- 1Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, United States

- 2Department of Linguistics, University of Potsdam, Potsdam, Germany

As human speakers naturally adapt their linguistic styles to one another, voice user interfaces that prompt similar linguistic adaptations can augment human-like interaction. In this study, we leverage a corpus of human instructions to model the effectiveness of incremental instruction generation in artificial agents. Participants interacted with agents that guided them in selecting virtual puzzle pieces, varying the amount of information provided in each instruction. Through an empirical examination of the Gricean maxims in utterance construction, our initial perception study highlighted the significance of adaptive instruction generation. By employing mouse movements as a proxy for user understanding, we developed computational models that enabled agents to detect user uncertainty and refine instructions incrementally. Comparing speaker-based and listener-based models, we found that agents encouraging linguistic adaptations were preferred by users. Our findings offer new insights into the value of mouse movements as indicators of user comprehension and introduce a methodological framework for developing adaptive interactive systems that generate instructions dynamically.

1 Introduction

“Pass me the Vernier, please,” said Jakob. “The what?” asked Frida. “The calliper”, Jakob replied, observing Frida's confusion. “The long metal thing... right in front of you”, continued Jakob. Although this dialogue is only represented in text, it illustrates the richness of an interactional setting and how embodied actions can prompt the reformulation of speech. In task-oriented interactions, speakers collaboratively build common ground—a mutual understanding of shared goals (Clark and Marshall, 1981; Clark and Wilkes-Gibbs, 1986; Fussell and Krauss, 1992; Dafoe et al., 2021). Utterances are constructed in a cooperative manner (Clark, 1996), following a principle known as audience design (Bell, 1984; Brennan and Hanna, 2009).

1.1 Grice's cooperative principle

This process is part of the cooperative principle that Grice defined as the maxim of quantity (Grice, 1975, 1989), which represents efficiency in communication by conveying the most accurate information with the least effort required. Speakers minimize collaborative effort by always seeking positive evidence of understanding, a concept known as the grounding process (Clark and Brennan, 1991; Brennan and Clark, 1996). They construct utterances in an opportunistic approach, incrementally gathering evidence that the criteria for mutual understanding are met (Sacks et al., 1978; Schober and Clark, 1989; Gonsior et al., 2010). Difficult descriptions are often conveyed through episodic utterances or incremental units, where the communicative act itself, rather than the information conveyed, holds the most significance (Krahmer and Van Deemter, 2012). This type of adaptation poses a challenge for interfaces, as it requires them to have robust representations of the interaction state and effectively interpret the user's signals.

1.2 Approach

In this paper, we examine these interactional phenomena by replicating incremental utterance construction in voice user interfaces. We begin with the assumption that there is an alignment between the complexity of instructions and the level of assistance required from the system. Some users may rely less on system cues and are more likely to achieve their goals with systems that adapt to their individual needs (Torrey et al., 2006). While low system effort may lead to misunderstandings, excessive effort could overwhelm the listener (Torrey et al., 2013; Chai et al., 2014; Kontogiorgos and Gustafson, 2021).

We examine this adaptation process from the perspective of common ground. Our approach begins by analyzing a corpus in which humans instruct each other in a task-oriented setting. The annotated instructions were synthesized through a Text-To-Speech (TTS) system and evaluated in the first study to explore the balance of information necessary for task completion. Participants' mouse movements were collected, analyzed, and used as a proxy for utterance comprehension. In a second study, employing Machine-Learning methods, the system automatically assessed participants' understanding based on their mouse movements. This adaptive instruction generation method enabled the system to predict in real-time whether users would successfully complete the task and to adjust the construction of instructions incrementally.

1.3 Research questions

The corpus analysis and two studies address the following research questions:

RQ1: How do human speakers produce instructions in incremental units, and what are their attributes (e.g., timing, duration)?

RQ2: What is the optimal granularity of information that an interface should provide at each incremental unit of a goal-oriented task? Specifically, how does varying the amount and detail of information affect task performance and user understanding?

RQ3: How can the interface dynamically adapt its communication strategy when the user's attention or behavior deviates from the expected interaction pattern?

1.4 Contributions of this article

Our findings indicate that voice user interfaces that utilize incremental instructions can effectively minimize collaborative effort with users. We demonstrate that mouse movements serve as a reliable proxy for utterance comprehension and influence instruction behavior in incremental units. The goal of this paper is to estimate how well this coordination is maintained by predicting, throughout the interaction, whether the user's goal is uncertain (Kontogiorgos et al., 2019). We design a system that adapts to the user's information needs in a virtual puzzle task by providing referential information incrementally (Engonopoulos et al., 2013; Zarrieß and Schlangen, 2016) (Figure 1).

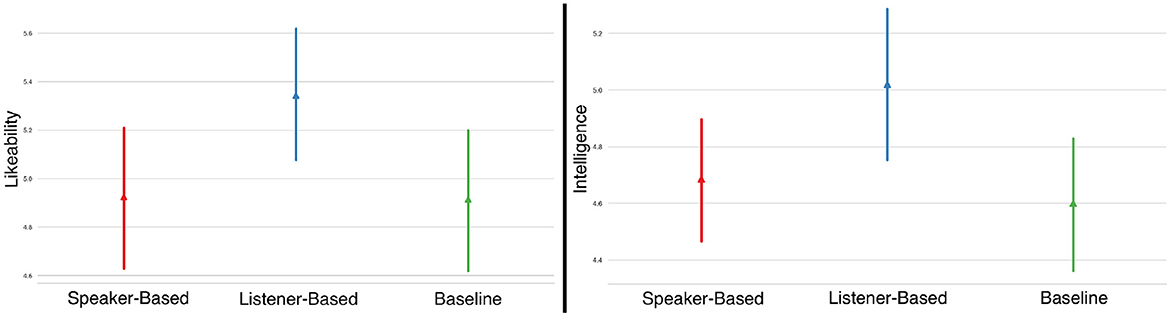

Figure 1. Research design of this study: (1) Extraction of instructions from a dataset of human instructors (Zarrieß et al., 2016). (2) Modeling and synthesizing the extracted instructions, followed by evaluation in an online study (Study 1). (3) Utilizing mouse movement data from Study 1 to train adaptive instruction models, with subsequent evaluation of these models in a perception study (Study 2). (a) Human instructors dataset. (b) Study 1: ML model training. (c) Study 2: human evaluation.

This line of work contributes to empirical findings in linguistic alignment research (Branigan et al., 2010). Specifically, we demonstrate how an interface can exhibit adaptive and collaborative behavior by providing as much information as needed by users. We evaluate three approaches to eliciting adaptive behavior by comparing two interaction strategies: (a) a speaker-based model and (b) a listener-based model, against (c) a control condition where users explicitly request the information they need. Differences are assessed in terms of users' task performance, user behavior, and perceptions of the three agents, providing valuable insights for designing future voice user interfaces that deliver personalized instructions.

1.5 Background and related work

1.5.1 Mutual understanding with voice user interfaces

Incremental language construction behaviors demonstrate the affordances of interaction, showing that mutual understanding can be shaped as a continuous, participatory, and collaborative process (Clark, 1996; Clark and Krych, 2004; Baumann et al., 2013). Like human speakers, voice user interfaces should employ data-driven approaches and adapt their instruction strategies to match users' evolving levels of understanding (Pelikan and Broth, 2016; Kontogiorgos and Pelikan, 2020; Behnke et al., 2020). While much of the HCI research has concentrated on preventing miscommunication with users, it often overlooks that human dialogue is grounded in the cooperative principle (Grice, 1989), characterized by variability in interactional phenomena (e.g., disfluencies, repairs, hesitations) (Kousidis et al., 2014; Buschmeier et al., 2012; Wagner et al., 2015; Haake et al., 2019). Given the inherently social nature of human communication, user interfaces must incrementally monitor users for social cues that signal mutual understanding (Kontogiorgos, 2022), a human-like capability that voice user interfaces currently lack.

1.5.2 Adaptation in cooperative AI

In this paper, we focus on computer adaptation, which is further demonstrated in the two studies presented. We examine adaptation within the domain of referential language,1 particularly in the instructional use of language that describes objects within the shared space of attention between the user and the computer (Axelsson and Skantze, 2020). The user's visual attention is considered in the form of mouse movements to guide subsequent instructions.2

A significant body of research on referring expression (RE) generation in HCI has focused on producing REs as the shortest possible expressions with minimal ambiguity (Dale and Reiter, 1995; Williams and Scheutz, 2017). However, this approach does not fully align with how humans naturally communicate. Humans depend on the cooperation of their conversational partner to resolve ambiguities, constructing descriptions in an opportunistic manner that often results in non-optimal, yet adequate, utterances. These utterances can be repaired and adjusted according to the listener's understanding. This process is inherently collaborative, particularly in interactive settings, where the RE is tailored to the specific listener, and a sequence of utterances is iteratively refined until mutual comprehension is achieved. The objective of this process is to minimize the joint effort, thereby producing REs with the least collaborative effort (Clark and Wilkes-Gibbs, 1986; Clark and Brennan, 1991).

Some HCI research has investigated incremental descriptions or ambiguous instructions across various contexts, including computational studies on situated dialogue among humans (Kelleher and Kruijff, 2006; Dethlefs et al., 2011; Kirk and Fraser, 2017; Magassouba et al., 2018), and visual search (Kraut et al., 2003; Zarrieß and Schlangen, 2016; Li et al., 2020; Rojowiec et al., 2020). This work often involves incremental units (Skantze and Hjalmarsson, 2010; Baumann and Schlangen, 2012; Kennington and Schlangen, 2017; Jensen et al., 2020) or leverages the incremental algorithm (DeVault et al., 2005). Researchers have also incorporated signals like users' eye-gaze (Koller et al., 2012; Staudte et al., 2012; Mitev et al., 2018) and employed paradigms in virtual environments (Stoia et al., 2006; Striegnitz et al., 2012; Garoufi and Koller, 2014). Additionally, instructions have been examined within Human-Robot Interaction (HRI) through human-robot collaborative instruction tasks (Fang et al., 2015; Wallbridge et al., 2019; Doğan et al., 2020; Weerakoon et al., 2020; Wallbridge et al., 2021; Doğan and Leite, 2021) and in robotic navigation (Tellex et al., 2011).

What information interfaces disclose in each incremental unit or which instructional strategies may be most effective has been sparsely explored, primarily within HRI research (Torrey et al., 2006, 2007, 2013; Saupp and Mutlu, 2014; Sauppé and Mutlu, 2015). Collaborative human-AI utterance generation has also been approached through abstraction matching, generating grounded utterances that align with user intent in Python code generation (Liu et al., 2023). Providing explanations as repair strategies has been demonstrated to be effective in conversational interactions (Ashktorab et al., 2019). While this article focuses on the social dynamics of generating utterances incrementally, some research has raised questions about building relationships and bonds in conversational agent communication, favoring a focus on transactional and utilitarian aspects without directly mimicking human-to-human conversation (Clark et al., 2019).

1.5.3 Adaptation in the form of incremental units

Instructions in situated interactions are often composed of multiple fragmentary utterance units, described as a series of corrections (Lindwall and Ekström, 2012). These instructions depend on mutual understanding, from their initial formulation to the iterative process of being reformulated based on the actions of the person receiving the instruction. This adaptation process poses a significant challenge for computers, as they must continuously monitor the user and adjust instructions in real-time. Thus, the generation of instructions should not be viewed solely as information exchange,3 but also as an opportunity to demonstrate socially intelligent behavior.

