- 1Department of Genetics, University of Pennsylvania, Philadephia, PA, United States

- 2School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadephia, PA, United States

- 3Department of Medicine, Divison of Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Metabolism, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, United States

Introduction: Leptin inhibits insulin secretion from isolated islets from multiple species, but the cell type that mediates this process remains elusive. Several mouse models have been used to explore this question. Ablation of the leptin receptor (Lepr) throughout the pancreatic epithelium results in altered glucose homeostasis and ex vivo insulin secretion and Ca2+ dynamics. However, Lepr removal from neither alpha nor beta cells mimics this result. Moreover, scRNAseq data has revealed an enrichment of LEPR in human islet delta cells.

Methods: We confirmed LEPR upregulation in human delta cells by performing RNAseq on fixed, sorted beta and delta cells. We then used a mouse model to test whether delta cells mediate the diminished glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in response to leptin.

Results: Ablation of Lepr within mouse delta cells did not change glucose homeostasis or insulin secretion, whether mice were fed a chow or high-fat diet. We further show, using a publicly available scRNAseq dataset, that islet cells expressing Lepr lie within endothelial cell clusters.

Conclusions: In mice, leptin does not influence beta-cell function through delta cells.

Introduction

Leptin, a hormone secreted by adipose tissue, impairs hunger and promotes energy expenditure by activating its cognate receptor (1). It exerts these effects primarily through the hypothalamus (2, 3). The human and mouse leptin receptor exists in six isoforms resulting from alternative LEPR gene splicing (4). These receptors are referred to as LepRa-f. The full-length receptor, LepRb, has a strong signal in response to leptin binding. However, the short isoforms, LepRa-c and LepRf, lack varying lengths of the intracellular domain and demonstrate a weak signaling response to leptin binding (4). The short isoforms also aid in transporting leptin across the blood-brain barrier and may promote leptin internalization and degradation in some cell types (5). Leprdb/db mice become obese and, on some background strains, exhibit diabetes. Leprdb/db mice have a mutation within the Lepr gene that results in exon usage only for short LepR isoforms and not LepRb (6). This mutation phenocopies that of mice with a mutation in leptin, indicating the relative importance of the signaling capacity of the short versus long isoforms (6, 7). LepRe, known as soluble leptin receptor, is a secreted isoform lacking the transmembrane and intracellular domains. It can bind circulating leptin, thereby preventing its transport and decreasing bioavailability (8, 9).

Leptin receptor signaling acts through a variety of pathways. Leptin binding of the short or long LepR isoforms can trigger the Jak signaling cascade (4). In contrast, Signal Transducer and Activation of Transcript (STAT) protein signaling can only be activated by the full-length LepRb.

In addition to its hypothalamic localization, the leptin receptor (LEPR) is also expressed in immune cells, pericytes, and endothelial cells, affecting various immune processes and vessel constriction (4, 10). LepRb has also been detected by RT-PCR and Northern blot in islets, and multiple labs have reported that leptin directly inhibits insulin secretion from isolated mouse, human, and rat islets (11–17). Moreover, deletion of the leptin receptor (Lepr) throughout the pancreatic epithelium using Pdx1-Cre alters glucose homeostasis (18). Pdx1-Cre;Leprfl/fl mice fed a normal chow diet display improved glucose tolerance, while those provided a high-fat diet display glucose intolerance (18). Since leptin inhibits insulin secretion, deleting Lepr would be expected to promote insulin secretion, as observed on a normal chow diet. Perhaps this increased insulin secretion in times of high metabolic demand, such as when on a high-fat diet, leads to beta-cell exhaustion and thus the glucose tolerance observed in high-fat-diet-fed Pdx1-Cre;Leprfl/fl mice.

While the altered glucose homeostasis in Pdx1-Cre;Leprfl/f suggests that the cell responsible for this phenotype has an epithelial origin, narrowing down the exact cell type has proven difficult. Two different models of Lepr deletion within beta cells have yielded conflicting results. Rat insulin promoter (RIP25Mgn)-Cre;Lepr mice display hyperglycemia and reduced insulin secretion, but they also have high adiposity due to RIP-CreMgn activity in the brain (19, 20); the disrupted glucose homeostasis is likely a secondary effect to obesity associated with loss of Lepr in the hypothalamus. A second model of beta-cell Lepr ablation using Insulin 1 (Ins1)-Cre results in only a slight change in blood glucose regulation, with females at eight weeks of age exhibiting slightly improved glucose tolerance and enhanced glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (21). These changes disappeared by sixteen weeks of age. In addition, alpha-cell ablation of Lepr using either Glucagon (Gcg)-Cre or Gcg-CreER did not lead to altered glycemia (21, 22).

