Abstract

Background:

Olanzapine is an atypical antipsychotic used to treat schizophrenia and manic episodes. Its potential thromboembolic risk has been reported, but the evidence remains controversial. This study aimed to comprehensively evaluate the association between olanzapine and pulmonary embolism (PE) and venous thromboembolism (VTE).

Methods:

This study combined meta-analysis and signal mining from the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) database to assess the association between olanzapine and pulmonary embolism (PE) and venous thromboembolism (VTE).

Results:

From 55,905 olanzapine-related adverse event reports in the Faers database, 1,233 significant signals were identified, including serious adverse events not fully documented on the drug label, such as pulmonary embolism and venous embolism. A meta-analysis of eight studies showed that olanzapine use significantly increased the risk of VTE and pulmonary embolism (OR = 2.07, 95% CI: 1.37–3.14, P = 0.0006).

Conclusion:

These findings suggest that olanzapine is associated with an increased risk of thromboembolic events; therefore, enhanced clinical surveillance and further investigation into its safety are necessary.

Systematic Review Registration:

https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/, identifier CRD420251003254.

1 Introduction

Olanzapine is an atypical antipsychotic drug belonging to the thienobenzodiazepine class. It exhibits high binding affinity for various neurotransmitter receptors, including dopamine (DA), serotonin (5-HT), histamine (H1), adrenergic (α1), and muscarinic (M) receptors. Olanzapine was first introduced in Switzerland in 1996 and subsequently in China in 1999 (1). Clinically, olanzapine is primarily used to treat schizophrenia and acute manic or mixed episodes associated with bipolar I disorder. It can also be used as monotherapy or adjunctive therapy to effectively treat depressive episodes of bipolar I disorder and for maintenance therapy. Furthermore, due to its potent antiemetic properties through antagonism of dopamine and serotonin receptors, olanzapine has been investigated and used off-label for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (2, 3).

Thromboembolic events, particularly pulmonary embolism (PE) and venous thromboembolism (VTE), are potentially life-threatening serious adverse events. PE is a pathological condition caused by endogenous or exogenous emboli obstructing the pulmonary artery and its branches, primarily manifesting as dyspnea, chest pain, and hypoxemia. In severe cases, it can be fatal (4). Most cases are acute (5), while a few have a chronic course (6), often accompanied by signs and symptoms related to deep vein thrombosis (DVT) in the lower extremities (7).VTE is a pathological condition caused by the formation of thrombi that obstruct venous blood flow. It primarily includes DVT, which involves clot formation in the deep veins, and PE, which occurs when a thrombus dislodges and travels to the lungs, resulting in occlusion of the pulmonary artery (8). Furthermore, the incidence of VTE increases exponentially with age, with a markedly elevated risk observed in individuals over 40 years of age (9).

The association between conventional antipsychotic drugs and VTE was first reported in the 1950s (10). In 1997, Walker et al. reported the association between atypical antipsychotic drugs and thrombosis, finding that the use of these drugs increased the risk of PE by five times (11). Two case reports documented pulmonary embolism and venous thromboembolism events that occurred after the initiation of olanzapine treatment (12, 13). A retrospective study conducted by the Becksa County Medical Examiner's Office in 2008 found a temporal association between olanzapine use and pulmonary embolism in four antipsychotic drug-related deaths that occurred between 1998 and 2005 (14). Subsequent studies have shown that olanzapine may significantly increase the incidence of venous thromboembolism and pulmonary embolism, particularly in older patients (15).

Studies have shown that olanzapine can induce metabolic disorders, including hyperglycemia, hyperleptinemia, and dyslipidemia (16). Its thrombotic mechanisms involve multiple pathways, including promoting platelet aggregation by activating serotonin receptors and inducing venous congestion through alpha receptor-mediated hypotension (17). Olanzapine can also impair vascular endothelial function by increasing inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) (18). In addition, olanzapine can stimulate the production of prolactin-mediated antiphospholipid antibodies (19) or induce acetyl-CoA carboxylase phosphorylation, thereby affecting vascular function (20). These mechanisms together constitute the pathological basis of olanzapine-related thrombosis.

Traditional antipsychotics (chlorpromazine) have been shown to be associated with an increased risk of VTE, but the conclusions regarding atypical antipsychotics (olanzapine) are still unclear (21). Although previous systematic reviews have explored the relationship between antipsychotics and VTE and PE, there is still a lack of specific analyses of olanzapine (22). To address this gap, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis, integrated the observational evidence from existing cohort studies and case-control studies, and calculated the combined effect value (OR) and its confidence interval (CI) through strict data extraction, quality assessment (Newcastle-Ottawa scale) and statistical analysis (Review Manager 5.4 and Stata 16 software) to quantitatively evaluate the strength of the association between the use of olanzapine and the risk of PE and VTE. At the same time, we conducted pharmacovigilance analysis based on the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) database (23, 24) to provide more comprehensive and accurate evidence for the assessment of this clinical safety issue.

2 Materials and methods

This review was registered with PROSPERO (International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews; ID: CRD420251003254), and the meta-analysis was conducted and reported in strict accordance with the 27 items outlined in the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) checklist (25). Literature screening, study selection, data extraction, and quality assessment were independently performed by two researchers. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion or, if necessary, consultation with a third reviewer.

2.1 FAERS database

2.1.1 FAERS database mining

FAERS is a publicly accessible post-marketing pharmacovigilance database that compiles ADE reports from a wide range of sources, including healthcare professionals, patients, pharmaceutical companies, and legal representatives. The database receives global ADE submissions and is updated on a quarterly basis. It contains detailed information on reporting sources, demographic and administrative data, medication usage, indication or diagnosis, treatment start and end dates, reported adverse events, patient outcomes, and cases deemed invalid. In this study, all available data from FAERS across 35 quarters—from the first quarter of 2016 to the third quarter of 2024—were extracted and imported into RStudio for data cleaning and subsequent analysis.

2.1.2 Data extraction and screening

This study focused on the safety of olanzapine monotherapy; therefore, the “role_cod” field in the extracted reports was limited to the primary suspect drug (PS). Both the trade name Zyprexa and the generic name olanzapine were used as search terms, and only ADE reports in which olanzapine was identified as the primary suspected drug were included. ADE terms were coded using the Preferred Term (PT) level of the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA®) version 26.0, as defined by the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH). PTs were further classified, organized, and quantified based on the System Organ Class (SOC) categories in MedDRA (26). To eliminate duplicate records, reports were sorted by CASEID, FDA_DT, and PRIMARYID. For multiple entries with the same CASEID, the report with the latest FDA_DT was retained; if both CASEID and FDA_DT were identical, the report with the highest PRIMARYID was selected (27). In addition, clinical characteristics of patients who experienced adverse events following olanzapine use—including age, sex, reporter type, reporting region, body weight, and patient outcomes—were also collected.

2.1.3 Signal mining algorithm

This study employed a 2 × 2 contingency table based on the odds imbalance method (Table 1) and applied both the reporting odds ratio (ROR) (28) and the proportional reporting ratio (PRR) to detect ADE signals associated with olanzapine, thereby enhancing the robustness of signal detection results (29). The ROR offers an advantage in adjusting for potential bias arising from low-frequency event reporting, while the PRR demonstrates relatively higher specificity compared to ROR. The formulas and signal detection thresholds for both algorithms are presented in Table 2. Statistical analyses were conducted using R software. Higher ROR or PRR values reflect greater signal strength, indicating a stronger association between olanzapine and the reported ADE.

Table 1

| Drug | Target Event | Other events | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target Drugs | a | b | a + b |

| Other medicines | c | d | c + d |

| Total | a + c | b + d | a + b + c + d |

Four-grid table of ratio imbalance measurement method.

a: The number of reports that record both the target drug and its corresponding specific adverse events; b: The number of reports of other atypical adverse events caused by the target drug; c: The number of reports of similar adverse events caused by non-target drugs; d: The number of reports containing non-target drugs and their related adverse events.

Table 2

| Method | Formula | Signal generation standards |

|---|---|---|

| ROR | ROR=ad/bc | N ≥ 3, ROR 95%CI > 1 |

| 95%CI = eln(ROR) ± 1.96(1/a + 1/b + 1/c + 1/d)^0.5 | ||

| PRR | PRR = a(c + d)/c/(a + b) | N ≥ 3, PRR≥2, χ2 ≥ 4 |

| χ2 = [(ad-bc)^2](a + b + c + d)/[(a + b)(c + d)(a + c) (b + d)] |

Calculation formula and signal generation standard of ratio imbalance method.

a: The number of reports that record both the target drug and its corresponding specific adverse events; b: The number of reports of other atypical adverse events caused by the target drug; c: The number of reports of similar adverse events caused by non-target drugs; d: The number of reports containing non-target drugs and their related adverse events; N: The number of reports. PRR, Proportional Reporting Ratio; ROR, Reporting Odds Ratio.

2.2 Meta-analysis

2.2.1 Search strategy

The literature search strategy was based on a computer system to search for relevant literature published before January 2025 in PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, and SCOPUS databases. The language of literature search was set to English. A combination of subject terms and free terms were used in all searches. The subject headings included ‘Olanzapine’, ‘Pulmonary embolism’, ‘Venous thromboembolism’, and the free terms included ‘2- Methyl- 4- (4- methyl- 1- piperazinyl)-10H-thieno(2,3-b) (1,5) benzodiazepine’, ‘Zyprexa’, ‘Olanzapine Pamoate’, ‘Zolafren’ and ‘pulmonary embolisms’, ‘Pulmonary Thromboembolisms’, ‘Pulmonary Thromboembolism’. For detailed search strategies, see Supplementary Figure S1.

2.2.2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

This study followed the PICOS (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, Study design) framework (30), and applied strict inclusion and exclusion criteria for literature selection. The population included adult patients (≥18 years old) with a confirmed diagnosis of schizophrenia or mania. The intervention of interest was treatment with olanzapine, regardless of dosage, treatment duration, or route of administration (e.g., oral or injectable), either as monotherapy or in combination with other agents. The comparison group consisted of similar patients who did not receive olanzapine but were treated with other antipsychotic medications, as well as healthy individuals from the same patient source. Eligible study designs included observational studies (e.g., cohort studies and case-control studies) and randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Only studies published in English were considered. The primary outcome was the incidence of clinically confirmed VTE or PE in the olanzapine group vs. the control group. In addition, studies were required to report effect estimates such as relative risk (RR), odds ratio (OR), and their corresponding 95% CIs, or other extractable measures of association.

The following types of literature were excluded from this study: (1) case reports, cross-sectional studies, and experimental studies (including in vitro and animal experiments); (2) review articles, conference abstracts, studies without control groups, editorial letters, and studies with missing or invalid data; (3) publications in which the study population, intervention, or outcome measures did not meet the inclusion criteria; and (4) studies for which the full text was not available.

2.2.3 Literature screening and data extraction

An initial screening was conducted by two investigators who independently assessed the titles and abstracts of all identified publications. After excluding irrelevant studies and those for which the full text was unavailable, the remaining articles were reviewed in full to determine eligibility based on the predefined criteria. In cases of disagreement, a third reviewer was consulted to reach a consensus. For studies that met the inclusion criteria, the following information was extracted: study title, first author, year of publication, data source (country), sex distribution of the study population, age range, study design, number of participants in the intervention and control groups, treatment duration, outcome measures, and study quality.

2.2.4 Quality assessment

Two researchers independently evaluated the quality of the included literature, and any disagreements were resolved through discussion by a third researcher. The NOS was used to assess the methodological quality of cohort and case-control studies. Studies with NOS scores below the average were defined as low quality (≤3 points), studies with NOS scores around the average were defined as moderate quality (4–6 points), and studies with NOS scores equal to or above the average were defined as high quality (≥7 points).

