- Hunan Provincial Higher Education Institutions Key Laboratory of Small and Micro Intelligent Agricultural Machinery Equipment and Application, Hunan Engineering Research Center for Smart Agriculture (Fruits and Vegetables) Information Perception and Early Warning, School of Intelligent Manufacturing, Hunan Institute of Intelligent Manufacturing and Big Data Modern Industry, Hunan University of Science and Engineering, Yongzhou, Hunan, China

This study addresses the queuing inefficiencies caused by synchronized battery-swapping demands for electric trucks in open-pit mines. Through Discrete Event Simulation (DES), we identified systemic bottlenecks stemming from this synchronization. To mitigate this, we propose a hierarchical off-peak battery-swapping scheduling framework comprising an inner-layer Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) and an outer-layer Bayesian Optimization (BO) mechanism. Validated through three large-scale case studies, the model achieved 65% and 80% reductions in queuing times for single and dual loading platform scenarios, respectively, with 5.2%–5.7% improvements in transport throughput. Notably, expanding battery-swapping stations to four achieved equivalent efficiency gains (667 trips) as the optimization strategy (665 trips), highlighting the cost-effectiveness of intelligent scheduling over infrastructure scaling. Furthermore, in the third case study, by increasing loading platforms to alleviate constraints from upstream processes, the optimized model boosts transportation trips by up to 10%, demonstrating its capability to eliminate battery-swapping bottlenecks and fully unlock the potential of energy replenishment workflows.

1 Introduction

Traditional fuel-powered mining trucks that burn diesel or gasoline emit a large amount of pollutants such as carbon dioxide, nitrogen oxides, and particulate matter into atmosphere (Bai et al., 2024), which exacerbates the ongoing concerns about global climate change. In contrast, electric mining trucks are almost zero emissions as their eletricity can be from renewable energy sources (Zhang et al., 2024). Besides, they also have an advantage in terms of haulage costs (Lindgren et al., 2022). Hence, transport electrification in open-pit mines is becoming a trend (Teng et al., 2024).

Despite this trend, the electrification rate of open-pit mining trucks remains the lowest across all vehicle segments (GlobalData, 2025). This is primarily attributed to the fact that, in the context of open-pit mines, electric-powered mining trucks necessitate batteries of substantially larger capacity, specifically in the range of 700–800 KWh. Even when employing fast charging technology, it requires more than one hour for such a large battery to reach fully charged status. Such extend charging time significantly hinder the production efficiency of open-pit mines. Given the number of mining trucks, excavators, and the capacity of crushing plant, open-pit mines aim to maximize the number of transport trips per unit of time. If electric-powered mining trucks spend excessive time on charging, their avaiable time for transportation is inevitably reduced, leading to a decrease in the number of daily transport trips.

To address the efficiency decline caused by prolonged charging times, battery-swapping electric-powered mining trucks can be deployed as an alternative (Vallera et al., 2021). In battery-swapping mode, robotic arms automatically replace depleted batteries with fully charged ones in an average of 6-8 minutes, which is comparable to refueling times. Thus, this mode is particularly well-suited for open-pit mining operations (Zhu et al., 2023), where stringent demands for rapid energy replenishment are critical. The Chinese open-pit mining sector currently has thousands of battery-swap-capable electric haul trucks in active service.

However, battery-swapping electric mining trucks differ significantly from conventional diesel haulers in terms of operational constraints such as range limitations, the need for battery-swapping infrastructure, and fleet management logistics. Traditional dispatch strategies designed for fuel-based fleets are thus ill-equipped for battery-swapping operations, potentially resulting in suboptimal productivity and elevated haulage costs. Therefore, an optimized dispatch model tailored to these electric trucks is essential (He et al., 2017; Xu et al., 2019).

Recognizing this challenge, researchers have proposed various multi-objective scheduling models to address diverse operational demands. Zhan et al. (2022) conducted a comprehensive review of optimal charging scheduling strategies for battery-swapping stations. The main optimization objectives involved are minimizing operational costs (e.g., charging expenses and battery degradation), maximizing grid stability (peak shaving, renewable energy integration), ensuring user satisfaction (reduced waiting time, service availability) and managing uncertainties in battery swapping demand. Deng et al. (2023) provided a cost-effective framework for the design of battery-swapping station tailored to logistic fleets of electric trucks, integrating battery degradation dynamics and practical charging constraints. The proposed management strategy enhances battery lifespan and reduces lifecycle costs, supporting sustainable electrification of freight transport. Sun et al. (2024) proposed an effective battery-swapping dispatch framework for a self-sustained highway energy system, focusing on balancing battery supply-demand dynamics between battery-charging and batteryswapping stations, while minimizing total transportation costs. To begin with, a deep-learning-based spatiotemporal traffic flow network was designed to accurately forecast the demands, thereby providing a crucial foundation for the subsequent model decisions. Subsequently, a battery-swapping dispatch model was formulated, as an extension of vehicle routing problem. It comprehensively considers multiple cost factors, including the routing cost, which is determined by the distance traveled and a fixed cost per kilometer; the cost associated with the degree of satisfaction, which is contingent upon the accuracy of demand prediction; and the cost of using battery trucks. Concerning the short-term prediction of battery-swapping demands for passenger electric vehicle, Wang et al. (2023) also proposed a series of deep learning modles. A real-world dataset containing 2,529 battery-swapping events collected from 36 battery-swapping stations in Beijing was utilized to train these modles. Wang et al. (2024) pointed out that high investment costs and suboptimal operational strategies hinder the profitability of battery-swapping stations for heavy-duty electric trucks. To address these challagens, they proposed a novel scheduling method and a two-layered optimization framework to enhance the performance of battery-swapping stations, while integrating photovoltaic systems for cost-effectiveness. Yang et al. (2024) presented an online scheduling framework to dispatch batteries between battery-charging stations and battery-swapping stations efficiently, combining partial delivery logistics and real-time optimization to enhance operational flexibility and reduce costs. The proposed solving algorithm balances computational efficiency and solution quality, making it suitable for practical electric vehicle infrastructure management. Besides, the solving algorithm is embedded in a rolling-horizon framework with the introduction of dummy copies, which enables the algorithm to tackle future uncertainties in the prediction of battery demands. Regarding the same type of problems within this battery-swapping-charging system, Zhang and Wang (2016) proposed a two-direction model which is solved by particle swarm optimization(PSO) method to reduce transportation cost. Huang et al. (2021) established a nonlinear Mixed-Integer Programming model considering dynamic electricity prices to determine the optimal charging schedules for batteries in battery-charging stations and transportation schedules for the dispatch of batteries. Ban et al. (2021) focused on battery-swapping-charging system composed of multiple nanogrids and battery-swapping stations. The system aims to enhance energy supply cleanliness and promote transportation electrification by aggregating distributed renewable energy sources. The authors established a joint optimal scheduling model based on mixed-integer linear programming, which takes into account battery charging/discharging in the battery-swapping stations, battery swapping among individual units, and the vehicle routing problem of battery transporters. To simplify the model, several pre-processing technologies and assumptions are employed, such as setting dummy copies and discretizing the planning interval. Besides, Jordehi et al. (2021) investigated the placement of battery-swapping stations in microgrids with various renewable energy sources. The authors formulated a nonlinear Mixed-Integer Programing model considering multiple constraints. Case studies show that location of battery-swapping stations significantly impacts operation cost of microgrids. From the perspective of the battery-swapping scenario of electric trucks in open-pit mines, the work by Xiao et al. (2024) is the most related one. The authors proposed a multi-objective scheduling optimization model, aiming to minimize total haulage cost and total waiting time during a single shift(about 8 hours). The model takes into account unique features like battery-swapping alerts, station selection, and the impact of ambient temperature on battery capacity.

While prior studies have established foundational frameworks for developing battery dispatch strategies in open-pit mine electric haulage systems, our comprehensive literature review reveals a critical gap in real-time scheduling optimization for battery-swapping operations. The most related research (Xiao et al., 2024) appears predominantly focused on static scheduling models, leaving dynamic operational scheduling with fluctuating energy demands substantially underexplored. This gap becomes particularly acute in scenarios characterized by high-density truck deployment coupled with insufficient swapping infrastructure, where limited battery inventory at individual stations creates operational bottlenecks. Such resource-constrained conditions inevitably lead to queuing inefficiencies during peak demand periods, adversely impacting overall productivity through extended equipment downtime. In response to these operational challenges, this study proposes a hierarchical scheduling optimization model with queuing time minimization as its primary objective. The core architecture comprises of an inner-layer of Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) and an out-layer of Bayesian optimization (BO). This two-layer design resolves multi-truck coordination complexity in battery-constrained scenarios while keeping computations feasible via reduced parameter space. To formulate the inner MILP, the planning interval is discretized (Ban et al., 2021). In a sort of way, this pre-processing technology can also enables decision-making under uncertainly.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 deconstructs the operational workflow of battery-swapping electric trucks in open-pit mines, followed by a Discrete Event Simulation (DES) to quantify bottlenecks under varying truck densities and station capacities. Section 3 formulates the hierarchical optimization framework. Section 4 validates the framework through several case studies, benchmarking its efficacy against conventional scheduling strategies via several metrics (such as total trips and waiting time at the battery-swapping stations). Section 5 concludes with theoretical and practical implications.