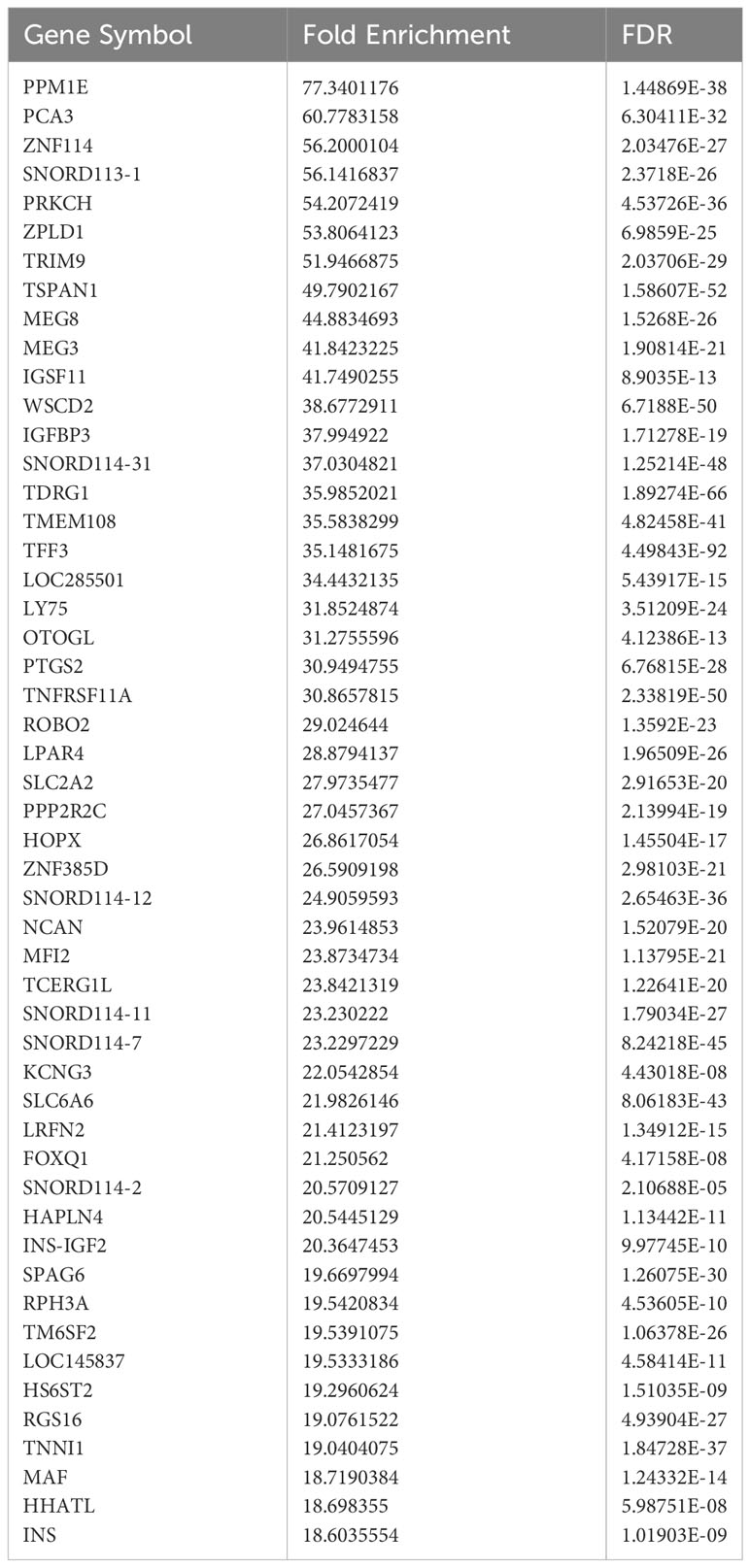

Another primary islet endocrine cell type is the somatostatin-secreting delta cell. Somatostatin is a paracrine hormone that inhibits adjacent secreting cells. Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNAseq) of human islets has revealed that LEPR is enriched within delta cells (23). Leptin signaling is generally inhibitory for secretory cells since the Jak cascade through phosphoinositide 3 kinase and phosphodiesterase 3B ultimately converts cAMP into AMP (24). However, LepR signaling through Jak or STAT can activate PKC (25, 26). In multiple cell types, including beta cells and heart cells, some PKC isoforms enhance Ca2+ influx and insulin secretion (27, 28). Delta cells are glucose-responsive (29). In addition to expressing all the machinery for insulin secretion, except insulin itself, they also integrate several paracrine signals, such as GLP-1 and Urocortin 3, which elevate cAMP levels, and electrical signals from beta-cell through gap junctions (16, 30–33) (Figure 1A). Although cAMP likely has a more prominent role in regulating delta-cell than beta-cell function, delta-cell Ca2+ concentration is correlated with somatostatin secretion (29, 35). Considering these data, we proposed that leptin acts on delta cells by stimulating PKC, elevating Ca2+ and somatostatin release, thereby inhibiting beta cells (Figure 1A). We tested this premise in a mouse model of delta-cell-specific Lepr ablation.

Figure 1 Testing whether leptin mediates inhibition of insulin secretion through the delta cell. (A) RNAseq of sorted mouse alpha, beta, and delta cells has revealed the expression of all the components involved in canonical and amplifying pathways of insulin secretion, except insulin itself, in the delta cell. These components include a glucose transporter, voltage-gated potassium channels, glucokinase, and adenylate cyclase. Delta cells are also regulated by paracrine interactions by other endocrine cells, including by Urocortin 3 and by GLP1 (30–34). Although cytosolic Ca2+ may be secondary to cAMP in regulating delta-cell function, Ca2+ concentration correlates with somatostatin secretion. In human islets, the leptin receptor is enriched within the delta cell population. We, therefore, hypothesized that leptin receptor signaling enhances SST release by activating a PKC isoform that enhances CaΔv activity and increases intracellular Ca2+ (pathway denoted by black arrows). Proposed leptin receptor signaling is shown with black arrows while established signaling pathways in the delta cell are depicted with grey arrows. (B) Mouse model: SstrtTA;Tet-O-Cre;Leprfl/fl (LeprΔδ) and littermate control mice were placed on doxycycline from eight weeks to ten weeks of age. Mice were assigned to a high-fat or normal chow diet at ten weeks of age. GTTs were performed at eight, 14, and 36 weeks of age, corresponding to before dox treatment, and four and 26 weeks after doxycycline cessation.

Materials and methods

Mice

Sst-rtTA (36), Tet-O-Cre (37), and Leprfl/fl (38) mice and genotyping have been described previously. 2% doxycycline in water was administered at eight weeks of age for two weeks. Mice were fed chow or 60% HFD (Research Diets) ad libitum and maintained on a 12-hour light/dark cycle. Control mice were littermates of mutants, had one allele of SstrtTA, and included SstrtTA;Tet-O-Cre;Lepr+/fl and SstrtTA;Leprfl/fl mice. All procedures followed the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines at the University of Pennsylvania or Johns Hopkins University.

Glucose tolerance tests, mouse islet isolations, and perifusions

For glucose tolerance tests (GTTs), mice were fasted overnight for 16 hours, and blood glucose was measured with an AlphaTRAK glucometer. Mice were injected intraperitoneally with 1g/kg or 2g/kg glucose in sterile 1X PBS; blood glucose was measured 15, 30, 60, 90, and 120 minutes after injection. Islets were isolated by collagenase digestion followed by Ficoll separation and hand-picking, as previously described (39). Perifusions were performed by the University of Pennsylvania Pancreatic Islet Cell Biology Core.

Immunofluorescence and immunohistochemistry

Pancreata were fixed in 4% PFA for 4 hours, rinsed in 1X PBS, and embedded in paraffin. 4-micron sections were attached to PermaFrostPlus slides. For beta-cell mass assessments, five sections spread throughout the pancreas were immunolabeled with guinea pig-anti-insulin (DAKO) and a secondary biotinylated anti-guinea pig antibody. HRP was bound to the antibody with an ABC kit (Vector Laboratories) and visualized with DAB (Vector Laboratories). Slides were counterstained with eosin. Imaging was performed with an Aperio microscope at 400X. DAB- and eosin-positive areas were quantified using QuPath (40). The DAB-to-eosin ratio was multiplied by pancreas weight to obtain beta-cell mass. For immunofluorescence, the primary antibodies guinea pig-anti-insulin (1:500, DAKO), mouse anti-SST (1:250, Santa Cruz), and rabbit anti-glucagon (1:500, Santa Cruz) were used. Secondary antibodies (Jackson Immunolaboratories) were applied at 1:600. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Images were acquired using a BZ-X Series All-in-One Fluorescence Microscope.

Recombination analysis

One to four paraffin-embedded pancreatic sections were scraped with a clean razor into a sterile microcentrifuge tube and digested overnight with 100 microliters of Proteinase K solution before standard PCR, using 1-10 microliters of heat-inactivated digested sections. Primers for recombination analysis were previously described (41).

qPCR

Primers (Lepr F 5’-GTT TCA CCA AAG ATG CTA TCG AC-3’; Lepr R 5’GAG CAG TAG GAC ACA AGA GG-3’) for Lepr were tested on hypothalamus cDNA before analyzing Lepr expression in islets. These primers span exons 18-19 and demonstrated the same melting curve product in islet and hypothalamic cDNA. RNA was isolated and cDNA was generated from whole islets or hypothalamus using Trizol plus the Qiagen RNeasy kit, as previously described (42). cDNA was synthesized using 100 ng RNA, as previously described (42). qPCR was performed using 1/3 of the total cDNA made, spread over six wells (42).

