Abstract

The incidence of pancreatic exocrine disorders, particularly pancreatic cancer, has been steadily rising. However, treatment options remain limited, with substantial interindividual variability in therapeutic efficacy. This clinical challenge has accelerated the development of advanced three-dimensional (3D) modeling systems, with patient-derived organoids and multicellular spheroids emerging as transformative tools that faithfully recapitulate tumor pathophysiology. In contrast to 2D cultures, which fail to recapitulate the three-dimensional spatial architecture and cell-cell interactions found in vivo, these models have gained prominence in pancreatic cancer research due to their unique capacity to: (1) precisely mimic the tumor microenvironment (TME), (2) preserve tumor heterogeneity, and (3) enable rapid establishment. This review systematically examines current methodologies for constructing pancreatic exocrine 3D models, their integration with bioengineering platforms for drug screening, and innovative applications in multi-omics-driven precision medicine. We further evaluate the translational potential of these systems in clinical decision-making and discuss how they may reshape therapeutic paradigms for pancreatic diseases, offering new avenues for personalized treatment strategies.

1 Introduction

The pancreas is a vital organ with dual exocrine and endocrine functions, secreting digestive enzymes into the duodenum through acinar and ductal cells while regulating blood glucose. In benign exocrine disorders like chronic pancreatitis, progressive parenchymal injury and interstitial fibrosis leads to maldigestion, steatorrhea, and malnutrition, with no available therapies to delay or reverse pancreatic fibrosis (Giustarini et al., 2023; Hart and Conwell, 2020; Malik et al., 2023). For pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), the most aggressive pancreatic malignancy with a 5-year survival rate of only 11%, most patients present with metastatic unresectable disease, gemcitabine-based chemotherapy shows merely 20% efficacy due to resistance mechanisms, and emerging immunotherapies face challenges from interpatient heterogeneity (Eso et al., 2020; Gu et al., 2021; Siegel et al., 2022). These clinical unmet needs underscore the critical importance of developing pathologically relevant models to advance both pancreatic disease therapeutics and precision oncology approaches.

Organoids are miniature 3D organ models that self-organize from adult stem cells (ASCs), embryonic stem cells (ESCs), or induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) faithfully replicating both the structure and function of native tissues (Corrò et al., 2020). Particularly valuable are patient-derived organoids (PDOs), which maintain tumor heterogeneity and accurately mirror the histological, genomic, and proteomic profiles of original tumors - making them ideal for personalized medicine (Boj et al., 2015). When co-cultured with cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) or immune cells, PDOs can better recapitulate the TME, significantly improving clinical predictability (Schuth et al., 2022; Tsai et al., 2018). In contrast, spheroids are simpler 3D cell aggregates (from primary cells or cell lines) that mimic basic cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions (Ryu et al., 2019). Current pancreatic spheroid systems incorporate multiple cell types such as pancretic progenitor cells, ductal cells, acinar cells, pancreatic stellate cells (PSCs), tumor cells, and immune cells (Giustarini et al., 2023; Grapin-Botton, 2016). While spheroids offer advantages like easier culture, faster generation, and lower cost, they have limited capability to mimic the in vivo environment compared to organoids (van Renterghem et al., 2023). The integration of 3D cell culture with microfluidics, AI, automation, and computational tools has enabled high-throughput production, intelligent monitoring, and standardized evaluation - advancing its application in drug screening (Ma et al., 2021; Wang and Jeon, 2022). Furthermore, combining patient-derived pancreatic organoids with multi-omics analysis has deepened our understanding of PDAC tumor heterogeneity and molecular profiles, facilitating the development of personalized therapies targeting specific molecular features to improve clinical outcomes (Boilève et al., 2024). This review summarizes recent progress in pancreatic organoid and spheroid technologies for drug screening and precision medicine, highlighting how engineered platforms and multi-omics approaches are driving these advancements.

2 Establishment of pancreatic organoids and spheroids

An important breakthrough in pancreatic organoid research originated from the discovery by Meritxell Huch’s team (Huch et al., 2013): in vitro Lgr5+ pancreatic ductal cells exhibit stem cell characteristics, capable of differentiating into both endocrine and exocrine pancreatic cells, while maintaining genetic stability and proliferative capacity over long-term culture exceeding 10 months. Based on this stable in vitro culture system, organoids can not only accurately replicate the developmental dynamics, three-dimensional structure, and physiological functions of pancreatic organs but also construct disease models using gene editing technologies (Kim et al., 2020). Currently, modeling of pancreatic exocrine organoids mainly comes from ASCs, iPSCs, or ESCs, in which organoids derived from ASCs maintain stable and continuous passage while reflecting the characteristics of their source tissues, making them suitable for ongoing drug screening and personalized disease research; organoids derived from iPSCs or ESCs can simulate pancreatic development during embryonic development, facilitating the study of disease mechanisms or early interventions in disease progression (Grapin-Botton, 2016). In this section, we will discuss the construction methods of pancreatic exocrine organoids and the challenges currently faced.

2.1 ASCs-derived pancreatic organoids

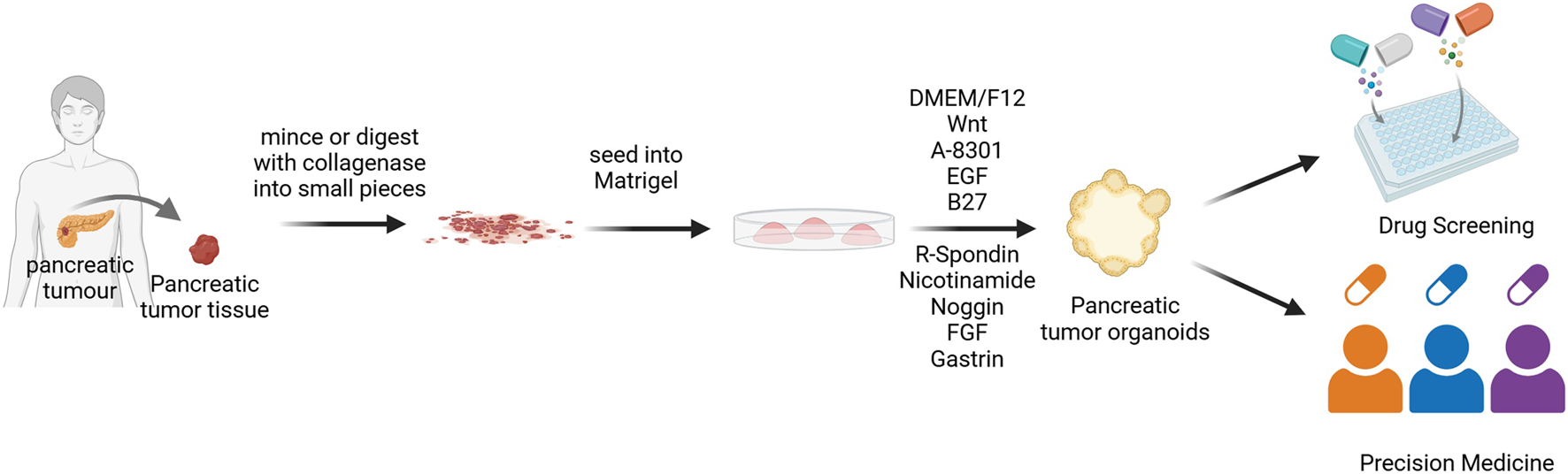

ASCs that can differentiate into both endocrine and exocrine pancreatic cells exist within the pancreatic ducts, and during pancreatic injury, they can re-express the endodermal lineage marker PDX1 through a dedifferentiation process, thereby recreating the developmental differentiation pathway (Li et al., 2010; Xu et al., 2008). Building on this ductal cell potential, pancreatic tissues undergo collagenase digestion and filtration to isolate ductal fragments. These fragments are then seeded into Matrigel, where they self-organize into pancreatic organoids containing functionally distinct endocrine and exocrine cell populations (Huch et al., 2013; Seino et al., 2018) (Figure 1). Adult stem cell-derived pancreatic organoids primarily focus on pancreatic tumor organoids, with two common construction methods: one is to directly digest pancreatic tumor tissue obtained from surgical resection or fine needle aspiration biopsy, achieving a success rate of 85% (Huang et al., 2015); the other is genetic modification of normal pancreatic organoids via CRISPR-Cas9-mediated oncogene editing or transcriptional reprogramming, with a success rate of about 70% (Kawasaki et al., 2020). As the most clinically relevant in vitro models, patient-derived organoids (PDOs) from ASCs faithfully recapitulate tumor heterogeneity and histopathological features, making them invaluable for personalized medicine (Dayton et al., 2023; Tong et al., 2024). Notably, pancreatic cancer PDOs demonstrate 91.1% predictive accuracy for patient responses to first-line chemotherapies (Beutel et al., 2021). Although ASC-derived pancreatic organoid technology has been widely applied in pancreatic cancer research, the development of organoid models for benign inflammatory diseases, such as chronic pancreatitis, remains in its early stages (Chen et al., 2024) This is primarily due to several technical bottlenecks. First, obtaining clinical tissue samples from benign lesions is challenging. Second, cultured cells from chronic pancreatitis, such as acinar cells, are prone to spontaneous dedifferentiation in vitro, making it difficult to maintain their functional phenotypes long-term Finally, a core feature of the disease—the sustained inflammatory and fibrotic microenvironment—involves complex interactions among immune cells, stellate cells, and the extracellular matrix. Recapitulating this dynamic process in vitro represents the most significant current challenge. Notably, this spontaneous dedifferentiation observed in culture models the key pathological process of “acinar-to-ductal metaplasia,” which links pancreatitis to preneoplastic lesions, providing a unique entry point for disease modeling (Zuiani et al., 2024).

FIGURE 1

Flowchart of PDOs construction. Tumor tissues obtained from patients are digested using enzymatic digestion methods, then seeded into Matrigel to differentiate into pancreatic exocrine organoids (Rauth et al., 2021). DMEM/F12, Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium/Nutrient Mixture F-12; EGF, Epidermal growth factor; FGF, Fibroblast growth factor.

