Abstract

Recent studies have demonstrated that stem cells have attracted much attention due to their special abilities of proliferation, differentiation and self-renewal, and are of great significance in regenerative medicine and anti-aging research. Hence, finding natural medicines that intervene the fate specification of stem cells has become a priority. Ginsenosides, the key components of natural botanical ginseng, have been extensively studied for versatile effects, such as regulating stem cells function and resisting aging. This review aims to summarize recent progression regarding the impact of ginsenosides on the behavior of adult stem cells, particularly from the perspective of proliferation, differentiation and self-renewal.

1 Introduction

Panax ginseng (Panax ginseng C. A. Mey.), is a perennial herb of the Araliaceae family (de Oliveira Zanuso et al., 2022). This plant is widely cultivated in East Asia, particularly in China, Japan, and South Korea, due to its characteristic of being both a food and a medicine (Ichim and de Boer, 2020). Ginseng contains ginsenosides, polysaccharides, proteins, polypeptides, amino acids and other chemical components, among which ginsenosides are the main medicinal components (Lee et al., 2019). Currently, around 200 types of ginsenosides have been reported (Ratan et al., 2021). Based on the classification of ginsenosides by glycoside type, ginsenosides generally be compartmentalized into two categories: dammarane-type tetracyclic triterpene and oleanane-type pentacyclic triterpene saponins (Hou et al., 2021). Dammarane-type ginsenosides are the primary types and biologically active components of ginsenosides, which are divided into protopanaxadiol (PPD) types (including ginsenosides Ra1, Ra2, Ra3, Rb1, Rb2, Rb3, Rc, Rd, Rg3, Rh2, F2, compound K, malonyl-Rb1, malonyl-Rb2, malonyl-Rc and malonyl-Rd, etc.) and protopanaxatriol (PPT) types (including ginsenosides Re, Rf, Rg1, Rg2, F1 and Rh1, etc.) (Pan et al., 2018). In contrast, oleanane-type ginsenosides (including Ro, Rh3, Ri, etc.) are rare in ginseng species (Zhang H. et al., 2022). The experimental pharmacological research of ginsenosides have shown that the number of sugar residues contained in the branched, the position of glycosides, and their stereoselectivity all affect the pharmacological activity of ginsenoside monomers (Piyasirananda et al., 2021; Yousof Ali et al., 2021; Ali et al., 2022). Oral administration of ginsenosides is the major approach, but they are not easily absorbed by themselves with low bioavailability (Won et al., 2019). On the contrary, a large number of enzymes or gut microbiota can convert ginsenosides into deglycosylated products with a higher bioavailability and pharmacological activity that can be easily absorbed by human body (Yang L. et al., 2020). Ginsenosides have been found to possess a range of pharmacological effects, such as anti-aging (de Oliveira Zanuso et al., 2022), anti-tumor (Wong et al., 2015), hematopoietic recovery (He et al., 2021), promotion of osteogenesis (Wu et al., 2022), and neuroprotection (Rokot et al., 2016). In clinical trials, ginsenosides have been beneficial to the treatment of acute ischemic stroke, cancer, and chronic kidney disease, and can prompt oxidative stress or inflammation caused by exercise challenges (Table 1). Although ginsenosides exhibit various positive physiological activities, this review will focus on the relationship between ginsenosides and stem cells.

TABLE 1

| Component | Application | Effect | Mechanism | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rd | AIS | neuroprotection | microglial proteasome activity and sequential inflammation↓ | Zhang et al. (2016) |

| Rg3 | AL | anti-angiogenic | PI3K/Akt and ERK1/2 pathways↓ | Zeng et al. (2014) |

| Rb1 | CKD | alleviate kidney dysfunction | oxidative stress and inflammation↓ | Xu et al. (2017) |

| Rg1 | sports challenge | reduce oxidative damage and inflammation | TBA activity↓ and TNF-α mRNA↓ and IL-10 mRNA↑ | Hou et al. (2015) |

| Rg1 | exercise resistance | induces immune stimulation and reduces skeletal muscle aging | p16INK4a and MPO mRNA levels↓ | Lee et al. (2021) |

Clinical efficacy of ginsenosides.

AIS, acute ischemic stroke; AL, acute leukemia; CKD, chronic kidney disease.

Stem cells, encompassing both adult stem cells and embryonic varieties, are essential for developing human tissues and maintaining homeostasis (Zakrzewski et al., 2019). Their unique properties of self-renewal, high proliferation, and differentiation into multiple lineages make them attractive for a variety of applications, such as cell replacement as well as tissue and organ renewal in regenerative medicine (Brassard and Lutolf, 2019), exploration of regulatory mechanisms during embryonic development (Weatherbee et al., 2021), therapy for various diseases (Sinenko et al., 2021), the establishment of disease models (Sterneckert et al., 2014) and drug screening and development (Kumar et al., 2021). Notably, the fate specification of stem cells (proliferation, differentiation and self-renewal) is involved in the regulation of the body’s biological process. An imbalance in fate specification can lead to the emergence and progression of aging or even disease (Chandel et al., 2016). Excessive proliferation of stem cells can lead to the development of tumors and cancers (Najafi et al., 2019), while impaired self-renewal and differentiation of stem cells can limit the potential of tissue and organ regeneration and damage repair, such as in the case of aging and nervous system injury (De et al., 2021; Sivandzade and Cucullo, 2021). Consequently, understanding the regulation of stem cells fate is indispensable for the prevention of aging and many diseases. The stem cell niche refers to the microenvironment that maintains the proliferation, differentiation and self-renewal of stem cells (Hicks and Pyle, 2023). Stem cells can receive signals from the ecological niche and respond accordingly, which plays an important role in supporting and coordinating the activities of stem cells (Chacón-Martínez et al., 2018). Ginsenosides inhibit inflammatory responses and reduce oxidative stress to improve the stem cells niche (Hu et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2020). Also, ginsenosides can promote stem cell proliferation, differentiation into specific cell types, or self-renewal, thus regulating stem cell function (He et al., 2019; He and Yao, 2021). In this review, we summarize the effects of various ginsenosides on adult stem cells, especially mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), neural stem cells (NSCs) and cancer stem cells (CSCs), thereby elucidating the underlying mechanisms of ginsenosides in regulating fate specification of stem cells.

2 Transport and metabolism in stem cell niche of ginsenosides

The stem cell niche refers to the microenvironment at a specific location in a tissue or organ, which provides the necessary support and regulation for stem cells to maintain their proliferation, differentiation and self-renewal capabilities (Chacón-Martínez et al., 2018). The niche consists of stromal cells and the factors they secrete, such as adhesion molecules, soluble factors (cytokines, growth factors, metabolites, and nutrients), and matrix proteins. In addition, physical factors such as calcium ions and oxygen concentration also influence the characteristics of the stem cell niche. Recently the transport and metabolism of prototypical ginsenosides or ginsenoside metabolites in various types of stem cell niches have received extensive attention. ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters (especially ABCB1 and ABCG2) are clinically important transporters and drug efflux pumps, and their expression affects the differentiation activities of NSC stem cells (Lin et al., 2006). Specifically, downregulation of ABCB1 (also known as P-glycoprotein, p-gp) or ABCG2 (BCRP) expression promotes the differentiation of NSCs into astrocytes or neurons (Lin et al., 2006). Ginsenosides and their metabolites (CK, PPD, and PPT) have been studied to be potential inhibitors of p-gp and BCRP (Jin et al., 2006; Li et al., 2014). Those findings suggest that ginsenoside metabolites may antagonize ABC transporter expression, thereby benefiting NSC differentiation. Furthermore, overexpression of ABC transporters in CSC supports drug resistance (Li et al., 2010). The inhibition of ginsenosides on the efflux effect of ABC transporters may be one of the means to promote the sensitivity of CSCs to chemotherapeutic drugs. In addition, the enzymes involved in drug metabolism are mainly cytochrome P450 (CYP450), including CYP2C9, CYP3A4, etc. The inhibition of CYP450 prolongs the metabolism time of the drug in the body and increases the blood drug concentration. CYP450 is highly expressed in the bone marrow niche (HSC living environment) (Zhang Y. et al., 2013). The competitive inhibition of ginsenoside metabolites (CK, PPD, and PPT) on the activity of liver drug enzymes (CYP2C9, CYP3A4) may be the reason why they reside in the bone marrow niche and exert their pharmacological effects, thereby regulating HSC function (Liu et al., 2006). Recently, the transport of ginsenosides in the NSC niche was found that the active transport of ginsenoside Rb1 to brain microvascular endothelial cells, the cellular component of the NSC niche, was dependent on the glucose transporter GLUT1 (Wang et al., 2018). This finding suggests that upregulation of GLUT1 can increase the bioavailability of ginsenosides in NSCs and their niche. In the future, more in vivo experiments are needed to screen and verify the key enzymes/proteins related to the transport and metabolism of ginsenosides in stem cells and niches, which will help the uptake of ginsenosides by stem cells.

3 Effects of ginseng on different types of stem cells

Stem cells are pluripotent cells with the capacity for self-renewal, self-replication, and differentiation into multiple cell types in a suitable microenvironment, which are divided into two forms according to developmental stages: embryonic stem cells and adult stem cells. Considering that embryonic stem cells are subject to ethical restrictions, are prone to self-differentiation, and may have abnormal karyotypes after many passages, the research on the effect of ginsenosides on stem cells mainly focuses on adult stem cells (Scott and Reijo Pera, 2008). Adult stem cells, including hematopoietic, neural, and mesenchymal stem cells, are slow-dividing and quiescent cells with low proliferative rates and are the source of adult tissue (Gurusamy et al., 2018). Additionally, adult tissue stem cells can turn into cancer stem cells (White and Lowry, 2015), in solid tumors, the acquisition of cancer stem cells phenotype can be achieved through epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) (Shibue and Weinberg, 2017). The wide application of stem cells in regenerative medicine has attracted much attention. At first, stem cells were transplanted into the human body to repair damaged tissues, utilizing their potential for self-replication and multi-directional differentiation (Giri et al., 2019). Furthermore, advancements in stem cells reprogramming technology have led to increased use of stem cells for the restoration of aging cells, that is, stem cells can restore proliferate, differentiate, and self-renewal ability to delay the aging process (Alle et al., 2021). Recently, stem cells were suggested as a promising therapeutic option for various diseases, including but not limited to neurodegenerative diseases, cancer, stroke, myocardial ischemia (Yamashita and Abe, 2016; Michler, 2018; Sivandzade and Cucullo, 2021; Yin et al., 2021). Meanwhile, ginsenosides have been proven to slow the pathological process of these diseases and improve the condition (Huang et al., 2019; Wang R. et al., 2020; Yang JE. et al., 2020; Yao and Guan, 2022). In recent times, research studies have demonstrated the significant regulatory impact of ginsenosides on the self-renewal, differentiation, and proliferation of stem cells, thereby highlighting their potential for clinical use in improving the field of stem cells research (Table 2).

