Abstract

Coronary artery spasm (CAS) is a major form of coronary vasomotor dysfunction within ischemia with non-obstructive coronary arteries (INOCA). Despite ethnic and geographic variation in prevalence, CAS is underrecognized because confirmation often requires pharmacological provocation testing that is unavailable in many centers. Clinically, CAS ranges from silent ischemia and angina to acute myocardial infarction, malignant arrhythmias, heart failure, and sudden cardiac death. Evidence suggests that spasm often occurs at sites with mild atherosclerosis and that its risk profile differs from atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, with more consistent links to smoking, inflammatory burden, and genetic susceptibility, while associations with hypertension and diabetes remain inconsistent. Advances in invasive coronary function testing and recognition of microvascular spasm support an integrated framework involving endothelial dysfunction, vascular smooth muscle hyperreactivity, inflammation–oxidative stress, and autonomic dysregulation. This review synthesizes mechanistic and clinical evidence across these domains, highlights translational opportunities for phenotype-informed risk stratification and precision management, and outlines key research priorities to improve CAS care.

1 Introduction

Coronary artery spasm (CAS) is a major form of coronary vasomotor dysfunction and a key endotype within ischemia with non-obstructive coronary arteries (INOCA). Although prevalence varies across ethnic and geographic populations, CAS remains underrecognized because the diagnosis often relies on pharmacological provocation testing that is not routinely performed in many centers. Clinically, CAS ranges from silent myocardial ischemia and angina to acute myocardial infarction, life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias, heart failure, and sudden cardiac death (1).

Early pathological and intravascular imaging studies suggest that CAS frequently occurs at sites with subclinical or mild atherosclerosis, indicating a functional–structural interplay between vasomotor instability and atherosclerotic remodeling (2). Observational comparisons further indicate that the risk factor profile of CAS differs from that of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD): associations with hypertension and diabetes are inconsistent or weak, whereas smoking, inflammatory burden, and genetic susceptibility show more reproducible links and stronger mechanistic plausibility (3, 4).

In parallel with mechanistic heterogeneity, CAS also exhibits substantial clinical phenotype heterogeneity. CAS can present across distinct ischemic phenotypes, including angina with non-obstructive coronary arteries (ANOCA) and myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries (MINOCA). Emerging outcome data suggest worse prognosis in CAS-related MINOCA than in CAS presenting as ANOCA (5), underscoring the need for phenotype-informed risk stratification and management. These observations align with recent calls for precision approaches in vasomotor disorders (6), emphasizing that CAS should not be viewed as a uniform clinical entity.

Systematic synthesis of the risk factors and pathobiological pathways underlying CAS is essential for advancing precision prevention, individualized diagnosis, and targeted therapeutic strategies. To improve interpretability and avoid overstatement, we apply a structured evidence framework throughout this review. We first summarize the pathophysiological mechanisms of CAS, then integrate its risk factor landscape, and finally discuss translational implications and future research priorities.

2 Methodological approach of this review

To enhance interpretability and avoid overstatement, we apply a structured evidence framework throughout this review. We distinguish observational clinical studies (cohort, case–control, registry, and case-series data), mechanistic and experimental investigations (cellular, animal, and human physiological studies), and interventional clinical evidence (randomized or non-randomized therapeutic studies). We describe observational findings as associations, mechanistic studies are framed as biological plausibility, and causal language is reserved for interventional evidence or guideline-endorsed recommendations. Where applicable, guideline statements are reported using Class of Recommendation (COR) and Level of Evidence (LOE).

3 Microvascular spasm: diagnostic limitations and the epicardial–microvascular continuum

Microvascular spasm is increasingly recognized in vasomotor dysfunction, yet its diagnosis is less straightforward than epicardial spasm because it lacks a direct angiographic correlate. Current definitions rely on acetylcholine-provoked ischemic symptoms and/or ischemic ECG changes without angiographic epicardial constriction (consensus criteria) (7, 8). As a result, diagnostic classification can be sensitive to protocol differences (e.g., acetylcholine dosing), interpretive thresholds, and test–retest/inter-operator variability in symptom and ECG assessment, motivating ongoing standardization of invasive testing (9, 10). Mechanistic and treatment data for microvascular spasm remain largely derived from small physiological or observational studies, whereas epicardial spasm is supported by larger provocation-tested cohorts and more extensive clinical evidence (8, 11, 12).

Emerging invasive data and contemporary syntheses suggest that epicardial and microvascular spasm often overlap and may represent a continuum of coronary vasomotor dysregulation driven by shared upstream pathways [e.g., endothelial dysfunction, Rho-kinase (ROCK) signaling, autonomic imbalance, inflammation] (13, 14). This framing helps interpret heterogeneous results and prevents overgeneralization of therapies across distinct spasm endotypes (10, 13, 14).

CAS can present as ANOCA or MINOCA, and this distinction has pragmatic implications for risk stratification and follow-up. In ANOCA, CAS is often managed as a recurrent symptom disorder, with emphasis on trigger identification, optimization of vasodilator therapy, and relapse prevention, while follow-up is largely guided by symptom control and functional limitation. In MINOCA, spasm-positive testing occurs within an acute coronary syndrome phenotype, where short-to-intermediate event risk and recurrent ischemic injury become more central; closer surveillance and a lower threshold for escalation of preventive strategies may therefore be appropriate (5). Because MINOCA is mechanistically heterogeneous, a spasm finding should be interpreted alongside evaluation for competing or concomitant mechanisms (e.g., plaque disruption or thromboembolism) where clinically feasible, rather than treated as a sole explanation. This phenotype-informed framing aligns with emerging precision approaches in vasomotor disorders (6).

4 Pathophysiological mechanisms: the central pathobiological network—an “Amplification Loop” linking endothelial dysfunction to smooth muscle hyperreactivity

CAS is best understood as a dynamic, self-reinforcing network rather than a linear sequence of events (Figure 1). This network is anchored by endothelial dysfunction and vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) hyperreactivity and is further shaped by inflammation–oxidative stress coupling, autonomic dysregulation, and genetic susceptibility. Perturbation at any node may propagate across the system and lower the threshold for spasm.

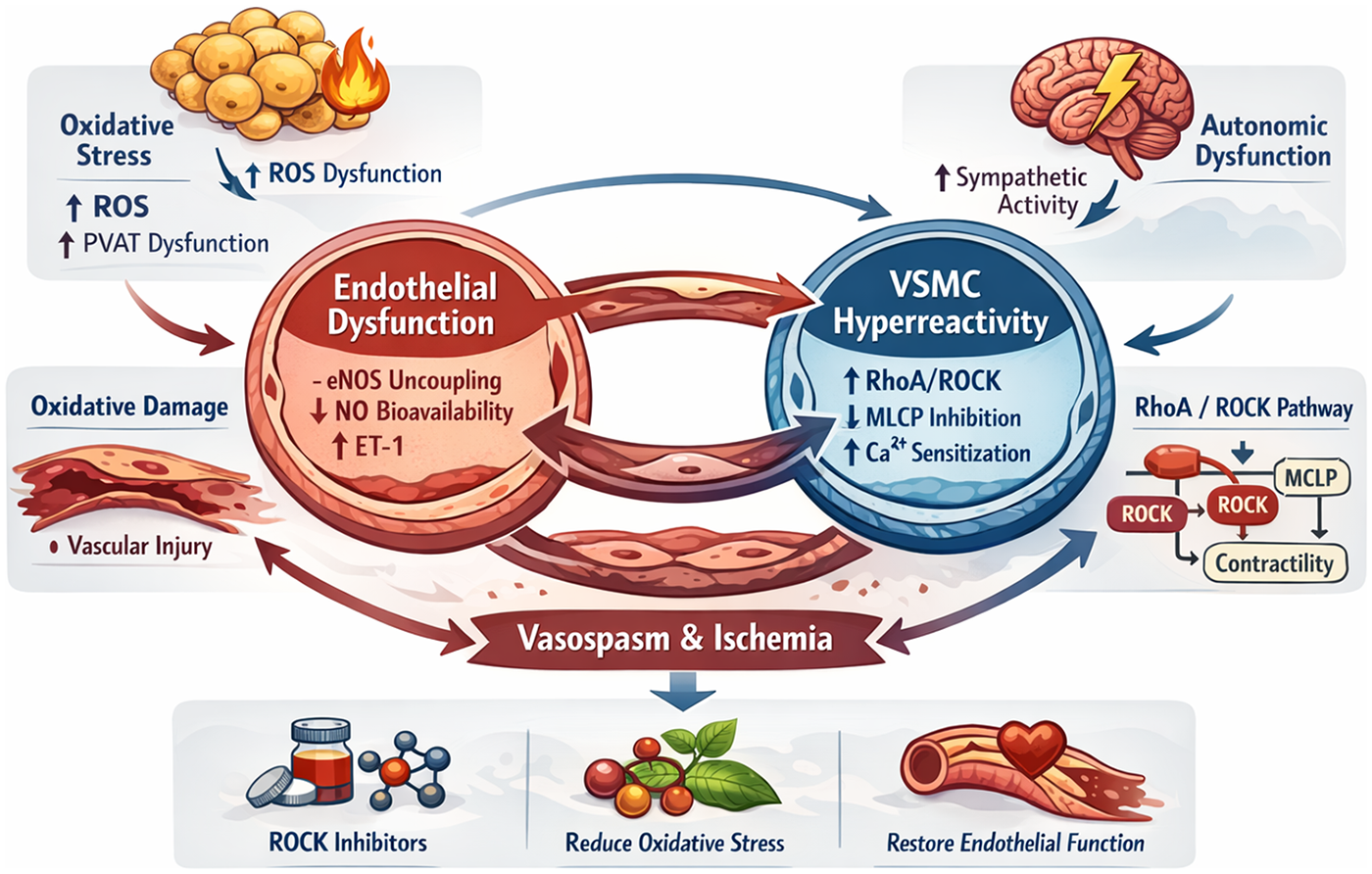

Figure 1

Pathological amplification loop in CAS. This figure illustrates the interconnected molecular and physiological processes that form a self-reinforcing pathological amplification loop in CAS. The loop is centered on endothelial dysfunction and vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) hyperreactivity, integrating inflammatory, oxidative, autonomic, and genetic mechanisms. Endothelial injury characterized by eNOS uncoupling, reduced nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability, and increased endothelin-1 (ET-1) expression initiates vasomotor instability. Inflammatory activation and oxidative stress promote perivascular adipose tissue (PVAT) dysfunction, excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, and propagation of vascular injury. Activation of the RhoA/ROCK signaling cascade enhances VSMC contractility through myosin light chain phosphatase (MLCP) inhibition and calcium sensitization, while autonomic dysregulation provides physiological triggers for spasm onset. Sustained vasospasm induces ischemia, which further aggravates endothelial injury and oxidative stress, thereby maintaining the vicious cycle. This integrated network highlights potential therapeutic targets, including ROCK inhibition, oxidative stress reduction, and restoration of endothelial function, which may disrupt the amplification loop and prevent recurrent spasm. eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; ROS, reactive oxygen species; ROCK, Rho-associated coiled-coil containing protein kinase; PVAT, perivascular adipose tissue; VSMC, vascular smooth muscle cell; ET-1, endothelin-1; MLCP, myosin light chain phosphatase; NO, nitric oxide.

