- 1DISCo - Dipartimento di Informatica, Sistemistica e Comunicazione, Universita' degli Studi di Milano-Bicocca, Milan, Italy

- 2Department of Computer Science, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Introduction: Concerns over privacy and data collection have become increasingly important since software is everywhere. Apps such as Google Maps collect data on users' whereabouts, interests, habits, and more.

Method: Data collection practices are typically delivered through a privacy policy. To evaluate the effectiveness of privacy policies, we focus on Google Maps as a concrete and widely used app example. Our study explores user perspectives on privacy concerning the Google Maps app, and combines them with prior research to assess user awareness of data collection and privacy. To achieve our objective, we use a survey containing 19 questions (aligned with the themes explored in the state of the art, i.e., privacy policy awareness, users' habits regarding privacy, the effectiveness of privacy policies). The sampling strategy is a convenience one to receive the greatest number of responses. The received answers are analyzed by focusing on the readability and understandability of privacy policies.

Results: The output indicates that privacy policies are complex, require a significant amount of time to be read, hard to understand by most of the users, and, hence, ignored by most of the users.

Discussion: The various reasons why privacy policies are ineffective and what causes users to avoid reading them are summarized and discussed. Potential solutions to the inefficacy of privacy policies are outlined and areas/hints for further research are revealed.

1 Introduction

As technology advances at a rapid pace, increasingly important challenges emerge, too. This is particularly visible within privacy and data collection: with every new technological innovation users are confronted with new privacy issues that require attention. For example, we experience the advancements of Internet of Things (IoT) that may improve our lives on many levels. As we embrace the benefits of IoT, we must also recognize the increasing risk to individual privacy. In this context, a balance must be found to ensure that regular users do not have their fundamental privacy rights compromised.

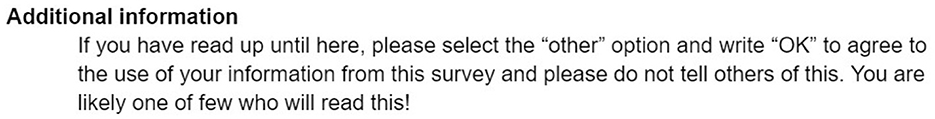

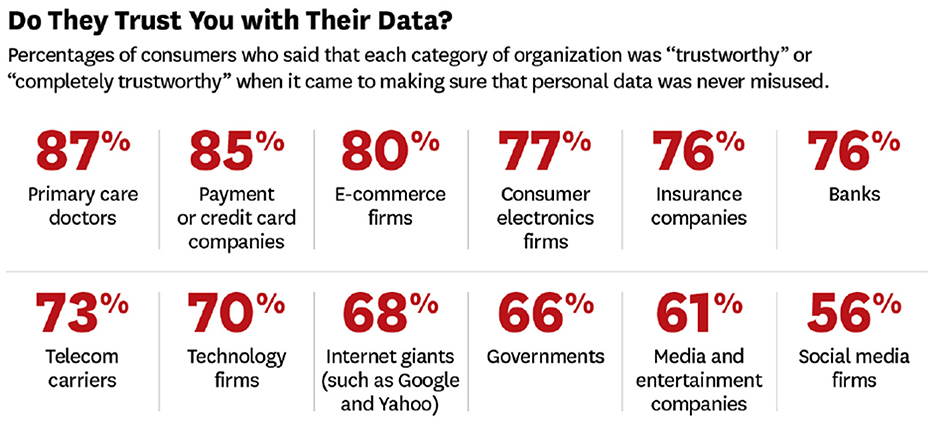

Privacy policies are legal documents that detail how the collection, usage, and retention of data is processed by a company (Costante et al., 2012; Wagner, 2023). Throughout history, privacy policies have changed to comply with new regulations such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)1; with these changes comes an increase in length and complexity of privacy policies that give them a reputation for being difficult to read and understand (Wagner, 2023). From complicated legal jargon to lengthy policies, researchers and companies have searched and tested for ways to improve communication with users—aspect explored in this paper in Section 2. Companies such as Google and Meta collect—daily—vast amounts of data from users. These companies successfully access data, e.g., photos, files, location, social interactions, and more that are in the user devices. Some of this data collection may be unbeknownst to users, e.g., Google Timeline collects location, date, and time while the phone has power (Williams and Yerby, 2019). The importance and significance of such data collection arises from Google's lack of transparency regarding data acquisition and tracking that is beyond the perceived control that users have on the devices they carry in their pockets every day. Companies in general, and Google in particular, have made several modifications in the policies in response to the public exposure of their privacy inconsistencies that led user understanding complicated. However, most users are in the dark about their data and how it is (or may be) used. For example, Figure 1 shows the percentage of people that are aware of their data being collected by companies.

Figure 1. Awareness of data collection in 2015 (Reproduced with permission from Timothy et al., 2015).

An incredibly low percentage of users realize they are sharing so much information with companies. How is this possible? Personal information such as location and chat logs is gathered by companies, and users should be aware of this (being considered as common knowledge). This implies that there is a severe mismatch between user understanding on one side and company delivery of data collection and use on the other side. The most common way to become more aware of data collection is to read the privacy policies; however, they are time-consuming and difficult to read and understand.

Google's privacy policy is a 32-page document2 detailing the collection and use of users data. The introduction of the privacy checkup tool on August 28, 2020 (Google, 2025b) shows an increased effort by Google to inform users of their rights, but to fully grasp their privacy rights, users must read (and comprehend) the policy. Using Google Maps does not limit users data to just the app, but also means users information can be shared throughout the whole Google service; this can be GPS, IP address, or activity on Google services, among many other things. More important, Google can change its privacy at any time and inform its users through a notification (Google, 2025b). The effectiveness of notices such as this is also discussed in this paper.

The usage of Google Maps has skyrocketed: Google Maps has reached over 10 billion downloads with 17 million reviews on the Google Play Store and 5.2 million reviews on the App Store as of May 29, 2023. Users of Apple devices opt to use Google Maps rather than Apple Maps, which has only around 17,200 reviews and a 2.7-star rating as opposed to 5.2 million of Google Maps with a 4-star rating (AppStore, 2025a,b; Google, 2025a). Furthermore, it is reported through a survey that 54% of mobile phone users navigated using Google Maps in 2021 (EnterpriseAppsToday, 2025). With such a prominent use rate, Google should handle privacy very carefully and be transparent due to the immense amount of data collected from each individual. For this reason, this paper investigates the following research questions (RQ) with a focus on Google Maps due to its popularity:

RQ1: How informed are users of their privacy rights and the use of their data through privacy policies?

RQ2: How do we raise awareness about privacy and personal information shared with smart mobility apps like Google Maps?

This paper investigates the effectiveness of privacy policies and user perspectives on the above mentioned privacy policies. To answer the two RQ, research papers on many aspects of policies were analyzed and their results combined (see Section 2 and Section 5) and a questionnaire was drafted and sent to collect user perspectives on privacy policies (see Section 3). The aim is to explore privacy policies and evaluate their effectiveness and provide insight into the awareness of users having a Computer Science background (e.g., working in our department) and users with other professional backgrounds. Lastly, this paper discusses findings from the survey and literature review to establish an idea of where privacy awareness is at, particularly in Google Maps (see Section 4, Section 6, and Section 7). By providing existing and upcoming solutions that may assist in the greater awareness of data collection, we aim to take a step closer to helping users understand their fundamental rights to privacy and prevent any abuse of these rights (see Section 8 and Section 9).

To summarize, the contribution of our paper consists in:

• Exploring a user perspective on privacy awareness;

• Addressing topics explored across various research papers and providing a comprehensive approach to understanding user engagement with privacy policies and data collection practices;

• Designing a survey with questions directly rooted in existing literature;

• Using Google Maps as a concrete and widely used app to evaluate the effectiveness of privacy policies;

• Reviewing facts from the main public daily news;

• Providing solutions for privacy awareness and understanding.

