- 1Media and Communication, Symbiosis International University, Dubai, United Arab Emirates

- 2Symbiosis International (Deemed University), Pune, India

- 3The Emirates Academy of Hospitality Management, Dubai, United Arab Emirates

- 4Fatima College of Health Sciences, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

Introduction: The growing popularity of media-inspired home décor, where consumers draw aesthetic influence from movies and television shows, reflects a broader cultural shift in how individuals personalize their living spaces. While this trend has gained traction globally, limited research has explored the motivations and experiences of consumers, particularly among expatriates living in multicultural contexts such as the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

Methods: This study adopts a qualitative research design, utilizing semi-structured interviews with 15 expatriates from diverse professional and cultural backgrounds residing in the UAE. The collected data were analyzed using thematic analysis to uncover underlying motivations, perceptions, and challenges associated with media-inspired home décor.

Results: The analysis revealed six prominent themes: media-inspired self-expression, where participants used décor to communicate personal identity; aesthetic and emotional motivations that drive design choices; financial accessibility and creative adaptations that enable consumers to achieve desired looks within budget constraints; social validation and peer influence that shape décor decisions; risks of themed décor including potential drawbacks and limitations; and artistic engagement and cultural appreciation that demonstrates deeper connections with media content. Participants expressed strong connections between media-inspired décor and identity construction, emotional fulfillment, and cultural expression.

Discussion: The findings indicate that media-inspired home décor is a meaningful avenue for consumers to construct and communicate their identities while navigating practical limitations and evolving design trends. This study highlights the significance of symbolic and emotional drivers in consumer behavior and provides practical insights for interior designers, marketers, and home décor brands aiming to engage with culturally diverse and media-savvy audiences.

1 Introduction

In today’s streaming age, TV and film provide audiences immersive story worlds in which aesthetics are central to fueling audience experiences (Hareri, 2015; Hapsariniaty et al., 2019; Ryu and Cho, 2022). Audiences often form deep emotional bonds with fictional characters and their environments, which, in turn, drives a desire to recreate these on-screen spaces within their own homes (Ahn, 2013; Cioruța and Coman, 2020; Corkindale et al., 2021; Ertz et al., 2021). Media-inspired home decoration has been an on-trending phenomenon in recent years, wherein consumers proactively reproduce or re-imagine TV and film interior aesthetics. Beyond trend-driven adoption, it is a powerful vehicle in which individuals symbolically express aspects of identity, nostalgia, and aspirational ideologies. While researchers have explored the role of symbolic consumption and identity formation in various consumer settings, there remains a notable gap in examining how visual media, particularly narrative entertainment like films and series, influence domestic aesthetics and everyday material decisions (Ulver, 2019; Elliott, 2020; Nirupama et al., 2025). Even less is known about how consumers navigate these influences in multicultural contexts like the United Arab Emirates (UAE), where identity expression is deeply entangled with cultural hybridity and global media exposure.

Visual storytelling in contemporary media does more than entertain; it constructs immersive worlds that audiences emotionally invest in. This emotional resonance often leads to parasocial relationships, where viewers form one-sided attachments to fictional characters and their lifestyles (Sheldon et al., 2021). These relationships blur the boundary between media and real life, influencing consumers’ aesthetic decisions and inspiring them to recreate symbolic elements from on-screen spaces within their homes (Corkindale et al., 2021; Mehrabioun, 2024). In this way, screen-inspired décor becomes a site of symbolic consumption (Belk, 1988; Wang, 2023), where consumers use media-derived artifacts not merely for utility or beauty but as expressions of personal identity and cultural alignment. Such expressions are particularly meaningful in domestic spaces, which have increasingly come to function as sites of work, leisure, and self-presentation. The COVID-19 pandemic hastened this change by transforming homes into versatile spaces, leading individuals to rethink their interiors for enhanced productivity and comfort (Nagel, 2020; Zaman and Kusi-Sarpong, 2024). Even as remote work declines in some sectors, the desire for personalized and emotionally resonant interiors persists (Cachero-Martínez et al., 2024). Meanwhile, shifts in consumer values toward experiential and emotionally fulfilling consumption underscore why people invest in aesthetics that carry symbolic meaning, such as those evoked by their favorite media narratives (Weingarten and Goodman, 2021).

At the core of media-inspired home décor lies a desire to construct a projected self, where individuals blend personal narratives with mediated symbols to craft environments that feel intimate, aspirational, and culturally expressive (Ahuvia and Wong, 2002; Luna-Cortés, 2017). However, while theoretical frameworks like symbolic consumption, media influence, and parasocial interaction offer tools to understand this trend, few studies have synthesized these ideas to explore how they manifest within the material culture of the home. More critically, prior work often overlooks the lived experiences of consumers who draw from diverse cultural, generational, and financial contexts, factors that shape how they interpret and implement media aesthetics. This study addresses these gaps by examining how consumers, specifically expatriates in the UAE, engage with screen-inspired décor as a form of identity work and symbolic expression. It integrates perspectives from media psychology, consumer behavior, and cultural studies to explore why and how people selectively incorporate media-based aesthetics into their personal spaces. In doing so, the study not only builds on existing research in symbolic consumption and self-expression but also contributes to a richer understanding of how global media influences local practices of home-making. Through qualitative research, the study seeks to elucidate why consumers recreate these styled décors and their impact on their living experiences. The study aims to address the following research questions:

1. How do consumers use screen-inspired home décor as a form of symbolic consumption to express their identity?

2. What motivates consumers to replicate screen-inspired home décor in their homes?

2 Literature review

The media has long shaped consumer behavior, influencing societal values and lifestyle choices through visual storytelling. Traditional product placements in film and television subtly shaped consumer perceptions of idealized environments (Hackley and Amy Hackley née Tiwsakul, 2012; Mehta, 2020; Corkindale et al., 2021; Pavlović-Höck, 2022; Gamage et al., 2023). Nostalgia and admiration for specific media narratives, such as The Great Gatsby, Friends, and The Office, drive symbolic consumption in screen-inspired décor, allowing consumers to express identity and build cultural connections, thereby fostering a shared sense of belonging among fans (Reimer and Leslie, 2004; Cutting, 2021; Roy and Gretzel, 2022; Gierzynski et al., 2024). Moreover, with streaming and digital platforms showcasing diverse interior styles, media now serves as both entertainment and aesthetic inspiration. Consumers increasingly recreate iconic set designs, underscoring the media’s expanding influence on home décor as they adopt the aesthetics of beloved shows and films (Dubourg and Baumard, 2022).

2.1 Symbolic consumption and home décor choices

The idea of symbolic consumption serves as a fundamental perspective for comprehending how customers transform their belongings, including home decoration, into items that reflect more than their merely functional aspects. According to Belk (1988) extended self-concept theory, the use of material goods to symbolize one’s values, personality, and aspirations is the way that people materialize or physically reflect at least part of their identities. This concept is crucial to the area of home decoration, where customers design their houses to mirror their identity directly. The idea of designing a home to directly reflect one’s identity is central to the field of home decoration. Incorporating furniture, art, and design elements that resonate with personal narratives or cultural symbols in homes allows people to use their living spaces as a canvas of self-expression (Yan, 2018; Smitheram and Nakai Kidd, 2024). This approach to consumption brings out the need to see home décor as more than aesthetic; it becomes a tool for expressing one’s identity.

Media-driven symbolic consumption has become a multifaceted interplay between personal identity and cultural narratives. The screen-inspired decoration allows the customer to embed the distinct elements from their favorite shows or films to connect with aspirational or nostalgic symbols. For instance, Lee et al. (2020) and Nafees et al. (2021) emphasize that the hybrid identity of some consumers grants them the opportunity to mix their personal preferences and cultural elements, thus creating a multifaceted self-representation through home décor. The nostalgic and traditional feelings that period dramas evoke in certain viewers may touch on the values they attach to their heritage. On the contrary, a futuristic space’s hygiene and sleek design could be aligned with the outside desire for someone and the inclination toward an advanced way of living (Larsen et al., 2010; Dam et al., 2024). Through symbolic consumption, media-inspired décor facilitates identity projection, enabling consumers to communicate their personalities and cultural affiliations within their living spaces. These perspectives on symbolic consumption offer a foundational lens to understand how consumers selectively adopt screen-inspired décor to reflect their personal narratives, aesthetic sensibilities, and aspirational identities, making their homes not just functional spaces but symbolic expressions of who they are and what they value.