4.1 Dual core pathways: coordinated activation of endothelial dysfunction and VSMCs hyperreactivity

Endothelial dysfunction is a core component of CAS pathophysiology, driven by reduced nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability and an imbalance between vasodilator and vasoconstrictor influences. Reduced endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) activity and tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) can promote eNOS uncoupling, diminishing NO production and increasing superoxide generation. In parallel, elevated vasoconstrictors such as endothelin-1 (ET-1), serotonin, and histamine may further bias vascular tone toward constriction (15).

VSMCs hyperreactivity serves as a major downstream effector of CAS. RhoA/ROCK signaling is strongly implicated, increasing Ca²+ sensitization by inhibiting myosin light-chain phosphatase (MLCP) and thereby facilitating myosin light-chain phosphorylation and sustained contraction. Impaired KATP channel function and increased T-type calcium channel activity may further contribute to hyperreactivity in experimental and clinical physiological studies (16). Together, endothelial dysfunction and VSMCs hyperreactivity create a permissive substrate for coronary spasm.

4.2 Central amplifier: the inflammation–oxidative stress– perivascular adipose tissue (PVAT) axis

Inflammatory activation can bridge endothelial dysfunction and VSMCs hyperreactivity. Inflammatory mediators such as high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) have been associated with endothelial injury, ROS generation, and RhoA/ROCK activation in mechanistic and translational studies (17). Oxidative stress can further deplete NO bioavailability, promote eNOS uncoupling, and facilitate oxidation of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) to oxidized LDL (ox-LDL), thereby sustaining an inflammation–oxidative stress feedback loop that may exacerbate endothelial dysfunction and vascular remodeling (18).

Perivascular Adipose Tissue (PVAT) has also emerged as an active paracrine organ that may modulate vascular homeostasis. Under physiological conditions, PVAT exerts anti-contractile effects through adiponectin-related signaling and anti-inflammatory mediators (19). In obesity and related metabolic states, PVAT may shift toward a pro-contractile phenotype, with increased release of mediators such as chemerin, endothelin-1, TNF-α, and oxidative enzymes, alongside reduced adiponectin. PVAT-derived chemerin has been linked to enhanced VSMCs contractility via RhoA/ROCK signaling and to oxidative stress–related endothelial dysfunction (20), whereas reduced adiponectin may weaken vasodilatory and anti-proliferative buffering (21). This shift may contribute to a local milieu favoring vasoconstriction and impaired endothelial reserve (19, 22).

Maging and histopathological studies further suggest associations between PVAT phenotype and vascular reactivity. Quantitative coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) analyses report that the PVAT attenuation index correlates with the incidence and severity of vasospasm (23), suggesting that PVAT may act as a metabolic–inflammatory intermediary linking systemic status to local vasomotor instabilit (22).

4.3 Triggering regulatory axis: bidirectional modulation by the autonomic nervous system and circadian rhythmicity

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) is implicated in CAS, with sympathetic overactivity contributing to coronary spasm. Sympathetic activation via norepinephrine stimulates α-adrenergic receptors on VSMCs, increases intracellular Ca²+, and activates RhoA/ROCK signaling, thereby enhancing VSMCs contractility (24, 25).

Under physiological conditions, parasympathetic activation via acetylcholine (ACh) induces endothelium-dependent vasodilation through NO release. In the setting of endothelial dysfunction, however, ACh may paradoxically evoke direct smooth muscle constriction and precipitate spasm. Seminal clinical investigations have shown that intracoronary ACh infusion can reliably provoke spasm in patients with variant angina—a response abolished by atropine—supporting a pathological shift of parasympathetic signaling from vasodilatory to vasoconstrictive dominance (25, 26).

Evidence from ischemic heart disease suggests that vagus nerve stimulation (VNS), via invasive or transcutaneous approaches, may rebalance autonomic tone and modulate inflammatory signaling; however, its efficacy and safety for CAS remain unproven and should be framed as a hypothesis requiring CAS-specific clinical outcome studies (27).

Clinical autonomic monitoring studies have described dynamic pre-spasm shifts. Heart rate variability analyses indicate that, within minutes preceding spontaneous CAS episodes, the high-frequency (HF) component decreases while the low-frequency/high-frequency (LF/HF) ratio increases, a pattern consistent with transient sympathetic surges accompanied by vagal withdrawal (28). Microneurography further supports the presence of heightened sympathetic activity in patients with vasospastic angina, suggesting that sympathetic predominance may represent a chronic predisposing state rather than a purely episodic phenomenon (29).

Interventional pharmacological data provide clinical support for ROCK involvement in provoked coronary hyperreactivity. In small clinical studies, the ROCK inhibitor fasudil attenuated acetylcholine-induced coronary constriction and was accompanied by improvement in ischemic findings, consistent with ROCK acting as a downstream mediator of hypercontractile responses in susceptible vessels (30). Taken together, available data suggest that autonomic perturbations, endothelial dysfunction, and VSMCs hypercontractility interact to lower the threshold for CAS initiation and recurrence.

4.4 Amplification via feedback: spasm–induced ischemia as a driver of endothelial injury and dysfunctional vicious cycle

Coronary spasm-induced ischemia may further aggravate endothelial dysfunction and sustain a vicious cycle of recurrent spasm. Preclinical studies and clinical observational data support several interrelated pathways:

- (a)

Excessive ROS generation. Ischemia–reperfusion injury increases ROS levels and promotes endothelial damage, further depleting NO and worsening endothelial dysfunction (31).

- (b)

Inflammatory cytokine activation. Ischemic insult can activate pro-inflammatory mediators such as TNF-α and IL-6, which may impair endothelial function and augment VSMCs contractility (32).

- (c)

Suppression of endothelial repair capacity. Ischemia may reduce endothelial progenitor cell (EPC) mobilization and accelerate endothelial apoptosis, impairing repair capacity (33).

Together, these processes can lower the threshold for recurrent coronary spasm by reinforcing endothelial injury, oxidative stress, and inflammation.

4.5 Genetic susceptibility: core molecular loci and pathophysiological mechanisms

Genetic factors contribute to interindividual variability in CAS susceptibility, with reported loci clustering in pathways that regulate NO bioavailability, oxidative stress handling, and vasoconstrictor signaling (genome-wide association studies and candidate-gene analyses). The ALDH2*2 (rs671) missense variant encodes a low-activity aldehyde dehydrogenase, which can increase reactive aldehyde burden and oxidative stress, thereby favoring NO inactivation and vasomotor hyperreactivity (34). This allele is common in East Asian populations but rare in most European populations, a distribution that may partially contribute to ethnic differences in CAS susceptibility (34). Observational studies further suggest gene–environment interplay, with smoking and alcohol exposure amplifying aldehyde-related oxidative stress and associating with higher spasm propensity among carriers (35).

Beyond ALDH2, the eNOS Glu298Asp (rs1799983) polymorphism has been linked to reduced NO signaling and higher vasospasm risk in case–control and cohort studies (36, 37). In East Asian cohorts, RNF213 p.R4810K has been associated with endothelial and smooth muscle stress phenotypes and enrichment among CAS patients, with observational data linking it to adverse ischemic outcomes (38). In some non-Asian populations, EDN1 Lys198Asn (rs5370) has been associated with diffuse epicardial spasm, potentially reflecting enhanced endothelin-1 signaling (39).

Overall, these findings support a genetic contribution to CAS susceptibility, likely through impaired aldehyde detoxification, oxidative stress, disrupted NO signaling, and augmented vasoconstrictor responses.

4.6 Central signaling hub: the multilayered regulatory network of ROCK

As summarized in Figure 2, ROCK can function as a convergent downstream pathway through which diverse upstream triggers translate into enhanced coronary contractility. Experimental and translational studies implicate RhoA/ROCK activation in settings including nicotine exposure, oxidized LDL/lectin-like oxidized LDL receptor-1 (LOX-1) signaling, sympathetic GPCR stimulation, and PVAT-derived adipokines such as chemerin acting via chemerin receptor (CMKLR1) on VSMCs. Once activated, ROCK promotes spasm mainly by increasing Ca²+ sensitivity via MLCP inhibition, by impairing endothelial NO signaling through eNOS suppression, and by facilitating a pro-inflammatory milieu that further augments contractile responsiveness. These observations support ROCK as a mechanistically relevant effector and a promising therapeutic target under active investigation in CAS.