2 Literature review

Previous studies focused on different aspects concerning privacy policies—from investigating if users read or not the policies to if they understand (or comprehend) such policies or not. Understanding or comprehension may be translated into the users' ability to understand how a company collects, uses, stores, and shares their personal data, as outlined in a privacy policy (e.g., a legal document) (Xiaodong and Hao, 2024; Kununka et al., 2017). In this section, we discuss some of these aspects meaningful for our study.

2.1 Do users read privacy policies?

A study of 64 participants (forming the non-default group) was conducted in an experiment by (Steinfield 2016) where each participant was asked to agree to the terms and service without being given the privacy policy by default. Of the 64 participants, 50 (79.7%) agreed without opening the privacy policy at all and 14 (20.3%) opened the link (Steinfield, 2016). On the contrary, another experiment in the same study with a different group of 64 participants (forming the default group) for whom the privacy policy was shown by default, yielded surprising results. The average time the participants spent reading the policy was 59,196.11 ms, indicating that the policy was not ignored, and considerable time was spent reading it at close to 1 min (Steinfield, 2016). This suggests that when policies are presented by default, they are perhaps more likely to be considered and less likely to be skipped.

Furthermore, the results of Steinfield's experiment also yield another significant finding. Despite consciously clicking on the link to read the privacy policy, those who did so spent ~2.5 times less time reading than the participants who were presented with the policy by default. This is more specifically investigated using eye-tracking in which the findings show that within six of the nine paragraphs in the policy, findings through dwell time and fixations show that the default group read the policy more carefully; however, there was no significant difference within the remaining paragraphs in terms of the other three paragraphs (Steinfield, 2016).

Steinfield concludes this experiment with three main findings:

• First, if the policy is presented by default, users will spend more time and effort reading it.

• Second, if the option exists to accept the terms and conditions without having to read the policy, users tend to accept without reading it.

• Third, despite taking the time to click the link, users who do so tend to spend less time and effort reading the policy.

With these three findings, Steinfield (2016) discusses the possibility for improvements in the “way we manage our engagement with online services,” and that “users can be informed of their rights by framing the information differently, specifically by designing website default options involving the presentation of privacy policies.” Steinfield's study points to the possibility of better privacy policy practices in order to help users gain a better understanding and serves as significant knowledge to reflect on in lieu of the next papers.

Geoprivacy concerns information related to the users' geographic location, which is maybe the most common and relevant personal information collected by today's applications (Keßler and McKenzie, 2018; Zhang and McKenzie, 2023) (including Google Maps). As mentioned in the geoprivacy manifesto (Keßler and McKenzie, 2018), "users often share their current location unknowingly". However, addressing geoprivacy, also in privacy policies, is not a trivial task: it has to consider many perspectives behind the personal, social, and technological ones (Huan Li and Kwan, 2025).

2.2 Why do users not read privacy policies?

A different study by Sheng and Simpson (2014) explored the various reasons why users do not read privacy policies by asking participants to explain their reasons. This is combined with a website created specifically for the experiment, where participants are asked to navigate to find a specified item. The website was created to simulate a typical online experience, and, most importantly, it contains a privacy policy. The participants are then asked to answer a questionnaire about why they do and not do read privacy policies. Focusing on the results of why participants do not read these policies, the largest group of individual responses consists in “No Time/Interest” with 38.7% of respondents stating similar phrases such as “do not have time,” “no interest,” and “do not think about it.” The next most common response is at 25.8% citing that things such as “privacy policies are long and take too much time to read” due to how complex they are (Sheng and Simpson, 2014). Sheng and Simpson's study gives insight into the reasons why users in this study and possibly Steinfield's study might not read privacy policies. A lesser but significant statistic from Sheng and Simpson (2014) is that 12.9% of respondents do not read the policy because they trust the website. This idea of trusting the company or website can have serious implications, especially concerning companies such as Google due to being a monolith in the tech world and “one of the largest and most powerful multinationals on earth” (Smyrnaios, 2019). A lack of awareness can potentially be created through this trust which will be further explored later in this paper (see Section 6).

2.3 How long does it take to read privacy policies?

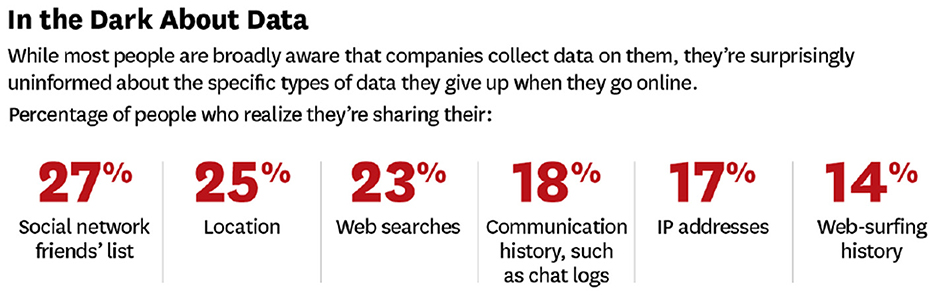

To explore the time aspect, McDonald and Cranor analyzed the costs of reading privacy policies (McDonald and Cranor, 2008). The premise of the paper is to consider the time spent reading privacy policies as a form of payment; in order for users to understand the collection and use of their data, they must use their time to conduct research into the policy (McDonald and Cranor, 2008). McDonald and Cranor explore the question of how much of the users' time is worth if they read the policy of sites used once a year. This includes aspects such as a cost/benefit analysis to determine the price of the users' time based on the idea that privacy policies are likely not to be read if the cost is high (as mentioned in McDonald and Cranor, 2008). By using a rate of 250 words per minute as reading speed, and policies found on the 75 most popular websites, McDonald and Cranor discovered that a total time of between 8 to 12 min is required to read the policies (see Figure 2). Eight minutes are spent reading short policies of around 2,071 words up to 12 min for longer policies of around 3,112 words; however, it is mentioned that these estimates may be low due to the difficult jargon and possible slower reading speeds (McDonald and Cranor, 2008).

Figure 2. Average time to read policies by average readers (Adapted from McDonald and Cranor, 2008).

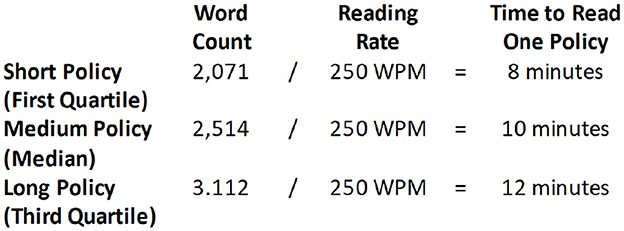

Further, McDonald and Cranor have asked the participants to read six different policies of various lengths: a short one of around 1,000 words, four medium of around 2,500 words, and a long one of around 6,400 words. The median time to read one policy ranged from 18 to 26 min. The lowest was 12 min; while the highest was 37 (Figure 3). Furthermore, there are limitations to the results of McDonald and Cranor's (McDonald and Cranor, 2008) experiment referenced by this paper and Sheng and Simpson's paper (Sheng and Simpson, 2014), namely people generally find longer policies time-consuming and likely do not properly read them.

Figure 3. Time for average readers to skim policies of different lengths (Adapted from McDonald and Cranor, 2008).

McDonald and Cranor (2008) conducted a second experiment where participants are asked to skim the policy to answer a few questions such as “Does this website use cookies?”. They measured the time to answer the questions and estimated the time to answer one question. This results in a low estimate of 3.6 min and a high estimate of 11.6 min with a point estimate of 6.3 min. The significance of this research data is furthered when combined with the number of websites visited in a year, resulting in an estimate of 54 billion hours needing to be spent nationwide in the United States for reading privacy policies. This equates to a presumed $781 billion per year, with each user spending $3,541 worth of their time and 201 h per year (McDonald and Cranor, 2008). These numbers suggest the results of Steinfeld's research are reasonable and the cost of reading the policy can outweigh the benefit. Additionally, even if users do read privacy policies, the practice can be considered unsustainable or impractical. Considering this study was conducted in 2008, it has significant implications as privacy policies have become considerably longer due to enhanced legislation and technology. A recent study (Wagner, 2023) found that the typical length of time required to read an average policy amounted to 17 min. However, for the top-10 policies, the average reading time was extended to 23 min with the longest being Microsoft's: an incredible 152 min to read (Wagner, 2023).