Such behavior is likely influenced by the speaker's ability to adhere to the cooperative principle and the Gricean maxim of quantity, providing as much information as necessary with as few utterances as possible (Gigliobianco et al., 2024). This approach is also likely intended to minimize collaborative effort (Fang et al., 2015; Kontogiorgos and Gustafson, 2021), with difficult instructions being presented incrementally until common ground is established. One reason for this behavior could be that it is easier for speakers to plan utterances incrementally rather than constructing a single, unambiguous instruction; another reason is the flexibility it provides in adapting to the listener's understanding. This joint orientation of incremental turns is often facilitated through pausing and forming intonational phrases, allowing the speaker to adapt and reformulate instructions as multi-utterance contributions to the conversation (Clark and Wilkes-Gibbs, 1986), in synchrony with the listener's signals of understanding—a challenging task for voice user interfaces.

2 Modeling instructions

2.1 Human instructor corpus

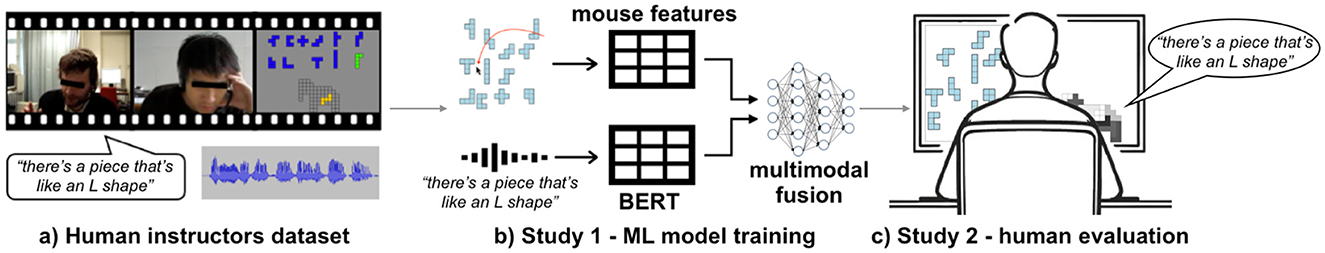

We used a corpus of human instructors from (Zarrieß et al., 2016). The corpus consists of 11 dialogue pairs of native English speakers interacting through video. Their task was to solve a virtual pentomino puzzle, forming shapes such as the elephant shown in Figure 2. The role of the “Instructor” was to guide the “User” participant on how to solve the puzzle.

Figure 2. The collaborative task in the corpus (Zarrieß et al., 2016).

2.2 Instructions in incremental units

The corpus included utterance-level annotations, increment transcripts, and the types of referring strategies used to identify the pentomino pieces (Schlangen and Fernández, 2008). A transcript of a fragment of an interaction is shown below, with the incremental units highlighted in bold:

INSTRUCTOR: letter There's a piece like an L shape.

USER: Mhm, yeah!

INSTRUCTOR: geometrical shape Where you know one piece is longer than the other.

INSTRUCTOR: blocks It's about four units by two units.

USER: This one?

USER: So, you, you can see it when I'm moving it here?

INSTRUCTOR: No. I, I just see the solution, yeah?

INSTRUCTOR: I'm looking at an elephant, believe it or not.

INSTRUCTOR: Okay, so eh.

USER: -laughter-

INSTRUCTOR: elephant solution It's like the back leg.

INSTRUCTOR: location The bottom right of the ... grid.

An important aspect of using human instruction utterances is that they are generated in a collaborative manner. We used the incremental units as templates to generate computer instructions. Instructors typically altered the referring strategy [type of referent attribute (Reigeluth et al., 1980)] with each new increment. We extracted and modeled the incremental units from a total of 3,174 referring expressions.

2.3 Automatic instruction generation

We analyzed the instructions by examining their turn-taking characteristics. The average number of incremental units per instruction was 2.0 ± 1.5, with a minimum of 1 and a maximum of 5 incremental units. The average incremental unit duration was 2.4s±1.6s, with an average of 6.6 ± 6.3 words per unit and a pause duration of 1.4s±2.2s between units. To utilize these utterances in the studies, we filtered the data by selecting the five most frequently used strategies (corresponding to the maximum number of incremental in this corpus). We also removed outliers from the data (e.g., very long pauses, very long utterances) by filtering data points more than two standard deviations away from the mean, resulting in a total of 1,588 utterances.

We then cleaned the utterances for disfluencies or prosodic information included in the annotations. A random set of utterances was selected and checked for coherence. Next, we grouped the utterances and filtered out the referent object to use as templates. Aside from the referent-specific information, the remaining utterance attributes, including the syntactic structure, were preserved as originally spoken by the instructors. The agent only needed to select a human utterance and adjust it to the current referent target.

3 Study 1: The maxim of quantity

We conducted a study with an interface instructing humans to evaluate the effectiveness of the incremental units observed in the corpus. Participants were exposed to two types of stimuli: (i) visual (the pentomino pieces), and (ii) auditory (task instructions).

3.1 Materials and methods

3.1.1 Implementation

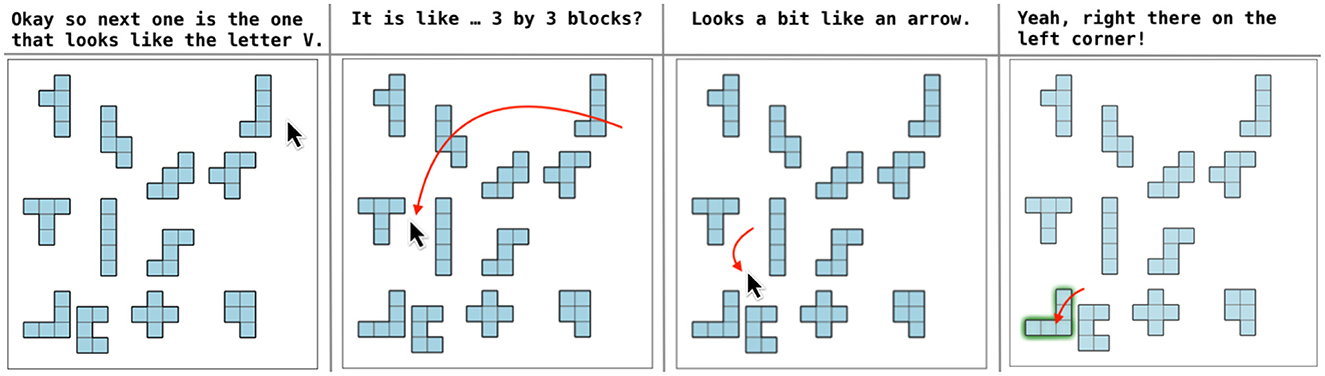

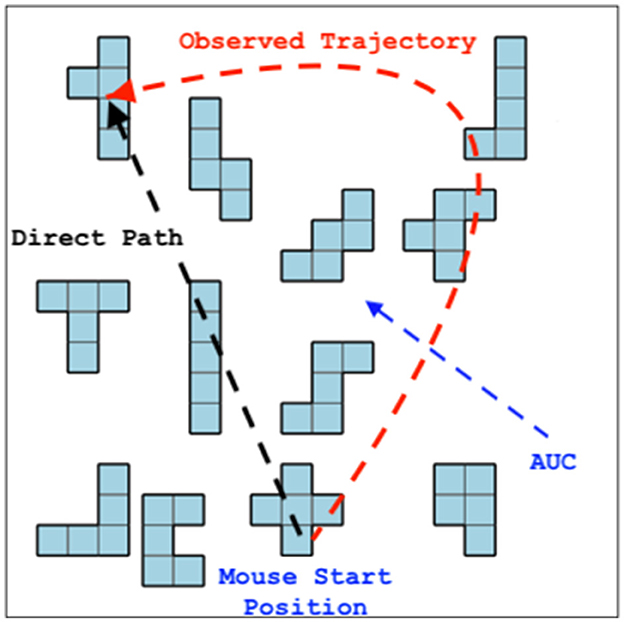

We implemented a web version of the Pentomino task, where each scene included the referent target object among a set of distractor objects. Instructions were generated for each Pentomino and referring strategy using Amazon Polly Text-to-Speech (TTS), and we created the agent Matthew. All participants were exposed to the same stimuli. Task boards were generated with Pentomino pieces randomly positioned (see Figure 3). Matthew delivered an incremental unit for each of the five referring strategies observed in the human corpus (transcript in Section 2.2).

Figure 3. Illustration of a voice user interface incrementally constructing instructions based on the user's signals.

Although current off-the-shelf TTS services provide limited control over prosodic variation (Székely et al., 2019), we manipulated the end of each incremental unit by introducing a rising pitch to suggest that the agent might continue with an additional utterance (Traum and Hinkelman, 1992; Brennan and Schober, 2001). After each unit, the agent paused. To determine the duration of these pauses (Zellner, 1994), we used the timing data (mean and standard deviation) from the human instructor corpus to decide how long to wait before delivering the next incremental unit. While most of the pauses were silent, in some instances, Matthew generated filled pauses (e.g., “uhm,” “uh”), based on their occurrence rate in the human corpus (22% of the pauses). The interface monitored participants' visual attention (Müller and Krummenacher, 2006; Eckstein, 2011) through their mouse movements.

3.1.2 Independent variables

In this study, we investigated the amount of information that needs to be conveyed in instructions. We hypothesized that even when subjects are exposed to the same amount of information, some individuals might be more dependent on the adaptation to their specific information needs. The aim was to estimate the minimal amount of information required to achieve high accuracy and to determine whether additional information is always beneficial or potentially detrimental. We expected to observe a trade-off between the spoken effort exerted by the interface and the users' accuracy in the task.

We manipulated the amount of information provided to subjects by using the minimum (1) and maximum (5) number of incremental units employed by human instructors and tested five variations of instructions. To control for order effects, we also tested each of the five referring strategies appearing first, resulting in a combination of 25 (5 incremental units × 5 referring strategies) instructions for each of the Pentominoes. In total, 300 instructions were evaluated (25 × 12 Pentominoes) using a balanced Latin Square design.

