Abstract

The homeostasis of a tissue such the gastrointestinal (GI) tract is of fundamental importance for human health, given its constant exposure to a wide variety of external substances. The Formyl peptide Receptor 1 (FPR1) is an innate immune receptor belonging to the FPR family, that can recognize various endogenous danger- and exogenous pathogen-associated molecules, triggering inflammation. Importantly, depending on the context and on the specific ligand, FPR1 can also stimulate inflammation resolution. Thus, FPR1 is a critical actor in GI physiopathology. Interestingly, not only FPR1 participates and is necessary for maintaining homeostasis, but it also exerts strong tumor suppressor properties in this tissue. The present review discusses the mechanisms responsible for this specific function of FPR1 in cancer of the GI tract, focusing in particular on FPR1-mediated signal transduction.

1 Introduction

The gastrointestinal (GI) epithelium has an active role in forming a selective physical and biochemical barrier between luminal content and the underlying tissue compartment. It creates and orchestrates a complex and balanced network regulating microbiota and mucosal immune system, thus ensuring tissue homeostasis maintenance. However, alteration of microbiota, infection, mechanical or pathological injury or intrinsic defects of the epithelial intestinal barrier can often cause the loss of homeostasis and allow the establishment of a chronic inflammatory state (Serhan et al., 2015; Prevete et al., 2017; Fishbein et al., 2021; Liotti et al., 2022a; Liotti et al., 2022b).

In physiological conditions, after an insult that causes epithelial wound, an acute inflammatory response occurs, characterized by pro-inflammatory mediators (e.g., eicosanoids and cytokines) production and innate immune cells’ recruitment (Gilroy, 2021; Roviello et al., 2022). After that, inflammatory response is dampened by inflammation resolution process, better known as restitution phase, induced by different actively produced pro-resolving mediators (Gilroy, 2021; Roviello et al., 2022).

Defects in restitution phase can lead to an exacerbated non-resolving inflammation, that could initiate or sustain the progression of numerous inflammation-driven diseases, including cancer (Prevete et al., 2018b).

Among mediators that contribute to the resolution response, there are lipidic molecules (Sugimoto et al., 2016), known as Specialized Pro-resolving Mediators [lipoxins (LX), resolvins (Rv), maresins (MaR) and protectins (PD)] (Serhan and Savill, 2005; Liotti et al., 2022a); proteic mediators such as Annexin A1 (AnxA1), adrenocorticotropic hormone, chemerin peptides, and galectin-1 (Perretti and D’Acquisto, 2009; Leoni et al., 2013; Sugimoto et al., 2016; Prevete et al., 2018b) and gaseous mediators (nitric oxide, hydrogen sulfide, and carbon monoxide) as well as neuromodulators such as acetylcholine (Mirakaj et al., 2014).

Due to this intimate relation between inflammation balance and GI cancer initiation and/or progression, a critical role in this tissue is ensured by innate immune receptors, whose primary role is to sense both exogenous and endogenous “danger” signals and sustain the barrier functions of the epithelia maintaining an equilibrium state (Pott and Hornef, 2012). Indeed, intestinal and gastric epithelial cells express significant levels of innate immune transmembrane or intracellular pattern recognition receptors (PRR), including Toll-like receptors (TLRs), nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptors (NLRs), and formyl peptide receptors (FPRs) (Hooper et al., 1998; Prevete et al., 2018a; Burgueño and Abreu, 2020; Guo et al., 2020; Eshleman and Alenghat, 2021). Accordingly, these PRRs not only play a pivotal role in detecting pathogenic threats and consequently triggering inflammation but are also involved in wound healing and epithelial repair, particularly in tissues constantly exposed to the external environment, such as the GI tract. These receptors contribute to modulate both inflammatory and pro-resolving responses, allowing the immune system to effectively discriminate between damaging agents and tolerated antigens (Pott and Hornef, 2012).

2 Formyl peptide receptors and their role in the physiopathology of the GI tract

Human formyl peptide receptors (FPRs), FPR1, FPR2 and FPR3 (Prossnitz and Ye, 1997), are PRRs belonging to the seven transmembrane domain Gi-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) family (Simon et al., 1991). They were originally characterized in phagocytes: upon stimulation by microbe- or mitochondria-derived formylated peptides, they sustain chemotaxis and reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation thus triggering inflammation and immune responses (Prossnitz and Ye, 1997; de Paulis et al., 2009). FPRs are promiscuous sensors that can pick up a wide range of exogenous and endogenous agonists, including non formylated peptides, lipids, and host derived danger signals (Migeotte et al., 2006; Ye et al., 2009).

Besides their expression in immune cells, FPRs are expressed also in several epithelia, including the GI mucosa (Le et al., 2002; Prevete et al., 2015a), where they are closely exposed to gut luminal contents (Babbin et al., 2007) to detect exogenous and host-derived ligands, including microbial formyl peptides from certain bacteria species (de Paulis et al., 2009; Wentworth et al., 2010). Beyond simple pathogen recognition, in intestinal epithelial cells FPRs serve also to distinguish pathogenic or commensal bacteria species and as receptors for endogenous pro-resolving mediators such as annexin A1 (AnxA1), lipoxin A4 (LXA4), and resolvin D1 (RvD1), thus triggering inflammation resolution and contributing to wound restitution and gut homeostasis (Babbin et al., 2007; Dufton and Perretti, 2010; Norling et al., 2012; Leoni et al., 2013; Prevete et al., 2015b).

