Abstract

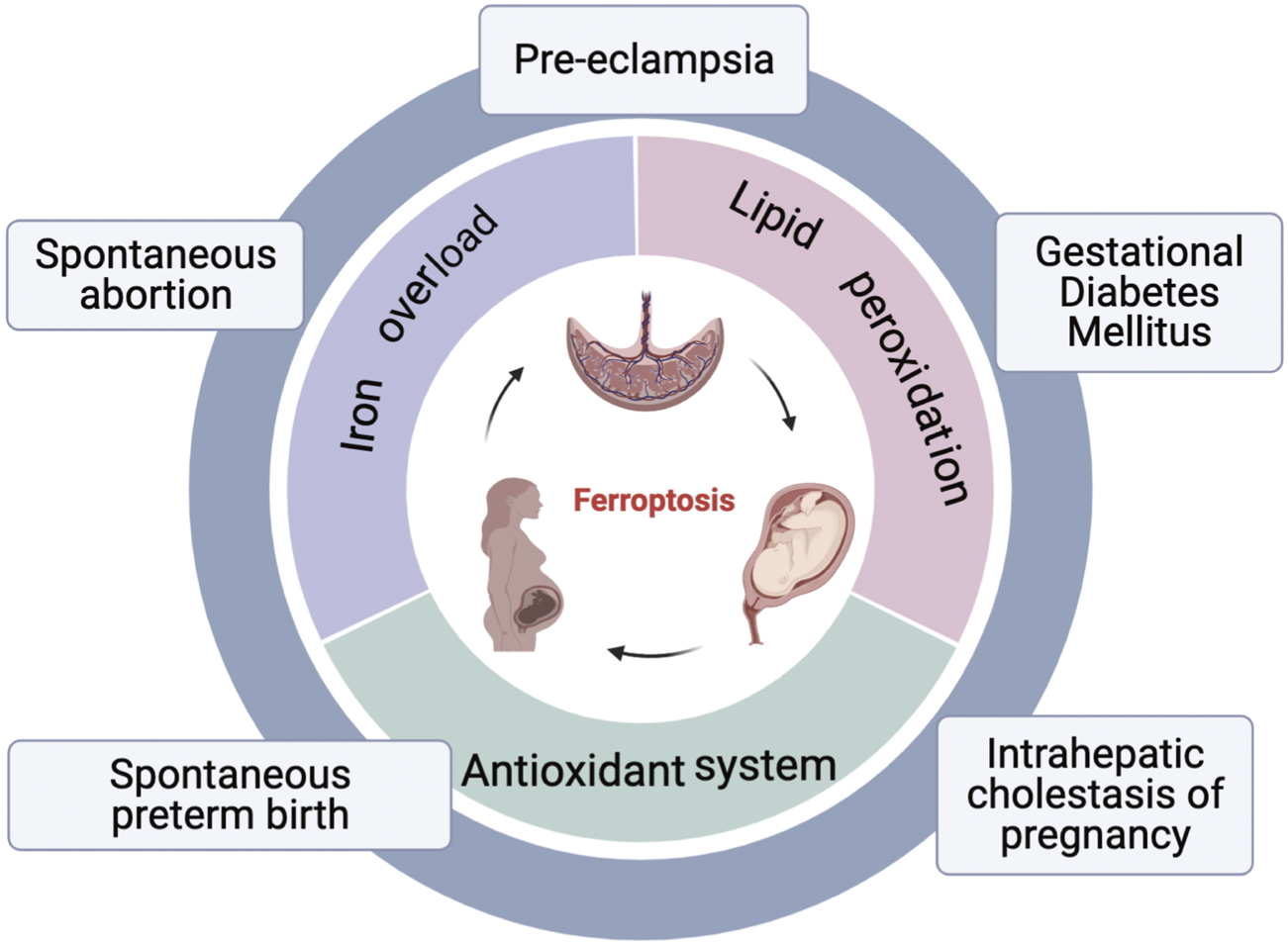

Ferroptosis is a form of regulated cell death characterized by iron overload, overwhelming lipid peroxidation, and disruption of antioxidant systems. Emerging evidence suggests that ferroptosis is associated with pregnancy related diseases, such as spontaneous abortion, pre-eclampsia, gestational diabetes mellitus, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, and spontaneous preterm birth. According to these findings, inhibiting ferroptosis might be a potential option to treat pregnancy related diseases. This review summarizes the mechanisms and advances of ferroptosis, the pathogenic role of ferroptosis in pregnancy related diseases and the potential medicines for its treatment.

1 Introduction

Cells are the fundamental organizing unit of life. Cell death, is therefore of critical importance in diverse aspects of mammalian development and homeostasis. Ferroptosis is a form of regulated cell death, coined in 2012. Generally, it is mainly characterized by iron overload, overwhelming lipid peroxidation, and disruption of antioxidant systems, particularly depletion of glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) (Long et al., 2022). Mounting evidence suggests that ferroptosis plays an important role in cancer (Lei et al., 2022), neurodegenerative diseases (Ryan et al., 2022), and ischemia/reperfusion injury, such as acute kidney injury (Fan et al., 2022), acute myocardial infarction (Miyamoto et al., 2022), and hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury (Ye et al., 2022a), and autoimmune disease, like psoriasis (Zhou et al., 2022) and rheumatoid arthritis (Long et al., 2022), Serving as the maternal-fetal interface, placenta plays a central role in maternal and fetal health during pregnancy. Placenta insufficiency, however, is tightly associated with pregnancy related diseases (PRDs), such as pre-eclampsia, gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), and intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) (Cindrova-Davies and Sferruzzi-Perri, 2022). Recently, there has been a growing appreciation for the importance of ferroptosis in PRDs. In this review, we summarized the molecular mechanisms of ferroptosis, as well as its pathogenic role and potential medicines in PRDs (Figure 1; Figure 2).

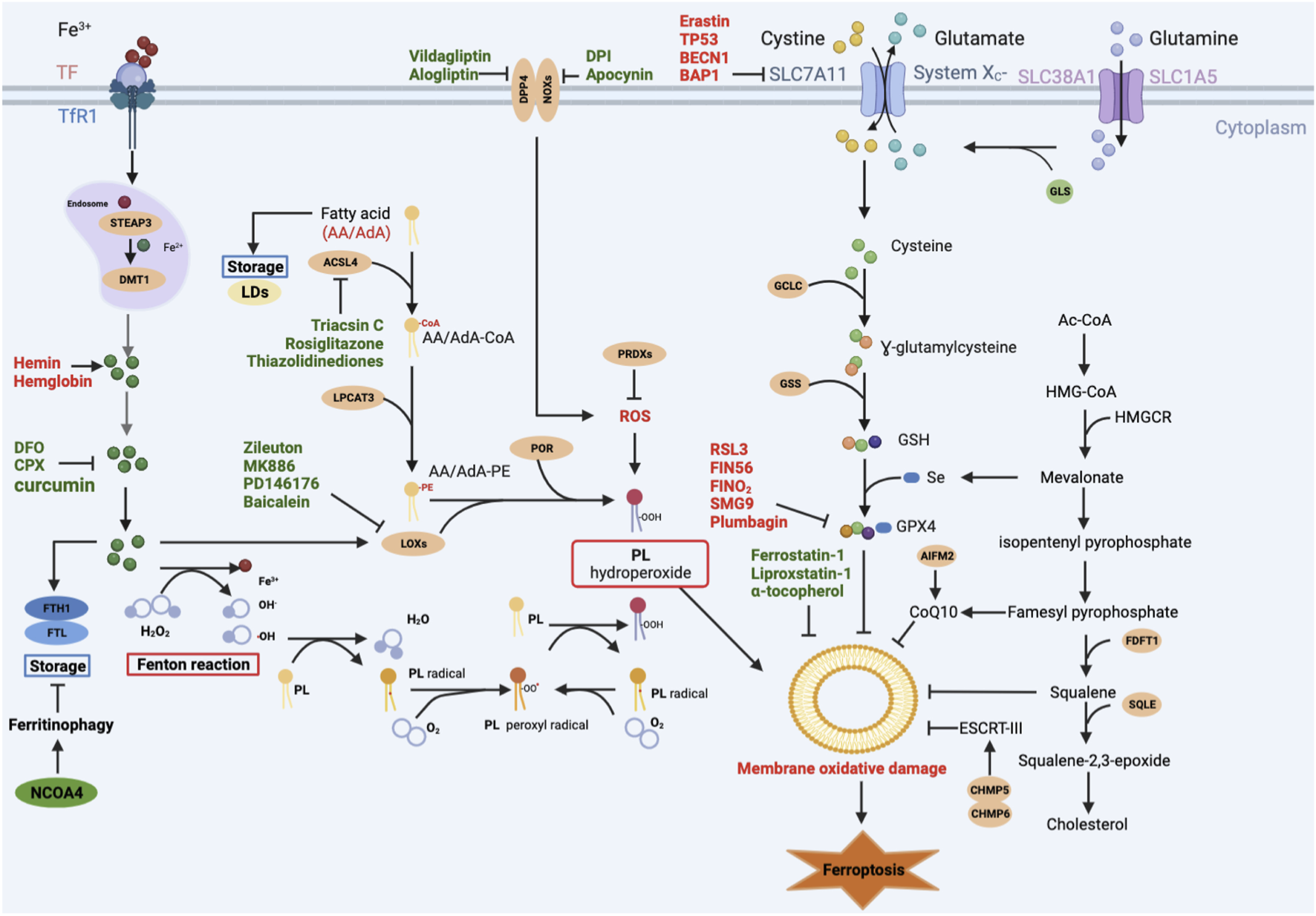

FIGURE 1

Main signaling pathways of ferroptosis. Ferroptosis can occur through three major pathways: 1) Iron overload: Fe2+ may directly generate excessive lipid reactive oxygen species (ROS) through the Fenton reaction, or Fe2+ acts as a cofactor of lipoxygenase (LOX) or prolyl hydroxylase, leading to lipid peroxidation and oxygen homeostasis. 2) Lipid peroxidation: ACSL4 catalyzes the ligation of CoA into free AA/AdA to form AA/AdA-CoA. AA/AdA-CoA are esterified into PE by LPCAT3 to form AA/AdA-PE. PE-AA/AdA-OOH are produced by the peroxidation of the AA/AdA-PE through non-enzymatically autoxidation (Fenton reaction) or enzyme-mediated pathways (LOXs). 3) Antioxidant systems: the SLC7A11-GSH-GPX4 axis, CoQ10 system, and other antioxidants like AIFM2, squalene. Red-colored: ferroptosis inducers; Green-colored: ferroptosis inhibitors.

FIGURE 2

An overview of ferroptosis and pregnancy related diseases. Three hallmarks of ferroptosis: lipid peroxidation, iron overload, and disorder of antioxidant systems; Pregnancy related diseases associated with ferroptosis: spontaneous abortion, pre-eclampsia, gestational diabetes mellitus, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, spontaneous preterm birth.

