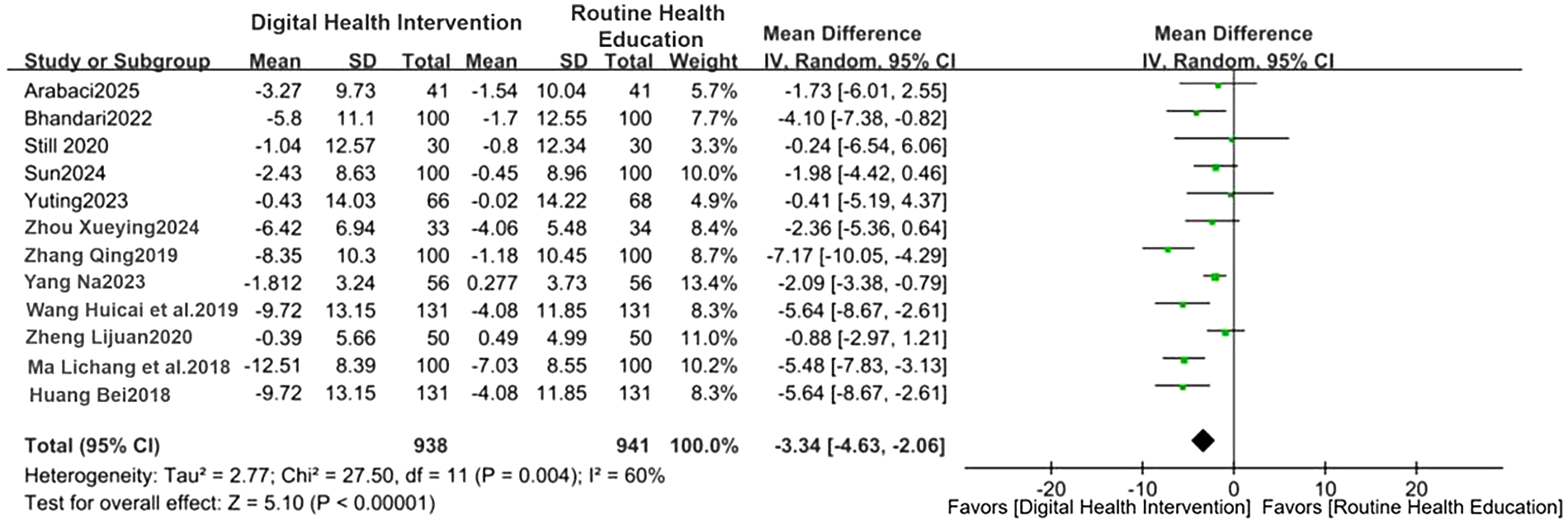

Blood pressure control: The digital intervention group showed a decrease in SBP by 2.95 mmHg (95%CI: −4.22 to −1.69, P < 0.00001) and DBP by 3.34 mmHg (95%CI: −4.63 to −2.06, P = 0.004), with effect sizes shown in Figures 3, 4. For treatment adherence, the digital health interventions group demonstrated a statistically significant improvement compared to the routine health education group (MD = 2.39, 95%CI: 0.98–3.79, P = 0.0009; I² = 93%, random-effects model). Given substantial heterogeneity (I² = 93%), subgroup analysis by intervention duration was performed. The 24-week intervention subgroup showed a significant effect (MD = 2.75, 95%CI: 0.67–4.83, P = 0.009; I² = 88%), while the 12-week intervention subgroup did not reach statistical significance (MD = 1.85, 95%CI: −0.82–4.52, P = 0.17; I² = 95%). No significant difference was observed between subgroups (P = 0.52), suggesting that the heterogeneity may be attributed to factors other than intervention duration (Figure 5).

Figure 3

Forest plot of SBP comparison (WMD = −2.95). Forest plot comparing changes in SBP between the digital health intervention group and the routine health education control group via meta-analysis.

Figure 4

Forest plot of DBP comparison (WMD = −3.34). Forest plot comparing changes in DBP between the digital health intervention group and the routine health education control group via meta-analysis.

