Abstract

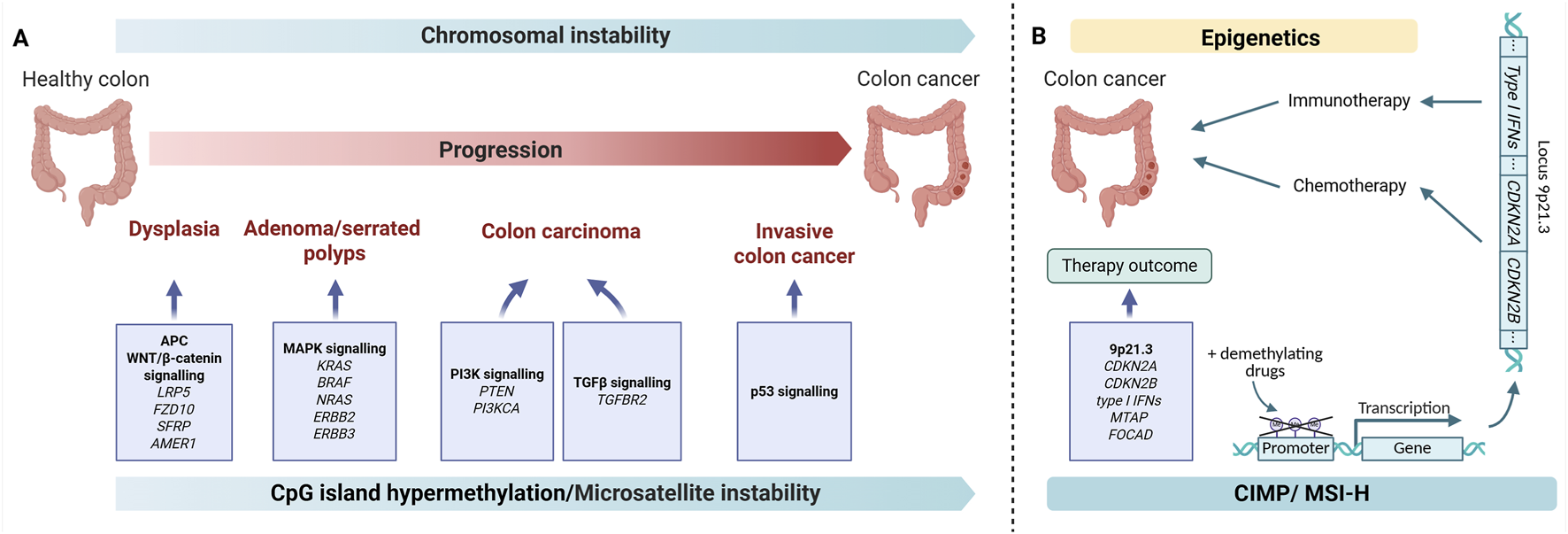

Colorectal cancer (CRC) progression is influenced by genetic and epigenetic aberrations. Oncogenesis of CRC involves the accumulation of mutations in proteins involved in the regulation of cell proliferation, growth and death (Graphical abstract A). DNA methylation has been demonstrated to contribute to tumor initiation, progression, and modulation of therapeutic responses. In this particular landscape, the 9p21.3 locus has been observed to integrate various cellular processes, including cell cycle control (CDKN2A/CDKN2B and ANRIL), immune signaling (cluster of type I interferons), and metabolic regulation (MTAP, MLLT3). This creates relationships that may affect tumor intrinsic and extrinsic features, immunogenicity, and therapeutic sensitivity. The objective of our analysis is to provide a comprehensive overview of the role of the 9p21.3 locus in CRC, focusing on its potential implications for treatment decisions and prediction of treatment responses. Analyzing the 9p21.3 status would help stratify CRC patients into different groups and guide the choice of personalized therapy for CRC. It could also enhance current CRC treatment by pretreating patients with demethylating agents and using an immunotherapeutic approach in combination with senolytic drugs (Graphical abstract B).

Graphical Abstract

Graphical abstract. (A) Stages of CRC oncogenesis. The gradual accumulation of mutations in intestinal cells leads to disruptions in signaling pathways (WNT, MAPK, PI3K, TGFb, p53) and leads to malignancy (B) Epigenetic changes in the 9p21.3 locus can impact the outcome of CRC therapy. Demethylating may restore gene expression at the 9p21.3 locus and enhance the effects of chemotherapy and immunotherapy. Illustration created with BioRender.com.

1 Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) remains a major global health burden, ranking third in incidence and second in mortality, with >1.9 million new cases and ∼904,000 deaths estimated in 2022 (Bray et al., 2024). Beyond classical genetic drivers, CRC is profoundly shaped by epigenetic dysregulation, particularly DNA methylation, which contributes to tumor initiation, progression, and therapeutic response (Hinoue et al., 2012; Rawson and Bapat, 2012; Vedeld et al., 2018). The CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP) delineates a distinct molecular class characterized by widespread promoter hypermethylation; CIMP-high tumors overlap with MSI-H disease. MSI-H refers to tumors with instability in ≥30% of tested microsatellites. These categories are not fully congruent, underscoring the need for integrated molecular stratification (Weisenberger et al., 2006; Hinoue et al., 2012).

CIMP exhibits significant molecular heterogeneity beyond the traditional binary classification (Weisenberger et al., 2006). Large-scale studies have identified CIMP-high (CIMP-H) and CIMP-low subtypes with distinct biological behaviors. CIMP-H tumors (≥3 of 5 methylated markers in the Weisenberger panel) show concordant methylation patterns across tumor regions with >95% intratumoral consistency, indicating clonal epigenetic alterations. However, individual marker variability occurs in approximately one-third of CIMP-positive cases, suggesting complex methylation dynamics (Nosho et al., 2008; Flatin et al., 2021).

There are well-established epigenetic biomarkers of colorectal cancer, like MLH1 promoter hypermethylation that leads to mismatch repair (MMR) deficiency and MSI (Nguyen et al., 2020; Joo et al., 2023), SEPT9 methylation that leads to enhanced cell proliferation and migration, etc. In our review we decided to focus on the 9p21.3 locus (Leerhoff et al., 2023; Cao et al., 2024).

The 9p21.3 locus is of special interest. This ∼0.5-Mb region encompasses CDKN2A/CDKN2B (encoding p16INK4a/p14ARF and p15INK4b), the lncRNA ANRIL, and MTAP, and lies adjacent to a dense type I interferon gene cluster–elements with direct relevance to cell-cycle control, cellular senescence, tumor immunogenicity, and response to therapy (Hinoue et al., 2012; Barriga et al., 2022; Morgan et al., 2023). Epigenetic silencing of CDKN2A/CDKN2B gene cluster constrains antitumor checkpoints, whereas deletions at 9p21.3 can remove interferon genes, promoting an immune-cold microenvironment and resistance to immune-checkpoint blockade (Morgan et al., 2023). Collectively, findings from loss-of-function deletion studies of 9p21.3 support a therapeutic strategy in which DNA-demethylating agents are used to re-activate epigenetically silenced tumor-suppressor and type I interferon pathways–provided the locus remains structurally intact without large-scale genomic deletions that would eliminate the DNA methyltransferase inhibitor target sequences (Chiappinelli et al., 2015; Roulois et al., 2015; Topper et al., 2020; Barriga et al., 2022).

Previous studies have focused on the role of 9p21.3 aberrations in other cancer types. Here, we describe recent evidence of the important role of 9p21.3 epigenetic changes in colorectal cancer (CRC). CRC is also characterized by the methylation of regions of the genome other than 9p21.3 that play an important role in CRC pathogenesis and are responsible for specific CRC subtypes, such as CIMP. The genes affected by CIMP and their roles in CRC are described in detail in other papers, and we briefly mention them in the current work, which is devoted to the role of 9p21.3 in CRC. The status of locus 9p21.3 may affect the expression of genes associated with intestinal tumor formation. These genes play an important role in determining tumor cell characteristics, shaping the tumor microenvironment, and influencing the antitumor immune response. Overall, changes in 9p21.3 methylation may have high prognostic value and influence patient stratification alongside other markers in the future. Based on accumulated data, we propose expanding possible therapeutic strategies. Demethylation therapy can restore gene expression at the 9p21.3 locus, potentially enhancing the efficacy of chemotherapeutic and immunotherapeutic drugs in certain patient cohorts (Mansfield et al., 2024; Alum et al., 2025; Kim, 2025; López et al., 2025; Suraweera et al., 2025). The integration of senolytic agents into treatment regimens is a hypothetical concept primarily based on preclinical data and requires thorough clinical validation with appropriate biomarker stratification before therapeutic implementation. This review summarizes the current evidence on the epigenetics of 9p21.3 in CRC and its impact on treatment outcomes. We also justify clinical strategies that personalize treatment approaches for patients based on genetic and epigenetic data.

