Abstract

Background:

Barth syndrome is an X-linked disorder characterised by cardiomyopathy, growth abnormalities, neutropenia, and 3-methylglutaconic aciduria. It is caused by pathogenic variants in TAFAZZIN, which encodes a mitochondrial protein essential for cardiolipin remodelling. In this study, we describe the case of a patient with Barth syndrome in whom initial research genetic testing missed a 5' untranslated region deletion in TAFAZZIN that was later identified through a phenotype-guided reanalysis of exome sequencing data.

Case presentation:

A male infant presented with dilated cardiomyopathy at 7 months of age and underwent cardiac transplantation at 19 months. Initial comprehensive cardiac genetic testing was indeterminate. Subsequent clinical investigations recorded a slight increase in the levels of 3-methylglutaconic acid and intermittent neutropenia, and a history of intermittent neutropenia was noted in his mother and maternal grandmother, prompting a consideration of Barth syndrome. A reanalysis of exome sequencing data identified a hemizygous 116 base pair deletion spanning the 5' untranslated region and start codon of TAFAZZIN. An RNA analysis from the proband's cardiac tissue amplified truncated TAFAZZIN transcripts, and Western blotting confirmed the complete loss of full-length protein, consistent with the loss of the start codon and failure of translation initiation from a downstream in-frame methionine.

Conclusion:

We report a novel 116 bp TAFAZZIN deletion that prevents protein expression due to the loss of the canonical start codon. This case highlights the importance of including non-coding regions in genetic analysis and the diagnostic value of phenotype-guided reanalysis of genetic test data.

Introduction

Barth syndrome (OMIM #302060) is a rare, life-threatening, X-linked recessive disorder characterised by cardiomyopathy, growth abnormalities, neutropenia, and elevated levels of 3-methylglutaconic acid (1). Affected individuals typically present with cardiomyopathy within the first year of life, often leading to heart failure and requiring heart transplantation (2). A delay from initial presentation to diagnosis of Barth syndrome is not uncommon (3). Symptoms are typically managed with diuretics, antiarrhythmics, and beta blockers (3).

Loss-of-function (LoF) variants in the TAFAZZIN gene, leading to reduced or absent enzymatic activity of the encoded TAFAZZIN protein, are the primary cause of Barth syndrome (4). TAFAZZIN is located on chromosome Xq28, with a full-length transcript comprised of 11 exons (G4.5, NM_000116.5). TAFAZZIN is a transacylase responsible for the remodelling of monolysocardiolipin (MLCL) to cardiolipin (CL) in the mitochondria (5). Cardiolipin is a phospholipid that is crucial for maintaining mitochondrial homeostasis by providing structural integrity to the inner mitochondrial membrane and supporting respiratory chain complex function during cellular respiration (6, 7). Disruption to the remodelling of CL leads to the accumulation of MLCL (8, 9). Therefore, clinically suspected Barth syndrome is typically confirmed through genetic testing for variants in TAFAZZIN and a biochemical analysis of the MLCL:CL ratio (10). Defective TAFAZZIN function and reduced CL levels alter the mitochondrial structure and hinder respiratory chain complex formation and function, although how this influences disease progression is relatively unknown (6, 7, 11).

In this study, we report the case of an infant with dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) who underwent an indeterminate comprehensive cardiac genetic test, including TAFAZZIN. Subsequent development of neutropenia and 3-methylglutaconic aciduria prompted a reanalysis of genetic test data, which identified a 116 bp deletion from the 5' untranslated region (UTR) to the start codon of TAFAZZIN. RNA and protein analyses using explanted heart tissue from the proband confirmed the expression of truncated TAFAZZIN mRNA and the absence of full-length TAFAZZIN protein. Our case highlights the importance of including non-coding gene regions in genetic testing and the value of phenotype-guided genetic analysis.

Patient and methods

The proband was recruited from The Children's Hospital at Westmead, Sydney, Australia. The parents provided written informed consent for a genetic testing (HREC Project Number 32092) and functional evaluation of heart tissue (HREC Project Number 38192), which were carried out in accordance with the ethics protocols approved by the Royal Children's Hospital Melbourne Human Research Ethics Committee. The parents provided written consent for the publication of a clinical case report.

