Introduction

As autophagy a highly evolutionary conserved catabolic process, autophagy plays a critical role in maintaining cellular quality control across species, which also links cardiac development to cardiac pathogenesis, from Drosophila to humans. During cardiac organogenesis, autophagy is essential for preserving cardiac homeostasis by eliminating dysfunctional organelles, misfolded proteins, and damaged macromolecules. Genetic manipulation in Drosophila has provided a foundational understanding for the importance of autophagy in cardiac development. Studies in human aging and pathogenic process has also linked this vital cellular process to stress, aging, and metabolic challenges to offer a unifying molecular and cellular framework underlying cardiac pathogenesis.

Insights from Drosophila melanogaster: the genetic foundation of cardiac autophagy

Drosophila have yielded significant cellular and molecular mechanistic insights into the cardioprotective functions of autophagy. In Drosophila, autophagy-related cardiac dysfunction has been closely associated with dysregulation of the mTOR/ULK1 signaling axis. Notably, pharmacological inhibition of mTORC1 reactivates ULK1 to enhance autophagic flux, and ameliorate cardiomyopathic phenotypes observed in Lamin C (LamC) mutants (Demir and Kacew, 2023; Hegedűs et al., 2014; Zhang et al.). These LamC mutants display compromised nuclear envelope integrity and disrupted nuclear–cytoplasmic communication, resulting in proteotoxicity and oxidative stress—classic features of impaired autophagy (Bhide et al., 2018; Chandran et al., 2019; Kirkland et al., 2023; Walker et al., 2023). Mutations affecting nuclear envelope components, such as LamC, interfere with the mTORC1–ULK1 axis, suppressing autophagic activity and leading to cardiac dysfunction. Treatment with rapamycin, an mTORC1 inhibitor, effectively restores autophagic flux and improves cardiac outcomes, underscoring the conserved role of mTOR signaling in cardiac homeostasis.

Crucial core autophagy-related genes Atg1, Atg5, and Atg8 are indispensable for autophagosome formation and normal cardiac function. Upstream metabolic regulators of these genes through the AMPK and the PI3K/Akt pathway modulate mTORC1 activity to influence autophagic flux, linking energy sensing and growth signaling for cardiac maintenance and remodeling (Kirkland et al., 2023; Walker et al., 2023; Pai et al., 2023). These regulatory interactions form part of a broader metabolic network essential for adapting the postnatal heart to physiologic stress. Disturbances in this pathway leads to early postnatal death. Collectively, findings from Drosophila provide a robust genetic and biochemical foundation for understanding evolutionarily conserved autophagy mechanisms contributing to cardiomyocyte resilience in human cardiac disease. This cross-species paradigm reinforces the translational relevance of autophagy as a therapeutic target for mitigating cardiac disease arising from genetic mutations or environmental insults.

Autophagy in viral and inflammatory cardiomyopathy: HIV as a model of immune-metabolic disruption

The pathogenesis of HIV-associated cardiomyopathy (HACM) underscores the detrimental consequences of impaired autophagy in the adult human heart. HIV infection affects chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA) to cause cardiomyopathy in infected patients (collected in this Research Topic, Sun et al.). Dysregulation of CMA—critical for maintaining cardiomyocyte and macrophage mitochondrial integrity and immune homeostasis—leads to the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), activation of the inflammasome, and induction of pyroptosis (Gatica et al., 2022; Avula et al., 2021; Bulló et al., 2021; Morales et al., 2020; Abdel-Rahman et al., 2021; Ning et al., 2023; Li et al., 2022). In HIV infection and exposure to highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), mTOR signaling becomes hyperactivated, thereby downregulating ULK1 (unc-51 like autophagy activating kinase 1), a gene essential to autophagosome biogenesis. Suppression of ULK1 leads to reduced autophagy and further compromising cardiomyocyte survival in the setting of viral or drug injury (Sun et al.; Akbay et al., 2020; Crater et al., 2022; Singh et al., 2022). Pharmacological inhibition of mTORC1 can restore ULK1 activity and reinstate mitochondrial quality control, highlighting a promising therapeutic axis in autophagy-based cardiac interventions.

