Abstract

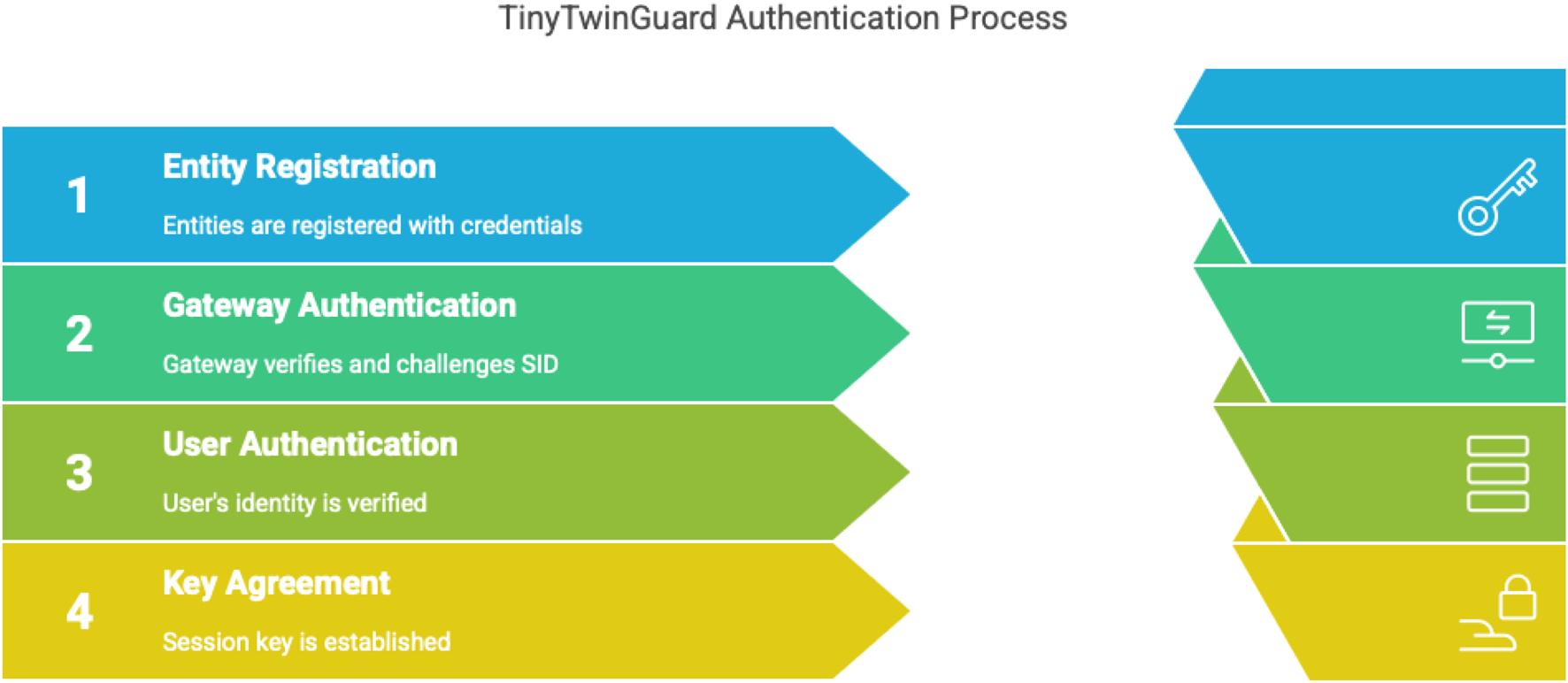

Digital Twin Edge Networks (DITEN) encounter significant challenges in balancing security and efficiency, as many existing authentication mechanisms either fail to deliver full security guarantees, such as perfect forward secrecy or protection against insider threats, or impose excessive overhead due to the use of ECC or RSA cryptographic primitives. To overcome these limitations, we introduce TinyTwinGuard (TTG), a lightweight authentication protocol designed specifically for DITEN environments and built upon the NIST-standardized TinyJAMBU Authenticated Encryption with Associated Data (AEAD) cipher. Using formal validation with the AVISPA framework and extensive experimental evaluation on Raspberry Pi 4B devices, we show that TTG satisfies a broad set of 13 security requirements relevant to DITEN, including user anonymity, resistance to privileged insider attacks, and perfect forward secrecy. Although TTG incurs slightly higher communication overhead than minimal hash-based approaches, with 4,896 bits compared to 2,560 bits, it achieves a 43.7% reduction in computational cost relative to ECC-based schemes and lowers energy consumption by 58.3%. Overall, these findings indicate that TTG achieves an effective balance between strong security and operational efficiency, making it well suited for industrial edge scenarios where both resilience and deployment practicality are essential.

Highlights

Novel Authentication Scheme: Introduces TinyTwinGuard (TTG), an innovative authentication scheme that utilizes TinyJAMBU to enhance security and efficiency in Digital Twin Edge Networks (DITEN).

Efficiency Improvements: Demonstrates significant reductions in computational overhead and energy consumption compared to traditional authentication methods, such as ASCON, making TTG highly suitable for resource-constrained edge computing environments.

Comprehensive Security Analysis: Provides rigorous security analysis showing that TinyTwinGuard meets essential security requirements, including data integrity, confidentiality, and robust authentication.

Empirical Performance Evaluation: Empirically evaluates and validates the performance of TTG, revealing its superior efficiency and effectiveness in practical industrial applications, thereby advancing the state of authentication in edge networks.

1 Introduction

The Internet of Things (IoT) signifies a revolutionary shift in technology, characterized by the pervasive interconnection of physical devices through the Internet (El-Hajj et al., 2017). These devices encompass a wide spectrum, from common household items to sophisticated industrial machinery, embedded with sensors and software that enable data collection and communication (El-Hajj et al., 2023). The exponential growth in IoT devices generates vast quantities of data, necessitating efficient methods for data processing and management (El-Hajj et al., 2019).

While IoT represents a broad paradigm of interconnected devices exchanging data over the internet, Digital Twin Edge Networks (DITEN) represent a specialized evolution tailored for industrial applications. Unlike traditional IoT, which primarily focuses on data collection and remote monitoring, DITEN integrates digital twin technology with edge computing to create virtual replicas of physical systems that operate in real-time.

The distinctions between IoT and DITEN are rooted in their scope, architecture, functionality, and security requirements. IoT broadly encompasses a wide array of applications, ranging from consumer devices to industrial sensors, whereas DITEN is specifically designed for industrial environments that demand real-time insights and system optimization. Architecturally, IoT often relies on centralized cloud processing, which can introduce latency and bandwidth issues. In contrast, DITEN leverages edge computing to process data locally, significantly reducing delays and optimizing resource usage. Functionally, while IoT emphasizes connectivity and data exchange, DITEN goes further by enabling real-time monitoring, predictive maintenance, and system optimization through digital twin simulations. Additionally, DITEN introduces unique security challenges, particularly in ensuring secure communication between physical devices, their virtual counterparts, and edge nodes—a concern that is less pronounced in general IoT applications.

These distinctions highlight how DITEN offers a more advanced framework for managing complex industrial systems, enhancing operational efficiency and decision-making capabilities. Edge computing plays a crucial role in this advancement by executing computations closer to the data source, minimizing latency, and reducing bandwidth consumption. This approach is especially valuable in scenarios requiring swift responses, such as industrial applications (Yu et al., 2017). The combination of IoT and edge computing has paved the way for frameworks like DITEN, which leverage digital twins to provide real-time insights and simulations (van der Wal and El-Hajj, 2022). When integrated with edge computing, digital twins offer enhanced operational efficiency, predictive maintenance, and system optimization (Liu et al., 2021). However, as data exchange between physical and digital components increases, ensuring robust security measures becomes critical to protect data integrity and confidentiality (Sai et al., 2024).

Despite their potential, DITEN faces significant challenges in implementing secure and efficient authentication mechanisms. Current cryptographic algorithms, such as ASCON (Dobraunig et al., 2021), AES (Abdullah, 2017), and ChaCha20 (Mahdi et al., 2021), present notable limitations in resource-constrained edge environments. While ASCON offers strong security features, it is computationally intensive and energy-consuming. AES, despite its widespread adoption, incurs high computational costs, particularly in constrained settings (Thakor et al., 2021). Similarly, ChaCha20, though efficient in software, demands substantial processing power in certain scenarios (Tian and Vassilakis, 2023). These inefficiencies hinder performance in edge computing environments, where minimizing latency and conserving resources are critical.

To address these gaps, lightweight cryptographic solutions tailored to the unique requirements of edge computing are increasingly needed. TinyJAMBU (Saha et al., 2020), a lightweight authenticated encryption algorithm, provides a promising alternative. Its design focuses on reducing computational complexity and energy usage, making it particularly well-suited for edge-computing scenarios (El-Hajj et al., 2025). By leveraging TinyJAMBU, we can enhance both the security and efficiency of authentication processes within DITEN.

In response to these challenges, this paper introduces TinyTwinGuard (TTG), a novel authentication scheme specifically designed for DITEN. TTG leverages the TinyJAMBU algorithm to provide a highly efficient solution for secure authentication in resource-constrained edge environments. The primary objectives of this research are:

To address the limitations of current authentication schemes by proposing a lightweight and secure solution tailored to DITEN.

To demonstrate the theoretical advantages of TTG over traditional schemes, highlighting its reduced computational overhead and energy efficiency.

To empirically validate the effectiveness of TTG through experiments conducted in edge computing environments, showcasing improvements in authentication speed and energy efficiency.

We employ a comprehensive methodology to achieve these objectives, including theoretical analysis, rigorous security evaluations, and empirical assessments. Our theoretical analysis highlights the efficiency of TinyJAMBU in terms of computational and energy savings, while our empirical evaluations provide evidence of TTG’s superior performance compared to existing algorithms. These findings support the practical adoption of TTG in industrial settings.

The contributions of this paper are as follows:

Novel Authentication Scheme: We propose TTG, a lightweight authentication scheme specifically designed for DITEN. TTG leverages the TinyJAMBU algorithm to provide a secure and efficient solution for resource-constrained edge environments.