2 Molecular mechanisms of ferroptosis

2.1 Lipid peroxidation

Mammalian lipid bilayers consist of up to 62% of unsaturated fatty acids of which 35% are polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) (Hulbert et al., 2002). However, PUFA is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, PUFAs are necessary for cell membrane to maintain its fluidity (Gill and Valivety, 1997) or deposit in lipid droplets (LDs) in order to produce metabolic energy in case of insufficient energy sources (Thiele and Spandl, 2008). On the other hand, PUFAs, especially arachidonic acid (AA) and adrenic acid (AdA), promote lipid peroxidation under various pathophysiological contexts (Doll et al., 2017). Acyl-CoA synthetase long chain family member 4 (ACSL4) (Küch et al., 2014) and lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 3 (LPCAT3) (Hishikawa et al., 2008) are tightly linked to lipid peroxidation of AA/AdA. Firstly, ACSL4 catalyzes the ligation of CoA into free AA/AdA to form AA/AdA-CoA derivatives (Kagan et al., 2017). Then, AA/AdA-CoA are esterified into phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) by LPCAT3 to form arachidonic acid-phosphatidylethanolamines (AA/AdA-PE) (Hishikawa et al., 2008). Finally, toxic phospholipid hydroperoxides (PE-AA/AdA-OOH) are produced by the peroxidation of the AA/AdA-PE through non-enzymatically autoxidation or enzyme-mediated pathways (Dixon et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2016).

The non-enzymatic phospholipid (PL) autoxidation is iron-dependent lipid peroxidation. Hydroxyl radicals, produced by the interaction of Fe2+ and H2O2 (Fenton reaction), subtract hydrogen from lipid to form lipid radicals (L•) (Diggle, 2002). After that, the lipid radical combine with O2 to form a lipid peroxyl radical (LOO•), which then interacts with adjacent PUFAs to form lipid hydroperoxide (LOOH), and many electrophilic species such as malondialdehyde (MDA), and 4-hydroxynonenal (4HNE) (Rice-Evans and Burdon, 1993; Michalski et al., 2008).

Lipid peroxidation also occurs in enzyme-mediated processes. Lipoxygenases (LOXs), a dioxygenase containing non-heme iron, has six isoforms in humans: 15-LOX-1, 15-LOX-2, 12-LOX-1, 12-LOX-2, E3-LOX, and 5-LOX (Funk et al., 2002). Although the key role of LOXs in ferroptosis is still controversial, certain LOXs can catalyze the stereospecific addition of oxygen onto PUFAs (Kuhn et al., 2005), indicating LOXs may mediate ferroptosis. Indeed, LOX15, binding to the partner phosphatidylethanolamine-binding protein 1 (PEBP1), is of importance for erastin- or RSL3-induced ferroptosis (Wenzel et al., 2017). Furthermore, ferroptosis can be inhibited by some LOXs inhibitors, such as Zileuton, MK886, PD146176, Baicalein (Battista et al., 2012; Shah et al., 2018). However, some reported in vivo model of acute renal failure, 12/15- LOX deletion cannot eliminate the cell death of GPX4 knockout mouse (Friedmann Angeli et al., 2014; Brütsch et al., 2015). Therefore, the role of LOXs in ferroptosis should be further investigated. Other oxygenases, such as NADPH oxidases (NOXs) and cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase (POR), may also lead to ferroptosis. Apocynin and diphenyleneiodonium (DPI), two NOXs inhibitors, can directly mitigate ferroptotic cell death (Hou et al., 2019). Similarly, alogliptin and vildagliptin indirectly suppress NOXs activity mediated by dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4), reducing lipid peroxidation (Zhang et al., 2022a). POR, identified through CRISPR/Cas9-mediated suppressor screening, can play a role in erastin-, FIN56-, ML210-, or Ras selective lethal small molecule 3 (RSL3)-induced ferroptosis, as well (Zou et al., 2020).

2.2 Iron in ferroptosis

Iron overload is a hallmark of ferroptosis. Iron drives ferroptosis mainly by two ways. Iron may directly generate excessive lipid reactive oxygen species (ROS) through the Fenton reaction (Conrad and Pratt, 2019). What’s more, Fe2+ acts as a cofactor of LOXs or prolyl hydroxylase (Doll and Conrad, 2017), which are enzymes responsible for lipid peroxidation and oxygen homeostasis (Kagan et al., 2017). Consequently, Fe2+ promotes the production of lipid ROS and contributes to ferroptosis indirectly. Therefore, iron metabolism, including iron uptake, transportation, utilization, may affect cell susceptibility to ferroptosis. Firstly, Fe3+ imports by binding to transferrin (TF), which can be recognized by transferrin receptor-1 (TfR1) in the cell membrane. And then, Fe3+ endocytosis in endosomes, where it is reduced to Fe2+ by six-transmembrane epithelial antigens of the prostate 3 (STEAP3). Finally, Fe2+ is transported to the cytosolic labile iron pool via divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1) (El Hout et al., 2018). Fe2+ also comes from hemin and hemoglobin via the lysis of red blood cells, leading to ferroptosis (Kwon et al., 2015). It can be used in cellular processes or stored into ferritin, consisting of ferritin light chain (FTL) and ferritin heavy chain 1 (FTH1) (Ryu et al., 2017). But ferritin can be degraded by lysosomes through nuclear receptor coactivator 4 (NCOA4)-mediated ferritinophagy (Hou et al., 2016). Ferroportin (FPN1) is responsible for exporting iron (Donovan et al., 2000), resisting to ferroptosis.

2.3 Antioxidant systems

2.3.1 The SLC7A11-GSH-GPX4 axis

The SLC7A11-GSH-GPX4 axis is a classical signaling pathway of ferroptosis (Dixon et al., 2012). Glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4), a glutathione (GSH) -dependent selenoenzyme, functions as a phospholipid hydroperoxidase to reduce toxic PE-AA/AdA-OOH to the corresponding non-toxic phospholipid alcohol (PLOH), inhibiting ferroptosis (Ursini et al., 1985). However, the antioxidant activity of GPX4 demands the catalytic selenocysteine (Sec) residue at 46 (U46) and two electrons supplied mainly by GSH (Maiorino et al., 2018). Sec, encoded by the UGA codon, is a major form of selenium (Se) in the cell. Generally, it is present at active sites of enzymes, catalyzing redox reactions, thereby eliminating hydroperoxides (Santesmasses et al., 2020). In addition, Se can upregulate the expression of GPX4 through transcription factor AP-2 gamma (TFAP2C) and specificity protein 1 (SP1) (Alim et al., 2019). Truly, translation of GPX4 is attenuated in LRP8KO cells due to the limiting Se (Li et al., 2022a). GSH, as the reducing agent, is the substrate for the lipid repair function of GPX4, lowering the risk of ferroptosis. The biosynthesis of GSH is based on glutamate, glycine and cysteine, which is tightly correlated with its precursor cystine and system Xc− (Lu, 2013). The Xc− system is an antiporter on the cell membrane composed of SLC7A11 and SLC3A2, transporting glutamate outwards and cystine inwards at 1:1 ratio (Bannai, 1986). Thus, factors, directly or indirectly inhibiting GPX4, play a key role in inducing ferroptosis. Erastin inhibits its activity by binding to SLC7A11, reducing cystine import, thereby reducing GSH synthesis (Yang et al., 2014). Tumor suppressor genes TP53, BECN1, BAP1 downregulate the expression of SLC7A11 to induce ferroptosis (Jiang et al., 2015; Song et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2018). However, the nuclear transcription factor 2 (Nrf2) upregulates the expression of SLC7A11 to inhibit ferroptosis (Chen et al., 2017). High calcium and phosphate can downregulate the expression of GPX4, inducing ferroptosis (Ye et al., 2022b). RSL3 can covalently bind to GPX4, resulting in increasing lipid peroxidation (Yang et al., 2014). GPX4 also can be degraded by some compounds, such as FIN56, FINO2, plumbagin, SMG9 (Gaschler et al., 2018; Han et al., 2021; Sun et al., 2021; Zhan et al., 2022). Together, the SLC7A11-GSH-GPX4 axis is of great significance for ferroptosis.

2.3.2 The FSP1 pathway

The ferroptosis suppressor protein 1 (FSP1)–NAD(P)H–coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10) pathway, acting in parallel to the SLC7A11-GSH-GPX4 pathway, is a potent suppressor of lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis (Bersuker et al., 2019; Doll et al., 2019). FSP1, known as apoptosis-inducing factor mitochondrial 2 (AIFM2), plays a crucial role in the non-mitochondrial CoQ antioxidant system (Wu et al., 2002). As members of the AIF family, FSP1 contains a short N-terminal hydrophobic sequence and a canonical flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD)-dependent oxidoreductase domain, possessing NADH: ubiquinone oxidoreductase activity (Elguindy and Nakamaru-Ogiso, 2015). Ubiquinol, the reduced form of ubiquinone, known as CoQ10 traps lipid peroxyl radicals, thereby mediating lipid peroxidation. However, FSP1 catalyzes the catalyzing NADH: ubiquinone oxidoreductase reactions, reducing ubiquinol to CoQ10, which is a good radical-trapping antioxidant for lipid peroxides (Bersuker et al., 2019; Doll et al., 2019). Indeed, some reported that FSP1 inhibits ferroptosis in across hundreds of cancer cell lines and in mouse tumor models (Bersuker et al., 2019).

3 Ferroptosis inhibitors

Ferroptosis is associated with a great number of diseases. Multiple genes and signaling pathways, associated with lipid and iron metabolism, and antioxidant systems, play a role in inhibiting ferroptosis, providing new potential therapeutic drugs for these diseases (Table 1).

TABLE 1

| Compounds/drugs | Model | Mechanism | Potential for PRDs | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lipid peroxidation | ||||

| ferrostatin-1, liproxstatin-1, SRS16-86 | cell line: HT1080; HK-2; primary human renal proximal tubule epithelial cells; | inhibit lipid peroxidation | PE | Dixon et al. (2012), Friedmann Angeli et al. (2014) |

| deuterated PUFA | APP/PS1 mice | inhibit lipid peroxidation | NR | Raefsky et al. (2018) |

| thiazolidinediones | TAM-inducible Gpx4 −/− cells; TAM-inducible Gpx4−/− mice | decrease the level of AA-CoA/AdA-CoA | GDM | Doll et al. (2017) |

| zileuton | HT22 cells | inhibit 5-LOX | NR | Long et al. (2022) |

| vitamin E,α-Tocopherol | SD rats with PTZ-Induced Epilepsy; Gpx4flox/floxC57BL/6 mice; | inhibit 15-LOX | PE | Hu et al. (2021a), Zhang et al. (2022b) |

| baicalein | HT22 cells, TBI mice model | inhibit 12/15-LOX | NR | Probst et al. (2017), Kenny et al. (2019) |

| PD-146176 | human spermatozoa | inhibit 15-LOX | NR | Walters et al. (2018) |

| Iron | ||||

| deferiprone, deferoxamine, ciclopirox | HT-1080 | reduce intracellular iron | PE | Long et al. (2022) |

| eriodictyol | APPswe/PS1E9 transgenic mice; HT-22 hippocampal cells | reduced intracellular iron accumulation | NR | Li et al. (2022b) |

| Antioxidant systems | ||||

| β-mercaptoethanol | OT-1 CD8þ T cell | drive a highly efficient cystine/cysteine redox cycle. | NR | Sha et al. (2015) |

| selenium | BTBR mouse model of ASD | enhance the number of selenoproteins | ICP | Wu et al. (2022) |

| cycloheximide | B35 neuroblastoma cells; 9L gliosarcoma cells | increased levels of GSH | NR | Rashad et al. (2022) |

| XJB-5–131 | C57BL/6 mice of Renal I/R model | increase the expressions of GPX4 | NR | Zhao et al. (2020) |

| 1,25(OH)2D3 | zebrafish liver cell line | increase the expressions of GPX4 | SA, GDM, PE | Cheng et al. (2021) |

| astaxanthin | primary chondrocytes; SD rat model of osteoarthritis | increase the expressions of GPX4 | PE | Wang et al. (2022) |

| echinatin | primary rat hippocampal neurons; SD rats | increase the expressions of GPX4 | NR | Xu et al. (2022) |

| quercetin | KA-induced seizures in C57BL/6J mice; cell line: HT22 | increase the expressions of GPX4 | PE | Xie et al. (2022) |

| CoQ10, idebenone | NCI-H460; HT1080 cells; MDCK cells | inhibit lipid peroxidation | ICP | Bersuker et al. (2019), Doll et al. (2019), Schreiber et al. (2019) |

| Membrane repair | ||||

| vildagliptin | intracerebral hemorrhage C57BL/6 mice | inhibit DPP4 | NR | Zhang et al. (2022a) |

| Other antioxidants | ||||

| BAPTA-AM | cell line:HK-2 cells; TCE-sensitization BALB/c mice | inhibit lipid peroxidation | NR | Liu et al. (2022) |

