- 1Riga Technical University, Riga, Latvia

- 2Universitat Politècnica de València, Valencia, Spain

Since its emergence in 2009, DevOps has significantly advanced software development. Numerous studies have explored the evolution of DevOps and its related methodologies. Some of this research has investigated how model-driven engineering (MDE) can enhance the adoption and implementation of CI/CD practices, commonly known as DevOps pipelines. MDE, originating in the 1980s, offers a distinct approach to software development compared to the traditional “code is the model” mindset. This paper examines the potential synergies between MDE and DevOps, specifically reviewing existing studies on the key artifacts of DevOps pipelines. Our findings indicate that current efforts have not yet sufficiently generalized or formalized reusable transformation rules for a DevOps pipeline model and its corresponding meta-model. These elements are crucial for a successful MDE approach. Therefore, this study proposes an application of the model transformation concept to the DevOps pipeline model. Furthermore, it conceptualizes a reusable model transformation solution capable of generating both the DevOps pipeline model and its resulting code from a software architecture model. The broad research presented here identifies requirements for a potentially groundbreaking future DevOps solution.

1 Introduction

The rapid evolution of DevOps practices has significantly advanced software development, particularly through the automation of Continuous Integration and Delivery (CI/CD). Among the various approaches explored to enhance these practices, model-driven engineering (MDE) offers a promising pathway to formalize and automate DevOps pipeline generation. MDE, with its roots in the formalization of software design using the Unified Modeling Language (UML) since the late 1980s, emphasizes abstraction, visualization, and automated code generation to reduce errors and accelerate development.

Some of this research has investigated how model-driven engineering (MDE) can enhance the adoption and implementation of CI/CD practices, commonly known as DevOps pipelines. This paper examines the potential synergies between MDE and DevOps, specifically reviewing existing studies on the key artifacts of DevOps pipelines. Our findings indicate that current efforts have not yet sufficiently generalized or formalized reusable transformation rules for a DevOps pipeline model and its corresponding meta-model. Model-driven engineering (MDE) (Brambilla et al., 2017) roots lie in efforts to formalize software design with Unified Modeling Language (UML) (The Object Management Group, 2017) in the late 1980s (Nikiforova et al., 2009) via visualization of the problem domain and respective product as software system. Although model-driven concepts were not explicitly identified in our surveyed studies, DevOps pipeline development largely remains a manual, repetitive, and costly exercise in many projects. The research (Karlovs-Karlovskis and Ņikiforova, 2024), covering 15 years since DevOps inception, aims to identify models and meta-models employed for advanced pipeline generation from domain models at different levels of abstraction, assesses the integration of model transformation within DevOps solutions, and investigates the input and output models used to perform these transformations. In summary, the DevOps toolchain and pipeline (GitLab Inc., 2024) are well-established formalisms in IT product development (Süß et al., 2022) but current MDE tooling is not designed at its core to participate in them. Building on these foundational concepts, this paper explores the conceptual application of model transformations for generating DevOps pipelines.

This study proposes an application of the model transformation concept to the DevOps pipeline model. Furthermore, it conceptualizes a reusable model transformation solution capable of generating both the DevOps pipeline model and its resulting code. Our findings indicate that current efforts have not yet sufficiently generalized or formalized reusable transformation rules for a DevOps pipeline model and its corresponding meta-model. The underlying research question is: Is it possible to use model transformation (MT) for DevOps pipeline development to make it faster, more precise, and reusable?

The aim of the research presented in the paper is to propose and conceptualize a model transformation framework for DevOps pipelines. In order to achieve the goal, this study applies a systematic literature review (SLR) that combines the PRISMA (Page et al., 2021) guidelines with the Kitchenham guidelines (Kitchenham and Brereton, 2013), ensuring both transparency and rigor. Building on the insights from the SLR, the research employs conceptual modeling to define DevOps pipeline artifacts, models, and transformation rules. Finally, a proof-of-concept use case demonstrates the transformation of a UML class model within a Java ecosystem into a GitLab CI/CD DevOps pipeline.

As far as this study aims to produce a conceptual framework for applying model transformations in DevOps pipeline generation, it defines the input–output model mapping and reusable transformation rules necessary for automating pipeline creation. In addition to demonstrating a proof-of-concept use case, the proposed framework’s feasibility and applicability are highlighted, showcasing its potential to accelerate, standardize, and improve DevOps pipeline development.

Because this work focuses on defining the conceptual structure and the transformation logic at the meta-model and process level, detailed implementation artifacts and complete technical rule sets are intentionally abstracted from the current scope to maintain clarity and emphasize the conceptual contribution.

The paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews the evolution of DevOps and pipeline development, pipeline modeling approaches, model-driven engineering in DevOps, and challenges such as a lack of formalization and tool dependencies. Section 3 presents the essence of pipeline development, including lifecycles, tools, and primary artifacts. Section 4 examines software architecture models as inputs for pipeline generation. Section 5 introduces the conceptual framework for model transformations into pipelines, including input–output mapping and transformation rules. Section 6 demonstrates a proof-of-concept use case transforming a UML class model into a GitLab CI/CD DevOps pipeline. Section 7 discusses advantages, comparisons with related approaches, and challenges, while Section 8 concludes with main contributions, practical implications, and future research directions.

2 Related work and background

The problem domain central to this article resides at the intersection of DevOps pipeline automation and Model-Driven Engineering (MDE), focusing on the challenge of formalizing and automating pipeline creation. While DevOps practices have matured, the development of the pipelines themselves remains costly in many projects. This section establishes the necessary background and contextualizes this research within the existing body of knowledge. It is divided into two primary subsections. Section 2.1 provides a brief excursion into the evolution of DevOps and summarizes the results of a prior Systematic Literature Review (SLR) conducted by the authors. Section 2.2 synthesizes the core challenges discussed in the related literature and outlines the motivation for the conceptualization presented in this study. These challenges, including the lack of a formal pipeline engineering definition, an infrastructure-centric focus in research, and limited generalization of transformation rules, drive the necessity and essence of the conceptualization undertaken within the framework of this study.

2.1 DevOps and pipeline development

The origins of DevOps can be traced back to 2009 and the visionary Belgian, Patrick Debois, the founder of the DevOpsDays conference and movement (Devopsdays, 2025). Prior to Debois’s pivotal role, Andrew Schafer, another influential figure, had been advocating for the concept of “Agile Infrastructure” for a few years. Their discussions on this topic at the Agile conference in 2008 were significant in shaping the early stages of DevOps.

At the O’Reilly Velocity Conference, John Allspaw and Paul Hammond presented their groundbreaking case study at Flickr, demonstrating their ability to deploy to production more than ten times daily. Patrick Debois was among the online audience closely following their presentation. Inspired by these stories and his own experiences, Debois founded the DevOpsDays conference in Ghent, Belgium (Techstrong Group I, 2018), but since the name “DevOpsDays” seemed too long for a hashtag to use on Twitter, a shortened version #DevOps emerged (New Relic, 2014). Since then, the DevOps movement has rapidly gained acceptance among engineers seeking to accelerate software development.

The DevOps has significantly advanced software development. Numerous studies have explored the evolution of DevOps and its related methodologies. One of the practices, the DevOps pipeline (GitHub Inc., 2024), facilitates the development and deployment of software in an automated way. Since its inception in 2009, DevOps has spurred the development of numerous tools and solutions from private industry, open-source communities, and academia. Over the 15 years since the emergence of DevOps, a multitude of continuous practices have gained prominence, each promising to accelerate specific stages of the software development lifecycle. A literature review published in 2017 (Shahin et al., 2017) was conducted to review the state of the art of continuous practices to classify approaches and tools, identify challenges and practices in this regard, and identify the gaps for future research. Of the 69 relevant papers analyzed, 25 delved into the integration of various tools to construct effective toolchains. At the time of this research, the DevOps pipeline was still an emerging concept and consequently underrepresented in the analyzed studies.