The culture medium and matrix gel are critical determinants of organoid culture. The matrix gel, typically derived from Engelbreth-Holm-Swarm (EHS) mouse tumor extracts, provides a basement membrane scaffold enriched with extracellular matrix proteins (Kleinman and Martin, 2005). For pancreatic organoid culture, a growth factor-reduced formulation is preferred, as the native matrix gel contains over 1,800 proteins that could confound cellular behavior, signaling pathways, and cytokine analyses (Boj et al., 2015; Hughes et al., 2010; Raghavan et al., 2021). On the other hand, the culture medium must precisely modulate key signaling pathways to enable organoid self-assembly: Wnt/β-catenin activators (RSPO1, Wnt3a, Noggin) stimulate ASCs via Lgr5 (Huch et al., 2013; Yan et al., 2017); EGF and FGF10 sustain pancreatic progenitor proliferation (Ndlovu et al., 2018); while EGF with nicotinamide enhances ductal cell clonogenicity (Wedeken et al., 2017); Supplements like B27 further support organoid morphogenesis. However, mitogenic factors present a double-edged sword: EGF/FGF not only drive proliferation but also induce scBasal-to-scClassical transition in PDAC organoids, altering transcriptional profiles (Raghavan et al., 2021), and may promote acinar-ductal metaplasia (Perera and Bardeesy, 2012). This necessitates careful optimization of culture conditions to balance organoid expansion with preservation of native tissue characteristics.

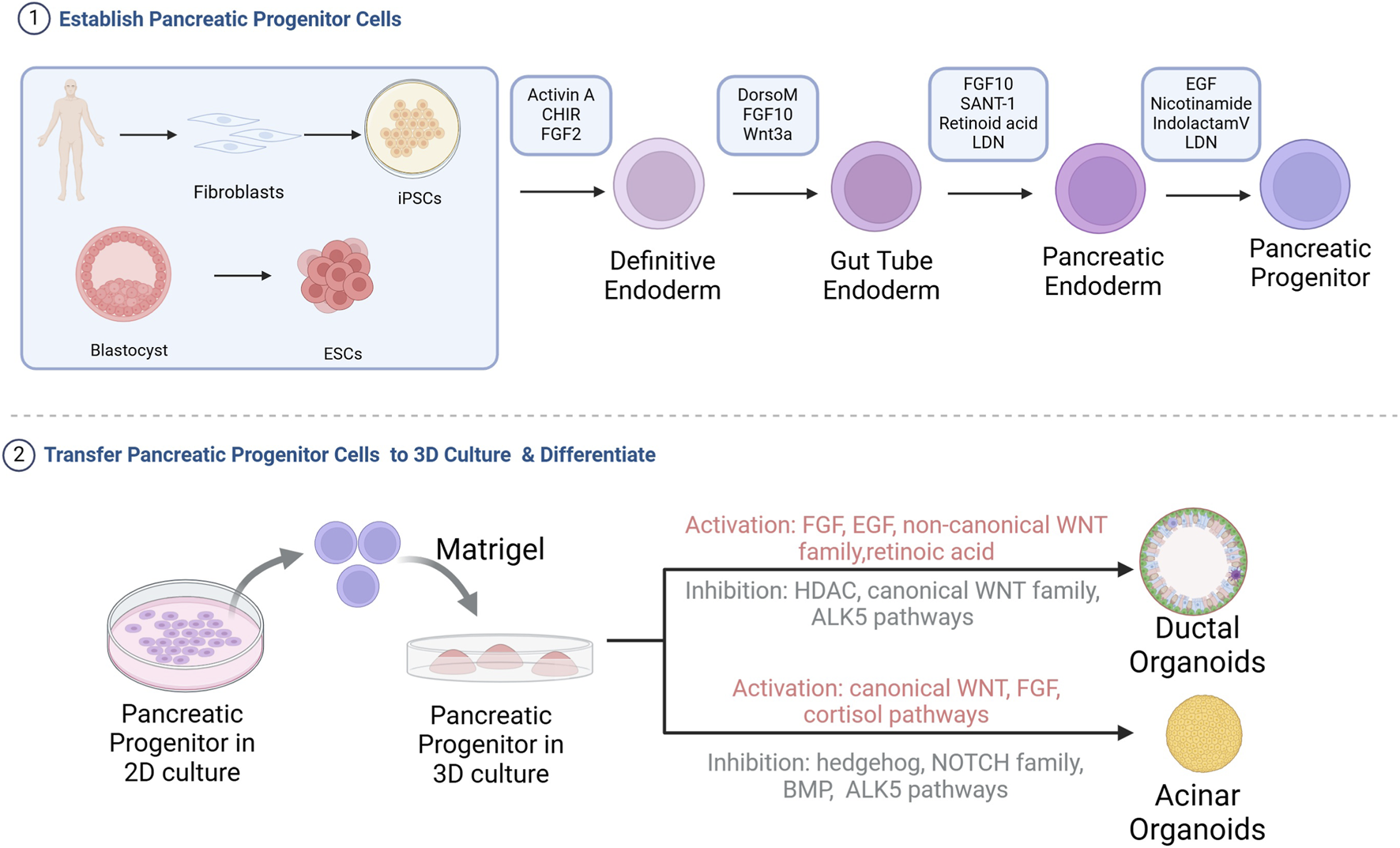

2.2 iPSCs-derived or ESCs-derived pancreatic organoids

Unlike ASCs in pancreatic tissue, which can only differentiate into pancreatic cells, ESCs or iPSCs have a higher differentiation potential and can be induced into almost all cell types in the body (Tian et al., 2023). The developmental pathway for pancreatic organoids from these pluripotent stem cells recapitulates embryonic pancreas development. This process begins with differentiation of ESCs/iPSCs into definitive endoderm, progresses through primitive gut tube formation, and finally develops into multipotent pancreatic progenitor cells (MPCs) expressing key markers Ptf1a and Pdx1 (Jennings et al., 2015; Pan and Wright, 2011). To mimic this developmental sequence in vitro, specific signaling pathways are sequentially modulated using defined growth factors and small molecules, as summarized in Table 1. Next, these pancreatic progenitor cells are then embedded in Matrigel for 3D organoid culture (Figure 2). Further purification using cell sorting techniques to isolate glycoprotein-2 positive (GP2+) progenitor populations enhances their ability to differentiate into all three pancreatic lineages - acinar, ductal, and endocrine cells - enabling generation of corresponding organoid types (Merz et al., 2023).

TABLE 1

| Stage | Differentiation stage/target | Targeted pathway/mechanism | Compounds |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pancreatic development stages (Jennings et al., 2015; Pan and Wright, 2011) | Definitive endoderm formation | Activates TGF-β signaling | GDF8, Activin A (Wei and Wang, 2018) |

| Primitive gut tube formation | Provides FGF signaling | FGF7, FGF10 | |

| Pancreatic progenitor specification | Retinoic acid signaling; inhibits Hedgehog; inhibits BMP | Retinoic Acid, SANT1, LDN193189 (Pagliuca et al., 2014; Rezania et al., 2014) | |

| Lineage specification stages | Acinar organoids | Sustained activation of Wnt/β-catenin | CHIR, SKL2001, WNT1 (Keefe et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2022; Wells et al., 2007; Yu et al., 2019) |

| Induces acinar gene expression | Dexamethasone (Logsdon et al., 1985) | ||

| Inhibits Hedgehog pathway; Inhibits Hippo pathway:prevents ductal fate | HPI-1,XMU-MP-1 (Fan et al., 2016; Hyman et al., 2009; Pasca di Magliano et al., 2006; Wu et al., 2021) | ||

| Biphasic modulation of Notch pathway: Early proliferation vs. late maturation | Early: FGF10; Late: Dibenzazepine (Hald et al., 2003; Hart et al., 2003) | ||

| Ductal organoids | Inhibits canonical Wnt signaling | IWP2, iCRT14, IQ1 (Bilir et al., 2013; Haumaitre et al., 2008) | |

| Activates non-canonical Wnt signaling | Foxy5 (Leszczynska et al., 2024; Sasaki and Kahn, 2014) | ||

| Inhibits histone deacetylase | SB939, WT161 (Shen et al., 2022; Sun et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2023) | ||

| Commonly used (early stage) | Progenitor maintenance/Apoptosis inhibition | FGF10, Y27632, EGF (Ndlovu et al., 2018; Norgaard et al., 2003) |

Summary of key compounds for inducing iPSC/ESC-derived pancreatic organoids.

FIGURE 2

Flowchart of the construction of pancreatic acinar or ductal organoids from iPSCs or ESCs. iPSCs or ESCs are differentiated into pancreatic progenitor cells in 2D culture, followed by seeding into Matrigel for directed differentiation into pancreatic acinar or ductal organoids. HDAC, Histone deacetylases; BMP, Bone morphogenetic protein (Breunig et al., 2021; Huang et al., 2021; Pagliuca et al., 2014; Wiedenmann et al., 2021).

The ability to derive both acinar and ductal organoids from pluripotent stem cells provides powerful tools for modeling pancreatic disease development. Ling Huang’s group established a four-stage differentiation protocol to generate these organoid types from pancreatic progenitor cells (Huang et al., 2021). From iPSC to pancreatic organoids, the required compounds and their roles are listed in Table 1. During pancreatic organoid differentiation, progenitor markers (NKX6.1, Pdx1) gradually decrease while lineage-specific markers emerge. Mature organoids exhibit characteristic polarization, with tight junction protein ZO-1 localized apically and basement membrane components (collagen IV, laminin-α5) basally (Hohwieler et al., 2017; Huang et al., 2021). Acinar and ductal organoids differ markedly in morphology, marker expression and functional characteristics (summarized in Table 2). A key limitation is that current differentiation protocols typically produce organoids resembling fetal rather than adult pancreatic tissue (Huang et al., 2015). This developmental immaturity likely reflects the absence of crucial niche interactions present during normal pancreatic development that are difficult to replicate in vitro. Overcoming this limitation represents an important challenge for the field.

TABLE 2

| Organoid type | Structure | Function | Markers | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acinar organoids | Small diameter, 20–105 μm, no lumen | High amylase and lipase activity | PTF1A, HNF1B chymotrypsin C, RBPJL, CPA1, amylase | Hohwieler et al. (2017), Huang et al. (2021) |

| Ductal organoids | Large diameter, 50–220 μm, visible lumen expansion | Functional CFTR; high carbonic anhydrase activity | SOX9, carbonic anhydrase II, CK19 | Hohwieler et al. (2017), Huang et al. (2021) |

Comparison of acinar and ductal organoids.

Compared to ASC-derived organoids, those generated from ESCs or iPSCs offer unique advantages in modeling developmental processes and disease progression. These systems enable researchers to trace the evolutionary trajectory of pathogenic mutations through gene editing technologies, providing valuable platforms for personalized medicine (Breunig et al., 2021; Hirshorn et al., 2021). Huang et al. (2015) demonstrated this potential by establishing KRAS- and TP53-mutated pancreatic cancer organoids from human pluripotent stem cells. Their 3D culture system not only revealed molecular mechanisms of pancreatic carcinogenesis but also identified genotype-phenotype correlations and enabled drug screening for personalized treatment strategies. For benign diseases, iPSC-derived pancreatic ductal organoids harboring the CFTR ΔF508 mutation exhibited no swelling response upon forskolin treatment, indicating a chloride ion transport defect. These organoids can be used to screen CFTR modulators, offering a potential strategy to guide personalized therapy for patients with cystic fibrosis (Mun et al., 2022).

