Abstract

Background:

Arteriosclerosis, a hallmark of vascular aging, can be assessed using brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity (baPWV). The fibrinogen-to-albumin ratio (FAR), a novel marker reflecting inflammation and hemodynamics, has been proposed as a potential indicator for cardiovascular disease (CVD). However, the association between FAR and baPWV has not been fully elucidated. This study seeks to investigate this association.

Methods:

A total of 389 elderly patients were enrolled. Arteriosclerosis was defined as a baPWV ≥1,800 cm/s. Participants were divided into four groups according to FAR quartiles. Multivariate logistic regression was used to assess the association between FAR quartiles and arteriosclerosis. Restricted cubic spline (RCS) analysis was additionally employed to examine the dose–response relationship between continuous FAR and arteriosclerosis risk.

Results:

The prevalence of arteriosclerosis increased significantly with increasing FAR quartiles (61.2%, 61.9%, 77.3%, 86.6%; p < 0.001). Multivariate linear regression demonstrated an independent positive correlation between FAR and baPWV (β = 13.283, 95% CI: 0.286–26.281, p = 0.046). In multivariate logistic regression, higher FAR quartiles were linked to higher odds ratios (ORs) for arteriosclerosis (Q2: OR = 0.997, 95% CI: 0.521–1.907, p = 0.992; Q3: OR = 2.094, 95% CI: 1.048–4.186, p = 0.036; Q4: OR = 2.804, 95% CI: 1.258–6.248, p = 0.012) with a significant trend (p for trend = 0.002). RCS analysis further confirmed a linear association between FAR and arteriosclerosis risk (p for non-linearity >0.05).

Conclusions:

In elderly adults, FAR is independently and positively associated with baPWV, suggesting its potential as an additional biomarker for evaluating vascular aging.

1 Introduction

The proportion of adults aged ≥65 years worldwide is projected to double from approximately 10% in 2010 to 20% by 2040 (1). With advancing age, the vasculature undergoes structural and functional degeneration, collectively termed “vascular aging,” which has become the leading contributor to disability and mortality in older adults (2). Arteriosclerosis, the hallmark structural manifestation of vascular aging, reflects intrinsic alterations in the arterial wall that increase vascular stiffness and strongly predispose individuals to cardiovascular disease (CVD) (3). In community-dwelling Chinese aged 70–79 years, the rate of prevalence of carotid atherosclerosis has been reported to reach 60%–80% (4). Although carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity (cfPWV) is widely recognized as the gold standard for assessing arterial stiffness, its measurement is time-consuming (5). In contrast, brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity (baPWV) provides a simpler and more efficient alternative (6).

The fibrinogen-to-albumin ratio (FAR) is calculated as the ratio of fibrinogen to albumin in peripheral blood. Fibrinogen and albumin are circulating proteins that exert distinct physiological functions. Fibrinogen is an indicator of a procoagulant state and a biomarker for chronic inflammation (7, 8). Elevated plasma fibrinogen levels are closely associated with an increased risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs) (9, 10). In contrast, albumin possesses anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anticoagulant properties (10–13). Hypoalbuminemia is associated with an elevated risk of MACEs (14, 15). Recent studies have demonstrated that the FAR, a readily available and cost-effective marker, may predict MACEs more accurately than fibrinogen or albumin alone (16, 17). However, the association between FAR and arteriosclerosis has not yet been clearly elucidated.

The present study was designed to investigate the association between FAR and baPWV and to clarify the role of the FAR in evaluating cardiovascular aging.

2 Methods

2.1 Study patients

This retrospective study was conducted at Fujian Provincial Hospital between 1 January 2018 and 30 June 2019 and included elderly Chinese inpatients admitted during this period. For inclusion in the study, patients had to meet two criteria, the first being aged 65 years or older and the second being having valid brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity (baPWV) measurements obtained using an arteriosclerosis detector. Patients were excluded if they had acute infections, malignancies, acute myocardial infarction, atrial fibrillation, valvular heart disease, myocarditis, aortopathies, acute cerebral infarction, if their ankle-brachial index (ABI) was less than 0.9, if they had used anticoagulants or antiplatelet agents within the previous week, or if they had received a recent blood transfusion. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Fujian Provincial Hospital (approval number K2020-12-024). Given that this was a retrospective study, informed consent was waived. A total of 389 eligible participants were ultimately enrolled. Data on participants' medical history [hypertension (HTN), diabetes mellitus (DM)], current medications, smoking status, and other relevant clinical variables were extracted from the hospital's electronic medical records system.

2.2 Cardiovascular risk factors

HTN was defined as self-reported hypertension, a blood pressure of ≥140/90 mmHg, or a history of antihypertensive medication use. DM was defined as self-reported diabetes or the use of hypoglycemic agents. Dyslipidemia was defined as triglyceride (TG) ≥1.7 mmol/L, total cholesterol (TC) ≥5.2 mmol/L, low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C) ≥3.3 mmol/L, high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (HDL-C) <1.0 mmol/L, or the use of antidyslipidemic medications. High body mass index (BMI) was defined as BMI ≥24.0 kg/m2. Smoking status was categorized as non-smokers (never smoked) and smokers (former or current smokers).

2.3 Physical examination

Clinical assessments encompassed measurements of height, weight, systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), and heart rate (HR). BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared (kg/m2). Mean arterial blood pressure (MABP) was calculated using the following formula: MABP (mmHg) = (1/3 × SBP) + (2/3 × DBP).

2.4 Biochemical assessment

Blood samples were collected following an 8-h fasting period. The biochemical parameters assessed on admission were platelet count (PLT), albumin (ALB), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), fasting blood glucose (FBG), total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C), creatinine, uric acid (UA), and fibrinogen. The FAR was calculated as (fibrinogen/albumin) × 100. The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the CKD-EPI formula, with separate calculations for males and females (18).

