Abstract

Introduction:

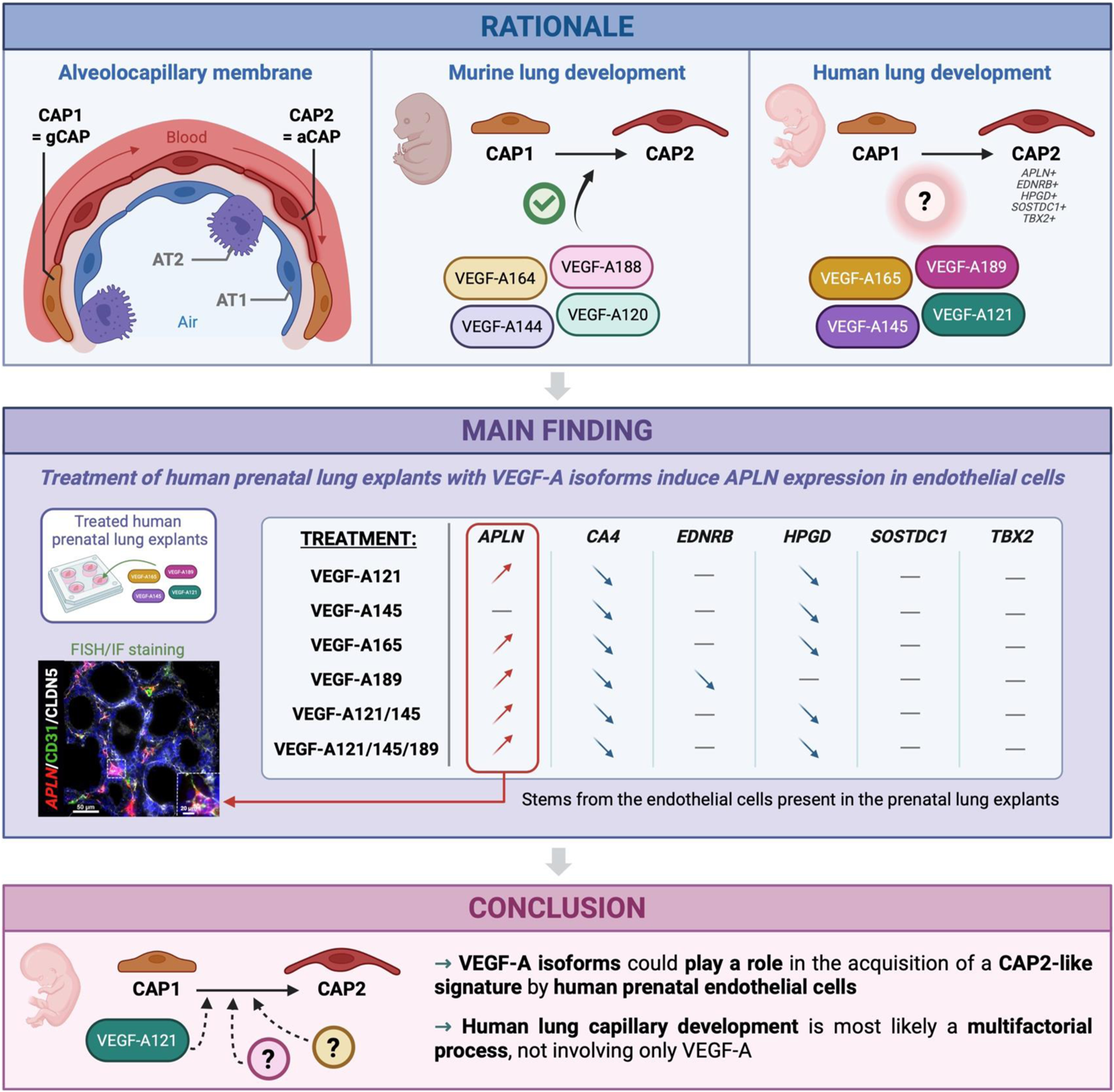

Single-cell RNA-sequencing analyses have revealed the existence of two distinct capillary cell populations in the human lung: general capillary cells (CAP1) and alveolar capillary cells (CAP2). Studies in mouse have shown that the splicing of Vegf-a evolves during embryonic development, creating a temporal pattern of expression for different isoforms, which contributes to the formation of pulmonary capillaries. Moreover, it was demonstrated that murine Vegf-a188 isoform promotes the emergence of CAP2 in vitro. Human homologs of these VEGF-A isoforms exist; however, their role in this process remains elusive. This study investigates the role of VEGF-A and its isoforms in the differentiation of lung capillaries during human prenatal development.

Methods:

A cohort of human prenatal tissues, aged from the late pseudoglandular to early canalicular stages of development (10–20 weeks of gestation), was used to study the emergence of CAP2 markers (TBX2, SOSTDC1, EDNRB, HPGD, APLN) in correlation with the expression of the different VEGF-A isoforms (VEGF-A121, VEGF-A145, VEGF-A165, VEGF-A189).

Results:

RT-qPCR analyses revealed a simultaneous expression of certain VEGF-A isoforms with several CAP2 markers, which peaked at around 18–20 weeks of gestation. Human prenatal lung explants were then treated with recombinant proteins of the different VEGF-A isoforms to study their impact on EC proliferation, as well as on the expression of CAP2 markers. While most of the isoforms did not impact EC proliferation, except for VEGF-A189 which downregulated it, almost all of them upregulated the expression of APLN, a major CAP2 marker. By using fluorescence in situ hybridization, we showed that this increase of expression was specific to the ECs. However, most of the isoforms induced a downregulation of EDNRB and HPGD. They also did not impact the expression of SOSTDC1 and TBX2.

Discussion:

Our study shows that the different VEGF-A isoforms do not have the same effect on human lung capillary differentiation as those observed with their homologs in mice, highlighting the importance of studying this process in the human model. Moreover, while it demonstrated that VEGF-A isoforms can induce APLN expression in ECs, it also revealed that CAP2 differentiation is most likely a multifactorial process, not only involving VEGF-A.

Graphical Abstract

1 Introduction

Lung capillaries, in association with alveolar epithelial cells, comprise the functional gas exchange unit of the respiratory system. It was recently described that the endothelium of lung capillaries is composed of two distinct endothelial cell types: general capillary endothelial cells/CAP1 and alveolar capillary endothelial cells/aerocytes/CAP2 (Gillich et al., 2020). CAP1 are widely distributed and act as progenitors for CAP2 during homeostasis and tissue repair, whereas CAP2 cells are lung-specific and specialized for gas exchange and leukocyte trafficking (Gillich et al., 2020).

During embryonic development, CAP1 are primarily located in a vascular plexus. The transformation of this plexus, through the differentiation of CAP1 into CAP2, leads to the development of the alveolar capillary network. In mouse, CAP2 emerge at embryonic day E17.5 and are characterized by their extensively fenestrated structure (Gillich et al., 2020). Their number increase gradually during prenatal development but expand exponentially after birth, when they acquire a mature CAP2 transcriptional signature and phenotype (Gillich et al., 2020; Vila et al., 2020).

Several RNA sequencing studies have revealed distinct molecular signatures of CAP1 and CAP2 between mouse and human. Murine CAP1 are characterized by a high expression of Plvap, Cd93, Ptprb, or Aplnr, whereas human CAP1 are mainly defined by APLNR, FCN3, EDN1, SLC6A4 or VWF (Gillich et al., 2020; Schupp et al., 2021; Cantu et al., 2023). These molecular differences are also found in CAP2. While murine CAP2 are molecularly defined by Car4, Ednrb, Tbx2, Apln, Fibin; human CAP2 are primarily characterized by APLN, HPGD, EDNRB, SOSTDC1, ADIRF, and S100A4. The bidirectional signaling between APLN (ligand) from CAP2 cells with APLNR (receptor) present on CAP1 cell surface is particularly noteworthy as it clearly demonstrates communication between the two populations and their role in maintaining pulmonary capillary homeostasis and function. Furthermore, although Car4 is considered as a specific CAP2 marker in mouse, its human homolog CA4 is considered a common EC marker (Gillich et al., 2020; Schupp et al., 2021; Cantu et al., 2023).

Vegf-a signaling has been identified as a critical pathway for the differentiation and maintenance of CAP2 cells mice. VEGF-A is a growth factor expressed by various cell types and involved in cell migration, proliferation and differentiation, resulting in neovascularization and angiogenesis (Shibuya and Claesson-Welsh, 2006; Tuder and Yun, 2008; Kumar and Ryan, 2004). Notably, the deletion of murine Vegf-a results in a depletion of CAP2 cells without affecting CAP1 number (Vila et al., 2020; Trimm and Red-Horse, 2022).