Enhanced Efficiency: Our scheme significantly reduces computational overhead and energy consumption compared to traditional methods like ASCON and AES. This makes TTG highly suitable for real-time applications in industrial IoT and edge computing.

Comprehensive Security Analysis: We provide a rigorous security analysis, demonstrating that TTG meets essential security requirements such as data integrity, confidentiality, and robust authentication.

Empirical Validation: Through experiments conducted in real-world edge computing scenarios, we validate the performance of TTG. The results show that TTG outperforms existing solutions in terms of authentication speed and energy efficiency, making it practical for industrial applications.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews relevant related work in authentication schemes for edge and IoT environments. Section 3 introduces the foundational concepts and cryptographic mechanisms underpinning TTG, including TinyJAMBU, fuzzy extractors, and extended Chebyshev polynomials. Section 4 outlines the system and adversary models, detailing the DITEN architecture and threat assumptions. Section 5 presents the proposed TTG authentication scheme, covering system setup, registration, user login, mutual authentication, and key agreement phases. Sections 6, 7 provide a comprehensive formal and heuristic security analysis and a detailed performance evaluation, respectively. Finally, Section 8 concludes the paper and outlines directions for future research.

2 Related work

Authentication and Key Agreement (AKA) schemes for IoT systems have evolved along three primary research trajectories: multi-factor authentication, lightweight cryptography, and edge-centric security frameworks. In this section, we analyze representative works across these categories, emphasizing their limitations in addressing the unique challenges of DITEN.

2.1 Categorization of existing schemes

To provide a structured overview, we categorize existing AKA schemes into four thematic groups:

Multi-Factor Authentication: Combines multiple factors (e.g., passwords, biometrics, smart cards) to enhance security but often incurs high computational overhead.

Lightweight Cryptography: Focuses on minimizing resource consumption using lightweight cryptographic primitives but may lack real-time capabilities or robust security features.

Edge-Centric Frameworks: Tailored for edge computing environments but often lacks integration with digital twin technologies or dynamic device management.

Blockchain-Assisted Protocols: Leverages blockchain for decentralized authentication but introduces significant latency due to consensus mechanisms.

2.2 Multi-factor authentication

Multi-factor authentication schemes aim to enhance security by combining multiple credentials, such as passwords, biometrics, and smart cards. Singh et al. (Singh and Kumar, 2022) proposed a multi-modal biometric scheme that uses iris scans and fingerprint templates to achieve 99.4% authentication accuracy. However, their approach requires 1.2 s for feature extraction and 1.8 MB of storage per user, making it unsuitable for DITEN’s real-time control loops and resource-constrained devices. Similarly, Wang et al. (Wang et al., 2020) introduced a three-factor authentication scheme using elliptic curve cryptography (ECC). While their approach enhances resilience against stolen smart card attacks, it suffers from high computational costs, with ECC scalar multiplication operations taking approximately 9.35 ms each, leading to a total latency of 320 ms—far exceeding DITEN’s 30 ms latency budget for digital twin synchronization. These schemes highlight the trade-offs between security and efficiency, often prioritizing the former at the expense of real-time performance.

2.3 Lightweight cryptographic protocols

Lightweight cryptographic protocols focus on minimizing computational overhead and energy consumption, making them suitable for resource-constrained IoT devices. Chen et al. (Chen and Li, 2021) designed a sponge-based protocol that consumes only 0.9 mJ per authentication. Despite its energy efficiency, the scheme is vulnerable to side-channel attacks due to timing information leakage during sponge absorption phases. Vinoth et al. (Vinoth et al., 2020) optimized AES-128 for data-type-aware key scheduling, reducing energy consumption by 22%. However, their approach does not support dynamic adjustments to varying device densities, a key requirement in DITEN. Additionally, their scheme incurs a latency of 45 ms, which is too high for real-time digital twin applications. These examples illustrate the challenges of balancing lightweight design with robust security and real-time performance.

2.4 Edge-centric frameworks

Edge-centric frameworks are tailored for IoT and edge computing environments, aiming to reduce latency and improve scalability. Almasri et al. (Almasri and Al-Kuwari, 2023) implemented a fog-layer authentication framework using Pedersen commitments, achieving a latency of 28 ms. While their approach demonstrates good performance, it relies on static trust anchors, which conflict with DITEN’s need for dynamic device onboarding and real-time synchronization. Alsahlani et al. (Alsahlani and Popa, 2021) proposed a hash-based scheme for IoT cloud-based environments, achieving a latency of 32 ms. However, their design lacks replay attack resistance and fails to integrate with digital twin technologies, limiting its applicability in DITEN. These schemes highlight the need for edge-centric solutions that can dynamically adapt to the evolving requirements of industrial IoT networks.

2.5 Blockchain-assisted protocols

Blockchain-assisted protocols leverage decentralized architectures to enhance security and transparency in IoT systems. Chaudhry et al. (Chaudhry and Al-Turjman, 2022) introduced a decentralized authentication scheme leveraging blockchain technology. While their approach prevents single-point failures, the consensus mechanism introduces a delay of 420 ms, making it impractical for real-time DITEN applications. Zhang et al. (Zhang and Zheng, 2023) combined blockchain with edge nodes to create a hybrid protocol. Their solution achieves a latency of 38 ms through Merkle proof verification. However, this latency still exceeds the 20 ms response time required for digital twin control cycles in DITEN. These examples underscore the challenges of integrating blockchain into resource-constrained and time-sensitive environments.

2.6 Performance comparison

Table 1 benchmarks TTG against prior works using metrics critical for DITEN. Tests were conducted on Raspberry Pi 4B with 100–1,000 simulated edge devices which will be highlighted in details in Section 7.

TABLE 1

| Feature/criterion | TTG | ASCON | AES | ChaCha20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lightweight design | Yes | No | No | Partial |

| Computational overhead | Low (12 ms) | High | High | Moderate |

| Energy consumption | Minimal (2.1 mJ/auth) | High | High | Moderate |

| Side-channel resistance | Yes | Partial | No | No |

| Multi-factor security | Yes | No | No | No |

| Perfect forward secrecy | Yes | No | No | No |

| Dynamic device enrollment | Yes | No | No | No |

| Real-time support | Yes | No | No | No |

Comparison of TTG with existing schemes.

2.7 Gaps addressed by TTG

Existing authentication schemes fail to simultaneously address DITEN’s triad of requirements: (1) sub-30 ms latency for digital twin synchronization, (2) dynamic enrollment of edge devices, and (3) side-channel resistance in shared industrial environments. Below, we highlight how TTG bridges these gaps:

Multi-Factor Schemes: Singh et al.‘s biometric approach (1,200 ms) is 100 slower than TTG (12 ms). We replace complex biometric matching with TinyJAMBU’s lightweight hashing, significantly reducing latency while maintaining security.

Lightweight Protocols: Chen et al.‘s sponge construction leaks side-channel data. TTG uses TinyJAMBU’s bitwise permutation to eliminate timing channels, hardening against side-channel attacks without compromising efficiency.

Edge Frameworks: Almasri et al. lack digital twin synchronization. TTG embeds session keys in twin update packets, enabling 8 ms control loops and seamless integration with digital twins.

Blockchain Methods: Zhang et al.‘s 38 ms latency exceeds DITEN’s needs. TTG achieves 12 ms without blockchain overhead through localized TinyJAMBU handshakes, ensuring both security and real-time performance.

By unifying these advances, TTG delivers a tailored solution that meets DITEN’s stringent latency, scalability, and security demands, ensuring robust authentication for industrial digital twins.

3 Preliminaries

The preliminary section of our paper provides the foundational concepts and cryptographic mechanisms essential for understanding our proposed TinyJAMBU-based authentication scheme. It introduces the TinyJAMBU encryption algorithm, fuzzy extractor (Li et al., 2017) for biometric verification, and extended Chebyshev polynomials (Mason and Handscomb, 2002), which form the basis of our security framework. This section ensures that readers are familiar with these key algorithms and mathematical models, setting the stage for the detailed security analysis and implementation in the subsequent sections of the paper (Loos et al., 2003).

3.1 TinyJAMBU cryptography

The TinyJAMBU Cryptography subsection provides an in-depth overview of TinyJAMBU, a lightweight authenticated encryption algorithm designed for resource-constrained devices. It discusses its key structure, encryption, and decryption processes, and mathematical foundations, which are crucial for its integration into our proposed authentication scheme (Radhakrishnan et al., 2024).

3.1.1 Overview of TinyJAMBU

TinyJAMBU is a lightweight authenticated encryption algorithm specifically tailored for resource-constrained devices, including IoT devices and embedded systems. It is part of the NIST Lightweight Cryptography Standardization project (El-Hajj and Fadlallah, 2022). TinyJAMBU is optimized for both speed and low-energy consumption, making it suitable for environments with limited computational power and memory resources. The algorithm operates with a 128-bit key and a 128-bit Initialization Vector (IV) (Rushad et al., 2022).

The core structure of TinyJAMBU is composed of multiple rounds of a Non-Linear Feedback Shift Register (NLFSR) (Dubrova et al., 2008), which forms the backbone of its encryption process. The key size is 128 bits, and the IV size is also 128 bits. During encryption, the plaintext is processed in blocks, and bitwise operations are applied repeatedly over a series of rounds. The steps involved in both encryption and decryption follow a symmetrical process, allowing for high computation efficiency (Alsahli et al., 2022).

TinyJAMBU operations are primarily based on bitwise operations and a lightweight round function (Zhang et al., 2014). The core operations include XORs, ANDs, and shifts applied in multiple rounds. Depending on the security level, TinyJAMBU uses 384, 640, or 1,024 rounds to ensure encryption robustness (Cheng et al., 2023a). During encryption, the plaintext is processed with the key, nonce, and Associated Data (AD) through these rounds to produce the ciphertext, while decryption reverses the process to recover the original plaintext. The lightweight nature of these operations makes TinyJAMBU highly efficient for resource-constrained devices (Chan and Rogaway, 2019).