TABLE 2

| Cell type | Derive | Saponins | Effect | Targets/pathways | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSCs | colon | 20(R)-Rg3 | stemness and EMT↓ | SNAIL signal axis↓ | Phi et al. (2019b) |

| colon | Rd | stemness and EMT↓ | EGFR signal axis↓ | Phi et al. (2019a) | |

| colon | CK | stemness and cancer metastasis↓ | Nur77-Akt feedforward signaling↓ | Zhang et al. (2022b) | |

| lung | Rk1/Rg5 | EMT↓ | Smad and NF-κB/ERK↓ | Kim et al. (2021) | |

| breast | Rg3 | stemness and self-renewal↓ | Akt mediated self-renewal↓ | Oh et al. (2019) | |

| skin/liver | Rh2 | cell growth↓ | Autophagy↑; β-catenin↓ | Liu et al. (2015b), Yang et al. (2016) | |

| ovarian | Rb1 | self-renewal↓ | Wnt/β-catenin↓ | Deng et al. (2017) | |

| LSCs | CD34(+) CD38(−) LSCs | Rg1 | proliferation↓ and cellular senescence↑ | SIRT1/TSC2↑;p16INK4a↑ and hTERT↓ | Tang et al. (2020a), Tang et al. (2021) |

| MSCs | human adipose | Rg1 | proliferation↑ and adipogenic differentiation↑ | Adipocytokine↑, IL-17↓ | Xu et al. (2022) |

| bone marrow | Rg1 | aging↓ | NRF2 and Akt↑; GSK-3β phosphorylation ↓ and Wnt↓ | Wang et al. (2020b), Wang et al. (2021) | |

| bone marrow | Rg1 | osteogenic differentiation↑ | GR/BMP-2↑ | Gu et al. (2016) | |

| bone marrow | Rg1 | oxidative stress-induced apoptosis↓ | PI3K/Akt↑ | Hu et al. (2016) | |

| bone marrow | Rb1 | migration↑ | SDF-1/CXCR4 axis and PI3K/Akt↑ | Liu et al. (2022b) | |

| bone marrow | 20(S)-Rb2 | Dex-induced apoptosis↓ | GPR120↑, Ras-ERK1/2↑ | Gao et al. (2015) | |

| human umbilical cord | Rg1 | proliferation↑ and differentiation to NSCs↑ | Wnt/β-catenin↓ and Notch↓ | Xiao et al. (2022) | |

| muscle | Rb1 | oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction↓ | NF-κB↓ | Dong et al. (2022) | |

| HSCs | Sca-1(+) HSC/HPCs | Rg1 | HSCs aging↓ | SIRT6↑, NF-κB↓; SIRT1-FOXO3 and SIRT3-SOD2↑; oxidative stress↓ and Wnt/β-catenin↑; p16(INK4a)-Rb and p19(Arf)-p53-p21(Cip/Waf1)↓; p53-p21-Rb signal↓ | Chen et al. (2014), Yue et al. (2014), Tang et al. (2015), Li et al. (2016), Cai et al. (2018), Tang et al. (2020b), Zhou et al. (2020b), Wang et al. (2022a) |

| NSCs | - | Rg1 | aging↓ | Wnt/β-catenin↓; Akt/mTOR↓ | Chen et al. (2018), Xiang et al. (2019) |

| - | 20(S)-PPD | proliferation↓ and differentiation↑ | cell cycle↓, autophagy↑ | Chen et al. (2020) | |

| endogenous | CK | neurogenesis↑ | LXRα↑ | Zhou et al. (2020a) |

Changes and effects of ginsenosides on the physiological behavior of various stem cells.

CK, Compound K.

3.1 Mesenchymal stem cells

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are the progenitors of numerous cell types and have the capacity to proliferate and differentiate into a variety of cell lineages such as osteoblasts, adipocytes, myoblasts, and others (Xie et al., 2020).

3.1.1 Effect on differentiation of MSCs

Ginsenosides have shown the potential to induce differentiation of MSCs in vitro, especially in inducing osteogenic differentiation, which is the consequence of expressing or activating genes/transcription factors and signaling pathways related to osteogenic differentiation (He et al., 2019). The role of BMP-2/Smad pathway in MSCs osteogenic differentiation has been fully confirmed (Aquino-Martínez et al., 2017). As an indispensable growth factor for driving osteogenic differentiation, BMP-2 can activate the intracellular Smad pathway to form Smad complexes that enter the nucleus and promote the expression of the osteogenic transcription factor RUNX2 (Wang et al., 2017). Such the BMP-2/Smad signaling pathway can be activated by ginsenoside Rg1 to promote osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs), which is mediated by glucocorticoid receptor (GR) nuclear translocation (Gu et al., 2016). In addition, the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway is a key pathway that regulates the osteogenic differentiation of MSCs by regulating the localization of β-catenin, thereby regulating the expression of downstream osteogenesis-related proteins and genes. GSK-3β is an intermediary of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, and its high activity negatively affects the stability and transcriptional activity of β-catenin, blocks the activation state of the signaling pathway, and thus regulates the function and fate of stem cells. Currently, researchers believe that ginsenosides regulate the osteogenic differentiation of MSCs by regulating the Wnt signaling pathway. For instance, ginsenoside Rg1 can regulate the differentiation capacity of MSCs, stimulate bone and cartilage formation, by inhibiting the phosphorylation of GSK-3β and reducing the excessive activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in aging cells (Wang Z. et al., 2020). Conversely, ginsenoside compound K (CK) (the main metabolite of original propanediol ginsenoside in gut bacteria) activates the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in vitro and promotes the expression of the downstream Wnt target gene Runx2 (osteogenic transcription factor), inducing the osteogenic differentiation of rat bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (rBMSCs) (Ding et al., 2022). In view of the fact that ginsenosides have two sides to the regulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in promoting osteogenic differentiation of MSCs, that is, they show differences in different states (aging or normal) of MSCs. Future detailed functional exploration of individual members of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway will help to understand its regulatory mechanism.

Adipose tissue-derived MSCs (ADSCs) are also quite common in clinical practice. Ginsenoside Rg1-promoted cartilage gene expression in ADSCs in vitro induces cartilage phenotype differentiation (Xu et al., 2015; Guo et al., 2023). Co-administration of ginsenoside Rg1 and platelet-rich fibrin elevates cytokines (VEGF, HIF-1α) in human ADSCs niche and promotes soft tissue regeneration (Xu et al., 2016). Ginsenoside Rg1 can also improve the ADSC niche mediated by adipokine and IL-17 signaling pathways, and promote the adipogenic differentiation of human ADSCs (Xu et al., 2022). These results indicate that ginsenoside may expand MSCs by regulating MSC niche.

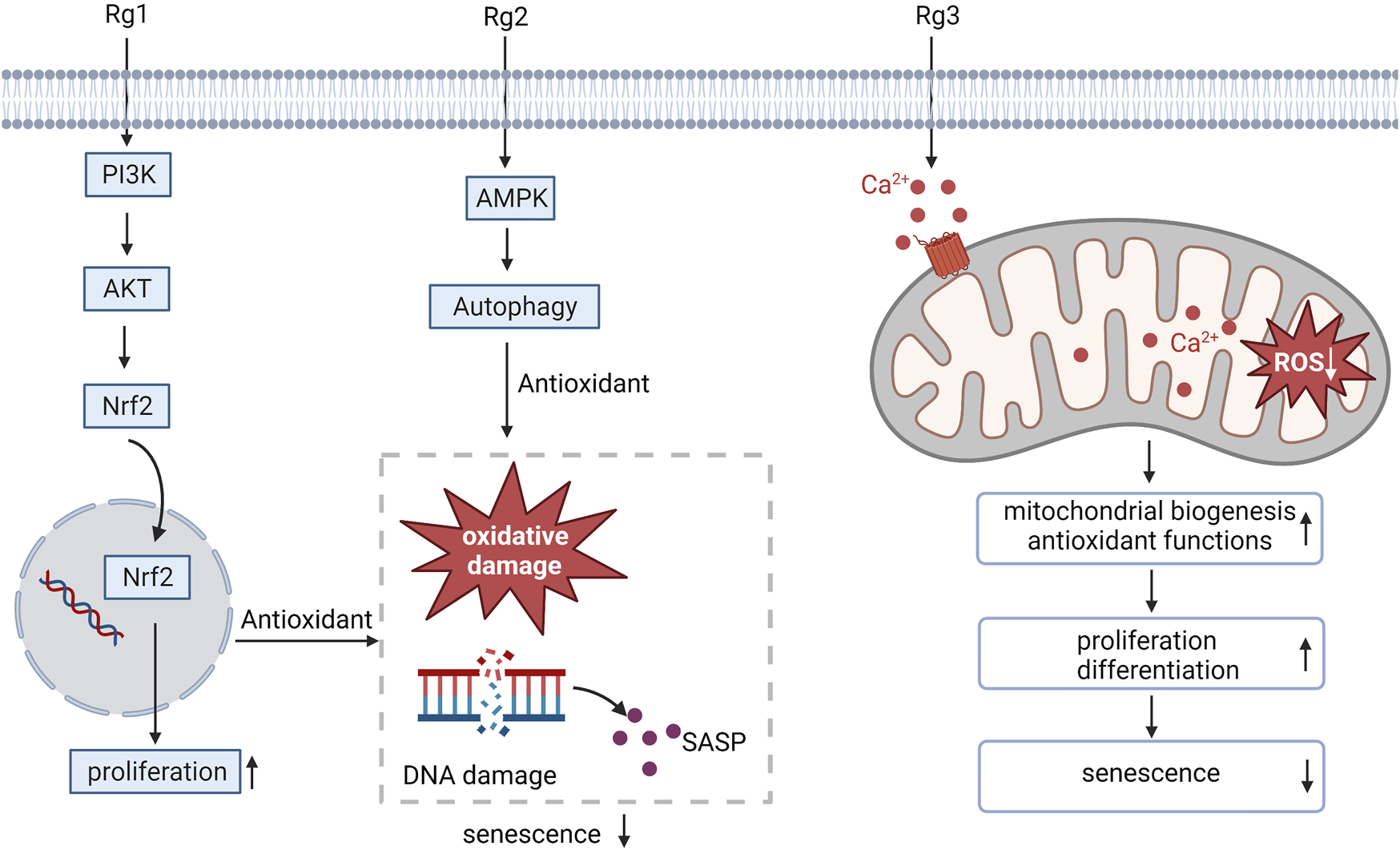

3.1.2 Effect on the proliferation and differentiation of MSCs in the aging process

Oxidative stress is the key contributor to the aging of stem cells (Chen et al., 2017). Ginsenoside Rg1 has been proven to promote superior antioxidant and anti-inflammatory capabilities, which can promote BMSC proliferation and improve the anti-aging hematopoietic microenvironment (Hu et al., 2015). Similarly, the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) resulting from DNA damage and oxidative damage associated with the aging of MSCs can be inhibited by ginsenoside Rg1, which promotes MSC proliferation by enhancing its antioxidant capacity, the activation of Nrf2 and PI3K/Akt is required for this process to occur (Wang et al., 2021). Ginsenoside Rg2 activates AMPK-mediated autophagy restores pig MSCs proliferation and inhibits oxidative stress-induced replicative senescence in pig MSCs (Che et al., 2023). Ginsenoside Rg3 mainly enhances the biogenesis ability of mitochondria and antioxidant function by promoting Ca2+ concentration properly, thus improving proliferation and differentiation potential and preventing human MSCs from aging (Hong et al., 2020). These results suggest that administration of ginsenosides may be a promising approach to counteract MSC aging by intervening in oxidative stress-related pathways (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1

Ginsenosides resist oxidative stress, regulate MSC proliferation and differentiation, and alleviate MSC aging. SASP, senescence-associated secretory phenotype.

3.2 Neutral stem cells

During central nervous system (CNS) development, neural stem cells (NSCs) are capable of generating neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes (Vieira et al., 2018). Recently, the use of neural stem cells therapy has emerged as a novel approach to treating diverse neurological disorders and is an ideal approach for treating neurodegenerative diseases and CNS injuries (Liu Y et al., 2020).