2.5 Brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity

After 10 min of supine rest, baPWV was measured using a fully automatic arteriosclerosis detector (Colin VP1000; Colin Medical Technology, Komaki, Japan). Bilateral baPWV measurements were acquired, and the higher of the two values was used for analysis. Arterial stiffness was classified into three categories: normal (baPWV <1,400 cm/s), borderline (1,400 ≤ baPWV <1,800 cm/s), and arteriosclerosis (baPWV ≥1,800 cm/s, indicating elevated stiffness) (19).

2.6 Statistical analysis

Cardiovascular risk factors, current treatments, and other clinical characteristics were compared between patients with and without arteriosclerosis and across FAR quartile groups. Pearson linear correlation analysis was used to explore potential correlations between FAR and baPWV. Multiple linear regression analysis was performed to quantify the independent association between FAR (continuous variable) and baPWV (continuous outcome). Three adjusted models were constructed sequentially: Model 1 adjusted for gender, age, smoking status, diabetes, hypertension, high BMI, and dyslipidemia; Model 2 further adjusted for current medications (hypoglycemic, antihypertensive, and antidyslipidemic agents); Model 3 additionally adjusted for laboratory covariates (PLT, ALT, eGFR, and UA). The regression coefficient (β) with 95% confidence interval (CI) was reported to reflect the average change in baPWV per unit increase in FAR. Similarly, using the same adjusted models described above, logistic regression analysis was used to evaluate the relationship between FAR and arteriosclerosis. The FAR was treated as either a quartile categorical variable or a continuous variable, while arteriosclerosis was defined as the dichotomous outcome. Restricted cubic spline (RCS) analysis was performed to further characterize the dose–response relationship between FAR and the risk of arteriosclerosis. Three knots (10th, 50th, and 90th percentiles of FAR) were used to balance model complexity and ease of interpretation. Subgroup analyses were performed according to gender (female/male), smoking status (non-smoker/smoker), diabetes (no/yes), hypertension (no/yes), dyslipidemia (no/yes), and high BMI (no/yes). Interaction was tested by adding FAR-by-subgroup product terms to the regression models. All statistical tests were two-sided, and a p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 25.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The RCS analysis was performed using R software version 4.4.0.

3 Results

3.1 Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics of the 389 enrolled patients, stratified by the presence or absence of arteriosclerosis, are summarized in Supplementary Table S1. The cohort had a mean age of 76.5 ± 7.4 years, with 247 (63.5%) males and 101 (26.0%) being smokers. In addition, 167 (42.9%) patients had type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM), 308 (79.2%) had HTN, 261 (67.1%) had dyslipidemia, and 186 (47.8%) had high BMI. The mean FAR was 9.6% ± 4.0%, and the mean baPWV was 2,117.3 ± 531.6 cm/s. Overall, 279 patients (71.7%) had arteriosclerosis. Patients with arteriosclerosis were older and had a higher prevalence of DM and HTN.

Characteristics stratified by FAR quartiles are presented in Table 1. The mean FAR values for each quartile were Q1 (lowest): 6.2% ± 0.8%, Q2: 7.8% ± 0.4%, Q3: 9.5% ± 0.6%, and Q4 (highest): 14.8% ± 4.5%. Fibrinogen levels increased significantly with increasing FAR (p < 0.001), while albumin levels decreased significantly (p < 0.001). Significant interquartile differences were noted for HDL-C, PLT, UA, and the prevalence of high BMI. No significant differences were observed with regard to age, gender, smoking status, current medication use, ALT, FBG, LDL-C, TG, TC, or the prevalence of DM, HTN, and dyslipidemia.

Table 1

| Characteristics | Quartile of FAR | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 (n = 98) | Q2 (n = 97) | Q3 (n = 97) | Q4 (n = 97) | ||

| Cardiovascular risk factor | |||||

| Age (year) | 76.3 ± 6.7 | 75.8 ± 8.2 | 76.9 ± 7.8 | 76.9 ± 6.8 | 0.675 |

| Male (n, %) | 71 (72.4) | 56 (57.7) | 57 (58.8) | 63 (64.9) | 0.121 |

| Smokers (n, %) | 24 (24.5) | 22 (22.7) | 28 (28.9) | 27 (27.8) | 0.739 |

| Diabetes (n, %) | 42 (42.9) | 36 (37.1) | 43 (44.3) | 46 (47.4) | 0.529 |

| Hypertension (n, %) | 78 (79.6) | 77 (79.4) | 77 (79.4) | 76 (78.4) | 0.997 |

| Dyslipidemia (n, %) | 57 (58.2) | 65 (67.0) | 69 (71.1) | 70 (72.2) | 0.146 |

| High BMI (n, %) | 59 (60.2) | 46 (47.4) | 41 (42.3) | 40 (41.2) | 0.030 |

| Current treatments (n, %) | |||||

| Hypoglycemic agents | 28 (28.6) | 25 (25.8) | 34 (35.1) | 35 (36.1) | 0.337 |

| Antihypertensive agents | 62 (63.3) | 53 (54.6) | 60 (61.9) | 47 (48.5) | 0.132 |

| Antidyslipidemic agents | 19 (19.4) | 11 (11.3) | 20 (20.6) | 13 (13.4) | 0.224 |

| Physical exam | |||||

| SBP (mmHg) | 142.7 ± 18.8 | 141.5 ± 21.4 | 143.8 ± 21.2 | 141.3 ± 22.7 | 0.828 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 77.9 ± 10.8 | 77.8 ± 11.8 | 76.2 ± 11.7 | 74.9 ± 11.2 | 0.200 |