Having outlined the findings of the previously published SLR, we now turn to the results of our own survey, conducted to validate and extend these observations. The authors performed the systematic literature review in accordance with the PRISMA 2020 (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines (Page et al., 2021). The complete methodological details, including full search strings, the complete database list, screening stages, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and the quality assessment checklist, are documented extensively in the referenced review. For the literature review, the Systematic Literature Review method (Kitchenham and Brereton, 2013) was applied. Although both PRISMA and Kitchenham guidelines support rigorous systematic literature reviews, each offers distinct advantages: PRISMA emphasizes transparency, replicability, and completeness, while Kitchenham’s guidelines are tailored to empirical software engineering. Therefore, a hybrid approach was chosen to combine PRISMA’s transparency with Kitchenham’s domain-specific rigor, ensuring a methodologically sound review that meets expectations from both medical-style and software engineering SLR practices. In the present article, we summarize only the conceptual findings to avoid unnecessary duplication, and readers seeking full reproducibility materials are referred to the original SLR publication. To thoroughly identify relevant work potentially overlooked by previous reviews, the authors conducted a dedicated literature review focusing on model transformations for the advanced generation of pipelines within DevOps solutions, spanning 15 years since DevOps’ inception in 2009. The paper selection strategy was based on several criteria, including the presence of words such as “model driven,” “devops,” “build,” or “deployment” in the title, abstract, or keywords. This resulted in 386 studies retrieved, with a final pool of 42 studies selected for in-depth full-text analysis. To ensure rigor, each of the 42 papers was assessed using a predefined quality checklist adapted from Kitchenham and Brereton, and after the full analysis and selection process, nine studies were deemed eligible to address the research questions.

The in-depth full-text analysis of the relevant studies demonstrates promising results of pipeline generation from model transformation, which proves the hypothesis as conceptually possible. The non-growing trend of studies, particularly in model transformations for pipeline automation, could be explained by the growing popularity of researching the artificial intelligence field since 2020 (Karlovs-Karlovskis, 2024). Two primary trends are observed:

1. Infrastructure-focused: Studies have proposed the use of MDE approaches for pipeline generation, often resulting in the orchestration of infrastructure components, such as cloud resources or Docker containers. The objective of such research is to investigate the orchestration of the component configuration process using an MDE approach as an alternative to the current practice of costly manual scripting and configuration by engineers.

2. Organization-wide: Several studies use a wide spectrum of input data to encompass various aspects of an organization, often extending beyond the scope of software development. Many of these studies are theoretical in nature and have not been empirically validated in a field experiment.

The reviewed studies demonstrate a strong potential for integrating model transformation concepts into DevOps pipelines. However, these studies often combine the two paradigms in an imprecise manner, hindering widespread industry adoption. A notable gap in existing research is the absence of a conceptual model that explicitly represents the structure and content of DevOps pipelines. While studies focus on automating pipeline development, they lack a defined, high-level representation of pipeline components and their relationships. The paper remains intentionally high-level, as its aim is to consolidate and formalize the conceptual principles required for model-driven pipeline generation rather than to present a fully operational tooling framework, which would require implementation-specific details beyond the intended scope.

2.2 Model-driven engineering and transformation in the DevOps context

As established in prior work on MDE foundations, UML-based formalization efforts underpin today’s model-driven transformation approaches. The concept of code generation from models sought to reduce manual coding errors and rework, thereby improving software quality and accelerating the development process. Shortly before the inception of DevOps, renewed attention to Model-Driven Architecture (MDA) provided new impetus for these strategies (Pastor and Molina, 2007). Some of this research has investigated how model-driven engineering (MDE) can enhance the adoption and implementation of CI/CD practices, commonly known as DevOps pipelines.

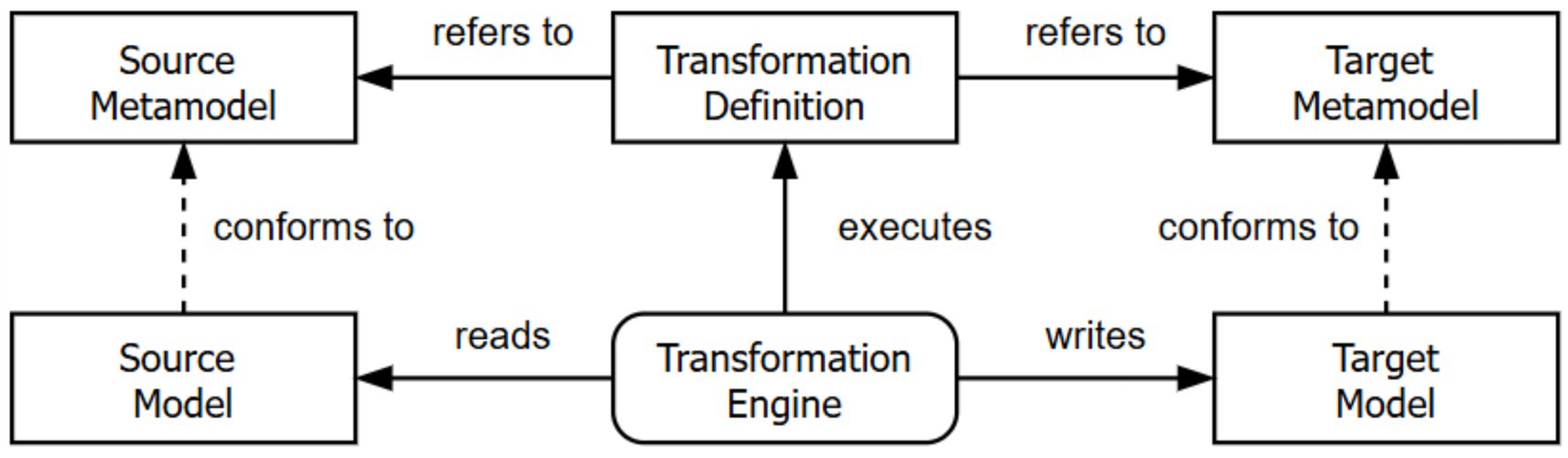

A pivotal moment in this evolution was the first workshop on Model-driven DevOps at the 22nd ACM/IEEE MODELS-C conference in 2019 (Bordeleau et al., 2019). The principles of Model-Driven Engineering (Schmidt, 2006) are applied to the definition of the meta-models and model transformation. By model transformation, the authors refer to a process that accepts one or more source models as input and generates one or more target models as output, adhering to a defined set of transformation rules (Kleppe et al., 2003). A clear mapping between elements of the source meta-model and the target meta-model is required in the transformation definition for the Transformation Engine to work efficiently.

Several studies have explored this intersection, yet they often combine the two paradigms in an imprecise manner, hindering widespread industry adoption. For instance, a standardized TOSCA meta-model can be used for modeling deployment (Wettinger et al., 2016). This research was highly focused on using ready artifacts for deployment and cloud infrastructure provisioning, but does not present a meta-model on Continuous Integration or a pipeline for creating source artifacts.

The project StalkCD (Düllmann et al., 2021) proposes a unique meta-model that is built on top of a Jenkinsfile meta-model. It is a conceptual meta-model that covers all the components of a pipeline; however, the tool and the meta-model are tightly coupled to Jenkins architecture, and the study is limited towards the actual outputs of the pipelines.

A study of the Two-Level Model-Driven Approach (Flores et al., 2024) provides a novel analysis of meta-models for CircleCI, GitHub Actions, and Jenkins to identify commonalities and propose a platform-independent meta-model of DevOps pipeline. The work focuses on text-to-model transformations, so that in the 2nd step, it is possible to generate GitHub Actions pipeline code from the model.

An alternative view (Bartusevics and Novickis, 2015a) is that one meta-model is not feasible, and a model-driven software configuration management solution requires at least two models - the Environment Model and Platform Independent Action Model. El Khalyly et al. (2020) have done a multi-faceted study where they design a Global MetaModel for the overall microservice architecture. This novel approach to microservices deployment is highly focused on the runtime and configuration of existing pre-defined artifacts, but lacks a proposal for a meta-model for an engineering process for them. Due to the high-level abstraction, its items are hard to apply to field problems.

The prototype of the DevOpsML tool (Colantoni et al., 2020) is using SPEM (Object Management Group, 2008) at the backbone and presents a way to model a product lifecycle in combination with technical platforms and project management processes. However, the study lacks practical validation. Similarly, the application of Platform-Independent Model (PIMs) can successfully address configuration (Bartusevics and Novickis, 2015b) and deployment (Rivera et al., 2018) challenges within software development, but the core models are designed for packaged software platforms, which require different configuration management rules than modern microservices-based architectures. Thus, these are applicable for limited use cases.