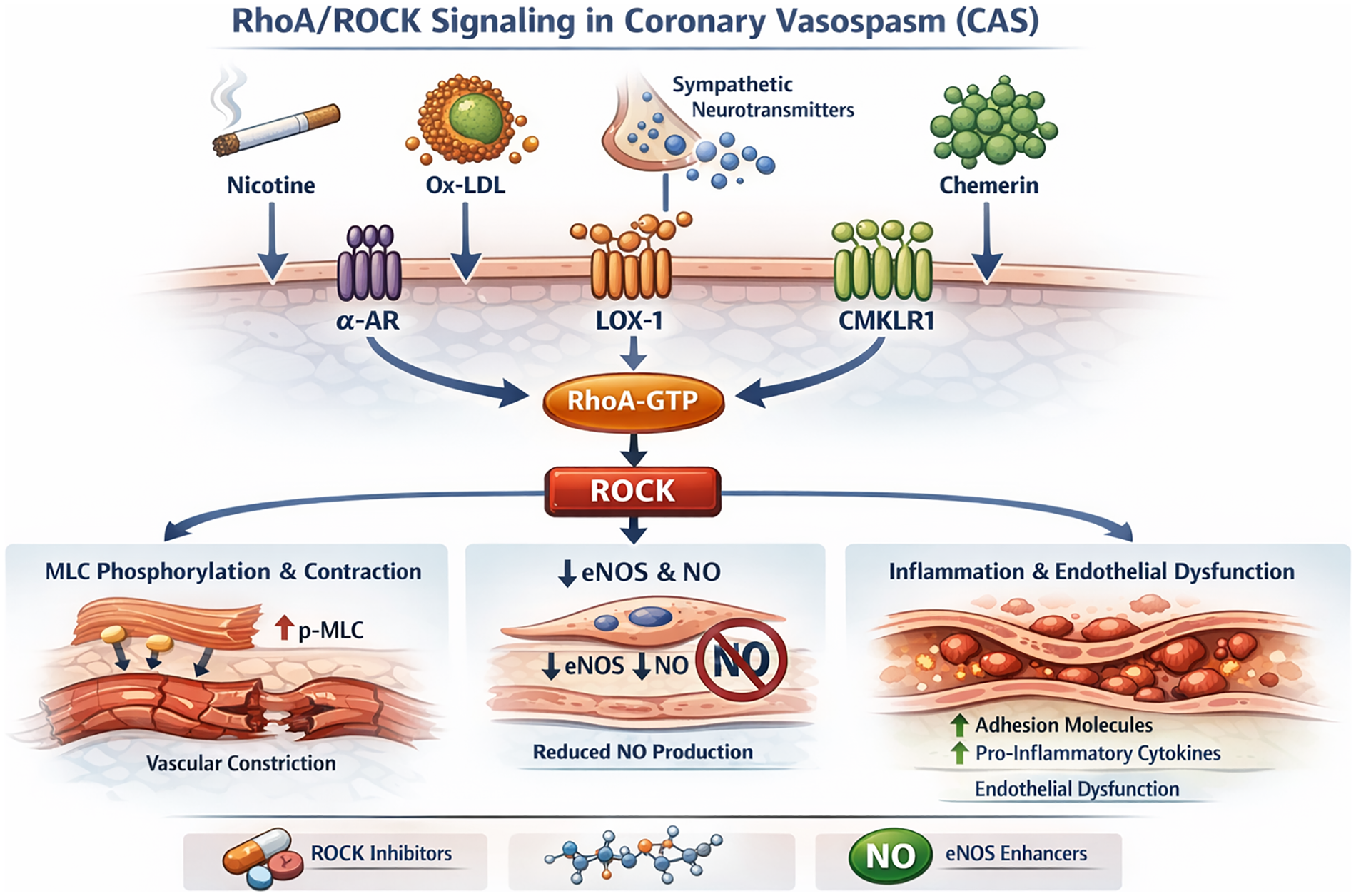

Figure 2

Multidimensional regulatory network of the ROCK signaling pathway in CAS. This schematic depicts the major upstream activators and downstream effectors of the RhoA/ROCK signaling pathway that mediate vascular hypercontractility in CAS. Pathological stimuli, including nicotine, oxidized low-density lipoprotein (ox-LDL), sympathetic neurotransmitters, and chemerin, activate the RhoA/ROCK axis through membrane receptors such as the α-adrenergic receptor (α-AR), lectin-like oxidized LDL receptor-1 (LOX-1), and CMKLR1. These signals converge to enhance RhoA-GTP binding and ROCK activation. Activated ROCK promotes coronary vasospasm by inhibiting MLCP activity, resulting in sustained myosin light chain (MLC) phosphorylation and increased vascular smooth muscle contraction. In parallel, ROCK suppresses eNOS activity, reduces NO production, and induces pro-inflammatory cytokines and adhesion molecules that perpetuate endothelial dysfunction. This network illustrates how environmental, metabolic, and neurohumoral stimuli converge on ROCK signaling to drive CAS pathophysiology and identifies potential pharmacological checkpoints for intervention. MLCP, myosin light chain phosphatase; LOX-1, lectin-like oxidized LDL receptor-1; CMKLR1, chemerin receptor; α-AR, α-adrenergic receptor; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; MLC, myosin light chain; ROCK, Rho-associated coiled-coil containing protein kinase.

5 Risk factor landscape

To facilitate critical appraisal, Table 1 summarizes major CAS risk factors, proposed mechanisms, and a structured indication of evidentiary strength (observational, mechanistic, or interventional where available). Ethnic distributions and risk associations of CAS-related genetic polymorphisms are summarized in Table 2.

Table 1

| Risk factor category | Specific factor | Core mechanism | Epidemiological evidence | Evidence level | Clinical recommendation | Recommendation strength/notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modifiable Lifestyle Factors | Smoking | Smoking induces endothelial dysfunction, increases oxidative stress, and activates the RhoA/ROCK signaling pathway, thereby enhancing vascular smooth muscle contractility. | Meta-analysis (n = 9,376): smoking increases MACE risk (RR 1.97, 95% CI: 1.35–2.87) (46); Cross-sectional study (n = 275): CAS risk (OR 4.20, 95% CI: 2.93–5.34) (40); Cohort study: stronger association in young/middle-aged STEMI patients (42). | High (observational + guideline-endorsed risk factor) | Complete smoking cessation; integrate into comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation | Guideline-recommended smoking cessation for INOCA risk management (Class I, LOE A) (92, 131) |

| Modifiable Lifestyle Factors | Dyslipidemia/Atherosclerotic burden | ox-LDL–related endothelial injury, inflammation, ROCK activation, increased VSMCs contractile sensitivity | Cross-sectional study (n = 275): CAS risk (OR 2.30, 95% CI: 1.51–3.44) (40); Retrospective cohort (n = 80): elevated Lp(a) independently associated with higher spasm activity (48). | Moderate (observational; heterogeneous) | Manage lipids per general dyslipidemia guidelines; intensify LDL-C lowering in high/very-high CV risk | ESC/EAS LDL-C targets (<1.8 mmol/L for high risk; <1.4 mmol/L for very-high risk) rather than CAS-specific targets (130) |

| Environmental/Drug Factors | Airborne particulate matter (PM2.5/PM10) | Systemic inflammation, endothelin-1/ROCK activation, endothelial dysfunction | Observational study (n = 287): long-term PM2.5/PM10 exposure independently associated with CAS in patients with myocardial ischemia without obstructive CAD (NOCAD); stronger association in epicardial spasm and MINOCA (117). | Low–Moderate (observational) | Exposure reduction strategies (avoid high-PM days; respirator masks for high-risk) | Pragmatic risk reduction; not CAS-specific guideline class—state as preventive advice based on observational evidence |

| Environmental/Drug Factors | Vasoconstrictive drugs (e.g., cocaine; nonselective β-blockers; calcineurin inhibitors) | α-adrenergic dominance (cocaine), unopposed α-tone (nonselective β-blockers), endothelial NO impairment (tacrolimus) | Case report: local anesthetic cocaine induced severe CAS (61); Experimental model: cocaine increased coronary vascular resistance six-fold (132); propranolol accentuated cold–induced vasoconstriction (62); atenolol showed no significant CAS increase (133). | Low (case-based/experimental) | Avoid cocaine and triggers; avoid nonselective β-blockers in suspected/known VSA; monitor high-risk exposures | JCS guidance notes concern β-blockers may exacerbate spasm; use caution in high-risk CAS contexts (92) |

| Anatomical/Comorbid Conditions | MB | Coronary flow turbulence and vessel compression contribute to endothelial dysfunction and abnormal vasomotor regulation. | Cohort (n = 310): MB independently predicted MINOCA (OR 2.39, 95% CI: 1.49–3.82); association strongest in ACh-positive cases (67). | Moderate (observational) | Symptom-guided management; consider β1-selective blockers for MB-related exertional symptoms | Important nuance: β-blockers can worsen VSA; if CAS coexists, prioritize CCBs/nitrates and individualizeβ1-selective use |

| Anatomical/Comorbid Conditions | OSA | Intermittent hypoxia leads to sympathetic activation, oxidative stress, and endothelial dysfunction. | Case–control (n = 62): moderate–severe OSA was associated with a higher odds of CAS (OR 9.61, 95% CI: 2.11–43.78) (122); | Low for CAS-specific; High for CV risk | Screen suspected OSA; treat per sleep medicine standards (CPAP when indicated) | CPAP improves overall CV risk and endothelial function, CAS-specific outcomes remain unproven |

| Anatomical/Comorbid Conditions | Thyrotoxicosis | Excess thyroid hormone increases myocardial oxygen demand, reduces coronary vasodilator reserve, and heightens catecholamine sensitivity. | Retrospective cohort (n = 1,239): hyperthyroidism increases CAS risk 3.27–fold (134); symptoms resolve after thyroid normalization (135). | Low–Moderate (observational) | Prompt thyroid normalization; avoid triggers during thyrotoxic phase | General medical management; not CAS-specific |

| Non-Modifiable Factors | Age | Endothelial senescence, oxidative stress, reduced NO bioavailability | Retrospective observational study (n = 3,155): patients undergoing ACh provocation, the prevalence of CAS increased with age (47.3% for <45 years; 58.3% for 45–54 years; 62.6% for 55–64 years; 61.5% for ≥65 years; P < 0.001). Multivariate analysis identified old age as an independent predictor of ACh–induced CAS (adjusted OR 2.60, 95% CI: 2.02–3.24) (82); endothelial dysfunction incidence rises sharply ≥65 years (82, 136). | High (large observational cohorts) | Consider provocation testing based on symptoms/INOCA context rather than age alone | JCS provides indications for provocation testing; avoid presenting age as stand-alone indication (use symptom-driven testing) (92) |

| Non-Modifiable Factors | Sex | Men: more epicardial spasm (often higher smoking exposure); women: microvascular spasm enriched, post-menopause risk | Gender–stratified analysis (n = 104): Korean cohort—majority male with higher smoking/alcohol rates; female patients younger and less exposed (137). | Moderate (observational) | Phenotype-specific evaluation (epicardial vs. microvascular) and risk factor control | Highlight diagnostic heterogeneity |

| Genetic Variants | ALDH2*2, eNOS Glu298Asp, RNF213, etc. | Aldehyde detox/NO signaling/vascular cell survival pathways | Genomic studies identified ALDH2*2 frequency as markedly higher in East Asians (∼30%–40%) (138); The eNOS Glu298Asp polymorphism conferred approximately a 2.83–fold increase in CAS risk (139); RNF213 p.R4810K variant was associated with a 2.34–fold increased risk (38). | Moderate–High (genetic association) | Not routine screening; consider in strong family history/sudden death or refractory phenotypes | Present as risk modifiers, not direct clinical test recommendations unless local practice supports |