Cardiac genetic testing

Exome sequencing was performed on DNA extracted from fresh peripheral blood of the proband using previously published methods (12). Analysis was limited to rare variants in 202 genes associated with childhood-onset cardiomyopathy, as previously described in detail (12). A manual inspection of TAFAZZIN sequencing reads was performed using the Integrative Genomics Viewer, v.2.19.1 (13).

Segregation analysis

DNA was extracted from fresh peripheral blood of the proband's parents, as previously described (12). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification across the TAFAZZIN deletion interval was performed using the GoTaq® Flexi DNA polymerase kit (Promega, Wisconsin, USA), with 40 ng DNA, 8% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and the following primer pair that was annealed at 60 °C for 35 PCR cycles: forward 5'-CTCCCCAGTGACGAGAGAGC and reverse 5'-GGTCCAGAAGCAGCTGTAGG. PCR products were resolved on an agarose gel.

Human heart tissue

Left ventricular tissue of the proband, immediately snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen at surgical removal, was obtained from The Melbourne Tissue Heart Bank, Melbourne, Australia (HREC 38192). Control myectomy samples from adults aged between 21 and 55 years at the time of sample collection were obtained from the Sydney Heart Bank (14).

RNA extraction and reverse transcription-PCR amplification

RNA was extracted from 20 µg snap-frozen myectomy tissue using 1 mL of TRIzol™ reagent (Life Technologies, California, USA), reverse-transcribed using random hexamers (Thermo Fisher, Massachusetts, USA), and PCR-amplified as previously published (15). The following are the PCR primers that were annealed in the 5' UTR and exon 3 of TAFAZZIN (NM_000116.5): forward 5'-CTCCCCAGTGACGAGAGAGC and reverse 5'-ACGCATCAACTTCAGGTTCC. PCR products were purified using Exonuclease I and Antarctic Phosphatase (New England Biolabs, Massachusetts, USA), resolved on an agarose gel resolved, and extracted using the NucleoSpin® Gel and PCR Clean-up kit (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany). Sanger sequencing was performed at Macrogen, Inc. (Seoul, South Korea) and electropherograms were analysed using Sequencher v.5.4.6 (Gene Codes, Michigan, USA).

Protein extraction and Western blotting

Fifty micrograms of snap-frozen left ventricular tissue was homogenised in the Pierce™ RIPA Buffer (Thermo Fisher) containing PhosSTOP™ (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) and cOmplete™, Mini, EDTA-free Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Roche), using a Polytron PT 2100 homogeniser (Kinematica, Lucerne, Switzerland). Protein extraction and Western blot analysis was performed as previously published (16). The Western membrane was stained post-transfer with Ponceau S Red (Sigma-Aldrich) and horizontally cut at approximately 50 kDa, relative to the PageRuler™ Plus Prestained Protein Ladder loaded onto a NuPAGE™ 4%–12% Bis-Tris Protein Gels, 1.5 mm, 15-well (Thermo Fisher), with the 1X 3-morpholinopropane-1-sulfonic acid (MOPS) running buffer, prior to blocking in 5% skim milk powder in phosphate buffered saline with tween (PBS-T). The anti-MYBPC3 monoclonal antibody (1:1,000, Abcam, ab108522) was hybridised in the upper half of the membrane and the anti-TAFAZZIN monoclonal antibody (1:1,000, Abcam, ab307148) was hybridised in the lower half of the membrane in 5% BSA in PBS-T. The goat anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugate (1:10,000, Invitrogen, G21234) secondary antibody was hybridised in 5% skim milk powder in PBS-T.

