Abstract

Pigs (Sus scrofa) are widely acknowledged as an important large mammalian animal model due to their similarity to human physiology, genetics, and immunology. Leveraging the full potential of this model presents significant opportunities for major advancements in the fields of comparative biology, disease modeling, and regenerative medicine. Thus, the derivation of pluripotent stem cells from this species can offer new tools for disease modeling and serve as a stepping stone to test future autologous or allogeneic cell-based therapies. Over the past few decades, great progress has been made in establishing porcine pluripotent stem cells (pPSCs), including embryonic stem cells (pESCs) derived from pre- and peri-implantation embryos, and porcine induced pluripotent stem cells (piPSCs) using a variety of cellular reprogramming strategies. However, the stabilization of pPSCs was not as straightforward as directly applying the culture conditions developed and optimized for murine or primate PSCs. Therefore, it has historically been challenging to establish stable pPSC lines that could pass stringent pluripotency tests. Here, we review recent advances in the establishment of stable porcine PSCs. We focus on the evolving derivation methods that eventually led to the establishment of pESCs and transgene-free piPSCs, as well as current challenges and opportunities in this rapidly advancing field.

Introduction

Recent research in both biomedical and veterinary medicine utilizing the pig (Sus scrofa) has demonstrated its application as a superb large animal model. Porcine models offer important advantages over other systems, proving more clinically informative compared to smaller murine models while being more practical and accessible than primates (Vodička et al., 2005; Schook et al., 2015; Niemann, 2019; Bertho and Meurens, 2021; Lunney et al., 2021). A well-annotated genome (Groenen et al., 2012; Warr et al., 2020; Pan et al., 2021), combined with advanced gene-editing techniques (Hammer et al., 1985; Luo et al., 2011; Hryhorowicz et al., 2017; Lee et al., 2017; Yan et al., 2018; Li et al., 2018; Perleberg, Kind, and Schnieke, 2018; Yang and Wu, 2018; Maynard et al., 2021; Li et al., 2022), has enabled the proliferation of pig models for disease modeling and comparative studies due to their similarities to humans in anatomical features, physiology, and immunology (Bendixen et al., 2010; Dawson et al., 2013; Lossi et al., 2016; Pabst, 2020; Bertho and Meurens, 2021; Lunney et al., 2021; Li et al., 2022). Thus, swine are positioned as ideal platforms for pre-clinical experimentation (Rouselle et al., 2016; Schomberg et al., 2017; Duran-Struuck, Huang, and Matar, 2019; Henze et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2021; Sper et al., 2022). For example, porcine pluripotent stem cells (pPSCs) or pPSC-derived endothelial cells have already been shown to improve in vivo recovery from myocardial infarction (Gu et al., 2012; Li et al., 2013) and promote angiogenesis (Li et al., 2021). The demonstration of this principle using autologous cell transplantation in swine would provide the large-animal, immunosuppression-free validation that is crucial to understanding the clinical potential of these therapeutic approaches (Martínez-Falguera, Iborra-Egea, and Gálvez-Montón, 2021). Similar work has already demonstrated the therapeutic promise of autologous pPSC-derived cell therapies for treating spinal cord injury (Strnadel et al., 2018), using swine as a highly clinically relevant model (Schomberg et al., 2017). Rapid progress in experimental pig-to-human organ xenotransplantation trials is also promising to address the issue of organ shortage and save countless lives (Lu et al., 2020; Porrett et al., 2022; Locke et al., 2023; Loupy et al., 2023; Moazami et al., 2023). Thus, pPSCs derived from early embryos and reprogrammed from somatic cells hold enormous potential in transforming cell therapy and transplantation strategies, while also contributing to a wide range of applications from comparative and developmental biology to agricultural science (Liu et al., 2014; Song et al., 2022; Li et al., 2022; Conrad et al., 2023; Zhu et al., 2023).

Early challenges in translating mouse and primate PSC derivation methods to pigs

Pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) have long been derived from murine and primate blastocysts (Evans and Kaufman, 1981; Martin, 1981; Thomson et al., 1995, 1996; 1998; Buehr et al., 2008; Li et al., 2008). Because PSCs represent only transient phases of early embryo development, extensive research has focused on the extrinsic (i.e., signaling pathways) and intrinsic factors (i.e., transcription factors) that regulate sustained self-renewal in culture (Chambers and Smith, 2004; Pan and Thomson, 2007; Sasaki et al., 2008; Ying et al., 2008; Hall et al., 2009; Plath and Lowry, 2011; Graf, Casanova, and Cinelli, 2011; Dejosez and Zwaka, 2012; Adachi and Niwa, 2013; Chen et al., 2015). These investigations laid the groundwork for the reprogramming of somatic cells using defined factors to generate induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) from mice and humans, marking an unparalleled breakthrough in regenerative medicine (Takahashi and Yamanaka, 2006; Takahashi et al., 2007; Yu et al., 2007).

Despite efforts spanning more than three decades, challenges have remained in deriving stable pPSCs routinely (Hall, 2013; Zhang et al., 2022). These challenges can be attributed, at least in part, to an incomplete understanding of the species-specific intricacies of early developmental processes in ungulates compared to more well-studied murine species (i.e., mouse and rat) (Perry and Rowlands, 1962; Lamming, 1993). Accordingly, attempts at deriving PSCs from ungulates faced challenges due to the differences in their developmental staging (Evans et al., 1990). For example, blastocysts in ungulates, including cows and pigs, undergo enormous expansion, forming structures such as the embryonic disc, chorion, and allantois, before eventually attaching to the endometrium (Lamming, 1993). Implantation of the ungulate embryo occurs only after a considerable delay, ranging from about 15 days after ovulation in pigs to up to 35 days in cows, compared to only 4 days in mice (Lamming, 1993; Paria, Huet-Hudson, and Dey, 1993). These species-specific differences in morphology and timing during early embryogenesis have influenced efforts to determine how and when pPSCs can be stabilized in vitro. Many review articles have elegantly summarized these past efforts in detail (Talbot and Blomberg, 2008; Blomberg and Telugu, 2012; Gandolfi et al., 2012; Malaver-Ortega et al., 2012; Koh and Piedrahita, 2014; Gonçalves, Ambrósio, and Piedrahita, 2014; Ezashi, Yuan, and Roberts, 2016; Han et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2022), much of which could not be included in this mini review due to limitations in scope.

Recent years have been remarkably productive, and major progress has been made with the generation of stable pPSCs from pre- and peri-implantation embryos (Choi et al., 2019; Gao et al., 2019; Kinoshita et al., 2021; Zhi et al., 2022). Concurrently, the derivation of transgene-free piPSCs using non-integrating cellular reprogramming techniques has finally been reported (Li et al., 2018; Yoshimatsu et al., 2021; Conrad et al., 2023; Zhu et al., 2023). Herein, we review this recent progress and the remaining challenges of this rapidly evolving field.

Recent progress in pPSCs derived from porcine embryos

The derivation of pESCs from early porcine embryos has been reported since the 1990s. ESC-like cell lines have been derived from embryos ranging between embryonic days 5 (E5) to 11 (E11) post-fertilization, a range which spans most of the pre-implantation, pre-gastrulation developmental period. In particular, these efforts have focused on the inner cell mass (ICM) or the epiblasts of early or hatched blastocysts (∼E5–E8) (Evans et al., 1990; Li et al., 2003; Brevini et al., 2010; Hou et al., 2016; Choi et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2019; Gao et al., 2019), or the embryonic disc of expanding bilaminar blastocysts (∼E8–E11) (Evans et al., 1990; Strojek et al., 1990; Hochereau-de Reviers and Perreau, 1993; Kinoshita et al., 2021; Zhi et al., 2022). However, complete and conclusive characterizations of most ESC-like lines have not been established. Preliminary characterizations have been consistently performed based on cell and colony morphology and the presence of canonical pluripotency markers, but these results have been remarkably variable between reports. Importantly, the more stringent tests of pluripotency (e.g., teratoma generation, chimeric potential, and germline transmission) remain to be comprehensively demonstrated.

Depending on the embryonic stage of origin, the signaling and culture conditions that allow for a stable expansion of the transient porcine pluripotent cell population can vary significantly. One example is the derivation of expanded potential stem cells (EPSCs) from mice (Yang et al., 2017), humans, and pigs (Gao et al., 2019). Based on combinatory small molecule screens, Gao et al. (2019) described a porcine EPSC (pEPSC) medium, using a cocktail of small molecules including a GSK3 inhibitor (CHIR99021), a SRC inhibitor (WH-4-023), a tankyrase inhibitor (XAV939), vitamin C, LIF, and activin A in an N2B27-based medium (Gao et al., 2019). The pEPSC medium enabled the derivation of stable pEPSC lines from pre-implantation blastocysts (day 5, in vivo derived; or day 7, parthenogenetically derived). The EPSCs could be maintained over 40 passages on STO feeders with an undifferentiated morphology and a normal karyotype. This study also concluded that pEPSCs have the potential to contribute to both embryonic and extraembryonic trophoblast lineages in chimeric assays. Future research is still required to better define the properties of the “expanded potential” state in relation to totipotency (Posfai et al., 2021).

Using a similar rationale to optimize derivation conditions, Choi et al. (2019) developed a pig ESC medium that contains KnockOut Serum Replacement (KOSR), lipid concentrate, FGF2, activin A, and WNT signaling modulators (CHIR99021 and IWR-1). This medium not only allowed for the expansion of SOX2-expressing cells from the ICM outgrowths, but also enabled the derivation of stable pESC lines from both IVF- and parthenogenetically-derived embryos (Choi et al., 2019). pESC lines were stably maintained for more than 1 year while maintaining stemness and a normal karyotype (Choi, Lee, Oh, Kim, Lee, Woo, et al., 2020). Interestingly, RNA-seq analysis showed that pESCs are transcriptionally closer to an epiblast-like state than to the ICM state (Secher et al., 2017; Choi, Lee, Oh, Kim, Lee, Kim, et al., 2020).

By carefully isolating the epithelial embryonic disc layer from pig embryonic day 11 pre-gastrulation spherical blastocysts, Kinoshita et al. (2021) derived stable embryonic disc stem cells (EDSCs) using an “AFX” medium (referred to as pEDSC medium hereafter: an N2B27-based medium supplemented with activin A, FGF2, and XAV939), and maintained the cells under hypoxic conditions (5% O2) at 38.5°C. Remarkably, the pEDSCs were able to readily adapt to feeder-free environments on fibronectin and laminin matrices. This represents a step forward in the complete and defined characterization of PSC maintenance, as feeder cells often suffer from batch-to-batch variabilities and could interfere with downstream analysis (Heng et al., 2004; Mallon et al., 2006). Transcriptomic analyses indicated that pEDSCs are similar to pESCs but distinct from pEPSCs. Interestingly, the pEDSC medium also stabilized EDSCs derived from sheep and bovine embryos, suggesting this may be a common state that can be stabilized across ungulates (Kinoshita et al., 2021).