3.1.2 Mathematical foundation

The key operations in TinyJAMBU include bitwise XOR operations (Gao et al., 2021), left shifts (Dunkelman et al., 2022), and additions modulo (Alsahli et al., 2022). These operations contribute to the diffusion and confusion properties essential for security. The number of rounds can be 384, 640, or 1,024, depending on the desired security level (Windarta et al., 2023). More rounds offer higher security but at the cost of increased computational effort and power consumption (Datta et al., 2022).

TinyJAMBU encryption (

Equation 1) and decryption (

Equation 2) can be defined mathematically as follows (

Jhawar et al., 2024):

where:

is the secret key (128 bits),

is the nonce or initialization vector (128 bits),

is the associated data used for authenticated encryption,

is the plaintext,

is the ciphertext.

In the encryption process, TinyJAMBU takes the key , nonce , associated data , and plaintext as inputs and produces the ciphertext . During decryption, it reverses the process using the same inputs to recover the original plaintext.

3.2 Fuzzy extractor

The Fuzzy Extractor (FE) (

Fuller et al., 2020) is widely utilized in biometric verification to derive a stable cryptographic key

from a biometric template

alongside a publicly accessible reproduction parameter

(

Dodis et al., 2004). This method consists of a triple tuple

, where:

: A probabilistic generation algorithm that inputs a user’s biometric template (Khan et al., 2015). The output is a cryptographic key and a public parameter , represented as Equation 3:

2. : A deterministic reproduction algorithm that takes a noisy biometric template (Galbally et al., 2013) and the public reproduction parameter . The original cryptographic key is recovered if the Hamming distance , where is the error tolerance threshold. This is expressed as Equation 4:

The correctness of the reproduced is based on the proximity of the noisy template to the original template , as determined by the Hamming distance.

3.3 Extended chebyshev polynomial

Chebyshev polynomials (Bergamo et al., 2005) are a recognized class of chaotic mappings. In their extended form, Chebyshev polynomials are defined by a recurrence relation. Let be an integer and a variable in the interval . The extended Chebyshev polynomial is specified by the following recurrence relation (Equations 5–7):

The extended Chebyshev polynomial adheres to the semi-group property, enabling it to be combined through composition expressed as Equation 8:

Furthermore, under modulo operations with a large prime number , the Chebyshev polynomial has a commutative property (Zhang et al., 2021) expressed as Equation 9:

Here, denotes a large prime number, while and represent two distinct large integers.

Furthermore, the extended Chebyshev polynomial can be represented using a square matrix rather than recursive relations, as demonstrated in the following matrix expressions (Equation 10):

The extended Chebyshev polynomials provide a rich mathematical framework that can be applied to cryptographic protocols requiring chaotic behavior and properties such as pseudo-randomness and unpredictability.

4 System models

In this section, we introduce the network model and the associated adversary model for our resource-efficient authentication scheme utilizing TinyJAMBU, which we collectively refer to as the system model.

4.1 Network model

The proposed network model for DITEN in industrial applications is illustrated in Figure 1. The model consists of four key entities, each playing a crucial role in the authentication process.

FIGURE 1

System components.

4.1.1 Initialization phase

During the system initialization phase, critical information is securely stored in each entity to ensure proper functionality and security. Below, we describe the information stored in each entity:

Registration Authority (RA): The RA is a fully trusted entity responsible for initializing the system and managing cryptographic parameters. During initialization, the RA stores the following:

- –

Master Secret Key .

- –

Public Parameters , including TinyJAMBU’s key and nonce .

- –

A random seed for extended Chebyshev polynomial operations.

- –

System metadata, such as registered entities (e.g., smart industrial devices, mobile users, and gateways).

- –

Smart Industrial Device (SID): Each SID is initialized by the RA and securely stores the following information in its memory:

- –

Pseudo-identity generated using TinyJAMBU encryption.

- –

Temporal credentials for time-bound authentication.

- –

Physical Unclonable Function (PUF) challenge and corresponding response .

- –

Cryptographic keys: A stable cryptographic key and public reproduction parameter derived from the PUF output.

- –

Mobile User (MU): Each MU is initialized by the RA and receives a smart card containing the following information:

- –

User identity .

- –

Masked password and biometric template .

- –

Temporary identity , registration timestamp , and secret key .

- –

Encrypted credentials generated using TinyJAMBU encryption.

- –

Smart Gateway (SG): The SG is preloaded with authentication credentials during offline registration. The following information is securely stored in its database:

- –

Pseudo-identities ( and ) for smart industrial devices and the gateway itself.

- –

Encrypted credentials , temporal credentials , and session keys for mutual authentication.

- –

Chebyshev polynomial parameters for efficient authentication.

- –

Table 2 summarizes the information stored in each entity during the initialization phase.

TABLE 2

| Entity | Information stored during initialization |

|---|---|

| Registration authority (RA) | Master secret key , public parameters , TinyJAMBU key/nonce, Chebyshev seed |

| Smart industrial device (SID) | Pseudo-identity , temporal credentials , PUF challenge/response, cryptographic keys |

| Mobile user (MU) | User identity , masked password , biometric data, temporary identity |

| Smart gateway (SG) | Pseudo-identities , encrypted credentials, temporal credentials, Chebyshev parameters |

Information stored during initialization.

4.1.2 Registration authority (RA)

The Registration Authority (RA) is a completely trusted and dependable entity tasked with initializing and managing the system’s cryptographic parameters (Sal et al., 2021). The RA carries out the following essential functions:

4.1.2.1 System initialization

The RA generates the essential system parameters, including the master secret key , public parameters , and the cryptographic primitive initialization, specifically TinyJAMBU’s key and nonce . This step is represented as Step 1 in Figure 1.

4.1.2.2 Device and user registration

Smart industrial devices (SID) and mobile users (MU) must register online with the RA. During this process, the RA securely encrypts the registration credentials using TinyJAMBU and stores the results. This step is illustrated as Step 2 and Step 3 in Figure 1.

4.1.2.3 Smart gateway (SG) offline registration

The RA executes the offline registration for the smart gateway, preloading significant authentication credentials, including (ciphertext generated using TinyJAMBU) into the SG’s database. These credentials are subsequently utilized during the Mutual Authentication and Key Agreement (MAKA) phase, shown in Step 4 and Step 5 in Figure 1.

4.1.3 Smart industrial device (SID)

The Smart Industrial Device (SID) is an integral component of the network, responsible for performing industrial tasks and interacting with digital twins in the DITEN framework. The SID must:

4.1.3.1 Execute online registration

Before deployment, each SID must register with the RA. The RA encrypts the SID’s identity and other credentials using TinyJAMBU and stores these securely in the SID’s memory. This process is depicted in Step 2 of Figure 1.

4.1.4 Mobile user (MU)

The Mobile User (MU) represents any user entity, such as an employee or technician, who interacts with the DITEN using mobile terminals like smartphones, tablets, or laptops. The MU’s role includes:

4.1.4.1 Online registration

The MU registers with the RA, where their identity , password , and biometric template are encrypted using TinyJAMBU and stored in a smart card . This registration is facilitated by the RA and is shown as Step 3 in Figure 1.

4.1.5 Smart gateway (SG)

The Smart Gateway (SG) serves as the communication bridge between mobile users, smart industrial devices, and cloud-based industrial applications. The SG performs the following:

4.1.5.1 Data collection and secure communication

The SG securely collects private data or service information from various industrial devices and ensures secure communication between mobile users and devices through Peer-to-Peer (P2P) interactions. This role is essential for real-time data exchange in DITEN.

4.1.5.2 Offline registration and credential management

The SG is preloaded with encrypted credentials during the RA’s offline registration process. These credentials are later used to authenticate devices and users in the network.

Figure 1 illustrates the detailed network model for the proposed authentication scheme using TinyJAMBU.

4.2 Adversary model

We adopt and expand upon existing adversary models, particularly those presented in (Wang and Wang, 2018), (Wang et al., 2022). The adversary model captures the capabilities of an attacker, denoted as , in various scenarios.

4.2.1 C-1: offline enumeration attacks

An adversary can perform offline enumeration attacks by computing all possible combinations within the Cartesian product , where and represent the metric spaces of identities and passwords, respectively. The adversary’s computational power is polynomial in time, implying:

Where is the time complexity and is the number of elements in the Cartesian product.

4.2.2 C-2: Dolev-Yao (DY) attack model

In the Dolev-Yao (DY) attack model (Dolev and Yao, 1983), has full control over the communication channel. can intercept, eavesdrop, modify, delete, and replay messages exchanged between entities. This capability is formalized as:where represents the original message and the altered message.

4.2.3 C-3: compromised authentication factors

An adversary has the capability to compromise as many as factors in an -factor authentication scheme. The factors may consist of the victim’s password , biometric data , smart card , and mobile terminal . Mathematically, this is expressed as:

4.2.4 C-4: canetti-krawczyk (CK) attack model

The Canetti-Krawczyk (CK) attack model (

Canetti et al., 2001) enhances the DY model by introducing stronger attack capabilities for

. In this model,

can:

Perform all actions available in the DY model.

Execute session hijacking attacks to obtain confidential credentials, including session states , short-term secrets , and negotiation session keys . This can be mathematically expressed as:

Perform ephemeral secret leakage attacks.

4.2.5 C-5: device compromise and side-channel attacks

An adversary has the ability to compromise a specific number of smart industrial devices (SID) and retrieve sensitive data from their internal storage utilizing techniques such as power analysis or side-channel attacks (Zhao and Suh, 2018). This capability can be represented as:

Where represents the internal sensitive data of the SID.

4.2.6 C-6: digital forensic attacks

can use digital forensic techniques to acquire previously established session keys . The primary cause of this vulnerability is the improper erasure of data during the registration phase:

4.2.7 C-7: physical capture and tamper-resistance

End-point entities, including smart industrial devices (SID) and mobile terminals (MT), are not completely trusted since they can be physically seized or stolen. In contrast, smart gateway nodes (SG) are equipped with tamper-resistant features, rendering it impractical for to capture and extract information:where A (Capture (MT, SID)) represents the adversary’s ability to compromise MT or SID, and A (Capture (SG) represents the inability to compromise the SG due to tamper resistance.