Over decades FPR role in gastrointestinal epithelia has been deepened consolidating the evidence that the presence of this family of innate immune receptors plays a key role in the barrier function maintenance by regulating wound healing (Prevete et al., 2018a). For instance, it has been demonstrated that AnxA1 requires epithelial FPR1 and the enterocyte NADPH oxidase, NOX1, to promote intestinal mucosal wound healing after insult in a ROS-dependent modality (Leoni et al., 2013). FPR1-dependent signaling is necessary to epithelial repair responses by sensing also specific commensal species (i.e., Akkermansia muciniphila or Lactobacillus rhamnosus) (Babbin et al., 2007; Wentworth et al., 2010; Jeong and Bae, 2020; Liotti et al., 2022b). This process implicates the recruitment of protective microbial species to the site of injury (i.e., the anaerobic bacteria Akkermansia muciniphila), and the following activation of FPR1-dependent ROS-mediated wound healing pathways (Alam et al., 2016). Thus, FPRs regulate the enrichment of commensal species in the regions to be repaired and, once activated by these, trigger a wound healing response. Consistently, different studies demonstrate that FPR1−/− or FPR2−/− mice fail to properly heal colon mucosa after damage in chemically induced colitis model and show low colonic crypt length after recovery (Chen et al., 2013; Alam et al., 2014; Jeong and Bae, 2020).

Similarly, Helicobacter pylori-derived Hp(2–20) peptide, through the interaction with FPR2 and FPR3, regulates gastric mucosal healing after damage by facilitating epithelial cell migration, proliferation, and neoangiogenesis (de Paulis et al., 2009). Additionally, administration of this peptide has been reported to accelerate colitis recovery in a rat model (Gravina et al., 2018).

These experimental evidence on the key role of FPRs in managing gut homeostasis could explain the evidence in clinical practice of the increased expression of the receptors in inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), supporting the idea of a compensatory response following inflammation. Crohn’s disease patients show a high expression level of FPR1 in neutrophils (Anton et al., 1989); moreover, ulcerative colitis (UC) patients display an exacerbate activation of FPR1 in their intestines (Leoni et al., 2015). Similarly, UC patients display increased FPR2 expression levels compared to the healthy controls (Vong et al., 2012).

3 Functional role of FPR1 in cancer of GI tract

The FPR role in the homeostasis of gastrointestinal epithelia strongly suggests that FPRs may also be involved in the genesis and the progression of cancer. GI carcinomas are typically associated with both sterile and pathogen-induced inflammation. Indeed, an unsolved alteration of gut homeostasis, with prolonged inflammation, sustains inflammatory-based diseases and is strongly associated with the pathogenesis of cancer (Balkwill et al., 2012).

The evidence for the association between FPR1 and gastric cancer (GC) can be divided into two types of contrasting observations: i) FPR1 was detected in human GC specimens, and its levels are correlated with more aggressive clinical parameters and poorer outcome of patients (Cheng et al., 2014); ii) conversely, another study reports a positive association between a specific FPR1 polymorphism, which reduces receptor activity, and the increased risk of human GC (Otani et al., 2011). The first report suggests a positive correlation between FPR1 and GC progression, while the second a tumor suppressor role of the receptor in GC.

By studying the functional activity of FPR1 in GC experimental models, we described that the genetic ablation of FPR1 in human GC cells expressing high levels of the receptor increased their angiogenic and tumorigenic potential in vivo; accordingly, enforced expression of FPR1 in GC cells expressing low FPR1 levels caused the opposite effect, drastically impairing angiogenesis and tumor growth in vivo (Prevete et al., 2015b). By investigating the molecular mechanisms responsible for these FPR1 activities, we found that FPR1 blockade or silencing caused a drop in the production of endogenous levels of the Specialized Pro-resolving Mediators (SPMs), due to a reduction in their biosynthetic enzymes (i.e., ALOX5 and 15), and their relative receptors (i.e., GPR32, ChemR23, BLT1). A concomitant increase in the angiogenic potential (production of VEGFs, angiopoietin 1 and CXCL1) of FPR1-depleted GC cells could be observed. Consistently, we found that SPMs control the production of angiogenic mediators, since the exogenous administration of SPMs (RvD1 or LXB4) to FPR1-depleted GC cells could suppress their angiogenic potential. Moreover, the blockade of ALOX15, necessary for SPMs synthesis, or of the pro-resolving receptor GPR32, receptor for the SPM RvD1, enhanced angiogenesis and tumorigenic activity of GC cells, mimicking FPR1 depletion. Thus, we demonstrated that GC cells, similarly to many other cancer cells, are endowed with an intrinsic angiogenic potential, that could be negatively controlled by SPMs. These, in turn, are positively controlled by FPR1 (Prevete et al., 2015a; 2017). These data highlight the tumor suppressor function of FPR1 and suggest that the increased expression of the receptor in human GC samples could be related to a compensatory response.

Since SPMs are metabolite of ω3 and ω6 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA), we were able to demonstrate that diet enriched in PUFA could revert the increased angiogenic potential of FPR1-depleted tumors by enforcing SPMs production and counterbalancing the lack of resolution of cancer cells (Prevete et al., 2017). This opens new possibilities to be exploited for gastric cancer treatment and prevention.