| MABP (mmHg) | 99.5 ± 11.7 | 99.0 ± 12.9 | 98.7 ± 12.8 | 97.0 ± 13.4 | 0.542 |

| HR (bpm) | 75.1 ± 10.2 | 78.6 ± 12.3 | 75.4 ± 12.0 | 77.9 ± 10.3 | 0.064 |

| Laboratory Data | |||||

| PLT (109/L) | 201.5 ± 80.1 | 223.1 ± 57.4 | 219.5 ± 56.9 | 273.5 ± 104.4 | <0.001 |

| ALT (U/L) | 21.5 ± 10.8 | 20.3 ± 11.9 | 21.0 ± 12.9 | 18.0 ± 11.7 | 0.182 |

| AST (U/L) | 22.5 ± 11.4 | 19.8 ± 6.7 | 21.2 ± 7.9 | 19.6 ± 10.5 | 0.105 |

| FBG (mmol/L) | 6.3 ± 2.0 | 7.1 ± 4.8 | 6.6 ± 2.6 | 7.4 ± 3.9 | 0.128 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.5 ± 0.8 | 1.4 ± 0.8 | 1.5 ± 0.8 | 1.3 ± 0.9 | 0.487 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 4.4 ± 1.3 | 4.5 ± 1.1 | 4.5 ± 1.1 | 4.3 ± 1.3 | 0.631 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | <0.001 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 2.8 ± 1.1 | 2.9 ± 1.0 | 3.0 ± 1.0 | 2.9 ± 1.2 | 0.706 |

| UA (μmol/L) | 358.0 ± 102.6 | 338.4 ± 91.8 | 351.7 ± 85.7 | 316.0 ± 107.1 | 0.015 |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 56.8 ± 15.3 | 58.7 ± 19.5 | 54.8 ± 17.6 | 53.3 ± 21.5 | 0.196 |

| Fibrinogen (g/L) | 2.7 ± 0.4 | 3.3 ± 0.3 | 3.9 ± 0.4 | 5.4 ± 1.3 | <0.001 |

| ALB (g/L) | 43.6 ± 3.6 | 42.2 ± 3.8 | 40.9 ± 3.1 | 36.9 ± 4.2 | <0.001 |

| baPWV (cm/s) | 1,939.6 ± 416.0 | 2,083.9 ± 598.8 | 2,173.0 ± 530.2 | 2,274.3 ± 516.1 | <0.001 |

| Arteriosclerosis (n, %) | 60 (61.2) | 60 (61.9) | 75 (77.3) | 84 (86.6) | <0.001 |

Characteristics of patients stratified by quartiles of FAR.

BMI, body mass index; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; MABP, mean arterial blood pressure; HR, heart rate; PLT, platelet count; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; FBG, fasting blood glucose; TG, triglyceride; TC, total cholesterol; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; UA, uric acid; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; ALB, albumin; FAR, fibrinogen to albumin ratio; baPWV, brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity.

3.2 Association between FAR and baPWV

BaPWV differed significantly across FAR quartiles, with values increasing progressively with higher FAR levels (p < 0.001) (Table 1). The prevalence rate of arteriosclerosis also increased gradually from the lowest to the highest FAR quartiles (61.2%, 61.9%, 77.3%, and 86.6%, p < 0.001), with a sharp increase observed between Q2 and Q3 (Table 1).

The Pearson linear correlation analysis showed a positive correlation between FAR and baPWV (r = 0.219, p < 0.001) (Supplementary Table S2). In linear regression analyses, FAR was positively associated with baPWV (Table 2). In the unadjusted model, FAR was significantly associated with higher baPWV (β = 29.189, 95% CI: 16.223–42.156, p < 0.001). After adjustment for traditional cardiovascular risk factors (Model 1), the association remained significant (β = 23.316, 95% CI: 11.156–35.476, p < 0.001). Further adjustment for current medications (Model 2) did not materially change the estimate (β = 21.603, 95% CI: 9.293–33.914, p < 0.001). After additional adjustment for laboratory covariates (PLT, ALT, eGFR, and UA) in Model 3, the association remained statistically significant (β = 13.283, 95% CI: 0.286–26.281, p = 0.046).

Table 2

| Model | β (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | 29.189 (16.223–42.156) | <0.001 |

| Model 1 | 23.316 (11.156–35.476) | <0.001 |

| Model 2 | 21.603 (9.293–33.914) | <0.001 |

| Model 3 | 13.283 (0.286–26.281) | 0.046 |

Linear regression of FAR and baPWV.

FAR, fibrinogen to albumin ratio; baPWV, brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity; PLT, platelet count; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; UA, uric acid; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Model 1: Adjusted for gender, age, smoking status, diabetes, hypertension, high BMI, and dyslipidemia.

Model 2: Adjusted for gender, age, smoking status, diabetes, hypertension, high BMI, dyslipidemia, hypoglycemic agents, antihypertensive agents, and antidyslipidemic agents.

Model 3: Adjusted for gender, age, smoking status, hypertension, diabetes, high BMI, dyslipidemia, hypoglycemic agents, antihypertensive agents, antidyslipidemic agents, PLT, ALT, eGFR, and UA.

The logistic regression analysis was performed to investigate the relationship between FAR and arteriosclerosis (Table 3). In the unadjusted model, compared with the lowest FAR quartile (Q1), the odds of arteriosclerosis increased across higher quartiles (Q2: OR = 1.027 95% CI: 0.577–1.829, p = 0.928; Q3: OR = 2.159, 95% CI: 1.155–4.035, p = 0.016; Q4: OR = 4.092, 95% CI: 2.009–8.337, p < 0.001; p for trend <0.001). When the FAR was modeled as a continuous variable, each 1% increase in the FAR was associated with higher odds of arteriosclerosis (OR = 1.185, 95% CI: 1.088–1.291, p < 0.001). These associations remained after multivariable adjustment. In the fully adjusted Model 3, the association persisted (continuous FAR: OR = 1.140, 95% CI 1.037–1.253, p = 0.007), and higher FAR quartiles were associated with greater odds of arteriosclerosis (Q2: OR = 0.997, 95% CI: 0.521–1.907; p = 0.992; Q3: OR = 2.094, 95% CI: 1.048–4.186; p = 0.036; Q4: OR = 2.804, 95% CI: 1.258–6.248, p = 0.012; p for trend = 0.002).

