Abstract

The loss of chromosome 3p and the inactivation of the tumor suppressor gene von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) were identified in clear cell renal cell carcinomas (ccRCC) over three decades ago. Since then, mutations in genes for the three chromatin modulators, polybromo 1 (PBRM1), SET domain-containing 2 (SETD2), and BRCA1-associated protein-1 (BAP1), have been recognized as common in ccRCC. Although these genomic alterations are central to understanding ccRCC’s development, other deregulated cellular processes are also prominent in these tumors. Metabolic reprogramming is a key hallmark of this disease, characterized by various changes linked to the stabilization of hypoxia-inducible factors (HIF), including increased aerobic glycolysis, elevated lipid levels, and glutamine dependence for cell survival. Additionally, HIF-α stabilization plays a crucial role in regulating the immune system, thereby enhancing CD8+ T lymphocyte cytotoxicity. Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) are now used as first-line treatments to target the often highly infiltrated tumor microenvironment of ccRCC. However, the effectiveness of ICI varies and is difficult to predict. Although emerging studies are beginning to provide insight, evidence suggests roles for PBRM1, SETD2, and BAP1 in metabolic regulation and in shaping the tumor immune microenvironment in ccRCC. Here, we review recent advances in this field and examine their impact on the management of ccRCC.

1 Introduction

Clear cell renal cell carcinomas (ccRCC) are the most diagnosed type of kidney cancer, representing 80% of all cases (Yo et al., 2024). Loss of heterozygosity on chromosome 3p, along with inactivation of the last copy of the tumor suppressor gene von Hippel-Lindau (VHL), located on chromosome 3p25-26, are key features of ccRCC (Kovacs et al., 1988; Kovacs et al., 1987; Latif et al., 1993). Aside from VHL, the most frequently mutated genes in ccRCC are polybromo 1 (PBRM1), SET domain containing 2 (SETD2), and BRCA1-associated protein-1 (BAP1), all of which are chromatin modulators found on the short arm of chromosome 3p (Dalgliesh et al., 2010; Peña-Llopis et al., 2012; Varela et al., 2011). Precisely, PBRM1 is part of the PBAF complex implicated in chromatin remodeling for DNA accessibility, SETD2 is a lysine methyltransferase best known for its role in trimethylating histone H3 on lysine 36 (H3K36me3) and regulating transcription, and BAP1 is the core component of the Polycomb repressive deubiquitinase complex (PR-DUB), which challenge the ubiquitinase activity of the Polycomb Repressive Complex 1 (PRC1) on histone H2A (H2AK119ub). Their loss is associated with genomic instability, often due to disruption in DNA damage repair and chromatin maintenance. According to the TRACERx Renal project, mutational profiles are key to ccRCC development and variability, with the inactivation of specific genes associated with cancer aggressiveness (Mitchell et al., 2018; Turajlic et al., 2018a; Turajlic et al., 2018b). Historically known to be resistant to chemotherapy and radiotherapy, patients with metastatic ccRCC have benefited from the development of targeted therapies and immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI). However, some tumors exhibit or ultimately develop resistance to these treatments, raising the questions: why? and how? Countless studies have focused on understanding the unique features or mechanisms that could explain differences in treatment response. From these mechanisms, we observe an increase in lactic acid in the tumor microenvironment (TME) caused by the notorious Warburg effect. This has been linked to the neutralization of immune cells’ antitumoral activities and to an increase in tryptophan catabolism, leading to higher levels of kynurenine and immunosuppression (Wettersten et al., 2017; Sh et al., 2024). In this minireview, we aim to shed light on the roles of PBRM1, SETD2, and BAP1 in the tumor metabolic and immune microenvironments, and discuss how these functions could benefit the management of advanced ccRCC.