Murine Vegf-a possesses 8 exons and undergoes alternative splicing, giving rise to several isoforms (Vegf-a120, Vegf-a144, Vegf-a164, Vegf-a188 and Vegf-a205). The most common Vegf-a isoform, expressed between E11.5 and E15.5 in the mouse lung, is Vegf-a164, followed by Vegf-a188 and Vegf-a120, whereas Vegf-a188 is more expressed than Vegf-a164 in the adult mice lung (Healy et al., 2000). It has also been described that deletion of Vegf-a164 and -188 isoforms impairs lung microvascular development and delays airspace maturation, demonstrating the importance of these VEGF-A isoforms in normal lung development (Galambos et al., 2002). Moreover, treatment of mouse lung explants with Vegf-a188 increases the number of Car4-positive endothelial cells (mouse CAP2 cells), confirming its importance in murine CAP2 differentiation (Fidalgo et al., 2022). In humans, VEGF-A isoforms retain the same exon arrangement as in mice but have a different nomenclature associated with the addition of an amino acid (i.e., the human equivalent of murine Vegf-a164 is VEGF-A165) (Arcondéguy et al., 2013; Mamer et al., 2020).

While VEGF-A signaling is critical in the establishment and differentiation of murine CAP2, its role in the human developing lung capillary network remains elusive. The substantial differences in molecular signatures and functional roles between human and murine CAP2 raise questions about whether their differentiation relies on the same signaling pathways. In this study, we aim to investigate the role of VEGF-A and its isoforms in human prenatal lung capillary development and in CAP2 differentiation.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Human prenatal tissues

The human prenatal lung tissues used in this study (Supplementary Table S1) were collected under IRB approval (The Lundquist Institute 18CR-32223-01) and provided to the lab by the University of Washington Birth Defects Research Laboratory. Specimens were de-identified with the only information collected being gestational age (GA) from 10 to 20 weeks, sex and the presence of any known genetic or structural abnormalities. Informed consent was provided for each sample used in this study.

2.2 Human prenatal lung explant culture

Explants were cut from the distal part of human prenatal lungs at 250 µm using the McIlwain tissue chopper. Characteristics of the tissues used to obtain the explants are summarized in Table 1. Lung explants were cultured on Whatman nucleopore polycarbonate membranes (8 μm pore size, cat number #10417501, Cytiva) in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium/Nutriment Mixture F-12 (DMEM-F12, cat#11-320-082, Gibco) supplemented with 1% of Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS, cat#10082147, Gibco) and 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin (10,000 U/mL, cat#15-140-122, Gibco), and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2. The human lung explants were treated with recombinant human VEGF-A (rhVEGF-A) isoforms either individually (VEGF-A121, VEGF-A145, VEGF-A165, VEGF-A189) or in defined combinations (VEGF-A121 + VEGF-A145, and VEGF-A121 + VEGF-A145 + VEGF-A189), with untreated explants serving as the negative control. Each treatment was refreshed every 24 h over a 48-h culture period. The rhVEGF-A isoforms come from R&D system (VEGF-A121: cat#4644-VS-010, VEGF-A145: cat#7626-VE-010, VEGF-A165: cat#293-VE-010, VEGF-A189: cat#8147-VE-025). Considering the supplier information about the median effective dose, we selected 30 ng/mL, 20 ng/mL, and 80 ng/mL, respectively, for VEGF-A121, VEGF-A165, and VEGF-A145/VEGF-A189. Explants were subsequently collected for gene expression analysis or immunofluorescent staining. For each biological sample, we collected enough explants to complete the full experimental design: 14 explants per sample. These were divided into two sets for each of the seven treatment conditions: one set designated for RNA analysis and the other for histology and immunofluorescence.

TABLE 1

| Sample Identifier | Sex | GA |

|---|---|---|

| H29501 | M | 16.3 |

| H29316 | F | 16.4 |

| H29412 | F | 16.4 |

| H29419 | F | 16.4 |

| H29682 | F | 17 |

| H29342 | M | 17.4 |

| H29324 | M | 17.7 |

| H29410 | F | 17.7 |

| H29645 | M | 17.7 |

| H29647 | M | 17.7 |

| H29284 | M | 19.1 |

| H29321 | F | 19.3 |

| H29298 | M | 20.9 |

| H29650 | M | 21.6 |

Characteristics of the human prenatal lung tissues used to obtain explants. None of the tissues presented with genetic or structural abnormalities. GA: gestational age.

2.3 RNA extraction and RT-qPCR analysis

RNA from native human prenatal lungs ranging from the late pseudoglandular (10–15 weeks of GA, n = 24) to the early canalicular (16–20 weeks of GA, n = 28) stages of development, as well as from treated lung explants (n = 14), was extracted using easy-spinTM Total RNA Extraction kit from iNtRON Biotechnology (cat#17221) based on the manufacturer’s protocol. cDNA synthesis was performed using the Tetro cDNA Synthesis Kit (Meridian Bioscience, BIO-65043). Gene expression analysis was performed in triplicate for each sample, using human-specific TaqMan gene expression assays (Table 2) and the TaqMan Fast Advanced Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, cat#4444557). For the different VEGF-A isoforms, we designed and validated primers, and probes were custom-made by ThermoFisher (Table 2). Product amplification was performed using the QuantStudio 3 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). Relative gene expression was established using GAPDH as the housekeeping gene.

TABLE 2

| Target gene | Taqman assay or custom sequences |

|---|---|

| Universal capillary marker | |

| CA4 | Hs00426343_m1 |

| CAP marker primer | |

| APLN | Hs00175572_m1 |

| EDNRB | Hs00240747_m1 |

| HPGD | Hs00960586_m1 |

| SOSTDC1 | Hs00383602_m1 |

| TBX2 | Hs00911929_m1 |

| VEGF-A | |

| VEGF-Atot | Hs00900055_m1 |

| VEGF-A121 | Forward: 5′-AATGTGAATGCAGACCAAAGAAAG-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′-ACCCTGAGGGAGGCTCCTT-3′ | |

| Probe: 5′-6FAM-AGACAAGAAAAATGTGACAAGC-MGBNFQ-3′ | |

| VEGF-A145 | Forward: 5′-CGCAAGAAATCCCGGTATAAGT-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′-ACCCTGAGGGAGGCTCCTT-3′ | |

| Probe: 5′-6FAM-CTGGAGCGTTTGTGACAAGC-MGBNFQ-3′ | |

| VEGF-A165 | Forward: 5′-GTGAATGCAGACCAAAGAAAGATAGA-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′-CCTTGCAACGCGAGTCTGT-3′ | |

| Probe: 5′-6FAM-CAAGACAAGAAAATCCCTGTGG-MGBNFQ-3′ | |

| VEGF-A189 | Forward: 5′-CGCAAGAAATCCCGGTATAAGTC-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′-CGCGAGTCTGTGTTTTTGCA-3′ | |

| Probe: 5′-6FAM-CTGGAGCGTTCCCTGTG-MGBNFQ-3′ | |

| Housekeeping gene | |

| GAPDH | Hs02786624_g1 |

Taqman assays and custom-made primers and probes used for RT-qPCR.

2.4 Explants embedding and sectioning

Cultured explants were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature. Tissues were then dehydrated in an increasing series of ethanol concentrations, cleared in xylene, and embedded in paraffin. For ulterior analyses, formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) prenatal lung explants were cut in 5 μm sections using a microtome.

2.5 Hematoxylin and eosin staining

Sections were deparaffinized with xylene and rehydrated by a decreasing series of ethanol concentrations as previously described (Danopoulos et al., 2016). The sections were stained with Hematoxylin+ (Fisher HealthcareTM, 22-220-100) for 5 min, rinsed with distilled water for 5 min then stained with Eosin (Fisher HealthcareTM, 22-220-104) for 5 min. Tissues were then dehydrated by gradient ethanol solutions and cleared with xylene. The sections were assembled with DPX mounting medium (BDH, 360294H) and Corning cover glass (Corning, 2980-225).

2.6 Immunofluorescence (IF) staining

Lung explants were processed for immunofluorescent staining as previously described (Danopoulos et al., 2016). Briefly, after rehydrating, sections were blocked in 3% Bovine Serum Albumin, 10% normal goat serum, 0.1% Triton-X100 in TBS for 2 h. They were then incubated with the appropriate primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C in a humid chamber (Table 3). The next day, the slides were washed in TBST and incubated with appropriate secondary antibodies supplemented with DAPI for 1 h at RT. Slides were then mounted under a coverslip with ProlongTM Gold Antifade Mountant (Invitrogen, P36934).

