- 1The First Affiliated Hospital, Department of Cardiology, Hengyang Medical School, University of South China, Hengyang, Hunan, China

- 2School of Medicine, Hunan Polytechnic of Environment and Biology, Hengyang, Hunan, China

- 3Institute of Clinical Medicine, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Hainan Medical University, Haikou, Hainan, China

Cardiovascular and metabolic diseases severely threat human health with their management being a global challenge. C1q tumor necrosis factor-related protein 12 (CTRP12), a newly identified adipokine and paralog of adiponectin, is expressed predominantly by adipose tissue. As a secretory protein, full-length CTRP12 can be cleaved by furin to produce a globular isoform, which is the major form in the blood stream. CTRP12 has anti-inflammatory and glucose-lowering properties and also participates in the regulation of lipid metabolism, oxidative stress and cell apoptosis. Dysregulation of CTRP12 has been shown be involved in the occurrence and development of cardiovascular and metabolic diseases, including coronary artery disease, heart failure, diabetes, obesity and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Thus, targeting CTRP12 may have important implications in preventing and treating cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. To provide a comprehensive understanding of the role of CTRP12 in cardiovascular and metabolic diseases, this review delved into the structural characteristics and biological functions with an emphasis on its link to several major cardiovascular and metabolic diseases.

Highlights

CTRP12 is a newly discovered adipokine with multiple biological functions.

CTRP12 plays an important role in the development of CVMDs.

CTRP12 could be developed as a drug target for the treatment of CVMDs.

1 Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are a group of disorders impairing heart and blood vessels, predominantly encompassing coronary artery disease (CAD), cerebrovascular disease, and peripheral arterial disease. The pathogenesis of CVDs is complex and involves numerous pathological factors and signaling pathways, such as lipid metabolism dysregulation, inflammatory response and cell death (1–3). Although statin treatment has been widely used to modulate blood lipid levels, patients with established CVDs are often left with residual cardiovascular risk (4). Metabolic diseases are a type of disorders that primarily impede glucose and lipid metabolism, consisting of diabetes, obesity and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). With aging and changes of life style, the morbidity and mortality of cardiovascular and metabolic diseases continues to increase in recent years, bringing a huge economic burden across the world (5–7). Prevention and treatment of cardiovascular and metabolic diseases have become a major challenge despite great progress has been made in this field. Thus, a comprehensive understanding of the role of key players in cardiovascular and metabolic diseases is of great scientific significance and clinical value.

Adipose tissue not only plays a critical role in energy storage but also functions as a large active endocrine organ that can express and secrete a variety of adipokines, including adiponectin, leptin, visfatin, apelin and C1q tumor necrosis factor-related proteins (CTRPs). As the most extensively investigated adipokine, adiponectin is essential to maintain normal cardiovascular and metabolic functions (8, 9). CTRPs belong to a highly conserved family of adiponectin paralogs and share significant sequence homology with the immune complement component C1q (10). Currently, 15 members have been identified, ranging from CTRP1 to CTRP15. CTRP12, also called adipolin, is a recently discovered adipokine and plays an important role in regulating cardiovascular and metabolic functions (11). Dysregulation of CTRP12 has been shown to be closely associated with cardiovascular and metabolic diseases, such as CAD, heart failure, diabetes, obesity and NAFLD (12, 13). This sheds lights on CTRP12 as a novel and promising target for the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. In this review, we summarized the current knowledge about the role of CTRP12 in cardiovascular and metabolic diseases to provide an important framework for future investigation and therapeutic intervention.

2 The origin, structure, metabolic pathway and biological properties of CTRP12

CTRP12 was first identified as an insulin-sensitizing adipokine by Enomoto et al. in 2011 (14). Mouse CTRP12 gene (Gene ID: 67389) contains 8 exons and is mapped to chromosome 4 E2. Like adiponectin, mouse CTRP12 protein is divided into 4 regions: a signal peptide that can direct protein secretion, an N-terminal domain essential for the assembly of higher order oligomeric structure, a collagen domain with six Gly-X-Y repeats, and a C-terminal globular C1q domain with three conserved Cys residues and two potential N-glycosylation sites (Figure 1). The N-terminal domain contains three potential N-linked glycosylation sites, four Cys residues and an endopeptidase cleavage motif (KKXR). These features indicate that the protein likely undergoes multiple types of posttranslational modification. Adiponectin is known to be expressed almost exclusively by adipocytes (15). However, CTRP12 is more widely expressed in mice, with the comparable expression levels in white and brown adipose tissues (16).

Figure 1. Schematic structure, cleavage and signaling specificity of CTRP12. CTRP12 is made up of four domains: a signal peptide for secretion, an N-terminal domain with multiple conserved Cys residues, a collagen domain with Gly-X-Y repeats, and a C-terminal globular domain homologous to the immune complement C1q. The full-length CTRP12 protein can be cleaved by furin to generate a globular isoform as the predominant form in circulation. Full-length CTRP12 preferentially activates Akt signaling to facilitate insulin-stimulated glucose uptake. Globular CTRP12 preferentially activates MAPK signaling.

Human CTRP12 gene (Gene ID: 388581) encompasses 9 exons and is localized in chromosome 1p36.33. Human CTRP12 protein and its corresponding mouse ortholog share 71% and 83% amino acid identity in their full-length form and globular domain, respectively (11). Similar to adiponectin, CTRP12 is expressed predominantly by adipose tissue in humans, with high induction during adipogenesis. Moreover, the higher expression of human CTRP12 mRNA in adipose tissue is correlated with its higher serum levels (16). CTRP12 is highly conserved throughout vertebrate evolution, including dogs, chickens, zebrafishes, frogs, mice and humans. Dysregulation of CTRP12 expression has been frequently observed in a variety of diseases. For instance, increased CTRP12 expression is seen during chondrocyte differentiation, suggesting that this adipokine may be involved in cartilage maturation and development (17). Serum CTRP12 levels in Hashimoto's thyroiditis patients are higher than those in healthy subjects (18). In patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, serum CTRP12 levels are decreased as compared to healthy individuals and show a negative correlation with disease severity (19). Although no statistically significant difference is determined between endometrial cancer patients with and without omentectomy in respect of serum CTRP12 levels measured preoperatively, the postoperative blood levels of CTRP12 are significantly increased compared with the preoperative value (20). This reveals a positive effect of omentectomy on CTRP12 metabolism in endometrial cancer patients.

Krueppel-like factor 15 (KLF15) is a significant member of the zinc-finger family of transcription factors. It has been reported that KLF15 is able to up-regulate the expression of CTRP12 by binding to its promoter in adipocytes (21). KLF3 is another transcription factor involving the modulation of adipogenesis (22). Bell-Anderson et al. found that KLF3 inhibits CTRP12 transcription and consequently leads to glucose intolerance in mice (23). In subcutaneous adipose tissue explants, insulin dramatically enhances the expression and secretion of CTRP12 by activating phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (24). Metformin belongs to one of first-line therapeutic drugs for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Treatment with metformin leads to a significant increase in CTRP12 protein levels in subcutaneous adipose tissue, and this effect is attenuated by the inhibitor of AMP-activated protein kinase (25).

CTRP12 circulates in plasma as a full-length protein or a cleaved globular isoform, with the latter as the major circulating isoform (Figure 1). Furin, also called proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin 3, is an enzyme that belongs to the subtilisin-like proprotein convertase family. It has been demonstrated that furin is able to mediate the cleavage of CTRP12 at Lys-91 within the N-terminal KKXR motif (26). Treatment of adipocytes with tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) dramatically up-regulates furin expression, leading to increased production of the cleaved form (27). After secretion from mammalian cells, CTRP12 is subjected to N-linked glycosylation. Three N-linked glycosylation sites have been identified, designated as Asn-39, Asn-287, and Asn-297. When Asn-39 and Asn-297 are glycosylated, the cleavage of CTRP12 by furin is inhibited; however, Asn-287 is required for proper protein folding of CTRP12, which is independent of its glycosylation (28). It is important to note that both isoforms differ in oligomeric structure and signal transduction (26). The full-length CTRP12 protein forms the trimers and larger complexes and has stronger effects on the activation of Akt signaling. In contrast, the cleaved globular isoform of CTRP12 predominantly forms the dimers and preferentially activates mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling. Moreover, only full-length CTRP12 protein can promote glucose uptake stimulated by insulin in adipocytes. Thus, enhancing the proportion of full-length CTRP12 protein could be a more effective approach to improve insulin sensitivity.