By tracing the lineage trajectories of the pluripotent epiblast cells from E0–E14 pig pre-implantation embryos using single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq), Zhi et al. (2022) derived stable pig pre-gastrulation epiblast stem cells (pgEpiSCs) from E10 epiblast. The pgEpiSCs could be expanded in a “3i/LAF” medium for more than 240 passages while still retaining the ability to self-renew and differentiate. The 3i/LAF medium shares similarities with some of the pEPSC, pESC and pEDSC counterparts, using a N2B27-based medium, KOSR, CHIR99021, IWR-1, WH-4-023, LIF, activin A, and FGF2. Interestingly, when subjected to chimeric assays, pgEpiSCs only had a limited ability to contribute to the development of the host embryo. RNA-seq analysis showed that transcriptomic differences exist between pEPSCs, pEDSCs and pESCs (Kinoshita et al., 2021). Future research is required to elucidate whether these differences reflect biologically distinct stages of pluripotency or are based primarily on adaptation to the various culture conditions.

Technical challenges in the derivation of transgene-free piPSCs

The establishment of piPSCs using the Yamanaka reprogramming factors OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC (OSKM) delivered by retroviral/lentiviral vectors was reported in pigs since shortly after the first reported generation of mouse iPSCs, as we have summarized in Figure 1 and comprehensively annotated details in Table 1 (Wu et al., 2009; Esteban et al., 2009; Ezashi et al., 2009). These cell lines displayed conventional PSC properties and could be differentiated into three germ layers in vitro and form teratomas. Integrative reprogramming strategies have proven effective for efficiently making piPSC-like colonies from porcine somatic cells and have been used for many applications related to xenotransplantation and immunogenicity (Park et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2013), understanding key developmental signaling (Arai et al., 2013; Xu et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2022; Yuan et al., 2019), and deriving disease-relevant cell types (Gu et al., 2012; Aravalli, Cressman, and Steer, 2012; Yang et al., 2013; Park et al., 2016; Liao et al., 2018; Yu et al., 2022; Liao et al., 2023) (Table 1). However, an inevitable drawback of using integrating methods for introducing reprogramming factors is that they compromise the integrity of the host cell genome, raising their oncogenic potential (Prigione et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2014) and limiting their translational applications (Fan et al., 2013; Kang et al., 2015). There also tends to be an inverse relationship between the integration of a transgene and the expression of its endogenous counterpart (Hall et al., 2012). It is possible that transgene integration may counteract the activation of endogenous pluripotency factors by creating a reliance on the transgene and bypassing the process of complete epigenetic reprogramming, resulting in an unstable and artificial state of pluripotency (Hussein et al., 2014; Du et al., 2015). Thus, the ideal system is one in which piPSCs are transgene- and integration free, making them more faithful and self-sustaining models of pESC-like pluripotency.

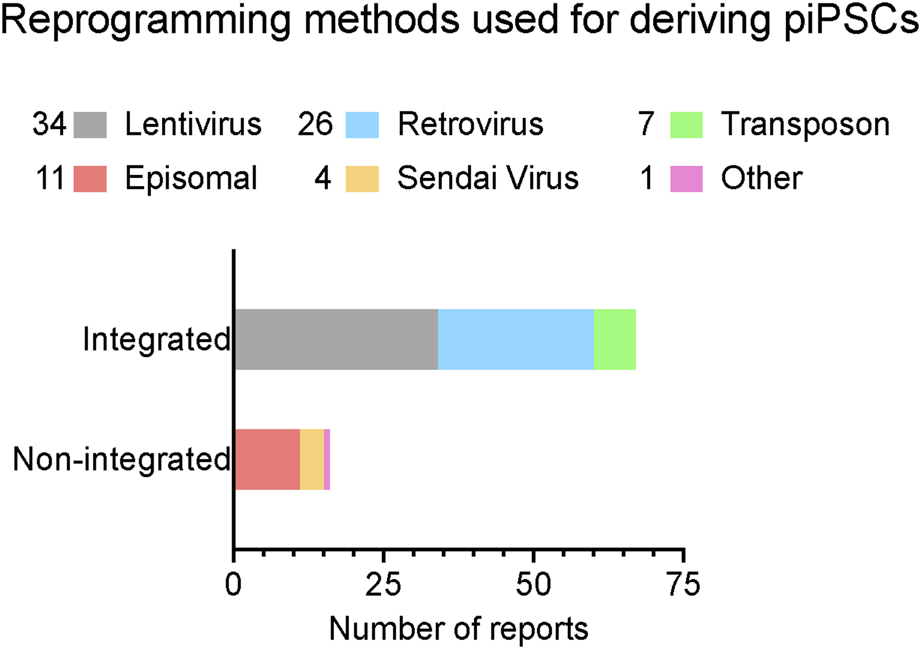

FIGURE 1

A summary of reported reprogramming methods used in published studies for deriving piPSCs. Reprogramming methods sorted by integration strategy. X-axis lists the number of reports that have been published using each strategy. Number of reports per method noted in legend. Further details are listed in Table 1. Reports were collected by performing systematic searches between September 2023 and January 2024 on NCBI PubMed with the key words “porcine induced pluripotent stem cell” and “piPSC” and “reprogramming”.

TABLE 1

| Strategy | Reprogramming method | Starting cell type | Reprogramming Factors | Species of the reprogramming factors | Teratoma assay | Chimeric assays | Transgene Free | Media Supplementation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Integrated | Lentivirus | Bone Marrow Cells | OSKM, NANOG, LIN28 | Human | Y | N | N | KOSR | Wu et al. (2009) |

| Fibroblasts | OSKM | Human | Y | N | N | KOSR + FGF2 | Ezashi et al. (2009, 2011) | ||

| OSKM, NANOG, LIN28 | Human | Y | N | N | KOSR | Wu et al. (2009) | |||

| Mesenchymal Stem Cells | OSKM, NANOG, LIN28 | Human | N | Y | N | mTeSR1 | West et al. (2010, 2011) | ||

| Adipose Stromal Cells | OSKM | Human | Y | N | N | FBS + bFGF | Gu et al. (2012) | ||

| Fibroblasts | OSKM | Human | N | N | N | N2B27 + BSA + mLIF + PD0325901 + CHIR + PD173074 | Rodríguez et al. (2012) | ||

| OSKM, NANOGP8 | Human | N | N | N | KOSR + bFGF | (Vanessa J. Hall et al. 2012) | |||

| OSKM, NANOG, LIN28 | Human | N | N | N | mTeSR1 | Yang et al. (2013), Gallegos-Cárdenas et al. (2015) | |||

| mTeSR1, KOSR + bFGF | Liu et al. (2013) | ||||||||

| Y | N | N | FBS + KOSR + LIF + bFGF | Kwon et al. (2013) | |||||

| Adipose-Derived Stem Cells | OSKM | Human | Y | N | N | KOSR + N2B27 + hLIF + PD0325901 + CHIR99021 | Zhang et al. (2014) | ||

| Fibroblasts | OSKM | Human | Y | N | N | FBS | Liao (2014) | ||

| FBS + KOSR + mLIF + bFGF | Ao et al. (2014) | ||||||||

| N | N | N | LIF + CHIR99021 + PD0325901; bFGF | Choi et al. (2016) | |||||

| Pig | Y | Chimeric embryos | N | PD0325901 + CHIR99021 + LIF; FGF2 | Secher et al. (2017) | ||||

| OSKM, NANOG, LIN28 | Human | N | N | N | KOSR, FBS, LIF | Kwon D. J. et al. (2017) | |||

| Mouse | Y | Chimeric embryos | N | LIF + FGF2 + PD0325901 + CHIR99021 + thiazovivin + GFx | Fukuda et al. (2017) | ||||

| OSKM | Human | N | N | N | PL + BMP4 + SCF + IL-6 + CHIR99021 + SB431542 + PD0325901 | Ma et al. (2018) | |||

| FBS | Liao et al. (2018) | ||||||||

| FBS + hLIF + bFGF + CHIR99021 + SB431542 | Shen et al. (2019) | ||||||||

| N2B27 + hLIF + Vc + ITS-A + PD0325901 + CHIR99021 + Gö6983 | Habekost et al. (2019) | ||||||||

| OSKM, NANOG, LIN28 | Human | Y | N | N | mTeSR1 | Burrell et al. (2019) | |||

| OSKM | Human | N | N | N | KOSR + bFGF | Machado et al. (2020) | |||

| N2B27 + KOSR + CHIR99021 + PD0325901 + hLIF + pLIF | Shi et al. (2020) | ||||||||

| Not specified | Jiang et al. (2022) | ||||||||

| Mouse | N | N | N | KOSR + LIF; KOSR + bFGF; KOSR +bFGF + LIF | Pieri et al. (2022) | ||||

| Fibroblasts; Sertoli Cells | OSKM | Pig | N | N | N | FBS + LIF + bFGF + CHIR99021 + SB431542 | Yu et al. (2022) | ||

| Urine-derived Cells | OSKM | Mouse | N | N | N | KOSR + bFGF | Recchia et al. (2022) | ||

| Fibroblasts | OSKM | Not specified | N | N | N | KOSR + FGF2 | Guo et al. (2023) | ||

| Mouse | N | N | N | KOSR + N2B27 + BSA + bFGF + LIF + CHIR99021 + PD0325901 + SB431542 + Vc | Zhou et al. (2023) | ||||

| Human | N | N | N | FBS + KOSR + LIF | Baek et al. (2023) | ||||

| OSKM, NANOG, LIN28 | Human | N | N | N | FBS + KOSR + LIF | Baek et al. (2023) | |||

| OSKM, BRG1 | Human | N | N | N | FBS + bFGF + hLIF + dorsomorhpin | Ren et al. (2024) | |||

| OSKM, TBX3 | Human, Pig | Y | Chimeric embryos | N | FBS + LIF + bFGF + CHIR99021 + SB431542 | Shen et al. (2024) | |||

| Integrated | Retrovirus | Fibroblasts | OSKM | Human | Y | N | N | FBS + bFGF | Esteban et al. (2009) |

| Mouse | Y | N | N | FBS + bFGF | Esteban et al. (2009) | ||||

| Human | Y | N | N | FBS + KOSR + LIF + bFGF | Ruan et al. (2011) | ||||

| Mouse | N | N | N | KOSR + hLIF | Thomson et al. (2012) | ||||

| Y | Chimeric blastocysts | N | FBS + LIF + bFGF | Cheng et al. (2012) | |||||

| SKM | Mouse | Y | N | N | FBS + KOSR + LIF + bFGF | Montserrat et al. (2012) | |||

| Mesenchymal Stem Cells | OK | Pig | Y | N | N | KOSR or FBS + hLIF | Liu et al. (2012) | ||

| Fibroblasts | M, NR5A2 | Mouse | N | N | N | KOSR + N2B27 + BSA + hLIF + bFGF | Wang et al. (2013) | ||

| NR5A2 | Mouse | N | N | N | KOSR + N2B27 + BSA + hLIF + bFGF | Wang et al. (2013) | |||

