- Centre for Sustainable Future Technologies, Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia, Torino, Italy

Precision medicine in oncology needs to enhance its capabilities to match diagnostic and therapeutic technologies to individual patients. Synthetic biology streamlines the design and construction of functionalized devices through standardization and rational engineering of basic biological elements decoupled from their natural context. Remarkable improvements have opened the prospects for the availability of synthetic devices of enhanced mechanism clarity, robustness, sensitivity, as well as scalability and portability, which might bring new capabilities in precision cancer medicine implementations. In this review, we begin by presenting a brief overview of some of the major advances in the engineering of synthetic genetic circuits aimed to the control of gene expression and operating at the transcriptional, post-transcriptional/translational, and post-translational levels. We then focus on engineering synthetic circuits as an enabling methodology for the successful establishment of precision technologies in oncology. We describe significant advancements in our capabilities to tailor synthetic genetic circuits to specific applications in tumor diagnosis, tumor cell- and gene-based therapy, and drug delivery.

Introduction

Synthetic biology builds on the transformative assertion that engineering approaches could be used to elucidate design principles of cellular systems and to implement synthetic digital and analog subsystems for a variety of end settings including health applications (Lienert et al., 2014). Since its beginning as a formalized engineering paradigm, which could be envisioned near the turn of the century when bacterial cells were programmed with basic genetic circuits (Gardner et al., 2000; Cameron et al., 2014), synthetic biology has provided a rigorous mechanistic foundation extremely helpful to quantitatively characterize the basic functions that are performed by the simple parts of a system and that collectively dictate the emergence of natural and human-defined phenotypes (Mukherji and van Oudenaarden, 2009; Elowitz and Lim, 2010). Nowadays, synthetic biology has greatly expanded in outlook, arising expectations, and stream of thought owing to the increasing intensive convergence of multifaceted engineering, life science, and biotechnology subfields.

The rapid progresses ensued from basic and applied synthetic biology research hold great promise in many contexts of substantial scientific and economic interest. The objective of this review is to reflect on the applications relevant to develop solutions to some of the challenges put forward by precision oncology. The precision paradigm that is being variously adopted by oncology refers both to the chances for enhanced resolution and clarity in tumor identification as well as to the implementation of therapeutic interventions that could be set up on individual case basis (Jain, 2013; Kis et al., 2015). In this text, we provide an overview of synthetic genetic circuits engineering that apply to precision oncology and take advantage of the tight molecular control operating at multiple levels of gene expression (Vazquez-Anderson and Contreras, 2013; Fern and Schulman, 2017), through signal amplification, feedback, oscillatory, and logic capabilities (Wang et al., 2013; Lienert et al., 2014). Specifically, we show that engineered gene regulatory circuits are widening the assays available to report on tumor state and anti-tumor drug responses as well as to devise localized therapeutic options; for instance, increasingly advanced studies are being published on engineering cell classifiers (Morel et al., 2016; Mohammadi et al., 2017) and synthetic constructs for local payload delivery (Wagner et al., 2016). Furthermore, multiple gene-and cell-based therapy choices enhanced by synthetic biology applications are here described (Lim and June, 2017).

A great deal of efforts has been applied to investigate the rules of gene expression by precise measurements afforded by artificially constructed systems (Mukherji and van Oudenaarden, 2009). Much of the early contributions have focused on detailed and quantitative views of transcriptional regulation (Hockenberry and Jewett, 2012), and proceeded in tandem with experimental breakthroughs such as the use of combinatorial promoter libraries (Gertz et al., 2009). Nevertheless, substantial progress has also been achieved in ascertaining other regulatory mechanisms including post-transcriptional, translational, and post-translational modifications (Isaacs et al., 2004; Grilly et al., 2007). Almost all of these regulatory mechanisms are applicable to design gene regulatory platforms with controllable and predictable behaviors. Building on natural examples of regulatory circuits known to tune transcriptional and post-transcriptional activity (Cora et al., 2017), synthetic devices have demonstrated to modulate malignant phenotypes. Interesting examples here include synthetically engineered microRNAs targeting the MYC proto-oncogene (c-Myc) gene, which were shown to inhibit proliferation and induce apoptosis in bladder cancer cells (Fu et al., 2015), and the usage of aptamers to induce tumor cell death by destabilizing the apoptosis regulator bcl-2 (Soundararajan et al., 2008).

While the approaches to design the synthetic biological circuits that will be described could greatly vary, it is clear that abstraction, standardization (Galdzicki et al., 2014), and modularity (Endy, 2005) have been essential to formalize the design of such a broad range of gene expression systems and to handle biological complexity. Such principles lie behind many synthetic circuits to develop diagnostic and therapeutic tools, where basic parts such as promoters, gene coding sequences, terminators, and ribosome binding sites are assembled into modules such as toggle switches (Gardner et al., 2000; Niederholtmeyer et al., 2013) oscillators, and cascades (Davidsohn et al., 2015) to create predictable and continuously more sophisticated functionalities. The achievement of general and scalable systems (Weinberg et al., 2017) capable of sensing, reacting to, and controlling multiple component activities in vivo have required advanced programming paradigms to overcome barriers such as metabolic load (Weinberg et al., 2017), crosstalk (Huh et al., 2013; Kosuri et al., 2013; Trosset and Carbonell, 2013; Brewster et al., 2014), resource sharing (Cardinale et al., 2013; Segall-Shapiro et al., 2014), and gene expression noise (An and Chin, 2009) and thus to grant stability, robustness, and reliability of the engineered systems (Green et al., 2017).

The review is structured in two main sections. The former section summarizes engineering principles that are being applied to devise synthetic genetic circuits. Here, molecular tools exploiting transcriptional, post-transcriptional/translational, and post-translational control mechanisms of gene expression are discussed in separate subsections. The latter section describes specific areas of diagnostic and therapeutic technologies within the precision oncology enterprise where the potential of synthetic biology applications sits at the vanguard.

