Abstract

Objective:

This study aimed to identify the independent risk factors for calf muscular vein thrombosis (CMVT) in elderly patients experiencing an acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD).

Methods:

A retrospective study was conducted involving 128 elderly patients (age ≥60 years) with AECOPD. Patients were categorized into CMVT and non-CMVT groups based on lower extremity venous color Doppler ultrasound findings. Clinical characteristics and laboratory parameters were compared between the groups. Statistically significant variables from univariate analysis were incorporated into a multivariate logistic regression analysis to identify independent risk factors. The predictive performance of these factors was evaluated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis.

Results:

Multivariate logistic regression identified reduced calf circumference [Odds Ratio (OR) = 0.25, 95% Confidence Interval (CI): 0.1–0.59], elevated red blood cell (RBC) count (OR = 19.85, 95% CI: 1.08–363.96), and elevated D-dimer level (OR = 1.84, 95% CI: 1.13–3.01) as independent risk factors for CMVT. ROC curve analysis demonstrated good predictive performance for these factors, with areas under the curve (AUC) of 0.986 for calf circumference, 0.788 for RBC count, and 0.976 for D-dimer.

Conclusion:

Reduced calf circumference, elevated RBC count, and elevated D-dimer level are significant independent risk factors for CMVT in elderly AECOPD patients. Monitoring these indicators could aid clinicians in the early identification and prevention of CMVT in this vulnerable population.

1 Introduction

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) is a common, preventable, and treatable chronic airway disease characterized by persistent airflow limitation and corresponding respiratory symptoms. The primary clinical manifestations of COPD include chronic cough, sputum production, and dyspnea. According to the Global Burden of Disease study, COPD is the fifth leading cause of death in China. With the accelerating aging of the population, the prevalence of COPD is projected to continue rising over the next 40 years, and the annual number of deaths due to COPD and its related complications is expected to exceed 5 million in the coming decades (1, 2).

Calf muscular vein thrombosis (CMVT) refers to thrombosis that originates and is confined to the venous plexus of the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles, belonging to the category of peripheral deep vein thrombosis (DVT). The soleal and gastrocnemius venous plexuses are the most frequently involved sites, primarily attributable to factors such as their narrow lumina, numerous tributaries, sparse venous valves, and lack of deep fascial envelopment (3). Due to the minimal impact of CMVT on venous return and the weak systemic inflammatory response it elicits, affected patients are often asymptomatic, leading to frequent underdiagnosis by clinicians (4).

In clinical practice, CMVT is not uncommonly among elderly patients experiencing acute exacerbation of COPD (AECOPD). Studies have reported a higher incidence of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in patients with COPD compared to those without COPD, with approximately 10.5% of AECOPD patients presenting with DVT (5–7). Advanced age has been identified as a risk factor for VTE, with the risk increasing correspondingly with age (8, 9). However, the exact incidence of CMVT in elderly patients with AECOPD remains unclear. Failure to identify CMVT early in elderly patients with AECOPD may lead to proximal thrombus extension and development to DVT, potentially even triggering fatal pulmonary embolism (3). Moreover, research specifically focused on CMVT in elderly patients with AECOPD is relatively limited. This study aimed to retrospectively analyze the main risk factors for CMVT in this population to assist clinicians in the early and effective identification of high-risk patients, thereby providing a basis for early thromboprophylaxis strategies.