| Controversial/Inconsistent Factors | Alcohol | In ALDH2*2 carriers: acetaldehyde accumulation, prostanoid imbalance; autonomic effects | Korean cohort (n = 5,491): heavy drinking increased CAS risk (HR 1.54, 95% CI: 1.17–2.01) (76); experimental study (n = 16): spasm triggered hours post–drinking when plasma ethanol levels approach zero. | Low–Moderate (observational; confounded) | Avoid heavy drinking; consider stricter avoidance in ALDH2*2 carriers | Lifestyle advice; causality uncertain |

| Controversial Factors | Hyperuricemia | eNOS inhibition, endothelin/ROCK activation | Cohort (n = 5,324): no link with overall CAS incidence but multivessel spasm risk was increased by approximately 1.7–fold (99); multivariate analysis confirms uric acid as independent CAS marker (100). | Low–Moderate (observational) | No routine urate-lowering solely for CAS; manage per gout/CKD indications | Marker hypothesis; evidence inconsistent |

| Controversial Factors | Hypertension | Vascular remodeling; endothelial dysfunction | Cohort (n = 938): uncontrolled hypertension associated with 30% lower ACh positivity (3). | Low–Moderate (heterogeneous observational) | Standard blood pressure control per guidelines | No CAS-specific recommendation |

| Controversial Factors | Glucose metabolism disorders/Diabetes | Fibrosis/endothelial dysfunction; treatment confounding | Cohort (n = 986): no significant association between diabetes and CAS (87); insulin resistance prevalent in microvascular dysfunction (140). | Low–Moderate (heterogeneous observational) | Standard glycemic control; assess coronary microvascular dysfunction (CMD) when clinically suspected. | Relevance mainly for microvascular dysfunction |

Major risk factors for CAS and corresponding evidence strength.

Footnote (Evidence tier): High/Moderate/Low reflects overall evidence strength for CAS/VSA relevance: High = consistent multi-cohort/registry support and/or interventional or guideline-backed data; Moderate = heterogeneous observational evidence and/or mechanistic plausibility without outcome validation; Low = small/single-center studies, case series/reports, or hypothesis-generating data with limited replication. Associations are described non-causally unless explicitly supported.

ACh, acetylcholine; CAS, coronary artery spasm; CCB, calcium channel blocker; CI, confidence interval; CMD, coronary microvascular dysfunction; CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; CV, cardiovascular; hs-CRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; Lp(a), lipoprotein(a); MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; MB, myocardial bridging; MINOCA, myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries; NOCAD, no obstructive coronary artery disease; NO, nitric oxide; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea; OR, odds ratio; ox-LDL, oxidized low-density lipoprotein; PM₂.₅/PM₁₀, particulate matter ≤ 2.5/10 μm; ROCK, Rho-kinase; RR, risk ratio; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; VSA, vasospastic angina; VSMCs, vascular smooth muscle cells.

Table 2

| Gene variant | Ethnic distribution | Core mechanism | CAS risk | Evidence type | Key references |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALDH2*2 | Predominantly East Asian; high carrier frequency in East Asia; impacts alcohol flushing phenotype | Reduced aldehyde dehydrogenase-2 enzymatic activity leads to accumulation of reactive aldehydes, increased oxidative stress, and endothelial dysfunction. | Reported OR 3.00 (95% CI: 1.90–4.80) | Candidate-gene case–control association | JCS VSA guideline (92); Mizuno et al. (141); Rwere et al. (34) |

| eNOS Glu298Asp | Worldwide distribution. | Reduced endothelial nitric oxide synthase stability and activity, leading to decreased NO bioavailability. | Reported OR 2.83 (95% CI: 1.25–6.41) | Candidate-gene case–control association | Chang et al. (139) |

| RNF213 p.R4810K | Predominantly East Asian; low carrier rate. | Variant-associated endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells dysfunction with increased susceptibility to apoptosis. | Reported OR 2.34 (95% CI: 1.99–2.74) | Population-specific variant association (East Asian cohorts) | Hikino et al. (38); Cao et al. (142) |

| EDN1 rs5370 | Multi-ethnic distribution. | Enhanced endothelin-1 gene expression and vasoconstrictor signaling. | Reported OR 1.75 (P = 0.009; 95% CI: not reported) | Candidate-gene case–control association | Lee et al. (143) |

Ethnic differences and risk associations of CAS-related genetic polymorphisms.

ALDH2, aldehyde dehydrogenase 2; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; RNF213, ring finger protein 213; EDN1, endothelin–1; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

5.1 Smoking: the most well–defined modifiable risk factor for CAS

Smoking is the most consistently reported modifiable risk factor for CAS. Provocation-tested cohorts, particularly from East Asia, show higher smoking prevalence among CAS patients with dose–response relationships between cumulative exposure and spasm susceptibility (40–42), and smoking is widely regarded as the best-established environmental risk factor (43). Mechanistically, nicotine and combustion-derived oxidants reduce NO bioavailability via oxidative stress, eNOS uncoupling/ADMA-related pathways, and ROCK activation (44–46), and acute exposure may trigger spasm (43). Although CAS-specific cessation trials are lacking, cessation improves vascular function and reduces long-term cardiovascular risk in broader populations (47). it remains a central preventive measure in suspected or confirmed CAS.

5.2 Dyslipidemia: the role of oxidative modification in pathophysiology

Conventional dyslipidemia shows heterogeneous and generally modest associations with CAS (40). In contrast, oxidative lipid pathways—ox-LDL, Lp(a), and dysfunctional HDL—are more consistently linked to endothelial dysfunction and VSMCs hyperreactivity (48, 49). LDL oxidation can promote endothelial injury via NADPH oxidase activation and eNOS uncoupling (50), while ox-LDL can amplify contractile signaling through RhoA-related pathways (51). Statins may improve endothelial function and outcomes in selected VSA/CAS populations (52), but evidence for reducing spasm frequency and the role of Lp(a)-targeted strategies remain limited.

5.3 Inflammatory burden and hs–CRP: a reproducible association best interpreted as a risk marker

Multiple observational studies report associations between elevated hs–CRP and ACh-induced spasm (3, 53, 54), although effect sizes vary and interactions with sex/metabolic status have been described (55). Mechanistic data support plausibility through impaired NO signaling and ROCK-related facilitation of hyperreactivity (56), and PVAT inflammation may further modulate local vasomotor balance (57). Overall, hs–CRP is best interpreted as a risk marker rather than a uniform causal driver.

5.4 Renal-linked biomarkers and systemic vulnerability

In addition to inflammatory markers, renal-linked biomarkers may capture a broader “systemic vulnerability” milieu in which coronary vasomotor dysfunction becomes more likely. Cystatin C has been reported to associate with acetylcholine-provoked CAS in observational cohorts, suggesting that subtle impairment in renal filtration—or the inflammatory, oxidative, and endothelial perturbations that often accompany it—may track with heightened spasm susceptibility (58, 59). Importantly, these data are best interpreted as associative rather than causal: cystatin C integrates multiple upstream processes (renal function, vascular inflammation, and metabolic stress) and therefore remains vulnerable to residual confounding. From a precision-management perspective, its value is less as a standalone discriminator and more as a complementary feature within multimodal risk profiling, helping to contextualize vasomotor testing results and to identify patients whose risk likely reflects a diffuse, multi-organ substrate rather than an isolated coronary phenotype (58, 59).

5.5 Drug/toxin exposure: key clinical medication warnings in CAS

Sympathomimetic exposures (e.g., cocaine) can provoke coronary vasoconstriction via adrenergic stimulation and endothelial dysfunction, contributing to ET-1/NO imbalance and ischemic events (60, 61). Non-selective β-blockers may aggravate vasoconstriction through unopposed α-adrenergic signaling (62), whereas β1-selective blockers appear less likely to worsen vasospasm (63). Immunosuppressive and chemotherapeutic agents (e.g., tacrolimus, 5-fluorouracil) have been linked to reversible vasospasm during exposure (64, 65). Medication review and avoidance of recognized triggers remain pragmatic measures.

5.6 Myocardial bridging: an anatomical substrate associated with spasm susceptibility

Myocardial bridging (MB) is associated with increased spasm susceptibility and contributes to a subset of MINOCA presentations (66, 67). Disturbed shear stress within bridged segments may impair endothelial function (including reduced eNOS expression) and promote local hyperreactivity (68). Provocation testing and intravascular imaging suggest that spasm may localize to or adjacent to bridged segments (67). In MB with unexplained angina or MINOCA, concomitant CAS should be considered, and coronary function testing may be useful where available.

5.7 Alcohol intake: a controversial factor with genetic and dose-specific modulation

The relationship between alcohol intake and CAS is heterogeneous. Early reports described alcohol-induced spasm and experimental work suggested vasoconstrictive thresholds (69, 70). Subsequent observations indicate delayed spasm after intake, implicating indirect mechanisms such as endothelial dysfunction and autonomic dysregulation (71, 72). Proposed pathways include altered prostaglandin balance, impaired cGMP-mediated vasodilation, and magnesium depletion affecting eNOS activity (73–76), although these remain hypothesis-generating. ALDH2*2 carriers may be more susceptible to alcohol-related CAS (77). Individualized counseling is appropriate, particularly in patients reporting alcohol-related episodes (78–81).

5.8 Age: endothelial senescence and cumulative vascular vulnerability

Advancing age is associated with higher CAS detection in provocation-tested cohorts (82). Endothelial senescence, cumulative oxidative stress, and low-grade inflammation may lower the threshold for vasomotor dysregulation (83–85), and remodeling/subclinical atherosclerosis may further reduce endothelial resilience. These data support considering CAS in older patients with unexplained ischemia, while optimal screening strategies remain uncertain (82, 86).

5.9 Glucose metabolism disorders: metabolic dysregulation rather than overt diabetes as a vasomotor modifier

Associations between diabetes and CAS are inconsistent across provocation cohorts (87–89). In contrast, insulin resistance and compensatory hyperinsulinemia may impair NO signaling and microvascular vasodilation, contributing to vasomotor dysregulation even without overt diabetes (88, 90). Follow-up studies also suggest higher incident diabetes in CAS populations (91). Clinically, assessing metabolic status and monitoring for incident diabetes remain appropriate (92, 93).

