Abstract

The swift evolution of artificial intelligence (AI) has enabled unprecedented capabilities across domains, while simultaneously introducing critical vulnerabilities that can be maliciously exploited or cause unintended harm. Although multiple initiatives aim to govern AI-related risks, a comprehensive and systematic understanding of how AI systems are actively misused in practice remains limited. This paper presents a systematic review of AI misuse across modern AI technologies. We analyze documented incidents, attack mechanisms, and emerging threat vectors, drawing from existing AI risk repositories, prior taxonomies, and empirical case reports. These sources are synthesized into a unified analytical framework that categorizes AI misuse across nine primary domains. Our analysis identifies nine major domains of AI misuse: (1) Adversarial Threats, (2) Privacy Violations, (3) Disinformation, Deception, and Propaganda, (4) Bias and Discrimination, (5) System Safety and Reliability Failures, (6) Socioeconomic Exploitation and Inequality, (7) Environmental and Ecological Misuse, (8) Autonomy and Weaponization, and (9) Human Interaction and Psychological Harm. Within each domain, we examine distinct misuse patterns, providing technical insights into exploitation mechanisms, documented real-world cases with quantified impacts, and recent developments such as large language model vulnerabilities and multimodal attack vectors. We further evaluate existing mitigation strategies, including technical security frameworks (e.g., MITRE ATLAS, OWASP Top 10 for Large Language Models, MAESTRO), regulatory initiatives (e.g., EU AI Act, NIST AI Risk Management Framework), and compliance standards. The findings reveal substantial gaps between the rapid advancement of AI capabilities and the robustness of current defensive, governance, and mitigation mechanisms, with adversaries holding persistent advantages across most attack categories. This work contributes by (i) systematically consolidating fragmented AI risk repositories and misuse taxonomies, (ii) developing a unified taxonomy grounded in both theoretical models and empirical incident data, (iii) critically assessing the effectiveness of existing mitigation approaches, and (iv) identifying priority research gaps necessary for advancing more secure, ethical, and resilient AI systems.

1 Introduction

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has rapidly evolved into one of the most transformative technologies of the 21st century, reshaping industries, governance, and everyday life. Deep learning breakthroughs since 2012 (LeCun et al., 2015), proliferation of LLMs (Brown et al., 2020), advances in generative AI (OECD, 2019), and deployment of autonomous systems (Scharre, 2018) have created unprecedented capabilities. However, these same technologies have also introduced critical vulnerabilities, offering new vectors for malicious exploitation.

The dual-use nature of AI lies at the core of this concern. Algorithms and models designed for beneficial purposes can be adapted for malicious or unethical use. Natural language models that enable intelligent assistants may be leveraged to produce convincing disinformation (Goldstein et al., 2023); generative models supporting creative industries can be used to fabricate realistic deepfakes (Chesney and Citron, 2019); computer vision systems designed for safety or accessibility may facilitate intrusive surveillance or unauthorized biometric profiling (Buolamwini and Gebru, 2018); and recommendation algorithms designed to personalize user experiences can be exploited to manipulate behavior (Matz et al., 2017). As AI systems grow in capability, autonomy, and accessibility, their misuse potential increases in both scale and sophistication.

Recent incidents demonstrate that AI misuse is no longer theoretical but a pressing global issue with measurable consequences: deepfake-enabled fraud exceeding $25 million (Stupp, 2019), AI-generated election disinformation affecting millions (DiResta et al., 2024), wrongful arrests from facial recognition errors (Garvie et al., 2016), algorithmic discrimination in healthcare affecting 200 million people annually (Obermeyer et al., 2019), and adversarial attacks on safety-critical systems (Eykholt et al., 2018). The proliferation of synthetic media, automated cyberattacks, and algorithmic discrimination reflects how AI can amplify deception, erode privacy, and reinforce social inequalities. Moreover, AI-driven automation and personalization have accelerated the scale and precision of harmful activities, from widespread disinformation campaigns to targeted phishing and identity manipulation. These developments highlight a growing mismatch between AI advancement and the capacity to detect, regulate, or mitigate its misuse, raising pressing ethical and security concerns. Recent statistics supporting these observations are shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1

Recent AI Misue Statistics. (a) AI related incidents reported worldwide (2019–2024) from AGILE Index Report 2025. Agile-index.ai (2025)(b) AI related incidents reported worldwide (2014–2024) from Artificial Intelligence Index Report (Stanford, 2025).

Despite the expanding body of literature on AI misuse, the research landscape remains highly fragmented. Existing studies often focus on specific domains, such as deepfakes, adversarial attacks, or data privacy, without integrating insights across technical, ethical, and societal dimensions (Slattery et al., 2024; Tabassi, 2023). Moreover, inconsistent terminology, varied categorization schemes, and rapidly evolving threat models further complicate efforts to develop a unified understanding of the full spectrum of misuse. This fragmentation creates challenges for those seeking to assess risks comprehensively or develop interdisciplinary strategies for prevention and response.

This review addresses that fragmentation by providing a systematic synthesis of AI misuse research across technical, ethical, and societal perspectives. Rather than proposing entirely new theoretical models, this paper organizes and consolidates existing knowledge to create a comprehensive and accessible overview of how AI technologies can be misused. To establish context, we briefly examine empirical AI risk and misuse taxonomies and repositories. Building upon insights from these sources, we propose a consolidated nine-domain categorization of AI misuse, each suitable for detailed technical and socio-ethical analysis. Across these domains, we provide technical depth on exploitation mechanisms, detailed real-world incidents, and discussion of countermeasure effectiveness.

Through extensive analysis of academic publications, industry reports, and documented misuse cases, this paper seeks to:

Critically analyze existing AI risk and misuse taxonomies and repositories, examining how different research initiatives categorize AI threats and identifying convergences, gaps, and complementarities across classification schemes

Synthesize a unified taxonomy of AI misuse that categorizes AI misuse and vectors across technical, social, and ethical dimensions,

Analyze various forms of AI misuse, identifying common vulnerabilities and attack patterns, providing technical depth on exploitation mechanisms, and examining real-world case studies to understand the practical manifestations, impacts, and consequences.

Evaluate existing mitigation strategies, assessing technical security frameworks, regulatory approaches, and compliance standards for their effectiveness, limitations, and applicability across different contexts.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews existing AI misuse and risk frameworks. Section 3 describes the review methodology. Section 4 categorizes AI misuse domains and presents synthesized findings. Section 5 discusses key incidents and implications across domains. Section 6 reviews current mitigation strategies and AI risk governance frameworks. Section 7 concludes with recommendations for future research and governance directions.

2 Background: review of existing AI risk and misuse taxonomies

Several organizations and research groups have developed frameworks and/or taxonomies to classify and understand the risks and misuse of artificial intelligence, reflecting the growing need for systematic approaches to AI safety and governance. We briefly review major existing taxonomies to establish context before presenting our own categorization.

Among the most influential is the MIT AI Risk Repository developed by Slattery et al. (2024), which represents the most comprehensive effort to date, extracting and categorizing 1,612 risks from 65 existing taxonomies (Slattery et al., 2024). The framework organizes risks using a dual approach: a causal taxonomy classifying by entity, intentionality, and timing; and a domain taxonomy with seven domains and 24 subdomains covering discrimination and toxicity, privacy and security, misinformation, malicious actors and misuse, human-computer interaction, socioeconomic and environmental impacts, and AI system safety. While highly valuable for conceptual coverage, the repository largely abstracts away from detailed technical attack mechanisms and operational misuse pathways. Complementing the MIT repository’s academic comprehensiveness, the AIR 2024 taxonomy takes a distinctly different approach by grounding its classification in how organizations operationalize AI risk management. Zeng et al. (2024) developed this taxonomy through systematic analysis of government regulations from the United States, European Union, and China, along with 16 AI company policies from major developers and deployers (Zeng et al., 2024). Rather than starting from theoretical first principles, AIR 2024 constructs a bottom-up taxonomy reflecting how risks are actually categorized in regulatory and corporate practice. However, this approach carries inherent limitations. The taxonomy is necessarily limited to risks explicitly mentioned in reviewed policies, potentially missing emerging threats not yet codified in regulations or corporate guidelines. Given recent policy emphasis on generative AI and large language models following the release of ChatGPT and similar systems, the taxonomy exhibits heavy focus on these technologies while potentially underrepresenting risks in computer vision, robotics, or other AI domains.

Several security-oriented and adversarial taxonomies also focus explicitly on malicious AI use. MITRE Adversarial Threat Landscape for Artificial-Intelligence Systems (ATLAS) provides a tactics–techniques–procedures (TTP) knowledge base documenting real-world attacks on AI systems, including data poisoning, model evasion, and supply-chain compromise (MITRE ATLAS, 2024).

The ENISA AI Threat Landscape similarly categorizes AI-related cybersecurity threats, emphasizing vulnerabilities, attacker capabilities, and systemic impacts (ENISA, 2020). The OWASP Top 10 for LLMs further refines this focus for generative and language models, identifying prompt injection, insecure output handling, training data poisoning, model denial-of-service, and supply-chain vulnerabilities as dominant misuse vectors (OWASP Foundation, 2024).

Beyond security, multiple domain-specific risk taxonomies have emerged. In healthcare, Golpayegani et al. (2022) propose a structured taxonomy covering clinical, ethical, and operational AI risks, highlighting patient harm and diagnostic bias (Golpayegani et al., 2022). In international security, UNIDIR synthesizes AI risks related to strategic stability, escalation dynamics, and confidence-building measures (Puscas, 2023). Mahmoud (2023) examines AI risks in information security, emphasizing automation-enabled attack amplification. The IAA AITF AI Risks Taxonomy (2024) introduces a three-level taxonomy tailored to actuarial and financial risk management, mapping AI-specific risk amplification onto traditional actuarial risk categories. Nevertheless, the narrow sectoral focus of these taxonomies limits broader applicability.