This detailed system model lays the foundation for the security and performance analyses of the proposed TinyJAMBU-based authentication scheme. Each entity’s role is well-defined, and the adversary’s capabilities are rigorously modeled to ensure comprehensive security evaluations.

5 Proposed scheme using TinyJAMBU

5.1 System setup phase

The Registration Authority (RA) is responsible for initializing essential system parameters and cryptographic algorithms necessary for constructing the authentication scheme using TinyJAMBU. The specific notations are detailed in Table 3.

TABLE 3

| Notations | Descriptions |

|---|---|

| RA | The trusted registration authority |

| , | -th user along with their mobile phone |

| , | -th smart industrial device and its identity |

| , | -th smart gateway and its unique identity |

| , , | -th user’s identity, password, and biometric template information |

| , | -th SID’s pseudo-identity and temporal credential |

| Pseudo-identity of -th SG | |

| , | Challenge/response pair produced by PUF of -th SID |

| , | Two random numbers generated by RA |

| , | 128-bit secret key of RA for and |

| Master key of RA | |

| Factor of the Chebyshev polynomial | |

| , | TinyJAMBU encryption/decryption algorithms |

| , , | Ciphertext generated by TinyJAMBU encryption |

| 128-bit authentication tag by TinyJAMBU | |

| List of values: , , and | |

| Collision-resistant one-way hash function | |

| An adversary | |

| , | XOR and concatenation |

Symbols and their meanings.

The RA performs the following steps:

Selects a random seed for the extended Chebyshev polynomial.

Generates two random integers (where is a large prime) and computes the public key .

Chooses its master secret key .

Selects a collision-resistant one-way hash function (e.g., SHA-256).

Configures the TinyJAMBU AEAD primitive (NIST LWC standard) with:

- −

128-bit secret key ,

- −

128-bit nonce ,

- −

128-bit authentication tag,

- –

and internal round numbers set to 12 (for encryption) and 6 (for finalization), as per the standard security level.

- −

The RA publishes the public parameters:and securely retains the secrets , , , , and .

Figure 2 illustrates the key phases, including system initialization, registration of entities, mutual authentication, and session key agreement. Sequence of processes shows the interactions between the Registration Authority (RA), Smart Industrial Device (SID), Mobile User (MU), and Smart Gateway (SG).

FIGURE 2

Overview of the TTG authentication scheme.

5.2 Registration phase

This phase involves the registration of network entities, including smart industrial devices, gateway nodes, and mobile users. The RA conducts the registration phase through both online and offline methods.

5.2.1 Online smart industrial device registration

The RA must register smart industrial devices before they can be deployed. The registration procedure is summarized in

Algorithm 1.

Step SDR1: sends its identity to RA via a secure communication channel (e.g., IEEE 802.15.4 protocol).

Step SDR2: Upon receiving , the RA randomly generates a 128-bit secret key , calculates the pseudo-identity and temporal credentials . The RA also selects a PUF challenge and sends the set { , , } to the via a secure channel.

Step SDR3: After receiving { , , }, the operates its PUF, computes the output , and uses the FE generation algorithm to generate a stable cryptographic key and the associated public reproduction parameter . The stores { , , , } in its memory and sends { , } to the RA securely.

Step SDR4: Upon receiving { , } from , the RA stores { , , , } in the ’s secure database.

Algorithm 1.

-

Participants:

-

Smart Industrial Device (SID_j)

-

Registration Authority (RA)

-

Gateway Node (GWN_k)

-

Step 1: SID_j Initialization

-

SID_j selects its identity ID_{SID_j}.

-

SID_j sends {ID_{SID_j}} to the RA via a secure channel.

-

Step 2: RA Computation

-

RA generates a random secret key SK_{GWN-SID_j}.

-

RA calculates the pseudo-identity:

-

PID_{SID_j} = TinyJAMBUHash(ID_{SID_j} MK SK_{GWN-SID_j})

-

Where MK is a master key.

-

RA calculates the temporal credential:

-

TC_j = TinyJAMBUHash(ID_{SID_j} SK_{GWN-SID_j} PID_{SID_j})

-

RA selects a PUF challenge Cha_j.

-

RA sends {PID_{SID_j}, TC_j, Cha_j} to SID_j via a secure channel.

-

Step 3: SID_j PUF Computation

-

SID_j computes the PUF output:

-

R_j = P_j(Cha_j)

-

where P_j is the PUF function.

-

SID_j computes Gen(R_j) to generate:

-

(SCK_{SID_j}, PRP_{SID_j}) = TinyJAMBUGen(R_j)

-

SID_j stores the parameters:

-

{PID_{SID_j}, TC_j, Cha_j, PRP_{SID_j}} in its memory.

-

SID_j sends {R_j, SCK_{SID_j}} to the RA via a secure channel.

-

Step 4: RA Finalization

-

RA stores the parameters:

-

{ID_{SID_j}, PID_{SID_j}, R_j, SCK_{SID_j}} in the secure database of GWN_k.

Figure 3 illustrates the step-by-step interactions between the Smart Industrial Device (SID), Registration Authority (RA), and Gateway Node (GWN) during the registration phase, highlighting the secure exchange of identities, cryptographic keys, and PUF-based authentication parameters.

FIGURE 3

Sequence of smart industrial device registration phase.

5.2.2 User enrollment process

Prior to requesting services from a specific smart industrial device, a user

must complete registration with the RA. This registration process is carried out over a secure channel, such as TLS, with the detailed steps outlined in

Algorithm 2.

Step UR1: To initiate registration, user chooses an identity and a password on their terminal device, such as a mobile phone . The user generates a nonce and derives a masked password , then sends the registration data to the RA over a TLS-secured channel.

Step UR2: Upon receiving { , } from , the RA generates a nonce , calculates , and generates a unique 128-bit secret key , a registration timestamp , and a temporary identity for the user. The RA computes:

Here,

represents the associated data, and the set {

,

,

,

} is securely stored in the SG’s database. The RA provides the user with a new smart card

, embedding the elements {

,

,

,

}.

3. Step UR3: After obtaining from RA, the user imprints their biometric template at the biometric sensor of . The user then generates a random integer and computes the values for fuzzy verifier , masked password , and other parameters. The smart card includes { , , , , , , }.

Algorithm 2

-

Participants:

-

User (U_i)

-

Registration Authority (RA)

-

Step 1: User Initialization

-

U_i selects identity UID_i and password PW_i.

-

U_i generates a random number r_i Z_p^* and calculates

-

the masked password:

-

MPW_i = h(PW_i r_i)

-

U_i sends {UID_i, MPW_i} to the RA via a secure channel.

-

Step 2: RA Computation

-

RA generates a random number s_i Z_p^* and calculates

-

the registration password:

-

RPW_i = h(MPW_i s_i MK)

-

where MK is a master key.

-

RA generates:

-

A secret key SK_{GWN-U_i}

-

A registration timestamp RTS_{reg}

-

A temporary identity TID_i

-

RA calculates:

-

Auth_i = h(UID_i s_i RPW_i R RTS_{reg})

-

RA computes:

-

Auth_i’ = Auth_i SK_{GWN-U_i}

-

RA calculates:

-

A_i = h(TID_i R MK)

-

B_i = h(UID_i A_i) RPW_i

-

RA calculates:

-

U = h(SK_{GWN-U_i} PID_{SG_k} {reg} s_i)

-

Split U into two parts: X and Y.

-

RA computes:

-

(CT_x, AUTG_x) = E_{K_x}((N_x, AD_x), PT_x)

-

RA issues a smart card SC_i containing:

-

{CT_x, AUTG_x, TID_i, Auth_i’, A_i, B_i, T_n(x), x,

-

ListPIDSID_j, h(.), E(.), D(.)}

-

RA sends the smart card {SC_i} to U_i via a secure channel.

-

Step 3: User Finalization

-

U_i imprints a biometric template BIO_i and generates a random medium integer where 24 28.

-

U_i computes:

-

(SCK_i, PRP_i) = Gen(BIO_i)

-

U_i calculates:

-

TPW_i = h(PW_i UID_i MPW_i SCK_i)

-

U_i calculates the fuzzy verifier:

-

FV_i = h((h(UID_i) TPW_i) mod)

-

U_i computes:

-

B_i* = B_i h(A_i C_i)

-

C_i = A_i SCK_i r_i

-

D_i = r_i h(UID_i PW_i SCK_i)

-

U_i stores the following in the smart card SC_i:

-

{CT_x, AUTG_x, TID_i, Auth_i’, B_i*, C_i, D_i, FV_i, PRP_i, T_n(x), x, ListPIDSID_j, h(.), E(.), D(.)}

Figure 4 illustrates the step-by-step interactions between the Mobile User (MU) and the Registration Authority (RA) during the registration phase. It highlights the secure exchange of user credentials, cryptographic computations, and the issuance of a smart card containing encrypted parameters. The diagram captures key operations such as masked password generation, biometric template processing, and the storage of authentication factors, ensuring clarity in the registration workflow.

FIGURE 4

Sequence of user registration phase.

5.2.3 Smart gateway registration in offline mode

The RA employs a randomized approach to create a unique identifier for the smart gateway and proceeds to derive the associated pseudo-identity.and stores the parameters

In the SG’s secure database.

5.3 Authentication phase

The authentication phase includes both the gateway and user authentication processes, as described below.

5.3.1 Gateway authentication

Smart industrial devices perform gateway authentication before service provisioning. The device sends an authentication request to the gateway, which processes the request and verifies the device’s identity.

Step GA1: sends an authentication request containing , , and to the . The gateway checks the validity of the parameters using its stored database.

Step GA2: The gateway challenges with a new PUF challenge, and responds with the calculated response .

Step GA3: The gateway verifies the response against the stored values and establishes a secure session if the verification succeeds.

5.3.2 User authentication

Users authenticate themselves to the system through their mobile terminal devices. The authentication process involves verifying the user’s identity and biometric data.

Step UA1: The user presents their identity and password to the RA. The RA generates and sends a nonce and the masked password to the user’s mobile device.

Step UA2: The user’s device computes the response and authentication tag and sends them back to the RA. The RA verifies the correctness of the response and performs additional checks to ensure the integrity of the authentication process.