Table 3

| FAR | Unadjusted | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p-Value | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| Q1 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | ||||

| Q2 | 1.027 (0.577–1.829) | 0.928 | 1.097 (0.590–2.042) | 0.770 | 1.050 (0.562–1.963) | 0.878 | 0.997 (0.521–1.907) | 0.992 |

| Q3 | 2.159 (1.155–4.035) | 0.016 | 2.015 (1.089–4.227) | 0.027 | 2.211 (1.112–4.395) | 0.024 | 2.094 (1.048–4.186) | 0.036 |

| Q4 | 4.092 (2.009–8.337) | <0.001 | 4.148 (1.951–8.819) | <0.001 | 4.063 (1.896–8.704) | <0.001 | 2.804 (1.258–6.248) | 0.012 |

| p for trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.002 | ||||

| FAR (per 1%) | 1.185 (1.088–1.291) | <0.001 | 1.182 (1.081–1.293) | <0.001 | 1.182 (1.078–1.295) | <0.001 | 1.140 (1.037–1.253) | 0.007 |

Logistic regression of FAR (quartile/continuous) and arteriosclerosis.

FAR, fibrinogen to albumin ratio; PLT, platelet count; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; UA, uric acid; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Model 1: Adjusted for gender, age, smoking status, diabetes, hypertension, high BMI, and dyslipidemia.

Model 2: Adjusted for gender, age, smoking status, diabetes, hypertension, high BMI, dyslipidemia, hypoglycemic agents, antihypertensive agents, and antidyslipidemic agents.

Model 3: Adjusted for gender, age, smoking status, hypertension, diabetes, high BMI, dyslipidemia, hypoglycemic agents, antihypertensive agents, antidyslipidemic agents, PLT, ALT, eGFR, and UA.

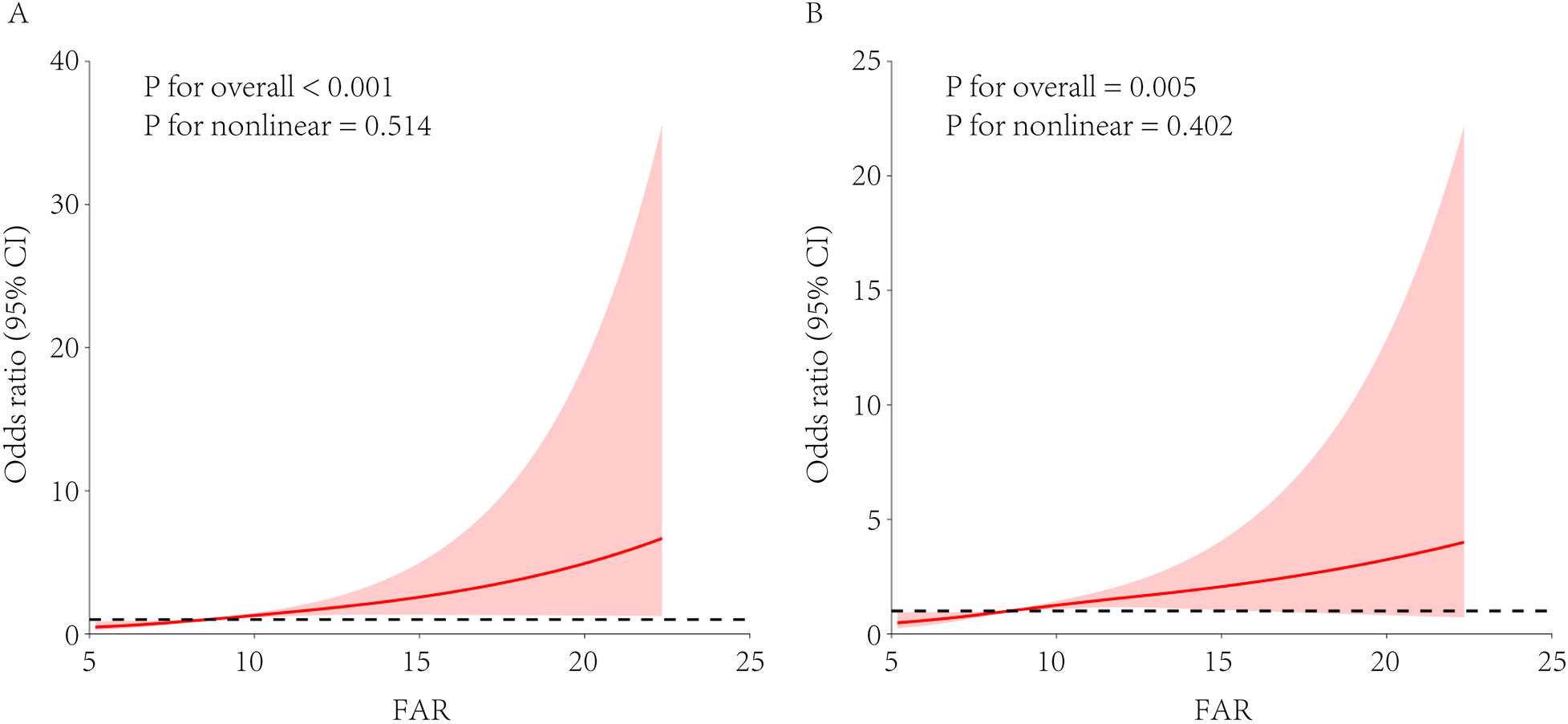

A univariate RCS analysis showed a strong overall association between FAR and arteriosclerosis risk (overall p < 0.001), with a predominantly linear trend (p for non-linearity = 0.514; Figure 1A). After adjusting for covariates as defined in Model 3, a multivariate RCS analysis confirmed that the independent association between FAR and arteriosclerosis remained significant (overall p = 0.005) and the linear trend persisted (p for non-linearity = 0.402; Figure 1B).