Strong epidemiologic evidence showed that loss-of-function polymorphisms of FPR1 are positively associated with poor responses to chemotherapeutic drugs and an earlier mean age of cancer diagnosis (Sztupinszki et al., 2021) also in CRC patients. From a mechanistic point of view, FPR1 exerts a significant anti-cancer effect in CRC models through mechanisms similar to those observed in GC. Indeed, FPR1 activation by its natural ligands (the formylated peptide fMLF) or by commensal bacterial supernatants (Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG - LGG), but not by other lactic acid or non-probiotic bacteria (i.e., Bifidobacterium bifidum or Escherichia coli), sustains a pro-resolving response and dampens angiogenic potential in CRC cells (Liotti et al., 2022b).

Data produced by our laboratory are in line with the results of Chen and coll., who investigated the role of FPRs in colonic epithelial homeostasis, inflammation, and tumor formation in mice deficient for mFPR1 and/or mFPR2. They demonstrated that deletion of both receptors, with a prominent role of FPR2 on FPR1 in mice, increased colon tumorigenesis upon exposure to azoxymethane (AOM) and dextran sulphate (DSS), an inflammatory-driven model of CRC (Chen et al., 2013). Interestingly, this effect could be observed also upon conditional deletion of the receptors only in the epithelial compartment (Chen et al., 2013), thus indicating that the expression of the receptors in the intestinal epithelial cells exerts a critical impact on CRC progression. Accordingly, we demonstrated that FPR1 inhibition in human CRC cells in culture increased the intrinsic angiogenic potential of cancer cells. Moreover, conditioned media from FPR1-depleted CRC cells significantly increased endothelial cell migration and proliferation compared with parental cells (Liotti et al., 2022b). Furthermore, FPR1 deletion in CRC cells strongly impaired tumor-specific immune response, by reducing the ability of Dendritic cells (DCs) to migrate toward dying CRC cells (Le Naour et al., 2023), thus favoring colonic reactive hyperplasia and inflammation-induced colon tumorigenesis (Vacchelli et al., 2015; Vacchelli et al., 2016; Sztupinszki et al., 2021; Le Naour et al., 2023).

We hypothesize that the tumor suppressor role of FPR1 in GI tract is linked to the crucial homeostatic role of this innate immune receptor in such district, that is massively exposed to exogenous and host-derived stimuli and continuously involved in the balance between inflammation and its resolution. This could explain why FPR1, in other cancer contexts, exerts different functions: in the context of human glioblastoma, FPR1 confers a more invasive and angiogenic phenotype and modulates the tumor microenvironment to favor immunosuppression (Huang et al., 2010; Zheng et al., 2023).

4 Anti-tumor FPR1 signaling in intestinal epithelium

The above data consolidated the tumor suppressive role of FPR1 in gastrointestinal epithelia (Prevete et al., 2018a). However, the underlying signaling pathways involved in these activities were still undefined.

Classically, in immune cells FPRs mediate cell activation and inflammation responses mainly by evoking the activation of the RAS - MAPK cascade (Zhu et al., 2021), and by stimulating phospholipase Cβ to induce the release intracellular calcium from the endoplasmic reticulum, and subsequently PKC activation and ROS production (Kwan et al., 2008). The production of ROS is dependent on Rac2-mediated NADPH oxidase 2 (NOX2) activation and is functional to microbicidal activity (Bylund et al., 2003).