McDonald and Cranor (2008)'s study factors in the length of privacy policies and opens questions regarding the effect of this length and the implications from policies of various sizes. If the lengths in McDonald and Cranor (2008) have an impact on reading time, the following question should be considered: does shortening the length or delivery of privacy policies have benefits? Results from Gluck et al. (2016) indicate that short-form privacy notices that condense information within policies are effective in increasing privacy awareness compared to the generic privacy policy. However, if the condensation of the information leads to removing common privacy practices that users may already be aware of, then this consequently decreases awareness (Gluck et al., 2016). Gluck et al. also explore how framing (positive or negative) can affect awareness, but data shows that framing has no significant effect on awareness. The limitation of Gluck et al. (2016) is the difficulty to generalize these results due to different participants' levels of attention when reading. Moreover, the privacy policy belonged to a single company. Despite this, the results insinuate that short-form privacy notices can be further researched as a possible alternative to improve understanding and awareness.

2.4 Do users understand privacy policies?

To investigate the discrepancy between user and expert understanding of privacy policies, Reidenberg et al. (2015) compared the level of understanding among three categories:

• Privacy experts,

• Law and public policy graduate students,

• Ordinary Internet users.

The groups are shown the privacy policies of e-commerce, news, and entertainment companies, and tested on the contents of these policies with regards to data use, collection, and retention (Reidenberg et al., 2015). For example, questions are asked if personal information (contact, financial, location, health) is being collected. The answer choices indicate:

• NO—the policy explicitly states that no personal information is collected;

• YES—the policy explicitly states that personal information is collected;

• UNCLEAR—the policy does not explicitly state whether personal information is or is not collected, but the selected sentences could mean that such information might be collected;

• NOT APPLICABLE—not addressed by the policy.

The median level of agreement across all policies for the same question is calculated to reflect the group consensus on an answer choice. A median value of 100% means that all group members agree on the same answer choice and share the same understanding of the privacy policies. Despite being experts, an agreement could not be reached on the interpretation of the policies. Moreover, the implications described in Reidenberg et al. (2015) suggest that privacy policies are a poor way of informing users and could be considered misleading especially if this is intentional, leading to a legal problem in terms of deceptive practices. The legal jargon and complicated policy also lead to a complete mismatch of user and expert understanding. Reidenberg et al. discovered that while regular users perform worse than experts in the category of data practices, they agree on areas where experts disagree. More importantly, regular users may be misunderstanding many parts of the policies that are ambiguous (whether this ambiguity is intentional or not)

The Flesch Reading Ease metric (Flesch, 1981) is used to determine how difficult a text is to read. The scores have a range of 0–100 and website privacy policies have a score of 39.83 which implies that they would fail to meet legal standards (e.g., in Florida) if they were insurance policies (Libert, 2016). Libert (2016) explains that the most readable policy is from Facebook, at 48.94, and the lowest is at 18.42 which would make it less readable than articles within Harvard Law Review. Considering how important privacy policies are, the score should be quite high so the average user can read and understand them. Libert illustrates the sharp disparity between approaches to privacy policy and user needs and understanding. The idea that if online privacy policies were insurance policies, they would not meet fundamental legal requirements, provides reasonable need for change in the interest of privacy for users.

The issue of privacy policy comprehension is further addressed in another paper (Korunovska et al., 2020) and results show that over 50% of users are unable to fully understand the policy. Korunovska et al. (2020) discovered that this happens when users are presented with a simple privacy policy that focuses on aspects that typical users would find important which leaves out details for better understanding. An equally important factor is that users are tested on their attention as well as having the opportunity to go back and look at the policy again (Korunovska et al., 2020). The main conclusion from Korunovska et al. is that despite policies being transparent, simple, and prominent, this does not always lead to user understanding. The significance of this finding is that it somewhat contradicts the conclusions found in Steinfield (2016), McDonald and Cranor (2008), and Gluck et al. (2016) which conveys the highly nuanced nature of this subject and perhaps why it is complicated to find a solution. It is possible that the reason for the contradiction is due to the methodology in Korunovska et al. (2020) which shows users what they would find most useful in a policy and condensation of information—which could lead to removal of some information. It is previously found in Gluck et al. (2016) that the removal of information leads to decreased awareness and could be a limitation. Likewise, Korunovska et al. used a sample of Austrian Internet users and expectations of privacy can vary between population demographic and the privacy regarded only in Social Networking Services (SNS).

2.5 Do privacy policies offer the information desired by users?

Assuming that users can completely comprehend what is present in the privacy policies, do these policies answer all their questions and needs? The results of a web-based survey in an experiment conducted in 2005 seem to point out that website privacy policies are misaligned with the privacy values of users (Earp et al., 2005). Earp et al. (2005) discovered that users are most concerned with the transfer, notification /awareness, and storage of data, which are similar to the parts of privacy policies that participants are tested on in Reidenberg et al. (2015). However, Earp et al. (2005) collected data from the United States where people have different attitudes on privacy than in other parts of the world. Furthermore, the paper can be considered severely outdated due to a publishing date in 2005. Throughout a span of 20 years, many changes may have occurred in user attitudes and how privacy policies are created. One such important change occurred on May 25, 2018, known as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). This legislation gave birth to laws regarding the processing, storing, and managing of data for people in the European Union (Li et al., 2019). The motivation of this legislation was due to the rise in digital technologies that bring a slew of privacy challenges that the EU wished to address. Li et al. (2019) explain that 68% of American companies will be spending an estimated $1 million to $10 million in order to fulfill the new requirements and likely cause developing new technologies to be more expensive due to stricter regulations regarding data processing. More importantly, GDPR empower residents of the EU additional rights that allow users to request the specifics of what their data is used for and possibly delete their data if they are unsatisfied with how it is being handled (Li et al., 2019). Regulations and more awareness regarding the existence of privacy policies can have a large impact on them, especially over 20 years. Therefore, the expectation would be that privacy policies have improved in both form and function and should be better suited to answer users' privacy questions after learning from legislations like the GDPR.

Apps on the App Store and Google Play Store use a privacy label in order to be transparent and help users understand how their data is collected and used and, therefore, they should help user understanding (Apple, 2025). Unfortunately, a study in February 2023 found otherwise (Zhang and Sadeh, 2023). According to Zhang and Sadeh (2023), iOS and Google Play privacy labels could answer only 38.6% and 43.2% of question themes, respectively, that are selected from a data set of question themes similar to those of users on an App Store. Gardner et al. (2022)'s findings also help illustrate that despite calls for standardized privacy labels that help summarize privacy information, there is still a mismatch between user privacy concerns and the provided privacy notices (Zhang and Sadeh, 2023). Moreover, Zhang and Sadeh (2023) brings the attention to privacy labels only answering some question themes implicitly. This is important as mentioned in Reidenberg et al. (2015) that such practices, if intentional, are harmful. Fortunately, the silver lining is that although these privacy labels are not very effective, prior studies indicate that users enjoy the labels present in the App Store and Apple (see an example of a privacy label on App Store for Apple has taken a step forward to make privacy information more accessible and user friendly.