The study, which presents a tool named Rig (Tegeler et al., 2021) using the TodoMVC modeling software, accomplishes the DevOps pipeline modeling task and can generate the respective code for GitLab CI/CD. Also, relatable studies of 2012 (Steudel et al., n.d.) and 2021 of Rig present insights into a model-driven build server script generation. Many of these studies have no documented continuation or follow-up work, and no explanation is provided for their discontinuation, which may indicate limited adoption or challenges in real-world applicability, although the original studies do not explicitly state the reasons for the lack of continuation.

Based on a comprehensive analysis of the existing literature reviews and the integration of DevOps and model-driven development principles, the authors draw the following findings:

1. Infrastructure-Centric Focus: The majority of related work on applying model transformations in DevOps solutions primarily concentrates on infrastructure management, including cloud, container, and hardware domains. This limited scope is insufficient to address the complexities of orchestrating software build and deployment.

2. Prevalence of System Architecture Models as Input: Among various transformations and use cases, models representing the high-level structure and internal dependencies of system components (referred to as system architecture models) are more frequently utilized. These models demonstrate the potential to contain all necessary information for a DevOps pipeline model.

3. Absence of a Conceptual Pipeline Model: A notable gap in existing research is the absence of a conceptual model that explicitly represents the structure and content of DevOps pipelines. While studies focus on automating pipeline development, they lack a defined, high-level representation of pipeline components and their relationships. This omission is particularly significant for applying model-driven principles.

4. Undefined DevOps Pipeline Engineering: Existing literature reviews indicate that DevOps pipeline engineering lacks a clear definition. Precise definitions are crucial for ensuring predictable and consistent pipeline development. A significant trend identified is the exploration of model transformations as a potential framework for this definition.

2.3 Challenges of pipeline development

The authors identified several key challenges hindering the widespread adoption of continuous practices, including a lack of expertise, reliance on manual configuration, and the dynamic nature of customer environments. The authors further emphasized that overcoming challenges necessitates carefully designed architecture and deployment pipeline engineering as part of the development phase. A notable omission from the analyzed research is the concept of model transformation in continuous practices as a potential solution to the identified challenges.

The majority of related work on applying model transformations in DevOps solutions primarily concentrates on infrastructure management, including cloud, container, and hardware domains. This limited scope is insufficient to address the complexities of orchestrating software build and deployment. These studies provide evidence of optimizing the engineering process, but focus on other artifacts than this study (they do not optimize the DevOps pipeline creation process). The objective of such research is to investigate the orchestration of the component configuration process using an MDE approach as an alternative to the current practice of costly manual scripting and configuration by engineers.

Our findings indicate that current efforts have not yet sufficiently generalized or formalized reusable transformation rules for a DevOps pipeline model and its corresponding meta-model. These elements are crucial for a successful MDE approach. Therefore, this study proposes an application of the model transformation concept to the DevOps pipeline model. Furthermore, it conceptualizes a reusable model transformation solution capable of generating both the DevOps pipeline model and its resulting code. The studies often lack a formal representation of the resulting model itself. Typically, studies yield working tools without providing deeper theoretical insights.

As highlighted earlier, pipeline development remains prone to manual effort. One prominent anti-pattern identified in the research was the inadequate versioning of pipeline code, often attributed to immature tooling and a lack of formalized practices. The study did not identify any anti-patterns specifically related to model transformation for pipelines, suggesting a limited adoption of this approach within the surveyed companies and online communities. While the vision of such research is compelling, achieving tangible results through this approach may be challenging, if not unattainable. Although the continuation of those studies is often non-existent without a particular explanation, this brings us to the conclusion that the developed solutions were not feasible in the fieldwork, where requirements often change rapidly.

3 Essence of pipeline development in DevOps

Since DevOps inception in 2009, DevOps has spurred the development of numerous tools and solutions from private industry, open-source communities, and academia. One of the practices, the DevOps pipeline, facilitates the development and deployment of software in an automated way. The DevOps toolchain and pipeline are well-established formalisms in IT product development (Süß et al., 2022). To further enhance software development speed without compromising quality, this paper argues that DevOps pipeline creation itself necessitates both formalization and appropriate digital solutions.

A DevOps pipeline is a broad term (Süß et al., 2022), therefore this study is focused on a minimal valuable set of steps to deliver a reusable artifact. Such a pipeline can be identified as Continuous Integration (Garci’a-Di’az et al., 2010) pipeline. The goal of such a pipeline is generally to turn source code and some metadata into a reusable software package (Niu et al., 2018), by following a predefined set of stages:

• “pull”—a step that downloads the code to the build environment. This step is often a part of the Continuous Integration tool design, and in some solutions, might not be considered an actual component of Continuous Integration.

• “lint”—steps that validate compliance with coding requirements.

• “compile”—steps that call the code compiler, pass source code files to it, wait for the compiler to finish, and produce binary files.

• “test”—steps for an automated testing process, usually involving only unit tests.

• “package”—steps to collect the compilation results and archive them into a particular package.

• “push”—steps that take the produced package and upload it to a repository for storing and reuse.

Ultimately, Continuous Integration alone is insufficient for a complete software project. Therefore, the solution, along with new transformation rules, will need to be extended to include Continuous Delivery pipeline generation (Bobrovskis and Jurenoks, 2018) as the next stage of DevOps.

A notable achievement of this study is identifying GitLab CI/CD (GitLab Inc., 2025), particularly within a Java ecosystem, as a highly promising technology for which pipeline generation appears feasible. This view is supported by its status as the most popular choice in this domain, according to recent studies. Further in this research, the following use case is used as a practical example. It shows how the most common technologies in DevOps research, GitLab and Java are applied in model transformations for pipelines. The project StalkCD (Düllmann et al., 2021) proposes a unique meta-model that is built on top of a Jenkinsfile meta-model. A study of the Two-Level Model-Driven Approach (Flores et al., 2024) provides a novel analysis of meta-models for CircleCI, GitHub Actions, and Jenkins to identify commonalities and propose a platform-independent meta-model of DevOps pipeline.

As highlighted earlier in the CI anti-patterns study, pipeline development remains prone to manual effort and weak versioning practices. One prominent anti-pattern identified in the research was the inadequate versioning of pipeline code, often attributed to immature tooling and a lack of formalized practices. The authors identified several key challenges hindering the widespread adoption of continuous practices, including a lack of expertise, reliance on manual configuration, and the dynamic nature of customer environments. The core concept behind such technologies involves reusing pipeline code patterns, parametrizing them, overriding their components, and assembling them into new pipelines. While this is a powerful solution that accommodates most common scenarios, any deviation from the product template necessitates the expertise of a seasoned engineer who understands the product’s engineering process context. Instead, we argue that adopting a Model-Driven Engineering (MDE) approach (Nikulsins and Nikiforova, 2008) allows for the design of a system usable by any project member. In most cases, this will eliminate the need for dedicated DevOps pipeline development, as the pipeline will be generated from a software architecture model that serves other primary purposes.

Before designing a conceptual model of a DevOps pipeline, we should have a clear classification of its primary artifacts as conceptual components. Wettinger proposes (Wettinger et al., 2016) an example of pipeline artifacts’ separation into two classes: (1) node-centric artifacts (NCAs) are focused on processes of the build output and its output artifacts; (2) environment-centric artifacts (ECAs) are responsible for storing and managing the information about the environment where build artifacts are being created and later executed. Generally, ECAs (e.g., Amazon CloudFormation template, Docker image) usually orchestrate NCAs (e.g., Gradle script, dependency manifest). To increase the ontological support of the pipeline taxonomy, we add a requirement that NCAs are immutable objects (it’s not allowed to change them after the creation). For a complete collection of Continuous Integration pipeline artifacts, we continue with adding two more classes for primary artifacts (configuration item types) to the initial classification -- Configuration Values (CVs) which have a dynamic nature and generally consist of key-value pairs; and Pipeline-Centric Artifacts (PCAs) to separate artifacts that are dedicated for the supporting engineering automation process, usually known as a CI/CD tool. Finally, these artifacts are linked together using steps and stages (Düllmann et al., 2021) which is a similar concept to GitLab’s stages and jobs.

4 Software architecture models as input for pipeline generation

As established in prior literature review, the prototype of the DevOpsML tool (Colantoni et al., 2020) uses SPEM (Object Management Group, 2008) as the backbone and presents a way to model a product lifecycle in combination with technical platforms and project management processes. Following the classification of input data, various corresponding models were mapped to each class. To complete the analysis, the following notations used for visualizing the models are identified: UML Class diagram (The Object Management Group, 2017), SPEM (Colantoni et al., 2020), Orientation models (Stevens, 2020), UML Activity diagram (The Object Management Group, 2017), and UML Deployment diagram (The Object Management Group, 2017). The comprehensive analysis, therefore, indicates that System Architecture domain abstractions, expressed through Software Models and Deployment Models using UML Class and UML Deployment notations respectively, are suitable input artifacts and models for a successful transformation into a DevOps Pipeline model.