| OSKM | Human | N | N | N | FBS + KOSR + bFGF | Park et al. (2013) | |||

| Chimeric embryos | N | KOSR + forskolin + pLIF | Fujishiro et al. (2013) | ||||||

| KOSR + forskolin + pLIF + PD0325901 + CHIR99021 | Arai et al. (2013) | ||||||||

| Mouse | Y | N | N | KOSR + N2B27 + BSA + hLIF + bFGF | Wang et al. (2013), Wei et al. (2020), Li et al. (2021) | ||||

| OSKM, NR5A2, TBX3 | Mouse | Y | N | N | KOSR + N2B27 + BSA + hLIF + bFGF | Wang et al. (2013) | |||

| OSKM | Human | Y | N | N | KOSR + bFGF | Li et al. (2014) | |||

| Mouse | Y | N | N | KOSR + N2B27 + LIF + bFGF + PD0325901 + CHIR99021 + SB431542 + Vc | Gu et al. (2014) | ||||

| OSK, miR302a, miR302b, miR200c | Mouse | Y | N | N | KOSR + LIF | Ma et al. (2014) | |||

| OSKM, TERT | Human | Y | Chimeric blastocysts | N | FBS + KOSR + LIF + bFGF | Gao et al. (2014) | |||

| OSKM | Human | Y | N | N | FBS + hLIF + FGF2 + BMP4 + CHIR99021 + SB431542 | Zhang et al. (2015) | |||

| N | Chimeric blastocysts | N | FBS + bFGF + SCF | Park et al. (2016) | |||||

| N | N | FBS + hLIF + bFGF + CHIR99021 + SB431542 | Yu et al. (2017) | ||||||

| OSKM, TET1, KDM3A | Human, Mouse | Y | N | N | KOSR + FBS + hLIF + HDACi | Mao et al. (2017) | |||

| OSKM | Pig | Y | Chimeric embryos | N | FBS + hLIF + CHIR99021 + PD0325901 + AlbuMAX | Zhang et al. (2018) | |||

| OSKM, ESRRB | Human, Pig | N | N | N | FBS + hLIF + FGF2 + BMP4 + CHIR99021 + SB431542 | Yang et al. (2018) | |||

| Fibroblasts; Pericytes | OSKM | Pig | N | Chimeric embryos | N | N2B27 + KOSR + LIF + CHIR99021 + (S)-(+)-Dimethindene Maleate + Minocycline Hydrochloride + Vc | Xu et al. (2019) | ||

| Sertoli Cells | OSKM | Human | Y | N | N | KOSR + FBS + bFGF + hLIF | Setthawong et al. (2019) | ||

| Fibroblasts | OSKM | Human | N | N | N | KOSR + FBS + bFGF + hLIF | Setthawong et al. (2021) | ||

| OSKM, LIN28 | Human | Y | N | N | KOSR + FBS + mLIF + bFGF | Chakritbudsabong et al. (2021) | |||

| Integrated | Transposon (Sleeping Beauty) | Fibroblasts | OSKM | Mouse | Y | N | N | KOSR + bFGF | Kues et al. (2013) |

| OSKM, NANOG, LIN28 | Human, Pig | N | N | N | KOSR + mLIF + bFGF | Petkov et al. (2013) | |||

| FBS + KOSR + mLIF | Petkov et al. (2013) | ||||||||

| FBS + SAHA + VPA + NaB + Vc | Petkov et al. (2016) | ||||||||

| Transposon (PiggyBac) | Fibroblasts | OSKM | Human | N | N | N | N2B27 + CHIR99021 + PD0325901 + hLIF | Yu et al. (2018) | |

| OSKM, NANOG, LIN28, LRH1, RARG | Human, Pig | N | Chimeric embryos | N | N2B27 + CHIR99021 + WH-4-023 + XAV939/IWR1 + Vc + LIF + Activin + FBS | Gao et al. (2019) | |||

| Cow, Human | N | N | N | N2B27 + CHIR99021 + WH-4-023 + XAV939 + Vc + LIF + Activin + FBS | Zhou et al. (2023) | ||||

| Pig, Human | N | Chimeric embryos | N | N2B27 + CHIR99021 + WH-4-023 + XAV939 + Vc + LIF + Activin + FBS | Zhou et al. (2023) | ||||

| Non-integrated | Germinal Vesicle Oocyte Extract | Fibroblasts | N/A | Pig | Y | Chimeric blastocysts | N/A | ES medium | Bui et al. (2012) |

| Sendai Virus | Fibroblasts | OSKM | Human | N | N | N | Not specified | Juhasova et al. (2015) | |

| Y | N | N | FBS + KOSR + bFGF | Congras et al. (2016) | |||||

| KOSR + bFGF | Strnadel et al. (2018) | ||||||||

| N | N | Y | KOSR + bFGF | Baek et al. (2023) | |||||

| Episomal Plasmid | Fibroblasts | OSKM, NANOG, LIN28 | Human, Mouse | Y | N | N | KOSR + PD0325901 + CHIR99021 + hLIF + VPA | Telugu et al. (2010) | |

| OSKM | Mouse | Y | N | N | FBS + KOSR + LIF + bFGF | Montserrat et al. (2011) | |||

| OSK | Human | N | N | N | KOSR | Aravalli et al. (2012) | |||

| OSKM | Mouse | N | N | N | FBS + SCF + bFGF | Park et al. (2013) | |||

| OSKM, NANOG, LIN28, NR5A2, miR302/367 | Human | Y | Chimeric blastocysts | N | N2B27 + CHIR99021 + PD0325901 + mLIF | Du et al. (2015) | |||

| OSKM, LIN28, shP53 | Human | Y | N | Y | KOSR + bFGF + PD0325901 + CHIR99021 | Li et al. (2018) | |||

| N | KOSR + hLIF + hFGF2 + BIRB796 + SP600125 + LDN193189 + CHIR99021 + PD0325901 + SB431542 | Yuan et al. (2019) | |||||||

| OSKM, NANOG, LIN28, KLF2, KDM4D, GLIS1, mP53DD | Human, Mouse, Marmoset | N | N | Y | KOSR + bFGF + Activin A + TGFb1 + IWP2 | Yoshimatsu et al. (2021) | |||

| OSKM, NANOG, LIN28, NR5A2, BAF60A, miR302-367 | Human | Y | N | N | E8 + Activin A + CHIR99021 + IWR1 + LIF | Jiao et al. (2022) | |||

| OSKM, BCL2L1 | Human | Y | N | Y | N2B27 + KOSR + Vc + bFGF + Activin A + hLIF + CHIR99021 + IWR1 + WH-4-023 | Zhu et al. (2023) | |||

| OSKM, NANOG, LIN28, SV40LT, miR302-367 | Human | Y | N | Y | KOSR + FGF2 + Activin A + CHIR99021 + IWR1 | Conrad et al. (2023) |

Systematic annotation of reprogramming methods used for generating PiPSCs.

Various delivery methods are highlighted by color. OSKM = OCT3/4, SOX2, KLF4, MYC. Y, yes; N, No; KOSR, KnockOut™ Serum Replacement; FBS, Fetal Bovine Serum; BSA, bovine serum albumin.

Attempts to make transgene free piPSCs using episomal reprogramming methods continued for years, but the challenges of integration and retention stubbornly persisted (Telugu, Ezashi, and Roberts, 2010; Montserrat et al., 2011; Aravalli, Cressman, and Steer, 2012; Park et al., 2013). Although piPSC-like cultures were produced, none of the resulting cell lines were able to demonstrate complete transgene loss (Du et al., 2015). Even in the case of Sendai virus-based reprogramming, which uses minus-strand RNA as a template to encode reprogramming factors and is thus incapable of integrating into the host genome, the viral sequences were either maintained in the derived piPSC populations (Congras et al., 2016) or not shown to be absent in the pluripotent state (Juhasova et al., 2015; Strnadel et al., 2018). The exact causes of transgene retention are unclear, but issues with cell viability, proliferative advantage, and incomplete signaling conditions are all potential factors (Silva et al., 2008; Golipour et al., 2012; Chia et al., 2017). For example, it is possible that cells which retain the transgenes gain a competitive advantage over cells that do not, as the early reprogramming process is known to result in a significant increase in cell cycling and mitotic rate (Ruiz et al., 2011; Guo et al., 2014). Due to these challenges, the establishment of genuine transgene-free piPSCs remained elusive.

Recent progress in transgene-free piPSC derivation

More recently, using eight episomal plasmids encoding a set of eleven reprogramming factors, Yoshimatsu et al. (2021) were able to carefully study the reprogramming intermediates and show that somatic cells temporarily acquired a neural stem cell-like state during the transition. Stable piPSC colonies were established in the process and expanded in an “ESM” medium, which includes activin A, TGF1, and IWP2 (a WNT signaling inhibitor), similar to the conditions described above for deriving pESCs and ESC-like cells. In this reprogramming regime, the piPSCs lost the transgenes in approximately five passages after clonal isolation and expansion. Interestingly, this reprogramming protocol was also applied to the establishment of transgene-free marmoset and dog iPSCs, highlighting potential shared reprogramming paradigms and mechanisms.

Building on the successful establishment of pgEpiSCs (Zhi et al., 2022), Zhu et al. (2023) reprogrammed fibroblasts by electroporating up to six episomal plasmids encoding seven reprogramming factors to establish episomally derived piPSCs (epi-iPSC). These epi-iPSCs were maintained in the aforementioned 3i/LAF medium, lost their episomal plasmids around passage 8, and are remarkably similar to pgEpiSCs in their transcriptomic signatures, proliferation profile and capacity for self-renewal.

Similarly, using the pESC medium reported by Choi et al. (2019), Conrad et al. (2023) established transgene-free piPSCs using three episomal plasmids encoding seven reprogramming factors. As had been reported in human iPSCs, co-electroporating a microRNA302/367 cassette greatly enhanced the efficiency of primary colony formation (Kuo et al., 2012; Howden et al., 2015). The clonally amplified piPSC lines lost detectable episomal plasmids by around passage 10 and maintained their undifferentiated morphology for more than 50 passages in the pESC medium. These transgene-free piPSCs were very similar to pESCs in gene expression signatures and were capable of differentiating into progenitors representing the primary three germ layers and forming teratomas in immunocompromised mice. Compellingly, when used to model the segmentation clock, these piPSCs preserve an ungulate-specific developmental allochronic phenotype in vitro (Conrad et al., 2023; Lázaro et al., 2023).

Across these reports (Table 1, orange colored section), culture conditions shared certain key commonalities, including the use of serum replacement and bFGF. However, the lack of consistency in many other components (such as TGF- and WNT-modulators) points to at least two possibilites; these cell lines may represent meaningfully divergent pluripotency states with distinct signalling requirements, or some of these components may not be essential for maintaining porcine pluripotency. Further research will be necessary to elucidate these differences.