Summary of ferroptosis inhibitors

PE, pre-eclampsia: gestational hypertension with proteinuria > 0.3g/L/day in the absence of a urinary tract infection or the abrupt onset of hypertension and proteinuria after 20 weeks of gestation (ACOG Practice Bulletin, 2019).

GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus: diabetes first diagnosed in the second or third trimester of pregnancy that is not clearly either preexisting type 1 or type 2 diabetes (American Diabetes Association, 2018).

ICP, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: characterized by maternal pruritus and increased serum bile acid concentrations, typically resolving postpartum (Chappell et al., 2019).

SA, spontaneous abortion: pregnancy loss at less than 20 weeks’ gestation in the absence of elective medical or surgical measures to terminate the pregnancy (Wilcox et al., 1988).

abrAbbreviations: AA, arachidonic acid; AdA, adrenic acid; PRDs, pregnancy related diseases; GPX4, Glutathione peroxidase 4; GSH, glutathione; LOX, lipoxygenase; PUFA, polyunsaturated fatty acid; SD, sprague-dawley.

3.1 Inhibition of lipid peroxidation

PUFAs, substrates of lipid peroxidation, are responsible for ferroptosis. Selectively bis-allylic deuterated PUFA, suppressing ferroptosis induced by RSL3 and erastin (Yang et al., 2016), is a promising therapeutic strategy against ferroptosis. Additionally, blocking the process of PUFAs incorporation into phospholipid membranes can reduce lipid peroxidation, like thiazolidinediones, rosiglitazone and Triacsin C (Van Horn et al., 2005; Angeli et al., 2017; Doll et al., 2017), which inhibits ACSL4. There are many LOXs inhibitors, such as vitamin E, α-Tocopherol, baicalein, PD-146176 (Probst et al., 2017; Walters et al., 2018; Kenny et al., 2019; Hu et al., 2021a; Zhang et al., 2022b), stopping the process of LOX-mediated lipid peroxidation, thereby resisting ferroptosis. Ferrostatins and liproxstatins are classical ferroptosis inhibitor, depressing lipid peroxidation (Zilka et al., 2017).

3.2 Iron chelator

Fe2+ overload in intracellular iron pools, like endoplasmic reticulum (ER), may trigger ferroptosis (Tang et al., 2021). However, intracellular iron accumulation is linked with the transport of extracellular iron. Recently, Li et al. found eriodictyol can significantly decrease TfR1 and FTH, and increase FPN, leading to resisting ferroptosis (Li et al., 2022b). Furthermore, iron chelators, such as deferoxamine (DFO), ciclopirox (CPX), and curcumin (Rainey et al., 2019) can reduce the concentration of Fe2+ (Yang and Stockwell, 2008), suppressing ferroptosis.

3.3 Antioxidant systems

Antioxidant systems protecting cell from oxidative damage in ferroptosis are associated with multiple enzymes and proteins, including SLC7A11-GSH-GPX4 axis, CoQ10 system (Kuang et al., 2020).

3.3.1 The SLC7A11-GSH-GPX4 axis

The SLC7A11-GSH-GPX4 axis is the main ferroptosis prevention system. The induction of GPX4 synthesis is a classic pathway to suppress ferroptosis, relating to cysteine, system Xc-, Se, GSH. The β-mercaptoethanol may play a role in inhibiting ferroptosis by driving a highly efficient cystine/cysteine redox cycle (Sha et al., 2015). Cycloheximide is a potent inhibitor of ferroptosis, by increasing the concentration of GSH (Rashad et al., 2022). The XJB-5-131 alleviates I/R-induced renal injury and inflammation in mice by increasing the expression of GPX4 (Zhao et al., 2020). Similarly, 1,25(OH)2D3, astaxanthin, and echinatin can become resistant to ferroptosis by increasing GPX4 level (Cheng et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2022; Xu et al., 2022). At the same time, the 5-(tetradecyloxy)-2-furoic Acid (TOFA) was also found to be a potent suppressor of ferroptosis, through inhibiting the loss of GPX4 (Shimada et al., 2016). Quercetin, a natural polyphenol, could attenuate seizure-induced neuron ferroptosis in vivo and in vitro at via the SIRT1/Nrf2/SLC7A11/GPX4 axis (Xie et al., 2022).

3.3.2 CoQ10 System

The FSP1–NAD(P)H–CoQ10 pathway, acting in parallel to the GPX4 axis, is a powerful antioxidant system in membrane structures (Teran et al., 2018). Idebenone, an analog of CoQ10, prevents ferroptosis caused by FIN56 or RSL3 (Shimada et al., 2016). Likewise, farnesyl pyrophosphate, an upstream product of CoQ10 synthesis, suppresses FIN56-induced ferroptosis (Shimada et al., 2016).

3.3.3 Other antioxidants

AIFM2, promoting CHMP5- and CHMP6-mediated ESCRT-III membrane repair, results in blocking ferroptosis (Dai et al., 2020). As reported, some antioxidant proteins may also resist to ferroptotic cell death, like peroxiredoxins (Qi et al., 2019; Lovatt et al., 2020), thioredoxin (Llabani et al., 2019). Cytosolic Ca2+ overload was a key mediator of ferroptosis (Chen et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2022). Recently, researchers found BAPTA-AM, an intracellular Ca2+ chelator, could rescued ferroptosis in HK-2 cells (Liu et al., 2022). Therefore, limiting oxidative damage of ferroptosis has been a promising therapeutic strategy for PRDs.

4 Role of ferroptosis in pregnancy related diseases

Recently, basic research on ferroptosis in PRDs has gradually increased. Studies have indicated that placenta is susceptible to ferroptosis. Primarily, lipid peroxidation is frequent in placental injury (Schoots et al., 2018); Secondly, trophoblasts are abundant of iron: syncytiotrophoblasts extraordinarily highly expressed TfR1 (Seligman et al., 1979). Furthermore, Zrt- and Irt-like protein 8 (ZIP8) and Zrt- and Irt-like protein 14 (ZIP14), both of which play a roles in exporting iron from placental endosomal into the cytosol, are found at high levels in human placenta (Jenkitkasemwong et al., 2012). Three reviews described details on the role of iron and ferroptosis in the placenta (Ng et al., 2019; Beharier et al., 2021; Zaugg et al., 2022). Finally, decreased GPX4 levels have been associated with human placental dysfunction (Zhang et al., 2020). Therefore, fully understanding the role of ferroptosis in placenta dysfunction may provide new treatment options for PRDs, including spontaneous abortion, PE, GDM, ICP, and spontaneous preterm birth (Figure 2).

4.1 Pre-eclampsia

4.1.1 Lipid peroxidation and pre-eclampsia

PE plays a leading role in maternal morbidity and mortality (Leitao et al., 2022). Ferroptosis has been related to the pathogenesis of PE (Chen et al., 2022). There are mounting evidence suggesting lipid peroxidation, is a major contributor for the damage of PE. A single-cell transcriptomics of the human placenta analysis indicated LPCAT3 and Sat1 (spermidine/spermine N1-acetyltransferase 1) highly expressed in trophoblasts (Ng et al., 2019), both of which are related to ferroptosis (Dixon et al., 2015; Ou et al., 2016). Irwinda, R., et al. reported that the level of PUFAs significantly increased in PE patients (Irwinda et al., 2021; Liao et al., 2022). Furthermore, in rats model of PE, the concentration of MDA, the end product of lipid peroxidation, in the placenta has increased dramatically (Zhang et al., 2020). Similarly, the levels of MDA in plasma and placenta are significantly elevated in PE patients (Aydin et al., 2004). To summarize, these studies suggest that lipid peroxidation leading to ferroptosis could contribute to PE.

4.1.2 Iron and pre-eclampsia

Iron overload is also associated with PE. Researchers have confirmed the concentration of plasma iron is higher in PE pregnancy than that in normal pregnancy (Liu et al., 2019). Yang et al., 2022a. reported the differentially expressed ferroptosis-related genes (FRGs) in early-onset PE were mainly enriched in iron-related pathways, including FTH1, FTL. Importantly, iron is abundant in trophoblasts under physiological conditions or in the context of iron deficiency (Sangkhae et al., 2020). What’s more, the expression of FPN1 of trophoblasts decreased under hypoxic conditions (Zhang et al., 2020), leading to the intracellular accumulation of Fe2+. Consequently, trophoblasts are vulnerable to ferroptosis. Ferrostatin-1 (Fer-1), a ferroptosis inhibitor, decreased the mortality rate of trophoblasts (Beharier et al., 2020). Similarly, the ferroptosis inhibitor improved the PE symptoms in a rat model, with the reduction of MDA (Zhang et al., 2020). Thus, reducing the concentration of Fe2+ might be a good way for PE treatment.