Figure 1

RCS analysis of the association between FAR and arteriosclerosis risk. FAR, fibrinogen-to-albumin ratio; RCS, restricted cubic spline; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate. The restricted cubic spline model used knots at the 10th, 50th, and 90th percentiles. (A) Univariate model without adjusting for covariates. (B) Multivariate model adjusted for hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, sex, age, and estimated eGFR.

An interaction analysis (Table 4) revealed no significant interactions between FAR and gender, smoking status, DM, HTN, dyslipidemia, or high BMI in relation to arteriosclerosis (all interaction p > 0.05).

Table 4

| Variables | Quartile of FAR | p for trend | p for interaction | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | ||||||

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | |||

| Gender | |||||||||

| Female | 1 (ref) | 1.221 (0.345–4.325) | 0.757 | 1.469 (0.394–5.481) | 0.567 | 3.006 (0.655–13.803) | 0.157 | 0.018 | 0.676 |

| Male | 1 (ref) | 0.821 (0.366–1.840) | 0.632 | 2.591 (1.054–6.369) | 0.038 | 3.397 (1.256–9.188) | 0.016 | 0.035 | |

| Smoking status | |||||||||

| Non-smoker | 1 (ref) | 1.135 (0.531–2.427) | 0.744 | 1.847 (0.803–4.250) | 0.149 | 2.699 (1.051–6.929) | 0.039 | 0.020 | 0.614 |

| Smoker | 1 (ref) | 0.967 (0.216–4.329) | 0.965 | 4.349 (0.902–20.965) | 0.067 | 4.903 (0.822–29.244) | 0.081 | 0.024 | |

| Diabetes | |||||||||

| No | 1 (ref) | 1.011 (0.391–2.615) | 0.982 | 2.079 (0.775–5.577) | 0.146 | 2.678 (0.899–7.980) | 0.077 | 0.033 | 0.676 |

| Yes | 1 (ref) | 0.783 (0.275–2.231) | 0.647 | 2.118 (0.693–6.474) | 0.188 | 3.335 (0.854–13.017) | 0.083 | 0.036 | |

| Hypertension | |||||||||

| No | 1 (ref) | 1.712 (0.363–8.078) | 0.497 | 3.038 (0.633–14.582) | 0.165 | 7.809 (1.294–47.112) | 0.025 | 0.018 | 0.815 |

| Yes | 1 (ref) | 0.784 (0.370–1.660) | 0.525 | 1.875 (0.815–4.312) | 0.139 | 2.351 (0.917–6.025) | 0.075 | 0.023 | |

| Dyslipidemia | |||||||||

| No | 1 (ref) | 0.342 (0.101–1.155) | 0.084 | 1.284 (0.332–4.961) | 0.717 | 5.675 (0.923–34.893) | 0.061 | 0.055 | 0.818 |

| Yes | 1 (ref) | 1.597 (0.684–3.727) | 0.279 | 2.755 (1.136–6.683) | 0.025 | 2.465 (0.913–6.655) | 0.075 | 0.025 | |

| High BMI | |||||||||

| No | 1 (ref) | 1.081 (0.403–2.899) | 0.877 | 3.464 (1.152–10.418) | 0.027 | 3.857 (1.100–13.528) | 0.035 | 0.006 | 0.326 |

| Yes | 1 (ref) | 1.120 (0.424–2.957) | 0.819 | 1.493 (0.539–4.138) | 0.441 | 2.691 (0.882–8.211) | 0.082 | 0.077 | |

Stratified interaction of FAR and arteriosclerosis.

BMI, body mass index. Adjusted for gender, age, smoking status, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, high BMI, hypoglycemic agents, antihypertensive agents, antidyslipidemic agents, PLT, ALT, eGFR, and UA.

4 Discussion

This study aimed to explore the association between FAR and arterial stiffness. BaPWV is a validated and convenient clinical indicator for assessing arterial stiffness. FAR was independently associated with both baPWV and arteriosclerosis, and these associations remained statistically significant after adjusting for potential confounding factors. A linear dose–response relationship between FAR and arteriosclerosis was further confirmed. A significant difference in the FAR was observed between participants with and without arteriosclerosis. The arteriosclerosis group exhibited a higher mean FAR compared with the non-arteriosclerosis group (10.1 ± 4.3% vs. 8.3 ± 2.8%). Participants with arteriosclerosis were older and more likely to have comorbid cardiovascular risk factors such as diabetes and hypertension. This finding aligns with established clinical patterns, as arterial stiffness increases with age and is often accompanied by metabolic risk factors.

Atherosclerosis is characterized by arterial lumen narrowing and the formation, erosion, and rupture of atherosclerotic plaques (20). These pathological processes directly induce ischemia or thrombosis, thereby contributing to CVD, including peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, and coronary heart disease. In severe cases, inadequate collateral circulation may lead to myocardial infarction or cerebral infarction. As a chronic, highly deleterious vascular disorder, atherosclerosis has shown an increasing incidence. Identifying individuals at risk of cardiovascular events remains a key focus of preventive strategies, emphasizing the critical role of early detection and intervention in mitigating disease progression at its initial stages. Arteriosclerosis, characterized by increased arterial stiffness, represents an early marker of atherosclerosis (21). BaPWV is validated and convenient for assessing arterial stiffness, but it is not routinely available in many hospitals and primary-care settings, highlighting the need for a simpler alternative.