2.3 Pancreatic spheroids

Compared to conventional monolayer cultures, 3D spheroids demonstrate significantly increased resistance to chemotherapy. The concentric layered structure of spheroids creates a physical barrier where outer cells protect inner cells from drug penetration, mimicking the drug diffusion limitations seen in solid tumors in vivo (Perche and Torchilin, 2012). Notably, PDAC spheroids show a 200-fold increase in IC50 values for gemcitabine and oxaliplatin compared to their 2D counterparts (Firuzi et al., 2019). Furthermore, the 3D architecture more accurately reproduces the complex cell-cell and cell- extracellular matrix (ECM) interactions found in native tumor tissue (Ishiguro et al., 2017). Moreover, spheroid culture enables precise control over spheroid size, enhances data reproducibility, and facilitates high-throughput screening when integrated with advanced technologies like 3D printing. These advantages make spheroid models an ideal preclinical platform for drug screening (Friedrich et al., 2009; Huang et al., 2023). Pancreatic spheroids are primarily generated from established 2D cell lines using scaffold-based or scaffold-free methods. Scaffold-based cultures utilize agarose, collagen, or gelatin to mimic the ECM, facilitating cell aggregation, proliferation, and migration. In contrast, scaffold-free approaches employ ultra-low adhesion surfaces, hanging drop techniques, or microfluidics to promote spontaneous spheroid formation (Gündel et al., 2021). Beyond cell lines, patient-derived tumor cells can also form spheroids. For instance, microfluidic-assisted 3D models encapsulate primary pancreatic cancer cells, generating stable tumor spheroids that retain patient-specific heterogeneity and enable drug efficacy assessment (Song et al., 2023). Compared to organoids, spheroids offer simpler handling, faster culture, and lower cost. However, their ability to recapitulate the in vivo microenvironment remains inferior to both organoids and animal models (Białkowska et al., 2020).

2.4 Pancreatic 3D co-culture model

Monotypic tumor organoids and spheroids lack essential stromal constituents-including CAFs and immune infiltrating cells, and therefore fail to faithfully reproduce the complexity of the native tumor microenvironment. Specifically, without CAFs, the models cannot reproduce their promotion of tumor-cell proliferation, motility, and therapy resistance, nor their capacity to dampen immune surveillance. Similarly, the omission of immune cells can markedly distort organoid-based predictions of responses to immunotherapies, chemotherapeutics, and radiotherapy (Guinn et al., 2024; Peng and Oberstein, 2025). To better recapitulate the intricate cellular interplay of the pancreatic TME, investigators have established multiple coculture platforms integrating pancreatic organoids/spheroids with stromal cell counterparts (Hwang et al., 2019; Tsai et al., 2018). Table 3 provides a comparative summary of spheroid coculture approaches across studies, including system architecture, cell-type composition, and coculture ratios.

TABLE 3

| Spheroid type | Modeling Features | Cell types and ratio | Advantages | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spheroid-on-chip | • Collagen type I (Col I) hydrogel • Microfluidic platform |

750 cells/device Pancreatic cancer cell lines (BxPC-3, Capan-2, Panc-1, MIA PaCa-2):human pancreatic stellate cells = 2:1 |

Enables study of the effects of fluid shear stress, matrix stiffness, and other biophysical cues on tumor growth | Hernández-Hatibi et al. (2025) |

| Spheroid | • Ultra-low attachment plates • Use of Orbits™ software to quantify cell ratios; the mixing ratio of the three target cell types was iteratively optimized by comparing the cellular composition of cultured spheroids with that of PDAC tumors |

3000–7500 cells/spheroid (1) BxPC-3: RLT-PSC: HMEC-1 = 7 : 2: 4 (2) BxPC-3: hPSC21: HMEC-1 = 6 : 5: 3 (3) MiaPaCa-2: RLT-PSC: HMEC-1 = 6 : 3: 3 (4) MiaPaCa-2: hPSC21: HMEC-1 = 5 : 6: 4 |

1. Effectively recapitulates key features of the PDAC tumor microenvironment 2. Demonstrates that tumor cell drug resistance is influenced by cellular composition, density, and spatial organization |

Verloy et al. (2025) |

| Multi-layer spheroid | • Ultra-low attachment plates • Fibrotic-core multilayer spheroid without exogenous matrix. The core is a compacted mixture of tumor cells and CAFs, followed by an outer layer of additional CAFs, constrained by an outermost alginate hydrogel shell |

Tumor cells: CAFs = 1 : 1 (250 cells: 250 cells) for the core mixture; the outer layer is formed by adding 4000 CAFs | 1. Structurally stable for up to 14 days 2. Exhibits higher drug resistance, faster tumor growth rate, and increased expression of immunosuppressive cytokines |

Jang et al. (2024) |

| Spheroid | Ultra-low attachment plates | 35,000 or 40,000 cells/well Pancreatic cancer cells (MiaPaCa2): Immune cells (U937 or CD11b+ cells) = 1 : 3 to 1 : 6 |

Facilitates the design of novel neutrophil-based immunotherapy strategies | Shao et al. (2024) |

Construction of co-culture spheroid systems in pancreatic cancer modeling.

Analogously, organoid coculture models incorporating essential TME stromal constituents markedly improve biological fidelity and predictive performance. These systems fall into two major categories: (1) coculture with CAFs to model CAF-driven inflammatory activation and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) reprogramming, leading to diminished chemotherapeutic sensitivity (Gout et al., 2025); while (2) coculture with immune cells reconstitutes the immune microenvironment, enabling robust preclinical assessment of immune-checkpoint blockade, CAR-T therapy, and other immunotherapeutic modalities (Meng et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2023). Expanding these systems to multicellular cocultures incorporating immune cells, CAFs, and tumor cells enables detailed dissection of TME interaction networks and aids in the discovery of targeted interventions (Tsai et al., 2018). Current co-culture methods primarily include (1) direct contact approaches, where dissociated organoids and co-cultured cells are embedded together in Matrigel to allow cell-cell interactions, and (2) indirect contact systems, which use transwell chambers to physically separate 3D-cultured cells in the lower chamber from co-cultured cells in the upper chamber (Öhlund et al., 2017).In conclusion, by incorporating essential TME elements, these next-generation models markedly enhance preclinical predictive power and furnish critical technological foundations for innovative therapy development.

2.5 Pancreatic 3D culture on chip

Although fibroblasts or immune cells have been incorporated into coculture systems, the lack of vascularization and static perfusion within the TME persists, limiting their capacity to fully recapitulate the complexity of the human tumor microenvironment. These limitations include reduced viability due to insufficient oxygenation, phenotypic drift, and inaccurate drug-response predictions. In recent years, integrating pancreatic organoids/spheroids with microfluidic chip technology has provided a promising solution to these challenges. These microfluidic platforms incorporate perfusable microvascular networks that support the growth, maturation, and function of 3D models, enabling highly biomimetic and dynamic TME simulations (Quintard et al., 2024). The advantages of microfluidic platforms are summarized below: First, the perfusable vascular system provides tumor and immune cells with appropriate ECM architecture and mechanical microenvironments, allowing more accurate support of immune-cell infiltration, activation, and intercellular communication, thereby offering significant advantages for evaluating immunotherapies (Choi et al., 2024). Second, this system enables dynamic, drug transport kinetics and therapeutic efficacy (Kim et al., 2025). When integrated with automated control, the system enables precise regulation of nutrient and drug delivery and supports high-throughput, parallel testing of multiple drug sensitivities, significantly improving screening efficiency and accuracy (Castiaux et al., 2019; Schuster et al., 2020). Furthermore, organ-on-chip technology offers the potential for multi-organ integration. By linking pancreas-specific chips with other organ systems, a “human-on-a-chip” platform can be constructed to investigate inter-organ communication, systemic metabolic pathways, and whole-body toxicity (Wang et al., 2019). In summary, microfluidic technology provides a powerful platform for studying the tumor microenvironment, drug responses, and immune interventions in vitro by constructing perfusable vascular networks, enabling precise environmental control, and incorporating automated operations.

Following the detailed description of the four major 3D models, a comprehensive comparison of their key characteristics is provided in Table 4, summarizing their respective culture systems, tumor microenvironment recapitulation, genetic stability, and strengths/limitations in drug screening.

TABLE 4

| 3D models | Culture system | Recapitulation of TME | Genetic stability | Drug screening/prediction strengths | Drug screening/prediction limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASCs-derived pancreatic organoids | Require hydrogel and multiple growth factors to promote progenitor cell expansion, differentiation, and self-assembly into organoids | Can form a personalized tumor microenvironment through co-culture with patient-matched immune or stromal cells (Tsai et al., 2018; Tsai et al., 2018) | Key genetic mutations, transcriptomic profiles, histological architecture, and intratumoral heterogeneity of the primary tumor can be maintained long-term (Sljukic et al., 2025) | (1) Capable of long-term, stable expansion (2) Multi-cellular characteristics recapitulate the complexity of the original tumor |

(1)High cost (2) Dependent on biopsy; difficult to obtain samples from benign diseases (3) Lack of vascularization |

| iPSCs-derived or ESCs-derived pancreatic organoids | Following in vitro induction to pancreatic progenitor cells, directed differentiation into specific lineages occurs in hydrogel with specific growth factors; the culture medium composition is more complex | It holds the potential to differentiate into multiple lineages from an isogenic origin, allowing for the study of tumor microenvironments shaped by specific genetic backgrounds. (Takeuchi et al., 2025) | The reprogramming process may introduce genetic mutations (Yan et al., 2023) | (1) Solves the problem of difficult tissue sourcing for benign diseases (Hohwieler et al., 2017) (2) Enables study of disease pathogenesis in specific genetic contexts, allowing for the investigation of early intervention strategies (Merkle et al., 2021) |

(1) Complex, time-consuming, and costly construction process (2) Lack of acquired cancer gene mutations (Yan et al., 2023) (3) Incomplete simulation of pancreatic maturity (Huang et al., 2021) |

| Pancreatic spheroids | Spheroids are constructed by scaffold-based or scaffold-free methods. The culture medium is relatively simple, primarily supporting basic cell growth and aggregation. (Jamshidi et al., 2025) | (1) Simulates the physical barrier through tumor cell-stromal cell interactions (2) Recapitulates the intratumoral nutrient gradient and hypoxic core |

easily lost during long-term culture | (1) Short construction time, suitable for high-throughput drug screening (2) Simulates drug diffusion gradient (3) Can simulate cell-cell interactions |

(1) Short spheroid survival time (2) Requires a large number of cells |

| Pancreatic 3D culture on chip | Mature organoids/spheroids are placed in chip chambers, preserving their 3D structure and cell polarity | (1) Simulates tumor-induced angiogenesis (2) Allows precise control over multiple microenvironmental factors (Li et al., 2023) (3) Enables 3D interactions among tumor cells, stroma, vasculature, and immune components |

Depends on the type of 3D cultured cells placed on the chip | (1) Microfluidic models require minimal cells (2) Enables real-time monitoring of 3D culture dynamics (Ruan et al., 2025) (3)Accelerates organoid cell differentiation and maturation (4) Allows gradient drug administration, simulating plasma concentration gradients (Shen et al., 2020) |

(1) High technical difficulty and cost (2) Lacks unified technical evaluation standards |

Comparison of pancreatic exocrine gland 3D models.

