Abstract

Objective:

This study aims to evaluate the long-term outcomes of thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR) in patients with acute or subacute retrograde type A aortic dissection (RTAD). Additionally, it sought to identify the appropriate intraoperative stent landing zone and the optimal stent size.

Method:

A retrospective analysis was conducted on patients with acute/subacute RTAD who received TEVAR treatment at our hospital from January 1, 2013, to December 31, 2023. The aortic diameter was measured using the IFINIT imaging computing platform. Patient characteristics, surgical details, hospitalization, follow-up data, and aortic remodeling were analyzed. The stent landing zone and stent size were determined based on preoperative computed tomography angiography (CTA) images and intraoperative digital subtraction angiography (DSA), and were further verified through aortic remodeling results.

Outcomes:

A total of 78 patients were included, all of whom were admitted during the acute or subacute phase. In-hospital mortality and 30-day mortality rates were both 6.4%. The 30-day complication rate was 11.5%. The overall technical success rate was 98.7%. With a median follow-up time of 41 months (interquartile range 25.5–71.5 months), the overall cumulative survival rate were 91.7% (95% CI: 85.2%–98.2%) at 1 and 3 years, and 89.3% (95% CI: 81.5%–97.1%) at 5 years. One of the 78 patients developed an isolated ascending aorta dissection 6 months after surgery; this patient remains alive without treatment. During follow-up, positive ascending aortic remodeling was observed in 89.7% of patients.

Conclusion:

TEVAR appears to be a safe, effective, and durable treatment option for carefully selected patients with acute or subacute RTAD. Simultaneously, thorough screening is essential for patients presenting with dissection in the acute phase.

1 Introduction

Acute type A aortic dissection is a life-threatening aortic syndrome that involves the ascending aorta and necessitates emergency aortic repair. According to the Society for Vascular Surgery and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons reporting standards, retrograde dissection into the ascending aorta with an entry tear in zone 1 or beyond is classified as a type B aortic dissection, if it extends further retrograde into the ascending aorta, it is a RTAD (1). The incidence of RTAD accounts for approximately 7% to 25% of type A aortic dissection (TAAD) cases (2). Compared to TAAD, the optimal treatment approach for RTAD remains controversial (3, 4). Although aortic replacement is relatively straightforward, it leaves an entry tear that can result in the persistence of the false lumen and complications related to dissection, to sealing entry tear, total arch replacement using the frozen elephant trunk technique is considered the primary option for RTAD patients (5). However, for patients with high surgical risks, such as the elderly or those with significant comorbidities, open repair is associated with increased rates of mortality and complications. Studies indicate that TEVAR has emerged as an alternative to open surgery, effectively sealing the entry tear and promoting aortic remodeling (6). Endovascular therapy may be more beneficial in patients in whom open surgical repair is technically challenging and carries greater surgical risk (2). The American Association for Thoracic Surgery's expert consensus on the surgical management of acute type A aortic dissection suggests that TEVAR may be reasonable for selected patients with RTAD (7). Nevertheless, the efficacy of TEVAR in treating RTAD remains unclear, as only a limited number of patients have undergone this procedure, and reports on long-term outcomes are scarce. The aim of this study is to elucidate the short and long-term outcomes of TEVAR in the treatment of RTAD.