3 Physiological function and pathological role of CTRP12

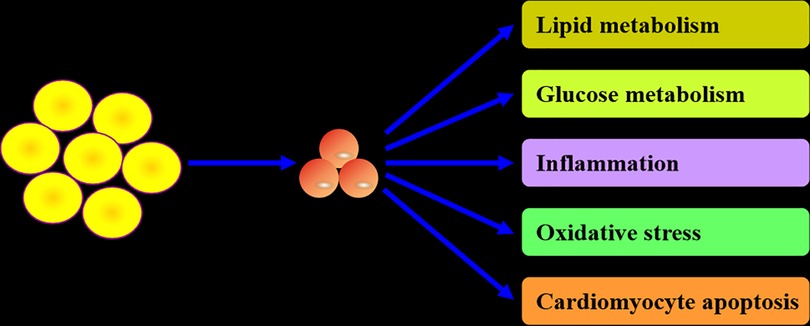

As a secretory protein, CTRP12 plays an important role in regulating lipid and glucose metabolism, inflammatory response, oxidative stress and cardiomyocyte apoptosis (Figure 2). These contents are discussed individually below.

Figure 2. Biological actions of CTRP12. CTRP12 is produced predominantly by adipocytes. As a multifunctional adipokine, CTRP12 participates in the regulation of lipid and glucose metabolism, inflammation, oxidative stress and cardiomyocyte apoptosis.

3.1 Lipid metabolism

Lipids predominantly contain fatty acids, cholesterol, phospholipids and triglycerides. They not only constitute the basic composition of plasma membrane but also play a crucial role in energy storage and signal transduction. Aberrant lipid metabolism is associated with a variety of diseases such as obesity and atherosclerosis (29). It is suggested that circulating CTRP12 levels show a positive correlation with high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) in CAD patients (30). Recent work from our group revealed that overexpression of CTRP12 inhibits macrophage lipid accumulation by stimulating cholesterol efflux (31). In hepatoma cells and primary mouse hepatocytes, treatment with recombinant CTRP12 protein inhibits lipogenesis by down-regulating the expression of glycerophosphate acyltransferase (GPAT) and diacylglycerol acyltransferase (DGAT), two key enzymes involving triglyceride synthesis (32). CTRP12 also reduces the export of very low-density lipoprotein-triglycerides from hepatocytes by suppressing the hepatocyte nuclear factor 4A (HNF4A)/microsomal triglyceride transfer protein (MTTP) signaling pathway (32). When challenged with a high-fat diet, CTRP12+/− male mice exhibit decreased triglyceride secretion and increased triglyceride and cholesterol levels in liver tissue (33). In contrast to male mice, partial deficiency of CTRP12 promotes hepatic triglyceride secretion in female mice fed a high-fat diet (33). These results suggest that loss of a single CTRP12 allele regulates lipid metabolism in a sex-dependent manner, highlighting the importance of genetic determinant in metabolic phenotypes. Of note, female mice exhibit higher levels of CTRP9 transcripts when compared with male mice, revealing a gender-biased expression pattern (34). Nevertheless, whether CTRP12 expression differs between males and females remains unknown and needs to be investigated.

3.2 Glucose metabolism

Adiponectin has been shown to participate in the regulation of glucose metabolism (35). As the paralog of adiponectin, CTRP12 also affects glucose metabolism. For instance, decreased serum CTRP12 levels are observed in type 2 diabetes patients as compared to healthy subjects (36). Circulating CTRP12 levels are negatively correlated with insulin resistance in CAD patients (30). Importantly, systemic administration of CTRP12 improves glucose intolerance and inhibits insulin resistance in diet-induced obese mice (14). Further studies showed that CTRP12 augments insulin secretion and increases tyrosine phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate (IRS-1), leading to reduced blood glucose in leptin-deficient ob/ob mice (16). These observations identify CTRP12 as an insulin-sensitizing adipokine. In addition, CTRP12 can directly activate the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt axis to antagonize gluconeogenesis and facilitate glucose uptake in diet-induced obese mice, suggesting the involvement of insulin-independent mechanism in glucose-lowering action of CTRP12 (16). Of note, insulin can also up-regulate CTRP12 expression (24). Thus, a positive feedback loop exists between CTRP12 and insulin.

3.3 Inflammatory response

In addition to lipid and glucose metabolism, CTRP12 is implicated in inflammatory response. Studies from our group demonstrated that overexpression of CTRP12 promotes the polarization of macrophages to M2 phenotype along with decreased monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) and TNF-α levels as well as increased interleukin (IL)-10 levels (37). Mechanistically, CTRP12 attenuates miR-155-5p levels and then up-regulates its target gene liver X receptor α (LXRα) expression to alleviate inflammatory response (37). In cardiomyocytes challenged with lipopolysaccharide (LPS), CTRP12 inhibits the transcription and subsequent release of TNF-α, IL-1 and IL-6 (38). In addition, serum CTRP12 levels show a negative correlation with TNF-α and IL-6 in CAD patients (30). Taken together, these findings reveal a protective effect of CTRP12 on inflammation.

3.4 Oxidative stress

Oxidative stress is defined as the imbalance between the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the endogenous antioxidant defence system. Excessive oxidative stress can cause protein and lipid peroxidation, impair DNA, and ultimately result in irreversible cell damage and death (39). It has recently been demonstrated that overexpression of CTRP12 markedly reduces cardiac ROS amount in a rat model of post-myocardial infarction heart failure, and an opposite effect appears upon CTRP12 knockdown (40). This effect is mediated by the inactivation of transforming growth factor-β activated kinase 1 (TAK1)-p38 MAPK/c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) pathway (40). In LPS-stimulated cardiomyocytes, CTRP12 decreases ROS and malondialdehyde levels but increases superoxide dismutase activity by up-regulating nuclear factor E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) expression (41). Another study showed that CTRP12 activates the Nrf2 signaling to alleviate oxidative stress in cardiomyocytes exposed to hypoxia/re-oxygenation (42). Thus, CTRP12 may be a powerful candidate to develop a preventive agent for oxidative stress.

3.5 Cardiomyocyte apoptosis

Apoptosis is a type of programmed cell death manner with characteristic morphological and biochemical alterations. Cell apoptosis plays an important role in regulating many physiological and pathological processes (43–45). CTRP12 was found to repress cardiomyocyte apoptosis through the TAK1-p38 MAPK/JNK pathway in rats with post-myocardial infarction heart failure (40). In cardiomyocytes challenged with hypoxia/re-oxygenation, the incidence of apoptosis is significantly decreased in response to CTRP12 (42). In LPS-treated cardiomyocytes, CTRP12 markedly lowers the number of TUNEL-positive cells and augments the ratio of Bcl-1/Bax in a Nrf2-dependent manner (41). In addition, KLF15 reduces cardiomyocyte apoptosis under the condition of hypoxia-reoxygenation in a CTRP12-dependent manner (46). These data provide direct evidence to indicate an anti-apoptotic effect of CTRP12. Oxidative stress is a well-recognized upstream trigger of apoptosis (47). As mentioned above, CTRP12 contributes to the alleviation of oxidative stress. Therefore, CTRP12-mediated regulation of oxidative stress might contribute to its anti-apoptotic effect. Future research is required to confirm this possibility. Of note, adiponectin has been reported to protect endothelial cells and vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) against apoptosis (48, 49). However, the impact of CTRP12 as an important member of the adiponectin family on vascular cell apoptosis is still largely unknown and needs to be investigated.

4 Role of CTRP12 in CVDs

CVDs are a group of disorders affecting heart and blood vessels and cause a significant global health burden. CTRP12 has been shown to be involved in the occurrence and development of CVDs, such as CAD and heart failure (Figure 3 and Table 1).

Figure 3. Relevance of CTRP12 to cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. Dysregulation of CTRP12 is closely related to the onset and development of cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. In particular, CTRP12 has a protective effect on CAD, heart failure, diabetes and NAFLD. However, CTRP12 plays a dual role in obesity progression, depending on the gender.

4.1 CAD

CAD is the most common cardiovascular disease constituting a severe threat for human health and consists of stable angina, unstable angina, myocardial infarction and sudden cardiac death (50). In recent years, the association of CTRP12 with CAD has gained a great attention. Serum CTRP12 levels in CAD patients are lower than those in healthy individuals and have an independent association with the risk of CAD (30). Another case-control study showed that serum CTRP12 levels are negatively correlated with the severity of CAD (51). Acute coronary syndromes (ACS) are characterized by a sudden reduction in blood supply to the heart and refers to a spectrum of coronary artery pathologies, including ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction and unstable angina (52–54). As a primary health concern, ACS causes a huge economic burden and accounts for more than 1 million hospitalizations annually in the United States (55). A recent study showed that serum CTRP12 levels are significantly decreased in ACS patients as compared to healthy controls, and elevated CTRP12 levels function as an independent protective factor for ACS (56). These data indicate that circulating CTRP12 may possess enormous potential to act as a novel predictor for cardiovascular risk and disease severity.