2 The role of 9p21.3 genes in the pathogenesis of colorectal cancer

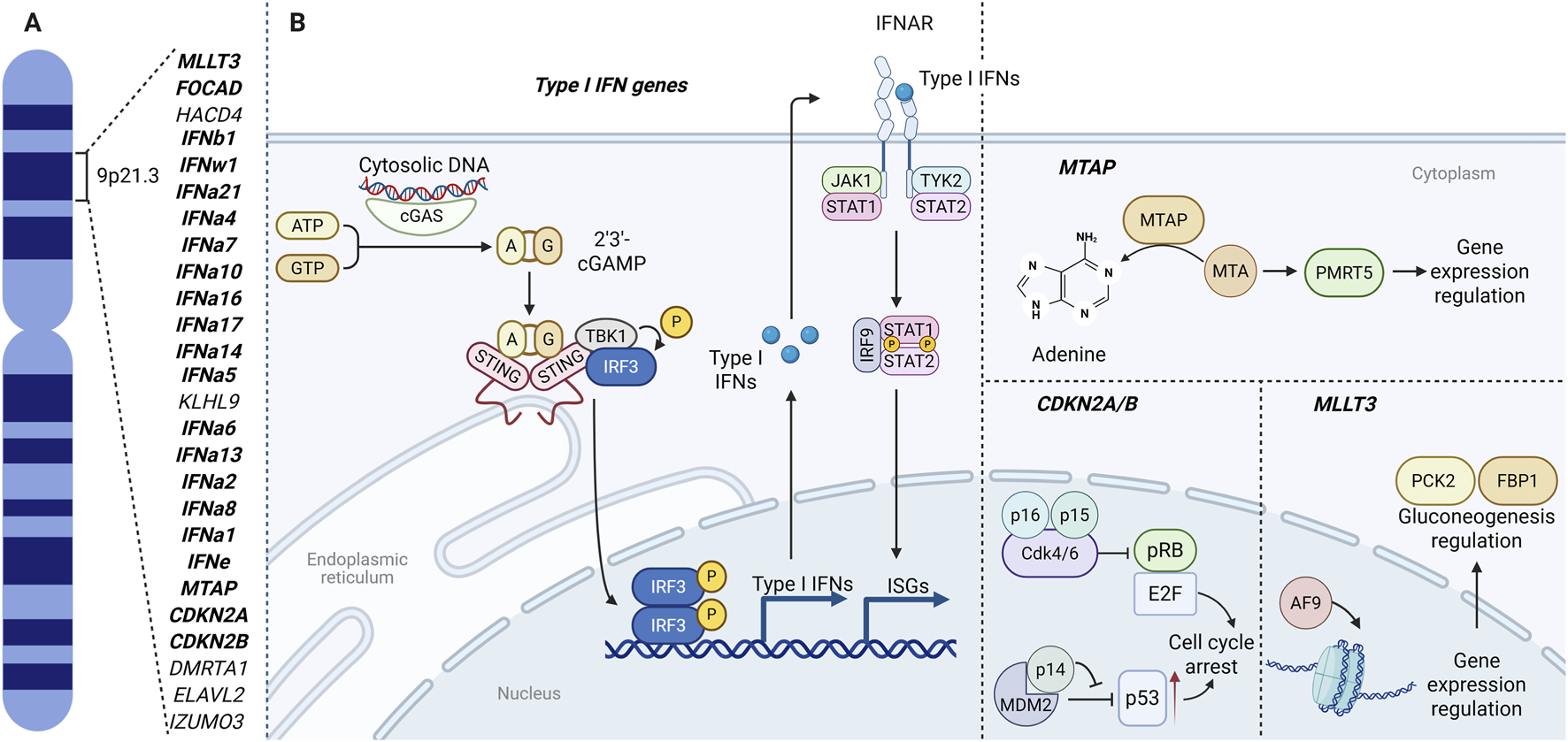

The association between the short arm of chromosome 9 (9p) and cancer was recognized more than 3 decades ago (Hayashi et al., 1991). More recent work has refined this link and focused attention on the 9p21.3 interval in particular (Han et al., 2021; Barriga et al., 2022). This ∼0.5 Mb region contains a dense cluster of type I interferon (type I IFN) genes (IFN-I gene cluster), several tumor-suppressor genes–including CDKN2A, CDKN2B, CDKN2B-AS1 (ANRIL), MTAP, MLLT3, FOCAD–and other genes with less well-defined roles in oncogenesis, such as ELAVL2, HACD4, KLHL9, DMRTA1, IZUMO3 (Figure 1A) (Spiliopoulou et al., 2022).

FIGURE 1

The 9p21.3 locus: gene map (A) and integrated functional circuits (B) linking cGAS–STING/type I IFN signaling, IFNAR–JAK–STAT transcription, CDKN2A/B (p16INK4a, p14ARF, p15INK4b) cell-cycle control, MTAP–PRMT5 methylation, and MLLT3(AF9)-mediated chromatin–metabolic regulation through PCK2 and FBP1. Illustration created with BioRender.com. Parts of the layout were adapted from BioRender templates (Iwasaki, 2025; Lugano, 2025).

Because homozygous deletions at 9p21.3 rank among the most frequent somatic copy-number alterations across human cancers (Cox et al., 2005; Li W.-Q. et al., 2014), much of the historical emphasis has been on loss-of-function via deletion. In CRC, however, 9p21.3 dysfunction is not limited to structural loss: epigenetic silencing can downregulate locus genes and partially phenocopy deletion with distinct implications for prognosis and treatment.

Systematically defining the roles of 9p21.3 genes in CRC pathogenesis will enable stratification by locus epigenetic status and prescribe the use of demethylating strategies to reactivate gene expression. In the following chapters we will focus primarily on the gene-by-gene functions of 9p21.3 in CRC and other malignancies to highlight additional mechanisms that could affect CRC.

2.1 CDKN2A and CDKN2B genes

The CDKN2A gene encodes two proteins: p16INK4a and an alternative reading frame gene product p14ARF (Cilluffo et al., 2020). These proteins are tumor suppressors that regulate the cell cycle. The CDKN2B gene is another gene that encodes tumor suppressor–p15INK4b (Gil and Peters, 2006). CDKN2A and CDKN2B genes are located in the INK4/ARF locus (Kim and Sharpless, 2006; Farooq and Notani, 2022; 2022).

p16INK4a and p15INK4b are inhibitors of cyclin-dependent kinase CDK4/6. Both p16INK4a and p15INK4b prevent the phosphorylation of the retinoblastoma protein (RB). The stable non-phosphorylated form of RB binds to the transcription factor E2F, to suppress the expression of cell-cycle-related genes. E2F inactivation leads to an arrest in the cell’s transition from G1 phase to S phase (Figure 1B) (Zhao et al., 2016).

p14ARF is one of the proteins that regulates another tumor suppressor–p53. Normally, p53 is rapidly ubiquitinated by MDM2 and degraded by proteasomes, but when MDM2 binds to p14ARF, p53 is no longer degraded. This can lead both to cell cycle arrest and apoptosis (Figure 1B) (Ozenne et al., 2010; Zhou et al., 2023).

p16INK4a, p14ARF and p15INK4b can stop the cell cycle in response to stress insults, giving cell time for restoration. Also, p16INK4a has been reported to enhance cell viability and migration in CRC by inhibiting cuproptosis, a type of cell death caused by excess copper accumulation (Cheng et al., 2024).

Deletion and promoter hypermethylation of CDKN2A and CDKN2B are common in various cancers, in CRC in particular (Zhao et al., 2016). CDKN2A hypermethylation is the most studied epigenetic marker in the context of CRC compared to other genes of the 9p21.3 locus. It is reported that CDKN2A promoter hypermethylation in CRC is observed in 30% of CRC patients, and loss of expression in 25% of all cases (Shima et al., 2011). The methylation rate of CDKN2A is comparable to methylation rate of recognized markers such as MLH1, the gene encoding the DNA mismatch repair protein. MLH1 is methylated in 20%–25% of colorectal cancer cases (Moreno-Ortiz et al., 2021; Rico-Méndez et al., 2025). Despite the high specificity of CDKN2A methylation as a marker of CRC (96%–100%) (Fatemi et al., 2022), its sensitivity is lower than that of other diagnostic markers of CRC, such as SEPT9 or SFRP2 (Fatemi et al., 2022; Oh and Cho, 2024). That makes CDKN2A methylation more suitable for confirming diagnosis rather than primary screening. CDKN2A promoter hypermethylation in CRC patients has been shown to be associated with invasion, metastasis, and overall worse prognosis (Xing et al., 2013).

In CRC, CDKN2B is frequently inactivated by promoter hypermethylation (e.g., 26% in a Japanese cohort with concordant mRNA reduction and adverse features) and, less commonly, by 9p21.3 deletions. Reported methylation frequencies vary widely across populations and can be as high as 68% in some Chinese cohorts (Xu et al., 2004; Ishiguro et al., 2006; Nieminen et al., 2012).

Dysfunction of CDKN2A/B can lead to uncontrolled tumor cell growth and poor prognosis. Li Yang et al. showed that hypermethylation of the CDKN2A promoter in a mouse model of CRC leads to remodeling of the tumor microenvironment through increased PD-L1 expression and poorer prognosis (Yang et al., 2023). Overall, mutations in CDKN2A may contribute to poor prognosis in a variety of cancer types (Debniak et al., 2005; Yang et al., 2016; Horn et al., 2021; Li C. et al., 2022).

When CDKN2A dysfunction in CRC is caused by hypermethylation, restoration of normal expression by demethylating agents may be used as anti-cancer drugs. Moreover, they may be more effective when used in combination with anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy, as immunotherapy is less effective in the presence of CDKN2A epimutation (Yang et al., 2023).

Although low expression or loss of CDKN2A/B is a marker of poor prognosis in CRC, overexpression also has negative consequences. It has been shown that CDKN2A can promote invasion and metastasis through the regulation of E-cadherin, N-cadherin and vimentin expression (Shi et al., 2022). Thus, aberrant CDKN2A/B expression, whether consistently reduced or enhanced, can lead to adverse consequences. On the other hand, it has been demonstrated that high CDKN2A expression correlates with high response to immunotherapy (Dong et al., 2023).

In addition to the classical functions of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors in tumors described above, they can influence the formation of certain structures in the tumor. Jie Fan et al. demonstrated the role of CDKN2A in the formation of “neutrophil-in-tumor” (hNiT) structures in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. The formation of hNiT is associated with an unfavorable prognosis. It was shown that p16INK4a expression in HPV-associated oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma correlated with decreased hNiT formation and a more favorable prognosis (Fan et al., 2022).

A transient, therapeutically induced increase in cell-cycle inhibitor expression may confer clinical benefits. In contrast, sustained overexpression can be harmful. Therefore, treatment should be time-limited and targeted only at CDKN2A/B-negative tumor cells.

2.2 Type I IFN genes

Next to CDKN2A and CDKN2B genes, type I IFN gene cluster is located at the locus 9p21.3. It includes 13 subtypes of IFNα, IFNβ1, IFNε and IFNω1 genes (UCSC Genome Browser, 2025).

Type I IFNs are mostly in charge of response against viral infections. When a cell encounters a virus, viral nucleic acids are recognized with a pattern recognition receptor (PRR). The recognition triggers various signaling cascades that lead to the synthesis of type I IFNs (Swiecki and Colonna, 2011; McNab et al., 2015; Mödl et al., 2023).

Type I IFNs bind to the IFNAR receptor, leading to the activation of the JAK1 and TYK2 kinases. These kinases phosphorylate the transcription factors STAT1 and STAT2 which dimerize and translocate from the cytoplasm to the nucleus. There, they bind to IRF9 to form a complex that triggers the expression of ISGs–interferon-stimulated genes (Figure 1B). Signal transmission can also be carried out through other STATs (Ivashkiv and Donlin, 2014; McNab et al., 2015; Mödl et al., 2023).