2 Method

2.1 Research design

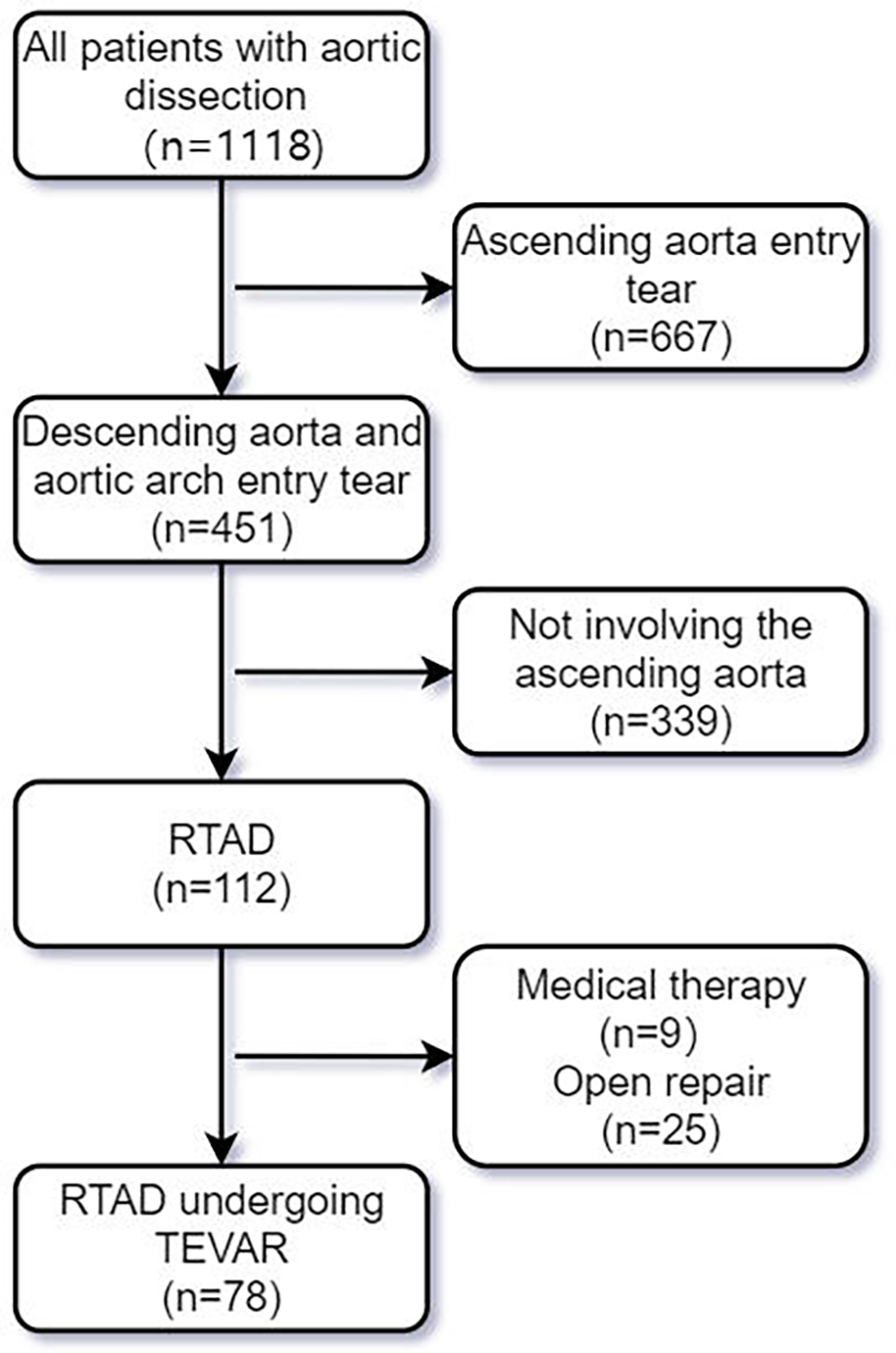

Among the 1,118 patients diagnosed with aortic dissection who visited our center from January 1, 2013, to December 31, 2023, we applied the following inclusion and exclusion criteria: (1). RTAD was clearly diagnosed by CTA with the entry tear located in the descending aorta or proximal aortic arch; (2). To rule out ascending aortic tear, for cases where CTA findings are inconclusive regarding ascending aortic tear, intraoperative aortography should be performed to establish a definitive diagnosis. (3). Open surgery is associated with higher mortality and complication rates in high-risk patients, such as elderly patients or those with severe comorbidities (including cognitive dysfunction, stroke, impaired tissue perfusion, and end-stage malignant diseases). (4). The patient declined open surgery. (5). Complete preoperative and postoperative impact data were available. A total of 78 patients were included in the study (Figure 1), and their baseline characteristics, images, as well as surgical and follow-up data, were prospectively collected and retrospectively reviewed. All-cause mortality was defined as the primary endpoint, while secondary endpoints included all adverse events related to aortic and TEVAR. All patients who underwent aortic CTA examinations were evaluated by a multidisciplinary team consisting of vascular surgeons, radiologists, and cardiac surgeons. The IFINIT software was simultaneously used to assess the initial tear location, total aortic diameters and true/false lumen diameters at multiple levels. The average measurement results from all researchers were taken as the final results. Measure the aortic diameter perpendicular to the blood flow direction (centerline technique). This study has been approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Zhengzhou People's Hospital (Ethics Review No.: 2025-ZYLW-025).

Figure 1

Screening flowchart for RTAD patients undergoing TEVAR.

2.2 Preoperative management, evaluation, and surgical strategy

All patients receiving treatment were administered optimal medical therapy and pain relief measures upon admission based on their needs. Patients undergoing TEVAR received subcutaneous injections of low molecular weight heparin for anticoagulation during hospitalization, while those with branch vessel reconstruction were prescribed long-term oral antiplatelet medications at discharge. During the medical management phase, indications for urgent intervention include persistent chest pain, hemodynamic instability, significant dilation of the proximal false lumen (FL), or the presence of periaortic or pericardial effusion (8).

During the operation, a vascular sheath was first inserted, and low molecular weight heparin was administered through the sheath to achieve heparinization. The true lumen was identified by combining CTA with intraoperative angiography to facilitate stent placement. In the selection of stent size, since the aortic anchoring zone is usually not perfectly circular, measurements should focus on the maximum and minimum diameters of the true lumen (the transverse and longitudinal diameters). When the maximum diameter does not exceed 5% of the minimum diameter, the maximum diameter should be used as the standard. When the maximum diameter exceeds 5% of the minimum diameter, the average diameter (automatically generated by the software based on area) should be used as the standard. Two strategies were available when employing fenestration technology: the first involves deploying the stent on the sterile operating table, fenestrating at designated positions, and then re-sheathing it; the second utilizes a puncture rupture needle after the stent graft deployment. We aimed to minimize cerebral ischemia time by first advancing the puncture needle retrograde to the target vessel orifice before deploying the covered stent, followed immediately by fenestration. Other routine measures taken to prevent perioperative stroke included minimizing manipulation within the aortic arch, reducing arch dwell time, thorough flushing of all devices, early heparinization, and maintaining mean arterial pressure near 100 mmHg following covered stent implantation. No abnormal cerebral oxygen saturation was detected during any of the procedures. After stent deployment, angiography is performed immediately after stent release to confirm coverage of entry tear and flow through the aortic lumen and branch vessels. Increased stent graft coverage of the descending thoracic aorta (>200 mm) and distal coverage within 20 mm of the celiac artery have been identified as risk factors for spinal cord ischemia (SCI). To reduce the risk of SCI, while ensuring coverage of the entry tear, it is recommended to minimize the length of stent coverage in the descending thoracic aorta and maintain a distance of more than 20 mm between the distal end of the stent and the celiac artery. For patients with paraplegia/paraparesis symptoms, establish cerebrospinal fluid drainage.