HIV-associated clonal hematopoiesis (CH)—propelled by somatic mutations in Tet2, Dnmt3a, and Jak2—further exacerbates inflammatory responses through impaired mitophagy and dysregulated macrophage signaling (Dharan et al., 2021; Bick et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2022). The pathological relevance of autophagic disruption in immune-mediated myocardial damage is reinforced by the observation that autophagy inhibition aggravates cardiac inflammation and slows adaptive remodeling. These mutations replicate the dysfunctional immune-metabolic axis previously observed in autophagy-deficient Drosophila models. Thus providing a mechanistic bridge linking immune dysregulation to cardiac injury in human disease. This evolutionary parallel accentuates the conserved role of autophagy in modulating inflammatory and metabolic homeostasis across species.

Autophagy in metabolic stress and cardiac remodeling: maintaining homeostasis in metabolic stress

In models of obesity and diabetes, such as high-fat diet (HFD) combined with streptozotocin (STZ)-induced metabolic cardiomyopathy (MCM), autophagic activity is markedly suppressed due to insulin resistance-mediated hyperactivation of the mTORC1 signaling pathway (collected in this Research Topic, Zhou et al., 2025). This suppression compromises the clearance of dysfunctional mitochondria and promotes lipid overload and oxidative stress—key pathological features characteristic of diabetic heart disease.

Autophagy is a critical adaptive response in HFD/STZ-induced models of MCM that counteracts metabolic stress through multiple regulatory mechanisms. Specifically, autophagy alleviates lipid accumulation, fibrosis, and mitochondrial dysfunction by engaging the AMPK/mTOR/ULK1 and PINK1/Parkin-dependent signaling pathways (Madonna et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2017; Lin et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2022; Elrashidy and Ibrahim, 2021). Selective autophagy processes—including mitophagy (via PINK1/Parkin), lipophagy, and ferritinophagy—play central roles in maintaining mitochondrial integrity, regulating lipid metabolism, and controlling intracellular iron levels. Disruption of these pathways results in lipotoxicity, ferroptosis, and impaired energy metabolism (Li et al., 2025). Both selective and non-selective autophagy work in concert to sustain myocardial homeostasis by clearing cytotoxic byproducts and preserving organelle function. Transcriptional regulators such as FOXO3, BNIP3, and TFEB, along with autophagy-related microRNAs like miR-34a, coordinate the expression of autophagy and lysosome-associated genes (Wang et al., 2021). Genetically engineered disruptions along the AMPK/mTOR/ULK1 and PINK1/Parkin-dependent signaling pathways in Drosophila induces the same autophagy failure and metabolic derangements described in human pathology (Zhang et al.). These findings indicate that these tightly regulated autophagy signaling networks are evolutionarily critical cross species, and that precise modulation of autophagic flux is crucial in the prevention and management of metabolic heart failure.

Macrophage autophagy, clonal hematopoiesis, and inflammatory atherosclerosis: immune crosstalk in human cardiovascular disease

Macrophage autophagy—particularly CMA—plays a pivotal role in regulating lipid metabolism, controlling inflammation, and maintaining mitochondrial function (Li et al., 2025; Duan et al., 2022). Dysfunctional CMA contributes to the formation of foam cells, increased ROS accumulation, and activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, thereby promoting pyroptotic cell death (Nussenzweig et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2022; Díez-Díez et al., 2024; Yunna et al., 2020; Duewell et al., 2010). Deficient CMA impairs cholesterol efflux and facilitates the buildup of lipid droplets by hindering ABCA1-mediated cholesterol transport. This results in degraded lipid droplet-coating proteins such as PLIN2, which reinforces a cycle of vascular lipid overload and inflammation central to development of atherosclerosis.

Clonal hematopoiesis-associated mutations in genes such as Tet2, Jaks, and Dnmt3a have been shown to suppress mitophagy and shift macrophage cytokine profiles toward pro-inflammatory phenotypes (Jaiswal et al., 2017; Fuster et al., 2017; Zhao et al., 2025; Abplanalp et al., 2020). These mutations commonly accumulate in macrophages with age, illustrating how somatic changes in hematopoietic stem cells may affect macrophage function in an age related fashion. This progressive impairment of macrophage autophagic regulation promotes chronic vascular inflammation and senescence-associated atherosclerotic progression to accelerate atherogenesis with age. Importantly, restoration of CMA activity in macrophages—either through LAMP2A overexpression or pharmacological activation—has been shown to attenuate vascular inflammation and enhance plaque stability (Valdor and Martinez-Vicente, 2024; Fernández-Alvira et al., 2017).