2 Subjects and Methods

2.1 Subjects

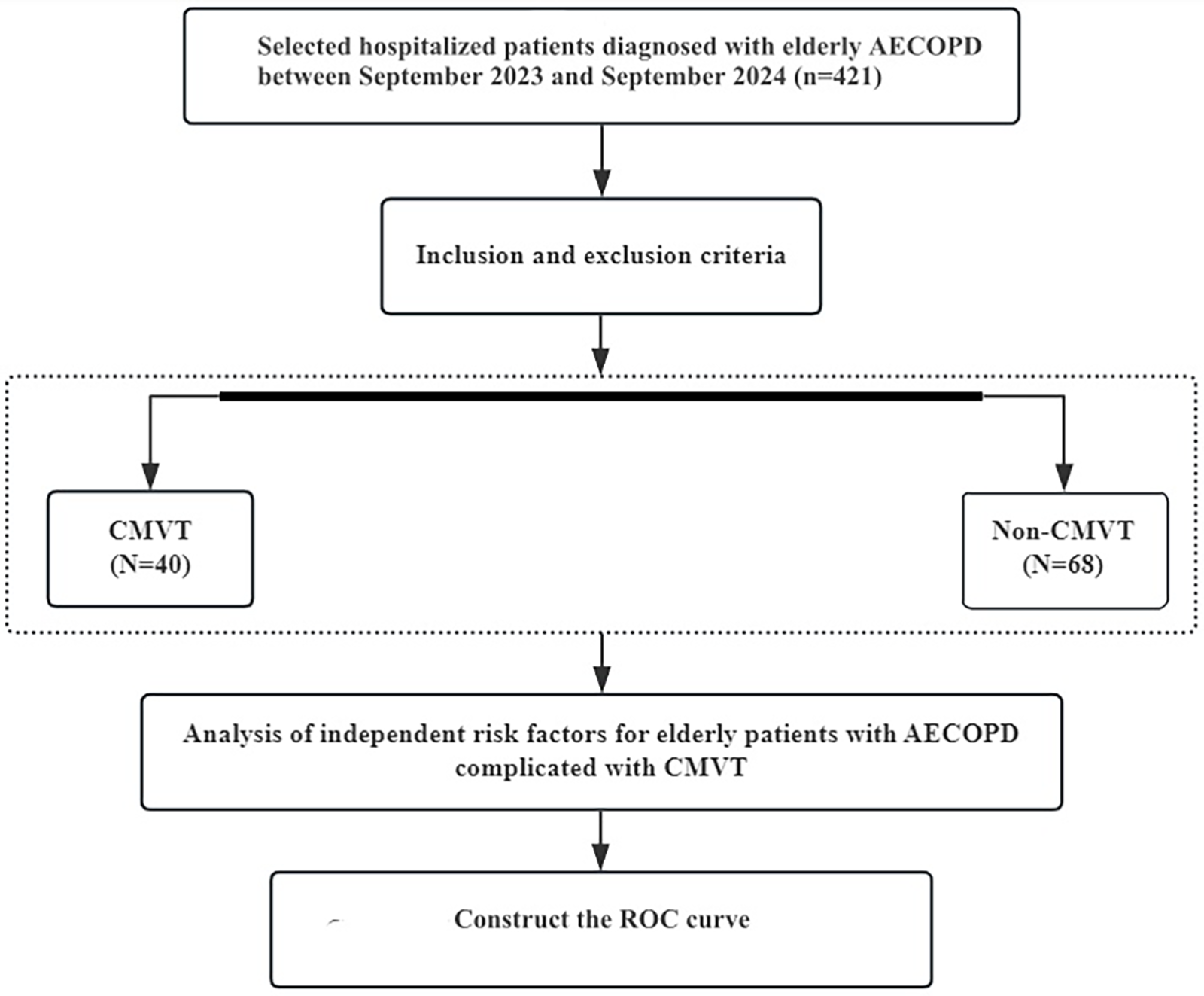

A total of 421 patients with AECOPD who were treated in the Deyang People's Hospital between September 2023 and September 2024 were included in this retrospective study. Inclusion criteria: (1) Age ≥60 years. (2) Discharge diagnosis of AECOPD, consistent with the diagnostic criteria established in the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) 2023 Guidelines (10). This required the presence of symptoms such as chronic cough, sputum production, dyspnea, wheezing, or chest tightness, along with pulmonary function tests confirming persistent airflow limitation [post-bronchodilator forced expiratory volume in the 1st second/forced vital capacity (FEV1/FVC) < 70%]. Exclusion criteria: (1) Age <60 years. (2) Incomplete medical records. (3) Missing essential laboratory data or absence of relevant imaging studies. (4) Presence of DVT in locations other than the calf muscular veins; (5) Coexisting diagnoses of bronchial asthma, bronchiectasis, pulmonary tuberculosis, diffuse panbronchiolitis, lung cancer, or pulmonary embolism. Finally, 128 elderly patients with AECOPD were enrolled in the study, among whom 40 patients were diagnosed with concomitant CMVT, and 88 patients were without CMVT (Figure 1). Technique and diagnostic criteria for lower limb venous ultrasonography: (1) The primary criterion was the incomplete or absent compressibility of the venous lumen under transducer pressure. (2) Intraluminal Filling Defect: Visualization of an echogenic or hypoechoic filling defect within the vein. (3) Absence of Spontaneous Flow: Lack of spontaneous color Doppler or spectral Doppler flow signal within the affected venous segment. (4) Loss of Flow Phasicity: Absence of normal respiratory phasicity in Doppler waveform in veins proximal to the thrombus (if assessable). This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Deyang People's Hospital.

Figure 1

Flow chart describing the research method.

2.2 Data collection

The collected data included:

- 1.

Clinical data: age, gender, history of diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension, coronary heart disease (CHD), cerebral infarction, atrial fibrillation (AF), heart failure (HF), alcohol consumption, smoking, previous history of DVT, duration of hospital stay, history of mechanical ventilation, receipt of prophylactic anticoagulation (during hospitalization), and calf circumference (measured at the maximum circumference of the non-dominant lower limb).

- 2.

Laboratory data at admission: white blood cell count (WBC), neutrophil count (NEUT), red blood cell count (RBC), platelet count (PLT), D-dimer, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), albumin (ALB), Creatinine, pH, arterial partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2), arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PaCO2), serum sodium, serum potassium, blood lactate, blood uric acid, prothrombin time (PT), international normalized ratio (INR), activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), fibrinogen (FIB), and thrombin time (TT).

- 3.

Examination data: pulmonary function grade, severity of COPD exacerbation, and presence or absence of sputum production.

- 4.

Group definitions: Elderly COPD patients with concurrent CMVT were classified as the CMVT group, while those without CMVT were the non-CMVT group.

2.3 Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software (version 26.0). Continuous variables conforming to a normal distribution are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and comparisons between groups were conducted using the independent samples t-test. Categorical data are presented as numbers (percentages), and intergroup comparisons were performed using the chi-square (χ2) test. Continuous variables with a non-normal distribution are presented as median and interquartile range [M (P25, P75)], and the Mann–Whitney U-test was used for group comparisons. Statistically significant variables were identified through univariate analysis.

Variables that showed significant in the univariate analysis were included in a multivariate logistic regression analysis to identify independent risk factors, and their odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated. The predictive performance of the independent risk factors was evaluated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis, and the area under the curve (AUC) was calculated.

3 Results

3.1 Comparison of clinical characteristics

Compared with the non-CMVT group, the CMVT group demonstrated a significantly smaller calf circumference (P < 0.05, Table 1). However, no statistically significant differences were observed between the two groups regarding age, gender, history of DM, hypertension, CHD, cerebral infarction, alcohol consumption, smoking, prolonged immobilization, previous history of DVT, duration of hospital stay, history of mechanical ventilation, receipt of prophylactic anticoagulation (during hospitalization) or severity of COPD exacerbation (P > 0.05, Table 2).