2.6 How is privacy information conveyed to users?

Privacy notices and labels are not the only methods of conveying privacy information to users. The use of Privacy Finders, Layered Notices, and Natural Language Format policies were tested and compared with comprehension, psychological acceptability, and demographics tests (McDonald et al., 2009; Schaub et al., 2017). Layered notices are privacy policies with expandable headings that lead to more information to provide a better experience. Privacy Finders provide context and uniform presentation to improve readability (McDonald et al., 2009). McDonald et al. (2009) found that Layered and Privacy Finder formats showed slight improvements in answer times and Privacy Finder formats also showed some improvements in comprehension. In agreement with the prior papers discussed in this literature review, Schaub et al. (2017) also discovered that the time-consuming nature and privacy policies being away and not integrated into the systems causes them to be ineffective. Schaub et al. (2017) argued that privacy policies struggle due to the lack of synergy between the different legal and engineering departments, with designers and engineers creating the product and offloading the privacy policy to be addressed solely by the legal team. A more effective approach would be to work together and ensure privacy notices and controls are integrated seamlessly into the user's interaction process rather than a long and incomprehensible privacy policy (Schaub et al., 2017). Unfortunately, Shaub et al. recognize that this is a difficult process and requires the awareness of the ineffectiveness of current privacy policies and shift their efforts into making them more user friendly and in line with user needs.

To summarize, throughout this literature review, we have analyzed the issues with privacy policies (e.g., why users do not read privacy policies) and evaluations of different types of policy notifications (e.g., how is privacy information conveyed to the users). We also attempted to find research on methods to improve privacy policies (e.g., do users understand privacy policies and do privacy policies offer the information desired by the users). Prior research shows that it is difficult to find a solution that can address all the highly nuanced and difficult issues presented by privacy policies. This literature provides many perspectives and background information that can assist in the interpretation of our survey results. We aimed to go a step further with our survey and asked users, for example, if they are aware of the personal information gathered by the apps, and how important is this information for them, or if they would prefer a simplified and more understandable version of privacy policies.

3 Our methodology

We used a survey-based research style to investigate the RQs:

RQ1: How informed are users of their privacy rights and the use of their data through privacy policies?

RQ2: How do we raise awareness about privacy and personal information shared with smart mobility apps like Google Maps?

In this study, we prepared a Google Survey3 with questions that aim to target aspects where users may not be aware of data being collected. Our objective is to map the level of users awareness about data collection and privacy policies.

This approach helps to gain an understanding of user perspectives, attitudes, and experiences with this topic.

3.1 Sample

The sampling strategy in this survey was convenience sampling in order to receive the greatest number of responses. The survey was sent out to sources with many students and young professionals. These sources contained people who shared the feature of being part of the younger generation and in touch with technology. The survey was first sent to a chat group of 259 computer science students in their last year of studies and professors. The survey was also sent out to a business network that contains many business and economics majors and startups. Finally, the survey was sent to a network of students at another university with major in various different subjects. The data collection lasted ~4 weeks.

3.2 Survey

The survey contains a total of 19 close-ended multiple choice questions containing pre-determined response options with an additional question at the end to allow participants to provide further insights or comments on this topic. The questions were selected based on prior research addressed in the Literature Review section. Furthermore, the questions were created based on the idea that time is important for participants, and too many questions will lead to a lack of motivation to complete the survey. So, in the interest of getting the most responses, the questions and answers had to suffer some detail.

The questions were first checked and validated by a group of 4 researchers (two assistant professors and two PhD students) and then sent to the users.

3.2.1 Link tracking and reading experiment

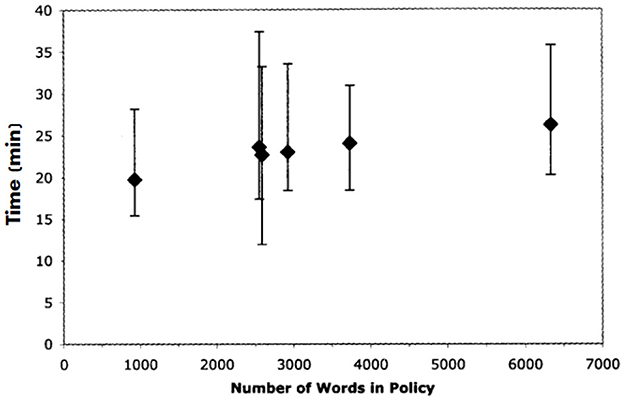

The first question of the survey simply asks for permission to use the provided data for research. However, there is also a hidden experiment within this question:

Q1: Please familiarize yourself with the way your data will be used in this survey by reading this policy.

The participant can accept, decline, or select other and type a feedback. A custom one page privacy policy was drafted using ChatGPT with the necessary information regarding the use of answers to the survey for research purposes. The policy is intentionally kept extremely short compared to privacy policies from Google to make participants more likely to read it. Within the privacy policy link, there is a tracker that counts the unique clicks to count how many people even click the link in order to read the policy. This policy exists also to follow ethical practices when conducting this experiment by explicitly asking users for their permission when using their data.

The second experiment in this question is to test how many people clicked the link and read the policy as well. Hidden in the bottom of the privacy policy is an additional section (see Figure 4).

This is present in hopes that the user has read or skimmed to the bottom of the privacy to find this section and inputs a separate response in the Other field and allows us to see who takes the time to open the link and reach the bottom of the custom privacy policy.

3.2.2 Demographic questions

The next two questions regard the demographic of participants. The first asks about age range, whether participants are under 18, between 18 and 24, or 25 and older. The second asks if participants are in the field of computer science. The purpose of these questions is to see if there is any correlation between age or field of work and privacy awareness based on the assumption that computer science respondents utilize or understand technology more.

3.2.3 Data collection and privacy policy questions

The questions target privacy policies, data collection, and the user perspective on them. The questions also bring focus to the Google Maps app and Google as a company and explore whether participant opinions differ in any way when considering privacy policies as a whole and specifically Google as a company.

4 Results

Our survey and its related results are summarized in the supplementary materials of this paper and discussed in the following. From the demographic point of view, the survey responses show that 93 out of 109 participants (85.3%) are between 18 and 24 years old and 10 (9.2%) are under 18; the smallest group counts 6 (5.5%) participants being 25 or older. From the background point of view, 40 (36.7%) participants are either working or studying computer science, while 69 (63.3%) have other backgrounds.

Through link tracking using the online Linkly (Linkly, 2023) service, the number of total unique clicks on the privacy policy is 19 out of the 109 participants. This results in ~17.4% of the participants taking the time to click the link without considering whether they read the policy or not. The number of responders who clicked the link and read or skimmed the policy (answering to the hidden question) numbered at a low 8 (7.3%) out of 109 participants. Specifically, five participants (12.5%) out of 40 with computer science background clicked the link and read the policy, while three (4.3%) out of 69 with other backgrounds.

The wide use of Google Maps is evident: 106 (97.2%) of participants report that they use Google Maps and only 37 (34.9%) use also Apple Maps. The use of mobility apps in general, e.g., Google Maps or Apple Maps is common practice, with 64 (58.7%) participants reporting that they always use mobility apps for uses such as navigation, check how busy a place is, or search for restaurants suggestions. Moreover, 41 (37.6%) participants indicate that they sometimes use mobility apps. In contrast, only 3 (2.8%) responders mentioned they rarely use these apps. Only one (0.9%) states that she/he never uses apps such as Google Maps and Apple Maps.

4.1 Are users aware of data collection in general?

Asked if they always read the privacy policy or terms of service for an app, none answered positively. Only one participant reads the policy most of the times. Nine (8.3%) participants stated they sometimes read privacy policies. 33 (30.3%) participants state that they rarely read policies, while 66 (60.6%) never read privacy policies before using an app. More specifically, the overwhelming majority of 96 (88.1%) participants responded that they never read Google Maps' privacy policy, with only 13 (11.9%) declaring they skimmed through it and not a single participant has familiarized with it. When it comes to re-reading privacy policies after changes, 79 participants (72.5%) revealed they never go back and read a privacy policy after changes. None declared that always reads the changes. Twenty-three participants (21.1%) rarely read policies and just 7 (6.4%) sometimes read them. To explore this further, participants were asked how important is privacy to them: 52 (48.6%) declared that it is somewhat important and 31 (29%) are neutral. Only 16 (15%) state that it is not important and even less 8 (7.5%) responded that it is very important, which shows that only few participants have very strong opinions on privacy.