The key signaling pathway associated with the expression of type I IFNs is the cGAS-STING pathway. This mechanism is responsible for the recognition of double-stranded viral and bacterial DNA and, most importantly in the context of this review, DNA of damaged cells in the cytoplasm. The initiator enzyme is cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (hereinafter cGAS). It detects foreign and unnaturally located DNA in the cytoplasm, dimerizes and triggers the formation of cGAMP. cGAMP binds to STING, an adapter protein located on the ER. Interaction with cGAMP causes conformational changes in STING and leads to the formation of a STING complex with TBK1, NIK and IKK kinases. This complex triggers a number of phosphorylation reactions and, among other things, leads to the expression of type I IFNs, particularly IFNβ (Figure 1B) (Corrales et al., 2016; Galluzzi et al., 2018; Chin et al., 2023; Luo et al., 2024). Moreover, tumor cells can secrete cGAMP externally, triggering an interferon response in cells of the tumor microenvironment (Samson and Ablasser, 2022). It is also assumed that DNA from destroyed tumor cells can trigger the cGAS-STING pathway in immune cells, particularly phagocytes (Samson and Ablasser, 2022).

The role of the cGAS-STING pathway and type I IFNs in tumors is controversial. On one hand, due to the increased production of type I IFNs by tumor cells, immune cells are activated: dendritic cells, NK cells, T cells (Mender et al., 2020; Samson and Ablasser, 2022). Additionally, type I IFNs inhibit MDSCs (Mödl et al., 2023). This provides a comprehensive antitumor response. Type I IFNs can also induce apoptosis in cancer cells, including CRC (Zhou et al., 2020; Musella et al., 2021; Mödl et al., 2023). It is reported that type I IFNs can contribute to cell cycle arrest through induction of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors p15INK4b, p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 (Musella et al., 2021; Mödl et al., 2023). Type I IFNs can also act as negative regulators of VEGF signaling, preventing angiogenesis. In particular, it was shown that IFNα can lower vascularization level of the CRC liver metastases (Mödl et al., 2023). However, it has been reported that at later stages of tumor development, type I IFNs may, on the contrary, have a pro-tumor effect by increasing the production of immunosuppressive molecules such as PD-L1, IDO, and IL-10 (Zhou et al., 2020). In CRC, decreased IFNAR expression and impaired interferon signaling may be observed, which may lead to altered cancer-associated fibroblast (CAF) function and tumor matrix remodeling (Sun et al., 2025). Type I IFNs play a crucial role in tumor control by promoting dendritic cell maturation and enhancing antigen cross-priming to activate T cells (Su et al., 2019). Cancer cell intrinsic type I IFNs signaling modulates therapeutic responses, influencing outcomes to chemotherapy (Sistigu et al., 2014), radiotherapy (Deng et al., 2014), and immunotherapy (Su et al., 2019).

2.3 MTAP gene

MTAP encodes methylthioadenosine phosphorylase, a crucial enzyme in purine and methionine metabolism. MTAP converts MTA (5′-methylthioadenosine), which is formed during methionine metabolism, into adenine, thereby regulating its intracellular levels. If MTAP is not functioning, MTA accumulates. It was demonstrated in glioblastoma cell line models that the accumulation of MTA may result in suppression of T-cell activity, decreased response to interferons and instructing the tumor microenvironment and macrophage polarization toward M2 (Han et al., 2021). MTA inhibits the PRMT5 (protein arginine methyltransferase 5), a methyltransferase responsible for epigenetic regulation on the histone methylation level, methylation of transcription factors, etc. (Figure 1B) (Patro et al., 2022; Bedard et al., 2023; Ngoi et al., 2024).

In fact, MTAP deletion or inactivation is a vulnerability for tumor cells because MTA accumulation combined with using PRMT5 inhibitors will lead to selective destruction of cancer cells without MTAP. However, there are several problems with using the described mechanism in therapy. Firstly, it is reported that cancer cells (e.g., glioblastoma) can lower the level of MTA by eliminating it from the cell (Barekatain et al., 2021). The second issue is the rare occurrence of MTAP loss in CRC. MTAP loss is widespread in gastrointestinal cancers, but it is more common for upper gastrointestinal cancers. MTAP is often deleted together with CDKN2A/B due to their neighboring localization within locus 9p21.3. (Bedard et al., 2023; Mauri et al., 2024). Despite the rarity of deletion in CRC, MTAP could be found mutated in this type of cancer. It is assumed that the loss of MTAP does not have a significant impact on the patient’s prognosis (Mauri et al., 2024).

2.4 MLLT3 gene

The MLLT3 gene encodes protein AF9 sharing the YEATS domain with other proteins of the YEATS family. YEATS domain can bind to acetylated and crotonylated lysines, due to which AF9 acts as a chromatin reader and is involved in the regulation of transcription (Li Y. et al., 2014; 2016; He et al., 2023).

Xuefeng He et al. (He et al., 2023) showed that AF9 plays an important role in the epigenetic regulation of genes coding gluconeogenesis enzymes PCK2 and FBP1 (Figure 1B). PCK2 is a mitochondrial isoform of PEPCK–phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase. It can help in tumor progression providing metabolic plasticity in conditions of glucose deficiency (Grasmann et al., 2019). On the other hand, FBP1 (fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase 1) acts as a tumor suppressor. It is reported that FBP1 can inhibit glycolysis (Grasmann et al., 2019).

The predominant metabolic process in CRC is glycolysis (Graziano et al., 2017; Lu et al., 2021), while gluconeogenesis is found to be less active (Grasmann et al., 2019; Wang and Dong, 2019). According to Xuefeng He et al., a decrease in AF9 expression led to a decrease in PCK2 and FBP1 expression, and consequently, a decrease in gluconeogenesis. Thus, metabolic reprogramming in CRC may be associated with AF9 expression and activity. Currently there is no clear data demonstrating common mutations or epimutations associated with the MLLT3 gene in CRC. It is shown that as CRC progresses, AF9 expression decreases, with the risk of relapse increasing in patients with lower AF9 levels (He et al., 2023).

2.5 FOCAD gene

Another gene of the 9p21.3 locus, FOCAD, encodes the focal adhesion protein (focadhesin), which is involved in cell adhesion and regulation of the cell cycle, and also acts as a tumor suppressor (Brand et al., 2020; Harmonizome 3.0: FOCAD, 2025). The role of focadhesin in tumors was demonstrated using gliomas as a model. Focadhesin can bind to tubulin and reduce the rate of microtubule assembly, which reduces tumor cell migration (Brand et al., 2020). Moreover, focadhesin was shown to accumulate in the G2/M phase and slow it down, which may explain its relationship with cell cycle regulation (Brand et al., 2020).

In a non-small-cell lung cancer model, it was shown that a signaling pathway involving focadhesin can increase the sensitivity of cells to ferroptosis (Liu et al., 2020).

The FOCAD gene is expressed in the proliferating epithelial cells of the colonic crypts. Several studies have shown that FOCAD deletions are associated with polyposis and the development of CRC (Weren et al., 2015; Belhadj et al., 2020). On the contrary, some point mutations do not initiate oncogenesis, unlike deletions of the gene regions and some missense mutations found in patients with CRC (Belhadj et al., 2020). Further studies are needed to determine the specific role of FOCAD in the development of polyposis and CRC.

2.6 Clinical context and biomarker applications

The genetic and epigenetic aberrations, as well as the role of genes located on 9p21.3 in tumorigenesis, render this chromosomal region an intriguing therapeutic target in the context of CRC. The clinical significance of this phenomenon is particularly pronounced in MSI-H CRC, where the intersection of DNA methylation patterns with immune phenotypes creates opportunities for highly effective targeted therapeutic intervention.

CDKN2A/B hypermethylation demonstrates differential prevalence between molecular subtypes of CRC, with CDKN2A promoter hypermethylation detected in approximately 30% of CRC cases overall using validated MethyLight methodology (Shima et al., 2011). This hypermethylation occurs as part of the broader epigenetic dysregulation characteristic of the CIMP, which shows strong association with MSI-H status (Kim et al., 2024).

CDKN2A methylation status correlates independently with CIMP classification, with hypermethylated tumors exhibiting significantly increased odds of CIMP-high status (Shima et al., 2011), showing an OR of 39.6 (95% CI, 20.6–76.1) for CIMP-high compared to CIMP-0, and an OR of 5.30 (95% CI, 3.52–8.00) for CIMP-low compared to CIMP-0 (Shima et al., 2011). This relationship establishes 9p21.3 methylation as both a component and potential surrogate marker of epigenetic dysregulation patterns that influence therapeutic responsiveness.

While CDKN2A promoter methylation occurs in approximately 30% of CRC cases, direct comparison with established biomarkers reveals both complementary and distinct clinical utilities (Shima et al., 2011; Rico-Méndez et al., 2025). MLH1 promoter hypermethylation, detected in 20%–25% of sporadic CRCs, represents the predominant mechanism underlying MSI-H phenotype in the absence of germline mutations. A recent systematic analysis of 138 CRC tumors demonstrated that MLH1 methylation (21% partial, 3.6% complete) showed significant concordance with MSI-H status (p < 0.01) when assessed across five distinct CpG island regions. In contrast, CDKN2A methylation exhibits broader distribution across molecular subtypes, occurring in both MSI-H (23%) and microsatellite stable/low (MSS/MSI-L, 13.4%) tumors, positioning it as a CIMP-associated rather than MSI-specific marker (Kim et al., 2024). The prevalence of CDKN2A promoter methylation in CRC is approximately 30%, and as a standalone marker its diagnostic utility remains lower than that of blood-based methylated SEPT9 assays (pooled sensitivity ≈69–71% and specificity ≈91–92% in meta-analyses) or combined multi-gene methylation panels, while CDKN2A methylation shows high specificity around 98% (Shima et al., 2011; Nian et al., 2017; Karam et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2019; Hariharan and Jenkins, 2020). Notably, MLH1 promoter methylation has dual diagnostic and therapeutically relevant roles: it supports identification of sporadic MSI-H colorectal cancers, a subgroup that is generally responsive to PD-1–based immune checkpoint inhibition, while also distinguishing these cases from Lynch syndrome for whom germline testing is indicated within standardized diagnostic pathways (McRonald et al., 2024; Eslinger et al., 2025; Rico-Méndez et al., 2025). Recent population-level data from England show that only 44% of colorectal cancers undergo dMMR screening, with approximately four-fold geographic variation, underscoring implementation gaps even for this established biomarker. These observations support using CDKN2A methylation analysis as complementary–rather than a replacement–to MLH1 testing, particularly for stratifying CIMP-high subsets in which CDKN2A and MLH1 promoter methylation are components of validated CIMP panels and are associated with distinct immune phenotypes (e.g., higher CD8+ TIL densities and PD-L1 expression in CIMP-high MSI-H tumors) (Ogino et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2024).