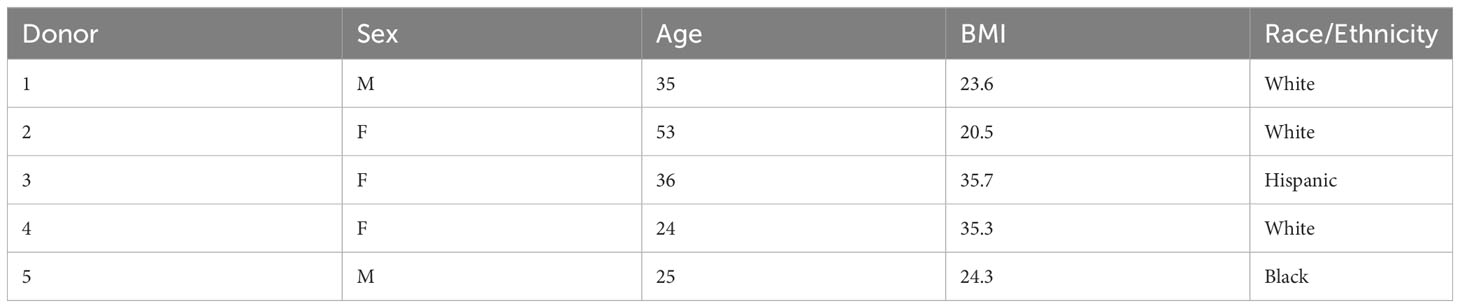

Bulk RNAseq

Human islets were obtained from the Integrated Islet Distribution Program (IIDP). Islet preparation and RNA extraction after intracellular marker cell sorting have been described previously (43). Briefly, islets from five non-diabetic human donors (Table 1) were suspended into a single-cell solution using 0.05% Trypsin, then fixed in 1% PFA, 0.1% saponin, and 1:100 RNasin (Promega). Cells were then indirectly fluorescently immunolabeled against somatostatin and insulin before sorting. RNA was extracted with a Recoverall Total Nucleic Acid kit (Life Technologies). RNA library was prepared and sequenced as previously described (44). Data was analyzed by the University of Pennsylvania Next Generation Sequencing Core, as previously described (44).

scRNAseq

scRNAseq data was downloaded from PANC-DB (pmacs.hpap.upenn.edu) on March 31, 2023, using cell calling performed by the Human Pancreas Analysis Program (HPAP). Non-diabetic, autoantibody-negative male and female donors >17 years of age were included in our analysis. Differential expression analysis was performed as previously described (39).

Results

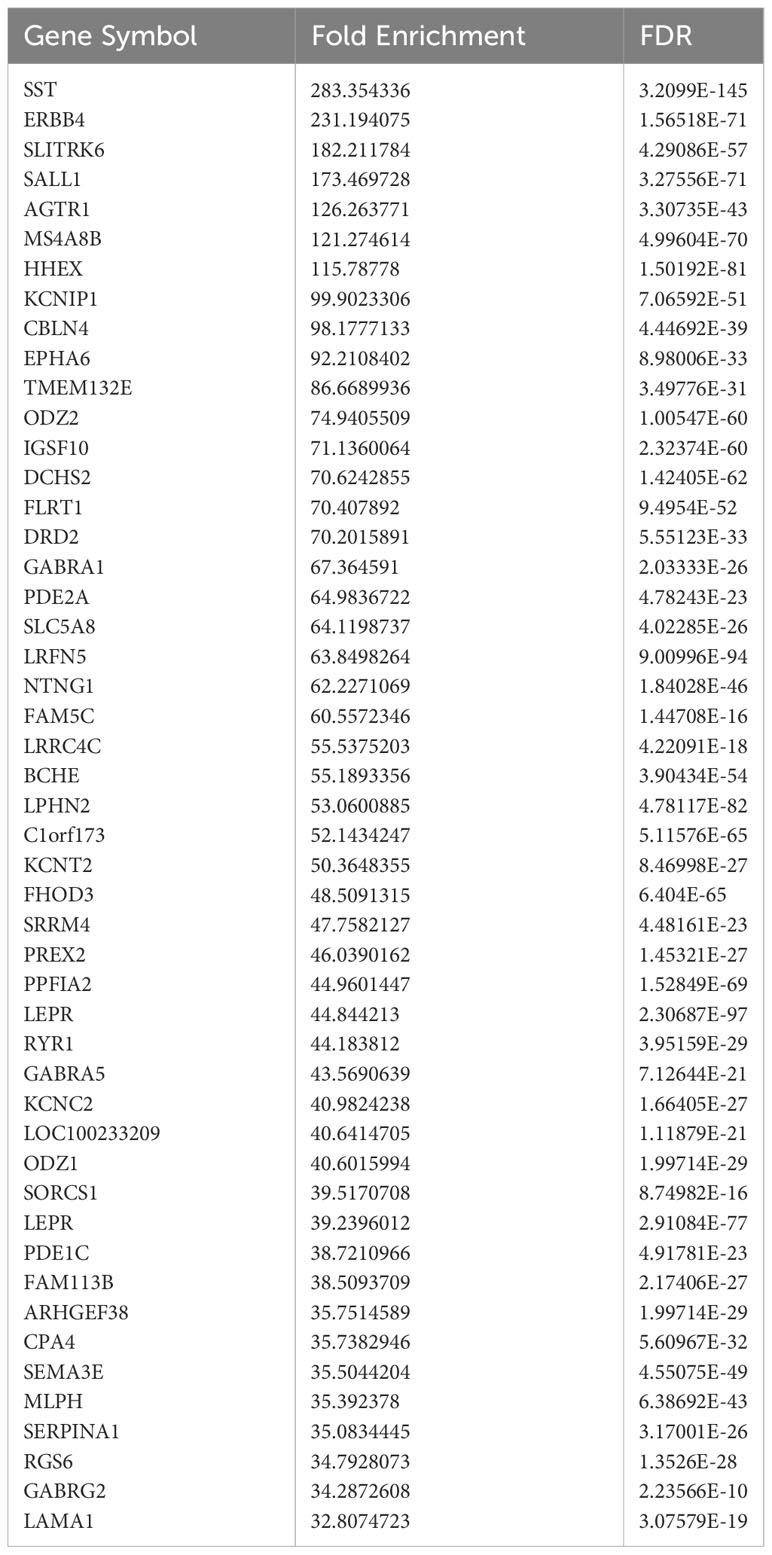

Differential expression between bulk-sorted human beta and delta cells

Current sorting protocols for live human islet cells cannot reliably distinguish delta cells from beta cells (45, 46). Therefore, gene expression differences have been reported between bulk-sorted human alpha and beta cells (47) but not between bulk-sorted human beta and delta cells. To separate these two closely related cell types, we fixed islets from five non-diabetic human donors, suspended them in a single-cell solution, permeabilized them, and indirectly immunolabeled them with antibodies against insulin and somatostatin. These cells then underwent fluorescence-activated cell sorting. RNA was extracted from the purified beta- and delta-cell populations and subjected to RNAseq and analysis. As expected, known lineage-specific genes such as SST and HHEX were enriched in delta cells (Table 2), while genes such as INS and MEG3 were more highly expressed in beta cells (Table 3).

An additional gene enriched within delta cells was LEPR, in agreement with a previous scRNAseq study (23). LEPR appears twice, once as the full-length (NM_002303, >39-fold enriched) and once as a short (NM_001198689, >44-fold enriched) isotype. Since our bulk-sorted RNAseq was performed on a mixture of male and female donors, we also examined gene expression differences between male and female beta and delta cells using publicly available scRNAseq data from the Human Islet Research Network’s Human Pancreas Analysis Program (Table 4; (48)). The genes enriched within male and female delta cells were similar, although the magnitude of differential expression varied. LEPR was elevated in delta cells compared to beta cells by 1.490-fold and 1.328-fold with an adjusted p-value of 3.80 x 10-308 or 9.99 x10-311 in females and males, respectively. Although LEPR was not among the top 50 enriched delta-cell genes in males, it was in females (Table 4). The difference in enrichment of LEPR in human scRNAseq data and bulk-sorted data was observed in most genes and likely reflects the drop-outs that occur in scRNAseq, since only a fraction of expressed genes are detected in any given cell, thus lowering mean expression for the population (49).