2.2.5 Data analysis

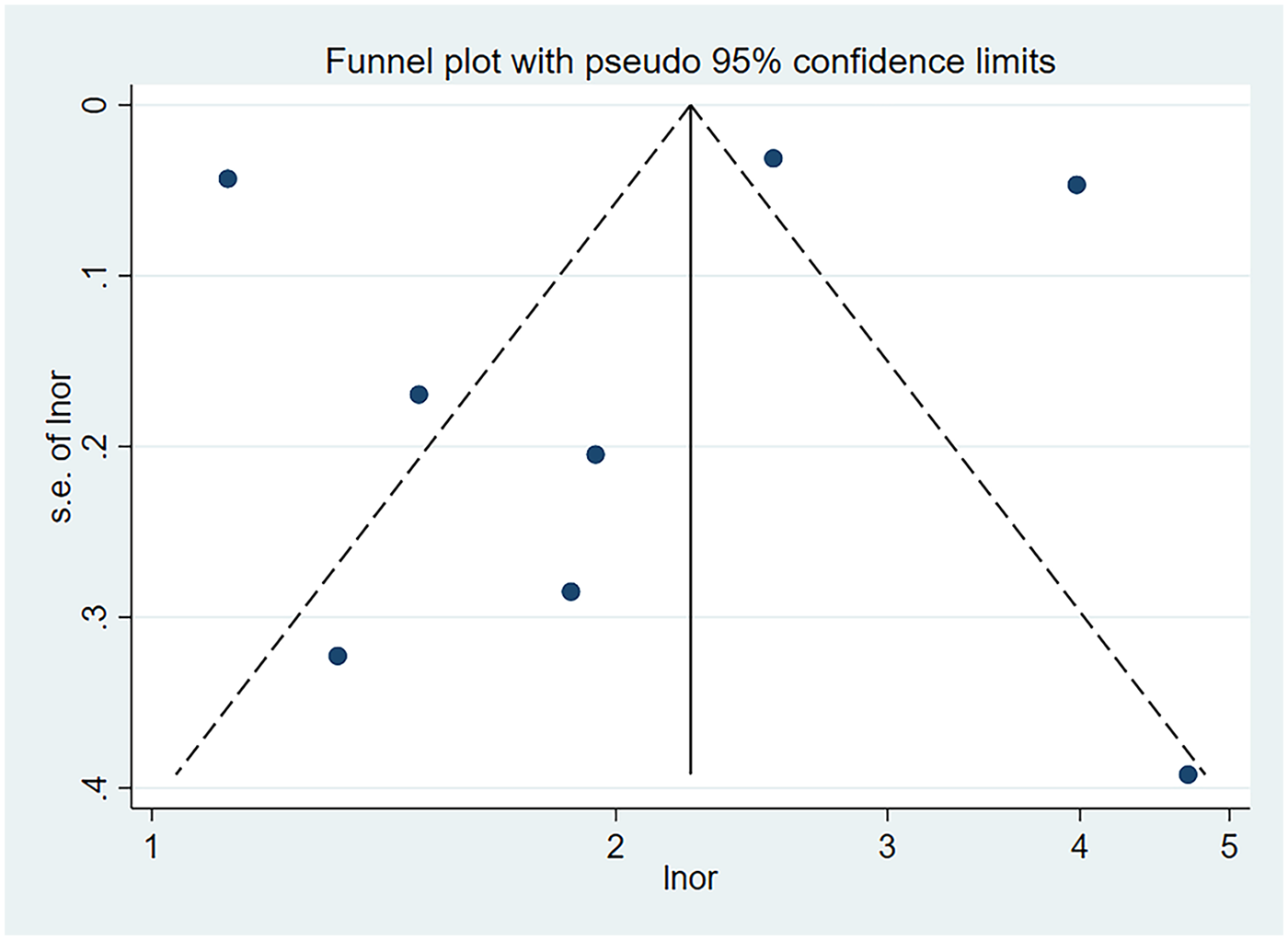

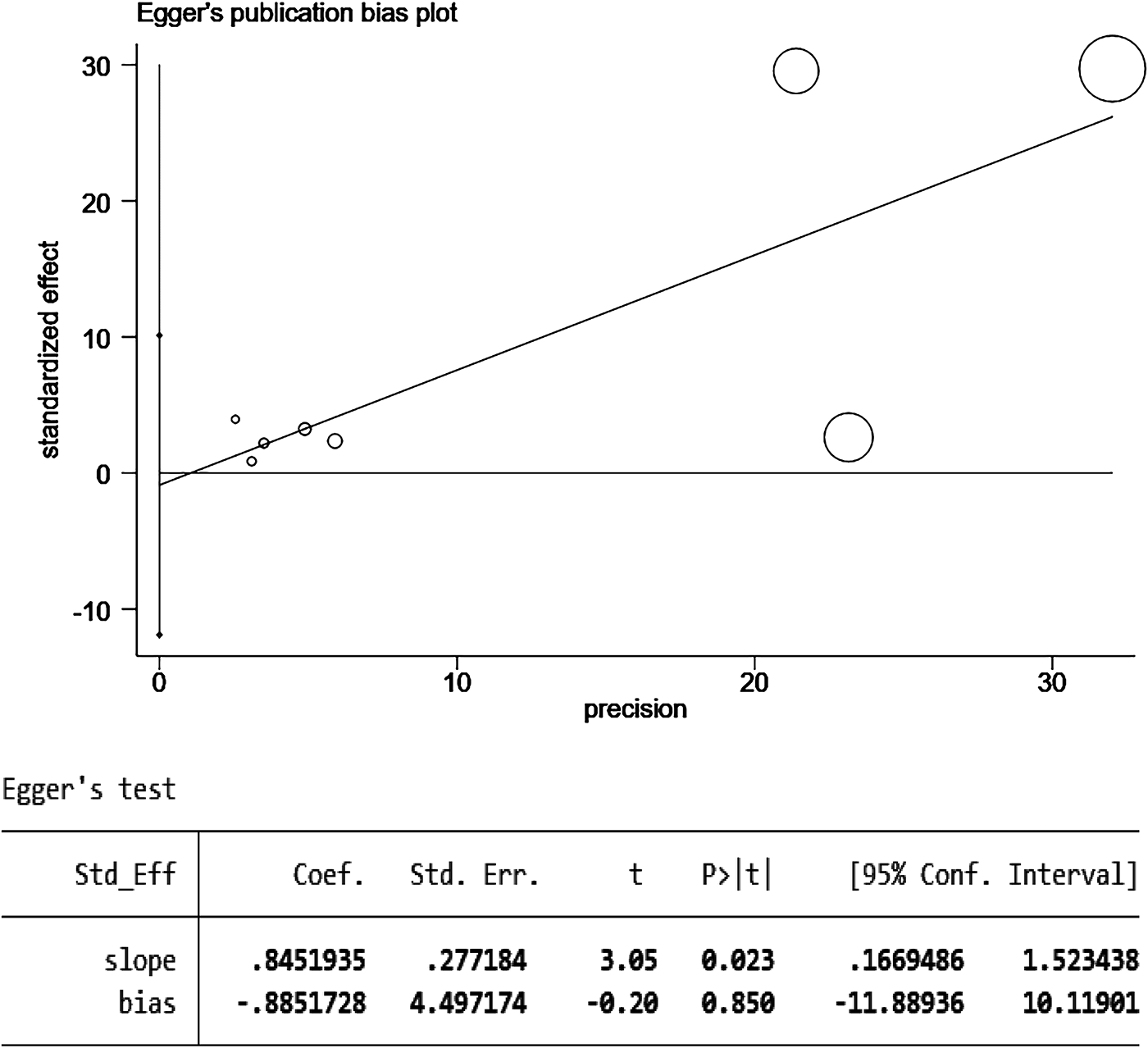

Statistical analyses were performed using RevMan, which was also used to generate forest plots. Adjusted ORs, RRs, and their corresponding 95% CIs reported in the included studies were analyzed. To assess heterogeneity among study results, the I² statistic was calculated. Heterogeneity was interpreted based on the I² value: if no significant heterogeneity was detected (P ≥ 0.1, I² ≤ 50%), a fixed-effects model was applied for meta-analysis (31); otherwise, if significant heterogeneity was present (P < 0.1, I² > 50%), a random-effects model was used, and regression analysis was performed to identify the source of heterogeneity. Sensitivity and subgroup analyses were performed to evaluate the stability of the results (32). Publication bias was assessed using funnel plots and Egger's test, conducted in Stata version 16. For Egger's test, a significance level of α = 0.05 was used, where P < 0.05 indicates the presence of publication bias, and P ≥ 0.05 indicates no significant publication bias.