3.2.1 Effect on proliferation and differentiation of NSCs

Ginsenoside Rg1 increases the activity of NSE, a neuron biomarker, in transplanted NSCs, implying neuron-like differentiation (Li et al., 2015). Similarly, the key to ginsenoside Rb1 regulating the progression of neurodegenerative diseases is to increase the levels of biomarkers such as Nestin (marking NSC), GFAP (marking astrocytes) and NSE in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) rat models, and promote NSC proliferation and differentiation into astrocytes and neurons (Zhao et al., 2018). However, high levels of NSE have been shown to induce nerve injury and neuroblastoma, and the specific mechanism of how ginsenoside promotes NSE expression to exert neuroprotective effects needs to be further elucidated. Even though most ginsenosides are difficult to penetrate the blood-brain barrier due to their large molecular weight, their neuroprotective effects have been confirmed by a large number of experimental studies (Xie et al., 2018). The underlying mechanism may involve in improving the niche of NSCs. Nerve growth factor (NGF), a neurotrophic factor in the NSCs niche, can induce the differentiation of NSCs derived from the brain (Regalado-Santiago et al., 2016). Ginsenoside Rg1 precisely acts as an analog of NGF, attenuating oxygen and glucose deprivation-induced nerve injury and promoting proliferation and glial-like differentiation of cortical NSCs (Gao et al., 2017).

3.2.2 Effect on proliferation and differentiation of NSCs in the aging process

Recently, the function of WNT/β-catenin in the CNS has been studied and dysregulation of its signaling can lead to the production and aggregation of β-amyloid (Aβ) (Aghaizu et al., 2020). Ginseng total saponins extract and its intestinal metabolite 20(S)-protopanaxadiol (PPD) jointly induce the phosphorylation of GSK-3β (ser9), activate the Wnt/GSK-3β/β-catenin pathway to promote NSC proliferation and differentiation, thereby improving cognitive impairment in AD by replacing damaged neurons (Lin et al., 2020; Lin et al., 2022). However, in LiCl-induced NSC senescence, ginsenoside Rg1-dependent downregulation of phosphorylated GSK-3β expression interfered with the activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, thereby promoting NSC proliferation and delaying senescence (Xiang et al., 2019). Screening potential Wnt/GSK-3β/β-catenin -targeted activators/inhibitors in ginsenosides will help ginsenosides promote the development of stem cell regenerative medicine and anti-aging drugs in nerves field.

Aging leads to a decline in the capacity of NSCs to enter the cell cycle efficiently (Audesse and Webb, 2020). Genes involved in cell cycle regulation play an essential role in the stability and activation of NSCs (Roccio et al., 2013). Ginsenoside Rg1 targets Akt/mTOR to downregulate the levels of cell cycle arrest-related proteins (p53, p16, p21, and Rb) in NSCs, promoting NSC proliferation and alleviating D-galactose-induced NSC aging (Chen et al., 2018). 20(S)-PPD induces autophagy and cell cycle arrest, and promote NSC from a proliferative state to a differentiated state and helps to repair neurons in age-related neurodegenerative AD (Chen et al., 2020). This suggests that further understanding of the molecular mechanism by which ginsenosides alleviate NSC aging requires a deeper study of upstream signaling pathways and regulators that affect the cell cycle to maintain the continued health of NSCs.

3.2.3 Effect on transdifferentiation of NSCs

NSCs can also differentiate from other stem cells with transdifferentiation capability, such as MSCs (Feng et al., 2014). It was previously demonstrated that ginsenoside Rg1 promotes the differentiation of transplanted bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) into neurons and glial cells (Bao et al., 2015). A recent report has shown that ginsenoside Rg1 regulates miRNA-124 expression in vitro to promote neural differentiation of mouse adipose stem cells (ADSCs) (Dong et al., 2017). Ginsenoside Rg1 promotes the neural phenotype differentiation of human ADSCs by activating the expression of NSC niche components including growth associated protein-43 (GAP-43), neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM), and synapsin-1 (SYN-1) (Xu et al., 2014). In addition, ginsenoside Rg1 promotes the differentiation of human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells (hUCMSC) into NSCs by downregulating genes involved in the Wnt/β-catenin and Notch signaling pathways, including GSK3β, β-catenin, Notch1, and Hes1 (Xiao et al., 2022). However, the transdifferentiation capability of NSCs is still doubted since the possible contamination by other tissue stem cells or embryonic stem cells in those studies.

3.3 Hematopoietic stem cells

HSCs have self-renewal potential and can differentiate into various hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPC) and produce specific blood cell types to maintain the stability of the entire hematopoietic system (Zhao and Li, 2015).

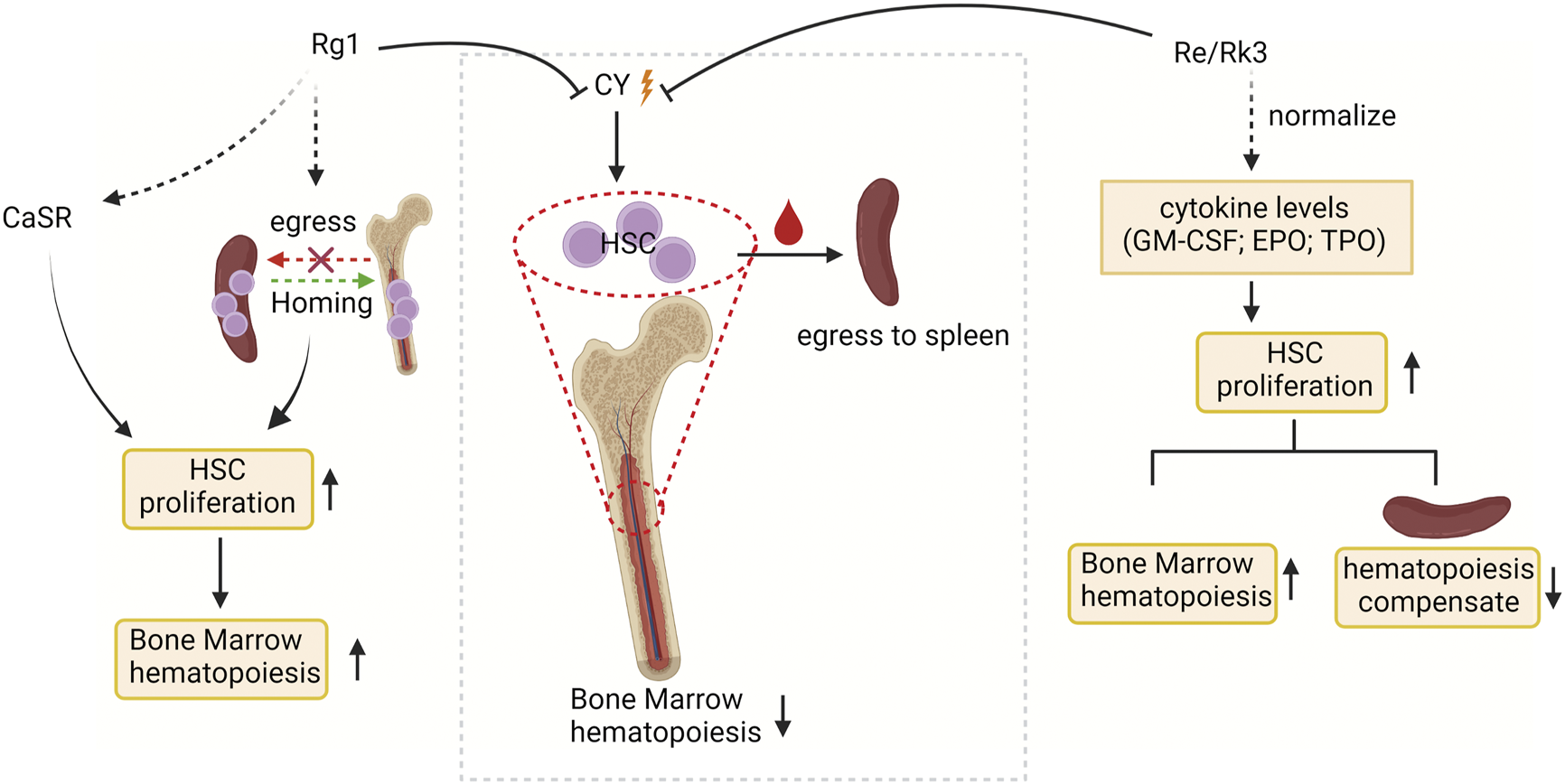

3.3.1 Effect on proliferation of HSCs

External supplementation of HSCs is widely used to reconstruct damaged bone marrow (Ju et al., 2020). Bone marrow suppression and extramedullary hematopoiesis are often caused by the side effects of chemotherapy drugs (such as cyclophosphamide; CY) used by cancer patients, making stimulation of hematopoiesis, a critical issue in the context of cancer therapy in clinical practice (Wang et al., 2009; Ahlmann and Hempel, 2016; Hou et al., 2017). Ginsenosides relieve CY-induced myelosuppression by activating HSC proliferation (Figure 2). HSCs expansion in the bone marrow is strictly regulated by the HSCs niche (Pinho and Frenette, 2019). Multiple signal molecules are involved in HSCs-niche interactions, such as Ca2+ sensitive receptor (CaSR), and three cytokines, including granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulatory factors (GM-CSF), erythropoietin (EPO) and thrombopoietin (TPO), are essential for HSC proliferation (Szade et al., 2018). CaSR has been demonstrated that regulates calcium ion levels to maintain calcium homeostasis and plays critical regulatory roles in the retention and colonization of HSCs after transplantation (Cho et al., 2020; Uslu et al., 2020). Such the CaSR can be activated by ginsenoside Rg1 to relieve CY-induced inhibition of the proliferation of Lin-Sca-1+c-Kit + HSCs and CD3+ in mouse bone marrow and peripheral blood, restoring bone marrow function (Xu et al., 2012). Another study found that ginsenosides Re and Rk3 compensated hematopoietic function by increasing the secretion of cytokines (GM-CSF, TPO, EPO) to restore HSC proliferation. (Han et al., 2019). In addition, the compensatory hematopoiesis of the spleen is the key means to restore the normal hematopoietic function of the bone marrow. Ginsenoside Rg1 treatment of CY-induced myelosuppressive mice can improve bone marrow hematopoietic activity by improving the spleen niche and promoting the proliferation and homing of c-Kit + HSCs in the spleen (Liu HH. et al., 2015). As mentioned above, the niche may be an important target for ginsenosides to regulate HSC proliferation and assist recovery from myelosuppression. It is necessary to focus on whether the effects of ginsenosides on other cellular components in the stem cell niche feed back to the stem cells so that we can more fully understand the regulatory mechanisms of ginsenosides on stem cell fate specification.

FIGURE 2

The targets of ginsenosides promoting HSC proliferation and stimulating bone marrow hematopoiesis at the molecular level. CY, cyclophosphamide; CaSR, Ca2+ sensitive receptor; GM-CSF, granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulatory factors; EPO, erythropoietin; and TPO, thrombopoietin.