Results

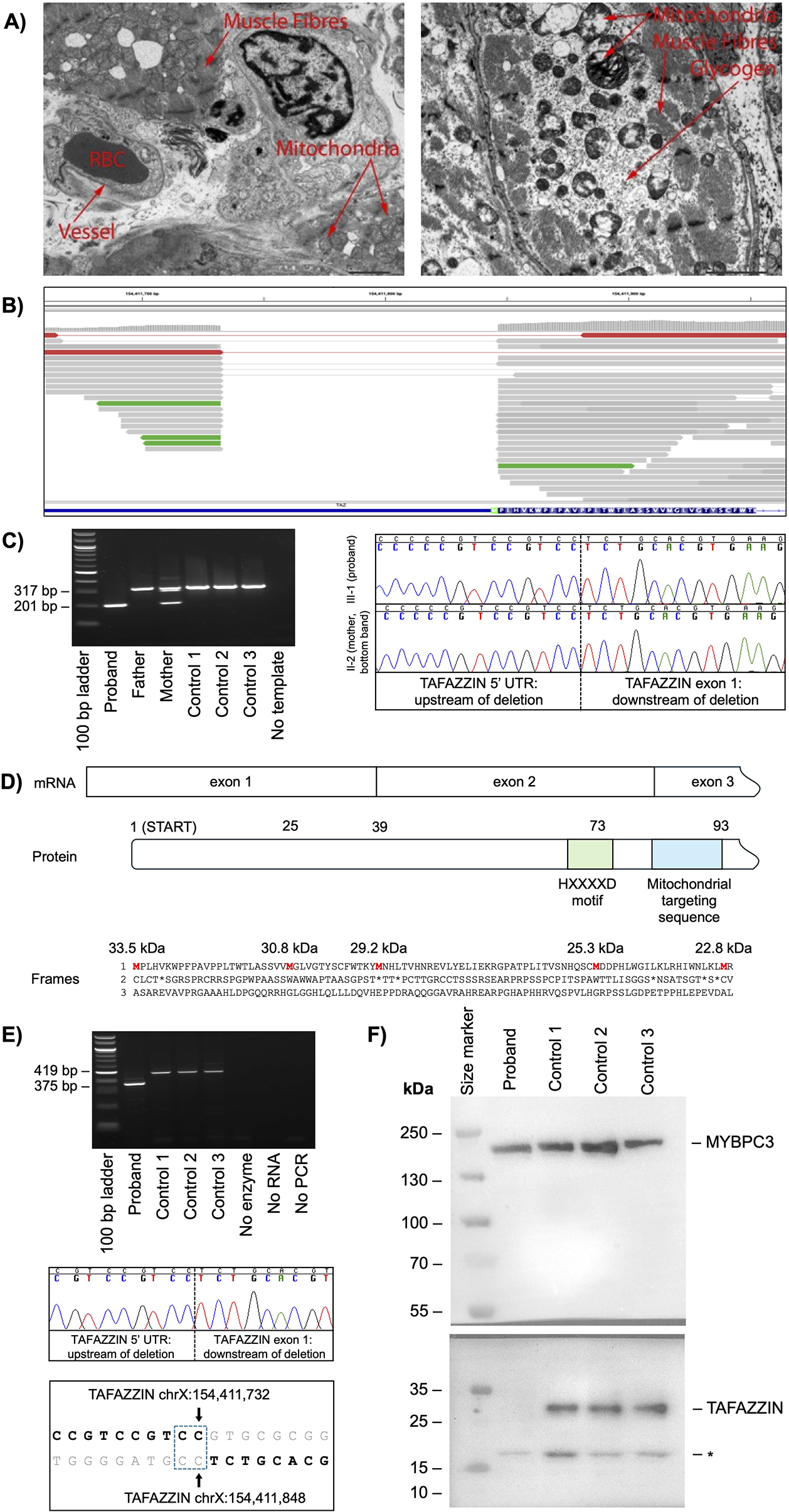

The male proband presented with cough, coryza, poor feeding, and increased work of breathing. A chest X-ray showed cardiomegaly and an echocardiogram showed a severely hypocontractile left ventricle with impaired systolic function and a dilated left atrium. He was diagnosed with DCM at 7 months of age and he developed progressive congestive heart failure (NYHA Class IV) with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 26%. He was initially managed with diuretics, a beta-blocker, angoitensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor, and continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) respiratory support but later received a ventricular assist device implant before undergoing a cardiac transplantation at the age of 19 months. A histology of myocardial tissue retrieved at the time of the ventricular assist device implant showed mild interstitial fibrosis, perivascular lymphocytes, plasma cells in the epicardium and subepicardial zones, and endocardial fibroelastosis, consistent with his clinical diagnosis of DCM. Electron microscopy of myocardial tissue did not show obvious myocytes or mitochondrial abnormalities (Figure 1A).