2.2 Psychology of media influence on domestic spaces

Recent studies in media psychology have shown how visual narratives play a key role in consumer behavior in the household (Seifert and Chattaraman, 2020; Kusá et al., 2023). Research by Dubourg and Baumard (2022) shows that the media’s ability to elicit positive or negative emotional feelings strongly predicts the adjustments viewers make to their décor choices, mainly when they form parasocial relationships with characters and settings. These one-sided psychological bonds allow the consumers to feel part of the lives of the characters they watch and, consequently, tend to add things related to some character’s surroundings in their own lives. The concept of “inspired-by-state” further illustrates how vivid media portrayals form a sense of inspiration that consumers observe to transfer into tangible décor choices (Sheng et al., 2020, p. 1043).

Modern media becomes more immersive as it emotionally engages the audience, who find themselves engaged in the character and story setting. Research on media richness and emotional attachment shows consumers usually recreate the on-screen atmospheres associated with loved characters or well-known locations (Ayhan Gökcek, 2023; Janicke-Bowles et al., 2024). For example, media depictions of close, welcoming spaces can make audiences replicate the same home environments to enhance personal wellbeing and social connection (Naukkarinen and Bragge, 2016; Izogo and Mpinganjira, 2020; Zahidi et al., 2024). People often change their home décor based on what they see in shows or films. They feel inspired to add elements that match the emotions or themes from these media, making those influences a real part of their daily lives. Understanding how people feel connected to fictional worlds can help explain their design choices in real life. These emotional ties show how consumers use on-screen environments as inspiration for expressing their identity at home.

2.3 Self-expression, identity formation, and home décor

This study focuses on how home décor helps people express themselves and form their identities, especially through media stories that resonate with them (Rogers and Hart, 2021; Kneese et al., 2022). Ahuvia and Wong (2002) explains that people make home furnishing purchases for practical reasons or to serve as keys to sharing their stories and connections. This process is key in screen-inspired décor because there is an intertwining of one’s identity with either an aspirational or a nostalgic media influence. Similarly, Whiteman and Kerrigan (2024) also believe that symbolic consumption allows consumers to test new dimensions of their self-identity through using possessions to communicate both who they are and what they are striving to become.

Screen-related interior design shows how consumers take design ideas from their favorite media to apply them to the setting of their homes. This trend also testifies that consumers want their décor to tell their own stories. This behavior is termed as “consuming for identity” (Zhang and Liu, 2022; Qu et al., 2023), where people select products either directly inspired by or from the media through which they express their identity. For instance, one could use a minimalist design displayed in their favorite TV show as a presentation of their love for simplicity. In contrast, another person might choose elaborate styles from historical dramas to demonstrate sophistication. In both cases, these decoration choices reflect their identities, turning their living spaces into personal statements.

2.4 Social media and home décor trends

Social media platforms have made it easier for home décor trends inspired by screens to spread. Social media platforms like Instagram, Pinterest, and TikTok allow people to see, share, and copy various design styles. This connection makes it simple to link online trends to physical living spaces (Izogo and Mpinganjira, 2020). The visuals on these platforms spark consumer interest in adopting styles seen in media, making it easier for them to bring those designs into their own homes. Research findings show that social media’s contribution to the spread of screen-inspired interior styles should not be downplayed because it increases the prevalence of these styles and generates a feeling of belonging among the followers (Zhang et al., 2022).

Through social media engagement, consumers find themselves in a trend-driven culture where media-induced aesthetics are bolstered into a contention of aspiration (Gao et al., 2024). It symbolizes the whole and communal spirit of decorating choices because one would look for interior design tips from any digital media like YouTube, check social networks for the external validation of their ideas, and then create a community around those decorating decisions (Cheung et al., 2020; Valle Corpas, 2021). As Jain (2024) points out that social media helps people show their unique interior design choices. This lets them express their identity through personal style, socializing, and media trends. As a result, individuals create a public identity where their décor reflects their tastes and builds a sense of community with others who share similar design preferences.

Research by Gamage et al. (2023) shows a clear connection between TV product placement and what consumers decide to buy. This research highlights how the media influences our preferences. Companies like IKEA have taken advantage of this by creating product collections inspired by popular TV shows. For example, the Stranger Things collection includes a replica of the Byers’ living room. The FRIENDS collection features famous items from Monica’s apartment and Central Perk, helping fans recreate these well-loved settings in their own homes (Creative Roots, 2023). This approach demonstrates how media-inspired home furnishings enable consumers to express their identities by integrating favorite on-screen aesthetics (Gain Pro, 2023). Such collaborations between entertainment studios and home furnishing companies create buzz, meeting consumer demand for customized products that closely mirror on-screen styles. Furniture makers and artisans increasingly produce niche, bespoke pieces, responding to consumers’ desires for authenticity and personalization in their spaces. In addition, more and more, interior designers are helping clients create the feel of their favorite films or TV shows (Singh and Singh, 2024). This has led to a new area of design that combines popular culture with personal home décor.

2.5 Reconciling theoretical tensions

Theories of symbolic consumption, media influence, and identity formation explain the trends in home décor inspired by screens. However, these theories also show some conflicts. Symbolic consumption focuses on how people express themselves through their belongings (Piacentini and Mailer, 2004; Sivanathan and Pettit, 2010). On the other hand, media influence theories suggest that outside aesthetic standards can limit what people choose to buy (Aljukhadar et al., 2020; Sun, 2023). This leads to questions about how much control individuals have versus how much they are shaped by culture in their home décor choices. This study looks at how home décor inspired by screens combines cultural trends and personal choices. It aims to show how people form their identities and respond to cultural influences in their décor decisions. By connecting these ideas, the research explores how screen-inspired décor reflects personal choices, media effects, and identity. This way, it helps understand how people see themselves based on the styles they use in their homes.

3 Methodology

This study used a qualitative research design, utilizing in-depth interviews to explore how consumers view interiors inspired by movies and shows. We used thematic analysis to examine the interview data. This method helps us find and understand patterns in the data (Clarke and Braun, 2013).

3.1 Sampling criteria

This study used purposive sampling to find participants who decorated their homes using ideas from movies or TV shows. We followed specific criteria to ensure that participants had relevant experience with this type of décor. We found potential participants through social media and conducted an initial screening to ensure they met the study’s criteria. A total of 23 interested individuals completed a short pre-interview questionnaire. This questionnaire assessed their motivations and gathered specific examples of screen-inspired décor in their homes. Only those who provided detailed examples were invited for in-depth interviews.

The final sample included 15 participants aged between 25 and 55, representing different generations. This allowed us to explore how various life stages can influence design choices inspired by media. We purposely included participants from diverse cultural backgrounds and professions to support the study’s goal of examining media-inspired home décor as a way to express identity. This diversity helped us capture a wider range of interpretations shaped by culture, occupation, and age (Channaoui et al., 2020; Bibbins-Domingo et al., 2022). It revealed nuanced differences, such as how nostalgia, aspiration, or cultural ties influenced décor choices, enriching the study’s findings. A more homogenous sample would have limited these insights, while the varied profiles enhanced our understanding of how people uniquely incorporate global media into their personal spaces.

The sample size was decided based on thematic saturation. This is a common standard in qualitative research that marks the point when collecting more data does not reveal new themes or insights (Hennink et al., 2017; Guest et al., 2020; Bazen et al., 2021). In this study, thematic saturation was observed after the 12th interview, with the remaining three interviews offering confirmatory rather than novel insights. The repetition of core themes, the consistency across participant narratives, and the analytical richness of the responses supported the decision to conclude data collection at 15 participants. Although literature acknowledges that the number required to achieve saturation may vary depending on the study design, participant diversity, and research objectives (Guest et al., 2020), the depth and coherence of data collected in this study affirm that the sample was sufficient to meet its analytic and interpretive aims (Bazen et al., 2021). The demographic profiles of the participants are as follows in Table 1.