This raises the question of whether users are aware of their data collection, use, and retention if many participants did not read privacy policies for navigation apps. The next question in the survey addresses this inquiry. Around half of the participants, i.e., 56 (51.4%) are aware of data collection and some of the data collected from them. Only three responders declared that they are not aware of any data collection. Moreover, nearly a quarter of users 27 (24.8%) understand that data is collected from them, but are unsure of what data. Despite most participants not reading privacy policies, 23 (21.1%) disclose they are aware of all data collected from them such as real time location when it comes to navigation apps. A further research step would be to investigate the user awareness about the implications of the combination of their collected personal data (e.g., location) with other data to profile them or to perform more complex analysis.

4.2 How aware are users of Google Maps data collection in particular?

Most participants, i.e., 68 (62.4%) are somewhat aware of personal information being collected and how it is possibly used, while only 14 (12.8%) declare they are fully aware of personal information being collected and how it is used. 27 (24.8%) are unaware and do not know what Google Maps does with their personal information.

Google offers privacy settings for users, but how well do regular users understand and use these features? Asked about whether they have adjusted their app settings to limit data collection, 60 (55%) participants answered positively with 36 (33%) stating they knew how to do it and 24 (22%) declaring that they had to find out how to. In contrast, 23 (21.%) revealed they did not limit data collection, but are aware of how to do so. Moreover, 26 (23.9%) responded that they are actually unaware that this is a possibility.

Trust in a company can play a key role in consenting to data collection. Out of the 109 participants, a mere 3 (2.8%) claimed they are fully confident in Google to handle their data responsibly. On the opposite end of the spectrum, 20 (18.3%) participants declared they are not confident at all when it comes to Google and their data. Most users mentioned that they have no other choice; among these 32 (29.4%) indicated that they trust Google in managing users personal data, while 44 (40.4%) mentioning they do not trust Google in managing users personal data. 10 participants reported that they simply had no opinion in regards to this question. Furthermore, 70 participants (65.2%) have not considered using an alternative to an app they were using due to privacy concerns. Forty-five (41.3%) out of 109 see no reason to consider an alternative app, while 25 (22.9%) are aware of alternatives, but have not considered switching because of privacy issues. 24 (22%) did, however, indicated that they have considered the app change, but had no valid alternatives to use, and 15 (13.8%) took action by using an alternative.

4.3 How well do participants understand privacy policies?

One participant (0.9%) out of 109 found privacy policies clear and easy to understand. Most, i.e., 47 (43.1%), found privacy policies quite complicated and difficult to understand. A handful of 10 users (9.3%) find privacy policies extremely complicated and struggled to understand them. Twenty-five (22.9%) find policies a little difficult, but understandable, and nearly a quarter (23.9%) find them neither difficult nor easy to understand. This establishes that a little more than half 57 (52.3%) of participants have trouble with the understanding of privacy policies whether this is extreme or not, while the other half range from difficult, but understandable to clear.

Despite nearly half stating that privacy policies are understandable albeit somewhat difficult, nearly all participants 94 (86.2%) share that apps should be more transparent with data collection and 12 (11%) responders have no opinion. Three participants (2.8%) did declare that apps are being transparent enough. These results are closely reflected by 84.4% of participants agreeing that they would prefer if apps and companies show a simplified privacy policy that presents the most relevant information to them. Similarly, 81.7% concur that a simplified version of privacy policies will help understand their privacy and use of data better than current privacy policies. These results were unexpected due to the number of participants who stated that policies were understandable.

Few participants gave additional feedback/opinions on this topic. For example: “I must emphasize how little data privacy is on my radar as a tech user. Conceptually, I understand the importance of it, but the specifics of what companies collect for what reason is not clear to me at all.”

5 Facts from public daily news

Trusting companies like Google about data collection and management, comes with some degree of risk, whether this is from inside Google or from outside attacks. There is always the risk of misuse even with regulations in place. 62 (56.9%) out of 109 participants reported they were somewhat aware of breaches and the possibility of breaches happening, while 29 (26.6%) stated they are aware and inform themselves about this issue. However, 18 (16.5%) declared they were unaware of these breaches. Further in this section, we explore some instances of Google's deceptive practices and situations where user data was at risk through an outside influence.

5.1 Google's issues concerning user data

Prior to GDPR, Google faced fines in September 2014 for violating user privacy in six European countries by building user profiles based on various sources without consent (Timothy et al., 2015). Google was forced to comply with Germany's “Right to forget” law and many countries such as South Africa and Brazil adopted similar practices after the fact (Timothy et al., 2015). This suggests that Google might collect and use data in any way that is not explicitly prohibited. Another similar event from Google is their $391.5 million settlement in 2018 due to tracking user locations despite them having opted out of this tracking, meaning that they were being secretly tracked by Google (TheWashingtonPost, 2022). This affected two billion users not only in maps services, but also Google's Android operating system and search services. This was the largest U.S. settlement in history, spanning 40 states with the attorneys general stating that Google has continuously deceived the public regarding its location tracking with the earliest known controversy starting in 2014 (TheGuardian, 2023; ERP Today, 2023). Later, in 2019, Google received a $170 million fine for violating child privacy laws and collecting data from children under the age of 13 without the consent of their parents (Federal Trade Commission, 2019). Further, in April 2020, Google faced allegations in a legal case of gathering Internet browsing data from individuals utilizing “private” or “incognito” browsing modes for $5 billion in damages and reparations. This was brought up by Google employees joking that incognito mode does not actually provide privacy and that more can be done for users (Computer World, 2022). Within that same year in July, Google was forced to pay $60 million in fines after being called out by an Australian watchdog for deceiving numerous Australian users regarding the utilization and gathering of their personal data. This meant activity on sites unrelated to Google were merged with Google account data to display targeted advertisements without direct consent from the user (Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 2022). In some of these cases, despite having regulations or promises of proper use of data, Google has been shown to flaunt some regulations.

5.2 Google's data breaches

Now let us examine some instances where the security of user data was breached and led to negative consequences. Users place their trust in Google to keep their data safe, and Google should be held responsible for any security vulnerabilities. The earliest instance is the 2009 Chinese hacking of Google servers (The Washington Post, 2013). Chinese hackers procured a database with sensitive information that spans years. Google was the “first U.S. firm to voluntarily disclose an intrusion that originated in China,” with the chief legal officer for Google stating that the source code for Google's search engine was stolen and there was also a specific focus on the email accounts of Chinese human rights activists (The Washington Post, 2013). In this case, Google can be considered trustworthy because they officially announced the hacking to the public for full transparency. In September 2014, ~5 million Google passwords were allegedly leaked on a Russian Bitcoin security online forum with claims that 60% of them were still in use; Google denying this saying that there is “no evidence that our systems have been compromised” (Time, 2014).

The last significant vulnerability we mention here is the Google+ bug that compromised about 53 million users' data in total (The Wall Street Journal, 2018). In March 2018, a bug in Google+ exposed private data such as name, email address, occupation, gender, and age of up to 500,000 users (CNBC, 2018). It is reported that Google decided not to inform the public, possibly in an attempt to not be exposed to “regulatory scrutiny and cause reputational damage” (The Wall Street Journal, 2018). The presence of bugs in platforms like Google+ is an unfortunate consequence that can potentially compromise users' account information. While it is easy to hold Google accountable for any service shortcomings, it is important to recognize that these situations can occur and companies cannot always be perfect; however, the deceptive actions of Google to not lose public reputation can justify a negative image of Google. Due to this bug, Google decided to shut down the Google+ service over a duration of 10 months (CNBC, 2018). The termination of the Google+service was accelerated to April 2019 instead of August 2019 due to the bug exposing a further 52.5 million users' information after the November 2018 vulnerability (NPR, 2018).

The aforementioned public news articles highlight Google's issues and security flaws resulted in the improper handling of user data. It is difficult for companies to be flawless when it comes to the collection, use, and retention of user data. It is important for the general public to be aware of this potentially improper user data management and be ready for the possibility of more in the future.