Cardiomyocyte injury and death are regarded as a key driver for CAD, especially myocardial infarction (57–59). It has been demonstrated that overexpression of CTRP12 alleviates LPS or hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced cardiomyocyte impairment by inhibiting inflammatory response, oxidative stress and cell apoptosis in a Nrf2-dependent manner (41, 42). In a mouse model of myocardial ischemia-reperfusion, the expression levels of KLF15 and CTRP12 are significantly decreased in myocardium (46). Importantly, KLF15 induces CTRP12 transcription to inhibit inflammation and apoptosis, leading to improvement of hypoxia/reoxygenation-caused cell damage in rat myoblast H9c2 cells (46). Thus, targeting CTRP12 may have enormous potential for the prevention and treatment of CAD.

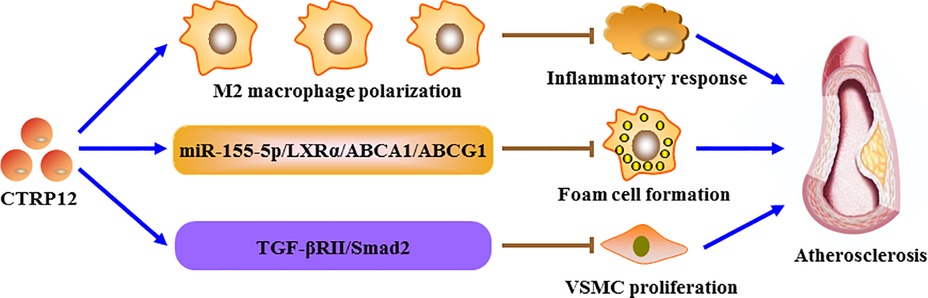

Atherosclerosis is a lipid-driven inflammatory condition affecting large and medium-sized arteries and functions as the pathological basis of CAD (60). As a major cell type within atherosclerotic plaques, macrophages are implicated in all stages of atherosclerosis progression, including plaque formation, calcification, rupture and regression (61). During atherogenesis, monocytes in the blood stream enter the subendothelial space of arterial intima where they differentiate into macrophages. After uptake of abundant lipids, macrophages are transformed into foam cells, the hallmark of early fatty streak lesions (62–64). ATP binding cassette transporter A1 (ABCA1) and G1 (ABCG1) belong to the integral membrane proteins and play a crucial role in promoting the release of intracellular cholesterol and phospholipids. There is increasing evidence that decrease in ABCA1- and ABCG1-dependent cholesterol efflux is a critical contributor to lipid-laden foam cell formation (65–67). Also, macrophage foam cells can secrete a variety of pro-inflammatory cytokines, leading to aggravation of lipid metabolism disorder and atherosclerotic lesion expansion (68, 69). Our group recently demonstrated that overexpression of CTRP12 inhibits macrophage lipid accumulation and inflammatory to protect against atherosclerosis in mice (31). Further studies revealed that CTRP12 activates the miR-155-5p/LXRα signaling pathway, which enhances ABCA1- and ABCG1-dependent cholesterol efflux to inhibit foam cell formation as well as facilitates M2 macrophage polarization to alleviate inflammation (31). In addition, treatment of mouse peritoneal macrophages with recombinant CTRP12 protein down-regulates the expression of TNF-α, IL-6 and MCP-1, and this beneficial effect is reversed by blocking the transforming growth factor-β receptor II (TGF-βRII)/Smad2 signaling pathway (70). It is well known that low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), total cholesterol and triglycerides are the major risk factors for atherosclerosis development, whereas HDL-C is protective against atherogenesis. A 1 mg/dl increase in plasma HDL-C levels is estimated to diminish the risk of CAD in men by 2% and women by 3% (71). A recent study showed that the combination of spinach thylakoid extract with high-intensity functional training reduces plasma LDL-C, total cholesterol and triglyceride levels but elevates HDL-C levels in obese male subjects, which is possibly attributed to the activation of the KLF15/CTRP12 pathway (72). These data suggest that CTRP12 is an adipokine with atheroprotection (Figure 4), and up-regulation of CTRP12 expression could be a useful therapeutic option for atherosclerosis. Like macrophages, VSMCs can be converted to foam cells after accumulation of large amounts of lipids. It has been demonstrated that approximately 50% of total foam cells are VSMC-derived in human coronary atherosclerotic plaques (73). However, it has not yet been determined whether CTRP12 plays a role in the transformation of VSMCs into foam cells.

Figure 4. The role of CTRP12 in atherosclerosis. CTRP12 protects against the development of atherosclerosis through three pathways. Firstly, CTRP12 induces the polarization of macrophages toward a M2 phenotype to alleviate inflammatory response. Secondly, CTRP12 up-regulates the expression of ABCA1 and ABCG1 via the miR-155-5p/LXRα signaling cascade, leading to inhibition of macrophage foam cell formation. Thirdly, CTRP12 attenuates VSMC proliferation by activating the TGF-βRII/Smad2 axis.

Pathological vascular remodeling is a key feature during the progression of various vascular diseases (74, 75). The proliferation and migration of VSMCs is implicated in the pathogenesis of pathological remodeling of the arterial wall, in particular atherosclerosis (76, 77). In mice undergoing wire-induced injury of the femoral artery, deficiency of CTRP12 increases neointimal thickening after vascular injury and proliferative capacity of vascular cells in injured arteries (70). Consistently, CTRP12 significantly decreases platelet-derived growth factor-BB-stimulated proliferation of VSMCs via activation of the TGF-βRII/Smad2 signaling cascade (70). Therefore, prevention of VSMC proliferation is another important mechanism for the atheroprotection of CTRP12. However, the impact of CTRP12 on VSMC migration remains uncompleted and needs to be investigated.

The endothelium, a cellular monolayer located in the blood vessel wall, contributes to the dynamic maintenance of angiogenesis, vascular tone, blood fluidity and permeability. The damage of vascular endothelial cells can result in endothelial dysfunction that is regarded as a critical driver of atherogenesis (78–80). There is increasing evidence that adiponectin is protective against atherosclerosis by alleviating endothelial dysfunction (81, 82). Considering CTRP12 as a paralog of adiponectin, it is highly possible that CTRP12 inhibits the development of atherosclerosis by improving endothelial function. Future studies will be needed to verify this possibility.

4.2 Heart failure

Heart failure, which is an endpoint stage of numerous heart diseases, severely jeopardises the health of a large population across the world (83). Cardiac remodelling, including myocardial hypertrophy and fibrosis, plays a critical role in promoting the occurrence and development of heart failure (84, 85). Myocardial infarction is regarded as the most common cause of heart failure (86). A significant reduction of CTRP12 expression is observed in the hearts of rats with post-myocardial infarction heart failure (40). Moreover, overexpression of CTRP12 improves cardiac function, inhibits cardiac hypertrophy and attenuates cardiac fibrosis by inactivating the TAK1-p38 MAPK/JNK pathway in rats with post-myocardial infarction heart failure (40). Another research revealed that in neonatal rat cardiac fibroblasts stimulated with isoproterenol, CTRP12 prevents the transformation of fibroblasts to myofibroblasts and attenuates the synthesis of extracellular matrix by inhibiting the activation of p38 (87). These authors also found that CTRP12 suppresses cardiac fibrosis and enhances cardiac function in mice injected with isoproterenol by attenuating p38 phosphorylation (87). Thus, targeting CTRP12 could be a novel and promising strategy for the management of heart failure.

Heart failure can be classified into three groups based on the percentage of ejection fraction: heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFmrEF), and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) that is defined as heart failure with an ejection fraction of 50% or higher at diagnosis. HFmrEF can progress into either HFrEF or HFpEF, but its phenotype is dominated by CAD, as in HFrEF (88). HFrEF and HFpEF present with differences in both the development and progression of the disease secondary to changes at the cellular and molecular levels. During the last two decades, the incidence and prevalence of HFrEF were decreasing, whereas those of HFpEF continued to rise in tandem with the increasing age and burdens of obesity, sedentariness and cardiometabolic disorders (89). Nevertheless, the role of CTRP12 in HFpEF remains largely unknown. Future studies in this field might be of great scientific significance and clinical value.