Current challenges and future directions of pPSC research

Demonstration of complete developmental potential

Our understanding of pluripotency remains incomplete. Since cellular reprogramming is known to be stochastic and highly variable, a state of complete, genome-wide reprogramming (absent of somatic imprinting or methylation patterns) needs to be clearly demonstrated. To validate complete reprogramming of the produced iPSC lines, the generation of an all-iPSC animal is ultimately required (Nagy et al., 1993; Tam and Rossant, 2003), a feat thus far only achieved by high quality mouse iPSCs (Zhao et al., 2009; Kang et al., 2009; Boland et al., 2009). Similarly, germline competence has only been conclusively shown for mouse and rat iPSCs (Okita et al., 2007; Hamanaka et al., 2011). Despite the recent advancements in pPSC research, it remains to be determined whether any of the pEPSCs, pEDSCs, pESCs, pgEpiSCs, or transgene-free piPSCs are germline competent and whether they could contribute to the development of all-PSC animal (West et al., 2011; Secher et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2016; Posfai et al., 2021). It will also be beneficial to compare existing piPSC and pPSC derivation methods more systematically, to establish efficient and reproducible protocols that can be scaled and adopted more widely.

Improved understanding of the porcine pluripotent state

A variety of states of pluripotency have been characterized by adapting novel cell culture conditions. For example, these include naïve (Ying et al., 2008; Nichols et al., 2009; Nichols and Smith, 2009), primed (Brons et al., 2007; Tesar et al., 2007), region-selective (Wu et al., 2015), rosette-stage (Neagu et al., 2020), intermediate (Zhang et al., 2015; Yu, Wei, Sun, et al., 2021), and formative (Smith, 2017; Zhi et al., 2022) states, which represent a diverse spectrum of states from early mammalian embryos (Hall and Hyttel, 2014; Bernardo et al., 2018). To pinpoint the exact state of reprogrammed piPSC lines, it is necessary to compare with embryos or embryo-derived PSCs as the “gold standard” (Weefrnig et al., 2007; Chung et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2018; Jiang et al., 2022; Conrad et al., 2023). Systematic, robust, cross-species comparative studies will continue to be highly informative to understanding these cell types in relation to each other (Habekost et al., 2019; Simpson et al., 2023), and would in turn provide insights into the conserved mechanisms of early mammalian development (Ben-Nun et al., 2011; Shahbazi et al., 2017; Boroviak and Nichols, 2017; Yu, Wei, Sun, et al., 2021; Soto et al., 2021; Zywitza et al., 2022; Déjosez et al., 2023; MacCarthy et al., 2024). The continued development of PSCs from new species will be instrumental to this understanding (Rayon et al., 2020; Lázaro et al., 2023). A promising development is the generation of a chimeric factor, SOX2-17, or super-SOX, which greatly enhanced the derivation of iPSCs from pigs as well as mice, humans, cynomolgus macaques, and cows (MacCarthy et al., 2024). The SOX2-17 factor stabilized SOX2/OCT4 dimerization and improved the ability to form all iPSC-mice by tetraploid complementation. This factor also supported a naïve reset in multiple species, suggestive of a conserved mechanism that could be further applied to many other species.

Applied differentiation of pPSCs to functional cell types

Finally, the direct differentiation of pPSCs into functional, mature cell types for regenerative medicine applications remains to be fully investigated. While early works have shown that pPSCs can readily differentiate into lineage-specific progenitors using protocols already developed for murine and human PSCs, tailoring the differentiation paradigm specifically for producing mature porcine cells will ultimately be required (Gu et al., 2012; Aravalli, Cressman, and Steer, 2012; Yang et al., 2013; Liao et al., 2018; Jeon et al., 2021). Nevertheless, progress is rapidly unfolding. A recent study showed that pgEpiSCs can be differentiated into skeletal muscle fibers and form three-dimensional meat-like tissues (Zhu et al., 2023). When combined with other improvements in the expansion of primary muscle stem cells and adipose-derived stem cells, these represent a step forward to the development of cultured meat products from an unlimited cellular source (Li et al., 2022; Song et al., 2022). Consistent developments in xenotransplantation are equally promising (Strnadel et al., 2018; Porrett et al., 2022; Locke et al., 2023; Loupy et al., 2023; Moazami et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2023), with pPSCs providing the ideal platform for generating pigs that can be readily modified and adapted according to clinical need. For example, the knockout of key immunogenic antigens has been proven to increase immune tolerance in pig-to-human xenotransplantation (Liu et al., 2013; Xu et al., 2022). Recent advances in whole- or partial-embryo modelling could also unlock new, previously inaccessible stages of developmental biology once they are translated to swine (Liu et al., 2021; Yu, Wei, Duan, et al., 2021; Tarazi et al., 2022; Weatherbee et al., 2023; Amadei et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2023; Oldak et al., 2023; Wu et al., 2023). Broadly speaking, the field is at an exciting juncture, with the potential for groundbreaking developments in regenerative medicine, disease modeling, and cell therapy.

Statements

Author contributions

JN: Validation, Methodology, Visualization, Investigation, Data curation, Writing–review and editing, Writing–original draft, Conceptualization. JVC: Validation, Methodology, Writing–review and editing, Writing–original draft, Visualization, Investigation, Data curation. MR: Validation, Writing–review and editing, Writing–original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation. L-FC: Visualization, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization, Writing–review and editing, Writing–original draft.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was undertaken thanks to funding support from the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Calgary (UCVM), Alberta Children’s Hospital Research Institute (ACHRI), the Canada Research Chairs Program (CRC, L-FC, 950-232985), Canada Foundation for Innovation (CFI, L-FC, 40653), Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC, L-FC, RGPIN-2021-02580) and the Government of Canada’s New Frontiers in Research Fund (NFRFE-2020-00446, NFRFE-2023-00170).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the many pioneers and scientists who have dedicated their work to elucidating the mechanisms underpinning pluripotency and species-specific comparative embryology. Due to space limitations, we apologize for not being able to mention all the important works contributing to our understanding of the porcine pluripotent stem cells in this article. We thank all members of the Chu Laboratory for their helpful comments on this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Adachi K. Niwa H. (2013). A liaison between intrinsic and extrinsic regulators of pluripotency. EMBO J.32 (19), 2531–2532. 10.1038/emboj.2013.196

2

Amadei G. Handford C. E. Qiu C. De Jonghe J. Greenfeld H. Tran M. et al (2022). Embryo model completes gastrulation to neurulation and organogenesis. Nature610 (7930), 143–153. 10.1038/s41586-022-05246-3

3

Ao Y. Mich-Basso J. D. Lin Bo Yang L. (2014). High efficient differentiation of functional hepatocytes from porcine induced pluripotent stem cells. PloS One9 (6), e100417. 10.1371/journal.pone.0100417

4

Arai Y. Jun O. Fujishiro S.-hei Nakano K. Matsunari H. Watanabe M. et al (2013). DNA methylation profiles provide a viable index for porcine pluripotent stem cells. Genes. (New York, N.Y. 2000)51 (11), 763–776. 10.1002/dvg.22423

5

Aravalli R. N. Cressman E. N. K. Steer C. J. (2012). Hepatic differentiation of porcine induced pluripotent stem cells in vitro. Veterinary J.194 (3), 369–374. 10.1016/j.tvjl.2012.05.013

6

Baek S.-Ki Lee I.-W. Lee Y.-Ji Seo B.-G. Choi J.-W. Kim T.-S. et al (2023). Comparative pluripotent characteristics of porcine induced pluripotent stem cells generated using different viral transduction systems. J. Animal Reproduction Biotechnol.38 (4), 275–290. 10.12750/JARB.38.4.275

7

Bendixen E. Danielsen M. Larsen K. Bendixen C. (2010). Advances in porcine genomics and proteomics--a toolbox for developing the pig as a model organism for molecular biomedical research. Briefings Funct. Genomics9 (3), 208–219. 10.1093/bfgp/elq004

8

Ben-NunInbar F. Montague S. C. Houck M. L. Tran Ha T. Garitaonandia I. Leonardo T. R. et al (2011). Induced pluripotent stem cells from highly endangered species. Nat. Methods8 (10), 829–831. 10.1038/nmeth.1706

9

Bernardo A. S. Jouneau A. Marks H. Kensche P. Kobolak J. Freude K. et al (2018). Mammalian embryo comparison identifies novel pluripotency genes associated with the naïve or primed state. Biol. Open, January, bio7, 033282. 10.1242/bio.033282

10

Bertho N. François M. (2021). The pig as a medical model for acquired respiratory diseases and dysfunctions: an immunological perspective. Mol. Immunol.135 (July), 254–267. 10.1016/j.molimm.2021.03.014

11

Blomberg L. A. Telugu B. P. V. L. (2012). Twenty years of embryonic stem cell research in farm animals. Reproduction Domest. Animals = Zuchthygiene47 (Suppl. 4 (August), 80–85. 10.1111/j.1439-0531.2012.02059.x

12

Boland M. J. Hazen J. L. Nazor K. L. Rodriguez A. R. Gifford W. Martin G. et al (2009). Adult mice generated from induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature461 (7260), 91–94. 10.1038/nature08310

13

Boroviak T. Nichols J. (2017). Primate embryogenesis predicts the hallmarks of human naïve pluripotency. Development144 (2), 175–186. 10.1242/dev.145177

14

Brevini T. A. L. Pennarossa G. Attanasio L. Vanelli A. Gasparrini B. Gandolfi F. (2010). Culture conditions and signalling networks promoting the establishment of cell lines from parthenogenetic and biparental pig embryos. Stem Cell. Rev. Rep.6 (3), 484–495. 10.1007/s12015-010-9153-2

15

Brons I. G. M. Smithers L. E. Trotter M. W. B. Rugg-Gunn P. Sun B. Chuva De Sousa Lopes S. M. et al (2007). Derivation of pluripotent epiblast stem cells from mammalian embryos. Nature448 (7150), 191–195. 10.1038/nature05950

16

Buehr M. Meek S. Blair K. Yang J. Ure J. Silva J. et al (2008). Capture of authentic embryonic stem cells from rat blastocysts. Cell.135 (7), 1287–1298. 10.1016/j.cell.2008.12.007

17

Bui H.-T. Kwon D.-N. Kang M.-H. Oh M.-H. Park M.-R. Park W.-J. et al (2012). Epigenetic reprogramming in somatic cells induced by extract from germinal vesicle stage pig oocytes. Dev. Camb. Engl.139 (23), 4330–4340. 10.1242/dev.086116

18

Burrell K. Dardari R. Goldsmith T. Toms D. Villagomez D. A. F. King W. A. et al (2019). Stirred suspension bioreactor culture of porcine induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells Dev.28 (18), 1264–1275. 10.1089/scd.2019.0111

19

Chakritbudsabong W. Chaiwattanarungruengpaisan S. Sariya L. Pamonsupornvichit S. Ferreira J. N. Sukho P. et al (2021). Exogenous LIN28 is required for the maintenance of self-renewal and pluripotency in presumptive porcine-induced pluripotent stem cells. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol.9, 709286. 10.3389/fcell.2021.709286