6 Discussion

The results of this survey (summarized in Section 4) helped us to provide an understanding of where user perspectives lay for RQ1:

How informed are users of their privacy rights and the use of their data through privacy policies?

Based on the findings, users are not very well informed on data collection an privacy rights, but most do have at least some basic understanding of them. In this section, we address some implications emerging from the results of our survey concerning the users.

6.1 Lack of user reading

The results of our survey indicate that the vast majority of participants rarely or never read privacy policies; this implies most users do not completely understand how their information is collected and used. With 58.7% always using and 37.6% sometimes using Google Maps as their smart mobility app, the percentage of participants who never read Google's privacy policy at 88.1% is extremely high and, more importantly, not a single person is familiar with it. This is further reinforced by the hidden experiment embedded in our survey (see Figure 4), which revealed that only 7.4% of users (eight out of 109) read or skimmed the provided privacy policy. Interestingly, the proportion of computer science participants who read the policy was around double than of the non-computer science participants. This could be the result of having a technology-based background; however, this is speculation as other backgrounds such as law may also have an impact on whether users read or do not read privacy policies. These numbers show similarities with results from Steinfield (2016)'s research where users mostly agreed without reading the policy.

Moreover, similar results are shown when asked if users ever re-read privacy polices after changes. This suggests that even if companies changed their policy for any reason whether it is beneficial or detrimental, users will likely not read even if it may be important. Most participants in this survey who do not read Google's privacy policy may be explained by a few reasons. The first reason is mentioned in prior research: privacy policies are just far too long. This is supported by the 84.4% of users preferring a simple privacy policy that explains relevant data practices to them, suggesting that the time cost of reading outweighs the benefits. Naturally, shorter privacy policies are not so simple as seen in Ravichander et al. (2021) due to relevance of different parts of privacy policies vary between user to user and can actually lead to negative consequences for understanding. This propagates the idea that time is important to users. As mentioned in McDonald and Cranor (2008), reading privacy policies can be extremely time consuming and through the survey, it appears that users want the companies to put in the effort for privacy policies, rather than vice versa. This is significant when taking into consideration how much Google Maps is used among participants. It may be understandable to not read privacy policies for every site and app one can use, but the large majority of participants still do not read the privacy policy of one app that they use daily. This is significant because it can hold a strong theoretical implication. Perhaps the fault cannot lie entirely on companies despite their overly complex and ambiguous privacy policies, but users share a responsibility in the lack of awareness due to not putting in any effort. It is impossible and inaccurate to predict whether the ideal privacy policy that everyone can understand will have an impact on how many users read the policy; however, the results of the survey do suggest the possibility that users will still skip the policy, regardless of its complexity. This is purely theoretical based on the evidence presented in the survey but does create room for further research.

6.2 Lack of user understanding

From our survey it results that a minimal number of participants are able to fully understand privacy policies and most are somewhat aware of their data use, suggesting at least a basic level of understanding. The additional feedback left by one participant helps demonstrate this point: “I must emphasize how little data privacy is on my radar as a tech user. Conceptually, I understand the importance of it, but the specifics of what companies collect for what reason is not clear to me at all.” This implies that some users know of data collection, but are left in the dark when it comes to why. There are a few possible reasons for this. Results from the survey indicate only few users with strong feelings about privacy. This implies that users are generally not overly concerned about privacy. This is supported by the majority of participants not considering alternative apps due to privacy concerns. Our second hidden experiment (i.e., regarding how many people clicked the link and read the policy—see Figure 4) showed that the number of users opening the privacy policy is already low, and it is even lower when testing if they skimmed the document. However, this can be contradicted as most participants would like companies to make more efforts to notify users of privacy and data collection. This unexpected pattern in the results indicates that even though users may find privacy somewhat important, they still want transparency regarding their data. Perhaps this exists due to the basic understanding that users have of how companies use their data. It is possible that if they read the policy and understood it as a whole, their concern over data collection may increase. Unfortunately, this is only a hypothesis since the survey did not test further.

6.3 Trust in the company

The other reason that could explain the discrepancy of basic level of understanding despite not reading policies is trust in the company. Harvard Business Review conducted a poll in 2015 and discovered that 68% of users trust Internet giants with their data and 66% trust governments with data (see Figure 5) (Timothy et al., 2015). This demonstrates trust potentially playing a role in lack of privacy and data collection awareness. Timothy et al. (2015) stated that these highly trusted companies “may be able to collect [your data] simply by asking.” If users trust Google, users might be less likely to read privacy policies because there is less reason to. Despite this, we can question the trust in Google. Only a little more than a quarter of participants stated that they were aware of data breaches and potential threats to their data. Most users declare they are aware of the possibility and know of some instances. From this, it is clear that many users do not know about Google's issues in the past (some of them mentioned in Section 5). If this is the case, then we can assume that, perhaps if users were aware of these instances, trust in Google as an Internet giant may be impacted.

Figure 5. Percentage of people that trust organizations (Reproduced with permission from Timothy et al., 2015).

Connecting to the trust in Google as an Internet giant, Google Maps has a large following due to there being no alternative that offers the features and trusted functionality. The next largest alternative would be Apple Maps, but as stated before, the satisfaction and number of users are in a different league when it comes to these two Maps apps. This can be seen with the 69.8% of survey participants having no other choice, regardless of whether they trust Google or not to be responsible with data. This prevents users from making alternate choices based on privacy due to the fact that there is no alternative that offers the same trust and functionality and implies that Google holds a large influence on many people. Theoretically, Google can stretch data practices that are detrimental to users (as evidenced by the September 2014 case mentioned in Section 5). Thankfully, regulations such as GDPR have taken steps to reduce this possibility; however, there still is the risk that regulations do not cover everything for user privacy.

6.4 Google's privacy policy

After addressing previous research and described our survey, we analyze here Google's privacy policy and how it is structured. The current privacy policy contains around 5,300 words.4 The structure of the policy is similar to a layered notice, where the top layer provides users with important headings with a larger notice below containing all the detailed information. Layered notices are effective when handling larger notices so Google has taken significant steps toward more user friendly privacy policies. These layers contain videos that provide a visual perspective of that part in the policy. Furthermore, Google has a privacy checkup tool that helps users choose their privacy settings in a user friendly environment. This can help the 23.9% of survey participants that do not know how to adjust their privacy settings. Google has taken steps to assist users in understanding their privacy and data use due to regulations and issues that have called Google out. Fortunately, it appears that being an Internet giant comes with more scrutiny and stricter vigilance from countries and people, helping ensure Google's compliance with privacy laws.

As results from this section, many aspects of various types should be considered in privacy awareness and data collection. Both companies and users should invest effort in this direction. In Section 8, we introduce some promising approaches in improving privacy awareness. We consider that this is an open topic, which is intrinsically dynamic and evolves together with the advances of technology and its impact in everyday life.

7 Limitations

Our study on data collection and privacy has some limitations. We discuss a couple of them in this section.

7.1 Sampling and bias

The existence of bias is one of the limitation of our survey.

As mentioned in the results, the participants are mainly between the ages of 18 and 24. This demographic is appropriate for exploring the perspective of the young generation; however, there may be age bias and these findings may not be generalized to a larger population or other age ranges. Furthermore, the survey was voluntary and posted within group chats or sent via emails. The participants to the survey may not be representative for the people who choose to not provide their feedback. Our survey does not account for such biases like self-selection and social desirability bias or cultural differences. To overcome these limitations, an appropriate sampling method should be considered, e.g., cluster or purposive sampling to have a sample that is much more representative of the younger generation rather than use convenience one.

7.2 Limited number of questions and responses

The number of survey responses is another limitation. This creates limited representation which can lead to less reliable results when considering the vast population of users. There was no incentive to fill out the survey and maybe this demotivated the users to volunteer. An incentive should be provided for participants that outweighs the time cost of taking the survey.