From Gene Switches to Computing Devices

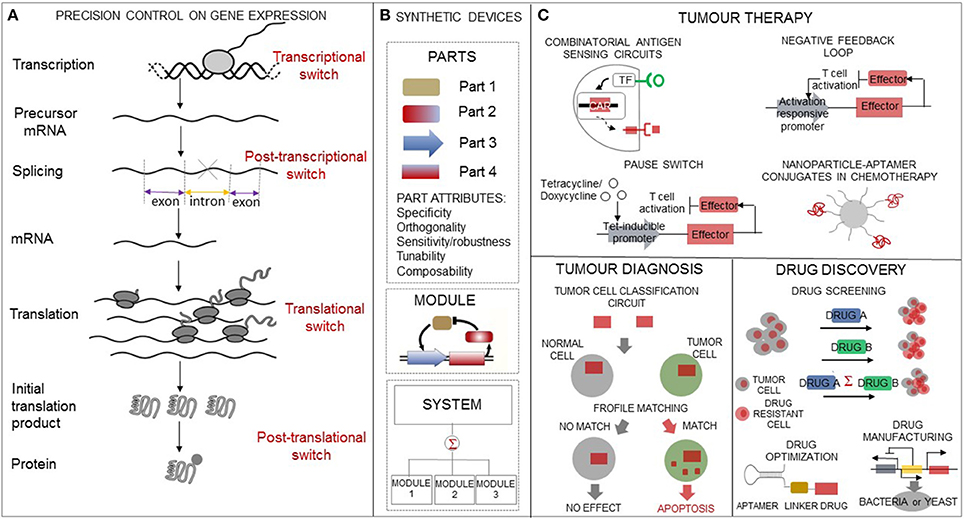

Biological engineering has enlarged the molecular tool set available to customize multicomponent constructs with increasingly varied and improved options for controlling gene expression. In particular, a great deal of design effort on synthetic gene switches has allowed to engineer cells with the capacity to sense, process, and switch gene expression state in response to intra- and extracellular signals. Engineering such sensing-actuating constructs involves linking a sensor part that detects the ligand to an actuator part that controls gene expression. The molecular design principles that have been used to customize synthetic gene switches differ according to the gene expression stage at which the switch is applied as well as on the distinctive properties that come with the choice of the switch constitutive parts (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Biological engineering enacts precision tools in oncology. (A) The synthetic biology toolbox contains a variety of regulatory switches which allow gene expression control at transcriptional, post-transcriptional, translational, and post-translational levels. (B) Abstraction hierarchy used for synthetic circuit design and construction. The hierarchy includes: parts, which are endowed with basic biological functions, devices, which are any combination of parts that perform a human-defined function, and systems, which are any combination of devices. (C) Overview of synthetic circuits' applications ranging from drug discovery to tumor diagnosis and to tumor therapy relevant to precision oncology interventions.

Tools for Transcriptional Control

Circuits based on transcriptional control make up the largest number of synthetic circuits and share a common design, where an actuator part enabling positive or negative regulation of transcription is connected with a DNA-binding part that recognizes a promoter DNA sequence. Upon binding of a ligand, a sensor part triggers the activity of this complex through tethering or allosteric mechanisms (Ausländer and Fussenegger, 2013). While native transcription factors have come a long way in synthetic biology applications, it was not until the arrival of programmable transcription factors that it was possible to enhance the engineering capabilities of human-defined transcriptional switches. For example, Zinc-Finger (ZF)-containing factors (Khalil et al., 2012), Transcription Activator-Like Effectors (TALEs; Sanjana et al., 2012; Li et al., 2015), and Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR)-based regulators (Bikard et al., 2013; Qi et al., 2013; Ferry et al., 2017) can be engineered to bind to specific DNA sequences of interest. Each class of TFs comes with advantages and disadvantages and is ideally suited to different applications (Jain, 2013). Major limitations in the application of ZF-containing factors on synthetic circuits are their limited modularity and the lack of specificity of some ZF domains. TALEs are more straightforward to design than ZFs even though they pose challenges to cloning and delivery into host genomes. The CRISPR-based regulators are easier to construct than TALEs which, nonetheless, perform better for the construction of layered circuits (Lebar and Jerala, 2016). The plasmid pT181 antisense-RNA-mediated transcription attenuation platform is well established to control transcription through RNA–RNA interactions (Lucks et al., 2011).

Tools for Post-transcriptional Control

Due to its functional diversity, RNA is an advantageous substrate for information sensing, processing, and computation functions. Furthermore, the transient nature of RNA is appealing for applications where safety is a primary concern, since RNA-mediated circuits do not leave a long-term genetic footprint. RNA-based sensing-actuation switches are generally composed of highly folded sensor RNAs (aptamers) that, through conformational changes induced by the binding of small molecules or proteins, regulate the activity of RNA actuators that can operate in cis or in trans. Switches can sometimes rely on a transmitter part to transduce information between the sensor and actuator (Ogawa and Maeda, 2008). Aptamers have been engineered to respond predominantly to small molecules and nucleic acids (Werstuck and Green, 1998; Win et al., 2009; Shen et al., 2015) with extreme specificity whereas aptamers sensing proteins are far less intensely exploited (Culler et al., 2010).

Actuation can occur through diverse mechanisms including splicing, stability, translation, and mRNA localization. Owing to the known impact of ribonucleases (RNases) on RNA maturation and stability, aptamers have often been combined with RNA substrates for RNase activities (Vazquez-Anderson and Contreras, 2013; Comeau et al., 2016). Many RNA-based devices combine aptamers with catalytic actuators such as self-cleaving ribozymes to achieve flexible regulatory properties to fit application-specific performance requirements (Win and Smolke, 2007; Chen et al., 2010; Ketzer et al., 2012). Aptamers were also used with RNA interference substrates to control target mRNA silencing by regulating Drosha processing of pri-miRNAs (Beisel et al., 2011) or Dicer processing of small hairpin RNAs in response to endogenous signals (Saito et al., 2011). Furthermore, siRNAs and miRNAs have been shown to provide valuable options to implement Boolean logic frameworks (Rinaudo et al., 2007; Xie et al., 2011; Schreiber et al., 2016). A variety of switches have been developed to regulate translation of an open reading frame in response to the binding between the aptamer and small molecule (Stoltenburg et al., 2007; Wroblewska et al., 2015) or protein ligand (Hanson et al., 2003; Win and Smolke, 2007). Translation-control switches mainly affect translation initiation, such as the translational repression/activation switches consisting of the ribosomal protein L7Ae and its box C/D kink-turn binding RNA motif (Saito et al., 2010, 2011). Furthermore, engineered systems can repress and/or activate translation by inducing conformational changes in nascent structured mRNA that modulate the access of the translational machinery to ribosome binding sites (Isaacs et al., 2004; Salis et al., 2009). Enhancement of protein synthesis has been recently achieved by the use of natural and synthetic antisense long non-coding RNAs (Yao et al., 2015) which were named SINEUPs due to the requisite of the inverted SINEB2 sequence to UP-regulate gene-specific translation (Zucchelli et al., 2015). Finally, engineering upstream Open Reading Frames (uORFs), whose regulatory potential is increasingly being appreciated (Re et al., 2016), is predictably an additional exploitable tool for protein manufacturing (Ferreira et al., 2013). Finally, RNA-based devices have been built to enhance gene regulatory activities through co-localization (Lee et al., 1999).

Artificial signal cascades can be constructed by combining multiple regulators, examples of which are inverter modules for synthetic translational switches (Endo et al., 2013). Programming Boolean operators for translational regulation has also been allowed by rationally designed variants of the RNA-IN-RNA-OUT antisense RNA-mediated translation system (Mutalik et al., 2012) as well as by the design of multiple orthogonal ribosome-mRNA pairs (Rackham and Chin, 2005), which were also implemented to synthesize orthogonal transcription-translation networks (An and Chin, 2009).