The clinical context for 9p21.3-targeted interventions builds upon well-established immunotherapy efficacy in MSI-H CRC. Recent Phase III data demonstrate superior efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibition in this molecular subtype. The KEYNOTE-177 trial established pembrolizumab as first-line standard of care, showing superior progression-free survival compared to chemotherapy (median 16.5 versus 8.2 months; HR 0.60; 95% CI 0.45–0.80; P = 0.0004) (Casak et al., 2021), leading to FDA approval on 29 June 2020. The CheckMate 8HW trial provided definitive evidence for nivolumab plus ipilimumab as an alternative first-line option (Andre et al., 2024), demonstrating 79% reduction in progression risk compared to chemotherapy (HR 0.21; 97.91% CI 0.13–0.35; P < 0.0001) (Lenz et al., 2024). Recent comprehensive meta-analyses have confirmed the superior efficacy of combination immunotherapy, with nivolumab plus ipilimumab demonstrating significantly improved progression-free survival in MSI-H CRC patients (HR 0.676; 95% CI: 0.583–0.770) at a median follow-up of 31.5 months, with manageable toxicity profiles and high response rates (ORR 63.1%) (Tereda et al., 2025). Network meta-analyses indicate that this combination may represent the most efficacious first-line treatment approach for the MSI-H subgroup, with potential for enhanced outcomes when combined with epigenetic priming strategies (Chen K. et al., 2024).

Nevertheless, therapeutic challenges persist among immunotherapy-responsive MSI-H patients, as a considerable subset experiences primary or early resistance to anti-PD-1 monotherapy. Experts have observed that trial response rates frequently fall below 50%, thereby underscoring biological heterogeneity and the necessity for additional biomarkers beyond tumor mutational load. This clinical reality creates a strong rationale for biomarker-driven stratification and epigenetic-targeted combinations to address immune-evasion mechanisms such as epigenetic silencing of antigen-presentation pathways (Hyung et al., 2022; Sahin et al., 2024).

The translation of 9p21.3 biology into clinical biomarker applications requires practical implementation strategies. CDKN2A methylation analysis can be performed using quantitative pyrosequencing assays that yield single-base-resolution percent methylation values at defined CpG sites and have been validated in large CRC cohorts. Alternative approaches, such as MethyLight-based CIMP panels, offer high-throughput classification of CIMP-high versus CIMP-low/negative tumors and can be readily integrated into diagnostic workflows. Integration with existing molecular classification systems offers additional clinical utility, as the combination of MSI status, CIMP classification, and specific gene methylation patterns provides a framework for patient stratification that builds upon established clinical practice (Ahlquist et al., 2008; Bihl et al., 2012).

The documented correlation between CIMP-high status and enhanced immune infiltration provides mechanistic support for combination strategies targeting both epigenetic silencing and immune checkpoint pathways. In a cohort of 133 MSI-H CRCs, CIMP-high tumors exhibited significantly higher densities of CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes as well as elevated PD-L1 expression (both tumor proportion and combined positive scores) compared to CIMP-low/negative cases, independent of tumor mutational burden, identifying CIMP-high tumors as an immune-“hot” subtype and optimal candidates for immunotherapy combinations. The identification of MSI-H patients with epigenetically “cold” immune phenotypes thus represents a specific population in which the 9p21.3 status should be investigated and epigenetic interventions–such as DNA methyltransferase inhibitors–might restore therapeutic responsiveness to checkpoint inhibition (Kim et al., 2024).

2.7 Molecular landscape of MSI-H colorectal cancer

MSI-H colorectal cancer represents a molecularly distinct subtype characterized by dMMR and the accumulation of mutations at repetitive DNA sequences. Understanding the complete molecular architecture of MSI-H CRC is essential for contextualizing 9p21.3-targeted interventions within the broader therapeutic landscape (Chen et al., 2017; Greco et al., 2023). The MSI-H phenotype arises through two principal mechanisms: sporadic epigenetic silencing (predominantly MLH1 promoter hypermethylation, accounting for a majority of MSI-H cases across cohorts) and germline mutations in MMR genes (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2) causing Lynch syndrome. MLH1 hypermethylation shows strong association with CIMP-high status and frequently co-occurs with BRAF V600E mutations in sporadic MSI-H tumors, creating a molecular signature distinct from Lynch syndrome-associated cancers. Recent clinical evidence indicates differential immunotherapy outcomes between Lynch syndrome and non-Lynch MSI-H patients, with Lynch-linked cases showing improved progression-free survival under immune checkpoint blockade while both groups derive benefit overall (Kuismanen et al., 2000; Kedrin and Gala, 2015; Seppälä et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2017; Colle et al., 2023).

Beyond classical MMR proteins, several biomarkers refine MSI-H classification and prognostication (Greco et al., 2023). The HSP110 T17 mononucleotide repeat has been proposed as a functional MSI marker; deletions in this sequence correlate with reduced wild-type HSP110 expression and have been reported to associate with improved prognosis in some studies, although large multicenter data indicate it is not a robust prognostic marker and is better considered as a diagnostic adjunct to resolve discordant cases (Kim and Kang, 2014; Kim et al., 2014; Berardinelli et al., 2018; Tachon et al., 2022). Transcriptomic profiling shows MSI-H tumors are enriched for inflammation-related pathways (IL-17 signaling, TNF signaling, chemokine signaling, NFκB activation) and display alterations in metabolic programs compared with microsatellite-stable counterparts (Kibriya et al., 2024). These pathway features correspond to an immune-inflamed microenvironment characterized by dense CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, elevated PD-L1 expression, and generally high tumor mutational burden (Kim et al., 2024).

Importantly, rare discordant cases exhibit MSI-H by molecular testing despite proficient MMR protein expression, reflecting mechanisms beyond canonical MMR deficiency. Such cases may involve isolated MSH3 dysfunction–particularly affecting tetranucleotide loci–and can be modulated by IL-6 pathway activity, with functional polymorphisms in the IL-6/gp130 axis (e.g., gp130 + 148G/C) associated with specific MSI patterns. Additionally, inflammation-associated microsatellite alterations observed in non–MSI-H tumors represent a distinct phenomenon linked to chronic inflammation rather than MMR deficiency (Koi et al., 2018; Salar et al., 2024; Xu et al., 2024). The integration of 9p21.3 methylation status with established MSI-H biomarkers offers opportunities for refined patient stratification within broader epigenetic frameworks that include locus-specific methylation at tumor suppressor regions such as CDKN2A. In MSI-H cohorts, CIMP-high tumors exhibit significantly higher CD8+ TIL densities and PD-L1 expression than CIMP-low/negative cases, independent of tumor mutational burden, highlighting CIMP-high as an attractive subset for epigenetic–immune combination strategies. This multi-dimensional classification - incorporating MSI status, CIMP classification, BRAF mutation, and locus-specific methylation patterns–provides a practical molecular roadmap for precision medicine approaches in colorectal cancer (Silva et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2017; Greco et al., 2023; Kim et al., 2024).

3 Epigenetic features of 9p21.3 locus and cancer-associated dysregulation

Epigenetic regulation is a multifaceted process that extends beyond DNA methylation to encompass histone modifications, nucleosome positioning, and higher-order chromatin architecture. In this chapter, we analyze regulation of genes within the 9p21.3 locus at both the “2D” level of local promoter-enhancer states and the “3D” level of genome topology, including long-range interactions and domain organization. This integrated perspective clarifies how locus configuration shapes gene expression and may influence therapeutic responsiveness.