2 Metabolic landscape: ripples in clear water

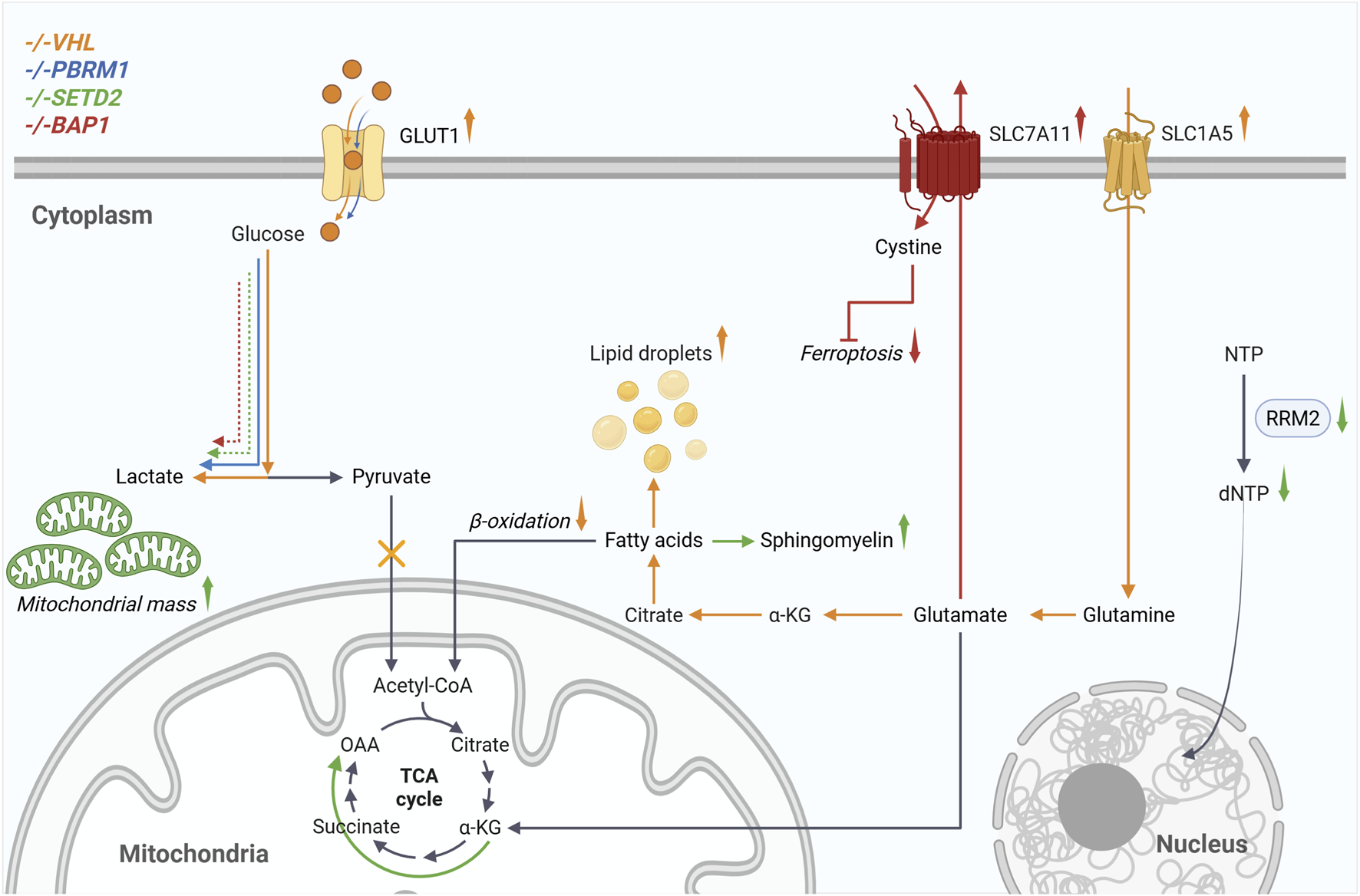

Kidney cancers are considered metabolic diseases caused by genetic alterations disrupting cell metabolism. This is clearly illustrated in ccRCC by the constitutive stabilization of hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs) linked to VHL loss, leading to metabolic reprogramming. This includes increased aerobic glycolysis, glutamine dependency for fatty acid synthesis, and cytosolic accumulation of lipid and glycogen, which gives the cells a clear morphology (Rezende et al., 1999). Although many metabolic characteristics observed in ccRCC stem from VHL loss, new evidence indicates that loss of PBRM1, SETD2, and BAP1 can also disrupt these pathways (Figure 1). While studying how the loss of PBRM1 impacts ccRCC tumorigenesis in mice, Nargund et al. demonstrated that kidney-specific inactivation of Vhl or Pbrm1 alone did not lead to tumor formation (Nargund et al., 2017). It was only when both genes were inactivated simultaneously that the mouse developed ccRCC. Additionally, RNA sequencing data identified pathways that could explain how Pbrm1 loss contributes to tumor formation in a Vhl-deficient model. These results showed that both the HIF and JAK/STAT pathways, especially STAT3, were upregulated. They also revealed a decrease in the expression of genes related to oxidative phosphorylation, which occurs before activation of the mTORC1 pathway. While RNA sequencing studies have identified multiple metabolic pathways associated with variation in PBRM1 expression, only a limited number of published articles have investigated the specific role of PBRM1 in metabolism (Nargund et al., 2017; Chowdhury et al., 2016). In one of the few studies, it was shown that reintroducing PBRM1 into Caki-2 cells decreased glucose uptake and the AKT pathway (Chowdhury et al., 2016). This was further supported by an independent study reporting results from 786-0 and SN12C cells expressing PBRM1-knockdown achieved through shRNA (Tang et al., 2022). Given that PBRM1 directly modulates ccRCC metabolism through HIF-1α, this prompts the question of whether SETD2 or BAP1 might also display similar HIF-1α-dependent functions. In a sepsis-induced setting, decreased SETD2 expression leads to increased HIF-1α and glycolysis, promoting M1 macrophage polarization (Meng et al., 2023). A decrease in nuclear HIF-1α signal was observed in mesothelioma cases with germline BAP1 mutations, particularly those with biallelic mutations, which revealed BAP1’s interaction with HIF-1α (Bononi et al., 2023). In fact, Bononi et al. demonstrated that BAP1 can directly interact with and deubiquitylate HIF-1α under hypoxic conditions, thereby stabilizing HIF-1α, which was linked to increased aggressiveness in BAP1 wild-type mesotheliomas. Evidently, these findings were examined in pathological contexts beyond ccRCC. Because HIF-1α becomes stabilized and abundant as a result of VHL inactivation in ccRCC, further detailed analysis is required to evaluate how the loss of SETD2 or BAP1 influences HIF-1α expression and the associated metabolic regulation in ccRCC.

FIGURE 1

Loss of VHL and the associated stabilization of HIF cause the metabolic reprogramming known as the Warburg effect. This includes increased glucose uptake, glycolysis, and lactate production, which are further enhanced by loss of PBRM1, SETD2, and BAP1. ccRCC cells become dependent on glutamine for survival. Transmembrane transporters such as SLC1A5 enable cells to increase glutamine uptake, which is then metabolized via glutaminolysis and the reductive TCA cycle for de novo fatty acid synthesis. Additionally, β-oxidation is reduced, and lipid droplets are formed. When SETD2 is inactivated, cells exhibit increased mitochondrial mass and oxidative phosphorylation. Downregulation of RRM2 reduces dNTP levels, which are required for DNA replication. The increased expression of SLC7A11, resulting from BAP1 loss, enables cystine import, which subsequently leads to glutathione synthesis and resistance to ferroptosis. Created in BioRender. Johnson, M. (2025)https://BioRender.com/eg77e9h..