20

Chambers I. Smith A. (2004). Self-renewal of teratocarcinoma and embryonic stem cells. Oncogene23 (43), 7150–7160. 10.1038/sj.onc.1207930

21

Chen Xi Ye S. Ying Q.-L. (2015). Stem cell maintenance by manipulating signaling pathways: past, current and future. BMB Rep.48 (12), 668–676. 10.5483/BMBRep.2015.48.12.215

22

Chen Y. Williams V. Filippova M. Filippov V. Duerksen-Hughes P. (2014). Viral carcinogenesis: factors inducing DNA damage and virus integration. Cancers6 (4), 2155–2186. 10.3390/cancers6042155

23

Cheng De Guo Y. Li Z. Liu Y. Gao X. Gao Yi et al (2012). Porcine induced pluripotent stem cells require LIF and maintain their developmental potential in early stage of embryos. PloS One7 (12), e51778. 10.1371/journal.pone.0051778

24

Chia G. Agudo J. Treff N. Sauer M. V. Billing D. Brown B. D. et al (2017). Genomic instability during reprogramming by nuclear transfer is DNA replication dependent. Nat. Cell. Biol.19 (4), 282–291. 10.1038/ncb3485

25

Choi K.-H. Lee D.-K. Kim S. W. Woo S.-Ho Kim D.-Y. Lee C.-K. (2019). Chemically defined media can maintain pig pluripotency network in vitro. Stem Cell. Rep.13 (1), 221–234. 10.1016/j.stemcr.2019.05.028

26

Choi K.-H. Lee D.-K. Oh J.-N. Kim S.-H. Lee M. Kim S. W. et al (2020). Transcriptome profiling of pluripotent pig embryonic stem cells originating from uni- and biparental embryos. BMC Res. Notes13 (1), 144. 10.1186/s13104-020-04987-6

27

Choi K.-H. Lee D.-K. Oh J.-N. Kim S.-H. Lee M. Woo S.-Ho et al (2020). Pluripotent pig embryonic stem cell lines originating from in vitro-Fertilized and parthenogenetic embryos. Stem Cell. Res.49 (December), 102093. 10.1016/j.scr.2020.102093

28

Choi K.-H. Park J.-K. Son D. Hwang J. Y. Lee D.-K. Ka H. et al (2016). Reactivation of endogenous genes and epigenetic remodeling are barriers for generating transgene-free induced pluripotent stem cells in pig. PloS One11 (6), e0158046. 10.1371/journal.pone.0158046

29

Chung K.-M. Frederick W. K.Iv Gajdosik M. D. Burger S. Russell A. C. Craig E. N. (2014). “Single cell analysis reveals the stochastic phase of reprogramming to pluripotency is an ordered probabilistic process,”. Editor John CooneyA., 9. 10.1371/journal.pone.0095304

30

Congras A. Barasc H. Canale-Tabet K. Plisson-Petit F. Delcros C. Feraud O. et al (2016). Non integrative strategy decreases chromosome instability and improves endogenous pluripotency genes reactivation in porcine induced pluripotent-like stem cells. Sci. Rep.6 (June), 27059. 10.1038/srep27059

31

Conrad J. V. Meyer S. Ramesh P. S. Neira J. A. Rusteika M. Mamott D. et al (2023). Efficient derivation of transgene-free porcine induced pluripotent stem cells enables in vitro modeling of species-specific developmental timing. Stem Cell. Rep.18 (23), 2328–2343. 10.1016/j.stemcr.2023.10.009

32

Dawson H. D. Loveland J. E. Pascal G. Gilbert J.Gr Uenishi H. Mann K. M. et al (2013). Structural and functional annotation of the porcine immunome. BMC Genomics14 (1), 332. 10.1186/1471-2164-14-332

33

Déjosez M. Marin A. Hughes G. M. Morales A. E. Godoy-Parejo C. Gray J. L. et al (2023). Bat pluripotent stem cells reveal unusual entanglement between host and viruses. Cell.186 (5), 957–974.e28. 10.1016/j.cell.2023.01.011

34

Dejosez M. Zwaka T. P. (2012). Pluripotency and nuclear reprogramming. Annu. Rev. Biochem.81, 737–765. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-052709-104948

35

Du X. Feng T. Yu D. Wu Y. Zou H. Ma S. et al (2015). Barriers for deriving transgene-free pig iPS cells with episomal vectors. Stem Cells33 (11), 3228–3238. 10.1002/stem.2089

36

Duran-Struuck R. Huang C. A. Matar A. J. (2019). Cellular therapies for the treatment of hematological malignancies; swine are an ideal preclinical model. Front. Oncol.9 (June), 418. 10.3389/fonc.2019.00418

37

Esteban M. A. Xu J. Yang J. Peng M. Qin D. Wen Li et al (2009). Generation of induced pluripotent stem cell lines from Tibetan miniature pig. J. Biol. Chem.284 (26), 17634–17640. 10.1074/jbc.M109.008938

38

Evans M. J. Kaufman M. H. (1981). Establishment in culture of pluripotential cells from mouse embryos. Nature292 (5819), 154–156. 10.1038/292154a0

39

Evans M. J. Notarianni E. Laurie S. Moor R. M. (1990). Derivation and preliminary characterization of pluripotent cell lines from porcine and bovine blastocysts. Theriogenology33 (1), 125–128. 10.1016/0093-691X(90)90603-Q

40

Ezashi T. Matsuyama H. Telugu B. P. V. L. Michael Roberts R. (2011). Generation of colonies of induced trophoblast cells during standard reprogramming of porcine fibroblasts to induced pluripotent stem cells. Biol. Reproduction85 (4), 779–787. Porcine Induced pluripotent stem cells produce chimeric offspring. 10.1095/biolreprod.111.092809

41

Ezashi T. Matsuyama H. Telugu B. P. V. L. Michael Roberts R. (2011). Generation of colonies of induced trophoblast cells during standard reprogramming of porcine fibroblasts to induced pluripotent stem cells. Biol. Reproduction85 (4), 779–787. 10.1095/biolreprod.111.092809

42

Ezashi T. Telugu B. P. V. L. Alexenko A. P. Sachdev S. Sinha S. Roberts R. M. (2009). Derivation of induced pluripotent stem cells from pig somatic cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.106 (27), 10993–10998. 10.1073/pnas.0905284106

43

Ezashi T. Yuan Ye Michael Roberts R. (2016). Pluripotent stem cells from domesticated mammals. Annu. Rev. Animal Biosci.4, 223–253. 10.1146/annurev-animal-021815-111202

44

Fan N. Chen J. Shang Z. Dou H. Ji G. Zou Q. et al (2013). Piglets cloned from induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell. Res.23 (1), 162–166. 10.1038/cr.2012.176

45

Fujishiro S.-hei Nakano K. Mizukami Y. Azami T. Arai Y. Matsunari H. et al (2013). Generation of naive-like porcine-induced pluripotent stem cells capable of contributing to embryonic and fetal development. Stem Cells Dev.22 (3), 473–482. 10.1089/scd.2012.0173

46

Fukuda T. Tani T. Haraguchi S. Donai K. Nakajima N. Uenishi H. et al (2017). Expression of six proteins causes reprogramming of porcine fibroblasts into induced pluripotent stem cells with both active X chromosomes. J. Cell. Biochem.118 (3), 537–553. 10.1002/jcb.25727

47

Gallegos-Cárdenas A. Webb R. Jordan E. West R. West F. D. Yang J.-Y. et al (2015). Pig induced pluripotent stem cell-derived neural rosettes developmentally mimic human pluripotent stem cell neural differentiation. Stem Cells Dev.24 (16), 1901–1911. 10.1089/scd.2015.0025

48

Gandolfi F. Pennarossa G. Maffei S. Brevini T. (2012). Why is it so difficult to derive pluripotent stem cells in domestic ungulates?Reproduction Domest. Animals = Zuchthygiene47 (Suppl. 5 (August), 11–17. 10.1111/j.1439-0531.2012.02106.x

49

Gao X. Nowak-Imialek M. Chen Xi Chen D. Herrmann D. Ruan D. et al (2019). Establishment of porcine and human expanded potential stem cells. Nat. Cell. Biol.21 (6), 687–699. 10.1038/s41556-019-0333-2

50

Gao Yi Guo Y. Duan A. Cheng De Zhang S. Wang H. (2014). Optimization of culture conditions for maintaining porcine induced pluripotent stem cells. DNA Cell. Biol.33 (1), 1–11. 10.1089/dna.2013.2095

51

Godehardt A. W. Petkov S. Gulich B. Fischer N. Niemann H. Tönjes R. R. (2018). Comparative gene expression profiling of pig-derived iPSC-like cells: effects of induced pluripotency on expression of porcine endogenous retrovirus (PERV). Xenotransplantation25 (4), e12429. 10.1111/xen.12429

52

Golipour A. Laurent D. Liu Yu Jayakumaran G. Hirsch C. L. Trcka D. et al (2012). A late transition in somatic cell reprogramming requires regulators distinct from the pluripotency network. Cell. Stem Cell.11 (6), 769–782. 10.1016/j.stem.2012.11.008

53

Gonçalves N. N. Ambrósio C. E. Piedrahita J. A. (2014). Stem cells and regenerative medicine in domestic and companion animals: a multispecies perspective. Reproduction Domest. Animals = Zuchthygiene49 (Suppl. 4 (October), 2–10. 10.1111/rda.12392

54

Graf U. Casanova E. A. Cinelli P. (2011). The role of the leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) — pathway in derivation and maintenance of murine pluripotent stem cells. Genes.2 (1), 280–297. 10.3390/genes2010280

55

Groenen M. A. M. Archibald A. L. Uenishi H. Tuggle C. K. Takeuchi Y. Rothschild M. F. et al (2012). Analyses of pig genomes provide insight into porcine demography and evolution. Nature491 (7424), 393–398. 10.1038/nature11622

56

Gu M. Nguyen P. K. Lee A. S. Xu D. Hu S. Plews J. R. et al (2012). Microfluidic single-cell analysis shows that porcine induced pluripotent stem cell-derived endothelial cells improve myocardial function by paracrine activation. Circulation Res.111 (7), 882–893. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.269001

57

Gu Qi Jie H. Tang H. Wang J. Jia Y. Kong Q. et al (2014). Efficient generation of mouse ESCs-like pig induced pluripotent stem cells. Protein & Cell.5 (5), 338–342. 10.1007/s13238-014-0043-2

58

Guo S. Zi X. Schulz V. P. Cheng J. Zhong M. Koochaki S. H. J. et al (2014). Nonstochastic reprogramming from a privileged somatic cell state. Cell.156 (4), 649–662. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.020

59

Guo Yu Zhu H. Wang Y. Sun T. Xu J. Wang T. et al (2023). Miniature-swine iPSC-derived GABA progenitor cells function in a rat Parkinson’s disease model. Cell. Tissue Res.391 (3), 425–440. 10.1007/s00441-022-03736-4