3.1 Topological and epigenetic control of gene expression at the 9p21.3 locus

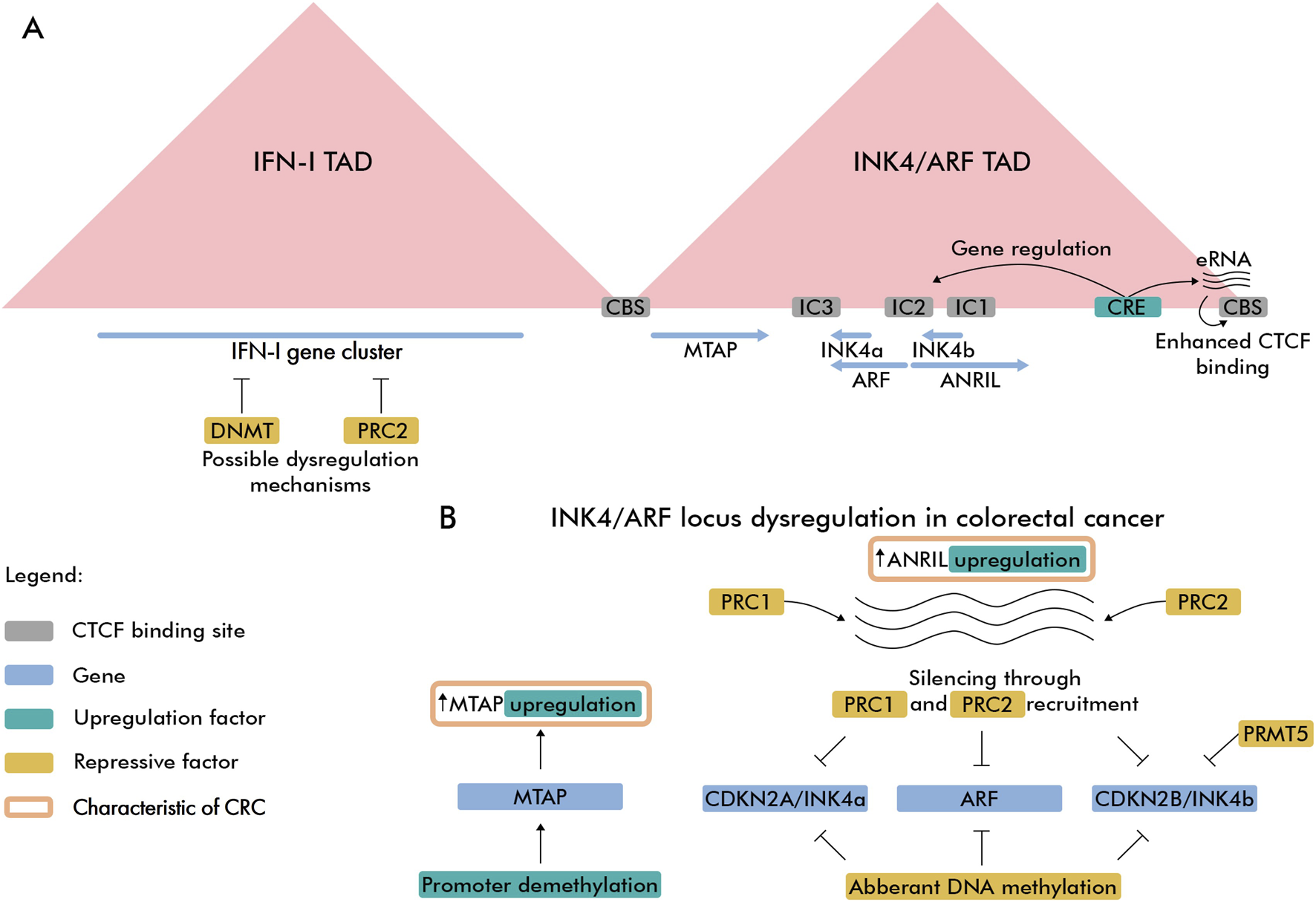

Recent studies revealed that chromatin architecture plays an important role in gene regulation, including 9p21.3 locus. Chromatin in human cells is organized into topologically associating domains (TADs) – submegabase-scale, spatially insulated regions. TAD boundaries are typically demarcated by convergently oriented CTCF binding sites (CBSs) (Szabo et al., 2019; Kabirova et al., 2023). Here, we focus on the chromatin organization of IFN-I and INK4/ARF loci, as more epigenetic data are available for these regions. Hi-C analyses across multiple cell lines demonstrated that IFN-I gene cluster and INK4/ARF region are located in separated domains (Figure 2A) (Rao et al., 2014; Islam et al., 2023). Since domain borders restrict inter-TAD interactions between cis-regulatory elements (CREs) such as promoters and enhancers, this spatial segregation suggests that the IFN-I gene cluster and INK4/ARF region are regulated independently.

FIGURE 2

Spatial and regulatory features of 9p21.3 locus in CRC. (A) Spatial organization of IFN-I and INK4/ARF TADs. The super-enhancer element (CRE) controlling gene and boundary eRNA expression is highlighted with emerald color. Intergenic CTCF-enriched sites are marked as IC1, IC2 and IC3 (Hirosue et al., 2012). (B) CRC-related epigenetic dysregulation features of INK4/ARF locus.

The INK4/ARF TAD includes the CDKN2A, ARF, CDKN2B, and CDKN2B-AS1 genes, along with the MTAP gene located near the 5′ domain boundary. Like most TAD boundaries in human cells, INK4/ARF TAD borders are enriched with CTCF binding sites, indicating that CTCF/cohesin-mediated loop extrusion mechanism contributes to formation of this domain. Notably, the 3′TAD boundary contains actively transcribed enhancers that presumably recruit more CTCF proteins to its binding sites and these enhancers have a modest effect on expression of genes within the domain (Islam et al., 2023). TAD also harbors a super-enhancer region located downstream of ANRIL lncRNA gene enriched with active H3K27ac marks. This super-enhancer controls expression of all genes within the domain while simultaneously driving enhancer RNA (eRNA) expression in 3′ boundary CBS. Expression of eRNA can increase chromatin accessibility, thereby facilitating cohesin loading (Li et al., 2023), which reinforces the domain boundary through cohesin/CTCF-dependent loop extrusion. With regard to CTCF, it remains unclear how eRNA expression affects CTCF binding–whether by opening chromatin, directly recruiting CTCF, or both–as recent studies have cast doubt on the RNA-binding capacity of certain chromatin-associated proteins, including CTCF (Guo et al., 2024; Healy et al., 2024). Another cis-regulatory element was identified in a region adjacent to ARF promoter, which was shown to repress CDKN2A expression through looping interaction (Zhang et al., 2019). 3C-experiments revealed that in normal somatic cells, the CDKN2A/ARF/CDKN2B gene cluster adopts a repressive loop conformation (Hirosue et al., 2012), consistent with these genes’ relatively low expression levels in normal cells (Sano et al., 1998). In senescent cells, the loop conformation becomes more relaxed, leading to elevated expression of CDKN2A and CDKN2B genes and a modest increase in ARF expression. These chromatin loop changes reflect differential CTCF binding, which increases in compact conformations and decreases in relaxed states.

In CRC, DNA hypermethylation of the CDKN2A promoter correlates with reduced gene expression. This CpG island is an established epigenetic target in CRC, showing up to 20% higher methylation in tumor cells compared to normal colorectal mucosa cells. Particularly, hypermethylation occurs more frequently in MSI-H tumors (23%) than in MSS/MSI-L subtypes (13.4%) (Bihl et al., 2012). Beyond silencing via hypermethylation, CDKN2A promoter methylation may displace CTCF from its adjacent binding site, potentially enabling heterochromatin spread (Witcher and Emerson, 2009) and loss of loop-mediated interaction with CREs. The ARF gene is frequently downregulated in CRC, with promoter methylation (observed in 29%–33% of patients) correlating with poor prognosis (Dominguez et al., 2003; Nilsson et al., 2012). Notably, in colon carcinoma ARF promoter methylation often occurs independently of CDKN2A. In 52% of cases ARF was methylated while CDKN2A remained unmethylated, suggesting distinct regulatory mechanisms (Esteller et al., 2000). CDKN2B is also a frequent target for DNA hypermethylation in CRC. In 89% of cases in Egyptian patients, downregulation of CDKN2B was associated with its promoter hypermethylation (Abdel-Rahman et al., 2014). Moreover, CDKN2B was identified as a target of EZH2 histone methyltransferase activity in CRC (Yang et al., 2021). EZH2 was also shown to associate with PRMT5 arginine methyltransferase, resulting in the deposition of repressive histone marks at the CDKN2B promoter–H3K27me3 (PRC2) and H4R3me2s/H3R8me2s (PRMT5). Importantly, treatment with EZH2 and PRMT5 inhibitors activated CDKN2B transcription and attenuated CRC cell growth, demonstrating potential therapeutic relevance.

ANRIL (Antisense Noncoding RNA in the INK4 Locus, CDKN2B-AS1) is a long noncoding RNA transcribed from the bidirectional promoter it shares with the ARF gene. The CDKN2B-AS1 gene spans the entire CDKN2B gene and is transcribed in the antisense direction. This lncRNA is suspected to recruit PRC1 and PRC2 repressive protein complexes, leading to accumulation of H3K27me3 mark and silencing of adjacent genes (Yap et al., 2010). In colon carcinomas, ANRIL overexpression was observed in invasive tumors (12%) and was higher in carcinomas at metastatic stage (16%) (Drak Alsibai et al., 2019). ANRIL epigenetically regulates the INK4/ARF locus by recruiting Polycomb complexes: it binds PRC1/CBX7 and PRC2 components to deposit repressive H3K27me3 and silence CDKN2A/CDKN2B, thereby constraining p16INK4a/p14ARF/p15INK4b expression and senescence checkpoints (Yap et al., 2010; Kotake et al., 2011). During oncogene-induced senescence, circular ANRIL isoforms can switch roles and facilitate INK4 activation by sequestering Polycomb factors, highlighting isoform- and context-specific epigenetic control at 9p21.3 (Muniz et al., 2020).

Collectively, tumor suppressor genes in the 9p21.3 locus exhibit diverse expression regulation mechanisms in CRC, including DNA methylation, Polycomb-mediated suppression, and ANRIL-dependent silencing (Figure 2B). Interestingly, the MTAP gene is frequently overexpressed in CRC due to promoter hypomethylation (Dou et al., 2009; Zhong et al., 2018), in contrast to hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes at the 9p21.3 locus.

Type I IFNs are known to modulate chromatin architecture and accessibility at target loci (Platanitis et al., 2022), yet the 3D organization of the IFN-I gene cluster remains to be defined. Hi-C analyses confirm strong insulation of both INK4/ARF and IFNs TADs across cell types, though HUVEC cells exhibit unique long-range contacts between the IFNA21 downstream region and an ANRIL downstream enhancer (Harismendy et al., 2011). While IFN-I cluster regulation in CRC requires further study, these genes are subject to PRC2-mediated silencing in breast cancer–a phenomenon correlated with diminished antitumor immune responses (Hong et al., 2022). Additionally, single CpG methylation has been reported to silence type I IFNs expression, potentially through an indirect mechanism that disrupts IRF3 binding to promoter regions. Targeted demethylation of the Ifnβ1 promoter in mice increased its expression, demonstrating DNA methylation’s role in regulating Ifnβ1 transcription (Gao et al., 2021). Thus, type I IFNs expression is regulated by both PRC2-mediated silencing and DNA methylation, making these mechanisms potential therapeutic targets. Interferon signaling activity also depends on epigenetic modifications of RNA, in particular m5C. One of the RNA methyltransferases that provides m5C modification is NSUN2, which is highly expressed in CRC tumors. NSUN2 maintains m5C modifications, which in particular leads to the stabilization of TREX2, a protein with exonuclease activity. TREX2 degrades double-stranded DNA and thus inhibits the cGAS-STING pathway, type I IFNs expression, and promotes tumor growth (Sun et al., 2025).

3.2 Therapeutic targeting of epigenetic dysregulation

Recent studies have demonstrated the therapeutic potential of targeting epigenetic regulators within the 9p21.3 locus (Supplementary Table S1). EZH2 inhibition, particularly with tazemetostat, has shown promise in preclinical models for restoring CDKN2B expression in CRC (Yang et al., 2021). Tazemetostat, a selective EZH2 inhibitor approved by the FDA for epithelioid sarcoma and relapsed/refractory follicular lymphoma (Hoy, 2020; Straining and Eighmy, 2022; Orleni and Beumer, 2024), demonstrated transcriptional activation of CDKN2B and attenuated CRC cell growth when combined with PRMT5 inhibitors in preclinical studies, indicating the potential for dual methyltransferase targeting. However, recent preclinical evidence indicates that EZH2 inhibition may paradoxically enhance PD-L1 protein stability through USP22-mediated deubiquitination in CRC, potentially creating immune suppressive effects that could be overcome through combination with immunotherapy (Huang J. et al., 2024). The CAIRE phase II trial evaluated tazemetostat plus durvalumab in patients with advanced microsatellite stable CRC, achieving the primary endpoint with a disease control rate of 35.3%, with circulating H3K27me3-modified nucleosomes serving as potential pharmacodynamic biomarkers for EZH2 target engagement (Palmieri et al., 2023).