Cells from ccRCC are well known to rely on glutamine for survival. The glutamine undergoes glutaminolysis before entering the reductive tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle to produce citrate for fatty acid synthesis (Metallo et al., 2012). Conversely, loss of SETD2 was shown to enhance oxidative phosphorylation instead of the reductive TCA cycle. Knockout of SETD2 in the 786-0 ccRCC cell line results in increased expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1α (PGC-1α) and higher mitochondrial mass, leading to the rerouting of glutamine metabolism (Liu et al., 2019). Similarly, in non-small cell lung cancer, Setd2-inactivation led to an increase in oxidative respiration (W et al., 2023). Changes in mitochondrial morphology were also observed, with an increase in cristae within mitochondria when Setd2 was removed, although mitochondrial mass decreased. PGC-1α can also be regulated by BAP1, which directly binds to O-GlcNAcylated PGC-1α to prevent its degradation (Ruan et al., 2012). This was demonstrated in the context of insulin resistance in diabetes, where the O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT) and host cell factor-1 (HCF-1) interact with PGC-1α to promote its O-GlcNAcylation, facilitating BAP1 recruitment for deubiquitination and protecting PGC-1α from degradation. Stabilization of PGC-1α and increased hepatic gluconeogenesis are associated with diabetes, and knocking down OGT and HCF-1 in the liver of diabetic mice helped reduce gluconeogenesis and regulate glucose homeostasis. Metabolic regulations by BAP1 were also reported in vivo using the neutron-encoded (NeuCode) amino acid labeling method, which observed hypoglycemia and metabolic alterations in various tissues of Bap1-knockout mice (Baughman et al., 2016). Before uncovering BAP1’s role in regulating HIF-1α, the same group demonstrated how aerobic glycolysis increases with germline BAP1 mutations (Bononi et al., 2017). Metabolic profiling was able to distinguish between individuals with wild-type BAP1 from those with mutated BAP1. People with BAP1 syndrome have loss-of-function mutations in BAP1 in their primary cells, resulting in increased glucose consumption and lactate secretion. Mitochondrial respiration also declined, as shown by reduced oxygen consumption rates. These changes could not be linked to significant transcriptional differences, and no variations were observed in mitochondrial morphology, quantity, or membrane potential. Alternatively, it was demonstrated that BAP1 can be recruited to the promoter of cytochrome c oxidase subunit 7C (COX7C) and act as a coactivator for its transcription (Yu et al., 2010). This role was found to depend on BAP1 interaction with HCF-1 and Yin Yang 1 (YY1). However, the reduction in COX7C’s impact on overall cell metabolism was not further explored.

Some metabolic alterations associated with PBRM1, SETD2 and BAP1 have been shown to play important roles in the evolution of ccRCC. As previously mentioned, downregulation of oxidative phosphorylation was observed during tumor growth following Vhl and Pbrm1 inactivation, which triggered mTORC1 activation (Nargund et al., 2017). In a polycystic kidney disease (PKD) model where c-MYC is overexpressed, Setd2-inactivation leads to an increase in sphingomyelin and the development of ccRCC tumors (Rao et al., 2023). The significance of this metabolic change was demonstrated by treating with myriocin to inhibit sphingomyelin biosynthesis, which limited tumor growth. Sphingomyelin levels were also higher in samples from patients with ccRCC who had low SETD2 expression. With the characterization of ferroptosis over the last 2 decades, understanding its mechanism led to the discovery of BAP1’s regulation of SLC7A11. BAP1 loss-of-function leads to increased SLC7A11 expression, facilitating enhanced cystine import, glutathione synthesis, and resistance to ferroptosis (Zhang et al., 2018). This resistance would enable BAP1-deficient cells to evade cell death and consequently promote tumor growth. Furthermore, some metabolic alterations can be exploited as therapeutic targets. Since SETD2 positively regulates ribonucleotide reductase M2 (RRM2), inactivating SETD2 reduces the dNTP pool, which confers vulnerability to WEE1 inhibitors (Pfister et al., 2015).

3 Tumor immune microenvironment: how to tame wildfires?

The emergence of the ICI as a treatment option for cancers has radically transformed the management of patients with advanced ccRCC over the past decade. Targeted therapies, such as VEGF and mTOR inhibitors, are now mainly used in combination with ICI as first-line or second-line treatments (Kimryn Rathmell et al., 2022). ccRCC tumors are considered « hot», meaning they are inflamed with a high number of immune cells. Despite being highly infiltrated, ccRCC can still evade immune destruction. In fact, CD8+ cytotoxic T cells in the ccRCC TME are often exhausted, impairing their function. Notably, cancers at higher stages display a greater presence of exhausted CD8+ T cells and M2 tumor-associated macrophages (Braun et al., 2021). How the specific mutations found in ccRCC influence the TME is still unclear. Recently, Jiao et al. demonstrated that loss of VHL improves the effectiveness of anti-programmed death 1 (PD-1) therapy in a T cell-dependent context manner through the cGAS-STING pathway (Jiao et al., 2024). However, since the relationship between VHL status and the TME remains in its early stages, it is not surprising that much remains to be explored regarding PBRM1, SETD2, and BAP1 in relation to the ccRCC TME.