3 Results

3.1 FAERS database mining

3.1.1 Basic information of olanzapine ADE report

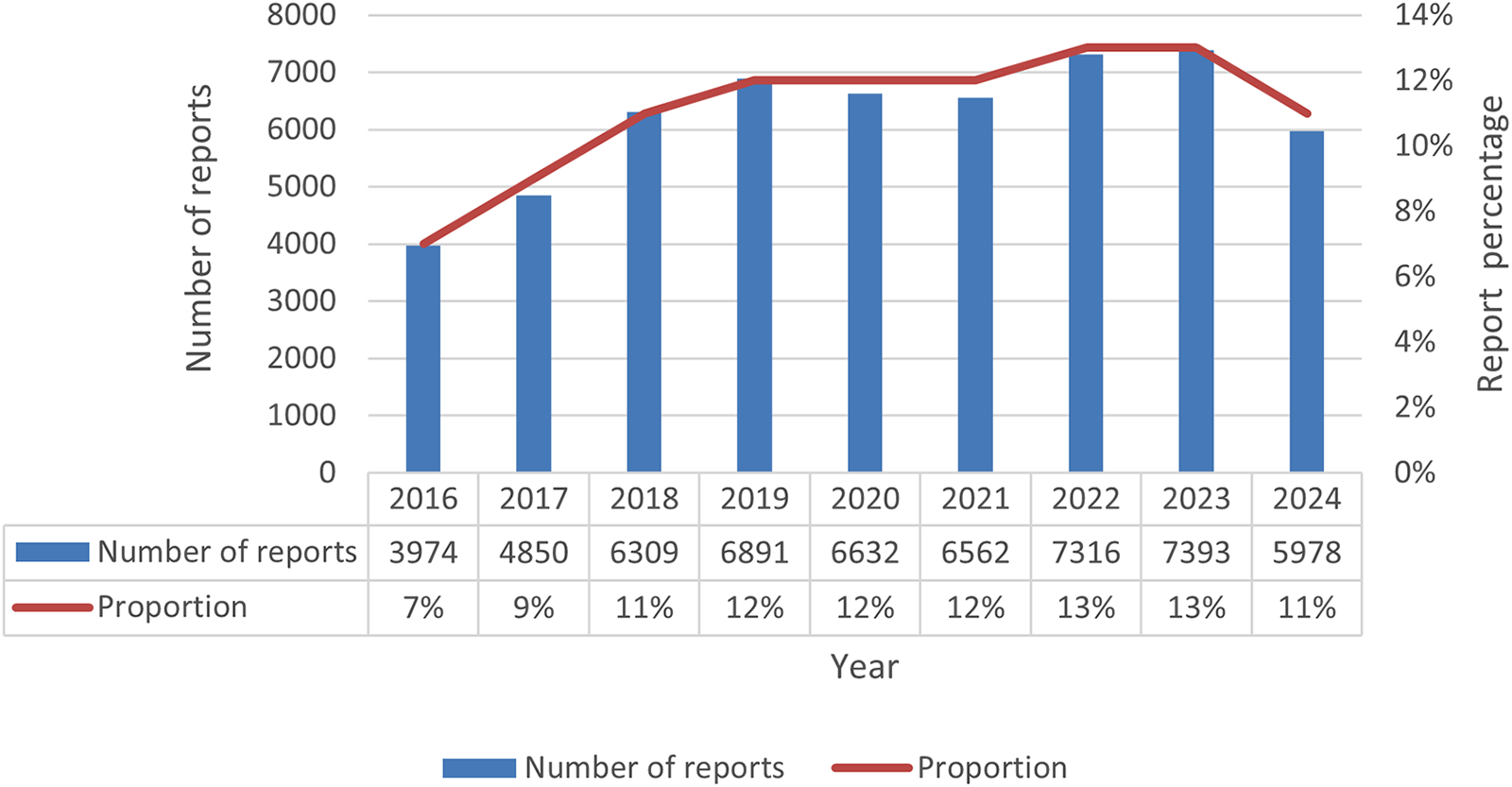

A total of 254,126 olanzapine ADE reports were extracted from the database. After deleting duplicate data and excluding ADEs that could not be assessed, a total of 55,905 ADE reports of olanzapine were screened. The data showed that the number of reports from male patients (45.1%) exceeded that from female patients (43.8%). This difference may be related to the anticholinergic effect of olanzapine, which can increase prolactin concentrations and thus cause breast enlargement and lactation in men (33). A large amount of patient weight information was missing in the reports collected in this study, which may have caused some interference in the assessment of weight-related adverse events (such as weight gain). Among reports with clear age data, the age group with the largest number of reports was 18–64 years old. The reports are mainly sourced from the United States, Canada and the United Kingdom. The majority of reporters were doctors (29.8%). From the perspective of patient outcomes, the main outcomes were hospitalization (2,0471, 36.6%), death (6,375, 11.4%), life-threatening (4,280, 7.7%), disability (960, 1.7%), and other serious events (15,779, 28.2%). This suggests the importance of monitoring olanzapine-related ADEs, as detailed in Table 3. Judging from the distribution of reporting time (Figure 1), the number of reports showed a gradually increasing trend, among which the largest number of reports was submitted in 2,023 (7,393 reports), accounting for 13%. The number of reports was the lowest in 2016 (3,974), accounting for 7%, and increased by 10.3% per year from 2016 to 2023.

Table 3

| Basic Information | Classification | Number of reports (Proportion/%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 24,499 (43.8%) |

| Male | 25,196 (45.1%) | |

| Unknown | 6,210 (11.1%) | |

| Weight | <50 kg | 1,738 (3.1%) |

| 50∼100 kg | 10,510 (18.8%) | |

| >100 kg | 1,786 (3.2%) | |

| Unknown | 41,871 (74.9%) | |

| Age | 18∼40 | 13,341 (23.9%) |

| 41∼64 | 16,306 (29.2%) | |

| 65∼85 | 8,203 (14.7%) | |

| ≥86 | 906 (1.6%) | |

| Unknown | 14,433 (25.8%) | |

| Reporter | Doctor | 16,652 (29.8%) |

| Consumer | 14,325 (25.6%) | |

| Other health professionals | 6,996 (12.5%) | |

| Pharmacist | 4,648 (8.3%) | |

| lawyer | 298 (0.5%) | |

| Unknown | 1,008 (1.8%) | |

| Outcome | Hospitalization | 20,471 (36.6%) |

| Other serious incidents | 15,779 (28.2%) | |

| Death | 6,375 (11.4%) | |

| Life-threatening | 4,280 (7.7%) | |

| Disability | 960 (1.7%) | |

| Congenital malformations | 260 (0.5%) | |

| Intervention is needed to prevent permanent damage | 18 (0.0%) | |

| Unknown | 7,762 (13.9%) | |

| Reporting Country | USA | 16,580 (29.7%) |

| Canada | 6,177 (11.0%) | |

| U.K. | 5,706 (10.2%) | |

| France | 4,164 (7.4%) | |

| Italy | 3,205 (5.7%) | |

| Germany | 2,287 (4.1%) | |

| Japan | 2,248 (4.0%) | |

| China | 1,003 (1.8%) |

Basic information of adverse event reports related to olanzapine.

Figure 1

Number of olanzapine adverse event reports by year.

3.1.2 Distribution of ADE signals in different SOCs

According to the adverse event signal evaluation criteria, a total of 1,261 adverse drug event signals with olanzapine as the primary suspected drug were discovered. After excluding two SOCs (product issues and social environment) that were not directly related to olanzapine-related adverse events, there were 1,233 valid signals remaining, covering 25 SOCs.

According to the ranking of adverse event reports, the top 10 SOCs are mental illness, various neurological diseases, various examinations, various injuries, etc. (Table 4). Among them, the SOCs involved in adverse events not recorded in the instructions include mental illness (suicidal behavior), various examinations (prolonged QT interval of electrocardiogram, increased blood creatine phosphokinase), metabolic and nutritional diseases (hyponatremia), heart diseases (myocarditis, cardiomyopathy), blood and lymphatic system diseases (febrile neutropenia, leukocytosis), respiratory system, chest and mediastinal diseases (pulmonary embolism).

Table 4

| SOC | Number of PTs | Adverse event reports | PT (top 5 Cases) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychiatric | 251 | 34,755 | Suicidal behavior* (2,030), Confusional state (1,717), Substance abuse (1,605), Schizophrenia (1,595), Psychotic disorder (1,496) |

| Various neurological diseases | 186 | 24,807 | Somnolence (2,294), Sedation (1,743), Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (1,425), Tremor (1,401), Akathisia (1,141) |

| Various inspections | 191 | 12,084 | Weight gain (2,718), prolonged QT interval on electrocardiogram* (1,424), increased blood creatine phosphokinase* (538), abnormal blood prolactin (529), decreased neutrophil count (492) |

| Various injuries, poisoning and procedural complications | 49 | 6,485 | Toxicity of various preparations (2,993), intentional overdose (1,634), medication errors (340), prescription overdose (252), intentional poisoning (250) |

| Systemic diseases and administration site reactions | 41 | 5,696 | Drug interactions (2,567), treatment noncompliance (839), hypothermia (349), drug resistance (298), hyperthermia (206) |

| Metabolic and nutritional diseases | 53 | 4,934 | Hyponatremia* (743), Diabetes (547), Metabolic disorders (515), Obesity (475), Increased appetite (440) |

| Heart disease | 61 | 4,637 | Tachycardia (1,288), Myocarditis* (526), Cardiorespiratory arrest (417), Sinus tachycardia (317), Cardiomyopathy* (184) |

| Blood and lymphatic system diseases | 24 | 4,070 | Neutropenia (1,310), febrile neutropenia* (998), leukopenia (666), agranulocytosis (304), leukocytosis* (204) |

| Respiratory, thoracic and mediastinal diseases | 47 | 2,843 | Pulmonary embolism* (718), respiratory depression (306), respiratory distress (197), respiratory arrest (193), aspiration (160) |

| Reproductive system and breast diseases | 26 | 2,021 | Sexual dysfunction (678), male breast development (386), erectile dysfunction (195), priapism (146), amenorrhea (143) |

Top 10 SOCs with the highest number of olanzapine adverse event reports.

Adverse events not listed in the instructions.

PT, Preferred Term; SOC, System Organ Class.

3.1.3 Analysis of olanzapine-related ADE signal intensity

ADE signal strength was screened using the reporting ROR and PRR methods, resulting in the identification of 1,233 eligible preferred terms (PTs) with a cumulative total of 113,271 reports. After excluding PTs that were clearly unrelated to the drug, product issues, and olanzapine's indications, the top 50 PTs were selected based on the number of reported cases (Table 5). The top five most frequently reported symptoms were weight gain, drowsiness, suicidal behavior, sedation, and confusion. To assess whether these signals were included in the drug label, the top 50 adverse events were compared with the latest olanzapine prescribing information (updated in 2025) from the FDA Label on the official FDA website, supplemented by a review of primary literature on related adverse events to verify their inclusion (34). The comparison revealed that 39 of the top 50 PTs were explicitly mentioned in the FDA label, demonstrating high consistency with the adverse events identified in this study and supporting the credibility and clinical relevance of the mined signals. The remaining 11 PTs were not mentioned in the label and may represent potential new signals; these included suicidal behavior, prolonged QT interval on electrocardiogram, febrile neutropenia, delirium, hyponatremia, pulmonary embolism, attention disorder, catatonia, abnormal blood prolactin levels, myocarditis, infectious aspiration pneumonia, and excessive salivation, indicating that these signals warrant further investigation and validation.

Table 5

| No. | PT | Number of cases | ROR (95%CI) | PRR (χ2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Weight gain | 2,718 | 3.15 (3.03–3.27) | 3.13 (3,862.08) |

| 2 | Lethargy | 2,294 | 2.96 (2.84–3.09) | 2.95 (2,897.14) |

| 3 | Committing suicidal behavior* | 2,030 | 9.84 (9.41–10.3) | 9.77 (14,956.21) |

| 4 | Sedation | 1,743 | 21.55 (20.49–22.67) | 21.41 (29,419.86) |

| 5 | Confusion | 1,717 | 2.84 (2.71–2.98) | 2.83 (1,996.53) |

| 6 | Neuroleptic malignant syndrome | 1,425 | 46.62 (43.91–49.51) | 46.37 (47,501.45) |

| 7 | Electrocardiogram (ECG) QT interval prolongation* | 1,424 | 9.82 (9.3–10.36) | 9.77 (10,480.29) |

| 8 | Tremor | 1,401 | 2.32 (2.2–2.44) | 2.31 (1,027.92) |

| 9 | Suicidal thoughts | 1,323 | 4.19 (3.97–4.43) | 4.18 (3,107.04) |

| 10 | Neutropenia | 1,310 | 2.13 (2.02–2.25) | 2.13 (771.12) |

| 11 | Tachycardia | 1,288 | 3.92 (3.71–4.14) | 3.9 (2,707.68) |

| 12 | Suicide | 1,243 | 4.58 (4.32–4.84) | 4.56 (3,347.63) |

| 13 | Akathisia | 1,141 | 28.1 (26.36–29.94) | 27.97 (24,731.18) |

| 14 | Extrapyramidal disorders | 1,106 | 30.28 (28.37–32.32) | 30.15 (25,644.76) |

| 15 | Deliberate self-harm | 1,004 | 10.67 (10–11.38) | 10.63 (8,142.73) |

| 16 | Febrile neutropenia* | 998 | 3.64 (3.41–3.87) | 3.62 (1,851.04) |

| 17 | Movement disorders | 997 | 7.28 (6.83–7.76) | 7.26 (5,117.86) |

| 18 | Dystonia | 954 | 24.18 (22.57–25.91) | 24.1 (18,015.5) |

| 19 | Coma | 939 | 5.45 (5.11–5.82) | 5.44 (3,275.91) |

| 20 | Decreased level of consciousness | 916 | 6.59 (6.16–7.04) | 6.57 (4,130.38) |

| 21 | Sleep | 900 | 14.98 (13.98–16.04) | 14.93 (10,567.68) |

| 22 | delirium* | 822 | 6.45 (6.01–6.92) | 6.43 (3,607.71) |

| 23 | Parkinson's disease | 746 | 24.86 (22.99–26.87) | 24.79 (14,465.81) |

| 24 | Hyponatremia* | 743 | 3.54 (3.29–3.81) | 3.54 (1,319.29) |

| 25 | Pulmonary embolism* | 718 | 2.45 (2.28–2.64) | 2.45 (604.72) |

| 26 | Restlessness | 693 | 5.28 (4.9–5.7) | 5.27 (2,313.2) |

| 27 | Sexual dysfunction | 678 | 19.02 (17.55–20.61) | 18.97 (10,162.87) |

| 28 | Leukopenia | 666 | 3.45 (3.19–3.72) | 3.44 (1,126.93) |

| 29 | Rhabdomyolysis | 630 | 4.71 (4.35–5.1) | 4.7 (1,774.67) |

| 30 | Attention deficit disorder* | 591 | 2.85 (2.62–3.09) | 2.84 (692.45) |

| 31 | Cognitive impairment | 587 | 3.13 (2.88–3.39) | 3.12 (827.94) |

| 32 | Catatonia* | 584 | 35.25 (32.19–38.6) | 35.17 (15,490.87) |

| 33 | Diabetes | 547 | 2.11 (1.94–2.3) | 2.11 (314.62) |

| 34 | Mental damage | 541 | 6.16 (5.65–6.71) | 6.15 (2,234.58) |

| 35 | Elevated blood creatine phosphokinase | 538 | 6.56 (6.02–7.15) | 6.55 (2,416.84) |