The questions can also be a limitation since they do not encompass everything about the user perspective. The questions needed to be broad enough so that an accurate user perspective is derivable from the survey, but also need to be somewhat simple for participants' understanding. Furthermore, participants may choose answers that do not represent the objective truth (in the multiple choice answers) meaning participants may have selected an option, but there is no way to verify their statements. This can lead to skewed data, i.e., not representative for the participants.

The survey had to be relatively short with easy answers and not too many questions or answers. People are less likely to answer surveys if there are too many questions (Gray and raenn, 2016). A consequence of this is the lack of detailed answers.

7.3 Link tracker

The link tracker for the privacy policy also has some limitations. It cannot track the participants who only opened the link and did not complete the survey. Furthermore, robots and other sources can provide extra clicks that are not made by humans that can skew the results of the link tracking. Moreover, the test to see if participants read the policy was placed at the bottom and, therefore, does not provide an accurate representation of who reads or skims the policy, if they simply scrolled to the bottom without reading the policy.

8 Solutions to enable privacy awareness and understanding

There are some emerging technologies offering pro-mising solutions to raise the privacy awareness. For example, Natural Language Processing (NLP) is a field where a potential solution to informing users in an appropriate way about their privacy is found. Kumar et al. (2020) created an extension for browsers called Opt-Out Easy that helps users with choice presentation. Mysore Sathyendra et al. (2017) developed a method to automatically identify instances where users are given choices in a privacy policy. These tools help increase user awareness when it comes to having choices and help users decrease the amount of time figuring out their possible options. There are, however, some challenges for NLP when it comes to privacy and its related policies. One of these is the fact that what is not presented in the policy is just as important as what is presented; and processing privacy policies requires the ability to handle ambiguity and items such as lists in policies (Ravichander et al., 2021).

NLP has also been tested to automate data practice detection for effective user navigation and to help policy regulators evaluate many policies through automation (Ravichander et al., 2021). Unfortunately, privacy policy summarizing drawbacks make it difficult to find a solution that works for all policies. As mentioned in Ravichander et al. (2021), deciding which parts of the policy should be shown to the user is challenging. More importantly, Gluck et al. (2016) outlines that summarizing policies requires leaving out some of its parts; this leads to poorer understanding, meaning that it is crucial not to make errors when choosing what to exclude.

Furthermore, Reidenberg et al. (2015) states that it is difficult to automate tools for privacy policies due to disagreements between privacy and law experts. Overall, NLP is a possible solution to the difficult nature of privacy policies and may help users better understand these policies. We cited only few examples of NLP here in order to present the idea of NLP being a solution. Despite its progress, there remain challenges that require further research and development of tools for NLP to assist users in grasping a firm understanding of their privacy.

One problem mentioned in prior research is the inconsistency between how data is actually used and the privacy policy of applications, leading to inaccurate privacy labels (Gardner et al., 2022). Among the main reasons generating such inconsistency, Gardner et al. (2022) mention the software developers' limited expertise in privacy, re-use of code, and use of third-party libraries. For example, consciously or unconsciously, developers may adopt solutions that compromise the privacy as well as the accuracy of privacy notices. Or, they may sacrifice users' privacy to develop features that generate profits, e.g., using an advertising network without evaluating the data collection practices of that network. While not directly being a solution to the problem of comprehension of privacy policies, the first step would be to ensure that the policies are accurate. Gardner et al. (2022) developed the Privacy Label Wiz (PLW) tool that helps by analyzing code in order to support developers fill out the privacy labels more accurately. This tool has screens that ask developers the reason why they use specific data and helps them actually identify the specific permissions set by iOS that their particular app is using (Gardner et al., 2022). This can also help the problem described in Schaub et al. (2017) where the lack of synergy between the legal team and developers creates complicated privacy policies. If permissions are clearer by using a tool, the legal team can have an easier time creating more user-friendly privacy policies.

Recent research is focused on how AI can support awareness and understanding of privacy policies, as well as how AI-based systems impact the complexity of privacy policies. For example, Aydin et al. (2024) studies how Large Language Models (LLMs) can be used to assess privacy policies automatically for users. The paper explores the challenges from three interdisciplinary points of view: technical feasibility, ethical implications, and legal compatibility. On the other hand, the white paper (Stanford University - Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence, 2024) examines how current and emerging privacy and data protection laws affect AI development, and offers strategies to reduce privacy risks in the age of AI.

9 Conclusions and further work

As we rely more on companies and context aware (e.g., location-based) services like Google Maps, privacy protection becomes more crucial. Through our research, we aim to raise awareness about the data collection from the companies developing such services. We encourage readers to critically evaluate privacy and data collection whenever they use such services. We also highlight the need for further research and development of guidelines, resources, and tools that increase users understanding and help users make informed decisions when it comes to their privacy.

Our research highlights significant issues of current privacy policies. Through combining this study and prior research, we emphasize the need for user-friendly privacy policies that help individuals gain a comprehensive understanding of data collection and privacy rights.

This paper explored the two research questions:

RQ1: How informed are users of their privacy rights and the use of their data through privacy policies?

Users generally have a basic understanding of their data collection and privacy rights, but lack a deeper understanding of what data is collected.

This not only applies to Google Maps, but seemingly to most apps users typically use. This was shown to be caused by the ineffectiveness of privacy policies to convey the proper information to users among other factors such as trust and lack of time.

RQ2: How do we raise awareness about privacy and personal information shared with smart mobility apps like Google Maps?

Emerging technologies and tools that assist users' understanding should help raise awareness of data collection practices; however, these require more research to be effective, but are shown to be promising solutions.

The first step to be taken should be increasing user and company awareness of the issue itself, then furthered by tools to assist understanding. By informing people through this paper, we hope to enable users to make appropriate decisions and be aware of just how much of their data is collected.

We explored main aspects of data and Google, including data breaches, public facts, and open issues. This paper should serve as a catalyst to increase research and development that aims to protect users and regulate companies in this ever-growing data-driven age.

Privacy and data collection remain open research topics. The Google Map case study outlines their complexity. The efforts made by Google for privacy policies are huge and ongoing. However, there is still no perfect solution in this direction. There are several potential directions toward such a solution. For example, a promising approach to inform users about their privacy issues is represented by NPL. However, our world is intrinsically dynamic and more and more digitalized; hence, privacy and data collection need to evolve continuously, too.

A next research step to understand even deeper the privacy and data collection awareness, may investigate users' knowledge about the implications of the combination of their collected personal data (e.g., location) with other data to profile them or to perform more complex analysis.

Further research directions may also concern the link between the data collection methods (adopted by Google or other companies) and the local government policies, which may differ from country to country. This may have a significant impact on the user perception of privacy policies.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

CR: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KW: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^GDPR—https://gdpr-info.eu/.

2. ^Link to Google Privacy Policy.

References

Apple (2025). Privacy. Available online at: https://www.apple.com/privacy/labels/ (Accessed July 15, 2025).

AppStore (2025a). Apple Maps. Available online at: https://apps.apple.com/us/app/apple-maps/id915056765 (Accessed July 15, 2025).

AppStore (2025b). Google Maps. Available online at: https://apps.apple.com/us/app/apple-maps/id915056765 (Accessed July 15, 2025).

Australian Broadcasting Corporation (2022). Google fined $60 Million for Misleading Some Australian Mobile Users about Collection of Location Data. Available online at: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-08-12/google-fined-60m-misleading-mobile-users-location-data/101329790 (Accessed July 15, 2025).

Aydin, I., Hermann, D.-F., Vincent, F., Julia, M.-K., Erik, B., Michael, F., et al. (2024). “Assessing privacy policies with AI: ethical, legal, and technical challenges,” in Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on AI-based Systems and Services (Venice: IARIA Press).

CNBC (2018). A Google Bug Exposed the Information of up to 500,000 Users. Available online at: https://www.cnbc.com/2018/10/08/googlebug-exposed-the-information-of-up-to-500000-users.html (Accessed July 15, 2025).