The study acknowledges the predominantly female composition of the participant pool, which may reflect broader gendered dynamics in the engagement with domestic aesthetics. Prior research indicates that women often occupy primary roles in curating and maintaining household spaces, particularly in sociocultural contexts where the home is closely tied to feminine identity, emotional labor, and care work (Clarke, 2021). In this light, the female participants’ perspectives are not only relevant but also offer rich, situated insights into how screen-inspired décor choices are meaningfully integrated into the lived experience of home. While this gendered lens may foreground specific aesthetic values such as emotional resonance, nostalgia, or symbolic expression, it remains aligned with the study’s aim to examine how individuals embody and interpret media aesthetics within their personal environments. Nonetheless, the study notes that people’s aesthetic preferences can be influenced by their gender. It suggests that including a more diverse group of participants could lead to different interpretations and design choices. This focus on gender is seen as a limitation, and future research should aim to include a wider range of gender identities and expressions to better understand how aesthetic preferences may differ.

Additionally, the study focuses on expatriates living in the UAE. While this choice serves a purpose, it also limits how the findings can be applied to other cultures. Expatriates in the UAE constitute a distinct social group marked by cultural hybridity, transience, and evolving identity practices shaped by their immersion in a highly multicultural environment (Al Hameli and Arnuco, 2023). Their aesthetic choices and spatial practices often involve a dynamic negotiation between cultural traditions from their home countries and the socio-cultural influences of the host country. This positioning offers valuable insight into cross-cultural expressions of domestic aesthetics and the symbolic role of media in identity construction. However, this contextual specificity may constrain the transferability of findings to other cultural or national populations. Aesthetic sensibilities and spatial meanings are deeply embedded in cultural norms, historical traditions, and socio-political contexts (Redies, 2015). Therefore, the lived experiences and design preferences of expatriates in the UAE may differ markedly from those of local citizens or expatriates residing in less culturally diverse or differently regulated environments. While this study contributes to the growing discourse on transnational aesthetics and media-inspired domesticity, we acknowledge that the cultural lens applied here is context-bound. Future research would benefit from comparative studies across varied geopolitical and cultural contexts to explore how aesthetic engagement with media differs across transnational, national, and local settings.

The interviews followed a semi-structured format, which enabled open-ended questions and probing techniques to elicit comprehensive and detailed responses. Semi-structured interviews provide more flexibility as follow-up questions can be added to the process (Wu et al., 2021) and have only basic requirements for interviewees and questions (Kallio et al., 2016). The interview questions encompassed various topics, including participants’ motivations for employing movie/show-inspired interiors, the design elements and inspiration derived from fictional media, emotional connections and nostalgia, challenges and limitations encountered in recreating screen-inspired home décor, as well as social influences on their design choices. The interview questions focused on several important topics. These included why people choose to create interiors inspired by movies or shows, the specific design elements taken from these fictional works, and the strong emotional connections and nostalgia tied to these designs. The questions also addressed the challenges faced when recreating home décor based on screen inspirations and how social factors influence design choices.

All interviews for this study were conducted using Zoom. With the participants’ permission, each interview was recorded and then transcribed using Otter.ai, which automatically creates transcripts with timestamps. To make sure everything was accurate, two researchers carefully checked the transcripts against the original recordings to find and fix any mistakes. The final responses were then imported into NVivo (version 15) for analysis. The themes were developed through an inductive approach, allowing the researchers to identify patterns and trends from the data.

3.2 Thematic analysis

The analysis followed the steps outlined by Braun and Clarke (2006).

1. Familiarize yourself with the data: in this step, the interview data were transcribed verbatim and read repeatedly by the researchers. A systematic review was done, and initial readings were supported through creating memos documenting preliminary insights and patterns.

2. Generating the initial codes: in this phase, the initial codes are extracted from the data. The codes were generated with the transcripts’ help to find the answers to the objectives. The researchers worked through the data systematically, and segments were tagged corresponding to codes like “Advantages of Using Movie or Show-Inspired Décor,” “Motivation for Consumers to Replicate Screen-Inspired Home Décor,” and “Emotional and Inspirational Impact.” To ensure that different coders agree on the analysis, we used Cohen’s kappa coefficient to measure their agreement. This method is well-known for effectively checking consistency in analyzing qualitative data (McHugh, 2012). During the first coding phase, we received a Cohen’s Kappa score of 0.75, which shows substantial agreement among the coders. After this initial check, we identified some coding differences and worked together to discuss and resolve them. We adopted a process that allowed us to revisit the data, refine code definitions, and adjust how we applied the codes as we gained new insights. This approach helped maintain consistency in our coding process by systematically establishing agreement among coders and addressing discrepancies, which strengthened the reliability of our analysis (Campbell et al., 2013).

3. Searching for themes: in this step, we gather the codes and group them into possible themes using the relevant data. We sort all the codes into themes that show how they relate to each other, as well as how the different themes connect and fit together. This was done with the help of “query” and “modeling” features in NVivo 15, and the related nodes were developed into broader themes.

4. Reviewing themes: this step helps understand the different themes, how they fit together, and the overall story the data represents. The themes were reviewed for coherence and relevance to find the connection between themes. Similar nodes such as “Emotional and Inspirational Impact” and “Emotional and Mood Evocation” were merged to refine the theme of influence and impact, and complex nodes like “Inspirations through decorative touches” were subdivided to differentiate between various sources of inspiration like cinematic elements and cultural heritage and some codes like “Source of Inspiration” were reassigned to more specific nodes under the theme of aesthetic and personal expression to ensure clarity and distinctiveness of each theme.

5. Defining and naming themes: all the themes were defined in detail to provide a clear framework for thematic descriptions in the final report. It helps generate clarity and helps in realizing the overall story the data tells.

6. Producing the report: in this step, the final analysis of the extracted themes is done, relating them to the research questions and the literature.

As Clarke and Braun (2013) noted, a common pitfall in thematic analysis is the tendency to use interview questions as themes. In contrast, this study generated themes and nodes directly from the findings. Initially, 93 nodes were created from 15 interview transcripts, and data saturation was reached after analyzing 12 interviews. The use of “word queries” and “coding stripes” proved valuable, enabling the researchers to consolidate these nodes into several potentially engaging themes while preserving as much detail and context from the interviews as possible.