4.1.3 The SLC7A11-GSH-GPX4 axis and pre-eclampsia

Disorder of antioxidant system mediates ferroptosis in PE. A microarray analysis identified that miRNA-30b-5pm, which is in charge of reducing the expression of SLC7A11, upregulated in PE placental tissues. Also, they found SLC7A11 and GPX4 were decreased in PE placental tissues via GSE10588 data set (Zhang et al., 2020). In accordance with other studies, the levels of SLC7A11, GSH and GPX4 declined while MDA levels were significantly increased (El-Khalik et al., 2022; D'Souza et al., 2016), indicating ferroptosis is involved in the pathogenesis of PE through the SLC7A11-GSH-GPX4 axis. A genome-wide methylome analysis found the expression of ATF3, suppressing the system Xc− by binding to the SLC7A11 promoter (Wang et al., 2020), is higher in PE placenta than the normal placenta (Ching et al., 2014). As a result, human trophoblasts are susceptible to ferroptosis by the depletion or inhibition of GPX4 (Kajiwara et al., 2022). Additionally, pannexin 1 (Panx1) and toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), which had a negative correlation with SLC7A11, are demonstrated to induce ferroptosis in PE (El-Khalik et al., 2022). Conversely, anti-ferroptosis factors can protect trophoblasts against ferroptosis through the SLC7A11-GSH-GPX4 axis. The level of Nrf2, which is responsible for promoting transcriptions of SLC7A11 and GPX4 (Dong et al., 2020), is lower in PE rats (Ju et al., 2022). DJ-1 plays a protective role in the process of ferroptosis in PE via the Nrf2/GPX4 signaling pathway (Liao et al., 2022). These studies demonstrated that the SLC7A11-GSH-GPX4 axis plays a role in the pathogenesis of PE.

4.2 Gestational diabetes mellitus

4.2.1 Lipid peroxidation and gestational diabetes mellitus

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is common during pregnancy and is increasing in prevalence globally (Sweeting et al., 2022). The incidence of GDM ranges from 6.6% to 45.3% of pregnancies (Brown and Wyckoff, 2017) and one in six live births worldwide were complicated by GDM (Atlas, 2015). GDM is associated with long-lasting complications in the short and long term, such as macrosomia (Song et al., 2022), dystocia (Crowther et al., 2022), childhood obesity in the child (Choi et al., 2022), recurrence of GDM (Giuliani et al., 2022), developing type 2 diabetes (Vounzoulaki et al., 2020) and cardiovascular disease in the mother (Christensen et al., 2022). Emerging evidence suggests ferroptosis contributes to the pathogenesis of GDM (Han et al., 2020; Gautam et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2022c; Hu et al., 2022; Zaugg et al., 2022). The insulin sensitivity shifts depending on the requirements of pregnancy, which is an important metabolic adaptation during healthy pregnancy (Di Cianni et al., 2003). However, excessive insulin resistance in GDM promotes endogenous glucose production and the breakdown of fat stores, increasing the levels of blood glucose and free fatty acid (FFA) (Phelps et al., 1981). Indeed, glucose metabolism disorder is often accompanied by lipid metabolism disorder in GDM (Parhofer, 2015). A study indicated that women with GDM had significantly higher triglyceride (TG) concentrations (Hu et al., 2021b). In vitro model, the death rate of trophoblasts significantly increased after the co-treatment of high lipid (HL) and high glucose (HG). Furthermore, it was found that HL and HG can induce GDM in pregnant rats, leading to the damage of rats’ placenta (He et al., 2021). The expression of ACSL4 significantly increased in placental tissues, as well (Zheng et al., 2022). Consequently, excessive FFA of GDM may cause an increase in the level of lipid peroxidation, resulting in ferroptosis.

4.2.2 Iron and gestational diabetes mellitus

Iron overload, leading to oxidative stress damage, could promote the pathogenesis of GDM (Gautam et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2022c; Zaugg et al., 2022). As reported, both elevated plasma ferritin concentrations and iron supplementation in pregnant women having adequate iron stores are risk factors of GDM (Zhang et al., 2021). In GDM vivo model, the levels of iron deposition significantly increased (Zheng et al., 2022), inducing the production of ROS via the Fenton reaction. As a result, oxidative damage leads to the injury and ferroptosis of pancreatic β–cell in GDM (Gautam et al., 2021; Du et al., 2022). The SLC7A11-GSH-GPX4 axis also contributes to GDM. The serum lipid peroxidation was higher, while the serum GPX4 concentration was lower in GDM women (Mauri et al., 2021). In summary, mounting evidence may suggest that excessive iron, and reduced GPX4 levels, two hallmarks of ferroptosis, are associated with GDM. However, experiments testing this hypothesis are still lacking.

4.3 Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) is a complication, most occurs in the third trimester, in 0.3%–15% of pregnancies in various populations (Wikström Shemer et al., 2013). It is characterized by pruritus, elevated serum bile acid levels and liver transaminases, leading to meconium-stained amniotic fluid, fetal distress, preterm birth, and stillbirth (Wikström Shemer et al., 2013). There is increasing evidence that oxidative stress induced by bile acids leads to the pathogenesis of ICP (Sanhal et al., 2018). ICP patients had significantly lower levels of Se and GPX4 than normal pregnancies (Reyes et al., 2000; Hu et al., 2015). Moreover, patients with ICP had significantly higher level of MDA (Zhu et al., 2019). Analysis of differentially expressed ferroptosis-related genes in ICP and healthy pregnant showed EGFR, mediating ferroptosis, was higher upregulated in human placenta (Fang and Fang, 2022). Modification of oxidative stress caused by ferroptosis might be a treatment target for ICP. Further research, particularly in vivo and in vitro experiments, is needed to characterize the association between ferroptosis and ICP.

4.4 Other pregnancy-related disease

Excessive ferroptosis occurred in spontaneous abortion rat model with low levels of GSH, GPX4 and increased levels of TFR1, ACSL4 and MDA (Meihe et al., 2021). Some evidence also indicated spontaneous preterm birth is related to ferroptosis (Beharier et al., 2020). But few studies reported that the exact mechanism of ferroptosis and spontaneous abortion and spontaneous preterm birth are still unclear.

5 Potential medicines for ferroptosis in pregnancy related diseases

Trophoblast ferroptosis may provide a useful therapeutic target for pregnancy-related diseases. Quercetin, as an antioxidant, can significantly promote trophoblast invasion during early pregnancy via significantly increasing GSH levels (Ebegboni et al., 2019). Additionally, quercetin has positive effects on pre-eclampsia rats induced by L-NAME (Yang et al., 2019a; Yang et al., 2022b). Iron chelators, deferoxamine and ferrostatin-1, were indicated to decrease the concentration of placenta MDA in the PE rat mode, thereby blocking trophoblast ferroptosis (Beharier et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020). Similarly, vitamin E plays a role in the preventing PE by mitigating lipid peroxidation in placenta (Raijmakers et al., 2004). Thiazolidinediones, inhibiting ACSL4 against ferroptosis, is also oral antidiabetic drug by sensitizing tissue to the effects of insulin (Pollex and Hutson, 2011). A recently published case series demonstrate thiazolidinediones is safe during pregnancy (Haddad et al., 2008), indicating its potential therapeutic role for GDM. Trophoblasts ferroptosis may contribute to ICP, while the low concentration of Se is related to the pathogenesis of ICP (Reyes et al., 2000). Thus, Se, upregulating the expression of GPX4, can protect placental trophoblasts against oxidative stress, particularly ICP (Habibi et al., 2021). CoQ10 is significantly decreased in patients with ICP (Martinefski et al., 2014). Furthermore, CoQ10 supplementation improves estradiol-induced cholestasis in rats. CoQ10 supplementation is very well tolerated and has no clinically relevant toxic side effects in humans (Hidaka et al., 2008; Martinefski et al., 2020). Therefore, it would be an alternative therapy for women with ICP. Lack of 1,25(OH)2D3 is related to PRDs, which may result from ferroptosis, such as spontaneous abortion, GDM and PE (Bespalova et al., 2019; Li et al., 2019; de Souza and Pisani, 2020). Vitamin D elevated the level of GSH, GPX4 and reduced MDA through activation of the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway to suppresses ferroptosis. Therefore, vitamin D supplementation may be a strategy to improve PRDs. Previous studies reported astaxanthin significantly reduced the content of MDA in preeclamptic rats and trophoblast cell line (Xuan et al., 2014; Xuan et al., 2016; Fu et al., 2021). Certainly, drug efficacy and safety are quite important for pregnant woman and fetus. Further research may shed light on potential targeting drugs for ferroptosis in PRDs.

6 Conclusions and perspectives

Ferroptosis is a form of regulated cell death involving lipid metabolism, iron metabolism and antioxidant system, regulated by multiple genes and signaling pathways. PRDs are mainly associated with placenta dysfunction due to trophoblasts injury and death. Recently, an increasing number of experimental studies are exploring role of ferroptosis in PRDs in order to provide new potential therapeutic drugs and therapeutic targets for it. However, there are numerous problems that have not been elucidated on the association between ferroptosis and pregnancy related diseases. Firstly, the exact molecular mechanism of transplacental iron transport is not clear, though much work has been done on it. Secondly, ferroptosis is a form of cell death that is associated with lots of signaling pathways, like hypoxia signaling (Zou et al., 2019), AMP-activated protein kinase signaling (Li et al., 2020), E-cadherin-NF2-Hippo-YAP pathway (Yang et al., 2019b), and NRF2-KEAP1 pathway (Anandhan et al., 2020). However, the regulation of ferroptosis in placenta also remains a pressing challenge. Finally, we still do not know whether ferroptosis of trophoblasts leads to PRDs, or it is the execution pathway of PRDs. Therefore, extensive investigation is needed to explore it.

Statements

Author contributions

JX and CM conceived and designed the work. JX, FZ, XW, and CM wrote and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article, read, and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 82200084 and 81801485), the Sichuan Science and Technology Program (Grant Number 2023NSFSC1456), the Chinese Scholarship Council (grant number 202106240141), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, and Sichuan University postdoctoral interdisciplinary Innovation Fund.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

AA-CoA, arachidonic acid-CoA; AA-PE, arachidonic acid-phosphatidylethanolamine; AdA-CoA, adrenic acid-CoA; AdA-PE, adrenic acid-phosphatidylethanolamine; ACSL4, acyl-CoA synthetase longchain family member 4; AIFM2, apoptosis-inducing factor 2; CPX, ciclopirox; CHMP5, charged multivesicular body protein 5; CHMP6, charged multivesicular body protein 6; DFO, deferoxamine; DMT1, divalent metal transporter 1; ESCRT-III, endosomal sorting complexes required for transport-III; FTH1, ferritin heavy chain 1; FTL, ferritin light chain; GCLC, glutamate cysteine ligase, catalytic; GPX4, glutathione peroxidase 4; GSH, glutathione; GSS, glutathione synthetase; HMG-CoA, β-Hydroxy β-methylglutaryl-CoA; HMGCR,3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase; LDs, Lipid droplets; LOX, lipoxygenase; LPCAT3, lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 3; NCOA4, nuclear receptor coactivator 4; PL, phospholipid; RSL3, ras-selective lethal 3; ROS, reactive oxygen species; Se, selenium; STEAP3, six-transmembrane epithelial antigen of prostate 3; TF, transferrin; TfR1, transferrin receptor-1.