Existing evidence supports the relevance of FAR to cardiovascular pathophysiology. For instance, Ozdemir et al. identified FAR as a predictor of exaggerated morning blood pressure surges, a well-recognized CVD risk factor (22). FAR has also been independently associated with coronary artery disease (CAD) severity in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (23). Similar associations have been reported in patients with non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (24, 25). Moreover, FAR robustly predicts MACEs in CAD patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (26). Zheng et al. linked FAR to adverse outcomes after lacunar stroke (27). Collectively, these studies position FAR as a risk factor for adverse cardiovascular events.

Notably, the association between FAR and baPWV remains insufficiently explored. In the present study, when FAR and baPWV were analyzed as continuous variables in univariable analyses, FAR was positively correlated with baPWV. Furthermore, when arteriosclerosis was defined as baPWV ≥1,800 cm/s, the prevalence of arteriosclerosis increased progressively across ascending FAR quartiles. These findings indicate that elevated FAR is independently associated with greater baPWV.

The potential mechanisms underlying the association between FAR and arteriosclerosis require further exploration. Arteriosclerosis, an early hallmark of vascular aging, is characterized by reduced vascular wall elasticity and increased stiffness (2). A growing body of evidence supports the concept of “inflammaging,” which links chronic, low-grade inflammation to progressive arterial stiffening (28). Aminuddin et al. reported an association between inflammation and elevated PWV (29). In addition, abnormal hemodynamic changes, including increased blood viscosity and coagulation activation, contribute to arteriosclerotic progression (30). FAR, influenced by both fibrinogen and albumin, may be involved in the interplay of these processes (inflammatory and hemodynamic pathways) that are associated with arteriosclerosis, although the direction of this relationship remains unclear. Fibrinogen, a key inflammatory marker, enhances inflammatory cell adhesion and upregulates proinflammatory cytokine synthesis (31). Elevated fibrinogen levels may increase blood viscosity, potentially inducing shear stress–mediated endothelial damage and coagulation activation (32). Conversely, lower albumin levels correlate with heightened inflammation (11). Inflammation increases vascular permeability and disrupts fluid homeostasis, leading to rapid changes in plasma albumin concentrations (32, 33). Observational data further show an inverse correlation between plasma albumin and C-reactive protein (CRP), a classic inflammatory marker (34). Beyond its role in inflammation, albumin exerts antioxidant effects by scavenging reactive oxygen species (ROS) and limiting oxidative stress (12, 35). Albumin also has anticoagulant properties that help maintain hemostatic balance. Therefore, hypoalbuminemia is associated with a prothrombotic state (36–38). Fibrinogen and albumin may jointly promote systemic inflammation and hemodynamic disturbances, and their alterations may together contribute to the pathophysiological processes underlying arteriosclerosis. As an integrated index, FAR captures the concurrent pattern of elevated fibrinogen and reduced albumin and may therefore be more sensitive than either marker alone in reflecting inflammatory activity and hemodynamic perturbations. In the present study, a higher FAR was associated with an increased risk of arteriosclerosis, suggesting that chronic inflammation and hemodynamic dysregulation may represent key potential pathways linking FAR to arterial stiffening.

Interaction analyses showed that the association between FAR and arteriosclerosis was not significantly modified by gender, smoking status, diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, or high BMI, suggesting that the predictive value of FAR may be broadly applicable in older adults. Even among elderly individuals without overt traditional cardiovascular risk factors, an elevated FAR remained associated with a higher risk of arteriosclerosis, indicating that FAR may serve as a potential early warning marker of vascular aging.

Several limitations in this study should be noted. First, the retrospective cross-sectional design precludes causal inference between FAR and baPWV. Arterial stiffness itself may induce chronic inflammation or disrupt hemodynamic homeostasis, thereby increasing FAR, and reverse causation cannot be excluded. Prospective cohort studies or interventional trials are needed to determine directionality. Second, the generalizability of our findings is limited. The study included older adults aged 65 years or older, and the distribution of FAR and its association with baPWV may differ in adults younger than 65 years who typically have better vascular elasticity and lower baseline inflammation. In addition, only older Chinese participants were included, and differences in genetic background, lifestyle, and disease spectrum may limit extrapolation to other age groups and ethnic populations. Third, the sample size of 389 was adequate for primary correlation and regression analyses, but statistical power for subgroup analyses was limited. Fourth, residual confounding remains possible in this single-center retrospective study. Although we adjusted for routine covariates, we did not account for chronic inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus, liver dysfunction, nutritional indicators such as prealbumin and dietary protein intake, inflammatory markers including CRP and IL-6, or relevant medication history, all of which may affect the precision of association estimates. Overall, large-scale, multicenter, multiethnic prospective studies are warranted to further validate the clinical value of FAR as a marker of vascular aging.

5 Conclusions

This study provides evidence in older adults that FAR is independently and linearly associated with arterial stiffness, offering a simple and readily available indicator for vascular aging assessment.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Committee of Fujian Provincial Hospital (approval number K2020-12-024). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The ethics committee/institutional review board waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation from the participants or the participants' legal guardians/next of kin because this was a retrospective study.