2 The workflow in open-pit mines

2.1 System description

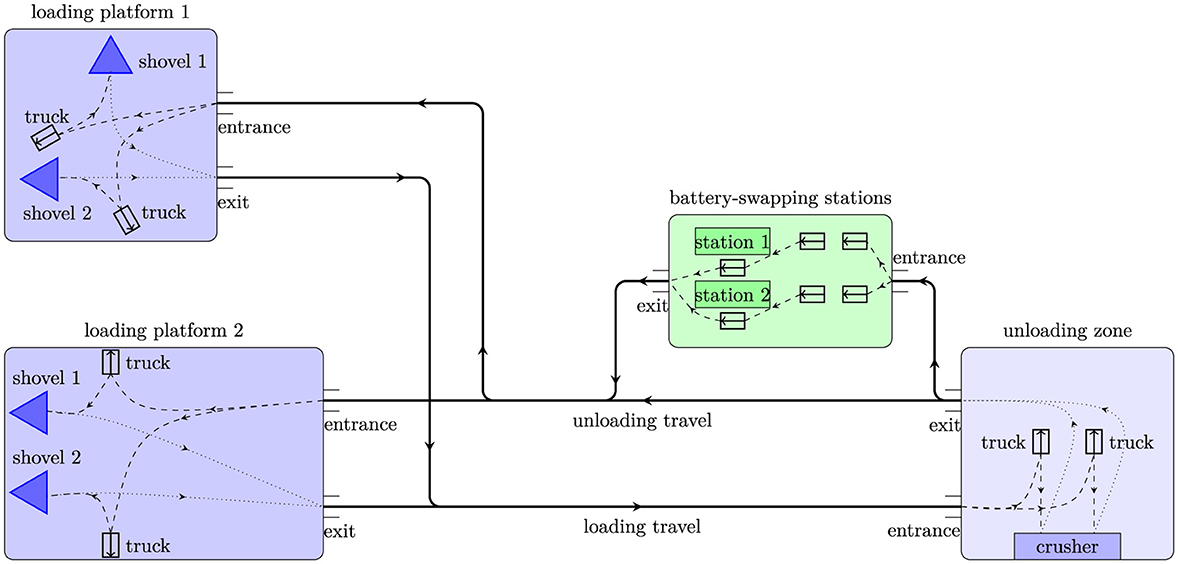

The transportation system with battery-swapping trucks in open-pit mines comprises multiple operational nodes, including loading platforms, unloading zones, and battery-swapping stations. Electric haul trucks cycle continuously between these nodes to transport materials while periodically requiring battery exchanges at designated swapping stations, as depicted in Figure 1.

In line with the workflow depicted in Figure 1, a simple scheduling method for mining truck battery swapping functions as follows. Once unloading is completed, the system assesses whether the truck's remaining battery capacity can support one more haul cycle. If it can, the truck is sent to continue its hauling operations. If not, it is routed to the battery-swapping station with a shorter queue for battery replacement. At the station, trucks in the queue are served strictly on a first-come-first-served (FCFS) basis, without considering any operational priority levels. However, this straightforward scheduling approach may give rise to two issues. Firstly, when the battery depletion moments of a large number of mining trucks approach simultaneously, these trucks will flock to the battery-swapping stations for battery replacement. Due to the limited capacity of the battery-swapping stations and the finite number of fully charged batteries, long queues will be formed, which will affect the operational duration of the mining trucks and cause traffic congestion around the battery-swapping stations. Secondly, FCFS basis is suboptimal and as a result, the total queuing time for battery replacement of the entire fleet may be excessively long.

2.2 Discrete event simulation of the system

Discrete Event Simulation (DES) is a computational modeling approach that mimics the dynamic behavior of complex systems by simulating discrete events (e.g., task arrival, service completion) occurring at specific time points (Banks et al., 2013). Unlike continuous simulation, which models systems with smooth state changes (e.g., fluid flow), DES focuses on abrupt state transitions triggered by events. For example, in mining truck scheduling, DES tracks when trucks arrive at battery-swapping stations, how long they queue, and when they resume hauling, considering random battery depletion times and station capacities (Huayanca et al., 2023). Such a simulation can help identify bottlenecks and improve resource allocation.

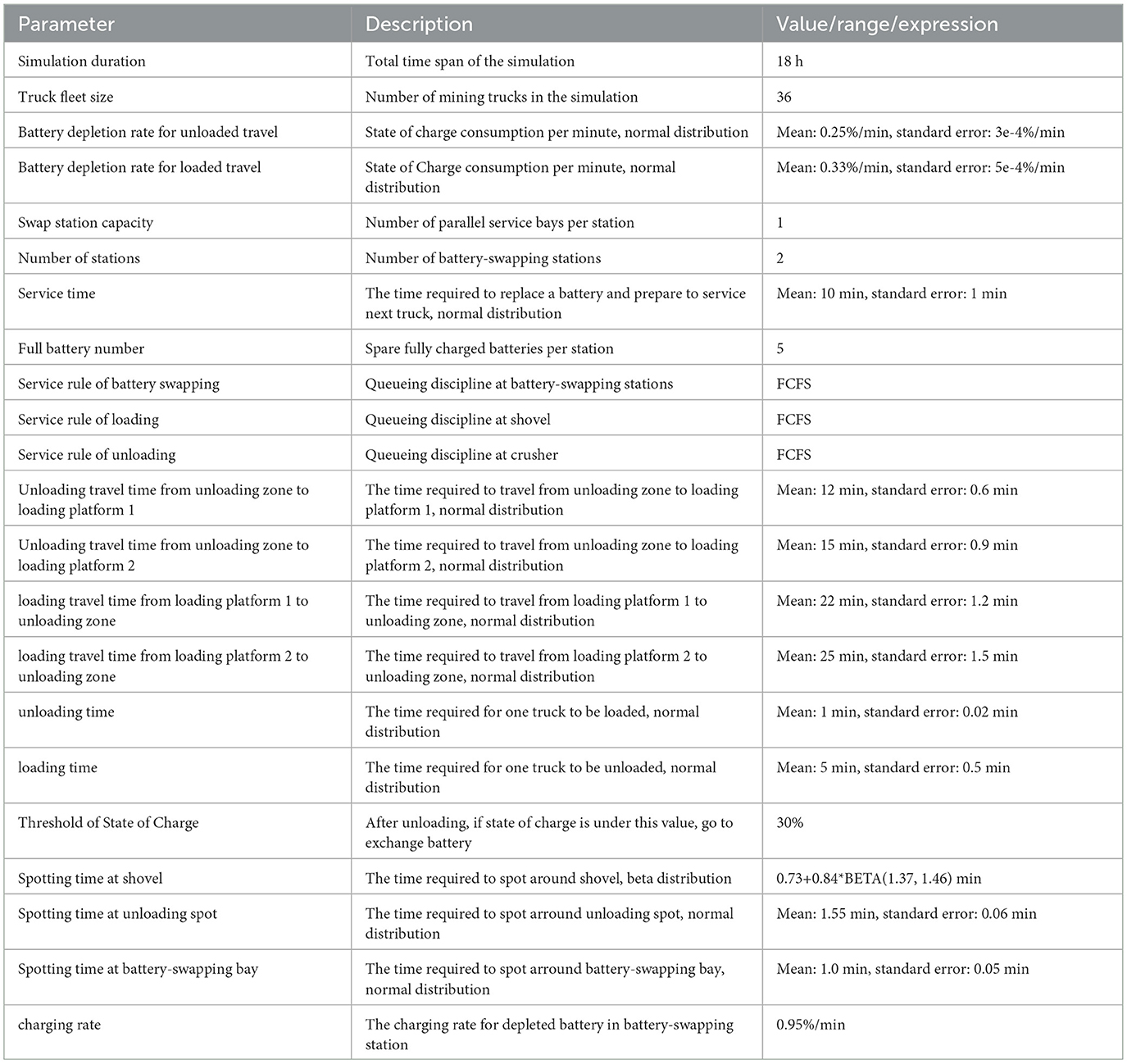

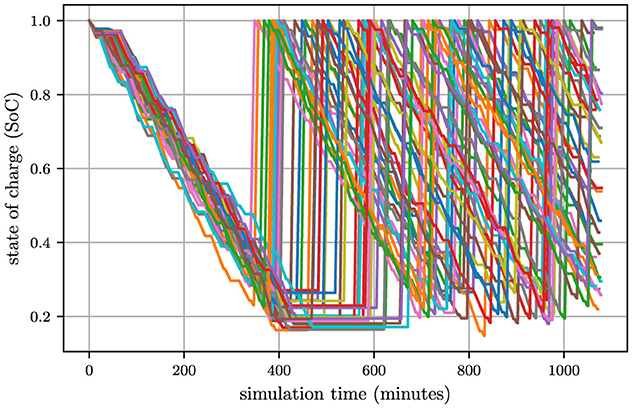

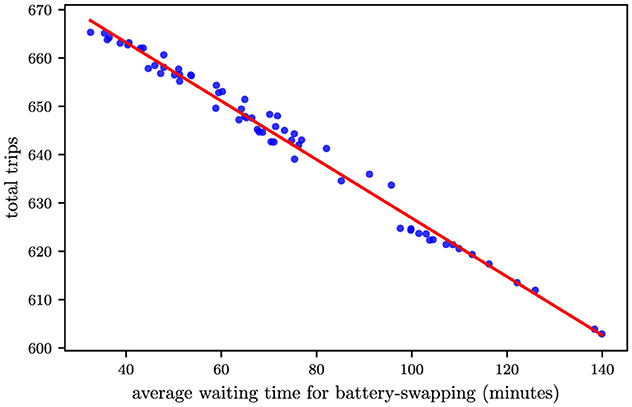

In this paper, we conduct a discrete event simulation (DES) to model the workflow in open-pit mines. The parameter configurations for the simulation are summarized in Table 1. These settings are based on an actual open-pit coal mine and the work by Huayanca et al. (2023). The simulation framework encompasses three interconnected processes: loading, unloading, and battery-swapping. Initially, all trucks—equipped with a preset state of charge (SoC)—depart from the unloading zone and travel to designated loading platforms. Upon arrival, trucks queue at the loading platform until they are loaded with material. Once loaded, they return to the unloading zone for material discharge. After completing the unloading process, the system evaluates whether the truck's remaining SoC is sufficient for another hauling cycle. If the SoC falls below the required threshold, the truck is redirected to a battery-swapping station to replace its depleted battery with a fully charged one. Given the inherent uncertainties in travel time, spotting time, battery-swapping duration, and other operational variables, the simulation—modeling an 18-hour production period—was executed 100 times to account for stochastic variations. The results yielded an average of 628 total trips completed across all iterations, while the average waiting time for battery-swapping stood at 86.6 minutes. Figure 2 illustrates the relationship between total trips and battery-swapping station wait times through a scatter plot. As shown, a distinct negative correlation emerges between these two metrics, suggesting that prolonged battery-swapping delays directly reduce the number of achievable haulage cycles. This inverse relationship positions battery-swapping operations as a potential critical bottleneck in the production workflow.