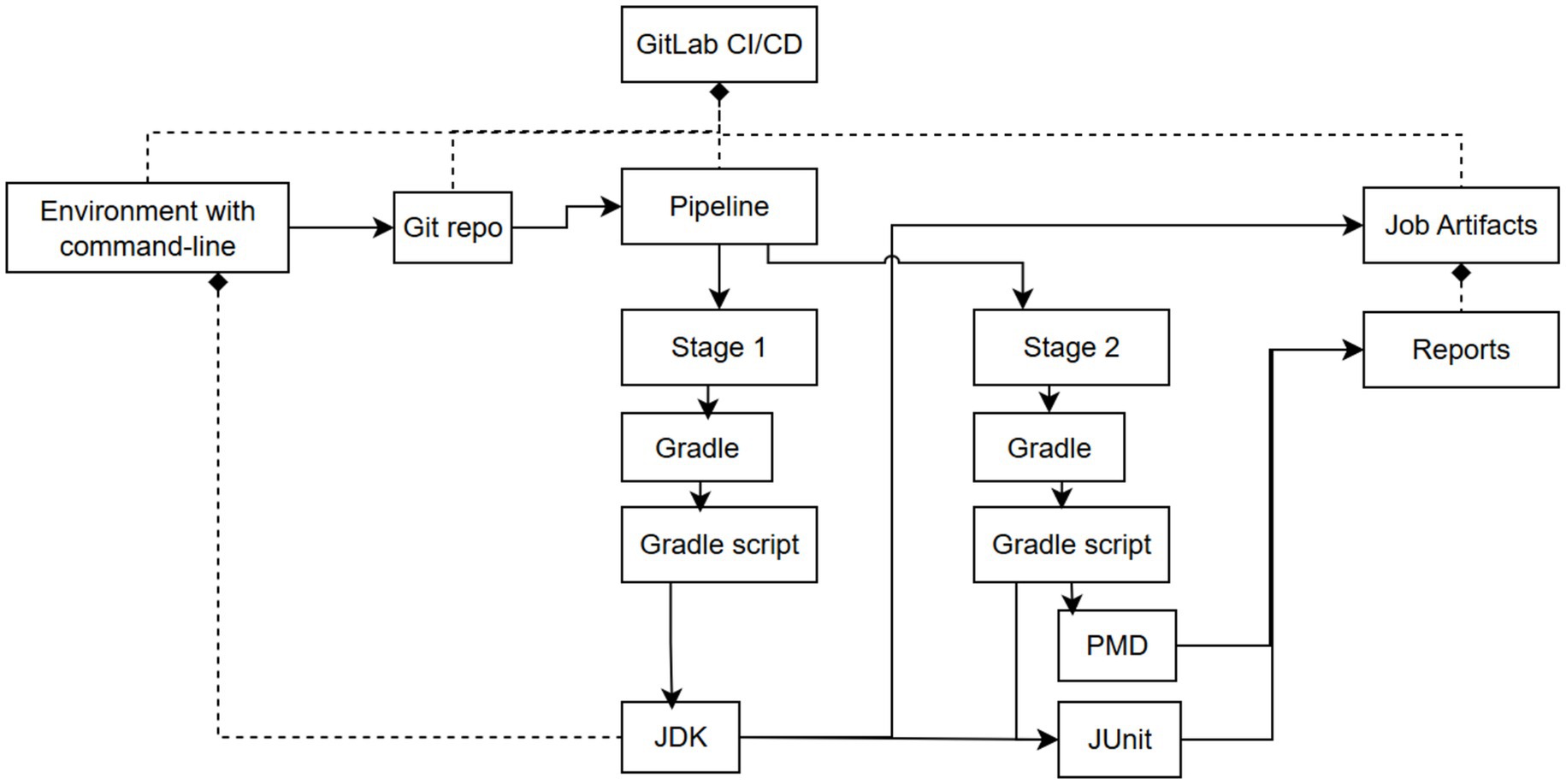

A model transformation engine (see Figure 1) takes a structured source model, applies predefined transformation rules to map elements from the source model to the target model, where both these models conform to the structure presented in their meta-models. To transform a source model into a target model, a set of transformation rules is designed, allowing for the addition of information during the process. Since our goal is to generate DevOps pipeline elements from existing source information, it is expected that all necessary data will already be present in projects where model-driven concepts are applied. A clear mapping between elements of the source meta-model and the target meta-model is required in the transformation definition for the Transformation Engine to work efficiently. If the development team adheres to standardized project structure and naming conventions, these four parameters suffice to generate a Continuous Integration pipeline model using transformation rules. While a more extensive list would be required to cover all scenarios of different project parameters, it is not an exhaustive set of possibilities, and transformation rules for all common scenarios can be developed.

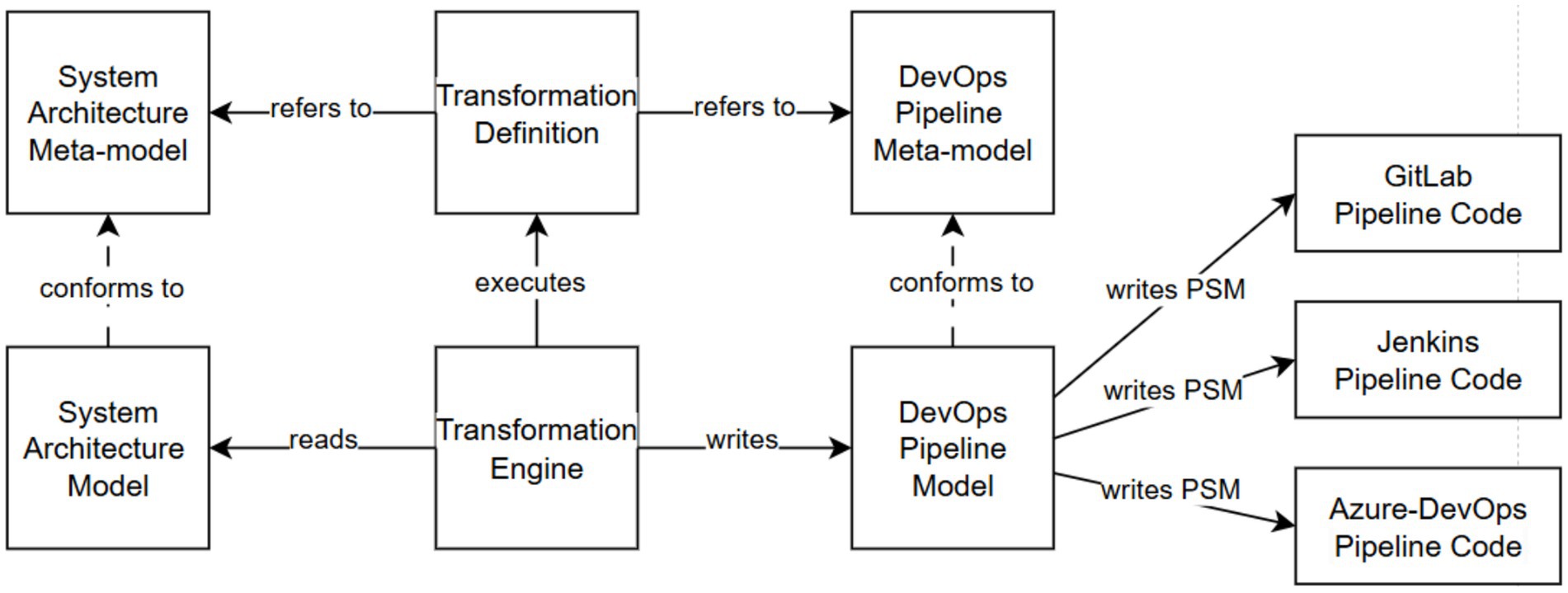

This research demonstrates the conceptual feasibility of transforming system architecture models into a DevOps Pipeline model. The comprehensive analysis, therefore, indicates that System Architecture domain abstractions, expressed through Software Models and Deployment Models using UML Class and UML Deployment notations respectively, are suitable input artifacts and models for a successful transformation into a DevOps Pipeline model. Among various transformations and use cases, models representing the high-level structure and internal dependencies of system components (referred to as system architecture models) are more frequently utilized. These models demonstrate the potential to contain all necessary information for a DevOps pipeline model. The study demonstrated that even with minimal parameters from a software architecture model, such as unit-test configuration, lint check settings, project type, and build system selection, it is possible to generate a functional Continuous Integration pipeline model. The novelty of this work lies in its use of a software architecture model as input, differentiating it from other studies that rely on a dedicated DevOps model. The latter approach often requires additional effort from software engineers, hindering adoption.