Additional academic contributions have expanded taxonomies to socio-technical and human-centered harms. Critch and Russell (2023) introduced their Taxonomy and Analysis of Societal-Scale Risks from AI (TASRA), examining macro-level dimensions including risk accountability and ethical alignment (Critch and Russell, 2023). TASRA focuses on long-term, systemic risks rather than near-term incidents, considering how AI could reshape power dynamics, decision-making authority, and social institutions. Weidinger et al. (2022) proposed taxonomies specifically targeting large language model risks, highlighting concerns such as discrimination, information hazards, and malicious uses (Weidinger et al., 2022). Marchal et al. (2024) focused on generative AI misuse, identifying threats including prompt injection, model leakage, and large-scale disinformation (Marchal et al., 2024). Tanaka et al. (2024) similarly proposed a taxonomy of generative AI applications for risk assessment that organizes and consolidates generative AI risk issues identified in existing studies into distinct risk domain classes and their associated factors and impacts. By decomposing broad concerns about generative AI into more precise risk issues and linking them to their potential effects, this taxonomy facilitates clearer understanding of hazards and provides structured information that supports development of targeted countermeasures (Tanaka et al., 2024). Moreover, Zhang et al. (2025) addressed the emerging domain of AI companionship applications, developing a taxonomy of harmful algorithmic behaviors that can occur in human-AI relationship, examining the psychological and relational harms that can emerge when AI systems are designed to form ongoing personal bonds with users, including emotional manipulation, unhealthy dependency, and intimate privacy violations (Zhang et al., 2025).

Apart from the existing taxonomies, incident-centered repositories provide empirical grounding. The AI Incident Database (AIID), systematically catalogs real-world AI failures and misuse events, emphasizing recurrence patterns and socio-technical root causes (McGregor, 2021). In addition to AIID’s breadth, the AI, Algorithmic, and Automation Incidents and Controversies Repository (AIAAIC) takes a distinctly different approach emphasizing ethical and societal impacts. As an independent, grassroots initiative documenting over 1,500 incidents since 2019, AIAAIC adopts an “outside-in” perspective focusing on external harms to individuals, communities, society, and environment rather than primarily technical failures. Similarly, the OECD AI Incident Monitor aggregates reported AI-related incidents across jurisdictions, offering longitudinal insights into emerging misuse trends (OECD, 2023). It provides an international repository of documented AI incidents, collecting reports from multiple sources including news media, research papers, and direct submissions (OECD.AI, 2024). The database categorizes incidents by type (bias/discrimination, privacy violation, safety failure, etc.), sector (healthcare, finance, transportation, etc.), and AI technology involved (computer vision, NLP, recommendation systems, etc.). These repositories shift the focus from hypothetical risks to documented harms, but do not provide fine-grained technical taxonomies. Hence, their limitation lies in their limited technical depth in incident descriptions.

Beyond these major repositories, several other incident resources warrant mention. AI Vulnerability Database (AVID) provides a functional taxonomy organized around security, ethics, and performance dimensions, designed to enable systematic evaluation and testing (AVID, 2023). The limitation stems from its relatively smaller scale, its primary focus on only model/system-level technical failures rather than broader sociotechnical harms, and its less coverage of misuse by malicious actors.

Collectively, these taxonomies and repositories provide complementary but fragmented views of AI misuse, varying in scope, granularity, and empirical grounding (refer to Table 1). Some emphasize technical attack vectors, others societal harms or domain-specific risks, and few attempt holistic integration. Building upon these efforts, this review consolidates and aligns them into a unified nine-domain taxonomy of AI misuse, collectively capturing the technical, ethical, and socio-technical dimensions of contemporary AI misuse, grounded in documented incidents and technical exploitation mechanisms, representing both underrepresented dimensions such as environmental sustainability as well as established concerns.

TABLE 1

| Source | Scope | Structure | Contributions | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General-Purpose Taxonomies | ||||

| MIT AI Risk Repository (Slattery et al., 2024) | Synthesis of taxonomies covering AI risks across domains | Dual taxonomy: causal and domain based | Comprehensive meta-review; integrates academic, industry, and policy perspectives | Conceptual and highly abstract; limited representation of concrete technical attack paths |

| AIR 2024 Taxonomy (Zeng et al., 2024) | Bottom-up taxonomy grounded in regulations (US, EU, China) and corporate policies; operational perspective | Four-level hierarchy from broad risk classes to prohibited uses | Grounded in real regulatory and corporate practice; enables cross-jurisdictional comparison; highlights regulatory blind spots | Limited to documented risks; heavy focus on GenAI/LLMs; underrepresents emerging threats; limited technical depth |

| Foundation Model Risk Taxonomy (Bommasani et al., 2021) | Large-scale foundation models (BERT, GPT, CLIP, DALL-E, etc.) | 12 risk categories: Reliability, Fairness, Misuse, Environmental, Legal, Economic, and more | Systematic analysis of foundation models; identifies centralization risks, model homogenization, environmental costs, legal and economic considerations; highlights multi-domain impacts and cascading effects | Focuses only on foundation models and does not address end-to-end risks across diverse AI systems or deployment contexts |

| Generative AI and Language Model Taxonomies | ||||

| OWASP Top 10 for LLMs | Security vulnerabilities in LLM-based systems | Top-10 vulnerability list with mitigation guidance | Practical misuse taxonomy for LLMs including prompt injection, insecure output handling, model DoS, and training-data poisoning | Narrow to LLMs; limited broader AI applications |

| LLM Risk Taxonomy (Weidinger et al., 2022) | Risks specific to large language models | Six major harm categories | Foundational LLM-focused taxonomy; detailed subcategories; updated post-ChatGPT | Limited beyond NLP |

| Generative AI Misuse (Marchal et al., 2024) | Exploitation and compromise of generative AI | Capability exploitation vs. system compromise | Taxonomy of generative-AI misuse including prompt abuse, model leakage, and disinformation campaigns | Narrow to generative AI; limited socio-technical integration; limited mitigation depth |

| Generative AI Risk Taxonomy (Tanaka et al., 2024) | Generative AI applications across domains | Domain-based organization linked to societal impact categories | Classifies generative-AI application domains and associated risk categories (e.g., misinformation, privacy loss, economic harm, environmental impact); supports structured risk assessment across deployment contexts | Lacks fine-grained technical attack modeling; limited focus |

| Domain-Specific Risks | ||||

| Healthcare AI Risks (Golpayegani et al., 2022) | Clinical AI systems | Structured taxonomy of clinical, ethical, and operational risks in medical AI | Strong patient safety and medical ethics grounding; addresses diagnostic bias and patient harm | Healthcare-specific; may not generalize to other domains |

| Biosecurity AI Risks Characterization (Sandbrink, 2023) | AI-enabled biological misuse | Differentiates AI tools (LLMs vs. Biological Design Tools) and their mechanisms of harm | Identifies how LLMs increase accessibility, and BDTs raise the ceiling of harm; anticipates combined LLM + BDT risks | Lacks hierarchical structure; domain-specific focus |

| AI Companionship Harms (Zhang et al., 2025) | Emotional and relational AI systems | Psychological and relational harm categories | Human-centered taxonomy of psychological, relational, and privacy harms in long-term human–AI interactions | Narrow domain; non-technical; human-centered focus |

| IAA AITF AI Risk Taxonomy | Financial services and insurance | Three-level actuarial taxonomy mapping AI-driven risk amplification onto financial risk categories | Maps AI-specific risks onto traditional actuarial categories; sector-specific examples; aligns AI risks with professional risk frameworks | Sector-specific; limited treatment of ML-specific attacks and misuse |

| UNIDIR AI Risk Framework | Military and international security | Strategic stability and escalation risk categories | Taxonomy of AI risks to international security, strategic stability, escalation dynamics, and arms control | Narrow geopolitical scope; lacks technical details |

| TASRA (Critch and Russell, 2023) | Societal-scale AI transformation risks | Accountability, alignment, and institutional impact dimensions | Captures systemic and long-term societal risks; emphasizes power and governance | Long-term and conceptual; limited near-term operational applicability |

| Incident Repositories and Empirical Risk Sources | ||||

| AI Incident Database (AIID) | Real-world AI failures across sectors and development and deployment lifecycles | Harm type, technology, sector, and actors | Empirical repository of real-world AI failures and misuse incidents; highlights recurrence patterns and socio-technical causes | Incident-focused; limited technical detail |

| AIAAIC Repository | Societal and ethical AI harms and controversies | Incident and controversy documentation | Strong coverage of non-technical harms; civil society and ethics focus | Relies on public reporting; limited technical granularity |

| OECD AI Incident Monitor | Global AI incident monitoring | Automated media-based classification | Cross-jurisdictional incident taxonomy categorized by sector, harm type, and AI technology | Documentation-oriented; lacks deep technical analysis |

| MITRE ATLAS | Adversarial attacks on AI systems | TTP-based taxonomy aligned with ATT&CK phases | Concrete attack techniques across ML lifecycle; real-world case studies; bridges AI and cybersecurity practices | Focused on cybersecurity; limited socio-technical or ethical considerations |

| ENISA AI Threat Landscape | Cybersecurity threats to AI systems | Threat, vulnerability, and attacker-capability categorization | Systematic EU-centric threat analysis; strong supply-chain emphasis | Predates recent GenAI advances; limited socio-technical coverage |

| AVID (AI Vulnerability Database) | Testable AI vulnerabilities across security, ethics, and performance | Dual view: effect-based and lifecycle-based | Reproducible vulnerability tests; benchmarking support; integration with cybersecurity tooling | Smaller scale; system-level focus; limited coverage of broader societal harms |

Comparative summary of representative AI risk and misuse taxonomies, repositories, and knowledge bases.

3 Methodology

This study employs a mixed-methods approach, combining a systematic literature review with in-depth case study analysis to develop a comprehensive understanding of AI misuse patterns and mitigation strategies. By integrating these elements, the research bridges technical, social, and ethical perspectives, while grounding theoretical insights in real-world incidents.