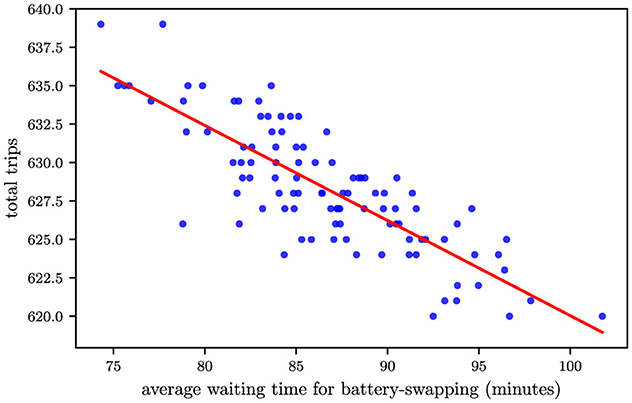

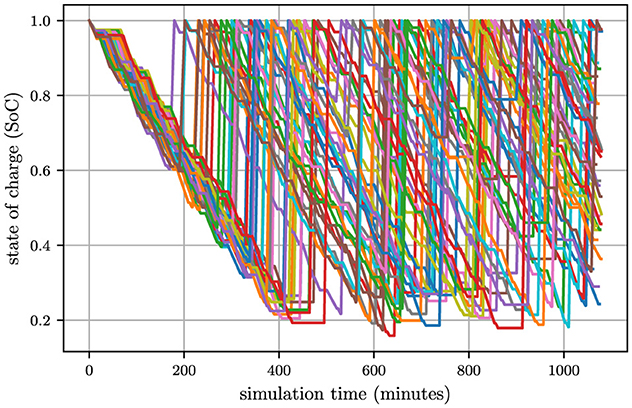

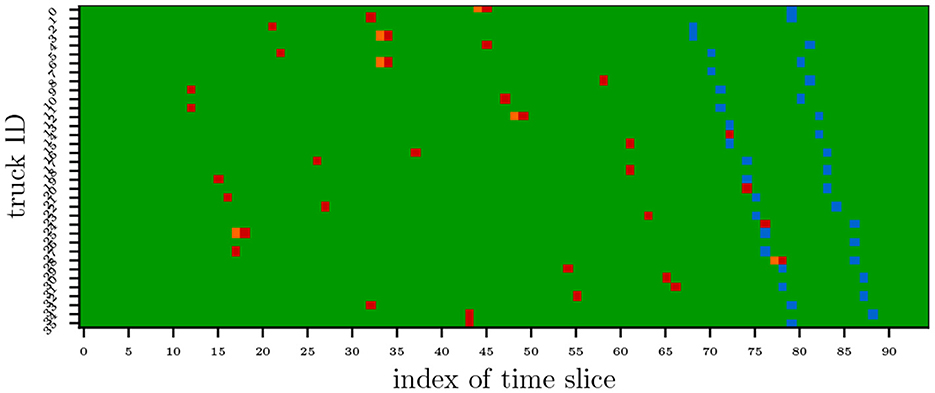

To investigate the root cause of prolonged battery-swapping delays, Figure 3 visualizes the state of charge (SoC) time series for all trucks during one representative simulation run. The data reveals a critical synchronization issue: during the first battery-swapping cycle, all trucks converge on the swapping stations approximately 350 min after production initiation. This synchronization creates a demand surge that overwhelmes the stations limited capacity, forcing some trucks in this cohort to endure wait times exceeding two hours for battery replacement. Notably, subsequent swapping cycles exhibite significantly reduced delays, as evidenced by the dispersed timing of later SoC troughs in Figure 3.

This stark contrast between the first and subsequent cycles strongly suggests that synchronized battery-swapping demand–rather than inherent station inefficiency—is the primary driver of bottlenecks. The clustering of trucks at the stations during peak intervals directly correlates with the observed productivity loss (i.e., reduced total trips). These findings imply that decentralizing battery-swapping activity through demand-leveling strategies, such as staggered battery replacement schedules or predictive SoC-based dispatching, could mitigate congestion and unlock throughput gains. Consequently, designing an off-peak battery-swapping protocol emerges as a critical priority for optimizing production efficiency in open-pit mining operations.

To further validate these findings, we designed a proactive staggered battery-swapping strategy to mitigate synchronization-induced bottlenecks. The strategy involves dynamically selecting Z trucks with state of charge (SoC) below Y% at X-minute intervals for prioritized battery replacement, contingent on the availability of fully charged batteries at the swapping stations. To prevent overloading station capacity, the parameter Z caps the maximum number of trucks dispatched per interval–even when surplus charged batteries are available, only Z trucks are proactively rerouted. To identify the optimal parameter combination (X, Y, Z), we performed a grid search over the hyperparameter space: X:[10, 15, 20, 25] × Y:[40, 50, 60, 70] × Z:[2, 3, 4, 5]. For each combination, the simulation was replicated 100 times, with results averaged to compute total trips completed and average battery-swapping wait time. The optimal combination (X = 25, Y = 70, Z = 3) yielded 665 total trips—a 5.7% improvement over the baseline (628 trips)—while reducing average battery-swapping wait time to 32.5 min (from 86.5 min). Figure 4 illustrates the SoC time series under this configuration, demonstrating the near-elimination of prolonged delays during the initial battery-swapping cycle. Meanwhile, Figure 5 plots total trips against average wait time across all parameter combinations, reaffirming the negative correlation observed earlier. This consistent trend underscores battery-swapping efficiency as a leverage point for systemic productivity gains, with suboptimal scheduling directly constraining haulage throughput.

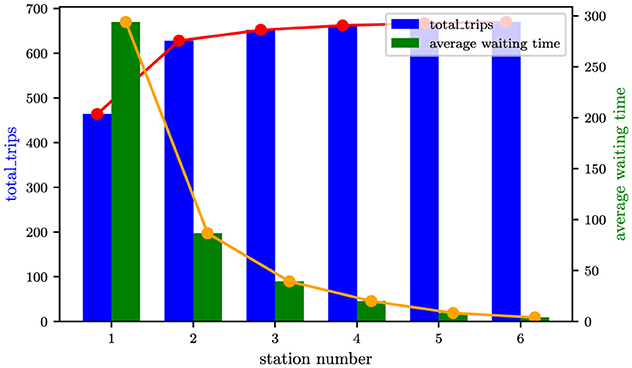

Another way to assess whether battery-swapping efficiency constitutes the dominant bottleneck is by analyzing the relationship between total haulage trips and the number of battery-swapping stations. As demonstrated in Figure 6, increasing the number of stations initially drives a near-linear improvement in total trips, followed by a plateau (even though the waiting time decreases sharply) as the system transitions to being constrained by other workflow components–such as truck fleet size, shovel loading capacity, or crusher throughput. Notably, expanding the number of stations to 4 achieves a throughput (667 trips) parity with the optimized staggered battery-swapping strategy proposed earlier (665 trips).

Figure 6. The effect of increasing station number on total trips and waiting time at battery-swaping stations.

While both approaches alleviate battery-swapping congestion, their cost implications diverge significantly. Deploying additional stations necessitates substantial capital investment in infrastructure and battery inventory. In contrast, the staggered scheduling strategy–requiring no hardware expansion–achieves comparable efficiency gains through operational optimization. This contrast underscores that smarter dispatching protocols, rather than infrastructure scaling, represent a cost-effective lever for mitigating bottlenecks in open-pit mining operations.

Building on the operational insights derived from the simulation experiments, the subsequent section proposes an optimization-driven framework for battery-swapping scheduling. This framework systematically reduces synchronization induced delays by integrating real-time state of charge (SoC) monitoring, station capacity constraints, and dynamic truck dispatching, thereby establishing a generalizable methodology to alleviate bottlenecks in open-pit mining operations.

3 Optimization-based heriarchical model

In this section, we propose a hierarchical optimization framework for off-peak battery-swapping scheduling, with the primary objective of minimizing queuing delays at battery-swapping stations. The framework integrates a Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) model and a Bayesian Optimization layer to address both operational and systemic bottlenecks. At its core, the MILP model optimizes short-term resource allocation within stations by resolving battery availability, truck sequencing, and service time constraints, thereby maximizing the inherent efficiency of individual stations. Simultaneously, the Bayesian Optimization layer governs the outer loop of the hierarchy, dynamically determining optimal battery-swapping timings for each truck to avoid synchronization-induced congestion–specifically targeting the prolonged delays observed during the first battery-swapping cycle (Section 2). By coordinating these two layers, the framework ensures that real-time scheduling decisions align with long-term system-wide efficiency goals: the MILP model fine-tunes station-level operations, while Bayesian Optimization proactively redistributes battery-swapping demand across temporal and spatial dimensions. The following subsection details the formulation of the MILP model first, which serves as the computational foundation for this hierarchical approach.