| 36 | Dysarthria | 533 | 4.15 (3.81–4.53) | 4.15 (1,235.94) |

| 37 | Abnormal blood prolactin* | 529 | 406.96 (343.86–481.64) | 406.12 (54,723.54) |

| 38 | Myocarditis* | 526 | 11.41 (10.44–12.47) | 11.39 (4,609.25) |

| 39 | Tardive dyskinesia | 523 | 13 (11.88–14.22) | 12.97 (5,289.94) |

| 40 | Abnormal behavior | 520 | 4.49 (4.11–4.9) | 4.48 (1,362.99) |

| 41 | Metabolic disorders | 515 | 33.09 (30.06–36.43) | 33.02 (12,936.17) |

| 42 | Personality changes | 501 | 17.69 (16.12–19.42) | 17.66 (6,991) |

| 43 | Infectious aspiration pneumonia* | 498 | 5.11 (4.67–5.59) | 5.1 (1,584.35) |

| 44 | Decreased neutrophil count | 492 | 2.87 (2.62–3.13) | 2.86 (584.56) |

| 45 | Speech disorders | 484 | 2.51 (2.29–2.74) | 2.5 (430.15) |

| 46 | Irritability | 476 | 2.19 (2–2.39) | 2.18 (301.34) |

| 47 | Obesity | 475 | 7.67 (7–8.42) | 7.66 (2,608.31) |

| 48 | Serotonin syndrome | 475 | 6.8 (6.2–7.46) | 6.79 (2,236.97) |

| 49 | Excessive salivation* | 472 | 13.47 (12.26–14.81) | 13.45 (4,961.8) |

| 50 | Hyperprolactinemia | 468 | 16.34 (14.85–17.98) | 16.31 (6,023.78) |

Top 50 PTs with the highest number of adverse events associated with olanzapine.

Adverse events not listed in the instructions.

PT, Preferred Term; PRR, Proportional Reporting Ratio; ROR, Reporting Odds Ratio.

3.1.4 Analysis of ADE signal intensity in olanzapine-related embolism and thrombosis

After a secondary search of embolism and thrombosis, it was found that there were 9 PTs related to embolism risk associated with olanzapine, with 843 cases. The top three PTs in terms of case numbers were pulmonary embolism [718 cases, ROR (95% CI): 2.45 (2.28, 2.64), PRR (χ2): 2.45 (604.72)], venous embolism [73 cases, ROR (95% CI): 5.67 (4.49, 7.17), PRR (χ2): 5.67 (270.03)], and embolism [28 cases, ROR (95% CI): 0.94 (0.64, 1.36), PRR (χ2): 0.94 (0.12)]. Detailed data are shown in Table 6.

Table 6

| No. | PT | Number of cases | ROR (95%CI) | PRR (χ2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pulmonary embolism* | 718 | 2.45 (2.28–2.64) | 2.45 (604.72) |

| 2 | Venous embolism* | 73 | 5.67 (4.49–7.17) | 5.67 (270.03) |

| 3 | Emboembolism* | 28 | 0.94 (0.64–1.36) | 0.94 (0.12) |

| 4 | Paradoxical embolism* | 10 | 35.83 (17.89–71.77) | 35.83 (269.45) |

| 5 | Arterial embolism* | 8 | 2.5 (1.24–5.03) | 2.5 (7.08) |

| 6 | Peripheral embolism* | 2 | 0.6 (0.15–2.41) | 0.6 (0.53) |

| 7 | Air embolism* | 2 | 1.27 (0.32–5.11) | 1.27 (0.11) |

| 8 | Cerebral arterial embolism* | 1 | 0.25 (0.04–1.79) | 0.25 (2.22) |

| 9 | Cerebral air embolism* | 1 | 17.47 (2.18–139.65) | 17.47 (13.8) |

PTs with signal intensity of thrombotic and embolic risk in olanzapine.

Adverse events not listed in the instructions.

PT, Preferred Term; PRR, Proportional Reporting Ratio; ROR, Reporting Odds Ratio.

3.2 Meta-analysis

3.2.1 Literature search results

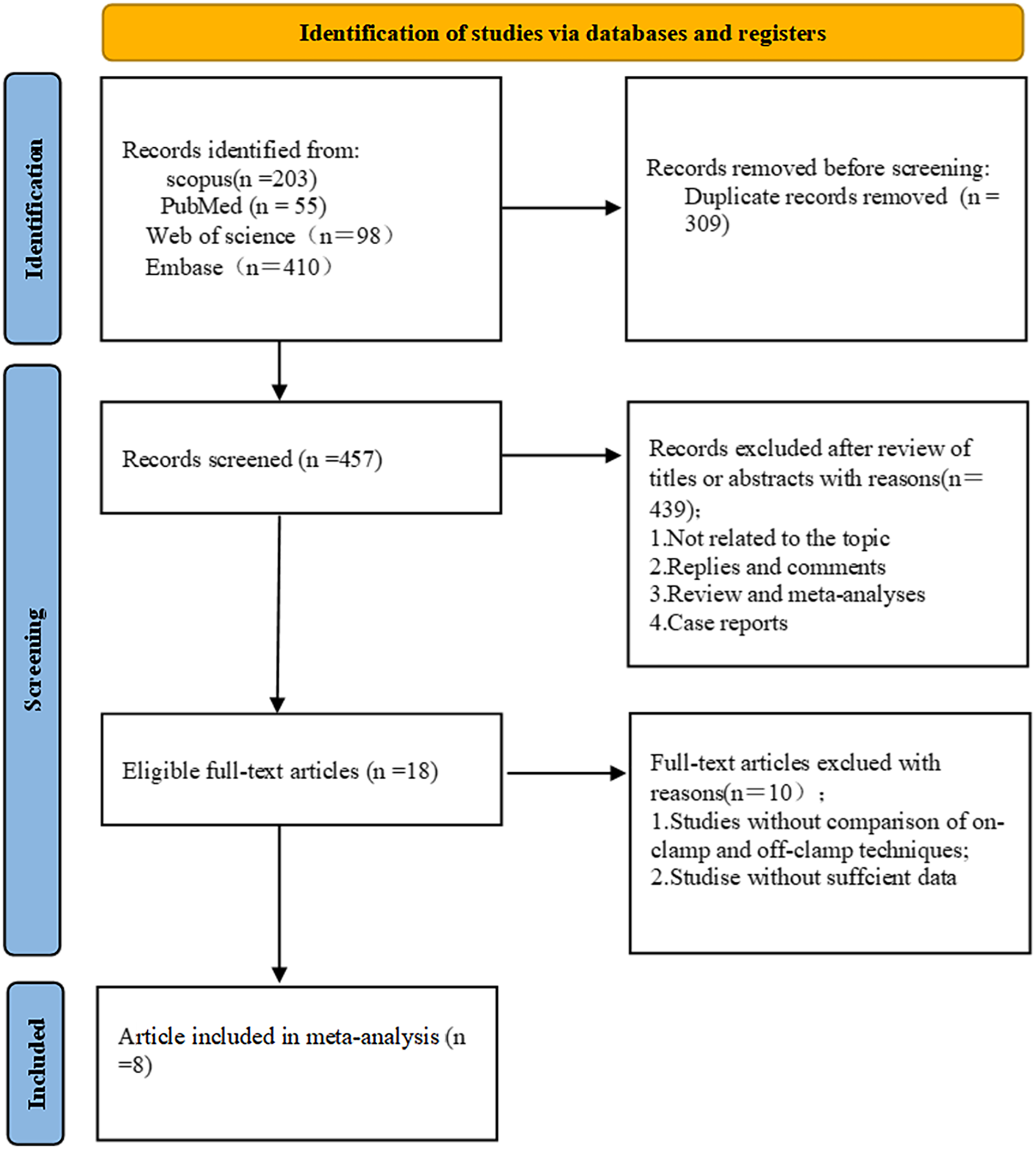

Using the search strategy mentioned in the method, a preliminary search obtained 766 articles, 309 duplicates were removed, 391 articles were excluded by reading the title and abstract, 46 reviews were excluded, 2 letters were excluded, and 10 articles without sufficient data or control group were excluded. Finally, 8 articles were included. The results are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Literature screening flow chart.

3.2.2 Basic characteristics and quality evaluation of included studies

A total of eight observational studies were included in the meta-analysis (15, 35–41). Of these studies, one was conducted in Asia, three in Europe, and four in the United States. The basic characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 7. The quality of the included studies was evaluated, and the results are shown in Table 8. The average score of the 8 studies was 7.75, indicating that the quality was high and suitable for meta-analysis.

Table 7

| Study title | Author | Data source | Year of publication | Design type | Gender (Male/female) | Age | Course of treatment | Outcome index | Article quality | OR value | Population of intervention group and control group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antipsychotic drugs and risk of pulmonary embolism | Allenet (41) | ‘Premier's Perspective’ database (US clinical and economic database from about 500 acute care hospitals) | 2012 | Retrospective cohort study | Intervention group: 57% control group: 90% |

50–60 years old | Unclear | PE | Medium quality | 1.12[1.03,1.22] | Intervention group: 69,975 Control group: 28,272,820 |

| Antipsychotic drugs and risk of idiopathic venous thromboembolism: a nested case-control study using the CPRD | Ishiguro (40) | Clinical Practice Research Datalink | 2014 | Nested case-control studies | Intervention group: 51% control group: 49% |

Ages 20 to 59 | 14 years | VTE | High quality | 1.32[0.71,2.48] | Intervention group: 16 Control group: 41 |

| Antipsychotics and VTE Risk in Postmenopausal Women: Nested Case-Control Study | Wang (46) | Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database | 2016 | Nested case-control studies | The subjects were all female | ≥50 years old | Unclear | VTE | High quality | 4.7[2.18,10.14] | Intervention group: 10 Control group: 34 |

| Antipsychotic drugs and risk of venous thromboembolism: nested case-control study | Parker (42) | QResearch database | 2010 | Nested case-control studies | Intervention group: 79% control group: 79% |

53–77 years old | 3 months | VTE | High quality | 1.49[1.07,2.08] | Intervention group: 102 Control group: 223 |

| Venous thromboembolism among elderly patients treated with atypical and conventional antipsychotic agents | Liperoti (20) | Systematic Assessment of Geriatric Drug Use via Epidemiology (SAGE) database, which contains data from the Minimum Data Set (MDS) | 2005 | Retrospective cohort study | Intervention group: 42% control group: 34% |

7,762 (13.9%) | 6 months | VTE | High quality | 1.87[1.06,3.27] | Intervention group: 2,825 Control group: 112,078 |

| 7,762 (13.9%) | |||||||||||

| Antipsychotics and VTE: Pharmacovigilance Insights from FDA | Y. Yan (45) | FAERS database from 2004 to 2021 | 2024 | cohort study | Intervention group: 108% control group: 116% |

18 −64 years old | Unclear | VTE | Medium quality | 2.53 [2.38,2.69] | Intervention group: 1034 Control group: 37,754 |

| A pharmacoepidemiological nested case-control study of risk factors for venous thromboembolism with the focus on diabetes, cancer, socioeconomic group, medications, and comorbidities | Myllylahti (44) | Primary study of FIN-CARING2 | 2024 | Nested case-control studies | Intervention group: 99% control group: 98% |

Around 66 years old | 16 years | VTE | High quality | 1.94 [1.30,2.90] | Intervention group: 52 Control group: 84 |

| Association between antipsychotics and pulmonary embolism: a pharmacovigilance analysis | Huang (43) | Reporting System (FAERS), from the first quarter of 2018 to the first quarter of 2023 | 2024 | cohort study | Intervention group: 102% | 20 −89 years old | 30 days | PE | High quality | 3.98[3.63,4.36] | Intervention group: 461 Control group: 25,891 |

Basic characteristics of included studies.