Tools for Post-translational Control

Synthetic switches have been designed that control protein activity by altering protein stability, which for instance is obtained by temporarily tagging proteins with a degradation signal, which guides the protein to the endogenous ubiquitin-proteasome system (Los et al., 2008; Collins et al., 2017). Efforts to engineer phosphorylation-mediated circuitry have been undertaken to rewire and construct MAP kinase circuits (Bashor et al., 2008; Wei et al., 2012; Ryu and Park, 2015). Additionally, the ability of inteins to form and cleave specific peptide bonds is extensively exploited to implement sensors of protein-protein interactions and small molecules, to realize synthetic circuits to deliver CRISPR-Cas9 system components (Truong et al., 2015) and to implement logic gates (Schaerli et al., 2014). Further efforts are ongoing to engineer and characterize synthetic compartmentalization approaches providing veritable solutions to implement modularity in synthetic devices (Chen and Silver, 2012).

Synthetic Circuit-Based Tools for Precision Medicine in Oncology

We outline synthetic biology applications which are expanding existing options in cancer diagnosis, cancer therapeutics, and for pharmaceutical compound screening (Figure 1).

Tumor Diagnosis

Precise cell state discrimination is essential for in vivo targeting of cancer cells. Medical diagnosis based on individual elements is unavoidably thwarted by lack of specificity and sensitivity. Therefore, diagnostic algorithms are being formalized using combinatorial Boolean logic to perform integrated detection and analysis of multiple signals in living cells (Rubens et al., 2016; Schreiber et al., 2016). Expression profiles are widely used to drive decision-making circuits such as the multi-input RNAi-based logic circuit identifying specific cancer cells (Xie et al., 2011). The cancer classifier circuit implemented in this study selectively triggers either a fluorescent reporter or apoptosis in HeLa cells. More precisely, this circuit integrates sensory information from six endogenous microRNAs to determine whether a cell matches a pathological reference pattern characteristic of the HeLa cervical cancer cell line and, if so, produces an apoptotic response. Early efforts to develop bio-based computing capabilities such as counting (Friedland et al., 2009) and memory storage (Siuti et al., 2013) lead to the notion that bacterial cells could become diagnostic indicators for recording exposure events (Cronin et al., 2012). In one of such studies, probiotic bacteria were transformed with a dual-stabilized, high-expression lacZ vector, and an integrated luxCDABE cassette endowing luminescent visualization in order to target, visualize, and diagnose liver metastasis (Danino et al., 2015). A recent study brought whole-cell biosensor closer to clinical requirements by configuring digital amplifying genetic switches, based on transistor-like three terminal devices (Bonnet et al., 2013), to actuate logic gates in bacterial chasses (Courbet et al., 2015). Here, digital amplifying switches are used in Boolean logic gates to perform complex signal processing tasks such as multiplexed detection of clinically relevant markers, signal digitization, and amplification along with storage of the medically informed outcome in a stable DNA register for a posteriori interrogation. Standardized devices for cancer diagnosis require a great deal of fine-tuning efforts to make combinatorial logic gates to perform as intended. Therefore, progressively advanced studies are being reported, opening interesting avenues to the automation of combinatorial circuit engineering (Ausländer et al., 2012; Nielsen et al., 2016; Weinberg et al., 2017). Even so, there are cumbersome problems that still need to be dealt with. Despite the breadth and depth described above, it is difficult to control the trade-off between specificity and sensitivity achieved by expression-based cell classifier designs, the changes in constructs performance dependent on genetic context, space and time as well as the possible toxicity induced by regulators overexpression. Balancing these problems must be addressed in order to allow synthetic gene constructs to become part of a personalized cancer therapy toolbox.

Tumor Therapy

Synthetic biology is primed to provide the conceptual framework and genetic tools necessary to enhance cell- (Fischbach et al., 2013) and gene- (Costales et al., 2017) based therapeutics.

Cell-Based Therapeutics

Immunotherapy has shown great promise for eradicating tumor in clinical trials. Much of the current success derives from therapies based on engineering T cell receptors (TCRs) and chimeric antigen receptors (Wilkie et al., 2012; Kloss et al., 2013; Duong et al., 2015; CARs), that consist of a cancer antigen-specific single-chain variable fragment (scFv) fused to a T cell signaling domain that triggers activation and proliferation. Nowadays, synthetic sensors, switches, and circuits are primed to improve T cell therapy efficacy and meet safety concerns (e.g., discriminative capacity between tumors and vital organs and potential adverse side effects) by providing inducible control over the specificity, localization, duration, and extent of T cell activities.

Receptor systems

One of the most important challenges is represented by cell specificity. A powerful way to enhance on-target activity of therapeutic T cells is to engineer combinatorial receptor systems such as dual receptor AND-gate T cells (Roybal et al., 2016). In the antibody-coupled T cell receptor (ACTR) system, the scFv is replaced with the extracellular portion of CD16, a receptor that binds to the constant fragment of antibodies so that any relevant cancer-specific antibody can, in principle, be administered upon antigen binding (Kudo et al., 2014). Another major concern is the potential risk of unpredictable therapeutic effect. To enhance controllability, the recent GoCAR-T system incorporates a switch that activates CAR T cells when it is triggered not only by the target antigen expressed on the surface of the cancer cells but also by controlled administration of the drug rimiducid (Foster et al., 2017).

Control switches and circuits

T cell therapies could meet safety concerns if it were possible to eliminate quickly the engineered cells upon adverse side effects. Drug-inducible kill switches are an interesting development to achieve this goal. A recent example employs an inducible caspase 9 in conjunction with a CD20-specific CAR to test in vivo its potential to remove CAR-bearing T cells (Budde et al., 2013). Another study proposed to fuse caspase 9 to a modified FK-binding protein in order to allow conditional dimerization. This construct was proven to lead to cell death when exposed to a dimerizing small molecule (Di Stasi et al., 2011).

The design of negative feedback loops and inducible pause switches is proving a useful alternative to T cell elimination by modulating the immune response amplitude and timing. These circuits exploit the ability of bacterial virulence effector proteins to evade the immune response. The former type creates a negative feedback loop by expressing these proteins under the control of a T cell activation responsive promoter (Wei et al., 2012). The latter type of circuits pauses T cell activation by expressing bacterial virulence proteins under the control of a tetracycline inducible promoter. Indeed, adding the drug leads to the expression of the effector proteins, which in turn stop cell activation until the drug is removed (Wei et al., 2012).