2.3 Follow-up

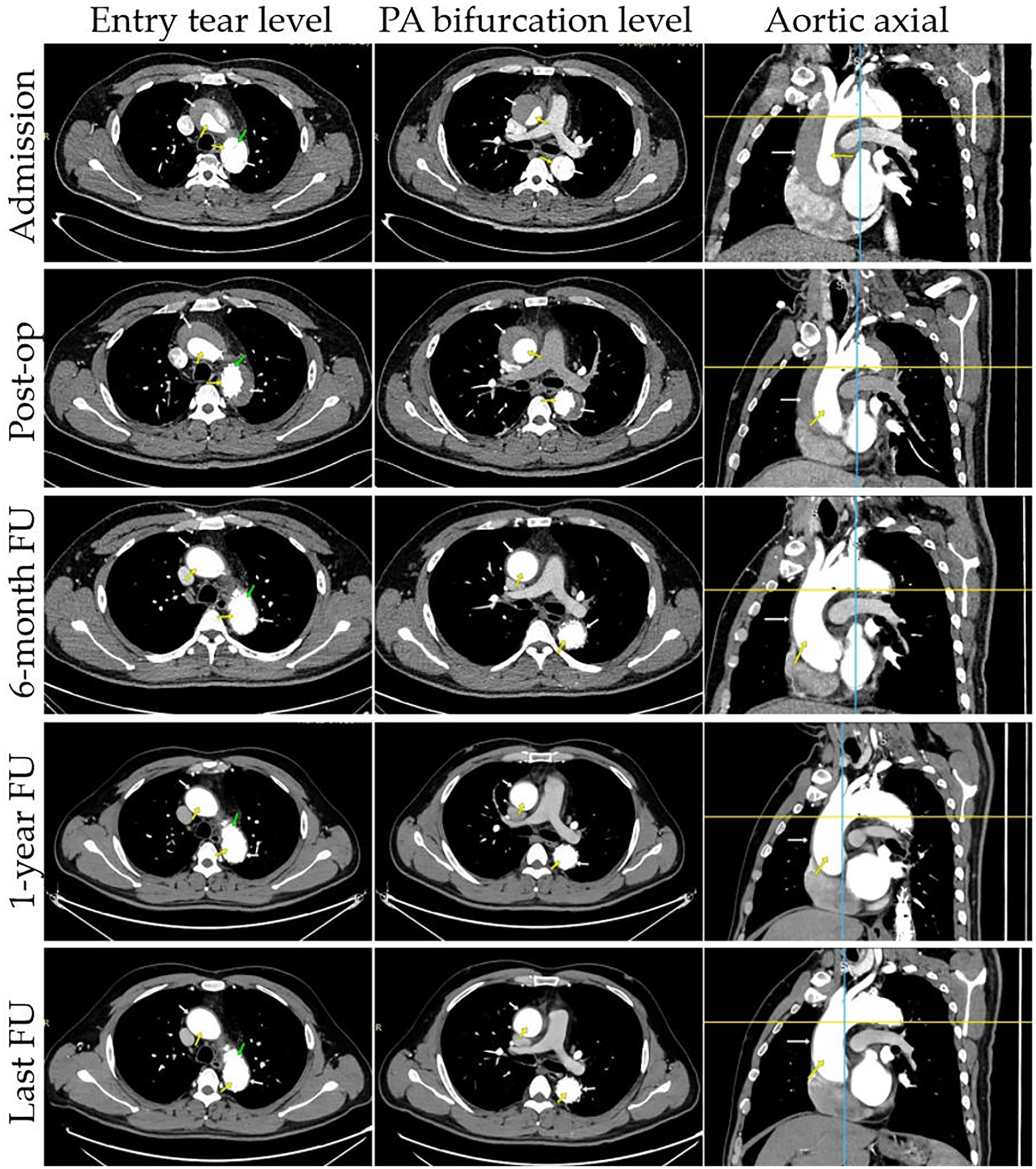

CTA were performed at 2 weeks, 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, and 1 year after TEVAR, with annual scans thereafter (Figure 2). For patients not under hospital observation, it is essential to gather as much information as possible by contacting the patient or a family member.

Figure 2

Representative cases of true and false lumens in different aortic segments. Results of CTA images at different time points are presented: entry tear level, PA bifurcation level, aortic axial. CTA images demonstrate the status of the false lumen (patent, partial thrombosis, complete thrombosis, partial absorption, complete absorption; white arrow) and true lumen (yellow arrow) at patient admission, post-operation, and follow-up. The entry tear was completely covered by the stent graft (green arrow).

2.4 Relevant definitions

Technical success: The stent was accurately deployed, completely covering the dissection tear, with successful branch vessel reconstruction. Aortic rupture is defined as hemorrhage outside of the boundaries of the aorta. Type Ia entry flow: Proximal perigraft entry flow; flow between the proximal endograft and aortic wall allowing systemic pressure antegrade flow into the primary entry tear and proximal false lumen. Type II entry flow: Retrograde entry flow through arch vessel branches or thoracic bronchial and intercostal arteries into the false lumen. Type R entry flow: Antegrade entry flow from the true lumen into the false lumen through distal branch fenestrations or septal fenestrations. Stent-graft induced new entry (SINE) is a new tear caused by the stent graft itself, excluding those created by natural disease progression or any iatrogenic injury from endovascular manipulation. The timing of the SINE reported as either early (≤30 days) or late (>30 days). A retrograde dissection is defined as any new ascending, arch, or descending dissection contiguous with and proximal to the original presenting anatomy.

2.5 Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation or median and interquartile range. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and proportions. Student t test or Mann–Whitney U-test was used for continuous variables. Graphs were drawn using GraphPad Prism 9.0.1 (GraphPad, Inc., California, USA). Cumulative survival rates were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method. A difference was considered significant if the P value was <0.05. SPSS 25.0 software (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY) was used for statistical analysis.

3 Results

3.1 Patient characteristics

Table 1 presents detailed information on baseline characteristics. The average age of the patients was 53.0 ± 8.5 years. Among the patients, there were 64 males (82.0%) and 14 females (18.0%). The four most common comorbidities were hypertension (n = 60, 76.9%), dyslipidemia (n = 34, 43.6%), pericardial effusion (n = 22, 28.2%), and renal insufficiency (n = 12, 15.4%). Primary entry tears in aortic dissection were found to originate from the descending aorta (n = 62, 79.5%), the abdominal aorta (n = 11, 14.1%), and the aortic arch (n = 5, 6.4%). At the time of TEVAR, the aortic dissection stage was acute in 74 cases (94.9%) and subacute in 4 cases (5.1%).

Table 1

| Variables | Data |

|---|---|

| Age,years | 53.0 ± 8.5 |

| Male | 64 (82.0) |

| BMI | 26.1 ± 4.2 |

| Comorbidities | |

| Hypertension | 60 (76.9) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 6 (7.7) |

| Coronary artery disease | 4 (5.1) |

| Prior stroke/TIA | 2 (2.6) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 0 (0.0) |

| Renal insufficiency | 12 (15.4) |

| Connective tissue disease | 0 (0.0) |

| Pericardial effusion | 22 (28.2) |

| Previous aortic surgery | 1 (1.3) |

| Dyslipidemia | 34 (43.6) |

| Smoking history | 24 (30.8) |

| Symptoms | |

| Chest pain | 74 (94.9) |

| Back pain | 67 (82.1) |

| Phase of dissection on admission | |

| Hyperacute, <1 day | 24 (30.8) |

| Acute, 1–14 days | 50 (64.1) |

| Subacute, 15–90 days | 4 (5.1) |

| Location of primary entry tear | |

| Aortic arch | 5 (6.4) |

| Descending aorta | 62 (79.5) |

| Abdominal aorta | 11 (14.1) |

| Ascending aortic diameter | 43.5 ± 5.3 |

| Proximal false lumen status | |

| Complete thrombosis | 4 (5.1) |

| Partial thrombosis | 34 (43.6) |

| Patent | 40 (51.3) |

| Arch involvement | 78 (100) |

| Malperfusion | 28 (35.9) |

| Branch vessel compromise | |

| LSA | 34 (43.6) |

| LCCA | 4 (5.1) |

| BCT | 3 (3.8) |

Patients baseline characteristics.

BMI, body mass index; TIA, transient ischemic attack; LSA, left subclavian artery; LCCA, left common carotid artery; BCT, Brachiocephalic trunk.

Data are presented as n (%) or mean ± standard deviation as appropriate.

3.2 Perioperative data

Four distinct types of thoracic aortic stent grafts were successfully implanted in all 78 patients, with primary entry tears effectively covered in each case. To ensure unobstructed blood flow in the branch vessels a branch vessel reconstruction technique was employed in 38 patients (48.7%). The left subclavian artery (LSA) was reconstructed in 34 patients, of whom 6 patients (7.7%) underwent reconstruction using single branched stents. The left common carotid artery (LCCA) and brachiocephalic trunk (BCT) were reconstructed in 4 (5.1%) and 3 (3.8%) patients, respectively, with 2 patients receiving simultaneous reconstructions of both BCT and LCCA. The types and sizes of stent grafts utilized are detailed in Table 2. All 78 patients underwent the procedure via the femoral artery approach, while those requiring reconstruction of the aortic arch branch vessels employed alternative approaches. The average stent-graft oversize in the proximal landing zone was 6.2 ± 1.3%.