Early clinical translation of DNMT inhibitors in CRC has been largely disappointing, with recurrent pharmacodynamic and trial-design limitations that likely explain modest/absent activity in pMMR/MSS disease. In the pre-operative DECO trial (NCT01882660), decitabine 25 mg/m2 on two consecutive days led only to a small but statistically significant drop in tumor LINE1 methylation (71.2% -> 67.2%, p = 0.0075) and did not change methylation/expression of WNT target genes or induce ERV/interferon programs, prompting premature closure after 10 treated patients (Linnekamp et al., 2021). In METADUR (NCT02811497), oral CC-486 plus durvalumab produced no objective responses (DCR 7.1%, median PFS 1.9 months) and showed minimal tumor demethylation with absent viral-mimicry signaling; PBMC LINE-1 demethylation was typically <10% (overall maximum 19.9%; maximum 13.8% in MSS-CRC), consistent with insufficient on-target activity in vivo (Taylor et al., 2020). Similarly, pembrolizumab plus low-dose subcutaneous azacitidine (100 mg days 1–5; NCT02260440) achieved ORR 3% and median PFS 1.9 months despite evidence of on-treatment tumor demethylation (10/15 paired biopsies, 67%), suggesting that biochemical demethylation alone - without optimal dose/schedule and biomarker enrichment - may be insufficient to consistently generate clinically meaningful immune priming in refractory mCRC (Kuang et al., 2022). Outside ICI combinations, a CIMP-enriched DNMTi/chemotherapy strategy (azacitidine + CAPOX; NCT01193517) likewise yielded no objective responses, although stable disease occurred in 65% (17/26; median duration 4.5 months), underscoring that patient selection by broad methylation phenotype alone does not guarantee antitumor responses (Overman et al., 2016). In contrast, the planned phase II NCT07007767 in heavily pretreated pMMR/MSS CRC evaluates decitabine “priming” combined with sintilimab and bevacizumab, attempting to pair epigenetic modulation with a backbone expected to be more permissive for immune infiltration; notably, locus-level selection (e.g., intact, hypermethylated 9p21.3) is not currently part of eligibility and should be considered for future iterations (Zhang, 2025).

Updated clinical evidence supports the immune-independent augmentation of chemotherapy by low-dose decitabine. The sequential combination of gemcitabine followed by decitabine has demonstrated synergistic effects through ribonucleotide reductase inhibition, providing a promising paradigm for enhancing chemotherapy efficacy while potentially reducing toxicity (Gutierrez et al., 2022). This approach differs from traditional DNA-demethylating pretreatment strategies and may be particularly relevant for tumors with epigenetically silenced 9p21.3 genes.

4 The role of 9p21.3 locus genes in the senescence in cancer

Senescence is a non-proliferative but viable state of a cell, usually induced by various stress factors. The senescent state is characterized by prolonged and usually irreversible cell cycle arrest with altered metabolism, secretory features, and macromolecular damage (Gorgoulis et al., 2019; Chambers et al., 2021).

Cell cycle arrest in senescence is usually irreversible, but cell cycle re-entry may occur under certain circumstances, especially in tumor cells (Patel et al., 2016; Le Duff et al., 2018; Guillon et al., 2019). Senescent cells are characterized by enlarged, flattened morphology and nuclear abnormalities–including an enlarged nucleus and loss of lamin B1, sustained expression of CDKN2A (p16INK4a) and/or CDKN1A (p21Cip1), heterochromatin remodeling (senescence-associated heterochromatin foci, SAHF), mitochondrial dysfunction, metabolic rewiring, and increased lysosomal β-galactosidase activity (SA-β-gal). A defining hallmark is the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) – a coordinated program of cytokines (e.g., IL-6, IL-8), chemokines, growth factors, and matrix-remodeling enzymes–that actively reshapes the tumor microenvironment and is therefore highly consequential for tumorigenesis, immune surveillance, and therapeutic response (Schmitt et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2022).

Historically, senescence of cancer cells was viewed as a barrier to malignant progression (Haferkamp et al., 2009), but more recent work shows that senescent tumor cells can also promote disease via SASP-driven protumorigenic effects (Kim et al., 2017; Choi et al., 2021). Both senescent cancer cells and non-transformed senescent cells residing in the tumor microenvironment can affect treatment outcomes in CRC (Bogdanova et al., 2024; Pukhalskaia et al., 2024). Multiple modalities–including classical cytotoxics, targeted agents, and immunotherapies–can induce therapy-induced senescence (TIS) (Wang et al., 2022). Similarly, demethylating therapies can trigger this process through reactivation of cell cycle inhibitors at the 9p21.3 locus. Moreover, cellular senescence can be induced by oncogenic activation, a process known as oncogene-induced senescence (OIS) (Bartkova et al., 2006).

The following sections analyze the contributions of the 9p21.3 locus to the biology of senescence in cancer, with an emphasis on CRC, while highlighting the complementary functions described in other tumor types that suggest testable hypotheses regarding their relevance in CRC.

4.1 The regulation of CDKN2A/B in senescence

The CDKN2A/B gene products, p16INK4a, p15INK4b, and p14ARF, induce cell cycle arrest that could become permanent if their expression persists, provoking the formation of a senescent phenotype.

Interestingly, the expression of the CDKN2A/B genes, which are major regulators of senescence, is controlled by neighboring genes. During normal cell cycle progression, p16INK4a, p15INK4b, and p14ARF are inhibited by Polycomb proteins, which are recruited by the long noncoding RNA ANRIL. Thus, ANRIL prevents cell cycle arrest (Muniz et al., 2020). A 2016 study showed that ANRIL is overexpressed in CRC and that it positively influences cell proliferation (Naemura et al., 2016). In this case, inhibition of ANRIL resulted in decreased proliferation. It was also noted that ANRIL inhibition did not result in activation of CDKN2A/B expression. Increased ANRIL expression in CRC was also observed in another study, with it being highest at the metastatic stage (Drak Alsibai et al., 2019). A later study by Lisa Muniz et al. showed that ANRIL can act as an activator of CDKN2A/B expression in circular isoforms during OIS initiation in fibroblast cultures (Muniz et al., 2020). The researchers suggest that this effect is observed because circular ANRIL can bind to suppressor proteins Polycomb and thus make the chromatin conformation open. Another long non-coding RNA that increases CDKN2A/B expression including in CRC cells is P14AS, which can also bind to the Polycomb protein (Li Z. et al., 2022).

Methyltransferase METTL3, which increases the stability of CDKN2B mRNA, is also involved in maintaining the formation of senescent cells in CRC (Chen Z. et al., 2024). It has been shown that there is a positive correlation between CDKN2B expression and tumor infiltration by tumor-associated macrophages (Chen Z. et al., 2024). Thus, increased CDKN2B expression not only leads to the formation of senescent cells, but also affects the tumor microenvironment, making it immunosuppressive.

4.2 The role of type I IFNs in senescence

When DNA double-strand breaks occur, one of the key proteins that activates is ATM kinase which triggers a cascade of reactions leading to phosphorylation and activation of p53, a transcription factor that is one of the main tumor suppressors. p53 triggers the expression of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor CDKN1А (Schmitt et al., 2022). However, this is not the only effect of ATM activation. It has been shown both in vitro and in vivo that ATM can also activate IRF3 which triggers the expression of IFNβ1. The resulting IFNβ increases the expression of CDKN1А and CDKN2A/B, thereby contributing to the establishment of senescence (Yu et al., 2015). Also, as noted above, other studies highlight cell cycle arrest and senescence induction by type I IFNs via CDKN1A, CDKN1B, and CDKN2B (Katayama et al., 2007; Musella et al., 2021; Mödl et al., 2023). Type I IFNs play a significant role in the development of senescence. Yulia V. Katlinskaya et al. demonstrated that inhibition of interferon signaling resulted in suppression of senescence and the development of melanoma (Katlinskaya et al., 2016).

Several studies have examined the hypothesis that cellular senescence is a defense against viruses (Reddel, 2010; Yu et al., 2015). There is a correlation between the amount of type I IFNsproduced and the number of double-strand breaks that can occur as a result of infection by genome integrating viruses (Yu et al., 2015; Ryan et al., 2016). So, the increase in type I IFNs synthesis in response to DNA damage may initially be associated with antiviral protection. The activation of type I IFNs synthesis may be also associated with the transcriptional depression of the LINE-1 retrotransposon element observed during senescence which was shown in human fibroblasts (Cecco et al., 2019).

Type I IFNs are also a component of the SASP secretome (Birch and Gil, 2020). Type I IFNs may be involved in maintaining chronic inflammation in the tumors (Cecco et al., 2019; Wang D. et al., 2024). Conversely, it has been shown that type I IFNs secreted by SASP can promote the destruction of senescent cells in the tumor by attracting NK cells since type I IFNs increase the expression of NK cell receptor ligands (Katlinskaya et al., 2015).

Thus, type I IFNs are essential for promoting senescence and maintaining their secretory phenotype. However, their role as a component of the SASP in tumors is not clear. On the one hand, type I IFNs can maintain chronic inflammation, and on the other hand, they can promote the removal of tumor cells.

4.3 Senescence-targeted therapeutic strategies

The role of 9p21.3-encoded proteins p16INK4a and p15INK4b in cellular senescence creates potential therapeutic opportunities through senolytic agents. These proteins are central regulators of senescence induction, and their methylation-mediated silencing may affect therapy-induced senescence responses (Jung et al., 2020).

A recent study in 2025 showed that cancer cells with decreased DNA methylation enter cellular senescence. Experiments with xenografts show that tumor cells can be induced to undergo senescence in vivo by reducing DNA methylation (Chen et al., 2025). These results highlight the importance of epigenetic changes and reduced DNA methylation in cancer cells, which may have practical implications for future therapeutic approaches.

Preclinical studies have explored senolytic agents such as quercetin, navitoclax, and fisetin in CRC models (Russo et al., 2023; Bogdanova et al., 2024). However, clinical data remain limited, and recent evidence raises safety concerns about potential tumor-promoting effects of certain senolytic agents (Wyld et al., 2020). In CRC specifically, some senolytic agents may differentially affect SASP components, potentially promoting epithelial-mesenchymal transition and tumor progression (Gallegos et al., 2023).

Emerging evidence supports rational combination strategies targeting multiple epigenetic pathways within the 9p21.3 locus. Recent preclinical studies demonstrate that combining DNA methyltransferase inhibitors with histone methyltransferase inhibitors can overcome adaptive resistance mechanisms. In BRAFV600E CRC models, 5-azacitidine treatment induced compensatory H3K27 trimethylation at demethylated genomic regions, but combination with EZH2 or RNF2 inhibitors showed additive growth inhibitory effects. This finding suggests that adaptive interactions between epigenetic modifiers may limit single-agent efficacy and supports the development of combinatorial epigenetic therapeutic strategies (Lee et al., 2024). The concept of sequential epigenetic priming followed by targeted therapy represents a promising approach for restoring 9p21.3 tumor suppressor function in CRC.