The loss of PBRM1 function in melanoma was first associated with higher vulnerability to T-cell-mediated killing (Pan et al., 1979). In a genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 screen, sgRNAs for the three unique subunits of the PBAF complex, PBRM1, ARID2 and BRD7, were depleted after exposure to T-cells, indicating increased cell vulnerability to T-cell-mediated killing when these proteins are altered. Furthermore, tumors from Pbrm1-deficient B16-F10 cells exhibited increased levels of dendritic cells, a higher ratio of M1 to M2 macrophages, and enhanced activation of immune responses, particularly through the interferon-gamma (IFNγ) pathway. Using whole exome sequencing, Miao et al. showed a correlation between patients with metastatic ccRCC harboring PBRM1 loss-of-function mutations and improved outcomes following treatments with nivolumab (Miao et al., 2018). Not long after, results from the phase 2 IMmotion150 study failed to replicate those findings, reporting no significant difference in clinical outcomes between patients with or without PBRM1 mutations when treated with atezolizumab alone or in combination with bevacizumab (McDermott et al., 2018). Notably, patients with PBRM1 mutations demonstrated a better response to sunitinib (McDermott et al., 2018). Braun et al. contributed to these findings by reporting improved responses to nivolumab in patients with a mutated PBRM1 and subsequently found that tumors with CD8+ T-infiltrated cells had a lower frequency of PBRM1 mutation (Braun et al., 2019; Braun et al., 2020). Then, by using shRNA targeting Pbrm1 in kidney Renca cells, another group demonstrated that low Pbrm1 expression correlates with reduced infiltration of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Aili et al., 2021). Meanwhile, conflicting results have been reported regarding the impact of PBRM1 loss on ICI response. PBRM1 inactivation in ccRCC cells reduces IFNγ-JAK2-STAT1 signaling, leading to reduced T cells infiltration in the TME (Liu et al., 2020). However, when assessing how these results impact the response to anti-PD-1 treatments, administering a PD-1 antibody did not affect tumor growth or the survival of mice injected with Pbrm1-knockout Renca cells (Liu et al., 2020). It is important to note that tumors from wild-type Renca cells were larger and worsened the survival of the mice compared to the Pbrm1-knockout. Nonetheless, using data from three different patient cohorts (TCGA-KIRK, IMmotion150, and International Cancer Genome Consortium), they showed reduced expression of multiple immune-related genes, lower immune cell infiltration, and a decreased response rate to atezolizumab alone or in combination with bevacizumab in patients with mutated PBRM1. Paradoxically, the exclusion of PBRM1’s exon 27 by alternative splicing, regulated by the splicing factor RBFOX2, altered the recruitment of the PBAF complex to PD-L1 promoter and reduced its expression (Cho et al., 2024). In ccRCC, exon 27 was significantly excluded compared with normal tissue and was associated with increased RBFOX2 expression. While patients with PBRM1 mutations showed better overall response, high RBFOX2 expression improved survival in those with PBRM1 wild-type when treated with nivolumab. Altogether, there appears to be a consensus that PBRM1-mutated ccRCCs are associated with a less inflamed TME; however, the specifics of how these tumors respond to immunotherapy remain a subject of debate.

The role of SETD2 in the immune response was first reported in hepatitis B virus infection (Chen et al., 2017). Chen et al. demonstrated that SETD2 directly interacts with STAT1, methylating STAT1 on lysine 525 to promote its phosphorylation and activation. Additionally, the cGAS-STING pathway, which is closely connected to the activation of type I IFN and STAT1 pathways, was shown to play a significant role in the vulnerability of SETD2-deficient ccRCC to ATR inhibition (Liu et al., 2023). Alternatively, STAT1 was reported to be negatively regulated by nuclear receptor subfamily 2, group F, member 1 (NR2F1), which is repressed when SETD2 is inactivated, thereby allowing upregulation and activation of STAT1 (Zheng et al., 2023). With SETD2’s essential role in DNA repair, its inactivation has been associated with an increased tumor mutational burden, which can enhance T cell recognition via the major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC-1). Additionally, they validated these results using TCGA data in a ccRCC cohort, where NR2F1 expression was decreased when SETD2 was either absent or expressed at low levels. Although there has been increased interest in studying SETD2 in ccRCC over the past few years, research on SETD2 and its role in influencing the tumor immune microenvironment of this cancer has barely begun. A handful of studies have been performed in the context of pancreatic cancer and suggested that SETD2 loss modulates the TME in an immunosuppressive state (Niu et al., 2024; Niu et al., 2023). Setd2 inactivation was associated with increased neutrophil infiltration and the suppression of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells (Niu et al., 2023). Mechanistically, a decrease in H3K36me3 caused by the loss of Setd2 was followed by an increase in H3K27me3. This resulted in downregulation of the Cxadr cell adhesion molecule, thereby enhancing AKT pathway activation and increasing expression of C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 1 (CXCL1) and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), facilitating the recruitment of neutrophils with higher levels of PD-L1. In a pan-cancer analysis including the TCGA-KIRC cohort, data showed an overall correlation between SETD2 deficiency, a more prominent immune activation signature, and higher tumor mutational burden (Lu et al., 2021).

As for BAP1, its loss has recurrently been associated with a more inflamed TME. Following analysis of two clusters of ccRCC patients, identified as the inflamed and non-inflamed subtypes, BAP1 mutations were found to be significantly more common in the inflamed subtype (Wang et al., 2018). In this study, patients with PBRM1 mutations were found to be more heterogeneous in both clusters, which may explain the conflicting results presented earlier. The inflammatory effect of BAP1 loss in the TME is also noticeable in malignant pleural mesothelioma, a cancer frequently mutated in BAP1 (Xu et al., 2024). Similar to PBRM1 and SETD2, it has been suggested that BAP1 also regulates the interferon pathways. Specifically, BAP1 typically promotes the activation of IFNβ and STING mediated by HIF-2α, which helps inhibit tumor growth through the activation of interferon stimulated gene factor 3 (ISGF3) (Langbein et al., 2022). Activation of this pathway was sufficient to limit tumor growth of cell line-derived xenografts from BAP1-inactivated Ren-02 cells. As an alternative therapeutic approach for metastatic ccRCC, preliminary data have shown a better response with a cell line-derived xenograft with a BAP1-mutated ccRCC cell line, 769-P, when treated with the oncolytic vaccinia virus (JX-594) (Park et al., 2025). Further experiments are needed to confirm whether sensitivity to JX-594 is truly linked to BAP1 mutations rather than to other genetic changes in the 769-P cell line. Additionally, although it is not the primary focus of this mini-review, it is worth noting that multiple studies have shown roles for these three genes in the development and regulation of various immune cells (Meng et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2024; Chu et al., 2020; Ding et al., 2022; Takagi-Kimura et al., 2022; Ji et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2024; Li BE. et al., 2023).

4 At the crossroad of metabolic alterations and tumor immune microenvironment modulation

The characterization of the impacts associated to the loss of these three commonly mutated genes offers new opportunities to manage advanced ccRCC, such as using them as biomarkers for treatment prediction, thereby assisting in selecting the most suitable treatment for each patient, aligning with precision medicine. With their specific roles in regulating metabolic and immune pathways that have only recently begun to be understood, mechanistic studies often overlook how these genes are interconnected and how the loss of one can impact the functions of others. Alternatively, many studies on BAP1 or SETD2 have been conducted in other cancers and need to be confirmed in ccRCC.