Figure 5

![A forest plot shows the results of two subgroups: 12-week and 24-week interventions, with mean differences (MD) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). For the 12-week group, the subtotal MD is 1.85 with CI [-0.82, 4.52]. For the 24-week group, the subtotal MD is 2.75 with CI [0.67, 4.83]. The total effect across all studies shows an MD of 2.39 and CI [0.98, 3.79]. The plot displays individual study weights, heterogeneity statistics, and overall effect.](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1708019/xml-images/fcvm-13-1708019-g005.webp)

Subgroup analysis of the impact of different intervention durations on adherence. Forest plot comparing the impact of digital health interventions on medication adherence by subgroup analysis of intervention durations (12 and 24 weeks).

4 Discussion

This meta-analysis confirms that digital health interventions exert significant clinical effects on improving blood pressure control in young and middle-aged hypertensive patients. Compared with routine health education, digital health interventions can reduce SBP by an average of 2.95 mmHg (WMD = −2.95, 95%CI: −4.22 to −1.69) and DBP by an average of 3.34 mmHg (WMD = −3.34, 95%CI: −4.63 to −2.06). These findings are consistent with the conclusions of the latest systematic review published in 2024, which also confirmed that digital interventions such as mHealth and telemedicine can significantly reduce SBP and DBP in hypertensive patients (17). However, the magnitude of blood pressure reduction in our study appears more modest compared with some other meta-analyses. For example, a recent meta-analysis focusing specifically on patients with uncontrolled baseline hypertension reported a more pronounced SBP reduction of 4.45 mmHg (18). This discrepancy is likely attributable to differences in study populations; our inclusion of patients with better-controlled baseline blood pressure may have limited the potential for larger reductions. This suggests that the effectiveness of digital interventions is modulated by the initial hypertension severity. It is also worth noting that the present study found a slightly greater reduction in DBP than in SBP. This observation may be linked to the specific vascular physiology of our younger study cohort. In individuals under 50 years, interventions that improve peripheral vascular resistance can exert a more substantial impact on DBP, whereas the age-related increase in large arterial stiffness, which primarily drives SBP, is less pronounced. Therefore, the observed effect may reflect a genuine physiological response to digital health interventions within this demographic (19).

The superiority of digital health interventions in blood pressure control stems from their multi-target mechanisms of action. First, continuous blood pressure monitoring via smart wearable devices addresses the “white-coat effect” and insufficient monitoring of traditional office-based blood pressure measurement, providing comprehensive data support for treatment adjustments (20). Second, personalized feedback systems based on artificial intelligence algorithms can dynamically analyze lifestyle data of patients and provide precise behavioral intervention recommendations, resulting in an average reduction of 14.66 mmHg in SBP and 8.56 mmHg in DBP in Stage 2 hypertensive patients within 24 weeks (16). Third, digital interventions significantly improve the standardization and continuity of treatment through functions such as medication reminders, adherence tracking, and electronic pill boxes (6, 8, 9, 21, 22). Crucially, the innovation of this study lies in its specific focus on young and middle-aged patients, a population for which there is a recognized “guidance gap” in clinical management. As noted in a scientific statement from the American Heart Association, there is a lack of clear recommendations for managing Stage 1 hypertension in lower-risk adults, who are predominantly from this age group (23). Furthermore, young and middle-aged patients face unique self-management challenges, including lower disease awareness and competing work–life pressures (24). Digital health tools are particularly well suited to address these barriers by providing convenient, discreet, and integrated support, thus filling a critical niche in the hypertension care continuum. Clifford et al.’s 's (20) study summarized the current status of precision health research, emphasizing the importance of personalization, phenotyping, and prediction of adult hypertension management using digital health tools. It proposed that more interdisciplinary collaboration and ultimately interdisciplinary approaches are needed to meaningfully advance the field of precision health in hypertension risk prediction, prevention, and management.

The findings of this review should be interpreted in light of the strengths and limitations of the included studies. A key strength is that all synthesized evidence originated from RCTs, which represent the highest level of primary study design for evaluating interventions. Several studies incorporated objective outcome measures, such as automated blood pressure monitoring data, alongside self-reported adherence scales, thereby enhancing the validity of the results. Furthermore, a number of trials were conducted over 24 weeks, providing insights into the medium-term sustainability of digital health effects. However, methodological limitations of the primary studies must be acknowledged. The main sources of bias arose from inadequate allocation concealment and a lack of blinding of participants and personnel, which is a common but notable challenge in behavioral intervention trials. Attrition bias was present in some studies, and several had relatively small sample sizes, limiting the precision of individual findings. The considerable clinical heterogeneity—stemming from variations in the specific digital platforms used, intervention components, and cultural contexts—further complicates direct comparisons. These limitations underscore that while the pooled results are encouraging, they are derived from an evolving evidence base with inherent methodological variabilities.