5.10 Hypertension: paradoxical association with CAS susceptibility

Although hypertension contributes to endothelial dysfunction, its relationship with CAS differs from ASCVD. Several provocation-based studies report neutral or inverse associations between hypertension and ACh-induced spasm (3, 94). Proposed mechanisms include remodeling and altered calcium-handling/ROCK signaling that may reduce acute pharmacologic responsiveness in certain contexts (95–98). Hypertension should be treated for overall cardiovascular risk reduction, while its role as a CAS-specific risk factor should be interpreted cautiously.

5.11 Hyperuricemia: a marker of spasm severity rather than incidence

Studies on serum uric acid show mixed findings, with inconsistent associations with CAS occurrence but reported links with multivessel spasm in some cohorts (99, 100). Mechanistic studies suggest effects on eNOS, oxidative stress, and endothelin/ROCK pathways (101–103), but CAS-specific interventional confirmation is lacking. Hyperuricemia is therefore best viewed as a potential marker of severity rather than a therapeutic target.

5.12 Gender differences and phenotypic heterogeneity

Men more frequently exhibit epicardial spasm, whereas women more often demonstrate microvascular spasm in multicenter observational studies and meta-analyses (104, 105). Estrogen may enhance NO signaling and suppress vasoconstrictor pathways, and post-menopausal changes may contribute to instability (106, 107), although hormone-based interventions remain unproven. Sex-specific interactions with smoking, aging, inflammatory, and metabolic factors have also been reported (54, 108), supporting sex-informed evaluation rather than sex-specific therapy.

5.13 Physiological and psychological stress: autonomic dysregulation as a trigger

Autonomic imbalance is frequently observed in vasospastic angina. Heart-rate variability and Holter studies show short-term sympathetic–parasympathetic shifts preceding spasm episodes (109–111). These data are observational and do not establish causality. Where CAS coexists with structural coronary disease, autonomic dysfunction has been associated with worse prognosis (112). Psychological stress may also contribute: mental stress testing can provoke ischemic changes consistent with vasospasm (113), and cohort studies associate anxiety/depression with higher CAS prevalence (114–116), although CAS-specific randomized trials of stress-reduction interventions are lacking.

5.14 Environmental factors: external triggers of vasomotor instability

Environmental exposures may act as external triggers that destabilize vasomotor tone in predisposed individuals. Higher long-term PM₂.₅/PM₁₀ exposure has been associated (in multivariable models) with ACh-provocation positivity, with PM₂.₅ showing a stronger relationship with epicardial spasm and both pollutants linked to MINOCA presentations (117). Mechanistic data support plausibility through systemic inflammation, oxidative stress, and downstream ROCK activation, promoting vascular hyperreactivity (118). Cold exposure and hyperventilation are recognized triggers; provocation studies report high sensitivity of combined cold-pressor plus hyperventilation protocols for eliciting variant angina–type responses (119). Overall, the evidence supports an “environmental trigger” model, while causal inference remains limited by exposure assessment and residual confounding.

5.15 Ethnicity and genetic susceptibility

Ethnic differences in CAS prevalence are consistently reported, with higher detection rates in East Asian populations than in Western cohorts (104, 120). Genetic studies implicate variants in ALDH2, EDN1, and other vasomotor-related genes as susceptibility loci (39, 77, 121), supporting gene–environment interaction rather than single-gene causation. At present, genetic testing has no established role in routine CAS management.

5.16 Comorbid diseases: systemic vasomotor dysregulation

Several comorbid conditions have been associated with CAS, plausibly reflecting systemic vasomotor vulnerability.

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA): Observational studies report higher acetylcholine-provocation positivity in OSA, and CPAP improves endothelial function (122–124). However, CAS-specific interventional trials are unavailable.

Thyrotoxicosis: Case reports and small series describe reversible coronary spasm resolving after restoration of euthyroidism (125, 126). Evidence remains largely observational.

Migraine and Raynaud's Phenomenon: Both represent vasomotor hyperreactivity phenotypes, and observational studies report higher prevalence among CAS patients (127–129). Shared genetic predisposition has been suggested.

Collectively, these comorbidities are best viewed as markers of systemic vasomotor susceptibility rather than direct causal factors.

6 Summary and future directions

CAS is a multifactorial vasomotor disorder in which endothelial dysfunction and VSMCs hyperreactivity interact with inflammation–oxidative pathways, autonomic imbalance, and genetic susceptibility. While parts of the risk profile overlap with ASCVD (e.g., smoking and dyslipidemia), CAS also has distinct modifiers, including myocardial bridging, PVAT-related dysfunction, and population-specific genetic variants that may shape susceptibility and clinical expression.

7 Key strategies to improve prognosis include

7.1 Risk-factor modification

Smoking cessation remains the most actionable preventive intervention, alongside mitigation of inflammatory burden, avoidance of relevant triggers (including medications and environmental exposures), and optimization of comorbidities such as OSA.

7.2 Phenotype-informed therapy and evidence gaps

Calcium channel blockers remain first-line therapy. For refractory cases, small interventional studies suggest that ROCK inhibition (e.g., fasudil) can attenuate ACh-induced constriction and ischemic changes, including in microvascular spasm phenotypes (30, 130). However, robust CAS-specific outcome trials—particularly phenotype-stratified comparisons between epicardial and microvascular spasm—remain limited. Therefore, phenotype-guided pharmacotherapy should be presented as a rational but still unvalidated strategy that requires prospective confirmation.

7.3 Priorities for future research

-

(1)

Define how major modifiers (e.g., ALDH2*2, tobacco exposure, PM₂.₅) interact within the “amplification loop,” and identify tractable regulatory nodes.

-

(2)

Determine whether multimodal tools (e.g., leukocyte ROCK activity, PVAT attenuation, genetic risk scores, renal-linked biomarkers) improve risk stratification and treatment selection beyond clinical phenotyping alone; cystatin C associations require external validation (58, 59).

-

(3)

Clarify endotype overlap and diagnostic uncertainty across epicardial and microvascular spasm, and establish standardized, reproducible testing thresholds to reduce misclassification and inappropriate therapeutic generalization.

Statements

Author contributions

ZK: Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. RK: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. ZW: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Validation. SZ: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. LY: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. XW: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. XS: Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition. JL: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation 82260058, Guizhou Provincial Health Commission: gzwkj2023-130, Qian Science and Technology Cooperation Support [2020] 4Y231 and Foundation ZK[2024] Key Project 040. There was no role of the funding body in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. The authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI, San Francisco, CA, USA) to assist in language polishing and grammar refinement during manuscript preparation. ChatGPT was also used to generate the pictorial elements in Figure 1 and Figure 2. All content was reviewed and verified by the authors to ensure scientific accuracy and integrity.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Barsukov AV Borisova EV Vasilyeva IA Glukhovskoy DV Kuznetsov MV Saraev GB . Vasosspastic angina: current concepts about pathogenesis, diagnosis, treatment (literature review). Adv Gerontol. (2025) 38(1):36–45.

2.

Saito S Yamagishi M Takayama T Chiku M Koyama J Ito K et al Plaque morphology at coronary sites with focal spasm in variant angina: study using intravascular ultrasound. Circ J. (2003) 67(12):1041–5. 10.1253/circj.67.1041

3.

Morita S Mizuno Y Harada E Nakagawa H Morikawa Y Saito Y et al Differences and interactions between risk factors for coronary spasm and atherosclerosis–smoking, aging, inflammation, and blood pressure. Intern Med. (2014) 53(23):2663–70. 10.2169/internalmedicine.53.2705

4.

Jenkins K Pompei G Ganzorig N Brown S Beltrame J Kunadian V . Vasospastic angina: a review on diagnostic approach and management. Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis. (2024) 18:17539447241230400. 10.1177/17539447241230400

5.

Montone RA Rinaldi R Del Buono MG Gurgoglione F La Vecchia G Russo M et al Safety and prognostic relevance of acetylcholine testing in patients with stable myocardial ischaemia or myocardial infarction and non-obstructive coronary arteries. EuroIntervention. (2022) 18(8):e666–e76. 10.4244/EIJ-D-21-00971

6.

Montone RA Cosentino N Gorla R Biscaglia S La Vecchia G Rinaldi R et al Stratified treatment of myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries: the PROMISE trial. Eur Heart J. (2025):ehaf917. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaf917

7.

Ong P Camici PG Beltrame JF Crea F Shimokawa H Sechtem U et al International standardization of diagnostic criteria for microvascular angina. Int J Cardiol. (2018) 250:16–20. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.08.068

8.

Ong P Athanasiadis A Borgulya G Vokshi I Bastiaenen R Kubik S et al Clinical usefulness, angiographic characteristics, and safety evaluation of intracoronary acetylcholine provocation testing among 921 consecutive white patients with unobstructed coronary arteries. Circulation. (2014) 129(17):1723–30. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.004096

9.

Sueda S Kohno H Ochi T Uraoka T . Overview of the acetylcholine spasm provocation test. Clin Cardiol. (2015) 38(7):430–8. 10.1002/clc.22403

10.

Ong P Athanasiadis A Sechtem U . Intracoronary acetylcholine provocation testing for assessment of coronary vasomotor disorders. J Vis Exp. (2016) (114):54295. 10.3791/54295

11.

Ohba K Sugiyama S Sumida H Nozaki T Matsubara J Matsuzawa Y et al Microvascular coronary artery spasm presents distinctive clinical features with endothelial dysfunction as nonobstructive coronary artery disease. J Am Heart Assoc. (2012) 1(5):e002485. 10.1161/JAHA.112.002485

12.

Sun H Mohri M Shimokawa H Usui M Urakami L Takeshita A . Coronary microvascular spasm causes myocardial ischemia in patients with vasospastic angina. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2002) 39(5):847–51. 10.1016/S0735-1097(02)01690-X

13.

Seitz A Feenstra R Konst RE Martínez Pereyra V Beck S Beijk M et al Acetylcholine rechallenge: a first step toward tailored treatment in patients with coronary artery spasm. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. (2022) 15(1):65–75. 10.1016/j.jcin.2021.10.003

14.

Godo S Takahashi J Shiroto T Yasuda S Shimokawa H . Coronary microvascular spasm: clinical presentation and diagnosis. Eur Cardiol. (2023) 18:e07. 10.15420/ecr.2022.50

15.