TABLE 3

| Primary antibodies | Sources | Identifier | Dilution |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD31 | Thermo Fisher | MA5-13188 | 1/100 |

| Claudin-5 | LSBio | LS-C352946 | 1/200 |

| Ki67 | Epredia | RM-9106-S1 | 1/200 |

| DAPI | Abcam | AB228549 | 1/1000 |

| RNAscope assay | |||

| APLN-C3 | ACDB | 44–9971-C3 | 1/50 |

| Secondary antibodies | |||

| AlexaFluor 647 | Jackson Immuno Research | 115-606-104 | 1/500 |

| AlexaFluor 488 | Jackson Immuno Research | 115-546-144 | 1/500 |

| Opal 570 | Akoya BioSciences | OP-001003 | 1/500 |

| Cy3 | Jackson Immuno Research | 115-166-146 | 1/500 |

Antibodies and RNAscope probe used for fluorescent immunostaining and RNA in situ hybridization.

2.7 RNA fluorescent in situ hybridization coupled with IF

Fluorescent In Situ Hybridization (FISH) was conducted on 5 μm lung explant sections as previously described (Danopoulos et al., 2020), using the Advanced Cell Diagnostics RNAscope Fluorescent Multiplex Assay (Cat# 323110) per the manufacturer’s instructions. The probes were obtained from ACDBio, the signal was revealed with the Opal 570 (Table 3). Following FISH protocol, combinatorial IF staining was performed as previously described (Danopoulos et al., 2023).

2.8 Imaging and quantification

Ten pictures were captured at x40 objective on the Leica Thunder Imager DMi8 and quantified using HALO® Image Analysis Platform (version 3.6.4134, Highplex FL and FISH IF modules, Indica Labs, Inc; Albuquerque, NM).

2.9 Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, United States). Data normality was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. If the assumptions for parametric testing were met, comparisons between two groups were performed using a paired or unpaired t-test, as appropriate. For comparisons involving multiple groups relative to the untreated control, a repeated-measures one-way ANOVA was used, with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test applied to adjust P values. If the assumptions for parametric testing were not met, a Wilcoxon matched-pairs test was used for two-group comparisons, and a Friedman test was applied for repeated-measures multiple-group comparisons, with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test used for adjustment. Statistical significance was defined as p ≤ 0.05.

A graphical of the experimental design of each step of the methodology described above is represented in Supplementary Figure S1.

3 Results

3.1 Expression of CAP2 cell markers and VEGF-A121, -145, −189 start peaking simultaneously during human lung development

The emergence of CAP2 in the human lung remains poorly described. Several groups have previously reported that CAP2 cells appear at around 18–21 weeks of gestation in the developing human lung (Gillich et al., 2020; He et al., 2022; Zepp et al., 2021; Bhattacharya et al., 2025). However, given the limitation of these datasets from single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq), we explored this further. Using RT-qPCR, gene expression for CAP2 markers (SOSTDC1, HPGD, EDNRB, APLN and TBX2) were analyzed in native prenatal lung tissues aged from 10 to 20 weeks of GA, corresponding to the transition from the late pseudoglandular to early canalicular stages of lung development (Figure 1). Additionally, the expression level of CA4 was also investigated, given its role as a CAP2 marker within the mouse lung, although it has been demonstrated to be a ubiquitous capillary marker within the human lung (Fleming et al., 1993). Interestingly, we noted that SOSTDC1 increased significantly in two phases: first at 14 weeks (week 14: 0.01925 ± 0.004233, n = 10 vs. week 10: 0.0089 ± 0.001728, n = 8, p = 0.0168), and then again at 18 weeks (week 18: 0.04914 ± 0.01575, n = 9, p = 0.0055). HPGD expression started increasing significantly at 16 weeks (week 16: 0.02954 ± 0.005425, n = 9 vs. week 10: 0.01505 ± 0.002786, n = 8, p = 0.0372), whereas EDNRB demonstrated significantly increased expression starting at 18 weeks (week 18: 0.1661 ± 0.03757, n = 9 vs. week 10: 0.04244 ± 0.009032, n = 8, p = 0.0085). Moreover, we observed an upward trend in the expression of CA4 at week 20 (week 20: 0.04885 ± 0.01083, n = 8 vs. week 10: 0.02343 ± 0.004332, n = 8, p = 0.055). In contrast, APLN and TBX2 expression remained constant throughout the gestational ages.

FIGURE 1

Expression of CAP markers and VEGF-A isoforms during human prenatal lung development. RT-qPCR analysis of the expression of universal capillary marker CA4 and CAP2 specific markers (SOSTDC1, HPGD, EDNRB, CA4, APLN, and TBX2) (A) and of total VEGF-A (VEGF-Atot) as well as each VEGF-A isoform (VEGF-A121, VEGF-A145, VEGF-A165, VEGF-A189) (B) in native human prenatal lungs aged from the late pseudoglandular to the early canalicular stages of development (week 10–20 of GA). Results are shown as a dot plot with mean ± SEM, n = 8–10, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. (C) Visual summary of the VEGF-A isoforms and CAP2 markers expression during human prenatal lung development. Image created by Biorender.com.

Having established the expression of several CAP2 markers throughout lung development, we next investigated the potential implication of VEGF-A in CAP2 differentiation. Therefore, we analyzed the expression of VEGF-A in the native human prenatal lung samples using RT-qPCR (Figure 1B) and noted significantly increased expression of total VEGF-A (VEGF-Atot) at 20 weeks of GA as compared to 10 weeks (week 20: 0.2426 ± 0.03788, n = 9 vs. week 10: 0.1202 ± 0.02455, n = 8, p = 0.0187). To better evaluate the implication of each isoform, we designed and validated primers and probes for VEGF-A121, -145, -165 and -189. We observed an increase of VEGF-A121 expression throughout the weeks, which started becoming significant at 20 weeks (week 20: 0.3943 ± 0.03885, n = 9 vs. week 10: 0.1440 ± 0.03749, n = 8, p = 0.0003). Similarly, at 20 weeks of GA, we noted significantly increased expression of VEGF-A189 (week 20: 0.2935 ± 0.06408, n = 9 vs. week 10: 0.06349 ± 0.01541, n = 8, p = 0.0049) as well as an upward trend for VEGF-A145 (week 20: 0.02684 ± 0.008570, n = 9 vs. week 10: 0.005533 ± 0.002014, n = 6, p = 0.0879). However, VEGF-A165 expression did not change over time.

Altogether, these results indicate a simultaneous increase of expression of VEGF-A121, -145, and -189 isoforms with several CAP2 markers (SOSTDC1, EDNRB, HPGD), peaking at around 18–20 weeks of GA (Figure 1C). Therefore, all subsequent experiments are performed using lung tissues at or older than 16 weeks of gestation.