3.1 Mixed-Integer Linear Programming model

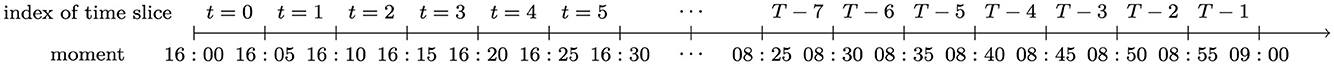

Given the predicted battery-swapping demand moments during the first battery-swapping cycle (Section 2), the scheduling of electric mining trucks across multiple stations is formulated as a Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) model. The formulation begins with a temporal discretization step, where continuous time is partitioned into fixed intervals. This approach converts the intractable continuous-time optimization problem into a discrete, computationally tractable counterpart. Crucially, temporal discretization enhances robustness against demand prediction uncertainties by enabling probabilistic adjustments to resource allocations within each interval—a mechanism that mitigates timing discrepancies between forecasted and actual demand. For illustration, Figure 7 demonstrates a 5-minute time-slice configuration. This discretization eliminates the need for exact demand timing predictions (e.g., 16:15). Instead, when a demand surge is projected for the third time slice, any occurrence within the corresponding 16:15 − 16:20 window remains operationally viable. Such flexibility ensures resilience to minor temporal prediction errors while maintaining scheduling feasibility.

Within this discretized framework, the decision variable in the MILP model is defined as a binary parameter:

Here, xi, j, t = 1 indicates that the dispatching system allocates truck i to the j−th station for battery swapping at the t−th time slice, while xi, j, t = 0 denotes no such assignment. For a fleet of 36 electric mining trucks with projected battery-swapping demands over a 4-hour horizon, the MILP model's total number of decision variables is calculated as 36(trucks) × 48(time slices) × 2(stations) = 3, 456, where the temporal resolution is discretized into 5-min time slices (yielding intervals) and two battery-swapping stations are available. This parameterization ensures the model systematically encodes all potential scheduling permutations through the binary variable xi, j, t—defined in Equation 1—while maintaining computational tractability under the discretized temporal and spatial constraints outlined in Section 2.

The model's objective function explicitly minimizes the total queuing time, addressing the synchronization-induced bottlenecks identified in Section 2, while enforcing operational constraints such as station capacity limits, battery availability, and truck SoC thresholds. The objective function is defined as:

where I is the total number of trucks, Si denotes the start time of battery-swapping for truck i and Ai represents the arrival time of truck i, which corresponds to the predicted battery-swapping demand time (an input to the MILP model). The start time Si is derived from the binary decision variable xi, j, t—defined in Equation 1, which assigns truck i to station j at time slice t, and is calculated as:

where J is the total number of battery-swapping stations, T is the total number of discrete time slices, and t indexes the time slices (e.g., t = 0, 1, …, T−1). This formulation ensures that each truck is assigned to exactly one station within a single time slice, translating the continuous-time scheduling problem into a tractable discrete optimization framework.

To ensure the MILP model aligns with operational realities, four critical constraints are incorporated. First, Equation 4 enforces that each truck undergoes exactly one battery-swapping event within the planning horizon, reflecting the focus on the first battery-swapping cycle:

where, xi, j, t is defined in Equation 1. Second, Equation 5 ensures causality by requiring battery-swapping to occur after arrival:

where Si and Ai are defined in Equations 3 and 2, respectively. Third, station throughput limitations are modeled via Equation 6, which restricts each station j to servicing at most one truck within any sliding time window of length Te (battery-swapping and preparation time):

Fourth, battery availability constraints (Equation 7) approximate the finite battery inventory and charging cycle without explicitly tracking individual battery states—a simplification to maintain model tractability. For station j with capacity Nj (maximum stored batteries), the cumulative swaps within the charging time window Tc (time to recharge a depleted battery) must not exceed Nj:

This formulation implicitly enforces that each battery used at time t becomes available again at t+Tc, aligning with the charging cycle while avoiding combinatorial complexity from per-battery tracking.

Batteries are charged in batches at a fixed rate (0.95%/minute), so the charging time window Tc (time to fully recharge a depleted battery) can be precomputed as a deterministic parameter (e.g., 105 minutes for a 100% SoC recovery, consistent with the 700–800 kWh battery capacity). Spare batteries are maintained as a shared pool (5 per station) rather than assigned to specific trucks. Thus, the cumulative number of swaps within Tc directly reflects the maximum number of batteries that can be cycled (used → charged → reused), making the constraint (Equation 7) a reasonable proxy for actual inventory limits. Furthermore, the constraint (Equation 7) could be reformulated as a dynamic one. For a battery-swapping station with multiple charging batteries, their remaining charging times can be estimated and sorted in ascending order. As operational time progresses (e.g., across the MILP's discrete time slices; Section 3.1), each time the time exceeds a remaining charging time in the sorted list, the station's available battery count increases by 1–aligning with the study's operational context.

The proposed MILP model (Equations 1–7) is solved using the open-source solver SCIP (Vigerske and Gleixner, 2016), which outputs the battery replacement schedule–specifically, the optimal battery-swapping station assignment and service order for each mining truck. To generate the model's input (i.e., the predicted battery-swapping demand times during the first cycle), we propose a state-based prediction method tailored to the operational logic of mining trucks. Unlike passenger electric vehicles, where battery-swapping demand can arise continuously, mining trucks can only request battery replacement after completing unloading tasks. This discrete demand pattern arises because trucks must first finish unloading and travel from the unloading zone to a battery-swapping station. The state-based method estimates available battery-swapping moments based on a truck's current operational state:

• Unloading or queuing for unloading: The available time is calculated as Tre+TUL→S (where Tre is the remaining unloading time and TUL→S is the travel time to a station) or n·Tul+TUL→S (where n is the number of trucks queuing ahead and Tul is the average unloading time).

• Loading, traveling to loading platform, or returning to unloading zone: The truck's state is first reduced to the equivalent unloading-area state (e.g., estimating remaining time until unloading completion), after which the above logic applies.

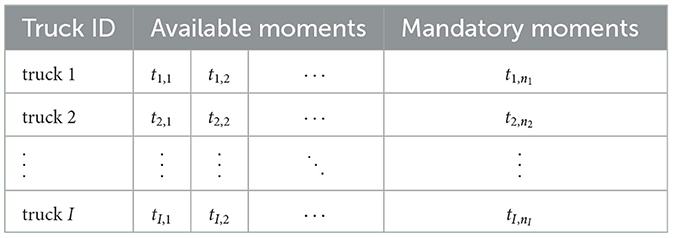

This approach ensures that battery-swapping demands align with the discrete operational milestones inherent to mining workflows, thereby enabling accurate input generation for the MILP model. The state-based method generates outputs such as those illustrated in Table 2, where mandatory battery-swapping times correspond to instances when the battery is depleted (i.e., the remaining state of charge, SoC, is insufficient to sustain another operational cycle), and n1, n2, …, nI denote the number of available battery-swapping times for trucks 1, 2, …, I, respectively. The final input to the MILP model is an aggregated set of predicted demand times, structured as [t1, 2, t2, 1, ⋯ , ti, l, ⋯ , tI, k] from Table 2. Here, ti, l represents the l−th battery-swapping time scheduled for truck i, and tI, k denotes the k−th time allocated to truck I, where I is the total number of trucks in the fleet.

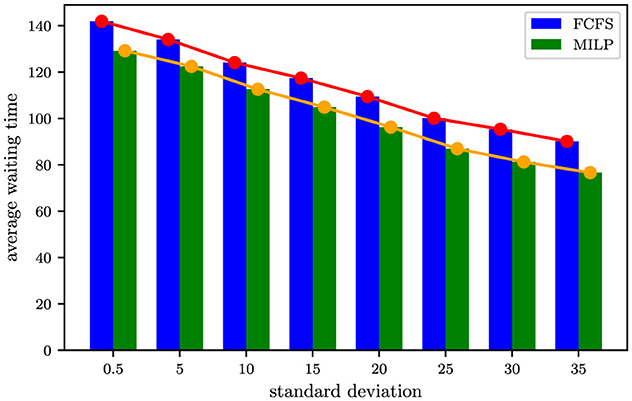

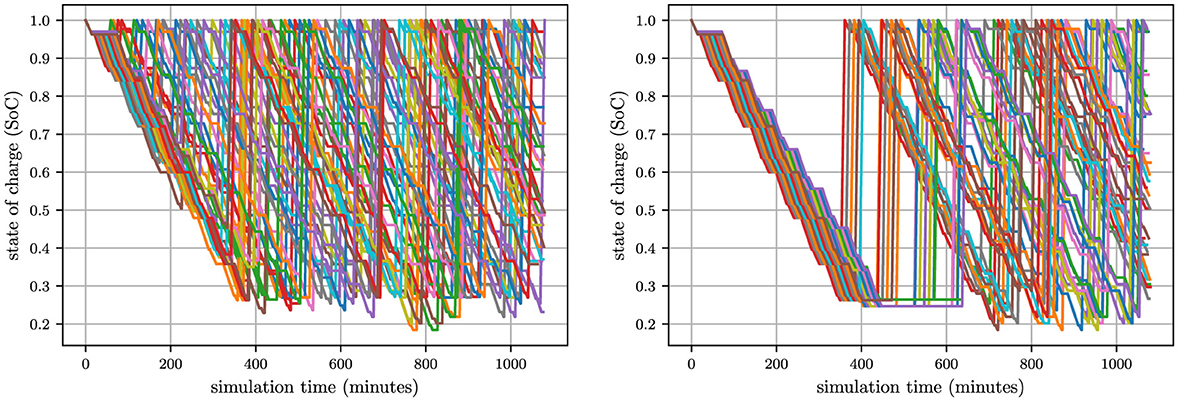

First, we evaluate the potential of the MILP model to mitigate queuing delays for mining trucks at battery-swapping stations. To this end, input parameters for the MILP model are generated using a normal distribution with a mean of 210 (i.e., 3.5 hours after the current time). By systematically varying the standard deviation (σ), we simulate distinct temporal distributions of battery-swapping demand times across a fleet of 36 mining trucks. Smaller σ values produce more clustered demand profiles, emulating scenarios with synchronized battery depletion–a critical bottleneck in mining operations. Figure 8 compares the average waiting times achieved by MILP-optimized scheduling against the baseline First-Come-First-Served (FCFS) strategy. The results reveal a maximum reduction of 15 minutes in queuing time at σ = 35, whereas the minimum reduction of 12 minutes occurs under the most concentrated demand scenario (σ = 0.5). This demonstrates that merely enhancing intrinsic station throughput (e.g., faster battery swapping) cannot resolve synchronization-induced congestion, underscoring the necessity of off-peak scheduling to address systemic inefficiencies.