Current clinical trials of senolytic agents extends beyond age-related diseases into cancer, yet specific studies remain sparse and are rarely designed to explicitly test senolytic mechanisms. For instance, navitoclax appears only in a trametinib combination cohort without senescence biomarker readouts, while isoquercetin has been evaluated for VTE prevention rather than senolysis [National Cancer Institute (NCI), 2025]. Trials with dasatinib in CRC have focused on its role as a SRC kinase inhibitor rather than leveraging its senolytic potential, and designs with dasatinib + quercetin or others senolytic compounds specifically in CRC are lacking, while senescence-focused biomarker stratification (e.g., p16INK4a/SASP panels; linkage to 9p21.3 methylation) is rarely incorporated [National Cancer Institute (NCI), 2014]. Preclinical investigations reveal significant therapeutic potential through “one-two punch” approaches that first induce senescence followed by senolytic elimination (Khosla, 2024; Czajkowski et al., 2025; López et al., 2025; St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, 2025).

However, clinical translation of senolytic strategies in colorectal cancer faces significant challenges and remains largely experimental. Most available evidence derives from preclinical models, which may not fully recapitulate the complexity of human CRC biology. Furthermore, recent preclinical studies have revealed concerning safety signals, including differential effects of senolytic agents on SASP components and potential promotion of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. For instance, while navitoclax effectively reduces IL-6 secretion in senescent CAFs, the dasatinib-quercetin combination paradoxically increases IL-6 levels and promotes tumor cell migration in colorectal cancer models (Bogdanova et al., 2024). These findings underscore the necessity of tailoring senolytic timing and combinations to modulate SASP appropriately and emphasize the need for more careful evaluation of senolytic strategies before clinical implementation.

Recent clinical trials provide compelling evidence for senolytic efficacy in cancer-adjacent applications. The SENSURV trial (NCT04733534) at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital represents a landmark Phase 2 study evaluating dasatinib plus quercetin versus fisetin monotherapy in 110 adult survivors of childhood cancer. This trial specifically measures senescent cell abundance (primary outcome: p16INK4a) and frailty markers, establishing crucial biomarkers for senolytic efficacy assessment (St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, 2025). The Mayo Clinic skeletal health study (NCT04313634) further validates senolytic mechanisms, administering intermittent dasatinib (100 mg) plus quercetin (1,000 mg) cycles to elderly postmenopausal women, demonstrating measurable reductions in senescent cell burden and inflammatory markers (Khosla, 2024). Most significantly, the Mayo Clinic glioma trial (NCT07025226) represents the first sequential senolytic cancer treatment protocol, employing dasatinib-quercetin combinations followed by fisetin and temozolomide in previously treated patients (Mayo Clinic, 2025). Additionally, a Phase 2 triple-negative breast cancer trial (NCT06355037) is currently recruiting patients to evaluate dasatinib (50 mg) plus quercetin (1000 mg) combined with chemotherapy to reverse treatment resistance, based on preclinical evidence showing effective elimination of chemotherapy-induced senescent fibroblasts (Shao, 2024).

Moreover, a “one-two punch” approach combining talazoparib with palbociclib induces robust therapy-induced senescence in CRC xenografts, and subsequent PD-L1 blockade eradicates senescent cells to deliver significant survival benefits in immunocompetent mice. Comparable senolytic selectivity extends beyond CRC: in glioblastoma models, navitoclax reduces viability of senescent cells by over 60% with minimal impact on proliferating cells, demonstrating BCL-XL dependency across radiated and TMZ-treated human glioma cell lines (Rahman et al., 2022). In lung adenocarcinoma A549 cells, therapy-induced senescence similarly confers high sensitivity to BCL-XL-targeting agents such as A1331852, with marked senolytic selectivity observed across multiple TIS phenotypes (López et al., 2025). These findings underscore the necessity of tailoring senolytic timing and combinations to modulate SASP appropriately and maximize anti-tumor efficacy (Wang et al., 2023; Czajkowski et al., 2025) and emphasizing the need for more careful evaluation of senolytic strategies before clinical implementation. Similarly, venetoclax (ABT-199), a navitoclax derivative, demonstrated senolytic efficacy in APTKA orthotopic rectal cancer models, where venetoclax treatment significantly reduced tumor burden, suppressed invasive growth, and prevented liver metastasis formation when combined with radiotherapy. The combination also led to decreased collagen deposition, reduced DCN + fibroblast numbers, and enhanced CD8+ T cell infiltration. However, venetoclax exhibited dual effects, as it also directly impaired organoid growth ex vivo, particularly in non-irradiated conditions, suggesting that improved therapeutic responses may result from both senolytic activity and direct pro-apoptic effects on tumor cells (Nicolas et al., 2022). Nevertheless, proof-of-concept studies continue to demonstrate therapeutic potential.

4.4 Integrated biomarker-guided therapeutic algorithm

To translate the complex landscape of 9p21.3 alterations into clinical utility, we propose a stratified therapeutic algorithm based on the structural and epigenetic status of the locus (Supplementary Table S2). This framework distinguishes between irreversible genomic loss (deletions) and reversible epigenetic silencing (methylation), integrating recent advances in synthetic lethality and immunotherapy (Song and Yang, 2025; Subramaniam et al., 2025).

4.4.1 Structural deletion of 9p21.3 (MTAP-deficient/type I IFNs-null)

Tumors harbouring homozygous deletions of 9p21.3 invariably lose MTAP and frequently the IFN-I gene cluster alongside CDKN2A/B. These tumors are characteristically ‘immune-cold’ due to the loss of type I interferon signaling, rendering them potentially resistant to immune checkpoint blockade monotherapy. Therapeutic strategy: the primary vulnerability is metabolic. MTAP loss creates a synthetic lethal dependence on the PRMT5-MAT2A axis (Gounder et al., 2025). MTA-cooperative PRMT5 inhibitors (for example, MRTX1719) and MAT2a inhibitors (Cann et al., 2023; Helwick, 2024; Andre et al., 2025) (e.g., IDE397) have shown efficacy in recent years in solid tumors (Cann et al., 2023; Helwick, 2024; Andre et al., 2025). Combination approach to overcome the “cold” immune microenvironment, combining PRMT5 inhibitors with immune checkpoint blockade is promising. Emerging data suggest that PRMT5 inhibition can sensitize tumor cells to T-cell mediated cytotoxicity and downregulate immune-exclusionary pathways (e.g., PI3K), offering a rationale for combination even in the context of compromised IFN signaling (Chen S. et al., 2024; Bartosik et al., 2025; Song and Yang, 2025).

4.4.2 Intact 9p21.3 with hypermethylation (CIMP-H/CDKN2A-silenced)

This subset retains the genetic code for CDKN2A and type I IFNs, but suppresses them epigenetically. These tumors frequently overlap with MSI-H phenotype and high tumor mutational burden (Reyila et al., 2025). Therapeutic strategy: reversal of silencing is key. DNMTi like azacitidine or decitabine can demethylate the CDKN2A promoter, restoring p16INK4a expression and re-activiting the viral mimicry dsRNA pathways (Roulois et al., 2015). Demethylation therapy also restore the expression of type I IFNs, which can contribute to the tumor becoming “hot”. Combinational approaches are: a) Immune checkpoint inhibitors-responsive: standard of care involves anti-PD-1/CTLA-4 regimens (e.g., nivolumab + ipilimumab), which demonstrated superior progression-free survival in recent Phase III trials (CheckMate 8HW) (Cann et al., 2023; Helwick, 2024; Andre et al., 2025). Adding DNMTi could deepen responses in refractory cases, enhancing antigen presentation senescence-targeted: re-expression of p16INK4avia DNMTi acts as a “senogenic” stimulus, arresting tumor cells (Huang K. C.-Y. et al., 2024; 2025). This created a therapeutic window for “senolytic” agents (e.g., BCL-2/xL inhibitors) to selectively eliminate the arrested senescent cells - a sequential “one-two punch” strategy (Wang Y. et al., 2024; Lam et al., 2025; Tajudeen et al., 2025).

4.4.3 Intact 9p21.3 with low methylation (CIMP-L/MSS)

These tumors generally express functional MTAP and basal levels of p16INK4a, but lack the high immunogenicity of MSI-H tumors. Therapeutic strategy: the focus shifts to inducing immunogenicity and senescence. Сombination approach, standard chemotherapy or CDK4/6 inhibitors can define the senogenic step, followed by senolytic clearance (Wang Y. et al., 2024; Subramaniam et al., 2025).

5 Conclusion

A better understanding of genetic and epigenetic regulatory mechanisms, particularly cancer-specific changes, will facilitate the study of their potential clinical applications as biomarkers or therapeutic targets in colorectal cancer. To date, accumulated data provide compelling evidence that epigenetic dysregulation is an important factor in colorectal cancer progression and therapeutic resistance development. In particular, DNA hypermethylation of tumor suppressor gene promoter regions is associated with a poor prognosis, an increased risk of relapse and metastasis, and a reduced effectiveness of standard therapeutic approaches. CDKN2A hypermethylation is the most indicative in this regard and has repeatedly been shown to be associated with poor survival for patients.

Locus 9p21.3 is a unique gene cluster combining cell cycle and senescence control genes (CDKN2A/CDKN2B), immune response modulators (IFN-I gene cluster), and metabolic factors (MTAP, MLLT3). Disruption of the expression of these genes due to hypermethylation or deletion can lead to the loss of antitumor checkpoints, reduced tumor immunogenicity, and resistance to therapy. Therefore, status of the 9p21.3 locus is a promising biomarker for patient stratification and therapy selection.

This approach enables us to stratify patients for whom the epigenetic reactivation of the locus can restore cell cycle control, enhance the antitumor immune response, and improve the effectiveness of follow-up treatment. Concurrently, the dual role of type I IFNs and senescence in tumors underscores the necessity of strictly controlling the timing and duration of demethylating therapy and considering the use of senolytic agents to mitigate the adverse effects of chronic senescence.

On the other hand, for cases involving the deletion of 9p21.3, an alternative approach based on exploiting the synthetic lethality between MTAP deficiency and the use of PRMT5/MT2A inhibitors would benefit this cohort of CRC patients.