Finally, a potent tool to regulate the therapy safety and efficacy is provided by growth switches (Chen et al., 2010). Here, a ribozyme drives self-cleavage of the cytokine transcript and leads to cytokine expression shut off; adding a proper drug prevents self-cleavage so that cytokines are expressed and lead to T cell proliferation.

Gene-Based Therapeutics

Gene circuit engineering has greatly improved our ability to programme genes involved in tumor origin and progress. For instance, some high-affinity RNA aptamers against PPAR-δ, a lipid-sensing nuclear receptor involved in cancer (Kwak et al., 2009), β-catenin (Lee et al., 2006), and nucleolin (Soundararajan et al., 2008), could lead to reduction of tumor-forming potential. Furthermore, a computational workflow, that selects RNA motif-small molecule binding interactions by library-vs.-library screening (2DCS) and then mines them against RNA folds in the transcriptome, allowed to identify a small molecule inhibitor of an oncogenic non-coding RNA (Velagapudi et al., 2017). SiRNAs can also specifically bind to target genes but their application can be limited by the absence of effective vehicles. For this purpose, several studies have proposed the use of aptamers in siRNA expressing constructs as vehicles (Tai and Gao, 2016).

Drug Delivery

Today nanobiotechnology provides extremely versatile options to address the localized delivery of genetically encoded tools such as virus-based vectors modified to carry engineered payloads (Ryan et al., 2004; Li et al., 2005), oncolytic viruses exploiting dual promoter logics (Nissim and Bar-Ziv, 2010), and nanoparticle-aptamer bioconjugates (Farokhzad et al., 2006). Recently, (Douglas et al., 2012) described a shape-switching device for targeted transport of signaling molecules. The robotic DNA device consists of a barrel provided with DNA aptamer-based locks that open in response to the binding of cell type-specific antigen keys. Vibrant developments greatly enhance and wide the range of applicable dynamic DNA and RNA-based nanoparticles (Afonin et al., 2013; Edwardson et al., 2016) besides opening newer avenue to conjugate inter-dependent nanoparticles (Halman et al., 2017). Polymer materials responsive to external signals (Stuart et al., 2010) such as nanogels conjugated to ligands recognized by cell specific receptors (Oishi et al., 2007), virus-mimetic nanogels (Lee et al., 2008), and hydrogels based on ligand-responsive DNA–protein interactions (Christen et al., 2011) demonstrate the essential progress in the area. In the future, nanorobots could be routed toward the tumor by exploiting the tumor-homing ability of self-propelled bacteria, similar to a recent study (Katuri et al., 2017). Biological vesicles derived from mammalian cells have also attracted much attention for in vivo delivery (Yoo et al., 2011). In particular, exosomes (Wang et al., 2016) have been engineered to deliver chemotherapeutics to tumor tissue in mouse models for cancer (Tian et al., 2014).

Drug Discovery

Synthetic biology is helping to address previously unfeasible challenges the field of drug discovery. Progress on design of synthetic genetic circuits (Carbonell et al., 2014; Trosset and Carbonell, 2015) has opened the possibility of their use not only for production of drugs (Breitling and Takano, 2015) but also for the development of platforms for identification and validation of drug targets (Firman et al., 2012; Kasap et al., 2014) as well as for phenotypic cell-based screening approaches (Duportet et al., 2014) such as the screening for anti-cancer drugs presented in Gonzalez-Nicolini et al. (2004), that discriminates between proliferation competent and mitotically inert cells and eliminates preferentially neoplastic ones. With this purpose, (Gonzalez-Nicolini et al., 2004) engineered a transgenic CHO-K1-derived cell line to enable G1-specific growth arrest conditioned on the tetracycline responsive overexpression of the human cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27. Another study applied a one-bead-two-compound (OB2C) cell-based screening approach for the discovery of synthetic molecules that can interact with cellular receptors as well as enhance or inhibit downstream cell signaling (Kumaresan et al., 2011). The primary innovation of this system is represented by the usage of beads provided with two chemical molecules on the surface and a chemical tag to probe cellular responses. When cells are incubated with the OB2C library, a cell adhesion ligand captures live cells on each bead in the library. The bound cells can interface with the tethered OB2C library compounds and then be probed for specific cellular signaling pathways such as leukemic cell death responses (Kumaresan et al., 2011). Largely because of similar progresses in conceptual design and technologies, synthetic biology is being employed as a powerful way to identify drug mechanisms of action and to accelerate the development of drug combination-based approaches (Chandrasekaran et al., 2016).

Conclusions

In this review, we focus on advances in biological engineering which stimulated the development of innovative approaches for precision intervention in oncology. The growing contribution of synthetic biology to drug discovery as well as the widening availability of synthetic circuits, which are already being used in different human compatible cell types and animal models for safe operation of gene- and cell-based therapies, demonstrate the potential of future approaches integrating systems and synthetic biology tools to precisely match therapies to individual cancer patients.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and approved it for publication.

Funding

This manuscript has been funded by the Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Afonin, K. A., Viard, M., Martins, A. N., Lockett, S. J., Maciag, A. E., Freed, E. O., et al. (2013). Activation of different split functionalities on re-association of RNA-DNA hybrids. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 296–304. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2013.44

An, W., and Chin, J. W. (2009). Synthesis of orthogonal transcription-translation networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 8477–8482. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900267106

Ausländer, S., Ausländer, D., Müller, M., Wieland, M., and Fussenegger, M. (2012). Programmable single-cell mammalian biocomputers. Nature 487, 123–127. doi: 10.1038/nature11149

Ausländer, S., and Fussenegger, M. (2013). From gene switches to mammalian designer cells: present and future prospects. Trends Biotechnol. 31, 155–168. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2012.11.006

Bashor, C. J., Helman, N. C., Yan, S., and Lim, W. A. (2008). Using engineered scaffold interactions to reshape MAP kinase pathway signaling dynamics. Science 319, 1539–1543. doi: 10.1126/science.1151153

Beisel, C. L., Chen, Y. Y., Culler, S. J., Hoff, K. G., and Smolke, C. D. (2011). Design of small molecule-responsive microRNAs based on structural requirements for Drosha processing. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, 2981–2994. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq954

Bikard, D., Jiang, W., Samai, P., Hochschild, A., Zhang, F., and Marraffini, L. A. (2013). Programmable repression and activation of bacterial gene expression using an engineered CRISPR-Cas system. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, 7429–7437. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt520

Bonnet, J., Yin, P., Ortiz, M. E., Subsoontorn, P., and Endy, D. (2013). Amplifying genetic logic gates. Science 340, 599–603. doi: 10.1126/science.1232758

Breitling, R., and Takano, E. (2015). Synthetic biology advances for pharmaceutical production. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 35, 46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2015.02.004

Brewster, R. C., Weinert, F. M., Garcia, H. G., Song, D., Rydenfelt, M., and Phillips, R. (2014). The transcription factor titration effect dictates level of gene expression. Cell 156, 1312–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.022

