- 1Department of Film and Interaction Design, Hongik University, Seoul, Republic of Korea

- 2Department of Visual Communication Design, Hongik University, Seoul, Republic of Korea

Generative AI, with its rapidly developing technologies, has changed how designers look to solve problems relating to the scene’s animation: eliminating inefficiencies, reducing high production costs, and lifting the cognitive load involved in the conception of an animation scene. Therefore, a systematic conceptual design model based on the design of animation scenes, which integrates generative AI tools—ChatGPT and Midjourney—is proposed in this paper. Based on the Co-evolution Model of Design and Divergent-Convergent Thinking, this model enables iterative co-evolution between the problem space and solution space, further provisionally refining a designer’s capacity to explicate goals while exploring various visual solutions effectively. The following is a series of design iterations in which such a model has been applied practically in line with the Research through Design approach. The results thus demonstrated that the proposed framework reduces the cognitive load on designers, increases efficiency, and improves creativity and coherence in the scenes created. Hence, this contributes to AIGen-assisted design-valid methodologies from both theoretical and practical perspectives, appealing to both practitioners and academics with the quick turn of generative AI into creative practice.

1 Introduction

1.1 Research background and significance

Digital technologies and artificial intelligence have developed at an unprecedented speed, changing everything that surrounds them, including animation. The modern audience is no longer satisfied with quality, and the demands for creativity in animated works are going through the roof. Under such conditions, classical methods of animation become inefficient, expensive, and time-consuming to produce and completely unattainable with the current ever-increasing pace of market parameters. Very recently, almost unreal potential has opened up for using generative AI technologies to automate content generation and genuinely elaborate on new optimization possibilities for the conceptual design of animated scenes. On the other hand, considerable progress in applying Generative AI to create animated scenes was evident in the recent past; for instance, Lungu-Stan and Mocanu (2024), proposed a particular deeplearning method for generating 3D character animation and assets based on diffusion models that enable them to generate a coherent high-quality background and animation effects at much greater production efficiency. Hassan et al. (2023) synthesized character-environment interaction. Thus, merged imitation and reinforcement learning techniques allow ambient virtual characters to interact naturally, raising the realism of animated scenes (Lungu-Stan and Mocanu, 2024; Hassan et al., 2023).

In this regard, considering the explosive growth of the animation industry and integrating these results, this paper proposes further exploration of Generative AI technology in conceptual scene design. Indeed, the aim was to reduce the cognitive overload on designers due to recurring dimension shifts in the designs, widen the range of creative divergences, and ensure process efficiency and optimization in design. Hence, the present research holds strong, innovative, and promising values related to the animation industry in developing new, more efficient, and creative ways of designing for animation practitioners and relevant references and insights into related research and practical applications of such integration into animation and other creative industries (As et al., 2018; Camburn et al., 2020).

1.2 Research objectives and methods

This research explores how generative AI tools could improve conceptual designs of animation scenes through an efficient and creative workflow for animators. The study incorporates generative AI at the conceptual design level in an attempt to reduce the cognitive gap created when designers switch frequently from problem space to solution space. This may produce AI-generated visuals that help the designer articulate design intentions and survey a range of creative solutions, adding value to creativity and efficiency in designing animation scenes.

This study employs a Research through Design methodology and introduces the Co-evolution Model of Design integrated with Divergent-Convergent Thinking as a theoretical underpinning to develop a conceptual design process model for animation scenes (Frayling, 1994; Maher et al., 1996; Müller-Wienbergen et al., 2011). This conceptual process model is founded on two core tasks. The first is related to definition, where generative AI enables the designer to interpret a client brief within the conceptual design process of developing an animating scene through convergent thinking. When generating natural artificial intelligence tools such as ChatGPT, one enters the project brief into the system, which then outputs several different keyword sets that can be iteratively refined as user requirements become clearer (Tan, 2023). The second task conceives an animating scene concept through divergent thinking. In this regard, generative tools such as Midjourney explore rapid iterative experiments in which keywords are adjusted and refined to generate vast amounts of conceptual imagery related to animation scene exploration (Tan and Luhrs, 2024). Systematic visual feature analyses will be carried out on the images by the researchers, who will then give refining feedback to iteratively optimize and finish the conceptual design. Consequently, this will empirically design data collection and analysis to empirically test whether the developed process model can prove its effectiveness and pragmatic value in operating an optimized workflow in animating scene conception.

This study involves a model validation experiment and a questionnaire survey with human participants. The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the Hongik University Institutional Review Board (IRB No. [7002340-202506-HR-010-01]). All procedures complied with relevant guidelines and regulations. No animals were involved.

1.3 Contributions of this study

Theoretically and practically speaking, this paper introduces some important contributions in animation and creative designs. It provides a way to further understand and expand present design thought by integrating the Co-evolution Model of Design with the Divergent-Convergent Thinking framework within this new conceptual model structure that still needs further elaboration for conceptual design supported by Generative AI technologies. Secondly, due to this work, empirical proof is given to potent real practical generative uses of AI tools within professional animation work pipelines, which empirical studies have never done to pinpoint such measurements regarding efficiency, clarity, and creativity, so several literature gaps have been closed. Thirdly, the model developed herein should be used practically at an operational level within professional animation studios and by freelance designers to promote access to AI-driven approaches that streamline and facilitate the proliferation of innovation in design processes within the wider creative industries.

2 Literature review

2.1 Core technologies of generative AI applications

Generative AI onwards takes a very fast-than-ever pace with many enabling technologies: Generative Adversarial Networks, Variational Autoencoders, and Diffusion Models. Generative Adversarial Networks are probably the most widely used type of Generative AI. Typically, GANs work through a two-network, adversarial game—namely, a Generator and a Discriminator (Goodfellow et al., 2020). The Generator’s role is to synthesize new data samples, while the Discriminator attempts to classify them as real or fake. After multiple iterations of training, both networks improve, and it is the task of the Generator to construct samples increasingly similar to the true data distribution. To date, there is considerable evidence of the significant potential of GAN technology in such areas as artistic content generation, image style transfer, and visual effects production. Deepfake technologies, character design, and scene generation use it extensively (Karras et al., 2019). The other prominent Generative AI technique is Diffusion Models. These realistic image-making models add noise to the data in an iterative approach that finally denoises the data using a denoising procedure (Ho et al., 2020). One of the most appealing exemplars of the approach is Stable Diffusion, which can create highly realistic and varied images based on a text prompt (Rombach et al., 2022). Recently, strong models like Stable Diffusion and Midjourney have taken the animation, film production, and gaming industries by storm because of their ability to make fast iterations and visualize ideas. In this regard, so far, large language models, viz., ChatGPT series, have outperformed all past attempts at visual generation tasks. Indeed, when generative AI meets natural language processing, designers narrate text descriptions and literally open up complex-yet-realistic pictures and scenes (Radford et al., 2021). On the one hand, this would extend and broaden design workflows; for example, people would be supported in generating high-quality visual drafts without prior drawing training. Simply put, Modern Generative AI is based on three main pillars: GANs, Diffusion Models, and LLMs. These three themes have immense potential in nurturing creativity and high design productivity in the creative industry.

2.2 Application processes of generative AI

Generative AI technologies are widely applied across various design disciplines, forming a typical workflow that includes stages such as needs analysis, creative generation, iterative optimization, and final solution development. In the field of fashion design, designers first state a design theme or style-related keywords, and then they employ Generative AI tools to swiftly create a range of visual concepts, including garment patterns, fabric textures, and style proposals (Yan et al., 2022). For example, Zalando implemented GANs to create highly realistic virtual models with accurate body posture—facilitating superior virtual garment visualization and providing customers with virtual try-on experiences (Bhattacharya et al., 2022). In product design, for instance, it is assumed that Generative AI tools will save time in concept generation, evaluation, and optimization, dramatically improving the efficiency of design innovation and development. Indeed, applications of Generative AI can be found in the conceptual design phase of industrial products, such as automobiles and furniture, to make the design process more effective and flexible (Hou, 2022; Vermeer and Brown, 2022). In contrast to textual prompts, Generative AI tools bring forth diversity in the architectural design process by producing spatial solutions. This gives architects incredible freedom to explore spatial layouts and user experiences in architectural design (Tan and Luke, 2024). With diffusion models like Midjourney, it supports rapid idea iteration and requirement clarification to boost creativity and efficiency for architectural design. In different visual design areas, including brand identity design, visual communication, and advertising creativity, Generative AI tools have found various uses. For instance, when given a text prompt, DALL-E creates a strikingly original image in an instant, helping visual designers navigate their increasingly complicated design space with growing efficiency, enhancing both the diversity and productivity of creative output (Liu et al., 2023).