References

1

ACOG Practice Bulletin (2019). ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 202: Gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Obstet. Gynecol.133 (1), 1–e25. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003018

2

Alim I. Caulfield J. T. Chen Y. Swarup V. Geschwind D. H. Ivanova E. et al (2019). Selenium drives a transcriptional adaptive Program to block ferroptosis and treat stroke. Cell177 (5), 1262–1279. 10.1016/j.cell.2019.03.032

3

American Diabetes Association (2018). 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: Standards of medical care in diabetes-2018. Diabetes Care41 (1), S13–S27. 10.2337/dc18-S002

4

Anandhan A. Dodson M. Schmidlin C. J. Liu P. Zhang D. D. (2020). Breakdown of an ironclad defense system: The critical role of NRF2 in mediating ferroptosis. Cell Chem. Biol.27 (4), 436–447. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2020.03.011

5

Angeli J. P. F. Shah R. Pratt D. A. Conrad M. (2017). Ferroptosis inhibition: Mechanisms and opportunities. Trends Pharmacol. Sci.38 (5), 489–498. 10.1016/j.tips.2017.02.005

6

Atlas D. (2015). IDF diabetes atlas7th edn. Brussels, Belgium: International Diabetes Federation, 33.

7

Aydin S. Benian A. Madazli R. Uludag S. Uzun H. Kaya S. (2004). Plasma malondialdehyde, superoxide dismutase, sE-selectin, fibronectin, endothelin-1 and nitric oxide levels in women with preeclampsia. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol.113 (1), 21–25. 10.1016/S0301-2115(03)00368-3

8

Bannai S. (1986). Exchange of cystine and glutamate across plasma membrane of human fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem.261 (5), 2256–2263. 10.1016/s0021-9258(17)35926-4

9

Battista N. Meloni M. A. Bari M. Mastrangelo N. Galleri G. Rapino C. et al (2012). 5-Lipoxygenase-dependent apoptosis of human lymphocytes in the international space station: Data from the ROALD experiment. FASEB J.26 (5), 1791–1798. 10.1096/fj.11-199406

10

Beharier O. Kajiwara K. Sadovsky Y. (2021). Ferroptosis, trophoblast lipotoxic damage, and adverse pregnancy outcome. Placenta108, 32–38. 10.1016/j.placenta.2021.03.007

11

Beharier O. Tyurin V. A. Goff J. P. Guerrero-Santoro J. Kajiwara K. Chu T. et al (2020). PLA2G6 guards placental trophoblasts against ferroptotic injury. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.117 (44), 27319–27328. 10.1073/pnas.2009201117

12

Bersuker K. Hendricks J. M. Li Z. Magtanong L. Ford B. Tang P. H. et al (2019). The CoQ oxidoreductase FSP1 acts parallel to GPX4 to inhibit ferroptosis. Nature575 (7784), 688–692. 10.1038/s41586-019-1705-2

13

Bespalova O. Bakleicheva M. Kovaleva I. Tolibova G. Tral T. Kogan I. (2019). Expression of vitamin D and vitamin D receptor in chorionic villous in missed abortion. Gynecol. Endocrinol.35 (1), 49–55. 10.1080/09513590.2019.1653563

14

Brown F. M. Wyckoff J. (2017). Application of one-step IADPSG versus two-step diagnostic criteria for gestational diabetes in the real world: Impact on health services, clinical care, and outcomes. Curr. Diab. Rep.17 (10), 85. 10.1007/s11892-017-0922-z

15

Brütsch S. H. Wang C. C. Li L. Stender H. Neziroglu N. Richter C. et al (2015). Expression of inactive glutathione peroxidase 4 leads to embryonic lethality, and inactivation of the Alox15 gene does not rescue such knock-in mice. Antioxid. Redox Signal22 (4), 281–293. 10.1089/ars.2014.5967

16

Chappell L. C. Bell J. L. Smith A. Linsell L. Juszczak E. Dixon P. H. et al (2019). Ursodeoxycholic acid versus placebo in women with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (PITCHES): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet394 (10201), 849–860. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31270-X

17

Chen D. Tavana O. Chu B. Erber L. Chen Y. Baer R. et al (2017). NRF2 is a major target of ARF in p53-independent tumor suppression. Mol. Cell68 (1), 224–232. 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.09.009

18

Chen P. Wu Q. Feng J. Yan L. Sun Y. Liu S. et al (2020). Erianin, a novel dibenzyl compound in Dendrobium extract, inhibits lung cancer cell growth and migration via calcium/calmodulin-dependent ferroptosis. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther.5 (1), 51. 10.1038/s41392-020-0149-3

19

Chen Z. Kajiwara K. Sadovsky Y. (2022). Ferroptosis and its emerging role in pre-eclampsia. Antioxidants Basel11, 1282. 10.3390/antiox11071282

20

Cheng K. Huang Y. Wang C. (2021). 1,25(OH)(2)D(3) inhibited ferroptosis in zebrafish liver cells (ZFL) by regulating keap1-nrf2-GPx4 and NF-κB-hepcidin Axis. Int. J. Mol. Sci.22, 11334. 10.3390/ijms222111334

21

Ching T. Song M. A. Tiirikainen M. Molnar J. Berry M. Towner D. et al (2014). Genome-wide hypermethylation coupled with promoter hypomethylation in the chorioamniotic membranes of early onset pre-eclampsia. Mol. Hum. Reprod.20 (9), 885–904. 10.1093/molehr/gau046

22

Choi M. J. Yu J. Choi J. (2022). Maternal pre-pregnancy obesity and gestational diabetes mellitus increase the risk of childhood obesity. Child. (Basel)9, 928. 10.3390/children9070928

23

Christensen M. H. Rubin K. H. Petersen T. G. Nohr E. A. Vinter C. A. Andersen M. S. et al (2022). Cardiovascular and metabolic morbidity in women with previous gestational diabetes mellitus: A nationwide register-based cohort study. Cardiovasc Diabetol.21 (1), 179. 10.1186/s12933-022-01609-2

24

Cindrova-Davies T. Sferruzzi-Perri A. N. (2022). Human placental development and function. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol.131, 66–77. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2022.03.039

25

Conrad M. Pratt D. A. (2019). The chemical basis of ferroptosis. Nat. Chem. Biol.15 (12), 1137–1147. 10.1038/s41589-019-0408-1

26

Crowther C. A. Samuel D. Hughes R. Tran T. Brown J. Alsweiler J. M. (2022). Tighter or less tight glycaemic targets for women with gestational diabetes mellitus for reducing maternal and perinatal morbidity: A stepped-wedge, cluster-randomised trial. PLoS Med.19, e1004087. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1004087

27

D'Souza V. Rani A. Patil V. Pisal H. Randhir K. Mehendale S. et al (2016). Increased oxidative stress from early pregnancy in women who develop preeclampsia. Clin. Exp. Hypertens.38 (2), 225–232. 10.3109/10641963.2015.1081226

28

Dai E. Zhang W. Cong D. Kang R. Wang J. Tang D. (2020). AIFM2 blocks ferroptosis independent of ubiquinol metabolism. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.523 (4), 966–971. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.01.066

29

de Souza E. A. Pisani L. P. (2020). The relationship among vitamin D, TLR4 pathway and preeclampsia. Mol. Biol. Rep.47 (8), 6259–6267. 10.1007/s11033-020-05644-8

30

Di Cianni G. Miccoli R. VoLpe L. LenCioni C. Del Prato S. (2003). Intermediate metabolism in normal pregnancy and in gestational diabetes. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev.19 (4), 259–270. 10.1002/dmrr.390

31

Diggle C. P. (2002). In vitro studies on the relationship between polyunsaturated fatty acids and cancer: Tumour or tissue specific effects?Prog. Lipid Res.41 (3), 240–253. 10.1016/s0163-7827(01)00025-x

32

Dixon S. J. Lemberg K. M. Lamprecht M. R. Skouta R. Zaitsev E. M. Gleason C. E. et al (2012). Ferroptosis: An iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell149 (5), 1060–1072. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.042

33

Dixon S. J. Winter G. E. Musavi L. S. Lee E. D. Snijder B. Rebsamen M. et al (2015). Human haploid cell genetics reveals roles for lipid metabolism genes in nonapoptotic cell death. ACS Chem. Biol.10 (7), 1604–1609. 10.1021/acschembio.5b00245

34

Doll S. Conrad M. (2017). Iron and ferroptosis: A still ill-defined liaison. IUBMB Life69 (6), 423–434. 10.1002/iub.1616

35

Doll S. Freitas F. P. Shah R. Aldrovandi M. da Silva M. C. Ingold I. et al (2019). FSP1 is a glutathione-independent ferroptosis suppressor. Nature575 (7784), 693–698. 10.1038/s41586-019-1707-0

36

Doll S. Proneth B. Tyurina Y. Y. Panzilius E. Kobayashi S. Ingold I. et al (2017). ACSL4 dictates ferroptosis sensitivity by shaping cellular lipid composition. Nat. Chem. Biol.13 (1), 91–98. 10.1038/nchembio.2239

37

Dong H. Qiang Z. Chai D. Peng J. Xia Y. Hu R. et al (2020). Nrf2 inhibits ferroptosis and protects against acute lung injury due to intestinal ischemia reperfusion via regulating SLC7A11 and HO-1. Aging12 (13), 12943–12959. 10.18632/aging.103378

38

Donovan A. Brownlie A. Shepard J. Pratt S. J. Moynihan J. et al (2000). Positional cloning of zebrafish ferroportin1 identifies a conserved vertebrate iron exporter. Nature403 (6771), 776–781. 10.1038/35001596

39

Du G. Zhang Q. Huang X. Wang Y. (2022). Molecular mechanism of ferroptosis and its role in the occurrence and treatment of diabetes. Front. Genet.13, 1018829. 10.3389/fgene.2022.1018829

40

Ebegboni V. J. Balahmar R. M. Dickenson J. M. Sivasubramaniam S. D. (2019). The effects of flavonoids on human first trimester trophoblast spheroidal stem cell self-renewal, invasion and JNK/p38 MAPK activation: Understanding the cytoprotective effects of these phytonutrients against oxidative stress. Biochem. Pharmacol.164, 289–298. 10.1016/j.bcp.2019.04.023

41

El Hout M. Dos Santos L. Hamai A. Mehrpour M. (2018). A promising new approach to cancer therapy: Targeting iron metabolism in cancer stem cells. Semin. Cancer Biol.53, 125–138. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2018.07.009

42

El-Khalik S. R. A. Ibrahim R. R. Ghafar M. T. A. Shatat D. El-Deeb O. S. (2022). Novel insights into the slc7a11-mediated ferroptosis signaling pathways in preeclampsia patients: Identifying pannexin 1 and toll-like receptor 4 as innovative prospective diagnostic biomarkers. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet.39 (5), 1115–1124. 10.1007/s10815-022-02443-x

43

Elguindy M. M. Nakamaru-Ogiso E. (2015). Apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) and its family member protein, AMID, are rotenone-sensitive NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductases (NDH-2). J. Biol. Chem.290 (34), 20815–20826. 10.1074/jbc.M115.641498

44

Fan X. Zhang X. Liu L. C. Zhang S. Pelger C. B. Lughmani H. Y. et al (2022). Hemopexin accumulates in kidneys and worsens acute kidney injury by causing hemoglobin deposition and exacerbation of iron toxicity in proximal tubules. Kidney Int.102 (6), 1320–1330. 10.1016/j.kint.2022.07.024

45

Fang Y. Fang D. (2022). Comprehensive analysis of placental gene-expression profiles and identification of EGFR-mediated autophagy and ferroptosis suppression in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Gene834, 146594. 10.1016/j.gene.2022.146594