Table 8

| study | Ishiguro 2014 | Wang 2016 | Parker 2010 | Myllylahti 2024 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Is the case definition adequate | * | * | * | * |

| Representativeness of cases | * | * | * | * |

| Selection of controls | * | * | * | * |

| Definition of controls | * | * | * | * |

| Comparability of cases and controls on the basis of the design or analysis | * | ** | ** | * |

| Ascertain ment of exposure | * | * | * | * |

| Same method of ascertainment of exposure | * | * | * | * |

| Nonresponse rate | * | * | * | * |

| Total | 8 | 9 | 9 | 8 |

| NOS for Assessment of Quality of Included Studies: Cohort Studies | ||||

| study | Liperoti 2005 | Allent 2012 | Huang 2024 | Yan 2024 |

| Representativeness of exposed cohort? | * | * | * | * |

| Selection of the nonexposed cohort? | * | - | * | * |

| Ascertainment of exposure? | * | * | * | * |

| Demonstration that outcome of interest was not represent at the start of the study | - | - | * | - |

| Comparability of Cohort | ** | ** | * | * |

| Assessment of outcome | * | * | * | * |

| Was follow up long enough for outcomes to occur | * | - | * | * |

| Adequacy of follow up of cohorts | * | * | * | - |

| Total | 8 | 6 | 8 | 6 |

NOS quality rating table.

NOS for Assessment of Quality of Included Studies: Cohort Studies.

3.2.3 Main outcome measures

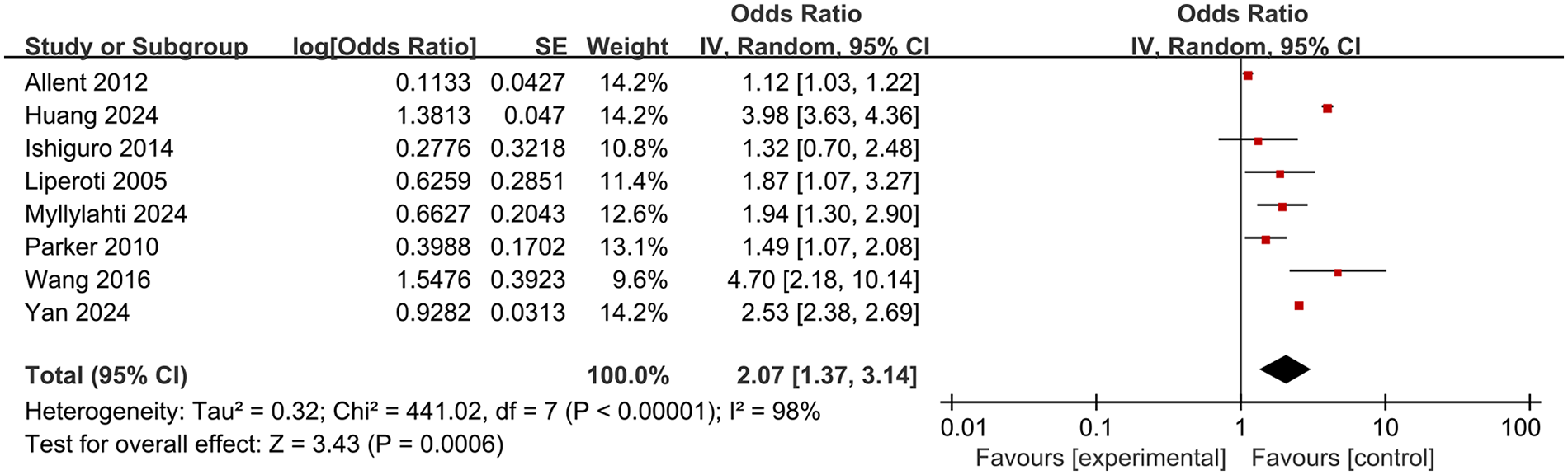

A total of 8 studies were included in this meta-analysis to explore the association between olanzapine use and the risk of pulmonary embolism and venous thromboembolism. Due to the large statistical heterogeneity (heterogeneity test P < 0.00001, I2 = 98%), a random effects model was used for Meta-analysis, and the combined effect was statistically significant (OR 2.07, 95% CI 1.37–3.14; P = 0.0006), indicating that the use of olanzapine in patients with schizophrenia or mania will significantly increase the risk of PE and VTE. The results are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3

Meta-analysis forest plot of the risk of pulmonary embolism or venous thromboembolism in patients with schizophrenia or mania taking olanzapine.

3.2.4 Meta-regression analysis

To explore potential sources of heterogeneity among studies, we performed a meta-regression analysis using disease type, age, race, follow-up duration, study type, and literature quality as covariates. As shown in Table 9, none of the covariates significantly contributed to the heterogeneity of the results.

Table 9

| Covariate | exp(b) | Std.Err. | t | P | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease type | 0.951 | 0.514 | −0.09 | 0.934 | 0.093–9.730 |

| Age | 0.613 | 0.275 | −1.09 | 0.389 | 0.089–4.212 |

| Race/ Study type | 0.936 | 0.582 | −0.11 | 0.925 | 0.065–13.568 |

| Follow-up time | 0.566 | 0.222 | −1.45 | 0.283 | 0.105–3.052 |

| Literature quality | 2.921 | 1.934 | 1.62 | 0.247 | 0.169–50.456 |

Meta-regression analysis.

3.2.5 Subgroup analysis

To evaluate the stability of the results, subgroup analysis was also performed. The subgroup analysis was performed as follows: (1) study type (2) quality of the literature (3) follow-up time (4) race (5) age and (6) disease type. Subgroup analysis showed that the results were relatively stable. Grouping by research type, follow-up time, race, and age did not affect the stability of the results. However, grouping by literature quality and disease type did affect the stability of the results. When grouped according to the quality of the literature, there was no statistically significant difference in the medium-quality literature subgroup (OR 1.68, 95% CI 0.76–3.74; P = 0.20). This may be due to the moderate quality of the included literature. In addition, when grouped by disease type, the subgroup with venous thromboembolism as the disease type (OR 2.04, 95% CI 1.53–2.73; P < 0.00001) had a statistically significant difference, indicating that the data support that the use of olanzapine in patients with schizophrenia or mania increases the risk of VTE. There was no significant difference in the subgroup with pulmonary embolism (OR 2.11, 95% CI 0.63–7.31; P = 0.24). The reason for the effect may be due to the small number of included literature. The risk of PE in patients was compared with the risk of VTE in patients. Although the OR value of PE was slightly higher than that of VTE, the data were not statistically significant and the heterogeneity of the PE subgroup (I² = 100%) was higher than that of the VTE subgroup (I² = 73%), indicating that the stability of the results of the PE subgroup was worse. Therefore, overall, the association between olanzapine use and VTE is slightly stronger than that between olanzapine use and PE. In addition, when grouped according to follow-up time, it was found that patients with a follow-up time of more than 1 year had a slightly lower risk (OR 1.73, 95% CI 1.23–2.44; P = 0.002), which may be related to metabolism. The results of subgroup analysis are shown in Supplementary Figure S2.

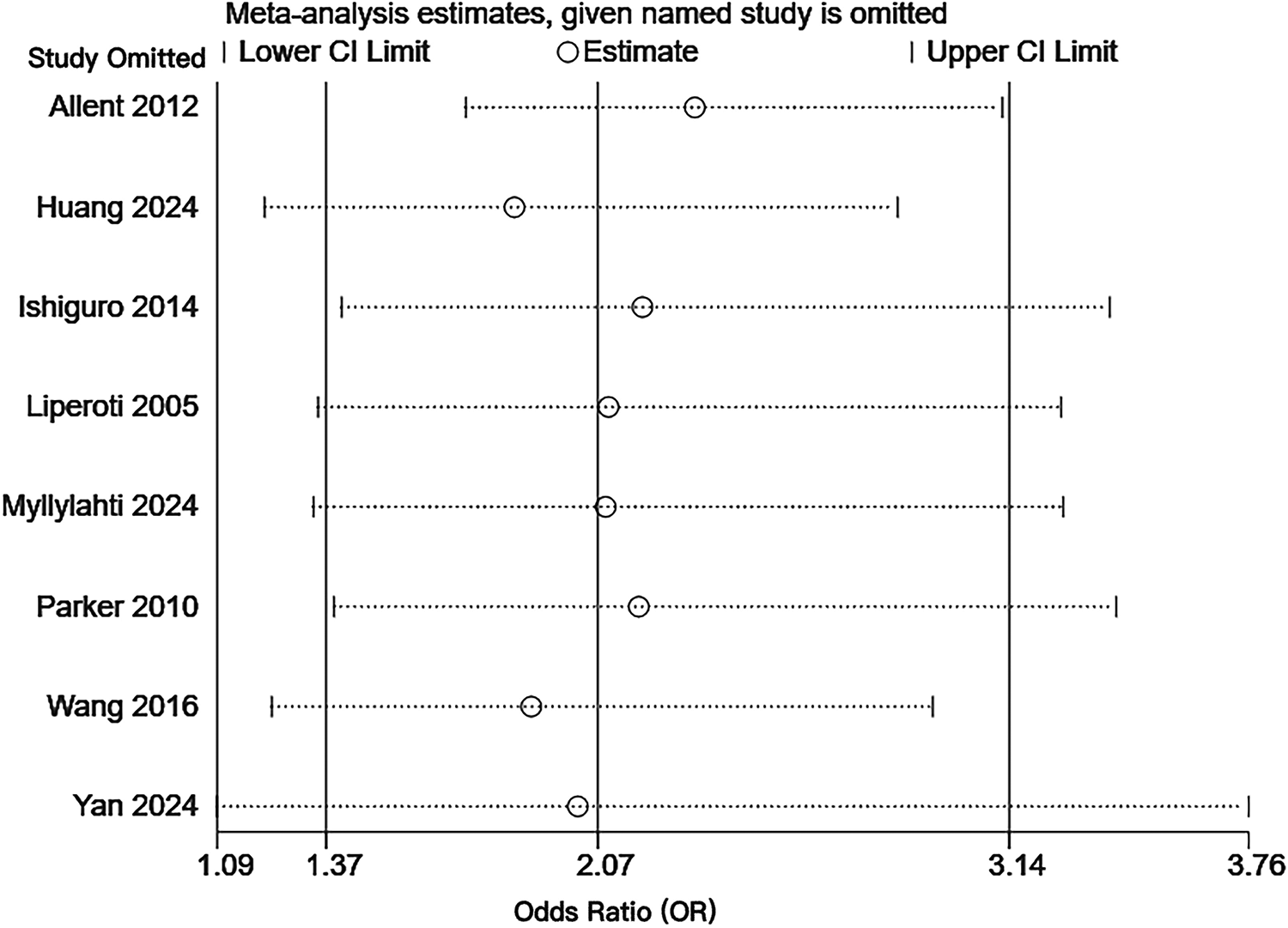

3.2.6 Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis was performed by eliminating individual articles one by one. After excluding each individual study in turn, the combined effect size was analyzed separately. It was found that the result range of the OR value of each combined effect size remained at 95%CI (1.37–3.14), the combined result did not change significantly, and the confidence interval of each combined effect size did not cross the ineffectiveness line. The results were statistically significant, and the overall trend of each combined effect size did not change, indicating that the results were relatively stable. The results of the sensitivity analysis are shown in Figure 4. Detailed data of the sensitivity analysis using Stata software are shown in Table 10.