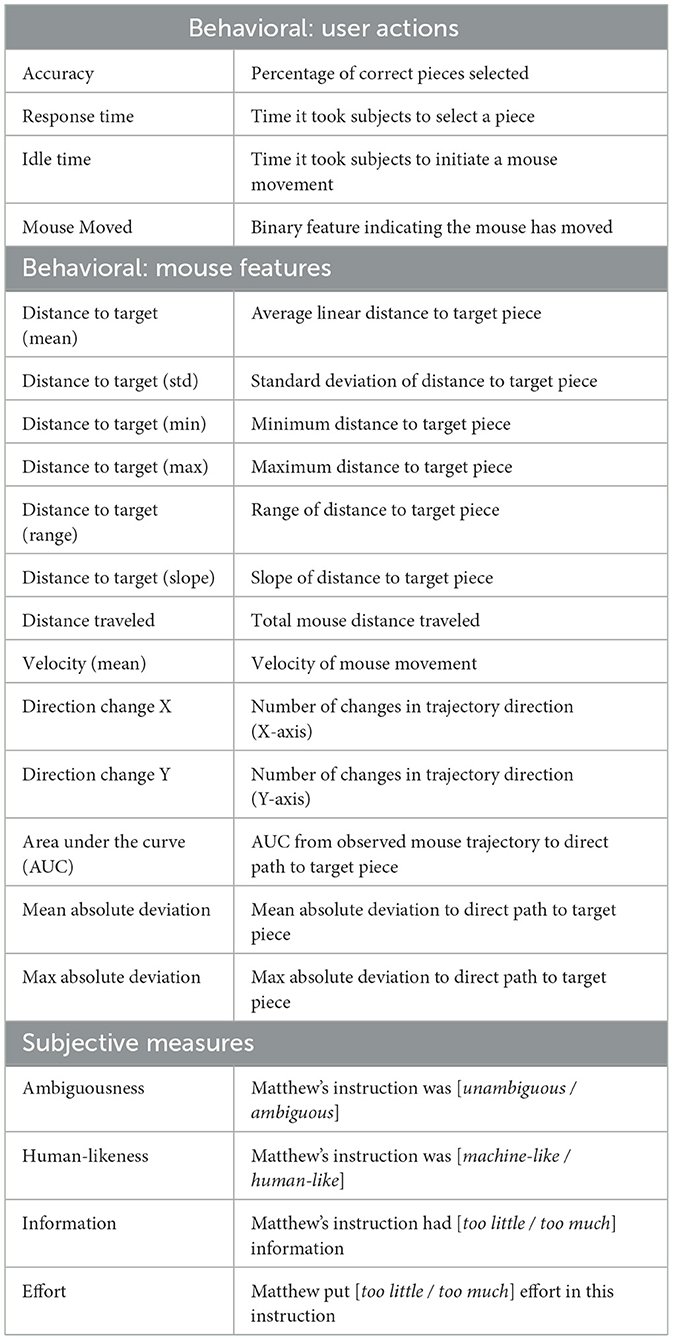

3.1.3 Dependent variables

3.1.3.1 Behavioral measures

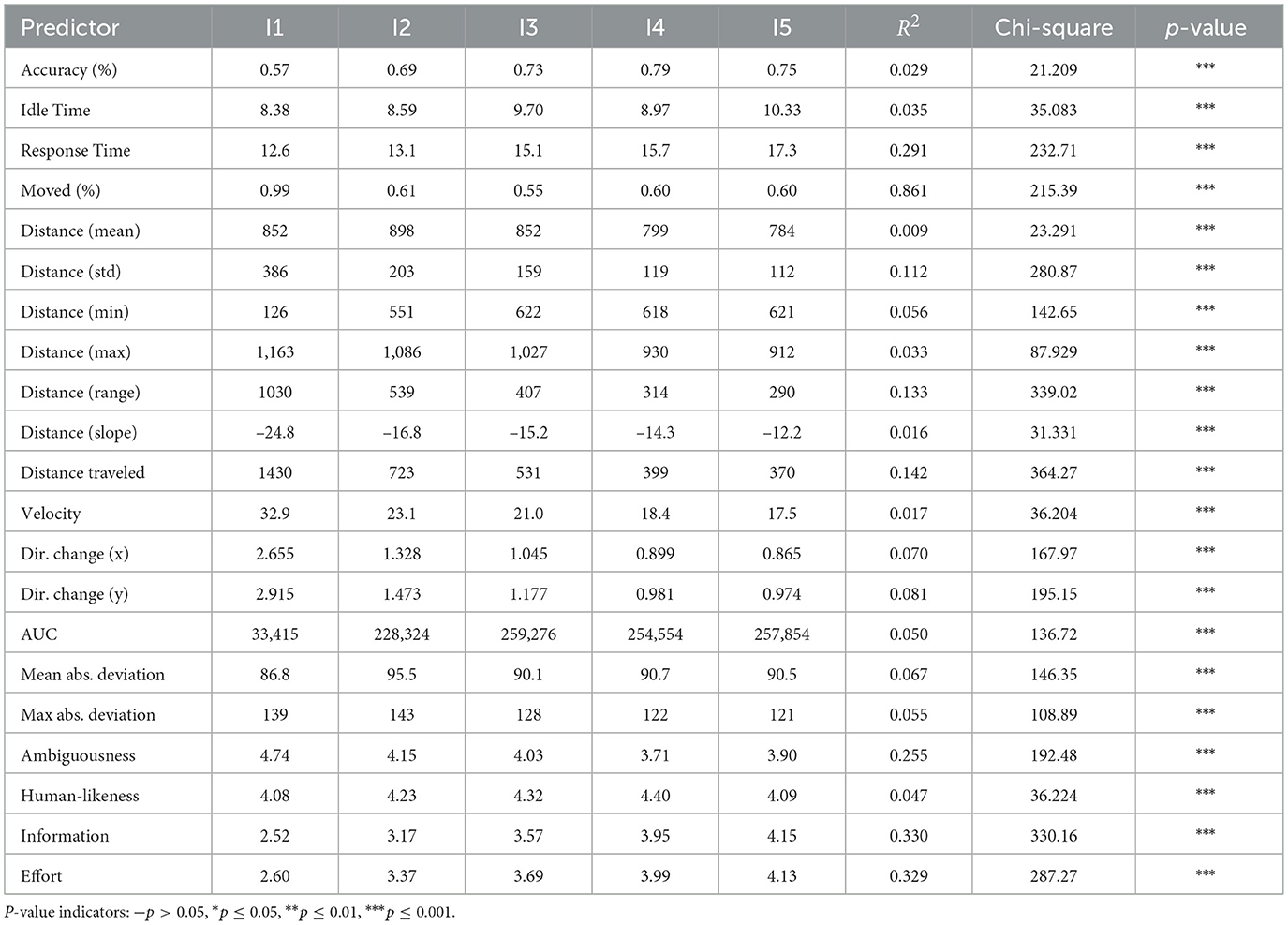

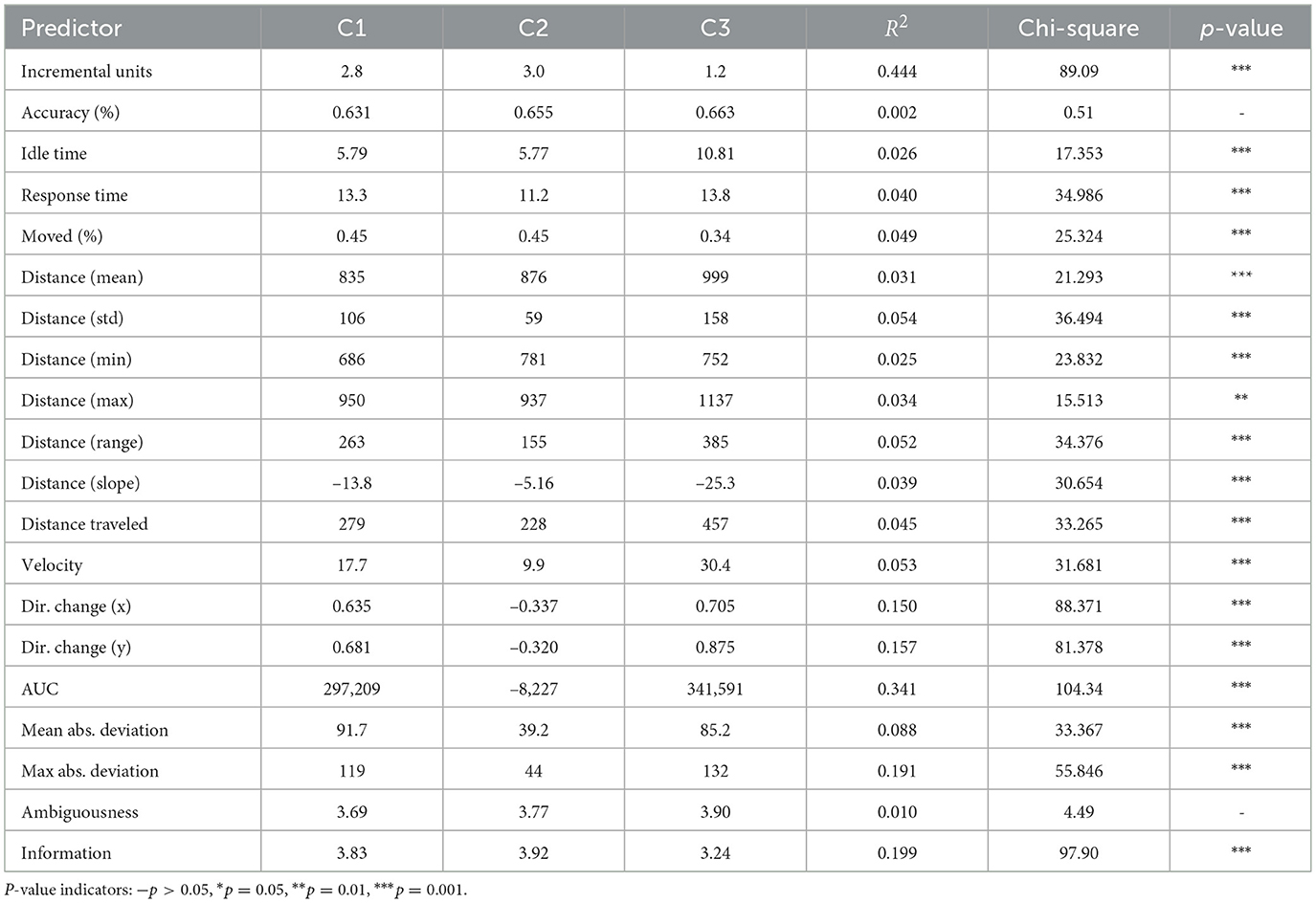

User actions: We measured users' overall accuracy in the task (percentage of correctly identified objects). For each instruction, we also recorded users' response time, indicating the effort spent on visual search, as well as idle time, which represents the time taken by users to initiate a mouse movement, and whether the user's mouse had moved as a binary feature. Mouse uncertainty: For each incremental unit, we also calculated a set of features representing the user's mouse movement uncertainty (see Table 1). These features allowed us to estimate the degree of unpredictability in the mouse movements as a proxy for the user's attention (Fitts, 1954) (see Figure 4). The continuous signal of mouse movements was extracted every 200ms and concatenated to represent the mouse movement during the incremental unit, while also preserving the temporal dynamics; moving away from or toward the target piece can be interpreted as a user's display of understanding. Mouse movements have been utilized in cognitive psychology (Wachsmuth et al., 2008; Tomlinson Jr and Bott, 2013; Tomlinson Jr and Assimakopoulos, 2013; Xiao and Yamauchi, 2014; Calcagǹı et al., 2017; Rheem et al., 2018; Horwitz et al., 2020; Schoemann et al., 2021) to assess cognitive load, as well as in HCI (Whisenand and Emurian, 1999; Mueller and Lockerd, 2001; Ashdown et al., 2005; Arroyo et al., 2006; Guo and Agichtein, 2010; Diaz et al., 2013; Monaro et al., 2017; Kieslich et al., 2019; Krassanakis and Kesidis, 2020) and information retrieval (Guo and Agichtein, 2008; Huang et al., 2011, 2012b; Brückner et al., 2021) to identify user attention and engagement (Johnson et al., 2012; Smucker et al., 2014; Arapakis and Leiva, 2016, 2020; Arapakis et al., 2020; Kirsh, 2020), often showing a correlation with eye movements (Chen et al., 2001; Huang et al., 2012a; Qvarfordt, 2017).

Figure 4. Area under the curve (AUC) of the observed mouse trajectory compared to the direct path toward the referent.

3.1.3.2 Subjective measures

Users were asked to respond to four 7-point Likert-scale questions (see Table 1) regarding the Instruction Appropriateness.