Hubert A Seitz A Pereyra VM Bekeredjian R Sechtem U Ong P . Coronary artery spasm: the interplay between endothelial dysfunction and vascular smooth muscle cell hyperreactivity. Eur Cardiol. (2020) 15:e12. 10.15420/ecr.2019.20

16.

Kikuchi Y Yasuda S Aizawa K Tsuburaya R Ito Y Takeda M et al Enhanced rho-kinase activity in circulating neutrophils of patients with vasospastic angina: a possible biomarker for diagnosis and disease activity assessment. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2011) 58(12):1231–7. 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.05.046

17.

Sylvester AL Zhang DX Ran S Zinkevich NS . Inhibiting NADPH oxidases to target vascular and other pathologies: an update on recent experimental and clinical studies. Biomolecules. (2022) 12(6):823. 10.3390/biom12060823

18.

Janaszak-Jasiecka A Płoska A Wierońska JM Dobrucki LW Kalinowski L . Endothelial dysfunction due to eNOS uncoupling: molecular mechanisms as potential therapeutic targets. Cell Mol Biol Lett. (2023) 28(1):21. 10.1186/s11658-023-00423-2

19.

Chang L Garcia-Barrio MT Chen YE . Perivascular adipose tissue regulates vascular function by targeting vascular smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. (2020) 40(5):1094–109. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.120.312464

20.

Schinzari F Montenero R Cardillo C Tesauro M . Chemerin is the adipokine linked with endothelin-dependent vasoconstriction in human obesity. Biomedicines. (2025) 13(9):2131. 10.3390/biomedicines13092131

21.

AlZaim I Hammoud SH Al-Koussa H Ghazi A Eid AH El-Yazbi AF . Adipose tissue immunomodulation: a novel therapeutic approach in cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2020) 7:602088. 10.3389/fcvm.2020.602088

22.

Adachi Y Ueda K Takimoto E . Perivascular adipose tissue in vascular pathologies-a novel therapeutic target for atherosclerotic disease?Front Cardiovasc Med. (2023) 10:1151717. 10.3389/fcvm.2023.1151717

23.

Asada K Saito Y Takaoka H Kitahara H Kobayashi Y . Relation of perivascular adipose tissues on computed tomography to coronary vasospasm. Rev Cardiovasc Med. (2025) 26(2):26327. 10.31083/RCM26327

24.

Nishimiya K Takahashi J Oyama K Matsumoto Y Yasuda S Shimokawa H . Mechanisms of coronary artery spasm. Eur Cardiol. (2023) 18:e39. 10.15420/ecr.2022.55

25.

Seitz A Martínez Pereyra V Sechtem U Ong P . Update on coronary artery spasm 2022—a narrative review. Int J Cardiol. (2022) 359:1–6. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2022.04.011

26.

Yasue H Horio Y Nakamura N Fujii H Imoto N Sonoda R et al Induction of coronary artery spasm by acetylcholine in patients with variant angina: possible role of the parasympathetic nervous system in the pathogenesis of coronary artery spasm. Circulation. (1986) 74(5):955–63. 10.1161/01.CIR.74.5.955

27.

Liu Y Yang H Xiong J Wei Y Yang C Zheng Q et al Brain-heart axis: neurostimulation techniques in ischemic heart disease (review). Int J Mol Med. (2025) 56(4):148. 10.3892/ijmm.2025.5589

28.

Ooie T Takakura T Shiraiwa H Yoshimura A Hara M Saikawa T . Change in heart rate variability preceding ST elevation in a patient with vasospastic angina pectoris. Heart Vessels. (1998) 13(1):40–4. 10.1007/BF02750642

29.

Boudou N Despas F Rothem JV Lairez O Elbaz M Vaccaro A et al Direct evidence of sympathetic hyperactivity in patients with vasospastic angina. Am J Cardiovasc Dis. (2017) 7(3):83–8.

30.

Masumoto A Mohri M Shimokawa H Urakami L Usui M Takeshita A . Suppression of coronary artery spasm by the Rho-kinase inhibitor fasudil in patients with vasospastic angina. Circulation. (2002) 105(13):1545–7. 10.1161/hc1002.105938

31.

Zhang Y Jiang M Wang T . Reactive oxygen species (ROS)-responsive biomaterials for treating myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. (2024) 12:1469393. 10.3389/fbioe.2024.1469393

32.

Li W Liao Y Chen J Kang W Wang X Zhai X et al Ischemia—reperfusion injury: a roadmap to precision therapies. Mol Asp Med. (2025) 104:101382. 10.1016/j.mam.2025.101382

33.

Huang H Huang W . Regulation of endothelial progenitor cell functions in ischemic heart disease: new therapeutic targets for cardiac remodeling and repair. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2022) 9:896782. 10.3389/fcvm.2022.896782

34.

Rwere F White JR Hell RCR Yu X Zeng X McNeil L et al Uncovering newly identified aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 genetic variants that lead to acetaldehyde accumulation after an alcohol challenge. J Transl Med. (2024) 22(1):697. 10.1186/s12967-024-05507-x

35.

Xu L Cui X-T Chen Z-W Shen L-H Gao X-F Yan X-X et al Aldehyde dehydrogenase 2-associated metabolic abnormalities and cardiovascular diseases: current status, underlying mechanisms, and clinical recommendations. Cardiol Plus. (2022) 7(1):12–9. 10.1097/CP9.0000000000000002

36.

Shimasaki Y Yasue H Yoshimura M Nakayama M Kugiyama K Ogawa H et al Association of the missense Glu298Asp variant of the endothelial nitric oxide synthase gene with myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. (1998) 31(7):1506–10. 10.1016/S0735-1097(98)00167-3

37.

Yoshimura M Yasue H Nakayama M Shimasaki Y Sumida H Sugiyama S et al A missense Glu298Asp variant in the endothelial nitric oxide synthase gene is associated with coronary spasm in the Japanese. Hum Genet. (1998) 103(1):65–9. 10.1007/s004390050785

38.

Hikino K Koyama S Ito K Koike Y Koido M Matsumura T et al RNF213 Variants, vasospastic angina, and risk of fatal myocardial infarction. JAMA Cardiol. (2024) 9(8):723–31. 10.1001/jamacardio.2024.1483

39.

Tremmel R Pereyra M Broders V Schaeffeler I Hoffmann E Nöthen P et al Genetic associations of cardiovascular risk genes in European patients with coronary artery spasm. Clin Res Cardiol. (2024) 113(12):1733–44. 10.1007/s00392-024-02446-x

40.

Xiang D Kleber FX . Smoking and hyperlipidemia are important risk factors for coronary artery spasm. Chin Med J. (2003) 116(4):510–3.

41.

Choi BG Rha SW Park T Choi SY Byun JK Shim MS et al Impact of cigarette smoking: a 3-year clinical outcome of vasospastic angina patients. Korean Circ J. (2016) 46(5):632–8. 10.4070/kcj.2016.46.5.632

42.

Kuang Z Lin L Kong R Wang Z Mao X Xiang D . The correlation between cumulative cigarette consumption and infarction-related coronary spasm in patients with ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction across different age groups. Sci Rep. (2025) 15(1):253. 10.1038/s41598-024-84125-5

43.

Higashi Y . Smoking cessation and vascular endothelial function. Hypertens Res. (2023) 46(12):2670–8. 10.1038/s41440-023-01455-z

44.

Li J Liu S Cao G Sun Y Chen W Dong F et al Nicotine induces endothelial dysfunction and promotes atherosclerosis via GTPCH1. J Cell Mol Med. (2018) 22(11):5406–17. 10.1111/jcmm.13812

45.

El-Mahdy MA Ewees MG Eid MS Mahgoup EM Khaleel SA Zweier JL . Electronic cigarette exposure causes vascular endothelial dysfunction due to NADPH oxidase activation and eNOS uncoupling. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. (2022) 322(4):H549–h67. 10.1152/ajpheart.00460.2021

46.

Yang L Wang K Yang J Hu FX . Effects of smoking on Major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with coronary artery spasm: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart Lung Circ. (2024) 33(9):1259–71. 10.1016/j.hlc.2024.02.015

47.

Cho JH Shin SY Kim H Kim M Byeon K Jung M et al Smoking cessation and incident cardiovascular disease. JAMA Netw Open. (2024) 7(11):e2442639. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.42639

48.

Tsuchida K Hori T Tanabe N Makiyama Y Ozawa T Saigawa T et al Relationship between serum lipoprotein(a) concentrations and coronary vasomotion in coronary spastic angina. Circ J. (2005) 69(5):521–5. 10.1253/circj.69.521

49.

Sasaki K Ezaki H Endo Y Kudo D Suenaga Y Ayaori M et al Roles of HDL function and sphingosine-1-phosphate in vasospastic angina. Clin Chim Acta. (2025) 574:120338. 10.1016/j.cca.2025.120338

50.

Jiang H Zhou Y Nabavi SM Sahebkar A Little PJ Xu S et al Mechanisms of oxidized LDL-mediated endothelial dysfunction and its consequences for the development of atherosclerosis. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2022) 9:925923. 10.3389/fcvm.2022.925923

51.

Cai A Zhou Y Li L . Rho-GTPase and atherosclerosis: pleiotropic effects of statins. J Am Heart Assoc. (2015) 4(7):e002113. 10.1161/JAHA.115.002113

52.

Jamialahmadi T Baratzadeh F Reiner Ž Mannarino MR Cardenia V Simental-Mendía LE et al The effects of statin therapy on oxidized LDL and its antibodies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oxid Med Cell Longevity. (2022) 2022:7850659. 10.1155/2022/7850659

53.

Park JY Rha SW Li YJ Chen KY Choi BG Choi SY et al The impact of high sensitivity C-reactive protein level on coronary artery spasm as assessed by intracoronary acetylcholine provocation test. Yonsei Med J. (2013) 54(6):1299–304. 10.3349/ymj.2013.54.6.1299

54.

Hung MY Hsu KH Hung MJ Cheng CW Cherng WJ . Interactions among gender, age, hypertension and C-reactive protein in coronary vasospasm. Eur J Clin Investig. (2010) 40(12):1094–103. 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2010.02360.x

55.

Hung MJ Hsu KH Hu WS Chang NC Hung MY . C-reactive protein for predicting prognosis and its gender-specific associations with diabetes mellitus and hypertension in the development of coronary artery spasm. PLoS One. (2013) 8(10):e77655. 10.1371/journal.pone.0077655

56.