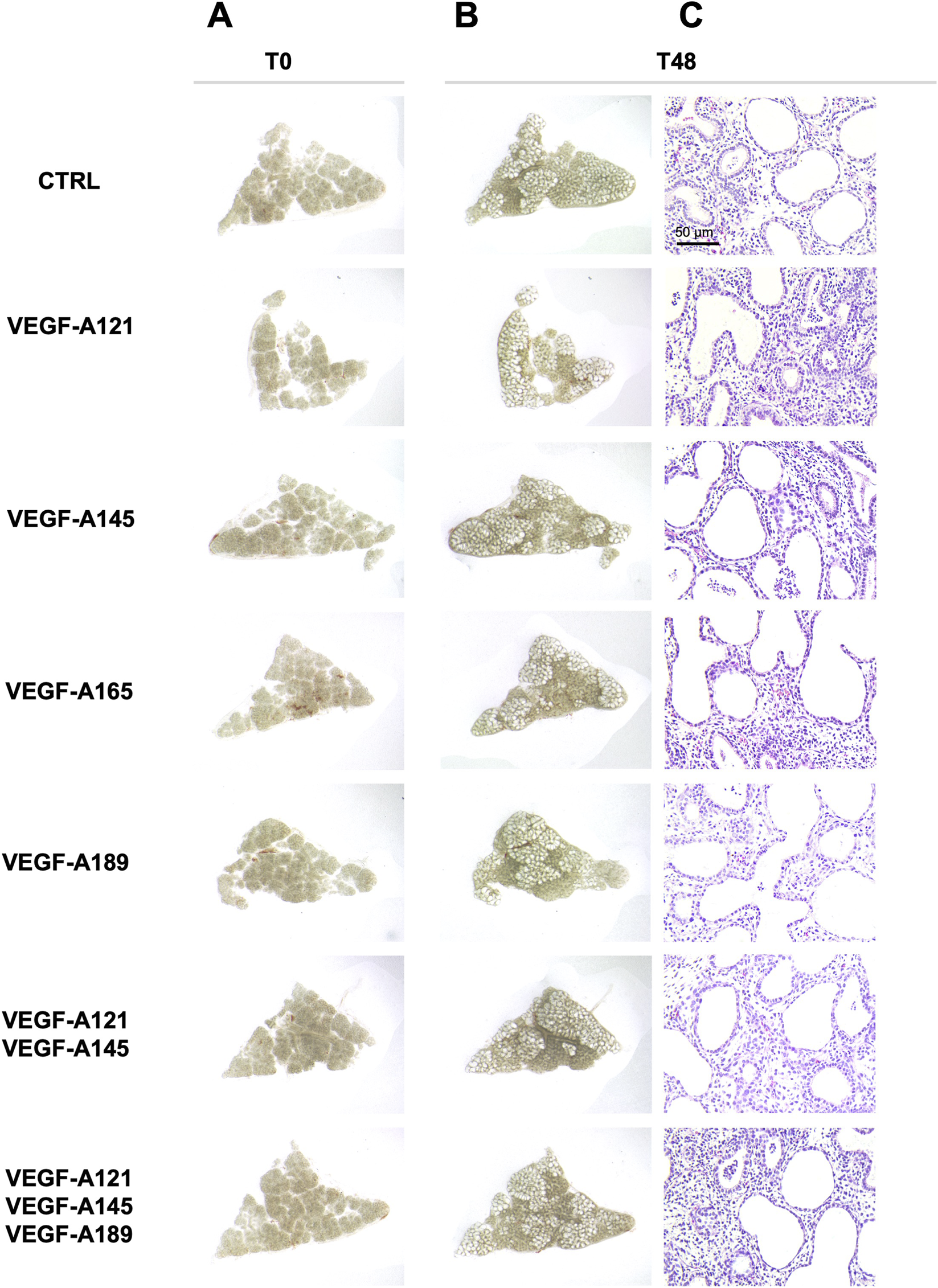

3.2 VEGF-A189 affects endothelial cell proliferation

Given the simultaneous expression of several VEGF-A isoforms with some CAP2 markers in the human prenatal lung tissues, it is possible that the different VEGF-A isoforms could be involved in CAP2 differentiation during human lung development. To verify this hypothesis, we treated human prenatal lung explants (starting at 16 weeks of GA) with exogenous recombinant human VEGF-A isoforms for 48 h (Figure 2). The different VEGF-A isoforms were either used alone or in combinations (VEGF-A121, -145 and/or −189) to explore whether a cumulative effect of several isoforms could be observed. We aimed to explore whether the different VEGF-A isoform treatments altered the normal growth of the lung explants. Explant morphology was observed at baseline (time 0; Figure 2A) and after 48 h of treatment (Figure 2B). No difference was determined in the overall aspect of the treated explants compared to the non-treated explants after 48 h (Figure 2B). Moreover, hematoxylin-eosin staining of the prenatal lung explants treated with VEGF-A isoforms displayed no visual histological difference when compared to the non-treated explants (Figure 2C).

FIGURE 2

Effect of VEGF-A isoforms on human prenatal lung explant morphology. Representative pictures of the human prenatal lung explant cultures, either untreated or treated with the different VEGF-A isoforms alone or in combinations (VEGF-A121, VEGF-A145, VEGF-A165, VEGF-A189, VEGF-A121-145, and VEGF-A121-145–189) for 48 h. Photos were taken at time 0 (left, (A) and at 48 h (right, (B). At 48 h, hematoxylin-eosin staining was performed to evaluate the histology of the explants (C). Scale bar indicated by 50 µm.

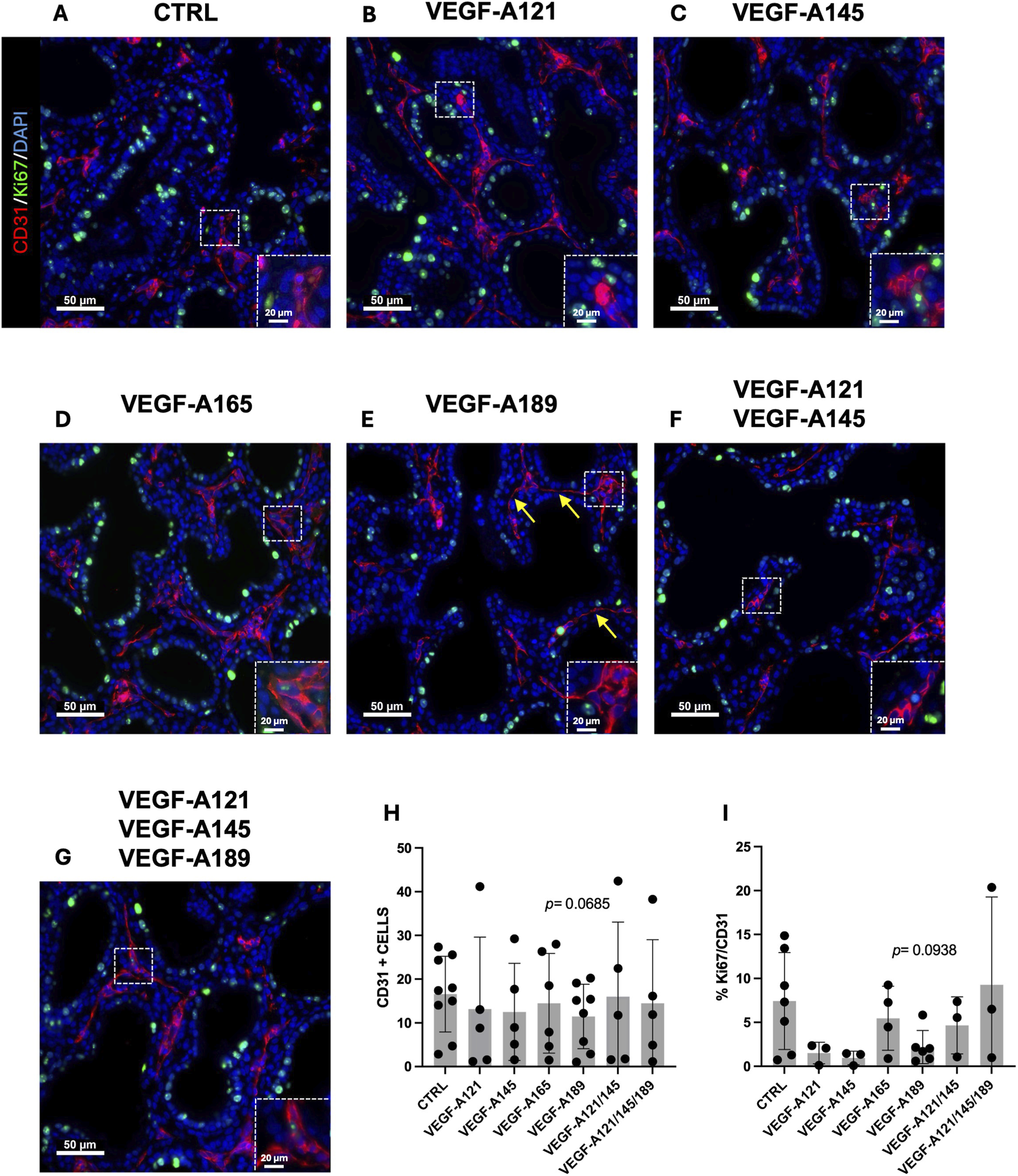

We next aimed to investigate cellular-level alterations by examining how treatment influenced capillary proliferation. This was of interest given that CAP2 are considered to be highly differentiated and specialized cells, with limited to no proliferative capacity, whereas CAP1 are more associated as being the proliferative progenitor cells (Wong et al., 2024). We therefore performed a CD31 (PECAM-1) and Ki67 IF staining on all treatment conditions (Figures 3A–G) to explore the impact of the different VEGF-A isoforms on the number (Figure 3H) and proliferative capacity of the ECs (Figure 3I). Our data showed no difference in the number of CD31-positive cells when the explants were treated with VEGF-A121 (Figure 3B), VEGF-A145 (Figure 3C), VEGF-A165 (Figure 3D), or combined treatments VEGF-A121-145-189 (Figure 3G). However, a trend towards a reduced number of CD31-positive cells was observed in VEGF-A189 treated explants (11.48 ± 2.608, n = 6, p = 0.0685) (Figures 3E,H). Furthermore, VEGF-A189 was the only treatment that trended towards altering the proportion of proliferating ECs, displaying a decrease in the percentage of Ki67/CD31 double-positive cells compared to the control (VEGF-A189: 2.196 ± 0.7729, n = 6, p = 0.0938) (Figure 3I). This treatment also resulted in the ECs presenting with a more elongated and flattened morphology, as indicated by the yellow arrows in Figure 3E. The only other treatment that trended towards decreased EC proliferation was VEGF-A145 (VEGF-A145: 0.9595 ± 0.4462, n = 3, p = 0.1867).