3.1.4 Statistical analyses

We conducted statistical analyses in R (Team, 2009). Using the lme4, lmerTest, glmmTMB packages (Bates et al., 2014), we fitted linear mixed-effects models (LMMs) and generalized linear mixed-effects models (GLMMs) to examine the relationship between the number of incremental units uttered (fixed factor with five levels), instruction correctness (fixed factor with two levels), and the dependent variables. As random effects, we included intercepts for the participants, the pentomino pieces, the referring strategies, and the type of mouse device used. Continuous dependent variables were analyzed with LMMs after log transformation, where appropriate. Binary outcomes were analyzed with GLMMs using a binomial link. We opted for LMMs due to their ability to model variance in the data, such as the variability in mouse behavior across users, using the following notation: DV ~ IncrementalUnits * InstructionCorrectness + (1|Participant) + (1|PentominoOrder) + (1|ReferringStrategy) + (1|MouseType). Model assumptions were validated using the DHARMa package, and effect sizes were reported as standardized β (LMMs) or odds ratios (GLMMs) with 95% confidence intervals. Participants were not restricted on when they could select pieces. For a small subset of the data (11%), participants selected a pentomino before hearing the complete instruction; therefore, we included interruption as a confounding factor to account for this variance in the model. Maximum likelihood estimation tests were used to determine the chi-square and p-values, comparing the null models to the full models.

3.1.5 Procedure and data collection

At the beginning of the task, Matthew asked participants for their informed consent. After each instruction, Matthew indicated whether the instruction was correct and placed the piece on the elephant structure accordingly. At the end of the interaction, Matthew asked participants to provide their demographic data. Participants were debriefed on the study's purpose and the experimental manipulations.

Eighty participants were recruited online (Eerola et al., 2021). Five participants did not fully complete the task or experienced technical issues and were excluded, resulting in a total of 75 participants. The participants evaluated a total of 900 instructions, with 2,700 incremental units used as data points in the statistical and machine-learning models. The mean age of the participants was 31.8 (±6.9) years, with 30 identifying as female and 45 as male. Their self-reported English fluency was 6.3 (±0.9) on a scale of 1 to 7. The task took, on average, 18.0 (±8.2) minutes to complete, and each instruction lasted, on average, 11.8 (±5.2) seconds. Forty-four participants used a mouse, while 31 participants used a trackpad.

3.1.6 Manipulation check

Since the stimuli used were synthesized human instructions, we had limited control over the amount of information conveyed in each incremental unit. We used the number of words spoken as a proxy for the information transmitted to determine whether the stimulus was consistent across incremental units. Fitting linear mixed-effects models indicated that there were no significant differences in the number of words spoken per incremental unit (6.9 ± 3.5): χ2 = 1.42, p>0.05, with a marginal R2 of 0.001, suggesting that each incremental unit carried approximately the same amount of information (as indicated by the number of words). To further assess the informational similarity between utterances, we computed the average pairwise semantic similarity using Sentence-BERT embeddings (all-MiniLM-L6-v2) and cosine similarity, which yielded a mean value of 0.29, indicating that the utterances were moderately similar in meaning; not identical, yet sharing some overlap in informational content across incremental units. However, it remains subjective as to what information is considered ambiguous in this paradigm, which we aim to evaluate in this study.

3.2 Results

3.2.1 Behavioral measures

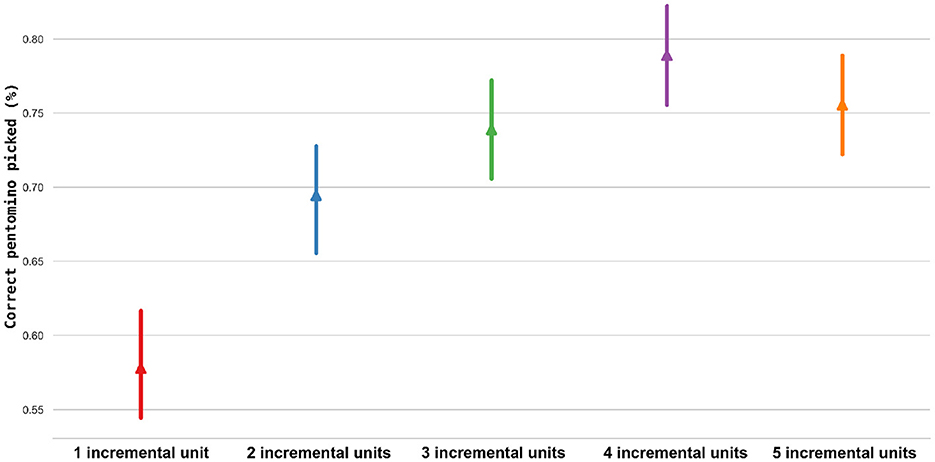

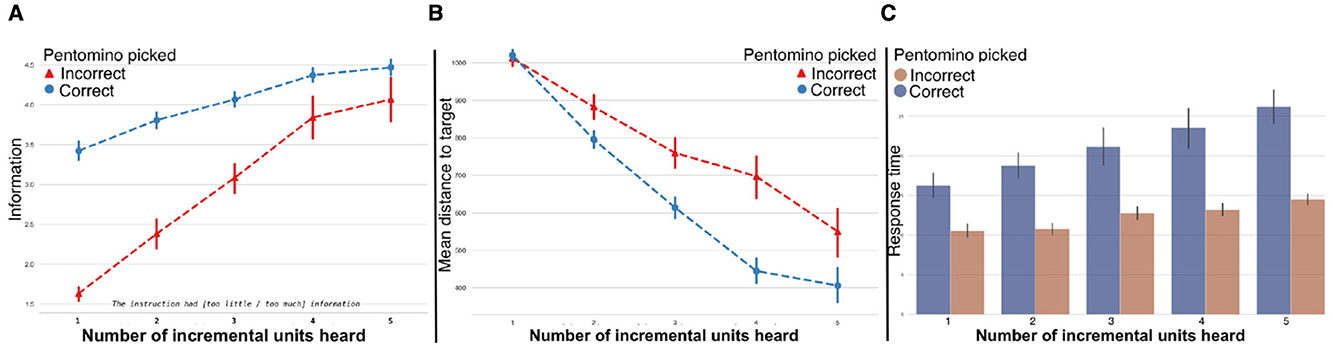

Effects of user actions: Accuracy. On average, participants had an accuracy of 70.8%, with 8.5 (±1.4) out of 12 referents correctly identified. Fitting generalized linear mixed models revealed a statistically significant difference in the number of correct pieces identified per incremental unit (see Figure 5), with the mean values presented in Table 2, indicating that more information presented led to better performance, however without a clear indication of additional information being perceived as overwhelming. We also tested the effect of referring strategies order, which showed a statistically significant impact: χ2 = 27.87, p < 0.001. Idle & response time. The mean idle time was 9.09 (±10.2) seconds, and the mean response time was 14.7 (±11.4) seconds. LMMs (with log transformation) indicated that both idle and response times were statistically different across incremental units, with a rising trend in time (see Table 2 and Figure 6). The models also showed that users were faster at selecting pieces when they selected the correct piece. Through GLMMs, the Mouse moved measure was found to be statistically different across incremental units, with users' mouse movements starting early during the instruction (see Table 2).

Figure 5. Users' accuracy in identifying the correct pentomino pieces per incremental unit. Based on the number of incremental units spoken, the interface can estimate the probability of the user correctly identifying the referent.

Table 2. Behavioral and subjective measures for each incremental unit, with unit means (1-5) comparing the null model to the full model.

Figure 6. (a) Perceived information amount separated by correctness. (b) Mean distance to target, indicating the probability of the mouse position being on or close to the target. (c) Response time separated by correctness.

Effects of mouse uncertainty. Linear mixed-effects models revealed statistically significant differences in how participants utilized mouse movements and how uncertainty was expressed when selecting pieces during each incremental unit (see Table 2 and Figure 6). Consistent with users' accuracy in the task, mouse movements indicated that less uncertainty was associated with a higher number of incremental units spoken by the interface.

3.2.2 Subjective measures

Fitting linear mixed-effects models on Instruction Appropriateness revealed statistically significant effects on how incremental units were perceived (see Table 2). The findings indicated that there were differences in how the amount of information and ambiguity were perceived, with selection accuracy influencing whether or not participants believed additional information was necessary. Perceived information amount was strongly affected by whether a user made a correct selection (see Figure 6); however, the actual amount of information provided remained constant, regardless of the user's performance.

3.3 Estimating user uncertainty

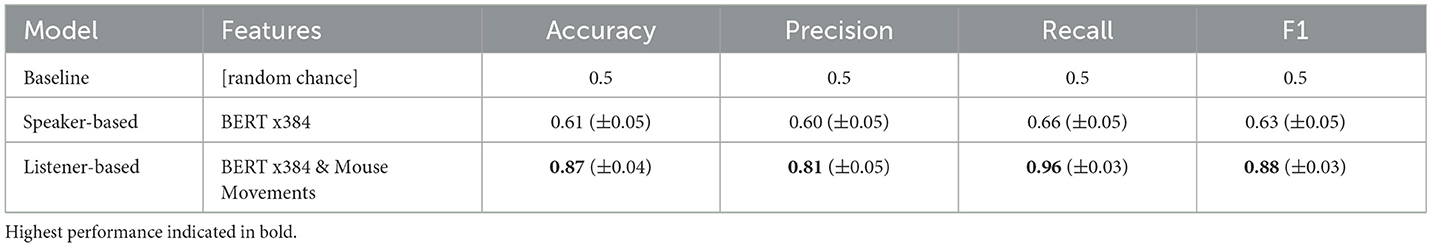

To estimate whether each instruction was ambiguous, we trained two Random Forest (RF) classifiers using the Scikit-Learn framework (Pedregosa et al., 2011). We selected RFs for their robustness against overfitting and their interpretability in identifying the most informative features. Using mouse features, we were able to estimate user uncertainty and predict whether users were likely to succeed. The first model was a speaker-based model, where the system ‘looks back' at what it has said and predicts whether the reference will be successful. We employed Sentence-BERT (Reimers and Gurevych, 2019) to convert each instruction into a 384-dimensional vector. The second model was a listener-based model that incorporated both the instruction embeddings and the user's mouse movements (see Table 1). Both models utilized these features to estimate the user's confidence in their selection; an adaptive interface with this knowledge can incrementally determine whether the user requires additional information.

To better understand the models, we calculated the most informative features in the classification task. Both classifiers were evaluated using subject-independent 10-fold cross-validation. For each incremental unit, we utilized the users' piece selections as ground truth in the models. The underlying assumption is that either the user's attention or the adequacy of the incremental unit contains information that leads to correct actions, which a machine learning model can leverage.

A total of 900 instructions were used. The models extracted features within the sampling window between incremental units. Since the classification classes were imbalanced, we applied the Scikit-Learn resampling method (Pedregosa et al., 2011) to re-sample the majority-class segments, balancing the dataset. This process resulted in 1,266 data points, with an average sampling window of 5.6 (±7.5) seconds (between turns) and a total duration of about 2 h of mouse-movement data. For evaluation metrics, we report the average Accuracy of the models, as well as Precision, Recall, and F1 scores.

3.3.1 Speaker-based model

Using the semantic representations, the speaker-based model simulated a human speaker self-repairing their utterance (Kontogiorgos et al., 2019), essentially evaluating whether it was a good instruction based on its linguistic features. Hyperparameters for the Random Forest model were optimized using grid search: [max-depth = 110, max-features = “auto,” min-samples-leaf = 4, min-samples-split = 10, n-estimators = 100]. The results, presented in Table 3, show better-than-chance accuracy, although relatively low.