3 Pancreatic organoids and spheroids for drug screening and precision medicine

The current applications of pancreatic 3D organoid or spheroid culture are primarily in pancreatic cancer. Organoids have shown 100% sensitivity and 93% specificity in predicting drug response, indicating their significant potential for high-throughput drug screening and precision medicine (Vlachogiannis et al., 2018). Spheroid models exhibit higher chemical resistance when responding to drug efficacy, simulating the TME and providing greater predictive value for drug effectiveness (Jamshidi et al., 2025). With the development of various 3D model construction methods and the integration of omics technologies, organoids and spheroids will continue to advance pancreatic cancer research and treatment.

3.1 High-throughput drug screening

The current translational success rate of drug development is only 5%, resulting in significant resource waste; the main reason is that existing models primarily rely on 2D cell cultures and animal models, the former of which fails to simulate the in vivo environment and reflect disease heterogeneity, while the latter suffers from species differences, resulting in a lower success rate in drug development (Brancato et al., 2020). While patient-derived xenografts (PDXs) faithfully maintain tumor heterogeneity and remain valuable for preclinical studies, their utility is constrained by prolonged establishment times (typically 4–6 months), high maintenance costs, and limited throughput capacity (Lau et al., 2020). In contrast, 3D culture systems offer several distinct advantages: (1) They enable high-throughput screening in standardized 96- or 384-well formats with establishment times of just days to weeks (Hung et al., 2024; Longati et al., 2013; Wong et al., 2019). (2) They permit precise control over the tumor microenvironment, including adjustable extracellular matrix composition, stromal cell populations, and biophysical gradients that are difficult to manipulate in PDXs (Debruyne et al., 2024); (3) They better preserve human tumor metabolism without murine contamination while allowing real-time metabolic monitoring (Griffin, 2006; Longati et al., 2013). and (4) They rapidly recapitulate critical tumor phenotypes like chemoresistance and invasion - for instance, pancreatic cancer cell migration increases threefold when co-cultured with CAFs in 3D models, with drug resistance patterns emerging within weeks rather than months (Krulikas et al., 2018; Wong et al., 2019); Although 3D cultures cannot fully replace PDXs for in vivo validation, they provide a scalable, cost-effective platform for preliminary drug screening and mechanistic studies that complements PDX models in the drug development pipeline.

Despite their advantages, current 3D models face several limitations in drug screening applications. First, heterogeneity in morphology, cell composition, and spatial organization compromises experimental reproducibility (Ma et al., 2021). Standardized bioengineering approaches (summarized in Table 5) using automated platforms are addressing this challenge by improving model consistency. Second, conventional endpoint assays (e.g., ATP measurement) lack spatiotemporal resolution for dynamic drug response assessment in 3D systems (Deben et al., 2023). High-content imaging technologies now enable real-time, multidimensional analysis while preserving 3D architecture. Researchers such as Shoko Tsukamoto have successfully utilized real-time dynamic imaging technologies to systematically monitor organoids, elucidating the heterogeneous growth characteristics of patient-derived organoids and their differential drug response patterns (Fraietta and Gasparri, 2016; Tsukamoto et al., 2025). However, the resulting data deluge presents new challenges, driving development of AI-based analytical tools, For example, Jonathan M. Matthews and others have invented software for the automated identification, tracking, and analysis of individual organoid dynamics, applied for real-time monitoring of pancreatic cancer organoids, with a tracking accuracy maintained at over 89% (Matthews et al., 2022). These converging technological advances are establishing a new paradigm for high-precision organoid drug screening.

TABLE 5

| Model type | Construction method | Constructed cells/tissues | Application | Detection indicators | Advantages | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spheroid | Droplet Extrusion 3D Bioprinting (DEP) | BxPC-3 cell line, normal human dermal fibroblasts | Simulates the stromal abundance features of pancreatic cancer tissues, constructing a drug screening platform that reflects drug resistance characteristics of pancreatic cancer | Cell viability | The DEP system prints in combination with GelMA hydrogel, achieving high throughput while avoiding contamination with animal-derived components from Matrigel | Huang et al. (2023) |

| Spheroid | Magnetic 3D Bioprinting | primary patient-derived pancreas cancer cells and CAFs | Constructs a high-throughput drug screening platform for primary pancreatic cancer | Cell viability | The first large-scale screening effort, screening over 150,000 small molecules | Fernandez-Vega et al. (2022) |

| Organoids | Automated liquid handling system, CRISPR-Cas9 | PC02 and PC02e cell lines | Constructs a high-throughput drug screening platform based on 3D culture and improves personalized medicine for pancreatic cancer through gene editing combined with drug screening | Cell viability | Combines drug screening with CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing to screen drugs targeting common PDAC driver gene mutations, identifying populations sensitive to targeted therapies, with high-throughput screening of 1,172 drugs | Hirt et al. (2022) |

| Pancreatic organoid chip | Microfluidic Platform | Constructs organoids from patient tumor tissues | Constructs an automated, high-throughput microfluidic 3D organoid culture and analysis system to facilitate preclinical research | Cell apoptosis | Supports real-time analysis of organoids, and the valve control of the microfluidic platform is conducive to high-throughput drug screening | Schuster et al. (2020) |

| Panc-1 cell line, fibroblast cells | Constructs an innovative surface microfluidic platform with quadrants to assess the effects of the extracellular matrix on tumor invasiveness, as well as the responses to chemotherapeutic agents | Cell viability | Integrates 3D tumor spheroids, stromal cells, and ECM microenvironments, enabling multi-drug screening and in situ analysis of invasiveness, providing a precise drug screening platform | Seyfoori et al. (2025) |

Bioengineering methods for constructing pancreatic 3D models for drug screening.

3.2 Precision medicine

Current first-line therapy for pancreatic cancer relies on cytotoxic agents such as gemcitabine; however, therapeutic efficacy is constrained by frequent drug resistance and the lack of effective targeted treatments (Knudsen et al., 2016). These therapeutic failures arise from multiple factors, including genetic heterogeneity, the complexity of the TME, immune suppression, and metabolic reprogramming (Beatty et al., 2021). Developing precision-medicine strategies tailored to individual patient characteristics has become a critical approach for overcoming current therapeutic limitations. Because patient-derived organoids (PDOs) retain the molecular and morphological features of primary tumors and allow drug screening within a short timeframe, they have become an essential platform for supporting precision-medicine research and applications. Foundational work on using PDOs to predict drug responses in pancreatic disease began in 2015, when Ling Huang and colleagues first demonstrated drug-effect assessment using pancreatic cancer organoids (Huang et al., 2015). Subsequently, in 2018, Tiriac and colleagues correlated PDO drug-sensitivity profiles with the clinical outcomes of corresponding patients, providing preliminary validation of their predictive potential (Tiriac et al., 2018). Currently, the application of PDOs in pancreatic-cancer precision medicine focuses primarily on the following areas: (1) designing targeted treatment or combination-therapy strategies based on PDO responses to various drugs to improve therapeutic outcomes; (2) elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying tumor heterogeneity and integrating multi-omics analyses to identify personalized therapeutic targets in pancreatic cancer; (3) identifying mechanisms associated with tumor-cell drug resistance using PDOs derived from resistant patients, thereby providing a theoretical basis for overcoming resistance (Xiang et al., 2024).