Table 2

| Variables | Data |

|---|---|

| Stent graft used | |

| Lifetech Ankura | 48 (61.5) |

| MicroPort Talos | 15 (19.2) |

| Medtronic Valiant | 9 (11.5) |

| MicroPort Castor | 6 (7.7) |

| Stent graft oversize rate (%) | 6.2 ± 1.3 |

| Branch vascular reconstruction | |

| LSA | 34 (43.6) |

| ProtegeGPS (Medtronic, USA) | 25 (32.1) |

| VB (W.L. Gore & Associates, USA) | 3 (3.8) |

| LCCA | 4 (5.1) |

| Lifestream (BD, USA) | 3 (3.8) |

| ProtegeGPS (Medtronic, USA) | 1 (1.3) |

| BCT | 3 (3.8) |

| VB (W.L. Gore & Associates, USA) | 2 (2.6) |

| ProtegeGPS (Medtronic, USA) | 1 (1.3) |

| Stent diameter of proximal aorta, mm | 30 (30–32) |

| Stent diameter of distal aorta, mm | 26 (26–28) |

| Length of aortic stent graft, mm | 160 (160–200) |

Characteristics of the endografts.

Data are presented as n (%) or median (interquartile range) or mean ± standard deviation as appropriate. LSA, left subclavian artery; LCCA, left common carotid artery; BCT, brachiocephalic trunk.

The 30-day complication rate was 11.5%, with 5 patients succumbing during the postoperative hospitalization. Among these, 2 patients ascending aortic dissection progressed to the heart valve 2 days and 7 days after surgery respectively, involving the coronary arteries and causing cardiac arrest. Additionally, two patients died from the rupture of ascending aortic dissection 2 and 5 days after surgery. One patient was admitted with severe arrhythmia and experienced rapid ventricular arrhythmia 6 days post-surgery, leading to fatal outcomes. Another patient required surgical resection due to an inguinal incisional hematoma, while 2 patients experienced acute kidney injury that did not necessitate dialysis. Furthermore, 1 patient developed mild paraplegia of the left lower limb after surgery, but recovered following glucocorticoids pulse therapy. Postoperative type Ia and type R inflow complications were observed in 2.6% and 1.3% of patients, respectively. Notably, myocardial infarction, cerebral infarction, type II inflow, and SINE were not reported (Table 3).

Table 3

| Variables | Data |

|---|---|

| General anesthesia | 61 (78.2) |

| Operation time, minutes | 121.5 (102.75,141.25) |

| Approach | |

| Femoral artery | 78 (100) |

| Brachial artery | 28 (35.9) |

| Left common carotid artery | 4 (5.1) |

| Right common carotid artery | 3 (3.8) |

| ICU stay during hospitalization | 43 (55.1) |

| Length of ICU stay, hours | 39.0 (23.0,70.0) |

| Surgical blood loss, mL | 65 (50,85) |

| Length of hospital stay after surgery, day | 11.0 (8.0,16.0) |

| Operative technique | |

| TEVAR | 34 (43.6) |

| TEVAR combined with on-table fenestration | 14 (17.9) |

| TEVAR combined with in-situ fenestration | 24 (30.8) |

| TEVAR combined with branch revascularization | 38 (48.7) |

| Landing zone | |

| Zone 3 | 37 (47.4) |

| Zone 2 | 35 (4.9) |

| Zone 1 | 2 (2.6) |

| Zone 0 | 4 (5.1) |

| Reoperation with 30 days | |

| Aortic rupture | 2 (2.6) |

| Myocardial infarction | 0 (0.0) |

| Cerebral infarction | 0 (0.0) |

| Paraplegia | 1 (1.3) |

| Acute kidney injury | 2 (2.6) |

| Type Ia entry flow | 2 (2.6) |

| Type II entry flow | 0 (0.0) |

| Type R entry flow | 1 (1.3) |

| SINE | 0 (0.0) |

| Retrograde dissection | 0 (0.0) |

| Incision complications | 1 (0.0) |

| Puncture complications | 1 (1.3) |

| 30-days thoracic aortic reintervention | 0 (0.0) |

| In-hospital mortality | 5 (6.4) |

| 30-day mortality | 5 (6.4) |

Perioperative information.

ICU, intensive care unit; TEVAR, thoracic endovascular aortic repair; SINE, stent-graft induced new entry.

Data are presented as n (%) or median (interquartile range) as appropriate.