3.3.2 Listener-based model

The hyperparameters for the listener-based model were optimized using grid search: [max-depth = 100, max-features = “auto,” min-samples-leaf = 3, min-samples-split = 12, n-estimators = 100]. This model yielded better results (see Table 3), indicating that paying attention to the listener may better simulate human speaker behavior. A post-hoc examination of the model's features revealed that the mouse features combined had an F-score of 0.67, compared to 0.33 for the linguistic features.

3.4 Discussion

The focus of this study was to investigate the maxim of quantity (Grice, 1975), specifically the amount of relevant information presented to participants to successfully disambiguate referring expressions. The findings indicated that information adaptation is crucial, as users require utterances adapted to their information needs. The fact that users rated the information received differently is a significant insight for information adaptation, suggesting that they assess the amount of perceived information based on their task performance rather than the actual information received.

While we initially expected that providing more information might overwhelm users, the results did not clearly support that assumption, as users' accuracy did not consistently reflect this effect. We also observed differences in idle and response times; participants with higher accuracy responded more quickly, indicating that slower response times were associated with higher cognitive effort.

We also observed statistically significant differences in how participants rated the interface. We had predicted that users would not always achieve high accuracy, as the instructions provided were sometimes incomplete. However, focusing solely on accuracy could lead to designing an agent that continuously provides information until all ambiguity is resolved, regardless of how overwhelming this might be for users. This highlights a challenge that socially intelligent agents must address: maximizing accuracy while minimizing collaborative effort (investigated in Study 2).

Finally, the two prediction models estimated user uncertainty, demonstrating strong performance in identifying which types of features (linguistic vs. behavioral) an interface should focus on to deliver incremental units where turn transitions are “relevant” (Sacks et al., 1978).

4 Study 2: The principle of least collaborative effort

Study 2 investigated how to elicit adaptive behavior through instructions using the models trained in Study 1. A significant difference between the two Studies was that Study 2 examined adaptive instruction strategies, while Study 1 utilized predetermined structures of instructions evaluated by users.

4.1 Materials and methods

4.1.1 System design

We utilized the same web application, modified to incorporate the ML models. We took a new sample of the human instructions and synthesized them using the same TTS method described in Study 1. We created three agents (Kevin, David, and Peter), each corresponding to a variation of the three models evaluated. Each agent began with a single incremental unit and then monitored the user to determine whether additional information was necessary. The order of referring strategies was based on their frequency of usage in the human corpus. We deployed the machine-learning models on the interface using the Sklearn-Porter open-source framework (Morawiec, 2021).

4.1.2 Independent variables

We evaluated three separate models for planning spoken instructions. We hypothesized that a model that monitors the user would have an advantage over a model that only monitors what is being spoken. We compared these two models to a control condition in which users actively indicated whether a new instruction unit should be spoken (Tell-Me-More). A total of 60 CUI instruction units (same for each condition) were evaluated (5 incremental units × 12 Pentominoes). This study aimed to examine the optimal model for providing instructions, investigating whether adaptive models that follow the principles of least collaborative effort offer a benefit in the interaction.

4.1.2.1 Adaptive baseline (Tell-Me-More)

This interface only responded to the need for additional information when manually prompted by the user. Using the same pausing behavior, the interface displayed a Tell-Me-More button at the end of the pause, waiting for the user to indicate if a new instruction unit should be spoken. Pressing the button can be seen as the user's continuous attempt to establish common ground (Garoufi et al., 2016). Users received a higher payment for correct answers across all conditions; however, in this baseline, they were informed that each press of the button would reduce their bonus payment. Through this process, users aimed to achieve as many correct answers as possible with the minimal amount of information required.

4.1.2.2 Speaker-based model

We extracted and employed the speaker-based model from Study 1. As long as the model predicted that the participant was unlikely to be successful, it would respond with phrases like “no”, “not this one”, or “hm” before proceeding to the next instruction unit (Rookhuiszen et al., 2009; Mitev et al., 2018). When the model predicted that the user would be successful, it would respond with “yeah”, “yes”, or “yup”, followed by the next instruction unit. We anticipated that the low accuracy of this model would induce additional uncertainty in user behavior.

4.1.2.3 Listener-based model

This model not only evaluated its own utterances as the speaker-based model but also monitored users' mouse movements using the same features as in Study 1 as input. It utilized the same feedback behavior as the speaker-based model based on its predictions. As this model was adaptive to the user, we predicted that it would result in less uncertainty in user actions, as indicated by mouse movement behavior.

4.1.3 Dependent variables

4.1.3.1 Behavioral measures

For each model, we measured user actions and mouse features as outlined in Table 1. We also compared system behavior, including the number of incremental units uttered per model, as well as model predictions in relation to the number of times the Tell-Me-More button was pressed by users.

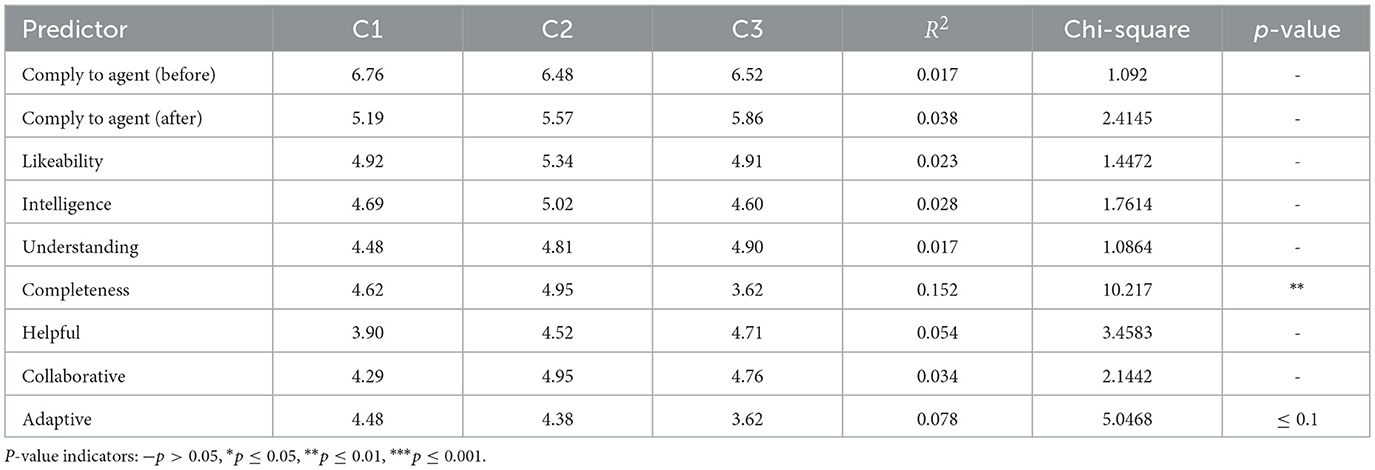

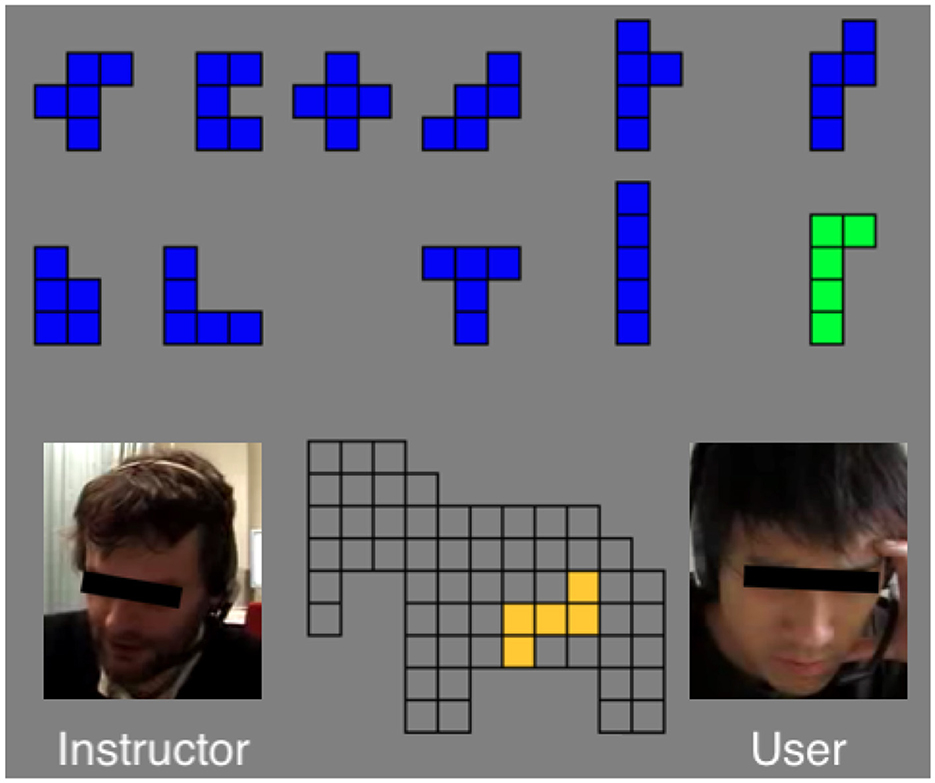

4.1.3.2 Subjective measures

Users rated each instruction for appropriateness using two questions from Table 1: Ambiguousness and Information. System perception: At the end of the interaction, users evaluated the agent, focusing on Instruction Comprehension and whether the instructions were perceived as Understood, Complete, Helpful, and Collaborative. We also measured the Agent Rating using two items from the Godspeed questionnaire (Bartneck et al., 2008) related to Likeability and Intelligence. Finally, we added an adaptivity item to assess how well each model was perceived to adapt to users.

4.1.3.3 Procedure and data collection

The agents followed the same procedure as in Study 1. A total of 71 participants were recruited online. Eight participants were excluded due to technical issues or failure to adhere to study requirements, resulting in 63 participants (21 in each model, using a between-subjects design). The mean age of the participants was 26.9 (±5.9); 39 identified as female, 23 as male, and 1 preferred not to answer. The self-reported English language fluency was 5.7 (±0.9). The task took, on average, 11.4 (±5.0) minutes to complete; 33 participants used a computer mouse, and 30 participants used a mouse trackpad.

4.2 Results

As in Study 1, linear mixed-effects models were utilized, incorporating the same fixed and random factors.