3.2 Bayesian optimization

Figure 8 reveals that greater dispersion in battery-swapping demand distributions correlates with shorter average waiting times, regardless of scheduling strategy (MILP or FCFS). This observation suggests an intuitive off-peak strategy: by systematically exploring all feasible battery-swapping time combinations derived from Table 2, one could theoretically identify the optimal schedule with minimal queuing time. However, this approach is computationally intractable due to combinatorial explosion. To illustrate, consider a fleet of 40 mining trucks, each with 4 candidate battery-swapping times before battery depletion. The total number of combinations is 440≈1024. Assuming an MILP solver requires 1 second per combination, exhaustive evaluation would demand 1024 seconds (≈1016 years)–a timescale exceeding practical feasibility.

Bayesian optimization is a data-driven method for efficiently optimizing black-box functions (e.g., complex systems with unknown analytical forms). Its core mechanism involves constructing a probabilistic surrogate model—typically a Gaussian process—to approximate the objective function. By iteratively updating this model with prior observations, Bayesian optimization computes a posterior distribution that balances exploration (sampling uncertain regions) and exploitation (refining known promising regions), thereby guiding the search toward globally optimal solutions. To address the combinatorial explosion inherent in scheduling problems, Bayesian optimization circumvents exhaustive enumeration of all combinations. Instead, it leverages the surrogate model's probability estimates to prioritize candidate solutions with higher likelihoods of optimality. This is achieved through an acquisition function (e.g., Expected Improvement), which intelligently selects the next evaluation point based on the posterior distribution. By focusing computational resources on high-potential regions, Bayesian optimization dramatically reduces the effective search space, mitigating the computational burden caused by combinatorial explosion (e.g., reducing 1024 combinations to a tractable subset).

For the off-peak battery-swapping scheduling problem under study, the objective function approximated via Bayesian optimization is formally defined as:

where denotes the feasible solution space of battery-swapping time combinations, and ℝ maps to the real-valued output of either the MILP model (Equations 1–7) or the FCFS queuing time calculation. One sample in can be expressed as , with ti, l representing the l−th battery-swapping time scheduled for truck i as defined in Table 2. By treating f as a computationally expensive black-box function, Bayesian optimization constructs a probabilistic surrogate model (e.g., Gaussian process) trained on prior evaluations to guide the search toward high-potential regions of , thereby avoiding exhaustive enumeration of all combinations (e.g., 440) and balancing exploration-exploitation trade-offs through acquisition functions like Expected Improvement (EI) and Upper Confidence Bound (UCB).

At the core of the Gaussian process (GP) lies the assumption that the function values of any finite set of points follow a joint Gaussian distribution, formally expressed as:

where μf(c) is the mean function (set to 0 due to the absence of prior knowledge, ensuring reliance on the kernel for localized feature capture) and k(c, c′) is the covariance kernel quantifying similarity between combinations c and c′. We employ the Matérn 5/2 kernel, defined as:

where is the L2-norm distance between c and c′. This kernel's twice-differentiable properties balance smoothness and flexibility, critical for modeling queuing time trends and localized demand variations in battery-swapping scheduling. Another advantage of this kernel function is that there is no need for hyperparameter optimization.

With the Gaussian process framework (Equations 9–10), the queuing time for a mining truck fleet under a new battery-swapping schedule can be probabilistically predicted using observed historical data. Let denote a set of m observed combinations of battery-swapping times, and f = [f(c1), f(c2), …, f(cm)]T represent their corresponding queuing times (computed via MILP or FCFS). For a candidate combination c*, Bayesian inference yields the posterior distribution of its predicted queuing time::

where the posterior mean μ(c*) and variance σ(c*) are derived as:

Here:

• k(c*, C) = [k(c*, c1), …, k(c*, cm)] is a 1 × m row vector of kernel similarities between c* and observed combinations;

• K(C, C) is the m×m kernel matrix with entries ;

• σob is the observation noise standard deviation, set to 0 in this work to reflect deterministic queuing time evaluations;

• E is a m×m identity matrix;

• k(C, c*) = k(c*, C)T is a column vector.

Once the Gaussian process surrogate model is established, the Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) acquisition function guides the selection of the next candidate solution to evaluate. The UCB is defined as:

where μ(c*) and σ(c*) are the posterior mean and standard deviation from Equation 12, and κ = 2.5 is a hyperparameter balancing exploration (prioritizing uncertain regions) and exploitation (refining known optima). At each Bayesian optimization iteration:

• A batch of candidate combinations {c*} is sampled from .

• Their UCB values are computed via Equation 14.

• The combination citer = 1 with the highest UCB is selected, evaluated (via MILP or FCFS), and added to the observation set:

After N iterations, the augmented datasets become:

The optimal battery-swapping schedule cbest corresponds to the combination with the minimum queuing time in fiter = N. This iterative process efficiently navigates the combinatorial space , avoiding exhaustive evaluation of all 440 combinations while balancing data-driven exploration and exploitation.