Table 1

| Laboratory Data | N-CMVT (n = 68) | CMVT (n = 40) | T/Z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC (×109) | 8.44 ± 3.45 | 9.62 ± 4.41 | −1.493 | 0.141 |

| NEU (×109) | 6.61 ± 3.35 | 8.93 ± 10.38 | −1.382 | 0.174 |

| RBC (×1012) | 4.2 ± 0.84 | 5.08 ± 0.85* | −5.419 | <0.001 |

| pH | 7.38 ± 0.06 | 7.4 ± 0.08 | −1.019 | 0.312 |

| PaCO2 (mmHg) | 50.84 ± 14.44 | 48.56 ± 15.61 | 0.806 | 0.422 |

| PaO2 (mmHg) | 89.08 ± 15.9 | 76.86 ± 12.59 | 0.778 | 0.003 |

| PLT (×109) | 194.12 ± 75.96 | 180.85 ± 75.01 | 0.92 | 0.359 |

| hs-CRP (mg/L) | 34.2 ± 44.89 | 45.68 ± 56.25 | −1.123 | 0.266 |

| PT (s) | 12.56 ± 2.56 | 12.38 ± 1.01 | 0.582 | 0.562 |

| ALT (U/L) | 24 (18,32) | 23.5 (19.75,36) | −0.702 | 0.483 |

| AST (U/L) | 26 (19.75,33.5) | 30 (22,37) | −1.615 | 0.106 |

| INR | 1.09 ± 0.24 | 1.06 ± 0.09 | 0.746 | 0.457 |

| APTT (s) | 26.54 ± 2.31 | 27.55 ± 3.43 | −1.695 | 0.096 |

| FIB (g/L) | 4.47 ± 1.71 | 4.5 ± 1.81 | −0.088 | 0.93 |

| TT (s) | 18.93 ± 1.48 | 18.69 ± 1.22 | 0.864 | 0.389 |

| D-dimer (mg/L FEU) | 1.43 ± 3.01 | 6.36 ± 2.39* | −9.132 | <0.001 |

| ALB (g/L) | 38.82 ± 6.34 | 37.09 ± 4.79 | 1.704 | 0.091 |

| Creatinine (mmol/L) | 78.11 ± 34 | 77.03 ± 22.83 | 0.211 | 0.834 |

| Blood Uric Acid (umol/L) | 330.53 ± 115.32 | 312.52 ± 137.93 | 0.769 | 0.443 |

| Serum Potassium (mmol/L) | 3.76 ± 0.62 | 3.87 ± 0.48 | −1.163 | 0.248 |

| Serum Sodium (mmol/L) | 137.46 ± 4.54 | 136.59 ± 3.64 | 1.064 | 0.289 |

| Blood Lactate (mmol/L) | 1.91 ± 0.74 | 1.75 ± 0.61 | 1.143 | 0.255 |

Laboratory data at admission.

Compared with N-CMVT, p < 0.05.

Table 2

| Parameters | N-CMVT (n = 68) | CMVT (n = 40) | χ2/t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 75.11 ± 9.02 | 73.78 ± 7.81 | 0.81 | 0.419 |

| Calf circumference (cm) | 33.3 ± 2.74 | 25.89 ± 2.43* | 14.672 | <0.001 |

| Duration of hospital (d) | 9.02 ± 2.36 | 8.93 ± 2.83 | 0.204 | 0.839 |

| Gender (n) | ||||

| Female | 31 (35.2%) | 12 (30%) | 0.337 | 0.562 |

| Male | 57 (64.8%) | 28 (70%) | ||

| Diabetes mellitus (n) | ||||

| No | 74 (84.1%) | 30 (75%) | 1.492 | 0.222 |

| Yes | 14 (15.9%) | 10 (25%) | ||

| Hypertension (n) | ||||

| No | 57 (64.8%) | 24 (60%) | 0.27 | 0.604 |

| Yes | 31 (35.2%) | 16 (40%) | ||

| CHD (n) | ||||

| No | 81 (92%) | 34 (85%) | 0.823 | 0.364 |

| Yes | 7 (8%) | 6 (15%) | ||

| Cerebral infarction (n) | ||||

| No | 85 (96.6%) | 37 (92.5%) | 0.318 | 0.573 |

| Yes | 3 (3.4%) | 3 (7.5%) | ||

| Atrial fibrillation (n) | ||||

| No | 85 (96.6%) | 38 (95%) | 0 | 1 |

| Yes | 3 (3.4%) | 2 (5%) | ||

| Heart failure (n) | ||||

| No | 83 (94.3%) | 35 (87.5%) | 0.955 | 0.329 |

| Yes | 5 (5.7%) | 5 (12.5%) | ||

| Alcohol consumption (n) | ||||

| No | 54 (61.4%) | 18 (45%) | 2.992 | 0.084 |

| Yes | 34 (38.6%) | 22 (55%) | ||

| Smoking (n) | ||||

| No | 40 (45.5%) | 15 (37.5%) | 0.71 | 0.399 |

| Yes | 7 (8%) | 8 (20%) | ||

| History of DVT (n) | ||||

| No | 83 (94.3%) | 35 (87.5%) | 0.955 | 0.329 |

| Yes | 5 (5.7%) | 5 (12.5%) | ||

| Sputum (n) | ||||

| No | 42 (47.7%) | 17 (42.5%) | 0.302 | 0.582 |

| Yes | 46 (52.3%) | 23 (57.5%) | ||

| Pulmonary function grade (n) | ||||

| 1 | 3 (3.4%) | 5 (12.5%) | 3.894 | 0.273 |

| 2 | 21 (23.9%) | 9 (22.5%) | ||

| 3 | 39 (44.3%) | 16 (40%) | ||

| 4 | 25 (28.4%) | 10 (25%) | ||

| Severity of COPD exacerbation (n) | ||||

| Grade 1 | 23 (26.1%) | 10 (25%) | 0.198 | 0.906 |

| Grade 2 | 36 (40.9%) | 18 (45%) | ||

| Grade 3 | 29 (33%) | 12 (30%) | ||

| History of mechanical ventilation (n) | ||||

| No | 80 (90.9%) | 36 (90%) | 0 | 1 |

| Yes | 8 (9.1%) | 4 (10%) | ||

| Receiving prophylactic anticoagulation (during hospitalization) (n) | ||||

| No | 82 (93.2%) | 37 (92.5%) | 0 | 1 |

| Yes | 6 (6.8%) | 3 (7.5%) | ||

Clinical characteristics.