3.3 Conceptual framework

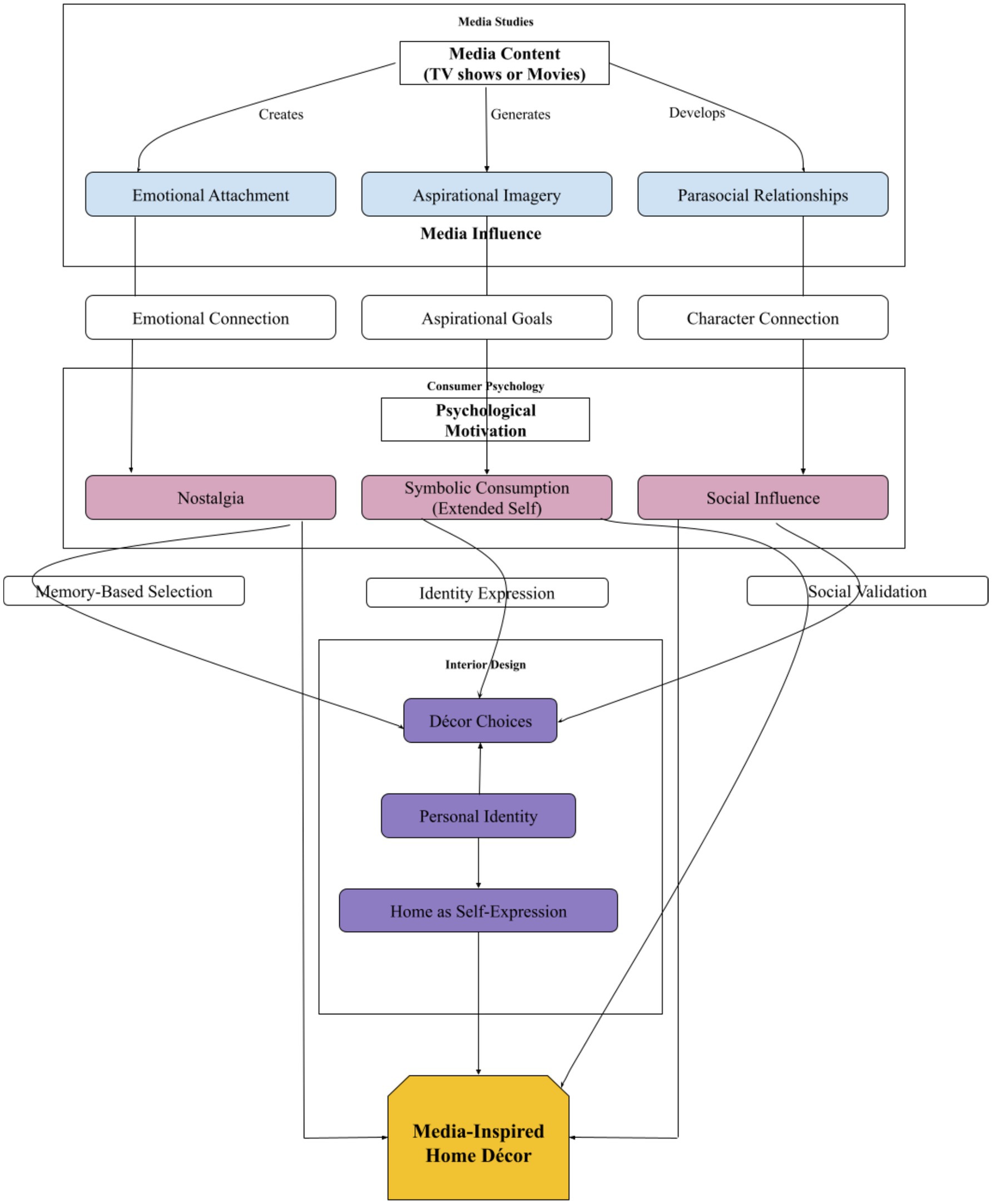

To provide a cohesive structure for examining screen-inspired home décor, this conceptual framework integrates key theories from media studies, consumer psychology, and interior design. Beginning with media studies, the framework shows how media content (such as movies and TV shows) exerts influence through aspirational imagery and emotional attachment, prompting viewers to connect with fictional settings and characters. This connection often leads to parasocial relationships, where viewers feel close to characters and their worlds. This creates a desire to bring those styles into their own homes. These themes come from an analysis based on symbolic consumption (Belk, 1988; Wang, 2023), parasocial interaction (Sheldon et al., 2021), and how we build our identities through media (Ahuvia and Wong, 2002; Whiteman and Kerrigan, 2024). When people review their interior design choices, they often find that emotionally engaging media content sparks these relationships. This, in turn, influences their choices about home aesthetics (Mehrabioun, 2024), which in turn affects symbolic aesthetic choices for their homes. These results support Belk (1988) theory that our possessions reflect our identities. However, people’s choices are also shaped by their budgets, creative solutions, and the need for approval from friends, often through social media (Zhang et al., 2022; Jain, 2024). This framework shows that identity is a process that evolves with time. Media images can evoke feelings, and these emotions lead to choices influenced by social and financial factors. This view enhances our understanding of the patterns we see and sets the stage for a deeper exploration of identity, emotions, and meaning in what we consume.

Consumer psychology and interior design are closely linked, with several factors influencing how people choose their home décor. People often select items that reflect their identities, which is known as symbolic consumption. They use their living spaces to express who they are through objects inspired by media. Nostalgia also plays a key role, as many seek to bring sentimental media connections into their homes. Additionally, social influence encourages shared design styles and trends among friends and communities. As shown in Figure 1, these factors come together in media studies, psychology, and design. They help shape screen-inspired home décor, where motivations from media and personal tastes blend into expressions of identity within our living spaces.

4 Results

The topics are structured methodically to demonstrate an analytical evolution from individual expressions of emotion and self to broader implications for society and practical considerations, and to highlight the range of motivations driving participants’ choices for screen-informed decoration.

4.1 Theme 1: media-inspired self-expression

Respondents often saw screen-inspired décor as a way of expressing unique aspects of their identity. Participant 4 stated, “When I decorate my home like a movie set, I’m not just following a style; I’m creating a space that feels like a different world. It’s an escape and a way to show who I am in a way that’s creative and personal.” This statement supports the idea that, for many, screen-inspired décor is both a means of expressing oneself and a personal sanctuary. In addition, their socioeconomic backgrounds shaped their design decisions. Participant 3 explained, “I cannot fully recreate scenes from my favorite movies, but I choose elements that resonate deeply with me and are within my budget. It allows me to express myself without going overboard financially.” The need to balance self-expression with budgetary constraints illustrates how participants balance their design preferences and personal life.

4.2 Theme 2: aesthetic and emotional motivations

The participants in the study underscored the importance of aesthetic and affective benefits that propel decoration based on screen media. Participant P9 explained, “I feel like having a beautifully themed home uplifts my mood every day. It’s not just about copying a scene; it’s about feeling connected to something I love and having it make my everyday life more inspiring.” This quote underscores the key role of décor in achieving an emotional goal, enabling participants to experience their desired media on a deeper and more enriched level. There was also the influence of cultural background, with P5 commenting, “In my culture, home is everything, so when I bring elements from shows or movies, it’s like inviting those stories into my family life. But I still keep it balanced. I do not want my home to feel too much like a set.” This reveals the complex motivations behind screen-inspired decoration, in which aesthetic appreciation, emotional connection, and cultural resonance come together.

4.3 Theme 3: financial accessibility and creative adaptations

The participants showed that financial constraints are an important consideration for their screen-inspiration décor, and many used cheaper alternatives. Participant 12 summed it up, saying, “I set aside a little each month to bring elements from my favorite shows into my home. It’s not just about having a piece of a movie; it’s a long-term vision that I plan carefully so I can afford it.” This shows how, to some, screen decoration is an investment over time rather than an on-whimsy acquisition. A group of people embraced an economical approach, best summarized by the comment of Participant 13: “If something from a movie is too expensive, I’ll find a way to recreate it on a budget. I do not need the exact item; I just want the feeling it brings.” Here, the participant’s creativity is supported by the flexible nature of media-influenced environments, allowing for the creation of an intended atmosphere even in the face of financial constraints.

4.4 Theme 4: social validation and peer influence

The role of peer influence and social media trends has indeed been noted to be a contributing factor towards the creation of media-themed décor among individuals. As Participant 10 described, “Seeing others integrate movie themes into their homes gave me the courage to try it. It’s like being part of a community, and it makes me feel like I’m sharing something meaningful with others who love the same things.” This quote conveys how peer acceptance can support such individuals’ self-confidence towards decorating their spaces with media-inspired themes. Other respondents, though, displayed a more discerning attitude towards adopting such décor. Participant 7 said, “I’m inspired by what I see online, but I only bring in elements that truly resonate with me. I do not follow every trend because I want my space to feel personal, not just popular.” This statement brings forth how, while media trends can influence design tastes, individual aesthetic taste actually prevails over the choice of elements to adopt.

4.5 Theme 5: risks of themed décor

The participants noted the limitations of heavily themed decoration, recognizing their tendency to date quickly or limit flexibility in household settings. Participant 11 said, “While I love movie-inspired décor, I try to keep it subtle. I do not want my home to feel like a theme park because styles change, and I want something timeless.” This illustrates that participants were expressing an intentionally moderated approach to decoration selection, seeking to create an aesthetic that will continue to be valid over time. Other participants, on the other hand, focused on the benefit of décor, which can easily be replaced, as explained by Participant 15, who said, “I’m fine with changing things up as trends shift. To me, the ability to refresh my décor keeps my space exciting and in line with what I’m passionate about.” What this shows is that for some participants, the ability to adjust screen-based decoration represents an inherent aspect of its attraction, promoting active engagement and investment towards the source of media.

4.6 Theme 6: artistic engagement and cultural appreciation

The media-influenced decorations are a means through which individuals are able to express their creativity, express appreciation for media culture, and exercise artistic engagement. Participant 14 expressed, “Decorating my home with elements from my favorite films feels like I’m curating an art gallery. Each piece has meaning, bringing a part of that world into my life.” This testimony captures the idea that media-inspired décor forms an art form that is beyond the aesthetic, combining cultural aspects with narrative meaning. At the same time, this activity also provides other participants with the opportunity to incorporate their own artistic expressions with their respective individuality. Participant 8 said, “I love the artistic side of adding movie-inspired elements, but I try to blend them in so they do not overwhelm the space. It’s about capturing the essence without losing my own style.” This view summarizes the way in which people use media-inspired décor to achieve harmony between personal aesthetic choices and shared cultural identity, thus creating environments filled with narrative meaning.