Despite the positive conclusions of this study, the following limitations should be acknowledged: Larger sample sizes and higher-quality RCTs are still needed to further verify the conclusions of this study. Digital interventions are diverse (apps, wearable devices, telemedicine, etc.), but the differences in effectiveness between different technical forms have not been fully analyzed. The response differences among patients with different cultural backgrounds and educational levels have not been deeply analyzed.

Future research should focus on developing phenotype-oriented intervention matching strategies, dynamic dose adjustment technologies, and social-–ecological integration models, while strengthening long-term effects and economic evaluation. Interventions for young and middle-aged populations need to focus on precise pathway design. By integrating digital technology, precision medicine, and health system reform, we have the potential to reverse the severe situation of the “three lows” (low awareness rate, low treatment rate, and low control rate) in young and middle-aged people with hypertension. Ultimately, this approach may reduce lifelong cardiovascular risk in this critical population and contribute to achieving the “Healthy China 2030” strategic goal.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

RN: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. KL: Writing – review & editing, Resources, Methodology, Supervision, Investigation, Data curation.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AMLm, acute myeloid leukemia; BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; Cochrane, Cochrane Library; CNKI, China National Knowledge Infrastructure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; EFS, event-free survival; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; GAL9, galectin-9; IKK, IκB kinase; IkappaB, inhibitor of kappa B; mHealth, mobile health; MASES-SF, medication adherence self-efficacy scale-short form; NF-κB, nuclear factor-kappa B; O2O, online to offline; RCT, randomized controlled trial; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SMD, standardized mean difference; TIM3, T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain containing-3; VIP, vip journal integration platform; Wanfang, Wanfang data; WMD, weighted mean difference; CBM, Chinese Biomedical Literature Database; Embase, excerpta medica database.

References

1.

Ott C Schmieder RE . Diagnosis and treatment of arterial hypertension 2021. Kidney Int. (2022) 101(1):36–46. 10.1016/j.kint.2021.09.026

2.

Zhang M Shi Y Zhou B Huang Z Zhao Z Li C et al Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in China, 2004–18: findings from six rounds of a national survey. BMJ (Clinical Research ed). (2023) 380:e071952. 10.1136/bmj-2022-071952

3.

Masood S Austin PC Atzema CL . A population-based analysis of outcomes in patients with a primary diagnosis of hypertension in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. (2016) 68(3):258–67.e5. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.04.060

4.

Lizano-Díez I Poteet S Burniol-Garcia A Cerezales M. The burden of perioperative hypertension/hypotension: a systematic review. PLoS One. (2022) 17(2):e0263737. 10.1371/journal.pone.0263737

5.

Sun T Xu X Ding Z Xie H Ma L Zhang J et al Development of a health behavioral digital intervention for patients with hypertension based on an intelligent health promotion system and WeChat: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. (2024) 12:e53006. 10.2196/53006

6.

Arabaci Z Uysal Toraman A . The effects of a smartphone app-supported nursing care program on the disease self-management of hypertensive patients: a randomized controlled study. Public Health Nursing (Boston, Mass). (2025) 42(2):811–21. 10.1111/phn.13499

7.

Bhandari B Narasimhan P Jayasuriya R Vaidya A Schutte AE. Effectiveness and acceptability of a mobile phone text messaging intervention to improve blood pressure control (TEXT4BP) among patients with hypertension in Nepal: a feasibility randomised controlled trial. Glob Heart. (2022) 17(1):13. 10.5334/gh.1103

8.

Yuting Z Xiaodong T Qun W . Effectiveness of a mHealth intervention on hypertension control in a low-resource rural setting: a randomized clinical trial. Front Public Health. (2023) 11:1049396. 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1049396

9.

Still CH Margevicius S Harwell C Huang MC Martin L Dang PB et al A community and technology-based approach for hypertension self-management (COACHMAN) to improve blood pressure control in African Americans: results from a pilot study. Patient Prefer Adherence. (2020) 14:2301–13. 10.2147/PPA.S283086

10.