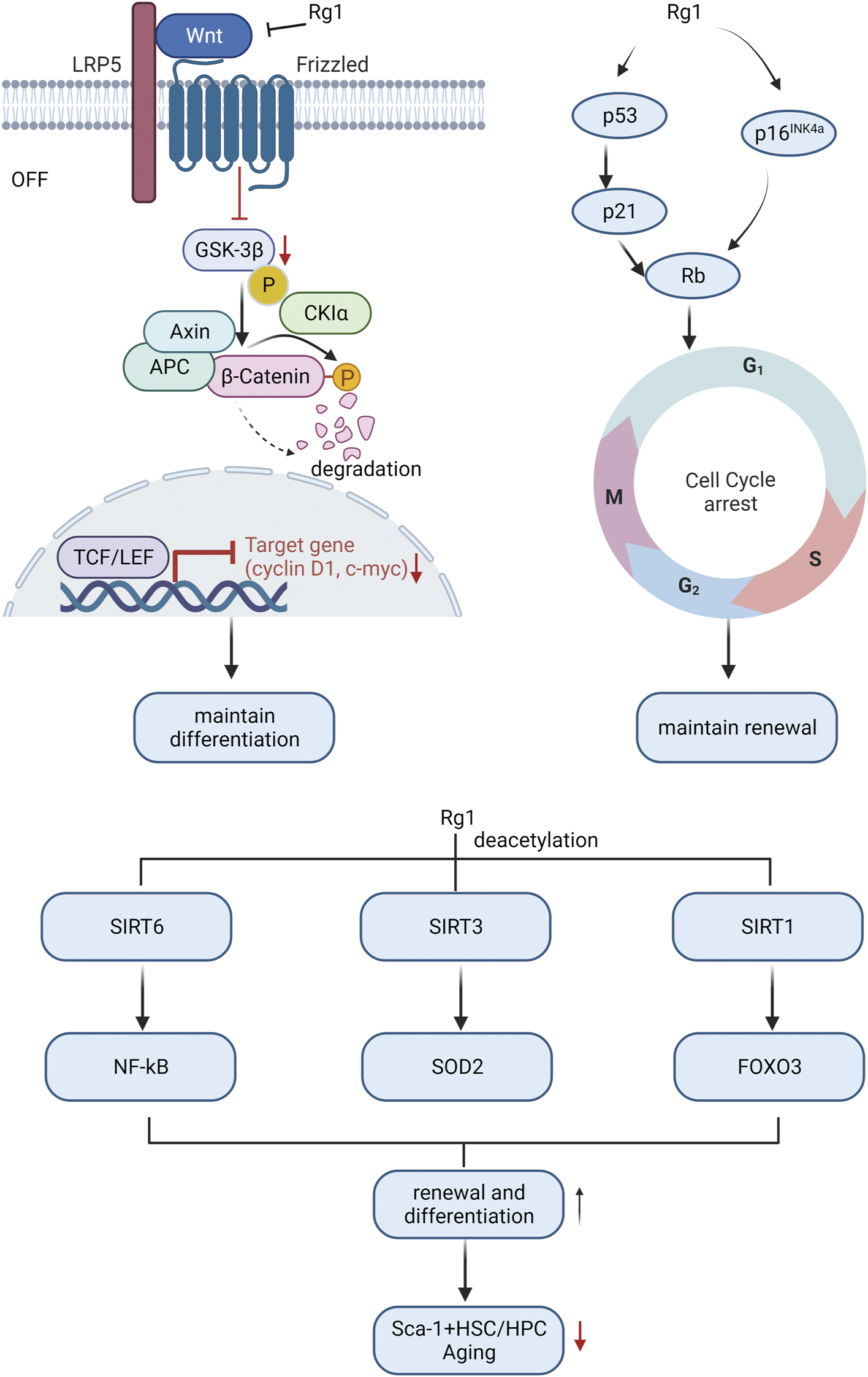

3.3.2 Effect on differentiation and self-renewal of HSCs in the aging process

Research indicates that HSC aging is linked to body aging since it impairs the self-renewal and differentiation ability of stem cells, resulting in decreased hematopoietic and immune function, and ultimately leading to tissue and organ structure and function deterioration throughout the body (Han et al., 2019). Therefore, it is meaningful to study the mechanism of HSC aging to elucidate the aging mechanism of the body. Ginsenoside Rg1 resisted HSC senescence to restore self-renewal and multi-differentiation abilities (Figure 3). Excessive ROS generated by oxidative stress may be the main mediator of stem cell senescence induced by excessive activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway (Zhang DY. et al., 2013). The proto-oncogene c-myc and cyclin D1 are target genes downstream of the Wnt pathway, and their overexpression may cause DNA damage and induce oxidative stress senescence (Shang et al., 2023). Ginsenoside Rg1 acts as a Wnt/β-catenin signal transduction inhibitor to inhibit Wnt target genes (such as cyclin D1 and c-myc) regulated by TCF/LEF transcription factors, thereby delaying LiCl and D-galactose-induced Sca-1 + HSC/HPC oxidative damage cascades restore their differentiation characteristics (Li et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2022a).

FIGURE 3

Molecular mechanism of ginsenosides affecting HSC differentiation and self-renewal ability to resist HSC aging.

Cell cycle arrest is another main cause of HSC aging (Mohrin et al., 2015). Ginsenoside Rg1 antagonizes lead acetate, t-BHP, radiation, and d-galactose by repressing some key genes in the cell cycle regulator signaling pathway (p53-p21-Rb, p16INK4a-Rb, and p53-p21Cip/Waf1)-induced HSC senescence, improving HSC self-renewal capacity (Chen et al., 2014; Yue et al., 2014; Li et al., 2016; Cai et al., 2018).

Sirtuins alter protein activity and stability through lysine deacetylation is another important factor in regulating the cellular aging process (Lasigliè, 2021). The sirtuins SIRT1, SIRT3, and SIRT6 are key regulators of HSC lifespan (Wang et al., 2016; Fang et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2022b). Activation of SIRT6 by ginsenoside Rg1 inhibits NF-κB through H3K9 deacetylation, slows down t-BHP-induced Sca-1+HSC/HPC senescence, and enhances self-renewal and multi-differentiation abilities (Tang et al., 2015). Ginsenoside Rg1 activates SIRT3 to trigger deacetylation to enhance SOD2 activity and accelerate ROS clearance, slow down D-gal-induced Sca-1+HSC/HPC senescence, and promote HSC self-renewal and multi-differentiation ability (Zhou Y. et al., 2020). Ginsenoside Rg1-mediated SIRT1-FOXO3 promotes Sca-1+HSC/HPC multi-differentiation and self-renewal (Tang et al., 2020b), and inhibits gamma-ray-induced Sca-1+HSC/HPC senescence, which is dependent on deactivation of SIRT1/SIRT3 Acetylation (Tang et al., 2020a).

Overall, the mechanisms of ginsenoside in reducing HSCs aging mainly involve Wnt/β-catenin, cell cycle, and sirtuins-mediated senescence signaling pathway.

3.4 Cancer stem cells

CSCs exhibit qualities of stem cells and cancer cells, contributing to tumor growth, metastasis formation, and recurrence (Tanabe, 2022). CSCs initiate and maintain cancer initiation and progression based on stemness characteristics, namely, self-renewal and abnormal proliferation/differentiation (Eun et al., 2017).

3.4.1 Effect on proliferation and self-renewal of CSCs

Wnt/β-catenin signaling is the main signaling pathway that promotes cancer cell stemness (Katoh and Katoh, 2022). Ginsenoside Rh2 inhibits cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) proliferation by reducing the number of Wnt target gene Lgr5+ cells by inhibiting β-catenin signaling (Liu S. et al., 2015). Ginsenoside Rg3 and Rh2 reduced the self-renewal capacity of glioblastoma stem cells (GSC) by inhibiting the expression of transcription factor LCF1 and downstream Wnt target genes (c-myc, CCND1) of Wnt/β-catenin signaling (Ham et al., 2019). Notably, the anti-CSC capacity of Rh2 is better than that of ginsenoside Rg3, which supports that ginsenoside metabolites with fewer sugar groups have stronger anticancer activity.

Accumulating evidence indicates that EMT activation is abnormally high in CSCs, and there is a strong correlation between CSC stemness and EMT regulation (Tanabe et al., 2020). Recently, many studies have reported that ginsenosides exert anticancer effects by inhibiting EMT (Dai et al., 2019; Cai et al., 2021; Li et al., 2021). Ginsenoside Rg3R has been shown to reduce self-renewal in colorectal cancer cells (CRC) by targeting the SNAIL signaling pathway and modulating EMT features (Phi et al., 2019b). Ginsenoside Rk1/Rg5 inhibited EMT and self-renewal ability of A549 cells and reduced A549 stemness, which was dependent on the inhibition of TGF-b1-mediated downstream signaling pathways, including Smad2/3, NF-κB, ERK1/2, p38 MAPK and JNK (Kim et al., 2021). In addition, the hypoxic niche is the main place to maintain the stemness characteristics of CSCs. Nur77 is highly expressed in the hypoxic niche in a mouse model of colon cancer. Ginsenoside CK, as a Nur77 ligand target, prevents the Nur77-Akt activation circuit and inhibits CSCs proliferation and stemness (Zhang M. et al., 2022).

In summary, the regulation of ginsenosides on CSC stemness (especially self-renewal ability) involves a variety of signaling pathways. The key to solving the problem of targeted therapy is to further study whether these pathways exist independently or interact, which will be the key of tumor therapy in the context of ginsenoside.

3.4.2 Effect on proliferation and self-renewal of CSCs in the aging process

One subtype of CSC, leukemia stem cells (LSCs), is a crucial origin of leukemia due to its high proliferation and abnormal growth (Chavez-Gonzalez et al., 2017). Inducing LSCs aging can reduce the number of LSCs, thus reducing the incidence of leukemia (Liu W. et al., 2022). Ginsenosides mainly induce the aging of LSCs by the following signals, slowing down or inhibiting the development of leukemia.

One of the mechanisms by which ginsenosides induce senescence in LSCs is their inhibitory potential for proliferation and self-renewal, involving deacetylation mediated by SIRT1 (one of the sirtuins members). Ginsenoside Rg1 downregulates the expression of SIRT1/TSC2 in CD34+CD38-LSCs, significantly increases the level of senescence marker SA-β-Gal, and reduces the unit of mixed colony-forming (a marker of proliferation ability), and reduces cell renewal and proliferation ability to induce LSCs senescence (Tang et al., 2020a).

Telomere is another pathway that ginsenosides participate in regulating the proliferation and self-renewal of LSCs to induce senescence. LSCs have relatively short telomeres, but they show higher levels of telomerase activity compared with normal cells. This enhanced telomerase activity may be an adaptive mechanism aimed at maintaining the continuous replication of LSCs and promoting leukemia development (Kuo and Bhatia, 2014). A recent study found that ginsenoside Rg1 inhibited CD34+CD38-LSCs proliferative activity, increased expression of telomere damage effector p16INK4a, and decreased human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT, catalytic subunit of telomerase) to induce its replicative senescence for the treatment of leukemia (Tang et al., 2021). The above findings suggest that ginsenoside Rg1 inhibits the ability of LSCs to self-renewal and proliferation, and its targeted therapy based on the intervention of LSCs senescence is a valuable direction for healing leukemia in the future.