Classification of ccRCC tumors based on their immune or metabolic signatures provides crucial insights into tumor progression and treatment options. In 2019, Clark et al. used proteogenomic analysis to classify ccRCC into four immune subtypes: CD8+ inflamed, CD8- inflamed, VEGF immune-desert, and metabolic immune-desert (Clark et al., 2019). PBRM1 mutations were more common in the VEGF immune-desert subtype, which was associated with lower-grade tumors and increased expression of proteins involved in glycolysis, hypoxia, and the mTOR pathway. Conversely, BAP1 mutations were more prevalent in the CD8+ inflamed subtypes, which were associated with higher-grade tumors and higher protein expression in pathways such as OXPHOS, fatty acid metabolism, and the adaptive immune response. A subsequent multi-omics study classified ccRCC into tumor immune subtypes (IM1-4) similar to those identified previously (Hu et al., 2024). This study characterized subtypes by their endothelial, stromal, and immune cell signatures. Both IM1 and IM2 signatures indicate high endothelial cell levels, with IM1 showing stromal cell enrichment and immune exclusion, while IM2 shows depletion of stromal and immune cells. IM3 displays low levels of endothelial and stromal cells, but infiltration by T cells and tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs). IM4 features high levels of stromal cells and TAM, along with intermediate levels of T cells. They also stratified tumors based on metabolic signatures, revealing a group with fewer lipid droplets, predominantly in IM4. Their extended data clearly show that PBRM1 mutations are present across all four subtypes, whereas SETD2 and BAP1 mutations are absent in IM1 but more common in IM3 and IM4.

Preliminary results from the TRACERx Renal project were first published nearly a decade ago; however, evolutionary subtypes are still underrepresented in research, especially in studies using simpler models such as 2D cell cultures (Turajlic et al., 2018b). The development of new experimental models, such as spheroids, organoids, patient-derived xenografts, and genetically engineered mouse models, offers opportunities, despite limitations, to study how cancer cells interact with the immune system. Nevertheless, in the most recent publication from the TRACERx Renal project, they investigated the relationship between prominent genomic alterations observed in the seven evolutionary subtypes and the tumor immune microenvironment (Fernández-Sanromán et al., 2025). By comparing paired samples from the primary tumor and the metastases, the loss of SETD2 was associated with a transition to an immunosuppressive TME. The loss of chromosome 9p was the only other somatic alteration showing this tendency. Among the three genes, the loss of SETD2 is typically a subclonal event, whereas the loss of PBRM1 or BAP1 usually occurs as a clonal event earlier in tumor progression. It is also unclear how SETD2 impacts the aggressiveness of the cancer. However, with increasing interest in that gene, new evidence, such as the one reported from the TRACERx Renal project, highlights SETD2 as a key player and a potential therapeutic target. We recently reported that SETD2 inactivation in ccRCC expressing wild-type VHL sensitizes cells to STF-62247 resulting in a cell cycle block in S-phase (Johnson and Turcotte, 2025). As Liu et al. stated and further demonstrated in their study, targeting the S-phase DNA damage repair network can improve the response to immune checkpoint inhibitors (Liu et al., 2023). According to this theory, co-treatment with STF-62247 and ICI could produce a synergic cytotoxicity. Other proteins and pathways related to metabolism have also been suggested as potential therapeutic targets for cancer cells lacking SETD2, including the PI3K pathway, WEE1, and the mTORC1 signaling pathway (W et al., 2023; Pfister et al., 2015; Terzo et al., 2019).

Overall, PBRM1, SETD2, and BAP1 have been associated with specific metabolic and immune alterations; however, this area remains underexplored and holds promise. Targeting metabolic deregulation associated with these mutated genes offers a promising strategy for developing new therapies, especially when combined with immunotherapy. The increase in lactate secretion related to aerobic glycolysis, which has been shown to be amplified by the loss of PBRM1 under hypoxic conditions, could be targeted with lactate-focused treatments such as the monocarboxylate transporter 1 (MCT1) inhibitor AZD3965 (Tang et al., 2022; Halford et al., 2023). However, aside from one study showing a positive response to AZD3965 treatment in xenograft models, specifically when lysine acetyltransferase 2A (KAT2A) was overexpressed, and MCT1 was upregulated, no clinical data demonstrate the response of this treatment in patients with ccRCC (Li X. et al., 2023; Guo et al., 2021). Nonetheless, there is still a long road ahead and more studies needed on metabolic changes caused by the loss of these genes and their influence on the tumor immune microenvironment before this knowledge can be fully utilized to guide clinical decisions in ccRCC.

Statements

Author contributions

MJ: Writing – original draft. ST: Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. ST is supported by a Canadian Cancer Society Research Chair (#706199). ST acknowledges the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (#186322) for their financial support. A Research Professional initiative from ResearchNB supported MJ.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Aili A. Wen J. Xue L. Wang J. (2021). Mutational analysis of PBRM1 and significance of PBRM1 mutation in Anti-PD-1 immunotherapy of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Front. Oncol.11, 712765. 10.3389/fonc.2021.712765

2

Baughman J. M. Rose C. M. Kolumam G. Webster J. D. Wilkerson E. M. Merrill A. E. et al (2016). NeuCode proteomics reveals Bap1 regulation of metabolism. Cell Rep.16 (2), 583–595. 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.05.096

3

Bononi A. Yang H. Giorgi C. Patergnani S. Pellegrini L. Su M. et al (2017). Germline BAP1 mutations induce a warburg effect. Cell Death Differ.24 (10), 1694–1704. 10.1038/cdd.2017.95

4

Bononi A. Wang Q. Zolondick A. A. Bai F. Steele-Tanji M. Suarez J. S. et al (2023). BAP1 is a novel regulator of HIF-1α. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.120 (4), e2217840120. 10.1073/pnas.2217840120