Despite their unique characteristics, participant accounts demonstrate a high level of interdependence and concomitant tensions that required careful negotiation between individuals. It is specifically clear that there was a tendency for social recognition and self-expression aspirations to align; most participants explained intentions to create spaces that mirror themselves while also seeking validation and approval from online publics. This finding suggests that identity formation processes do not solely stem from personal ambitions but are highly influenced by collective aesthetic practices. However, aspirations tied to beauty and aesthetics were often obstructed by economic constraints. Participants imagined methods of mediating the gap between aesthetic desires and economic realities, thus demonstrating their creative agency and personal identity. The findings emphasize the fact that media-focused interior design involves complex and multi-dimensional decision-making processes.

5 Discussion

The findings show that, under the influence of media sources, interior design is an important medium for symbolic consumption. Thus, decorative items that are derived from TV and film are used to symbolize aspects of individuality, desires, and ideals. As explained through discussion, participants consider their homes to be expressions of their unique tastes, often choosing design elements corresponding to much-loved narratives, characters, or distinctive environments depicted on-screen. The behavior fits theory for symbolic consumption, whereby objects are used to extend the self and work to convey one’s self-concept and identity to others (Belk, 1988; Francis and Adams, 2019; Arnould and Thompson, 2024; Gao et al., 2024). For example, under Theme Media-Inspired Self-Expression, all respondents discussed how décor inspired by screens helped them “escape routine” and convey aspects of self that would otherwise be unspoken. Participant P4 explained that media-themed décor creates “a space that feels different from the usual,” suggesting that such décor maintains its position between actual self and ideal self. Likewise, P3 included screen-themed elements while still observing financial resources, demonstrating how consumers attempt to maintain the authenticity of self-presentation while observing functional constraints. This behavior fits that of earlier work depicting symbolic consumption as dynamic and situational, open to responding to outside influences yet very much embedded in self-concept (Tangsupwattana and Liu, 2017; Sahin and Nasir, 2022). Theme for Artistic Engagement and Appreciation goes further towards illustrating this point, since many participants described living spaces as an “art gallery,” where artistic engagement can be included and represented through their individual narratives. For example, Participant 14 explained that each aspect of décor represents an individual component of a story or aesthetic that means much to them and therefore translates their surroundings into symbolic representations of their media-engrained life experiences. The theme shows how screen-inspired décor for such individuals plays an extra role beyond beautification for their homes; rather, it is an avenue through which they develop a narrative-based sense of self, which among other things aligns with the principles of symbolic interactionism that assume that products are used as tools for identity construction (Parutis, 2011). Moreover, study findings show a group of emotional, aesthetic, and social reasons why consumers choose to replicate screen-inspiration for home décor. The Aesthetic and Emotional Motivations theme shows how often participants choose media-inspiration for décor due to its capacity for producing nostalgia, comfort, and escapism. For instance, Participant 9 reported, “living in a beautifully themed home uplifts my mood every day,” and hence shows how much emotions screen-inspiration décor brings to daily life. This is typified by modern consumption theory on hedonic consumption, which argues that consumers seek pleasure and emotional congruence through material consumption (Campbell, 2018). These motives are largely influenced by cultural factors since people view decoration as an expression of familial or group identity. This observation actually boosts the sense of communal collectivism during decision-making (Zhong and Mitchell, 2010).

The theme, Financial Accessibility and Creative Adaptations, shows that for many of those who participated, financial considerations heavily impact their ability to reproduce décor from visual media. Even though money can be seen as an obstacle, most participants often overcome such an issue by coming up with creative ways of altering aesthetics from media based on their economic situations. For example, Participant 13 explained, “If something from a movie is too expensive, I’ll find a way to recreate it on a budget.” The idea embodies a new and dynamic type of motivation where financial limitations do not deter the desire to duplicate aesthetic details from screen media; instead, these restrictions provide impetus for innovative methods of accomplishing design goals. Secondly, the existence of Social Validation and Peer Influence is visible in how social relationships influence decision-making in obtaining décor from screens. Social media and the validation of peers have a major impact on the processes of selection for many, as represented by Participant 10’s comment, “Seeing others integrate movie themes into their homes gave me the courage to try it.” This motivation demonstrates a susceptibility to social conformity and the desire for belongingness, where the adoption of trending styles improves one’s standing within a larger community of similar others (Ali Taha et al., 2021). Nevertheless, the study also suggests that individual taste often moderates social motivations in that many participants selectively adopt only those items that are meaningful to them, implying a compromise between social validation and personal agency.

Although our observations align with the prevailing theories of symbolic consumption and parasocial interaction, they also add a novel level in demonstrating how consumers undertake what can be described as “negotiated identity performance.” This involves the accommodative tactics used by individuals in balancing aspirational media-generated aesthetics with utilitarian limitations like budget, culture, and functionality needs. For example, respondents discussed selectively recreating elements of the on-screen world- lighting, color palettes, or signature furniture pieces not in order to make exact copies, but to channel a desired emotional ambiance or symbolic meaning. These decisions were often moderated by budget and availability and led to creative conversions or substitutions. Social media and social acceptance further informed and recalibrated these aesthetic choices. In this manner, screen-inspired décor as an exhibition of identity is no simple act of mimicry but a performative process of managing personal taste, emotional connection, and social perception within an available budget. In this view, symbolic consumption theory is advanced by highlighting the socio-economic negotiations beneath apparently aesthetic decisions, and consumer behavior is redefined as a tactical, context-aware mode of self-presentation. Apart from individual-level implications, the research is also relevant to policymakers and public planners. With the growing cultural impact of global media and the rising aspiration for identity-based customization of living spaces, housing policy and urban planning can be aided with the facilitation of modular, adaptive, and effectively appealing design templates. Public housing or community development projects may incorporate culturally sensitive design features of residents’ mediated tastes to foster a sense of belonging and psychological wellbeing. Additionally, media authorities and cultural ministries may seek partnerships entrenching national media aesthetics through public design projects, demonstrating soft power while entrenching indigenous creative economies (Belk, 1988; Izogo and Mpinganjira, 2020; Weingarten and Goodman, 2021).

Building on our findings and the evolving trend of media-inspired customization, we propose a conceptual framework in the next section that showcases how symbolic consumption and identity expression theories can elucidate the motivations and practices behind consumers’ adoption of screen-inspired home décor. It provides a conceptual framework that explains the different individual, societal, and cultural forces shaping this unique design culture. Managerially, the findings provide actionable recommendations for lifestyle marketers, designers, and brands that want to target consumers who are media literate and motivated by emotional factors. By identifying the symbolic meanings linked to screen-mediated decoration, managers can adjust products and services to fit appealing design narratives that are essential for self-expression, evoking nostalgia, and projecting aspirational lifestyles. For instance, organizations can develop modular product lines or design kits for highly rated television programs and movies that enable consumers to customize products based on their budget, room space, and design taste. Designers can also think about incorporating hybrid styles that blend nostalgic media themes with culturally appropriate or locally inspired design elements, particularly in multicultural markets like the UAE. This would not just attract worldwide media-exposed expatriate consumers, but also promote consumer agency in the co-construction of spaces that both echo media effects and personal heritage. Social networking websites can also be utilized by marketers to upload consumer narratives and symbolic décor travel stories, facilitating community building and brand loyalty. In this manner, the research offers strategic direction on how to connect product development, narrative, and branding with changing consumer desire for homes that are emotionally authentic, aspirational, and culturally expressive.

The themes that we have identified from our data logically translate over to the two research driving questions of the study, providing a multi-faceted explanation of how and why consumers use screen-inspired home décor as a means of symbolic expression. In addressing RQ1—“How do consumers use screen-inspired home décor as a source of symbolic consumption to convey their identity?” Media-Inspired Self-Expression’s theme discovers that consumers actively use decorative items from beloved shows or films to convey personal values, aspirations, and affective allegiances. Participants described their dwellings as “mirrors of personality” or “safe spaces of imagination,” using décor not merely for style, but as mechanisms of identity formation founded on parasocial attachment and narrative symbolism.