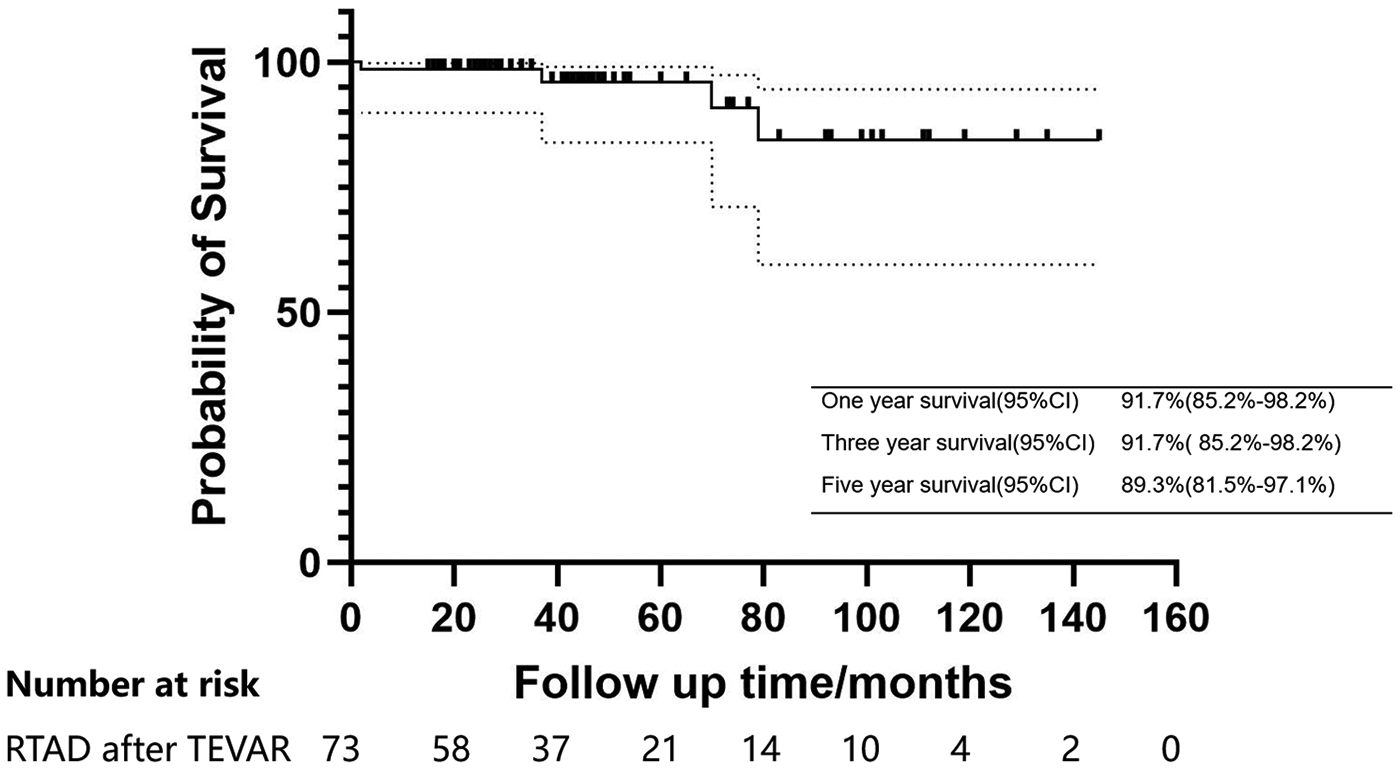

3.3 Follow-up date

The median follow-up duration was 41 months (25.5–71.5 months) (Table 4). The one and three-years survival rates were 91.7% (95% CI: 85.2%–98.2%), while the five-year survival rate was 89.3% (95% CI: 81.5%–97.1%) (Figure 3). One patient died from ascending aortic dissection two months post-surgery, two patients succumbed to heart failure at 37 and 79 months, and another patient experienced a sudden cerebral hemorrhage 70 months later. During the follow-up period, retrograde dissection, stroke, type II and type R entry flow, chronic renal insufficiency, and stent infection were not observed. However, paraplegia was noted in 1.3% of patients, by the end of the follow-up, the strength of the patients' lower limb muscles was approximately at level 3, and the defecation reflex had not yet recovered.

Table 4

| Variables | Data |

|---|---|

| Follow-up time, months | 41 (25.5–71.5) |

| Aortic rupture | 1 (1.3) |

| Stroke | 0 (0.0) |

| Type Ia entry flow | 1 (1.3) |

| Type II entry flow | 0 (0.0) |

| Type R entry flow | 0 (0.0) |

| Graft infection | 0 (0.0) |

| Chronic renal insufficiency | 0 (0.0) |

| Late open surgery | 1 (1.3) |

| Thoracic aortic reintervention | 0 (0.0) |

| Late SINE | 1 (1.3) |

Follow-up date.

SINE, stent-graft induced new entry.

Data are presented as n (%) or median (interquartile range) as appropriate.

Figure 3

Kaplan–meier estimates of survival in patients with acute/subacute RTAD undergoing endovascular repair.

Type Ia entry flow was also observed in 1.3% of patients, throughout the follow-up, the false lumen in this patient showed no signs of progression. Patient was advised to undergo regular reviews, and no surgical treatments were performed. Additionally, 1.3% of patients developed a new tear in the ascending aorta 11 months after surgery. This tear was located near the aortic valve, necessitating open surgery to replace the ascending aorta. At 6 months post-operation, one patient was found to have SINE (intimal tear in the ascending aorta), leading to an isolated ascending aortic dissection. Thrombosis of the false lumen was observed during follow-up. The patient is currently alive, and the latest examination revealed a significant increase in false lumen thrombosis compared to previous evaluations.

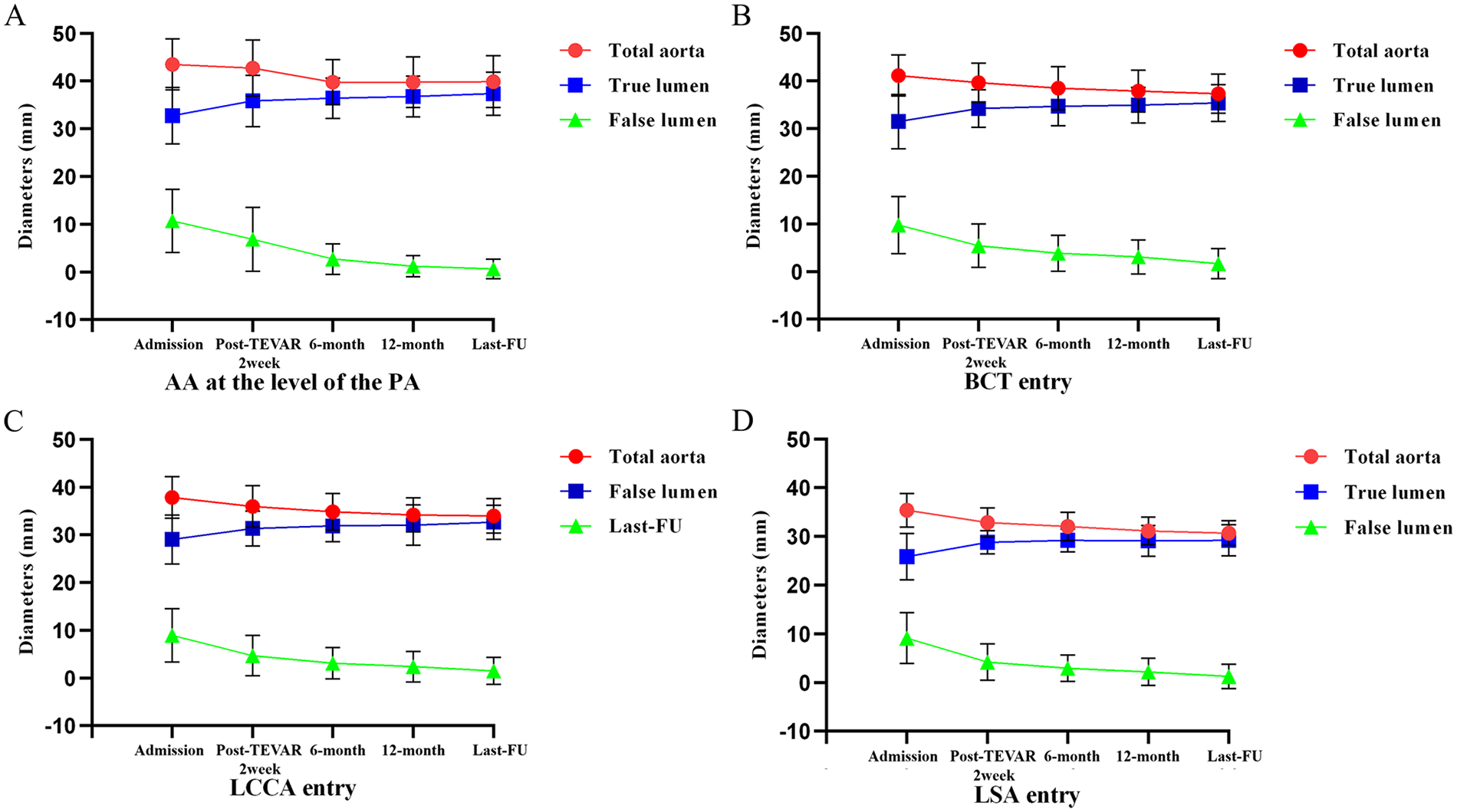

3.4 Aortic remodeling

The aortic remodeling status of patients preoperatively and at last follow-up was as follows: The mean diameter of the ascending aorta was 43.5 ± 5.3 mm preoperatively and 39.7 ± 5.5 mm at last follow-up; the mean diameters of the false lumen and true lumen were 10.7 ± 6.6 mm and 2.5 ± 5.4 mm, 32.8 ± 5.9 mm and 37.2 ± 5.1 mm preoperatively and at last follow-up, respectively (P < 0.001) (Table 5). To evaluate postoperative remodeling, all patients underwent multilevel measurements of the entire aorta and true/false lumen diameters at hospital admission, 2 weeks postoperatively, 6-month follow-up, 12-month follow-up, and last follow-up. Additionally, multi-planar illustrations depicting the changes in total aortic diameter and true/false lumen diameters at different follow-up time points were created to visualize the trend of morphological changes (Figure 4).