Traditionally, conceptualizing animation scenes has relied heavily on experience and intuition—usually using hand-drawn or very primitive digital media for visual exploration. This often results in designers shifting frequently between the problem space and the solution space, which might increase cognitive load and lower the efficiency of creative iteration (Singh, 2023). Moreover, due to very high visual standards in animation scene design, conventional tools cannot efficiently explore a wide range of diverse visual concepts, allowing them to be generated quickly (Tang and Chen, 2024). To address these issues, this research proposes that the Generative AI Technologies, along with the Co-evolution Model of Design, the Divergent-Convergent Thinking framework, be embedded in the conceptual design process of animation scenes. In this respect, the designer switches less often between the problem and solution spaces with AI-generated visuals, resulting in greater emphasis on the necessary clarification of design objectives and the exploration of creative alternatives. While generative AI can quickly iterate over a large number of visual concepts, it also reduces cognitive load to the extent that designers can afford to indulge in creative exploration along one dimension, massively enhancing efficiency in animating scene design.

3 Process model design

3.1 Model proposal

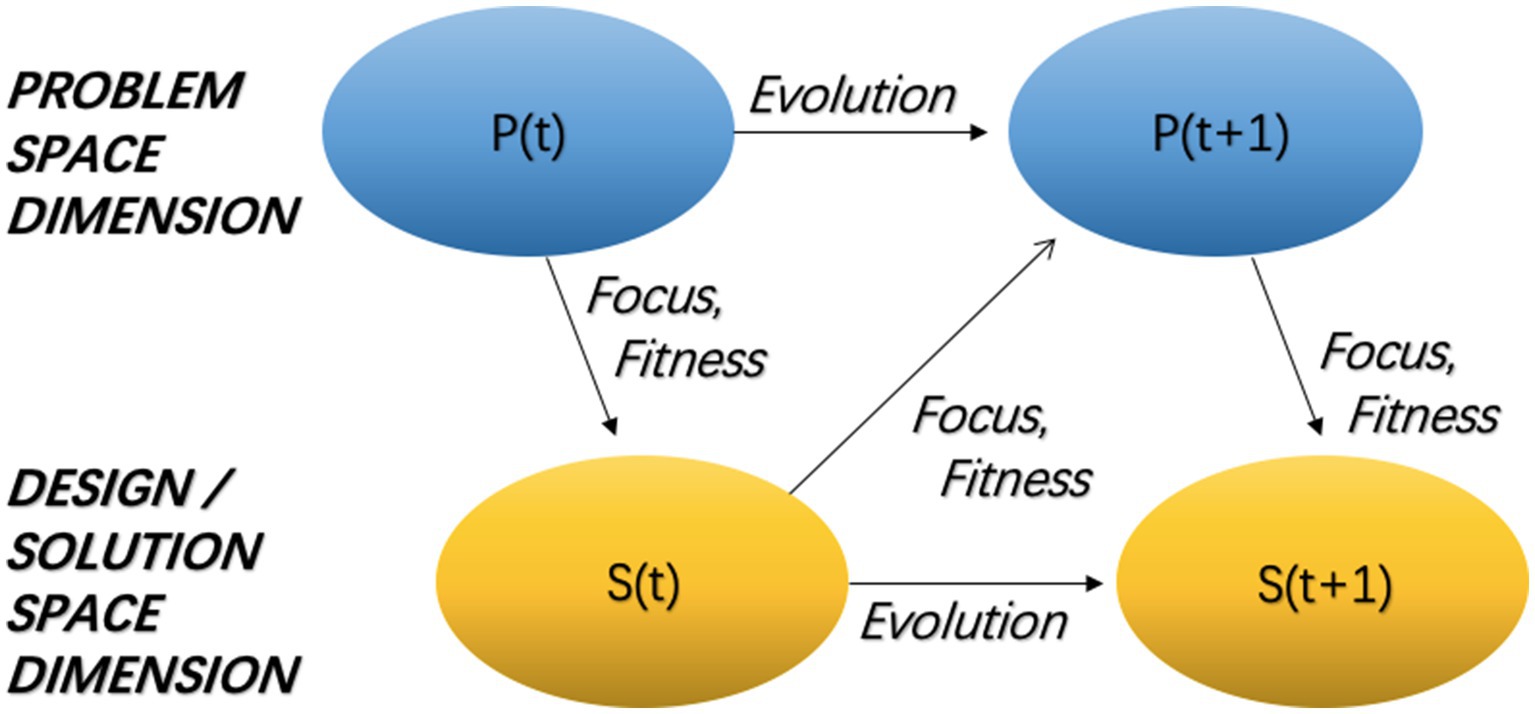

As shown in Figure 1, this embeds Generative AI within the Co-evolution Model of Design and the Divergent-Convergent Thinking Framework and elaborates an optimization process model for conceptual animation scene design wherein the generative AI may handle some of the critical problems in traditional animation scene design, such as a lack of ideas generated, convergent objectives not clarified, and too high a cognitive burden in the designing process. The theoretical character of the present model rests on the studies by Maher et al. (1996) on the Co-evolutionary Model of Design and by Müller-Wienbergen et al. (2011) on the Divergent-Convergent Thinking Framework. As such, the recent development in applying Generative AI in creative architectural design has also been integrated here to give a truly novel combination aiming to design animated scenes.

3.2 Model development

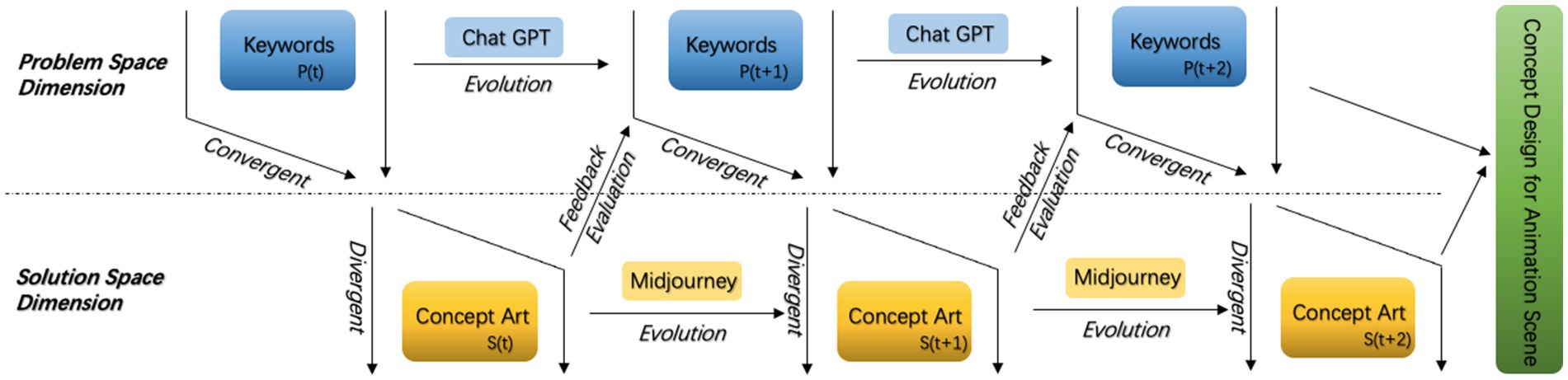

The model comprises two core dimensions: the Problem Space Dimension and the Solution Space Dimension. These dimensions correspond to two critical stages in the design process—convergent thinking (goal clarification) and divergent thinking (solution development). Generative AI tools enable continuous interaction and co-evolution between these two dimensions.