3.1 Reporting standards

This study presents a systematic review in accordance with the PRISMA 2020 guidelines as illustrated in Figure 2 (Haddaway et al., 2022). Academic literature was retrieved from major scholarly databases including IEEE Xplore, Scopus, and the ACM Digital Library. In parallel, relevant case-based and policy-oriented materials were sourced from grey literature repositories and organizational databases such as the NIST repository, MIT AI Repository, AI Incident Database (AIID), and AIAAIC. To capture developments coinciding with the rise of modern AI applications, the search covered the period from 2012 to 2025, aligning with the deep learning era and the acceleration of AI adoption across critical domains. The search queries combined key terms such as “artificial intelligence misuse”, “AI risks”, “AI security threats”, “adversarial attacks”, “AI safety”, “algorithmic bias”, “deepfakes”, and related variations.

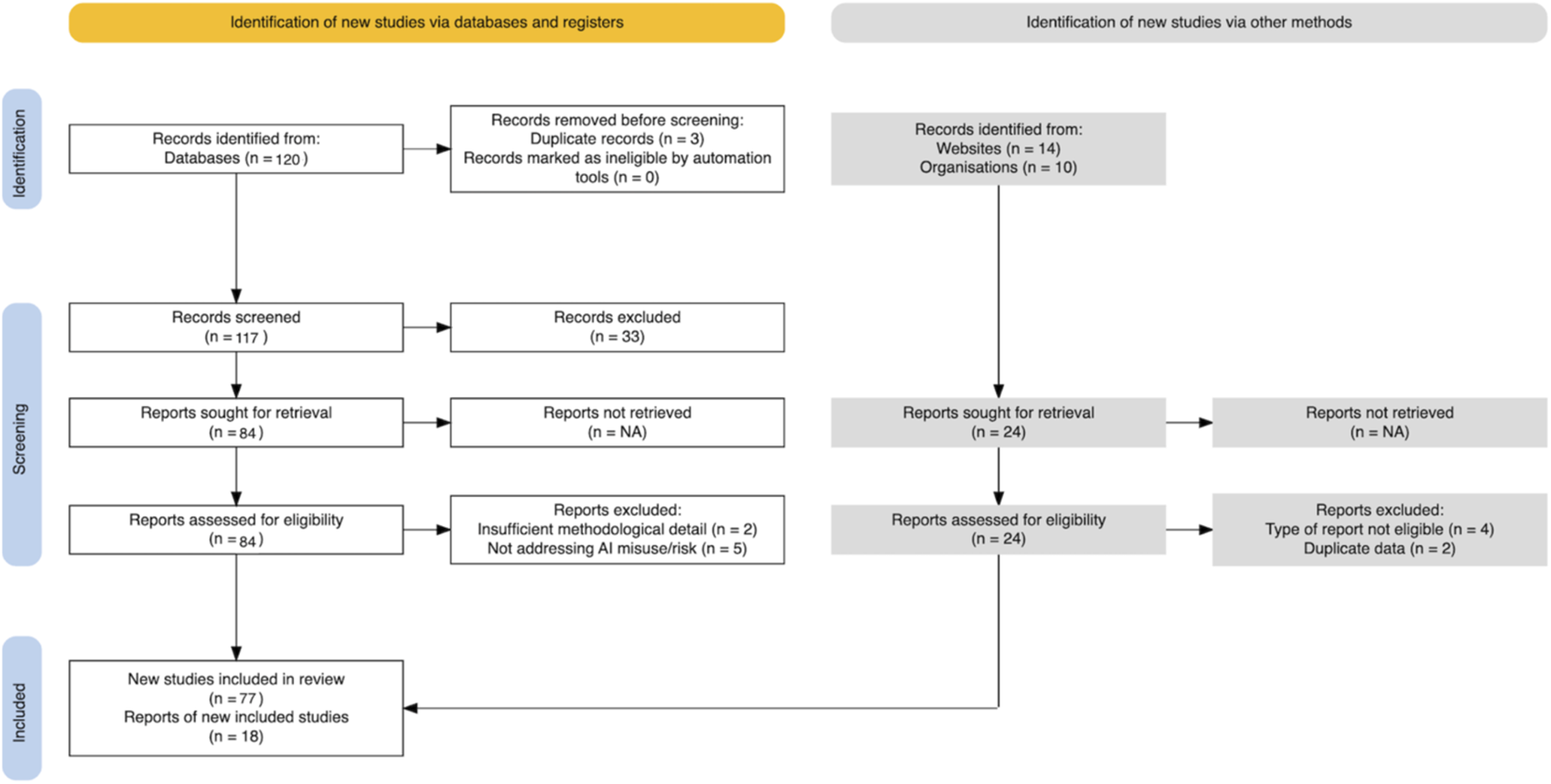

FIGURE 2

PRISMA flow diagram of study selection.

A total of 144 records (120 from academic databases and 24 from other sources) were initially identified. After removing duplicate records, 141 unique studies were screened based on titles and abstracts. During this phase, 33 papers were excluded due to not meeting the inclusion criteria. Full-text retrieval was sought for 84 studies, of which seven were excluded after detailed assessment. The remaining 77 database-based studies were included in the final synthesis. From the additional 24 external sources, six reports were excluded, and 18 reports were retained. Altogether, 95 studies (77 database studies +18 other sources) were included in the final review.

The diagram (Figure 2) outlines the identification, screening, eligibility assessment, and inclusion process for the reviewed studies.

3.2 Case study selection

Case studies were identified through systematic monitoring of multiple sources including the AI Incident Database, vulnerability disclosures, regulatory publications, industry transparency reports, and media coverage. The aim was to capture a diverse set of examples spanning different domains of misuse, levels of severity, and cultural or geographic contexts. Selected cases were required to have documented evidence verifying the incident. This ensured that the analysis addressed both technical and social dimensions of misuse and highlighted the ways AI vulnerabilities manifest in practice.

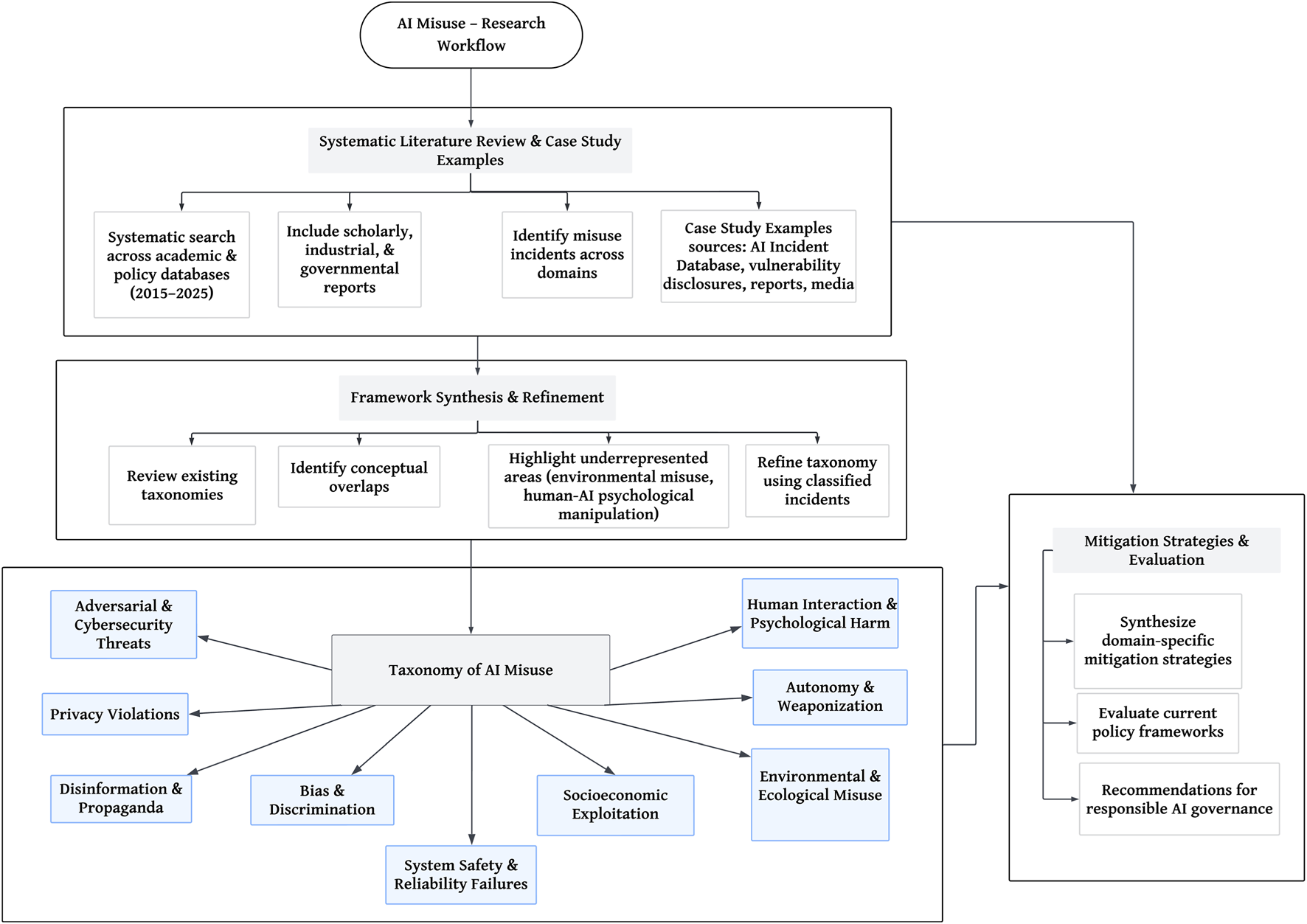

3.3 Taxonomy development

The taxonomy of AI misuse was derived through a systematic synthesis of major AI risk frameworks, consolidating and extending them into a unified and comprehensive classification. Drawing on established taxonomies, we identified key conceptual overlaps and critical gaps, particularly in areas such as environmental sustainability and human-AI psychological manipulation. Accordingly, AI misuse was classified into nine domains encompassing both the technical and socio-technical dimensions of contemporary misuse, as shown in Table 2. The detailed research workflow is given in Figure 3, illustrating the methodological workflow adopted in the study, beginning with a systematic literature review and case study analysis, followed by framework synthesis and refinement, taxonomy construction, and the formulation of mitigation strategies.