Figure 4

Sensitivity analysis of the risk of pulmonary embolism or venous thromboembolism in patients with schizophrenia or mania taking olanzapine.

Table 10

| Study omitted | Estimate | [95% Cl] | I 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Allent 2012 | 2.32,51,377 | 1.73,15,247 | 3.12,22,571 94% |

| Huang 2024 | 1.85,75,449 | 1.21,01,998 | 2.85,11,598 98% |

| Ishiguro 2014 | 2.18,94,292 | 1.40,95,607 | 3.40,07,762 99% |

| Liperoti 2005 | 2.10,14,549 | 1.34,86,848 | 3.27,43,848 99% |

| Myllylahti 2024 | 2.094001 | 1.33,66,722 | 3.28,04,156 99% |

| Parker 2010 | 2.17,97,236 | 1.39,01,326 | 3.41,77,999 99% |

| Wang 2016 | 1.901185 | 1.22,86,693 | 2.94,18,042 99% |

| Yan 2024 | 2.02,17,985 | 1.08,68,746 | 3.760939 99% |

| Combined | 2.07,35,739 | 1.36,92,355 | 3.14,02,259 98% |

Sensitivity analysis data.

3.2.7 Publication bias

The results of the funnel plot are shown in Figure 5. All studies are distributed in the funnel plot and the scatter points are roughly symmetrical, suggesting that the publication bias of each study is small, indicating that the bias of the literature included in this study is well controlled. In order to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the study, it is necessary to conduct the Egger test. After the Egger test, it was found that P = 0.850 > 0.05, indicating that there was no obvious publication bias among the included literature in the study on the correlation between schizophrenia and mania patients using olanzapine and the occurrence of venous thromboembolism and pulmonary embolism. The results are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 5

Funnel plot of the risk of pulmonary embolism or venous thromboembolism in patients with schizophrenia or mania taking olanzapine.

Figure 6

Egger test for the risk of pulmonary embolism or venous thromboembolism in patients with schizophrenia or mania taking olanzapine.

4 Discussion

This study is the first to combine FAERS database signal mining with a systematic meta-analysis of PE and VTE to explore the potential thrombotic adverse events of olanzapine.

FAERS data showed that a total of 55,905 olanzapine-related reports were included in this study. Basic information shows that there are more male patients than female patients (1:0.97), suggesting that male patients should pay more attention to medication risks. Basic information shows that the 18–40 age group (23.9%,95% CI:23.6%–24.2%) and the 41–64 age group (29.2%,95%CI:28.8%–29.6%) are the main reporting populations. Meanwhile, patients aged 65 and above (65–85 years old account for 14.7%,95% CI:14.4%–15.0% and ≥86 years old account for 1.6%,95% CI:1.5%–1.7%) also constitute a significant proportion. The 41–64 age group has the highest proportion and is the core population for olanzapine-related adverse event reports; the risk in this age group deserves special attention. This age group often faces high work pressure, sedentary lifestyles, and other lifestyle problems. Some individuals may already have underlying conditions such as early-stage hypertension and dyslipidemia. Olanzapine-induced metabolic disorders (such as obesity and dyslipidemia) and venous congestion significantly increase the risk of thrombosis. The elderly population over 65 years of age already has a higher risk of thrombosis due to underlying conditions such as hypertension and diabetes, decreased vascular function, and venous congestion. Olanzapine-induced metabolic abnormalities further exacerbate this risk. After comparing the drug instructions, it was found that olanzapine-related pulmonary embolism signals ranked 25th among all adverse events and were not clearly recorded in the adverse reactions in the instructions. In addition, there are 11 ADE signals among the top 50 reported cases that are not included in the olanzapine drug instructions, and the rest include suicidal behavior, electrocardiogram QT interval prolongation, febrile neutropenia, delirium, hyponatremia, attention disorder, tension, abnormal blood prolactin, myocarditis, infectious aspiration pneumonia, and excessive salivation. Therefore, when olanzapine is used clinically to treat schizophrenia, the above-mentioned ADEs should be taken seriously and differentiated from primary diseases. A secondary search revealed that the ROR values of olanzapine for pulmonary embolism and venous embolism were relatively high, namely pulmonary embolism [ROR (95% CI): 2.45 (2.28, 2.64)] and venous embolism [ROR (95% CI): 5.67 (4.49, 7.17)], and venous embolism was also an adverse reaction not clearly recorded in the instructions. Among the 25 SOCs, the top 10 in terms of reporting cases are psychiatric diseases, various neurological diseases, various examinations, various injuries and procedural complications, systemic diseases, and various reactions at the administration site. Among them, the ADE signals of mental illnesses, various nervous system diseases and various examinations mostly overlap with the known pharmacological effects of olanzapine. Therefore, it is necessary to focus on adverse event signals that are not included in the instructions in SOCs such as metabolic and nutritional diseases, cardiac diseases, blood and lymphatic system diseases and respiratory system diseases.

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses demonstrated that patients treated with olanzapine had a significantly increased risk of VTE and PE compared to those not receiving olanzapine (OR 2.07, 95% CI 1.37–3.14; P = 0.0006). This finding was consistent with the signal strength observed in the FAERS database, where the reporting odds ratio (ROR) for pulmonary embolism and venous embolism was 2.45 and 5.67, respectively, further supporting an elevated thrombotic risk. These results reinforce the reliability of the FAERS signal detection outcomes. Subgroup analysis indicated that in the medium-quality literature subgroup, the association did not reach statistical significance (OR 1.68, 95% CI 0.76–3.74; P = 0.20), possibly due to methodological limitations such as lower study quality and unclear follow-up durations. Furthermore, in the subgroup analysis by disease type, the PE subgroup (OR 2.11, 95% CI 0.61–7.31; P = 0.24) did not achieve statistical significance, which may be attributed to the limited number of included studies (n = 2) and high heterogeneity (I² = 100%), suggesting limited robustness of the results. In contrast, the VTE subgroup included 6 studies with a pooled OR (OR 2.04, 95% CI 1.53–2.73; P < 0.00001) and lower heterogeneity than the PE subgroup (I² = 73%). This difference in values suggests that the association between olanzapine and VTE may be slightly stronger than that between olanzapine and PE. This may be due to the higher clinical diagnosis rate of VTE and more complete data from included studies, whereas PE presents rapidly, with some cases remaining undiagnosed, leading to insufficient sample size. The above shows that although the overall use of olanzapine is significantly associated with an increased risk of venous thromboembolism and pulmonary embolism, the differences in results between different subgroups suggest that we need to consider the influence of literature quality and disease type when interpreting the conclusions.

However, the interpretation of these results must take into account the potential confounding factors inherent in the nature of the data source observations. First, patients with mental illnesses (such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder) often have lifestyle-related risks such as sedentary lifestyles, smoking, and poor diet, which can induce venous stasis and a hypercoagulable state (42). Furthermore, mental illness itself is associated with chronic low-grade inflammation and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis dysfunction, and these pathological conditions may independently promote thrombosis (43). Second, olanzapine is used to prevent chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) in cancer patients, and malignancy, through tumor cell-induced coagulation activation, is a major risk factor for VTE (44). Therefore, we used MedDRA® version 26.0 standardized coding to perform a “malignancy” specific search on olanzapine-related adverse event reports in the FAERS database. The results showed that only 229 reports (0.4%) explicitly documented malignancy. Although the FAERS database contains spontaneously reported cases, and some reports lack complete comorbidity information, the proportion of recorded malignant tumor cases is extremely low, suggesting that this factor is not the primary driver of the observed thrombotic signals. Furthermore, in the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the meta-analysis, we explicitly limited the study population to patients diagnosed with schizophrenia or mania, and excluded studies involving patients with malignant tumors or those using olanzapine due to chemotherapy-related nausea and vomiting (CINV). This rigorous screening ensured that the meta-analysis results came from populations without concomitant malignant tumors, directly supporting the association between olanzapine and thrombotic risk independent of cancer factors. We acknowledge that incomplete comorbidity documentation in the FAERS database may lead to unrecorded malignant cases, which is a potential limitation of this study. Future studies will employ a prospective cohort design, explicitly screening and excluding patients with malignant tumors at enrollment, collecting detailed information such as tumor history and treatment status, and further controlling for this confounding factor through propensity score matching to more accurately quantify the independent effect of olanzapine on thrombosis risk.

This study found that the use of olanzapine significantly increased the risk of PE and VTE; however, it did not explore the underlying mechanisms by which olanzapine induces thrombosis. To address this gap, we conducted a literature review to explore the potential mechanisms through which olanzapine may contribute to the development of PE or VTE. First, olanzapine increases the risk of thrombosis mainly by inducing metabolic syndrome (45). Metabolic syndrome is characterized by obesity, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance (IR), and abnormal blood glucose metabolism. This not only increases the risk of patients developing type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease (46), but also accelerates atherosclerosis. Dyslipidemia promotes lipid deposition in the vascular endothelium, leading to inflammation and plaque formation. In rabbit coronary arteries with atherosclerosis, the vasoconstrictive response to serotonin was significantly enhanced. This hyperconstriction was mainly mediated by 5-HT1B receptors and led to enhanced intracellular calcium mobilization in smooth muscle cells through pertussis toxin-sensitive signaling pathways. In diseased vessels, the mRNA level of 5-HT1B receptors was also significantly upregulated. This excessive vasoconstriction may restrict blood flow, induce angina, and exacerbate vascular occlusion when plaques rupture.Atherosclerotic plaques disrupt endothelial integrity, expose subendothelial collagen, and activate platelet adhesion and aggregation—a key step in arterial thrombosis (47). Furthermore, in order to determine the drug-induced nature of olanzapine itself and exclude the influence of patients with metabolic syndrome, we consulted the Faers database and found that there were only 193 cases (0.3%) of metabolic syndrome patients in the original database. This indicates that the proportion of recorded cases of metabolic syndrome is extremely low, suggesting that this factor is not the main driving factor of the observed thrombotic signals. In addition, metabolic abnormalities caused by olanzapine can also lead to impaired endothelial function and increase the risk of thrombosis (48). Vascular endothelial injury is another key mechanism underlying thrombosis. Studies have shown that olanzapine can induce oxidative stress and inflammatory responses, resulting in endothelial cell damage and dysfunction (49). Olanzapine promotes the inflammatory response in atherosclerosis by disrupting aortic cholesterol homeostasis and the regulation of hepatic lipid metabolism, leading to endothelial dysfunction (50). Moreover, olanzapine-induced oxidative stress increases the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reduces nitric oxide (NO) synthesis, causing vasoconstriction and promoting thrombosis (51). Oxidative stress and inflammation can also dysregulate the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) signaling pathway, leading to increased vascular permeability, endothelial apoptosis, and abnormal angiogenesis (52). Furthermore, recent studies have shown that olanzapine can induce various stress responses in pancreatic β-cell vesicles, thereby impairing insulin secretion. In pancreatic β-cell lines, olanzapine can reduce insulin secretion at clinically relevant concentrations (64–160 nM). Studies have shown that β-cells express multiple dopamine, serotonin, and histamine receptors. Olanzapine may directly inhibit insulin secretion by inhibiting dopamine D3 receptors, serotonin 5-HT2B and 5-HT2C receptors, and histamine H1 receptors. Insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia can lead to endothelial dysfunction, a pro-inflammatory state, and inhibition of the fibrinolytic system (e.g., elevated plasminogen activator inhibitor-1), thereby creating a vascular environment conducive to thrombosis (53). Finally, subgroup analysis in the current study revealed that patients with a follow-up period longer than one year had a slightly lower risk of thrombosis [OR = 1.73, 95% CI (1.23, 2.44), P = 0.31], suggesting that metabolic adaptation or clinical monitoring may partially mitigate the long-term thrombotic risk associated with olanzapine use. However, further investigation is needed to confirm this hypothesis.