5 Role of CTRP12 in metabolic diseases

It is well known that metabolic diseases, such as diabetes, obesity and NAFLD, are strongly associated with an increased risk of CVDs (90, 91). Similar to CVDs, CTRP12 is also implicated in the physiopathological processes of these metabolic diseases (Figure 3 and Table 1).

5.1 Diabetes

Diabetes is a global disease and has become a public health problem that seriously threatens people's health. Accumulating evidence has demonstrated that adiponectin is closely associated with diabetes (92, 93). Like adiponectin, CTRP12 is involved in the progression of diabetes. The patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus exhibit a marked reduction in serum CTRP12 levels (94). Similar to this report, Du et al. collected 115 type 2 diabetes mellitus patients and 54 healthy subjects and found that serum CTRP12 levels are significantly decreased in diabetic patients compared with healthy controls (36). Polycystic ovary syndrome is regarded as a pro-inflammatory state associated with diabetes. There is a negative correlation between serum CTRP12 concentration and blood glucose levels in women with polycystic ovary syndrome (25, 95). Diabetic nephropathy, a common microvascular complication with a high incidence in diabetic patients, is the major reason for the elevation in mortality of patients (96, 97). These authors also demonstrated that serum CTRP12 levels in diabetic nephropathy patients are lower than those in diabetic patients without diabetic nephropathy and show a negative correlation with diabetes duration, blood urea nitrogen, uric acid and 24-h urinary albumin excretion rate (36). These data suggest that circulating CTRP12 acts as a novel and valuable biomarker for the prediction of renal dysfunction in type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Insulin resistance is a critical feature of diabetes. Treatment with rosiglitazone, an insulin-sensitizing drug, markedly enhances CTRP12 mRNA amount in adipocytes; however, both the mRNA and serum levels of CTRP12 are significantly decreased in insulin-resistant obese (ob/ob) mice (16). An inverse correlation between serum CTRP12 levels and insulin resistance is found in CAD patients (30). Thromboxane A2 (TXA2) is an arachidonic acid-derived eicosanoid synthesized by thromboxane synthase (TBXAS). TXA2 signals through its receptor (TBXA2R) and plays a key role in haemostasis (98). In genetic and dietary mouse models of obesity and diabetes, the expression levels of TBXAS and TBXA2R are significantly increased in adipose tissue (99). Deficiency of TBXAS enhances insulin sensitivity and improves glucose homeostasis in mice fed a low-fat diet, which is correlated with incremental CTRP12 expression (99). Under the condition of high-fat diet, knockout of CTRP12 in male mice leads to a significant increase in fasting blood glucose levels, whereas this indicator is not different between female wild-type and CTRP12-deficient mice, suggesting a sex-dependent effect of CTRP12 on insulin sensitivity (100). Dietary intervention in combination with insulin aspart reduces 2-h postprandial blood glucose levels and improves clinical outcomes in pregnant women with gestational diabetes mellitus, which is partially attributed to increased CTRP12 secretion (101). Collectively, these data indicate that CTRP12 is an insulin-sensitizing adipokine and represents a novel target molecule for the treatment of insulin resistance and diabetes.

5.2 Obesity

Obesity is a well-known metabolic disease. In recent years, obesity and its associated health issues have risen dramatically and become a global challenge. When compared with the normal weight women, the expression levels of CTRP12 mRNA are significantly increased in subcutaneous adipose tissue and visceral adipose tissue isolated from obese women undergoing bariatric surgery (102). Concurrently, there is a significant correlation between CTRP12 expression and obese indices including waist circumference, hip circumference and body mass index (102). Another research showed that diet-induced obese mice have lower plasma CTRP12 levels (27). However, no significant alterations are observed in serum CTRP12 levels between overweight/obese and normal weight subgroups in polycystic ovary syndrome and non-polycystic ovary syndrome women (103). These controversial results suggest whether circulating CTRP12 can serve as a valuable biomarker of obesity needs further investigation. In obese male Wistar rats induced by high-fat diet, aerobic exercise combined with supplementation of the hydroalcoholic extract of Rosa canina fruit seed can effectively reduce body weight and subcutaneous adipose tissue mass by up-regulating irisin and CTRP12 expression (104). When challenged with a high-fat diet, knockout of CTRP12 in male mice leads to a significant increase in weight gain and adiposity, whereas female CTRP12-deficient mice have reduced weight gain (100). These findings reveal a sex-dependent effect of CTRP12 on obesity.

5.3 NAFLD

NAFLD is defined as the presence of steatosis in more than 5% of liver cells with little or no alcohol consumption (105). It contains the benign non-alcoholic fatty liver, and the more severe non-alcoholic steatohepatitis characterized by steatosis, hepatocellular ballooning, lobular inflammation and almost always fibrosis (106–108). Due to the rising prevalence of obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus, NAFLD is becoming the major cause of chronic liver disease worldwide and a growing challenge for public health. Give the important regulatory role of CTRP12 in lipid metabolism and adiposity, it is not surprising that this adipokine is involved in the onset and development of NAFLD. In hepatoma cells and primary mouse hepatocytes, CTRP12 was shown to suppress triglyceride biosynthesis by down-regulating GPAT and DGAT expression (32). In male mice fed a high-fat diet, partial deficiency of CTRP12 leads to more lipid accumulation and greater steatosis in the liver compared with wild-type littermates (33). Therefore, CTRP12 exerts a protective effect on NAFLD, and promoting CTRP12 synthesis could be an effective strategy for reducing NAFLD.

6 Conclusion and future directions

CTRP12 is a newly discovered adipokine and plays an important role in regulating glucose and lipid metabolism, inflammatory response, oxidative stress and cardiomyocyte apoptosis. Importantly, this adipokine has been shown to protect against the occurrence and development of several major cardiovascular and metabolic diseases, including CAD, heart failure, diabetes, obesity and NAFLD. Thus, exogenous administration of CTRP12 or promoting its endogenous production could have considerable promise in the management of these diseases.

Despite significant progress has been made in understanding the role of CTRP12 in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular and metabolic diseases, some concerns still need to be addressed in future studies. CTRP12 is a secreted protein and its receptor is unclear to date. Adiponectin is known to signal through three receptors: T-cadherin, adiponectin receptor 1 (AdipoR1) and AdipoR2 (109). As a G-protein-coupled seven-transmembrane protein, AdipoR1 also acts as the receptor of CTRP1 and CTRP9 (110, 111). Whether this protein is a receptor of CTRP12 needs further investigation. Identification of the specific receptors of CTRP12 will help deeper clarify its mechanisms of action. Given the fact that most of the evidence is limited to the findings of lower plasma CTRP12 concentration in patients as compare to healthy control, more mechanistic studies should be performed to clearly reveal a causal relationship between CTRP12 and cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. Hypertension is a risk factor for early CVDs and is a growing public health problem worldwide. Certain members of CTRPs, such as CTRP1, CTRP3 and CTRP9, have been shown to be associated with hypertension (112–115). It is unclear, however, whether CTRP12 is involved in the development of hypertension. Similar to cell apoptosis, cell pyroptosis is a programmed cell death manner characterized by inflammasome activation and abundant release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (116). Ferroptosis is another type of regulated cell death resulting from lipid peroxidation and iron overload (117, 118). Accumulating evidence has indicated a close association of cell pyroptosis and ferroptosis with the progression of cardiovascular and metabolic diseases (119–122). Nevertheless, the influence of CTRP12 on cell pyroptosis and ferroptosis remains poorly understood and are required to be investigated. Extensive data have demonstrated that several conserved lysine residues in the collagenous domain of adiponectin can be modified by glycosylation and hydroxylation (123, 124). Considering CTRP12 as a paralog of adiponectin, future research should explore the impact of post-translational modifications on CTRP12 structure and functions. To the best of our knowledge, there are no adipokine-targeted drugs available for clinical applications to date. Therefore, development of the drugs targeting adipokines, such as CTRP12, is important to prevent and treat cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. In addition, sterol regulatory element-binding protein 2 and 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase are known to play a crucial role in promoting endogenous cholesterol biosynthesis. Aberrant expression of these two agents is correlated with lipid metabolism disorder and atherogenesis (125–127). To establish further link of CTRP12 to lipid metabolism, it is of great importance to investigate the regulatory effect of CTRP12 on their expression. In summary, CTRP12 is multifunctional adipokine and an emerging player in cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. A more comprehensive understanding of the relationship of CTRP12 with cardiovascular and metabolic diseases will shed light on the development of CTRP12-targeted treatment.