5 Conceptual framework for model transformation into pipelines

To frame the findings of the systematic literature review, this chapter describes the structural MDE framework for the generation of DevOps pipelines. Its main principle is to automate the conversion of software architecture models to software pipeline code from framework models, thus fulfilling the gaps of effort, formalization, and missing tools. Each tier of the framework aims to streamline the engineering of DevOps pipelines by formalizing the multi-step processes of constructing rule sets for element cross-reference from a source meta-model of the architecture system to a target DevOps pipeline meta-model. By serving to eliminate, parallel development, and systematize, this approach increases consistency and generates pipeline configurations directly from architectural project definitions. The following sections break down the main parts of the framework: defining the transformation source, constructing the transformation rule sets, defining the transformation target, and the overall transformation cascade.

To address the structural representation of DevOps pipelines more explicitly, we define a lightweight conceptual meta-model that outlines the primary elements required for pipeline generation. This meta-model consists of a Pipeline root element containing an ordered list of Stages, each of which may include one or more Scripts describing executable commands. At an abstract level, the Pipeline element also aggregates configuration-oriented artifacts, representing the essential information required for pipeline construction. This high-level DevOps pipeline meta-model serves as the target structure for model-to-model transformations and provides the necessary conceptual grounding for the framework.

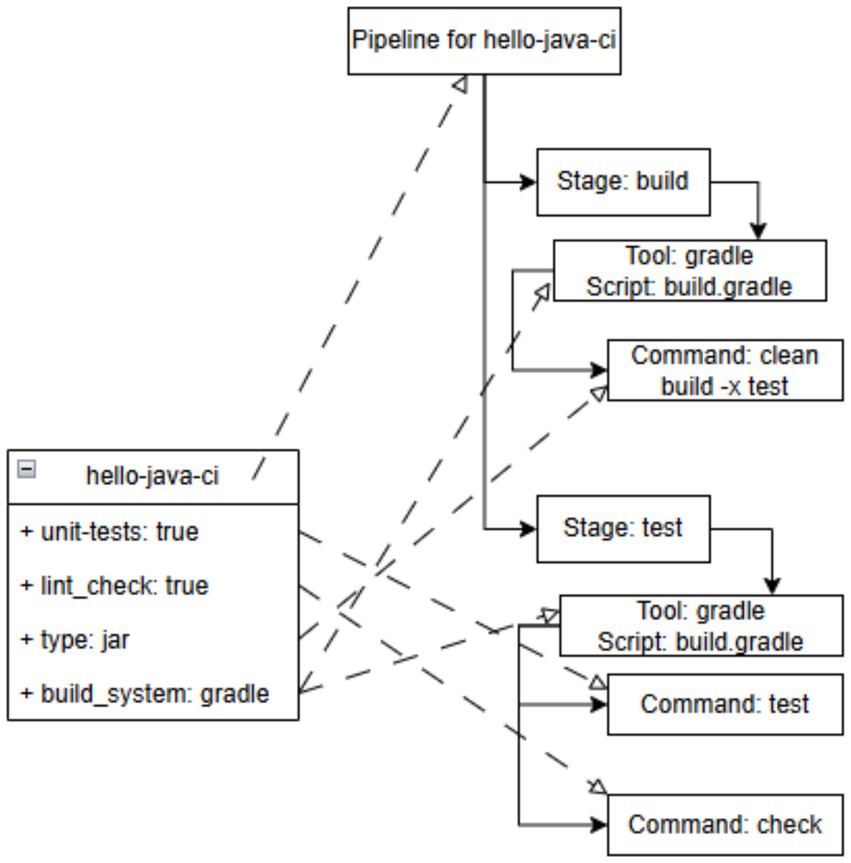

5.1 Transformation source definition

The comprehensive analysis indicates that System Architecture domain abstractions, expressed through Software Models and Deployment Models using UML Class and UML Deployment notations respectively, are suitable input artifacts and models. The concept of code generation from models sought to reduce manual coding errors and rework, thereby improving software quality and accelerating the development process. The principles of Model-Driven Engineering (Schmidt, 2006) are applied to the definition of the meta-models and model transformation. The required software architecture model in UML Class diagram notation is shown on the left side of Figure 2. The application’s name is “hello-java-ci,” which also serves as the name for both the Git repository and the pipeline itself. In this current example, the Java application or library has the following parameters: unit-tests (binary value), lint_check (binary value), type (string value), and build_system (string value).

5.2 The concept of transformation rules within the framework

By model transformation, the authors refer to a process that accepts one or more source models as input and generates one or more target models as output, adhering to a defined set of transformation rules (Kleppe et al., 2003). A clear mapping between elements of the source meta-model and the target meta-model is required in the transformation definition for the Transformation Engine to work efficiently. A model transformation engine takes a structured source model, applies predefined transformation rules to map elements from the source model to the target model, where both these models conform to the structure presented in their meta-models. To transform a source model into a target model, a set of transformation rules is designed, allowing for the addition of information during the process. If the development team adheres to standardized project structure and naming conventions, these four parameters suffice to generate a Continuous Integration pipeline model using transformation rules. While a more extensive list would be required to cover all scenarios of different project parameters, it is not an exhaustive set of possibilities, and transformation rules for all common scenarios can be developed.

All model-to-model transformations in this work are implemented using the Atlas Transformation Language (ATL), which employs a rule-based, declarative paradigm commonly expressed through matched rules and helper functions. The transformation workflow is organized into three distinct phases:

1. From Software Architecture Model to Platform-Independent Model (PIM) Transformation phase transforms a high-level Software Architecture model into a platform-independent Pipeline Model (PIM). The core transformation is governed by a matched rule, a primary pattern-matching rule that triggers transformation when specific source elements are encountered, acting as the entry point. This rule analyzes the input model and determines the necessary pipeline stages. For each identified stage, it invokes a lazy rule, a rule that creates target elements only when explicitly called, enabling reusable transformation logic, which in turn calls upon various helper rules, modular functions that encapsulate specific logic for attribute derivation or value computation, to determine stage-specific attributes and generate corresponding command sequences based on predefined templates.

2. PIM to Platform-Specific Model (PSM) Transformation phase would transform the platform-independent PIM into a Platform-Specific Model (PSM) tailored for a concrete CI/CD platform, in this case, GitLab. Another matched rule in ATL would serve as the primary orchestrator for this phase. It would process the PIM and, for each stage, invoke a lazy rule to generate a corresponding job in the GitLab model. This lazy rule would utilize a different set of helper rules to map the abstract commands and configurations from the PIM into GitLab-specific constructs. This phase effectively translates the abstract workflow into a concrete, executable configuration model for the target platform.

3. Code Generation using Acceleo is the final phase that transforms the GitLab-specific PSM into executable YAML code. This process is driven by template rules that iterate over PSM elements and serialize their properties into proper YAML syntax.

Conceptually, the rules are designed to be modular and reusable. Helper rules in ATL encapsulate specific logical decisions or content generation tasks. Lazy rules are used to create instances of model elements on demand, ensuring the transformation is efficient and organized. Matched rules act as the primary controllers that identify patterns in the source model and trigger the appropriate creation and refinement processes. This layered approach ensures a clear separation of concerns, making the transformation process maintainable and adaptable to new project types or target platforms.

5.3 Transformation target definition

To make the target model more explicit, we clarify that the DevOps pipeline meta-model used in this study is composed of the following core elements:

• a Pipeline class defining the overall pipeline structure and its ordered list of stages;

• Stage elements representing logical execution units within the pipeline;

• Script elements containing ordered command lists associated with each stage.