46

Friedmann Angeli J. P. Schneider M. Proneth B. Tyurina Y. Y. Tyurin V. A. Hammond V. J. et al (2014). Inactivation of the ferroptosis regulator Gpx4 triggers acute renal failure in mice. Nat. Cell Biol.16 (12), 1180–1191. 10.1038/ncb3064

47

Fu J. Y. Jing Y. Xiao Y. P. Wang X. H. Guo Y. W. Zhu Y. J. (2021). Astaxanthin inhibiting oxidative stress damage of placental trophoblast cells in vitro. Syst. Biol. Reprod. Med.67 (1), 79–88. 10.1080/19396368.2020.1824031

48

Funk C. D. Chen X. S. Johnson E. N. Zhao L. (2002). Lipoxygenase genes and their targeted disruption. Prostagl. Other Lipid Mediat68-69, 303–312. 10.1016/s0090-6980(02)00036-9

49

Gaschler M. M. Andia A. A. Liu H. Csuka J. M. Hurlocker B. Vaiana C. A. et al (2018). FINO2 initiates ferroptosis through GPX4 inactivation and iron oxidation. Nat. Chem. Biol.14 (5), 507–515. 10.1038/s41589-018-0031-6

50

Gautam S. Alam F. Moin S. Noor N. Arif S. H. (2021). Role of ferritin and oxidative stress index in gestational diabetes mellitus. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord.20 (2), 1615–1619. 10.1007/s40200-021-00911-2

51

Gill I. Valivety R. (1997). Polyunsaturated fatty acids, Part 1: Occurrence, biological activities and applications. Trends Biotechnol.15 (10), 401–409. 10.1016/S0167-7799(97)01076-7

52

Giuliani C. Sciacca L. Biase N. D. Tumminia A. Milluzzo A. Faggiano A. et al (2022). Gestational diabetes mellitus pregnancy by pregnancy: Early, late and nonrecurrent GDM. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract.188, 109911. 10.1016/j.diabres.2022.109911

53

Habibi N. Jankovic-Karasoulos T. Leemaqz S. Y. L. Francois M. Zhou S. J. Leifert W. R. et al (2021). Effect of iodine and selenium on proliferation, viability, and oxidative stress in HTR-8/SVneo placental cells. Biol. Trace Elem. Res.199 (4), 1332–1344. 10.1007/s12011-020-02277-7

54

Haddad G. F. Jodicke C. Thomas M. A. Williams D. B. Aubuchon M. (2008). Case series of rosiglitazone used during the first trimester of pregnancy. Reprod. Toxicol.26 (2), 183–184. 10.1016/j.reprotox.2008.08.001

55

Han D. Jiang L. Gu X. Huang S. Pang J. Wu Y. et al (2020). SIRT3 deficiency is resistant to autophagy-dependent ferroptosis by inhibiting the AMPK/mTOR pathway and promoting GPX4 levels. J. Cell. Physiol.235 (11), 8839–8851. 10.1002/jcp.29727

56

Han L. Bai L. Fang X. Liu J. Kang R. Zhou D. et al (2021). SMG9 drives ferroptosis by directly inhibiting GPX4 degradation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.567, 92–98. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2021.06.038

57

He H. Liu Y. Sun M. (2021). Nesfatin-1 alleviates high glucose/high lipid-induced injury of trophoblast cells during gestational diabetes mellitus. Bioengineered12 (2), 12789–12799. 10.1080/21655979.2021.2001205

58

Hidaka T. Fujii K. Funahashi I. Fukutomi N. Hosoe K. (2008). Safety assessment of coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10). Biofactors32 (1-4), 199–208. 10.1002/biof.5520320124

59

Hishikawa D. Shindou H. Kobayashi S. Nakanishi H. Taguchi R. Shimizu T. (2008). Discovery of a lysophospholipid acyltransferase family essential for membrane asymmetry and diversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.105 (8), 2830–2835. 10.1073/pnas.0712245105

60

Hou L. Huang R. Sun F. Zhang L. Wang Q. (2019). NADPH oxidase regulates paraquat and maneb-induced dopaminergic neurodegeneration through ferroptosis. Toxicology417, 64–73. 10.1016/j.tox.2019.02.011

61

Hou W. Xie Y. Song X. Sun X. Lotze M. T. Zeh H. J. et al (2016). Autophagy promotes ferroptosis by degradation of ferritin. Autophagy12 (8), 1425–1428. 10.1080/15548627.2016.1187366

62

Hu B. Li D. Tang D. Shangguan Y. Cao Y. Guo R. et al (2022). Integrated proteome and acetylome analyses unveil protein features of gestational diabetes mellitus and preeclampsia. Proteomics22, e2200124. 10.1002/pmic.202200124

63

Hu J. Gillies C. L. Lin S. Stewart Z. A. Melford S. E. Abrams K. R. et al (2021). Association of maternal lipid profile and gestational diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 292 studies and 97,880 women. EClinicalMedicine34, 100830. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100830

64

Hu Q. Zhang Y. Lou H. Ou Z. Liu J. Duan W. et al (2021). GPX4 and vitamin E cooperatively protect hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells from lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis. Cell Death Dis.12 (7), 706. 10.1038/s41419-021-04008-9

65

Hu Y. Y. Liu J. C. Xing A. Y. (2015). Oxidative stress markers in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: A prospective controlled study. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci.19 (17), 3181–3186.

66

Hulbert A. J. Rana T. Couture P. (2002). The acyl composition of mammalian phospholipids: An allometric analysis. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol.132 (3), 515–527. 10.1016/s1096-4959(02)00066-0

67

Irwinda R. Hiksas R. Siregar A. A. Saroyo Y. B. Wibowo N. (2021). Long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid (LC-PUFA) status in severe preeclampsia and preterm birth: A cross sectional study. Sci. Rep.11 (1), 14701. 10.1038/s41598-021-93846-w

68

Jenkitkasemwong S. Wang C. Y. Mackenzie B. Knutson M. D. (2012). Physiologic implications of metal-ion transport by ZIP14 and ZIP8. Biometals25 (4), 643–655. 10.1007/s10534-012-9526-x

69

Jiang L. Kon N. Li T. Wang S. J. Su T. Hibshoosh H. et al (2015). Ferroptosis as a p53-mediated activity during tumour suppression. Nature520 (7545), 57–62. 10.1038/nature14344

70

Ju Y. Feng Y. Hou X. Wu L. Yang H. Zhang H. et al (2022). Combined apocyanin and aspirin treatment activates the PI3K/Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway and ameliorates preeclampsia symptoms in rats. Hypertens. Pregnancy41 (1), 39–50. 10.1080/10641955.2021.2014518

71

Kagan V. E. Mao G. Qu F. Angeli J. P. F. Doll S. Croix C. S. et al (2017). Oxidized arachidonic and adrenic PEs navigate cells to ferroptosis. Nat. Chem. Biol.13 (1), 81–90. 10.1038/nchembio.2238

72

Kajiwara K. Beharier O. Chng C. P. Goff J. P. Ouyang Y. St Croix C. M. et al (2022). Ferroptosis induces membrane blebbing in placental trophoblasts. J. Cell Sci.135, jcs255737. 10.1242/jcs.255737

73

Kenny E. M. Fidan E. Yang Q. Anthonymuthu T. S. New L. A. Meyer E. A. et al (2019). Ferroptosis contributes to neuronal death and functional outcome after traumatic brain injury. Crit. Care Med.47 (3), 410–418. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003555

74

Kuang F. Liu J. Tang D. Kang R. (2020). Oxidative damage and antioxidant defense in ferroptosis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol.8, 586578. 10.3389/fcell.2020.586578

75

Küch E. M. Vellaramkalayil R. Zhang I. Lehnen D. Brugger B. Sreemmel W. et al (2014). Differentially localized acyl-CoA synthetase 4 isoenzymes mediate the metabolic channeling of fatty acids towards phosphatidylinositol. Biochim. Biophys. Acta1841 (2), 227–239. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2013.10.018

76

Kuhn H. Saam J. Eibach S. Holzhutter H. G. Ivanov I. Walther M. (2005). Structural biology of mammalian lipoxygenases: Enzymatic consequences of targeted alterations of the protein structure. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.338 (1), 93–101. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.08.238

77

Kwon M. Y. Park E. Lee S. J. Chung S. W. (2015). Heme oxygenase-1 accelerates erastin-induced ferroptotic cell death. Oncotarget6 (27), 24393–24403. 10.18632/oncotarget.5162

78

Lei G. Zhuang L. Gan B. (2022). Targeting ferroptosis as a vulnerability in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer22 (7), 381–396. 10.1038/s41568-022-00459-0

79

Leitao S. Manning E. Greene R. A. Corcoran P. Maternal Morbidity Advisory Group (2022). Maternal morbidity and mortality: An iceberg phenomenon. Bjog129 (3), 402–411. 10.1111/1471-0528.16880

80

Li C. Dong X. Du W. Shi X. Chen K. Zhang W. et al (2020). LKB1-AMPK axis negatively regulates ferroptosis by inhibiting fatty acid synthesis. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther.5 (1), 187. 10.1038/s41392-020-00297-2

81

Li G. Lin L. Wang Y. L. Yang H. (2019). 1,25(OH)2D3 protects trophoblasts against insulin resistance and inflammation via suppressing mTOR signaling. Reprod. Sci.26 (2), 223–232. 10.1177/1933719118766253

82

Li L. Li W. J. Zheng X. R. Liu Q. L. Du Q. Lai Y. J. et al (2022). Eriodictyol ameliorates cognitive dysfunction in APP/PS1 mice by inhibiting ferroptosis via vitamin D receptor-mediated Nrf2 activation. Mol. Med.28 (1), 11. 10.1186/s10020-022-00442-3

83

Li Z. Ferguson L. Deol K. K. Roberts M. A. Magtanong L. Hendricks J. M. et al (2022). Ribosome stalling during selenoprotein translation exposes a ferroptosis vulnerability. Nat. Chem. Biol.18 (7), 751–761. 10.1038/s41589-022-01033-3

84

Liao T. Xu X. Ye X. Yan J. (2022). DJ-1 upregulates the Nrf2/GPX4 signal pathway to inhibit trophoblast ferroptosis in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Sci. Rep.12, 2934. 10.1038/s41598-022-07065-y

85

Liu J. X. Chen D. Li M. X. Hua Y. (2019). Increased serum iron levels in pregnant women with preeclampsia: A meta-analysis of observational studies. J. Obstet. Gynaecol.39 (1), 11–16. 10.1080/01443615.2018.1450368

86

Liu Z. Ma J. Zuo X. Zhang X. Hong Y. Cai S. et al (2022). C5b-9 mediates ferroptosis of tubular epithelial cells in trichloroethylene-sensitization mice. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf.244, 114020. 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2022.114020

87

Llabani E. Hicklin R. W. Lee H. Y. Motika S. E. Crawford L. A. Weerapana E. et al (2019). Diverse compounds from pleuromutilin lead to a thioredoxin inhibitor and inducer of ferroptosis. Nat. Chem.11 (6), 521–532. 10.1038/s41557-019-0261-6