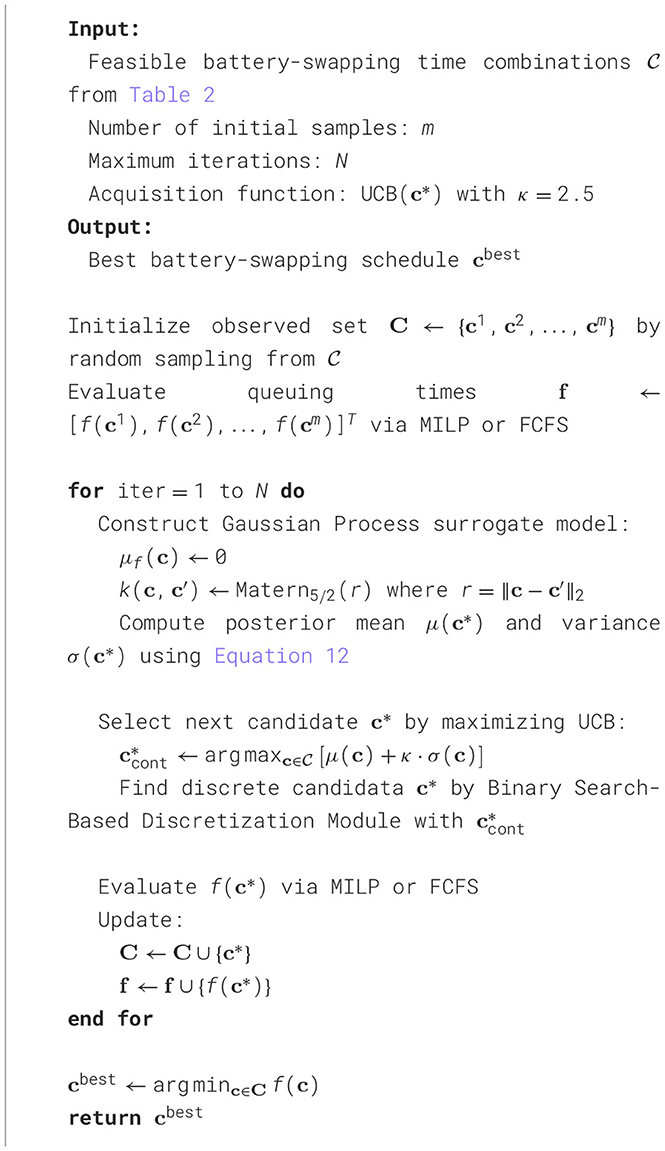

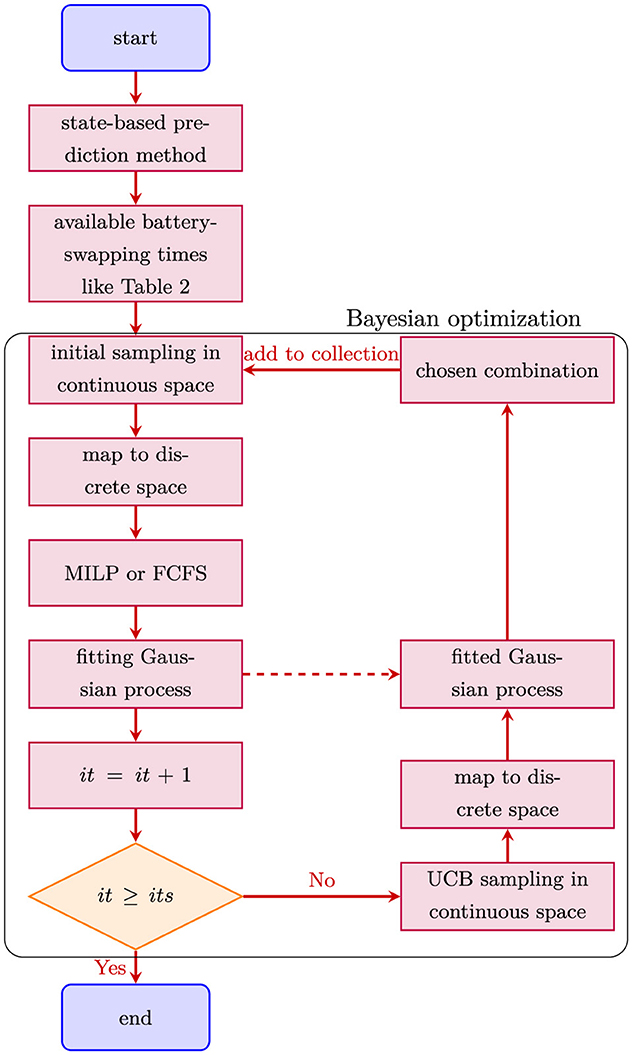

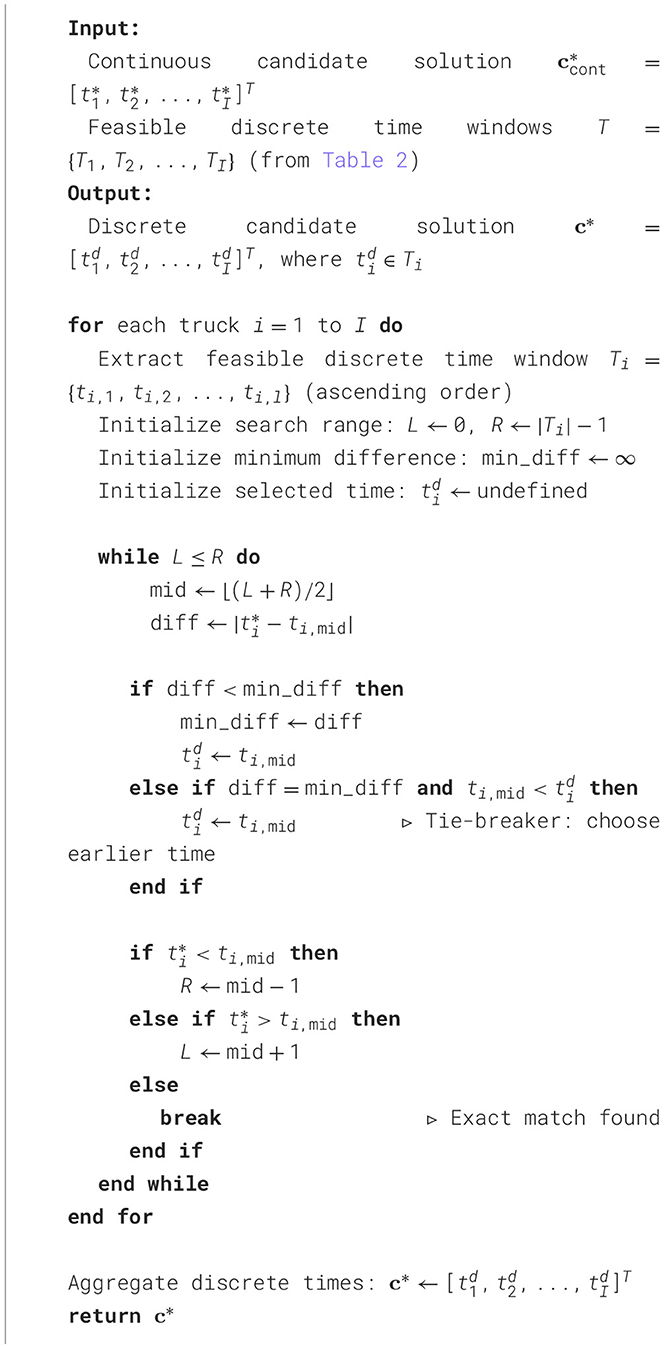

With both the inner MILP model (Equations 1–7) and the outer Bayesian optimization (Equations 9–14) rigorously defined, the proposed hierarchical optimization framework is systematically established (detailed in Algorithm 1), as illustrated in Figure 9. To adapt Bayesian optimization—originally designed for continuous decision variables—to the discrete combinatorial space , a binary search-based discretization module (detailed in Algorithm 2) is integrated. This module maps continuous samples generated by the Gaussian process surrogate model to the nearest valid discrete battery-swapping times (Table 2), ensuring feasibility while preserving the probabilistic exploration-exploitation balance. The hierarchical integration of MILP (exact queuing time calculation) and Bayesian optimization (global search guidance) enables near-optimal scheduling with drastically reduced computational effort.

4 Case studies

4.1 Case study 1: single loading platform and unloading zone

The first scenario simulates battery-swapping operations in an open-pit mine with one loading platform (equipped with two excavators) and one unloading zone (serving a single crusher). Key operational parameters include:

• Haul Road Configuration: A 4-km bidirectional route connecting the loading and unloading zones.

• State of Charge (SoC) consumption:

– Unloading travel (empty haul): 5% SoC consumed over 10 min.

– Loading travel (loaded haul): 10% SoC consumed over 15 min.

• Processing Times:

– Unloading: 3 min (average) at the crusher.

– Loading: 5 min (average) per excavator.

• Initial fleet state:

– Each excavator is actively loading one haul truck, with 3 trucks queued per excavator (total 6 trucks waiting to load).

– 28 trucks are in transit (empty-hauling) between zones.

These settings are based on an actual open-pit coal mine. Using these inputs, the state-based prediction module (Section 3) generates a discrete battery-swapping schedule (Table 2) by simulating truck trajectories, energy consumption, and queuing dynamics. This table provides all feasible battery-swapping time windows for the fleet, serving as input to the hierarchical optimization framework (Figure 9) for minimizing queuing delays.

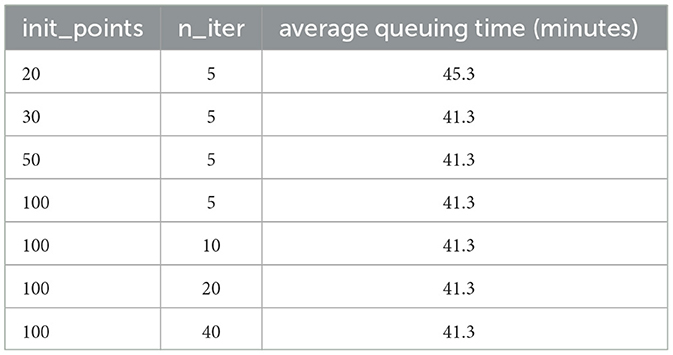

A systematic sensitivity analysis evaluates the impact of initial sampling points (init_points) and Bayesian optimization iterations (n_iter) on solution quality. As shown in Table 3, increasing init_points enhances solution optimality initially but plateaus beyond a threshold (e.g., init_points=30), suggesting sufficient exploration of the combinatorial space . In contrast, increasingn_iter beyond 5 yields diminishing returns, indicating rapid convergence of the Gaussian process surrogate model. Based on these findings, subsequent experiments adoptinit_points=30 and n_iter=5, balancing computational efficiency with solution quality. This configuration ensures robust exploration-exploitation trade-offs while aligning with the hierarchical framework's goal of mitigating combinatorial explosion (Section 3).

Table 3. The effect of the number of initial sampling points (init_points) and iteration steps (n_iter) on solution in case 1.

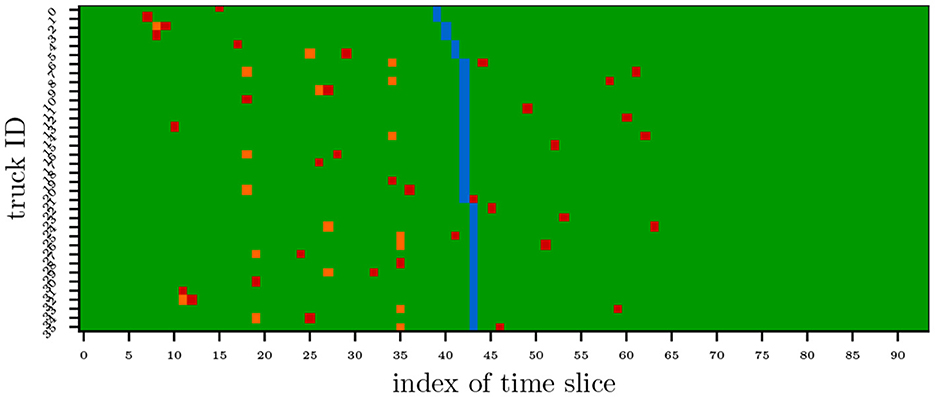

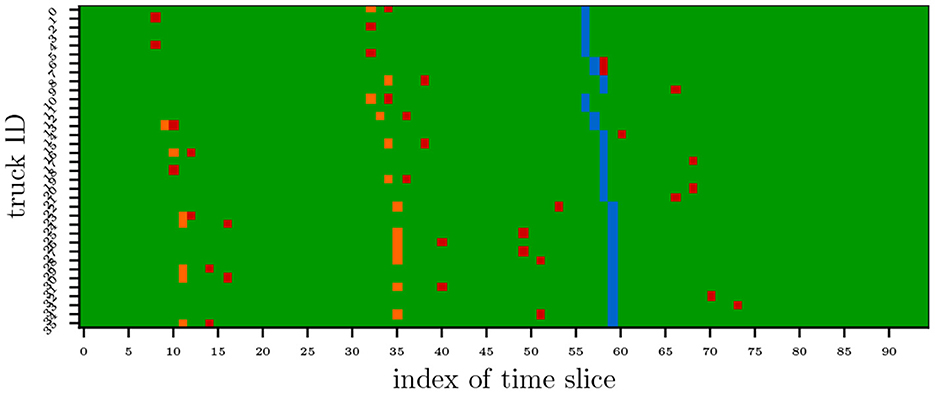

Figure 10 illustrates the scheduling outcomes generated by the Hierarchical Framework (Section 3). The results demonstrate that the framework proactively schedules more than 50% of trucks for battery swaps prior to SoC depletion, effectively dispersing demand peaks and reducing total queuing time. The optimized schedule achieves an average queuing time of 41.3 min at the battery-swapping station, representing a 65% reduction compared to the MILP baseline (116.4 min) and a 68% improvement over the FCFS strategy (128.4 min) when both use mandatory battery-depletion moments (Table 2) as input. This performance underscores the framework's ability to balance proactive scheduling (exploiting demand dispersion) with computational efficiency (avoiding the 440 combinatorial search space), validating its superiority over conventional rule-based or exhaustive optimization approaches.