Tunneling nanotube (TNT) mediated autophagy in heart development

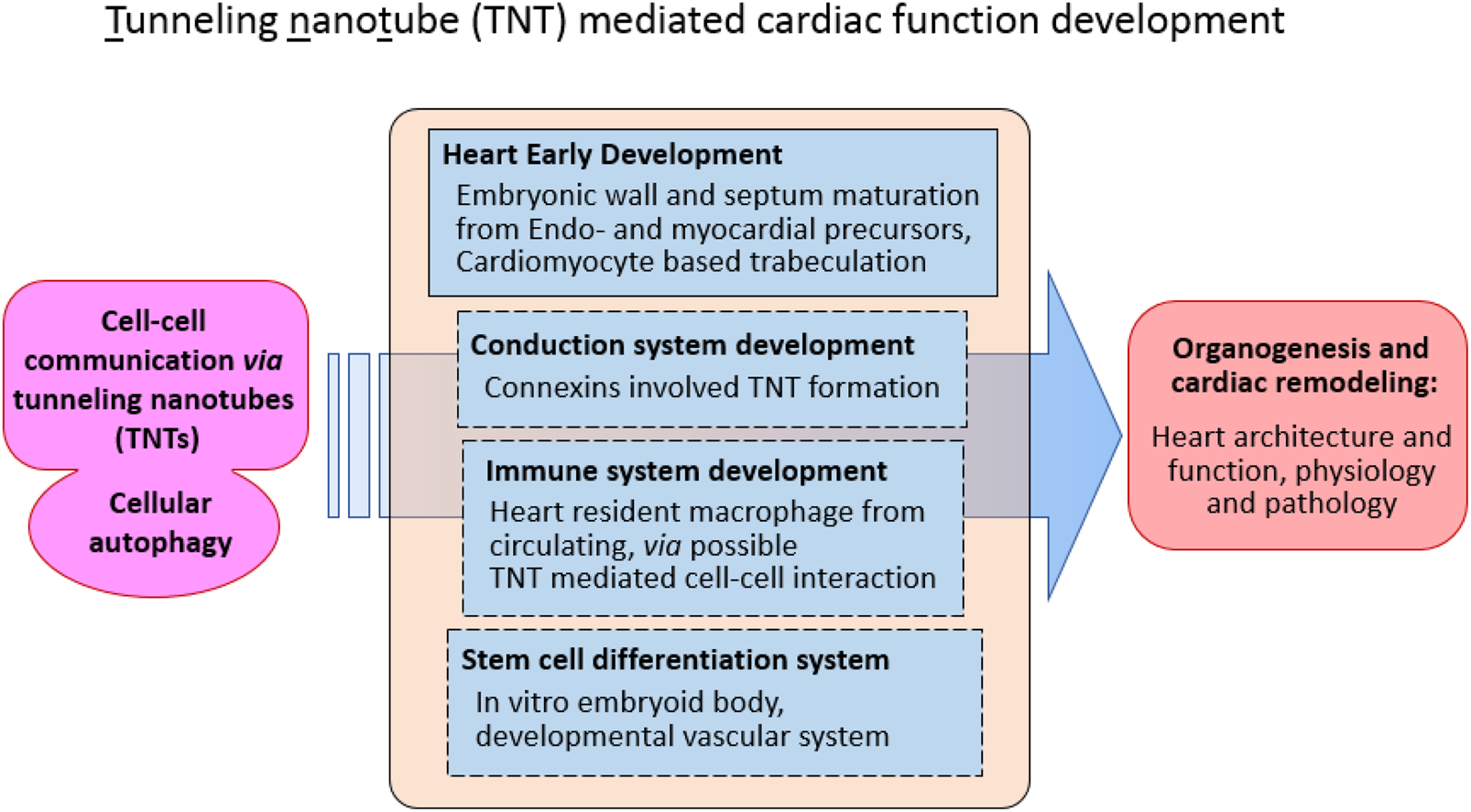

Tunneling nanotubes (TNTs) are well-established intercellular communication structures that play vital roles in a wide range of cellular processes, including signal transduction, metabolic exchange, and immune regulation (Polak et al., 2015; Rustom et al., 2004; Sowinski et al., 2008; Wang and Gerdes, 2015; Rainy et al., 2013; Lou et al., 2012). Originally identified as thin, actin-based cytoplasmic extensions that physically connect distant cells, TNTs have been recognized as essential mediators of direct intercellular communication, enabling the transfer of ions, proteins, RNA, and even organelles between connected cells. Their subsequent discovery within the context of cardiac development introduced a new dimension to the study of these dynamic microstructures (Goodman et al., 2019; Hulsmans et al., 2017; Zhou et al., 2018; Li et al., 2025; Wang et al., 2010; Ariazi et al., 2017). This emerging evidence suggests that TNTs may participate not only in cellular communication during homeostasis but also in orchestrating complex developmental events, such as those underlying heart morphogenesis.