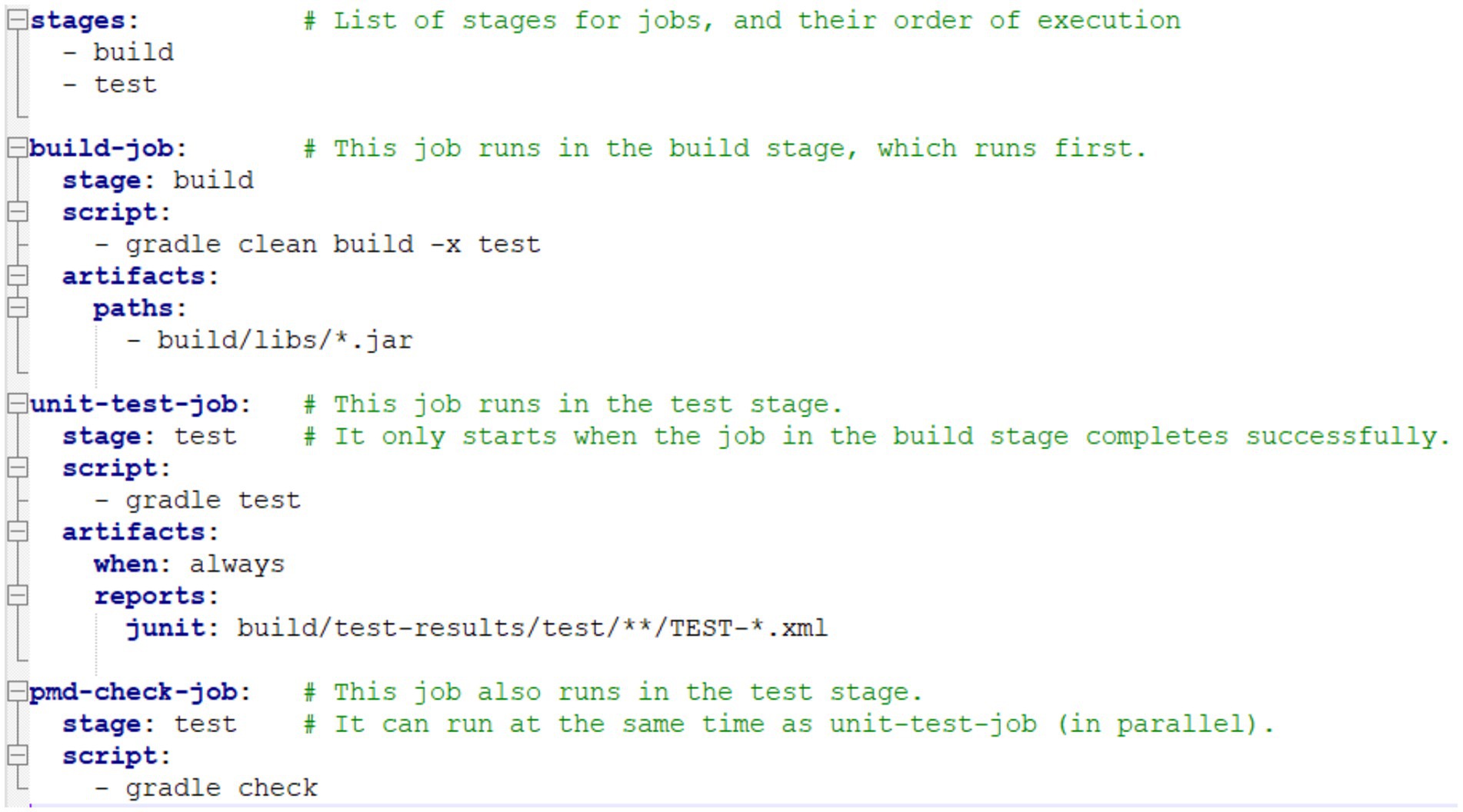

These elements collectively form a minimal but complete representation of a DevOps pipeline are suitable for transformation into platform-specific models. The target model is a model of DevOps pipeline components and their relationships. Furthermore, it conceptualizes a reusable model transformation solution capable of generating both the DevOps pipeline model and its resulting code. This study proposes an application of the model transformation concept to the DevOps pipeline model. The same conceptual model can be expressed as the GitLab pipeline code illustrated in Figure 3. It should be possible to design automated transformation rules for model-to-code transformation, as depicted in Figure 4. While some technical details are omitted for clarity, the figure illustrates how pipeline code is generated from a model, eventually being represented by the GitLab CI/CD tool. This code must be saved as a text file named “.gitlab-ci.yml” at the root of the Git repository next to the codebase of the application for the GitLab CI/CD tool to automatically pick it up.

5.4 Transformation flow

The conceptual schema of model transformation within the essence of model-driven engineering is visualized in Figure 1. Therefore, as illustrated in Figure 5, we propose a conceptual model for transformations from system architecture models into a DevOps pipeline model, which can then be transformed into any platform-specific code. Figure 2 conceptually illustrates how the model-to-model transformation of an atomic Continuous Integration pipeline can be achieved. The conceptual model of the DevOps pipeline has been discussed in the previous section. The model illustrated in Figure 6 specifically depicts an atomic Continuous Integration pipeline to simplify the proof of concept. The conceptual model of the Continuous Integration pipeline, illustrated in Figure 6, builds Java artifacts from source code using GitLab CI/CD orchestrator. While the framework is platform-independent by design, its validation has so far been limited to a single platform-specific example.

6 Proof-of-concept

Further in this research, the following use case is used as a practical example. It shows how the most common technologies in DevOps research, GitLab and Java, are applied in model transformations for pipelines. To transform this example model into an output, the required software architecture model in UML Class diagram notation is shown on the left side of Figure 2. The application’s name is “hello-java-ci,” which also serves as the name for both the Git repository and the pipeline itself. In this current example, the Java application or library has the following parameters: unit-tests (binary value), lint_check (binary value), type (string value), and build_system (string value). If the development team adheres to standardized project structure and naming conventions, these four parameters suffice to generate a Continuous Integration pipeline model using transformation rules. The same conceptual model can be expressed as the GitLab pipeline code illustrated in Figure 3. It consists of two key sections - stages, where the pipeline is documented in sequential order; and jobs, which are mapped to the stages. This code must be saved as a text file named “.gitlab-ci.yml” at the root of the Git repository next to the codebase of the application for the GitLab CI/CD tool to automatically pick it up. As part of this proof-of-concept, the DevOps pipeline meta-model described in Section 5 is used as the structural target for the transformation, ensuring that the generated model conforms to clearly defined pipeline elements.

This research demonstrates the conceptual feasibility of transforming system architecture models into a DevOps pipeline model. The study demonstrated that even with minimal parameters from a software architecture model, such as unit-test configuration, lint check settings, project type, and build system selection, it is possible to generate a functional Continuous Integration pipeline model. The in-depth full-text analysis of the relevant studies demonstrates promising results of pipeline generation from model transformation, which proves the hypothesis as conceptually possible. There are several existing studies (Düllmann et al., 2021) accomplishing similar results with similar technologies. Under the hood, usually, the visual source model is first expressed as XML code, and then, using patterns and placeholders, the target code model gets generated. For modeling and transformation tooling, the Eclipse family is a popular choice.

In this research, we utilized a simple use case involving a single Java program executable from the command line. This example sufficiently conceptualizes the solution. However, for modern Information Systems based on microservice architectures, the example would expand to more sophisticated Continuous Integration pipelines, incorporating additional parameters and process steps. Although the continuation of those studies is often non-existent without a particular explanation, this brings us to the conclusion that the developed solutions were not feasible in the fieldwork, where requirements often change rapidly. While a more extensive list would be required to cover all scenarios of different project parameters, it is not an exhaustive set of possibilities. It is crucial to acknowledge from the outset that for large single-artifact or multi-project systems requiring extensive ongoing pipeline customization, the development of transformation rules might not prove efficient. Instead, the proposed solution is better suited for modern information systems employing microservices architectures, where a similar pipeline code is reused with minor adjustments. This proof-of-concept intentionally remains minimal and focuses on demonstrating conceptual feasibility; applying the approach to microservices systems or additional platforms would require further dedicated research.

7 Discussion

A comparison with existing tools and approaches highlights the distinct contribution of this study. It is important to note that the current proof-of-concept reflects only an atomic Java/GitLab DevOps pipeline and does not yet represent more complex, multi-stage industrial scenarios. The prototype of the DevOpsML tool (Colantoni et al., 2020) is using SPEM at the backbone and presents a way to model a product lifecycle in combination with technical platforms and project management processes. However, both studies lack practical validation. One such solution, which has matured since 2018 and is now widely adopted in the industry, is GitLab’s Auto DevOps (GitLab Inc., 2018).