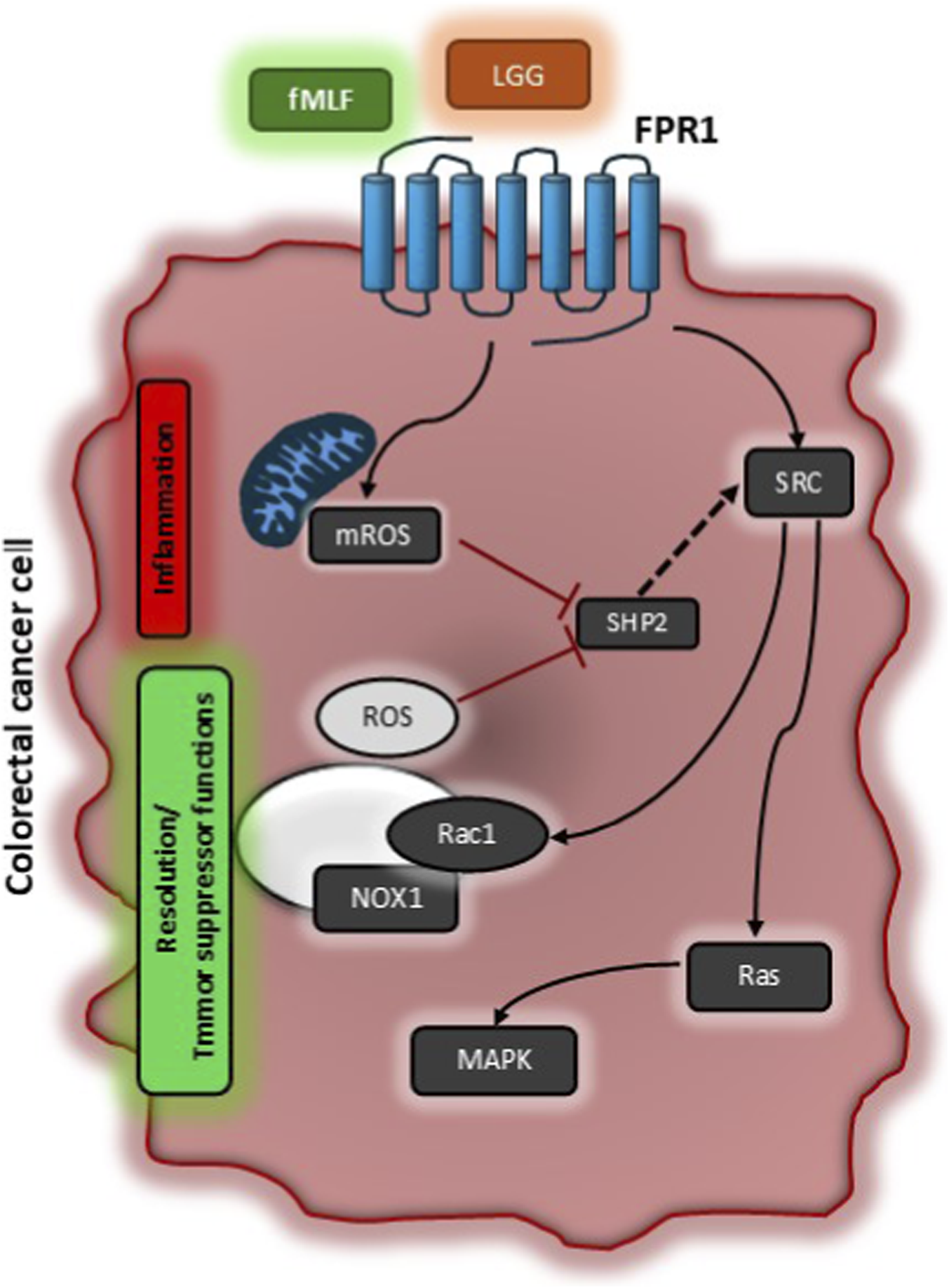

We asked which signal transduction pathways downstream FPR1 were involved in FPR1-induced pro-resolving and anti-angiogenic response in GI cancer cells (Liotti et al., 2022b; Liotti et al., 2025). For the first time, we described a mechanism of transduction involving ROS as signaling molecules (Figure 1). We found that the formylated peptide fMLF, by binding FPR1, induces two time- and source-distinguishable waves of ROS production in CRC cells: a first rapid mitochondrial-derived ROS production (mROS), followed by a second late wave, dependent from the first, due to the activation of NADPH oxidase 1 (NOX1). mROS triggers SHP2 phosphatase inactivation, which in turn allows SRC activation, to which follows the activation of the two small GTPases RAS and Rac1. RAS activates MAPK signaling, while Rac1 supports NOX1 activation, that generates the second wave of ROS, reinforcing this signaling cycle (Liotti et al., 2025). By using different approaches and functional assays we showed that mROS production precedes and is necessary for pro-inflammatory mediators’ release, while NOX1-generated ROS are only required for pro-resolving mediators’ synthesis. Finally, we could show that this signaling cascade is essential for the pro-resolving and anti-angiogenic properties of FPR1 in CRC (Liotti et al., 2025) (Figure 1). Importantly, our findings highlight a novel regulatory mechanism in CRC, where both the intensity and duration of ROS signaling critically determine the switch between pro-inflammatory and pro-resolving responses (Figure 1). We propose that the combined action of mROS and NOX1-derived ROS establishes a threshold level of MAPK activation required for the transcription of resolution genes and production of SPMs.

FIGURE 1

Schematic representation of signaling pathways activated by Formyl Peptide Receptor 1 to exert its tumor suppressor function. In colorectal carcinoma cells, activation of FPR1 by formylated peptides (e.g., fMLF) or bacterial supernatants (e.g., LGG – Lactobacillus Rhamnosus) induces a first rapid mitochondrial ROS production (mROS) which is responsible for SHP2 phosphatase inhibition. SHP2 inhibition allows SRC activation which controls the activity of Rac1 and RAS. Rac1 completes NOX1 multicomplex activation sustaining a second wave of NOX1-dependent ROS that reinforce this signaling cycle. RAS classically aids MAPK signaling. The first rapid ROS production by mitochondria is responsible for inflammatory responses (i.e., COX2 expression and PGD2 production), while NOX1-dependent ROS are associated to resolution responses (i.e., ALOXs induction and SPM release) and thus for tumor suppressor properties of FPR1.

It is consolidated in the literature that, for the switch from inflammation to resolution, it is essential to reach a “threshold” of inflammatory signals (Serhan, 2014; Sugimoto et al., 2016). Our results suggest that the amplitude and temporal dynamics of MAPK signaling could be the key to govern these two distinct transcriptional programs, ultimately dictating whether the cellular response favors inflammation or resolution.