In the developing heart, where multiple cell lineages interact to establish coordinated tissue architecture, the presence of TNT-like structures (TNTLs) offers a compelling explanation for how autophagy—a key intracellular degradation and recycling process—may be integrated into intercellular signaling networks. Autophagy has long been recognized as a mechanism through which cells maintain homeostasis and modulate communication with their neighbors. The potential coupling of TNT-mediated signaling with autophagic activity provides a novel mechanistic framework for understanding cardiac embryogenesis, particularly in regions where cells of dual origin, such as the endocardium and myocardium, interact. Notably, TNTs have been implicated in macrophage-mediated autophagic communication, influencing electrical coupling and metabolic coordination between mature cardiomyocytes (Rustom et al., 2004; de Rooij et al., 2017; Morrison and Scadden, 2014; Polak et al., 2015; Barutta et al., 2023; Ottonelli et al., 2022; Venkatesh and Lou, 2019). These findings collectively underscore the potential for TNTs to serve as structural and functional intermediaries in cardiac tissue organization and homeostasis.

Recent investigations have identified distinct TNT-like structures (TNTLs) within mouse embryonic hearts, further reinforcing their significance in early cardiac morphogenesis (Huynh, 2025; Miao et al., 2025; de la Pompa, J.L., 2025). The authors proposed that TNTLs localized within the cardiac jelly act as direct physical linkages between the endocardium and myocardium, facilitating the bidirectional exchange of signaling molecules and proteins between endocardial cells and cardiomyocytes. Using an in vitro co-culture system combined with fluorescently labeled cytoskeletal polymerization assays, these studies demonstrated that TNTL formation depends primarily on the polymerization of actin filaments rather than microtubule assembly (Miao et al., 2025; de la Pompa, J.L., 2025). This actin-dependent mechanism reflects the dynamic and adaptable nature of TNTLs, aligning with their proposed roles in modulating developmental signaling pathways (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1

Function tunneling nanotube (TNT) in cellular communication during cardiac development.

Collectively, these discoveries provide new insight into how TNT-mediated autophagy and intercellular communication may contribute to cardiac development. By establishing physical and functional connections between endocardial and myocardial cells, TNTLs may help coordinate microstructural interactions and spatial patterning during cardiac trabeculation and ventricular wall formation. Understanding these processes could illuminate a previously underexplored layer of cardiac morphogenesis, offering new perspectives on how cellular connectivity and autophagic signaling jointly regulate the emergence of functional cardiac architecture.

Cardiovascular aging and autophagy modulation via non-coding RNAs: senescence as a new frontier

Aging is the cumulative breakdown of cellular homeostasis. This is true in cardiovascular tissues where impaired autophagy exacerbates mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and proteotoxicity over time. Non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), including microRNAs (miRNAs) and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), has recently been shown to regulate autophagy by modulating key signaling pathways, such as the previously discussed AMPK/mTOR and ULK1 pathways. Dysregulation of these ncRNAs contributes significantly to age-related cardiovascular decline (collected in this Research Topic, Scalabrin and Cagnin). Recent studies reveal that specific ncRNAs can enhance autophagic capacity and reduce markers of cellular senescence in endothelial cells and cardiomyocytes (Yang et al., 2017; Liang et al., 2020; Zhang et al.). From a therapeutic perspective, targeting ncRNAs to restore or optimize autophagic activity presents a promising strategy to delay cardiovascular aging and promote healthy lifespan extension.

Conclusion and perspective

Autophagy is an evolutionarily conserved cellular function essential for life from embryogenesis to death. From the relatively simple heart tube of Drosophila to the anatomically complex four-chambered human heart, autophagy emerges as a central, evolutionarily preserved mechanism orchestrating cardiac development, physiological adaptation, healing, and age-related degeneration. Key molecular regulators of autophagy, such as mTOR, AMPK, ULK1, LAMP2A, and the PINK1/Parkin mitophagy pathway, and components of chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA), are conserved across species and developmental stages. Normal autophagy is essential to normal cardiac development and functional recovery after myocardial injury. Abnormal autophagy has been implicated in the full spectrum of cardiac disease, from inherited genetic structural abnormalities to infectious cardiomyopathies like HIV-associated disease and cardiac disease from metabolic syndrome. The ubiquitousness of autophagy in embryonic development and diseases of pathologic cardiac remodeling represent a potential therapeutic target in which autophagy modulation could improve cardiac disease and recovery.