60

Habekost M. Lund Jørgensen A. Qvist P. Denham M. (2019). Transcriptomic profiling of porcine pluripotency identifies species-specific reprogramming requirements for culturing iPSCs. Stem Cell. Res.41 (December), 101645. 10.1016/j.scr.2019.101645

61

Hall J. Guo Ge Wray J. Eyres I. Nichols J. Grotewold L. et al (2009). Oct4 and LIF/Stat3 additively induce krüppel factors to sustain embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Cell. Stem Cell.5 (6), 597–609. 10.1016/j.stem.2009.11.003

62

Hall V. J. (2013). Early development of the porcine embryo: the importance of cell signalling in development of pluripotent cell lines. Reproduction, Fertil. Dev.25 (1), 94–102. 10.1071/RD12264

63

Hall V. J. Hyttel P. (2014). Breaking down pluripotency in the porcine embryo reveals both a premature and reticent stem cell state in the inner cell mass and unique expression profiles of the naive and primed stem cell states. Stem Cells Dev.23 (17), 2030–2045. 10.1089/scd.2013.0502

64

Hall V. J. Kristensen M. Rasmussen M. A. Ujhelly O. Dinnyés A. Hyttel P. (2012). Temporal repression of endogenous pluripotency genes during reprogramming of porcine induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell. Reprogr.14 (3), 204–216. 10.1089/cell.2011.0089

65

Hamanaka S. Yamaguchi T. Kobayashi T. Kato-Itoh M. Yamazaki S. Sato H. et al (2011). “Generation of germline-competent rat induced pluripotent stem cells,”. Editor HenriqueD., 6. 10.1371/journal.pone.0022008

66

Hammer R. E. Pursel V. G. Rexroad C. E. Wall R. J. Bolt D. J. Ebert K. M. et al (1985). Production of transgenic rabbits, sheep and pigs by microinjection. Nature315 (6021), 680–683. 10.1038/315680a0

67

Han J. Miao Y.-L. Hua J. Li Y. Zhang X. Zhou J. et al (2019). Porcine pluripotent stem cells: progress, challenges and prospects. Front. Agric. Sci. Eng.6 (1), 8–27. 10.15302/J-FASE-2018233

68

Heng B. C. Liu H. Cao T. (2004). FEEDER CELL DENSITY—A KEY PARAMETER IN HUMAN EMBRYONIC STEM CELL CULTURE. Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. - Animal40 (8), 255–257. 10.1290/0407052.1

69

Henze L. J. Koehl N. J. O’Shea J. P. Kostewicz E. S. Holm R. Griffin B. T. (2019). The pig as a preclinical model for predicting oral bioavailability and in vivo performance of pharmaceutical oral dosage forms: a pearrl review. J. Pharm. Pharmacol.71 (4), 581–602. 10.1111/jphp.12912

70

Hochereau-de Reviers M. T. Perreau C. (1993). In vitro culture of embryonic disc cells from porcine blastocysts. Reprod. Nutr. Dev.33 (5), 475–483. 10.1051/rnd:19930508

71

Hou D.-R. Jin Y. Nie X.-W. Zhang M.-L. Ta Na Zhao L.-H. et al (2016). Derivation of porcine embryonic stem-like cells from in vitro-Produced blastocyst-stage embryos. Sci. Rep.6 (May), 25838. 10.1038/srep25838

72

Howden S. E. Maufort J. P. Duffin B. M. Elefanty A. G. Stanley E. G. Thomson J. A. (2015). Simultaneous reprogramming and gene correction of patient fibroblasts. Stem Cell. Rep.5 (6), 1109–1118. 10.1016/j.stemcr.2015.10.009

73

Hryhorowicz M. Zeyland J. Słomski R. Lipiński D. (2017). Genetically modified pigs as organ donors for xenotransplantation. Mol. Biotechnol.59 (9–10), 435–444. 10.1007/s12033-017-0024-9

74

Hussein S. M. I. Puri M. C. Tonge P. D. Benevento M. Corso A. J. Clancy J. L. et al (2014). Genome-wide characterization of the routes to pluripotency. Nature516 (7530), 198–206. 10.1038/nature14046

75

Jeon S.-B. Seo B.-G. Baek S.-Ki Lee H.-G. Shin J.-H. Lee I.-W. et al (2021). Endothelial cells differentiated from porcine epiblast stem cells. Cell. Reprogr.23 (2), 89–98. 10.1089/cell.2020.0088

76

Jiang A. Ma Y. Zhang X. Pan Q. Luo P. Guo H. et al (2022). The defects of epigenetic reprogramming in dox-dependent porcine-iPSCs. Int. J. Mol. Sci.23 (19), 11941. 10.3390/ijms231911941

77

Jiao H. Lee M.-S. Sivapatham A. Leiferman E. M. Li W.-Ju (2022). Epigenetic regulation of BAF60A determines efficiency of miniature swine iPSC generation. Sci. Rep.12 (1), 9039. 10.1038/s41598-022-12919-6

78

Juhasova J. Juhas S. Hruska-Plochan M. Dolezalova D. Holubova M. Strnadel J. et al (2015). Time course of spinal doublecortin expression in developing rat and porcine spinal cord: implication in in vivo neural precursor grafting studies. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol.35 (1), 57–70. 10.1007/s10571-014-0145-7

79

Kang L. Wang J. Zhang Yu Kou Z. Gao S. (2009). iPS cells can support full-term development of tetraploid blastocyst-complemented embryos. Cell. Stem Cell.5 (2), 135–138. 10.1016/j.stem.2009.07.001

80

Kang X. Yu Q. Huang Y. Song B. Chen Y. Gao X. et al (2015). Effects of integrating and non-integrating reprogramming methods on copy number variation and genomic stability of human induced pluripotent stem cells. PLOS ONE10 (7), e0131128. 10.1371/journal.pone.0131128

81

Kim H. B. Jung S. Park H. Sim D. S. Kim M. Das S. et al (2021). Customized 3D-printed occluders enabling the reproduction of consistent and stable heart failure in swine models. Bio-Design Manuf.4 (4), 833–841. 10.1007/s42242-021-00145-4

82

Kinoshita M. Kobayashi T. Planells B. Klisch D. Spindlow D. Masaki H. et al (2021). Pluripotent stem cells related to embryonic disc exhibit common self-renewal requirements in diverse livestock species. Development148 (23), dev199901. 10.1242/dev.199901

83

Koh S. Piedrahita J. A. (2014). From ‘ES-like’ cells to induced pluripotent stem cells: a historical perspective in domestic animals. Theriogenology81 (1), 103–111. 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2013.09.009

84

Kues W. A. Herrmann D. Barg-Kues B. Haridoss S. Nowak-Imialek M. Buchholz T. et al (2013). Derivation and characterization of sleeping beauty transposon-mediated porcine induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells Dev.22 (1), 124–135. 10.1089/scd.2012.0382

85

Kuo C.-H. Jia H. D. Deng Q. Ying S.-Y. (2012). A novel role of miR-302/367 in reprogramming. Biochem. Biophysical Res. Commun.417 (1), 11–16. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.11.058

86

Kwon D.-J. Hwang I.-S. Kwak T.-Uk Yang H. Park M.-R. Ock S.-A. et al (2017). Effects of cell cycle regulators on the cell cycle synchronization of porcine induced pluripotent stem cells. Dev. Reproduction21 (1), 47–54. 10.12717/DR.2017.21.1.047

87

Kwon D.-J. Jeon H. Oh K. B. Ock S.-A. Im G.-S. Lee S.-S. et al (2013). Generation of leukemia inhibitory factor-dependent induced pluripotent stem cells from the Massachusetts general hospital miniature pig. BioMed Res. Int.2013, 140639. 10.1155/2013/140639

88

Lamming G. E. (1993). Marshall’s physiology of reproduction: volume 3 pregnancy and lactation. Dordrecht, NETHERLANDS, THE: Springer Netherlands. Available at: http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ucalgary-ebooks/detail.action?docID=3566162.

89

Lázaro J. Costanzo M. Sanaki-Matsumiya M. Girardot C. Hayashi M. Hayashi K. et al (2023). A stem cell zoo uncovers intracellular scaling of developmental tempo across mammals. Cell. Stem Cell.30 (7), 938–949.e7. 10.1016/j.stem.2023.05.014

90

Lee S.-E. Hyun H. Park M.-R. Choi Y. Son Y.-J. Park Y.-G. et al (2017). “Production of transgenic pig as an alzheimer’s disease model using a multi-cistronic vector system,”. Editor MadepalliK. L., 12. 10.1371/journal.pone.0177933

91

Li C. Li J. Lai L. Li S. Yan S. (2022). Genetically engineered pig models of neurological diseases. Ageing Neurodegener. Dis.2 (3), 13. 10.20517/and.2022.13

92

Li D. Jan S. Hyttel P. Ivask M. Kolko M. Hall V. J. et al (2018). Generation of transgene-free porcine intermediate type induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell. Cycle17 (23), 2547–2563. 10.1080/15384101.2018.1548790

93

Li M. Wang D. Fang J. Lei Q. Yan Q. Zhou J. et al (2022). An efficient and economical way to obtain porcine muscle stem cells for cultured meat production. Food Res. Int.162 (December), 112206. 10.1016/j.foodres.2022.112206

94

Li M. Zhang D. Hou Yi Jiao L. Xing Z. Wang W.-H. (2003). Isolation and culture of embryonic stem cells from porcine blastocysts. Mol. Reproduction Dev.65 (4), 429–434. 10.1002/mrd.10301

95

Li P. Tong C. Mehrian-Shai R. Jia Li Wu N. Yan Y. et al (2008). Germline competent embryonic stem cells derived from rat blastocysts. Cell.135 (7), 1299–1310. 10.1016/j.cell.2008.12.006

96

Li X. Shan Z.-Y. Wu Y.-S. Shen X.-H. Liu C.-J. Shen J.-L. et al (2014). Generation of neural progenitors from induced bama miniature pig pluripotent cells. Reprod. Camb. Engl.147 (1), 65–72. 10.1530/REP-13-0196

97

Li X. Yang Yu Wei R. Li Y. Lv J. Liu Z. et al (2021). In vitro and in vivo study on angiogenesis of porcine induced pluripotent stem cell-derived endothelial cells. Differ. Res. Biol. Divers.120, 10–18. 10.1016/j.diff.2021.05.003

98

Li X. Zhang F. Song G. Gu W. Chen M. Yang B. et al (2013). “Intramyocardial injection of pig pluripotent stem cells improves left ventricular function and perfusion: a study in a porcine model of acute myocardial infarction,”. Editor ProsperF., 8. 10.1371/journal.pone.0066688

99

Li Z. Duan X. An X. Feng T. Li P. Li L. et al (2018). Efficient RNA-guided base editing for disease modeling in pigs. Cell. Discov.4 (1), 64. 10.1038/s41421-018-0065-7