The description of this signaling travels in parallel to evidence describing that the production of ROS is crucial also for the physiologic homeostatic functional role of FPR1 in intestinal epithelial cells (Hurd et al., 2012). It has been reported that FPR1, by binding the cleavage product of the pro-resolving ligand AnxA1 (i.e., Ac2-26 peptide), induces a NOX1-mediated ROS generation able to recover wounds. Specifically, Ac2-26 bond to FPR1 triggers SRC activation, followed by the association of p120 catenin with active Rac1, an essential regulator of NOX1 (Cheng et al., 2006). Then, NOX1-mediated ROS generation inactivates, by oxidation of the cysteine in their active site (Van Montfort et al., 2003), the regulatory phosphatases PTEN and PTP-PEST, with consequent activation of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) (Swanson et al., 2011) and paxillin to promote cell migration and thus mucosal wound restitution (Leoni et al., 2013). Complementary in vivo studies using intestinal epithelial cell specific Nox1−/− and AnxA1−/− mice demonstrated defects in intestinal mucosal wound repair (Leoni et al., 2013). Accordingly, systemic administration of AnxA1 prompts wound recovery in a NOX1-dependent fashion (Leoni et al., 2013). Besides AnxA1, in vivo studies demonstrated that in colonic enterocytes, FPR1 mediates commensal bacteria-stimulated NOX1-dependent ROS generation, which in turn activates phosphorylation of FAK and ERK, resulting in migration and proliferation that are required for intestinal homeostasis and wound restitution in colonic enterocytes (Alam et al., 2014). Moreover, fMLF - FPR1 interaction induces the activation of Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase (PI3K), that in turn activates Rac1 and Cdc42, which are crucial players in intestinal epithelial cell migration and restitution (Babbin et al., 2007). Again, commensal Lactobacillus rhamnosus bacterial products, by interacting with FPR1, induce generation of ROS that inactivates DUSP3 phosphatase, thus relieving ERK activation and promoting homeostatic signaling pathway in the mammalian intestine (Wentworth et al., 2011).

Independently from the cells, the stimulation of FPR1 triggers NOX activation thus increasing ROS production. It seems that the ROS produced in immune cells upon FPR stimulation, are fundamental in eliciting innate immune bactericidal functions, while, rather than detrimental, ROS produced through FPR1 stimulation in epithelial cells, serve as protective signaling molecules to convey cell responses to a homeostatic state.

5 Discussion

The knowledge of FPR1 signaling responsible for its anticancer properties opens the way for new therapeutic opportunities. Targeting FPR1 or its downstream signaling pathways is a possible option to treat patients with GI cancers. One of the most significant observations in this context is the identification of SHP2 phosphatase inhibition as an essential step for FPR1 anti-angiogenic properties in GI cancer cells. Interestingly, SHP2 phosphatase, with different mechanisms, functions as an oncogene in many other tumor types (Hakak et al., 2000; Agazie et al., 2003; Marotta et al., 2025) and several pharmacologic inhibitors are already available in clinical practice (Ahmed et al., 2019; Drilon et al., 2023; Marotta et al., 2025). Obviously, targeting FPR1 with agonists that induce its pro-resolving, anti-angiogenic and tumor suppressive activities is another possible strategy. The strong preclinical evidence in various disease models, including cancer, suggest that FPR1 agonism is a promising therapeutic approach. Small FPR1 agonists have been developed, but no compounds have still advanced to clinical trials in humans (Yi et al., 2024; Dahlgren and Forsman, 2025). For these reasons it would be desirable to continue the development of the compounds already identified, and to pursue the development of new compounds that are selective for FPR1 and able to activate the correct signaling pathways.

Statements

Author contributions

MM: Writing – review and editing, Writing – original draft. FL: Writing – review and editing, Writing – original draft. RM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. NP: Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. We acknowledge funding from: European Union - Next-Generation EU, National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), Mission 4, Component 1. PRIN - Progetti di Ricerca di Interesse Nazionale - Bando 2022 - Prot. 2022CSYK9L to NP(CUP E53D23009840006) and Bando PRIN 2022 PNRR Prot. P2022C5KBT to FL(CUP E53D23021540001).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Agazie Y. M. Movilla N. Ischenko I. Hayman M. J. (2003). The phosphotyrosine phosphatase SHP2 is a critical mediator of transformation induced by the oncogenic fibroblast growth factor receptor 3. Oncogene22, 6909–6918. 10.1038/sj.onc.1206798

2

Ahmed T. A. Adamopoulos C. Karoulia Z. Wu X. Sachidanandam R. Aaronson S. A. et al (2019). SHP2 drives adaptive resistance to ERK signaling inhibition in molecularly defined subsets of ERK-dependent tumors. Cell Rep.26, 65–78. 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.12.013

3

Alam A. Leoni G. Wentworth C. C. Kwal J. M. Wu H. Ardita C. S. et al (2014). Redox signaling regulates commensal-mediated mucosal homeostasis and restitution and requires formyl peptide receptor 1. Mucosal Immunol.7, 645–655. 10.1038/mi.2013.84

4

Alam A. Leoni G. Quiros M. Wu H. Desai C. Nishio H. et al (2016). The microenvironment of injured murine gut elicits a local pro-restitutive microbiota. Nat. Microbiol.1, 15021. 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2015.21

5

Anton P. A. Targan S. R. Shanahan F. (1989). Increased neutrophil receptors for and response to the proinflammatory bacterial peptide formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine in Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology97, 20–28. 10.1016/0016-5085(89)91410-8

6

Babbin B. A. Jesaitis A. J. Ivanov A. I. Kelly D. Laukoetter M. Nava P. et al (2007). Formyl peptide Receptor-1 activation enhances intestinal epithelial cell restitution through phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase-Dependent activation of Rac1 and Cdc42. J. Immunol.179, 8112–8121. 10.4049/jimmunol.179.12.8112