It is important to note that all clinical studies evaluating epigenetic therapy for colorectal cancer were conducted on patients with advanced stages of the disease for whom other treatments had been ineffective. Under these conditions, the use of demethylating drugs as monotherapy predictably demonstrated limited effectiveness. Additionally, accumulated data suggest the potential of using demethylating agents not as standalone treatments but as tools for epigenetic “priming” that increase tumor sensitivity to chemotherapy, radiation, and immunotherapy (Jung et al., 2020).

In conclusion, DNA methylation biomarkers are widely associated with prognosis and survival. However, their applications as biomarkers that could alter current treatment strategies are limited. Nevertheless, we believe that the biomarkers presented here warrant further evaluation in prospective studies due to the highly promising preliminary data on their utility.

Statements

Author contributions

DL: Investigation, Writing – review and editing, Resources, Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft, Visualization. VS: Writing – review and editing, Resources, Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft, Investigation. AN: Resources, Visualization, Investigation, Formal Analysis, Writing – review and editing, Writing – original draft. OD: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Writing – review and editing, Supervision. DB: Investigation, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Formal Analysis, Resources, Project administration, Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This research was funded by RSF grant 25-25-20134. DB is a recipient of the “Programme Ostrogradski” scholarship given by the French government.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author OD declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcell.2026.1741704/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Abdel-Rahman W. M. Nieminen T. T. Shoman S. Eissa S. Peltomaki P. (2014). Loss of p15INK4b expression in colorectal cancer is linked to ethnic origin. Asian Pac J. Cancer Prev.15, 2083–2087. 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.5.2083

2

Ahlquist T. Lind G. E. Costa V. L. Meling G. I. Vatn M. Hoff G. S. et al (2008). Gene methylation profiles of normal mucosa, and benign and malignant colorectal tumors identify early onset markers. Mol. Cancer7, 94. 10.1186/1476-4598-7-94

3

Alum E. U. Izah S. C. Uti D. E. Ugwu O. P.-C. Betiang P. A. Basajja M. et al (2025). Targeting cellular senescence for healthy aging: advances in senolytics and senomorphics. Drug Des. Develop. Ther.19, 8489–8522. 10.2147/DDDT.S543211

4

Andre T. Elez E. Van Cutsem E. Jensen L. H. Bennouna J. Mendez G. et al (2024). Nivolumab (NIVO) plus ipilimumab (IPI) vs chemotherapy (chemo) as first-line (1L) treatment for microsatellite instability-high/mismatch repair-deficient (MSI-H/dMMR) metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC): first results of the CheckMate 8HW study. J. Clin. Oncol.42, LBA768. 10.1200/JCO.2024.42.3_suppl.LBA768

5

Andre T. Elez E. Lenz H.-J. Jensen L. H. Touchefeu Y. Van Cutsem E. et al (2025). First results of nivolumab (NIVO) plus ipilimumab (IPI) vs NIVO monotherapy for microsatellite instability-high/mismatch repair-deficient (MSI-H/dMMR) metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) from CheckMate 8HW. J. Clin. Oncol.43, LBA143. 10.1200/JCO.2025.43.4_suppl.LBA143

6

Barekatain Y. Ackroyd J. J. Yan V. C. Khadka S. Wang L. Chen K.-C. et al (2021). Homozygous MTAP deletion in primary human glioblastoma is not associated with elevation of methylthioadenosine. Nat. Commun.12, 4228. 10.1038/s41467-021-24240-3

7

Barriga F. M. Tsanov K. M. Ho Y.-J. Sohail N. Zhang A. Baslan T. et al (2022). MACHETE identifies interferon-encompassing chromosome 9p21.3 deletions as mediators of immune evasion and metastasis. Nat. Cancer3, 1367–1385. 10.1038/s43018-022-00443-5

8

Bartkova J. Rezaei N. Liontos M. Karakaidos P. Kletsas D. Issaeva N. et al (2006). Oncogene-induced senescence is part of the tumorigenesis barrier imposed by DNA damage checkpoints. Nature444, 633–637. 10.1038/nature05268

9

Bartosik A. Radzimierski A. Bobowska A. Więckowska A. Kuś K. Faber J. et al (2025). Abstract 4231: preclinical candidate RVU305, an MTA-cooperative PRMT5 inhibitor, shows activity in MTAP-deleted tumors resistant to immune checkpoint treatment. Cancer Res.85, 4231. 10.1158/1538-7445.AM2025-4231

10

Bedard G. T. Gilaj N. Peregrina K. Brew I. Tosti E. Shaffer K. et al (2023). Combined inhibition of MTAP and MAT2a mimics synthetic lethality in tumor models via PRMT5 inhibition. J. Biol. Chem. 300, 105492. 10.1016/j.jbc.2023.105492

11

Belhadj S. Terradas M. Munoz-Torres P. M. Aiza G. Navarro M. Capellá G. et al (2020). Candidate genes for hereditary colorectal cancer: mutational screening and systematic review. Hum. Mutat.41, 1563–1576. 10.1002/humu.24057

12

Berardinelli G. N. Scapulatempo-Neto C. Durães R. Antônio de Oliveira M. Guimarães D. Reis R. M. (2018). Advantage of HSP110 (T17) marker inclusion for microsatellite instability (MSI) detection in colorectal cancer patients. Oncotarget9, 28691–28701. 10.18632/oncotarget.25611

13

Bihl M. P. Foerster A. Lugli A. Zlobec I. (2012). Characterization of CDKN2A(p16) methylation and impact in colorectal cancer: systematic analysis using pyrosequencing. J. Transl. Med.10, 173. 10.1186/1479-5876-10-173

14

Birch J. Gil J. (2020). Senescence and the SASP: many therapeutic avenues. Genes Dev.34, 1565–1576. 10.1101/gad.343129.120

15

Bogdanova D. A. Kolosova E. D. Pukhalskaia T. V. Levchuk K. A. Demidov O. N. Belotserkovskaya E. V. (2024). The differential effect of senolytics on SASP cytokine secretion and regulation of EMT by CAFs. Int. J. Mol. Sci.25, 4031. 10.3390/ijms25074031

16

Brand F. Förster A. Christians A. Bucher M. Thomé C. M. Raab M. S. et al (2020). FOCAD loss impacts microtubule assembly, G2/M progression and patient survival in astrocytic gliomas. Acta Neuropathol.139, 175–192. 10.1007/s00401-019-02067-z

17

Bray F. Laversanne M. Sung H. Ferlay J. Siegel R. L. Soerjomataram I. et al (2024). Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin.74, 229–263. 10.3322/caac.21834

18

Cann C. G. LaPelusa M. B. Cimino S. K. Eng C. (2023). Molecular and genetic targets within metastatic colorectal cancer and associated novel treatment advancements. Front. Oncol.13, 1176950. 10.3389/fonc.2023.1176950

19

Cao Q. Tian Y. Deng Z. Yang F. Chen E. (2024). Epigenetic alteration in colorectal cancer: potential diagnostic and prognostic implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci.25, 3358. 10.3390/ijms25063358

20

Casak S. J. Marcus L. Fashoyin-Aje L. Mushti S. L. Cheng J. Shen Y.-L. et al (2021). FDA Approval Summary: pembrolizumab for the first-line treatment of patients with MSI-H/dMMR advanced unresectable or metastatic colorectal carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res.27, 4680–4684. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-0557

21

Cecco M. D. Ito T. Petrashen A. P. Elias A. E. Skvir N. J. Criscione S. W. et al (2019). LINE-1 derepression in senescent cells triggers interferon and inflammaging. Nature566, 73–78. 10.1038/s41586-018-0784-9

22

Chambers C. R. Ritchie S. Pereira B. A. Timpson P. (2021). Overcoming the senescence‐associated secretory phenotype (SASP): a complex mechanism of resistance in the treatment of cancer. Mol. Oncol.15, 3242–3255. 10.1002/1878-0261.13042

23

Chen W. Swanson B. J. Frankel W. L. (2017). Molecular genetics of microsatellite-unstable colorectal cancer for pathologists. Diagn. Pathol.12, 24. 10.1186/s13000-017-0613-8

24

Chen K. Chen W. Yue R. Zhu D. Cui S. Zhang X. et al (2024a). Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of first- and second-line immunotherapy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: a systematic review and network meta-analysis based on randomized controlled trials. Front. Immunol.15, 1439624. 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1439624

25

Chen S. Hou J. Jaffery R. Guerrero A. Fu R. Shi L. et al (2024b). MTA-cooperative PRMT5 inhibitors enhance T cell-mediated antitumor activity in MTAP-loss tumors. J. Immunother. Cancer12, e009600. 10.1136/jitc-2024-009600

26

Chen Z. Zhou J. Wu Y. Chen F. Li J. Tao L. et al (2024c). METTL3 promotes cellular senescence of colorectal cancer via modulation of CDKN2B transcription and mRNA stability. Oncogene43, 976–991. 10.1038/s41388-024-02956-y

27

Chen X. Yamaguchi K. Rodgers B. Goehrig D. Vindrieux D. Lahaye X. et al (2025). DNA methylation protects cancer cells against senescence. Nat. Commun.16, 5901. 10.1038/s41467-025-61157-7

28

Cheng X. Yang F. Li Y. Cao Y. Zhang M. Ji J. et al (2024). The crosstalk role of CDKN2A between tumor progression and cuproptosis resistance in colorectal cancer. Aging (Albany NY)16, 10512–10538. 10.18632/aging.205945

29

Chiappinelli K. B. Strissel P. L. Desrichard A. Li H. Henke C. Akman B. et al (2015). Inhibiting DNA methylation causes an interferon response in cancer via dsRNA including endogenous retroviruses. Cell162, 974–986. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.011

30

Chin E. N. Sulpizio A. Lairson L. L. (2023). Targeting STING to promote antitumor immunity. Trends Cell Biol.33, 189–203. 10.1016/j.tcb.2022.06.010

31

Choi Y. W. Kim Y. H. Oh S. Y. Suh K. W. Kim Y. Lee G. et al (2021). Senescent tumor cells build a cytokine shield in colorectal cancer. Adv. Sci. (Weinh)8, 2002497. 10.1002/advs.202002497

32

Cilluffo D. Barra V. Di Leonardo A. (2020). P14ARF: the absence that makes the difference. Genes (Basel)11, 824. 10.3390/genes11070824

33

Colle R. Lonardi S. Cachanado M. Overman M. J. Elez E. Fakih M. et al (2023). BRAF V600E/RAS mutations and Lynch syndrome in patients with MSI-H/dMMR metastatic colorectal cancer treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Oncologist28, 771–779. 10.1093/oncolo/oyad082

34