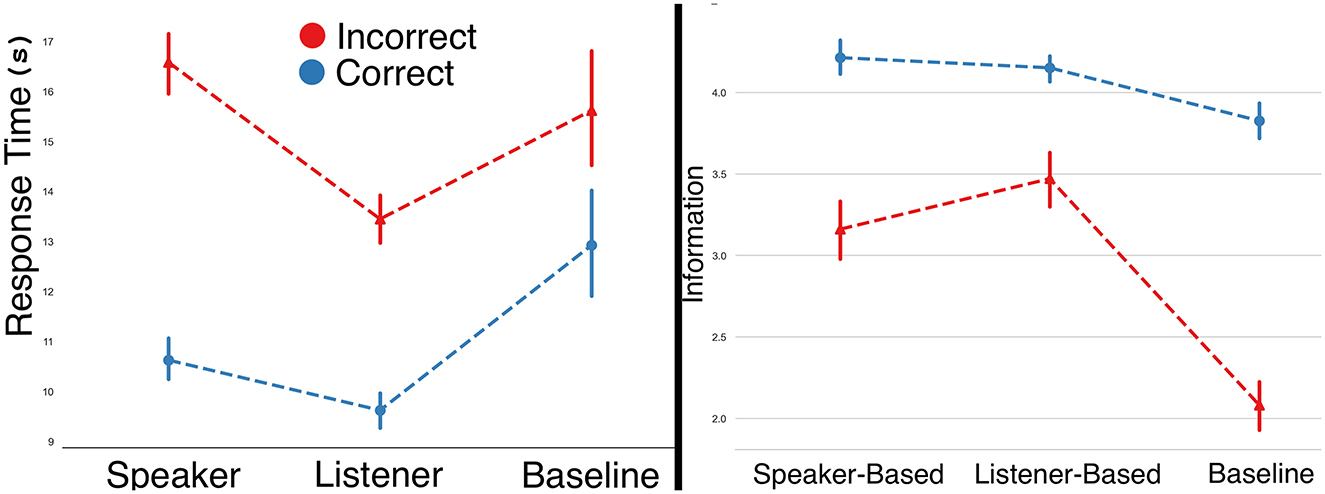

4.2.1 Behavioral measures

4.2.1.1 Effects of user actions

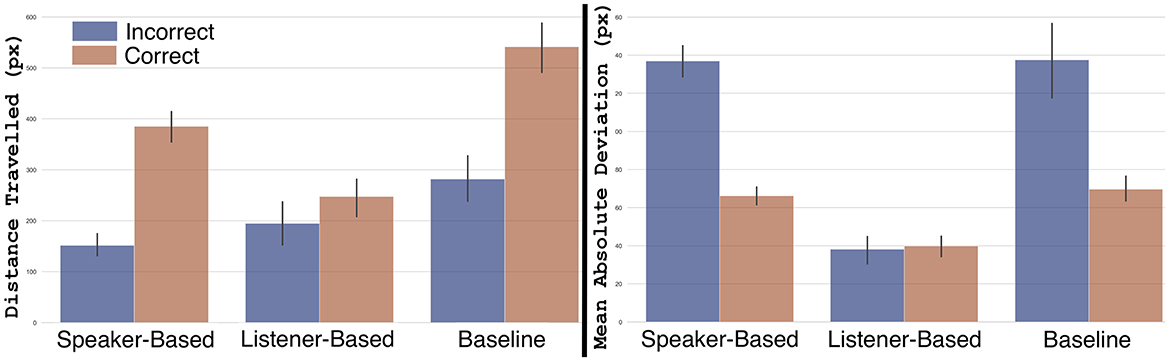

Accuracy. Participants had an overall accuracy of 64.9%. GLMMs did not show a significant difference in user accuracy among conditions (see Table 4). Idle & response time. The mean idle time was 6.6 (±10.3) seconds, and the mean response time was 12.5 (±10.3) seconds. Log transformations for both idle and response times were statistically different across conditions, with users acting faster when they provided correct answers and also faster when interacting with the listener-based model. Bonferroni corrected pairwise comparisons showed that both the speaker-based and listener-based models led to faster responses by users compared to the adaptive baseline (see Table 4 and Figure 7).

Table 4. Behavioral and subjective measures for each condition (c1: speaker-based model, c2: listener-based model, c3: adaptive baseline).

4.2.1.2 Effects of user uncertainty

LMMs revealed statistically significant differences in how participants utilized mouse movements across conditions (see Table 4 and Figure 8). The results indicate that mouse movement uncertainty is lower in the listener-based model.

Figure 8. Mouse trajectory distance traveled and mean absolute deviation to target, separated by accuracy.

4.2.1.3 Effects of system behavior

LMMs revealed a statistically significant difference in the number of incremental units per condition, also considering the user's correctness, as shown in Table 4. Bonferroni corrected pair-wise comparisons indicated that a significantly lower number of incremental units were uttered with the baseline condition. We calculated the model accuracies aggregated by user (0.623 for the Speaker-Based Model and 0.560 for the Listener-Based Model), which indicated that the Speaker-Based Model had a better prediction match with actual user accuracy. In the adaptive baseline, users requested additional information 25.4% of the time, resulting in significantly fewer spoken installments compared to the two models.

4.2.2 Subjective measures

4.2.2.1 Instruction appropriateness

LMMs partially revealed statistically significant effects on how the incremental units were perceived, using condition and correctness as fixed factors (see Table 4 and Figure 7). We observed differences in the perceived amount of information, with the baseline condition having the lowest perceived information overall, according to Bonferroni-corrected pairwise comparisons; user accuracy also influenced whether they felt additional information was necessary.

4.2.2.2 System perception

LMMs partially revealed significant effects on how each agent was perceived (see Table 5 and Figure 9). Bonferroni-corrected pairwise comparisons showed that the instructions provided by the listener-based model were perceived as the most complete, while those from the adaptive baseline were perceived as the least complete.

4.3 Discussion

The findings in this study indicated that adaptation is necessary, with behavioral and subjective preferences leaning toward the listener-based model, even though no significant differences were observed in task accuracy compared to the speaker-based model. Adaptivity in this context may imply not just improving accuracy with more data but also the ability to dynamically adjust data usage based on user need. Both models were preferred over the adaptive baseline. We observed statistically significant differences in how participants rated the amount of information they received; the baseline condition was rated with the lowest amount of information, while the listener-based model was rated with the highest amount, corroborated by the highest number of incremental units overall. Users rated the listener-based model's instructions as the most complete, indicating favorable outcomes in user adaptation; however, no significant differences were found in likeability and intelligence.

Less uncertainty was observed in the listener-based model, as well as when users provided correct answers. The idle and response times also suggested lower cognitive load with the listener-based model, with both models overall performing better than the baseline, which required more effort from the user. Aligning with the listener-based model, users' mouse behavior indicated less uncertainty, even though they were not aware of which model was actually considering their mouse movements. The comparison between a speech-only model and a speech-and-mouse model is valuable for analytical purposes. These models are not in direct competition; rather, the comparison helps us understand the relevance of mouse movements in constructing incremental speech. Even though user accuracy was consistent across conditions, the speaker-based model was somewhat better at predicting whether the user would answer correctly.

5 General discussion

5.1 Key findings

5.1.1 RQ1: How do human speakers produce instructions in incremental units?

We observed in the human instructor corpus that instructions are constructed collaboratively and are often incomplete, including errors in production and variations in pauses. The main outcome of the corpus analysis was that speakers consistently adapt their instructions based on their listeners' signals of understanding, and the main goal is to train models of user uncertainty based on mouse movements. Through the corpus, we also identified the fundamental attributes of instructions, such as timing and pauses. The analysis further revealed the presentation of speech through continuing contributions, as well as “meta-communicative acts,” such as the user's public display of understanding, which we define in our studies through mouse behavior. These incremental units represent the joint project between the interface and the user to establish common ground. We can conceptualize instructions as the intention of the instructor to refer to a specific part of the assembly, with incremental units serving as the continuing contributions that achieve that goal.

5.1.2 RQ2: How much information should an interface convey in each incremental unit?

Study 1 investigated information as the main variable, specifically exploring whether replicating the behavior of humans adjusting their instructions to their listeners' information needs has an impact when implemented in a machine. The findings indicated that information plays a significant role in users' accuracy in the task, as well as in their displayed uncertainty. Classification accuracy was used as a proxy for the quality of each model; however, it did not fully capture the model's effectiveness or how it was perceived by users, which was addressed in RQ3.

5.1.3 RQ3: How should the interface adapt its instructions if the user's attention does not meet the expected behavior?

RQ3 was examined through a user study that compared three adaptive models of constructing instructions. We predicted that differences in users' accuracy in the task would be observed if the appropriate model adapted to their information needs; however, task accuracy did not appear to differ by model. Nevertheless, we did observe differences in user behavior, with the listener-based model prompting less uncertainty. Instructions from this model were perceived as more complete, even though the incremental units were identical across all conditions. Comparing the three models showed that ‘observing user signals recurrently gives interfaces the advantage of planning utterances collaboratively, with the user being part of the process' (Kontogiorgos, 2022).

5.2 Implications for adaptive user interfaces

We use voice rather than text as the medium of communication because instructions in incremental units have primarily been observed as a conversational phenomenon. Voice also allows the user to focus on visually scanning for the referring objects while receiving information incrementally. Therefore, these findings have implications primarily for conversational user interfaces in task collaboration settings, as well as teaching and instructional interfaces utilizing mouse movements. While not tested in this study, such instructional behaviors are important for embodied interfaces that observe the users' embodied signals when uttering instructions. Instructions in incremental units provide an opportunity to convey social behavior, which may be expected by human users, even when the interlocutor is a computer. Similar to the use of discourse markers, displaying information incrementally may help to mitigate directness, balancing between brevity and information exchange as a politeness strategy (Goodman and Stuhlmüller, 2013; Yoon et al., 2016).

However, presenting information incrementally may not always be preferred by users, depending on the interface's utility and the changes in the user's state (e.g., during emergencies). Additionally, different users may interpret incrementality in various ways, meaning that the interface must also consider users' personality traits and what they perceive as efficient vs. polite communication. Recognizing that a turn unit is more flexible than “push-to-talk” interactions (Fernández et al., 2007) enables the possibility to co-construct instructions with the user (Kontogiorgos and Gustafson, 2021).

5.3 Limitations and future work

In this paper, we used a set of puzzle pieces to study incremental utterance production. Similar to the Tangram puzzles used in psycholinguistics, the Tetris-like Pentomino shapes lack the appearance of common objects, making them a suitable paradigm for examining linguistic alignment when people collaboratively develop new terms to describe objects. Each step in the puzzle is grounded incrementally, making it ideal for investigating computer-generated incremental instructions. This constrained nature of the task offers an advantage in examining instructions and provides a level of control over how conversational phenomena evolve. While our findings provide novel insights into utterance construction, they should be interpreted with caution. The collaborative nature of the task may limit generalization to other forms of conversation, such as “open-world dialogues” (Bohus and Horvitz, 2009), which are not object-focused and may not involve collaboration. Nonetheless, the parallel to real-world tasks can be drawn to any machine-guided assembly, whether it involves building IKEA furniture or receiving instructions through a visual interface.

In this article, we used a speaker-and-listener modeling approach to facilitate mutual understanding. However, a much simpler model could use delays in task progress as a proxy for a lack of grounding; when a user does not respond to an instruction, the system can assume that the instruction was either not heard or not understood. Since common ground is a “feeling” among speakers, it can be challenging to methodologically establish a ground truth for what is understood by users (DeVault, 2008). While we can confirm that each incremental unit is heard, we cannot ensure that it is also understood (as shown in the lack of significant findings on accuracy in Study 2).

An important limitation of this work has been the use of prosody. We employed standard TTS services that are not designed for co-constructed speech; instructions in incremental units are a conversational phenomenon where appropriate intonation carries pragmatic information, such as signaling that information may be incomplete or inviting the listener to participate in its construction. Current TTS services lack this flexibility, which may have influenced how users perceived the agents' adaptation to their behavior.

Additionally, the utterances were originally spoken by human instructors and constructed collaboratively; it is inherently subjective what information is ambiguous, as all human instructions are, to some degree, ambiguous and incomplete. User uncertainty was treated as the user's attempt to express clarification requests, which often leads to utterance reformulation rather than the provision of new information (Schlangen and Fernández, 2007). In this work, however, we chose to always present new information. Future research should investigate how to repair utterances when user uncertainty is detected and explore sequential learning of linguistic strategies based on the state of the user and the environment (Ekstedt and Skantze, 2020; Sadler et al., 2023; Sadler and Schlangen, 2023), as well as alternative architectures to speaker-based and listener-based models. Future work should also consider the impact of such proactive interfaces that may have implications for the user's task workflow interruption, as well as approach incremental unit construction through the principles of mixed-initiative user interfaces (Horvitz, 1999).