TABLE 2

| | Domain | Key examples (attack types) | Mechanisms | Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Adversarial threats | Evasion attacks, poisoning, backdoors, model extraction, membership inference, model inversion, supply chain attacks | Subtle perturbations to inputs, maliciously crafted training data, unauthorized model queries, compromised dependencies in AI pipelines | Compromise of AI integrity, intellectual property theft, inaccurate outputs in critical systems (e.g., autonomous vehicles, medical AI) |

| 2 | Privacy violations | Sensitive attribute inference, re-identification, data leakage, unauthorized surveillance | Analysis of model outputs, correlational inference, generative model reconstruction | Breach of user confidentiality, regulatory violations, erosion of trust in digital services |

| 3 | Disinformation, Deception, & Propaganda | Deepfakes, automated fake news, targeted propaganda, harmful/illegal content generation, prompt injection, erosion of trust | Generative models for text, image, video; automated amplification on social media | Misinformation at scale, manipulation of public opinion, destabilization of political and social systems |

| 4 | Bias & Discrimination | Gender, racial, socioeconomic biases; opaque decision-making; stereotyping | Biased training data, reinforcement of historical inequities, algorithmic opacity | Unequal access to services, perpetuation of social inequities, reputational and legal risks for deploying organizations |

| 5 | System Safety & Reliability Failures | Autonomous vehicle accidents, misdiagnoses in healthcare, industrial automation failures | Model misbehavior under unexpected conditions, inadequate validation and monitoring | Physical harm, operational disruption, loss of human life or safety incidents |

| 6 | Socioeconomic Exploitation & Inequality | Job displacement, economic fraud, cheating, microtargeting, exploitation of vulnerable populations | Automation replacing human labor, AI-driven manipulation of financial and social systems | Increased economic disparities, reduced employment opportunities, ethical and legal challenges in AI governance |

| 7 | Environmental & Ecological Misuse | High energy consumption of AI, carbon-intensive model training, automated harmful industrial practices | Resource-intensive model training, misuse of AI in environmental systems | Increased carbon footprint, ecological damage, sustainability concerns |

| 8 | Autonomy & Weaponization | Autonomous drones, lethal AI weapons, cyber-physical attacks, Agentic AI systems | Decision-making without human oversight, AI-guided military systems | Escalation in conflict, ethical concerns over lethal AI, potential breaches of international law |

| 9 | Human Interaction & Psychological Harm | Emotional manipulation via AI, addiction to AI interfaces, mental health impacts | Personalized content targeting, persuasive AI, immersive digital environments | Anxiety, depression, behavioral manipulation, loss of agency and autonomy |

Taxonomy of AI misuse.

FIGURE 3

Methodological workflow of the research.

4 Taxonomy of AI misuse

To enable systematic analysis of AI misuse, this study develops a taxonomy that organizes threat vectors across nine primary domains, each further divided into subcategories. These domains encompass adversarial and cybersecurity threats, privacy violations, disinformation and synthetic media, bias and discrimination, system safety and reliability failures, socio-economic exploitation and inequality, environmental and ecological misuse, autonomy and weaponization, and human interaction and psychological harm. While these categories represent distinct manifestations of misuse, they are also deeply interconnected, with vulnerabilities in one domain frequently compounding risks in another. By organizing the landscape in this structured manner, the taxonomy provides a comprehensive framework for both researchers and practitioners to classify incidents, anticipate threats, and design targeted interventions (Slattery et al., 2024; NIST, 2023).

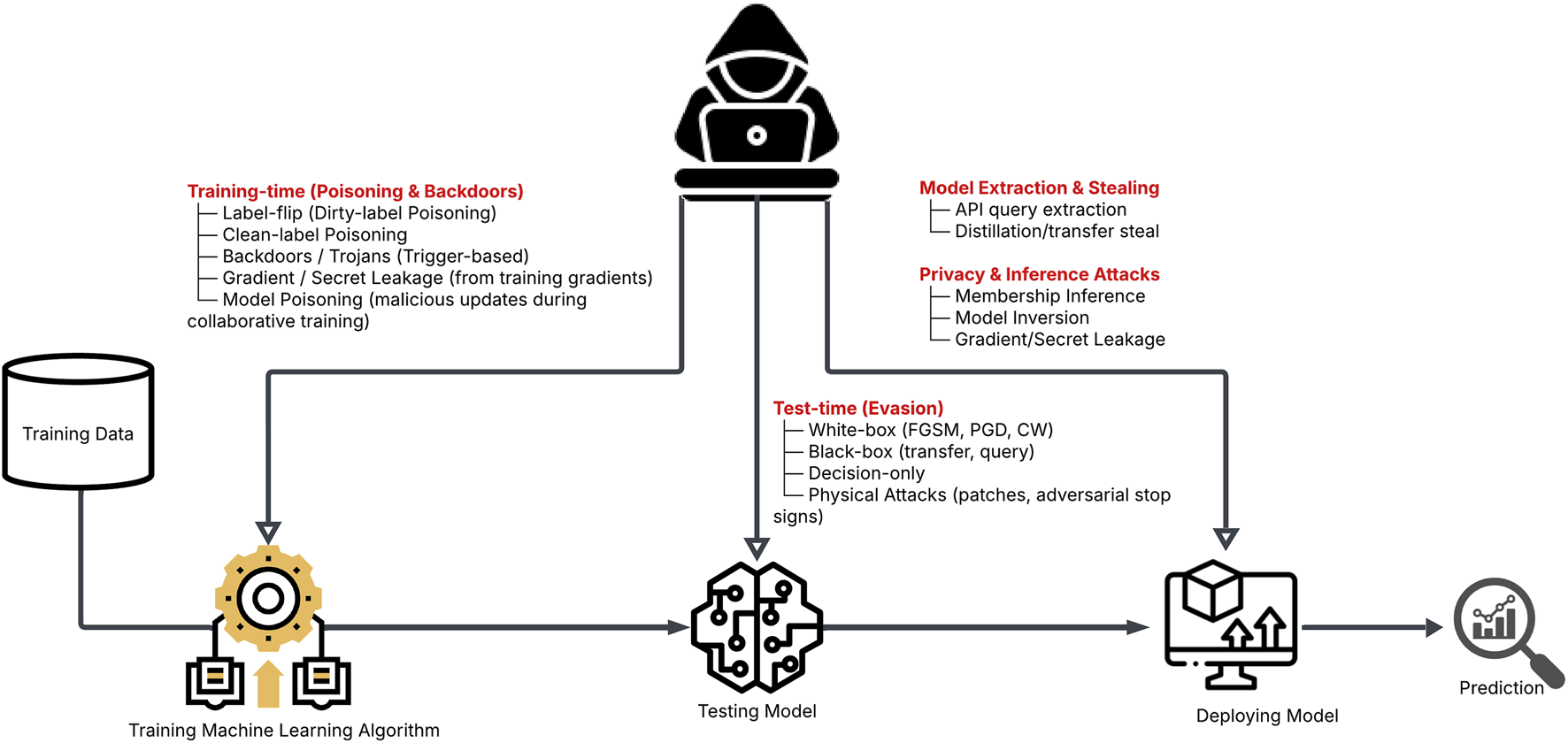

4.1 Adversarial Threats

Machine learning systems are vulnerable to a wide array of adversarial attacks that exploit both the data and model layers of the learning pipeline (as shown in Figure 4). Evasion attacks exploit weaknesses in trained models by subtly perturbing inputs, causing misclassifications without visibly altering the underlying data (Biggio et al., 2013). These perturbations are often unnoticable to humans but are designed to shift the input across the model’s decision boundary. Such attacks are particularly concerning in real-time systems, where even minor perturbations to data can induce high-confidence yet incorrect predictions, compromising safety-critical applications such as helathcare decsisons, autonomous navigation, or biometric authentication.

FIGURE 4

Examples of adversarial attacks across the machine learning lifecycle.

Poisoning attacks, in contrast, corrupt the training dataset itself, embedding malicious patterns that compromise the integrity of models even before deployment (Gu et al., 2017). Attackers may inject a small fraction of poisoned samples into the training sets to manipulate model behavior, either globally (causing widespread accuracy degradation) or specifically (triggering backdoor conditions under certain inputs). For instance, a backdoor poisoning attack might train a face recognition model to always classify images containing a specific pixel pattern as a trusted user, regardless of the actual identity. Such manipulation remains dormant during evaluation, evading detection, and activates only under attacker-controlled triggers. Because machine learning pipelines often rely on large, automatically scraped or user-contributed data, the injection of poisoned samples is both feasible and difficult to detect. Gu et al. (2017) introduced “BadNets,” demonstrating how backdoor triggers embedded in training data enable attackers to maintain control over model behavior post-deployment. The poisoned model performs normally on clean inputs but exhibits attacker-specified behavior when triggered.