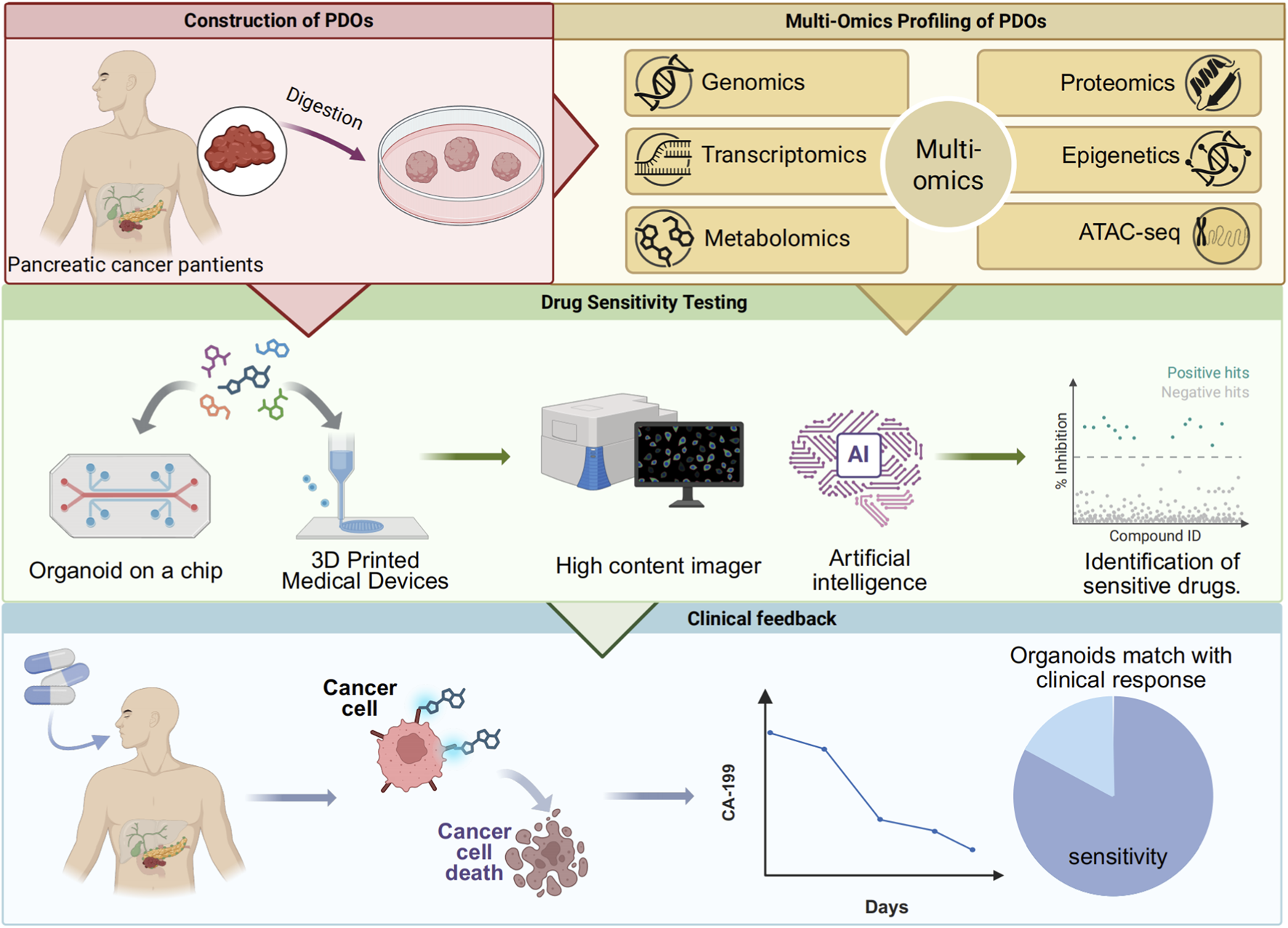

3.3 Bridging basic research and clinical practice with pancreatic PDOs

PDO models hold significant value in the precision medicine of pancreatic cancer. Their core utility lies in establishing a complete workflow of “organoid establishment, multi-omics analysis, drug sensitivity testing, clinical feedback and validation” (Figure 3). However, crucially, the clinical implementation of this workflow is contingent upon the efficiency of its initial step: the generation and testing of PDOs must be completed within the clinical decision-making window. Although drug screening based on the genomic features of PDOs has shown potential to extend patient survival, traditional PDO generation methods are time-consuming. This prolonged timeline often misaligns with the rapidly progressive nature of pancreatic cancer, ultimately limiting patient benefit in practice (Sarno et al., 2025). Consequently, improving the time efficiency of PDO generation and testing is pivotal for advancing its clinical translation. Currently, studies have demonstrated that the PDO testing cycle can be substantially shortened through technical optimization. For instance, constructing PDOs from biopsy samples prior to neoadjuvant therapy, coupled with 3D printing technology, can reduce the median turnaround time for drug sensitivity testing to 48 days (Seppälä et al., 2020), which precedes the conventional start time for postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy (typically 8–12 weeks after surgery). Furthermore, Wu et al. successfully generated PDOs from circulating tumor cells, shortening the culture cycle to approximately 3 weeks. The drug sensitivity results showed a significant correlation with patient clinical response, providing a feasible pathway for real-time individualized therapy. However, the small sample size of this study necessitates validation of its predictive accuracy in larger cohorts (Wu et al., 2022).

FIGURE 3

An integrated pathway of organoid establishment, multi-omics analysis, drug sensitivity testing, and clinical feedback for precision medicine.

Following successful organoid establishment, genetic sequencing revealed that 79.6% of organoids harbored potentially targetable genetic alterations. Targeting these mutations with combination therapies of targeted agents and conventional chemotherapeutic drugs has become a pivotal pathway for leveraging PDOs to advance precision therapy (Sarno et al., 2025). For instance, a study established a biobank of 260 pancreatic cancer PDOs. Metabolomic data indicated a significant elevation in cholesterol metabolism levels in pancreatic cancer. Statins were found to selectively inhibit the growth of chemotherapy resistant organoids in vitro. Based on this finding, a phase II clinical trial (NCT06241352) was conducted, demonstrating that combination therapy with statins and traditional chemotherapy reduced CA19-9 or CEA levels by more than 20% in 70.3% of patients after 1 month, with tumor volume shrinkage observed in most patients (Li et al., 2025). Furthermore, addressing the most prevalent driver gene, KRAS (mutation rate >90%), and resistance to its inhibitors (Beatty et al., 2021; Knudsen et al., 2016), research utilizing KRAS G12D-mutant PDO models through multi-omics analysis identified activation of the EMT and the PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway as key bypass resistance mechanisms. This provides a direct rationale for designing combination treatment strategies (Dilly et al., 2024). In summary, the integration of organoid models with multi-omics analysis can uncover PDAC resistance mechanisms from multiple dimensions—such as metabolic reprogramming and signaling pathway dysregulation and identify novel therapeutic targets.

To effectively translate PDO drug sensitivity and multi-omics profiles into clinical guidance, it is imperative to advance beyond static testing toward high-content, dynamic analytical platforms. On one hand, technologies such as quantitative live-cell imaging enable real-time monitoring of drug responses at the level of single-cell signaling pathways. For example, by tracking the dynamic activities of ERK/AMPK kinases in real time, temporal dependencies of different kinases during organoid growth can be revealed, informing combination therapy strategies (Tsukamoto et al., 2025). On the other hand, intelligent imaging platforms, represented by tools like OrganoID, allow label-free, high-throughput monitoring of macroscopic dynamic changes in organoid number, size, and morphology. These platforms integrate artificial intelligence algorithms for real-time analysis, using the acquired imaging data to accurately assess drug efficacy based on organoid growth (Le Compte et al., 2023; Matthews et al., 2022). Together, these technologies are advancing drug sensitivity testing from simple endpoint cytotoxicity assessments toward multidimensional, dynamic, and precise analysis.

Building upon the aforementioned technologies, the feasibility and value of PDO-guided clinical therapy have received strong support from prospective studies. The largest prospective study to date demonstrated that treatment plans based on PDO drug sensitivity results enabled 91% of pancreatic cancer patients to receive matched personalized therapy, significantly improving progression-free survival and objective response rates, thereby substantiating its clinical utility (Boilève et al., 2024). Concurrently, efforts to standardize and normalize organoid technology are accelerating: an expert consensus published in 2024 systematically standardized the drug sensitivity testing workflow, signifying that the technology has reached a level suitable for clinical application and holds promise for reducing treatment risks and costs. Furthermore, the FDA has adopted organ-on-a-chip data to support a new drug clinical trial (NCT04658472) (Querol et al., 2023; Xiang et al., 2024). Advances in biotechnology coupled with the establishment of standards are driving the translation of PDOs from a research tool into routine clinical practice.

However, organoids also face limitations in precision medicine. Currently, constructing composite organoids that contain both endocrine and exocrine tissues remains a significant challenge (Chen et al., 2024). Additionally, there are currently no globally unified standard protocols for the culture medium formulations and growth conditions of patient-derived organoids (PDOs). This lack of harmonized standards hinders direct comparison and integration of data across different laboratories or medical centers, thereby impeding large-scale clinical application.

4 Conclusion and perspectives

With the evolution of the precision medicine paradigm, PDOs are reshaping the decision-making framework for pancreatic cancer treatment by integrating genomic features, dynamic drug sensitivity testing, and clinical prognostic data. In the future, it is essential to further explore the interdisciplinary integration of PDOs with liquid biopsies and artificial intelligence predictive models to achieve comprehensive optimization of treatment strategies.

However, there remains significant potential for further advancements in pancreatic organoid and spheroids research. Firstly, the tumor microbiome has the potential to impact the response of pancreatic cancer to drug therapy (LaCourse et al., 2022). As such, there is a need for the construction of pancreatic 3D co-cultured with microbes in the future to better guide drug therapy for pancreatic tumors. Moreover, there currently lacks pancreatic models for certain benign pancreatic diseases, such as chronic pancreatitis. Yet, the integration of gene editing technologies, such as CRISPR, with 3D cultures is poised to facilitate the development of models capable of predicting in vivo drug responses for a broader spectrum of diseases in the future (Tuveson and Clevers, 2019).

Statements

Author contributions

XT: Visualization, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Investigation. BH: Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Software. XY: Writing – original draft, Data curation, Methodology. PW: Conceptualization, Writing – review and editing, Funding acquisition. LH: Funding acquisition, Writing – review and editing, Supervision, Validation.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was primarily supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82270679 and No. 82570769 to LH, 82104257 to PW), Hebei Natural Science Foundation (No. H2025101001 to PW).

Acknowledgments

Figures were created with biorender.com.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

3D, three-dimensional; PDOs, patient-derived organoids; PDAC, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; ASCs, adult stem cells; ESCs, embryonic stem cells; iPSCs, induced pluripotent stem cells; CAFs, cancer-associated fibroblasts; TME, tumor microenvironment; PSCs, pancreatic stellate cells; EMT, epithelial-mesenchymal transition.

References

1

Beatty G. L. Werba G. Lyssiotis C. A. Simeone D. M. (2021). The biological underpinnings of therapeutic resistance in pancreatic cancer. Genes Dev.35, 940–962. 10.1101/gad.348523.121

2

Beutel A. K. Schütte L. Scheible J. Roger E. Müller M. Perkhofer L. et al (2021). A prospective feasibility trial to challenge patient-derived pancreatic cancer organoids in predicting treatment response. Cancers (Basel)13, 2539. 10.3390/cancers13112539

3

Białkowska K. Komorowski P. Bryszewska M. Miłowska K. (2020). Spheroids as a type of three-dimensional cell cultures-examples of methods of preparation and the Most important application. Int. J. Mol. Sci.21, 6225. 10.3390/ijms21176225

4

Bilir B. Kucuk O. Moreno C. S. (2013). Wnt signaling blockage inhibits cell proliferation and migration, and induces apoptosis in triple-negative breast cancer cells. J. Transl. Med.11, 280. 10.1186/1479-5876-11-280

5

Boilève A. Cartry J. Goudarzi N. Bedja S. Mathieu J. R. R. Bani M. A. et al (2024). Organoids for functional precision medicine in advanced pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterology167, 961–976.e913. 10.1053/j.gastro.2024.05.032

6

Boj S. F. Hwang C. I. Baker L. A. Chio I. I. Engle D. D. Corbo V. et al (2015). Organoid models of human and mouse ductal pancreatic cancer. Cell160, 324–338. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.12.021

7

Brancato V. Oliveira J. M. Correlo V. M. Reis R. L. Kundu S. C. (2020). Could 3D models of cancer enhance drug screening?Biomaterials232, 119744. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.119744

8

Breunig M. Merkle J. Wagner M. Melzer M. K. Barth T. F. E. Engleitner T. et al (2021). Modeling plasticity and dysplasia of pancreatic ductal organoids derived from human pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell28, 1105–1124.e1119. 10.1016/j.stem.2021.03.005

9

Castiaux A. D. Spence D. M. Martin R. S. (2019). Review of 3D cell culture with analysis in microfluidic systems. Anal. Methods11, 4220–4232. 10.1039/c9ay01328h

10

Chen J. Lu J. Wang S. N. Miao C. Y. (2024). Application and challenge of pancreatic organoids in therapeutic research. Front. Pharmacol.15, 1366417. 10.3389/fphar.2024.1366417