Finally, participants were mainly young adults, fluent English speakers, which limits the generalisability of our findings. Assistive technologies intended for older adults may face different interaction needs, communication styles, and attentional patterns. Future work should therefore validate the proposed approach with older adult populations to assess its applicability to age-related assistive settings.

5.4 Real-world applications

The approach of using mouse movements as implicit signals of user understanding offers significant potential for real-world applications in domains requiring multitasking interactions. In assistive technologies, adaptive voice interfaces could monitor subtle interaction cues (e.g., cursor hesitation) to adjust the timing, complexity, or repetition of instructions. Outside the mouse-movement domain, in smart home environments, where users may interact with devices while engaged in physical tasks, such interfaces could reduce cognitive effort by incrementally delivering guidance and monitoring non-verbal cues such as eye gaze, hand gestures, or interaction delays.

Beyond individual tasks, this research can be applied in collaborative or instructional settings, such as remote education, collaborative design platforms, or training simulators. In these settings, systems that detect user uncertainty through behavioral signals can better support novice users by tailoring information delivery to their comprehension level. For example, in remote technical support, systems can detect whether the user is struggling with a step and proactively offer clarification without requiring explicit feedback. In human—robot collaboration, detecting hesitation or misalignment in operator behavior can help robots adjust their verbal instructions or actions in real time.

As the puzzle task used in this study offers experimental control but may limit ecological validity, future work should investigate how these findings transfer to more naturalistic environments and more diverse input modalities. Particularly, integrating implicit cues beyond mouse trajectories, such as gaze behavior, body orientation, or hesitation in speech, may improve robustness and generalisability in real-world applications.

6 Conclusion

In summary, this article presented: (i) an analysis of the attributes of human incremental instruction, (ii) empirical evidence demonstrating the benefits of adapting the delivery of information to user behavior, and (iii) a user study showing that mouse movements are a reliable implicit indicator of uncertainty. To the best of our knowledge, this work is the first to utilize real-time turn-taking decisions based solely on users' mouse movements. We also showed that users' movement patterns reveal potential ambiguities in instructions, which a voice user interface can leverage to adjust its guidance.

Taken together, our findings demonstrate that process adaptivity, rather than outcome differences, improves the interaction dynamics of incremental guidance systems. While overall task accuracy did not differ significantly between models, systems that adapted their timing and information granularity in response to users' behavior led to smoother interaction, reduced idle time, and more favorable user perceptions. This highlights the importance of monitoring ongoing behavioral cues to maintain mutual understanding during action execution.

The analysis of human incremental instruction provides insights into how humans structure assistance and how such strategies can be operationalised in intelligent interfaces. These results have practical implications for the automatic generation of human-like, responsive instructions in assistive and collaborative systems. More broadly, this article contributes to a central challenge in HCI: how to assess and maintain common ground incrementally as interaction unfolds.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

DK: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation, Software, Visualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Validation, Data curation. DS: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Resources, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was partially supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG) project RECOLAGE (423217434) and a PostDoctoral Research Fellowship by the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Jana Götze, Karla Friedrichs, Hannah Pelikan, and Joakim Gustafson for contributing to the discussions on earlier versions of this study, as well as the reviewers for constructive feedback on earlier versions of the paper.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomp.2025.1634228/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^Referring expressions (REs) are utterances that often involve language identifying entities in the physical space (e.g., “this one here”) or abstract entities (e.g., “Grace Hopper was here”) (Isaacs and Clark, 1987).

2. ^For an overview of visual search and attention, see the work of (Müller and Krummenacher, 2006) and (Eckstein, 2011).

3. ^For an overview of the concept of information structure and utterances as informational units, see (Halliday, 1967).

References

Arapakis, I., and Leiva, L. A. (2016). “Predicting user engagement with direct displays using mouse cursor information,” in Proceedings of the 39th International ACM SIGIR conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, 599–608. doi: 10.1145/2911451.2911505

Arapakis, I., and Leiva, L. A. (2020). “Learning efficient representations of mouse movements to predict user attention,” in Proceedings of the 43rd International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, 1309–1318. doi: 10.1145/3397271.3401031

Arapakis, I., Penta, A., Joho, H., and Leiva, L. A. (2020). A price-per-attention auction scheme using mouse cursor information. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. 38, 1–30. doi: 10.1145/3374210

Arroyo, E., Selker, T., and Wei, W. (2006). “Usability tool for analysis of web designs using mouse tracks,” in CHI'06 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 484–489. doi: 10.1145/1125451.1125557

Ashdown, M., Oka, K., and Sato, Y. (2005). “Combining head tracking and mouse input for a gui on multiple monitors,” in CHI'05 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1188–1191. doi: 10.1145/1056808.1056873

Ashktorab, Z., Jain, M., Liao, Q. V., and Weisz, J. D. (2019). “Resilient chatbots: repair strategy preferences for conversational breakdowns,” in Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–12. doi: 10.1145/3290605.3300484

Axelsson, N., and Skantze, G. (2020). “Using knowledge graphs and behaviour trees for feedback-aware presentation agents,” in Proceedings of the 20th ACM International Conference on Intelligent Virtual Agents, 1–8. doi: 10.1145/3383652.3423884

Bartneck, C., Croft, E., and Kulic, D. (2008). “Measuring the anthropomorphism, animacy, likeability, perceived intelligence and perceived safety of robots,” in Metrics for HRI Workshop, Technical Report, 37–44.

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B., and Walker, S. (2014). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. arXiv preprint arXiv:1406.5823.

Baumann, T., Paetzel, M., Schlesinger, P., and Menzel, W. (2013). “Using Affordances to shape the interaction in a hybrid spoken dialogue system,” in Studientexte zur Sprachkommunikation: Elektronische Sprachsignalverarbeitung 2013 (Dresden: TUD Press), 1219. Available online at: https://www.essv.de/pdf/2013_12_19.pdf

Baumann, T., and Schlangen, D. (2012). “Inpro_iss: a component for just-in-time incremental speech synthesis,” in Proceedings of the ACL 2012 System Demonstrations, 103–108.

Behnke, G., Bercher, P., Kraus, M., Schiller, M., Mickeleit, K., Häge, T., et al. (2020). “New developments for robert-assisting novice users even better in diy projects,” in Proceedings of the International Conference on Automated Planning and Scheduling, 343–347. doi: 10.1609/icaps.v30i1.6679

Bell, A. (1984). Language style as audience design. Lang. Soc. 13, 145–204. doi: 10.1017/S004740450001037X

Bohus, D., and Horvitz, E. (2009). “Open-world dialog: challenges, directions, and prototype,” in 6th IJCAI Workshop on Knowledge and Reasoning in Practical Dialogue Systems, 34.

Branigan, H. P., Pickering, M. J., Pearson, J., and McLean, J. F. (2010). Linguistic alignment between people and computers. J. Pragmat. 42, 2355–2368. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.2009.12.012

Brennan, S. E., and Clark, H. H. (1996). Conceptual pacts and lexical choice in conversation. J. Exper. Psychol. 22:1482. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.22.6.1482

Brennan, S. E., and Hanna, J. E. (2009). Partner-specific adaptation in dialog. Top. Cogn. Sci. 1, 274–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-8765.2009.01019.x

Brennan, S. E., and Schober, M. F. (2001). How listeners compensate for disfluencies in spontaneous speech. J. Mem. Lang. 44, 274–296. doi: 10.1006/jmla.2000.2753

Brückner, L., Arapakis, I., and Leiva, L. A. (2021). “When choice happens: a systematic examination of mouse movement length for decision making in web search,” in Proceedings of the 44th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, 2318–2322. doi: 10.1145/3404835.3463055

Buschmeier, H., Baumann, T., Dosch, B., Kopp, S., and Schlangen, D. (2012). “Combining incremental language generation and incremental speech synthesis for adaptive information presentation,” in Proceedings of the 13th Annual Meeting of the Special Interest Group on Discourse and Dialogue, 295–303.

Calcagní, A., Lombardi, L., and Sulpizio, S. (2017). Analyzing spatial data from mouse tracker methodology: an entropic approach. Behav. Res. Methods 49, 2012–2030. doi: 10.3758/s13428-016-0839-5

Chai, J. Y., She, L., Fang, R., Ottarson, S., Littley, C., Liu, C., et al. (2014). “Collaborative effort towards common ground in situated human-robot dialogue,” in 2014 9th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (HRI) (IEEE), 33–40. doi: 10.1145/2559636.2559677

Chen, M. C., Anderson, J. R., and Sohn, M. H. (2001). “What can a mouse cursor tell us more? Correlation of eye/mouse movements on web browsing,” in CHI'01 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 281–282. doi: 10.1145/634067.634234

Clark, H. H. (1996). Using Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511620539

Clark, H. H., and Brennan, S. E. (1991). “Grounding in communication,” in Perspectives on socially shared cognition, eds. L. B. Resnick, J. M. Levine, and S. D. Teasley (New York: American Psychological Association), 127–149. doi: 10.1037/10096-006

Clark, H. H., and Krych, M. A. (2004). Speaking while monitoring addressees for understanding. J. Mem. Lang. 50, 62–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jml.2003.08.004

Clark, H. H., and Marshall, C. R. (1981). “Definite knowledge and mutual knowledge,” in Elements of Discourse Understanding, eds. A. K. Joshi, B. L. Webber, and I. A. Sag (Cambridge University Press), 10–63.

Clark, H. H., and Wilkes-Gibbs, D. (1986). Referring as a collaborative process. Cognition 22, 1–39. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(86)90010-7

Clark, L., Pantidi, N., Cooney, O., Doyle, P., Garaialde, D., Edwards, J., et al. (2019). “What makes a good conversation? Challenges in designing truly conversational agents,” in Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–12. doi: 10.1145/3290605.3300705

Dafoe, A., Bachrach, Y., Hadfield, G., Horvitz, E., Larson, K., and Graepel, T. (2021). Cooperative ai: machines must learn to find common ground. Nature 593, 33–36. doi: 10.1038/d41586-021-01170-0

Dale, R., and Reiter, E. (1995). Computational interpretations of the gricean maxims in the generation of referring expressions. Cogn. Sci. 19, 233–263. doi: 10.1207/s15516709cog1902_3

Dethlefs, N., Cuayáhuitl, H., and Viethen, J. (2011). “Optimising natural language generation decision making for situated dialogue,” in Proceedings of the SIGDIAL 2011 Conference, 78–87.

DeVault, D. (2008). Contribution Tracking: Participating in Task-Oriented Dialogue Under Uncertainty. New Jersey: Rutgers The State University of New Jersey-New Brunswick.

DeVault, D., Rutgers, N. K., Kothari, A., Oved, I., and Stone, M. (2005). “An information-state approach to collaborative reference,” in Proceedings of the ACL Interactive Poster and Demonstration Sessions, 1–4. doi: 10.3115/1225753.1225754

Diaz, F., White, R., Buscher, G., and Liebling, D. (2013). “Robust models of mouse movement on dynamic web search results pages,” in Proceedings of the 22nd ACM international conference on Information &Knowledge Management, 1451–1460. doi: 10.1145/2505515.2505717

Doğan, F. I., Gillet, S., Carter, E. J., and Leite, I. (2020). The impact of adding perspective-taking to spatial referencing during human-robot interaction. Rob. Auton. Syst. 134:103654. doi: 10.1016/j.robot.2020.103654

Doğan, F. I., and Leite, I. (2021). Open challenges on generating referring expressions for human-robot interaction. arXiv preprint arXiv:2104.09193.