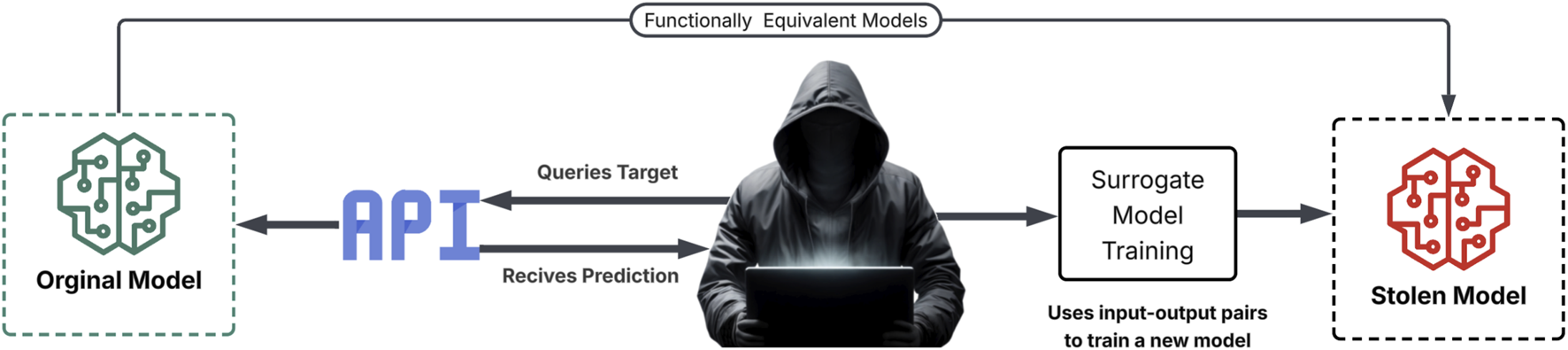

Model extraction attacks further extend the adversarial threat surface by demonstrating how adversaries can reconstruct proprietary models through systematic querying and analyzing outputs (Papernot et al., 2017). By sending numerous inputs to a deployed model (often accessible via APIs) and recording the corresponding outputs, attackers can approximate the model’s decision boundaries and replicate its functionality locally (see Figure 5). This stolen surrogate model can then be exploited for additional purposes, such as launching more precise evasion attacks or performing model inversion to recover sensitive training data. In many cases, such extraction requires no privileged access, relying solely on adaptive query strategies and output probability vectors exposed by the API. Tramèr et al. demonstrated that prediction APIs expose sufficient information for attackers to build functionally equivalent models (Tramèr et al., 2016).

FIGURE 5

Model extraction attack.

These attacks are not merely academic. In computer vision, adversarial perturbations have been shown to cause traffic sign recognition systems to misidentify stop signs as yield signs, with potentially catastrophic consequences for autonomous driving (Eykholt et al., 2018). In natural language processing, adversarial inputs can be crafted by substituting semantically similar words or introducing orthographic noise, allowing attackers to manipulate sentiment analysis models or bypass content moderation. The persistence of these vulnerabilities highlights the fragility of AI systems operating in adversarial environments (Madry et al., 2018).

4.2 Privacy violations

AI systems frequently depend on vast amounts of personal and sensitive data, creating risks of privacy violations at multiple levels. At the individual level, models are vulnerable to attacks that expose whether particular data points were part of the training set, referred as membership inference attack (Hu et al., 2022). Model inversion attacks similarly enable the reconstruction of sensitive features from model outputs (Fredrikson et al., 2015). These vulnerabilities illustrate that AI systems, even when anonymized, can inadvertently leak private information.

At the systemic level, AI-driven surveillance technologies such as facial recognition amplify longstanding privacy concerns. It has been demonstarted by Sharif et al. (2016), that specially crafted eyeglass frames could enable individuals to impersonate others or evade facial recognition systems and access controls, making them particularly concerning for safety-critical applications (Sharif et al., 2016). Other studies have also revealed consistent accuracy disparities across demographic groups (Buolamwini and Gebru, 2018), raising both technical and ethical questions about their use in law enforcement and public surveillance (Garvie et al., 2016). As AI systems become more deeply embedded in public and commercial infrastructures, the tension between utility and privacy continues to intensify. Without stronger safeguards, transparency, and privacy-preserving techniques, AI risks normalizing pervasive surveillance and eroding individual privacy.

4.3 Disinformation and synthetic media

The proliferation of generative models has dramatically transformed the landscape of disinformation. Deepfakes exemplify the capacity of AI systems to generate highly realistic yet fabricated content, including videos, audio, and images. These technologies have been used to create non-consensual intimate imagery, impersonate public officials, and manipulate political discourse (Chesney and Citron, 2019; Vaccari and Chadwick, 2020). Large language models further extend this threat by enabling automated production of persuasive, coherent text at unprecedented scale (Goldstein et al., 2023). The convergence of these technologies enables campaigns of influence that are more targeted, scalable, and difficult to attribute than traditional forms of propaganda.

The societal consequences of synthetic media are amplified by what Chesney and Citron (2019) describe as the “liar’s dividend”, whereby the mere existence of deepfakes undermines trust in authentic information (Chesney and Citron, 2019). Thus, AI-driven disinformation poses not only direct harm by spreading falsehoods but also indirect harm by eroding epistemic trust - the shared confidence in sources of knowledge - within societies.

4.4 Bias and discrimination

The embedding of bias into AI systems represents one of the most significant ethical challenges in contemporary deployment. Bias can arise at any stage of the machine learning pipeline, from the framing of research questions to data collection and algorithmic optimization (Barocas and Selbst, 2016). Empirical evidence has repeatedly demonstrated how these biases translate into discriminatory outcomes. Buolamwini and Gebru (2018) showed that commercial facial recognition systems misclassified darker-skinned women at rates far higher than lighter-skinned subjects (Buolamwini and Gebru, 2018). Obermeyer et al. (2019) also identified racial bias in healthcare algorithms that systematically underestimated the needs of Black patients (Obermeyer et al., 2019). Similarly, Angwin et al. (2016) documented how criminal justice risk assessment systems produced racially skewed predictions (Angwin et al., 2016). Such accuracy disparities have tangible real-world consequences. For example, in 2020, Robert Williams became the first documented case of wrongful arrest due to a facial recognition error, after Detroit Police Department’s system generated a false match (Evans, 2022).

Mitigating bias remains a profound challenge. Debiasing strategies, such as re-weighting datasets or modifying loss functions, have achieved partial success (Corbett-Davies et al., 2023; Mehrabi et al., 2021). Yet scholars caution that fairness is a contested and multidimensional concept, with different definitions often mathematically incompatible (Green and Viljoen, 2020). Moreover, technical fixes alone cannot address the structural inequalities that biases both reflect and reinforce.

4.5 System Safety & Reliability Failures

AI has become a dual-use technology in cybersecurity, serving both defensive and offensive roles. On the defensive side, machine learning enhances intrusion detection systems, anomaly detection, and malware classification. On the offensive side, adversaries have leveraged AI to automate phishing campaigns, discover software vulnerabilities, and craft adaptive malware (Brundage et al., 2018; Apruzzese et al., 2018).

The emergence of large language models intensifies these threats by lowering the technical barriers to entry. Yao et al. demonstrated that such models can be prompted to generate functional malicious code, while Perez and Ribeiro. (2022) showed how adversarial prompting can circumvent built-in safeguards (Yao et al., 2024; Perez et al., 2022). These capabilities enable attackers with limited expertise to mount sophisticated operations, thereby expanding the threat landscape.

Apart from these, AI systems deployed in safety-critical applications present risks of catastrophic failures when models behave unexpectedly or incorrectly under operational conditions. For instance. Autonomous vehicles have been involved in multiple accidents resulting from perception failures, planning errors, and inadequate handling of edge cases.

4.6 Socioeconomic Exploitation and inequality

AI technologies have significant implications for labor markets and economic structures. Automation driven by AI has displaced workers across various sectors, from manufacturing to customer service (Brynjolfsson and McAfee, 2014; Acemoglu and Restrepo, 2020). While some argue that new job categories will emerge, the transition period creates substantial economic disruption and exacerbates inequality (Autor, 2015).

AI also enables new forms of economic manipulation, including algorithmic pricing collusion, predatory microtargeting, and exploitation of vulnerable populations through personalized manipulation (Susser et al., 2019; Calvano et al., 2020). These applications raise concerns about fairness, autonomy, and the concentration of economic power.

4.7 Environmental and ecological misuse

The environmental impact of AI training and deployment has gained increasing attention. Large-scale model training requires substantial computational resources, resulting in significant energy consumption and carbon emissions (Strubell et al., 2019). Additionally, AI can be misused to optimize environmentally harmful activities or bypass environmental regulations (Crawford and Joler, 2018). These risks are exacerbated by the growing scale and accessibility of AI technologies, which make it easier for actors with limited oversight to exploit systems in ways that harm ecological sustainability.

4.8 Autonomous weaponization

Perhaps the most controversial domain of AI misuse concerns its application in military and defense systems. Lethal autonomous weapons systems (LAWS) have been identified as a critical area of concern, as they raise profound ethical, legal, and strategic dilemmas (Scharre, 2018). Scholars argue that delegating life-and-death decisions to machines undermines human accountability, risks lowering thresholds for armed conflict, and destabilizes international security (Russell, 2019). Despite calls for international regulation, progress toward binding agreements has been limited (Campaign to Stop Killer Robots, 2020).

Beyond lethal systems, AI has also been deployed for intelligence analysis, logistics optimization, and cyber operations, illustrating its broader role in military applications. The dual-use nature of these technologies complicates regulation, since advances intended for civilian purposes can be readily adapted for warfare (Horowitz et al., 2018).

Apart from these, agentic AI systems introduce novel attack vectors through their capacity for autonomous reasoning, tool use, and multi-step task execution. Unlike traditional AI systems that operate within narrowly defined boundaries, agentic systems can pursue goals through complex action sequences with minimal human oversight, creating opportunities for misuse. Agentic systems can autonomously chain together multiple attack steps, such as reconnaissance, exploitation, lateral movement, and data exfiltration, without requiring human intervention at each stage, challenging static security measures designed for simpler models (Ferrag et al., 2025; Shrestha et al., 2025). Moreover, these systems can learn and adapt their strategies in real-time based on defensive responses, making static security measures less effective. With access to APIs, code execution environments, and system tools, agentic AI can misuse legitimate functionality to achieve unauthorized objectives, potentially escalating privileges through logical reasoning rather than traditional exploitation. Recent demonstrations have shown proof-of-concept scenarios where LLM-based agents autonomously exploit vulnerabilities, conduct social engineering, or manipulate financial systems (Zhang et al., 2025). While large-scale malicious deployment remains limited, the rapid advancement of agentic capabilities warrants proactive security consideration.