Xueying Z . Construction and Validation of a Program for Enhancing Medication Awareness among Middle-aged and Young Hypertensive Patients. (2024).

11.

Qing Z . Evaluation of the effect of extended nursing intervention based on attribution theory on young hypertensive patients in the community. (2019).

12.

Na Y . An Intervention Study of the Cox Health Behavior Interaction Model in Self-Management of Hypertension among Young and Middle-aged Patients. (2023).

13.

Huicai W Yuanshao W Guixiang Z Bei H Guoping H. The intervention effect of the O2O model in the health management of middle-aged and young hypertensive patients. Chin Nurs Manag. (2019) 19(07):979–84. 10.3969/j.issn.1672-1756.2019.07.006

14.

Lijuan Z . Evaluation Study on the Intervention Effect of Community Management Model for Young and Middle-aged Hypertension Patients in O2O Model. (2020).

15.

Lichang M Ying S Wenjuan L . A study on the impact of complication simulation experience education model on the self-management behaviors of young patients with primary hypertension. Chin J Prac Nurs. (2018) 34(11):5.

16.

Bei H . The Application of Mobile Healthcare Based on “Internet +” in the Health Management of Hypertensive Patients in a Certain Community. [D]. Xinjiang: Xinjiang Medical University (2018).

17.

Bandeira ACN Gama de Melo PU Johann EB Ritti-Dias RM Rech CR Gerage AM. Effect of m-health-based interventions on blood pressure: an updated systematic review with meta-analysis. Telemed J E Health. (2024) 30(9):2402–18. 10.1089/tmj.2023.0545

18.

Zhou L He L Kong Y Lai Y Dong J Shen H . Effectiveness of mHealth interventions for improving hypertension control in uncontrolled hypertensive patients: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). (2023) 25(5):454–63. 10.1111/jch.14690

19.

Webb AJ Mcdonnell BJ Chirinos JA . Progression of arterial stiffness is associated with midlife diastolic blood pressure and transition to late-life hypertensive phenotypes. J Am Heart Assoc. (2020) 9(1):e014547. 10.1161/JAHA.119.014547

20.

Clifford N Tunis R Ariyo A Yu H Rhee H Radhakrishnan K. Trends and gaps in digital precision hypertension management: scoping review. J Med Internet Res. (2025) 27:e59841. 10.2196/59841

21.

Beune EJ Moll van Charante EP Beem L Mohrs J Agyemang CO Ogedegbe G et al Culturally adapted hypertension education (CAHE) to improve blood pressure control and treatment adherence in patients of African origin with uncontrolled hypertension: cluster-randomized trial. PLoS One. (2014) 9(3):e90103. 10.1371/journal.pone.0090103

22.

Buis LR Kim J Sen A Chen D Dawood K Kadri R et al The effect of an mHealth self-monitoring intervention (MI-BP) on blood pressure among black individuals with uncontrolled hypertension: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. (2024) 12:e57863. 10.2196/57863

23.

Jones DW Whelton PK Allen N Clark D Gidding SS Muntner P et al Management of stage 1 hypertension in adults with a low 10-year risk for cardiovascular disease: filling a guidance gap: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertension. (2021) 77(6):e58–67. 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000195

24.

He R Wei F Hu Z Huang A Wang Y . Self-management in young and middle-aged patients with hypertension: a systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. Syst Rev. (2024) 13(1):254. 10.1186/s13643-024-02665-3

Summary

Keywords

digital healthcare, hypertension, medication adherence, systematic review, young and middle-aged population

Citation

Niu R and Li K (2026) Systematic review of the impact of digital health technologies on blood pressure control and treatment adherence in young and middle-aged hypertensive patients. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 13:1708019. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2026.1708019

Received

18 September 2025

Revised

25 December 2025

Accepted

06 January 2026

Published

27 January 2026

Volume

13 - 2026

Edited by

Gaetano Santulli, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, United States

Reviewed by

Ayoposi Ogboye, British Institute in Eastern Africa, Kenya

Fang Liu, Health Management Center of General Hospital of Ningxia Medical University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Niu and Li.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Keye Li 18072928551@163.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.