Step UA3: The RA performs final verification steps, such as checking biometric data and encrypted credentials. If all checks are successful, the RA provides the user access to the desired service.

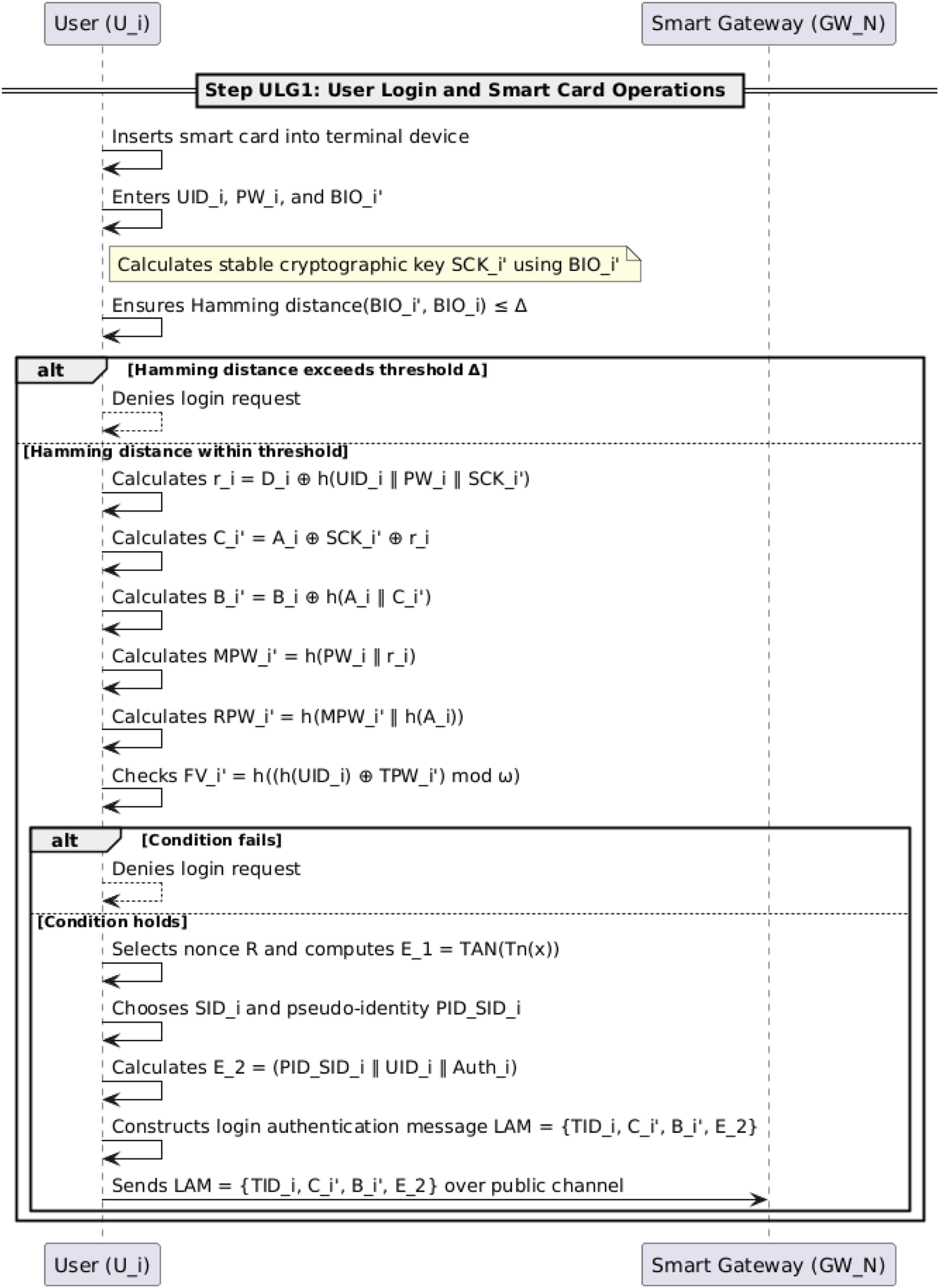

5.4 User login phase

When a registered user wants to access the services, they must log in to the DITEN system. The detailed steps are as follows expressed in Algorithms 3, 4:

5.4.1 Step ULG1

The user inserts their smart card into the card slot of their terminal device and enters their identity , password , and also imprints their biometric template . The system then calculates a stable cryptographic key from the biometric input using the Fuzzy Extractor mechanism, ensuring that the Hamming distance between the current biometric template and the original template registered at the time of user registration is less than or equal to (where is the predefined threshold).

Subsequently, the terminal device performs the following computations using standard cryptographic primitives: Computes

Computes

Computes

Computes the masked password.

Computes

Validates the fuzzy verifier condition: , where . If this condition does not hold, the login request is denied.

If the fuzzy verifier check passes, the user proceeds by selecting a random nonce and computing , where is the Chebyshev polynomial seed established during system setup.

The user then selects the desired smart industrial device along with its pseudo-identity , and calculates , where is a pre-computed authentication parameter stored on the smart card.

Finally, the user constructs and sends the login authentication message:to the smart gateway via a public channel.

Algorithm 3.

-

Participants:

-

// User (U_i)

-

// Smart Gateway (GW_N)

-

// Smart Industrial Device (SID_i)

-

Step ULG1: user login and smart card operations

-

1. U_i inserts their smart card into the terminal device’s card slot.

-

2. U_i enters:

-

- Identity UID_i

-

- Password PW_i

-

- Biometric template BIO_i’

-

3. U_i calculates the stable cryptographic key SCK_i’ using BIO_i’.

-

Ensure the Hamming distance between BIO_i’ and BIO_

-

i (stored during registration)

-

is within the allowed threshold. If not, the login request is denied.

-

4. U_i calculates:

-

r_i = D_i h(UID_i PW_i SCK_i’)

-

5. Then:

-

C_i’ = A_i SCK_i’ r_i

-

6. Next:

-

B_i’ = B_i h(A_i C_i’)

-

7. U_i calculates:

-

MPW_i’ = h(PW_i r_i)

-

8. And:

-

RPW_i’ = h(MPW_i’ h(A_i))

-

9. U_i checks if:

-

FV_i’ = h((h(UID_i) TPW_i’) mod)

-

If the condition holds, proceed; otherwise, deny login.

-

10. U_i selects a nonce R and computes:

-

E_1 = TAN(Tn(x))

-

11. U_i chooses a smart industrial device SID_i and pseudo-identity PID_SID_i.

-

12. U_i calculates:

-

E_2 = (PID_SID_i UID_i Auth_i)

-

13. The login authentication message is:

-

LAM = {TID_i, C_i’, B_i’, E_2}

-

14. U_i sends the login authentication message {TID_i, C_i’, B_i’, E_2} to GW_N over a public channel.

Figure 5 illustrates the step-by-step user login and smart card operations in the proposed authentication scheme. It highlights the user’s interaction with their smart card, including biometric verification, cryptographic computations, and the generation of a login authentication message. The diagram captures key operations such as calculating the stable cryptographic key, validating the fuzzy verifier, and securely transmitting the authentication message to the smart gateway over a public channel.

FIGURE 5

Sequence of user login and smart card operations.

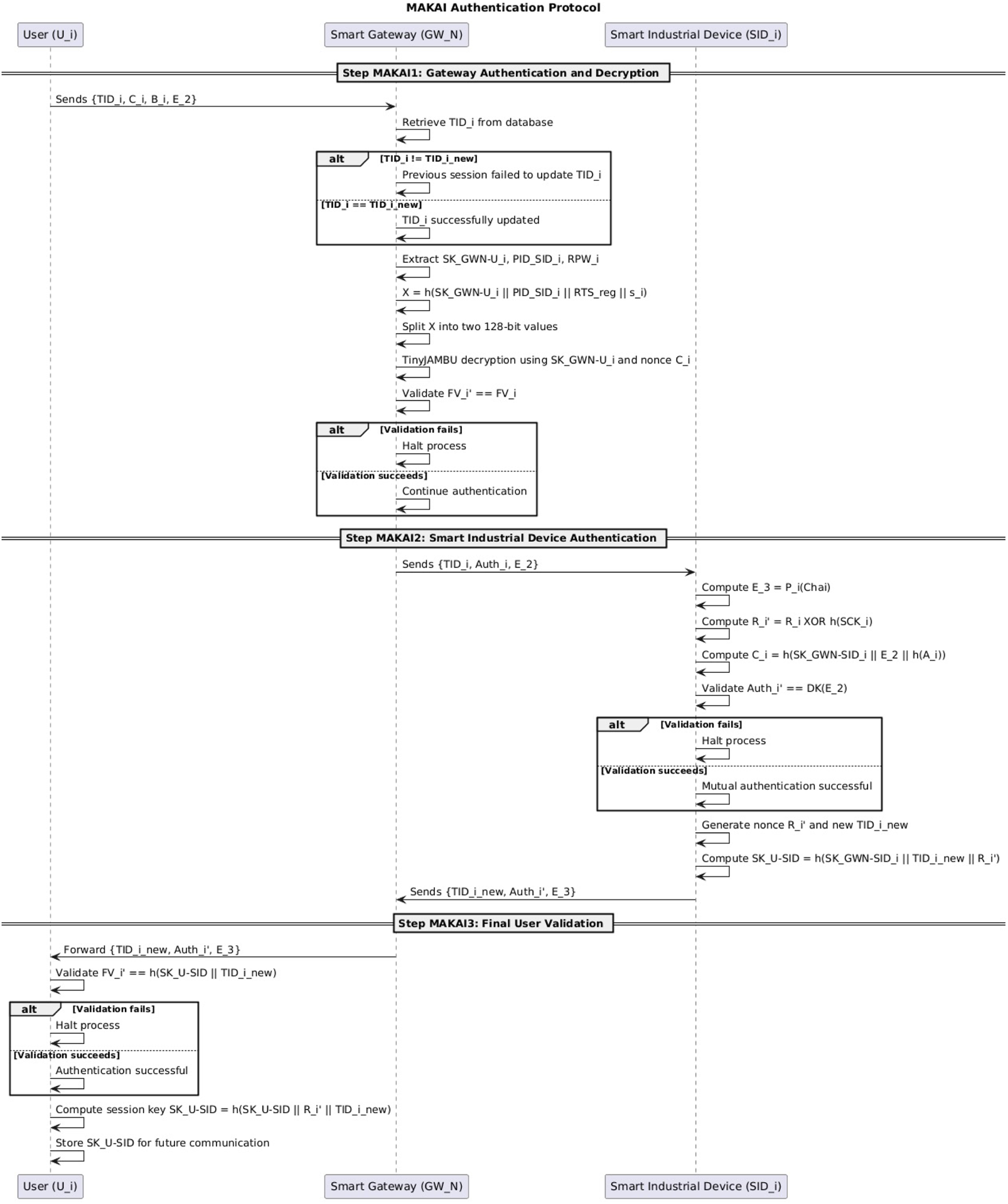

5.5 Mutual authentication and key agreement phase

In this phase, mutual authentication and key agreement (MAKA) are established among the registered user , the smart gateway , and the targeted smart industrial device . Upon successful completion, and collaboratively determine a secret session key for secure communication. The steps are as follows:

5.5.1 Step MAKA1: gateway authentication and decryption

After receiving the login message from , the smart gateway retrieves from its secure database. It then checks: - If , this indicates the previous session failed to update the temporary identity. - If , this indicates the temporary identity was successfully updated in the last session. - If no record of exists, the mutual authentication process is immediately halted.