4.9 Human interaction and psychological harm

AI systems designed to engage users can have unintended psychological consequences. Persuasive AI, personalized content targeting, and immersive digital environments can lead to behavioral manipulation, addiction, and mental health impacts (Burr et al., 2020). The opacity of these systems makes it difficult for users to recognize when they are being manipulated, raising concerns about autonomy and wellbeing.

Although presented as distinct domains, these categories of misuse are deeply interconnected. Disinformation campaigns may be amplified by adversarially manipulated recommendation systems; bias in training data can exacerbate privacy violations; and cybersecurity threats can intersect with disinformation by spreading AI-generated propaganda through compromised platforms. Understanding these intersections is critical for developing holistic defensive strategies that address the complex ways in which AI misuse manifests across technological, social, and geopolitical contexts.

5 Case studies of AI misuse

This section presents detailed case studies illustrating real-world instances of AI misuse across multiple domains, highlighting technical mechanisms, impacts, responses, and lessons learned. These cases serve to contextualize the taxonomy of AI misuse described previously and underscore both the opportunities and risks inherent in AI technologies.

5.1 Deepfake Pornography and non-consensual intimate imagery

Since 2017, deepfake technology has been widely weaponized to generate non-consensual pornographic content, disproportionately targeting women, including celebrities, journalists, politicians, and private individuals (Ajder et al., 2019). Early deepfakes relied on GAN-based face-swapping models trained on publicly available images, but modern tools, such as DeepFaceLab1 and commercial applications, have democratized creation, enabling realistic content creation with minimal technical expertise. Advances in model architecture and training methods have resulted in highly realistic outputs that are increasingly indistinguishable from authentic content.

The impact on victims is profound, including psychological distress, reputational damage, and sustained harassment. The rapid and widespread dissemination of such content online renders complete removal virtually impossible. Legal recourse remains limited in many jurisdictions, although some regions, such as Virginia, California, and the United Kingdom, have enacted laws criminalizing non-consensual deepfakes. While detection tools have emerged, they struggle to keep pace with increasingly sophisticated fakes, and platform enforcement remains inconsistent. This case highlights the inadequacy of purely reactive approaches, emphasizing the need for victim-centered strategies, robust legal frameworks, and platform accountability (MacDermott, 2025).

5.2 The 2024 election disinformation campaigns

The 2024 US presidential election witnessed unprecedented deployment of AI-generated disinformation, including fabricated videos, AI-authored articles, and coordinated bot networks disseminating false narratives (DiResta et al., 2024). Large language models generated thousands of fake news articles and social media posts with human-level writing quality, while voice cloning enabled the creation of false audio of candidates making controversial statements. Moreover, automated accounts amplified content across platforms, and personalization algorithms targeted specific voter segments with tailored messaging.

Although direct electoral impact remains difficult to measure, the campaigns spread misinformation to millions of voters, complicated fact-checking efforts, and further eroded trust in information sources. This case underscores the scale and sophistication achievable with AI-powered disinformation and demonstrates that reactive detection approaches alone are insufficient without coordinated strategies involving platforms, governments, civil society, and technical researchers, etc. to defend users against manipulative content.

5.3 Clearview AI and mass surveillance

Clearview AI aggregated billions of facial images from social media and other publicly available sources without consent to build a facial recognition database marketed to law enforcement and private entities (Hill, 2020). The company collected approximately ten billion images with associated metadata, enabling searches for any individual across the internet from a single photograph. State-of-the-art deep learning models provided high recognition accuracy, raising concerns about pervasive surveillance and privacy violations.

The system facilitated monitoring of activists, protesters, and ordinary citizens, and disparities in accuracy generated discriminatory outcomes. Legal actions in multiple jurisdictions, including the EU, Canada, Australia, and several United Kingdom states, resulted in fines and restrictions, while some law enforcement agencies ceased using the service. Nonetheless, the collected data cannot be retroactively “uncollected,” and the company continues operations. This case illustrates the limitations of privacy frameworks designed for pre-AI contexts, demonstrating that proactive regulation to prevent data collection is essential, given the stark asymmetry between surveillance capability and individual privacy protection.

5.4 Algorithmic bias in healthcare resource allocation

In a study, Obermeyer et al. showed that a widely used algorithm in U.S. health systems systematically under-identified Black patients for enrollment into high-risk care management programs, relative to White patients with equivalent illness (Obermeyer et al., 2019). At the same risk score, Black patients were measurably sicker. The algorithm used healthcare costs as a proxy for medical needs, and because Black patients tend to incur lower costs for the same level of illness (due to unequal access and systemic barriers), the model underestimated their needs. In the studied sample, correcting for this bias would raise the share of Black patients flagged for extra care from 17.7% to 46.5%. In response, the algorithm developer committed to addressing the bias, prompting hospitals to audit other predictive tools. This case underscores how proxies correlated with sensitive attributes can encode bias, emphasizing the importance of understanding causal mechanisms rather than relying solely on correlations. It also highlights ethical considerations in defining optimization objectives and the necessity of comprehensive algorithmic auditing.

5.5 Voice-cloning CEO fraud

In March 2019, criminals exploited AI voice-cloning technology to impersonate a CEO’s voice, successfully convincing a subordinate to transfer $243,000 to fraudulent accounts (Stupp, 2019). Commercial voice synthesis tools trained on publicly available audio enabled the attackers to mimic speech patterns, tone, and accent convincingly. Beyond the immediate financial loss, the incident exposed vulnerabilities in voice-based authentication, previously considered secure, and demonstrated how AI can weaponize social engineering.

Organizations responded by implementing multi-factor authentication, out-of-band verification, and security training addressing voice-cloning risks. The case illustrates that AI capabilities can compromise traditional security assumptions, that low technical barriers facilitate broad exploitation, and that human factors often remain the weak link despite technical safeguards.

5.6 Adversarial attacks on autonomous vehicle systems

Research has demonstrated that autonomous vehicle vision systems can be misled by adversarial perturbations, such as strategically placed stickers on stop signs causing misclassification as speed limit signs (Eykholt et al., 2018). In these experiments, researchers used optimization algorithms to determine the smallest possible visual changes, that could consistently fool the vehicle’s recognition model even under varying real-world conditions like different lighting, viewing angles, and distances. Although these attacks were conducted in controlled research environments rather than malicious settings, they expose fundamental weaknesses in safety-critical AI systems and highlight ongoing concerns about security, reliability, and potential misuse.

In 2018, an autonomous test vehicle in Tempe, Arizona, struck and killed a pedestrian, illustrating the real-world consequences of imperfect autonomous systems (Penmetsa et al., 2021). Tesla’s Autopilot has also been involved in numerous crashes, some fatal, often occurring when the system fails to detect stationary obstacles, misinterprets road geometry, etc. The United Kingdom National Transportation Safety Board has documented cases where drivers over-relied on automation and failed to maintain attention as required (Chu and Liu, 2023). Developers have begun incorporating adversarial training and robustness testing, yet comprehensive solutions remain elusive. These incidents emphasize that AI vulnerabilities extend from digital to physical domains, requiring security considerations from the design stage and defense-in-depth strategies rather than reliance solely on perceptual capabilities.

6 Mitigation strategies and evaluation

Mitigation of AI-related risks requires a multifaceted approach encompassing technical, regulatory, organizational, and social interventions. Each of these approaches is discussed in the following sections and a summary of the strategies is provided in Table 3.

TABLE 3

| Approach category | Representative techniques | Effectiveness | Limitations | Deployment status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technical - Adversarial robustness | Adversarial training, Certified defenses | Low-Medium | Trade-offs, Adaptive adversaries | Research/Limited deployment |

| Technical - Detection | Deepfake detection, Anomaly detection | Medium | Arms race dynamics | Active deployment but limited |

| Technical - Privacy | Differential privacy, Federated learning | Medium-High | Utility costs, Complexity | Growing deployment |

| Technical - Safety | Constitutional AI, RLHF | Medium | Incomplete, Research ongoing | Recent deployment |

| Regulatory - Privacy laws | GDPR, CCPA | Medium-High | Enforcement challenges | Active in jurisdictions |

| Regulatory - AI-Specific | EU AI Act, Sector rules | Unknown | Early implementation | Emerging |

| Regulatory - Content moderation | Platform policies, Co-regulation | Low-Medium | Inconsistent, Capture risk | Active but inadequate |

| Organizational - Ethics programs | Review boards, Impact assessments | Low-Medium | Variable commitment | Mixed adoption |

| Organizational - Transparency | Audits, Reporting, Documentation | Medium | Access barriers, Standardization | Growing adoption |

| Social - Education | AI literacy, Media literacy | Medium (long-term) | Scale challenges, Time lag | Early stage |

| Ecosystem - Coordination | Standards, Information sharing | Medium | Cooperation barriers | Early stage |

Mitigation effectiveness summary.