Noteworthy, we observed that the effects of ginsenosides on CSC and normal stem cell fate are asymmetric (inhibit CSC self-renewal, promote normal stem cell proliferation/differentiation), which may have multiple reasons. First, CSCs of various origins overexpress the glucose transporter GLUT1 (Maliekal et al., 2022). Due to their steroidal structure, ginsenosides have the property of recognizing GLUT carriers on tumor cell membranes (Chen et al., 2022). Ginsenoside Rh2 inhibits GLUT1-mediated aerobic glycolysis in tumor cells, and its role as a tumor energy blocker may be responsible for the inhibition of CSC self-renewal (Liu X Y et al., 2020). Second, ginsenoside Rb1 and its deglycosylated product compound K also decreased the expression of drug efflux pumps (ABCG2 and P-glycoprotein), inhibiting the resistance of CSCs to chemotherapeutic drugs (Deng et al., 2017). In addition, ginsenosides, as signal transduction regulators of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, participate in the regulation of stem cell fate specification, with opposite effects on CSCs and normal stem cells. The regulation of ginsenosides on Wnt/β-catenin is mainly through regulating the activity of the intermediate GSK-3β to mediate the signal transmission triggered by β-catenin degradation/nuclear translocation, including the inhibition/activation of downstream transcription factors (TCF/LEF) and Wnt target genes (CCND1, c-myc, Lgr5), thereby affecting the function and fate of stem cells (Sferrazza et al., 2020). We speculate that ginsenosides inhibit CSC and stimulate normal stem cell proliferation/differentiation may be due to the different functions of Wnt target genes in CSC and normal stem cells. However, further verification in vivo or clinical experiments is needed to support this point of view. In conclusion, ginsenosides show potential as anticancer drugs, but further research and clinical trials are currently needed to determine their efficacy and safety.

3.5 Other kinds of adult stem cells

Although the effects of ginsenosides on other types of adult stem cells are not well understood, existing findings suggest a potential multifunctional regulatory capacity. For example, Ginsenoside Rd can stimulate the proliferation of intestinal stem cells (marked by Bmi and Msi-1) in rat inflammatory bowel disease model and promote the differentiation into intestinal epithelial cells expressing CDX-2, thereby restoring intestinal function (Yang et al., 2020). Ginsenoside Rg1 promotes the odontogenic differentiation of human dental pulp stem cells (hDPSCs) by upregulating osteogenesis-promoting factors, including bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2) and fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2) (Wang et al., 2014). In addition, PPT induced the proliferation and differentiation of sperm stem cells and resisted busulfan-induced reproductive toxicity in male mice (Ji et al., 2007). These findings suggest that ginsenosides have a wide range of effects, contributing to tissue repair and regeneration, and holding potential for the treatment of various diseases. Strengthening the study of the molecular mechanism of ginsenosides on other types of adult stem cells will help its clinical application.

4 Conclusion

This review gives an overview of the fate specification effects of ginsenosides on adult stem cells from the perspective of physiology (including aging states) and pathology. However, currently most of studies we reviewed are based on in vitro model and we still lack knowledge of how ginsenosides affect stem cell proliferation and differentiation or relieve dysfunctions in those processes in vivo and whether ginsenosides have considerable value in clinical practice. To figure out such limitations and the great potential of ginsenosides in tissue repair, cell replacement and disease treatment, more research (especially in vivo studies in distinct species) should be done to unravel the underlying mechanism of ginsenosides in proliferation, differentiation and self-renewal of different stem cell types. Considering the continuous proceeding of research on ginsenosides and proliferation as well as differentiation processes in various stem cells, we believe the promise of ginsenosides in regenerative medicine and healthy aging will be attested soon.

Statements

Author contributions

Information collection and interpretation: YL, LJ, WS, CW, SY, JQ, XW, XB, and CJ; critically revising the manuscript: YL, DZ, SW, PZ, XB, and ML. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was funded by the Scientific and Technological Development Planning Foundation of Jilin Province (YDZJ202201ZYTS683), the Scientific and Technological Developing Scheme of Ji Lin Province (20210204188YY), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U19A2013).

Acknowledgments

Images were created using BioRender.com.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Aghaizu N. D. Jin H. Whiting P. J. (2020). Dysregulated Wnt signalling in the Alzheimer's brain. Brain Sci.10 (12), 902. 10.3390/brainsci10120902

2

Ahlmann M. Hempel G. (2016). The effect of cyclophosphamide on the immune system: Implications for clinical cancer therapy. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol.78 (4), 661–671. 10.1007/s00280-016-3152-1

3

Ali M. Y. Zaib S. Jannat S. Khan I. Rahman M. M. Park S. K. et al (2022). Inhibition of aldose reductase by ginsenoside derivatives via a specific structure activity relationship with kinetics mechanism and molecular docking study. Molecules27 (7), 2134. 10.3390/molecules27072134

4

Alle Q. Le Borgne E. Milhavet O. Lemaitre J. M. (2021). Reprogramming: Emerging strategies to rejuvenate aging cells and tissues. Int. J. Mol. Sci.22 (8), 3990. 10.3390/ijms22083990

5

Aquino-Martínez R. Artigas N. Gámez B. Rosa J. L. Ventura F. (2017). Extracellular calcium promotes bone formation from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells by amplifying the effects of BMP-2 on SMAD signalling. PLoS One12 (5), e0178158. 10.1371/journal.pone.0178158

6

Audesse A. J. Webb A. E. (2020). Mechanisms of enhanced quiescence in neural stem cell aging. Mech. Ageing Dev.191, 111323. 10.1016/j.mad.2020.111323

7

Bao C. Wang Y. Min H. Zhang M. Du X. Han R. et al (2015). Combination of ginsenoside Rg1 and bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in the treatment of cerebral ischemia reperfusion injury in rats. Cell Physiol. Biochem.37 (3), 901–910. 10.1159/000430217

8

Brassard J. A. Lutolf M. P. (2019). Engineering stem cell self-organization to build better organoids. Cell Stem Cell24 (6), 860–876. 10.1016/j.stem.2019.05.005

9

Cai N. Yang Q. Che D. B. Jin X. (2021). 20(S)-Ginsenoside Rg3 regulates the Hedgehog signaling pathway to inhibit proliferation and epithelial-mesenchymal transition of lung cancer cells. Pharmazie76 (9), 431–436. 10.1691/ph.2021.1573

10

Cai S. Z. Zhou Y. Liu J. Li C. P. Jia D. Y. Zhang M. S. et al (2018). Alleviation of ginsenoside Rg1 on hematopoietic homeostasis defects caused by lead-acetate. Biomed. Pharmacother.97, 1204–1211. 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.10.148

11

Chacón-Martínez C. A. Koester J. Wickström S. A. (2018). Signaling in the stem cell niche: Regulating cell fate, function and plasticity. Development145 (15), dev165399. 10.1242/dev.165399

12

Chandel N. S. Jasper H. Ho T. T. Passegué E. (2016). Metabolic regulation of stem cell function in tissue homeostasis and organismal ageing. Nat. Cell Biol.18 (8), 823–832. 10.1038/ncb3385

13

Chavez-Gonzalez A. Bakhshinejad B. Pakravan K. Guzman M. L. Babashah S. (2017). Novel strategies for targeting leukemia stem cells: Sounding the death knell for blood cancer. Cell Oncol. (Dordr)40 (1), 1–20. 10.1007/s13402-016-0297-1

14

Che L. Zhu C. Huang L. Xu H. Ma X. Luo X. et al (2023). Ginsenoside Rg2 promotes the proliferation and stemness maintenance of porcine mesenchymal stem cells through autophagy induction. Foods12 (5), 1075. 10.3390/foods12051075

15

Chen C. Mu X. Y. Zhou Y. Shun K. Geng S. Liu J. et al (2014). Ginsenoside Rg1 enhances the resistance of hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells to radiation-induced aging in mice. Acta Pharmacol. Sin.35 (1), 143–150. 10.1038/aps.2013.136

16

Chen C. Xia J. Ren H. Wang A. Zhu Y. Zhang R. et al (2022). Effect of the structure of ginsenosides on the in vivo fate of their liposomes. Asian J. Pharm. Sci.17 (2), 219–229. 10.1016/j.ajps.2021.12.002

17

Chen F. Liu Y. Wong N. K. Xiao J. So K. F. (2017). Oxidative stress in stem cell aging. Cell Transpl.26 (9), 1483–1495. 10.1177/0963689717735407

18

Chen L. Yao H. Chen X. Wang Z. Xiang Y. Xia J. et al (2018). Ginsenoside Rg1 decreases oxidative stress and down-regulates akt/mTOR signalling to attenuate cognitive impairment in mice and senescence of neural stem cells induced by D-galactose. Neurochem. Res.43 (2), 430–440. 10.1007/s11064-017-2438-y

19

Chen S. He J. Qin X. Luo T. Pandey A. Li J. et al (2020). Ginsenoside metabolite 20(S)-protopanaxadiol promotes neural stem cell transition from a state of proliferation to differentiation by inducing autophagy and cell cycle arrest. Mol. Med. Rep.22 (1), 353–361. 10.3892/mmr.2020.11081

20

Cho H. Lee J. Jang S. Lee J. Oh T. I. Son Y. et al (2020). CaSR-mediated hBMSCs activity modulation: Additional coupling mechanism in bone remodeling compartment. Int. J. Mol. Sci.22 (1), 325. 10.3390/ijms22010325

21

Dai G. Sun B. Gong T. Pan Z. Meng Q. Ju W. (2019). Ginsenoside Rb2 inhibits epithelial-mesenchymal transition of colorectal cancer cells by suppressing TGF-β/Smad signaling. Phytomedicine56, 126–135. 10.1016/j.phymed.2018.10.025

22

De D. Karmakar P. Bhattacharya D. (2021). Stem cell aging and regenerative medicine. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol.1326, 11–37. 10.1007/5584_2020_577

23

De Oliveira Zanuso B. De Oliveira Dos Santos A. R. Miola V. F. B. Guissoni Campos L. M. Spilla C. S. G. Barbalho S. M. (2022). Panax ginseng and aging related disorders: A systematic review. Exp. Gerontol.161, 111731. 10.1016/j.exger.2022.111731

24

Deng S. Wong C. K. C. Lai H. C. Wong A. S. T. (2017). Ginsenoside-Rb1 targets chemotherapy-resistant ovarian cancer stem cells via simultaneous inhibition of Wnt/β-catenin signaling and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Oncotarget8 (16), 25897–25914. 10.18632/oncotarget.13071

25

Ding L. Gu S. Zhou B. Wang M. Zhang Y. Wu S. et al (2022). Ginsenoside compound K enhances fracture healing via promoting osteogenesis and angiogenesis. Front. Pharmacol.13, 855393. 10.3389/fphar.2022.855393

26

Dong J. Zhu G. Wang T. C. Shi F. S. (2017). Ginsenoside Rg1 promotes neural differentiation of mouse adipose-derived stem cells via the miRNA-124 signaling pathway. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B18 (5), 445–448. 10.1631/jzus.B1600355

27

Dong W. Chen W. Zou H. Shen Z. Yu D. Chen W. et al (2022). Ginsenoside Rb1 prevents oxidative stress-induced apoptosis and mitochondrial dysfunction in muscle stem cells via NF-κB pathway. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev.2022, 9159101. 10.1155/2022/9159101

28

Eun K. Ham S. W. Kim H. (2017). Cancer stem cell heterogeneity: Origin and new perspectives on CSC targeting. BMB Rep.50 (3), 117–125. 10.5483/bmbrep.2017.50.3.222

29

Fang Y. An N. Zhu L. Gu Y. Qian J. Jiang G. et al (2020). Autophagy-Sirt3 axis decelerates hematopoietic aging. Aging Cell19 (10), e13232. 10.1111/acel.13232