Seccia TM Rigato M Ravarotto V Calò LA . ROCK (Rhoa/Rho kinase) in cardiovascular-renal pathophysiology: a review of new advancements. J Clin Med. (2020) 9(5):1328. 10.3390/jcm9051328

57.

Wang Y Wang X Chen Y Zhang Y Zhen X Tao S et al Perivascular fat tissue and vascular aging: a sword and a shield. Pharmacol Res. (2024) 203:107140. 10.1016/j.phrs.2024.107140

58.

Niccoli G Montone RA Cataneo L Cosentino N Gramegna M Refaat H et al Morphological-biohumoral correlations in acute coronary syndromes: pathogenetic implications. Int J Cardiol. (2014) 171(3):463–6. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.12.238

59.

Funayama A Watanabe T Tamabuchi T Otaki Y Netsu S Hasegawa H et al Elevated cystatin C levels predict the incidence of vasospastic angina. Circ J. (2011) 75(10):2439–44. 10.1253/circj.CJ-11-0008

60.

Talarico GP Crosta ML Giannico MB Summaria F Calò L Patrizi R . Cocaine and coronary artery diseases: a systematic review of the literature. J Cardiovasc Med. (2017) 18(5):291–4. 10.2459/JCM.0000000000000511

61.

Lenders GD Jorens PG Meyer D Vandendriessche T Verbrugghe T Vrints W et al Coronary spasm after the topical use of cocaine in nasal surgery. Am J Case Rep. (2013) 14:76–9. 10.12659/AJCR.883837

62.

Kern MJ Ganz P Horowitz JD Gaspar J Barry WH Lorell BH et al Potentiation of coronary vasoconstriction by beta-adrenergic blockade in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation. (1983) 67(6):1178–85. 10.1161/01.CIR.67.6.1178

63.

Tilmant PY Lablanche JM Thieuleux FA Dupuis BA Bertrand ME . Detrimental effect of propranolol in patients with coronary arterial spasm countered by combination with diltiazem. Am J Cardiol. (1983) 52(3):230–3. 10.1016/0002-9149(83)90113-3

64.

Manuel SL Sapone J Lin F . Tacrolimus-induced recurrent acute coronary syndrome due to an unknown mechanism. Cureus. (2024) 16(6):e63266. 10.7759/cureus.63266

65.

Zafar A Drobni ZD Mosarla R Alvi RM Lei M Lou UY et al The incidence, risk factors, and outcomes with 5-fluorouracil-associated coronary vasospasm. JACC CardioOncol. (2021) 3(1):101–9. 10.1016/j.jaccao.2020.12.005

66.

Teragawa H Fukuda Y Matsuda K Hirao H Higashi Y Yamagata T et al Myocardial bridging increases the risk of coronary spasm. Clin Cardiol. (2003) 26(8):377–83. 10.1002/clc.4950260806

67.

Montone RA Gurgoglione FL Del Buono MG Rinaldi R Meucci MC Iannaccone G et al Interplay between myocardial bridging and coronary spasm in patients with myocardial ischemia and non-obstructive coronary arteries: pathogenic and prognostic implications. J Am Heart Assoc. (2021) 10(14):e020535. 10.1161/JAHA.120.020535

68.

Ishii T Ishikawa Y Akasaka Y . Myocardial bridge as a structure of “double-edged sword” for the coronary artery. Ann Vasc Dis. (2014) 7(2):99–108. 10.3400/avd.ra.14-00037

69.

Fernandez D Rosenthal JE Cohen LS Hammond G Wolfson S . Alcohol-induced prinzmetal variant angina. Am J Cardiol. (1973) 32(2):238–9. 10.1016/S0002-9149(73)80128-6

70.

Altura BM Altura BT Carella A . Ethanol produces coronary vasospasm: evidence for a direct action of ethanol on vascular muscle. Br J Pharmacol. (1983) 78(2):260–2. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1983.tb09389.x

71.

Kashima T Tanaka H Arikawa K Ariyama T . Variant angina induced by alcohol ingestion. Angiology. (1982) 33(2):137–9. 10.1177/000331978203300210

72.

Oda H Suzuki M Oniki T Kishi Y Numano F . Alcohol and coronary spasm. Angiology. (1994) 45(3):187–97. 10.1177/000331979404500303

73.

Arai M Okuno F Ishii H Hirano Y Sujita K Kobayashi T et al Alteration of prostaglandin metabolism in alcoholic liver disease: its association with platelet dysfunction after chronic alcohol ingestion. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. (1989) 86(2):220–6.

74.

Dong QS Wroblewska B Myers AK . Inhibitory effect of alcohol on cyclic GMP accumulation in human platelets. Thromb Res. (1995) 80(2):143–51. 10.1016/0049-3848(95)00160-S

75.

Vanoni FO Milani GP Agostoni C Treglia G Faré PB Camozzi P et al Magnesium metabolism in chronic alcohol-use disorder: meta-analysis and systematic review. Nutrients. (2021) 13(6):1959. 10.3390/nu13061959

76.

Sohn SM Choi BG Choi SY Byun JK Mashaly A Park Y et al Impact of alcohol drinking on acetylcholine-induced coronary artery spasm in Korean populations. Atherosclerosis. (2018) 268:163–9. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2017.11.032

77.

Mizuno Y Harada E Morita S Kinoshita K Hayashida M Shono M et al East Asian variant of aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 is associated with coronary spastic angina: possible roles of reactive aldehydes and implications of alcohol flushing syndrome. Circulation. (2015) 131(19):1665–73. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.013120

78.

Pijls NH van der Werf T . Prinzmetal’s angina associated with alcohol withdrawal. Cardiology. (1988) 75(3):226–9. 10.1159/000174376

79.

Hokimoto S Kaikita K Yasuda S Tsujita K Ishihara M Matoba T et al JCS/CVIT/JCC 2023 guideline focused update on diagnosis and treatment of vasospastic angina (coronary spastic angina) and coronary microvascular dysfunction. J Cardiol. (2023) 82(4):293–341. 10.1016/j.jjcc.2023.06.009

80.

Ishizuka K Ohira Y Ohta M . Paroxysmal toothache after drinking: alcohol-induced vasospastic angina. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. (2025) 12(3):005170. 10.12890/2025_005170

81.

Aswathappa S Watson AJ Nawaz B Jani A Razi S Baral S et al A comprehensive literature review discussing diagnostic challenges of prinzmetal or vasospastic angina. Cureus. (2025) 17(5):e83745. 10.7759/cureus.83745

82.

Choi WG Kim SH Rha SW Chen KY Li YJ Choi BG et al Impact of old age on clinical and angiographic characteristics of coronary artery spasm as assessed by acetylcholine provocation test. J Geriatr Cardiol. (2016) 13(10):824–9. 10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2016.10.005

83.

Han Y Kim SY . Endothelial senescence in vascular diseases: current understanding and future opportunities in senotherapeutics. Exp Mol Med. (2023) 55(1):1–12. 10.1038/s12276-022-00906-w

84.

Santos DF Simão S Nóbrega C Bragança J Castelo-Branco P Araújo IM . Oxidative stress and aging: synergies for age related diseases. FEBS Lett. (2024) 598(17):2074–91. 10.1002/1873-3468.14995

85.

Mohammadi Jouabadi S Claringbould A Danser AHJ Stricker BH Kavousi M Roks AJM et al High-sensitivity C reactive protein mediates age-related vascular dysfunction: the rotterdam study. Eur J Prev Cardiol. (2025) 00:1–11. 10.1093/eurjpc/zwaf370

86.

Takagi Y Takahashi J Yasuda S Miyata S Tsunoda R Ogata Y et al Prognostic stratification of patients with vasospastic angina: a comprehensive clinical risk score developed by the Japanese coronary spasm association. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2013) 62(13):1144–53. 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.07.018

87.

Li YJ Hyun MH Rha SW Chen KY Jin Z Dang Q et al Diabetes mellitus is not a risk factor for coronary artery spasm as assessed by an intracoronary acetylcholine provocation test: angiographic and clinical characteristics of 986 patients. J Invasive Cardiol. (2014) 26(6):234–9.

88.

Kang KW Choi BG Rha SW . Impact of insulin resistance on acetylcholine-induced coronary artery spasm in non-diabetic patients. Yonsei Med J. (2018) 59(9):1057–63. 10.3349/ymj.2018.59.9.1057

89.

Teragawa H Uchimura Y Oshita C Hashimoto Y Nomura S . Clinical characteristics and major adverse cardiovascular events in diabetic and non-diabetic patients with vasospastic angina. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes Targets Ther. (2024) 17:2135–46. 10.2147/DMSO.S462234

90.

Shinozaki K Suzuki M Ikebuchi M Takaki H Hara Y Tsushima M et al Insulin resistance associated with compensatory hyperinsulinemia as an independent risk factor for vasospastic angina. Circulation. (1995) 92(7):1749–57. 10.1161/01.CIR.92.7.1749

91.

Hung MJ Chang NC Hu P Chen TH Mao CT Yeh CT et al Association between coronary artery spasm and the risk of incident diabetes: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Int J Med Sci. (2021) 18(12):2630–40. 10.7150/ijms.57987

92.

Hokimoto S Kaikita K Yasuda S Tsujita K Ishihara M Matoba T et al JCS/CVIT/JCC 2023 guideline focused update on diagnosis and treatment of vasospastic angina (coronary spastic angina) and coronary microvascular dysfunction. Circ J. (2023) 87(6):879–936. 10.1253/circj.CJ-22-0779

93.

He Z Xu X Zhao Q Ding H Wang DW . Vasospastic angina: past, present, and future. Pharmacol Ther. (2023) 249:108500. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2023.108500

94.

Chen KY Rha SW Li YJ Poddar KL Jin Z Minami Y et al Impact of hypertension on coronary artery spasm as assessed with intracoronary acetylcholine provocation test. J Hum Hypertens. (2010) 24(2):77–85. 10.1038/jhh.2009.40

95.

Nunes KP Rigsby CS Webb RC . Rhoa/Rho-kinase and vascular diseases: what is the link?Cell Mol Life Sci. (2010) 67(22):3823–36. 10.1007/s00018-010-0460-1

96.

Kishi T Hirooka Y Masumoto A Ito K Kimura Y Inokuchi K et al Rho-kinase inhibitor improves increased vascular resistance and impaired vasodilation of the forearm in patients with heart failure. Circulation. (2005) 111(21):2741–7. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.510248

97.