Table 5

| Diameters,mm | Pre-TEVAR | Last Follow-up | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| AA at the level of the PA | |||

| Aortic | 43.5 ± 5.3 | 39.7 ± 5.5 | <0.001 |

| TL | 32.8 ± 5.9 | 37.2 ± 5.1 | <0.001 |

| FL | 10.7 ± 6.6 | 2.5 ± 5.4 | <0.001 |

| BCT entry | |||

| Aortic | 41.2 ± 4.4 | 37.3 ± 4.1 | <0.001 |

| TL | 31.5 ± 5.7 | 35.4 ± 3.9 | <0.001 |

| FL | 9.8 ± 6.0 | 1.9 ± 3.8 | <0.001 |

| LCCA entry | |||

| Aortic | 37.8 ± 4.4 | 34.0 ± 3.6 | <0.001 |

| TL | 29.0 ± 5.1 | 32.7 ± 3.6 | <0.001 |

| FL | 8.9 ± 5.6 | 1.5 ± 2.8 | <0.001 |

| LSA entry | |||

| Aortic | 34.9 ± 3.7 | 30.9 ± 2.9 | <0.001 |

| TL | 25.8 ± 4.7 | 29.7 ± 2.4 | <0.001 |

| FL | 9.1 ± 5.1 | 1.2 ± 2.8 | <0.001 |

Changes in aortic diameter Pre-TEVAR and last follow-up patients with RTAD.

AA, ascending aorta; PA, pulmonary artery; BCT, brachiocephalic trunk; LCCA, left common carotid artery; LSA, left subclavian artery; TL, true lumen; FL, false lumen.

Data are presented mean ± standard deviation.

Figure 4

Diameter changes of the total aorta, true lumen, and false lumen at different levels across multiple time points. (admission, 2 weeks, 6 months, 1 year and last follow-up after TEVAR). (A) AA at the level of the PA. (B) The aorta of BCT entry. (C) The aorta of LCCA entry. (D) The aorta of LSA entry.

4 Discussion

Although RTAD involves the ascending aorta, it possesses distinct anatomical characteristics that may manifest as more stable hemodynamics, slower progression of dissection, and potentially better prognosis compared to typical TAAD (9). As a special subtype of TAAD, the incidence of RTAD is considerably lower than that of standard TAAD. Given its rarity and the complexities of endovascular repair involving the ascending aorta—requiring the graft to be positioned close to the ascending aorta for an effective landing zone, as well as the reconstruction of supra-aortic arch branch vessels in certain patients—there remains a lack of consensus regarding the endovascular management of RTAD.

More than three decades ago, surgical repair, such as ascending aorta replacement, was considered a standard option (10). However, this approach inevitably results in an entry tear and a patent FL in the descending aorta (11). Erbel et al. reported that the simple replacement of the ascending aorta in RTAD was associated with an 83% FL patency rate, additionally, the mortality rate in patients with a patent FL can reach as high as 43% (12). Several investigators have demonstrated that patent FL is strongly associated with various late complications, including distal aortic aneurysm expansion, reoperation, and death from rupture (13, 14). Since Nienaber and Dake first employed endovascular repair to treat RTAD in 1999, TEVAR has evolved into a selective treatment strategy for aortic disease, particularly type B dissection (15). TEVAR is regarded as a procedure that facilitates favorable remodeling of the affected aorta, potentially aiding in the prevention of late adverse events such as the development of thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm and the need for eventual open surgery (16). This advantage may warrant the preference for TEVAR over conservative treatment. With advancements in endovascular equipment and technology, endovascular repair has been utilized to address aortic arch pathologies, including AA. Some early studies have indicated success with TEVAR in highly selected patients with RTAD (17, 18); however, limited sample sizes and/or follow-up durations constrain the impact of these studies. This study concentrates on the application of TEVAR in treating patients with acute or subacute RTAD. In a relatively large cohort of 78 patients, we observed favorable late outcomes and aortic remodeling. These positive outcomes further confirm the clinical value of TEVAR as a safe and effective treatment option for highly selected RTAD patients.

The proper landing zone is a critical factor influencing the outcomes of TEVAR. Yoon et al. compared the results of TEVAR with proximal landing zones of ≥20 mm and <20 mm, finding that a landing zone of <20 mm was associated with a higher incidence of adverse events, particularly type Ia entry (19). In certain TEVAR procedures involving aortic arch pathologies, coverage of the aortic arch branch vessels may be required to achieve an adequate proximal landing zone (20). To ensure adequate blood perfusion to the upper limbs and brain, these patients require reconstruction of the branches of the aortic arch. Concurrently, to minimize the duration of cerebral hypoperfusion, it is crucial to perform revascularization of the branch vessels in the shortest possible time for successful treatment, including the LSA, the reconstruction of which was once controversial but has now reached a consensus on the necessity of its reconstruction (21). Various endovascular techniques have been employed for the revascularization of the supra-aortic trunk, including the chimney technique, customized branch stent-graft, in situ fenestration, and fenestrated surgeon-modified stent-graft, all of which have yielded satisfactory results (22–25). It is noteworthy that this study employed various endovascular techniques and branch reconstruction strategies, with technical variability potentially influencing outcomes. Compared to patients without supra-aortic branch reconstruction, branch reconstruction may increase the risk of type Ia entry; while in-situ fenestration carries a higher likelihood of cerebral malperfusion compared to on-table fenestration. Furthermore, as stent materials continued to improve during the observation period and complications such as entry flow and SCI were further reduced, the findings of this study may not fully reflect the current practical application of TEVAR technology.

Postoperative aortic or dissection-related events in patients undergoing TEVAR for RTAD should not be overlooked, as the emergence of new TAAD is a significant concern. The incidence of new TAAD following TEVAR has been reported to range from 1.3% to 6.8% (26–30). Studies indicate that patients treated with TEVAR for aortic dissection, particularly RTAD, exhibit a higher likelihood of developing new TAAD (30). There are two potential mechanisms that may elucidate this phenomenon. Firstly, TEVAR itself may compromise the integrity of the aortic wall, rendering it more susceptible to subsequent dissections. Alternatively, there may be an inherent vulnerability in the ascending aortic wall, and considering the time interval between TEVAR and the onset of new TAAD, the latter explanation appears more plausible (18). In this study, one patient experienced new TAAD 11 months post-surgery, further substantiating the notion of potential fragility in the ascending aortic wall.