5

Braun D. A. Ishii Y. Walsh A. M. Van Allen E. M. Wu C. J. Shukla S. A. et al (2019). Clinical validation of PBRM1 alterations as a marker of immune checkpoint inhibitor response in renal cell carcinoma. JAMA Oncol.5 (11), 1631–1633. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.3158

6

Braun D. A. Hou Y. Bakouny Z. Ficial M. Sant’ Angelo M. Forman J. et al (2020). Interplay of somatic alterations and immune infiltration modulates response to PD-1 blockade in advanced clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Nat. Med.26 (6), 909–918. 10.1038/s41591-020-0839-y

7

Braun D. A. Street K. Burke K. P. Cookmeyer D. L. Denize T. Pedersen C. B. et al (2021). Progressive immune dysfunction with advancing disease stage in renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Cell39 (5), 632–648.e8. 10.1016/j.ccell.2021.02.013

8

Chen K. Liu J. Liu S. Xia M. Zhang X. Han D. et al (2017). Methyltransferase SETD2-Mediated methylation of STAT1 is critical for interferon antiviral activity. Cell170 (3), 492–506.e14. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.06.042

9

Chen Y. Chen K. Zhu H. Qin H. Liu J. Cao X. (2024). Methyltransferase Setd2 prevents T cell–mediated autoimmune diseases via phospholipid remodeling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.121 (8), e2314561121. 10.1073/pnas.2314561121

10

Cho N. Kim S. Y. Lee S. G. Park C. Choi S. Kim E. M. et al (2024). Alternative splicing of PBRM1 mediates resistance to PD-1 blockade therapy in renal cancer. EMBO J.43 (22), 5421–5444. 10.1038/s44318-024-00262-7

11

Chowdhury B. Porter E. G. Stewart J. C. Ferreira C. R. Schipma M. J. Dykhuizen E. C. (2016). PBRM1 regulates the expression of genes involved in metabolism and cell adhesion in renal clear cell carcinoma. PLoS One11 (4), e0153718. 10.1371/journal.pone.0153718

12

Chu S. H. Chabon J. R. Matovina C. N. Minehart J. C. Chen B. R. Zhang J. et al (2020). Loss of H3K36 methyltransferase SETD2 impairs V(D)J recombination during lymphoid development. iScience23 (3), 100941. 10.1016/j.isci.2020.100941

13

Clark D. J. Dhanasekaran S. M. Petralia F. Pan J. Song X. Hu Y. et al (2019). Integrated proteogenomic characterization of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Cell179 (4), 964–983.e31. 10.1016/j.cell.2019.10.007

14

Dalgliesh G. L. Furge K. Greenman C. Chen L. Bignell G. Butler A. et al (2010). Systematic sequencing of renal carcinoma reveals inactivation of histone modifying genes. Nature463 (7279), 360–363. 10.1038/nature08672

15

Ding Z. Cai T. Tang J. Sun H. Qi X. Zhang Y. et al (2022). Setd2 supports GATA3+ST2+ thymic-derived treg cells and suppresses intestinal inflammation. Nat. Commun.13 (1), 7468. 10.1038/s41467-022-35250-0

16

Fernández-Sanromán Á. Fendler A. Tan B. J. Y. Cattin A. L. Spencer C. Thompson R. et al (2025). Tracking nongenetic evolution from primary to metastatic ccRCC: TRACERx renal. Cancer Discov.15 (3), 530–552. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-24-0499

17

Guo Y. Liu B. Liu Y. Sun W. Gao W. Mao S. et al (2021). Oncogenic chromatin modifier KAT2A activates MCT1 to drive the glycolytic process and tumor progression in renal cell carcinoma. Front. Cell Dev. Biol.9, 690796. 10.3389/fcell.2021.690796

18

Halford S. Veal G. J. Wedge S. R. Payne G. S. Bacon C. M. Sloan P. et al (2023). A phase I dose-escalation study of AZD3965, an oral monocarboxylate transporter 1 inhibitor, in patients with advanced cancer. Clin. Cancer Res.29 (8), 1429–1439. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-22-2263

19

Hu J. Wang S. G. Hou Y. Chen Z. Liu L. Li R. et al (2024). Multi-omic profiling of clear cell renal cell carcinoma identifies metabolic reprogramming associated with disease progression. Nat. Genet.56 (3), 442–457. 10.1038/s41588-024-01662-5

20

Ji Z. Sheng Y. Miao J. Li X. Zhao H. Wang J. et al (2019). The histone methyltransferase Setd2 is indispensable for V(D)J recombination. Nat. Commun.10 (1), 3353. 10.1038/s41467-019-11282-x

21

Jiao M. Hu M. Pan D. Liu X. Bao X. Kim J. et al (2024). VHL loss enhances antitumor immunity by activating the anti-viral DNA-Sensing pathway. iScience27 (7), 110285. 10.1016/j.isci.2024.110285

22

Johnson M. Turcotte S. (2025). Loss of SETD2 in wild-type VHL clear cell renal cell carcinoma sensitizes cells to STF-62247 and leads to DNA damage, cell cycle arrest, and cell death characteristic of pyroptosis. Mol. Oncol.19 (4), 1244–1264. 10.1002/1878-0261.13770

23

Kimryn Rathmell W. Bryan R. Van Veldhuizen J. Al-Ahmadie H. Hamid E. (2022). Management of metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma: ASCO guideline, J. Clin. Oncol.40. 10.1200/JCO.22.00868

24

Kovacs G. Szücs S. De Riese W. Baumgärtel H. (1987). Specific chromosome aberration in human renal cell carcinoma. Int. J. Cancer40 (2), 171–178. 10.1002/ijc.2910400208

25

Kovacs G. Erlandsson R. Boldog F. Ingvarsson S. Müller-Brechlin R. Klein G. et al (1988). Consistent chromosome 3p deletion and loss of heterozygosity in renal cell carcinoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.85 (5), 1571–1575. 10.1073/pnas.85.5.1571