Compared with N-CMVT, p < 0.05.

3.2 Comparison of laboratory parameters

Compared with the non-CMVT group, the CMVT group exhibited significantly higher RBC count and D-dimer levels (P < 0.05), along with a significantly lower PaO2 (P < 0.05). No statistically significant differences were found between the two groups in terms of WBC, NEUT, PLT, hs-CRP, AST, ALT, ALB, pH, PaCO2, serum sodium, serum potassium, blood lactate, blood uric acid, PT, INR, APTT, FIB, or TT upon admission (P > 0.05, Table 1).

3.3 Multivariate analysis of CMVT in elderly patients with AECOPD

A multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed using the presence or absence of CMVT as the dependent variable, and the factors showing statistical significance in the univariate analysis (Calf circumference, RBC, D-dimer, PaO2) as independent variables. Calf circumference was identified as a protective factor against CMVT. Conversely, RBC count and D-dimer level were identified as independent risk factors for CMVT in elderly patients with AECOPD (P < 0.05, Table 3).

Table 3

| Variable | B | SE | z | p | OR [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calf Circumference | −1.403 | 0.444 | −3.162 | 0.002 | 0.25 [0.1, 0.59] |

| RBC | 2.988 | 1.484 | 2.013 | 0.044 | 19.85 [1.08, 363.96] |

| D-dimer | 0.611 | 0.249 | 2.451 | 0.014 | 1.84 [1.13, 3.01] |

Multivariate logistic regression analysis of independent risk factors for CMVT in elderly patients with AECOPD.