Eerola, T., Armitage, J., Lavan, N., and Knight, S. (2021). Online data collection in auditory perception and cognition research: recruitment, testing, data quality and ethical considerations. Audit. Percept. Cogn. 4, 251–280. doi: 10.1080/25742442.2021.2007718

Ekstedt, E., and Skantze, G. (2020). “Turngpt: a transformer-based language model for predicting turn-taking in spoken dialog,” in Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2020, 2981–2990. doi: 10.18653/v1/2020.findings-emnlp.268

Engonopoulos, N., Villalba, M., Titov, I., and Koller, A. (2013). “Predicting the resolution of referring expressions from user behavior,” in Proceedings of the 2013 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 1354–1359. doi: 10.18653/v1/D13-1134

Fang, R., Doering, M., and Chai, J. Y. (2015). “Embodied collaborative referring expression generation in situated human-robot interaction,” in Proceedings of the Tenth Annual ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, 271–278. doi: 10.1145/2696454.2696467

Fernández, R., Schlangen, D., and Lucht, T. (2007). “Push-to-talk ain't always bad! Comparing different interactivity settings in task-oriented dialogue,” in Proceedings of the DECALOG 2007, 25.

Fitts, P. M. (1954). The information capacity of the human motor system in controlling the amplitude of movement. J. Exp. Psychol. 47:381. doi: 10.1037/h0055392

Fussell, S. R., and Krauss, R. M. (1992). Coordination of knowledge in communication: effects of speakers' assumptions about what others know. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 62:378. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.62.3.378

Garoufi, K., and Koller, A. (2014). Generation of effective referring expressions in situated context. Lang. Cogn. Neurosci. 29, 986–1001. doi: 10.1080/01690965.2013.847190

Garoufi, K., Staudte, M., Koller, A., and Crocker, M. W. (2016). Exploiting listener gaze to improve situated communication in dynamic virtual environments. Cogn. Sci. 40, 1671–1703. doi: 10.1111/cogs.12298

Gigliobianco, S., Kontogiorgos, D., and Schlangen, D. (2024). “Learning task-oriented dialogues through various degrees of interactivity,” in Proceedings of the 28th Workshop on the Semantics and Pragmatics of Dialogue.

Gonsior, B., Wollherr, D., and Buss, M. (2010). “Towards a dialog strategy for handling miscommunication in human-robot dialog,” in 19th International Symposium in Robot and Human Interactive Communication (IEEE), 264–269. doi: 10.1109/ROMAN.2010.5598618

Goodman, N. D., and Stuhlmüller, A. (2013). Knowledge and implicature: Modeling language understanding as social cognition. Top. Cogn. Sci. 5, 173–184. doi: 10.1111/tops.12007

Grice, H. P. (1975). “Logic and conversation,” in Speech Acts (Brill), 41–58. doi: 10.1163/9789004368811_003

Guo, Q., and Agichtein, E. (2008). “Exploring mouse movements for inferring query intent,” in Proceedings of the 31st Annual International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, 707–708. doi: 10.1145/1390334.1390462

Guo, Q., and Agichtein, E. (2010). “Towards predicting web searcher gaze position from mouse movements,” in CHI'10 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 3601–3606. doi: 10.1145/1753846.1754025

Haake, K., Schimke, S., Betz, S., and Zarrieß, S. (2019). “Do hesitations facilitate processing of partially defective system utterances? An exploratory eye tracking study,” in Proceedings of Interspeech. doi: 10.21437/Interspeech.2019-2820

Halliday, M. A. (1967). Notes on transitivity and theme in English: Part 2. J. Linguist. 3, 199–244. doi: 10.1017/S0022226700016613

Horvitz, E. (1999). “Principles of mixed-initiative user interfaces,” in Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 159–166. doi: 10.1145/302979.303030

Horwitz, R., Brockhaus, S., Henninger, F., Kieslich, P. J., Schierholz, M., Keusch, F., et al. (2020). “Learning from mouse movements: improving questionnaires and respondents' user experience through passive data collection,” in Advances in Questionnaire Design, Development, Evaluation and Testing, 403–425. doi: 10.1002/9781119263685.ch16

Huang, J., White, R., and Buscher, G. (2012a). “User see, user point: gaze and cursor alignment in web search,” in Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1341–1350. doi: 10.1145/2207676.2208591

Huang, J., White, R. W., Buscher, G., and Wang, K. (2012b). “Improving searcher models using mouse cursor activity,” in Proceedings of the 35th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, 195–204. doi: 10.1145/2348283.2348313

Huang, J., White, R. W., and Dumais, S. (2011). “No clicks, no problem: using cursor movements to understand and improve search,” in Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1225–1234. doi: 10.1145/1978942.1979125

Isaacs, E. A., and Clark, H. H. (1987). References in conversation between experts and novices. J. Exper. Psychol. 116:26. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.116.1.26

Jensen, L. C., Langedijk, R. M., and Fischer, K. (2020). “Understanding the perception of incremental robot response in human-robot interaction,” in 2020 29th IEEE International Conference on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (RO-MAN) (IEEE), 41–47. doi: 10.1109/RO-MAN47096.2020.9223615

Johnson, A., Mulder, B., Sijbinga, A., and Hulsebos, L. (2012). Action as a window to perception: measuring attention with mouse movements. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 26, 802–809. doi: 10.1002/acp.2862

Kelleher, J., and Kruijff, G.-J. M. (2006). “Incremental generation of spatial referring expressions in situated dialog,” in Proceedings of the 21st international conference on computational linguistics and 44th annual meeting of the association for computational linguistics, 1041–1048. doi: 10.3115/1220175.1220306

Kennington, C., and Schlangen, D. (2017). A simple generative model of incremental reference resolution for situated dialogue. Comput. Speech Lang. 41, 43–67. doi: 10.1016/j.csl.2016.04.002

Kieslich, P. J., Henninger, F., Wulff, D. U., Haslbeck, J. M., and Schulte-Mecklenbeck, M. (2019). “Mouse-tracking: a practical guide to implementation and analysis 1,” in A Handbook of Process Tracing Methods (Routledge), 111–130. doi: 10.4324/9781315160559-9

Kirk, D. S., and Fraser, D. S. (2017). “The effects of remote gesturing on distance instruction,” in Computer Supported Collaborative Learning 2005: The Next 10 Years! (Routledge), 301–310. doi: 10.3115/1149293.1149332

Kirsh, I. (2020). “Using mouse movement heatmaps to visualize user attention to words,” in Proceedings of the 11th Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction: Shaping Experiences, Shaping Society, 1–5. doi: 10.1145/3419249.3421250

Koller, A., Garoufi, K., Staudte, M., and Crocker, M. (2012). “Enhancing referential success by tracking hearer gaze,” in Proceedings of the 13th Annual Meeting of the Special Interest Group on Discourse and Dialogue, 30–39.

Kontogiorgos, D. (2022). Mutual understanding in situated interactions with conversational user interfaces: theory, studies, and computation. PhD thesis, KTH Royal Institute of Technology. doi: 10.31237/osf.io/fpts4

Kontogiorgos, D., and Gustafson, J. (2021). Measuring collaboration load with pupillary responses-implications for the design of instructions in task-oriented HRI. Front. Psychol. 12:623657. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.623657

Kontogiorgos, D., and Pelikan, H. R. (2020). “Towards adaptive and least-collaborative-effort social robots,” in Companion of the 2020 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, 311–313. doi: 10.1145/3371382.3378249

Kontogiorgos, D., Pereira, A., and Gustafson, J. (2019). “Estimating uncertainty in task-oriented dialogue,” in 2019 International Conference on Multimodal Interaction, 414–418. doi: 10.1145/3340555.3353722

Kousidis, S., Kennington, C., Baumann, T., Buschmeier, H., Kopp, S., and Schlangen, D. (2014). “Situationally aware in-car information presentation using incremental speech generation: safer, and more effective,” in Proceedings of the EACL 2014 Workshop on Dialogue in Motion, 68–72. doi: 10.3115/v1/W14-0212

Krahmer, E., and Van Deemter, K. (2012). Computational generation of referring expressions: a survey. Comput. Linguist. 38, 173–218. doi: 10.1162/COLI_a_00088

Krassanakis, V., and Kesidis, A. L. (2020). Matmouse: a mouse movements tracking and analysis toolbox for visual search experiments. Multimodal Technol. Inter. 4:83. doi: 10.3390/mti4040083

Kraut, R. E., Fussell, S. R., and Siegel, J. (2003). Visual information as a conversational resource in collaborative physical tasks. Hum. Comput. Inter. 18, 13–49. doi: 10.1207/S15327051HCI1812_2

Li, L., Zhao, Y., Zhang, Z., Niu, T., Feng, F., and Wang, X. (2020). “Referring expression generation via visual dialogue,” in CCF International Conference on Natural Language Processing and Chinese Computing (Springer), 28–40. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-60457-8_3

Lindwall, O., and Ekström, A. (2012). Instruction-in-interaction: the teaching and learning of a manual skill. Hum. Stud. 35, 27–49. doi: 10.1007/s10746-012-9213-5

Liu, M. X., Sarkar, A., Negreanu, C., Zorn, B., Williams, J., Toronto, N., et al. (2023). “what it wants me to say”: Bridging the abstraction gap between end-user programmers and code-generating large language models,” in Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–31. doi: 10.1145/3544548.3580817

Magassouba, A., Sugiura, K., and Kawai, H. (2018). A multimodal classifier generative adversarial network for carry and place tasks from ambiguous language instructions. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 3, 3113–3120. doi: 10.1109/LRA.2018.2849607

Mitev, N., Renner, P., Pfeiffer, T., and Staudte, M. (2018). “Using listener gaze to refer in installments benefits understanding,” in CogSci.

Monaro, M., Gamberini, L., and Sartori, G. (2017). The detection of faked identity using unexpected questions and mouse dynamics. PLoS ONE 12:e0177851. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177851

Morawiec, D. (2021). sklearn-porter. Transpile trained scikit-learn estimators to C, Java, JavaScript and others. https://github.com/nok/sklearn-porter

Mueller, F., and Lockerd, A. (2001). “Cheese: tracking mouse movement activity on websites, a tool for user modeling,” in CHI'01 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 279–280. doi: 10.1145/634067.634233

Müller, H. J., and Krummenacher, J. (2006). Visual search and selective attention. Vis. Cogn. 14, 389–410. doi: 10.1080/13506280500527676

Pedregosa, F., Varoquaux, G., Gramfort, A., Michel, V., Thirion, B., Grisel, O., et al. (2011). Scikit-learn: machine learning in python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12, 2825–2830. doi: 10.5555/1953048.2078195

Pelikan, H. R., and Broth, M. (2016). “Why that NAO? How humans adapt to a conventional humanoid robot in taking turns-at-talk,” in Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 4921–4932. doi: 10.1145/2858036.2858478

Qvarfordt, P. (2017). “Gaze-informed multimodal interaction,” in The Handbook of Multimodal-Multisensor Interfaces: Foundations, User Modeling, and Common Modality Combinations, 365–402. doi: 10.1145/3015783.3015794

Reigeluth, C. M., Merrill, M. D., Wilson, B. G., and Spiller, R. T. (1980). The elaboration theory of instruction: a model for sequencing and synthesizing instruction. Instruct. Sci. 9, 195–219. doi: 10.1007/BF00177327