The existing SLR by authors found no scientific studies to date specifically researching this particular solution. The core concept behind such technologies involves reusing pipeline code patterns, parametrizing them, overriding their components, and assembling them into new pipelines. The project StalkCD (Düllmann et al., 2021) proposes a unique meta-model that is built on top of a Jenkinsfile meta-model; however, the tool and the meta-model are tightly coupled to the Jenkins architecture.

The study, which presents a tool named Rig using the TodoMVC modeling software, accomplishes the DevOps pipeline modeling task and can generate the respective code for GitLab CI/CD. In contrast, the approach proposed in this paper is based on a platform-independent conceptual model that enables transformation from standardized software architecture models (e.g., UML class diagrams) into DevOps pipelines. This supports traceability, reuse, and future extensibility across different DevOps platforms, going beyond the predefined templates or tool-specific solutions offered by current tools.

This study proposes an application of the model transformation concept to the DevOps pipeline model. Furthermore, it conceptualizes a reusable model transformation solution capable of generating both the DevOps pipeline model and its resulting code. The approach proposed in this paper is based on a platform-independent conceptual model. This supports traceability, reuse, and future extensibility across different DevOps platforms. Instead, we argue that adopting a Model-Driven Engineering (MDE) approach (Nikulsins and Nikiforova, 2008) allows for the design of a system usable by any project member. In most cases, this will eliminate the need for dedicated DevOps pipeline development, as the pipeline will be generated from a software architecture model that serves other primary purposes. A significant advantage of the model transformation approach is the potential to seamlessly integrate security aspects and DevSecOps (Akbar and Alsanad, 2025) tooling directly into automatically generated pipelines. By embedding security practices “left-shifted” into the development lifecycle, vulnerabilities can be identified and remediated much earlier, significantly reducing the cost and effort associated with fixing issues later in production.

The study adopts the assessment for rigor and trustworthiness in qualitative research as proposed by Guba and Lincoln (1994).

• Confirmability: Authors have done additional exploratory searches on the internet and scientific knowledge databases to confirm that all the related work has been accounted for.

• Dependability: This research covers 15 years of related work from a variety of scientific knowledge databases to ensure that the concepts do not depend on any particular opinion or technology.

• Transferability: In the early stages of the solution development, it will be usable only by the GitLab CI/CD system in the Java ecosystem to validate its usefulness in the field. However, once the platform-independent meta-models of input and output models are finalized, the proposed concepts are applicable in different environments and tools if the problem domains are similar.

• Novelty: The novelty of this work lies in its use of a software architecture model as input, differentiating it from other studies that rely on a dedicated DevOps model. The latter approach often requires additional effort from software engineers, hindering adoption. However, several critical challenges remain to be addressed in future research. These include the selection of appropriate modeling tools, refinement of software and pipeline meta-models, and integration with existing CI/CD platforms like GitLab.

To foster adoption by engineers of such a tool and approach in general, the solution should support the following non-functional requirements:

• Run anywhere: The modeling and transformation capabilities should be usable and testable on a local workstation and execute on the server side with complete consistency.

• Abstract and encapsulate: Eventually, it should not be another solution on top of the Eclipse framework that the user must download, learn, and execute in addition to the existing development toolbox. The solution should become a part of the Integrated Development Environment toolbox in a Platform-as-a-Service manner, where GitLab CI/CD DevOps pipeline code is on the infrastructure layer and abstracted away.

• Platform independent: While GitLab CI/CD as such is a specific platform implementation, the artifacts it operates with should be platform independent. The build system, including the target platform-specific programming language, potentially can be swapped.

• No new skills required: If the engineer can draw a UML Class diagram of connected components, it should be enough to use the solution. This means that the modeling tool should provide an easy-to-use interface and produce consistent, traceable results.

• Seamless and real-time: there should be no additional steps to export, save, or import some artifacts of models or pipeline code. Once the input model is uploaded to the repository, the solution should take care of the rest and provide pipeline execution results in the response.

8 Conclusions and future work

This paper has presented a conceptual model for a model transformation solution for DevOps pipelines, aiming to accelerate software development processes. Through a comprehensive review of related work, we identified a gap in existing research regarding the formalization of DevOps pipeline generation. While several studies have explored Model-Driven Engineering (MDE) for DevOps, they often focus on infrastructure or lack practical validation. Our findings indicate that current efforts have not yet sufficiently generalized or formalized reusable transformation rules for a DevOps pipeline model and its corresponding meta-model. Therefore, this study proposes an application of the model transformation concept to the DevOps pipeline model. Furthermore, it conceptualizes a reusable model transformation solution capable of generating both the DevOps pipeline model and its resulting code. This intentional abstraction ensures that the contribution of the paper remains focused on the conceptual transformation model and its meta-model foundations, rather than on exhaustive technical implementation details that would be more appropriate for future applied research.

Our research addressed this gap by proposing a conceptual model that leverages model transformation to generate DevOps pipelines from system architecture models, with a specific focus on Continuous Integration pipelines. The main contributions include: a classification of primary pipeline artifacts into Node-Centric Artifacts (NCAs), Environment-Centric Artifacts (ECAs), Pipeline-Centric Artifacts (PCAs), and Configuration Values (CVs); a conceptual model for transformations from system architecture models into a DevOps pipeline model; and a proof-of-concept demonstrating the transformation from a UML class model of a Java project into a GitLab CI/CD DevOps pipeline. The study demonstrated that even with minimal parameters from a software architecture model, such as unit-test configuration, lint check settings, project type, and build system selection, it is possible to generate a functional Continuous Integration pipeline model.

This approach is particularly useful for microservices architectures, where multiple similar pipelines require frequent updates and maintenance. The proposed solution could significantly reduce the manual effort required for pipeline creation and maintenance, especially in scenarios where architectural changes affect multiple service components simultaneously. In most cases, this will eliminate the need for dedicated DevOps pipeline development, as the pipeline will be generated from a software architecture model that serves other primary purposes. Experts will only be required to make infrequent changes to component standards. A significant advantage of the model transformation approach is the potential to seamlessly integrate security aspects and DevSecOps tooling directly into automatically generated pipelines, ensuring that security is not an afterthought but an intrinsic part of the Continuous Delivery process.

The study’s proof-of-concept is limited to a single Java/GitLab DevOps pipeline and does not yet cover heterogeneous architectural settings, microservice architectures, or alternate CI/CD platforms. More sophisticated examples would require additional empirical development and expanded transformation rules, which fall outside the scope of this conceptual paper. As such, the results demonstrate feasibility but do not claim completeness or generalizability across all DevOps ecosystems.

Future work will focus on empirical validation of the proposed conceptual model and transformation approach. In particular, case studies and practitioner feedback will be used to assess the practicality, accuracy, and maintainability of generated DevOps pipelines in real-world projects. This validation phase may include structured surveys, expert interviews, or experimental deployment in pilot environments. In addition, further research will explore integration with existing modeling and CI/CD tools, the development of transformation rule repositories, and the application of the solution to other ecosystems beyond Java and GitLab.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

UK-K: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. OŅ: Writing – review & editing. OP: Writing – review & editing. AJ: Writing – review & editing. KV: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research leading to these results has been supported by the EU Recovery and Resilience Facility within the Project No. 5.2.1.1.i.0/2/24/I/CFLA/003 “Implementation of consolidation and management changes at Riga Technical University, Liepaja University, Rezekne Academy of Technology, Latvian Maritime Academy and Liepaja Maritime College for the progress towards excellence in higher education, science and innovation” academic career PhD grant (ID 1017).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Akbar, M. A., and Alsanad, A. A. (2025). Empirical investigation of key enablers for secure DevOps practices. IEEE Access. 13, 43698–43715. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2025.3549183

Bartusevics, A., and Novickis, L. (2015a). Model-based approach for implementation of software configuration management process., in MODELSWARD 2015 - 3rd International Conference on Model-Driven Engineering and Software Development, Proceedings, 177–184.

Bartusevics, A., and Novickis, L. (2015b). Towards the Model-driven Software Configuration Management Process [Modeļu vadāmais programmatūras konfigurācijas pārvaldības process/ Процесс управления конфигурациями программного обеспечения, основанный на моделях]. Inform. Technol. Manag. Sci. 17:4. doi: 10.1515/itms-2014-0004,

Bobrovskis, S., and Jurenoks, A. (2018). A survey of continuous integration, Continuous delivery and Continuos deployment, in BIR workshops, (Stockholm, Sweden). Available online at: https://ceur-ws.org/Vol-2218/ (Accessed December 26, 2024).