26

Langbein L. E. El Hajjar R. He S. Sementino E. Zhong Z. Jiang W. et al (2022). BAP1 maintains HIF-dependent interferon beta induction to suppress tumor growth in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Lett.547, 215885. 10.1016/j.canlet.2022.215885

27

Latif F. Tory K. Gnarra J. Yao M. Duh F. Lou O. M. et al (1993). Identification of the von Hippel-Lindau Disease Tumor Suppressor Gene. Sci. (1979)260 (5112), 1317–1320. 10.1126/science.8493574

28

Li B. E. Li G. Y. Cai W. Zhu Q. Seruggia D. Fujiwara Y. et al (2023a). In vivo CRISPR/Cas9 screening identifies Pbrm1 as a regulator of myeloid leukemia development in mice. Blood Adv.7 (18), 5281–5293. 10.1182/bloodadvances.2022009455

29

Li X. Du G. Li L. Peng K. (2023b). Cellular specificity of lactate metabolism and a novel lactate-related gene pair index for frontline treatment in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Front. Oncol.13, 1253783. 10.3389/fonc.2023.1253783

30

Liu J. Hanavan P. D. Kras K. Ruiz Y. W. Castle E. P. Lake D. F. et al (2019). Loss of SETD2 induces a metabolic switch in renal cell carcinoma cell lines toward enhanced oxidative phosphorylation. J. Proteome Res.18 (1), 331–340. 10.1021/acs.jproteome.8b00628

31

Liu X. De Kong W. Peterson C. B. McGrail D. J. Hoang A. Zhang X. et al (2020). PBRM1 loss defines a nonimmunogenic tumor phenotype associated with checkpoint inhibitor resistance in renal carcinoma. Nat. Commun.11 (1), 2135. 10.1038/s41467-020-15959-6

32

Liu X. De Zhang Y. T. McGrail D. J. Zhang X. Lam T. Hoang A. et al (2023). SETD2 loss and ATR inhibition synergize to promote cGAS signaling and immunotherapy response in renal cell carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res.29 (19), 4002–4015. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-23-1003

33

Lu M. Zhao B. Liu M. Wu L. Li Y. Zhai Y. et al (2021). Pan-cancer analysis of SETD2 mutation and its association with the efficacy of immunotherapy. NPJ Precis. Oncol.5 (1), 51. 10.1038/s41698-021-00193-0

34

McDermott D. F. Huseni M. A. Atkins M. B. Motzer R. J. Rini B. I. Escudier B. et al (2018). Clinical activity and molecular correlates of response to atezolizumab alone or in combination with bevacizumab versus sunitinib in renal cell carcinoma. Nat. Med.24 (6), 749–757. 10.1038/s41591-018-0053-3

35

Meng Y. wen K. K. Chang Y. Deng X. Yang T. (2023). Histone methyltransferase SETD2 inhibits M1 macrophage polarization and glycolysis by suppressing HIF-1α in sepsis-induced acute lung injury. Med. Microbiol. Immunol.212 (5), 369–379. 10.1007/s00430-023-00778-5

36

Metallo C. M. Gameiro P. A. Bell E. L. Mattaini K. R. Yang J. Hiller K. et al (2012). Reductive glutamine metabolism by IDH1 mediates lipogenesis under hypoxia. Nature481 (7381), 380–384. 10.1038/nature10602

37

Miao D. Margolis C. A. Gao W. Voss M. H. Li W. Martini D. J. et al (2018). Genomic correlates of response to immune checkpoint therapies in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Sci. (1979)359 (6377), 801–806. 10.1126/science.aan5951

38

Mitchell T. J. Turajlic S. Rowan A. Nicol D. Farmery J. H. R. O’Brien T. et al (2018). Timing the landmark events in the evolution of clear cell renal cell cancer: TRACERx renal. Cell173 (3), 611–623.e17. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.02.020

39

Nargund A. M. Pham C. G. Dong Y. Wang P. I. Osmangeyoglu H. U. Xie Y. et al (2017). The SWI/SNF protein PBRM1 restrains VHL-Loss-Driven clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Cell Rep.18 (12), 2893–2906. 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.02.074

40

Niu N. Shen X. Zhang L. Chen Y. Lu P. Yang W. et al (2023). Tumor cell-intrinsic SETD2 deficiency reprograms neutrophils to foster immune escape in pancreatic tumorigenesis. Adv. Sci.10 (2), e2202937. 10.1002/advs.202202937

41

Niu N. Shen X. Wang Z. Chen Y. Weng Y. Yu F. et al (2024). Tumor cell-intrinsic epigenetic dysregulation shapes cancer-associated fibroblasts heterogeneity to metabolically support pancreatic cancer. Cancer Cell42 (5), 869–884.e9. 10.1016/j.ccell.2024.03.005

42

Pan D. Kobayashi A. Jiang P. De Andrade L. F. Tay R. E. Luoma A. M. et al (1979). A major chromatin regulator determines resistance of tumor cells to T cell-mediated killing. Science359 (6377), 770–775. 10.1126/science.aao1710

43

Park J. S. Jang W. S. Lee M. E. Kim J. Oh K. Lee N. et al (2025). BAP1 as a predictive biomarker of therapeutic response to oncolytic vaccinia virus for metastatic renal cell carcinoma therapy. Cancer Immunol. Immunother.74 (9), 282. 10.1007/s00262-025-04139-4

44

Peña-Llopis S. Vega-Rubín-De-Celis S. Liao A. Leng N. Pavía-Jiménez A. Wang S. et al (2012). BAP1 loss defines a new class of renal cell carcinoma. Nat. Genet.44 (7), 751–759. 10.1038/ng.2323

45

Pfister S. X. Markkanen E. Jiang Y. Sarkar S. Woodcock M. Orlando G. et al (2015). Inhibiting WEE1 selectively kills histone H3K36me3-Deficient cancers by dNTP starvation. Cancer Cell28 (5), 557–568. 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.09.015

46

Rao H. Liu C. Wang A. Ma C. Xu Y. Ye T. et al (2023). SETD2 deficiency accelerates sphingomyelin accumulation and promotes the development of renal cancer. Nat. Commun.14 (1), 7572. 10.1038/s41467-023-43378-w