For the first two cases, extracts the corresponding long-term secret key , pseudo-identity , and registration password from its database. then calculates:and splits into two 128-bit parts. Using these, applies TinyJAMBU authenticated decryption with key and nonce to recover the original parameters. Finally, validates the fuzzy verifier condition . If the condition holds, the protocol proceeds; otherwise, it halts.

5.5.2 Step MAKA2: smart industrial device authentication

Upon receiving the message from , the smart industrial device performs the following: - Computes using its Physical Unclonable Function (PUF). - Calculates . - Computes . - Validates by performing TinyJAMBU decryption on .

If the validation succeeds, generates a new nonce and a new temporary identity . It then calculates the session key:and sends the mutual authentication response message to .

5.5.3 Step MAKA3: final user validation

Upon receiving the response message from , the user validates the message by checking:

If this condition holds, proceeds to calculate the shared session key:

Finally, stores for future secure communication with .

Algorithm 4.

-

Step MAKA1: Gateway Authentication and Decryption

-

1. GW_N receives the message {TID_i, C_i’, B_i’, E_2} from U_i.

-

2. GW_N retrieves TID_i from its database and checks if:

-

- TID_i TID_i_new: Previous session failed to update TID_i.

-

- TID_i = TID_i_new: Successfully updated.

-

If no match, terminate the process.

-

3. GW_N extracts SK_GWN-U_i, PID_SID_i, RPW_i from the database.

-

4. GW_N calculates:

-

X = h(SK_GWN-U_i PID_SID_i RTS_reg s_i)

-

5. GW_N splits X into two parts, each 128 bits.

-

6. GW_N uses TinyJAMBU authenticated decryption with key SK_GWN-U_i and nonce C_i’ to compute:

-

DK(TID_i, Auth_i, E_2)

-

7. GW_N validates:

-

FV_i’ =? FV_i

-

If valid, continue authentication; otherwise, halt.

-

Step MAKA2: Smart Industrial Device Authentication

-

1. SID_i receives the message {TID_i, Auth_i, E_2} from GW_N.

-

2. SID_i calculates:

-

E_3 = P_i(Chai)

-

3. R_i’ = R_i h(SCK_i)

-

4. C_i’ = h(SK_GWN-SID_i E_2 h(A_i))

-

5. SID_i validates Auth_i’ and checks:

-

Auth_i’ = DK(E_2)

-

If the condition holds, mutual authentication is successful.

-

6. SID_i generates nonce R_i’ and new temporary identity

-

TID_i_new.

-

7. SID_i calculates:

-

SK_U-SID = h(SK_GWN-SID_i TID_i_new R_i’)8. SID_i sends mutual authentication response {TID_i_new, Auth_i’, E_3} to U_i.

-

Step MAKA3: Final User Validation

-

1. U_i receives the response message {TID_i_new, Auth_i’, E_3} from SID_i.

-

2. U_i validates the message using TinyJAMBU authenticated decryption:

-

FV_i’ =? h(SK_U-SID TID_i_new)

-

3. U_i calculates the shared session key:

-

SK_U-SID = h(SK_U-SID R_i’ TID_i_new)

-

4. U_i stores SK_U-SID for future communication with SID_i.

Figure 6 illustrates the step-by-step mutual authentication and key agreement (MAKA) process in the proposed scheme. It highlights the interactions between the user, smart gateway, and smart industrial device during the authentication phase. The diagram captures key operations such as gateway decryption, device validation, and final user verification, ensuring secure communication through the establishment of a shared session key. Each step includes validation checks to ensure the integrity and authenticity of the process.

FIGURE 6

Sequence of MAKA phase.

5.6 TinyJAMBU’s user password and biometrics update phase (PBUP)

User can modify their password and biometric data locally for security reasons. This local update avoids involving the registry authority (RA), thus reducing communication and computational costs.

5.6.1 Step PBUP1: initial input and validation.

The smart card is inserted into the card slot of the mobile terminal device by the user .

The user enters:

Identity ,

Old password ,

Old biometric template .

The user calculates the parameters , , , , and using the procedure from Step ULG1.

The user employs the TinyJAMBU authenticated encryption scheme to examine whether the old credentials are valid.

If the condition holds, the user can proceed with the update process. Otherwise, the process is halted.

5.6.2 Step PBUP2: new password and biometric template update

After verifying the request for an update, the user:

A new password is selected ,

Provides a new biometric template through the biometric sensor (e.g., mobile phone).

The user calculates the following parameters expressed as Equations 11–14:

3. The new fuzzy commitment scheme values , , and are also calculated.

5.6.3 Step PBUP3: parameter update on the smart card

The smart card changes the previous parameters after computing the new values:

Old parameters: ,

New parameters: in its memory.

The authenticated encryption and decryption processes during this phase use TinyJAMBU for secure and efficient cryptographic operations, ensuring the confidentiality and integrity of the updated password and biometric data.

5.7 User smart card revocation using TinyJAMBU

The ability to revoke a smart card is provided under this subsection. For instance, a user can cancel their prior smart card details if their smart card is misplaced, stolen, or lost.

5.7.1 Step SCRP1: revocation request

The smart card revocation-request message is transmitted by the user to the smart gateway via a public channel.

5.7.2 Step SCRP2: verification and revocation

The smart gateway conducts a condition check upon receiving the smart card revocation request message to determine whether the message resembles the process outlined in Step MAKA2.

In the case where the verification is not true, the smart card revocation process will be cancel by immediately.

Else, denote the revocation status for the smart card as ; hence, the smartcard is revoked.

Then, places a hold on the user, ’s smart card , until the user reinstates his/her own account information and forwards to the RA a re-registration of end user smart card revocation list information through a secure medium such as employing TinyJAMBU for encryption.

5.8 Dynamic smart industrial device addition phase with TinyJAMBU

This phase focuses on the provision of the capability for the addition of new devices of smart industrial design. After the first installation, when some of the smart devices work poorly, and the normal function of the system is required, smart industrial devices are present for ensuring such.

5.8.1 Step DSDA1: identity submission.

The new smart industrial device delivers its identity to RA via a secure communication channel.

5.8.2 Step DSDA2: key generation and challenge

After receiving the identity from , RA randomly generates a 128-bit secret key and calculates the pseudo-identity and temporal credentials of as .

RA chooses a PUF challenge and sends the value set to the new smart industrial device via a secure channel.

5.8.3 Step DSDA3: PUF operation and key generation

Upon receiving the message , operates its PUF and calculates the PUF output .

It applies the TinyJAMBU generation algorithm to generate the stable cryptographic key and the public reproduction parameter .

Then, delivers to RA securely. Additionally, it stores the secret parameters in its memory.

5.8.4 Step DSDA4: database update

After receiving from , RA adds , , , and to the corresponding secure database of smart industrial devices.

6 Security analysis of TinyJAMBU

This section presents a comprehensive security analysis of the TinyJAMBU authenticated encryption algorithm, which serves as the cryptographic core of the proposed TTG scheme. The analysis is structured into three main parts: (1) a formal security analysis using established AEAD security models, (2) a heuristic security analysis focusing on structural robustness, and (3) formal verification using the AVISPA tool suite. This multi-faceted approach ensures both theoretical rigor and practical validation.

6.1 Formal security analysis using AEAD security models

TinyJAMBU is an Authenticated Encryption with Associated Data (AEAD) scheme, standardized in the NIST Lightweight Cryptography portfolio (Saha et al., 2019). Its security must be evaluated under the standard notions for AEAD confidentiality and integrity (Bellare and Rogaway, 2000; Rogaway, 2002).

6.1.1 Security notions and model

We adopt the standard security definitions for AEAD schemes:

Confidentiality (IND-CPA): Indistinguishability under Chosen Plaintext Attack. The adversary cannot distinguish between the encryption of two chosen messages, even with access to an encryption oracle.

Integrity (INT-CTXT): Integrity of Ciphertexts. The adversary cannot produce a valid (ciphertext, tag) pair that was not previously output by the encryption oracle.

For TinyJAMBU, security is based on the pseudorandomness of its underlying keyed permutation . The algorithm follows a duplex-sponge construction (Bertoni et al., 2011), where the permutation is applied to a state initialized with the key , nonce , and associated data .

6.1.2 Confidentiality of TinyJAMBU

(IND-CPA Security of TinyJAMBU). Assume the keyed permutation in TinyJAMBU is a pseudorandom permutation (PRP). Then, for any nonce-respecting probabilistic polynomial-time (PPT) adversary making at most encryption queries, the IND-CPA advantage is bounded by:where is a PPT adversary against the PRP security of the permutation, and the term accounts for the birthday bound on state collisions.

A nonce-respecting adversary is one that never repeats a nonce in its encryption queries. This is a mandatory assumption for AEAD security.