11

Choi D. Gonzalez-Suarez A. M. Dumbrava M. G. Medlyn M. de Hoyos-Vega J. M. Cichocki F. et al (2024). Microfluidic organoid cultures derived from pancreatic cancer biopsies for personalized testing of chemotherapy and immunotherapy. Adv. Sci. (Weinh)11, e2303088. 10.1002/advs.202303088

12

Corrò C. Novellasdemunt L. Li V. S. W. (2020). A brief history of organoids. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol.319, C151–c165. 10.1152/ajpcell.00120.2020

13

Dayton T. L. Alcala N. Moonen L. den Hartigh L. Geurts V. Mangiante L. et al (2023). Druggable growth dependencies and tumor evolution analysis in patient-derived organoids of neuroendocrine neoplasms from multiple body sites. Cancer Cell41, 2083–2099.e2089. 10.1016/j.ccell.2023.11.007

14

Deben C. De La Hoz E. C. Compte M. L. Van Schil P. Hendriks J. M. H. Lauwers P. et al (2023). OrBITS: label-free and time-lapse monitoring of patient derived organoids for advanced drug screening. Cell Oncol. (Dordr)46, 299–314. 10.1007/s13402-022-00750-0

15

Debruyne A. C. Okkelman I. A. Heymans N. Pinheiro C. Hendrix A. Nobis M. et al (2024). Live microscopy of multicellular spheroids with the multimodal near-infrared nanoparticles reveals differences in oxygenation gradients. ACS Nano18, 12168–12186. 10.1021/acsnano.3c12539

16

Dilly J. Hoffman M. T. Abbassi L. Li Z. Paradiso F. Parent B. D. et al (2024). Mechanisms of resistance to oncogenic KRAS inhibition in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Discov.14, 2135–2161. 10.1158/2159-8290.Cd-24-0177

17

Eso Y. Shimizu T. Takeda H. Takai A. Marusawa H. (2020). Microsatellite instability and immune checkpoint inhibitors: toward precision medicine against gastrointestinal and hepatobiliary cancers. J. Gastroenterol.55, 15–26. 10.1007/s00535-019-01620-7

18

Fan F. He Z. Kong L. L. Chen Q. Yuan Q. Zhang S. et al (2016). Pharmacological targeting of kinases MST1 and MST2 augments tissue repair and regeneration. Sci. Transl. Med.8, 352ra108. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf2304

19

Fernandez-Vega V. Hou S. Plenker D. Tiriac H. Baillargeon P. Shumate J. et al (2022). Lead identification using 3D models of pancreatic cancer. SLAS Discov.27, 159–166. 10.1016/j.slasd.2022.03.002

20

Firuzi O. Che P. P. El Hassouni B. Buijs M. Coppola S. Löhr M. et al (2019). Role of c-MET inhibitors in overcoming drug resistance in spheroid models of primary human pancreatic cancer and stellate cells. Cancers (Basel)11, 638. 10.3390/cancers11050638

21

Fraietta I. Gasparri F. (2016). The development of high-content screening (HCS) technology and its importance to drug discovery. Expert Opin. Drug Discov.11, 501–514. 10.1517/17460441.2016.1165203

22

Friedrich J. Seidel C. Ebner R. Kunz-Schughart L. A. (2009). Spheroid-based drug screen: considerations and practical approach. Nat. Protoc.4, 309–324. 10.1038/nprot.2008.226

23

Giustarini G. Teng G. Pavesi A. Adriani G. (2023). Characterization of 3D heterocellular spheroids of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma for the study of cell interactions in the tumor immune microenvironment. Front. Oncol.13, 1156769. 10.3389/fonc.2023.1156769

24

Gout J. Ekizce M. Roger E. Kleger A. (2025). Pancreatic organoids as cancer avatars for true personalized medicine. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev.224, 115642. 10.1016/j.addr.2025.115642

25

Grapin-Botton A. (2016). Three-dimensional pancreas organogenesis models. Diabetes Obes. Metab.18 (Suppl. 1), 33–40. 10.1111/dom.12720

26

Griffin R. J. (2006). Radiobiology for the radiologist, 6th edition. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys.66, 627. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.06.027

27

Gu Z. Du Y. Zhao X. Wang C. (2021). Tumor microenvironment and metabolic remodeling in gemcitabine-based chemoresistance of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Lett.521, 98–108. 10.1016/j.canlet.2021.08.029

28

Guinn S. Kinny-Köster B. Tandurella J. A. Mitchell J. T. Sidiropoulos D. N. Loth M. et al (2024). Transfer learning reveals cancer-associated fibroblasts are associated with epithelial-mesenchymal transition and inflammation in cancer cells in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res.84, 1517–1533. 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-23-1660

29

Gündel B. Liu X. Löhr M. Heuchel R. (2021). Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: preclinical in vitro and ex vivo models. Front. Cell Dev. Biol.9, 741162. 10.3389/fcell.2021.741162

30

Hald J. Hjorth J. P. German M. S. Madsen O. D. Serup P. Jensen J. (2003). Activated Notch1 prevents differentiation of pancreatic acinar cells and attenuate endocrine development. Dev. Biol.260, 426–437. 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00326-9

31

Hart P. A. Conwell D. L. (2020). Chronic pancreatitis: managing a difficult disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol.115, 49–55. 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000421

32

Hart A. Papadopoulou S. Edlund H. (2003). Fgf10 maintains notch activation, stimulates proliferation, and blocks differentiation of pancreatic epithelial cells. Dev. Dyn.228, 185–193. 10.1002/dvdy.10368

33

Haumaitre C. Lenoir O. Scharfmann R. (2008). Histone deacetylase inhibitors modify pancreatic cell fate determination and amplify endocrine progenitors. Mol. Cell Biol.28, 6373–6383. 10.1128/mcb.00413-08

34

Hernández-Hatibi S. Borau C. Martínez-Bosch N. Navarro P. García-Aznar J. M. Guerrero P. E. (2025). Quantitative characterization of the 3D self-organization of PDAC tumor spheroids reveals cell type and matrix dependence through advanced microscopy analysis. Apl. Bioeng.9, 016116. 10.1063/5.0242490

35

Hirshorn S. T. Steele N. Zavros Y. (2021). Modeling pancreatic pathophysiology using genome editing of adult stem cell-derived and induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived organoids. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol.320, G1142–g1150. 10.1152/ajpgi.00329.2020

36

Hirt C. K. Booij T. H. Grob L. Simmler P. Toussaint N. C. Keller D. et al (2022). Drug screening and genome editing in human pancreatic cancer organoids identifies drug-gene interactions and candidates for off-label treatment. Cell Genom2, 100095. 10.1016/j.xgen.2022.100095

37

Hohwieler M. Illing A. Hermann P. C. Mayer T. Stockmann M. Perkhofer L. et al (2017). Human pluripotent stem cell-derived acinar/ductal organoids generate human pancreas upon orthotopic transplantation and allow disease modelling. Gut66, 473–486. 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312423

38

Huang L. Holtzinger A. Jagan I. BeGora M. Lohse I. Ngai N. et al (2015). Ductal pancreatic cancer modeling and drug screening using human pluripotent stem cell- and patient-derived tumor organoids. Nat. Med.21, 1364–1371. 10.1038/nm.3973

39

Huang L. Desai R. Conrad D. N. Leite N. C. Akshinthala D. Lim C. M. et al (2021). Commitment and oncogene-induced plasticity of human stem cell-derived pancreatic acinar and ductal organoids. Cell Stem Cell28, 1090–1104.e1096. 10.1016/j.stem.2021.03.022

40

Huang B. Wei X. Chen K. Wang L. Xu M. (2023). Bioprinting of hydrogel beads to engineer pancreatic tumor-stroma microtissues for drug screening. Int. J. Bioprint9, 676. 10.18063/ijb.676

41

Huch M. Bonfanti P. Boj S. F. Sato T. Loomans C. J. van de Wetering M. et al (2013). Unlimited in vitro expansion of adult bi-potent pancreas progenitors through the Lgr5/R-spondin axis. Embo J.32, 2708–2721. 10.1038/emboj.2013.204

42

Hughes C. S. Postovit L. M. Lajoie G. A. (2010). Matrigel: a complex protein mixture required for optimal growth of cell culture. Proteomics10, 1886–1890. 10.1002/pmic.200900758

43

Hung H. C. Mao T. L. Fan M. H. Huang G. Z. Minhalina A. P. Chen C. L. et al (2024). Enhancement of tumorigenicity, spheroid niche, and drug resistance of pancreatic cancer cells in three-dimensional culture system. J. Cancer15, 2292–2305. 10.7150/jca.87494

44

Hwang H. J. Oh M. S. Lee D. W. Kuh H. J. (2019). Multiplex quantitative analysis of stroma-mediated cancer cell invasion, matrix remodeling, and drug response in a 3D co-culture model of pancreatic tumor spheroids and stellate cells. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res.38, 258. 10.1186/s13046-019-1225-9

45

Hyman J. M. Firestone A. J. Heine V. M. Zhao Y. Ocasio C. A. Han K. et al (2009). Small-molecule inhibitors reveal multiple strategies for hedgehog pathway blockade. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.106, 14132–14137. 10.1073/pnas.0907134106

46

Ishiguro T. Ohata H. Sato A. Yamawaki K. Enomoto T. Okamoto K. (2017). Tumor-derived spheroids: relevance to cancer stem cells and clinical applications. Cancer Sci.108, 283–289. 10.1111/cas.13155

47

Jamshidi N. Jamshidi N. Modarresi Chahardehi A. Shams E. Chaleshi V. (2025). A promising breakthrough in pancreatic cancer research: the potential of spheroids as 3D models. Bioimpacts15, 30241. 10.34172/bi.30241

48

Jang Y. Kang S. Han H. Kang C. M. Cho N. H. Kim B. G. (2024). Fibrosis-encapsulated tumoroid, A solid cancer assembloid model for cancer research and drug screening. Adv. Healthc. Mater13, e2402391. 10.1002/adhm.202402391

49

Jennings R. E. Berry A. A. Strutt J. P. Gerrard D. T. Hanley N. A. (2015). Human pancreas development. Development142, 3126–3137. 10.1242/dev.120063

50

Kawasaki K. Toshimitsu K. Matano M. Fujita M. Fujii M. Togasaki K. et al (2020). An organoid biobank of neuroendocrine neoplasms enables genotype-phenotype mapping. Cell183, 1420–1435.e1421. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.10.023

51

Keefe M. D. Wang H. De La O. J. Khan A. Firpo M. A. Murtaugh L. C. (2012). β-catenin is selectively required for the expansion and regeneration of mature pancreatic acinar cells in mice. Dis. Model Mech.5, 503–514. 10.1242/dmm.007799