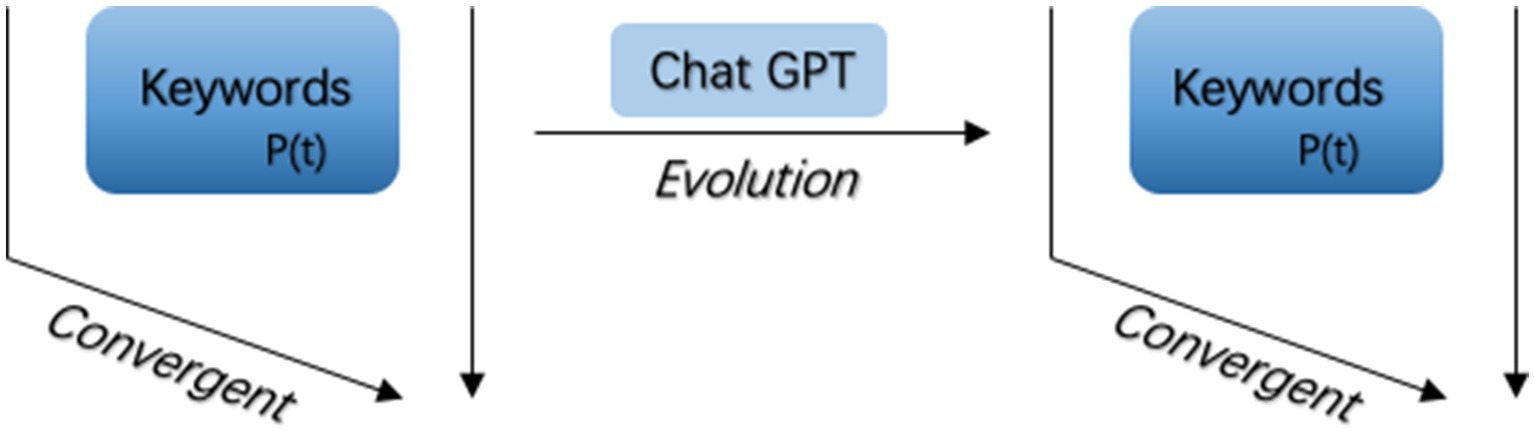

(1) Problem Space Dimension: as shown in Figure 2, this dimension focuses on defining the target audience and core visual requirements of the animation scene, representing the convergent thinking process. The key operations include the concretization of client needs and the confirmation of the design direction. Specifically, through initial communication with clients, designers gather information regarding users’ visual preferences, audience characteristics, and scene requirements. ChatGPT is utilized for natural language processing to refine ambiguous client input into clear, precise, and visually actionable keyword sets. The concept images generated based on these keywords are then subjected to feedback analysis to further clarify the design objectives and scope.

(2) Solution Space Dimension: as shown in Figure 3, this dimension focuses on the rapid visual exploration of design concepts using keywords and represents the divergent thinking process. The key operations include creative generation and iterative refinement of visual solutions. Designers input the keywords generated and consolidated by ChatGPT into Midjourney to quickly produce a large number of preliminary visual concept images, promoting creative divergence. The generated visuals are then evaluated, and feedback is collected to continuously adjust the keywords. ChatGPT is further used to refine the keywords, which are subsequently applied in Midjourney for visual generation. After multiple divergent-convergent iterations, a final animation scene concept design that meets client requirements is determined.

During the model’s operation, the two dimensions are not entirely independent but engage in continuous interaction through co-evolution, where design objectives and design solutions mutually inspire and refine each other in each iteration.

3.3 Model implementation and application

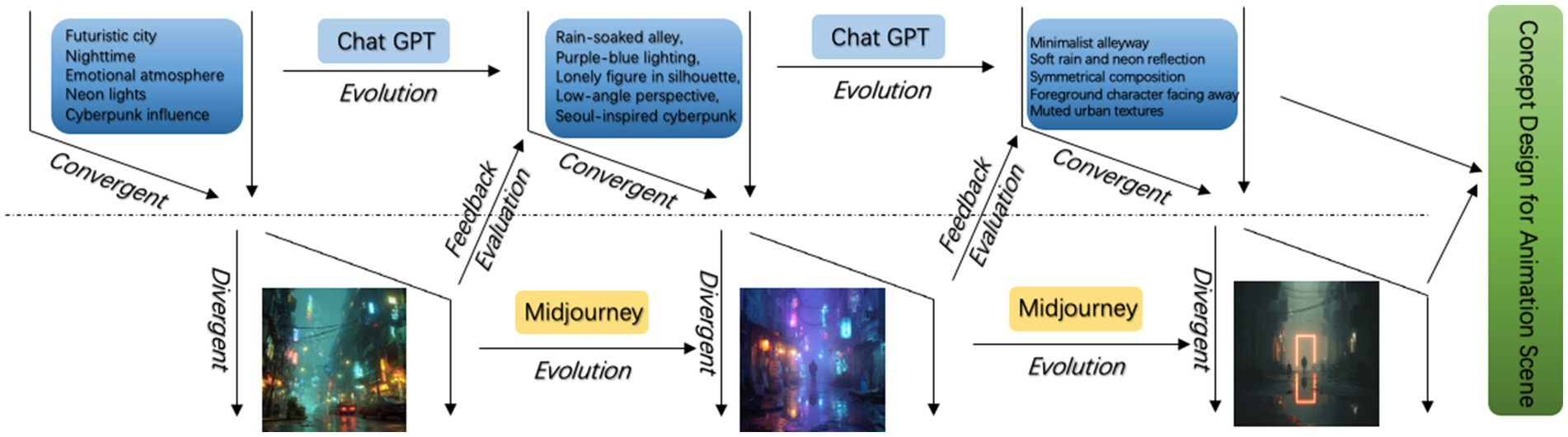

As shown in Figure 4, Goal Clarification Stage: Designers use the Generative AI tool ChatGPT to initially generate keywords for concept images that align with client needs, helping to define clear and specific design objectives. Solution Development Stage: After clarifying the design goal, the designer continues to use Midjourney to batch-generate and explore visual solutions. Feedback and Evaluation stage, ideas and AI-generated concepts go through a Feedback and Evaluation Stage based on determining which represent high-quality designs that potentially meet well all performance requirements. In the Iterative Optimization Stage, it is again subject to this divergent-convergent process, and hence the refining and polishing of the design values go on until no further iterations are warranted.

It will thus take advantage of iterative feedback at all levels and will embed a continuously self-looping design process in interaction with the problem and solution space dimensions. Indeed, this integrated process allows designers to access various design solutions with greater efficiency against well-articulated objectives, thus significantly reducing cognitive load and design time to enhance productive output in concept development of animation scene design. Therefore, it establishes an A-to-Z roadmap for applying AI-enabled technologies in animation scene design, conferring high operability and applicability of methodological support and practical guidance that have currently been envisaged for this sector of the animation creative industry and beyond.

4 Experimental setup

4.1 Experimental methods

This paper attempts to validate via questionnaire the optimization effect of the designed process model over the conceptual animation scene design workflow, resting with conceptualization along the parameter “design process optimization.” It is based on some relevant previous works, and with the help of this, the design of the questionnaire and experiment around the essential concept of design process optimization was developed (Ahmed and Fuge, 2018; Oxman, 2006). A total of 30 participants, including animation scene designers and design managers with more than 2 years of professional experience, were selected from animation studios of various sizes as well as independent designers to ensure the diversity and representativeness of the data. Sampling was done by stratification along two dimensions: studio size (independent; team) and professional roles of participants (animation scene designer; design manager). Inclusion criteria: more than 2 years of professional experience in scene design or design/art management; currently employed or freelanced, having completed at least one project in the prior 12 months. Recruitment: Through studio contacts, professional unions, and designers’ groups.