Figure 10. Case 1: the scheduling results generated by the hierarchical framework, the red markers indicate the battery-swapping moments, the orange markers denote the arrival times of trucks at the station, and the blue markers represent the battery depletion moments (when the battery's State of Charge reaches critical levels).

4.2 Case study 2: dual loading platforms and unloading zone

The second scenario models battery-swapping operations in an open-pit mine with two loading platforms (each equipped with two excavators) and one unloading zone (serving a single crusher). Key operational parameters include:

• Haul road configuration:

– A 3-km bidirectional route connects the first loading platform to the unloading zone.

– A 5-km bidirectional route links the second loading platform to the unloading zone.

• State of Charge (SoC) consumption:

– Unloading Travel (Empty Haul) to the first loading platform: 3.75% SoC consumed over 7.5 min.

– Unloading Travel (Empty Haul) to the second loading platform: 6.25% SoC consumed over 12.5 min.

– Loading Travel (Loaded Haul) from the first loading platform: 7.5% SoC consumed over 11.25 min.

– Loading Travel (Loaded Haul) from the second loading platform: 12.5% SoC consumed over 18.75 min.

• Processing times:

– Unloading: 1 min (average) at the crusher.

– Loading: 5 min (average) per excavator.

• Initial Fleet State:

– Each excavator is actively loading one haul truck, with 3 trucks queued per excavator (total 12 trucks waiting to load).

– 10 trucks are in transit (empty-hauling) between the unloading zone and the first loading platform.

– 10 trucks are in transit (empty-hauling) between the unloading zone and the second loading platform.

• Production scheduling:

– Trucks alternate loading platforms for consecutive trips: if a trip loads at the first platform, the subsequent trip must load at the second platform to balance resource utilization.

Using these inputs, the state-based prediction module (Section 3) simulates truck trajectories, energy consumption, and queuing dynamics to generate a discrete battery-swapping schedule (Table 2). This schedule enumerates all feasible battery-swapping time windows, which serve as input to the hierarchical optimization framework (Figure 9) for minimizing queuing delays through proactive demand dispersion.

Figure 11 illustrates the scheduling outcomes generated by the Hierarchical Framework (Section 3). Compared to Case Study 1 (single loading platform), the framework proactively schedules 75% of trucks (versus 50% in Case 1) for battery swaps prior to SoC depletion, achieving enhanced demand dispersion across the dual-platform configuration. The optimized schedule attains an average queuing time of 26.4 min at the battery-swapping station, demonstrating a 78% reduction compared to the MILP baseline (122.5 min) and an 80% improvement over the FCFS strategy (132.1 min), both of which rely on mandatory battery-depletion moments (Table 2).

Figure 11. Case 2: the scheduling results generated by the hierarchical framework, the red markers indicate the battery-swapping moments, the orange markers denote the arrival times of trucks at the station, and the blue markers represent the battery depletion moments (when the battery's State of Charge reaches critical levels).

4.3 Case study 3: dual loading platforms with DES-driven inputs

The third scenario extends the battery-swapping operations to a Discrete Event Simulation (DES)-integrated environment, maintaining the dual loading platforms (each with two excavators) and a single unloading zone (serving one crusher). Key enhancements include:

• Input Generation: Available battery-swapping moments are derived from DES instead of the state-based prediction module, enabling realistic production scheduling with stochastic variations (e.g., delays, resource contention).

• Scalability Validation: The hierarchical framework's scheduling results are tested within DES to verify robustness under dynamic, large-scale operational conditions.

Key operational parameters include:

• State of Charge (SoC) consumption:

– Empty Haul to Platform 1: 3.0% SoC consumed over 12 minutes (3 km route).

– Empty Haul to Platform 2: 3.75% SoC consumed over 15 minutes (5 km route).

– Loaded Haul from Platform 1: 7.33% SoC consumed over 22 minutes.

– Loaded Haul from Platform 2: 8.33% SoC consumed over 25 minutes.

• Processing times:

– Unloading: 3 min (average) at the crusher.

– Loading: 5 min (average) per excavator.

• Initial fleet state:

– 36 trucks are staged at the unloading zone, simulating a high-demand scenario with synchronized fleet initialization.

Instead of the state-based prediction module (Section 3), DES generates the discrete battery-swapping schedule (Table 2), enumerating feasible time windows while accounting for real-world variability (e.g., traffic, equipment downtime). This DES-derived schedule serves as input to the hierarchical optimization framework (Figure 9), which minimizes queuing delays through proactive demand dispersion.

Figure 12 illustrates the scheduling outcomes generated by the Hierarchical Framework (Section 3) for Case Study 3. The framework converges to a high-quality solution, reducing the total waiting time to 30 minutes by proactively scheduling 100% of trucks for battery swaps prior to SoC depletion during the first operational cycle, demonstrating a 99% reduction compared to the MILP baseline (79.6 minutes) and an 99% improvement over the FCFS strategy (96.0 minutes). It is worth noting that DES yields an average waiting time of 81.3 minutes and 599 total trips completed. It can be inferred that the solution results based on the above hierarchical framework will significantly increase transport trip throughput by the DES.

Figure 12. Case 3: the scheduling results generated by the hierarchical framework, the red markers indicate the battery-swapping moments, the orange markers denote the arrival times of trucks at the station, and the blue markers represent the battery depletion moments (when the battery's State of Charge reaches critical levels).

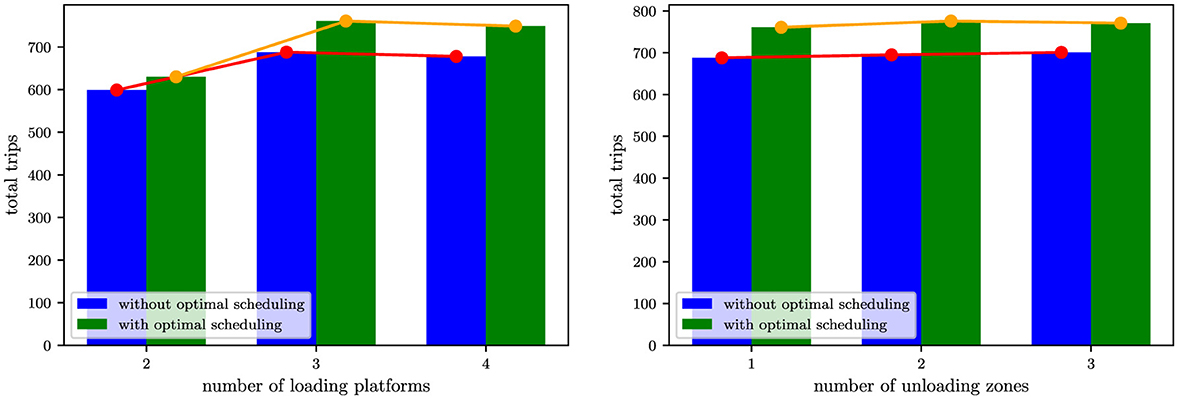

The scheduling solution derived by the Hierarchical Framework (Figure 12, Section 3) is coupled into the Discrete Event Simulation (DES) environment to validate its real-world applicability. Prior to integration, the solution undergoes an operational translation: The framework's time-based battery-swapping assignments (e.g., “swap at 10:15 AM”) are converted into trip-triggered thresholds (e.g., “swap after completing 3 trips”), aligning the proactive scheduling logic with DES's discrete, event-driven architecture. This transformation ensures seamless integration of the hierarchical schedule into DES, enabling rigorous testing of its robustness under dynamic operational variability. The scheduling solution derived by the Hierarchical Framework achieves 630 total transport trips—a 5.2% throughput increase over the DES baseline (599 trips)—while reducing the average battery-swapping wait time to 4.5 min, a 94.5% reduction from the DES benchmark of 81.3 minutes. Figure 13 illustrates the SoC time series with and without the framework's solution, demonstrating near-elimination of prolonged queuing delays during the initial battery-swapping cycle through proactive demand dispersion (Figure 12). The nonlinear scalability of total transport trips—despite the 94.5% reduction in battery-swapping queuing time—highlights that the bottlenecks inherent to open-pit mining operations have changed from battery-swapping to other subsystems (e.g., Truck fleet throughput, Excavator loading rates and Crusher processing capacity). To validate the hypothesis that mechanical subsystems—not battery-swapping efficiency—govern ultimate productivity, we tested the hierarchical framework's scalability by incrementally expanding the number of loading platforms and unloading zones. Figure 14 (left) shows that increasing loading platforms from 2 to 3 elevates total transport trips by 10.6% (from 688 to 761 trips), significantly exceeding the 5.2% gain observed in the dual-platform configuration. This nonlinear scalability confirms that excavator loading capacity (fixed at 5 min per truck) becomes the dominant bottleneck as platforms scale, overriding energy management optimizations. Conversely, Figure 14 (right) reveals marginal diminishing returns when expanding unloading zones: increasing zones from 1 to 2 raises trip gains by only 1.1% (10.6% → 11.7%, 11.7% is obtained by the increment from 695 to 776 trips), with no further improvement when adding a third zone. This plateau—attributable to the crusher's fixed processing capacity (3 min per unload)—demonstrates that unloading zone availability ceases to constrain productivity beyond a critical threshold. While these results clarify the hierarchical framework's role in resolving energy-time bottlenecks (e.g., battery queuing), holistic optimization of mechanical subsystems (e.g., excavator cycle times, crusher throughput) remains an open challenge beyond this study's scope.