52

Kim J. Koo B. K. Knoblich J. A. (2020). Human organoids: model systems for human biology and medicine. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol.21, 571–584. 10.1038/s41580-020-0259-3

53

Kim H. Cho S. W. Kim H. N. (2025). Vascularized Tumor-on-a-Chip model as a platform for studying tumor-microenvironment-drug interaction. Macromol. Biosci.25, e00240. 10.1002/mabi.202500240

54

Kleinman H. K. Martin G. R. (2005). Matrigel: basement membrane matrix with biological activity. Semin. Cancer Biol.15, 378–386. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2005.05.004

55

Knudsen E. S. O'Reilly E. M. Brody J. R. Witkiewicz A. K. (2016). Genetic diversity of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and opportunities for precision medicine. Gastroenterology150, 48–63. 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.08.056

56

Krulikas L. J. McDonald I. M. Lee B. Okumu D. O. East M. P. Gilbert T. S. K. et al (2018). Application of integrated drug screening/kinome analysis to identify inhibitors of gemcitabine-resistant pancreatic cancer cell growth. SLAS Discov.23, 850–861. 10.1177/2472555218773045

57

LaCourse K. D. Zepeda-Rivera M. Kempchinsky A. G. Baryiames A. Minot S. S. Johnston C. D. et al (2022). The cancer chemotherapeutic 5-fluorouracil is a potent Fusobacterium nucleatum inhibitor and its activity is modified by intratumoral microbiota. Cell Rep.41, 111625. 10.1016/j.celrep.2022.111625

58

Lau H. C. H. Kranenburg O. Xiao H. Yu J. (2020). Organoid models of gastrointestinal cancers in basic and translational research. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.17, 203–222. 10.1038/s41575-019-0255-2

59

Le Compte M. De La Hoz E. C. Peeters S. Fortes F. R. Hermans C. Domen A. et al (2023). Single-organoid analysis reveals clinically relevant treatment-resistant and invasive subclones in pancreatic cancer. NPJ Precis. Oncol.7, 128. 10.1038/s41698-023-00480-y

60

Leszczynska K. B. Freitas-Huhtamäki A. Jayaprakash C. Dzwigonska M. Vitorino F. N. L. Horth C. et al (2024). H2A.Z histone variants facilitate HDACi-dependent removal of H3.3K27M mutant protein in pediatric high-grade glioma cells. Cell Rep.43, 113707. 10.1016/j.celrep.2024.113707

61

Li W. C. Rukstalis J. M. Nishimura W. Tchipashvili V. Habener J. F. Sharma A. et al (2010). Activation of pancreatic-duct-derived progenitor cells during pancreas regeneration in adult rats. J. Cell Sci.123, 2792–2802. 10.1242/jcs.065268

62

Li W. Zhou Z. Zhou X. Khoo B. L. Gunawan R. Chin Y. R. et al (2023). 3D biomimetic models to reconstitute tumor microenvironment in vitro: spheroids, organoids, and Tumor-on-a-Chip. Adv. Healthc. Mater12, e2202609. 10.1002/adhm.202202609

63

Li Y. Tang S. Wang H. Zhu H. Lu Y. Zhang Y. et al (2025). A pancreatic cancer organoid biobank links multi-omics signatures to therapeutic response and clinical evaluation of statin combination therapy. Cell Stem Cell32, 1369–1389.e1314. 10.1016/j.stem.2025.07.008

64

Liu Y. Ruan X. Li J. Wang B. Chen J. Wang X. et al (2022). The osteocyte stimulated by Wnt agonist SKL2001 is a safe osteogenic niche improving bioactivities in a polycaprolactone and cell integrated 3D module. Cells 1111, 831. 10.3390/cells11050831

65

Logsdon C. D. Moessner J. Williams J. A. Goldfine I. D. (1985). Glucocorticoids increase amylase mRNA levels, secretory organelles, and secretion in pancreatic acinar AR42J cells. J. Cell Biol.100, 1200–1208. 10.1083/jcb.100.4.1200

66

Longati P. Jia X. Eimer J. Wagman A. Witt M. R. Rehnmark S. et al (2013). 3D pancreatic carcinoma spheroids induce a matrix-rich, chemoresistant phenotype offering a better model for drug testing. BMC Cancer13, 95. 10.1186/1471-2407-13-95

67

Ma S. Zhao H. Galan E. A. (2021). Integrating engineering, automation, and intelligence to catalyze the biomedical translation of organoids. Adv. Biol. (Weinh)5, e2100535. 10.1002/adbi.202100535

68

Malik S. S. Padmanabhan D. Hull-Meichle R. L. (2023). Pancreas and islet morphology in cystic fibrosis: clues to the etiology of cystic fibrosis-related diabetes. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne)14, 1269139. 10.3389/fendo.2023.1269139

69

Matthews J. M. Schuster B. Kashaf S. S. Liu P. Ben-Yishay R. Ishay-Ronen D. et al (2022). OrganoID: a versatile deep learning platform for tracking and analysis of single-organoid dynamics. PLoS Comput. Biol.18, e1010584. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1010584

70

Meng Q. Xie S. Gray G. K. Dezfulian M. H. Li W. Huang L. et al (2021). Empirical identification and validation of tumor-targeting T cell receptors from circulation using autologous pancreatic tumor organoids. J. Immunother. Cancer9, e003213. 10.1136/jitc-2021-003213

71

Merkle J. Breunig M. Schmid M. Allgöwer C. Krüger J. Melzer M. K. et al (2021). CDKN2A-Mutated pancreatic ductal organoids from induced pluripotent stem cells to model a cancer predisposition syndrome. Cancers (Basel)13, 5139. 10.3390/cancers13205139

72

Merz S. Breunig M. Melzer M. K. Heller S. Wiedenmann S. Seufferlein T. et al (2023). Single-cell profiling of GP2-enriched pancreatic progenitors to simultaneously create acinar, ductal, and endocrine organoids. Theranostics13, 1949–1973. 10.7150/thno.78323

73

Mun K. S. Nathan J. D. Jegga A. G. Wikenheiser-Brokamp K. A. Abu-El-Haija M. Naren A. P. (2022). Personalized medicine approaches in cystic fibrosis related pancreatitis. Am. J. Transl. Res.14, 7612–7620. Available online at: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9641468/pdf/ajtr0014-7612.pdf

74

Ndlovu R. Deng L. C. Wu J. Li X. K. Zhang J. S. (2018). Fibroblast growth factor 10 in pancreas development and pancreatic cancer. Front. Genet.9, 482. 10.3389/fgene.2018.00482

75

Norgaard G. A. Jensen J. N. Jensen J. (2003). FGF10 signaling maintains the pancreatic progenitor cell state revealing a novel role of notch in organ development. Dev. Biol.264, 323–338. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.08.013

76

Öhlund D. Handly-Santana A. Biffi G. Elyada E. Almeida A. S. Ponz-Sarvise M. et al (2017). Distinct populations of inflammatory fibroblasts and myofibroblasts in pancreatic cancer. J. Exp. Med.214, 579–596. 10.1084/jem.20162024

77

Pagliuca F. W. Millman J. R. Gürtler M. Segel M. Van Dervort A. Ryu J. H. et al (2014). Generation of functional human pancreatic β cells in vitro. Cell159, 428–439. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.040

78

Pan F. C. Wright C. (2011). Pancreas organogenesis: from bud to plexus to gland. Dev. Dyn.240, 530–565. 10.1002/dvdy.22584

79

Pasca di Magliano M. Sekine S. Ermilov A. Ferris J. Dlugosz A. A. Hebrok M. (2006). Hedgehog/ras interactions regulate early stages of pancreatic cancer. Genes Dev.20, 3161–3173. 10.1101/gad.1470806

80

Peng C. Oberstein P. E. (2025). Emerging therapeutic approaches to pancreatic adenocarcinoma: advances and future directions. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol.26, 841–865. 10.1007/s11864-025-01352-2

81

Perche F. Torchilin V. P. (2012). Cancer cell spheroids as a model to evaluate chemotherapy protocols. Cancer Biol. Ther.13, 1205–1213. 10.4161/cbt.21353

82

Perera R. M. Bardeesy N. (2012). Ready, set, go: the EGF receptor at the pancreatic cancer starting line. Cancer Cell22, 281–282. 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.08.019

83

Querol L. Lewis R. A. Hartung H. P. Van Doorn P. A. Wallstroem E. Luo X. et al (2023). An innovative phase 2 proof-of-concept trial design to evaluate SAR445088, a monoclonal antibody targeting complement C1s in chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy. J. Peripher Nerv. Syst.28, 276–285. 10.1111/jns.12551

84

Quintard C. Tubbs E. Jonsson G. Jiao J. Wang J. Werschler N. et al (2024). A microfluidic platform integrating functional vascularized organoids-on-chip. Nat. Commun.15, 1452. 10.1038/s41467-024-45710-4

85

Raghavan S. Winter P. S. Navia A. W. Williams H. L. DenAdel A. Lowder K. E. et al (2021). Microenvironment drives cell state, plasticity, and drug response in pancreatic cancer. Cell184, 6119–6137.e6126. 10.1016/j.cell.2021.11.017

86

Rauth S. Karmakar S. Batra S. K. Ponnusamy M. P. (2021). Recent advances in organoid development and applications in disease modeling. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer1875, 188527. 10.1016/j.bbcan.2021.188527

87

Rezania A. Bruin J. E. Arora P. Rubin A. Batushansky I. Asadi A. et al (2014). Reversal of diabetes with insulin-producing cells derived in vitro from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Biotechnol.32, 1121–1133. 10.1038/nbt.3033

88

Ruan J. Gao C. Wang R. Hu B. Long R. Hacimuftuoglu A. et al (2025). A novel dual-effect bimodal chip cancer research platform: chips system interconnected vascularized tumor organoids culture with real-time exploration and detection from bench to bedside. Cancer Lett., 218110. 10.1016/j.canlet.2025.218110

89

Ryu N. E. Lee S. H. Park H. (2019). Spheroid culture system methods and applications for mesenchymal stem cells. Cells8, 1620. 10.3390/cells8121620

90

Sarno F. Tenorio J. Perea S. Medina L. Pazo-Cid R. Juez I. et al (2025). A phase III randomized trial of integrated genomics and avatar models for personalized treatment of pancreatic cancer: the AVATAR trial. Clin. Cancer Res.31, 278–287. 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-23-4026

91

Sasaki T. Kahn M. (2014). Inhibition of β-catenin/p300 interaction proximalizes mouse embryonic lung epithelium. Transl. Respir. Med.2, 8. 10.1186/s40247-014-0008-1