Author contributions

YZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. NL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. YL: Investigation, Writing – original draft. JK: Investigation, Writing – original draft. EH: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. SC: Data curation, Writing – original draft. HC: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 82371593). Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province, China (Grant No. 2022J011014). Intrahospital funding for Key Members of the National Natural Science Foundation of China Team in 2024 (Project Code: 00802722). Fujian Provincial Joint Funds for Science and Technology Innovation (Grant No. 2024Y9042). Fujian Provincial Central Government-Guided Local Science and Technology Development Funds (Grant No. 2024L3002).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence, and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors, wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcvm.2026.1737344/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

ABI, ankle-brachial index; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; baPWV, brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity; BMI, body mass index; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; DM, diabetes mellitus; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; FAR, fibrinogen-to-albumin ratio; FBG, fasting blood glucose; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; HR, heart rate; HTN, hypertension; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; MACEs, major adverse cardiovascular events; MABP, mean arterial blood pressure; PLT, platelet count; RCS, restricted cubic spline; CRP, C-reactive protein; SBP, systolic blood pressure; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; UA, uric acid.

References

1.

Benny P Kuerec AH Yu J Lee J Yang Q Maier AB et al Biomarkers of female reproductive aging in gerotherapeutic clinical trials. Ageing Res Rev. (2025) 112:102901. 10.1016/j.arr.2025.102901

2.

Joynt Maddox KE Elkind MSV Aparicio HJ Commodore-Mensah Y de Ferranti SD Dowd WN et al Forecasting the burden of cardiovascular disease and stroke in the United States through 2050-prevalence of risk factors and disease: a presidential advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. (2024) 150:e65–88. 10.1161/cir.0000000000001256

3.

Qiu Y Liu Y Tao J . Progress of clinical evaluation for vascular aging in humans. J Transl Int Med. (2021) 9:17–23. 10.2478/jtim-2021-0002

4.

Fu J Deng Y Ma Y Man S Yang X Yu C et al National and provincial-level prevalence and risk factors of carotid atherosclerosis in Chinese adults. JAMA Netw Open. (2024) 7(1):e2351225. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.51225

5.

Badhwar S Marais L Khettab H Poli F Li Y Segers P et al Clinical validation of carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity measurement using a multi-beam Laser vibrometer: the CARDIS study. Hypertension. (2024) 81:1986–95. 10.1161/hypertensionaha.124.22729

6.

Stone K Veerasingam D Meyer ML Heffernan KS Higgins S Maria Bruno R et al Reimagining the value of brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity as a biomarker of cardiovascular disease risk-A call to action on behalf of VascAgeNet. Hypertension. (2023) 80:1980–92. 10.1161/hypertensionaha.123.21314

7.

Hörber S Prystupa K Jacoby J Fritsche A Kleber ME Moissl AP et al Blood coagulation in prediabetes clusters-impact on all-cause mortality in individuals undergoing coronary angiography. Cardiovasc Diabetol. (2024) 23:306. 10.1186/s12933-024-02402-z

8.

Poole LG Kopec AK Flick MJ Luyendyk JP . Cross-linking by tissue transglutaminase-2 alters fibrinogen-directed macrophage proinflammatory activity. J Thromb Haemost. (2022) 20:1182–92. 10.1111/jth.15670

9.

Canseco-Avila LM Lopez-Roblero A Serrano-Guzman E Aguilar-Fuentes J Jerjes-Sanchez C Rojas-Martinez A et al Polymorphisms −455G/A and −148C/T and fibrinogen plasmatic level as risk markers of coronary disease and major adverse cardiovascular events. Dis Markers. (2019) 2019:5769514. 10.1155/2019/5769514

10.

Fang Y Huang S Zhang H Yu M . The association between fibrinogen-to-albumin ratio and adverse prognosis in patients with myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries. Int J Cardiol. (2025) 418:132665. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2024.132665

11.

Ronit A Kirkegaard-Klitbo DM Dohlmann TL Lundgren J Sabin CA Phillips AN et al Plasma albumin and incident cardiovascular disease: results from the CGPS and an updated meta-analysis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. (2020) 40:473–82. 10.1161/atvbaha.119.313681

12.

Tabata F Wada Y Kawakami S Miyaji K . Serum albumin redox states: more than oxidative stress biomarker. Antioxidants (Basel). (2021) 10:503. 10.3390/antiox10040503

13.

Austermeier S Pekmezović M Porschitz P Lee S Kichik N Moyes DL et al Albumin neutralizes hydrophobic toxins and modulates Candida albicans pathogenicity. mBio. (2021) 12:e0053121. 10.1128/mBio.00531-21

14.

Pignatelli P Farcomeni A Menichelli D Pastori D Violi F . Serum albumin and risk of cardiovascular events in primary and secondary prevention: a systematic review of observational studies and Bayesian meta-regression analysis. Intern Emerg Med. (2020) 15:135–43. 10.1007/s11739-019-02204-2

15.

Chien SC Lan WR Yun CH Sung KT Yeh HI Tsai CT et al Functional and prognostic impacts of serum albumin with thoracic arterial calcification among asymptomatic individuals. Sci Rep. (2024) 14:25477. 10.1038/s41598-024-77228-6

16.

Wang Y Bai L Li X Yi F Hou H . Fibrinogen-to-albumin ratio and clinical outcomes in patients with large artery atherosclerosis stroke. J Am Heart Assoc. (2023) 12:e030837. 10.1161/jaha.123.030837

17.

Li X Wang Z Zhu Y Lv H Zhou X Zhu H et al Prognostic value of fibrinogen-to-albumin ratio in coronary three-vessel disease. J Inflamm Res. (2023) 16:5767–77. 10.2147/jir.S443282

18.

Levey AS Stevens LA Schmid CH Zhang YL Castro AF Feldman HI et al A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. (2009) 150:604–12. 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006

19.

Zheng M Zhang X Chen S Song Y Zhao Q Gao X et al Arterial stiffness preceding diabetes: a longitudinal study. Circ Res. (2020) 127:1491–8. 10.1161/circresaha.120.317950

20.