FIGURE 3

Impact of VEGF-A isoforms on endothelial cell proliferation in human prenatal lung explants. (A–G) Representative pictures of human prenatal lung explants, aged from the late pseudoglandular to the early canalicular stage (16–21 weeks of GA), untreated (A) or treated with VEGF-A121 (B), VEGF-A145 (C), VEGF-A165 (D), VEGF-A189 (E), VEGF-A121-145 (F) or VEGF-A121-145-189 (G) for 48 h, stained for CD31 (red) and Ki67 (green) by IF. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). (H,I) Associated quantification of the number of CD31-positive cells (H) and the percentage of Ki67-CD31double-positive cells (I). Results are shown as a dot plot with mean ± SEM, n = 3–9. Scale bar indicated by 50 µm.

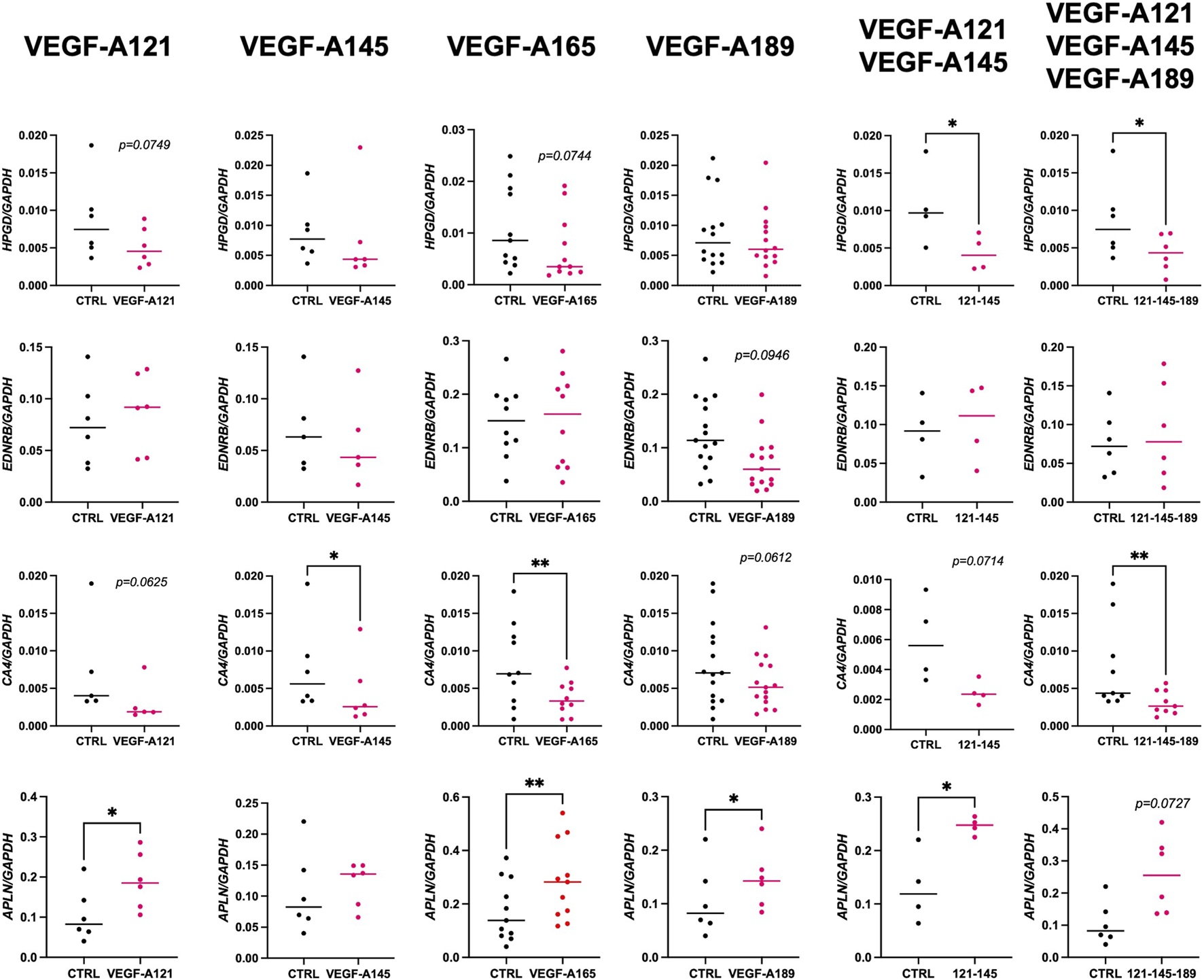

3.3 VEGF-A isoforms are implicated in the CAP2-like cell signature

Although there were no stark morphological differences within the endothelium of the VEGF-A treated explants, we want to understand if perhaps endothelial cell signature was being altered, suggesting a shift towards the establishment of CAP2 cells. Therefore, we next examined the expression of several CAP2 markers (EDNRB, HPGD, CA4, and APLN in Figure 4; SOSTDC1 and TBX2 in Supplementary Figure S2) on the different VEGF-A treated explants from 16 to 21 weeks of GA.

FIGURE 4

Impact of VEGF-A isoforms on the expression of CAP2 markers in human prenatal lung explants. RT-qPCR analysis of the expression of CAP2 markers (HPGD, EDNRB, CA4, and APLN) in human prenatal lung explants aged from the late pseudoglandular to the early canalicular stage (16–21 weeks of GA), untreated or treated with the different VEGF-A isoforms alone or in combinations (VEGF-A121, VEGF-A145, VEGF-A165, VEGF-A189, VEGF-A121-145, and VEGF-A121-145–189) for 48 h. Results are shown as a dot plot with mean ± SEM, n = 4–15, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Overall, SOSTDC1, HPGD, and CA4 expression levels were much lower than those of APLN, EDNRB, and TBX2, suggesting their role may not be as critical at this stage of development. None of the VEGF-A isoforms seemed to affect SOSTDC1 and TBX2 expression (Supplementary Figure S2). Alternatively, our data showed that VEGF-A isoforms may affect HPGD, EDNRB, CA4, and APLN expression. Treatments with VEGF-A121 and -165 isoforms alone demonstrated a downward trend in HPGD expression (VEGF-A121: 0.005114 ± 0.001072, n = 6, p = 0.0749; VEGF-A165: 0.007025 ± 0.001914, n = 11, p = 0.0744; VEGF-A145: 0.007554 ± 0.003142, n = 6, p = 0.4375). Combinations of VEGF-A121-145 and VEGF-A121-145-189 even significantly decreased HPGD expression (VEGF-A121-145: 0.004350 ± 0.001187, n = 4, p = 0.0393; VEGF-A121-145-189: 0.004304 ± 0.001005, n = 8, p = 0.0289). In contrast, VEGF-A189 induced no difference in HPGD expression (VEGF-A189: 0.007545 ± 0.001292, n = 14, p = 0.6698) but the only VEGF-A isoform to alter EDNRB expression was VEGF-A189, resulting in a decrease (0.07211 ± 0.01306, n = 15, p = 0.0946). Furthermore, VEGF-A121, -189, and 121-145 treatments induced a downward trend in CA4 expression while VEGF-A145, -165 and 121-145-165 significantly decreased CA4 expression (VEGF-A121: 0.003074 ± 0.001193, n = 5, p = 0.0625; VEGF-A145: 0.12 ± 0.001821, n = 6, p = 0.0312; VEGF-A165: 0.003730 ± 0.0006941, n = 10, p = 0.0045; VEGF-A189: 0.005723 ± 0.00085, n = 15, p = 0.0612; VEGF-A121-145: 0.002471 ± 0.0003921, n = 4, p = 0.0714; VEGF-A121-145-189: 0.003136 ± 0.0005311, n = 9, p = 0.0039). However, and most interestingly, all VEGF-A isoforms (except for VEGF-A145) induced a strong upward trend or even significantly increased APLN expression (VEGF-A121: 0.1906 ± 0.02878, n = 6, p = 0.0153; VEGF-A145: 0.1204 ± 0.01438, n = 6, p = 04,813; VEGF-A165: 0.2862 ± 0.04385, n = 11, p = 0.0011; VEGF-A189: 0.1454 ± 0.02257, n = 6, p = 0.0215; VEGF-A121-145: 0.2460 ± 0.008221, n = 4, p = 0.0352; VEGF-A121-145-189: 0.2575 ± 0.04870, n = 6, p = 0.0727).