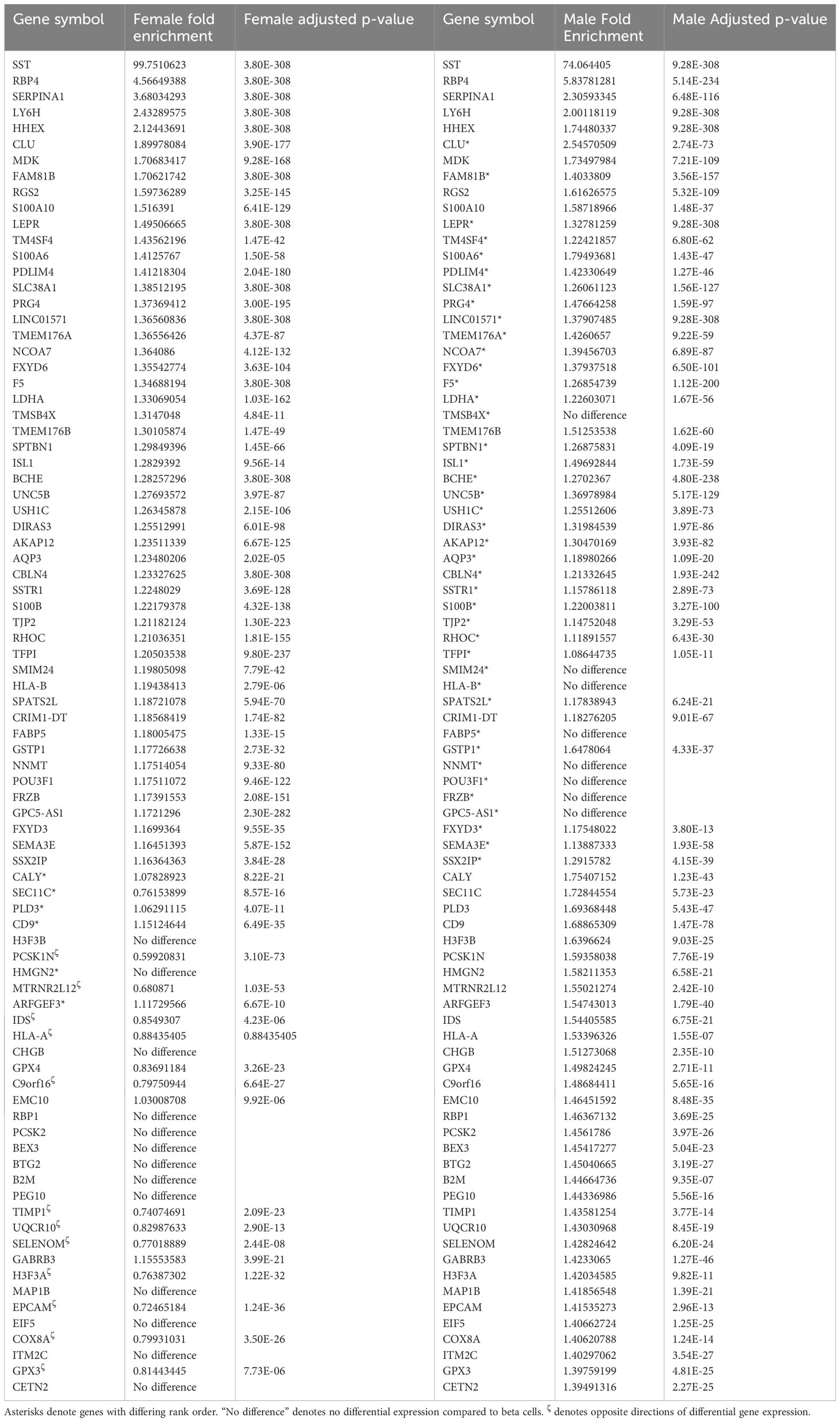

Table 4 Top delta-cell enriched genes compared to beta cells from human (HPAP) scRNAseq samples ranked firstly by female fold enrichment and secondly by male fold enrichment.

Delta-cell-specific deletion of Lepr in mice

Ablation of the Lepr within the mouse pancreatic epithelium results in alterations in glucose homeostasis, whereas ablation within alpha or beta cells does not. Together with the enrichment of LEPR in human delta cells, these results suggested to us that delta cells mediate the inhibited insulin secretion observed in response to leptin treatment. We, therefore, derived a mouse model (SSTrtTA/+;Tet-O-Cre;Leprfl/fl, henceforth referred to as LeprΔδ mice) to test this idea (Figure 1B). Mice were treated with doxycycline for two weeks. In addition to its presence in islet delta cells, somatostatin is also expressed in gut enteroendocrine cells. We, therefore, performed a four-week washout to allow the replenishment of intestinal SST+ cells without Lepr ablation before performing any phenotypical examinations. While the regeneration of islet delta cells from an unrecombined progenitor population rarely occurs, intestinal D cells regenerate within two weeks, while gastric D cells demonstrate apparent regrowth within four weeks and completely recover within three months (50).

Analysis of Lepr gene recombination and RNA expression

We next examined Lepr locus recombination using DNA extracted from pancreatic sections from 36-week-old SstrtTA/+;Tet-O-Cre;Lepr+/fl, SstrtTA/+;Tet-O-Cre;Leprfl/fl, SstrtTA/+;Lepr+/fl, and SstrtTA/+;Leprfl/fl mice treated with doxycycline from eight to ten weeks of age. The Leprfl allele was designed with loxP elements flanking the first exon of Lepr (38). We used primer sets spanning either one loxP element or both loxP elements to directly examine DNA recombination (Figure 2A). Primers traversing only one loxP element amplify unrecombined DNA, which in our model would be expected from non-delta cells. Amplification with these primers resulted in one (Leprfl/fl mice) or two bands (Lepr+/fl) in all samples (Figure 2B), with one band indicating homozygosity of the floxed allele and two bands indicating one wild-type and one floxed allele. The high intensity of these bands remaining in Cre-positive animals reflects the large number of non-delta cells in the pancreas.