30

Feng N. Han Q. Li J. Wang S. Li H. Yao X. et al (2014). Generation of highly purified neural stem cells from human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells by Sox1 activation. Stem Cells Dev.23 (5), 515–529. 10.1089/scd.2013.0263

31

Gao B. Huang Q. Jie Q. Zhang H. Y. Wang L. Guo Y. S. et al (2015). Ginsenoside-Rb2 inhibits dexamethasone-induced apoptosis through promotion of GPR120 induction in bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells Dev.24 (6), 781–790. 10.1089/scd.2014.0367

32

Gao J. Wan F. Tian M. Li Y. Li Y. Li Q. et al (2017). Effects of ginsenoside-Rg1 on the proliferation and glial-like directed differentiation of embryonic rat cortical neural stem cells in vitro. Mol. Med. Rep.16 (6), 8875–8881. 10.3892/mmr.2017.7737

33

Giri T. K. Alexander A. Agrawal M. Saraf S. Saraf S. Ajazuddin (2019). Current status of stem cell therapies in tissue repair and regeneration. Curr. Stem Cell Res. Ther.14 (2), 117–126. 10.2174/1574888x13666180502103831

34

Gu Y. Zhou J. Wang Q. Fan W. Yin G. (2016). Ginsenoside Rg1 promotes osteogenic differentiation of rBMSCs and healing of rat tibial fractures through regulation of GR-dependent BMP-2/SMAD signaling. Sci. Rep.6, 25282. 10.1038/srep25282

35

Guo Y. Tian T. Yang S. Cai Y. (2023). Ginsenoside Rg1/ADSCs supplemented with hyaluronic acid as the matrix improves rabbit temporomandibular joint osteoarthrosis. Biotechnol. Genet. Eng. Rev.9, 1–22. 10.1080/02648725.2023.2183575

36

Gurusamy N. Alsayari A. Rajasingh S. Rajasingh J. (2018). Adult stem cells for regenerative therapy. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci.160, 1–22. 10.1016/bs.pmbts.2018.07.009

37

Ham S. W. Kim J. K. Jeon H. Y. Kim E. J. Jin X. Eun K. et al (2019). Korean Red ginseng extract inhibits glioblastoma propagation by blocking the Wnt signaling pathway. J. Ethnopharmacol.236, 393–400. 10.1016/j.jep.2019.03.031

38

Han J. Xia J. Zhang L. Cai E. Zhao Y. Fei X. et al (2019). Studies of the effects and mechanisms of ginsenoside Re and Rk(3) on myelosuppression induced by cyclophosphamide. J. Ginseng Res.43 (4), 618–624. 10.1016/j.jgr.2018.07.009

39

He F. Yao G. (2021). Ginsenoside Rg1 as a potential regulator of hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells. Stem Cells Int.2021, 4633270. 10.1155/2021/4633270

40

He F. Yu C. Liu T. Jia H. (2019). Ginsenoside Rg1 as an effective regulator of mesenchymal stem cells. Front. Pharmacol.10, 1565. 10.3389/fphar.2019.01565

41

He M. Wang N. Zheng W. Cai X. Qi D. Zhang Y. et al (2021). Ameliorative effects of ginsenosides on myelosuppression induced by chemotherapy or radiotherapy. J. Ethnopharmacol.268, 113581. 10.1016/j.jep.2020.113581

42

Hicks M. R. Pyle A. D. (2023). The emergence of the stem cell niche. Trends Cell Biol.33 (2), 112–123. 10.1016/j.tcb.2022.07.003

43

Hong T. Kim M. Y. Da Ly D. Park S. J. Eom Y. W. Park K. S. et al (2020). Ca(2+)-activated mitochondrial biogenesis and functions improve stem cell fate in Rg3-treated human mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cell Res. Ther.11 (1), 467. 10.1186/s13287-020-01974-3

44

Hou B. Liu R. Qin Z. Luo D. Wang Q. Huang S. (2017). Oral Chinese herbal medicine as an adjuvant treatment for chemotherapy, or radiotherapy, induced myelosuppression: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med.2017, 3432750. 10.1155/2017/3432750

45

Hou C. W. Lee S. D. Kao C. L. Cheng I. S. Lin Y. N. Chuang S. J. et al (2015). Improved inflammatory balance of human skeletal muscle during exercise after supplementations of the ginseng-based steroid Rg1. PLoS One10 (1), e0116387. 10.1371/journal.pone.0116387

46

Hou M. Wang R. Zhao S. Wang Z. (2021). Ginsenosides in Panax genus and their biosynthesis. Acta Pharm. Sin. B11 (7), 1813–1834. 10.1016/j.apsb.2020.12.017

47

Hu J. Gu Y. Fan W. (2016). Rg1 protects rat bone marrow stem cells against hydrogen peroxide-induced cell apoptosis through the PI3K/Akt pathway. Mol. Med. Rep.14 (1), 406–412. 10.3892/mmr.2016.5238

48

Hu W. Jing P. Wang L. Zhang Y. Yong J. Wang Y. (2015). The positive effects of Ginsenoside Rg1 upon the hematopoietic microenvironment in a D-Galactose-induced aged rat model. BMC Complement. Altern. Med.15, 119. 10.1186/s12906-015-0642-3

49

Huang X. Li N. Pu Y. Zhang T. Wang B. (2019). Neuroprotective effects of ginseng phytochemicals: Recent perspectives. Molecules24 (16), 2939. 10.3390/molecules24162939

50

Ichim M. C. De Boer H. J. (2020). A review of authenticity and authentication of commercial ginseng herbal medicines and food supplements. Front. Pharmacol.11, 612071. 10.3389/fphar.2020.612071

51

Ji M. Minami N. Yamada M. Imai H. (2007). Effect of protopanaxatriol saponin on spermatogenic stem cell survival in busulfan-treated male mice. Reprod. Med. Biol.6 (2), 99–108. 10.1111/j.1447-0578.2007.00172.x

52

Jin J. Shahi S. Kang H. K. Van Veen H. W. Fan T. P. (2006). Metabolites of ginsenosides as novel BCRP inhibitors. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.345 (4), 1308–1314. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.04.152

53

Ju W. Lu W. Ding L. Bao Y. Hong F. Chen Y. et al (2020). PEDF promotes the repair of bone marrow endothelial cell injury and accelerates hematopoietic reconstruction after bone marrow transplantation. J. Biomed. Sci.27 (1), 91. 10.1186/s12929-020-00685-4

54

Katoh M. Katoh M. (2022). WNT signaling and cancer stemness. Essays Biochem.66 (4), 319–331. 10.1042/ebc20220016

55

Kim H. Choi P. Kim T. Kim Y. Song B. G. Park Y. T. et al (2021). Ginsenosides Rk1 and Rg5 inhibit transforming growth factor-β1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition and suppress migration, invasion, anoikis resistance, and development of stem-like features in lung cancer. J. Ginseng Res.45 (1), 134–148. 10.1016/j.jgr.2020.02.005

56

Kumar D. Baligar P. Srivastav R. Narad P. Raj S. Tandon C. et al (2021). Stem cell based preclinical drug development and toxicity prediction. Curr. Pharm. Des.27 (19), 2237–2251. 10.2174/1381612826666201019104712

57

Kuo Y. H. Bhatia R. (2014). Pushing the limits: Defeating leukemia stem cells by depleting telomerase. Cell Stem Cell15 (6), 673–675. 10.1016/j.stem.2014.11.014

58

Lasigliè D. (2021). Sirtuins and the prevention of immunosenescence. Vitam. Horm.115, 221–264. 10.1016/bs.vh.2020.12.011

59

Lee I. S. Kang K. S. Kim S. Y. (2019). Panax ginseng pharmacopuncture: Current status of the research and future challenges. Biomolecules10 (1), 33. 10.3390/biom10010033

60

Lee T. X. Y. Wu J. Jean W. H. Condello G. Alkhatib A. Hsieh C. C. et al (2021). Reduced stem cell aging in exercised human skeletal muscle is enhanced by ginsenoside Rg1. Aging (Albany NY)13 (12), 16567–16576. 10.18632/aging.203176

61

Li J. Cai D. Yao X. Zhang Y. Chen L. Jing P. et al (2016). Protective effect of ginsenoside Rg1 on hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells through attenuating oxidative stress and the wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in a mouse model of d-Galactose-induced aging. Int. J. Mol. Sci.17 (6), 849. 10.3390/ijms17060849

62

Li N. Wang D. Ge G. Wang X. Liu Y. Yang L. (2014). Ginsenoside metabolites inhibit P-glycoprotein in vitro and in situ using three absorption models. Planta Med.80 (4), 290–296. 10.1055/s-0033-1360334

63

Li X. Liu W. Geng C. Li T. Li Y. Guo Y. et al (2021). Ginsenoside Rg3 suppresses epithelial-mesenchymal transition via downregulating notch-hes1 signaling in colon cancer cells. Am. J. Chin. Med.49 (1), 217–235. 10.1142/s0192415x21500129

64

Li Y. B. Wang Y. Tang J. P. Chen D. Wang S. L. (2015). Neuroprotective effects of ginsenoside Rg1-induced neural stem cell transplantation on hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Neural Regen. Res.10 (5), 753–759. 10.4103/1673-5374.156971

65

Li Y. Revalde J. L. Reid G. Paxton J. W. (2010). Interactions of dietary phytochemicals with ABC transporters: Possible implications for drug disposition and multidrug resistance in cancer. Drug Metab. Rev.42 (4), 590–611. 10.3109/03602531003758690

66

Lin K. L. Zhang J. Chung H. L. Wu X. Y. Liu B. Zhao B. X. et al (2022). Total ginsenoside extract from panax ginseng enhances neural stem cell proliferation and neuronal differentiation by inactivating GSK-3β. Chin. J. Integr. Med.28 (3), 229–235. 10.1007/s11655-021-3508-1

67

Lin K. Liu B. Lim S. L. Fu X. Sze S. C. Yung K. K. et al (2020). 20(S)-protopanaxadiol promotes the migration, proliferation, and differentiation of neural stem cells by targeting GSK-3β in the Wnt/GSK-3β/β-catenin pathway. J. Ginseng Res.44 (3), 475–482. 10.1016/j.jgr.2019.03.001

68

Lin T. Islam O. Heese K. (2006). ABC transporters, neural stem cells and neurogenesis--a different perspective. Cell Res.16 (11), 857–871. 10.1038/sj.cr.7310107

69

Liu H. H. Chen F. P. Liu R. K. Lin C. L. Chang K. T. (2015a). Ginsenoside Rg1 improves bone marrow haematopoietic activity via extramedullary haematopoiesis of the spleen. J. Cell Mol. Med.19 (11), 2575–2586. 10.1111/jcmm.12643

70

Liu S. Chen M. Li P. Wu Y. Chang C. Qiu Y. et al (2015b). Ginsenoside rh2 inhibits cancer stem-like cells in skin squamous cell carcinoma. Cell Physiol. Biochem.36 (2), 499–508. 10.1159/000430115

71

Liu W. Zhu X. Tang L. Shen N. Cheng F. Zou P. et al (2022a). ACSL1 promotes imatinib-induced chronic myeloid leukemia cell senescence by regulating SIRT1/p53/p21 pathway. Sci. Rep.12 (1), 17990. 10.1038/s41598-022-21009-6

72

Liu X. Y. Yang L. P. Zhao L. (2020). Stem cell therapy for Alzheimer's disease. World J. Stem Cells12 (8), 787–802. 10.4252/wjsc.v12.i8.787