Bordeleau, F., Bruel, J.-M., Cabot, J., Dingel, J., and Mosser, S. (2019). Preface to the 1st workshop on DevOps@MODELS., in 2019 ACM/IEEE 22nd International Conference on Model Driven Engineering Languages and Systems Companion (MODELS-C), 587–588.

Brambilla, M., Cabot, J., and Wimmer, M. (2017). Model-driven software engineering in practice. 2nd Edn. Cham: Springer.

Colantoni, A., Berardinelli, L., and Wimmer, M. (2020). DevOpsML: Towards modeling DevOps processes and platforms., in proceedings of the 23rd ACM/IEEE international conference on model driven engineering languages and systems: Companion proceedings. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery.

Devopsdays (2025). About Devopsdays. Available online at: https://devopsdays.org/about/ (Accessed January 2, 2025).

Düllmann, T. F., Kabierschke, O., and Hoorn, A.van (2021). StalkCD: a model-driven framework for interoperability and analysis of CI/CD pipelines., in 2021 47th Euromicro Conference on Software Engineering and Advanced Applications (SEAA), 214–223.

El Khalyly, B., Belangour, A., Erraissi, A., and Banane, M. (2020). Meta-model approach of applied devops on internet of things ecosystem. 2020 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Electronics, Control, Optimization and Computer Science, ICECOCS 2020.

Flores, A., da Gião, H., Amaral, V., and Cunha, J. (2024). A Two-Level Model-Driven Approach for Reengineering CI/CD Pipelines. In Proceedings of INForum’24 – National Symposium of Informatics. Porto: University of Porto.

Garci’a-Di’az, V., Espada, J. P., Nunez-Valdez, E. R., G-Bustelo, B. C., and Lovelle, J. M. C. (2010). Combining the continuous integration practice and the model-driven engineering approach. Comput. Inform. 35, 299–337.

GitHub Inc. (2024). What is a DevOps pipeline? A complete guide. Available online at: https://github.com/resources/articles/devops/pipeline (Accessed August 27, 2024).

GitLab Inc. (2018). GitLab releases auto DevOps to accelerate DevOps lifecycle by 200%. Available online at: https://about.gitlab.com/press/releases/2018-06-22-auto-devops-gitlab-11/ (Accessed December 30, 2024).

GitLab Inc. (2024). Gitlab-runner release history. Available online at: https://gitlab.com/gitlab-org/gitlab-runner/blob/main/CHANGELOG.md (Accessed August 27, 2024).

GitLab Inc. (2025). Get started with GitLab CI/CD. Available online at: https://docs.gitlab.com/ee/ci/ (Accessed February 3, 2025).

Guba, E., and Lincoln, Y. (1994). Competing paradigms in qualitative research. In. N. K. Margaria and Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of Qualitative Research, 105–117. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Karlovs-Karlovskis, U. (2024). Generative artificial intelligence use in optimising software engineering process: a systematic literature review. Appl. Comput. Syst. 29, 68–77. doi: 10.2478/ACSS-2024-0009

Karlovs-Karlovskis, U., and Ņikiforova, O. (2024). Systematic literature review on model transformation for advanced generation of pipelines within DevOps solutions. 2024 IEEE 65th International Scientific Conference on Information Technology and Management Science of Riga Technical University (ITMS), 1–6.

Kitchenham, B., and Brereton, P. (2013). A systematic review of systematic review process research in software engineering. Inf. Softw. Technol. 55, 2049–2075. doi: 10.1016/j.infsof.2013.07.010

Kleppe, A., Warmer, J., and Bast, Wim. (2003). The model driven architecture: Practice and promise. Available online at: http://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&btnG=Search&q=intitle:The+Model+Driven+Architecture:+Practice+and+Promise.+2003#6 (Accessed December 16, 2024).

New Relic (2014). The incredible true story of how DevOps got its name. Available online at: https://newrelic.com/blog/nerd-life/devops-name (Accessed August 27, 2024).

Nikiforova, O., Nikulsins, V., and Sukovskis, U. (2009). Integration of MDA framework into the model of traditional software development. Front. Art. Intellig. Appl. 187, 229–239. doi: 10.3233/978-1-58603-939-4-229,

Nikulsins, V., and Nikiforova, O. (2008). Adapting software development process towards the model driven architecture. Proceedings - The 3rd International Conference on Software Engineering Advances, ICSEA 2008, Includes ENTISY 2008: International Workshop on Enterprise Information Systems, 394–399.

Niu, N., Brinkkemper, S., Franch, X., Partanen, J., and Savolainen, J. (2018). Requirements engineering and continuous deployment. IEEE Softw. 35, 86–90. doi: 10.1109/MS.2018.1661332

Object Management Group (2008). About the Software & Systems Process Engineering Metamodel Specification Version 2.0. Available online at: https://www.omg.org/spec/SPEM/About-SPEM/ (Accessed January 20, 2025).

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., et al. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/BMJ.N71,

Pastor, O., and Molina, J. C. (2007). Model-driven architecture in practice: a software production environment based on conceptual modeling. Cham: Springer.

Rivera, L. F., Villegas, N. M., Tamura, G., Jiménez, M., and Müller, H. A. (2018). UML-driven automated software deployment., in Proceedings of the 28th Annual International Conference on Computer Science and Software Engineering, (USA: IBM Corp.), 257–268.

Schmidt, D. C. (2006). Guest editor’s introduction: model-driven engineering. Computer 39, 25–31. doi: 10.1109/MC.2006.58

Shahin, M., Ali Babar, M., and Zhu, L. (2017). Continuous integration, delivery and deployment: a systematic review on approaches, tools, challenges and practices. IEEE Access 5, 3909–3943. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2017.2685629

Steudel, H., Hebig, R., and Giese, H. (2012 ). A build server for model-driven engineering., in Proceedings of the 6th International Workshop on Multi-Paradigm Modeling, (New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery), 67–72.

Stevens, P. (2020). Connecting software build with maintaining consistency between models: towards sound, optimal, and flexible building from megamodels. Softw. Syst. Model. 19, 935–958. doi: 10.1007/S10270-020-00788-4

Süß, J. G., Swift, S., and Escott, E. (2022). Using DevOps toolchains in agile model-driven engineering. Softw. Syst. Model. 21, 1495–1510. doi: 10.1007/s10270-022-01003-2

Techstrong Group I. (2018). The origins of DevOps: What’s in a name? Available online at: https://devops.com/the-origins-of-devops-whats-in-a-name/ (Accessed August 27, 2024).

Tegeler, T., Teumert, S., Schürmann, J., Bainczyk, A., Busch, D., and Steffen, B. (2021). An introduction to graphical modeling of CI/CD workflows with rig. In T. Margaria and B. Steffen (Eds.), Leveraging Applications of Formal Methods, Verification and Validation. Lecture Notes in Computer Science 13036, pp. 3–17. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

The Object Management Group (2017). Unified modeling language specification version 2.5.1. Available online at: https://www.omg.org/spec/UML/2.5.1/About-UML (Accessed August 27, 2024).

Keywords: model-driven, engineering, build, DevOps, pipeline, UML, meta-model

Citation: Karlovs-Karlovskis U, Ņikiforova O, Pastor O, Jansone A and Vēveris K (2025) From software architecture models to pipelines: a conceptual framework for model transformation in DevOps. Front. Comput. Sci. 7:1714197. doi: 10.3389/fcomp.2025.1714197

Edited by:

Kyriakos Kritikos, University of the Aegean, GreeceReviewed by:

Kevin Lano, King's College London, United KingdomAlireza Rouhi, Azarbaijan Shahid Madani University, Iran

Copyright © 2025 Karlovs-Karlovskis, Ņikiforova, Pastor, Jansone and Vēveris. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Uldis Karlovs-Karlovskis, VWxkaXMuS2FybG92cy1LYXJsb3Zza2lzQHJ0dS5sdg==

Uldis Karlovs-Karlovskis

Uldis Karlovs-Karlovskis Oksana Ņikiforova

Oksana Ņikiforova Oscar Pastor

Oscar Pastor Anita Jansone

Anita Jansone Kristijans Vēveris1

Kristijans Vēveris1