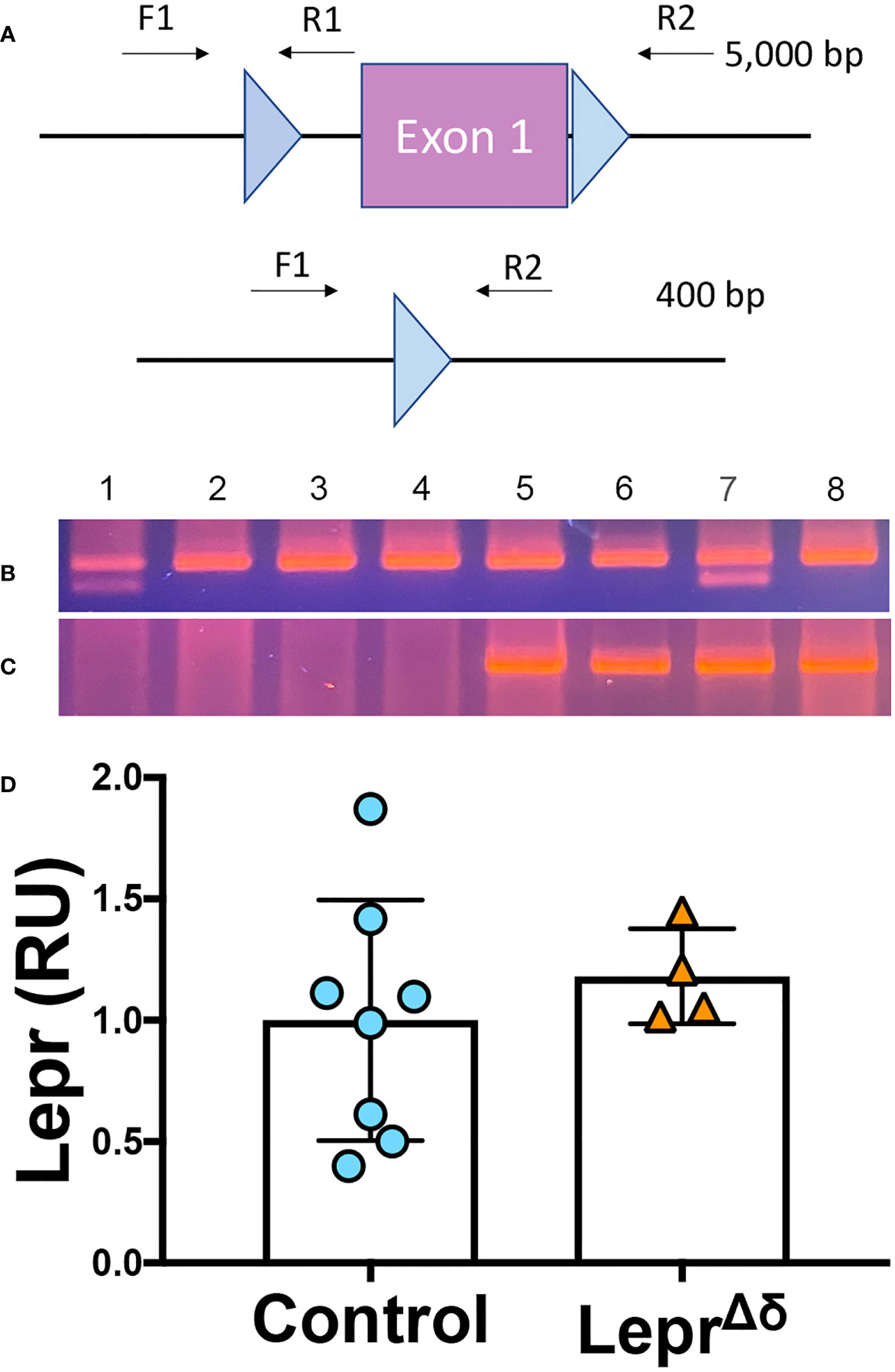

Figure 2 Lepr recombination and expression analysis. (A) Schematic of Leprfl allele and primers used to assess DNA recombination of the loxP elements. (B, C) PCR was performed on DNA collected from fixed pancreatic sections. F1/R1 primers amplify unrecombined DNA (B), while F1/R2 primers result in a ~400bp product after Leprfl recombination (C). All samples tested had one allele of SstrtTA. Samples 1 and 7 were heterozygous for Leprfl, and Samples 2,3,4,5,6, and 8 were homozygous for Leprfl. Samples 1-4 were Tet-O-Cre-negative, while Samples 5-8 were Tet-O-Cre-positive. D) qPCR analysis of Lepr expression in whole islets from LeprΔδ or control mice.

In the absence of recombination, primers flanking both loxP elements span an approximately 5kb distance, a distance too long for amplification using standard PCR reagents (Figure 2A). A recombined Lepr gene would result in an approximately 400-bp amplicon. In the absence of Tet-O-Cre, no band was observed. All samples from mice harboring at least one allele of SstrtTA, Tet-O-Cre, and Leprfl yielded the 400-bp band expected when recombination occurs (Figure 2C), likely reflecting DNA alterations in the delta cells.

To test whether Lepr expression was reduced in LeprΔδ delta cells, whole islets were isolated from 14-week-old LeprΔδ and control mice for quantitative RT-PCR analysis. No difference was observed in Lepr expression between LeprΔδ and control mice (Figure 2D). Others have reported decreased Lepr expression when this Leprfl mouse was used for deletion in other tissues (38). No difference in mRNA, together with the recombination observed in some pancreatic cells, suggested that Lepr is expressed in cells other than delta cells within the islet. We reasoned that we were not detecting Lepr deletion because delta cells make up only a small percentage of mouse islet endocrine cells (~5%), and expression in other cell types would overwhelm differences generated by Lepr absence in delta cells.

Delta-cell-specific Lepr ablation in the mouse results in normal glucose homeostasis and insulin secretion

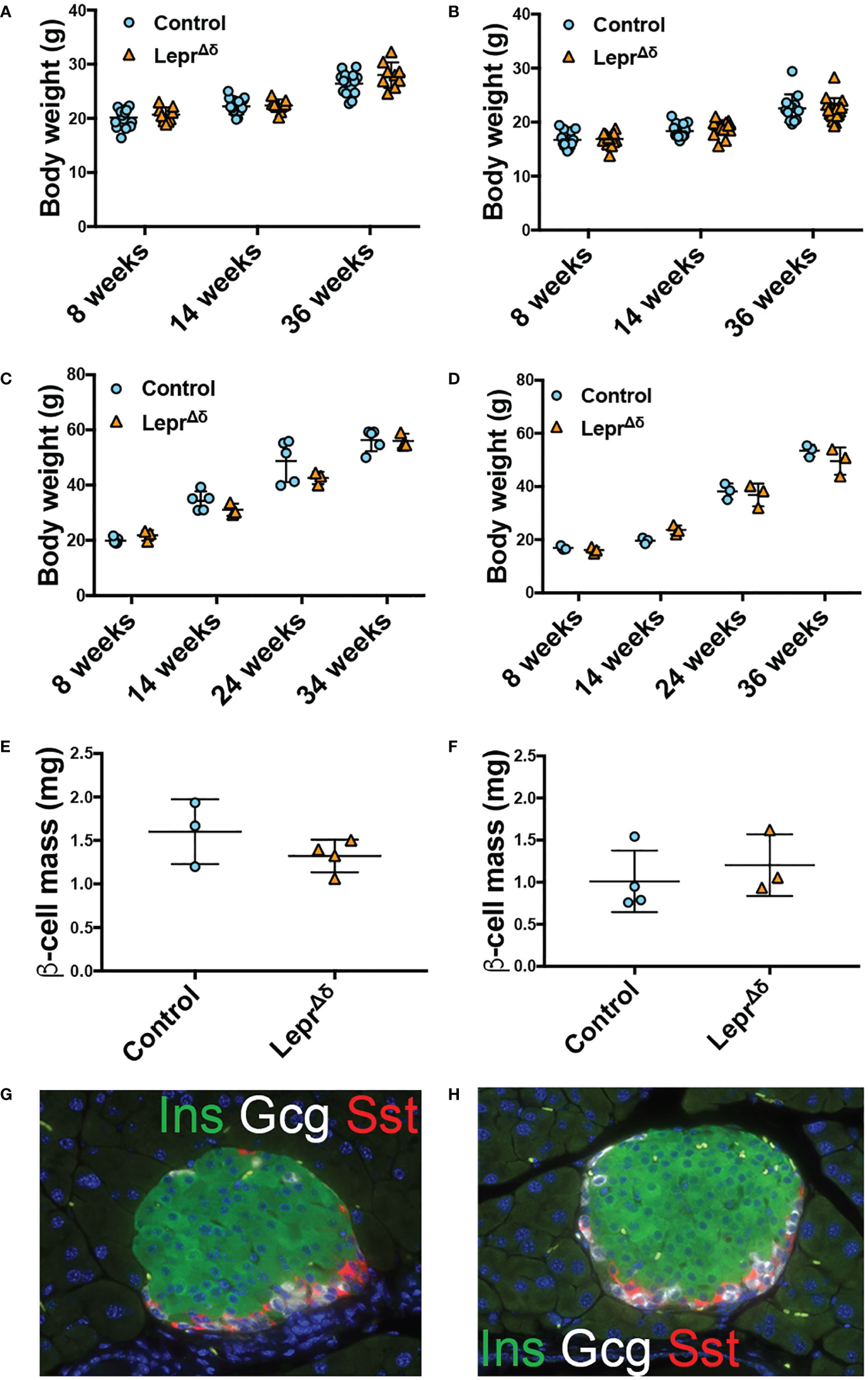

No difference in weight was observed between LeprΔδ and control mice on a high-fat or chow diet (Figures 3A-D). There were no significant differences in beta-cell mass (Figures 3E, F) or islet morphology (Figures 3G, H).