47

Rezende R. B. Drachenberg C. B. Kumar D. Blanchaert R. Ord R. A. Ioffe O. B. et al (1999). Differential diagnosis between monomorphic clear cell adenocarcinoma of salivary glands and renal (clear) cell carcinoma. Am. J. Surg. Pathol.23 (12), 1532–1538. 10.1097/00000478-199912000-00011

48

Ruan H. B. Han X. Li M. D. Singh J. P. Qian K. Azarhoush S. et al (2012). O-GlcNAc transferase/host cell factor C1 complex regulates gluconeogenesis by modulating PGC-1α stability. Cell Metab.16 (2), 226–237. 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.07.006

49

Shu G. Chen M. Liao W. Fu L. Lin M. Gui C. et al (2024). PABPC1L induces IDO1 to promote tryptophan metabolism and immune suppression in renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Res.84 (10), 1659–1679. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-23-2521

50

Takagi-Kimura M. Tada A. Kijima T. Kubo S. Ohmuraya M. Yoshikawa Y. (2022). BAP1 depletion in human B-lymphoblast cells affects the production of innate immune cytokines and chemokines. Genes Cells27 (12), 731–740. 10.1111/gtc.12988

51

Tang Y. Jin Y. H. Li H. L. Xin H. Chen J. D. Li X. Y. et al (2022). PBRM1 deficiency oncogenic addiction is associated with activated AKT–mTOR signalling and aerobic glycolysis in clear cell renal cell carcinoma cells. J. Cell Mol. Med.26 (14), 3837–3849. 10.1111/jcmm.17418

52

Terzo E. A. Lim A. R. Chytil A. Chiang Y. C. Farmer L. Gessner K. H. et al (2019). SETD2 loss sensitizes cells to PI3Kβ and AKT inhibition, Oncotarget10, 647, 659. 10.18632/oncotarget.26567

53

Turajlic S. Xu H. Litchfield K. Rowan A. Chambers T. Lopez J. I. et al (2018a). Tracking cancer evolution reveals constrained routes to metastases: TRACERx renal. Cell173 (3), 581–594.e12. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.057

54

Turajlic S. Xu H. Litchfield K. Rowan A. Horswell S. Chambers T. et al (2018b). Deterministic evolutionary trajectories influence primary tumor growth: TRACERx renal. Cell173 (3), 595–610.e11. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.043

55

Varela I. Tarpey P. Raine K. Huang D. Ong C. K. Stephens P. et al (2011). Exome sequencing identifies frequent mutation of the SWI/SNF complex gene PBRM1 in renal carcinoma. Nature469 (7331), 539–542. 10.1038/nature09639

56

Walter D. M. Gladstein A. C. Doerig K. R. Natesan R. Baskaran S. G. Gudiel A. A. et al (2023). Setd2 inactivation sensitizes lung adenocarcinoma to inhibitors of oxidative respiration and mTORC1 signaling. Commun. Biol.6 (1), 255. 10.1038/s42003-023-04618-3

57

Wang T. Lu R. Kapur P. Jaiswal B. S. Hannan R. Zhang Z. et al (2018). An empirical approach leveraging tumorgrafts to dissect the tumor microenvironment in renal cell carcinoma identifies missing link to prognostic inflammatory factors. Cancer Discov.8 (9), 1142–1155. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-17-1246

58

Wettersten H. I. Aboud O. A. Lara P. N. Weiss R. H. (2017). Metabolic reprogramming in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Nephrol.13, 410–419. 10.1038/nrneph.2017.59

59

Xu D. Gao Y. Yang H. Spils M. Marti T. M. Losmanová T. et al (2024). BAP1 deficiency inflames the tumor immune microenvironment and is a candidate biomarker for immunotherapy response in malignant pleural mesothelioma. JTO Clin. Res. Rep.5 (5), 100672. 10.1016/j.jtocrr.2024.100672

60

Young M. Jackson-Spence F. Beltran L. Day E. Suarez C. Bex A. et al (2024). Renal cell carcinoma. Lancet404 (10451), 476–491. 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00917-6

61

Yu H. Mashtalir N. Daou S. Hammond-Martel I. Ross J. Sui G. et al (2010). The ubiquitin carboxyl hydrolase BAP1 forms a ternary complex with YY1 and HCF-1 and is a critical regulator of gene expression. Mol. Cell Biol.30 (21), 5071–5085. 10.1128/mcb.00396-10

62

Zhang Y. Shi J. Liu X. Feng L. Gong Z. Koppula P. et al (2018). BAP1 links metabolic regulation of ferroptosis to tumour suppression. Nat. Cell Biol.20 (10), 1181–1192. 10.1038/s41556-018-0178-0

63

Zhang L. Wang J. Liu X. Xiao X. Liu Y. Huang Q. et al (2024). Regulation of SETD2 maintains immune regulatory function in macrophages to suppress airway allergy. Immunology173 (1), 185–195. 10.1111/imm.13823

64

Zheng X. Luo Y. Xiong Y. Liu X. Zeng C. Lu X. et al (2023). Tumor cell-intrinsic SETD2 inactivation sensitizes cancer cells to immune checkpoint blockade through the NR2F1-STAT1 pathway. J. Immunother. Cancer11 (12), e007678. 10.1136/jitc-2023-007678

Summary

Keywords

ccRCC, PBRM1, SETD2, BAP1, VHL, metabolism, tumor microenvironment

Citation

Johnson M and Turcotte S (2026) The fall of the genome protectors triad: PBRM1, SETD2, and BAP1’s impact on metabolism and immunity in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 13:1713830. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2025.1713830

Received

26 September 2025

Revised

25 November 2025

Accepted

29 December 2025

Published

12 January 2026

Volume

13 - 2025

Edited by

Wen Xiao, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, China

Reviewed by

Chengjian Ji, Nanjing Medical University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Johnson and Turcotte.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sandra Turcotte, sandra.turcotte@umoncton.ca

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.