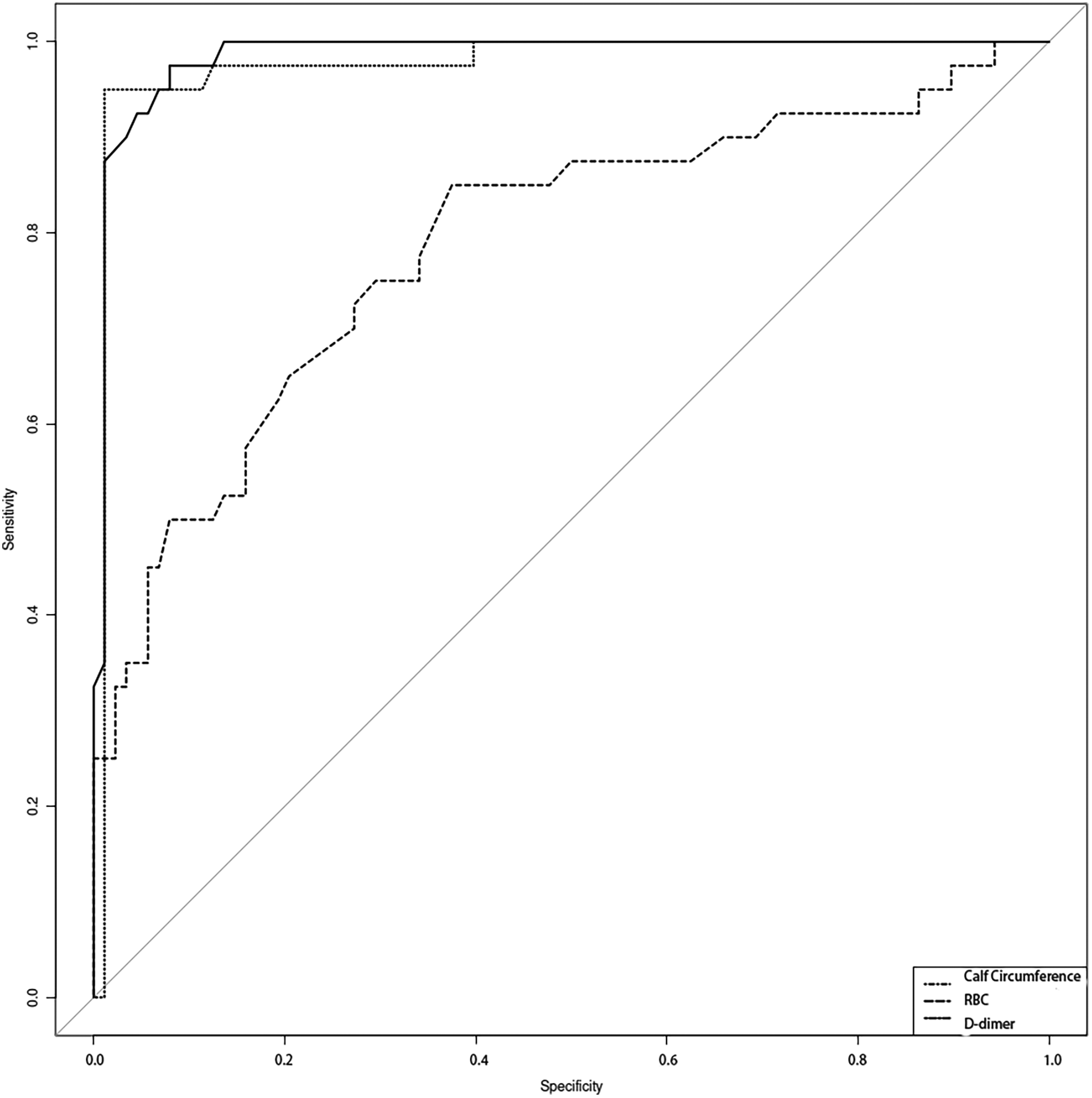

3.4 Predictive value of independent risk factors for CMVT

Using the presence or absence of CMVT as the dependent variable, the probability values derived from the logistic regression model for the independent risk factors (Calf circumference, RBC count, D-dimer level) were used to construct the ROC curve. For calf circumference, the AUC was 0.986 (95% CI: 0.968–1.004), sensitivity was 0.975, and specificity was 0.92. For RBC count, the AUC was 0.788 (95% CI: 0.7–0.876), sensitivity was 0.85, and specificity was 0.625. For D-dimer level, the AUC was 0.976 (95% CI: 0.947–1.005), sensitivity was 0.95, and specificity was 0.989 (Table 4 and Figure 2). The ROC analysis indicates that the model incorporating these factors exhibits good predictive performance.

Table 4

| Variable | n | AUC | SE | AUC [95% CI] | Cutoff value | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calf circumference | 128 | 0.986 | 0.009 | [0.968, 1.004] | 30.15 | 0.975 | 0.92 |

| RBC | 128 | 0.788 | 0.045 | [0.7, 0.876] | 4.48 | 0.85 | 0.625 |

| D-dimer | 128 | 0.976 | 0.015 | [0.947, 1.005] | 3.31 | 0.95 | 0.989 |

Predictive performance of independent risk factors for CMVT in elderly patients with AECOPD.

Figure 2

The predictive capacity of calf circumference, RBC, and D-dimer levels for chronic thromboembolism in elderly COPD patients was evaluated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis.

4 Discussion

COPD is a common condition that poses a severe threat to human health, not only significantly impairing quality of life but also representing one of the leading causes of mortality. Epidemiological data indicate that the prevalence of COPD among individuals aged 40 years and above in China is as high as 13.7%, corresponding to an estimated patient population of nearly 100 million, underscoring a persistently high disease burden (11). Patients with AECOPD are often confined to bed due to dyspnea and reduced exercise tolerance. Prolonged immobilization can diminish lower limb mobility, leading to venous stasis and thereby increasing susceptibility to thrombosis (12). Additionally, AECOPD is frequently complicated by hypoxia, which can elevate blood viscosity and further promote thrombus formation (13). Specifically, hypoxic stimulation induces compensatory erythropoietin (EPO) production, triggering reactive erythrocytosis, which subsequently increases blood viscosity and promotes a prothrombotic state (13). Consequently, VTE, including DVT and pulmonary embolism, is relatively common in patients with AECOPD.

Through statistical analysis of clinical and laboratory data from elderly patients with AECOPD, this study identified calf circumference, RBC count, D-dimer, and PaO2 as predictors for CMVT. Subsequent multivariate logistic regression analysis confirmed that calf circumference, RBC count, and D-dimer are independent risk factors for CMVT in this population. Although PaO2 did not emerge as an independent risk factor in the multivariate model, it remained significantly associated with CMVT risk, highlighting its clinical relevance. Established mechanistic studies have demonstrated that hypoxia can induce a hypercoagulable state by upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), EPO, and hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) (14–16). Among these, HIF may particularly promote VT via signaling pathways such as VEGF/STAT3 and NLRP3. Furthermore, HIF subunits possess immunomodulatory functions, and the NLRP3 inflammasome, induced by HIF, contributes to thrombogenesis (17, 18). The observed association between lower PaO2 and CMVT risk in this study is consistent with these established mechanisms.

Muscle mass progressively declines with age, a process associated with reduced activity of oxidative enzymes and decreased mitochondrial content in muscle cells. In elderly patients with COPD, factors such as chronic disease burden, systemic inflammation, and physical inactivity accelerate muscle loss, leading to a higher prevalence of sarcopenia (19, 20). Calf circumference is a simple and easily obtainable anthropometric indicator related to muscle mass. Numerous studies have associated reduced calf circumference with prolonged hospitalization, increased readmission rates, and malnutrition in patients with AECOPD (21–23). Our findings identify reduced calf circumference as an independent risk factor for CMVT. In elderly patients with AECOPD, significant atrophy of the calf muscles-clinically manifested as decreased calf circumference-compromises the function of the calf muscle pump. This impairment results in venous stasis in the lower limbs, establishing a predisposing condition for the development of CMVT (3, 24). Therefore, in elderly AECOPD patients with reduced calf circumference, clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for CMVT, and prompt screening via lower limb venous ultrasonography is crucial.

This retrospective study identified polycythemia (manifested as elevated RBC count) as a significant risk factor for CMVT in the elderly AECOPD population. Polycythemia is relatively common in patients with COPD, as chronic hypoxia stimulates EPO production and promotes RBC proliferation (25). In the context of CMVT development, polycythemia may exacerbate thrombosis risk through several mechanisms. First, increased RBC concentration elevates blood viscosity and reduce flow velocity in the venous system, particularly in the calf muscle regions where elderly patients with AECOPD often exhibit significant venous stasis due to limited mobility. Such hemodynamic alteration promotes endothelial activation and platelet aggregation, thereby accelerating thrombus formation (26, 27). Additionally, polycythemia may indirectly influence coagulation function by enhancing oxidative stress and inflammatory responses—both of which are markedly intensified during AECOPD and are known to increase the risk of VTE (28, 29). The interaction between chronic inflammation in COPD and polycythemia might further amplify the prothrombotic state. However, the retrospective nature of this study precludes causal inference, and potential confounding factors such as concomitant medications, comorbidities, or variations in COPD severity may have influenced these associations.