Hetherington I Totary-Jain H . Anti-atherosclerotic therapies: milestones, challenges, and emerging innovations. Mol Ther. (2022) 30:3106–17. 10.1016/j.ymthe.2022.08.024

21.

Zamani M Cheng YH Charbonier F Gupta VK Mayer AT Trevino AE et al Single-cell transcriptomic census of endothelial changes induced by matrix stiffness and the association with atherosclerosis. Adv Funct Mater. (2022) 32:2203069. 10.1002/adfm.202203069

22.

Özdemir M Yurtdaş M Asoğlu R Yildirim T Aladağ N Asoğlu E . Fibrinogen to albumin ratio as a powerful predictor of the exaggerated morning blood pressure surge in newly diagnosed treatment-naive hypertensive patients. Clin Exp Hypertens. (2020) 42:692–9. 10.1080/10641963.2020.1779282

23.

Karahan O Acet H Ertaş F Tezcan O Çalişkan A Demir M et al The relationship between fibrinogen to albumin ratio and severity of coronary artery disease in patients with STEMI. Am J Emerg Med. (2016) 34:1037–42. 10.1016/j.ajem.2016.03.003

24.

Li M Tang C Luo E Qin Y Wang D Yan G . Relation of fibrinogen-to-albumin ratio to severity of coronary artery disease and long-term prognosis in patients with non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome. BioMed Res Int. (2020) 2020:1860268. 10.1155/2020/1860268

25.

Erdoğan G Arslan U Yenercağ M Durmuş G Tuğrul S Şahin İ . Relationship between the fibrinogen-to-albumin ratio and SYNTAX score in patients with non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Rev Invest Clin. (2021) 73:182–9. 10.24875/ric.20000534

26.

Zhang DP Mao XF Wu TT Chen Y Hou XG Yang Y et al The fibrinogen-to-albumin ratio is associated with outcomes in patients with coronary artery disease who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. (2020) 26:1076029620933008. 10.1177/1076029620933008

27.

Zheng L Wang Z Liu J Yang X Zhang S Hao Z et al Association between admission blood fibrinogen-to-albumin ratio and clinical outcomes after acute lacunar stroke. Biomark Med. (2021) 15:87–96. 10.2217/bmm-2019-0537

28.

Zeng Y Buonfiglio F Li J Pfeiffer N Gericke A . Mechanisms underlying vascular inflammaging: current insights and potential treatment approaches. Aging Dis. (2024) 16:1889–917. 10.14336/ad.2024.0922

29.

Aminuddin A Lazim M Hamid AA Hui CK Mohd Yunus MH Kumar J et al The association between inflammation and pulse wave velocity in dyslipidemia: an evidence-based review. Mediat Inflamm. (2020) 2020:4732987. 10.1155/2020/4732987

30.

Raberin A Burtscher J Connes P Millet GP . Hypoxia and hemorheological properties in older individuals. Ageing Res Rev. (2022) 79:101650. 10.1016/j.arr.2022.101650

31.

Nencini F Borghi S Giurranna E Barbaro I Taddei N Fiorillo C et al Reactive nitrogen species and fibrinogen: exploring the effects of nitration on blood clots. Antioxidants (Basel). (2025) 14:825. 10.3390/antiox14070825

32.

Nencini F Giurranna E Borghi S Taddei N Fiorillo C Becatti M . Fibrinogen oxidation and thrombosis: shaping structure and function. Antioxidants (Basel). (2025) 14:390. 10.3390/antiox14040390

33.

Allison SP Lobo DN . The clinical significance of hypoalbuminaemia. Clin Nutr. (2024) 43:909–14. 10.1016/j.clnu.2024.02.018

34.

Jiang Y Yang Z Wu Q Cao J Qiu T . The association between albumin and C-reactive protein in older adults. Medicine (Baltimore). (2023) 102:e34726. 10.1097/md.0000000000034726

35.

Watanabe K Kinoshita H Okamoto T Sugiura K Kawashima S Kimura T . Antioxidant properties of albumin and diseases related to obstetrics and gynecology. Antioxidants (Basel). (2025) 14:55. 10.3390/antiox14010055

36.

Violi F Novella A Pignatelli P Castellani V Tettamanti M Mannucci PM et al Low serum albumin is associated with mortality and arterial and venous ischemic events in acutely ill medical patients. Results of a retrospective observational study. Thromb Res. (2023) 225:1–10. 10.1016/j.thromres.2023.02.013

37.

Valeriani E Pannunzio A Palumbo IM Bartimoccia S Cammisotto V Castellani V et al Risk of venous thromboembolism and arterial events in patients with hypoalbuminemia: a comprehensive meta-analysis of more than 2 million patients. J Thromb Haemostasis. (2024) 22:2823–33. 10.1016/j.jtha.2024.06.018

38.

Waller AP Wolfgang KJ Stevenson ZS Holle LA Wolberg AS Kerlin BA . Hypoalbuminemia increases fibrin clot density and impairs fibrinolysis. J Thromb Haemostasis. (2025) 17:00647–6. 10.1016/j.jtha.2025.09.028

Summary

Keywords

arteriosclerosis, brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity, elderly, fibrinogen-to-albumin ratio, vascular aging

Citation

Zhang Y, Lu N, Liu Y, Ke J, Hu E, Chai S and Chen H (2026) The relationship between fibrinogen-to-albumin ratio and brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity in elderly individuals in China: a cross-sectional study. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 13:1737344. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2026.1737344

Received

01 November 2025

Revised

07 January 2026

Accepted

08 January 2026

Published

09 February 2026

Volume

13 - 2026

Edited by

Junjun Li, Osaka University, Japan

Reviewed by

Yunteng Fang, Lishui Central Hospital, China

Jingbo Zhang, First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Zhang, Lu, Liu, Ke, Hu, Chai and Chen.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Haifeng Chen drchf1975@126.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.