Among the second-generation antipsychotics, both olanzapine and clozapine are associated with an increased risk of thrombosis, but the mechanisms and magnitude of risk may differ between the two. Clozapine increases the risk of thrombosis by directly affecting the coagulation system (54), and users of clozapine have a higher risk of venous thromboembolism and pulmonary embolism than users of olanzapine (18). However, compared with other antipsychotics, olanzapine has more significant metabolic side effects (55). A retrospective cohort study of nursing home residents showed that the adjusted hazard ratio (HR) for hospitalization due to VTE in patients using risperidone was 1.98 (95% CI, 1.40–2.78) (15). This indicates a risk level similar to olanzapine. There are also case reports of the same patient experiencing pulmonary embolism after consecutive use of olanzapine and risperidone, suggesting that these two drugs with similar 5-HT2 receptor antagonistic properties may both be associated with this adverse reaction (56).In addition, one study detected an association signal between quetiapine and VTE (ROR = 1.37), suggesting that the risk of quetiapine may be relatively low, but not entirely risk-free, and may vary across different populations (40). Most evidence tends to suggest that aripiprazole carries a lower risk, with some studies suggesting a lower likelihood of pulmonary embolism in patients taking aripiprazole (57).

Studies have also shown that other antipsychotic drugs (APS) may induce thrombosis, with platelet activation playing a more prominent role in the underlying mechanism. Dai et al. reported that the use of APS was associated with the risk of VTE and PE (58). First, antipsychotics can enhance platelet aggregation, which is one of the key factors leading to thrombosis (59). At the same time, antipsychotic drugs are also associated with increased platelet activation markers, further increasing the risk of thrombosis (60). Secondly, 5-HT is an important mediator of platelet activation and aggregation. Antipsychotic drugs regulate the 5-HT system to affect platelet function, indirectly affecting platelet activation and aggregation (61). In addition, the metabolites of antipsychotic drugs may also indirectly affect platelet function by inhibiting platelet aggregation-related enzymes (cyclooxygenase) or changing the fluidity of platelet membranes (62). Moreover, long-term use of antipsychotic drugs may lead to drug accumulation, further exacerbating the effects on platelet function (62).

In addition, according to the FAERS database, olanzapine may also cause other unrecorded adverse reactions. Febrile neutropenia: Immune-mediated neutrophil damage and cytokine dysregulation lead to fever (63–65). Hyponatremia: Central dopamine D2 and 5-HT2Areceptors antagonism interferes with the regulation of antidiuretic hormone (ADH) secretion and drug-induced polydipsia, leading to hyponatremia (66–69). Myocarditis: Olanzapine antagonizes 5-HT2A receptors, histamine H1 receptors, and muscarinic M3 receptors. It can reduce coronary blood flow, inhibit cardiac ATP production, and change the phosphorylation level of acetyl-CoA carboxylase, directly affecting myocardial energy metabolism. The pro-inflammatory response caused by olanzapine may be involved in the occurrence of myocarditis (70–74). Infectious aspiration pneumonia: The significant anticholinergic and sedative effects of high-dose olanzapine inhibit the swallowing reflex and throat coordination, increasing the risk of aspiration and aspiration pneumonia. Chronic inflammation associated with metabolic syndrome may also weaken lung defenses (74–79). Therefore, potential adverse events such as cardiovascular, blood, and respiratory system events need to be monitored during clinical use of olanzapine to guide safer and more individualized drug use strategies.

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the FAERS database is based on spontaneous reporting, which may lead to under-reporting, duplicate submissions, and potential inaccuracies in the data, thereby introducing reporting bias into the analysis (80). Second, since the core data of the FAERS database are predominantly derived from the healthcare system in the United States, the generalizability of the findings to other countries or regions with differing healthcare policies, population characteristics, or clinical practices may be limited, and thus their applicability should be carefully evaluated in light of regional differences. Third, the detection of ADE signals indicates only a statistical association, and further clinical investigations are required to establish a causal relationship supported by biological mechanisms. Despite these limitations, this study provides valuable insights into pharmacovigilance signal detection and highlights the importance of enhanced post-marketing surveillance. Moreover, the meta-analysis exhibited substantial heterogeneity, primarily attributable to variations in study design, exposure definitions, and population characteristics. The number of eligible studies included was relatively limited, especially for pulmonary embolism, indicating a need for future large-scale, high-quality research to further validate these findings. In particular, more robust cohort and case-control studies focusing on pulmonary embolism are needed to strengthen the evidence base. Additionally, observational studies such as retrospective cohorts and case-control designs are inherently susceptible to residual confounding from variables including concomitant medications, lifestyle factors, age, sex, environmental exposures, dietary habits, and daily routines. Although most of the included studies attempted to control for such confounders, the possibility of residual bias cannot be completely excluded. Furthermore, the relationship between olanzapine dosage and thrombotic risk was not comprehensively examined in the included studies, limiting the clinical interpretability and guidance regarding dose-related risk.

Based on the existing evidence, clinicians need to be alert to the risk of thrombosis during olanzapine treatment, especially for high-risk groups such as elderly patients, obese patients or those with venous congestion. It is recommended to assess the patient's baseline thrombotic risk before medication, strengthen monitoring during treatment, and consider preventive measures. For patients taking long-term medication, metabolic indicators need to be assessed regularly to intervene in related side effects at an early stage. Future research can conduct prospective cohort studies to control confounding factors and clarify the dose-effect relationship. Explore the role of biomarkers (e.g., inflammatory factors, coagulation markers) in risk prediction. To evaluate the effectiveness of prophylactic interventions (such as risk-assessed anticoagulation therapy) in reducing thrombotic events in certain high-risk olanzapine users.

5 Conclusion

Based on the results of signal detection from the FAERS database, as well as findings from a systematic review and meta-analysis, this study confirmed that olanzapine is significantly associated with an increased risk of PE and VTE. The systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrated that, compared with non-users, olanzapine users had a significantly elevated combined risk ratio for PE and VTE (OR 2.07, 95% CI 1.37–3.14; P = 0.0006). The underlying mechanisms by which olanzapine may induce thrombotic events could involve metabolic disturbances, enhanced platelet aggregation, and impaired venous return. This risk is more pronounced in high-risk groups, including core users aged 41–64 (29.2%,95% CI:28.8%–29.6% of the total reported cases), the elderly aged 65 and above (16.3%,95% CI:16.0%–16.6%), obese patients, and patients with venous stasis. Given the widespread use of olanzapine, clinicians should maintain a high level of vigilance for thromboembolic adverse events in patients receiving this medication, particularly those at elevated risk, and should consider appropriate preventive and interventional strategies.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author contributions

XZ: Methodology, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation. SS: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Validation. XF: Data curation, Software, Writing – original draft. SG: Methodology, Writing – original draft. WL: Methodology, Writing – original draft. CW: Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft. JX: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. CC: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. HJ: Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82074104, 82474169).

Conflict of interest

WL and HJ are employed by Beijing Union-Genius Pharmaceutical Technology Development Co., Ltd.,

The remaining author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcvm.2026.1710507/full#supplementary-material.

References

1.

Moura C Vale N . The role of dopamine in repurposing drugs for oncology. Biomedicines. (2023) 11(7):1917. 10.3390/biomedicines11071917

2.

McDonnell DP Landry J Detke HC . Long-term safety and efficacy of olanzapine long-acting injection in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder: a 6-year, multinational, single-arm, open-label study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. (2014) 29(6):322–31. 10.1097/YIC.0000000000000038

3.

Thomas K Saadabadi A . Olanzapine. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2025, StatPearls Publishing LLC (2025).

4.

Turetz M Sideris AT Friedman OA Triphathi N Horowitz JM . Epidemiology, pathophysiology, and natural history of pulmonary embolism. Semin Intervent Radiol. (2018) 35(2):92–8. 10.1055/s-0038-1642036

5.

Agnelli G Becattini C . Acute pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. (2010) 363(3):266–74. 10.1056/NEJMra0907731

6.

Nishiyama KH Saboo SS Tanabe Y Jasinowodolinski D Landay MJ Kay FU . Chronic pulmonary embolism: diagnosis. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. (2018) 8(3):253–71. 10.21037/cdt.2018.01.09

7.

Vyas V Sankari A Goyal A . Acute pulmonary embolism. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2025, StatPearls Publishing LLC (2025).

8.

Heit JA Spencer FA White RH . The epidemiology of venous thromboembolism. J Thromb Thrombolysis. (2016) 41(1):3–14. 10.1007/s11239-015-1311-6

9.

Masopust J Bazantova V Kuca K Klimova B Valis M . Venous thromboembolism as an adverse effect during treatment with olanzapine: a case series. Front Psychiatry. (2019) 10:330. 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00330

10.

Maempel JFZ Darmanin G Naeem K Patel M . Olanzapine and pulmonary embolism, a rare association: a case report. Cases J. (2010) 3:36. 10.1186/1757-1626-3-36

11.

Walker AM Lanza LL Arellano F Rothman KJ . Mortality in current and former users of clozapine. Epidemiology. (1997) 8(6):671–7. 10.1097/00001648-199710000-00010

12.

Vu VH Khang ND Thao MT Khoi LM . Acute pulmonary embolism associated with low-dose olanzapine in a patient without risk factors for venous thromboembolism. Case Rep Vasc Med. (2021) 2021:5138509. 10.1155/2021/5138509

13.

Waage IM Gedde-Dahl A . Pulmonary embolism possibly associated with olanzapine treatment. Br Med J. (2003) 327(7428):1384. 10.1136/bmj.327.7428.1384

14.

Kannan R Molina DK . Olanzapine: a new risk factor for pulmonary embolus?Am J Forensic Med Pathol. (2008) 29(4):368–70. 10.1097/PAF.0b013e31818736e0

15.

Liperoti R Pedone C Lapane KL Mor V Bernabei R Gambassi G . Venous thromboembolism among elderly patients treated with atypical and conventional antipsychotic agents. Arch Intern Med. (2005) 165(22):2677–82. 10.1001/archinte.165.22.2677

16.

Wang L Xu Y Jiang W Liu J Cao C Shen Y et al Is there association of olanzapine and pulmonary embolism: a case report. Clin Case Rep. (2022) 10(6):e05805. 10.1002/ccr3.5805

17.

Keles E Ulasli SS Basaran NC Babaoglu E Koksal D . Acute massive pulmonary embolism assocıated wıth olanzapıne. Am J Emerg Med. (2017) 35(10):1582.e5–.e7. 10.1016/j.ajem.2017.07.026

18.

Ogłodek EA Just MJ Grzesińska AD Araszkiewicz A Szromek AR . The impact of antipsychotics as a risk factor for thromboembolism. Pharmacol Rep. (2018) 70(3):533–9. 10.1016/j.pharep.2017.12.003

19.

Manu P Hohman C Barrecchia JF Shulman M . Chapter 3—pulmonary embolism. In: ManuPFlanaganRJRonaldsonKJ, editors. Life-Threatening Effects of Antipsychotic Drugs. San Diego: Academic Press (2016). p. 59–79. 10.1016/B978-0-12-803376-0.00003-4

20.