Author contributions

HW: Resources, Writing – original draft. Z-ZZ: Conceptualization, Visualization, Writing – original draft. X-HY: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. D-NL: Conceptualization, Resources, Visualization, Writing – original draft. JM: Conceptualization, Resources, Visualization, Writing – original draft. JZ: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82060086 to X-HY, 82400542 to JZ), Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (2022JJ60050 to Z-ZZ), Research Foundation of Education Bureau of Hunan Province (22B0415 to JZ) and Scientific Research Project of Hunan Provincial Health Commission (W20243007 to JZ).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnote

Abbreviations AdipoR1, adiponectin receptor 1; ABCA1, ATP binding cassette transporter A1; ABCG1, ATP binding cassette transporter G1; CAD, coronary artery disease; CTRPs, C1q tumor necrosis factor-related proteins; DGAT, diacylglycerol acyltransferase; GPAT, glycerophosphate acyltransferase; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HNF4A, hepatocyte nuclear factor 4A; IL, interleukin; IRS-1, insulin receptor substrate; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase; KLF15, krueppel-like factor 15; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; LXRα, liver X receptor α; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; MCP-1, monocyte chemotactic protein-1; MTTP, microsomal triglyceride transfer protein; NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; Nrf2, nuclear factor E2-related factor 2; TAK1, transforming growth factor-β activated kinase 1; TBXAS, thromboxane synthase; TGF-βRII, transforming growth factor-β receptor II; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α; TXA2, thromboxane A2.

References

1. Deprince A, Haas JT, Staels B. Dysregulated lipid metabolism links nafld to cardiovascular disease. Mol Metab. (2020) 42:101092. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2020.101092

2. Chen R, Zhang H, Tang B, Luo Y, Yang Y, Zhong X, et al. Macrophages in cardiovascular diseases: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Signal Transduc Target Ther. (2024) 9(1):130. doi: 10.1038/s41392-024-01840-1

3. Chen Y, Li X, Wang S, Miao R, Zhong J. Targeting iron metabolism and ferroptosis as novel therapeutic approaches in cardiovascular diseases. Nutrients. (2023) 15(3):591. doi: 10.3390/nu15030591

4. Sampson UK, Fazio S, Linton MF. Residual cardiovascular risk despite optimal ldl cholesterol reduction with statins: the evidence, etiology, and therapeutic challenges. Curr Atheroscler Rep. (2012) 14(1):1–10. doi: 10.1007/s11883-011-0219-7

5. Townsend N, Wilson L, Bhatnagar P, Wickramasinghe K, Rayner M, Nichols M. Cardiovascular disease in Europe: epidemiological update 2016. Eur Heart J. (2016) 37(42):3232–45. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw334

6. Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, Chamberlain AM, Chang AR, Cheng S, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2018 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. (2018) 137(12):e67–492. doi: 10.1161/cir.0000000000000558

7. Saklayen MG. The global epidemic of the metabolic syndrome. Curr Hypertens Rep. (2018) 20(2):12. doi: 10.1007/s11906-018-0812-z

8. Zhao S, Kusminski CM, Scherer PE. Adiponectin, leptin and cardiovascular disorders. Circ Res. (2021) 128(1):136–49. doi: 10.1161/circresaha.120.314458

9. Achari AE, Jain SK. Adiponectin, a therapeutic target for obesity, diabetes, and endothelial dysfunction. Int J Mol Sci. (2017) 18(6):1321. doi: 10.3390/ijms18061321

10. Kishore U, Gaboriaud C, Waters P, Shrive AK, Greenhough TJ, Reid KB, et al. C1q and tumor necrosis factor superfamily: modularity and versatility. Trends Immunol. (2004) 25(10):551–61. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.08.006

11. Seldin MM, Tan SY, Wong GW. Metabolic function of the ctrp family of hormones. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. (2014) 15(2):111–23. doi: 10.1007/s11154-013-9255-7

12. Shanaki M, Shabani P, Goudarzi A, Omidifar A, Bashash D, Emamgholipour S. The C1q/tnf-related proteins (ctrps) in pathogenesis of obesity-related metabolic disorders: focus on type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular diseases. Life Sci. (2020) 256:117913. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117913

13. Zhang H, Zhang-Sun ZY, Xue CX, Li XY, Ren J, Jiang YT, et al. Ctrp family in diseases associated with inflammation and metabolism: molecular mechanisms and clinical implication. Acta Pharmacol Sin. (2023) 44(4):710–25. doi: 10.1038/s41401-022-00991-7

14. Enomoto T, Ohashi K, Shibata R, Higuchi A, Maruyama S, Izumiya Y, et al. Adipolin/C1qdc2/Ctrp12 protein functions as an adipokine that improves glucose metabolism. J Biol Chem. (2011) 286(40):34552–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.277319

15. Buzan RD, Firestone D, Thomas M, Dubovsky SL. Valproate-associated pancreatitis and cholecystitis in six mentally retarded adults. J Clin Psychiatry. (1995) 56(11):529–32.7592507

16. Wei Z, Peterson JM, Lei X, Cebotaru L, Wolfgang MJ, Baldeviano GC, et al. C1q/tnf-related protein-12 (Ctrp12), a novel adipokine that improves insulin sensitivity and glycemic control in mouse models of obesity and diabetes. J Biol Chem. (2012) 287(13):10301–15. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.303651

17. Conde J, Scotece M, López V, Gómez R, Lago F, Pino J, et al. Expression and modulation of adipolin/C1qdc2: a novel adipokine in human and murine atdc-5 chondrocyte cell line. Ann Rheum Dis. (2013) 72(1):140–2. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201693

18. Al-Husseini DJ, Saravani M, Nosratzehi S, Akbari H, Shafiei A, Jafari SM. Evaluation of serum ctrp-4 and ctrp-12 levels in Hashimoto’s thyroiditis patients: a comparative analysis with a control group and their correlation with biochemical factors. Iran J Pathol. (2025) 20(1):42–8. doi: 10.30699/ijp.2024.2025001.3276

19. Aslani MR, Amani M, Moghadas F, Ghobadi H. Adipolin and il-6 Serum levels in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Adv Respir Med. (2022) 90(5):391–8. doi: 10.3390/arm90050049

20. Comba C, Ozdemir IA, Demirayak G, Erdogan SV, Demir O, Özlem Yıldız G, et al. The effect of omentectomy on the blood levels of adipokines in obese patients with endometrial cancer. Obes Res Clin Pract. (2022) 16(3):242–8. doi: 10.1016/j.orcp.2022.06.002

21. Enomoto T, Ohashi K, Shibata R, Kambara T, Uemura Y, Yuasa D, et al. Transcriptional regulation of an insulin-sensitizing adipokine adipolin/Ctrp12 in adipocytes by krüppel-like factor 15. PLoS One. (2013) 8(12):e83183. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083183

22. Sue N, Jack BH, Eaton SA, Pearson RC, Funnell AP, Turner J, et al. Targeted disruption of the basic krüppel-like factor gene (Klf3) reveals a role in adipogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. (2008) 28(12):3967–78. doi: 10.1128/mcb.01942-07

23. Bell-Anderson KS, Funnell AP, Williams H, Jusoh M, Scully H, Lim T, et al. Loss of krüppel-like factor 3 (Klf3/bklf) leads to upregulation of the insulin-sensitizing factor adipolin (Fam132a/Ctrp12/C1qdc2). Diabetes. (2013) 62(8):2728–37. doi: 10.2337/db12-1745

24. Tan BK, Lewandowski KC, O'Hare JP, Randeva HS. Insulin regulates the novel adipokine adipolin/Ctrp12: in vivo and ex vivo effects. J Endocrinol. (2014) 221(1):111–9. doi: 10.1530/joe-13-0537

25. Tan BK, Chen J, Adya R, Ramanjaneya M, Patel V, Randeva HS. Metformin increases the novel adipokine adipolin/Ctrp12: role of the ampk pathway. J Endocrinol. (2013) 219(2):101–8. doi: 10.1530/joe-13-0277

26. Wei Z, Lei X, Seldin MM, Wong GW. Endopeptidase cleavage generates a functionally distinct isoform of C1q/tumor necrosis factor-related protein-12 (Ctrp12) with an altered oligomeric state and signaling specificity. J Biol Chem. (2012) 287(43):35804–14. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.365965

27. Enomoto T, Shibata R, Ohashi K, Kambara T, Kataoka Y, Uemura Y, et al. Regulation of adipolin/Ctrp12 cleavage by obesity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. (2012) 428(1):155–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.10.031

28. Stewart AN, Tan SY, Clark DJ, Zhang H, Wong GW. N-Linked glycosylation-dependent and -independent mechanisms regulating Ctrp12 cleavage, secretion, and stability. Biochemistry. (2019) 58(6):727–41. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.8b00528