73

Liu Y. Liu N. Li X. Luo Z. Zhang J. (2022b). Ginsenoside Rb1 modulates the migration of bone-derived mesenchymal stem cells through the SDF-1/CXCR4 Axis and PI3K/Akt pathway. Dis. Markers2022, 5196682. 10.1155/2022/5196682

74

Liu Y. Wang J. Qiao J. Liu S. Wang S. Zhao D. et al (2020). Ginsenoside Rh2 inhibits HeLa cell energy metabolism and induces apoptosis by upregulating voltage-dependent anion channel 1. Int. J. Mol. Med.46 (5), 1695–1706. 10.3892/ijmm.2020.4725

75

Liu Y. Zhang J. W. Li W. Ma H. Sun J. Deng M. C. et al (2006). Ginsenoside metabolites, rather than naturally occurring ginsenosides, lead to inhibition of human cytochrome P450 enzymes. Toxicol. Sci.91 (2), 356–364. 10.1093/toxsci/kfj164

76

Maliekal T. T. Dharmapal D. Sengupta S. (2022). Tubulin isotypes: Emerging roles in defining cancer stem cell niche. Front. Immunol.13, 876278. 10.3389/fimmu.2022.876278

77

Michler R. E. (2018). The current status of stem cell therapy in ischemic heart disease. J. Card. Surg.33 (9), 520–531. 10.1111/jocs.13789

78

Mohrin M. Shin J. Liu Y. Brown K. Luo H. Xi Y. et al (2015). Stem cell aging. A mitochondrial UPR-mediated metabolic checkpoint regulates hematopoietic stem cell aging. Science347 (6228), 1374–1377. 10.1126/science.aaa2361

79

Najafi M. Mortezaee K. Majidpoor J. (2019). Cancer stem cell (CSC) resistance drivers. Life Sci.234, 116781. 10.1016/j.lfs.2019.116781

80

Oh J. Yoon H. J. Jang J. H. Kim D. H. Surh Y. J. (2019). The standardized Korean Red Ginseng extract and its ingredient ginsenoside Rg3 inhibit manifestation of breast cancer stem cell-like properties through modulation of self-renewal signaling. J. Ginseng Res.43 (3), 421–430. 10.1016/j.jgr.2018.05.004

81

Pan W. Xue B. Yang C. Miao L. Zhou L. Chen Q. et al (2018). Biopharmaceutical characters and bioavailability improving strategies of ginsenosides. Fitoterapia129, 272–282. 10.1016/j.fitote.2018.06.001

82

Phi L. T. H. Sari I. N. Wijaya Y. T. Kim K. S. Park K. Cho A. E. et al (2019a). Ginsenoside Rd inhibits the metastasis of colorectal cancer via epidermal growth factor receptor signaling Axis. IUBMB Life71 (5), 601–610. 10.1002/iub.1984

83

Phi L. T. H. Wijaya Y. T. Sari I. N. Kim K. S. Yang Y. G. Lee M. W. et al (2019b). 20(R)-Ginsenoside Rg3 influences cancer stem cell properties and the epithelial-mesenchymal transition in colorectal cancer via the SNAIL signaling Axis. Onco Targets Ther.12, 10885–10895. 10.2147/OTT.S219063

84

Pinho S. Frenette P. S. (2019). Haematopoietic stem cell activity and interactions with the niche. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol.20 (5), 303–320. 10.1038/s41580-019-0103-9

85

Piyasirananda W. Beekman A. Ganesan A. Bidula S. Stokes L. (2021). Insights into the structure-activity relationship of glycosides as positive allosteric modulators acting on P2X7 receptors. Mol. Pharmacol.99 (2), 163–174. 10.1124/molpharm.120.000129

86

Ratan Z. A. Haidere M. F. Hong Y. H. Park S. H. Lee J. O. Lee J. et al (2021). Pharmacological potential of ginseng and its major component ginsenosides. J. Ginseng Res.45 (2), 199–210. 10.1016/j.jgr.2020.02.004

87

Regalado-Santiago C. Juárez-Aguilar E. Olivares-Hernández J. D. Tamariz E. (2016). Mimicking neural stem cell niche by biocompatible substrates. Stem Cells Int.2016, 1513285. 10.1155/2016/1513285

88

Roccio M. Schmitter D. Knobloch M. Okawa Y. Sage D. Lutolf M. P. (2013). Predicting stem cell fate changes by differential cell cycle progression patterns. Development140 (2), 459–470. 10.1242/dev.086215

89

Rokot N. T. Kairupan T. S. Cheng K. C. Runtuwene J. Kapantow N. H. Amitani M. et al (2016). A role of ginseng and its constituents in the treatment of central nervous system disorders. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med.2016, 2614742. 10.1155/2016/2614742

90

Scott C. T. Reijo Pera R. A. (2008). The road to pluripotence: The research response to the embryonic stem cell debate. Hum. Mol. Genet.17 (R1), R3–R9. 10.1093/hmg/ddn074

91

Sferrazza G. Corti M. Brusotti G. Pierimarchi P. Temporini C. Serafino A. et al (2020). Nature-derived compounds modulating Wnt/β -catenin pathway: A preventive and therapeutic opportunity in neoplastic diseases. Acta Pharm. Sin. B10 (10), 1814–1834. 10.1016/j.apsb.2019.12.019

92

Shang D. Li Z. Tan X. Liu H. Tu Z. (2023). Inhibitory effects and molecular mechanisms of ginsenoside Rg1 on the senescence of hematopoietic stem cells. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol.37 (3), 509–517. 10.1111/fcp.12863

93

Shibue T. Weinberg R. A. (2017). EMT, CSCs, and drug resistance: The mechanistic link and clinical implications. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol.14 (10), 611–629. 10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.44

94

Sinenko S. A. Ponomartsev S. V. Tomilin A. N. (2021). Pluripotent stem cell-based gene therapy approach: Human de novo synthesized chromosomes. Cell Mol. Life Sci.78 (4), 1207–1220. 10.1007/s00018-020-03653-1

95

Sivandzade F. Cucullo L. (2021). Regenerative stem cell therapy for neurodegenerative diseases: An overview. Int. J. Mol. Sci.22 (4), 2153. 10.3390/ijms22042153

96

Sterneckert J. L. Reinhardt P. Schöler H. R. (2014). Investigating human disease using stem cell models. Nat. Rev. Genet.15 (9), 625–639. 10.1038/nrg3764

97

Szade K. Gulati G. S. Chan C. K. F. Kao K. S. Miyanishi M. Marjon K. D. et al (2018). Where hematopoietic stem cells live: The bone marrow niche. Antioxid. Redox Signal29 (2), 191–204. 10.1089/ars.2017.7419

98

Tanabe S. (2022). Microenvironment of cancer stem cells. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol.1393, 103–124. 10.1007/978-3-031-12974-2_5

99

Tanabe S. Quader S. Cabral H. Ono R. (2020). Interplay of EMT and CSC in cancer and the potential therapeutic strategies. Front. Pharmacol.11, 904. 10.3389/fphar.2020.00904

100

Tang Y. L. Wang X. B. Zhou Y. Wang Y. P. Ding J. C. (2021). Ginsenoside Rg1 induces senescence of leukemic stem cells by upregulating p16INK4a and downregulating hTERT expression. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med.30 (6), 599–605. 10.17219/acem/133485

101

Tang Y. L. Zhang C. G. Liu H. Zhou Y. Wang Y. P. Li Y. et al (2020a). Ginsenoside Rg1 inhibits cell proliferation and induces markers of cell senescence in CD34+CD38- leukemia stem cells derived from KG1α acute myeloid leukemia cells by activating the sirtuin 1 (SIRT1)/Tuberous sclerosis complex 2 (TSC2) signaling pathway. Med. Sci. Monit.26, e918207. 10.12659/MSM.918207

102

Tang Y. L. Zhou Y. Wang Y. P. He Y. H. Ding J. C. Li Y. et al (2020b). Ginsenoside Rg1 protects against Sca-1(+) HSC/HPC cell aging by regulating the SIRT1-FOXO3 and SIRT3-SOD2 signaling pathways in a gamma-ray irradiation-induced aging mice model. Exp. Ther. Med.20 (2), 1245–1252. 10.3892/etm.2020.8810

103

Tang Y. L. Zhou Y. Wang Y. P. Wang J. W. Ding J. C. (2015). SIRT6/NF-κB signaling axis in ginsenoside Rg1-delayed hematopoietic stem/progenitor cell senescence. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol.8 (5), 5591–5596.

104

Uslu M. Albayrak E. Kocabas F. (2020). Temporal modulation of calcium sensing in hematopoietic stem cells is crucial for proper stem cell expansion and engraftment. J. Cell Physiol.235 (12), 9644–9666. 10.1002/jcp.29777

105

Vieira M. S. Santos A. K. Vasconcellos R. Goulart V. a. M. Parreira R. C. Kihara A. H. et al (2018). Neural stem cell differentiation into mature neurons: Mechanisms of regulation and biotechnological applications. Biotechnol. Adv.36 (7), 1946–1970. 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2018.08.002

106

Wang C. L. Xiao F. Wang C. D. Zhu J. F. Shen C. Zuo B. et al (2017). Gremlin2 suppression increases the BMP-2-induced osteogenesis of human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells via the BMP-2/smad/runx2 signaling pathway. J. Cell Biochem.118 (2), 286–297. 10.1002/jcb.25635

107

Wang H. Diao D. Shi Z. Zhu X. Gao Y. Gao S. et al (2016). SIRT6 controls hematopoietic stem cell homeostasis through epigenetic regulation of Wnt signaling. Cell Stem Cell18 (4), 495–507. 10.1016/j.stem.2016.03.005

108

Wang P. Wei X. Zhang F. Yang K. Qu C. Luo H. et al (2014). Ginsenoside Rg1 of Panax ginseng stimulates the proliferation, odontogenic/osteogenic differentiation and gene expression profiles of human dental pulp stem cells. Phytomedicine21 (2), 177–183. 10.1016/j.phymed.2013.08.021

109

Wang R. Wang M. Zhou J. Wu D. Ye J. Sun G. et al (2020a). Saponins in Chinese herbal medicine exerts protection in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury: Possible mechanism and target analysis. Front. Pharmacol.11, 570867. 10.3389/fphar.2020.570867

110

Wang Y. Meng Q. Qiao H. Jiang H. Sun X. (2009). Role of the spleen in cyclophosphamide-induced hematosuppression and extramedullary hematopoiesis in mice. Arch. Med. Res.40 (4), 249–255. 10.1016/j.arcmed.2009.04.003

111

Wang Y. Z. Xu Q. Wu W. Liu Y. Jiang Y. Cai Q. Q. et al (2018). Brain transport profiles of ginsenoside Rb(1) by glucose transporter 1: In vitro and in vivo. Front. Pharmacol.9, 398. 10.3389/fphar.2018.00398

112

Wang Z. Jiang R. Wang L. Chen X. Xiang Y. Chen L. et al (2020b). Ginsenoside Rg1 improves differentiation by inhibiting senescence of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell via GSK-3β and β-catenin. Stem Cells Int.2020, 2365814. 10.1155/2020/2365814

113

Wang Z. Wang L. Jiang R. Li C. Chen X. Xiao H. et al (2021). Ginsenoside Rg1 prevents bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell senescence via NRF2 and PI3K/Akt signaling. Free Radic. Biol. Med.174, 182–194. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2021.08.007