SINE is a specific adverse event following TEVAR. Typically, the placement of the end of the stent graft at the aortic dissection site may lead to intimal injury. In our study, one patient (1.3%) experienced intimal injury near the stent graft. Factors contributing to SINE include oversizing, an excessive angle between the proximal aorta and the end of the stent graft, and the use of a proximal bare stent. Proximal landing zone oversizing is crucial to prevent RTAD, and Liu et al. suggested that a proximal oversize of less than 5% is ideal for TEVAR treatment of TBAD (31). Moreover, the use of a bare proximal stent allows for expansion without restriction from the covering material, thereby providing sufficient radial force for improved proximal fixation of the stent. The angle between the proximal end of the aorta and the stent graft plays a significant role in the stress experienced by the stent and the aortic wall, which is influenced by the stent's resilience. A larger angle results in a stronger retraction force of the stent as it attempts to return to its original state. Additionally, the arterial wall in cases of aortic dissection is relatively fragile, and increased stress may heighten the risk of intimal injury. The study by Higashigawa et al. demonstrated that a larger angle correlates with a greater likelihood of intimal injury (18). An appropriate oversizing rate of aortic stent grafts may facilitate aortic remodeling. In this study, the mean oversizing rate employed was 6.2 ± 1.3%, demonstrating favorable aortic remodeling. This phenomenon may be attributed to the stent graft exerting radial force on the true lumen, thereby altering the hemodynamics of the false lumen and accelerating the thrombosis process within it. Simultaneously, the expanded true lumen restores blood perfusion, providing a foundation for vascular tissue regeneration. Future research could further investigate the mechanisms by which the oversizing rate promotes aortic remodeling.

Currently, there is no expert consensus or guideline recommending the optimal timing for TEVAR in the treatment of RTAD. In cases of chronic dissections, both the adventitia and intimal flap undergo fibrotic changes, leading to gradual stabilization and a low incidence of severe complications; however, the remodeling capacity of the distal true lumen remains limited (32, 33). Following stent graft implantation, the true lumen of the stented aortic segment is expanded by the stent graft, resulting in the radial force being distributed laterally to the aortic wall rather than longitudinally. In the acute phase, the fragility of the aorta increases, and the stent landing zone becomes compromised, which contributes to a higher incidence of aorta-related adverse events. Nonetheless, aortic remodeling occurs more rapidly in acute dissections compared to chronic ones (34). The benefits of aortic remodeling during the acute phase must be carefully weighed against the risks of potential aortic injury caused by the stents, which may elevate the likelihood of complications in patients. Some studies indicate that the cumulative survival rate for acute dissection is higher than that for chronic dissection (33). The results of this study demonstrate that among 74 patients who underwent TEVAR during the acute phase, a total of 5 cases (6.8%) of aorta-related adverse events were recorded, including severe complications such as aortic rupture, ascending aortic intimal tear, and delayed paraplegia. In contrast, the four patients who underwent TEVAR during the subacute phase did not experience adverse events such as aortic rupture, and their aortic remodeling was comparable to that of patients in the acute phase. However, the sample size of subacute-phase patients in this study was relatively small (only four cases), showing a significant imbalance with the acute-phase data. Subsequent research will expand the subacute-phase sample size for further comparison.

5 Conclusions

In a rigorously selected cohort of RTAD patients, TEVAR has demonstrated significant potential in terms of safety, efficacy, and long-term outcomes, with perioperative mortality and postoperative complication rates maintained at relatively low levels. However, postoperative aortic-related adverse events cannot be overlooked. Larger sample sizes and longer follow-up periods are required for further validation before this method gains widespread acceptance. Meanwhile, further development of the devices will help reduce the occurrence of adverse events.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Medical Ethics Committee of Zhengzhou People's Hospital. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

FW: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HL: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YW: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. WC: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. ZH: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. XS: Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

MacGillivray TE Gleason TG Patel HJ Aldea GS Bavaria JE Beaver TM et al The society of thoracic surgeons/American association for thoracic surgery clinical practice guidelines on the management of type B aortic dissection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. (2022) 163(4):1231–49. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2021.11.091

2.

Kim JB Choo SJ Kim WK Kim HJ Jung S-H Chung CH et al Outcomes of acute retrograde type A aortic dissection with an entry tear in descending aorta. Circulation. (2014) 130(11 Suppl 1):S39–44. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.007839

3.

Kaji S Akasaka T Katayama M Yamamuro A Yamabe K Tamita K et al Prognosis of retrograde dissection from the descending to the ascending aorta. Circulation. (2003) 108(1):II300–6. 10.1161/01.cir.0000087424.32901.98

4.

Nauta FJH Kim JB Patel HJ Peterson MD Eckstein H-H Khoynezhad A et al Early outcomes of acute retrograde dissection from the international registry of acute aortic dissection. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. (2017) 29(2):150–9. 10.1053/j.semtcvs.2016.10.004

5.

Kaneyuki D Mogi K Watanabe H Otsu M Sakurai M Takahara Y . The frozen elephant trunk technique for acute retrograde type A aortic dissection: preliminary results. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. (2020) 31(6):813–9. 10.1093/icvts/ivaa199

6.

Omura A Matsuda H Matsuo J Hori Y Fukuda T Inoue Y et al Thoracic endovascular repair for retrograde acute type A aortic dissection as an alternative choice. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. (2020) 68(12):1397–404. 10.1007/s11748-020-01397-0

7.

Malaisrie SC Szeto WY Halas M Girardi LN Coselli JS Sundt TM et al 2021 The American association for thoracic surgery expert consensus document: surgical treatment of acute type A aortic dissection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. (2021) 162(3):735–758.e2. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2021.04.053

8.

Wang J Jin T Chen B Pan Y Shao C . Systematic review and meta-analysis of current evidences in endograft therapy versus medical treatment for uncomplicated type B aortic dissection. J Vasc Surg. (2022) 76(4):1099–108. 10.1016/j.jvs.2022.03.876

9.

Chen Y-Y Yen H-T Lo C-M Wu C-C Huang DK-R Sheu J-J . Natural courses and long-term results of type A acute aortic intramural haematoma and retrograde thrombosed type A acute aortic dissection: a single-centre experience. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. (2020) 30:113–20. 10.1093/icvts/ivz222

10.

Miller DC Mitchell RS Oyer PE Stinson EB Jamieson SW Shumway NE . Independent determinants of operative mortality for patients with aortic dissections. Circulation. (1984) 70(3 Pt 2):I153–64.

11.

Kamohara K Furukawa K Koga S Yunoki J Morokuma H Noguchi R et al Surgical strategy for retrograde type A aortic dissection based on long-term outcomes. Ann Thorac Surg. (2015) 99(5):1610–5. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.12.059

12.

Erbel R Oelert H Meyer J Puth M Mohr-Katoly S Hausmann D et al Effect of medical and surgical therapy on aortic dissection evaluated by transesophageal echocardiography. Implications for prognosis and therapy. The European cooperative study group on echocardiography. Circulation. (1993) 87(5):1604–15. 10.1161/01.cir.87.5.1604

13.

Ergin MA Phillips RA Galla JD Lansman SL Mendelson DS Quintana CS et al Significance of distal false lumen after type A dissection repair. Ann Thorac Surg. (1994) 57(4):820–5. 10.1016/0003-4975(94)90182-1

14.