100

Liao Y.-J. (2014). Establishment and characterization of novel porcine induced pluripotent stem cells expressing hrGFP. J. Stem Cell. Res. Ther.04 (05). 10.4172/2157-7633.1000208

101

Liao Y.-J. Liao C.-H. Chen L.-R. Yang J.-R. (2023). Dopaminergic neurons derived from porcine induced pluripotent stem cell like cells function in the lanyu pig model of Parkinson’s disease. Anim. Biotechnol.34 (4), 1283–1294. 10.1080/10495398.2021.2020130

102

Liao Y.-J. Tang P.-C. Chen Y.-H. Chu F.-H. Kang T.-C. Chen L.-R. et al (2018). Porcine induced pluripotent stem cell-derived osteoblast-like cells prevent glucocorticoid-induced bone loss in lanyu pigs. PloS One13 (8), e0202155. 10.1371/journal.pone.0202155

103

Liu K. Ji G. Mao J. Liu M. Wang L. Chen C. et al (2012). Generation of porcine-induced pluripotent stem cells by using OCT4 and KLF4 porcine factors. Cell. Reprogr.14 (6), 505–513. 10.1089/cell.2012.0047

104

Liu L. Oura S. Markham Z. Hamilton J. N. Skory R. M. Li L. et al (2023). Modeling post-implantation stages of human development into early organogenesis with stem-cell-derived peri-gastruloids. Cell.186 (18), 3776–3792.e16. 10.1016/j.cell.2023.07.018

105

Liu X. Jia P. T. Schröder J. Aberkane A. Ouyang J. F. Mohenska M. et al (2021). Modelling human blastocysts by reprogramming fibroblasts into iBlastoids. Nature591 (7851), 627–632. 10.1038/s41586-021-03372-y

106

Liu Y. Ma Y. Yang J.-Y. Cheng De Liu X. Ma X. et al (2014). Comparative gene expression signature of pig, human and mouse induced pluripotent stem cell lines reveals insight into pig pluripotency gene networks. Stem Cell. Rev. Rep.10 (2), 162–176. 10.1007/s12015-013-9485-9

107

Liu Y. Yang J. Y. Lu Y. Yu P. Dove C. R. Hutcheson J. M. et al (2013). α-1,3-Galactosyltransferase knockout pig induced pluripotent stem cells: a cell source for the production of xenotransplant pigs. Cell. Reprogr.15 (2), 107–116. 10.1089/cell.2012.0062

108

Locke J. E. Kumar V. Anderson D. Porrett P. M. (2023). Normal graft function after pig-to-human kidney xenotransplant. JAMA Surg.158 (10), 1106–1108. 10.1001/jamasurg.2023.2774

109

Lossi L. D’Angelo L. De Girolamo P. Merighi A. (2016). Anatomical features for an adequate choice of experimental animal model in biomedicine: II. Small laboratory rodents, rabbit, and pig. Ann. Anat. - Anatomischer Anzeiger204 (March), 11–28. 10.1016/j.aanat.2015.10.002

110

Loupy A. Goutaudier V. Giarraputo A. Mezine F. Morgand E. Robin B. et al (2023). Immune response after pig-to-human kidney xenotransplantation: a multimodal phenotyping study. Lancet402 (10408), 1158–1169. 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)01349-1

111

Lu T. Yang B. Wang R. Qin C. (2020). Xenotransplantation: current status in preclinical research. Front. Immunol.10 (January), 3060. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.03060

112

Lunney J. K. Van Goor A. Walker K. E. Hailstock T. Franklin J. Dai C. (2021). Importance of the pig as a human biomedical model. Sci. Transl. Med.13 (621), eabd5758. 10.1126/scitranslmed.abd5758

113

Luo Y. Li J. Liu Y. Lin L. Du Y. Li S. et al (2011). High efficiency of BRCA1 knockout using rAAV-mediated gene targeting: developing a pig model for breast cancer. Transgenic Res.20 (5), 975–988. 10.1007/s11248-010-9472-8

114

Ma K. Song G. An X. Fan A. Tan W. Tang Bo et al (2014). miRNAs promote generation of porcine-induced pluripotent stem cells. Mol. Cell. Biochem.389 (1–2), 209–218. 10.1007/s11010-013-1942-x

115

Ma Y. Tong Yu Cai Y. Wang H. (2018). Preserving self-renewal of porcine pluripotent stem cells in serum-free 3i culture condition and independent of LIF and b-FGF cytokines. Cell. Death Discov.4 (December), 21. 10.1038/s41420-017-0015-4

116

MacCarthy C. M. Wu G. Malik V. Menuchin-Lasowski Y. Velychko T. Keshet G. et al (2024). Highly cooperative chimeric super-SOX induces naive pluripotency across species. Cell. Stem Cell.31 (1), 127–147.e9. 10.1016/j.stem.2023.11.010

117

Machado L. S. Pieri N. C. G. Botigelli R. C. Guimarães de Castro R. V. Fernanda de Souza A. Bridi A. et al (2020). Generation of neural progenitor cells from porcine-induced pluripotent stem cells. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med.14 (12), 1880–1891. 10.1002/term.3143

118

Malaver-Ortega, Luis Fernando Sumer H. Liu J. Verma P. J. (2012). The state of the art for pluripotent stem cells derivation in domestic ungulates. Theriogenology78 (8), 1749–1762. 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2012.03.031

119

Mallon B. S. Park K.-Y. Chen K. G. Hamilton R. S. McKay R. D. G. (2006). Toward xeno-free culture of human embryonic stem cells. Int. J. Biochem. Cell. Biol.38 (7), 1063–1075. 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.12.014

120

Mao J. Zhang Q. Deng W. Wang H. Liu K. Fu H. et al (2017). Epigenetic modifiers facilitate induction and pluripotency of porcine iPSCs. Stem Cell. Rep.8 (1), 11–20. 10.1016/j.stemcr.2016.11.013

121

Martin G. R. (1981). Isolation of a pluripotent cell line from early mouse embryos cultured in medium conditioned by teratocarcinoma stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.78 (12), 7634–7638. 10.1073/pnas.78.12.7634

122

Martínez-Falguera D. Iborra-Egea O. Gálvez-Montón C. (2021). iPSC therapy for myocardial infarction in large animal models: land of hope and dreams. Biomedicines9 (12), 1836. 10.3390/biomedicines9121836

123

Maynard L. H. Humbert O. Peterson C. W. Kiem H.-P. (2021). Genome editing in large animal models. Mol. Ther.29 (11), 3140–3152. 10.1016/j.ymthe.2021.09.026

124

Moazami N. Stern J. M. Khalil K. Kim J. I. Narula N. Mangiola M. et al (2023). Pig-to-Human heart xenotransplantation in two recently deceased human recipients. Nat. Med.29 (8), 1989–1997. 10.1038/s41591-023-02471-9

125

Montserrat N. Bahima E. G. Batlle L. Häfner S. Rodrigues A. M. C. González F. et al (2011). Generation of pig iPS cells: a model for cell therapy. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res.4 (2), 121–130. 10.1007/s12265-010-9233-3

126

Montserrat N. de Oñate L. Garreta E. González F. Adamo A. Eguizábal C. et al (2012). Generation of feeder-free pig induced pluripotent stem cells without Pou5f1. Cell. Transplant.21 (5), 815–825. 10.3727/096368911X601019

127

Nagy A. Rossant J. Nagy R. Abramow-Newerly W. Roder J. C. (1993). Derivation of completely cell culture-derived mice from early-passage embryonic stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.90 (18), 8424–8428. 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8424

128

Neagu A. Van Genderen E. Escudero I. Verwegen L. Kurek D. Lehmann J. et al (2020). In vitro capture and characterization of embryonic rosette-stage pluripotency between naive and primed states. Nat. Cell. Biol.22 (5), 534–545. 10.1038/s41556-020-0508-x

129

Nichols J. Silva J. Roode M. Smith A. (2009). Suppression of erk signalling promotes ground state pluripotency in the mouse embryo. Development136 (19), 3215–3222. 10.1242/dev.038893

130

Nichols J. Smith A. (2009). Naive and primed pluripotent states. Cell. Stem Cell.4 (6), 487–492. 10.1016/j.stem.2009.05.015

131

Niemann H. (2019). “Pigs as model systems for biomedical research,” in Bioscientifica proceedings. 10.1530/biosciprocs.19.0029

132

Okita K. Ichisaka T. Yamanaka S. (2007). Generation of germline-competent induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature448 (7151), 313–317. 10.1038/nature05934

133

Oldak B. Wildschutz E. Bondarenko V. Comar M.-Y. Zhao C. Aguilera-Castrejon A. et al (2023). Complete human day 14 post-implantation embryo models from naive ES cells. Nature622 (7983), 562–573. 10.1038/s41586-023-06604-5

134

Pabst R. (2020). The pig as a model for immunology research. Cell. Tissue Res.380 (2), 287–304. 10.1007/s00441-020-03206-9

135

Pan G. Thomson J. A. (2007). Nanog and transcriptional networks in embryonic stem cell pluripotency. Cell. Res.17 (1), 42–49. 10.1038/sj.cr.7310125

136

Pan Z. Yao Y. Yin H. Cai Z. Wang Y. Bai L. et al (2021). Pig genome functional annotation enhances the biological interpretation of complex traits and human disease. Nat. Commun.12 (1), 5848. 10.1038/s41467-021-26153-7

137

Paria B. C. Huet-Hudson Y. M. Dey S. K. (1993). Blastocyst’s state of activity determines the ‘window’ of implantation in the receptive mouse uterus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.90 (21), 10159–10162. 10.1073/pnas.90.21.10159

138

Park J.-K. Kim H.-S. Uh K.-J. Choi K.-H. Kim H.-M. Lee T. et al (2013). Primed pluripotent cell lines derived from various embryonic origins and somatic cells in pig. PLOS ONE8 (1), e52481. 10.1371/journal.pone.0052481

139

Park K.-M. Cha S.-Ho Ahn C. Woo H.-M. (2013). Generation of porcine induced pluripotent stem cells and evaluation of their major histocompatibility complex protein expression in vitro. Veterinary Res. Commun.37 (4), 293–301. 10.1007/s11259-013-9574-x

140

Park K.-M. Hussein K. H. Hong S.-Ho Ahn C. Yang S.-R. Park S.-M. et al (2016). Decellularized liver extracellular matrix as promising tools for transplantable bioengineered liver promotes hepatic lineage commitments of induced pluripotent stem cells. Tissue Eng.22 (5–6), 449–460. 10.1089/ten.TEA.2015.0313

141

Park K.-M. Lee J. Hussein K. H. Hong S.-Ho Yang S.-R. Lee E. et al (2016). Generation of liver-specific TGF-α/c-myc-overexpressing porcine induced pluripotent stem-like cells and blastocyst formation using nuclear transfer. J. Veterinary Med. Sci.78 (4), 709–713. 10.1292/jvms.15-0363