Statements

Author contributions

QD: Data curation, Methodology, Investigation, Validation, Software, Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft. XX: Supervision, Methodology, Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review and editing, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition. OJ: Formal Analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization, Writing – review and editing. JM: Writing – review and editing. JB: Conceptualization, Writing – review and editing. MX: Investigation, Writing – review and editing, Conceptualization, Supervision, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Data curation, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (#31771377/31571273/31371256), the Foreign Distinguished Scientist Program from the National Department of Education (#MS2014SXSF038), the National Department of Education Central Universities Research Fund (#GK201301001/201701005/GERP-17-45) to XX; DQ, partially supported by the SNNU PhD Postgradational Leadership program (#LHRCCX23196).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Abdel-Rahman E. A. Hosseiny S. Aaliya A. Adel M. Yasseen B. Al-Okda A. et al (2021). Sleep/wake calcium dynamics, respiratory function, and ROS production in cardiac mitochondria. J. Adv. Res.31, 35–47. 10.1016/j.jare.2021.01.006

2

Abplanalp W. T. Mas-Peiro S. Cremer S. John D. Dimmeler S. Zeiher A. M. (2020). Association of clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential with inflammatory gene expression in patients with severe degenerative aortic valve stenosis or chronic postischemic heart failure. JAMA Cardiol.5, 1170–1175. 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.2468

3

Akbay B. Shmakova A. Vassetzky Y. Dokudovskaya S. (2020). Modulation of mTORC1 signaling pathway by HIV-1. Cells9, 1090. 10.3390/cells9051090

4

Ariazi J. Benowitz A. De Biasi V. Den Boer M. L. Cherqui S. Cui H. et al (2017). Tunneling nanotubes and gap junctions-their role in long-range intercellular communication during development, health, and disease conditions. Front. Mol. Neurosci.10, 333. 10.3389/fnmol.2017.00333

5

Avula H. R. Ambrosy A. P. Silverberg M. J. Reynolds K. Towner W. J. Hechter R. C. et al (2021). Human immunodeficiency virus infection and risks of morbidity and death in adults with incident heart failure. Eur. Heart J. Open1, oeab040. 10.1093/ehjopen/oeab040

6

Barutta F. Bellini S. Kimura S. Hase K. Corbetta B. Corbelli A. et al (2023). Protective effect of the tunneling nanotube-TNFAIP2/M-sec system on podocyte autophagy in diabetic nephropathy. Autophagy19, 505–524. 10.1080/15548627.2022.2080382

7

Bhide S. Trujillo A. S. O'Connor M. T. Young G. H. Cryderman D. E. Chandran S. et al (2018). Increasing autophagy and blocking Nrf2 suppress laminopathy-induced age-dependent cardiac dysfunction and shortened lifespan. Aging Cell17, e12747. 10.1111/acel.12747

8

Bick A. G. Popadin K. Thorball C. W. Uddin M. M. Zanni M. V. Yu B. et al (2022). Increased prevalence of clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential amongst people living with HIV. Sci. Rep.12, 577. 10.1038/s41598-021-04308-2

9

Bulló M. Papandreou C. García-Gavilán J. Ruiz-Canela M. Li J. Guasch-Ferré M. et al (2021). Tricarboxylic acid cycle related-metabolites and risk of atrial fibrillation and heart failure. Metab. Metab.125, 154915. 10.1016/j.metabol.2021.154915

10

Chandran S. Suggs J. A. Wang B. J. Han A. Bhide S. Cryderman D. E. et al (2019). Suppression of myopathic lamin mutations by muscle-specific activation of AMPK and modulation of downstream signaling. Hum. Mol. Genet.28, 351–371. 10.1093/hmg/ddy332

11

Crater J. M. Nixon D. F. Furler O’Brien R. L. (2022). HIV-1 replication and latency are balanced by mTOR-driven cell metabolism. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol.12, 1068436. 10.3389/fcimb.2022.1068436

12

de la Pompa J. L. (2025). Tunneling through cardiac jelly. Science387 (6739), 1151–1152. 10.1126/science.adw1567