Li XQ Tang XR Li LL . Antipsychotics cardiotoxicity: what’s known and what’s next. World J Psychiatry. (2021) 11(10):736–53. 10.5498/wjp.v11.i10.736

21.

Mollard LM Le Mao R Tromeur C Le Moigne E Gouillou M Pan-Petesch B et al Antipsychotic drugs and the risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism: a prospective cohort study. Eur J Intern Med. (2018) 52:22–7. 10.1016/j.ejim.2018.02.030

22.

Liu Y Xu J Fang K Xu Y Gao J Zhou C et al Current antipsychotic agent use and risk of venous thromboembolism and pulmonary embolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. (2021) 11:2045125320982720. 10.1177/2045125320982720

23.

Zhou C Peng S Lin A Jiang A Peng Y Gu T et al Psychiatric disorders associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: a pharmacovigilance analysis of the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) database. EClinicalMedicine. (2023) 59:101967. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.101967

24.

Long J Yi Y Zhang Y Li X . Hypersensitivity reactions induced by iodinated contrast Media in radiological diagnosis: a disproportionality analysis based on the FAERS database. Curr Med Imaging. (2024) 20:e15734056306358. 10.2174/0115734056306358240607115422

25.

Moher D Liberati A Tetzlaff J Altman DG . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. (2009) 62(10):1006–12. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005

26.

He Y Zhang R Shen H Liu Y . A real-world disproportionality analysis of FDA adverse event reporting system (FAERS) events for denosumab. Front Pharmacol. (2024) 15:1339721. 10.3389/fphar.2024.1339721

27.

Xiong R Lei J Pan S Zhang H Tong Y Wu W et al Post-marketing safety surveillance of dalfampridine for multiple sclerosis using FDA adverse event reporting system. Front Pharmacol. (2023) 14:1226086. 10.3389/fphar.2023.1226086

28.

Rothman KJ Lanes S Sacks ST . The reporting odds ratio and its advantages over the proportional reporting ratio. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. (2004) 13(8):519–23. 10.1002/pds.1001

29.

Evans SJW Waller PC Davis S . Use of proportional reporting ratios (PRRs) for signal generation from spontaneous adverse drug reaction reports. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. (2001) 10(6):483–6. 10.1002/pds.677

30.

Ntekim A Campbell O Rothenbacher D . Optimal management of cervical cancer in HIV-positive patients: a systematic review. Cancer Med. (2015) 4(9):1381–93. 10.1002/cam4.485

31.

DerSimonian R Laird N . Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. (1986) 7(3):177–88. 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2

32.

Higgins JPT Thompson SG Deeks JJ Altman DG . Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. Br Med J. (2003) 327(7414):557–60. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557

33.

Barata PC Santos MJ Melo JC Maia T . Olanzapine-induced hyperprolactinemia: two case reports. Front Pharmacol. (2019) 10:846. 10.3389/fphar.2019.00846

34.

Wu L Fang H Qu Y Xu J Tong W . Leveraging FDA labeling documents and large language model to enhance annotation, profiling, and classification of drug adverse events with AskFDALabel. Drug Saf. (2025) 48(6):655–65. 10.1007/s40264-025-01520-1

35.

Ishiguro C Wang X Li L Jick S . Antipsychotic drugs and risk of idiopathic venous thromboembolism: a nested case-control study using the CPRD. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. (2014) 23(11):1168–75. 10.1002/pds.3699

36.

Allenet B Schmidlin S Genty C Bosson JL . Antipsychotic drugs and risk of pulmonary embolism. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. (2012) 21(1):42–8. 10.1002/pds.2210

37.

Parker C Coupland C Hippisley-Cox J . Antipsychotic drugs and risk of venous thromboembolism: nested case-control study. Br Med J. (2010) 341:c4245. 10.1136/bmj.c4245

38.

Huang J Zou F Zhu J Wu Z Lin C Wei P et al Association between antipsychotics and pulmonary embolism: a pharmacovigilance analysis. Expert Opin Drug Saf. (2024) 24(11):1259–64. 10.1080/14740338.2024.2396390

39.

Myllylahti L Niskanen L Lassila R Haukka J . A pharmacoepidemiological nested case-control study of risk factors for venous thromboembolism with the focus on diabetes, cancer, socioeconomic group, medications, and comorbidities. Diab Vasc Dis Res. (2024) 21(3):14791641241236894. 10.1177/14791641241236894

40.

Yan Y Wang L Yuan Y Xu J Chen Y Wu B . A pharmacovigilance study of the association between antipsychotic drugs and venous thromboembolism based on food and drug administration adverse event reporting system data. Expert Opin Drug Saf. (2024) 23(6):771–6. 10.1080/14740338.2023.2251881

41.

Wang MT Liou JT Huang YW Lin CW Wu GJ Chu CL et al Use of antipsychotics and risk of venous thromboembolism in postmenopausal women. A population-based nested case-control study. Thromb Haemost. (2016) 115(6):1209–19. 10.1160/TH15-11-0895

42.

Hsu WY Lane HY Lin CL Kao CH . A population-based cohort study on deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism among schizophrenia patients. Schizophr Res. (2015) 162(1-3):248–52. 10.1016/j.schres.2015.01.012

43.

Jönsson AK Schill J Olsson H Spigset O Hägg S . Venous thromboembolism during treatment with antipsychotics: a review of current evidence. CNS Drugs. (2018) 32(1):47–64. 10.1007/s40263-018-0495-7

44.

Khorana AA Francis CW Culakova E Kuderer NM Lyman GH . Thromboembolism is a leading cause of death in cancer patients receiving outpatient chemotherapy. J Thromb Haemost. (2007) 5(3):632–4. 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02374.x

45.

Moussaoui J Saadi I Barrimi M . Olanzapine-induced acute pulmonary embolism. Cureus. (2024) 16(9):e68626. 10.7759/cureus.68626

46.

Li H Peng S Li S Liu S Lv Y Yang N et al Chronic olanzapine administration causes metabolic syndrome through inflammatory cytokines in rodent models of insulin resistance. Sci Rep. (2019) 9(1):1582. 10.1038/s41598-018-36930-y

47.

Moin ASM Sathyapalan T Diboun I Elrayess MA Butler AE Atkin SL . Metabolic consequences of obesity on the hypercoagulable state of polycystic ovary syndrome. Sci Rep. (2021) 11(1):5320. 10.1038/s41598-021-84586-y

48.

Huang PP Zhu WQ Xiao JM Zhang YQ Li R Yang Y et al Alterations in sorting and secretion of hepatic apoA5 induce hypertriglyceridemia due to short-term use of olanzapine. Front Pharmacol. (2022) 13:935362. 10.3389/fphar.2022.935362

49.

Zheng C Liu H Tu W Lin L Xu H . Hypercoagulable state in patients with schizophrenia: different effects of acute and chronic antipsychotic medications. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. (2023) 13:20451253231200257. 10.1177/20451253231200257

50.

Su Y Cao C Chen S Lian J Han M Liu X et al Olanzapine modulate lipid metabolism and adipose tissue accumulation via hepatic muscarinic M3 receptor-mediated Alk-related signaling. Biomedicines. (2024) 12(7):1403. 10.3390/biomedicines12071403

51.

Rolski F Czepiel M Tkacz K Fryt K Siedlar M Kania G et al T lymphocyte-derived exosomes transport MEK1/2 and ERK1/2 and induce NOX4-dependent oxidative stress in cardiac microvascular endothelial cells. Oxid Med Cell Longev. (2022) 2022:2457687. 10.1155/2022/2457687

52.

Guo X Yi H Li TC Wang Y Wang H Chen X . Role of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in human embryo implantation: clinical implications. Biomolecules. (2021) 11(2):253. 10.3390/biom11020253

53.

Nagata M Yokooji T Nakai T Miura Y Tomita T Taogoshi T et al Blockade of multiple monoamines receptors reduce insulin secretion from pancreatic β-cells. Sci Rep. (2019) 9(1):16438. 10.1038/s41598-019-52590-y

54.

Chate S Patted S Nayak R Patil N Pandurangi A . Pulmonary thromboembolism associated with clozapine. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2013) 25(2):E3–6. 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.12080201

55.

Townsend LK Peppler WT Bush ND Wright DC . Obesity exacerbates the acute metabolic side effects of olanzapine. Psychoneuroendocrinology. (2018) 88:121–8. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.12.004

56.

Borras L Eytan A de Timary P Constant EL Huguelet P Hermans C . Pulmonary thromboembolism associated with olanzapine and risperidone. J Emerg Med. (2008) 35(2):159–61. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.07.074

57.

Skokou M Gourzis P . Pulmonary embolism related to amisulpride treatment: a case report. Case Rep Psychiatry. (2013) 2013:718950. 10.1155/2013/718950

58.

Dai L Zuo Q Chen F Chen L Shen Y . The association and influencing factors between antipsychotics exposure and the risk of VTE and PE: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Drug Targets. (2020) 21(9):930–42. 10.2174/1389450121666200422084414

59.

Dho-Nagy EA Brassai A Lechsner P Ureche C Bán EG . COVID-19 and antipsychotic therapy: unraveling the thrombosis risk. Int J Mol Sci. (2024) 25(2):818. 10.3390/ijms25020818

60.

Haegg S Spigset O . Antipsychotic-induced venous thromboembolism—a review of the evidence. CNS Drugs. (2002) 16:765–76. 10.2165/00023210-200216110-00005

61.

Rieder M Gauchel N Bode C Duerschmied D . Serotonin: a platelet hormone modulating cardiovascular disease. J Thromb Thrombolysis. (2021) 52(1):42–7. 10.1007/s11239-020-02331-0

62.

Zhang Y Zheng Y Ni P Liang S Li X Yu H et al New role of platelets in schizophrenia: predicting drug response. Gen Psychiatr. (2024) 37(2):e101347. 10.1136/gpsych-2023-101347

63.

Tolosa-Vilella C Ruiz-Ripoll A Mari-Alfonso B Naval-Sendra E . Olanzapine-induced agranulocytosis: a case report and review of the literature. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. (2002) 26(2):411–4. 10.1016/S0278-5846(01)00258-5

64.

Kluge M Schuld A Schacht A Himmerich H Dalal MA Wehmeier PM et al Effects of clozapine and olanzapine on cytokine systems are closely linked to weight gain and drug-induced fever. Psychoneuroendocrinology. (2009) 34(1):118–28. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.08.016

65.

Yoshioka Y Sugino Y Shibagaki F Yamamuro A Ishimaru Y Maeda S . Dopamine attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced expression of proinflammatory cytokines by inhibiting the nuclear translocation of NF-κB p65 through the formation of dopamine quinone in microglia. Eur J Pharmacol. (2020) 866:172826. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2019.172826

66.

Adelakun AA Choi C Brensilver J . Severe syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH) following the initiation of valbenazine for tardive dyskinesia: a case report. Cureus. (2024) 16(4):e58493. 10.7759/cureus.58493

67.

Fujimoto M Hashimoto R Yamamori H Yasuda Y Ohi K Iwatani H et al Clozapine improved the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion in a patient with treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2016) 70:469. Contract No.: 10. 10.1111/pcn.12435

68.

Anil SS Ratnakaran B Suresh N . A case report of rapid-onset hyponatremia induced by low-dose olanzapine. J Fam Med Prim Care. (2017) 6(4):878–80. 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_205_17

69.

Hurwit AA Parker JM Uhlyar S . Treatment of psychogenic polydipsia and hyponatremia: a case report. Cureus. (2023) 15(10):e47719. 10.7759/cureus.47719

70.

Vang T Rosenzweig M Bruhn CH Polcwiartek C Kanters JK Nielsen J . Eosinophilic myocarditis during treatment with olanzapine—report of two possible cases. BMC Psychiatry. (2016) 16:70. 10.1186/s12888-016-0776-y

71.