Budde, L. E., Berger, C., Lin, Y., Wang, J., Lin, X., Frayo, S. E., et al. (2013). Combining a CD20 chimeric antigen receptor and an inducible caspase 9 suicide switch to improve the efficacy and safety of T cell adoptive immunotherapy for lymphoma. PLoS ONE 8:e82742. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082742

Cameron, D. E., Bashor, C. J., and Collins, J. J. (2014). A brief history of synthetic biology. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 12, 381–390. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3239

Carbonell, P., Parutto, P., Baudier, C., Junot, C., and Faulon, J-L. (2014). Retropath: automated pipeline for embedded metabolic circuits. ACS Synth. Biol. 3, 565–577. doi: 10.1021/sb4001273

Cardinale, S., Joachimiak, M. P., and Arkin, A. P. (2013). Effects of genetic variation on the E. coli host-circuit interface. Cell Rep. 4, 231–237. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.06.023

Chandrasekaran, S., Cokol-Cakmak, M., Sahin, N., Yilancioglu, K., Kazan, H., Collins, J. J., et al. (2016). Chemogenomics and orthology-based design of antibiotic combination therapies. Mol. Syst. Biol. 12:872. doi: 10.15252/msb.20156777

Chen, A. H., and Silver, P. A. (2012). Designing biological compartmentalization. Trends Cell Biol. 22, 662–670. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2012.07.002

Chen, Y. Y., Jensen, M. C., and Smolke, C. D. (2010). Genetic control of mammalian T-cell proliferation with synthetic RNA regulatory systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 8531–8536. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001721107

Christen, E. H., Karlsson, M., Kämpf, M. M., Schoenmakers, R., Gübeli, R. J., Wischhusen, H. M., et al. (2011). Conditional DNA-protein interactions confer stimulus-sensing properties to biohybrid materials. Adv. Funct. Mater. 21, 2861–2867. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201100731

Collins, I., Wang, H., Caldwell, J. J., and Chopra, R. (2017). Chemical approaches to targeted protein degradation through modulation of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Biochem. J. 474, 1127–1147. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20160762

Comeau, M.-A., Lafontaine, D. A., and Abou Elela, S. (2016). The catalytic efficiency of yeast ribonuclease III depends on substrate specific product release rate. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 7911–7921. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw507

Cora, D., Re, A., Caselle, M., and Bussolino, F. (2017). MicroRNA-mediated regulatory circuits: outlook and perspectives. Phys. Biol. 14:045001. doi: 10.1088/1478-3975/aa6f21

Costales, M. G., Haga, C. L., Velagapudi, S. P., Childs-Disney, J. L., Phinney, D. G., and Disney, M. D. (2017). Small molecule inhibition of microRNA-210 reprograms an oncogenic hypoxic circuit. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 3446–3455. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b11273

Courbet, A., Endy, D., Renard, E., Molina, F., and Bonnet, J. (2015). Detection of pathological biomarkers in human clinical samples via amplifying genetic switches and logic gates. Sci. Transl. Med. 7:289ra83. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa3601

Cronin, M., Akin, A. R., Collins, S. A., Meganck, J., Kim, J.-B., Baban, C. K., et al. (2012). High resolution in vivo bioluminescent imaging for the study of bacterial tumour targeting. PLoS ONE 7:e30940. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030940

Culler, S. J., Hoff, K. G., and Smolke, C. D. (2010). Reprogramming cellular behavior with RNA controllers responsive to endogenous proteins. Science 330, 1251–1255. doi: 10.1126/science.1192128

Danino, T., Prindle, A., Kwong, G. A., Skalak, M., Li, H., Allen, K., et al. (2015). Programmable probiotics for detection of cancer in urine. Sci. Transl. Med. 7:289ra84. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa3519

Davidsohn, N., Beal, J., Kiani, S., Adler, A., Yaman, F., Li, Y., et al. (2015). Accurate predictions of genetic circuit behavior from part characterization and modular composition. ACS Synth. Biol. 4, 673–681. doi: 10.1021/sb500263b

Di Stasi, A., Tey, S.-K., Dotti, G., Fujita, Y., Kennedy-Nasser, A., Martinez, C., et al. (2011). Inducible apoptosis as a safety switch for adoptive cell therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 365, 1673–1683. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1106152

Douglas, S. M., Bachelet, I., and Church, G. M. (2012). A logic-gated nanorobot for targeted transport of molecular payloads. Science 335, 831–834. doi: 10.1126/science.1214081

Duong, C. P. M., Yong, C. S. M., Kershaw, M. H., Slaney, C. Y., and Darcy, P. K. (2015). Cancer immunotherapy utilizing gene-modified T cells: from the bench to the clinic. Mol. Immunol. 67, 46–57. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2014.12.009

Duportet, X., Wroblewska, L., Guye, P., Li, Y., Eyquem, J., Rieders, J., et al. (2014). A platform for rapid prototyping of synthetic gene networks in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 13440–13451. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1082

Edwardson, T. G. W., Lau, K. L., Bousmail, D., Serpell, C. J., and Sleiman, H. F. (2016). Transfer of molecular recognition information from DNA nanostructures to gold nanoparticles. Nat. Chem. 8, 162–170. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2420

Elowitz, M., and Lim, W. A. (2010). Build life to understand it. Nature 468, 889–890. doi: 10.1038/468889a

Endo, K., Hayashi, K., Inoue, T., and Saito, H. (2013). A versatile cis-acting inverter module for synthetic translational switches. Nat. Commun. 4:2393. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3393

Farokhzad, O. C., Cheng, J., Teply, B. A., Sherifi, I., Jon, S., Kantoff, P. W., et al. (2006). Targeted nanoparticle-aptamer bioconjugates for cancer chemotherapy in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 6315–6320. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601755103

Fern, J., and Schulman, R. (2017). Design and characterization of DNA strand-displacement circuits in serum-supplemented cell medium. ACS Synth. Biol. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.7b00105. [Epub ahead of print].

Ferreira, J. P., Overton, K. W., and Wang, C. L. (2013). Tuning gene expression with synthetic upstream open reading frames. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 11284–11289. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1305590110

Ferry, Q. R. V., Lyutova, R., and Fulga, T. A. (2017). Rational design of inducible CRISPR guide RNAs for de novo assembly of transcriptional programs. Nat. Commun. 8:14633. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14633

Firman, K., Evans, L., and Youell, J. (2012). A synthetic biology project - developing a single-molecule device for screening drug-target interactions. FEBS Lett. 586, 2157–2163. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.01.057

Fischbach, M. A., Bluestone, J. A., and Lim, W. A. (2013). Cell-based therapeutics: the next pillar of medicine. Sci. Transl. Med. 5:179ps7. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005568

Foster, A. E., Mahendravada, A., Shinners, N. P., Chang, W.-C., Crisostomo, J., Lu, A., et al. (2017). Regulated expansion and survival of chimeric antigen receptor-modified t cells using small molecule-dependent inducible MyD88/CD40. Mol. Ther. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.06.014. [Epub ahead of print].