Likewise, Aesthetic and Emotional Motivations strengthen media aesthetics’ role as affective anchors, providing a means of comfort, nostalgia, and mood management, extending their symbolic role to another level. In answering RQ2—“What are consumers” motivations for recreating screen-inspired home design in their own homes?’ Financial Accessibility, Creative Adaptations, Social Validation, and Peer Influence are themes that identify the various drivers of consumer behavior. Some of the participants discussed budget limitations and how they sought do-it-yourself alternatives, second-hand shopping, or incremental purchasing plans to attain their desired aesthetic. Some researchers have explored the invitation and validation provided on social media websites, where media-constructed environments are viewed as aspirational ideals and basic elements of cultural knowledge. The results show that the basic driving factors range across cultural aspiration, emotional association, pragmatic choice, and social interaction. Overall, such an overarching thematic framework illustrates that screen ornamentation goes beyond its superficial role of taste-making; more importantly, it represents an intricate blend of media-informed self-perception, personal values, and environmental components.

6 Conclusion

The current study provides an extensive analysis of consumer motivations, perceptions, and experiences relating to media-influenced interior decoration. In exploring the nuances of self-expression, personal meanings, and cultural fit that influence choices in media-influenced interior decoration, such findings indicate that consumer choices are a complex phenomenon where decorative items are more than functional and aesthetic properties but carry individual narratives and socio-cultural meanings. The findings align with symbolic and hedonic consumption constructs, where decorative items are chosen not only for their utilitarian functions but also for their ability to transfer individual narratives and engender self-expression, and for their fit for individual lifestyles (Wattanasuwan, 2005; Liu et al., 2017; Tangsupwattana and Liu, 2017; Francis and Adams, 2019; Izogo and Mpinganjira, 2020; Corkindale et al., 2021). The study also provides findings that align with proven theories of social confirmation through social media and peer networks (Izogo and Mpinganjira, 2020; Gierzynski et al., 2024); however, it contributes importantly to the current body of knowledge by explaining that, where there are societal influences, creative power and individuality among respondents are important drivers for such choices, empowering them to create environments that not only mirror collective cultural ideals but also unique individual expression.

Methodologically, qualitative, face-to-face, and semi-structured interviews allowed for an extensive analysis of emotional nuances and decision-making intricacies. This approach enabled us to capture not just what consumers chose to emulate from media, but why and how such choices were negotiated through personal, social, and fiscal contexts, information likely to be missed by quantitative survey research. This helps to highlight the strength of qualitative approaches to uncovering layered and symbolic dimensions of everyday consumption. Apart from accounting for individual consumer choice, the conclusions of this study have ramifications for urban design policy and public policy in general. With media-inspired aesthetics increasingly integrated into home settings, policymakers and urban planners can deliberate on the incorporation of culturally meaningful, emotionally engaging design features in public and low-income residential complexes. This might include facilitating adaptive, modular interior solutions expressive of residents’ mediated identities and cultural hybridity, especially apt for multicultural environments such as the UAE. Public cultural institutions and media regulators may also consider partnerships that foster a national narrative through interior design in support of soft power and local creative industries. By identifying homes as symbolic spaces that are created by media representations, public policy can play an important role in creating inclusive, identity-assertive spaces that lead to social cohesion and wellbeing. This study contributes to symbolic consumption knowledge by giving insight into how identity expression by media-influenced home décor is dynamic and not linear but negotiated among individual taste, social pressure, and expense. Aesthetics are selected by what a person wants to be, but these are shaped by expense, social acceptance, and cultural conventions. This nuance enriches existing symbolic consumption theories by positioning them within the mundane realities of economic praxis and mediated identity work.

Unlike some academic perspectives that define screen-influenced décor largely as an expression of trend-following behavior or escapism, this study demonstrates more substantial and lasting motivations. Specifically, participants describe wanting an artistic outlet and emotional enrichment via personalizing media-led spaces. The findings suggest the development of a consumer trend where home environments are places for self-expression and cultural articulation. Additionally, the recognition of economic and utilitarian reasons, such as participants’ attention to cost constraints, further enhances our understanding of consumer action concerning media-led décor. That consumer ambitions, together with economic constraints, are key driving promoters of the trend implies that individual desires, together with economic limitations, are significant determinants of consumer behavior towards screen-led décor. Follow-up studies would explore the implications of developing media technologies like virtual and augmented reality, which can lead to media-led environments. Investigating how such technologies influence home décor choices can provide more insight into media consumption behavior towards interior design choices. Future inquiry questions can also study screen-led décor across different cultural paradigms, considering how cultural expectations would influence consumer interaction and adoption of media aesthetics. Comparative analyses across socioeconomic divisions would also be likely to provide better insight into how economic resources shape media-led décor diversity and variety. Research on the influence of life stages on screen-inspired décor adoption would be insightful, as younger consumers and families may have differing motivations and practical considerations compared to older or single consumers. Another promising avenue for future research involves examining the impact of nostalgia on screen-inspired décor. Since many participants referenced beloved shows or movies from their pasts, understanding how nostalgia shapes décor preferences could shed light on the emotional factors underlying these choices. Longitudinal studies tracking how these preferences change over time would also contribute to understanding the permanence of screen-inspired trends and whether these choices are sustained or adapted to changing life circumstances. Practically, these findings offer actionable suggestions to interior designers, lifestyle companies, and entertainment companies. Understanding the symbolic and affective impulses toward media-influenced décor can be applied to develop more personalized, modular, and affectively rich product designs. Designers and marketers can tailor products that find a balance between aspirational design and price level, and also leverage popular media narratives to achieve brand connection and consumer engagement.

Despite its contributions, this study has limitations. While diverse in age, profession, and nationality, the sample size remains small and was recruited primarily through social media. As a result, the sample may skew toward individuals with a higher engagement in visually oriented social platforms, potentially limiting the generalizability of the findings. Similarly, the sample had a slightly higher proportion of female participants, which could influence the themes related to aesthetic preferences and identity expression, as prior research suggests gender-based differences in home décor motivations (Hoxha et al., 2022). These limitations suggest a potential bias in the representation of perspectives, although the range of ages, professions, and nationalities mitigates this to some extent. Future studies could benefit from recruiting through more varied channels to minimize potential biases further and enhance representativeness. Furthermore, the reliance on self-reported data through interviews introduces the possibility of response biases, as participants may present idealized versions of their décor motivations. Another limitation concerns the geographical and cultural scope. Although the study includes participants from various cultural backgrounds, it does not fully represent the global diversity of media consumption habits or cultural approaches to home décor. Moreover, this study’s qualitative nature does not allow for statistical generalization; quantitative research with a larger, more varied sample could complement these findings, providing broader insights into screen-inspired décor adoption. This study provides a rich, nuanced view of the motivations behind media-inspired home décor choices, bridging the fields of consumer behavior, symbolic consumption, and interior design. It underscores the role of personal identity, social validation, and financial considerations in shaping these decisions. Future research should expand on these findings by incorporating new technologies, diverse cultural contexts, and varied demographic groups, further unraveling the complex relationship between media and consumer behavior in home spaces.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of The Emirates Academy of Hospitality Management, Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their participation, both for involvement in the study and for the publication of findings. Given the low-risk, non-invasive nature of the research with no physical intervention or sensitive data, verbal consent was deemed ethically appropriate. The researchers followed all ethical standards, including ensuring confidentiality. Informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

TM: Visualization, Data curation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. BK: Software, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Methodology. FZ: Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis. SA: Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Writing – original draft. AT: Visualization, Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to all the participants who took part in the interviews. Their valuable contributions were essential to this research. Without their willingness and the time they dedicated, this study would not have been possible. Their thoughtful responses and insights provided crucial data for our analysis and findings.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Grammarly AI was used to paraphrase the text for clarity and to fix grammatical errors.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ahn, S. (2013). Cinematic innervation: the intuitive form of perception in the distracted perceptual field. J. Aesthet. Cult. 5:21681. doi: 10.3402/jac.v5i0.21681

Ahuvia, A. C., and Wong, N. Y. (2002). Personality and values based materialism: their relationship and origins. J. Consumer Psychol. Off. J. Soc. Consumer Psychol. 12, 389–402. doi: 10.1016/s1057-7408(16)30089-4

Al Hameli, A., and Arnuco, M. (2023). Exploring the nuances of Emirati identity: a study of dual identities and hybridity in the post-oil United Arab Emirates. Soc. Sci. 12:598. doi: 10.3390/socsci12110598

Ali Taha, V., Pencarelli, T., Škerháková, V., Fedorko, R., and Košíková, M. (2021). The use of social media and its impact on shopping behavior of Slovak and Italian consumers during COVID-19 pandemic. Sustain. For. 13:1710. doi: 10.3390/su13041710

Aljukhadar, M., Bériault Poirier, A., and Senecal, S. (2020). Imagery makes social media captivating! Aesthetic value in a consumer-as-value-maximizer framework. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 14, 285–303. doi: 10.1108/jrim-10-2018-0136

Arnould, E., and Thompson, C. J. (2024). “Consumer Culture” in Elgar encyclopedia of consumer behavior. eds. J. Gollnhofer, R. Hofstetter, and T. Tomczak (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing), 81–84.