3.4 VEGF-A isoforms induce APLN expression in endothelial cells

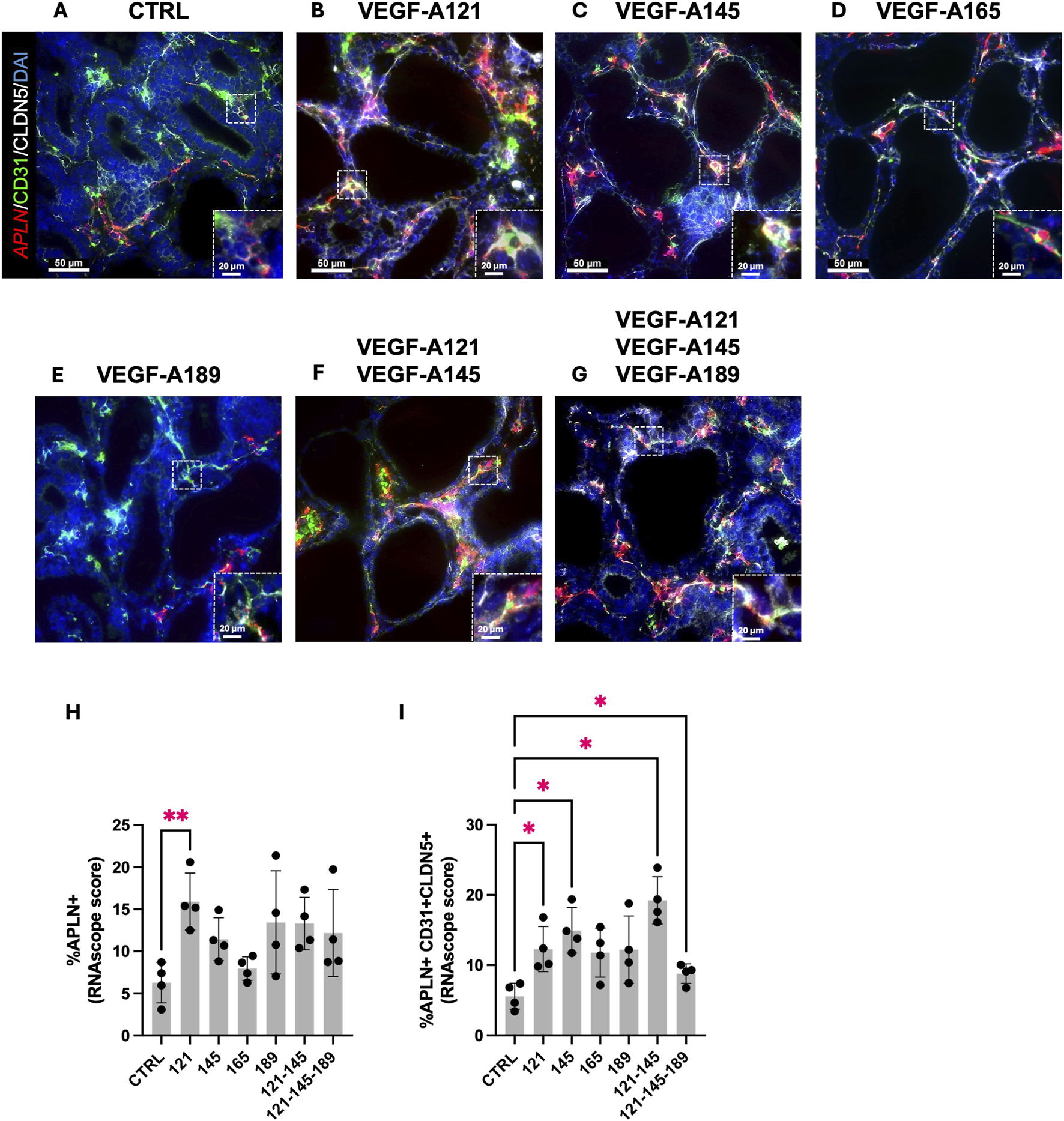

To investigate whether this increase in APLN expression stems from ECs, we performed an RNA in situ hybridization for APLN RNA transcripts in combination with CD31 and CLDN5 IF staining, on the human prenatal lung explants treated with the different VEGF-A isoforms (Figures 5A–G; Supplementary Figure S3). VEGF-A121 alone was the only treatment to significantly increase the percentage of APLN + cells in the explants (VEGF-A121: 15.92 ± 1.694, n = 4, p = 0.0019) (Figure 5H). However, we observed a significant increase in the percentage of APLN + -CD31+-CLDN5+ cells in the explants treated with VEGF-A121, -145, -121-145, or -121-145–189 (Figure 5I). Those treated with VEGF-A165 or VEGF-A189 solely demonstrated an increasing trend (VEGF-A121: 12.30 ± 1.607, n = 4, p = 0.0291; VEGF-A145: 14.94 ± 1.620, n = 4, p = 0.0282; VEGF-A165: 11.80 ± 1.750, n = 4, p = 0.1715; VEGF-A189: 12.21 ± 2.400, n = 4, p = 0.3091; VEGF-A121-145: 19.25 ± 1.687, n = 4, p = 0.0289; VEGF-A121-145-189: 8.800 ± 0.6996, n = 4, p = 0.0267). These results indicate that the increase of APLN expression in the treated prenatal lung explants previously observed through RT-qPCR analysis, is most likely localized to the ECs.

FIGURE 5

VEGF-A isoforms induce APLN expression in endothelial cells. (A–G) Representative pictures of human prenatal lung explants, aged from the late pseudoglandular to the early canalicular stage (16–21 weeks of GA), untreated (A) or treated with VEGF-A121 (B), VEGF-A145 (C), VEGF-A165 (D), VEGF-A189 (E), VEGF-A121-145 (F) or VEGF-A121-145-189 (G) for 48 h, stained for CD31 (green) and Claudin-5 (white) by IF, and for APLN (red) by FISH. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). (H,I) Associated quantification of the percentage of APLN + cells (H) and the percentage of APLN+ CD31+ CLDN5+ cells (I). Results are shown as a dot plot with mean ± SEM, n = 4, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. Scale bar indicated by 50 µm.

4 Discussion

This work aimed to investigate the implication of VEGF-A and its different isoforms in CAP2 cells differentiation during human lung development. It was previously demonstrated in the mouse that Vegf-a188 increases the percentage of CAR4-positive ECs (Fidalgo et al., 2022) and we therefore hypothesized that VEGF-A isoforms also might be involved in human CAP2 differentiation.

The role of VEGF-A signaling in the developing human lung was first supported by a positive correlation between the expression of the various VEGF-A isoforms (121, -145, -165, and 189) and CAP2 markers (APLN, EDNRB, HPGD, SOSTDC1, and TBX2) in prenatal lung tissues aged from the late pseudoglandular to early canalicular stages (10–20 weeks of GA). There was simultaneous elevated expression of VEGF-A121, -145, and -189 in conjunction with several CAP2 markers (SOSTDC1, EDNRB, HPGD), peaking around 18–20 weeks of GA. Interestingly, this stage of development corresponds to the establishment of the canalicular stage, which is when the alveolo-capillary barrier initiates (Yaremenko et al., 2024; Pereda et al., 2013). It is also noteworthy that VEGF-A121 expression increases during this developmental stage in the human lung, whereas previous studies have shown that the expression of its murine homolog, Vegf-a120, decreases during development (Ng et al., 2001). This suggests that lung capillary development could involve different mechanisms in mice and in humans. Therefore, despite the mouse model providing some insightful information, our data highlight the relevance of investigating this process in human.

Human CAP1 cells are considered progenitor-like, exhibiting a greater proliferative capacity than CAP2 (Vila et al., 2020). To examine if the different VEGF-A isoforms could play a role in EC proliferation, we then treated human prenatal lung explants with exogenous VEGF-A isoforms, alone or combined, and analyzed EC number and proliferation by IF staining. None of the treatments led to a significant increase in EC number or proliferation rate. On the contrary, explants treated with VEGF-A189 showed a reduction of CD31+ cells when compared to the untreated control. They also presented fewer CD31-Ki67 double-positive cells, meaning VEGF-A189 inhibits the proliferation of ECs. However, in a similar way, it was reported that mice fibrosarcoma cells that were modified to only express Vegf-a188 (homologous to human VEGF-A189) had lower proliferation than those expressing only Vegf-a120 or Vegf-a164 (Kanthou et al., 2014). These results imply that different isoforms of the same gene can have divergent, even opposing, biological effects. Moreover, we observed that ECs in the explants treated with VEGF-A189 displayed a more flattened morphology, reminiscent of differentiated ECs (Pereda et al., 2013). Indeed, it was demonstrated that ECs presented an elongated shape, suggesting vascular remodeling and the generation of distal angiogenesis in mice (Pereda et al., 2013). Although none of the isoforms increased EC proliferation, it is therefore possible that their role in prenatal lung capillary development may instead involve promoting EC differentiation or maturation.