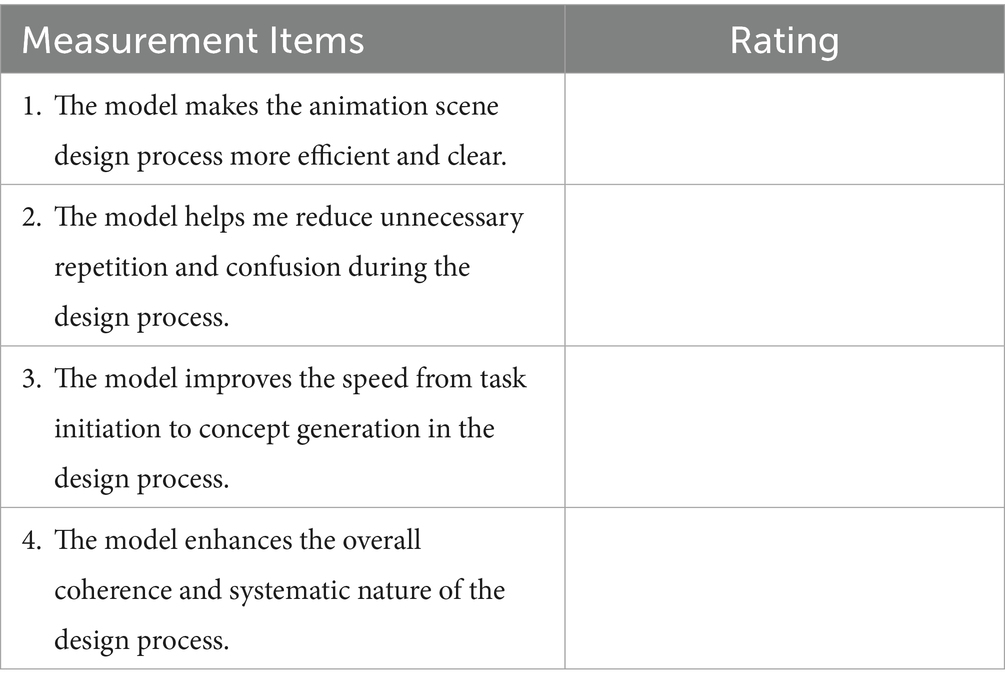

4.2 Questionnaire setup

As shown in Table 1, the questionnaire is designed around a single dimension, “Design Process Optimization,” and consists of the following measurement items. A 5-point Likert scale is applied (1 = Strongly Disagree, 5 = Strongly Agree).

4.3 Data collection and analysis methods

This study distributed questionnaires via an online platform to 30 respondents. All participants completed the questionnaire after applying the model in the conceptual design of animation scenes, providing subjective feedback on their perception of process optimization (Zhu et al., 2017). The response rate reached 100%. All questionnaires were distributed and collected online to ensure efficiency and consistency in data collection. The collected data were analyzed using SPSS software, employing descriptive statistics and One-Sample T-Test to assess participants’ perceptions of “process optimization” after the model’s implementation. Through this experimental setup, the study systematically verifies the model’s practicality and effectiveness in enhancing the conceptual design process of animation scenes, supporting its application in professional practice (Wu et al., 2021).

5 Data analysis

5.1 Descriptive statistics

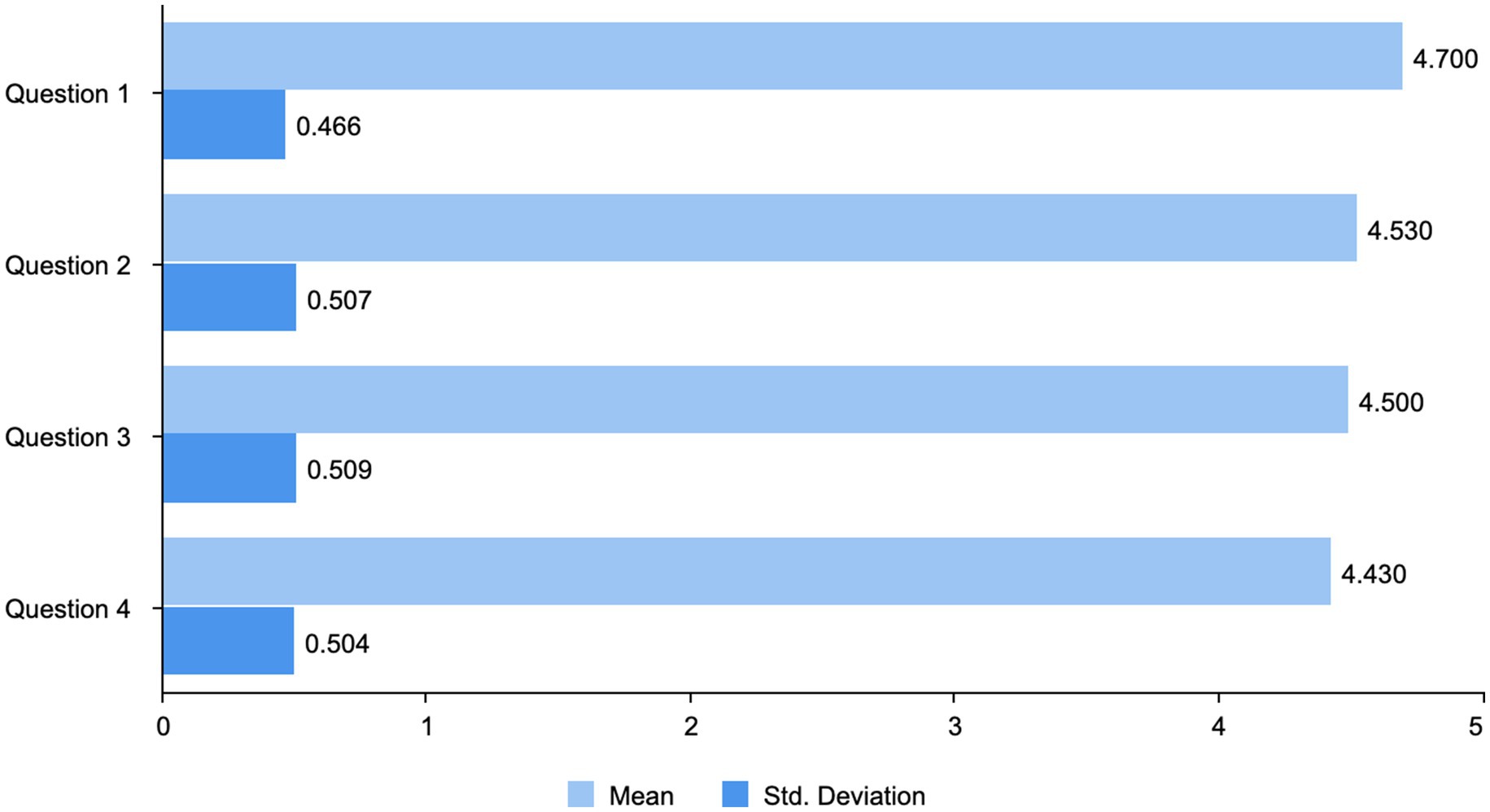

As shown in Figure 5, each item of the questionnaire has been assessed thoroughly; hence, there are certain aspects of the effectiveness of the design model identified. Question 1 (Mean = 4.700): This attained the highest mean score, meaning that respondents perceived the generative AI-enabled model as very effective in achieving clarity and enhancing efficiency within an animation design process. Considering such a low standard deviation (Std. Deviation = 0.466), the data suggest that respondents hardly differ in their perception of the model’s ability to streamline the process and clarify the objectives. Question 2 (Mean = 4.530): The second highest average score was from respondents agreeing that the model strongly eliminates unnecessary duplication and confusion. Modest variation (Std. Deviation = 0.507), shows that experiences differed but not significantly; whatever the difference, the positive effect was too evident for the mean score to reflect it. Question 3 (Mean = 4.500): A high mean score again reflects good agreement that the model will speed up the process from task initiation to concept generation. According to this, respondents would only notice slight productivity changes. Variation (Std. Deviation = 0.509) shows that the model performs evenly across a wide variation of practical situations. Question 4 (Mean = 4.430): Respondents felt that the model would increase integration and systematization in the animation design process. This item obtained the lowest mean score regarding the model’s performance; however, it still attained an absolute score, yet there was slight variance in opinion (Std. Deviation = 0.504), about such a perception because some respondents had adapted less to the structured approach the model provides.