Figure 3 LeprΔδ mice display unaltered weight, beta-cell mass, and islet morphology. (A, B) Body weight for (A) males and (B) females on chow diet. (C, D) Body weight for (C) males and (D) females on high-fat diet. E-F) Beta-cell mass at 36 weeks of age for males (E) and females (F) on HFD. (G, H) Representative image of islets from control (G) and LeprΔδ (H) mice taken at 400X.

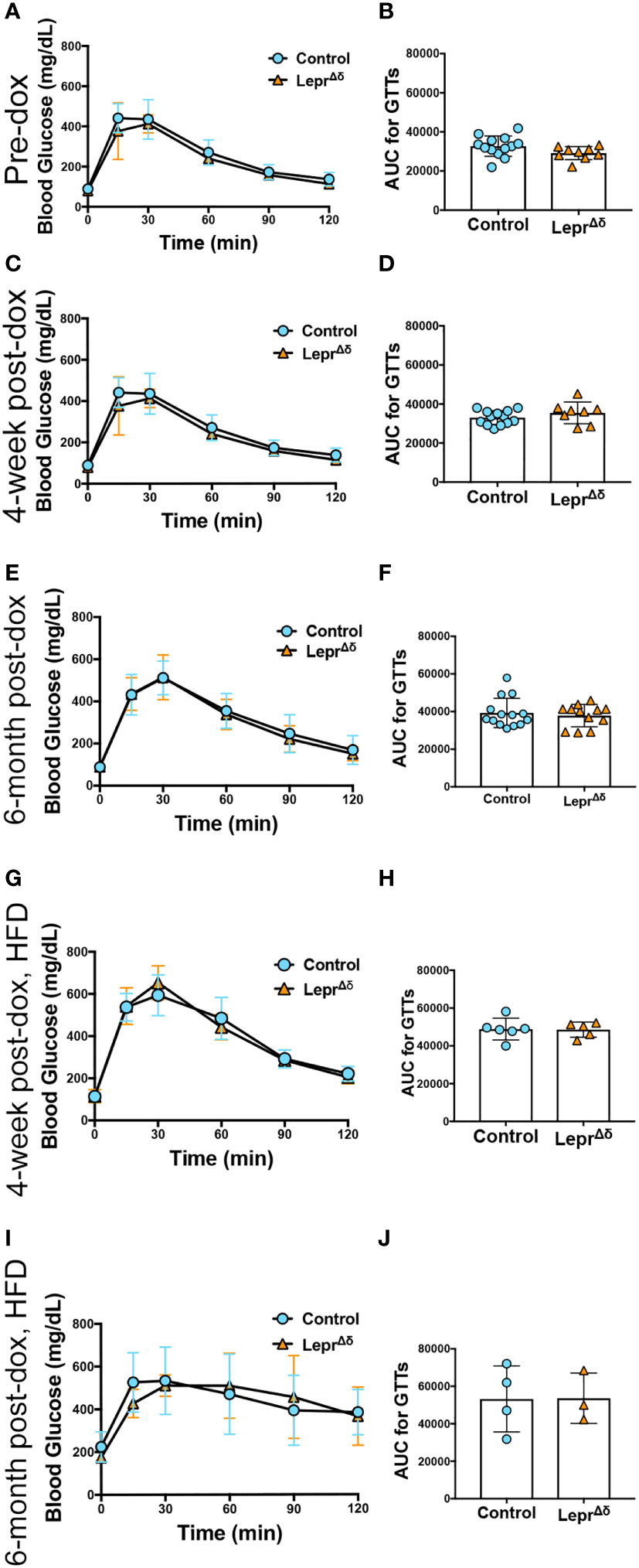

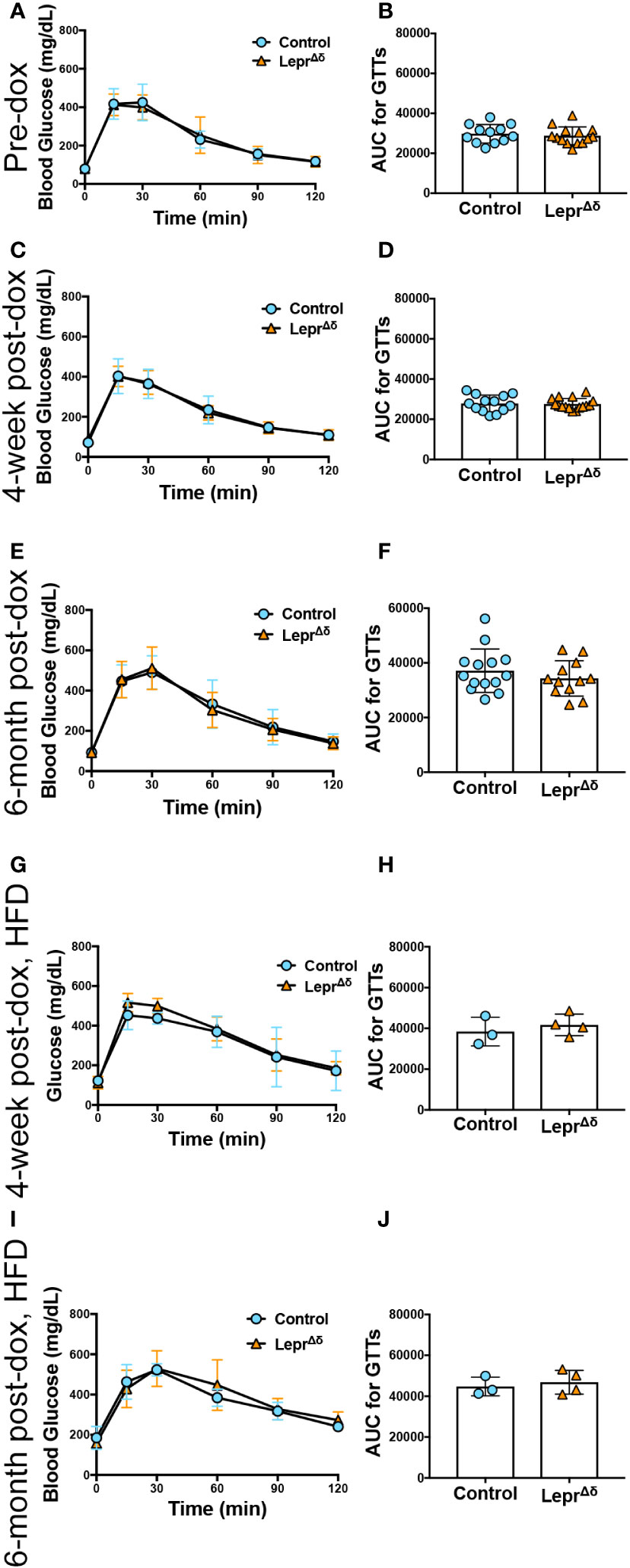

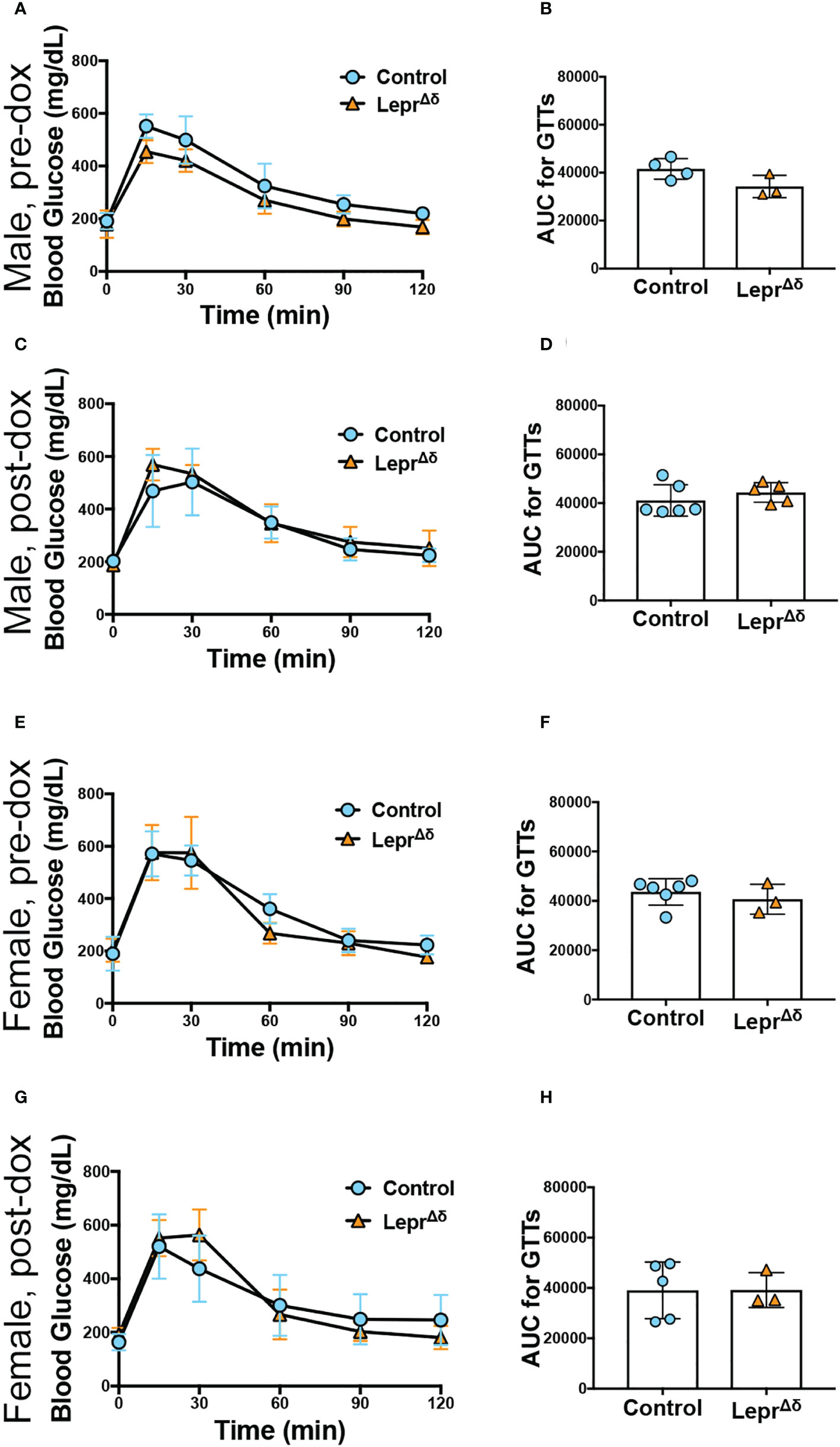

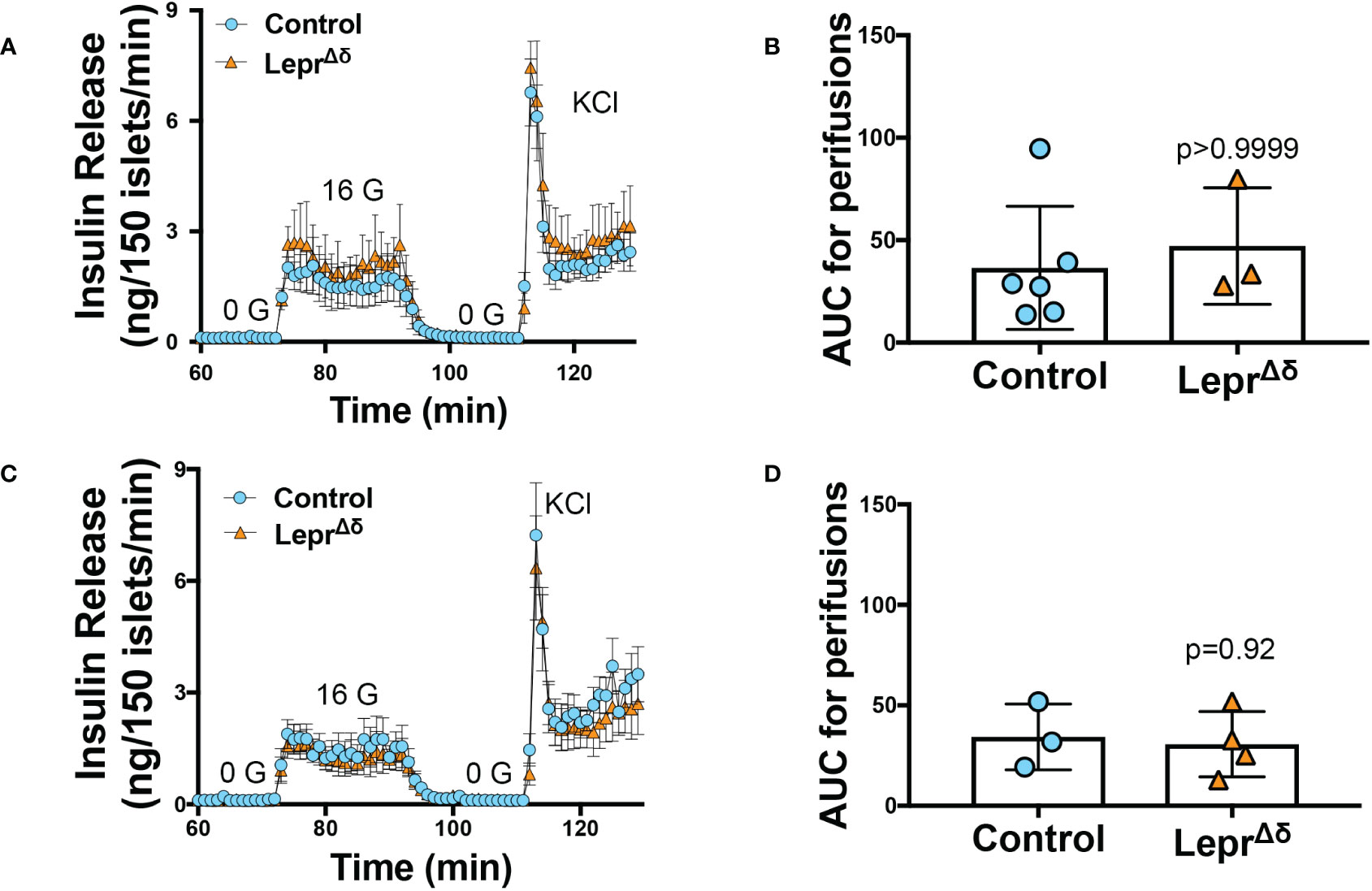

Intraperitoneal GTTs were performed with 2g/kg glucose at 8 weeks, 14 weeks, and 36 weeks of age, corresponding to the pre-doxycycline time point, and then four weeks or six months after doxycycline removal. No difference was observed in glucose tolerance in male (Figure 4) or female (Figure 5) LeprΔδ mice at any time point, whether the mice were on a standard chow or high-fat diet. To rule out the possibility that we were missing subtle differences, GTTs were also performed on males and females on a HFD diet using 1g/kg glucose (Figure 6). Again, no alterations in glucose tolerance were observed. Insulin secretion was examined by islet perifusion at 36 weeks of age. Islets from male and female LeprΔδ mice displayed no significant differences in insulin secretion compared to controls (Figures 7A-D).