Ayhan Gökcek, H. (2023). A meta-analysis in description and context dimensions including consumer behaviors intended for symbolic consumption. Soc. Sci. Dev. J. 8, 110–124. doi: 10.31567/ssd.821

Bazen, A., Barg, F. K., and Takeshita, J. (2021). Research techniques made simple: an introduction to qualitative research. J. Invest. Dermatol. 141, 241–247. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2020.11.029

Belk, R. W. (1988). Possessions and the extended self. J. Consum. Res. 15, 139–168. doi: 10.1086/209154

Bibbins-Domingo, K., Helman, A., and Dzau, V. J. (2022). The imperative for diversity and inclusion in clinical trials and health research participation. JAMA 327, 2283–2284. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.9083

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Cachero-Martínez, S., García-Rodríguez, N., and Salido-Andrés, N. (2024). Because I’m happy: exploring the happiness of shopping in social enterprises and its effect on customer satisfaction and loyalty. Manag. Decis. 62, 492–512. doi: 10.1108/md-11-2022-1536

Campbell, C. (2018). “Traditional and modern hedonism” in The romantic ethic and the Spirit of modern consumerism. ed. C. Campbell (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 107–130.

Campbell, J. L., Quincy, C., Osserman, J., and Pedersen, O. K. (2013). Coding in-depth semistructured interviews: problems of unitization and intercoder reliability and agreement. Sociol. Methods Res. 42, 294–320. doi: 10.1177/0049124113500475

Channaoui, N., Bui, K., and Mittman, I. (2020). Efforts of diversity and inclusion, cultural competency, and equity in the genetic counseling profession: a snapshot and reflection. J. Genet. Couns. 29, 166–181. doi: 10.1002/jgc4.1241

Cheung, M. L., Pires, G., and Rosenberger, P. J. (2020). The influence of perceived social media marketing elements on consumer–brand engagement and brand knowledge. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 32, 695–720. doi: 10.1108/apjml-04-2019-0262

Cioruța, B.-V., and Coman, M. (2020). Concerns and trends in the ecological house design and arrangement from film to reality. Asian Res. J. Arts Soc. Sci. 22, 16–27. doi: 10.9734/arjass/2020/v11i430176

Clarke, A. J. (2021). “The aesthetics of social aspiration” in Home Possessions. ed. D. Miller (London: Routledge), 23–45.

Clarke, V., and Braun, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. London: SAGE Publications.

Corkindale, D., Neale, M., and Bellman, S. (2021). Product placement and integrated marketing communications effects on an informational TV program. J. Advert. 52:1500. doi: 10.1080/00913367.2021.1981500

Creative Roots. (2023). Furniture as a cinematic storyteller: the impact of design on film and TV. Available online at: https://onlyrestored.com/blogs/news/furniture-as-a-cinematic-storyteller-the-impact-of-design-on-film-and-tv (accessed June 10, 2024).

Cutting, J. E. (2021). Movies on our minds: The evolution of cinematic engagement. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Dam, C., Hartmann, B. J., and Brunk, K. H. (2024). Marketing the past: a literature review and future directions for researching retro, heritage, nostalgia, and vintage. J. Mark. Manag. 40, 795–819. doi: 10.1080/0267257x.2024.2339454

Dubourg, E., and Baumard, N. (2022). Why and how did narrative fictions evolve? Fictions as entertainment technologies. Front. Psychol. 13:786770. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.786770

Elliott, R. (2020). “Making up people: consumption as a symbolic vocabulary for the construction of identity” in Elusive Consumption. eds. K. M. Ekström and H. Brembeck (London: Routledge), 129–143.

Ertz, M., Sarigöllü, E., Karakas, F., and Chehab, O. (2021). Impact of TV dramas on consumers’ travel, shopping and purchase intentions. J. Consum. Behav. 20, 655–669. doi: 10.1002/cb.1891

Francis, L. E., and Adams, R. E. (2019). Two faces of self and emotion in symbolic interactionism: from process to structure and culture—and back. Symb. Interact. 42, 250–277. doi: 10.1002/symb.383

Gain Pro (2023) Home furnishing industry, Gain Pro. Available online at: https://www.gain.pro/industry-research/home-furnishing (accessed June 9, 2025).

Gamage, D., Jayasuriya, N., Rathnayake, N., Herath, K. M., Jayawardena, D. P. S., and Senarath, D. Y. (2023). Product placement versus traditional TV commercials: new insights on their impacts on brand recall and purchase intention. J. Asia Bus. Stud. 17, 1110–1124. doi: 10.1108/jabs-04-2022-0126

Gao, X., Hamedi, M. A., and Wang, C. (2024). Cultural distance perceived by Chinese audiences in the Korean film silenced: a study of cross-cultural receptions in film content elements. Front. Commun. 9:1306309. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2024.1306309

Gierzynski, A., Blaber, M., Brown, M., Feldman, S., Gottschalk, H., Hodin, P., et al. (2024). The ‘Euphoria’ effect: a popular HBO show, gen Z, and drug policy beliefs. Soc. Sci. Q. 105, 193–210. doi: 10.1111/ssqu.13351

Guest, G., Namey, E., and Chen, M. (2020). A simple method to assess and report thematic saturation in qualitative research. PLoS One 15:e0232076. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0232076

Hackley, C., and Amy Hackley née Tiwsakul, R. (2012). Observations: unpaid product placement: the elephant in the room in UK TV’S new paid -for product placement market. Int. J. Advert. 31, 703–718. doi: 10.2501/ija-31-4-703-718

Hapsariniaty, A. W., Darmaningtyas, P., Subagio, I., Pratiwi, W. D., and Aswin Rahadi, R. (2019). Culture and domestic spaces: the influence of culture on the interior residential setting. J. Soc Sci. Res. 5, 1816–1827. doi: 10.32861/jssr.512.1816.1827

Hareri, R. H. (2015). Domestic living space furnishings, culture identity, and media. J. Mass Commun. 5:1. doi: 10.17265/2160-6579/2015.01.001

Hennink, M. M., Kaiser, B. N., and Marconi, V. C. (2017). Code saturation versus meaning saturation: how many interviews are enough? Qual. Health Res. 27, 591–608. doi: 10.1177/1049732316665344

Hoxha, V., Metin, H., Hasani, I., Pallaska, E., Hoxha, J., and Hoxha, D. (2022). Gender differences of color preferences for interior spaces in the residential built environment in Prishtina, Kosovo. Facilities 41:11. doi: 10.1108/f-01-2022-0011

Izogo, E. E., and Mpinganjira, M. (2020). Behavioral consequences of customer inspiration: the role of social media inspirational content and cultural orientation. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 14, 431–459. doi: 10.1108/jrim-09-2019-0145

Jain, R. (2024). ‘So, what English do I speak, really?’: A transnational-translingual-and-transracial pracademic inquires into her raciolinguistic entanglements and transraciolinguistic transgressions. TESOL J. 15:784. doi: 10.1002/tesj.784

Janicke-Bowles, S. H., Jenkins, B., O'Neill, B., Thomason, L., and Psomas, E. (2024). Other-focus versus self-focus: the power of self-transcendent TV shows. Psychol. Pop. Media 13, 34–43. doi: 10.1037/ppm0000441

Kallio, H., Pietilä, A. M., Johnson, M., and Kangasniemi, M. (2016). Systematic methodological review: developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide. J. Adv. Nurs. 72, 2954–2965. doi: 10.1111/jan.13031

Kneese, T., Palm, M., and Ayres, J. (2022). Selling in place: the home as virtual storefront. Media Cult. Soc. 44, 362–369. doi: 10.1177/01634437211045348

Kusá, A., et al. (2023). The impact of visual product communication on customers’ irrational buying behaviour. Eur. J. media Art Photogr. 11:6. doi: 10.34135/ejmap-23-02-06

Larsen, G., Lawson, R., and Todd, S. (2010). The symbolic consumption of music. J. Mark. Manag. 26, 671–685. doi: 10.1080/0267257x.2010.481865