In summary, descriptive statistics generally characterize invariable performance by the generative AI empowered design model in solving various realistic problems related to animation scene design, ranging from proposing efficiency gains to reduced cognitive load, faster concept incubation, and higher coherence of the overall process.

5.2 Reliability analysis

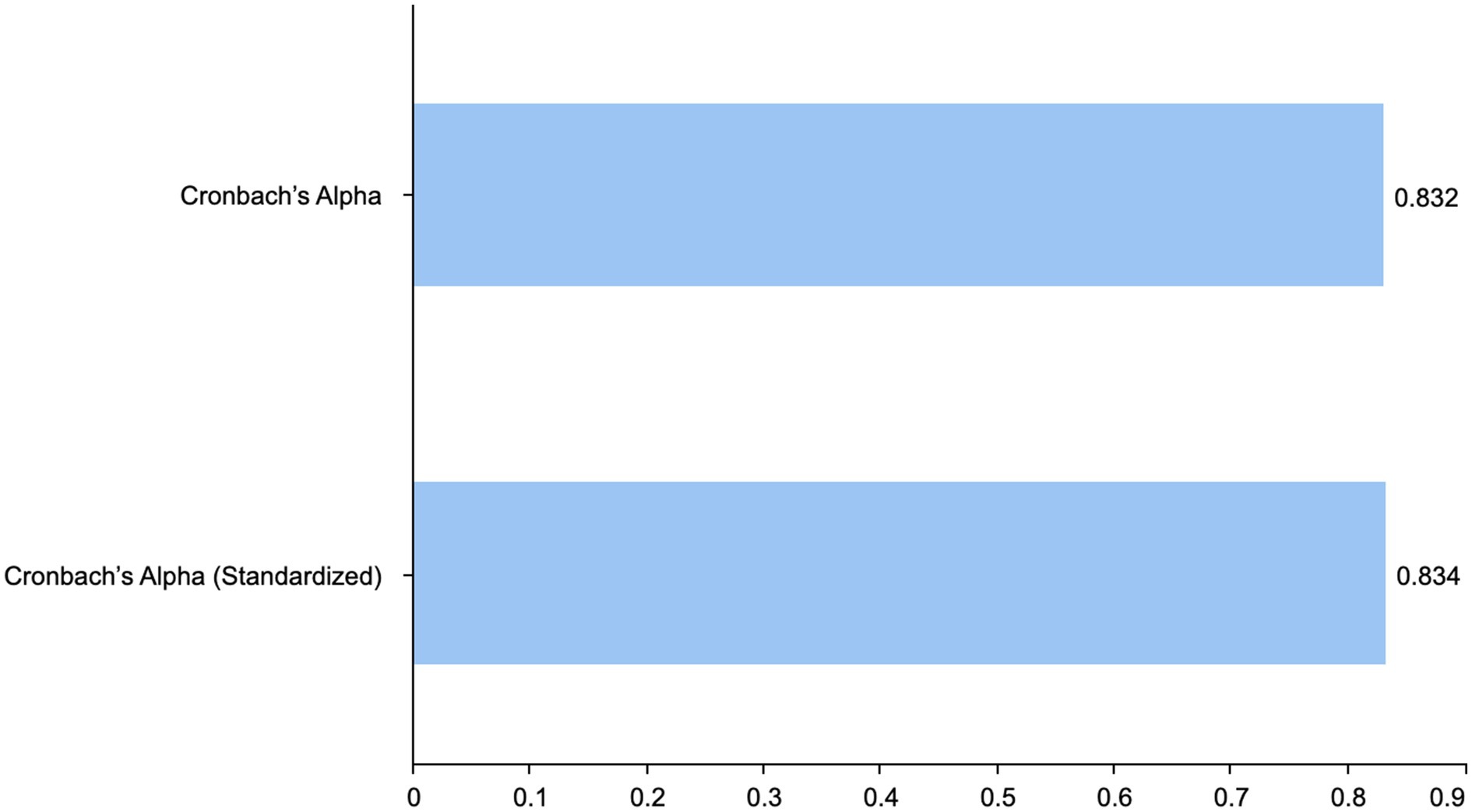

As shown in Figure 6, a reliability analysis was then conducted to determine internal consistency for the four items using Cronbach’s alpha. The result is a very high-reliability coefficient, α = 0.832, non-standardized, α = 0.834. This coefficient exceeds the critical value of 0.80; hence, the items are proven to have strong internal consistency, and the results show adequate validation of the measure for the construct.

Further, inter-item correlations ranged between 0.279 and 0.700, evidencing moderate-to-high inter-item correlations. Generally, all questions had an item-total correlation above 0.49, and no alpha would increase if the item were deleted, indicating the relative contribution of each item to the total reliability.