7

Balkwill F. R. Capasso M. Hagemann T. (2012). The tumor microenvironment at a glance. J. Cell Sci.125, 5591–5596. 10.1242/jcs.116392

8

Burgueño J. F. Abreu M. T. (2020). Epithelial Toll-like receptors and their role in gut homeostasis and disease. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.17, 263–278. 10.1038/s41575-019-0261-4

9

Bylund J. Samuelsson M. Collins L. V. Karlsson A. (2003). NADPH-oxidase activation in murine neutrophils via formyl peptide receptors. Exp. Cell Res.282, 70–77. 10.1016/S0014-4827(02)00010-1

10

Chen K. Liu M. Liu Y. Yoshimura T. Shen W. Le Y. et al (2013). Formylpeptide receptor-2 contributes to colonic epithelial homeostasis, inflammation, and tumorigenesis. J. Clin. Invest.123, 1694–1704. 10.1172/JCI65569

11

Cheng G. Diebold B. A. Hughes Y. Lambeth J. D. (2006). Nox1-dependent reactive oxygen generation is regulated by Rac1. J. Biol. Chem.281, 17718–17726. 10.1074/jbc.M512751200

12

Cheng T.-Y. Wu M.-S. Lin J.-T. Lin M.-T. Shun C.-T. Hua K.-T. et al (2014). Formyl peptide receptor 1 expression is associated with tumor progression and survival in gastric cancer. Anticancer Res.34, 2223–2229.

13

Dahlgren C. Forsman H. (2025). What is the potential of formyl peptide receptor 1 (FPR1) as a therapeutic target in human disease?Expert Opin. Ther. Targets29, 409–413. 10.1080/14728222.2025.2512525

14

de Paulis A. Prevete N. Rossi F. W. Rivellese F. Salerno F. Delfino G. et al (2009). Helicobacter pylori Hp(2–20) promotes migration and proliferation of gastric epithelial cells by interacting with formyl peptide receptors in vitro and accelerates gastric mucosal healing in vivo. J. Immunol.183, 3761–3769. 10.4049/jimmunol.0900863

15

Drilon A. Sharma M. R. Johnson M. L. Yap T. A. Gadgeel S. Nepert D. et al (2023). SHP2 inhibition sensitizes diverse oncogene-addicted solid tumors to Re-treatment with targeted therapy. Cancer Discov.13, 1789–1801. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-23-0361

16

Dufton N. Perretti M. (2010). Therapeutic anti-inflammatory potential of formyl-peptide receptor agonists. Pharmacol. Ther.127, 175–188. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2010.04.010

17

Eshleman E. M. Alenghat T. (2021). Epithelial sensing of microbiota-derived signals. Genes Immun.22, 237–246. 10.1038/s41435-021-00124-w

18

Fishbein A. Hammock B. D. Serhan C. N. Panigrahy D. (2021). Carcinogenesis: failure of resolution of inflammation?Pharmacol. Ther.218, 107670. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107670

19

Gilroy D. W. (2021). Resolving inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol.21, 620–621. 10.1038/s41577-021-00597-w

20

Gravina A. Prevete N. Tuccillo C. De Musis C. Romano L. Federico A. et al (2018). Peptide Hp(2–20) accelerates healing of TNBS‐induced colitis in the rat. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J.6, 1428–1436. 10.1177/2050640618793564

21

Guo H. Gibson S. A. Ting J. P. Y. (2020). Gut microbiota, NLR proteins, and intestinal homeostasis. J. Exp. Med.217, e20181832. 10.1084/jem.20181832

22

Hakak Y. Hsu Y. S. Martin G. S. (2000). Shp-2 mediates v-Src-induced morphological changes and activation of the anti-apoptotic protein kinase Akt. Oncogene19, 3164–3171. 10.1038/sj.onc.1203655

23

Hooper L. V. Bry L. Falk P. G. Gordon J. I. (1998). Host-microbial symbiosis in the mammalian intestine: exploring an internal ecosystem. BioEssays20, 336–343. 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199804)20:4<336::AID-BIES10>3.0.CO;2-3

24

Huang J. Chen K. Chen J. Gong W. Dunlop N. M. Howard O. M. Z. et al (2010). The G-protein-coupled formylpeptide receptor FPR confers a more invasive phenotype on human glioblastoma cells. Br. J. Cancer102, 1052–1060. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605591

25

Hurd T. R. DeGennaro M. Lehmann R. (2012). Redox regulation of cell migration and adhesion. Trends Cell Biol.22, 107–115. 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.11.002

26

Jeong Y. S. Bae Y.-S. (2020). Formyl peptide receptors in the mucosal immune system. Exp. Mol. Med.52, 1694–1704. 10.1038/s12276-020-00518-2

27

Kwan D. H. T. Kam A. Y. F. Wong Y. H. (2008). Activation of the human FPRL-1 receptor promotes Ca2+ mobilization in U87 astrocytoma cells. Neurochem. Res.33, 125–133. 10.1007/s11064-007-9425-7

28

Le Y. Murphy P. Wang J. (2002). Formyl-peptide receptors revisited. Trends Immunol.23, 541–548. 10.1016/S1471-4906(02)02316-5