114

Wang Z. Xia J. Li J. Chen L. Chen X. Zhang Y. et al (2022a). Rg1 protects hematopoietic stem cells from LiCl-induced oxidative stress via Wnt signaling pathway. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med.2022, 2875583. 10.1155/2022/2875583

115

Wang Z. Zhang C. Warden C. D. Liu Z. Yuan Y. C. Guo C. et al (2022b). Loss of SIRT1 inhibits hematopoietic stem cell aging and age-dependent mixed phenotype acute leukemia. Commun. Biol.5 (1), 396. 10.1038/s42003-022-03340-w

116

Weatherbee B. a. T. Cui T. Zernicka-Goetz M. (2021). Modeling human embryo development with embryonic and extra-embryonic stem cells. Dev. Biol.474, 91–99. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2020.12.010

117

White A. C. Lowry W. E. (2015). Refining the role for adult stem cells as cancer cells of origin. Trends Cell Biol.25 (1), 11–20. 10.1016/j.tcb.2014.08.008

118

Won H. J. Kim H. I. Park T. Kim H. Jo K. Jeon H. et al (2019). Non-clinical pharmacokinetic behavior of ginsenosides. J. Ginseng Res.43 (3), 354–360. 10.1016/j.jgr.2018.06.001

119

Wong A. S. Che C. M. Leung K. W. (2015). Recent advances in ginseng as cancer therapeutics: A functional and mechanistic overview. Nat. Prod. Rep.32 (2), 256–272. 10.1039/c4np00080c

120

Wu T. Chen Y. Liu W. Tong K. L. Suen C. W. Huang S. et al (2020). Ginsenoside Rb1/TGF-β1 loaded biodegradable silk fibroin-gelatin porous scaffolds for inflammation inhibition and cartilage regeneration. Mater Sci. Eng. C Mater Biol. Appl.111, 110757. 10.1016/j.msec.2020.110757

121

Wu Y. Liu Y. Xu Y. Zheng A. Du J. Cao L. et al (2022). Bioactive natural compounds as potential medications for osteogenic effects in a molecular docking approach. Front. Pharmacol.13, 955983. 10.3389/fphar.2022.955983

122

Xiang Y. Wang S. H. Wang L. Wang Z. L. Yao H. Chen L. B. et al (2019). Effects of ginsenoside Rg1 regulating wnt/β-catenin signaling on neural stem cells to delay brain senescence. Stem Cells Int.2019, 5010184. 10.1155/2019/5010184

123

Xiao L. Wang M. Zou K. Li Z. Luo J. (2022). Effects of ginsenoside Rg1 on proliferation and directed differentiation of human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells into neural stem cells. Neuroreport33 (10), 413–421. 10.1097/wnr.0000000000001795

124

Xie Q. Liu R. Jiang J. Peng J. Yang C. Zhang W. et al (2020). What is the impact of human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell transplantation on clinical treatment?Stem Cell Res. Ther.11 (1), 519. 10.1186/s13287-020-02011-z

125

Xie W. Zhou P. Sun Y. Meng X. Dai Z. Sun G. et al (2018). Protective effects and target network analysis of ginsenoside Rg1 in cerebral ischemia and reperfusion injury: A comprehensive overview of experimental studies. Cells7 (12), 270. 10.3390/cells7120270

126

Xu F. T. Li H. M. Yin Q. S. Cui S. E. Liu D. L. Nan H. et al (2014). Effect of ginsenoside Rg1 on proliferation and neural phenotype differentiation of human adipose-derived stem cells in vitro. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol.92 (6), 467–475. 10.1139/cjpp-2013-0377

127

Xu F. T. Li H. M. Zhao C. Y. Liang Z. J. Huang M. H. Li Q. et al (2015). Characterization of chondrogenic gene expression and cartilage phenotype differentiation in human breast adipose-derived stem cells promoted by ginsenoside Rg1 in vitro. Cell Physiol. Biochem.37 (5), 1890–1902. 10.1159/000438550

128

Xu F. T. Liang Z. J. Li H. M. Peng Q. L. Huang M. H. Li De Q. et al (2016). Ginsenoside Rg1 and platelet-rich fibrin enhance human breast adipose-derived stem cell function for soft tissue regeneration. Oncotarget7 (23), 35390–35403. 10.18632/oncotarget.9360

129

Xu F. T. Xu Y. L. Rong Y. X. Huang D. L. Lai Z. H. Liu X. H. et al (2022). Rg1 promotes the proliferation and adipogenic differentiation of human adipose-derived stem cells via FXR1/lnc-GAS5-AS1 pathway. Curr. Stem Cell Res. Ther.17 (8), 815–824. 10.2174/1574888x16666211129121414

130

Xu S. F. Yu L. M. Fan Z. H. Wu Q. Yuan Y. Wei Y. et al (2012). Improvement of ginsenoside Rg1 on hematopoietic function in cyclophosphamide-induced myelosuppression mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol.695 (1-3), 7–12. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.07.050

131

Xu X. Lu Q. Wu J. Li Y. Sun J. (2017). Impact of extended ginsenoside Rb1 on early chronic kidney disease: A randomized, placebo-controlled study. Inflammopharmacology25 (1), 33–40. 10.1007/s10787-016-0296-x

132

Yamashita T. Abe K. (2016). Recent progress in therapeutic strategies for ischemic stroke. Cell Transpl.25 (5), 893–898. 10.3727/096368916x690548

133

Yang J. E. Jia N. Wang D. He Y. Dong L. Yang A. G. (2020a). Ginsenoside Rb1 regulates neuronal injury and Keap1-Nrf2/ARE signaling pathway in cerebral infarction rats. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents34 (3), 1091–1095. 10.23812/20-143-l-7

134

Yang L. Zou H. Gao Y. Luo J. Xie X. Meng W. et al (2020b). Insights into gastrointestinal microbiota-generated ginsenoside metabolites and their bioactivities. Drug Metab. Rev.52 (1), 125–138. 10.1080/03602532.2020.1714645

135

Yang N. Liang G. Lin J. Zhang S. Lin Q. Ji X. et al (2020). Ginsenoside Rd therapy improves histological and functional recovery in a rat model of inflammatory bowel disease. Phytother. Res.34 (11), 3019–3028. 10.1002/ptr.6734

136

Yang Z. Zhao T. Liu H. Zhang L. (2016). Ginsenoside Rh2 inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma through beta-catenin and autophagy. Sci. Rep.6, 19383. 10.1038/srep19383

137

Yao W. Guan Y. (2022). Ginsenosides in cancer: A focus on the regulation of cell metabolism. Biomed. Pharmacother.156, 113756. 10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113756

138

Yin W. Wang J. Jiang L. James Kang Y. (2021). Cancer and stem cells. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood)246 (16), 1791–1801. 10.1177/15353702211005390

139

Yousof Ali M. Jannat S. Mizanur Rahman M. (2021). Ginsenoside derivatives inhibit advanced glycation end-product formation and glucose-fructose mediated protein glycation in vitro via a specific structure-activity relationship. Bioorg Chem.111, 104844. 10.1016/j.bioorg.2021.104844

140

Yue Z. Rong J. Ping W. Bing Y. Xin Y. Feng L. D. et al (2014). Gene expression of the p16(INK4a)-Rb and p19(Arf)-p53-p21(Cip/Waf1) signaling pathways in the regulation of hematopoietic stem cell aging by ginsenoside Rg1. Genet. Mol. Res.13 (4), 10086–10096. 10.4238/2014.December.4.3

141

Zakrzewski W. Dobrzyński M. Szymonowicz M. Rybak Z. (2019). Stem cells: Past, present, and future. Stem Cell Res. Ther.10 (1), 68. 10.1186/s13287-019-1165-5

142

Zeng D. Wang J. Kong P. Chang C. Li J. Li J. (2014). Ginsenoside Rg3 inhibits HIF-1α and VEGF expression in patient with acute leukemia via inhibiting the activation of PI3K/Akt and ERK1/2 pathways. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol.7 (5), 2172–2178.

143

Zhang D. Y. Pan Y. Zhang C. Yan B. X. Yu S. S. Wu D. L. et al (2013a). Wnt/β-catenin signaling induces the aging of mesenchymal stem cells through promoting the ROS production. Mol. Cell Biochem.374 (1-2), 13–20. 10.1007/s11010-012-1498-1

144

Zhang G. Xia F. Zhang Y. Zhang X. Cao Y. Wang L. et al (2016). Ginsenoside Rd is efficacious against acute ischemic stroke by suppressing microglial proteasome-mediated inflammation. Mol. Neurobiol.53 (4), 2529–2540. 10.1007/s12035-015-9261-8

145

Zhang H. Hua X. Zheng D. Wu H. Li C. Rao P. et al (2022a). De novo biosynthesis of oleanane-type ginsenosides in Saccharomyces cerevisiae using two types of glycosyltransferases from panax ginseng. J. Agric. Food Chem.70 (7), 2231–2240. 10.1021/acs.jafc.1c07526

146

Zhang M. Shi Z. Zhang S. Li X. To S. K. Y. Peng Y. et al (2022b). The ginsenoside compound K suppresses stem-cell-like properties and colorectal cancer metastasis by targeting hypoxia-driven nur77-akt feed-forward signaling. Cancers (Basel)15 (1), 24. 10.3390/cancers15010024

147

Zhang Y. Dong F. Zhang N. Cheng H. Pang Y. Wang X. et al (2013b). Suppression of cytochrome p450 reductase enhances long-term hematopoietic stem cell repopulation efficiency in mice. PLoS One8 (7), e69913. 10.1371/journal.pone.0069913

148

Zhao J. Lu S. Yu H. Duan S. Zhao J. (2018). Baicalin and ginsenoside Rb1 promote the proliferation and differentiation of neural stem cells in Alzheimer's disease model rats. Brain Res.1678, 187–194. 10.1016/j.brainres.2017.10.003

149

Zhao M. Li L. (2015). Regulation of hematopoietic stem cells in the niche. Sci. China Life Sci.58 (12), 1209–1215. 10.1007/s11427-015-4960-y

150

Zhou L. Yang F. Yin J. W. Gu X. Xu Y. Liang Y. Q. (2020a). Compound K induces neurogenesis of neural stem cells in thrombin induced nerve injury through LXRα signaling in mice. Neurosci. Lett.729, 135007. 10.1016/j.neulet.2020.135007

151

Zhou Y. Wang Y. P. He Y. H. Ding J. C. (2020b). Ginsenoside Rg1 performs anti-aging functions by suppressing mitochondrial pathway-mediated apoptosis and activating sirtuin 3 (SIRT3)/Superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) pathway in sca-1⁺ HSC/HPC cells of an aging rat model. Med. Sci. Monit.26, e920666. 10.12659/MSM.920666

Summary

Keywords

ginsenosides, stem cells, proliferation, fate specification, differentiation, self-renewal

Citation

Liu Y, Jiang L, Song W, Wang C, Yu S, Qiao J, Wang X, Jin C, Zhao D, Bai X, Zhang P, Wang S and Liu M (2023) Ginsenosides on stem cells fate specification—a novel perspective. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 11:1190266. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2023.1190266

Received

20 March 2023

Accepted

22 June 2023

Published

05 July 2023

Volume

11 - 2023

Edited by

Myon Hee Lee, East Carolina University, United States

Reviewed by

Zhichao Xi, Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, China

Weinan Zhou, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2023 Liu, Jiang, Song, Wang, Yu, Qiao, Wang, Jin, Zhao, Bai, Zhang, Wang and Liu.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Siming Wang, lwsm126030@126.com; Meichen Liu, liumc0367@163.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.