29. Merino Salvador M, Gómez de Cedrón M, Moreno Rubio J, Falagán Martínez S, Sánchez Martínez R, Casado E, et al. Lipid metabolism and lung cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. (2017) 112:31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2017.02.001

30. Fadaei R, Moradi N, Kazemi T, Chamani E, Azdaki N, Moezibady SA, et al. Decreased Serum levels of Ctrp12/adipolin in patients with coronary artery disease in relation to inflammatory cytokines and insulin resistance. Cytokine. (2019) 113:326–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2018.09.019

31. Wang G, Chen JJ, Deng WY, Ren K, Yin SH, Yu XH. Ctrp12 ameliorates atherosclerosis by promoting cholesterol efflux and inhibiting inflammatory response via the mir-155-5p/lxrα pathway. Cell Death Dis. (2021) 12(3):254. doi: 10.1038/s41419-021-03544-8

32. Tan SY, Little HC, Sarver DC, Watkins PA, Wong GW. Ctrp12 inhibits triglyceride synthesis and export in hepatocytes by suppressing hnf-4α and Dgat2 expression. FEBS Lett. (2020) 594(19):3227–39. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.13895

33. Tan SY, Little HC, Lei X, Li S, Rodriguez S, Wong GW. Partial deficiency of Ctrp12 alters hepatic lipid metabolism. Physiol Genomics. (2016) 48(12):936–49. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00111.2016

34. Wong GW, Krawczyk SA, Kitidis-Mitrokostas C, Ge G, Spooner E, Hug C, et al. Identification and characterization of Ctrp9, a novel secreted glycoprotein, from adipose tissue that reduces Serum glucose in mice and forms heterotrimers with adiponectin. FASEB J. (2009) 23(1):241–58. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-114991

35. Faiz H, Heiston EM, Malin SK. Β-Aminoisobutyric acid relates to favorable glucose metabolism through adiponectin in adults with obesity independent of prediabetes. J Diabetes Res. (2023) 2023:4618215. doi: 10.1155/2023/4618215

36. Du J, Xu J, Wang X, Liu Y, Zhao X, Zhang H. Reduced serum Ctrp12 levels in type 2 diabetes are associated with renal dysfunction. Int Urol Nephrol. (2020) 52(12):2321–7. doi: 10.1007/s11255-020-02591-y

37. Zhao ZW, Zhang M, Liao LX, Zou J, Wang G, Wan XJ, et al. Long non-coding rna Pca3 inhibits lipid accumulation and atherosclerosis through the mir-140-5p/Rfx7/Abca1 axis. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids. (2021) 1866(5):158904. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2021.158904

38. Simion V, Zhou H, Haemmig S, Pierce JB, Mendes S, Tesmenitsky Y, et al. A macrophage-specific lncrna regulates apoptosis and atherosclerosis by tethering hur in the nucleus. Nat Commun. (2020) 11(1):6135. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19664-2

39. Sies H. Oxidative stress: a concept in redox biology and medicine. Redox Biol. (2015) 4:180–3. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2015.01.002

40. Bai B, Ji Z, Wang F, Qin C, Zhou H, Li D, et al. Ctrp12 ameliorates post-myocardial infarction heart failure through down-regulation of cardiac apoptosis, oxidative stress and inflammation by influencing the Tak1-P38 mapk/jnk pathway. Inflammation Res. (2023) 72(7):1375–90. doi: 10.1007/s00011-023-01758-4

41. Zhou MQ, Jin E, Wu J, Ren F, Yang YZ, Duan DD. Ctrp12 ameliorated lipopolysaccharide-induced cardiomyocyte injury. Chem Pharm Bull. (2020) 68(2):133–9. doi: 10.1248/cpb.c19-00646

42. Jin AP, Zhang QR, Yang CL, Ye S, Cheng HJ, Zheng YY. Up-regulation of Ctrp12 ameliorates hypoxia/Re-oxygenation-induced cardiomyocyte injury by inhibiting apoptosis, oxidative stress, and inflammation via the enhancement of Nrf2 signaling. Hum Exp Toxicol. (2021) 40(12):2087–98. doi: 10.1177/09603271211021880

43. Xu X, Lai Y, Hua ZC. Apoptosis and apoptotic body: disease message and therapeutic target potentials. Biosci Rep. (2019) 39(1):BSR20180992. doi: 10.1042/bsr20180992

44. Newton K, Strasser A, Kayagaki N, Dixit VM. Cell death. Cell. (2024) 187(2):235–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2023.11.044

45. Dejas L, Santoni K, Meunier E, Lamkanfi M. Regulated cell death in neutrophils: from apoptosis to netosis and pyroptosis. Semin Immunol. (2023) 70:101849. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2023.101849

46. Liao B, Tian X. Ctrp12 alleviates cardiomyocyte ischemia-reperfusion injury via regulation of Klf15. Mol Med Rep. (2022) 26(1):247. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2022.12763

47. LeFort KR, Rungratanawanich W, Song BJ. Contributing roles of mitochondrial dysfunction and hepatocyte apoptosis in liver diseases through oxidative stress, post-translational modifications, inflammation, and intestinal barrier dysfunction. Cell Mol Life Sci. (2024) 81(1):34. doi: 10.1007/s00018-023-05061-7

48. Zhao HY, Zhao M, Yi TN, Zhang J. Globular adiponectin protects human umbilical vein endothelial cells against apoptosis through adiponectin receptor 1/adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase pathway. Chin Med J. (2011) 124(16):2540–7.21933602

49. Lu Y, Bian Y, Wang Y, Bai R, Wang J, Xiao C. Globular adiponectin reduces vascular calcification via inhibition of er-stress-mediated smooth muscle cell apoptosis. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. (2015) 8(3):2545–54.26045760

50. Malakar AK, Choudhury D, Halder B, Paul P, Uddin A, Chakraborty S. A review on coronary artery disease, its risk factors, and therapeutics. J Cell Physiol. (2019) 234(10):16812–23. doi: 10.1002/jcp.28350

51. Nadimi Shahraki Z, Azimi H, Ilchi N, Rohani Borj M, Pourghadamyari H, Mosallanejad S, et al. Circulating C1q/tnf-related protein-12 levels are associated with the severity of coronary artery disease. Cytokine. (2021) 144:155545. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2021.155545

52. Atwood J. Management of acute coronary syndrome. Emerg Med Clin North Am. (2022) 40(4):693–706. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2022.06.008

53. Bergmark BA, Mathenge N, Merlini PA, Lawrence-Wright MB, Giugliano RP. Acute coronary syndromes. Lancet. (2022) 399(10332):1347–58. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(21)02391-6

54. Nohria R, Antono B. Acute coronary syndrome. Prim Care. (2024) 51(1):53–64. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2023.07.003

55. Makki N, Brennan TM, Girotra S. Acute coronary Syndrome. J Intensive Care Med. (2015) 30(4):186–200. doi: 10.1177/0885066613503294

56. Liu Y, Wei C, Ding Z, Xing E, Zhao Z, Shi F, et al. Role of Serum C1q/tnf-related protein family levels in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2022) 9:967918. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.967918

57. Frangogiannis NG. Pathophysiology of myocardial infarction. Compr Physiol. (2015) 5(4):1841–75. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c150006

58. Farokhian A, Rajabi A, Sheida A, Abdoli A, Rafiei M, Jazi ZH, et al. Apoptosis and myocardial infarction: role of ncrnas and exosomal ncrnas. Epigenomics. (2023) 15(5):307–34. doi: 10.2217/epi-2022-0451

59. Rodríguez M, Lucchesi BR, Schaper J. Apoptosis in myocardial infarction. Ann Med. (2002) 34(6):470–9. doi: 10.1080/078538902321012414

60. Fan J, Watanabe T. Atherosclerosis: known and unknown. Pathol Int. (2022) 72(3):151–60. doi: 10.1111/pin.13202

61. Libby P. Inflammation during the life cycle of the atherosclerotic plaque. Cardiovasc Res. (2021) 117(13):2525–36. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvab303

62. Yu XH, Fu YC, Zhang DW, Yin K, Tang CK. Foam cells in atherosclerosis. Clin Chim Acta. (2013) 424:245–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2013.06.006

63. Chistiakov DA, Melnichenko AA, Myasoedova VA, Grechko AV, Orekhov AN. Mechanisms of foam cell formation in atherosclerosis. J Mol Med (Berl). (2017) 95(11):1153–65. doi: 10.1007/s00109-017-1575-8