Friedland, A. E., Lu, T. K., Wang, X., Shi, D., Church, G., and Collins, J. J. (2009). Synthetic gene networks that count. Science 324, 1199–1202. doi: 10.1126/science.1172005

Fu, X., Liu, Y., Zhuang, C., Liu, L., Cai, Z., and Huang, W. (2015). Synthetic artificial microRNAs targeting UCA1-MALAT1 or c-Myc inhibit malignant phenotypes of bladder cancer cells T24 and 5637. Mol. Biosyst. 11, 1285–1289. doi: 10.1039/C5MB00127G

Galdzicki, M., Clancy, K. P., Oberortner, E., Pocock, M., Quinn, J. Y., Rodriguez, C. A., et al. (2014). The Synthetic Biology Open Language (SBOL) provides a community standard for communicating designs in synthetic biology. Nat. Biotechnol. 32, 545–550. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2891

Gardner, T. S., Cantor, C. R., and Collins, J. J. (2000). Construction of a genetic toggle switch in Escherichia coli. Nature 403, 339–342. doi: 10.1038/35002131

Gertz, J., Siggia, E. D., and Cohen, B. A. (2009). Analysis of combinatorial cis-regulation in synthetic and genomic promoters. Nature 457, 215–218. doi: 10.1038/nature07521

Gonzalez-Nicolini, V., Fux, C., and Fussenegger, M. (2004). A novel mammalian cell-based approach for the discovery of anticancer drugs with reduced cytotoxicity on non-dividing cells. Invest. New Drugs 22, 253–262. doi: 10.1023/B:DRUG.0000026251.00854.77

Green, A. A., Kim, J., Ma, D., Silver, P. A., Collins, J. J., and Yin, P. (2017). Complex cellular logic computation using ribocomputing devices. Nature 548, 117–121. doi: 10.1038/nature23271

Grilly, C., Stricker, J., Pang, W. L., Bennett, M. R., and Hasty, J. (2007). A synthetic gene network for tuning protein degradation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Syst. Biol. 3:127. doi: 10.1038/msb4100168

Halman, J. R., Satterwhite, E., Roark, B., Chandler, M., Viard, M., Ivanina, A., et al. (2017). Functionally-interdependent shape-switching nanoparticles with controllable properties. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, 2210–2220. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx008

Hanson, S., Berthelot, K., Fink, B., McCarthy, J. E. G., and Suess, B. (2003). Tetracycline-aptamer-mediated translational regulation in yeast. Mol. Microbiol. 49, 1627–1637. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03656.x

Hockenberry, A. J., and Jewett, M. C. (2012). Synthetic in vitro circuits. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 16, 253–259. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2012.05.179

Huh, J. H., Kittleson, J. T., Arkin, A. P., and Anderson, J. C. (2013). Modular design of a synthetic payload delivery device. ACS Synth. Biol. 2, 418–424. doi: 10.1021/sb300107h

Isaacs, F. J., Dwyer, D. J., Ding, C., Pervouchine, D. D., Cantor, C. R., and Collins, J. J. (2004). Engineered riboregulators enable post-transcriptional control of gene expression. Nat. Biotechnol. 22, 841–847. doi: 10.1038/nbt986

Jain, K. K. (2013). Synthetic biology and personalized medicine. Med. Princ. Pract. 22, 209–219. doi: 10.1159/000341794

Kasap, C., Elemento, O., and Kapoor, T. M. (2014). DrugTargetSeqR: a genomics- and CRISPR-Cas9-based method to analyze drug targets. Nat. Chem. Biol. 10, 626–628. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1551

Katuri, J., Ma, X., Stanton, M. M., and Sánchez, S. (2017). Designing micro- and nanoswimmers for specific applications. Acc. Chem. Res. 50, 2–11. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00386

Ketzer, P., Haas, S. F., Engelhardt, S., Hartig, J. S., and Nettelbeck, D. M. (2012). Synthetic riboswitches for external regulation of genes transferred by replication-deficient and oncolytic adenoviruses. Nucleic Acids Res. 40:e167. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks734

Khalil, A. S., Lu, T. K., Bashor, C. J., Ramirez, C. L., Pyenson, N. C., Joung, J. K., et al. (2012). A synthetic biology framework for programming eukaryotic transcription functions. Cell 150, 647–658. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.045

Kis, Z., Pereira, H. S., Homma, T., Pedrigi, R. M., and Krams, R. (2015). Mammalian synthetic biology: emerging medical applications. J. R. Soc. interf. 12:20141000. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2014.1000

Kloss, C. C., Condomines, M., Cartellieri, M., Bachmann, M., and Sadelain, M. (2013). Combinatorial antigen recognition with balanced signaling promotes selective tumor eradication by engineered T cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 31, 71–75. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2459

Kosuri, S., Goodman, D. B., Cambray, G., Mutalik, V. K., Gao, Y., Arkin, A. P., et al. (2013). Composability of regulatory sequences controlling transcription and translation in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 14024–14029. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1301301110

Kudo, K., Imai, C., Lorenzini, P., Kamiya, T., Kono, K., Davidoff, A. M., et al. (2014). T lymphocytes expressing a CD16 signaling receptor exert antibody-dependent cancer cell killing. Cancer Res. 74, 93–103. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1365

Kumaresan, P. R., Wang, Y., Saunders, M., Maeda, Y., Liu, R., Wang, X., et al. (2011). Rapid discovery of death ligands with one-bead-two-compound combinatorial library methods. ACS Comb. Sci. 13, 259–264. doi: 10.1021/co100069t

Kwak, H., Hwang, I., Kim, J. H., Kim, M. Y., Yang, J. S., and Jeong, S. (2009). Modulation of transcription by the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta–binding RNA aptamer in colon cancer cells. Mol. Cancer Ther. 8, 2664–2673. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0214

Lebar, T., and Jerala, R. (2016). Benchmarking of TALE- and CRISPR/dCas9-based transcriptional regulators in mammalian cells for the construction of synthetic genetic circuits. ACS Synth. Biol. 5, 1050–1058. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.5b00259

Lee, E. S., Kim, D., Youn, Y. S., Oh, K. T., and Bae, Y. H. (2008). A virus-mimetic nanogel vehicle. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 47, 2418–2421. doi: 10.1002/anie.200704121

Lee, H. K., Choi, Y. S., Park, Y. A., and Jeong, S. (2006). Modulation of oncogenic transcription and alternative splicing by beta-catenin and an RNA aptamer in colon cancer cells. Cancer Res. 66, 10560–10566. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2526