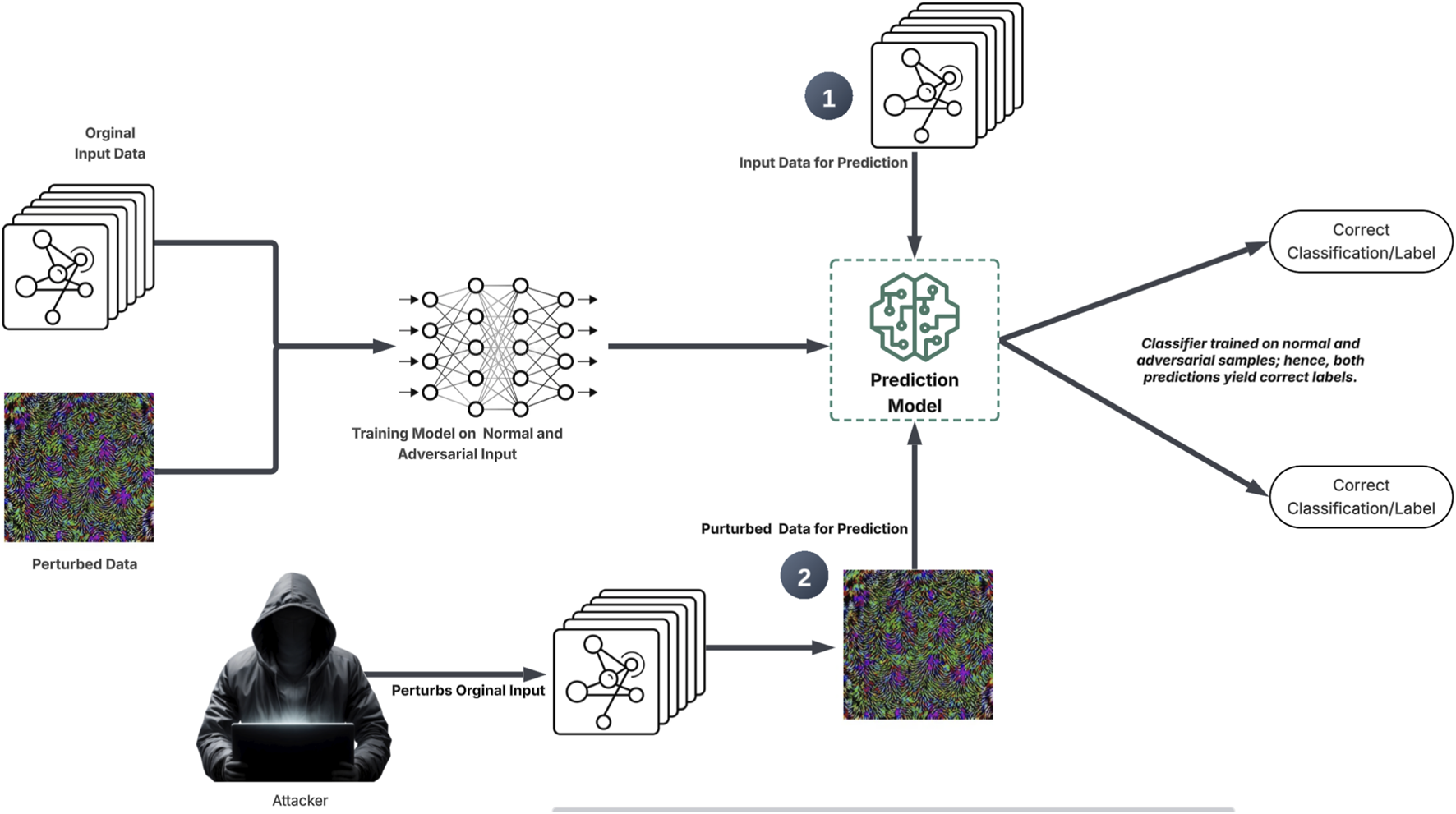

6.1 Technical countermeasures

Adversarial robustness techniques aim to improve the resilience of machine learning models against manipulative inputs. Adversarial training, which involves augmenting training datasets with adversarial examples (as shown in Figure 6), has demonstrated moderate effectiveness in enhancing robustness against known attacks; however, it struggles against adaptive adversaries and novel attack methods (Madry et al., 2018). This approach incurs significant computational costs that scale with the complexity of the threat model and often involves trade-offs between accuracy and robustness. Consequently, it is most suitable for high-value targets where computational overheads are acceptable.

FIGURE 6

Adversarial training.

Defensive distillation, which trains models with softened probability distributions to smooth decision boundaries, initially appeared promising (Papernot et al., 2016). While it may provide a layer of defense-in-depth, it is insufficient when deployed in isolation considering adaptive attacks. Input preprocessing methods, such as denoising, feature squeezing, or JPEG compression, can neutralize certain perturbations (Guo et al., 2017), yet these techniques degrade legitimate inputs and are easily circumvented by adaptive attackers.

Certified defenses also offer provable robustness guarantees within specified perturbation bounds, providing high theoretical value but with substantial practical limitations, including reduced accuracy and significant computational requirements (Cohen et al., 2019). Overall, no single technique currently provides comprehensive protection, and a defense-in-depth strategy combining multiple approaches represents the most viable option, albeit with persistent real-world limitations.

Apart from these, deepfake detection technologies have emerged to address the proliferation of synthetic media. Biological signal analysis, which detects irregularities in eye blinking, pulse, or breathing patterns, was moderately effective against early deepfakes (Wang et al., 2019) but is increasingly circumvented as generation techniques improve. GAN fingerprint detection can identify model-specific artifacts left by generative networks (Yu et al., 2019), proving useful for forensic attribution of known generators; however, it fails against unseen generators and adaptive attacks.

Temporal consistency analysis exploits frame-to-frame inconsistencies in video deepfakes, offering moderate effectiveness, particularly for video contents (Sabir et al., 2019). However, its utility diminishes as generation methods evolve. Multimodal inconsistency detection evaluates audio-visual synchronization and semantic coherence (Mittal et al., 2020), showing promise against poorly constructed deepfakes, though high-quality content often maintains consistency. Blockchain and cryptographic authentication can create verifiable chains of custody for authentic media (Hasan and Salah, 2019), providing strong authenticity guarantees but requiring adoption at the point of capture, limiting applicability to existing media.

Collectively, detection approaches face an adversarial co-evolution, suggesting that proactive authentication mechanisms may prove more effective than reactive detection, albeit requiring substantial infrastructure development.

Privacy-preserving machine learning approaches, including differential privacy, federated learning, homomorphic encryption, and secure multi-party computation, aim to protect sensitive data while maintaining analytical capabilities. Differential privacy offers strong theoretical guarantees by introducing calibrated noise, though it necessitates careful parameter tuning to balance privacy and utility (Dwork and Roth, 2014). Federated learning allows decentralized training, reducing risks associated with centralized data storage (McMahan et al., 2017), but remains vulnerable to some inference attacks and incurs communication overhead.

Homomorphic encryption enables computation on encrypted data, providing theoretically strong privacy protection (Rahman et al., 2020). But this may be computationally prohibitive for complex operations. Secure multi-party computation facilitates joint computation without revealing individual inputs, offering robust privacy guarantees at the cost of significant communication and computational requirements. Overall, privacy-preserving techniques present effective protection but involve trade-offs in utility, performance, and implementation complexity.

In addition, AI safety and alignment techniques focus on guiding model behavior to reduce harmful outputs. Bai et al. (2022) came up with “Constitutional AI”, a method for training a harmless AI assistant through self-improvement, without human intervention to identify harmful outputs. It incorporates explicit principles to steer decisions, showing potential in mitigating undesired outputs but requiring careful selection of values. Reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF) also leverages human preferences to improve alignment (Ouyang et al., 2022) yet depends heavily on feedback quality and may inherit labeler biases.

Red teaming systematically probes system vulnerabilities (Perez et al., 2022), enabling targeted mitigation, but cannot exhaustively identify all risks and is expensive. Interpretability and explainability methods aid in understanding model decision-making (Molnar et al., 2020), which is valuable for building trust and identifying potential issues; however, explanation quality varies and post-hoc interpretations may be misleading. While these techniques advance safety, they remain incomplete, underscoring the necessity of complementary approaches for high-stakes applications.

6.2 Regulatory and policy interventions

Regulatory and policy interventions constitute a foundational layer in mitigating AI risks, particularly those related to privacy, accountability, and systemic harm. Data protection and privacy regulations establish essential frameworks for mitigating AI risks. The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in the European Union exemplifies comprehensive privacy protection (European Parliament and Council, 2016), though enforcement challenges, jurisdictional limitations, and compliance burdens persist. Sector-specific regulations, such as HIPAA, GLBA, and COPPA, provide targeted protection for sensitive contexts but create fragmented coverage and may not fully address AI-specific risks.

In response to these limitations, AI-specific regulatory initiatives have emerged to address the unique challenges posed by AI systems. The EU AI Act represents a pioneering attempt at comprehensive, risk-based AI regulation (European Commission, 2024), though its full effectiveness remains uncertain given ongoing implementation. Algorithmic accountability requirements, including audits, impact assessments, and transparency obligations, enhance visibility into AI systems but require technical expertise and standardization. While disclosure mandates (like informing users when AI-generated content is present), contribute to transparency, they fall short of preventing harm and often encounter challenges in enforcement and compliance. Overall, AI-specific regulatory frameworks remain fragmented and incomplete, necessitating global coordination that balances innovation with protective measures.

Beyond formal regulation, content moderation and platform governance constitute additional layers of policy intervention. Platform self-regulation involves companies enforcing policies on AI-generated content, disinformation, and harmful material, with effectiveness varying across platforms. Proposals to reform Section 230 in the United States aim to adjust intermediary liability, though the potential impacts remain uncertain (Kosseff, 2019). Co-regulatory approaches, combining industry self-regulation with government oversight, such as the United Kingdom Online Safety Bill, may balance flexibility with accountability but require sustained political will and operational capacity. AI both amplifies the challenges of content moderation and offers potential solutions, indicating that multi-stakeholder governance is essential.

International cooperation is critical for addressing AI risks that transcend borders. Initiatives such as AI safety summits and agreements, exemplified by the Bletchley Declaration (i.e., a global agreement signed by 28 countries and the EU to foster a shared understanding of the risks and opportunities of advanced AI), facilitate shared understanding but remain non-binding and vulnerable to geopolitical tensions. Arms control frameworks propose restrictions on autonomous weapons and offensive cyber-AI, offering potential efficacy if adopted and enforced, though verification and enforcement challenges persist. International standards and best practices offer guidance on AI safety and security, promoting interoperability across systems. However, adherence is typically voluntary, and these standards often struggle to keep pace with rapid technological advancements. While global collaboration is essential, it remains inadequate in fully addressing the fast-evolving risks associated with AI.