5.3 One-sample t-test

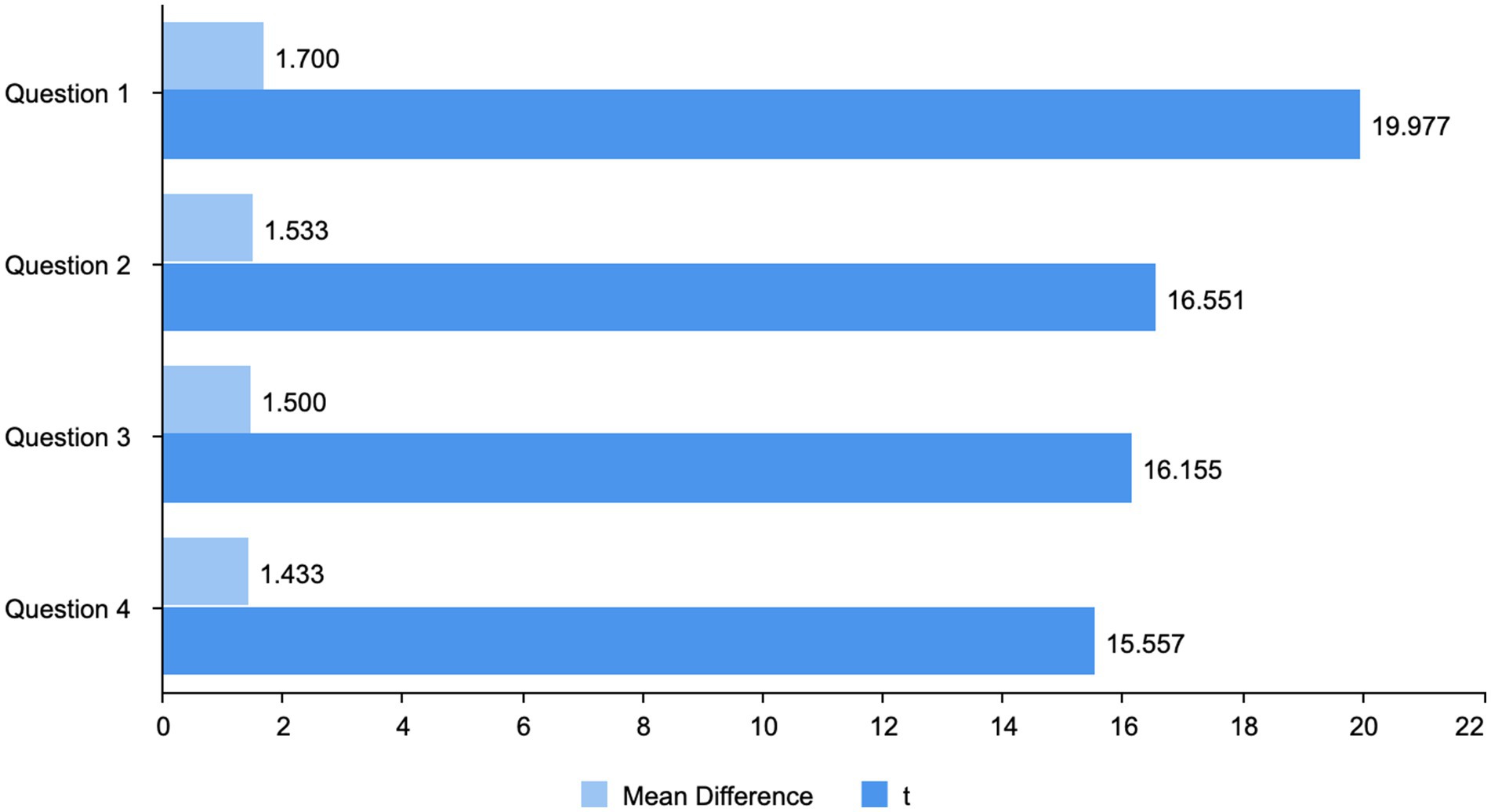

As shown in Figure 7, the results of the one-sample t-tests are more detailed: the model of animation design integrating Generative AI is highly functional. Question 1, with the highest mean difference value (Mean difference = 1.700) and a huge t-value (t = 19.977), shows that the model impacts making clear and makes the workflow efficient to an extent that the degree of consensus among the participants was extremely high. The second question also shows that there was a relatively high degree of agreement among the participants, but the mean difference (Mean difference = 1.533) and the enormous t-value (t = 16.551), again, indicate confirmation regarding the model’s role in preventing many duplications and misunderstandings during the designing process in animation. The third question recorded a mean difference (Mean difference = 1.500) and a good t-value (t = 16.155) accordingly. First, that means first the model will accelerate the generation of concepts and the initial stage of task execution in animation, representing one of the most relevant workflow improvements of practical use in this area. Question Four registered a mean difference (Mean difference = 1.433) and an equally high t-value (t = 15.577), which operationally should be configured as the model increasing the systematic coherency of carrying out the design task. In this respect, this measure is somewhat lower than the others but still significantly higher than the neutral point; again, this supports the generally positive tenor of the items.

Given that, all statistical results strongly support the positive influence of the proposed AI-assisted model on the critical dimensions of animation scene design; thus, its relevance and appropriateness for professional practice are established.

5.4 Effect size

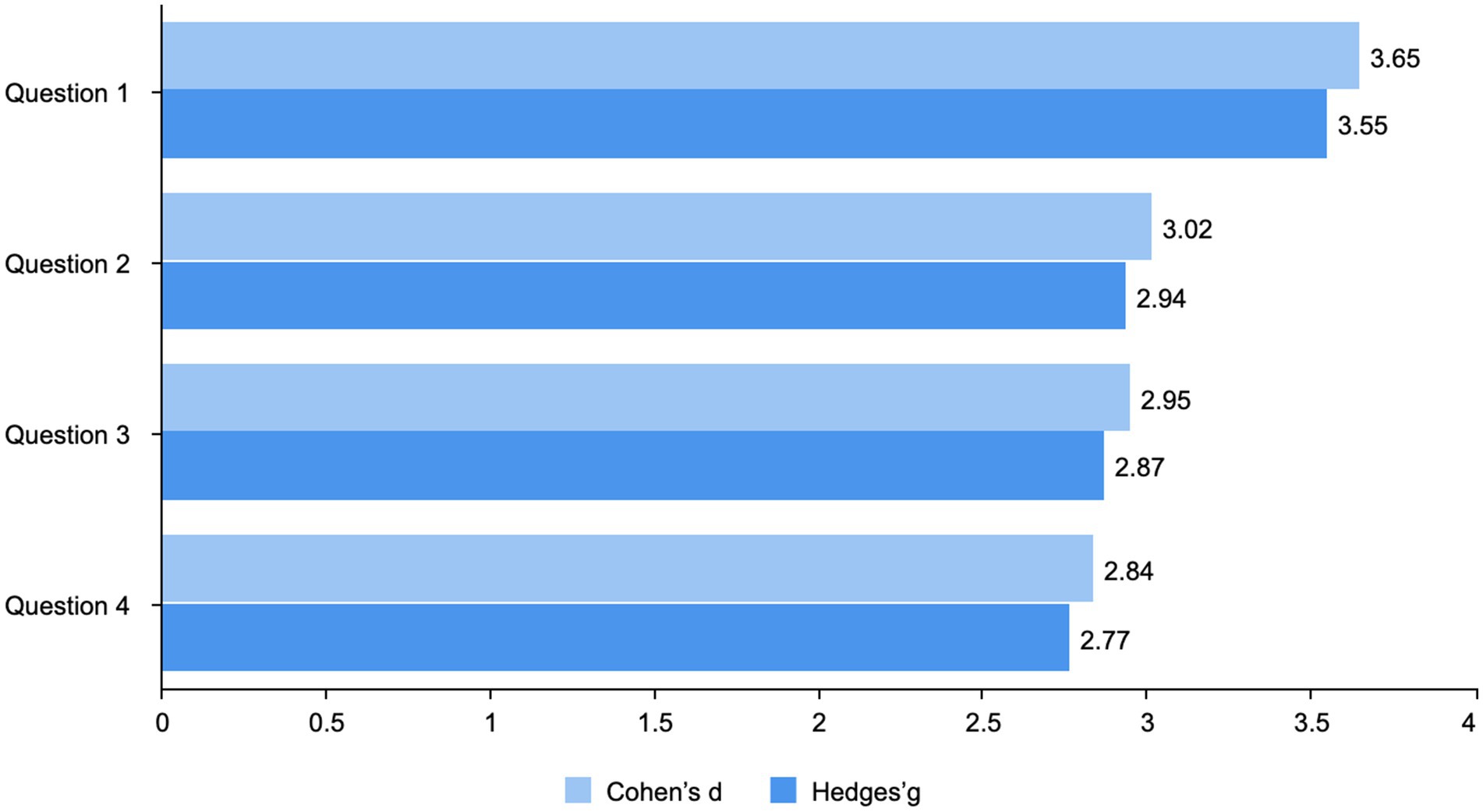

As shown in Figure 8, further probing into the effect sizes showed the practical significance of the findings: for Question 1, the highest effect size (Cohen’s d = 3.65; Hedges’ g = 3.55) exhibited a very considerable effect on improving workflow efficiency and clarity. It was relatively robust for Question 2 (Cohen’s d = 3.02; Hedges’ g = 2.94), indicating a perceptible practical impact on reducing confusion and duplication during the design process. Significant effect sizes were obtained for Question 3 (Cohen’s d = 2.95; Hedges’ g = 2.87), indicating a strong practical impact on speeding up the process of creating animation concepts. Good effect sizes were also observed for Question 4 (Cohen’s d = 2.84; Hedges’ g = 2.77), indicating practical effects on coherence and systematization throughout the workflow of animation design.

However, these previously discussed high effect sizes suggest that a considerable real-world effect will occur if generative AI technology is implemented into the animation design process. Therefore, based on simple statistical evidence, practical relevancy exists.

5.5 Summary

The descriptive results, reliability analysis, and inferential statistics combined show all good evidence for the validity of the proposed model. The tested model was found to be effective in improving efficiency, reducing repetitive designs, speeding up task completions, and adding coherence to animation scene design workflows, with overwhelming agreement from participants. Thereafter, the model was found to be practically valid and able to contribute significantly to AI-assisted animation production.

6 Discussion

6.1 Practical implementation of the model

To demonstrate the practical applicability of the proposed model, an experimental case study was selected to conduct a multi-cycle iterative operation. Each cycle exemplifies the dynamic interplay between the Problem Space Dimension (goal clarification through ChatGPT) and the Solution Space Dimension (visual exploration through Midjourney), guided by iterative feedback.