Lee, N. S., Bertrand, E., and Rossi, J. (1999). mRNA localization signals can enhance the intracellular effectiveness of hammerhead ribozymes. RNA 5, 1200–1209. doi: 10.1017/S1355838299990246

Li, Y., Idamakanti, N., Arroyo, T., Thorne, S., Reid, T., Nichols, S., et al. (2005). Dual promoter-controlled oncolytic adenovirus CG5757 has strong tumor selectivity and significant antitumor efficacy in preclinical models. Clin. Cancer Res. 11, 8845–8855. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1757

Li, Y., Jiang, Y., Chen, H., Liao, W., Li, Z., Weiss, R., et al. (2015). Modular construction of mammalian gene circuits using TALE transcriptional repressors. Nat. Chem. Biol. 11, 207–213. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1736

Lienert, F., Lohmueller, J. J., Garg, A., and Silver, P. A. (2014). Synthetic biology in mammalian cells: next generation research tools and therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 15, 95–107. doi: 10.1038/nrm3738

Lim, W. A., and June, C. H. (2017). The principles of engineering immune cells to treat cancer. Cell 168, 724–740. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.01.016

Los, G. V., Encell, L. P., McDougall, M. G., Hartzell, D. D., Karassina, N., Zimprich, C., et al. (2008). HaloTag: a novel protein labeling technology for cell imaging and protein analysis. ACS Chem. Biol. 3, 373–382. doi: 10.1021/cb800025k

Lucks, J. B., Qi, L., Mutalik, V. K., Wang, D., and Arkin, A. P. (2011). Versatile RNA-sensing transcriptional regulators for engineering genetic networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 8617–8622. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015741108

Mohammadi, P., Beerenwinkel, N., and Benenson, Y. (2017). Automated design of synthetic cell classifier circuits using a two-step optimization strategy. Cell Syst. 4, 207.e14–218.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2017.01.003

Morel, M., Shtrahman, R., Rotter, V., Nissim, L., and Bar-Ziv, R. H. (2016). Cellular heterogeneity mediates inherent sensitivity-specificity tradeoff in cancer targeting by synthetic circuits. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 8133–8138. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1604391113

Mukherji, S., and van Oudenaarden, A. (2009). Synthetic biology: understanding biological design from synthetic circuits. Nat. Rev. Genet. 10, 859–871. doi: 10.1038/nrg2697

Mutalik, V. K., Qi, L., Guimaraes, J. C., Lucks, J. B., and Arkin, A. P. (2012). Rationally designed families of orthogonal RNA regulators of translation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 8, 447–454. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.919

Niederholtmeyer, H., Stepanova, V., and Maerkl, S. J. (2013). Implementation of cell-free biological networks at steady state. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 15985–15990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311166110

Nielsen, A. A. K., Der, B. S., Shin, J., Vaidyanathan, P., Paralanov, V., Strychalski, E. A., et al. (2016). Genetic circuit design automation. Science 352:aac7341. doi: 10.1126/science.aac7341

Nissim, L., and Bar-Ziv, R. H. (2010). A tunable dual-promoter integrator for targeting of cancer cells. Mol. Syst. Biol. 6:444. doi: 10.1038/msb.2010.99

Ogawa, A., and Maeda, M. (2008). An artificial aptazyme-based riboswitch and its cascading system in E. coli. Chembiochem 9, 206–209. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700478

Oishi, M., Hayashi, H., Iijima, M., and Nagasaki, Y. (2007). Endosomal release and intracellular delivery of anticancer drugs using pH-sensitive PEGylated nanogels. J. Mater. Chem. 17, 3720–3725. doi: 10.1039/B706973A

Qi, L. S., Larson, M. H., Gilbert, L. A., Doudna, J. A., Weissman, J. S., Arkin, A. P., et al. (2013). Repurposing CRISPR as an RNA-guided platform for sequence-specific control of gene expression. Cell 152, 1173–1183. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.022

Rackham, O., and Chin, J. W. (2005). A network of orthogonal ribosome x mRNA pairs. Nat. Chem. Biol. 1, 159–166. doi: 10.1038/nchembio719

Re, A., Waldron, L., and Quattrone, A. (2016). Control of gene expression by RNA binding protein action on alternative translation initiation sites. PLoS Comput. Biol. 12:e1005198. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005198

Rinaudo, K., Bleris, L., Maddamsetti, R., Subramanian, S., Weiss, R., and Benenson, Y. (2007). A universal RNAi-based logic evaluator that operates in mammalian cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 25, 795–801. doi: 10.1038/nbt1307

Roybal, K. T., Rupp, L. J., Morsut, L., Walker, W. J., McNally, K. A., Park, J. S., et al. (2016). Precision tumor recognition by T Cells with combinatorial antigen-sensing circuits. Cell 164, 770–779. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.01.011

Rubens, J. R., Selvaggio, G., and Lu, T. K. (2016). Synthetic mixed-signal computation in living cells. Nat. Commun. 7:11658. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11658

Ryan, P. C., Jakubczak, J. L., Stewart, D. A., Hawkins, L. K., Cheng, C., Clarke, L. M., et al. (2004). Antitumor efficacy and tumor-selective replication with a single intravenous injection of OAS403, an oncolytic adenovirus dependent on two prevalent alterations in human cancer. Cancer Gene Ther. 11, 555–569. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700735

Ryu, J., and Park, S-H. (2015). Simple synthetic protein scaffolds can create adjustable artificial MAPK circuits in yeast and mammalian cells. Sci Signal. 8:ra66. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aab3397

Saito, H., Fujita, Y., Kashida, S., Hayashi, K., and Inoue, T. (2011). Synthetic human cell fate regulation by protein-driven RNA switches. Nat. Commun. 2:160. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1157

Saito, H., Kobayashi, T., Hara, T., Fujita, Y., Hayashi, K., Furushima, R., et al. (2010). Synthetic translational regulation by an L7Ae-kink-turn RNP switch. Nat. Chem. Biol. 6, 71–78. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.273

Salis, H. M., Mirsky, E. A., and Voigt, C. A. (2009). Automated design of synthetic ribosome binding sites to control protein expression. Nat. Biotechnol. 27, 946–950. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1568

Sanjana, N. E., Cong, L., Zhou, Y., Cunniff, M. M., Feng, G., and Zhang, F. (2012). A transcription activator-like effector toolbox for genome engineering. Nat. Protoc. 7, 171–192. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.431

Schaerli, Y., Gili, M., and Isalan, M. (2014). A split intein T7 RNA polymerase for transcriptional AND-logic. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 12322–12328. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku884

Schreiber, J., Arter, M., Lapique, N., Haefliger, B., and Benenson, Y. (2016). Model-guided combinatorial optimization of complex synthetic gene networks. Mol. Syst. Biol. 12:899. doi: 10.15252/msb.20167265