Figure 1

5' untranslated region deletion in TAFAZZIN causes the loss of full-length TAFAZZIN. (A) Electron microscopy of explanted heart tissue of the proband. Images show no obvious increase in the number of mitochondria or a conspicuous irregularity in the arrangement of cristae. Glycogen particles are normal in amount and appearance. Contractile elements of the myocytes show no obvious abnormality. RBC, red blood cell; scale bar, 2.0 μm. (B) Exome sequencing alignments mapped to TAFAZZIN highlighting a deletion in the 5' untranslated region and start codon (green box). (C) PCR (left panel) and Sanger sequencing (right panel) confirming a maternally inherited 116 bp genomic deletion in TAFAZZIN. (D) A schematic showing the beginning of the TAFAZZIN mRNA exon structure (top), with the amino acid number of all AUGs indicated (middle) and the protein sequence across all three frames with the calculated molecular weights of proteins commencing at all theoretical methionine residues in red (bottom). (E) RT-PCR (upper panel) and Sanger sequencing (middle panel) confirmed the 116 bp deletion in TAFAZZIN transcripts, with the breakpoint junction sequences (bold sequence, lower panel) showing a region of microhomology (blue stippled box). (F) Western blot confirming the absence of TAFAZZIN in the proband, with MYBPC3 loading control. The PageRuler™ Plus Prestained Protein Ladder was used as the marker, with molecular weights shown in kilodaltons (kDa). The asterisk (*) indicates an unconfirmed protein band. Bp, base pair; UTR, untranslated region.

An exome-based analysis of a comprehensive 202 cardiac disease gene panel, including TAFAZZIN, did not identify a genetic cause of cardiomyopathy (12). The proband’s family was of European ancestry and there was no history of cardiomyopathy or Barth syndrome.

The proband subsequently developed occasional muscle fatigue and recorded slightly elevated levels of 3-methylglutaconic acid and intermittent neutropenia consistent with a diagnosis of Barth syndrome. This clinical diagnosis prompted a manual re-inspection of available exome sequencing data across TAFAZZIN and revealed a hemizygous 116 bp deletion of the 5' UTR and start codon; chrX(GRCh38):g.154411733-154411848del; NM_000116.5(TAZ):c.-111_5del (Figure 1B). This deletion was missed during initial genetic testing because only three base pairs fell on the edge of the coding regions that were the target of the deletion analysis. A segregation analysis revealed that the deletion was maternally inherited (Figure 1C).

The TAFAZZIN deletion had uncertain clinical significance due to its unknown impact on transcription of the gene, and an in-frame methionine 24 amino acid residues downstream of the start codon might initiate the translation of a slightly shorter, potentially functional protein (Figure 1D). To determine the impact of the deletion on transcription, RNA was extracted from the heart tissue of the proband and three control hearts. RT-PCR amplification of TAFAZZIN transcripts with a 116 bp deletion in the proband and full-length transcripts in the control hearts confirmed that the TAFAZZIN promoter was still intact and able to support transcription (Figure 1E).

To determine whether the translation of TAFAZZIN is initiated from an alternative start site, protein was isolated from the proband's explanted heart tissue and three myectomy control hearts. A Western blot analysis showed no full-length TAFAZZIN protein in the proband's heart tissue compared with controls (Figure 1F). One small protein band of approximately 17 kDa was observed in all samples, but this did not correspond to the mass of any known TAFAZZIN protein isoform. We concluded that the loss of the canonical translation start site led to the complete loss of full-length TAFAZZIN without any expression of a truncated isoform, i.e., a protein LoF consistent with Barth syndrome.

We classified the deletion using the 2015 American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics/Association for Molecular Pathology (ACMG/AMP) variant classification framework in combination with the PVS1 decision tree for LoF variants (17, 18). The deletion is absent in the gnomAD general population database (PM2); the phenotype is highly specific for TAFAZZIN-related Barth syndrome (PP4); the deletion results in a start loss and the altered region plays a critical role, as demonstrated by no detectable full-length TAFAZZIN protein (PVS1_strong), supporting a likely pathogenic classification that was confirmed by a clinical genomics test. A similar deletion that removes the first 36 amino acids of TAZAFFIN (NM_000116.3 c.−72_109+51del) was found in a boy with Barth syndrome (19). The deletion in our proband also overlaps the first intron of DNASE1L1 (NM_001009932.3), encoded on the reverse DNA strand. The deletion classifies as a rare variant with respect to DNASE1L1, as the gene currently has no definitive role in a Mendelian disorder.