Lee, Y. L., Jung, M., Nathan, R. J., and Chung, J.-E. (2020). Cross-national study on the perception of the Korean wave and cultural hybridity in Indonesia and Malaysia using discourse on social media. Sustain. For. 12:6072. doi: 10.3390/su12156072

Liu, Y., Li, K. J., Chen, H., and Balachander, S. (2017). The effects of products’ aesthetic design on demand and marketing-mix effectiveness: the role of segment prototypicality and brand consistency. J. Mark. 81, 83–102. doi: 10.1509/jm.15.0315

Luna-Cortés, G. (2017). The influence of symbolic consumption on experience value and the use of virtual social networks. ESIC 21, 39–51. doi: 10.1016/j.sjme.2016.12.005

McHugh, M. L. (2012). Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem. Med. 22, 276–282. doi: 10.11613/bm.2012.031

Mehrabioun, M. (2024). A multi-theoretical view on social media continuance intention: combining theory of planned behavior, expectation-confirmation model and consumption values. Digital Business 4:100070. doi: 10.1016/j.digbus.2023.100070

Mehta, S. (2020). Television’s role in Indian new screen ecology. Media Cult. Soc. 42, 1226–1242. doi: 10.1177/0163443719899804

Nafees, L., Cook, C. M., Nikolov, A. N., and Stoddard, J. E. (2021). Can social media influencer (SMI) power influence consumer brand attitudes? The mediating role of perceived SMI credibility. Digital Business 1:100008. doi: 10.1016/j.digbus.2021.100008

Nagel, L. (2020). The influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on the digital transformation of work. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 40, 861–875. doi: 10.1108/ijssp-07-2020-0323

Naukkarinen, O., and Bragge, J. (2016). Aesthetics in the age of digital humanities. J. Aesthet. Cult. 8:30072. doi: 10.3402/jac.v8.30072

Nirupama, M. I., Galdolage, B. S., Al-Daoud, K., Vasudevan, A., Mohammad, S., Vasumathi, A., et al. (2025). The effect of conspicuous consumption on social identity formation in the branded clothing sector: the mediating effect of product symbolism. Uncertain Supply Chain Manage. 13, 395–408. doi: 10.5267/j.uscm.2024.9.013

Parutis, V. (2011). ‘Home’ for now or ‘home’ for good? Home Cult. 8, 265–296. doi: 10.2752/175174211X13099693358799

Pavlović-Höck, D. N. (2022). Herd behaviour along the consumer buying decision process - experimental study in the mobile communications industry. Digital Business 2:100018. doi: 10.1016/j.digbus.2021.100018

Piacentini, M., and Mailer, G. (2004). Symbolic consumption in teenagers’ clothing choices. J. Consum. Behav. 3, 251–262. doi: 10.1002/cb.138

Qu, Y., Cieślik, A., Fang, S., and Qing, Y. (2023). The role of online interaction in user stickiness of social commerce: the shopping value perspective. Digital Bus. 3:100061. doi: 10.1016/j.digbus.2023.100061

Redies, C. (2015). Combining universal beauty and cultural context in a unifying model of visual aesthetic experience. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 9:218. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2015.00218

Reimer, S., and Leslie, D. (2004). Identity, consumption, and the home. Home Cult. 1, 187–210. doi: 10.2752/174063104778053536

Rogers, C. J., and Hart, D. R. (2021). Home and the extended-self: exploring associations between clutter and wellbeing. J. Environ. Psychol. 73:101553. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2021.101553

Roy, N., and Gretzel, U. (2022). Feeling opulent: adding an affective dimension to symbolic consumption of themes. Tour. Geogr. 24, 346–368. doi: 10.1080/14616688.2020.1867885

Ryu, S., and Cho, D. (2022). The show must go on? The entertainment industry during (and after) COVID-19. Media Cult. Soc. 44, 591–600. doi: 10.1177/01634437221079561

Sahin, O., and Nasir, S. (2022). The effects of status consumption and conspicuous consumption on perceived symbolic status. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 30, 68–85. doi: 10.1080/10696679.2021.1888649

Seifert, C., and Chattaraman, V. (2020). A picture is worth a thousand words! How visual storytelling transforms the aesthetic experience of novel designs. J. Prod. Brand. Manag. 29, 913–926. doi: 10.1108/jpbm-01-2019-2194

Sheldon, Z., Romanowski, M., and Shafer, D. M. (2021). Parasocial interactions and digital characters: the changing landscape of cinema and viewer/character relationships. Atl. J. Commun. 29, 15–25. doi: 10.1080/15456870.2019.1702550

Sheng, H., Yang, P., and Feng, Y. (2020). How to inspire customers via social media. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 120, 1041–1057. doi: 10.1108/imds-10-2019-0548

Singh, R., and Singh, S. (2024). The cultural codes of home in Indian cinema. Home Cult. 21, 69–87. doi: 10.1080/17406315.2024.2345997

Sivanathan, N., and Pettit, N. C. (2010). Protecting the self through consumption: status goods as affirmational commodities. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 46, 564–570. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2010.01.006

Smitheram, J., and Nakai Kidd, A. (2024). A tiny home of one’s own. J. Mater. Cult. 29, 122–137. doi: 10.1177/13591835231187555

Sun, S. (2023). The interpretation of aesthetic capitalism in the age of new media. Commun. Hum. Res. 9, 205–211. doi: 10.54254/2753-7064/9/20231185

Tangsupwattana, W., and Liu, X. (2017). Symbolic consumption and generation Y consumers: evidence from Thailand. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 29, 917–932. doi: 10.1108/APJML-01-2017-0013

Ulver, S. (2019). From mundane to socially significant consumption: an analysis of how foodie identity work spurs market formation. J. Macromark. 39, 53–70. doi: 10.1177/0276146718817354

Valle Corpas, I. (2021). Between home and flight: interior space, time and desire in the films of Chantal Akerman. J. Aesthet. Cult. 13:1914969. doi: 10.1080/20004214.2021.1914969

Wang, Y. (2023). Exploring the development path of streaming media platforms in the context of globalization --taking Netflix as an example. Commun. Hum. Res. 13, 199–204. doi: 10.54254/2753-7064/13/20230302

Weingarten, E., and Goodman, J. K. (2021). Re-examining the experiential advantage in consumption: a meta-analysis and review. J. Consum. Res. 47, 855–877. doi: 10.1093/jcr/ucaa047

Whiteman, J., and Kerrigan, F. (2024). Film and the stigmatisation of ageing female sexuality: consumer commentary of good luck to you, Leo Grande. J. Mark. Manag. 40, 1–26. doi: 10.1080/0267257x.2024.2383237

Wu, M., Yang, M., Zeng, Y., and Chen, Q. (2021). “Exploring the effects of product placement in movies and its influence on consumer behavior-a case study of the transformers series,” in 7th International Conference on Humanities and Social Science Research (ICHSSR 2021), 732–737. Atlantis Press.

Yan, S.-C. (2018). ‘Our artistic home’: adolescent girls and domestic interiors in the girl’s own paper. Home Cult. 15, 181–208. doi: 10.1080/17406315.2019.1612588

Zahidi, F., Kaluvilla, B. B., and Mulla, T. (2024). Embracing the new era: artificial intelligence and its multifaceted impact on the hospitality industry. J. Open Innov. Technol. Market Complexity 10:100390. doi: 10.1016/j.joitmc.2024.100390

Zaman, S. I., and Kusi-Sarpong, S. (2024). Identifying and exploring the relationship among the critical success factors of sustainability toward consumer behavior. J. Model. Manag. 19, 492–522. doi: 10.1108/jm2-06-2022-0153

Zhang, Z., and Liu, X. (2022). Consumers’ preference for brand prominence in the context of identity-based consumption for self versus for others: the role of self-construal. J. Glob. Scholars Market. Sci. 32, 530–553. doi: 10.1080/21639159.2021.2019600

Zhang, Y., Yang, Y., Yang, R., and Tang, Y. (2022). Offline aesthetic design of restaurants and consumers’ online intention to post photographs: a moderated mediation model. Soc. Behav. Pers. 50, 65–81. doi: 10.2224/sbp.11288

Keywords: media-inspired home décor, symbolic consumption, movies, TV shows, consumer perceptions, nostalgia, interior design, over-the top (OTT)