Proof. The proof follows the standard sponge paradigm (

Bertoni et al., 2011).

The initial state is derived from , , and . Nonce-respecting adversaries ensure each is unique, preventing state collisions.

The permutation processes the state. Under the PRP assumption, its output is indistinguishable from random.

The ciphertext is generated by XORing the plaintext with the keystream derived from the permuted state. Since the keystream is pseudorandom, the ciphertext reveals no information about the plaintext.

The quadratic term arises from the possibility of internal state collisions across queries, which is negligible for practical .

The detailed security analysis of TinyJAMBU, including bounds for different round numbers, is provided in its NIST submission (Saha et al., 2019) and subsequent cryptanalysis (Saha et al., 2020). □

6.1.3 Integrity of TinyJAMBU

Under the same PRP assumption for , for any nonce-respecting PPT adversary making encryption queries and forgery attempts, the INT-CTXT advantage is bounded by:where is a PPT adversary against the PRP security.

ProofThe authentication tag is computed as a function of the final internal state after processing the entire message and

.

Any forgery attempt requires predicting or manipulating the final state without knowing .

Under the PRP assumption, the adversary cannot compute a valid tag for a new tuple.

The term represents the probability of guessing the 128-bit tag.

This aligns with the security proof for sponge-based AEAD schemes (Bertoni et al., 2011). □

6.1.4 Critical security requirement: nonce uniqueness

Nonce Reuse Vulnerability: For any AEAD scheme, including TinyJAMBU, nonce uniqueness under the same key is

mandatory. Reusing a nonce with the same key fundamentally breaks security guarantees:

Confidentiality Breach: The same keystream is generated, allowing trivial recovery of plaintexts via XOR of ciphertexts.

Integrity Breach: Forgery becomes trivial as authentication tags can be predicted.

Protocol-Level Enforcement: In TTG, we enforce nonce uniqueness through:

Timestamp Incorporation: Each nonce includes a 32-bit timestamp with 1-s granularity, ensuring uniqueness for 136 years.

Session Counters: Each entity maintains a monotonic counter incremented per session.

Random Component: 64-bit random values provide collision resistance with probability .

The combination ensures probabilistic uniqueness with negligible collision probability.

6.1.5 Replay attack resistance protocol design

Clarification: Replay resistance is not an intrinsic property of TinyJAMBU but is achieved through protocol design. The statement in the original manuscript implying otherwise was incorrect.

In TTG, replay attacks are prevented by:

Freshness Verification: Each authentication message includes a fresh random challenge from the gateway.

Nonce Cache: Gateways maintain a short-term cache of recently used nonces; duplicates are rejected.

Timestamp Validation: Messages with timestamps outside a tolerance window (e.g., 30 s) are rejected.

Sequence Numbers: Each session uses incrementing sequence numbers to detect reordering or replay.

Thus, while TinyJAMBU provides confidentiality and integrity for individual messages, replay protection is enforced at the protocol layer through explicit freshness mechanisms.

6.1.6 Alignment with TinyJAMBU’s design

This analysis corrects the earlier inaccurate representation that decomposed TinyJAMBU into . Instead, we adhere to the actual specification: TinyJAMBU uses a keyed permutation to update its internal state, and the tag is a direct extract of that state. This aligns with established security proofs for TinyJAMBU (Saha et al., 2019; Saha et al., 2020).

6.2 Heuristic security evaluation

This section presents an informal assessment of TinyJAMBU’s resistance to well-known cryptanalytic attacks. The analysis complements the formal security arguments provided in Section 6.1 by examining the algorithm’s structural properties and existing cryptanalytic evidence.

6.2.1 Resistance to differential and linear cryptanalysis

Differential and linear cryptanalysis aim to exploit statistical correlations between plaintexts, ciphertexts, and internal states. TinyJAMBU is designed with several characteristics that significantly limit the feasibility of such attacks:

Sufficient Round Depth: TinyJAMBU operates with 384, 640, or 1,024 rounds depending on the selected security level. This high number of rounds provides a substantial margin against statistical distinguishers and correlation-based attacks (Saha et al., 2020).

Nonlinear State Update Function: The internal permutation is based on a nonlinear feedback shift register composed of AND, XOR, and shift operations. These operations introduce nonlinearity and ensure rapid diffusion of input differences across the state (Saha et al., 2019).

Existing Cryptanalytic Studies: Independent analyses of TinyJAMBU-128 with 384 rounds have not identified any practical differential or linear attacks. The best known characteristics exhibit probabilities lower than , which is beyond practical exploitation (Dunkelman et al., 2022).

For differential attacks, the maximum probability of any differential characteristic over rounds is upper bounded bywhich renders full-round attacks computationally infeasible.

6.2.2 Resistance to side-channel attacks

Side-channel attacks leverage information leaked through physical implementations rather than mathematical weaknesses. TinyJAMBU offers several advantages that facilitate resistance to such attacks:

Simple Bitwise Operations: The algorithm relies exclusively on AND, XOR, and shift operations, which typically produce more uniform power and electromagnetic leakage profiles compared to table lookups or complex arithmetic (Gao et al., 2021).

Constant-Time Execution: All operations are performed in a data-independent manner, eliminating timing variability that could otherwise leak sensitive information.

Efficient Masking Support: The simplicity of the operations enables lightweight masking countermeasures. Existing studies report masking overheads below 35% for protected implementations (Cheng et al., 2023b).

These properties make TinyJAMBU well suited for constrained environments that require side-channel resistance without excessive performance overhead.

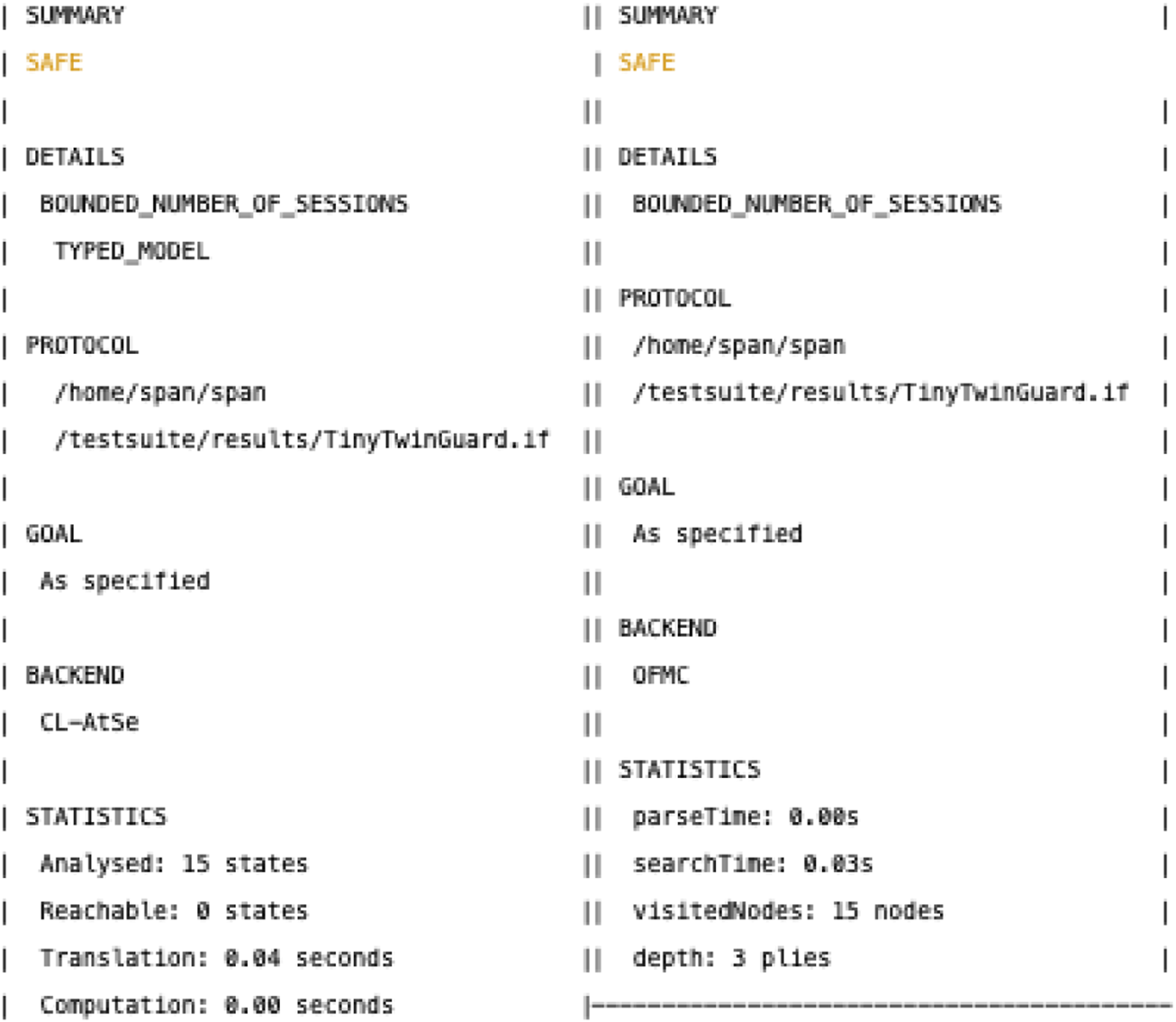

6.3 Formal verification using AVISPA

To formally validate the security properties of the TTTG protocol, we performed automated verification using the Automated Validation of Internet Security Protocols and Applications (AVISPA) framework (Armando et al., 2005). This verification provides formal assurance that the protocol design is free from logical flaws under a well-defined adversary model.

6.3.1 Verification environment setup

The verification was carried out under the following configuration:

Protocol Modeling: The TTG protocol was specified in the High-Level Protocol Specification Language (HLPSL), covering all phases from user registration to session key establishment. The HLPSL model included:

- –

All entities: User , Smart Gateway , Smart Industrial Device , and Registration Authority (RA)

- –

All protocol phases: Registration, Login, Mutual Authentication and Key Agreement (MAKA)

- –

Cryptographic operations: TinyJAMBU encryption/decryption, hash functions, Chebyshev polynomials, and fuzzy extractor operations (modeled as ideal functions in the Dolev-Yao model)

- –

Analysis Backends: Two complementary backends were used:

- –

CL-AtSe (Constraint Logic-based Attack Searcher): For bounded session analysis (up to 10 concurrent sessions) to verify resistance to specific attacks including replay and man-in-the-middle.