64. Galindo CL, Khan S, Zhang X, Yeh YS, Liu Z, Razani B. Lipid-Laden foam cells in the pathology of atherosclerosis: shedding light on new therapeutic targets. Expert Opin Ther Targets. (2023) 27(12):1231–45. doi: 10.1080/14728222.2023.2288272

65. Yu XH, Tang CK. Abca1, Abcg1, and cholesterol homeostasis. Adv Exp Med Biol. (2022) 1377:95–107. doi: 10.1007/978-981-19-1592-5_7

66. Xue H, Chen X, Yu C, Deng Y, Zhang Y, Chen S, et al. Gut microbially produced indole-3-propionic acid inhibits atherosclerosis by promoting reverse cholesterol transport and its deficiency is causally related to atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Circ Res. (2022) 131(5):404–20. doi: 10.1161/circresaha.122.321253

67. Zhao ZW, Zhang M, Zou J, Wan XJ, Zhou L, Wu Y, et al. Tigar mitigates atherosclerosis by promoting cholesterol efflux from macrophages. Atherosclerosis. (2021) 327:76–86. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2021.04.002

68. Bäck M, Yurdagul A, Tabas J, Öörni I, Kovanen PT. Inflammation and its resolution in atherosclerosis: mediators and therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Cardiol. (2019) 16(7):389–406. doi: 10.1038/s41569-019-0169-2

69. Wang XQ, Liu ZH, Xue L, Lu L, Gao J, Shen Y, et al. C1q/tnf-related protein 1 links macrophage lipid metabolism to inflammation and atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. (2016) 250:38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2016.04.024

70. Ogawa H, Ohashi K, Ito M, Shibata R, Kanemura N, Yuasa D, et al. Adipolin/Ctrp12 protects against pathological vascular remodelling through suppression of smooth muscle cell growth and macrophage inflammatory response. Cardiovasc Res. (2020) 116(1):237–49. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvz074

71. Gordon DJ, Probstfield JL, Garrison RJ, Neaton JD, Castelli WP, Knoke JD, et al. High-density lipoprotein cholesterol and cardiovascular disease. Four prospective american studies. Circulation. (1989) 79(1):8–15. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.79.1.8

72. Saeidi A, Motamedi P, Hoteit M, Sadek Z, Ramadan W, Dara MM, et al. Impact of spinach thylakoid extract-induced 12-week high-intensity functional training on specific adipokines in obese males. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. (2024) 21(1):2398467. doi: 10.1080/15502783.2024.2398467

73. Allahverdian S, Chehroudi AC, McManus BM, Abraham T, Francis GA. Contribution of intimal smooth muscle cells to cholesterol accumulation and macrophage-like cells in human atherosclerosis. Circulation. (2014) 129(15):1551–9. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.113.005015

74. Wang X, Khalil RA. Matrix metalloproteinases, vascular remodeling, and vascular disease. Adv Pharmacol. (2018) 81:241–330. doi: 10.1016/bs.apha.2017.08.002

75. Heusch G, Libby P, Gersh B, Yellon D, Böhm M, Lopaschuk G, et al. Cardiovascular remodelling in coronary artery disease and heart failure. Lancet. (2014) 383(9932):1933–43. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(14)60107-0

76. Huynh DTN, Heo KS. Role of mitochondrial dynamics and mitophagy of vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration in progression of atherosclerosis. Arch Pharmacal Res. (2021) 44(12):1051–61. doi: 10.1007/s12272-021-01360-4

77. Chistiakov DA, Orekhov AN, Bobryshev YV. Vascular smooth muscle cell in atherosclerosis. Acta Physiol (Oxf). (2015) 214(1):33–50. doi: 10.1111/apha.12466

78. Gimbrone MA Jr., García-Cardeña G. Endothelial cell dysfunction and the pathobiology of atherosclerosis. Circ Res. (2016) 118(4):620–36. doi: 10.1161/circresaha.115.306301

79. Xu S, Ilyas I, Little PJ, Li H, Kamato D, Zheng X, et al. Endothelial dysfunction in atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases and beyond: from mechanism to pharmacotherapies. Pharmacol Rev. (2021) 73(3):924–67. doi: 10.1124/pharmrev.120.000096

80. Souilhol C, Serbanovic-Canic J, Fragiadaki M, Chico TJ, Ridger V, Roddie H, et al. Endothelial responses to shear stress in atherosclerosis: a novel role for developmental genes. Nat Rev Cardiol. (2020) 17(1):52–63. doi: 10.1038/s41569-019-0239-5

81. Chen X, Zhang H, McAfee S, Zhang C. The reciprocal relationship between adiponectin and lox-1 in the regulation of endothelial dysfunction in apoe knockout mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. (2010) 299(3):H605–12. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01096.2009

82. Cao Y, Tao L, Yuan Y, Jiao X, Lau WB, Wang Y, et al. Endothelial dysfunction in adiponectin deficiency and its mechanisms involved. J Mol Cell Cardiol. (2009) 46(3):413–9. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.10.014

83. Toth PP, Gauthier D. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: strategies for disease management and emerging therapeutic approaches. Postgrad Med. (2021) 133(2):125–39. doi: 10.1080/00325481.2020.1842620

84. Nishida M, Mi X, Ishii Y, Kato Y, Nishimura A. Cardiac remodeling: novel pathophysiological mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. J Biochem. (2024) 176(4):255–62. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvae031

85. McKinsey TA, Foo R, Anene-Nzelu CG, Travers JG, Vagnozzi RJ, Weber N, et al. Emerging epigenetic therapies of cardiac fibrosis and remodelling in heart failure: from basic mechanisms to early clinical development. Cardiovasc Res. (2023) 118(18):3482–98. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvac142

86. Jiang H, Fang T, Cheng Z. Mechanism of heart failure after myocardial infarction. J Int Med Res. (2023) 51(10):3000605231202573. doi: 10.1177/03000605231202573

87. Wang X, Huang T, Xie H. Ctrp12 alleviates isoproterenol induced cardiac fibrosis via inhibiting the activation of P38 pathway. Chem Pharm Bull. (2021) 69(2):178–84. doi: 10.1248/cpb.c19-01109

88. Simmonds SJ, Cuijpers I, Heymans S, Jones EAV. Cellular and molecular differences between hfpef and hfref: a step ahead in an improved pathological understanding. Cells. (2020) 9(1):242. doi: 10.3390/cells9010242

89. Fazio S, Mercurio V, Fazio V, Ruvolo A, Affuso F. Insulin resistance/hyperinsulinemia, neglected risk factor for the development and worsening of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Biomedicines. (2024) 12(4):806. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines12040806

90. Caussy C, Aubin A, Loomba R. The relationship between type 2 diabetes, nafld, and cardiovascular risk. Curr Diab Rep. (2021) 21(5):15. doi: 10.1007/s11892-021-01383-7

91. Targher G, Byrne CD, Tilg H. Nafld and increased risk of cardiovascular disease: clinical associations, pathophysiological mechanisms and pharmacological implications. Gut. (2020) 69(9):1691–705. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-320622

92. Shams HA, Aziz HM, Al-Kuraishy HM. The potential effects of metformin and/or sitagliptin on leptin/adiponectin ratio in diabetic obese patients: a new therapeutic effect. J Pak Med Assoc. (2024) 74(10 (Supple-8)):S241–5. doi: 10.47391/jpma-bagh-16-54

93. Li Y, Yatsuya H, Iso H, Toyoshima H, Tamakoshi K. Inverse relationship of Serum adiponectin concentration with type 2 diabetes Mellitus incidence in middle-aged Japanese workers: six-year follow-up. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. (2012) 28(4):349–56. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2277

94. Bai B, Ban B, Liu Z, Zhang MM, Tan BK, Chen J. Circulating C1q complement/tnf-related protein (ctrp) 1, Ctrp9, Ctrp12 and Ctrp13 concentrations in type 2 diabetes Mellitus: in vivo regulation by glucose. PLoS One. (2017) 12(2):e0172271. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172271

95. Tan BK, Chen J, Hu J, Amar O, Mattu HS, Ramanjaneya M, et al. Circulatory changes of the novel adipokine adipolin/Ctrp12 in response to metformin treatment and an oral glucose challenge in humans. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). (2014) 81(6):841–6. doi: 10.1111/cen.12438

96. Samsu N. Diabetic nephropathy: challenges in pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Biomed Res Int. (2021) 2021:1497449. doi: 10.1155/2021/1497449

97. Qi C, Mao X, Zhang Z, Wu H. Classification and differential diagnosis of diabetic nephropathy. J Diabetes Res. (2017) 2017:8637138. doi: 10.1155/2017/8637138