Analysis of CAP2 markers in the treated explants indeed revealed that VEGF-A signaling likely contributes to the development and regulation of CAP2 cells. We observed that all the VEGF-A isoforms decreased HPGD expression, except VEGF-A189. Since the lungs are a major site of prostaglandin metabolism, pulmonary capillary cells, such as CAP2 cells, are known to exhibit high expression of 15-PGDH. This high expression makes it a specific marker for these cells (Piper et al., 1970). Our data seems to show that HPGD expression isn’t promoted by VEGF-A isoforms. In contrast, VEGF-A189 was the only isoform to significantly decrease EDNRB expression, while the others had no effect. Interestingly, endothelin, a peptide hormone that plays a role in the regulation of blood pressure and vasoconstriction, have been shown to promote the proliferation of microvascular ECs through activation of endothelin receptors, such as EDNRB (Morbidelli et al., 1995). Therefore, the observed anti-proliferative effect of VEGF-A189 could partially be explained by this downregulation of EDNRB. Additionally, and most interestingly, it was noted that all VEGF-A isoforms (except VEGF-A145) increased APLN expression. Apelin is a small peptide hormone that functions as an endogenous ligand for the G-protein-coupled apelin receptor (APLNR) and which plays role in cardiovascular homeostasis (Wa et al., 2024). It has been well documented that APLN is a tip cell-enriched gene and promotes a pro-angiogenic state in ECs (del Toro et al., 2010; Helker et al., 2020). Apelin is important in vasculature formation during embryonic development of various models (Cox et al., 2006; Kälin et al., 2007). Apelin also enhances cardiac neovascularization acting as a chemoattractant by recruiting the cKit+/Flk1+/Aplnr + progenitor cells during the early myocardial repair (Temp et al., 2012). FISH analysis of APLN transcripts in the endothelium of VEGF-A-treated explants suggests that the increased expression likely originates from ECs. Among all the isoforms, VEGF-A121 seems to induce the highest APLN expression in the human prenatal lung explants. Interestingly, VEGF-A121 is the only freely diffusible VEGF-A isoform, not binding neuropilin-1 or heparan sulfate, and is known to mostly play a role in early angiogenesis rather than vessel maturation (Peach et al., 2018; Kawamura et al., 2008; Nakatsu et al., 2003).

VEGF-A has been shown to activate several intra- and intercellular signaling pathways associated with survival, migration, proliferation, and differentiation (Shiying et al., 2017). Therefore, it would be interesting to perform scRNA-seq and determine how pathway analysis and cell communication within the prenatal human lung are influenced by the different VEGF-A isoforms. Increasing our understanding of VEGF-A isoforms could lead to the establishment of new therapeutic strategies. For instance, for refractory angina, a new drug (XC001) corresponding to an adenoviral vector expressing 3 of the VEGF-A isoforms (VEGF-A121, -165, -189) is currently under testing, after it has been shown that it increased local neo-angiogenesis in preclinical studies (Povsic et al., 2023).

Although we believe our study is highly relevant given its exclusive use of prenatal human samples, with findings that challenge recent murine studies, we acknowledge certain limitations that may impede a complete understanding of VEGF-A’s role in CAP2 development. Whereas our lung explants were cultured under normoxic conditions, we appreciate that in utero lung development takes place in a hypoxic environment. Studies have demonstrated that hypoxia is a major driver of parenchymal and vascular lung development by downregulating VEGF-A expression (Zhou et al., 2022; Kim and Byzova, 2014; Esquibies et al., 2008). Furthermore, others have shown that pulmonary endothelial heterogeneity and CAP2 differentiation increase after birth, when the concentration of oxygen is increased (Zepp et al., 2021). Therefore, although the explants used are excised from prenatal tissues, normoxic conditions may not fully recapitulate the vascular development driven by hypoxia. Therefore, future studies under hypoxic conditions would be valuable to assess the expression of the different VEGF-A isoforms, as well as evaluate its influence on capillary development. Another important limitation to acknowledge is the inherent variability within human samples, which may influence how individual samples respond to different treatments/chemical concentrations. To address this, we first established optimal concentrations via dose-response treatments on several samples, prior to initiating the study. Additionally, we ensured that each sample provided enough explants to complete a full experiment, allowing comparisons to be made across treatments of the same sample. This helped minimize variability. Finally, we do note that although several of our results showed statistically significant differences in gene expression, the fold change was often quite small, again likely stemming from the variability associated with human samples.

Taken together, our findings show that human VEGF-A189 plays a different role than its murine homolog Vegf-a188, which highlights differences between the mouse model and humans. Our results show that several VEGF-A isoforms increase the expression of the CAP2 marker APLN in human prenatal lung explants, suggesting an implication in early angiogenesis. However, since they did not induce the entirety of the CAP2 signature, it suggests that CAP2 differentiation is likely a multifactorial process, not solely dependent on VEGF-A signaling.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human tissues were de-identified and designated as “non–human subjects research” by the The Lundquist Institute IRB (18CR-32223-01; determination 4 September 2020). Informed consent was obtained by the tissue banks at the time of donation.

Author contributions

AH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. AF: Data curation, Writing – review and editing. RB: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Software, Writing – review and editing. EL: Visualization, Writing – review and editing. OM: Data curation, Writing – review and editing. IG: Resources, Writing – review and editing. DA: Funding acquisition, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review and editing, Conceptualization. SD: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review and editing, Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. These authors acknowledge funding from CIRM (EDUC4-12837) Postdoctoral Training Grant (AH); NIH/NHLBI Office of The Director National Institutes of Health R01HL155104 (SD); NIH/NHLBI R01HL171915 (DAA), and NIH/NICHD R24HD000836 (IG).

Acknowledgments

We thank the Birth Defects Research Lab (BDRL) at the University of Washington which is supported by NIH Award Number R24HD000836 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcell.2025.1729884/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Arcondéguy T. Lacazette E. Millevoi S. Prats H. Touriol C. (2013). VEGF-A mRNA processing, stability and translation: a paradigm for intricate regulation of gene expression at the post-transcriptional level. Nucleic Acids Res.41 (17), 7997–8010. 10.1093/nar/gkt539

2

Bhattacharya S. Frauenpreis A. Cherry C. Deutsch G. Glass I. A. Mariani T. J. et al (2025). The transcriptional landscape of developing human trisomy 21 lungs. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol.rcmb.2025-0217OC. 10.1165/rcmb.2025-0217OC

3

Cantu A. Gutierrez M. C. Dong X. Leek C. Sajti E. Lingappan K. (2023). Remarkable sex-specific differences at single-cell resolution in neonatal hyperoxic lung injury. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol.324 (1), L5–L31. 10.1152/ajplung.00269.2022

4

Cox C. M. D’Agostino S. L. Miller M. K. Heimark R. L. Krieg P. A. (2006). Apelin, the ligand for the endothelial G-protein-coupled receptor, APJ, is a potent angiogenic factor required for normal vascular development of the frog embryo. Dev. Biol.296 (1), 177–189. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.04.452

5

Danopoulos S. Krainock M. Toubat O. Thornton M. Grubbs B. Al Alam D. (2016). Rac1 modulates mammalian lung branching morphogenesis in part through canonical Wnt signaling. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol.311 (6), L1036–L1049. 10.1152/ajplung.00274.2016

6

Danopoulos S. Bhattacharya S. Mariani T. J. Al Alam D. (2020). Transcriptional characterisation of human lung cells identifies novel mesenchymal lineage markers. Eur. Respir. J.55 (1), 1900746. 10.1183/13993003.00746-2019

7

Danopoulos S. Belgacemi R. Hein R. F. C. Miller A. J. Deutsch G. H. Glass I. et al (2023). FGF18 promotes human lung branching morphogenesis through regulating mesenchymal progenitor cells. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol.324 (4), L433–L444. 10.1152/ajplung.00316.2022

8

del Toro R. Prahst C. Mathivet T. Siegfried G. Kaminker J. S. Larrivee B. et al (2010). Identification and functional analysis of endothelial tip cell-enriched genes. Blood116 (19), 4025–4033. 10.1182/blood-2010-02-270819

9

Esquibies A. E. Bazzy-Asaad A. Ghassemi F. Nishio H. Karihaloo A. Cantley L. G. (2008). VEGF attenuates hyperoxic injury through decreased apoptosis in explanted rat embryonic lung. Pediatr. Res.63 (1), 20–25. 10.1203/PDR.0b013e31815b4857

10

Fidalgo M. F. Fonseca C. G. Caldas P. Raposo A. A. Balboni T. Henao-Mišíková L. et al (2022). Aerocyte specification and lung adaptation to breathing is dependent on alternative splicing changes. Life Sci. Alliance5 (12), e202201554. 10.26508/lsa.202201554

11

Fleming R. E. Crouch E. C. Ruzicka C. A. Sly W. S. (1993). Pulmonary carbonic anhydrase IV: developmental regulation and cell-specific expression in the capillary endothelium. Am. J. Physiol.265 (6 Pt 1), L627–635. 10.1152/ajplung.1993.265.6.L627

12

Galambos C. Ng Y. S. Ali A. Noguchi A. Lovejoy S. D'Amore P. A. et al (2002). Defective pulmonary development in the absence of heparin-binding vascular endothelial growth factor isoforms. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol.27 (2), 194–203. 10.1165/ajrcmb.27.2.4703