Discussion

We report a novel, likely pathogenic, 116 bp maternally inherited deletion spanning the 5' UTR and start codon of TAFAZZIN in an infant with Barth syndrome. In a registry report of 73 patients with Barth syndrome, 48 (66%) presented with cardiomyopathy within the first year of life, yet the mean age at clinical diagnosis of Barth syndrome was 4.0 ± 5.5 years due to diagnostic delays (2). Our proband presented with DCM in infancy, progressing to heart failure requiring cardiac transplantation. Initial research genetic testing missed the deletion in TAFAZZIN that would have confirmed Barth syndrome. This was attributed to the deletion location in the upstream non-coding region of the gene, with only the ATG start codon part of intervals analysed for deletions. To avoid such false negatives, genetic testing intervals should include all transcribed gene regions, including upstream and downstream untranslated regions. A histology of explanted heart tissue did not identify characteristic mitochondrial enlargement and disarrayed cristae, despite severe cardiomyopathy. This may be attributed to the young age of the proband at the time of sample collection. Disease progression raised a clinical suspicion of Barth syndrome for which he was treated accordingly for 2 years. A manual re-inspection of the exome sequencing data revealed the short deletion in the non-coding 5'UTR of TAFAZZIN, confirming this diagnosis and highlighting the value of phenotype-driven genetic testing. The confirmation of Barth syndrome caused by a deletion in TAFAZZIN has enabled genetic screening to be offered to family members and the option of future reproductive options in female carriers.

Pathogenic variants leading to TAFAZZIN deficiency include nonsense, splice site, missense, and partial or full gene deletions. Partial deletions can offer insights into essential functional elements within a gene. In our proband, the deletion maintained transcriptional activity, indicating that the deleted region is not essential for RNA expression. Full-length TAFAZZIN is encoded by 11 exons, with multiple isoforms due to alternative splicing of exons 5 to 7, as well as two reported translational start sites, located in exons 1 and 3 (4). We did not detect truncated TAFAZZIN initiated from an alternative ATG start codon in our proband or in control hearts. Since the TAFAZZIN antibody epitope sequence is proprietary protected, we cannot rule out the possibility that a truncated protein exists to which the antibody does not bind. Previous studies in Saccharomyces cerevisiae showed that only full-length TAFAZZIN and an isoform lacking exon 5 retained catalytic activity and isoforms translated from the downstream AUG codon lacked functional activity (20). Therefore, deletion of the canonical start codon in our proband prevents the expression of catalytically active TAFAZZIN. An analysis of the breakpoint junction sequences revealed that the deletion likely occurred because of non-homologous end-joining in a GC-rich region with 2 base pair microhomology (Figure 1E). A similar mechanism reportedly explains a different deletion that encompasses the entire first exon of TAFAZZIN, NM_000116.3:c.-72_109+51del (19). Recombination between misaligned Alu elements is another common mediator of large partial and whole gene deletions in TAFAZZIN. Two such examples are a 13.7 kb whole TAFAZZIN gene deletion, with AluSx and AluSq repeat homologies found at the breakpoints in a person with severe cardiomyopathy and neutropenia (21), and a 9.9 kb deletion of the first five exons of TAFAZZIN at AluY and AluSx sequences in an individual with Barth syndrome, DCM, intermittent neutropenia, and lactic acidosis (19). There is no correlation between disease severity and TAFAZZIN variant class in Barth syndrome (2, 22).

This study is not without limitations. Control myocardial tissue for Western blot analysis was obtained from adult females, and we did not quantify the TAFAZZIN transcripts; therefore, the deletion may have impacted TAFAZZIN mRNA expression levels.