88

Long L. Guo H. Chen X. Liu Y. Wang R. Zheng X. et al (2022). Advancement in understanding the role of ferroptosis in rheumatoid arthritis. Front. Physiol.13, 1036515. 10.3389/fphys.2022.1036515

89

Lovatt M. Adnan K. Kocaba V. Dirisamer M. Peh G. S. L. Mehta J. S. (2020). Peroxiredoxin-1 regulates lipid peroxidation in corneal endothelial cells. Redox Biol.30, 101417. 10.1016/j.redox.2019.101417

90

Lu S. C. (2013). Glutathione synthesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta1830 (5), 3143–3153. 10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.09.008

91

Maiorino M. Conrad M. Ursini F. (2018). GPx4, lipid peroxidation, and cell death: Discoveries, rediscoveries, and open issues. Antioxid. Redox Signal.29 (1), 61–74. 10.1089/ars.2017.7115

92

Martinefski M. R. Rodriguez M. R. Buontempo F. Lucangioli S. E. Bianciotti L. G. Tripodi V. P. (2020). Coenzyme Q 10 supplementation: A potential therapeutic option for the treatment of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Eur. J. Pharmacol.882, 173270. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2020.173270

93

Martinefski M. R. Scioscia S. Contin M. D. Samassa P. Lucangioli S. E. Tripodi V. P. (2014). A simple microHPLC-UV method for the simultaneous determination of retinol and α-tocopherol in human plasma. Application to intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Anal. Methods6 (10), 3365–3369. 10.1039/c4ay00058g

94

Mauri F. Schepkens C. Lapouge G. Drogat B. Song Y. Pastushenko I. et al (2021). NR2F2 controls malignant squamous cell carcinoma state by promoting stemness and invasion and repressing differentiation. Nat. Cancer2 (11), 1152–1169. 10.1038/s43018-021-00287-5

95

Meihe L. Shan G. Minchao K. Xiaoling W. Peng A. Xili W. et al (2021). The ferroptosis-NLRP1 inflammasome: The vicious cycle of an adverse pregnancy. Front. Cell Dev. Biol.9, 707959. 10.3389/fcell.2021.707959

96

Michalski M. C. Calzada C. Makino A. Michaud S. Guichardant M. (2008). Oxidation products of polyunsaturated fatty acids in infant formulas compared to human milk–a preliminary study. Mol. Nutr. Food Res.52 (12), 1478–1485. 10.1002/mnfr.200700451

97

Miyamoto H. D. Ikeda M. Ide T. Tadokoro T. Furusawa S. Abe K. et al (2022). Iron overload via heme degradation in the endoplasmic reticulum triggers ferroptosis in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. JACC Basic Transl. Sci.7 (8), 800–819. 10.1016/j.jacbts.2022.03.012

98

Ng S. W. Norwitz S. G. Norwitz E. R. (2019). The impact of iron overload and ferroptosis on reproductive disorders in humans: Implications for preeclampsia. Int. J. Mol. Sci.20, 3283. 10.3390/ijms20133283

99

Ou Y. Wang S. J. Li D. Chu B. Gu W. (2016). Activation of SAT1 engages polyamine metabolism with p53-mediated ferroptotic responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.113, E6806–E6812. 10.1073/pnas.1607152113

100

Parhofer K. G. (2015). Interaction between glucose and lipid metabolism: More than diabetic dyslipidemia. Diabetes Metab. J.39 (5), 353–362. 10.4093/dmj.2015.39.5.353

101

Phelps R. L. Metzger B. E. Freinkel N. (1981). Carbohydrate metabolism in pregnancy. XVII. Diurnal profiles of plasma glucose, insulin, free fatty acids, triglycerides, cholesterol, and individual amino acids in late normal pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol.140 (7), 730–736.

102

Pollex E. K. Hutson J. R. (2011). Genetic polymorphisms in placental transporters: Implications for fetal drug exposure to oral antidiabetic agents. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol.7 (3), 325–339. 10.1517/17425255.2011.553188

103

Probst L. Dachert J. Schenk B. Fulda S. (2017). Lipoxygenase inhibitors protect acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells from ferroptotic cell death. Biochem. Pharmacol.140, 41–52. 10.1016/j.bcp.2017.06.112

104

Qi W. Li Z. Xia L. Dai J. Zhang Q. Wu C. et al (2019). LncRNA GABPB1-AS1 and GABPB1 regulate oxidative stress during erastin-induced ferroptosis in HepG2 hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Sci. Rep.9 (1), 16185. 10.1038/s41598-019-52837-8

105

Raefsky S. M. Furman R. Milne G. Pollock E. Axelsen P. Mattson M. P. et al (2018). Deuterated polyunsaturated fatty acids reduce brain lipid peroxidation and hippocampal amyloid β-peptide levels, without discernable behavioral effects in an APP/PS1 mutant transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol. Aging66, 165–176. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2018.02.024

106

Raijmakers M. T. Dechend R. Poston L. (2004). Oxidative stress and preeclampsia: Rationale for antioxidant clinical trials. Hypertension44 (4), 374–380. 10.1161/01.HYP.0000141085.98320.01

107

Rainey N. E. Moustapha A. Saric A. Nicolas G. Sureau F. Petit P. X. (2019). Iron chelation by curcumin suppresses both curcumin-induced autophagy and cell death together with iron overload neoplastic transformation. Cell Death Discov.5, 150. 10.1038/s41420-019-0234-y

108

Rashad S. Byrne S. R. Saigusa D. Xiang J. Zhou Y. Zhang L. et al (2022). Codon usage and mRNA stability are translational determinants of cellular response to canonical ferroptosis inducers. Neuroscience501, 103–130. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2022.08.009

109

Reyes H. Baez M. E. Gonzalez M. C. Hernandez I. Palma J. Ribalta J. et al (2000). Selenium, zinc and copper plasma levels in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, in normal pregnancies and in healthy individuals, in Chile. J. Hepatol.32 (4), 542–549. 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80214-7

110

Rice-Evans C. Burdon R. (1993). Free radical-lipid interactions and their pathological consequences. Prog. Lipid Res.32 (1), 71–110. 10.1016/0163-7827(93)90006-i

111

Ryan S. K. Zelic M. Han Y. Teeple E. Chen L. Sadeghi M. et al (2022). Microglia ferroptosis is regulated by SEC24B and contributes to neurodegeneration. Nat. Neurosci.26, 12–26. 10.1038/s41593-022-01221-3

112

Ryu M. S. Zhang D. Protchenko O. Shakoury-Elizeh M. Philpott C. C. (2017). PCBP1 and NCOA4 regulate erythroid iron storage and heme biosynthesis. J. Clin. Invest.127 (5), 1786–1797. 10.1172/JCI90519

113

Sangkhae V. Fisher A. L. Wong S. Koenig M. D. Tussing-Humphreys L. Chu A. et al (2020). Effects of maternal iron status on placental and fetal iron homeostasis. J. Clin. Invest.130 (2), 625–640. 10.1172/JCI127341

114

Sanhal C. Y. Daglar K. Kara O. Yilmaz Z. V. Turkmen G. G. Erel O. et al (2018). An alternative method for measuring oxidative stress in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: Thiol/disulphide homeostasis. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med.31 (11), 1477–1482. 10.1080/14767058.2017.1319922

115

Santesmasses D. Mariotti M. Gladyshev V. N. (2020). Tolerance to selenoprotein loss differs between human and mouse. Mol. Biol. Evol.37 (2), 341–354. 10.1093/molbev/msz218

116

Schoots M. H. Gordijn S. J. Scherjon S. A. van Goor H. Hillebrands J. L. (2018). Oxidative stress in placental pathology. Placenta69, 153–161. 10.1016/j.placenta.2018.03.003

117

Schreiber R. Buchholz B. Kraus A. Schley G. Scholz J. Ousingsawat J. et al (2019). Lipid peroxidation drives renal cyst growth in vitro through activation of TMEM16A. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol.30 (2), 228–242. 10.1681/ASN.2018010039

118

Seligman P. A. Schleicher R. B. Allen R. H. (1979). Isolation and characterization of the transferrin receptor from human placenta. J. Biol. Chem.254 (20), 9943–9946. 10.1016/s0021-9258(19)86649-8

119

Sha L. K. Sha W. Kuchler L. Daiber A. Giegerich A. K. Weigert A. et al (2015). Loss of Nrf2 in bone marrow-derived macrophages impairs antigen-driven CD8(+) T cell function by limiting GSH and Cys availability. Free Radic. Biol. Med.83, 77–88. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.02.004

120

Shah R. Shchepinov M. S. Pratt D. A. (2018). Resolving the role of lipoxygenases in the initiation and execution of ferroptosis. ACS Cent. Sci.4 (3), 387–396. 10.1021/acscentsci.7b00589

121

Shimada K. Skouta R. Kaplan A. Yang W. S. Hayano M. Dixon S. J. et al (2016). Global survey of cell death mechanisms reveals metabolic regulation of ferroptosis. Nat. Chem. Biol.12 (7), 497–503. 10.1038/nchembio.2079

122

Song X. Chen L. Zhang S. Liu Y. Wei J. Wang T. et al (2022). Gestational diabetes mellitus and high triglyceride levels mediate the association between pre-pregnancy overweight/obesity and macrosomia: A prospective cohort study in central China. Nutrients14, 3347. 10.3390/nu14163347

123

Song X. Zhu S. Chen P. Hou W. Wen Q. Liu J. et al (2018). AMPK-mediated BECN1 phosphorylation promotes ferroptosis by directly blocking system Xc- activity. Curr. Biol.28 (15), 2388–2399. 10.1016/j.cub.2018.05.094

124

Sun Y. Berleth N. Wu W. Schlutermann D. Deitersen J. Stuhldreier F. et al (2021). Fin56-induced ferroptosis is supported by autophagy-mediated GPX4 degradation and functions synergistically with mTOR inhibition to kill bladder cancer cells. Cell Death Dis.12 (11), 1028. 10.1038/s41419-021-04306-2

125

Sweeting A. Wong J. Murphy H. R. Ross G. P. (2022). A clinical update on gestational diabetes mellitus. Endocr. Rev.43 (5), 763–793. 10.1210/endrev/bnac003

126

Tang D. Chen X. Kang R. Kroemer G. (2021). Ferroptosis: Molecular mechanisms and health implications. Cell Res.31 (2), 107–125. 10.1038/s41422-020-00441-1

127

Teran E. Hernandez I. Tana L. Teran S. Galaviz-Hernandez C. Sosa-Macias M. et al (2018). Mitochondria and coenzyme Q10 in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Front. Physiol.9, 1561. 10.3389/fphys.2018.01561

128

Thiele C. Spandl J. (2008). Cell biology of lipid droplets. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol.20 (4), 378–385. 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.05.009

129

Ursini F. Maiorino M. Gregolin C. (1985). The selenoenzyme phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta839 (1), 62–70. 10.1016/0304-4165(85)90182-5

130

Van Horn C. G. Caviglia J. M. Li L. O. Wang S. Granger D. A. Coleman R. A. (2005). Characterization of recombinant long-chain rat acyl-CoA synthetase isoforms 3 and 6: Identification of a novel variant of isoform 6. Biochemistry44 (5), 1635–1642. 10.1021/bi047721l