142

Perleberg C. Kind A. Schnieke A. (2018). Genetically engineered pigs as models for human disease. Dis. Models Mech.11 (1), dmm030783. 10.1242/dmm.030783

143

Perry J. S. Rowlands I. W. (1962). EARLY PREGNANCY IN THE PIG. Reproduction4 (2), 175–188. 10.1530/jrf.0.0040175

144

Petkov S. Glage S. Nowak-Imialek M. Niemann H. (2016). Long-term culture of porcine induced pluripotent stem-like cells under feeder-free conditions in the presence of histone deacetylase inhibitors. Stem Cells Dev.25 (5), 386–394. 10.1089/scd.2015.0317

145

Petkov S. Hyttel P. Niemann H. (2013). The choice of expression vector promoter is an important factor in the reprogramming of porcine fibroblasts into induced pluripotent cells. Cell. Reprogr.15 (1), 1–8. 10.1089/cell.2012.0053

146

Petkov S. Hyttel P. Niemann H. (2014). The small molecule inhibitors PD0325091 and CHIR99021 reduce expression of pluripotency-related genes in putative porcine induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell. Reprogr.16 (4), 235–240. 10.1089/cell.2014.0010

147

Pieri N. C. G. Fernanda de Souza A. Cesar Botigelli R. de Figueiredo Pessôa L. V. Recchia K. Machado L. S. et al (2022). Porcine primordial germ cell-like cells generated from induced pluripotent stem cells under different culture conditions. Stem Cell. Rev. Rep.18 (5), 1639–1656. 10.1007/s12015-021-10198-8

148

Plath K. Lowry W. E. (2011). Progress in understanding reprogramming to the induced pluripotent state. Nat. Rev. Genet.12 (4), 253–265. 10.1038/nrg2955

149

Porrett P. M. Orandi B. J. Kumar V. Houp J. Anderson D. Cozette Killian A. et al (2022). First clinical-grade porcine kidney xenotransplant using a human decedent model. Am. J. Transplant.22 (4), 1037–1053. 10.1111/ajt.16930

150

Posfai E. Paul Schell J. Janiszewski A. Rovic I. Murray A. Bradshaw B. et al (2021). Evaluating totipotency using criteria of increasing stringency. Nat. Cell. Biol.23 (1), 49–60. 10.1038/s41556-020-00609-2

151

Post M. J. Levenberg S. Kaplan D. L. Genovese N. Fu J. Bryant C. J. et al (2020). Scientific, sustainability and regulatory challenges of cultured meat. Nat. Food1 (7), 403–415. 10.1038/s43016-020-0112-z

152

Prigione A. Hossini A. M. Lichtner B. Serin A. Fauler B. Megges M. et al (2011). “Mitochondrial-associated cell death mechanisms are reset to an embryonic-like state in aged donor-derived iPS cells harboring chromosomal aberrations,”. Editor MarkP. M., 6. 10.1371/journal.pone.0027352

153

Rayon T. Stamataki D. Perez-Carrasco R. Garcia-Perez L. Barrington C. Melchionda M. et al (2020). Species-specific pace of development is associated with differences in protein stability. Science369 (6510), eaba7667. 10.1126/science.aba7667

154

Recchia K. Machado L. S. Botigelli R. C. Pieri N. C. G. Barbosa G. de Castro R. V. G. et al (2022). In vitro induced pluripotency from urine-derived cells in porcine. World J. Stem Cells14 (3), 231–244. 10.4252/wjsc.v14.i3.231

155

Ren X. Xu J. Xue Q. Tong Yi Xu T. Wang J. et al (2024). BRG1 enhances porcine iPSC pluripotency through WNT/β-Catenin and autophagy pathways. Theriogenology215 (February), 10–23. 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2023.11.014

156

Rodríguez A. Allegrucci C. Alberio R. (2012). Modulation of pluripotency in the porcine embryo and iPS cells. PloS One7 (11), e49079. 10.1371/journal.pone.0049079

157

Rouselle S. D. Dillon K. N. Rousselle-Sabiac T. H. Brady D. A. Tunev S. Tellez A. (2016). Historical incidence of spontaneous lesions in kidneys from naïve swine utilized in interventional renal denervation studies. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res.9 (4), 360–367. 10.1007/s12265-016-9697-x

158

Ruan W. M. Han J. Y. Li P. Cao S. Y. Yang An Lim B. et al (2011). A novel strategy to derive iPS cells from porcine fibroblasts. Sci. China. Life Sci.54 (6), 553–559. 10.1007/s11427-011-4179-5

159

Ruiz S. Panopoulos A. D. Herrerías A. Bissig K.-D. Lutz M. Travis Berggren W. et al (2011). A high proliferation rate is required for cell reprogramming and maintenance of human embryonic stem cell identity. Curr. Biol.21 (1), 45–52. 10.1016/j.cub.2010.11.049

160

Sasaki N. Okishio K. Ui-Tei K. Saigo K. Kinoshita-Toyoda A. Toyoda H. et al (2008). Heparan sulfate regulates self-renewal and pluripotency of embryonic stem cells. J. Biol. Chem.283 (6), 3594–3606. 10.1074/jbc.M705621200

161

Schomberg D. T. Miranpuri G. S. Chopra A. Patel K. Meudt J. J. Tellez A. et al (2017). Translational relevance of swine models of spinal cord injury. J. Neurotrauma34 (3), 541–551. 10.1089/neu.2016.4567

162

Schook L. B. Collares T. V. Darfour-Oduro K. A. Kumar De A. Rund L. A. Schachtschneider K. M. et al (2015). Unraveling the swine genome: implications for human health. Annu. Rev. Animal Biosci.3 (1), 219–244. 10.1146/annurev-animal-022114-110815

163

Secher J. Freude K. Petkov S. Ceylan A. Schmidt M. Hyttel P. (2015). 326 ASSESSMENT OF PORCINE-INDUCED PLURIPOTENT STEM CELLS BY in vivo ASSAYS. Reproduction, Fertil. Dev.27 (1), 252. 10.1071/RDv27n1Ab326

164

Secher J. O. Ceylan A. Mazzoni G. Mashayekhi K. Tong Li Muenthaisong S. et al (2017). Systematic in vitro and in vivo characterization of leukemia-inhibiting factor- and fibroblast growth factor-derived porcine induced pluripotent stem cells. Mol. Reproduction Dev.84 (3), 229–245. 10.1002/mrd.22771

165

Setthawong P. Phakdeedindan P. Techakumphu M. Tharasanit T. (2021). Molecular signature and colony morphology affect in vitro pluripotency of porcine induced pluripotent stem cells. Reproduction Domest. Animals = Zuchthygiene56 (8), 1104–1116. 10.1111/rda.13954

166

Setthawong P. Phakdeedindan P. Tiptanavattana N. Rungarunlert S. Techakumphu M. Tharasanit T. (2019). Generation of porcine induced-pluripotent stem cells from sertoli cells. Theriogenology127 (March), 32–40. 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2018.12.033

167

Shahbazi M. N. Scialdone A. Skorupska N. Weberling A. Recher G. Zhu M. et al (2017). Pluripotent state transitions coordinate morphogenesis in mouse and human embryos. Nature552 (7684), 239–243. 10.1038/nature24675

168

Shen Q. Wu X. Chen Z. Guo J. Yue W. Yu S. et al (2024). TBX3 orchestrates H3K4 trimethylation for porcine induced pluripotent stem cells to totipotent-like stem Cells1. J. Integr. Agric., S2095311924000534. 10.1016/j.jia.2024.02.007

169

Shen Q.-Y. Yu S. Zhang Y. Zhou Z. Zhu Z.-S. Pan Q. et al (2019). Characterization of porcine extraembryonic endoderm cells. Cell. Prolif.52 (3), e12591. 10.1111/cpr.12591

170

Shi B. Gao D. Zhong L. Zhi M. Weng X. Xu J. et al (2020). IRF-1 expressed in the inner cell mass of the porcine early blastocyst enhances the pluripotency of induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell. Res. Ther.11 (1), 505. 10.1186/s13287-020-01983-2

171

Silva J. Barrandon O. Nichols J. Kawaguchi J. Theunissen T. W. Smith A. (2008). “Promotion of reprogramming to ground state pluripotency by signal inhibition,”. Editor GoodellM. A., 6, e253. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060253

172

Simpson L. Strange A. Klisch D. Kraunsoe S. Azami T. Goszczynski D. et al (2023). A single-cell atlas of pig gastrulation as a resource for comparative embryology. bioRxiv. 10.1101/2023.08.31.555712

173

Smith A. (2017). Formative pluripotency: the executive phase in a developmental continuum. Development144 (3), 365–373. 10.1242/dev.142679

174

Song W. Liu P. Li H. Ding S. (2022). Large-scale expansion of porcine adipose-derived stem cells based on microcarriers system for cultured meat production. Foods11 (21), 3364. 10.3390/foods11213364

175

Soto D. A. Navarro M. Zheng C. Margaret Halstead M. Zhou C. Guiltinan C. et al (2021). Simplification of culture conditions and feeder-free expansion of bovine embryonic stem cells. Sci. Rep.11 (1), 11045. 10.1038/s41598-021-90422-0

176

Sper R. B. Proctor J. Lascina O. Guo L. Polkoff K. Kaeser T. et al (2022). Allogeneic and xenogeneic lymphoid reconstitution in a RAG2-/-IL2RGy/- severe combined immunodeficient pig: a preclinical model for intrauterine hematopoietic transplantation. Front. Veterinary Sci.9, 965316. 10.3389/fvets.2022.965316

177

Strnadel J. Carromeu C. Bardy C. Navarro M. Platoshyn O. Glud A. N. et al (2018). Survival of syngeneic and allogeneic iPSC-derived neural precursors after spinal grafting in minipigs. Sci. Transl. Med.10 (440), eaam6651. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aam6651

178

Strojek R. M. Reed M. A. Hoover J. L. Wagner T. E. (1990). A method for cultivating morphologically undifferentiated embryonic stem cells from porcine blastocysts. Theriogenology33 (4), 901–913. 10.1016/0093-691x(90)90825-e

179

Takahashi K. Tanabe K. Ohnuki M. Narita M. Ichisaka T. Tomoda K. et al (2007). Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell.131 (5), 861–872. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019

180

Takahashi K. Yamanaka S. (2006). Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell.126 (4), 663–676. 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024

181

Talbot N. C. Le A. B. (2008). The pursuit of ES cell lines of domesticated ungulates. Stem Cell. Rev.4 (3), 235–254. 10.1007/s12015-008-9026-0

182

Tam P. P. Rossant J. (2003). Mouse embryonic chimeras: tools for studying mammalian development. Development130 (25), 6155–6163. 10.1242/dev.00893

183

Tarazi S. Aguilera-Castrejon A. Joubran C. Ghanem N. Ashouokhi S. Roncato F. et al (2022). Post-gastrulation synthetic embryos generated ex utero from mouse naive ESCs. Cell.185 (18), 3290–3306.e25. 10.1016/j.cell.2022.07.028

184