In summary, we report the case of a patient with Barth syndrome with progressive disease requiring heart transplantation due to a novel small deletion affecting the start codon of TAFAZZIN, providing further evidence of LoF variants in Barth syndrome. We demonstrated that the loss of the translation start site led to the loss of full-length TAFAZZIN without the initiation of translation from an in-frame downstream methionine. Our study emphasises the need for a careful analysis of coding and non-coding regions of TAFAZZIN during genetic testing on the suspicion of Barth syndrome.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because it would not be in accordance with the ethical consent provided by the participant on the use of confidential and identifiable human genetic data and would compromise the anonymity of the participant given this is a case report of one individual. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Royal Children's Hospital Melbourne Human Research Ethics Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardians/next of kin. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s), and minor(s)' legal guardian/next of kin, for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

ES: Validation, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – original draft. JS: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. RL: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Investigation. AM: Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Writing – original draft. SL: Writing – review & editing, Resources, Writing – original draft. CI: Writing – original draft, Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. CC: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Writing – original draft. IK: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. RW: Writing – original draft, Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. RB: Project administration, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Data curation, Investigation.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. RB is the recipient of an NSW Health Cardiovascular Disease Senior Scientist Grant. ES is supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) Scholarship. The funders played no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, and interpretation of data or in the writing of this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jessica Ng and Dr. Megan McKinnon, Royal Children's Hospital, Melbourne, Australia, for providing electron microscopy services, and Randwick Genomics Laboratory, Prince of Wales Hospital Sydney, Australia, for diagnostic confirmation of the TAFFAZIN deletion.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence, and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors, wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Kelley RI Cheatham JP Clark BJ Nigro MA Powell BR Sherwood GW et al X-linked dilated cardiomyopathy with neutropenia, growth retardation, and 3-methylglutaconic aciduria. J Pediatr. (1991) 119(5):738–47. 10.1016/S0022-3476(05)80289-6

2.

Roberts AE Nixon C Steward CG Gauvreau K Maisenbacher M Fletcher M et al The Barth syndrome registry: distinguishing disease characteristics and growth data from a longitudinal study. Am J Med Genet A. (2012) 158A(11):2726–32. 10.1002/ajmg.a.35609

3.

Clarke SLN Bowron A Gonzalez IL Groves SJ Newbury-Ecob R Clayton N et al Barth syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. (2013) 8(1):23. 10.1186/1750-1172-8-23

4.

Bione S D'Adamo P Maestrini E Gedeon AK Bolhuis PA Toniolo D . A novel X-linked gene, G4.5. Is responsible for Barth syndrome. Nat Genet. (1996) 12(4):385–9. 10.1038/ng0496-385

5.

Xu Y Malhotra A Ren M Schlame M . The enzymatic function of Tafazzin*. J Biol Chem. (2006) 281(51):39217–24. 10.1074/jbc.M606100200

6.

Bissler JJ Tsoras M Göring HHH Hug P Chuck G Tombragel E et al Infantile dilated X-linked cardiomyopathy, G4.5 mutations, altered lipids, and ultrastructural malformations of mitochondria in heart, liver, and skeletal muscle. Lab Invest. (2002) 82(3):335–44. 10.1038/labinvest.3780427

7.

McKenzie M Lazarou M Thorburn DR Ryan MT . Mitochondrial respiratory chain supercomplexes are destabilized in Barth syndrome patients. J Mol Biol. (2006) 361(3):462–9. 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.06.057

8.

Schlame M Kelley RI Feigenbaum A Towbin JA Heerdt PM Schieble T et al Phospholipid abnormalities in children with Barth syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2003) 42(11):1994–9. 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.06.015

9.

Valianpour F Mitsakos V Schlemmer D Towbin JA Taylor JM Ekert PG et al Monolysocardiolipins accumulate in Barth syndrome but do not lead to enhanced apoptosis. J Lipid Res. (2005) 46(6):1182–95. 10.1194/jlr.M500056-JLR200

10.

Houtkooper RH Rodenburg RJ Thiels C Lenthe H Stet F Poll-The BT et al Cardiolipin and monolysocardiolipin analysis in fibroblasts, lymphocytes, and tissues using high-performance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry as a diagnostic test for Barth syndrome. Anal Biochem. (2009) 387(2):230–7. 10.1016/j.ab.2009.01.032

11.