92

Schuster B. Junkin M. Kashaf S. S. Romero-Calvo I. Kirby K. Matthews J. et al (2020). Automated microfluidic platform for dynamic and combinatorial drug screening of tumor organoids. Nat. Commun.11, 5271. 10.1038/s41467-020-19058-4

93

Schuth S. Le Blanc S. Krieger T. G. Jabs J. Schenk M. Giese N. A. et al (2022). Patient-specific modeling of stroma-mediated chemoresistance of pancreatic cancer using a three-dimensional organoid-fibroblast co-culture system. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res.41, 312. 10.1186/s13046-022-02519-7

94

Seino T. Kawasaki S. Shimokawa M. Tamagawa H. Toshimitsu K. Fujii M. et al (2018). Human pancreatic tumor organoids reveal loss of stem cell niche factor dependence during disease progression. Cell Stem Cell22, 454–467.e456. 10.1016/j.stem.2017.12.009

95

Seppälä T. T. Zimmerman J. W. Sereni E. Plenker D. Suri R. Rozich N. et al (2020). Patient-derived organoid pharmacotyping is a clinically tractable strategy for precision medicine in pancreatic cancer. Ann. Surg.272, 427–435. 10.1097/sla.0000000000004200

96

Seyfoori A. Liu K. Caruncho H. J. Walter P. B. Akbari M. (2025). Tumoroid-On-a-Plate (ToP): physiologically relevant cancer model generation and therapeutic screening. Adv. Healthc. Mater14, e2402060. 10.1002/adhm.202402060

97

Shao S. Delk N. A. Jones C. N. (2024). A microphysiological system reveals neutrophil contact-dependent attenuation of pancreatic tumor progression by CXCR2 inhibition-based immunotherapy. Sci. Rep.14, 14142. 10.1038/s41598-024-64780-4

98

Shen S. Zhang X. Zhang F. Wang D. Long D. Niu Y. (2020). Three-gradient constructions in a flow-rate insensitive microfluidic system for drug screening towards personalized treatment. Talanta208, 120477. 10.1016/j.talanta.2019.120477

99

Shen X. Li M. Wang C. Liu Z. Wu K. Wang A. et al (2022). Hypoxia is fine-tuned by Hif-1α and regulates mesendoderm differentiation through the Wnt/β-Catenin pathway. BMC Biol.20, 219. 10.1186/s12915-022-01423-y

100

Siegel R. L. Miller K. D. Fuchs H. E. Jemal A. (2022). Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J. Clin.72, 7–33. 10.3322/caac.21708

101

Sljukic A. Green Jenkinson J. Niksic A. Prior N. Huch M. (2025). Advances in liver and pancreas organoids: how far we have come and where we go next. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 10.1038/s41575-025-01116-1

102

Song T. Zhang H. Luo Z. Shang L. Zhao Y. (2023). Primary human pancreatic cancer cells cultivation in microfluidic hydrogel microcapsules for drug evaluation. Adv. Sci. (Weinh)10, e2206004. 10.1002/advs.202206004

103

Sun J. Wu W. Tang X. Zhang F. Ju C. Liu R. et al (2021). HDAC6 inhibitor WT161 performs anti-tumor effect on osteosarcoma and synergistically interacts with 5-FU. Biosci. Rep.41. 10.1042/bsr20203905

104

Takeuchi K. Tabe S. Yamamoto Y. Takahashi K. Matsuo M. Ueno Y. et al (2025). Protocol for generating a pancreatic cancer organoid associated with heterogeneous tumor microenvironment. Star. Protoc.6, 103539. 10.1016/j.xpro.2024.103539

105

Tian Z. Yu T. Liu J. Wang T. Higuchi A. (2023). Introduction to stem cells. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci.199, 3–32. 10.1016/bs.pmbts.2023.02.012

106

Tiriac H. Belleau P. Engle D. D. Plenker D. Deschênes A. Somerville T. D. D. et al (2018). Organoid profiling identifies common responders to chemotherapy in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Discov.8, 1112–1129. 10.1158/2159-8290.Cd-18-0349

107

Tong L. Cui W. Zhang B. Fonseca P. Zhao Q. Zhang P. et al (2024). Patient-derived organoids in precision cancer medicine. Med5, 1351–1377. 10.1016/j.medj.2024.08.010

108

Tsai S. McOlash L. Palen K. Johnson B. Duris C. Yang Q. et al (2018). Development of primary human pancreatic cancer organoids, matched stromal and immune cells and 3D tumor microenvironment models. BMC Cancer18, 335. 10.1186/s12885-018-4238-4

109

Tsukamoto S. Huaze Y. Weisheng Z. Machinaga A. Kakiuchi N. Ogawa S. et al (2025). Quantitative live imaging reveals phase dependency of PDAC patient-derived organoids on ERK and AMPK activity. Cancer Sci.116, 724–735. 10.1111/cas.16439

110

Tuveson D. Clevers H. (2019). Cancer modeling meets human organoid technology. Science364, 952–955. 10.1126/science.aaw6985

111

van Renterghem A. W. J. van de Haar J. Voest E. E. (2023). Functional precision oncology using patient-derived assays: bridging genotype and phenotype. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol.20, 305–317. 10.1038/s41571-023-00745-2

112

Verloy R. Privat-Maldonado A. Van Audenaerde J. Rovers S. Zaryouh H. De Waele J. et al (2025). Capturing the heterogeneity of the PDAC tumor microenvironment: novel triple Co-Culture spheroids for drug screening and angiogenic evaluation. Cells14, 450. 10.3390/cells14060450

113

Vlachogiannis G. Hedayat S. Vatsiou A. Jamin Y. Fernández-Mateos J. Khan K. et al (2018). Patient-derived organoids model treatment response of metastatic gastrointestinal cancers. Science359, 920–926. 10.1126/science.aao2774

114

Wang Y. Jeon H. (2022). 3D cell cultures toward quantitative high-throughput drug screening. Trends Pharmacol. Sci.43, 569–581. 10.1016/j.tips.2022.03.014

115

Wang X. Cirit M. Wishnok J. S. Griffith L. G. Tannenbaum S. R. (2019). Analysis of an integrated human multiorgan microphysiological system for combined tolcapone metabolism and brain metabolomics. Anal. Chem.91, 8667–8675. 10.1021/acs.analchem.9b02224

116

Wang K. Ma F. Arai S. Wang Y. Varkaris A. Poluben L. et al (2023). WNT5a signaling through ROR2 activates the hippo pathway to suppress YAP1 activity and tumor growth. Cancer Res.83, 1016–1030. 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-22-3003

117

Wedeken L. Luo A. Tremblay J. R. Rawson J. Jin L. Gao D. et al (2017). Adult murine pancreatic progenitors require epidermal growth factor and nicotinamide for self-renewal and differentiation in a Serum- and conditioned medium-free culture. Stem Cells Dev.26, 599–607. 10.1089/scd.2016.0328

118

Wei S. Wang Q. (2018). Molecular regulation of nodal signaling during mesendoderm formation. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. (Shanghai)50, 74–81. 10.1093/abbs/gmx128

119

Wells J. M. Esni F. Boivin G. P. Aronow B. J. Stuart W. Combs C. et al (2007). Wnt/beta-catenin signaling is required for development of the exocrine pancreas. BMC Dev. Biol.7, 4. 10.1186/1471-213x-7-4

120

Wiedenmann S. Breunig M. Merkle J. von Toerne C. Georgiev T. Moussus M. et al (2021). Single-cell-resolved differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells into pancreatic duct-like organoids on a microwell chip. Nat. Biomed. Eng.5, 897–913. 10.1038/s41551-021-00757-2

121

Wong C. W. Han H. W. Tien Y. W. Hsu S. H. (2019). Biomaterial substrate-derived compact cellular spheroids mimicking the behavior of pancreatic cancer and microenvironment. Biomaterials213, 119202. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.05.013

122

Wu Y. Aegerter P. Nipper M. Ramjit L. Liu J. Wang P. (2021). Hippo signaling pathway in pancreas development. Front. Cell Dev. Biol.9, 663906. 10.3389/fcell.2021.663906

123

Wu Y. H. Hung Y. P. Chiu N. C. Lee R. C. Li C. P. Chao Y. et al (2022). Correlation between drug sensitivity profiles of circulating tumour cell-derived organoids and clinical treatment response in patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Eur. J. Cancer166, 208–218. 10.1016/j.ejca.2022.01.030

124

Xiang D. He A. Zhou R. Wang Y. Xiao X. Gong T. et al (2024). Building consensus on the application of organoid-based drug sensitivity testing in cancer precision medicine and drug development. Theranostics14, 3300–3316. 10.7150/thno.96027

125

Xu X. D'Hoker J. Stangé G. Bonné S. De Leu N. Xiao X. et al (2008). Beta cells can be generated from endogenous progenitors in injured adult mouse pancreas. Cell132, 197–207. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.015

126

Yan K. S. Janda C. Y. Chang J. Zheng G. X. Y. Larkin K. A. Luca V. C. et al (2017). Non-equivalence of Wnt and R-spondin ligands during Lgr5(+) intestinal stem-cell self-renewal. Nature545, 238–242. 10.1038/nature22313

127

Yan H. H. N. Chan A. S. Lai F. P. Leung S. Y. (2023). Organoid cultures for cancer modeling. Cell Stem Cell30, 917–937. 10.1016/j.stem.2023.05.012

128

Yu J. Liu D. Sun X. Yang K. Yao J. Cheng C. et al (2019). CDX2 inhibits the proliferation and tumor formation of colon cancer cells by suppressing Wnt/β-catenin signaling via transactivation of GSK-3β and Axin2 expression. Cell Death Dis.10, 26. 10.1038/s41419-018-1263-9

129

Zhou Z. Van der Jeught K. Li Y. Sharma S. Yu T. Moulana I. et al (2023). A T cell-engaging tumor organoid platform for pancreatic cancer immunotherapy. Adv. Sci. (Weinh)10, e2300548. 10.1002/advs.202300548

130

Zuiani J. Perkins G. Wu D. Drogemuller C. Coates T. (2024). 265.8: characterising pancreatic organoids from hereditary pancreatitis patients and their viability as a disease model. 108. 10.1097/01.tp.0001065112.54802.ba

Summary

Keywords

drugscreening, pancreatic cancer, pancreatic exocrine organoids, precision medicine, spheroids

Citation

Tan X, Huang B, Yang X, Wang P and Hu L (2026) Construction and application of pancreatic exocrine organoid and spheroid for drug screening and precision medicine. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 13:1746622. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2025.1746622

Received

14 November 2025

Revised

07 December 2025

Accepted

11 December 2025

Published

06 January 2026