Haverich A Miller DC Scott WC Mitchell RS Oyer PE Stinson EB et al Acute and chronic aortic dissections–determinants of long-term outcome for operative survivors. Circulation. (1985) 72(3 Pt 2):II22–34.

15.

Dake MD Kato N Mitchell RS Semba CP Razavi MK Shimono T et al Endovascular stent-graft placement for the treatment of acute aortic dissection. N Engl J Med. (1999) 340:1546–52. 10.1056/NEJM199905203402004

16.

Nienaber CA Kische S Rousseau H Eggebrecht H Rehders TC Kundt G et al Endovascular repair of type B aortic dissection: long-term results of the randomized investigation of stent grafts in aortic dissection trial. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. (2013) 6(4):407–16. 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.113.000463

17.

Shu C Wang T Li Q-m Li M Jiang X-h Luo M-y et al Thoracic endovascular aortic repair for retrograde type A aortic dissection with an entry tear in the descending aorta. J Vasc Interv Radiol. (2012) 23(4):453–460.e1. 10.1016/j.jvir.2011.12.023

18.

Higashigawa T Kato N Nakajima K Chino S Hashimoto T Ouchi T et al Thoracic endovascular aortic repair for retrograde type A aortic dissection. J Vasc Surg. (2019) 69(6):1685–93. 10.1016/j.jvs.2018.08.193

19.

Yoon WJ Mell MW . Outcome comparison of thoracic endovascular aortic repair performed outside versus inside proximal landing zone length recommendation. J Vasc Surg. (2020) 72(6):1883–90. 10.1016/j.jvs.2020.03.033

20.

Czerny M Schmidli J Bertoglio L Carrel T Chiesa R Clough RE et al Clinical cases referring to diagnosis and management of patients with thoracic aortic pathologies involving the aortic arch: a companion document of the 2018 European association for cardio-thoracic surgery (EACTS) and the European society for vascular surgery (ESVS) expert consensus document addressing current options and recommendations for the treatment of thoracic aortic pathologies involving the aortic arch. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. (2019) 57(3):452–60. 10.1016/j.ejvs.2018.12.011

21.

Karaolanis GI Antonopoulos CN Charbonneau P Georgakarakos E Moris D Scali S et al A systematic review and meta-analysis of stroke rates in patients undergoing thoracic endovascular aortic repair for descending thoracic aortic aneurysm and type B dissection. J Vasc Surg. (2022) 76(1):292–301.e3. 10.1016/j.jvs.2022.02.031

22.

Chang H Jin D Wang Y Liu B Wang W Li Y . Chimney technique and single-branched stent graft for the left subclavian artery preservation during zone 2 thoracic endovascular aortic repair for type B acute aortic syndromes. J Endovasc Ther. (2023) 30(6):849–58. 10.1177/15266028221102657

23.

Blanco Amil CL Mestres Alomar G Guarnaccia G Luoni G Yugueros Castellnou X Vigliotti RC et al The initial experience on branched and fenestrated endografts in the aortic arch. A systematic review. Ann Vasc Surg. (2021) 75:29–44. 10.1016/j.avsg.2021.03.024

24.

Li X Zhang L Song C Zhang H Xia S Li H et al Outcomes of total endovascular aortic arch repair with surgeon-modified fenestrated stent-grafts on zone 0 landing for aortic arch pathologies. J Endovasc Ther. (2022) 29(1):109–16. 10.1177/15266028211036478

25.

Evans E Veeraswamy R Zeigler S Wooster M . Laser in situ fenestration in thoracic endovascular aortic repair: a single-center analysis. Ann Vasc Surg. (2021) 76:159–67. 10.1016/j.avsg.2021.05.006

26.

Neuhauser B Czermak BV Fish J Perkmann R Jaschke W Chemelli A et al Type A dissection following endovascular thoracic aortic stent-graft repair. J Endovasc Ther. (2005) 12(1):74–81. 10.1583/04-1369.1

27.

Kpodonu J Preventza O Ramaiah VG Shennib H Wheatley III GH Rodriquez-Lopez J et al Retrograde type A dissection after endovascular stenting of the descending thoracic aorta. Is the risk real?. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. (2008) 33(6):1014–8. 10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.03.024

28.

Eggebrecht H Thompson M Rousseau H Czerny M Lönn L Mehta RH et al Retrograde ascending aortic dissection during or after thoracic aortic stent graft placement: insight from the European registry on endovascular aortic repair complications. Circulation. (2009) 120(11 Suppl):S276–81. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.835926

29.

Dong ZH Fu WG Wang YQ Guo DQ Xu X Ji Y et al Retrograde type A aortic dissection after endovascular stent graft placement for treatment of type B dissection. Circulation. (2009) 119(5):735–41. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.759076

30.

Higashigawa T Kato N Chino S Hashimoto T Shimpo H Tokui T et al Type A aortic dissection after thoracic endovascular aortic repair. Ann Thorac Surg. (2016) 102(5):1536–42. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2016.04.024

31.

Liu L Zhang S Lu Q Jing Z Zhang S Xu B . Impact of oversizing on the risk of retrograde dissection after TEVAR for acute and chronic type B dissection. J Endovasc Ther. (2016) 23(4):620–5. 10.1177/1526602816647939

32.

Kato N Hirano T Shimono T Ishida M Takano K Nishide Y et al Treatment of chronic aortic dissection by transluminal endovascular stent-graft placement: preliminary results. J Vasc Interv Radiol. (2001) 12(7):835–40. 10.1016/s1051-0443(07)61508-5

33.

Schoder M Czerny M Cejna M Rand T Stadler A Sodeck GH et al Endovascular repair of acute type B aortic dissection: long-term follow-up of true and false lumen diameter changes. Ann Thorac Surg. (2007) 83(3):1059–66. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.10.064

34.

VIRTUE Registry Investigators. Mid-term outcomes and aortic remodelling after thoracic endovascular repair for acute, subacute, and chronic aortic dissection: the VIRTUE registry. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. (2014) 48(4):363–71. 10.1016/j.ejvs.2014.05.007

Summary

Keywords

aortic remodeling, branch vessel reconstruction, endovascular treatment, retrograde type A aortic dissection, thoracic endovascular aortic repair

Citation

Wang F, Li H, Wang Y, Chen W, Huang Z and Shu X (2026) Endovascular treatment of retrograde type A aortic dissection: a decade of experience in a single-center. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 13:1744586. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2026.1744586

Received

12 November 2025

Revised

25 December 2025

Accepted

02 January 2026

Published

16 January 2026

Volume

13 - 2026

Edited by

Massimo Bonacchi, University of Florence, Italy

Reviewed by

Guillaume Guimbretière, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire (CHU) de Nantes, France

Nikolaos Papatheodorou, Technical University of Munich, Germany

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Wang, Li, Wang, Chen, Huang and Shu.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Xiaojun Shu sxj19810924@163.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.