Dudek J Cheng IF Balleininger M Vaz FM Streckfuss-Bömeke K Hübscher D et al Cardiolipin deficiency affects respiratory chain function and organization in an induced pluripotent stem cell model of Barth syndrome. Stem Cell Res. (2013) 11(2):806–19. 10.1016/j.scr.2013.05.005

12.

Bagnall RD Singer ES Wacker J Nowak N Ingles J King I et al Genetic basis of childhood cardiomyopathy. Circ Genom Precis Med. (2022) 15(6):e003686. 10.1161/CIRCGEN.121.003686

13.

Thorvaldsdóttir H Robinson JT Mesirov JP . Integrative genomics viewer (Igv): high-performance genomics data visualization and exploration. Brief Bioinform. (2013) 14(2):178–92. 10.1093/bib/bbs017

14.

Dos Remedios CG Lal SP Li A McNamara J Keogh A Macdonald PS et al The Sydney heart bank: improving translational research while eliminating or reducing the use of animal models of human heart disease. Biophys Rev. (2017) 9(4):431–41. 10.1007/s12551-017-0305-3

15.

Singer ES Crowe J Holliday M Isbister JC Lal S Nowak N et al The burden of splice-disrupting variants in inherited heart disease and unexplained sudden cardiac death. NPJ Genom Med. (2023) 8(1):29. 10.1038/s41525-023-00373-w

16.

Holliday M Singer ES Ross SB Lim S Lal S Ingles J et al Transcriptome sequencing of patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy reveals novel splice-altering variants in Mybpc3. Circ Genom Precis Med. (2021) 14(2):183–91. 10.1161/circgen.120.003202

17.

Richards S Aziz N Bale S Bick D Das S Gastier-Foster J et al Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. (2015) 17(5):405–23. 10.1038/gim.2015.30

18.

Abou Tayoun AN Pesaran T DiStefano MT Oza A Rehm HL Biesecker LG et al Recommendations for interpreting the loss of function Pvs1 Acmg/Amp variant criterion. Hum Mutat. (2018) 39(11):1517–24. 10.1002/humu.23626

19.

Ferri L Donati MA Funghini S Cavicchi C Pensato V Gellera C et al Intra-individual plasticity of the Taz gene leading to different heritable mutations in siblings with Barth syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet. (2015) 23(12):1708–12. 10.1038/ejhg.2015.50

20.

Vaz FM Houtkooper RH Valianpour F Barth PG Wanders RJA . Only one splice variant of the human Taz gene encodes a functional protein with a role in cardiolipin metabolism*. J Biol Chem. (2003) 278(44):43089–94. 10.1074/jbc.M305956200

21.

Singh HR Yang Z Siddiqui S Peña LS Westerfield BH Fan Y et al A novel Alu-mediated Xq28 microdeletion ablates Taz and partially deletes Dnl1l in a patient with Barth syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. (2009) 149A(5):1082–5. 10.1002/ajmg.a.32822

22.

Johnston J Kelley RI Feigenbaum A Cox GF Iyer GS Funanage VL et al Mutation characterization and genotype-phenotype correlation in Barth syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. (1997) 61(5):1053–8.

Summary

Keywords

5' untranslated region, Barth syndrome, cardiomyopathy, start loss, TAFAZZIN

Citation

Singer ES, Smith J, Lin R, Morrish AM, Lal S, Irving C, Casey C, King I, Weintraub RG and Bagnall RD (2026) Case Report: Deletion in the 5' untranslated region of TAFAZZIN in a boy with Barth syndrome. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 13:1766067. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2026.1766067

Received

11 December 2025

Revised

20 January 2026

Accepted

22 January 2026

Published

16 February 2026

Volume

13 - 2026

Edited by

Umamaheswaran Gurusamy, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, United States

Reviewed by

Florencia Del Viso, Children’s Mercy Kansas City, United States

Robin Duncan, University of Waterloo, Canada

Shouyu Wang, Fudan University, China

Navin B. Ramakrishna, Genome Institute of Singapore (A*STAR), Singapore

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Singer, Smith, Lin, Morrish, Lal, Irving, Casey, King, Weintraub and Bagnall.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Richard D. Bagnall r.bagnall@centenary.org.au

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.