29

Le Naour J. Montégut L. Pan Y. Scuderi S. A. Cordier P. Joseph A. et al (2023). Formyl peptide receptor-1 (FPR1) represses intestinal oncogenesis. OncoImmunology12, 2237354. 10.1080/2162402X.2023.2237354

30

Leoni G. Alam A. Neumann P.-A. Lambeth J. D. Cheng G. McCoy J. et al (2013). Annexin A1, formyl peptide receptor, and NOX1 orchestrate epithelial repair. J. Clin. Invest.123, 443–454. 10.1172/JCI65831

31

Leoni G. Gripentrog J. Lord C. Riesselman M. Sumagin R. Parkos C. A. et al (2015). Human neutrophil formyl peptide receptor phosphorylation and the mucosal inflammatory response. J. Leukoc. Biol.97, 87–101. 10.1189/jlb.4A0314-153R

32

Liotti F. Marotta M. Melillo R. M. Prevete N. (2022a). The impact of resolution of inflammation on tumor microenvironment: exploring new ways to control cancer progression. Cancers14, 3333. 10.3390/cancers14143333

33

Liotti F. Marotta M. Sorriento D. Pagliuca C. Caturano V. Mantova G. et al (2022b). Probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG) restrains the angiogenic potential of colorectal carcinoma cells by activating a proresolving program via formyl peptide receptor 1. Mol. Oncol.16, 2959–2980. 10.1002/1878-0261.13280

34

Liotti F. Marotta M. Costanzo M. De Simone C. Zirpoli S. De Falco V. et al (2025). Formyl peptide receptor 1 signaling strength orchestrates the switch from pro-inflammatory to pro-resolving responses: the way to exert its anti-angiogenic and tumor suppressor functions. Biomed. Pharmacother.186, 117961. 10.1016/j.biopha.2025.117961

35

Marotta M. Zirpoli S. Prevete N. De Simone C. Di Cristofano A. Liotti F. et al (2025). SHP2 is a multifunctional target in anaplastic thyroid carcinoma: cell intrinsic and immune-dependent anti-tumor effects. Biomed. Pharmacother.190, 118384. 10.1016/j.biopha.2025.118384

36

Migeotte I. Communi D. Parmentier M. (2006). Formyl peptide receptors: a promiscuous subfamily of G protein-coupled receptors controlling immune responses. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev.17, 501–519. 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2006.09.009

37

Mirakaj V. Dalli J. Granja T. Rosenberger P. Serhan C. N. (2014). Vagus nerve controls resolution and pro-resolving mediators of inflammation. J. Exp. Med.211, 1037–1048. 10.1084/jem.20132103

38

Norling L. V. Dalli J. Flower R. J. Serhan C. N. Perretti M. (2012). Resolvin D1 limits polymorphonuclear leukocyte recruitment to inflammatory loci: receptor-dependent actions. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol.32, 1970–1978. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.249508

39

Otani T. Ikeda S. Lwin H. Arai T. Muramatsu M. Sawabe M. (2011). Polymorphisms of the formylpeptide receptor gene (FPR1) and susceptibility to stomach cancer in 1531 consecutive autopsy cases. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.405, 356–361. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.12.136

40

Perretti M. D’Acquisto F. (2009). Annexin A1 and glucocorticoids as effectors of the resolution of inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol.9, 62–70. 10.1038/nri2470

41

Pott J. Hornef M. (2012). Innate immune signalling at the intestinal epithelium in homeostasis and disease. EMBO Rep.13, 684–698. 10.1038/embor.2012.96

42

Prevete N. Liotti F. Marone G. Melillo R. M. de Paulis A. (2015a). Formyl peptide receptors at the interface of inflammation, angiogenesis and tumor growth. Pharmacol. Res.102, 184–191. 10.1016/j.phrs.2015.09.017

43

Prevete N. Liotti F. Visciano C. Marone G. Melillo R. M. de Paulis A. (2015b). The formyl peptide receptor 1 exerts a tumor suppressor function in human gastric cancer by inhibiting angiogenesis. Oncogene34, 3826–3838. 10.1038/onc.2014.309

44

Prevete N. Liotti F. Illiano A. Amoresano A. Pucci P. De Paulis A. et al (2017). Formyl peptide receptor 1 suppresses gastric cancer angiogenesis and growth by exploiting inflammation resolution pathways. OncoImmunology6, e1293213. 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1293213

45

Prevete N. De Paulis A. Sgambato D. Melillo R. M. D`Argenio G. Romano L. et al (2018a). Role of formyl peptide receptors in gastrointestinal healing. Curr. Pharm. Des.24, 1966–1971. 10.2174/1381612824666180516102234

46

Prevete N. Liotti F. Amoresano A. Pucci P. De Paulis A. Melillo R. M. (2018b). New perspectives in cancer: modulation of lipid metabolism and inflammation resolution. Pharmacol. Res.128, 80–87. 10.1016/j.phrs.2017.09.024

47

Prossnitz E. R. Ye R. D. (1997). The N-formyl peptide receptor: a model for the study of chemoattractant receptor structure and function. Pharmacol. Ther.74, 73–102. 10.1016/S0163-7258(96)00203-3

48

Roviello G. Iannone L. F. Bersanelli M. Mini E. Catalano M. (2022). The gut microbiome and efficacy of cancer immunotherapy. Pharmacol. Ther.231, 107973. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2021.107973

49

Serhan C. (2014). Pro-resolving lipid mediators are leads for resolution physiology. Nature510, 92–101. 10.1038/nature13479