6.1.1 Initial conceptual expansion

In the initial design brief, the client provided an open-ended request for the creation of a futuristic urban environment intended to evoke strong emotional impact. The description lacks specificity in tone, cultural references, and spatial composition. Utilizing ChatGPT, the design team transforms this ambiguous brief into actionable keywords: Futuristic city, Nighttime, Emotional atmosphere, Neon lights, Cyberpunk influence. These keywords serve as the initial clarified design goals.

The keywords are input into Midjourney, which generates concept art images. While visually compelling, the outputs exhibit a wide stylistic range and inconsistent emotional tones. An internal review of this item finds that although “neon” and “cyberpunk” were visually accented, the emotional intent was ambiguous. Feedback Summary: Overly saturated color palette, Lack of narrative focal point, Ambiguous emotional messaging.

6.1.2 Semantic-visual alignment

In this regard, once more, the design team reaches out to ChatGPT, inputting the feedback they have compiled thus far to fine-tune the keywords regarding emotions, spatial clarity, and cultural relevance. The new keyword set includes: Rain-soaked alley, Purple-blue lighting, Lonely figure in silhouette, Low-angle perspective, Seoul-inspired cyberpunk. This refinement anchors the concept within a specific cultural and emotional framework.

Based on the updated set of prompts, Midjourney produced refined concept visuals for evaluation. The outputs now feature more coherent scene structures and stronger emotional resonance. A melancholic atmosphere emerges, consistent with the client’s goal. Feedback Summary: Improved mood expression, Stronger spatial hierarchy, Minor issues with background clutter and perspective distortion.

6.1.3 Final convergence and optimization

A final round of keyword refinement is conducted through ChatGPT, with emphasis on spatial simplicity and visual clarity. The final keyword set includes: Minimalist alleyway, Soft rain and neon reflection, Symmetrical composition, Foreground character facing away, Muted urban textures. These adjustments aim to resolve previously identified compositional noise and improve narrative focus.

Midjourney generates a final visual set. The resulting images are visually very coherent, with emotionally subtle, narratively promising images. After reviewing with stakeholders, one image is unanimously selected to develop storyboarding and go into production. Feedback Summary: Compositionally balanced, Emotionally expressive, Production-ready quality.

As shown in Figure 9, the three-cycle demonstration illustrates the efficacy of the proposed model in operationalizing the co-evolution of problem definition and visual solution generation. ChatGPT plays a critical role in the convergent clarification of design objectives, while Midjourney supports divergent exploration of visual possibilities. Each feedback-informed iteration enhances both semantic precision and artistic output.

The closed feedback loop continually realigns it with client needs, significantly reducing cognitive load and creative ambiguity. The model thereby increases both creative productivity and the quality of design, laying down a methodological grounding for AI-integrated workflows not only in animation but also in many adjacent fields.

6.2 Results overview

This study systematically validated a Generative AI-assisted conceptual design model for animation scenes, employing established theoretical frameworks, including the Co-evolution Model of Design and the Divergent-Convergent Thinking methodology. Empirical results from 30 professional animation designers and managers demonstrated significant improvements in efficiency, clarity, concept generation speed, and overall coherence within the design workflow. Statistical testing proved high reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.832) and substantial practical effect: mean scores were significantly above the neutral value (p < 0.001) with large effect sizes (Cohen’s d from 2.84 to 3.65). Particularly, it emphasizes the model’s capacity to minimize cognitive load and widen creative exploration, thus confirming the model’s practical use and user acceptance.

6.3 Model analysis

The model fills the gap in shortcomings inherent in traditional animation design processes, such as high cognitive load for the designer and the elongation of eliciting iterative visual concepts. Generative AI tools quickly clarify objectives and allow designers to diverge creatively (Simeone et al., 2022). At the same time, a two-step systematic approach towards convergent goal clarification immediately leads to stimulating productive divergent concept generation without being too systematic on the designer’s part. The statistical base thus yields strong evidence of practical effectiveness, undoubtedly having implications for the professional context and possible extensions to other creative domains (Serra and Miralles, 2021). Therefore, it has immense potential for fostering neo-paradigm efficiency and innovation in animation and related creative industries.

6.4 Limitations and future directions

However, some caveats for generalization apply regarding the small sample size and industry context. Thus, experiential conditions will be somewhat different from the experimental conditions for practical purposes when working within a design studio on a day-to-day basis (Dzieduszyński, 2022). Still, the early concept-expansion phase’s twin failures arose in unclear emotional expression blown affective meaning, paving the way for further elaborations on socioemotional evaluation methods for the following versions of these methods (Bamicha and Drigas, 2023). During this study, only immediate optimization process implications were focused on, so long-term sustainability or continuous adaptations of this model for evolving technological contexts were not on the agenda. Future research can bring greater participant diversity and a long-term impact study of integrating generative AI. Following this, it will be possible to discuss the scalability of the model across various creative industries and broader design contexts (Seneviratne et al., 2022). In this regard, the explicit affective-social understanding layer, from beliefs, desires, and intentions to emotional states about users, metacognitive self-monitoring and self-explanation for error checking and correction, should be considered so that users’ requests are responded to and further developed on a socioemotional level (Bamicha and Drigas, 2024). Second, the study can be expanded with additional longitudinal studies and qualitative feedback regarding user interactions with generative AI in varied professional contexts. Third, further studies involving diverse AI tools and techniques, including user-centered iterative refinements, would further enhance the proposed model’s practical applicability and long-term viability.

Real-life applications of generative AI call for scalable co-creative pipelines that seamlessly communicate visual, semantic, and emotional layers to ensure affect-aligned outputs and standardized workflows in scaleable human–AI design processes (Lyu et al., 2022). Indeed, to be relevant beyond gains on a pilot basis, such implementations must undergo longitudinal evaluations across contexts experienced by different designers, thus reducing risks such as design fixation through designer-driven embedding and clear partitioning of roles (Wang et al., 2025). Prompt literacy is thus the foundational requisite, as such training may improve creative problem-solving and human agency in co-construction more specifically (Hwang and Lee, 2025). More immediate are studio-based curricular implementations that would investigate relative engagement and performance against traditional pedagogies, developing a normative case for this scalable adoption (Tang et al., 2022). At the same time, many multimodal generative methods will specify, afford, and intelligently feedback on animation for teaching and production workflows in the near future, a case in point from (Yao et al., 2025).

7 Conclusion

Drawing on solid theoretical underpinnings, this study has made many contributions, from addressing key inefficiencies in time-honored animation design methods to establishing a sound, user-validated framework that systematically supports iterative creative workflows. From fostering vast creative explorations, reducing cognitive load, enhancing iterative feedback loops, the model shows potential to revolutionize animation scene conceptual design practices.

In closing, this study proves that the proposed Generative AI-assisted conceptual design model developed within this research, considerably improves traditional animation scene design process concerning efficiency, clarity, speed, and total coherence. Empirical evidence, coupled with large effect sizes and high internal consistency, underscores the model’s robust effectiveness and practical applicability. Despite the need for broader validation in diverse contexts, this work offers a solid foundation for leveraging Generative AI to systematically optimize creative workflows in animation and related fields.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Hongik University Institutional Review Board (IRB No. 7002340-202506-HR-010-01). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

JP: Investigation, Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft. HK: Resources, Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. NW: Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Validation, Formal analysis. JW: Visualization, Writing – review & editing, Software.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all study participants for their valuable contributions. Institutional support from Hongik University is gratefully acknowledged. We are indebted to Professor Hyunsuk Kim for sustained guidance and critical feedback throughout the research.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomp.2025.1741768/full#supplementary-material

References

Ahmed, F., and Fuge, M. (2018). Ranking ideas for diversity and quality. J. Mech. Des. 140:011101. doi: 10.1115/1.4038070

As, I., Pal, S., and Basu, P. (2018). Artificial intelligence in architecture: generating conceptual design via deep learning. Int. J. Archit. Comput. 16, 306–327. doi: 10.1177/1478077118800982

Bamicha, V., and Drigas, A. (2023). Consciousness influences in ToM and metacognition functioning-an artificial intelligence perspective. Res. Soc. Dev. 12, e13012340420–e13012340420. doi: 10.33448/rsd-v12i3.40420

Bamicha, V., and Drigas, A. (2024). Strengthening AI via ToM and MC dimensions. Sci. Elect. Arch. 17:1939. doi: 10.36560/17320241939

Bhattacharya, G., Abraham, K., Kilari, N., Lakshmi, V. B., and Gubbi, J. (2022). “Far-Gan: color-controlled fashion apparel regeneration.” In 2022 IEEE International Conference on Signal Processing and Communications (SPCOM). pp. 1–5. IEEE.