98. Fontana P, Zufferey A, Daali Y, Reny JL. Antiplatelet therapy: targeting the Txa2 pathway. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. (2014) 7(1):29–38. doi: 10.1007/s12265-013-9529-1

99. Lei X, Li Q, Rodriguez S, Tan SY, Seldin MM, McLenithan JC, et al. Thromboxane synthase deficiency improves insulin action and attenuates adipose tissue fibrosis. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. (2015) 308(9):E792–804. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00383.2014

100. Tan SY, Lei X, Little HC, Rodriguez S, Sarver DC, Cao X, et al. Ctrp12 ablation differentially affects energy expenditure, body weight, and insulin sensitivity in male and female mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. (2020) 319(1):E146–62. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00533.2019

101. Yang N, Guo R, Guo Y, Wei Y, An N. Effects of dietary intervention combined with insulin aspart on Serum nesfatin-1 and Ctrp12 levels and pregnancy outcomes in pregnant women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Medicine (Baltimore). (2023) 102(42):e35498. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000035498

102. Omidifar A, Toolabi K, Rahimipour A, Emamgholipour S, Shanaki M. The gene expression of Ctrp12 but not Ctrp13 is upregulated in both visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue of obese subjects. Diabetes Metab Syndr. (2019) 13(4):2593–9. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2019.07.027

103. Shanaki M, Moradi N, Fadaei R, Zandieh Z, Shabani P, Vatannejad A. Lower circulating levels of Ctrp12 and Ctrp13 in polycystic ovarian syndrome: irrespective of obesity. PLoS One. (2018) 13(12):e0208059. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0208059

104. Taherzadeh S, Rasoulian B, Khaleghi M, Rashidipour M, Mogharnasi M, Kaeidi A. Anti-Obesity effects of aerobic exercise along with Rosa Canina seed extract supplementation in rats: the role of irisin and adipolin. Obes Res Clin Pract. (2023) 17(3):218–25. doi: 10.1016/j.orcp.2023.04.006

105. Sanyal AJ, Brunt EM, Kleiner DE, Kowdley KV, Chalasani N, Lavine JE, et al. Endpoints and clinical trial design for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. (2011) 54(1):344–53. doi: 10.1002/hep.24376

106. Cobbina E, Akhlaghi F. Non-Alcoholic fatty liver disease (nafld)—pathogenesis, classification, and effect on drug metabolizing enzymes and transporters. Drug Metab Rev. (2017) 49(2):197–211. doi: 10.1080/03602532.2017.1293683

107. Younossi ZM. Non-Alcoholic fatty liver disease—a global public health perspective. J Hepatol. (2019) 70(3):531–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.10.033

108. Tilg H, Adolph TE, Dudek M, Knolle P. Non-Alcoholic fatty liver disease: the interplay between metabolism, microbes and immunity. Nat Metab. (2021) 3(12):1596–607. doi: 10.1038/s42255-021-00501-9

109. Iwabu M, Okada-Iwabu M, Yamauchi T, Kadowaki T. Adiponectin/adiponectin receptor in disease and aging. NPJ Aging Mech Dis. (2015) 1:15013. doi: 10.1038/npjamd.2015.13

110. Gu Y, Hu X, Ge PB, Chen Y, Wu S, Zhang XW. Ctrp1 aggravates cardiac dysfunction post myocardial infarction by modulating Tlr4 in macrophages. Front Immunol. (2021) 12:635267. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.635267

111. Zhang P, Huang C, Li J, Li T, Guo H, Liu T, et al. Globular Ctrp9 inhibits oxldl-induced inflammatory response in raw 264.7 macrophages via ampk activation. Mol Cell Biochem. (2016) 417(1-2):67–74. doi: 10.1007/s11010-016-2714-1

112. Han S, Jeong AL, Lee S, Park JS, Buyanravjikh S, Kang W, et al. C1q/tnf-Α-related protein 1 (Ctrp1) maintains blood pressure under dehydration conditions. Circ Res. (2018) 123(5):e5–19. doi: 10.1161/circresaha.118.312871

113. Deng W, Li C, Zhang Y, Zhao J, Yang M, Tian M, et al. Serum C1q/tnf-related protein-3 (Ctrp3) levels are decreased in obesity and hypertension and are negatively correlated with parameters of insulin resistance. Diabetol Metab Syndr. (2015) 7:33. doi: 10.1186/s13098-015-0029-0

114. Zhou Q, Cheng W, Wang Z, Liu J, Han J, Wen S, et al. C1q/tnf-related protein-9 is elevated in hypertension and associated with the occurrence of hypertension-related atherogenesis. Cell Biol Int. (2021) 45(5):989–1000. doi: 10.1002/cbin.11542

115. Li Y, Geng X, Wang H, Cheng G, Xu S. Ctrp9 ameliorates pulmonary arterial hypertension through attenuating inflammation and improving endothelial cell survival and function. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. (2016) 67(5):394–401. doi: 10.1097/fjc.0000000000000364

116. Yu P, Zhang X, Liu N, Tang L, Peng C, Chen X. Pyroptosis: mechanisms and diseases. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy. (2021) 6(1):128. doi: 10.1038/s41392-021-00507-5

117. Jiang X, Stockwell BR, Conrad M. Ferroptosis: mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. (2021) 22(4):266–82. doi: 10.1038/s41580-020-00324-8

118. Tang D, Chen X, Kang R, Kroemer G. Ferroptosis: molecular mechanisms and health implications. Cell Res. (2021) 31(2):107–25. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-00441-1

119. Guo W, Huang R, Bian J, Liao Q, You J, Yong X, et al. Salidroside ameliorates macrophages lipid accumulation and atherosclerotic plaque by inhibiting hif-1α-induced pyroptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. (2025) 742:151104. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2024.151104

120. Feng H, Wu T, Chin J, Ding R, Long C, Wang G, et al. Tangzu granule alleviate neuroinflammation in diabetic peripheral neuropathy by suppressing pyroptosis through P2x7r/Nlrp3 signaling pathway. J Ethnopharmacol. (2025) 337(Pt 1):118792. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2024.118792

121. Du J, Zhu X, Zhang Y, Huang X, Wang X, Yang F, et al. Ctrp13 attenuates atherosclerosis by inhibiting endothelial cell ferroptosis via activating Gch1. Int Immunopharmacol. (2024) 143(Pt 3):113617. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2024.113617

122. Meng W, Li L. N6-Methyladenosine modification of spop relieves ferroptosis and diabetic cardiomyopathy by enhancing ubiquitination of Vdac3. Free Radic Biol Med. (2025) 226:216–29. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2024.11.025

123. Wang Y, Lam KS, Yau MH, Xu A. Post-Translational modifications of adiponectin: mechanisms and functional implications. Biochem J. (2008) 409(3):623–33. doi: 10.1042/bj20071492

124. Chen X, Yuan Y, Wang Q, Xie F, Xia D, Wang X, et al. Post-Translational modification of adiponectin affects lipid accumulation, proliferation and migration of vascular smooth muscle cells. Cell Physiol Biochem. (2017) 43(1):172–81. doi: 10.1159/000480336

125. Yu H, Rimbert A, Palmer AE, Toyohara T, Xia Y, Xia F, et al. Gpr146 deficiency protects against hypercholesterolemia and atherosclerosis. Cell. (2019) 179(6):1276–88.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.10.034

126. Hou C, Jiang X, Sheng W, Zhang Y, Lin Q, Hong S, et al. Xinmaikang (Xmk) tablets alleviate atherosclerosis by regulating the Srebp2-mediated Nlrp3/asc/caspase-1 signaling pathway. J Ethnopharmacol. (2024) 319(Pt 2):117240. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2023.117240

Keywords: coronary artery disease, CTRP12, diabetes, heart failure, obesity

Citation: Wan H, Zhang Z-Z, Yu X-H, Liu D-N, Min J and Zou J (2026) CTRP12 in cardiovascular and metabolic diseases: current status and future perspective. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 13:1749963. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2026.1749963

Received: 19 November 2025; Revised: 28 December 2025;

Accepted: 13 January 2026;

Published: 4 February 2026.

Edited by:

Yun Fang, The University of Chicago, United StatesReviewed by:

Xia Lei, Oklahoma State University, United StatesKarsten Grote, University of Marburg, Germany

Copyright: © 2026 Wan, Zhang, Yu, Liu, Min and Zou. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jin Zou, em91amluamluMTExM0AxNjMuY29t

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Huan Wan

Huan Wan Zi-Zhen Zhang2,†

Zi-Zhen Zhang2,† Xiao-Hua Yu

Xiao-Hua Yu