50

Serhan C. N. Savill J. (2005). Resolution of inflammation: the beginning programs the end. Nat. Immunol.6, 1191–1197. 10.1038/ni1276

51

Serhan C. N. Chiang N. Dalli J. (2015). The resolution code of acute inflammation: novel pro-resolving lipid mediators in resolution. Semin. Immunol.27, 200–215. 10.1016/j.smim.2015.03.004

52

Simon M. I. Strathmann M. P. Gautam N. (1991). Diversity of G proteins in signal transduction. Science252, 802–808. 10.1126/science.1902986

53

Sugimoto M. A. Sousa L. P. Pinho V. Perretti M. Teixeira M. M. (2016). Resolution of inflammation: what controls its onset?Front. Immunol.7, 160. 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00160

54

Swanson P. A. Kumar A. Samarin S. Vijay-Kumar M. Kundu K. Murthy N. et al (2011). Enteric commensal bacteria potentiate epithelial restitution via reactive oxygen species-mediated inactivation of focal adhesion kinase phosphatases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.108, 8803–8808. 10.1073/pnas.1010042108

55

Sztupinszki Z. Le Naour J. Vacchelli E. Laurent-Puig P. Delaloge S. Szallasi Z. et al (2021). A major genetic accelerator of cancer diagnosis: rs867228 in FPR1. OncoImmunology10, 1859064. 10.1080/2162402X.2020.1859064

56

Vacchelli E. Ma Y. Baracco E. E. Sistigu A. Enot D. P. Pietrocola F. et al (2015). Chemotherapy-induced antitumor immunity requires formyl peptide receptor 1. Science350, 972–978. 10.1126/science.aad0779

57

Vacchelli E. Enot D. P. Pietrocola F. Zitvogel L. Kroemer G. (2016). Impact of pattern recognition receptors on the prognosis of breast cancer patients undergoing adjuvant chemotherapy. Cancer Res.76, 3122–3126. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-0294

58

Van Montfort R. L. M. Congreve M. Tisi D. Carr R. Jhoti H. (2003). Oxidation state of the active-site cysteine in protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B. Nature423, 773–777. 10.1038/nature01681

59

Vong L. Ferraz J. G. P. Dufton N. Panaccione R. Beck P. L. Sherman P. M. et al (2012). Up-Regulation of Annexin-A1 and lipoxin A4 in individuals with ulcerative colitis may promote mucosal homeostasis. PLoS ONE7, e39244. 10.1371/journal.pone.0039244

60

Wentworth C. C. Jones R. M. Kwon Y. M. Nusrat A. Neish A. S. (2010). Commensal-Epithelial signaling mediated via formyl peptide receptors. Am. J. Pathol.177, 2782–2790. 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100529

61

Wentworth C. C. Alam A. Jones R. M. Nusrat A. Neish A. S. (2011). Enteric commensal bacteria induce extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway signaling via formyl peptide receptor-dependent redox modulation of dual specific phosphatase 3. J. Biol. Chem.286, 38448–38455. 10.1074/jbc.M111.268938

62

Ye R. D. Boulay F. Wang J. M. Dahlgren C. Gerard C. Parmentier M. et al (2009). International union of basic and clinical pharmacology. LXXIII. Nomenclature for the formyl peptide receptor (FPR) family. Pharmacol. Rev.61, 119–161. 10.1124/pr.109.001578

63

Yi X. Tran E. Odiba J. O. Qin C. X. Ritchie R. H. Baell J. B. (2024). The formyl peptide receptors FPR1 and FPR2 as targets for inflammatory disorders: recent advances in the development of small-molecule agonists. Eur. J. Med. Chem.265, 115989. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2023.115989

64

Zheng Y. Jiang H. Yang N. Shen S. Huang D. Jia L. et al (2023). Glioma-derived ANXA1 suppresses the immune response to TLR3 ligands by promoting an anti-inflammatory tumor microenvironment. Cell. Mol. Immunol.21, 47–59. 10.1038/s41423-023-01110-0

65

Zhu J. Li L. Ding J. Huang J. Shao A. Tang B. (2021). The role of formyl peptide receptors in neurological diseases via regulating inflammation. Front. Cell. Neurosci.15, 753832. 10.3389/fncel.2021.753832

Summary

Keywords

formyl peptide receptor 1, gastrointestinal epithelia, cancer, tumor suppressor, signaling

Citation

Marotta M, Liotti F, Melillo RM and Prevete N (2025) Tumor suppressor function of formyl peptide receptor 1 in gastrointestinal cancers: a focus on the underlying signaling. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 13:1733396. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2025.1733396

Received

27 October 2025

Revised

27 October 2025

Accepted

21 November 2025

Published

05 December 2025

Volume

13 - 2025

Edited by

Donatella Delle Cave, National Research Council (CNR), Italy

Reviewed by

Armel Hervé Nwabo Kamdje, University of Garoua, Cameroon

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Marotta, Liotti, Melillo and Prevete.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rosa Marina Melillo, rosmelil@unina.it; Nella Prevete, nella.prevete@unina.it

ORCID: Federica Liotti, orcid.org/0000-0002-0145-988X; Rosa Marina Melillo, orcid.org/0000-0002-9233-5275; Nella Prevete, orcid.org/0000-0002-0186-5431

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.