13

de Rooij B. Polak R. Stalpers F. Pieters R. den Boer M. L. (2017). Tunneling nanotubes facilitate autophagosome transfer in the leukemic niche. Leukemia31, 1651–1654. 10.1038/leu.2017.117

14

Demir E. Kacew S. (2023). Drosophila as a robust model system for assessing autophagy: a review. Toxics11, 682. 10.3390/toxics11080682

15

Dharan N. J. Yeh P. Bloch M. Yeung M. M. Baker D. Guinto J. et al (2021). HIV is associated with an increased risk of age-related clonal hematopoiesis among older adults. Nat. Med.27, 1006–1011. 10.1038/s41591-021-01357-y

16

Díez-Díez M. Ramos-Neble B. L. de la Barrera J. Silla-Castro J. C. Quintas A. Vázquez E. et al (2024). Unidirectional association of clonal hematopoiesis with atherosclerosis development. Nat. Med.30, 2857–2866. 10.1038/s41591-024-03213-1

17

Duan Q. Gao Y. Cao X. Wang S. Xu M. Jones O. D. et al (2022). Mosaic loss of chromosome Y in peripheral blood cells is associated with age-related macular degeneration in men. Cell Biosci.12, 73. 10.1186/s13578-022-00811-9

18

Duewell P. Kono H. Rayner K. J. Sirois C. M. Vladimer G. Bauernfeind F. G. et al (2010). NLRP3 inflammasomes are required for atherogenesis and activated by cholesterol crystals. Nature464, 1357–1361. 10.1038/nature08938

19

Elrashidy R. A. Ibrahim S. E. (2021). Cinacalcet as a surrogate therapy for diabetic cardiomyopathy in rats through AMPK-mediated promotion of mitochondrial and autophagic function. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol.421, 115533. 10.1016/j.taap.2021.115533

20

Fernández-Alvira J. M. Fuster V. Pocock S. Sanz J. Fernández-Friera L. Laclaustra M. et al (2017). Predicting subclinical atherosclerosis in low-risk individuals: ideal cardiovascular health score and fuster-BEWAT score. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol.70, 2463–2473. 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.09.032

21

Fuster J. J. MacLauchlan S. Zuriaga M. A. Polackal M. N. Ostriker A. C. Chakraborty R. et al (2017). Clonal hematopoiesis associated with TET2 deficiency accelerates atherosclerosis development in mice. Science355, 842–847. 10.1126/science.aag1381

22

Gatica D. Chiong M. Lavandero S. Klionsky D. J. (2022). The role of autophagy in cardiovascular pathology. Cardiovasc Res.118, 934–950. 10.1093/cvr/cvab158

23

Goodman S. Naphade S. Khan M. Sharma J. Cherqui S. (2019). Macrophage polarization impacts tunneling nanotube formation and intercellular organelle trafficking. Sci. Rep.9, 14529. 10.1038/s41598-019-50971-x

24

Hegedűs K. Nagy P. Gáspári Z. Juhász G. (2014). The putative HORMA domain protein Atg101 dimerizes and is required for starvation-induced and selective autophagy in Drosophila. Biomed. Res. Int.2014, 470482. 10.1155/2014/470482

25

Hulsmans M. Clauss S. Xiao L. Aguirre A. D. King K. R. Hanley A. et al (2017). Macrophages facilitate electrical conduction in the heart. Cell169, 510–522. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.03.050

26

Huynh K. (2025). Tunnelling nanotube-like structures facilitate cell-cell communication during heart development. Nat. Rev. Cardiol.22, 396. 10.1038/s41569-025-01151-0

27

Jaiswal S. Natarajan P. Silver A. J. Gibson C. J. Bick A. G. Shvartz E. et al (2017). Clonal hematopoiesis and risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. N. Engl. J. Med.377, 111–121. 10.1056/NEJMoa1701719

28

Kirkland N. J. Skalak S. H. Whitehead A. J. Hocker J. D. Beri P. Vogler G. et al (2023). Age-dependent Lamin changes induce cardiac dysfunction via dysregulation of cardiac transcriptional programs. Nat. Aging3, 17–33. 10.1038/s43587-022-00323-8

29

Li A. Gao M. Liu B. Qin Y. Chen L. Liu H. et al (2022). Mitochondrial autophagy: molecular mechanisms and implications for cardiovascular disease. Cell Death Dis.13, 444. 10.1038/s41419-022-04906-6