131

Vounzoulaki E. Khunti K. Abner S. C. Tan B. K. Davies M. J. Gillies C. L. (2020). Progression to type 2 diabetes in women with a known history of gestational diabetes: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Bmj369, m1361. 10.1136/bmj.m1361

132

Walters J. L. H. De Iuliis G. N. Dun M. D. Aitken R. J. McLaughlin E. A. Nixon B. et al (2018). Pharmacological inhibition of arachidonate 15-lipoxygenase protects human spermatozoa against oxidative stress. Biol. Reprod.98 (6), 784–794. 10.1093/biolre/ioy058

133

Wang L. Liu Y. Du T. Yang H. Lei L. Guo M. et al (2020). ATF3 promotes erastin-induced ferroptosis by suppressing system Xc. Cell Death Differ.27 (2), 662–675. 10.1038/s41418-019-0380-z

134

Wang X. Liu Z. Peng P. Gong Z. Huang J. Peng H. (2022). Astaxanthin attenuates osteoarthritis progression via inhibiting ferroptosis and regulating mitochondrial function in chondrocytes. Chem. Biol. Interact.366, 110148. 10.1016/j.cbi.2022.110148

135

Wenzel S. E. Tyurina Y. Y. Zhao J. St Croix C. M. Dar H. H. Mao G. et al (2017). PEBP1 wardens ferroptosis by enabling lipoxygenase generation of lipid death signals. Cell171 (3), 628–641. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.044

136

Wikström Shemer E. Marschall H. U. Ludvigsson J. F. StephanssOn O. (2013). Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy and associated adverse pregnancy and fetal outcomes: A 12-year population-based cohort study. Bjog120 (6), 717–723. 10.1111/1471-0528.12174

137

Wilcox A. J. Weinberg C. R. O'Connor J. F. Baird D. D. Schlatterer J. P. Canfield R. E. et al (1988). Incidence of early loss of pregnancy. N. Engl. J. Med.319 (4), 189–194. 10.1056/NEJM198807283190401

138

Wu H. Luan Y. Wang H. Zhang P. Liu S. Wang P. et al (2022). Selenium inhibits ferroptosis and ameliorates autistic-like behaviors of BTBR mice by regulating the Nrf2/GPx4 pathway. Brain Res. Bull.183, 38–48. 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2022.02.018

139

Wu M. Xu L. G. Li X. Zhai Z. Shu H. B. (2002). AMID, an apoptosis-inducing factor-homologous mitochondrion-associated protein, induces caspase-independent apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem.277 (28), 25617–25623. 10.1074/jbc.M202285200

140

Xie R. Zhao W. Lowe S. Bentley R. Hu G. Mei H. et al (2022). Quercetin alleviates kainic acid-induced seizure by inhibiting the Nrf2-mediated ferroptosis pathway. Free Radic. Biol. Med.191, 212–226. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2022.09.001

141

Xu Z. You Y. Tang Q. Zeng H. Zhao T. Wang J. et al (2022). Echinatin mitigates sevoflurane-induced hippocampal neurotoxicity and cognitive deficits through mitigation of iron overload and oxidative stress. Pharm. Biol.60 (1), 1915–1924. 10.1080/13880209.2022.2123941

142

Xuan R. R. Niu T. T. Chen H. M. (2016). Astaxanthin blocks preeclampsia progression by suppressing oxidative stress and inflammation. Mol. Med. Rep.14 (3), 2697–2704. 10.3892/mmr.2016.5569

143

Xuan R.-r. Wu W. Chen H. M. (2014). Effect of astaxanthin on preeclampsia rat model. Yao Xue Xue Bao49 (10), 1400–1405.

144

Yang N. Wang Q. Ding B. Gong Y. Wu Y. Sun J. et al (2022). Expression profiles and functions of ferroptosis-related genes in the placental tissue samples of early- and late-onset preeclampsia patients. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth22 (1), 87. 10.1186/s12884-022-04423-6

145

Yang S. Song L. Shi X. Zhao N. Ma Y. (2019). Ameliorative effects of pre-eclampsia by quercetin supplement to aspirin in a rat model induced by L-NAME. Biomed. Pharmacother.116, 108969. 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.108969

146

Yang S. Zhang J. Chen D. Ding J. Zhang Y. Song L. (2022). Quercetin supplement to aspirin attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced pre-eclampsia-like impairments in rats through the NLRP3 inflammasome. Drugs R. D.22 (4), 271–279. 10.1007/s40268-022-00402-6

147

Yang W. H. Ding C. K. C. Sun T. Rupprecht G. Lin C. C. Hsu D. et al (2019). The hippo pathway effector TAZ regulates ferroptosis in renal cell carcinoma. Cell Rep.28 (10), 2501–2508. 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.07.107

148

Yang W. S. Kim K. J. Gaschler M. M. Patel M. Shchepinov M. S. Stockwell B. R. (2016). Peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids by lipoxygenases drives ferroptosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.113, E4966–E4975. 10.1073/pnas.1603244113

149

Yang W. S. SriRamaratnam R. Welsch M. E. Shimada K. Skouta R. Viswanathan V. S. et al (2014). Regulation of ferroptotic cancer cell death by GPX4. Cell156 (1-2), 317–331. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.010

150

Yang W. S. Stockwell B. R. (2008). Synthetic lethal screening identifies compounds activating iron-dependent, nonapoptotic cell death in oncogenic-RAS-harboring cancer cells. Chem. Biol.15 (3), 234–245. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.02.010

151

Ye J. Peng J. Liu K. Zhang T. Huang W. (2022). MCTR1 inhibits ferroptosis by promoting NRF2 expression to attenuate hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol.323, G283–G293. 10.1152/ajpgi.00354.2021

152

Ye Y. Chen A. Li L. Liang Q. Wang S. Dong Q. et al (2022). Repression of the antiporter SLC7A11/Glutathione/Glutathione Peroxidase 4 axis drives ferroptosis of vascular smooth muscle cells to facilitate vascular calcification. Kidney Int.102 (6), 1259–1275. 10.1016/j.kint.2022.07.034

153

Zaugg J. Solenthaler F. Albrecht C. (2022). Materno-fetal iron transfer and the emerging role of ferroptosis pathways. Biochem. Pharmacol.202, 115141. 10.1016/j.bcp.2022.115141

154

Zhan S. Lu L. Pan S. S. Wei X. Q. Miao R. R. Liu X. H. et al (2022). Targeting NQO1/GPX4-mediated ferroptosis by plumbagin suppresses in vitro and in vivo glioma growth. Br. J. Cancer127 (2), 364–376. 10.1038/s41416-022-01800-y

155

Zhang H. He Y. Wang J. X. Chen M. H. Xu J. J. Jiang M. H. et al (2020). miR-30-5p-mediated ferroptosis of trophoblasts is implicated in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Redox Biol.29, 101402. 10.1016/j.redox.2019.101402

156

Zhang X. Wu M. Zhong C. Huang L. Zhang Y. Chen R. et al (2021). Association between maternal plasma ferritin concentration, iron supplement use, and the risk of gestational diabetes: A prospective cohort study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr.114 (3), 1100–1106. 10.1093/ajcn/nqab162

157

Zhang X. Wu S. Guo C. Guo K. Hu Z. Peng J. et al (2022). Vitamin E exerts neuroprotective effects in pentylenetetrazole kindling epilepsy via suppression of ferroptosis. Neurochem. Res.47 (3), 739–747. 10.1007/s11064-021-03483-y

158

Zhang Y. Lu Y. Jin L. (2022). Iron metabolism and ferroptosis in physiological and pathological pregnancy. Int. J. Mol. Sci.23, 9395. 10.3390/ijms23169395

159

Zhang Y. Shi J. Liu X. Feng L. Gong Z. Koppula P. et al (2018). BAP1 links metabolic regulation of ferroptosis to tumour suppression. Nat. Cell Biol.20 (10), 1181–1192. 10.1038/s41556-018-0178-0

160

Zhang Y. Zhang X. Wee Yong V. Xue M. (2022). Vildagliptin improves neurological function by inhibiting apoptosis and ferroptosis following intracerebral hemorrhage in mice. Neurosci. Lett.776, 136579. 10.1016/j.neulet.2022.136579

161

Zhao Z. Wu J. Xu H. Zhou C. Han B. Zhu H. et al (2020). XJB-5-131 inhibited ferroptosis in tubular epithelial cells after ischemia-reperfusion injury. Cell Death Dis.11 (8), 629. 10.1038/s41419-020-02871-6

162

Zheng Y. Hu Q. Wu J. (2022). Adiponectin ameliorates placental injury in gestational diabetes mice by correcting fatty acid oxidation/peroxide imbalance-induced ferroptosis via restoration of CPT-1 activity. Endocrine75 (3), 781–793. 10.1007/s12020-021-02933-5

163

Zhou Q. Yang L. Li T. Wang K. Huang X. Shi J. et al (2022). Mechanisms and inhibitors of ferroptosis in psoriasis. Front. Mol. Biosci.9, 1019447. 10.3389/fmolb.2022.1019447

164

Zhu P. Zhao S. M. Li Y. Z. Guo H. Wang L. Tian P. (2019). Correlation of lipid peroxidation and ATP enzyme on erythrocyte membrane with fetal distress in the uterus in patients with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci.23 (6), 2318–2324. 10.26355/eurrev_201903_17371

165

Zilka O. Shah R. Li B. Friedmann Angeli J. P. Griesser M. Conrad M. et al (2017). On the mechanism of cytoprotection by ferrostatin-1 and liproxstatin-1 and the role of lipid peroxidation in ferroptotic cell death. ACS Cent. Sci.3 (3), 232–243. 10.1021/acscentsci.7b00028

166

Zou Y. Graham E. T. Deik A. A. Eaton J. K. Wang W. et al (2020). Cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase contributes to phospholipid peroxidation in ferroptosis. Nat. Chem. Biol.16 (3), 302–309. 10.1038/s41589-020-0472-6

167

Zou Y. Palte M. J. Deik A. A. Li H. Eaton J. K. Wang W. et al (2019). A GPX4-dependent cancer cell state underlies the clear-cell morphology and confers sensitivity to ferroptosis. Nat. Commun.10 (1), 1617. 10.1038/s41467-019-09277-9

Summary

Keywords

ferroptosis, molecular mechanisms, pregnancy related diseases, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP), therapeutic potential

Citation

Xu J, Zhou F, Wang X and Mo C (2023) Role of ferroptosis in pregnancy related diseases and its therapeutic potential. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 11:1083838. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2023.1083838

Received

29 October 2022

Accepted

20 February 2023

Published

08 March 2023

Volume

11 - 2023

Edited by

Joseph Thomas Opferman, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, United States

Reviewed by

Huizhen Zhang, Zhengzhou University, China

Nathalie Le Floch, Université de Versailles Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines, France

Updates

Copyright

© 2023 Xu, Zhou, Wang and Mo.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Chunheng Mo, chunhengmo@gmail.com; Xiaodong Wang, wangxd_scu@sina.com

This article was submitted to Cell Death and Survival, a section of the journal Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.