D-dimer, a fibrin degradation product, is considered to play a critical role in the thrombotic processes associated with AECOPD (30). Our study identified elevated D-dimer as an independent risk factor for CMVT in elderly patients with AECOPD. Patients with COPD often exhibit chronic inflammation, hypoxemia, and endothelial dysfunction, all of which can activate the coagulation system, leading to increased D-dimer levels. In the context of CMVT, elevated D-dimer may reflect ongoing fibrinolysis and thrombotic burden, thereby increasing the risk of venous thrombotic events (13, 30–33). Specifically, the systemic inflammatory state in COPD may promote a hypercoagulable state by upregulating pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-6), which enhance thrombin generation and fibrin formation (34–36). Furthermore, chronic hypoxia may exacerbate this process by altering the fibrinolytic balance through the HIF pathway, positioning D-dimer as a potential biomarker for assessing the risk of thrombosis (37, 38).

A study by Hu et al. (39) also adopted a retrospective design to develop a prediction model for CMVT in AECOPD patients, identifying hypertension, elevated mean platelet volume (MPV), ALB, elevated D-dimer, and bed rest ≥3 days as independent risk factors. Consistent with their findings, our study also confirms that elevated D-dimer is a significant and strong independent risk factor for CMVT, further reinforcing the important role of elevated D-dimer in predicting COPD combined with CMVT. Different from the study by Hu et al., our current research focuses specifically on an elderly population (age ≥60 years). In our results, we did not find hypertension or ALB to be independent predictors. Instead, we identified reduced calf circumference and elevated RBC count as significant independent risk factors. The reason for this difference in results may be related to the different study populations selected. The elderly AECOPD patients aged 60 years and above have a higher incidence of sarcopenia and age-related muscle loss. Identifying reduced calf circumference as a protective factor against CMVT highlights the critical role of the calf muscle pump in venous return. In addition, while the Hu et al. study focused on platelet indices (MPV), our findings emphasize the hemorheological component of thrombosis risk, namely RBC count. Our results suggest that risk assessment tools may need to be tailored for specific age subgroups within the AECOPD population. Where necessary, prospective studies comparing these risk factors across different age groups should be conducted to refine prevention strategies.

It is important to emphasize that D-dimer elevation is nonspecific and may be influenced by various conditions such as infection, malignancy, or recent surgery, which are prevalent in elderly patients with AECOPD. Therefore, although this study has revealed an association between D-dimer and CMVT, the causal relationship remains unclear. D-dimer may be more a consequence rather than a direct cause of thrombosis. Nonetheless, clinicians should maintain vigilance and consider early screening for CMVT in elderly AECOPD patients with elevated D-dimer levels.

Notably, the statistical results of this study did not identify age as a significant risk factor for CMVT in this elderly AECOPD cohort, which contrasts with numerous previous studies reporting advanced age as a risk factor for VTE (40–42). This discrepancy may be attributed to the inherent age restriction of the study population (≥60 years), a design feature that may have minimized the age variation and its effect within this specific elderly cohort.

5 Strengths and limitations

This study has several limitations, including its retrospective, single-center design, relatively small sample size, lack of internal or external validation, and potential residual confounding from unmeasured factors (e.g., concomitant medications). Given the inherent limitations of the retrospective study design, the current findings should be considered hypothesis-generating rather than conclusive. Ideally, larger-scale, and preferably multicenter, prospective studies are warranted to validate our results. These should involve serial measurements of calf circumference, RBC, and D-dimer in elderly patients with AECOPD to enable dynamic assessment of the risk for CMVT.

6 Conclusion

In conclusion, this study confirms that reduced calf circumference, elevated RBC count, and elevated D-dimer levels are independent risk factors for the development of CMVT in elderly patients with AECOPD. Consequently, clinicians should closely monitor these indicators during the diagnosis and treatment of such patients to achieve early prevention and detection of CMVT.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Deyang Peoples Hospital (2024-04-107-K01). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

XL: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Formal analysis, Resources, Data curation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. SX: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Conceptualization, Validation, Data curation, Supervision, Methodology. XW: Formal analysis, Resources, Investigation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Validation, Visualization. YL: Resources, Data curation, Writing – original draft. CZ: Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization. YH: Validation, Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Project administration. RW: Visualization, Formal analysis, Resources, Software, Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Validation, Methodology.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Sichuan Nursing Vocational College [No. 2024ZRY28] and the Intramural Research Grant Program of Deyang People’s Hospital [No. FHT202412].

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

CMVT, calf muscular vein thrombosis; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; AECOPD, acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; RBC, red blood cell; AUC, areas under the curve; DVT, deep vein thrombosis; VTE, venous thromboembolism; CHD, coronary heart disease; AF, atrial fibrillation; HF, heart failure; WBC, white blood cell count; NEUT, neutrophil count; PLT, platelet count; hs-CRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; ALB, albumin; PaO2, arterial partial pressure of oxygen; PaCO2, arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide; PT, prothrombin time; INR, international normalized ratio; APTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; FIB, fibrinogen; TT, thrombin time; SPSS, Statistical Package for the Social Sciences; SD, standard deviation; EPO, erythropoietin; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; HIF, hypoxia-inducible factor; MPV, mean platelet volume.

References

1.

Fang L Gao P Bao H Tang X Wang B Feng Y et al Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in China: a nationwide prevalence study. Lancet Respir Med. (2018) 6(6):421–30. 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30103-6

2.