Shimokawa H Takeshita A . Rho-kinase is an important therapeutic target in cardiovascular medicine. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. (2005) 25(9):1767–75. 10.1161/01.ATV.0000176193.83629.c8

98.

Satoh K Fukumoto Y Shimokawa H . Rho-kinase: important new therapeutic target in cardiovascular diseases. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. (2011) 301(2):H287–96. 10.1152/ajpheart.00327.2011

99.

Rha S-W Choi Byoung G Choi Se Y Park Y Goud Akkala R Lee S et al TCT-309 impact of hyperuricemia on coronary artery spasm as assessed with intracoronary acetylcholine provocation test. JACC. (2013) 62(18_Supplement_1):B99-B.

100.

Nishino M Mori N Yoshimura T Nakamura D Lee Y Taniike M et al Higher serum uric acid and lipoprotein(a) are correlated with coronary spasm. Heart Vessels. (2014) 29(2):186–90. 10.1007/s00380-013-0346-x

101.

Shali S Gao YB Zeng LZ Zhou P Dai YX . High uric acid induces vascular endothelial cell injury via XBP1-PKM2 mediated glycolytic inhibition. Eur Heart J. (2024) 45(1):ehae666.3839. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehae666.3839

102.

Liu Y Li Z Xu Y Mao H Huang N . Uric acid and atherosclerosis in patients with chronic kidney disease: recent progress, mechanisms, and prospect. Kidney Dis. (2025) 11(1):112–27. 10.1159/000543781

103.

Ciarambino T Crispino P Giordano M . Hyperuricemia and endothelial function: is it a simple association or do gender differences play a role in this binomial?Biomedicines. (2022) 10(12):3067. 10.3390/biomedicines10123067

104.

Woudstra J Vink CEM Schipaanboord DJM Eringa EC den Ruijter HM Feenstra RGT et al Meta-analysis and systematic review of coronary vasospasm in ANOCA patients: prevalence, clinical features and prognosis. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2023) 10:1129159. 10.3389/fcvm.2023.1129159

105.

Jansen TPJ Elias-Smale SE van den Oord S Gehlmann H Dimitiriu-Leen A Maas A et al Sex differences in coronary function test results in patient with angina and nonobstructive disease. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2021) 8:750071. 10.3389/fcvm.2021.750071

106.

Kawano H Motoyama T Hirai N Kugiyama K Ogawa H Yasue H . Estradiol supplementation suppresses hyperventilation-induced attacks in postmenopausal women with variant angina. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2001) 37(3):735–40. 10.1016/S0735-1097(00)01187-6

107.

Saitoh S Takeishi Y Maruyama Y . Mechanistic insights of coronary vasospasm and new therapeutic approaches. Fukushima J Med Sci. (2015) 61(1):1–12. 10.5387/fms.2015-2

108.

Hung MY Hsu KH Hu WS Chang NC Huang CY Hung MJ . Gender-specific prognosis and risk impact of C-reactive protein, hemoglobin and platelet in the development of coronary spasm. Int J Med Sci. (2013) 10(3):255–64. 10.7150/ijms.5383

109.

Watanabe T Kim S Akishita M Kario K Sekiguchi H Fujikawa H et al Circadian variation of autonomic nervous activity in patients with multivessel coronary spasm. Jpn Circ J. (2001) 65(7):593–8. 10.1253/jcj.65.593

110.

Tan BH Shimizu H Hiromoto K Furukawa Y Ohyanagi M Iwasaki T . Wavelet transform analysis of heart rate variability to assess the autonomic changes associated with spontaneous coronary spasm of variant angina. J Electrocardiol. (2003) 36(2):117–24. 10.1054/jelc.2003.50022

111.

Suematsu M Ito Y Fukuzaki H . The role of parasympathetic nerve activity in the pathogenesis of coronary vasospasm. Jpn Heart J. (1987) 28(5):649–61. 10.1536/ihj.28.649

112.

Meloni C Stazi F Ballarotto C Margonato A Chierchia SL . Heart rate variability in patients with variant angina: effect of the presence of significant coronary stenosis. Ital Heart J. (2000) 1(7):470–4.

113.

Yoshida K Utsunomiya T Morooka T Yazawa M Kido K Ogawa T et al Mental stress test is an effective inducer of vasospastic angina pectoris: comparison with cold pressor, hyperventilation and master two-step exercise test. Int J Cardiol. (1999) 70(2):155–63. 10.1016/S0167-5273(99)00079-0

114.

Mehta PK Thobani A Vaccarino V . Coronary artery spasm, coronary reactivity, and their psychological context. Psychosom Med. (2019) 81(3):233–6. 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000682

115.

Hung MY Mao CT Hung MJ Wang JK Lee HC Yeh CT et al Coronary artery spasm as related to anxiety and depression: a nationwide population-based study. Psychosom Med. (2019) 81(3):237–45. 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000666

116.

Jariwala P Kulkarni GP Gude D Boorugu HK Punjani A . Acute psychological stress, coronary artery spasm, iatrogenic coronary dissection, in-stent restenosis, and atherosclerosis: a rare association of multiple etiologies for recurrent acute coronary syndrome. J Pract Cardiovasc Sci. (2023) 9(3):195–9. 10.4103/jpcs.jpcs_71_23

117.

Camilli M Russo M Rinaldi R Caffè A La Vecchia G Bonanni A et al Air pollution and coronary vasomotor disorders in patients with myocardial ischemia and unobstructed coronary arteries. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2022) 80(19):1818–28. 10.1016/j.jacc.2022.08.744

118.

Sun Q Yue P Ying Z Cardounel AJ Brook RD Devlin R et al Air pollution exposure potentiates hypertension through reactive oxygen species-mediated activation of Rho/ROCK. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. (2008) 28(10):1760–6. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.166967

119.

Shimizu H Lee JD Yamamoto M Satake K Tsubokawa A Kawasaki N et al Induction of coronary artery spasm by combined cold pressor and hyperventilation test in patients with variant angina. J Cardiol. (1994) 24(4):257–61.

120.

Ong P Athanasiadis A Borgulya G Mahrholdt H Kaski JC Sechtem U . High prevalence of a pathological response to acetylcholine testing in patients with stable angina pectoris and unobstructed coronary arteries. The ACOVA study (abnormal coronary vasomotion in patients with stable angina and unobstructed coronary arteries). J Am Coll Cardiol. (2012) 59(7):655–62. 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.11.015

121.

Tan BYQ Kok CHP Ng MBJ Loong S Jou E Yeo LLL et al Exploring RNF213 in ischemic stroke and moyamoya disease: from cellular models to clinical insights. Biomedicines. (2024) 13(1):17. 10.3390/biomedicines13010017

122.

Tamura A Kawano Y Ando S Watanabe T Kadota J . Association between coronary spastic angina pectoris and obstructive sleep apnea. J Cardiol. (2010) 56(2):240–4. 10.1016/j.jjcc.2010.06.003

123.

Xu H Wang Y Guan J Yi H Yin S . Effect of CPAP on endothelial function in subjects with obstructive sleep apnea: a meta-analysis. Respir Care. (2015) 60(5):749–55. 10.4187/respcare.03739

124.

Cistulli PA Celermajer DS . Endothelial dysfunction and obstructive sleep apnea: the jury is still out!. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2017) 195(9):1135–7. 10.1164/rccm.201701-0237ED

125.

Al Jaber J Haque S Noor H Ibrahim B Al Suwaidi J . Thyrotoxicosis and coronary artery spasm: case report and review of the literature. Angiology. (2010) 61(8):807–12. 10.1177/0003319710365146

126.

Širvys A Baranauskas A Budrys P . A rare encounter: unstable vasospastic angina induced by thyrotoxicosis. J Clin Med. (2024) 13(11):3130. 10.3390/jcm13113130

127.

Zahavi I Chagnac A Hering R Davidovich S Kuritzky A . Prevalence of Raynaud’s phenomenon in patients with migraine. Arch Intern Med. (1984) 144(4):742–4. 10.1001/archinte.1984.00350160096017

128.

Nakamura Y Shinozaki N Hirasawa M Kato R Shiraishi K Kida H et al Prevalence of migraine and Raynaud’s phenomenon in Japanese patients with vasospastic angina. Jpn Circ J. (2000) 64(4):239–42. 10.1253/jcj.64.239

129.

Williams FM Cherkas LF Spector TD MacGregor AJ . A common genetic factor underlies hypertension and other cardiovascular disorders. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. (2004) 4(1):20. 10.1186/1471-2261-4-20

130.

Mach F Koskinas KC Roeters van Lennep JE Tokgözoğlu L Badimon L Baigent C et al 2025 focused update of the 2019 ESC/EAS guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias. Eur Heart J. (2025) 46(42):4359–78. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaf190

131.

Kunadian V Chieffo A Camici PG Berry C Escaned J Maas A et al An EAPCI expert consensus document on ischaemia with non-obstructive coronary arteries in collaboration with European society of cardiology working group on coronary pathophysiology & microcirculation endorsed by coronary vasomotor disorders international study group. Eur Heart J. (2020) 41(37):3504–20. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa503

132.

Núñez BD Miao L Wang Y Núñez MM Klein MA Sellke FW et al Cocaine-induced microvascular spasm in Yucatan miniature swine. In vivo and in vitro evidence of spasm. Circ Res. (1994) 74(2):281–90. 10.1161/01.RES.74.2.281

133.

Shirotani M Yokota R Kouchi I Hirai T Uemori N Haba K et al Influence of atenolol on coronary artery spasm after acute myocardial infarction in a Japanese population. Int J Cardiol. (2010) 139(2):181–6. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.10.017

134.

Kim HJ Jo SH Lee MH Seo WW Baek SH . Hyperthyroidism is associated with the development of vasospastic angina, but not with cardiovascular outcomes. J Clin Med. (2020) 9(9):3020. 10.3390/jcm9093020

135.

Anjum R Virk HUH Goyfman M Lee A John G . Thyrotoxicosis-related left main coronary artery spasm presenting as acute coronary syndrome. Cureus. (2022) 14(6):e26408. 10.7759/cureus.26408

136.

Seals DR Jablonski KL Donato AJ . Aging and vascular endothelial function in humans. Clin Sci. (2011) 120(9):357–75. 10.1042/CS20100476

137.