13

Gillich A. Zhang F. Farmer C. G. Travaglini K. J. Tan S. Y. Gu M. et al (2020). Capillary cell-type specialization in the alveolus. Nature586 (7831), 785–789. 10.1038/s41586-020-2822-7

14

He P. Lim K. Sun D. Pett J. P. Jeng Q. Polanski K. et al (2022). A human fetal lung cell atlas uncovers proximal-distal gradients of differentiation and key regulators of epithelial fates. Cell185 (25), 4841–4860.e25. 10.1016/j.cell.2022.11.005

15

Healy A. M. Morgenthau L. Zhu X. Farber H. W. Cardoso W. V. (2000). VEGF is deposited in the subepithelial matrix at the leading edge of branching airways and stimulates neovascularization in the murine embryonic lung. Dev. Dyn. Off. Publ. Am. Assoc. Anat.219 (3), 341–352. 10.1002/1097-0177(2000)9999:9999%3C::AID-DVDY1061%3E3.0.CO;2-M

16

Helker C. S. Eberlein J. Wilhelm K. Sugino T. Malchow J. Schuermann A. et al (2020). Apelin signaling drives vascular endothelial cells toward a pro-angiogenic state. eLife9, e55589. 10.7554/eLife.55589

17

Kälin R. E. Kretz M. P. Meyer A. M. Kispert A. Heppner F. L. Brändli A. W. (2007). Paracrine and autocrine mechanisms of apelin signaling govern embryonic and tumor angiogenesis. Dev. Biol.305 (2), 599–614. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.03.004

18

Kanthou C. Dachs G. U. Lefley D. V. Steele A. J. Coralli-Foxon C. Harris S. et al (2014). Tumour cells expressing single VEGF isoforms display distinct growth, survival and migration characteristics. PloS One9 (8), e104015. 10.1371/journal.pone.0104015

19

Kawamura H. Li X. Goishi K. van Meeteren L. A. Jakobsson L. Cébe-Suarez S. et al (2008). Neuropilin-1 in regulation of VEGF-induced activation of p38MAPK and endothelial cell organization. Blood112 (9), 3638–3649. 10.1182/blood-2007-12-125856

20

Kim Y. W. Byzova T. V. (2014). Oxidative stress in angiogenesis and vascular disease. Blood123 (5), 625–631. 10.1182/blood-2013-09-512749

21

Kumar V. H. Ryan R. M. (2004). Growth factors in the fetal and neonatal lung. Front. Biosci. J. Virtual Libr.9, 464–480. 10.2741/1245

22

Mamer S. B. Wittenkeller A. Imoukhuede P. I. (2020). VEGF-A splice variants bind VEGFRs with differential affinities. Sci. Rep.10 (1), 14413. 10.1038/s41598-020-71484-y

23

Morbidelli L. Orlando C. Maggi C. A. Ledda F. Ziche M. (1995). Proliferation and migration of endothelial cells is promoted by endothelins via activation of ETB receptors. Am. J. Physiol.269 (2 Pt 2), H686–H695. 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.269.2.H686

24

Nakatsu M. N. Sainson R. C. A. Pérez-del-Pulgar S. (2003). VEGF(121) and VEGF(165) regulate blood vessel diameter through vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 in an in vitro angiogenesis model. Lab. Investig. J. Tech. Methods Pathol.83 (12), 1873–1885. 10.1097/01.lab.0000107160.81875.33

25

Ng Y. S. Rohan R. Sunday M. E. Demello D. E. D’Amore P. A. (2001). Differential expression of VEGF isoforms in mouse during development and in the adult. Dev. Dyn. Off. Publ. Am. Assoc. Anat.220 (2), 112–121. 10.1002/1097-0177(2000)9999:9999%3C::AID-DVDY1093%3E3.0.CO;2-D

26

Peach C. J. Mignone V. W. Arruda M. A. Alcobia D. C. Hill S. J. Kilpatrick L. E. et al (2018). Molecular pharmacology of VEGF-A isoforms: binding and signalling at VEGFR2. Int. J. Mol. Sci.19 (4), 1264. 10.3390/ijms19041264

27

Pereda J. Sulz L. San Martin S. Godoy-Guzmán C. (2013). The human lung during the embryonic period: vasculogenesis and primitive erythroblasts circulation. J. Anat.222 (5), 487–494. 10.1111/joa.12042

28

Piper P. J. Vane J. R. Wyllie J. H. (1970). Inactivation of prostaglandins by the lungs. Nature225 (5233), 600–604. 10.1038/225600a0

29

Povsic T. J. Henry T. D. Traverse J. H. Anderson R. D. Answini G. A. Sun B. C. et al (2023). EXACT trial: results of the phase 1 dose-escalation study. Circ. Cardiovasc Interv.16 (8), e012997. 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.123.012997

30

Schupp J. C. Adams T. S. Cosme C. Raredon M. S. B. Yuan Y. Omote N. et al (2021). Integrated single-cell atlas of endothelial cells of the human lung. Circulation144 (4), 286–302. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.052318

31

Shibuya M. Claesson-Welsh L. (2006). Signal transduction by VEGF receptors in regulation of angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Exp. Cell Res.312 (5), 549–560. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.11.012

32

Shiying W. Boyun S. Jianye Y. Wanjun Z. Ping T. Jiang L. et al (2017). The different effects of VEGFA121 and VEGFA165 on regulating angiogenesis depend on phosphorylation sites of VEGFR2. Inflamm. Bowel Dis.23 (4), 603–616. 10.1097/MIB.0000000000001055

33

Tempel D. de Boer M. van D. E. D. Haasdijk R. A. Duncker D. J. Cheng C. et al (2012). Apelin enhances cardiac neovascularization after myocardial infarction by recruiting aplnr+ circulating cells. Circ. Res.111 (5), 585–598. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.262097

34

Trimm E. Red-Horse K. (2022). Vascular endothelial cell development and diversity. Nat. Rev. Cardiol.20, 1–14. 10.1038/s41569-022-00770-1

35

Tuder R. M. Yun J. H. (2008). Vascular endothelial growth factor of the lung: friend or foe. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol.8 (3), 255–260. 10.1016/j.coph.2008.03.003

36

Vila E. L. Cain M. P. Hutchison V. Flodby P. Crandall E. D. Borok Z. et al (2020). Epithelial vegfa specifies a distinct endothelial population in the mouse lung. Dev. Cell52 (5), 617–630.e6. 10.1016/j.devcel.2020.01.009

37

Wang W. W. Ji S. Y. Zhang W. Zhang J. Cai C. Hu R. et al (2024). Structure-based design of non-hypertrophic apelin receptor modulator. Cell187 (6), 1460–1475.e20. 10.1016/j.cell.2024.02.004

38

Wong J. Zhao G. Adams-Tzivelekidis S. Wen H. Chandrasekaran P. Michki S. N. et al (2024). Dynamic behavior and lineage plasticity of the pulmonary venous endothelium. Nat. Cardiovasc Res.3 (12), 1584–1600. 10.1038/s44161-024-00573-2

39

Yaremenko A. V. Pechnikova N. A. Porpodis K. Damdoumis S. Aggeli A. Theodora P. et al (2024). Association of fetal lung development disorders with adult diseases: a comprehensive review. J. Pers. Med.14 (4), 368. 10.3390/jpm14040368

40

Zepp J. A. Morley M. P. Loebel C. Kremp M. M. Chaudhry F. N. Basil M. C. et al (2021). Genomic, epigenomic, and biophysical cues controlling the emergence of the lung alveolus. Science371 (6534), eabc3172. 10.1126/science.abc3172

41

Zhou W. Liu K. Zeng L. He J. Gao X. Gu X. et al (2022). Targeting VEGF-A/VEGFR2 Y949 signaling-mediated vascular permeability alleviates hypoxic pulmonary hypertension. Circulation146 (24), 1855–1881. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.061900

Summary

Keywords

angiogenesis, APLN, capillaries, human lung development, VEGF-A

Citation

Hoarau A, Frauenpreis A, Belgacemi R, Loeffler E, Maalouf O, Glass IA, Al Alam D and Danopoulos S (2026) VEGF-A isoforms induce the expression of APLN in endothelial cells during human prenatal lung development. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 13:1729884. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2025.1729884

Received

22 October 2025

Revised

10 December 2025

Accepted

16 December 2025

Published

23 January 2026

Volume

13 - 2025

Edited by

Simona Ceccarelli, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy

Reviewed by

Wojciech Durlak, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute (OHRI), Canada

Yuyong He, Jiangxi Agricultural University, China

Shyam Thapa, Baylor College of Medicine, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Hoarau, Frauenpreis, Belgacemi, Loeffler, Maalouf, Glass, Al Alam and Danopoulos.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Soula Danopoulos, soula.danopoulos@lundquist.org

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.