Camburn, B., Arlitt, R., Anderson, D., Sanaei, R., Raviselam, S., Jensen, D., et al. (2020). Computer-aided mind map generation via crowdsourcing and machine learning. Res. Eng. Des. 31, 383–409. doi: 10.1007/s00163-020-00341-w

Dzieduszyński, T. (2022). Machine learning and complex compositional principles in architecture: application of convolu-tional neural networks for generation of context-dependent spatial compositions. Int. J. Archit. Comput. 20, 196–215. doi: 10.1177/14780771211066877

Frayling, C. (1994). Research in art and design (Royal College of art research papers, vol 1, no 1, 1993/4)

Goodfellow, I., Pouget-Abadie, J., Mirza, M., Xu, B., Warde-Farley, D., Ozair, S., et al. (2020). Generative adversarial networks. Commun. ACM 63, 139–144. doi: 10.1145/3422622

Hassan, M., Guo, Y., Wang, T., Black, M., Fidler, S., and Peng, X. B. (2023). “Synthesizing physical character-scene interac-tions.” In ACM SIGGRAPH 2023 Conference Proceedings. pp. 1–9.

Ho, J., Jain, A., and Abbeel, P. (2020). Denoising diffusion probabilistic models. Adv. Neural Inf. Proces. Syst. 33, 6840–6851. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2006.11239

Hou, C. (2022). Application of artificial intelligence technology in smart car design. Highlights Sci. Eng. Technol. 15, 322–325. doi: 10.54097/hset.v15i.3006

Hwang, Y., and Lee, J. H. (2025). Exploring students’ experiences and perceptions of human-AI collaboration in digital content making. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 22:44. doi: 10.1186/s41239-025-00542-0

Karras, T., Laine, S., and Aila, T. (2019). “A style-based generator architecture for generative adversarial networks.” in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. pp. 4401–4410.

Liu, V., Vermeulen, J., Fitzmaurice, G., and Matejka, J. (2023). “3DALL-E: integrating text-to-image AI in 3D design work-flows.” in Proceedings of the 2023 ACM designing interactive systems conference. pp. 1955–1977.

Lungu-Stan, V. C., and Mocanu, I. G. (2024). 3D character animation and asset generation using deep learning. Appl. Sci. 14:7234. doi: 10.3390/app14167234

Lyu, Y., Wang, X., Lin, R., and Wu, J. (2022). Communication in human–AI co-creation: perceptual analysis of paintings generated by text-to-image system. Appl. Sci. 12:11312. doi: 10.3390/app122211312

Maher, M. L., Poon, J., and Boulanger, S. (1996). Formalising design exploration as co-evolution: a combined gene approach Advances in formal design methods for CAD: Proceedings of the IFIP WG5. 2 workshop on formal design methods for computer-aided design, June 1995 3 30 Boston, MA Springer US.

Müller-Wienbergen, F., Müller, O., Seidel, S., and Becker, J. (2011). Leaving the beaten tracks in creative work–a design theory for systems that support convergent and divergent thinking. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 12:2. doi: 10.17705/1jais.00280

Oxman, R. (2006). Theory and design in the first digital age. Des. Stud. 27, 229–265. doi: 10.1016/j.destud.2005.11.002

Radford, A., Kim, J. W., Hallacy, C., Ramesh, A., Goh, G., Agarwal, S., et al. (2021). “Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision.” In International conference on machine learning pp. 8748–8763. PmLR.

Rombach, R., Blattmann, A., Lorenz, D., Esser, P., and Ommer, B. (2022). “High-resolution image synthesis with latent diffusion models.” in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. pp. 10684–10695.

Seneviratne, S., Senanayake, D., Rasnayaka, S., Vidanaarachchi, R., and Thompson, J. (2022). “DALLE-URBAN: capturing the URBAN design expertise of large text to image transformers.” in 2022 International Conference on Digital Image Computing: Techniques and Applications (DICTA). pp. 1–9. IEEE.

Serra, G., and Miralles, D. (2021). Human-level design proposals by an artificial agent in multiple scenarios. Des. Stud. 76:101029. doi: 10.1016/j.destud.2021.101029

Simeone, L., Mantelli, R., and Adamo, A. (2022). Pushing divergence and promoting convergence in a speculative design pro-cess: Considerations on the role of AI as a co-creation partner.

Singh, A. (2023). “Future of animated narrative and the effects of AI on conventional animation techniques.” in 2023 7th International Conference on Computation System and Information Technology for Sustainable Solutions (CSITSS). pp. 1–4. IEEE.

Tan, L. (2023). “Using textual GenAI (ChatGPT) to extract design concepts from stories.” in The 7th International Conference for Design Education Researchers.

Tan, L., and Luhrs, M. (2024). Using generative AI Midjourney to enhance divergent and convergent thinking in an architect’s creative design process. Des. J. 27, 677–699. doi: 10.1080/14606925.2024.2353479

Tan, L. I. N. U. S., and Luke, T. H. O. M. (2024). “Accelerating future scenario development for concept design with text-based GenAI (ChatGPT).” in Proceedings of the 29th CAADRIA Conference. pp. 39–48.

Tang, M., and Chen, Y. (2024). AI and animated character design: efficiency, creativity, interactivity. Front. Soc. Sci. Technol. 6, 117–123. doi: 10.25236/FSST.2024.060120

Tang, T., Li, P., and Tang, Q. (2022). New strategies and practices of design education under the background of artificial intelligence technology: online animation design studio. Front. Psychol. 13:767295. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.767295,

Vermeer, N., and Brown, A. R. (2022). “Generating novel furniture with machine learning.” in International Conference on Computational Intelligence in Music, Sound, Art and Design (Part of EvoStar). pp. 401–416. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Wang, N., Kim, H., Peng, J., and Wang, J. (2025). Exploring creativity in human–AI co-creation: a comparative study across design experience. Front. Comput. Sci. 7:1672735. doi: 10.3389/fcomp.2025.1672735

Wu, Z., Ji, D., Yu, K., Zeng, X., Wu, D., and Shidujaman, M. (2021). “AI creativity and the human-AI co-creation model.” in International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction. pp. 171–190. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Yan, H., Zhang, H., Liu, L., Zhou, D., Xu, X., Zhang, Z., et al. (2022). Toward intelligent design: an AI-based fashion de-signer using generative adversarial networks aided by sketch and rendering generators. IEEE Trans. Multimedia 25, 2323–2338. doi: 10.1109/TMM.2022.3146010

Yao, X., Zhong, Y., and Cao, W. (2025). The analysis of generative artificial intelligence technology for innovative thinking and strategies in animation teaching. Sci. Rep. 15:18618. doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-03805-y,

Keywords: animation scene design, concept development, design efficiency, generative AI, visual creativity, workflow optimization

Citation: Peng J, Kim H, Wang N and Wang J (2025) Optimizing the conceptual design process of animation scenes using generative AI. Front. Comput. Sci. 7:1741768. doi: 10.3389/fcomp.2025.1741768

Edited by:

Athanasios Drigas, National Centre of Scientific Research Demokritos, GreeceReviewed by:

Viktoriya Galitskaya, National Centre of Scientific Research Demokritos, GreeceVictoria Bamicha, National Centre of Scientific Research Demokritos, Greece

Copyright © 2025 Peng, Kim, Wang and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hyunsuk Kim, a3lsZWtpbUBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Junfeng Peng

Junfeng Peng Hyunsuk Kim

Hyunsuk Kim Nan Wang

Nan Wang Jiayi Wang

Jiayi Wang