Park JE Zhang L Ho YF Liu G Alfonso-Cristancho R Ismaila AS et al Modeling the health and economic burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in China from 2020 to 2039: a simulation study. Value Health Reg Issues. (2022) 32:8–16. 10.1016/j.vhri.2022.06.002

3.

Jiang J Xing F Luo R Chen Z Liu H Xiang Z et al The effect of calf muscular vein thrombosis on the prognosis within one year postoperatively of geriatric hip fracture patients: a propensity score-matched analysis. BMC Geriatr. (2024) 24(1):1050. 10.1186/s12877-024-05601-1

4.

Wang C Zhou Y Ruan R . Application of acoustic radiation force pulse imaging technology in the evaluation of the efficacy of calf intermuscular vein thrombosis. Discov Med. (2024) 36(182):591–7. 10.24976/Discov.Med.202436182.55

5.

Duan SC Yang YH Li XY Liang XN Guo RJ Xie WM et al Prevalence of deep venous thrombosis in patients with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chin Med J. (2010) 123(12):1510–4.

6.

Dutt TS Udwadia ZF . Prevalence of venous thromboembolism in acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: an Indian perspective. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. (2011) 53(4):207–10. 10.5005/ijcdas-53-4-207

7.

Ahmed I Khan K Akhter N Amanullah Shah S Hidayatullah S Chawla D . Frequency of asymptomatic deep vein thrombosis in hospitalized patients with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Cureus. (2024) 16(9):e69858. 10.7759/cureus.69858

8.

Huang W Hu W Lei B Huang W . Risk factors for venous thrombosis after hip arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. (2025) 26(1):508. 10.1186/s12891-025-08764-z

9.

Wang P He L Yuan Q Lu J Ji Q Peng A et al Risk factors for peripherally inserted central catheter-related venous thrombosis in adult patients with cancer. Thromb J. (2024) 22(1):6. 10.1186/s12959-023-00574-4

10.

Sharma M Joshi S Banjade P Ghamande SA Surani S . Global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease (GOLD) 2023 guidelines reviewed. Open Respir Med J. (2024) 18:e18743064279064. 10.2174/0118743064279064231227070344

11.

Wang C Xu J Yang L Xu Y Zhang X Bai C et al Prevalence and risk factors of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in China [the China pulmonary health (CPH) study]: a national cross-sectional study. Lancet. (2018) 391(10131):1706–17. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30841-9

12.

Børvik T Brækkan SK Evensen LH Brodin EE Morelli VM Melbye H et al Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and risk of mortality in patients with venous thromboembolism-the Tromsø study. Thromb Haemostasis. (2020) 120(3):477–83. 10.1055/s-0039-3400744

13.

Chen L Xu W Chen J Zhang H Huang X Ma L et al Evaluating the clinical role of fibrinogen, D-dimer, mean platelet volume in patients with acute exacerbation of COPD. Heart Lung. (2023) 57:54–8. 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2022.08.013

14.

Ebersole JL Novak MJ Orraca L Martinez-Gonzalez J Kirakodu S Chen KC et al Hypoxia-inducible transcription factors, HIF1A and HIF2A, increase in aging mucosal tissues. Immunology. (2018) 154(3):452–64. 10.1111/imm.12894

15.

Yin BH Chen HC Zhang W Li TZ Gao QM Liu JW . Effects of hypoxia environment on osteonecrosis of the femoral head in Sprague-Dawley rats. J Bone Miner Metab. (2020) 38(6):780–93. 10.1007/s00774-020-01114-0

16.

Shaydakov ME Diaz JA Eklöf B Lurie F . Venous valve hypoxia as a possible mechanism of deep vein thrombosis: a scoping review. Int Angiol. (2024) 43(3):309–22. 10.23736/S0392-9590.24.05170-8

17.

Gupta N Sahu A Prabhakar A Chatterjee T Tyagi T Kumari B et al Activation of NLRP3 inflammasome complex potentiates venous thrombosis in response to hypoxia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (2017) 114(18):4763–8. 10.1073/pnas.1620458114

18.

Hao R Li H Li X Liu J Ji X Zhang H et al Transcriptomic profiling of lncRNAs and mRNAs in a venous thrombosis mouse model. iScience. (2025) 28(2):111561. 10.1016/j.isci.2024.111561

19.

Keller K Engelhardt M . Strength and muscle mass loss with aging process. Age and strength loss. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. (2013) 3(4):346–50. 10.32098/mltj.04.2013.17

20.

Wu ZY Lu XM Liu R Han YX Qian HY Zhao Q et al Impaired skeletal muscle in patients with stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) compared with non-COPD patients. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. (2023) 18:1525–32. 10.2147/COPD.S396728

21.

Lee KY Chen TT Chiang LL Chuang HC Feng PH Liu WT et al Proteasome activity related with the daily physical activity of COPD patients. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. (2017) 12:1519–25. 10.2147/COPD.S132276

22.

Bernardes S Silva FM da Costa CC de Souza RM Teixeira PJZ . Reduced calf circumference is an independent predictor of worse quality of life, severity of disease, frequent exacerbation, and death in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease admitted to a pulmonary rehabilitation program: a historic cohort study. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. (2022) 46(3):546–55. 10.1002/jpen.2214

23.

Huang J Quan J Zhou G Yu L Su Q Guo F et al Diagnostic value of different skeleton muscles in elderly COPD patients with sarcopenia. Eur J Med Res. (2025) 30(1):560. 10.1186/s40001-025-02856-1

24.

Houghton DE Ashrani A Liedl D Mehta RA Hodge DO Rooke T et al Reduced calf muscle pump function is a risk factor for venous thromboembolism: a population-based cohort study. Blood. (2021) 137(23):3284–90. 10.1182/blood.2020010231

25.