6.2.1 AI risk governance frameworks

Within this regulatory and policy landscape, AI risk governance frameworks play a critical complementary role by translating high-level regulatory goals into structured principles, processes, and operational guidance. Unlike legally binding regulations, these frameworks are designed to support organizations in identifying, assessing, and managing AI risks throughout the system lifecycle.

The NIST AI Risk Management Framework (2023) adopts a practical, implementation-oriented approach focused on organizational risk management in the United Kingdom (Tabassi, 2023). It structures AI risks around core trustworthy AI characteristics, including validity and reliability, safety, security and resilience, accountability and transparency, fairness with managed bias, and privacy enhancement. By emphasizing continuous risk assessment, governance integration, and lifecycle management, the NIST RMF provides actionable guidance well suited for organizational adoption across diverse sectors.

At a global level, the OECD AI Principles (2019) offer a high-level values-based framework adopted by 42 countries, covering inclusive growth, human-centered values, transparency, robustness and safety, and accountability (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2019). These principles provide important normative foundations and have achieved broad international consensus.

Multi-stakeholder governance initiatives further extend these efforts. The Partnership on AI, 2021 developed a framework emphasizing responsible AI development across eight impact areas, including safety and robustness, fairness and non-discrimination, transparency and accountability, privacy and security, societal and environmental wellbeing, human control and autonomy, professional responsibility, and the promotion of human values (Partnership on AI, 2021). By integrating perspectives from academia, industry, civil society, and policymakers, such frameworks aim to bridge ethical principles with real-world deployment challenges.

Building on some of these principles, the SAFE framework introduces a unified, metrics-driven approach for AI risk management and compliance (Giudici and Kolesnikov, 2025). It organizes AI governance around four pillars: Sustainability (robustness against adversarial attacks and operational resilience), Accuracy (correct predictions under varying conditions), Fairness (equitable treatment across demographic groups), and Explainability (transparent and interpretable outputs). Unlike prior approaches that evaluate these dimensions separately, SAFE employs a mathematically grounded, integrated metric using Lorenz, dual Lorenz, and concordance curves to evaluate AI performance consistently across all four dimensions. By providing a single interpretable score, SAFE facilitates risk monitoring, operational compliance, and trade-off evaluation, making it a practical tool for organizations, developers, and regulators to mitigate AI risks proactively.

For tackling risks associated with Agentic AI systems, technical threat models have been developed alongside these major frameworks. The MAESTRO (Multi-Agent Environment, Security, Threat, Risk, and Outcome), threat model provides a structured approach to identifying vulnerabilities in agentic AI systems across seven key dimensions such as model manipulation, adversarial inputs, privilege escalation, supply-chain compromise, training data poisoning, robustness failures, and output integrity issues (Huang, 2025). This technical threat modeling approach complements risk frameworks by focusing specifically on attack surfaces and defensive strategies for autonomous AI systems.

While the above comprehensive frameworks provide broad coverage, some domain-specific frameworks also address unique risks in specialized contexts. The WHO Ethics and Governance of AI for Health framework identifies health-specific concerns including medical data privacy in AI-assisted diagnosis, algorithmic bias in health resource allocation, and AI-enabled health misinformation (World Health Organization, 2021). Moreover, emergence of agentic AI systems has prompted development of specialized threat models. In biosecurity, frameworks address dual-use risks where AI capabilities for beneficial biological research can be misused for designing harmful biological agents or automating synthesis of dangerous compounds, effectively lowering technical barriers for bio-threat development (de Lima et al., 2024; Trotsyuk et al., 2024). The United Kingdom’s AI Security Institute (AISI) has developed safety case frameworks specifically for risk mitigation in biomedical research contexts, emphasizing structured argumentation for safety claims in high-stakes domains.

Together, these governance frameworks complement regulatory interventions by offering principled, operational, and technical approaches to managing AI risk. While none fully address the breadth of AI misuse in isolation, their combined application provides essential scaffolding for mitigating risks identified throughout this review.

6.3 Organizational and social interventions

Organizational ethics programs and responsible AI frameworks play a crucial role in internal governance. Ethics review boards can identify and address ethical concerns prior to deployment, but their effectiveness is contingent on institutional authority and resources. Responsible AI frameworks, such as Microsoft’s RAI framework or Google’s AI Principles, provide structured guidance for ethical AI development, though implementation quality varies. Bias auditing and testing help detect discriminatory system behavior, enabling targeted mitigation, yet defining fairness metrics remains contested and costly. Thus, genuine institutional commitment, supported by external accountability mechanisms, is essential for efficacy (Reuel et al., 2025).

Education and awareness initiatives complement technical and regulatory measures. AI literacy programs educate the public on AI capabilities, risks, and critical evaluation of AI-generated content, fostering long-term societal resilience. Professional training for developers, policymakers, and domain experts enhances AI governance and responsible development, though rapid technological evolution challenges curriculum relevance. Media literacy and critical thinking programs further strengthen resilience against disinformation. While essential, educational interventions cannot provide immediate protection and require sustained investment.

Transparency and accountability mechanisms are vital for monitoring AI deployment. Algorithmic impact assessments evaluate potential societal consequences before deployment (Reisman et al., 2018), while independent algorithmic auditing identifies issues post-deployment (Raji et al., 2020). Transparency reporting enables public scrutiny of system development and performance, though concerns regarding trade secrets, information overload, and technical complexity persist. Legal protections for whistleblowers facilitate internal accountability, provided they are genuinely enforced (Brown and Lawrence, 2017). Overall, transparency and accountability mechanisms remain underdeveloped relative to AI’s societal impact and require urgent strengthening.

Despite growing mitigation efforts, significant gaps remain because many interventions are reactive, addressing known threats while adversaries continue to innovate. Offensive AI has access to resources comparable to defensive AI, enabling attackers to rapidly adopt the latest techniques and making it challenging for defenders to keep pace. Furthermore, policy verification and enforcement are often weak or inconsistent, and differences in regulations across jurisdictions create opportunities for regulatory arbitrage.

Compounding these challenges, AI’s rapid evolution continues to outpace regulatory, educational, and societal adaptation. Persistent technical problems, such as adversarial robustness and deepfake detection, lack comprehensive solutions, and conflicting stakeholder priorities make it difficult to balance innovation, security, and privacy, while the widespread accessibility of AI tools amplifies the challenges of scaling effective defenses. Together, these factors underscore the persistent and growing difficulties in anticipating, managing, and mitigating AI misuse.

7 Conclusion

AI technologies hold immense transformative potential, yet they also introduce significant technical, social, and systemic risks. This paper has critically examined existing mitigation strategies, revealing that while technical defenses, regulatory frameworks, and organizational measures provide partial protection, they are often reactive, fragmented, and limited against adaptive threats. The emergence of advanced capabilities such as multimodal models and autonomous agents further amplify these risks, highlighting the need for proactive, integrated, and multi-stakeholder responses. To support this effort, we introduced a comprehensive taxonomy that organizes AI misuse into nine primary domains, providing a structured framework for understanding the full spectrum of risks - from technical vulnerabilities to socio-technical harms. The case studies presented demonstrate that AI misuse has tangible, measurable impacts, disproportionately affecting marginalized populations and eroding trust in digital systems and democratic institutions.

The trajectory of AI development presents society with critical choices about the values embedded in technological systems and the governance structures that shape their deployment. While AI capabilities continue to advance rapidly, our collective capacity to govern these technologies responsibly remains significantly underdeveloped. Addressing AI misuse requires moving beyond reactive, fragmented approaches toward proactive, integrated strategies that recognize the deeply socio-technical nature of these challenges. The stakes are high: unchecked misuse threatens privacy, security, democratic integrity, social equity, and human autonomy. Yet, with coordinated effort across technical, policy, and social domains, it remains possible to steer AI development toward beneficial outcomes that respect human rights, promote fairness, and enhance societal wellbeing.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

NS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. FI: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review and editing. KA-R: Methodology, Writing – review and editing. ÁM: Supervision, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This study is supported by Research Incentive Funds (activity codes: R23064, R21096), Research Office, Zayed University, Dubai, United Arab Emirates.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Some sections of the text have been rephrased using ChatGPT to enhance clarity and readability while maintaining the original meaning. All outputs generated were thoroughly reviewed and edited by the author(s) to ensure accuracy.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1.^DeepFaceLab is a leading software for creating deepfakes

References

1

Acemoglu D. Restrepo P. (2020). Robots and jobs: evidence from US labor markets. J. Political Econ.128 (6), 2188–2244. 10.1086/705716

2

Agile-index.ai (2025). Agile-index.ai. Available online at: https://agile-index.ai/publications/2025.

3

Ajder H. Patrini G. Cavalli F. Cullen L. (2019). The state of deepfakes: landscape, threats, and impact. Deeptrace. Available online at: https://scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=3622764.

4

Angwin J. Larson J. Mattu S. Kirchner L. (2016). Machine bias: There’s software used across the country to predict future criminals. And it’s biased against Blacks. ProPublica. Available online at: https://www.propublica.org/article/machine-bias-risk-assessments-in-criminalsentencing.

5

Apruzzese G. Colajanni M. Ferretti L. Guido A. Marchetti M. (2018). “On the effectiveness of machine and deep learning for cyber security,” in 10th international conference on cyber conflict (CyCon), 371–390. 10.23919/CYCON.2018.8405026

6

Autor D. H. (2015). Why are there still so many jobs? The history and future of workplace automation. J. Econ. Perspect.29 (3), 3–30. 10.1257/jep.29.3.3

7

Bai Y. Kadavath S. Kundu S. Jones A. Kaplan J. (2022). Constitutional AI: harmlessness from AI feedback.

8

Barocas S. Selbst A. D. (2016). Big data's disparate impact. Calif. Law Rev.104 (3), 671–732. 10.2139/ssrn.2477899

9

Biggio B. Corona I. Maiorca D. Nelson B. Šrndić N. Laskov P. et al (2013). Evasion attacks against machine learning at test time. Adv. Inf. Syst. Eng., 387–402. 10.1007/978-3-642-40994-3_25

10