30

Li S. Zhou X. Duan Q. Niu S. Li P. Feng Y. et al (2025). Autophagy and its association with macrophages in clonal hematopoiesis leading to atherosclerosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci.26, 3252. 10.3390/ijms26073252

31

Liang H. Su X. Wu Q. Shan H. Lv L. Yu T. et al (2020). LncRNA 2810403D21Rik/Mirf promotes ischemic myocardial injury by regulating autophagy through targeting Mir26a. Autophagy16, 1077–1091. 10.1080/15548627.2019.1659610

32

Lin M. Hua R. Ma J. Zhou Y. Li P. Xu X. et al (2021). Bisphenol A promotes autophagy in ovarian granulosa cells by inducing AMPK/mTOR/ULK1 signalling pathway. Environ. Int.147, 106298. 10.1016/j.envint.2020.106298

33

Lou E. Fujisawa S. Morozov A. Barlas A. Romin Y. Dogan Y. et al (2012). Tunneling nanotubes provide a unique conduit for intercellular transfer of cellular contents in human malignant pleural mesothelioma. PLoS One7, e33093. 10.1371/journal.pone.0033093

34

Madonna R. Moscato S. Cufaro M. C. Pieragostino D. Mattii L. Del Boccio P. et al (2023). Empagliflozin inhibits excessive autophagy through the AMPK/GSK3β signalling pathway in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc Res.119, 1175–1189. 10.1093/cvr/cvad009

35

Miao L. Lu Y. Nusrat A. Fan G. Zhang S. Zhao L. et al (2025). Tunneling nanotube-like structures regulate distant cellular interactions during heart formation. Science387, eadd3417. 10.1126/science.add3417

36

Morales P. E. Arias-Durán C. Ávalos-Guajardo Y. Aedo G. Verdejo H. E. Parra V. et al (2020). Emerging role of mitophagy in cardiovascular physiology and pathology. Mol. Asp. Med.71, 100822. 10.1016/j.mam.2019.09.006

37

Morrison S. J. Scadden D. T. (2014). The bone marrow niche for haematopoietic stem cells. Nature505, 327–334. 10.1038/nature12984

38

Ning B. Hang S. Zhang W. Mao C. Li D. (2023). An update on the bridging factors connecting autophagy and Nrf2 antioxidant pathway. Front. Cell Dev. Biol.11, 1232241. 10.3389/fcell.2023.1232241

39

Nussenzweig S. C. Verma S. Finkel T. (2015). The role of autophagy in vascular biology. Circ. Res.116, 480–488. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.303805

40

Ottonelli I. Caraffi R. Tosi G. Vandelli M. A. Duskey J. T. Ruozi B. (2022). Tunneling nanotubes: a new target for nanomedicine?Int. J. Mol. Sci.23, 2237. 10.3390/ijms23042237

41

Pai Y. L. Lin Y. J. Peng W. H. Huang L. T. Chou H. Y. Wang C. H. et al (2023). The deubiquitinase Leon/USP5 interacts with Atg1/ULK1 and antagonizes autophagy. Cell Death Dis.14, 540. 10.1038/s41419-023-06062-x

42

Polak R. de Rooij B. Pieters R. den Boer M. L. (2015). B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells use tunneling nanotubes to orchestrate their microenvironment. Blood126, 2404–2414. 10.1182/blood-2015-03-634238

43

Rainy N. Chetrit D. Rouger V. Vernitsky H. Rechavi O. Marguet D. et al (2013). H-Ras transfers from B to T cells via tunneling nanotubes. Cell Death Dis.4, e726. 10.1038/cddis.2013.245

44

Rustom A. Saffrich R. Markovic I. Walther P. Gerdes H. H. (2004). Nanotubular highways for intercellular organelle transport. Science303, 1007–1010. 10.1126/science.1093133

45

Singh G. Seufzer B. Song Z. Zucko D. Heng X. Boris-Lawrie K. (2022). HIV-1 hypermethylated guanosine cap licenses specialized translation unaffected by mTOR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.119, e2105153118. 10.1073/pnas.2105153118

46

Sowinski S. Jolly C. Berninghausen O. Purbhoo M. A. Chauveau A. Köhler K. et al (2008). Membrane nanotubes physically connect T cells over long distances presenting a novel route for HIV-1 transmission. Nat. Cell Biol.10, 211–219. 10.1038/ncb1682

47

Valdor R. Martinez-Vicente M. (2024). The role of chaperone-mediated autophagy in tissue homeostasis and disease pathogenesis. Biomedicines12, 257. 10.3390/biomedicines12020257