Kent BD Mitchell PD McNicholas WT . Hypoxemia in patients with COPD: cause, effects, and disease progression. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. (2011) 6:199–208. 10.2147/COPD.S10611

26.

Kim H Houck K Neuffer S Dong JF . Red blood cells are critical for hemostasis and thrombosis. Semin Thromb Hemost. (2025) 3081. 10.1055/a-2640-3081

27.

Shiqing W Shengzhong M Cheng Z Guangqing C Chunzheng G . Efficacy of low molecular weight heparin in spinal trauma patients after part concentrated screw surgery and its influence on blood parameters and the incidence of deep venous thrombosis. Med Hypotheses. (2019) 132:109330. 10.1016/j.mehy.2019.109330

28.

Chen Q Deeb RS Ma Y Staudt MR Crystal RG Gross SS . Serum metabolite biomarkers discriminate healthy smokers from COPD smokers. PLoS One. (2015) 10(12):e0143937. 10.1371/journal.pone.0143937

29.

Olivas-Martinez A Corona-Rodarte E Nuñez-Zuno A Barrales-Benítez O Oca DM Mora JD et al Causes of erythrocytosis and its impact as a risk factor for thrombosis according to etiology: experience in a referral center in Mexico city. Blood Res. (2021) 56(3):166–74. 10.5045/br.2021.2021111

30.

Kamstrup P Sivapalan P Rønn C Rastoder E Modin D Kristensen AK et al Fibrin degradation products and survival in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a protocolized prospective observational study. Respir Res. (2023) 24(1):172. 10.1186/s12931-023-02472-9

31.

Summers BD Kim K Clement CC Khan Z Thangaswamy S McCright J et al Lung lymphatic thrombosis and dysfunction caused by cigarette smoke exposure precedes emphysema in mice. Sci Rep. (2022) 12(1):5012. 10.1038/s41598-022-08617-y

32.

Karnati S Seimetz M Kleefeldt F Sonawane A Madhusudhan T Bachhuka A et al Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and the cardiovascular system: vascular repair and regeneration as a therapeutic target. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2021) 8:649512. 10.3389/fcvm.2021.649512

33.

Tran TTV Jeong Y Kim S Yeom JE Lee J Lee W et al PRMT1 ablation in endothelial cells causes endothelial dysfunction and aggravates COPD attributable to dysregulated NF-κB signaling. Adv Sci (Weinh). (2025) 12(19):e2411514. 10.1002/advs.202411514

34.

Oh ES Lee JW Song YN Kim MO Lee RW Kang MJ et al Tangeretin inhibits airway inflammatory responses by reducing early growth response 1 (EGR1) expression in mice exposed to cigarette smoke and lipopolysaccharide. Heliyon. (2024) 10(21):e39797. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e39797

35.

Deng H Zhu S Yu F Song X Jin X Ding X . Analysis of predictive value of cellular inflammatory factors and T cell subsets for disease recurrence and prognosis in patients with acute exacerbations of COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. (2024) 19:2361–9. 10.2147/COPD.S490152

36.

Chuchalin AG Tseimakh IY Momot AR Mamaev AN Karbyshev IA Strozenko LA . Thrombogenic risk factors in patients with exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Klin Med (Mosk). (2015) 93(12):18–23.

37.

Chaurasia SN Kushwaha G Kulkarni PP Mallick RL Latheef NA Mishra JK et al Platelet HIF-2α promotes thrombogenicity through PAI-1 synthesis and extracellular vesicle release. Haematologica. (2019) 104(12):2482–92. 10.3324/haematol.2019.217463

38.

Deng R Ma X Zhang H Chen J Liu M Chen L et al Role of HIF-1α in hypercoagulable state of COPD in rats. Arch Biochem Biophys. (2024) 753:109903. 10.1016/j.abb.2024.109903

39.

Hu X Li X Xu H Zheng W Wang J Wang W et al Development of risk prediction model for muscular calf vein thrombosis with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Gen Med. (2022) 15:6549–60. 10.2147/IJGM.S374777

40.

Gregson J Kaptoge S Bolton T Pennells L Willeit P Burgess S et al Cardiovascular risk factors associated with venous thromboembolism. JAMA Cardiol. (2019) 4(2):163–73. 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.4537

41.

Jiao Q Peng C Cao B Chen J Wang S Wang C et al Prediction model for postoperative acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease in patients with renal cell carcinoma and venous tumor thrombus. World J Urol. (2025) 43(1):391. 10.1007/s00345-025-05750-x

42.

Lv B Wang H Zhang Z Li W . Distribution characteristics of perioperative deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and risk factors of postoperative DVT exacerbation in patients with thoracolumbar fractures caused by high-energy injuries. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. (2024) 50(4):1481–7. 10.1007/s00068-024-02468-0

Summary

Keywords

acute exacerbation, calf circumference, calf muscular vein thrombosis, chronic obstructive pulmonarydisease, D-dimer, RBC, risk factors

Citation

Li X, Xu S, Wang X, Liu Y, Zeng C, Hu Y and Wang R (2026) Analysis of risk factors for calf muscular vein thrombosis in elderly patients with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 13:1742275. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2026.1742275

Received

10 November 2025

Revised

28 December 2025

Accepted

09 January 2026

Published

30 January 2026

Volume

13 - 2026

Edited by

Nicola Mumoli, ASST Valle Olona, Italy

Reviewed by

Hadeer Ahmed Elshahaat, Zagazig University, Egypt

Derya Doğan, Ankara Etlik City Hospital, Türkiye

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Li, Xu, Wang, Liu, Zeng, Hu and Wang.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Rongli Wang sclzwrl2015@163.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.