Segall-Shapiro, T. H., Meyer, A. J., Ellington, A. D., Sontag, E. D., and Voigt, C. A. (2014). A “resource allocator” for transcription based on a highly fragmented T7 RNA polymerase. Mol. Syst. Biol. 10:742. doi: 10.15252/msb.20145299

Shen, S., Rodrigo, G., Prakash, S., Majer, E., Landrain, T. E., Kirov, B., et al. (2015). Dynamic signal processing by ribozyme-mediated RNA circuits to control gene expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, 5158–5170. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv287

Siuti, P., Yazbek, J., and Lu, T. K. (2013). Synthetic circuits integrating logic and memory in living cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 31, 448–452. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2510

Soundararajan, S., Chen, W., Spicer, E. K., Courtenay-Luck, N., and Fernandes, D. J. (2008). The nucleolin targeting aptamer AS1411 destabilizes Bcl-2 messenger RNA in human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 68, 2358–2365. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5723

Stoltenburg, R., Reinemann, C., and Strehlitz, B. (2007). SELEX–a (r)evolutionary method to generate high-affinity nucleic acid ligands. Biomol. Eng. 24, 381–403. doi: 10.1016/j.bioeng.2007.06.001

Stuart, M. A. C., Huck, W. T. S., Genzer, J., Müller, M., Ober, C., Stamm, M., et al. (2010). Emerging applications of stimuli-responsive polymer materials. Nat. Mater. 9, 101–113. doi: 10.1038/nmat2614

Tai, W., and Gao, X. (2016). Functional peptides for siRNA delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 110–111, 157–168. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2016.08.004

Tian, Y., Li, S., Song, J., Ji, T., Zhu, M., Anderson, G. J., et al. (2014). A doxorubicin delivery platform using engineered natural membrane vesicle exosomes for targeted tumor therapy. Biomaterials 35, 2383–2390. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.11.083

Trosset, J.-Y., and Carbonell, P. (2013). Synergistic synthetic biology: units in concert. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 1:11. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2013.00011

Trosset, J.-Y., and Carbonell, P. (2015). Synthetic biology for pharmaceutical drug discovery. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 9, 6285–6302. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S58049

Truong, D-J. J., Kühner, K., Kühn, R., Werfel, S., Engelhardt, S., Wurst, W., et al. (2015). Development of an intein-mediated split-Cas9 system for gene therapy. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, 6450–6458. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv601

Vazquez-Anderson, J., and Contreras, L. M. (2013). Regulatory RNAs: charming gene management styles for synthetic biology applications. RNA Biol. 10, 1778–1797. doi: 10.4161/rna.27102

Velagapudi, S. P., Luo, Y., Tran, T., Haniff, H. S., Nakai, Y., Fallahi, M., et al. (2017). Defining RNA-Small Molecule Affinity Landscapes Enables Design of a Small Molecule Inhibitor of an Oncogenic Noncoding, RNA. ACS Cent. Sci. 3, 205–216. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.7b00009

Wagner, H. J., Sprenger, A., Rebmann, B., and Weber, W. (2016). Upgrading biomaterials with synthetic biological modules for advanced medical applications. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 105, 77–95. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2016.05.004

Wang, J., Zheng, Y., and Zhao, M. (2016). Exosome-based cancer therapy: implication for targeting cancer stem cells. Front. Pharmacol. 7:533. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2016.00533

Wang, Y.-H., Wei, K. Y., and Smolke, C. D. (2013). Synthetic biology: advancing the design of diverse genetic systems. Annu. Rev. Chem. Biomol. Eng. 4, 69–102. doi: 10.1146/annurev-chembioeng-061312-103351

Wei, P., Wong, W. W., Park, J. S., Corcoran, E. E., Peisajovich, S. G., Onuffer, J. J., et al. (2012). Bacterial virulence proteins as tools to rewire kinase pathways in yeast and immune cells. Nature 488, 384–388. doi: 10.1038/nature11259

Weinberg, B. H., Pham, N. T. H., Caraballo, L. D., Lozanoski, T., Engel, A., Bhatia, S., et al. (2017). Large-scale design of robust genetic circuits with multiple inputs and outputs for mammalian cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 35, 453–462. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3805

Werstuck, G., and Green, M. R. (1998). Controlling gene expression in living cells through small molecule-RNA interactions. Science 282, 296–298. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5387.296

Wilkie, S., van Schalkwyk, M. C. I., Hobbs, S., Davies, D. M., van der Stegen, S. J. C., Pereira, A. C. P., et al. (2012). Dual targeting of ErbB2 and MUC1 in breast cancer using chimeric antigen receptors engineered to provide complementary signaling. J. Clin. Immunol. 32, 1059–1070. doi: 10.1007/s10875-012-9689-9

Win, M. N., Liang, J. C., and Smolke, C. D. (2009). Frameworks for programming biological function through RNA parts and devices. Chem. Biol. 16, 298–310. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.02.011

Win, M. N., and Smolke, C. D. (2007). A modular and extensible RNA-based gene-regulatory platform for engineering cellular function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 14283–14288. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703961104

Wroblewska, L., Kitada, T., Endo, K., Siciliano, V., Stillo, B., Saito, H., et al. (2015). Mammalian synthetic circuits with RNA binding proteins for RNA-only delivery. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 839–841. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3301

Xie, Z., Wroblewska, L., Prochazka, L., Weiss, R., and Benenson, Y. (2011). Multi-input RNAi-based logic circuit for identification of specific cancer cells. Science 333, 1307–1311. doi: 10.1126/science.1205527

Yao, Y., Jin, S., Long, H., Yu, Y., Zhang, Z., Cheng, G., et al. (2015). RNAe: an effective method for targeted protein translation enhancement by artificial non-coding RNA with SINEB2 repeat. Nucleic Acids Res. 43:e58. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv125

Yoo, J.-W., Irvine, D. J., Discher, D. E., and Mitragotri, S. (2011). Bio-inspired, bioengineered and biomimetic drug delivery carriers. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 10, 521–535. doi: 10.1038/nrd3499

Keywords: synthetic circuit, biological engineering, synthetic biology, precision medicine, tumor diagnosis, tumor therapy, drug delivery, drug discovery

Citation: Re A (2017) Synthetic Gene Expression Circuits for Designing Precision Tools in Oncology. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 5:77. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2017.00077

Received: 18 June 2017; Accepted: 16 August 2017;

Published: 28 August 2017.

Edited by:

Scott Bultman, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, United StatesReviewed by:

Giovanni Sorrentino, École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, SwitzerlandHatem E. Sabaawy, Rutgers University, The State University of New Jersey, United States

Copyright © 2017 Re. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Angela Re, YW5nZWxhLnJlQGlpdC5pdA==

Angela Re

Angela Re