48

Venkatesh V. S. Lou E. (2019). Tunneling nanotubes: a bridge for heterogeneity in glioblastoma and a new therapeutic target?Cancer Rep. Hob.2, e1185. 10.1002/cnr2.1185

49

Walker S. G. Langland C. J. Viles J. Hecker L. A. Wallrath L. L. (2023). Drosophila models reveal properties of mutant Lamins that give rise to distinct diseases. Cells12, 1142. 10.3390/cells12081142

50

Wang X. Gerdes H. H. (2015). Transfer of mitochondria via tunneling nanotubes rescues apoptotic PC12 cells. Cell Death Differ.22, 1181–1191. 10.1038/cdd.2014.211

51

Wang X. Veruki M. L. Bukoreshtliev N. V. Hartveit E. Gerdes H. H. (2010). Animal cells connected by nanotubes can be electrically coupled through interposed gap-junction channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.107, 17194–17199. 10.1073/pnas.1006785107

52

Wang Y. Liang B. Lau W. B. Du Y. Guo R. Yan Z. et al (2017). Restoring diabetes-induced autophagic flux arrest in ischemic/reperfused heart by ADIPOR (adiponectin receptor) activation involves both AMPK-dependent and AMPK-independent signaling. Autophagy13, 1855–1869. 10.1080/15548627.2017.1358848

53

Wang N. Ma H. Li J. Meng C. Zou J. Wang H. et al (2021). HSF1 functions as a key defender against palmitic acid-induced ferroptosis in cardiomyocytes. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol.150, 65–76. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2020.10.010

54

Wang P. Xu S. Xu J. Xin Y. Lu Y. Zhang H. et al (2022). Elevated MCU expression by CaMKIIδB limits pathological cardiac remodeling. Circulation145, 1067–1083. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.055841

55

Yang L. Wang H. Shen Q. Feng L. Jin H. (2017). Long non-coding RNAs involved in autophagy regulation. Cell Death Dis.8, e3073. 10.1038/cddis.2017.464

56

Yunna C. Mengru H. Lei W. Weidong C. (2020). Macrophage M1/M2 polarization. Eur. J. Pharmacol.877, 173090. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2020.173090

57

Zhang S. Peng X. Yang S. Li X. Huang M. Wei S. et al (2022). The regulation, function, and role of lipophagy, a form of selective autophagy, in metabolic disorders. Cell Death Dis.13, 132. 10.1038/s41419-022-04593-3

58

Zhang Z. Chen L. Chen X. Qin Y. Tian C. Dai X. et al (2022). Exosomes derived from human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells (HUCMSC-EXO) regulate autophagy through AMPK-ULK1 signaling pathway to ameliorate diabetic cardiomyopathy. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.632, 195–203. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2022.10.001

59

Zhao B. Zhang J. Zhao K. Wang B. Liu J. Wang C. et al (2025). Effect of rapamycin on hepatic metabolomics of non-alcoholic fatty liver rats based on non-targeted platform. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal.253, 116541. 10.1016/j.jpba.2024.116541

60

Zhou X. Li Z. Wang Z. Chen E. Wang J. Chen F. et al (2018). Syncytium calcium signaling and macrophage function in the heart. Cell Biosci.8, 24. 10.1186/s13578-018-0222-6

61

Zhou R. Zhang Z. Li X. Duan Q. Miao Y. Zhang T. et al (2025). Autophagy in high-fat diet and streptozotocin-induced metabolic cardiomyopathy: mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci.26, 1668. 10.3390/ijms26041668

Summary

Keywords

cardioprotective function of autophagy, endocardial and myocardial precursors, cellular conduction system of tunneling nanotube TNT, autophagy associated physiological homeostasis, selective and non-selective autophagy in heart

Citation

Duan Q, Xu X, Jones OD, Ma J, Bryant JL and Xu M (2025) Editorial: The role of autophagy in cardiovascular disease. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 13:1697218. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2025.1697218

Received

02 September 2025

Revised

15 September 2025

Accepted

15 September 2025

Published

19 November 2025

Volume

13 - 2025

Edited and reviewed by

You-Wen He, Duke University, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Duan, Xu, Jones, Ma, Bryant and Xu.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xuehong Xu, xhx0708@snnu.edu.cn, xhx070862@163.com; Mengmeng Xu, mex9002@nyp.org

ORCID: Xuehong Xu, orcid.org/0000-0003-2986-1771

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.