Computer World (2022). Google Execs Knew ‘Incognito mode' Failed to Protect Privacy, Suit Claims. Available online at: https://www.computerworld.com/article/3678190/googleexecs-knew-incognito-mode-failed-to-protect-privacysuit-claims.html (Accessed July 15, 2025).

Costante, E., Sun, Y., Petkovic, M., and den Hartog, J. (2012). “A machine learning solution to assess privacy policy completeness: (short paper),” in WPES '12: Proceedings of the 2012 ACM Workshop on Privacy in the Electronic Society (New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery), 91–96. doi: 10.1145/2381966.2381979

Earp, J., Anton, A., Aiman-Smith, L., and Stufflebeam, W. (2005). Examining internet privacy policies within the context of user privacy values. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 52, 227–237. doi: 10.1109/TEM.2005.844927

EnterpriseAppsToday (2025). 20+ Mind-Blowing Google Maps Statistics for 2022: Usage, Accuracy, Updates, and More. Available online at: https://www.enterpriseappstoday.com/stats/google-maps-statistics.html (Accessed July 15, 2025).

ERP Today (2023). Meta and Google Fined. Who's Next in the Data Scandal Saga? Available online at: https://erp.today/meta-andgoogle-fined-whos-next-in-the-data-scandal-saga/ (Accessed July 15, 2025).

Federal Trade Commission (2019). Google and Youtube Will Pay Record $170 Million for Alleged Violations of Children's Privacy Law. Available online at: https://www.ftc.gov/newsevents/news/press-releases/2019/09/google-youtubewill-pay-record-170-million-alleged-violationschildrens-privacy-law (Accessed July 15, 2025).

Flesch, R. (1981). How to Write Plain English: A Book for Lawyers and Consumers. Ashburn, VA: Barnes and Noble.

Gardner, J., Feng, Y., Reiman, K., Lin, Z., Jain, A., Sadeh, N., et al. (2022). “Helping mobile application developers create accurate privacy labels,” in 2022 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy Workshops (EuroS&PW) (Genoa: IEEE Computer Society), 212–230. doi: 10.1109/EuroSPW55150.2022.00028

Gluck, J., Schaub, F., Friedman, A., Habib, H., Sadeh, N., Cranor, L. F., et al. (2016). “How short is too short? Implications of length and framing on the effectiveness of privacy notices,” in SOUPS '16: Proceedings of the Twelfth USENIX Conference on Usable Privacy and Security (Denver, CO: USENIX Association).

Google (2025a). Google Play. Available online at: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.google.android.apps.maps (Accessed July 15, 2025).

Google (2025b). Privacy policy. Available online at: https://policies.google.com/privacy?hl=en-us (Accessed July 15, 2025).

Huan Li, J. H., and Kwan, M.-P. (2025). Challenges in geoprivacy protection: methodological issues, cultural and regulatory contexts, and public attitudes. Trans. GIS 29:e70075. doi: 10.1111/tgis.70075

Keßler, C., and McKenzie, G. (2018). A geoprivacy manifesto. Trans. GIS 22, 3–19. doi: 10.1111/tgis.12305

Korunovska, J., Kamleitner, B., and Spiekermann, S. (2020). “The challenges and impact of privacy policy comprehension,” in Twenty-Eigth European Conference on Information Systems (ECIS2020) (Marrakesh: AIS).

Kumar, V. B., Iyengar, R., Nisal, N., Feng, Y., Habib, H., Story, P., et al. (2020). “Finding a choice in a haystack: automatic extraction of opt-out statements from privacy policy text,” in WWW '20: Proceedings of The Web Conference 2020 (Taipei: Association for Computing Machinery), 1943–1954. doi: 10.1145/3366423.3380262

Kununka, S., Mehandjiev, N., Sampaio, P., and Vassilopoulou, K. (2017). “End user comprehension of privacy policy representations,” in End-User Development (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 135–149. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-58735-6_10

Li, H., Yu, L., and He, W. (2019). The impact of GDPR on global technology development. J. Glob. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2, 1–6. doi: 10.1080/1097198X.2019.1569186

Libert, T. (2016). “An automated approach to auditing disclosure of third-party,” in WWW '18: Proceedings of the 2018 World Wide Web Conference (Lyon: International World Wide Web Conferences Steering Committee). doi: 10.1145/3178876.3186087

Linkly (2023). Tracking Links Solved. Available online at: https://linklyhq.com/#linkly-features (Accessed July 15, 2025).

McDonald, A., Weeder, R., Kelley, P., and Cranor, L. (2009). “A comparative study of online privacy policies and formats,” in PETS 2009: Privacy Enhancing Technologies (Seattle, WA: Springer), 37–55. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-03168-7_3

McDonald, A. M., and Cranor, L. F. (2008). The cost of reading privacy policies. I/S J. Law Policy Inf. Soc. 4, 544–568.

Mysore Sathyendra, K., Wilson, S., Schaub, F., Zimmeck, S., and Sadeh, N. (2017). “Identifying the provision of choices in privacy policy text,” in Proceedings of the 2017 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (Copenhagen: Association for Computational Linguistics), 2774–2779. doi: 10.18653/v1/D17-1294

NPR (2018). Google Accelerates Google+ Shutdown After 52.5 Million Users' Data Exposed. Available online at: https://www.npr.org/2018/12/11/675529798/with-52-5-million-users-data-exposed-on-google-googlequickens-shutdown (Accessed July 15, 2025).

Ravichander, A., Black, A., Norton, T., Wilson, S., and Sadeh, N. (2021). “Breaking down walls of text: How can nlp benefit consumer privacy?” in Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers) (Bangkok: Association for Computational Linguistics), 4125–4140. doi: 10.18653/v1/2021.acl-long.319

Reidenberg, J. R., Breaux, T., Cranor, L. F., French, B., Grannis, A., Graves, J. T., et al. (2015). Disagreeable privacy policies: mismatches between meaning and users' understanding. Berkeley Technol. Law J. 30, 39–88. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2418297

Schaub, F., Balebako, R., and Cranor, L. F. (2017). Designing effective privacy notices and controls. IEEE Internet Comput. 21, 70–77. doi: 10.1109/MIC.2017.75

Sheng, X., and Simpson, P. M. (2014). Effects of perceived privacy protection: does reading privacy notices matter? Int. J. Serv. Stand. 9, 19–36. doi: 10.1504/IJSS.2014.061059

Smyrnaios, N. (2019). Google as an information monopoly. Contemp. Fr. Francoph. Stud. 23, 442–446. doi: 10.1080/17409292.2019.1718980

Stanford University - Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence (2024). Stanford University - Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence: Rethinking Privacy in the AI Era: Policy Provocations for a Data-Centric World. Available online at: https://hai.stanford.edu/policy/white-paper-rethinking-privacy-ai-era-policy-provocations-data-centric-world (Accessed July 15, 2025).

Steinfield, N. (2016). “I agree to the terms and conditions”: (how) do users read privacy policies online? An eye-tracking experiment. Comput. Hum. Behav. 55, 992–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2015.09.038

The Guardian (2023). Google Will Pay $392m to 40 States in Largest Ever Us Privacy Settlement. Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2022/nov/14/googlesettlement-40-states-user-location-tracking (Accessed July 15, 2025).

The Wall Street Journal (2018). Google exposed user data, feared repercussions of disclosing to public. Available online at: https://www.wsj.com/articles/google-exposed-userdata-feared-repercussions-of-disclosing-to-public-1539017194 (Accessed July 15, 2025).

The Washington Post (2013). Chinese Hackers Who Breached Google Gained Access to Sensitive Data, U.S. Officials Say Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/11/14/technology/googleprivacy-settlement.html (Accessed July 15, 2025).

The Washington Post (2022). Google Reaches Record $392m Privacy Settlement over Location Data. Available online at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/nationalsecurity/chinese-hackers-who-breached-googlegained-access-to-sensitive-data-us-officialssay/2013/05/20/51330428-be34-11e2-89c9-3be8095fe767 story.html (Accessed July 15, 2025).