Figure 13. SoC time series for all trucks with (left) and without (right) the scheduling solution derived by the Hierarchical Framework coupled into DES.

5 Summary

This paper presents a hierarchical optimization model tailored for off-peak battery-swapping scheduling of electric trucks in open-pit mines, aiming to mitigate queuing inefficiencies caused by synchronized battery depletion. The proposed framework integrates an inner-layer Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) model and an outer-layer Bayesian Optimization (BO) layer. The MILP addresses station-level resource allocation by optimizing battery-swapping assignments and sequencing under capacity constraints, while the BO navigates the combinatorial complexity of scheduling decisions to proactively stagger battery-swapping demand across temporal and spatial dimensions. Through Discrete Event Simulation (DES) and case studies, the authors demonstrate significant reductions in queuing time (up to 94.5%) and improvements in haulage throughput (5.2-10.6%) compared to conventional strategies like First-Come-First-Served (FCFS). The framework effectively resolves synchronization-induced bottlenecks, particularly during initial battery-swapping cycles, by leveraging predictive state-of-charge monitoring and dynamic dispatching. Sensitivity analyses further reveal that optimized scheduling, rather than infrastructure scaling, offers a cost-effective solution for enhancing operational efficiency in resource-constrained environments.

Future research could extend this work by integrating real-time adaptive mechanisms to address dynamic uncertainties such as fluctuating energy demands, traffic disruptions, and equipment downtime. Enhancing the model's scalability for larger fleets or multi-mine networks, coupled with hybrid energy systems incorporating renewables, would broaden its applicability. Additionally, exploring synergies between battery-swapping schedules and mechanical subsystems (e.g., excavator loading rates, crusher throughput) could unlock holistic productivity gains. The integration of digital twins or edge computing for real-time decision-making, alongside lifecycle cost analysis of battery degradation and infrastructure investments, would further refine the framework's economic and environmental viability. Finally, extending the hierarchical model to multi-objective optimization—balancing energy costs, carbon emissions, and workforce safety–could align operational efficiency with broader sustainability goals in the mining sector.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

CM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YT: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. SX: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. XZh: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. XZe: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. LW: Investigation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province, China (Grant Nos. 2024JJ6227, 2024JJ7189, and 2024JJ7197).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Bai, R., Fu, E., Ma, L., Zhao, H., and Chai, S. (2024). Collaborative mining technological system of safety-green-high efficiency-low carbon for open pit coal mine. J. China Coal Soc. 49, 298–308. doi: 10.13225/j.cnki.jccs.2023.1433

Ban, M., Zhang, Z., Li, C., Li, Z., and Liu, Y. (2021). Optimal scheduling for electric vehicle battery swapping-charging system based on nanogrids. Int. J. Elect. Power Energy Syst. 130:106967. doi: 10.1016/j.ijepes.2021.106967

Banks, J., Carson, J. S., Nelson, B. L., and Nicol, D.M. (2013). Discrete-Event System Simulation, 5th Edn. Essex: Pearson Education Limited.

Deng, Y., Chen, Z., Yan, P., and Zhong, R. (2023). Battery swapping and management system design for electric trucks considering battery degradation. Transport. Res. Part D: Transp. Environm. 122:103860. doi: 10.1016/j.trd.2023.103860

GlobalData (2025). Global Electric Mining Truck Market Report. Available online at: https://www.globaldata.com/reportstore/global-electric-mining-truck-market/ (Accessed May 15, 2025).

He, M., Zhou, J., and Nie, D. (2017). “Ga-based resource transportation scheduling optimization of open-pit mine,” in 2017 International Conference on Smart Grid and Electrical Automation (ICSGEA) (Changsha: IEEE), 247–250.

Huang, A., Zhang, Y., He, Z., Hua, G., and Shi, X. (2021). Recharging and transportation scheduling for electric vehicle battery under the swapping mode. Adv. Prod. Eng. Managem. 16, 265–388. doi: 10.14743/apem2021.3.406

Huayanca, D., Bujaco, G., and Delgado, A. (2023). Application of discrete-event simulation for truck fleet estimation at an open-pit copper mine in Peru. Appl. Sci. 13:4093. doi: 10.3390/app13074093

Jordehi, A. R., Javadi, M. S., and Catalo, J. P. S. (2021). Optimal placement of battery swap stations in microgrids with micro pumped hydro storage systems, photovoltaic, wind and geothermal distributed generators. Int. J. Elect. Power Energy Syst. 125:106483. doi: 10.1016/j.ijepes.2020.106483

Lindgren, L., Grauers, A., Ranggd, J., and Mki, R. (2022). Drive-cycle simulations of battery-electric large haul trucks for open-pit mining with electric roads. Energies, 15:4871. doi: 10.3390/en15134871

Sun, Y., Li, Y., Borozan, S., Wang, G., Qiu, J., and Strbac, G. (2024). Battery swapping dispatch for self-sustained highway energy system based on spatiotemporal deep-learning traffic flow prediction. IEEE Trans. Indust. Appl. 60, 1058–1070. doi: 10.1109/TIA.2023.3321713

Teng, S., Li, X., Li, Y., Li, L., Ai, Y., and Chen, L. (2024). Scenario engineering for autonomous transportation: A new stage in open-pit mines. IEEE Trans. Intellig. Vehicl. 9, 4394–4404. doi: 10.1109/TIV.2024.3373495

Vallera, A. M., Nunes, P. M., and Brito, M. C. (2021). Why we need battery swapping technology. Energy Policy 157:112481. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2021.112481

Vigerske S. and Gleixner, A.. (2016). “SCIP: global optimization of mixed-integer nonlinear programs in a branch-and-cut framework,” in Optimization Methods & Software (Abingdon: Taylor & Francis Group), 1–31.

Wang, F. Y., Chen, Z., and Hu, Z. (2024). Comprehensive optimization of electrical heavy-duty truck battery swap stations with a soc-dependent charge scheduling method. Energy, 308:132773. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2024.132773

Wang, S., Chen, A., Wang, P., and Zhuge, C. (2023). Short-term electric vehicle battery swapping demand prediction: deep learning methods. Transport. Res. Part D: Transp. Environm. 119:103746. doi: 10.1016/j.trd.2023.103746

Xiao, Y., Zhou, W., Luan, B., Yang, K., and Yang, Y. (2024). Truck transportation scheduling for a new transport mode of battery-swapping trucks in open-pit mines. Appl. Sci. 14:10185. doi: 10.3390/app142210185

Xu, T., Shi, F., and Liu, W. (2019). “Research on open-pit mine vehicle scheduling problem with approximate dynamic programming,” in 2019 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Cyber Physical Systems (ICPS) (Taipei: IEEE), 571–577.

Yang, X., Yang, B., Wang, Z., Liu, S., Ma, K., Xu, X., et al. (2024). Online optimal scheduling for battery swapping charging systems with partial delivery. Electric Power Syst. Res. 235:110629. doi: 10.1016/j.epsr.2024.110629

Zhan, W., Wang, Z., Zhang, L., Liu, P., Cui, D., and Dorrell, D. G. (2022). A review of siting, sizing, optimal scheduling, and cost-benefit analysis for battery swapping stations. Energy 258:124723. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2022.124723

Zhang, C., Lu, X., Chen, S., Shi, M., Sun, Y., Wang, S., et al. (2024). Synergies of variable renewable energy and electric vehicle battery swapping stations: case study for Beijing. eTransportation 22:100363. doi: 10.1016/j.etran.2024.100363

Zhang X. and Wang, G.. (2016). “Optimal dispatch of electric vehicle batteries between battery swapping stations and charging stations,” in 2016 IEEE Power & Energy Society General Meeting (PESGM) (Boston: IEEE).

Keywords: hierarchical optimization model, off-peak battery swapping scheduling, open-pit mines, electric trucks, discrete event simulation

Citation: Mao C, Tan Y, Xie S, Zhou X, Zeng X and Wang L (2025) A hierarchical optimization model for off-peak battery swapping scheduling of electric trucks in open-pit mines. Front. Comput. Sci. 7:1729185. doi: 10.3389/fcomp.2025.1729185

Received: 21 October 2025; Revised: 14 November 2025; Accepted: 17 November 2025;

Published: 10 December 2025.

Edited by:

Ningyi DAI, University of Macau, ChinaReviewed by:

Jiang Dongchu, Hunan City University, ChinaYufeng Xiao, State Key Laboratory of Coal Resources and Safe Mining, China University of Mining and Technology, China

Copyright © 2025 Mao, Tan, Xie, Zhou, Zeng and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yonghong Tan, dHloMjk3N0BodXNlLmVkdS5jbg==

Chaoli Mao

Chaoli Mao Yonghong Tan*

Yonghong Tan*