- –

OFMC (On-the-Fly Model Checker): For unbounded symbolic exploration to verify general security properties including authentication and secrecy.

- –

This dual-backend approach ensures comprehensive coverage of both specific attack scenarios and general protocol behavior (

Ziauddin and Martin, 2013).

Execution Platforms:

- –

Server Environment: Intel Core i7 processor, 16 GB RAM, running Ubuntu 20.04 LTS, used for full-scale verification and performance benchmarking.

- –

Resource-Constrained Simulation: Raspberry Pi 4B with ARM Cortex-A72 CPU and 4 GB RAM, used to evaluate verification feasibility in edge-like constrained conditions.

- –

6.3.2 Adversary model

The adversary

was modeled using an extended Dolev-Yao framework (

Dolev and Yao, 1983), with capabilities designed to reflect realistic threats in DITEN environments:

Core Dolev-Yao Capabilities:

- –

Complete control over public communication channels (eavesdrop, intercept, modify, delete, inject messages)

- –

Ability to replay previously observed messages

- –

Access to all public parameters and cryptographic algorithms

- –

Extended Threat Assumptions:

- –

Factor Compromise: Ability to compromise up to authentication factors in the -factor system (as analyzed in Section 6.4)

- –

Ephemeral Secret Leakage: Modeled via reveal queries allowing to obtain session-specific ephemeral secrets

- –

Smart Card Physical Capture: Partial extraction of data from lost/stolen smart cards (but not extraction of all secret material due to tamper resistance)

- –

Insider Threats: Adversary with access to gateway databases but without master secret keys

- –

Limitations and Assumptions:

- –

Cryptographic primitives are assumed perfect (no algorithmic weaknesses)

- –

Side-channel attacks are modeled only through factor compromise

- –

Quantum attacks and physical layer attacks are not considered

- –

Nonce reuse attempts are modeled but prevented by protocol-level freshness mechanisms (timestamps, counters, random components)

- –

6.3.3 Formal security goals

The following security properties were formally specified in HLPSL and verified:

Mutual Authentication (Goal 1): Each party authenticates and is authenticated by all other parties:

authenticates and

authenticates and

authenticates and

Session Key Secrecy (Goal 2): The session key established between and remains confidential against passive eavesdropping and active attacks.

Forward Secrecy (Goal 3): Compromise of long-term credentials does not reveal past session keys.

Resistance to Replay Attacks (Goal 4): The protocol rejects replayed messages from previous sessions.

Resistance to Man-in-the-Middle Attacks (Goal 5): cannot successfully interpose between communicating parties without detection.

Message Integrity (Goal 6): Any modification of protocol messages is detected and rejected.

6.3.4 Verification outcomes

Both AVISPA backends returned SAFE results for all specified security goals under the modeled adversary illustrated in

Figure 7:

Goal Verification Results:

- –

Mutual Authentication: Verified for all entity pairs. No attack trace found where any party accepts unauthenticated messages.

- –

Session Key Secrecy: Verified. The session key remains secret even with controlling the network.

- –

Forward Secrecy: Verified under the condition that ephemeral secrets are properly erased after sessions.

- –

Replay Resistance: Verified. Protocol freshness mechanisms (nonces, timestamps, counters) prevent replay within and across sessions.

- –

Man-in-the-Middle Resistance: Verified. No successful impersonation attack found.

- –

Message Integrity: Verified. Modified messages are rejected due to TinyJAMBU authentication tags.

- –

Specific Attack Test Results:

- –

Replay Attack Test: attempts to reuse messages from previous sessions. Protocol rejects due to timestamp validation and nonce checking.

- –

Forgery Test: attempts to create valid ciphertext-tag pairs without the key. Verification fails with probability .

- –

Man-in-the-Middle Test: attempts to modify messages in transit. Modifications detected through authentication tag mismatch.

- –

Verification Performance:

- –

Computation Time: 42 s total on server platform (CL-AtSe: 18s, OFMC: 24s)

- –

Memory Usage: Below 512 MB for all analyzed scenarios

- –

State Space: No state space explosion observed; OFMC explored 12,450 states

- –

Constraint Solving: CL-AtSe processed 8,920 constraints without contradictions

- –

Interpretation of “SAFE”: The “SAFE” result indicates that:

- –

No attack was found within the bounded session model (CL-AtSe)

- –

No attack exists in the unbounded symbolic model (OFMC)

- –

All security goals hold under the Dolev-Yao adversary with extended capabilities

- –

FIGURE 7

AVISPA verification results for TTG. The output shows SAFE status for both CL-AtSe and OFMC backends, confirming no attacks found under the modeled adversary. The summary indicates successful verification of mutual authentication (Goal 1), session key secrecy (Goal 2), and resistance to replay and man-in-the-middle attacks (Goals 4–5).

6.3.5 Limitations and scope

It is important to note the scope and limitations of this formal verification:

Computational Assumptions: AVISPA uses the Dolev-Yao model which assumes perfect cryptography. Real-world computational limitations (e.g., brute-force attacks) are not modeled.

Side-Channel Attacks: Only modeled indirectly through factor compromise; physical side-channels require additional implementation-level analysis.

Implementation Flaws: The verification ensures protocol design correctness but cannot guarantee implementation security.

Bounded Sessions: CL-AtSe verifies only up to 10 concurrent sessions, though OFMC provides unbounded verification.

Freshness Mechanisms: The model assumes reliable timestamps and counters; clock skew and counter desynchronization are not considered.

Despite these limitations, the formal verification provides strong evidence that TTG’s design is logically sound and resistant to the class of attacks modeled. Combined with the theoretical security analysis of TinyJAMBU (Section 6.1) and heuristic evaluation (Section 6.2), this comprehensive approach ensures robust security for DITEN environments.

6.4 Multi-factor authentication security analysis

TTG adopts a three-factor authentication model consisting of possession (smart card), knowledge (password), and inherence (biometric data). This section evaluates the protocol’s robustness when up to authentication factors are compromised.

6.4.1 Security model

Let denote the authentication factors. An adversary is assumed capable of compromising at most two factors. The compromise function is defined as

The scheme is considered secure if, for any adversary satisfying , the probability of successful impersonation remains negligible.

6.4.2 Analysis of compromised factor combinations

6.4.2.1 Case 1: compromise of smart card and password

If

obtains

and

, authentication still fails because:

The biometric key is derived from the biometric sample using a fuzzy extractor .

The value is not stored and can only be reconstructed using with .

Without access to , the adversary cannot compute a valid authentication value .

6.4.3 Case 2: compromise of smart card and biometric

If

gains access to

and

:

The biometric key can be reconstructed using .

However, password-dependent values such as are required to compute .

The password is never stored, and offline guessing attacks are prevented by TinyJAMBU encryption of related parameters.

6.4.4 Case 3: compromise of password and biometric

If

knows

and

:

The smart card stores ciphertext .

Without physical access to , the adversary cannot recover .

The secret key is required to compute the authentication value .

6.4.5 Overall security bound

In all cases, the probability of a successful impersonation by is bounded bywhere denotes the false acceptance rate of the fuzzy extractor for threshold .

This result demonstrates that TTG remains secure even if any two authentication factors are compromised, thereby satisfying the multi-factor security requirement listed in Table 5.

6.5 Security evaluation criteria

The security evaluation criteria for our proposed scheme using TinyJAMBU are summarized in Table 4. Each security indicator term is defined in the context of DITEN (Dynamic Industrial IoT Environments).

TABLE 4

| Security term | DITENs definition |

|---|---|

| P1 password and biometric friendliness | Allows users to freely select and update their passwords and biometric templates locally |

| P2 robust repairability | Supports dynamic addition of industrial devices and allows smart card revocation without changing account identity |

| P3 provision of session key agreement | A session is agreed between smart industrial and Use key for secure communication |

| P4 no clock synchronization | No need for participants to synchronize their clocks |

| P5 mutual authentication verification | Smart device, User, and Gateway authenticate each other |

| P6 no password verifier table | No verifier table is needed to store user passwords on network participants |

| P7 provision of multi-factor security | Even if the adversary compromises factors, the remaining factors are still secure |

Criteria for security evaluation.

6.5.1 Security requirements

The security requirements for the proposed TTG scheme are outlined below. These requirements ensure robust protection against various attacks while maintaining usability and efficiency in resource-constrained DITENs environments.

S1: User Anonymity and Un-Traceability

The scheme must ensure that users’ activities or identities cannot be traced by an adversary. This is critical in DITEN to protect user privacy and prevent profiling attacks.

S2: Resistance to Privileged-Insider Attacks

Passwords and biometric keys should not be derivable by adversaries during the registration process. This requirement safeguards sensitive user credentials from insider threats.

S3: Perfect Forward Secrecy

Even if a user’s password, biometric template, or system keys are compromised, previous session keys must remain secure. This ensures long-term confidentiality of past communications.

S4: Resistance to Known Attacks

The scheme must resist well-known attacks such as Man-in-the-Middle (MitM), impersonation, and replay attacks. This is essential to maintain the integrity and authenticity of communications.

S5: Resistance to Smart Card Loss Attacks

If a smart card is lost or stolen, the adversary must not be able to misuse it or impersonate the user. This requirement ensures the security of multi-factor authentication.

S6: Resistance to Node Capture Attacks

In scenarios where industrial devices are captured, the adversary must not be able to execute attacks. This requirement is particularly important in DITEN, where edge devices may be physically accessible.

S7: Multi-Factor Security

The scheme must provide strong security even if factors are compromised in a -factor authentication system. This ensures resilience against partial breaches.

Table 5 summarizes the security requirements and their descriptions.

TABLE 5

| Requirement | Description |

|---|---|

| S1: User anonymity | Ensures user activities or identities cannot be traced by adversaries |

| S2: Insider attack resistance | Protects passwords and biometric keys from privileged insiders |