Figure 4 LeprΔδ male mice display normal glucose tolerance on chow and high-fat diet. (A-J) GTTs (A, C, E, G, I) and corresponding area-under-the-curve analysis (B, D, F, H, J) for male LeprΔδ mice prior to doxycycline administration (A, B), at 14 weeks of age and four weeks after doxycycline removal and placement on a chow diet (C, D), at 36 weeks and six months after doxycycline removal and placement on a chow diet (E, F), at 14 weeks of age and four weeks after doxycycline removal and placement on a high-fat diet (G, H), and at 36 weeks of age and 26 weeks (6 months) after doxycycline removal and placement on a high-fat diet.

Figure 5 LeprΔδ female mice display normal glucose tolerance on chow and high-fat diet. (A-J) GTTs (A, C, E, G, I) and corresponding area-under-the-curve analysis (B, D, F, H, J) for female LeprΔδ mice prior to doxycycline administration (A, B), at 14 weeks of age and four weeks after doxycycline removal and placement on a chow diet (C, D), at 36 weeks and six months after doxycycline removal and placement on a chow diet (E, F), at 14 weeks of age and four weeks after doxycycline removal and placement on a high-fat diet (G, H), and at 36 weeks of age and 26 weeks (6 months) after doxycycline removal and placement on a high-fat diet.

Figure 6 Male and female LeprΔδ mice on a high-fat diet display normal glucose tolerance in response to a reduced glucose load. Glucose tolerance tests using 1g/kg glucose were performed before doxycycline treatment (A, B, E, F) and at 14 weeks of age in male (C, D) and female (E-H) LeprΔδ and control mice on a HFD diet starting at 10 weeks of age. Glucose curves (A, C, E, G) and area-under-the-curve (B, D, F, H) are shown.

Figure 7 Islets from LeprΔ mice display normal insulin secretion in response to high glucose. Isolated islets from 36-week old male (A, B) and female (C, D) LeprΔδ and control mice were subjected to perifusions (A, C) at 0 mM glucose (0 G), 16 mM glucose (16 G), and with KCl. Both males (A, B) and females (C, D) were examined. Area-under-the-curve for 16 mM glucose is shown (B, D).

Lepr is expressed in endothelial cell clusters within the mouse islet

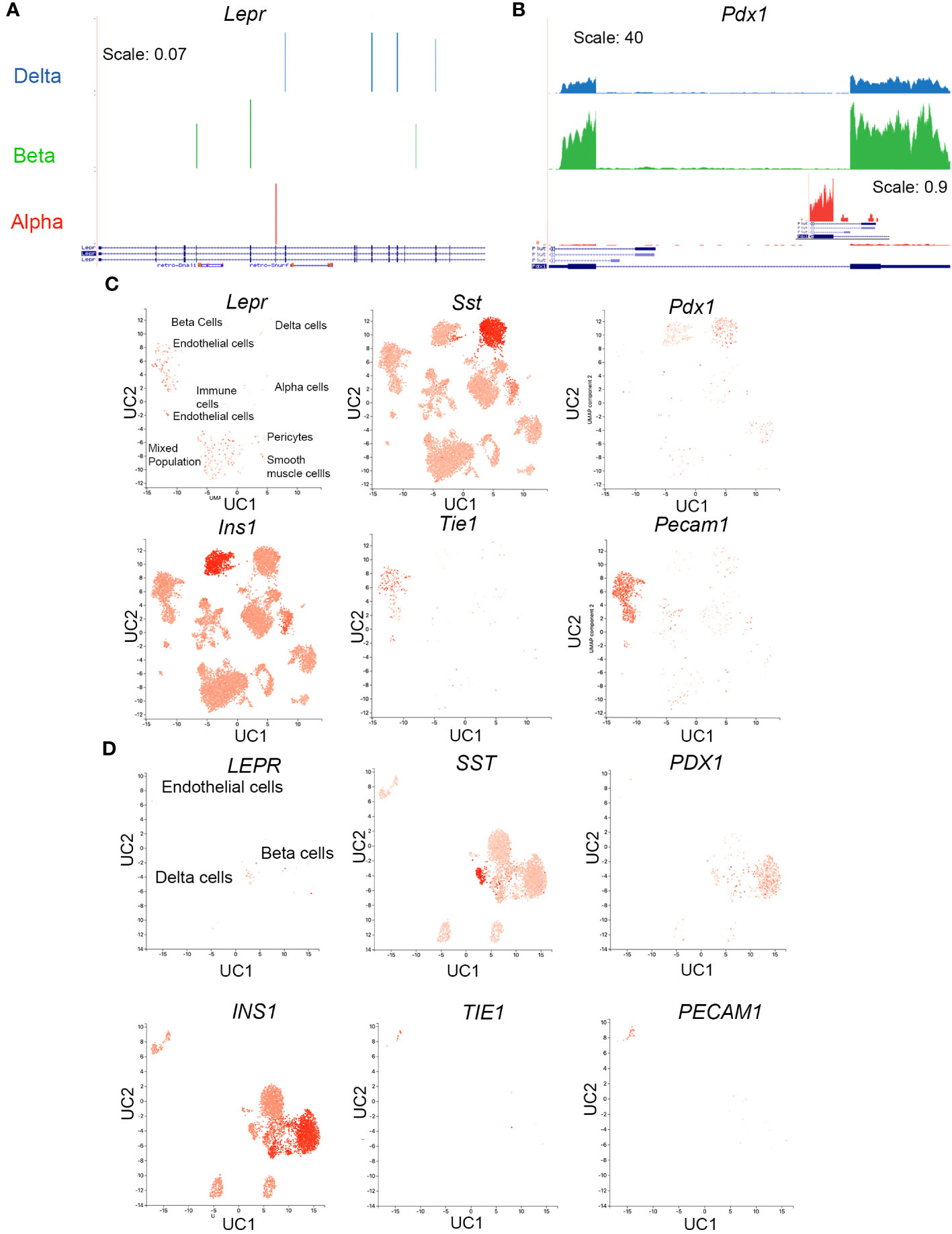

We next examined Lepr expression in mouse alpha, beta, and delta cells using a published dataset built from fluorescently sorted populations of live lineage-traced cells. Lepr was not detected in mouse alpha, beta, or delta cells (Figure 8A, (31)). This result starkly contrasts those for the transcription factor Pdx1, which is observed at the RNA level in each population (Figure 8B) despite the limitation of PDX1 protein expression to beta and delta cells.

Figure 8 Lepr is not expressed in mouse delta cells. (A, B) RNAseq reads for Lepr (A) and Pdx1 (B) in sorted alpha, beta, and delta cells were obtained from publicly available data. An inset for exon 1 Pdx1 expression in alpha cells at a zoomed-in scale is included to demonstrate the appearance of lower-expressed genes. (C) scRNAseq expression in mouse islets cells for Lepr, Sst, Pdx1, Ins, and two endothelial markers, Tie1 and Pecam, was obtained from the public database PanglaoDB (https://panglaodb.se SRA745567). (D) scRNAseq expression in human islet cells for LEPR, SSST, PDX1, INS, TIE1, and PECAM was obtained from PanglaoDB (SRA701877).

Examination of a publicly available scRNAseq dataset uploaded to the PanglaoDB webserver with visualization capability (51) confirmed a lack of Lepr expression within the mouse islet endocrine population (Figure 8C). Most Lepr-positive cells are located in endothelial cell clusters (labeled in Figure 8C). An additional cell cluster exhibits Lepr expression; cells in this cluster expressed markers of several cell types, including Tie-1, Sst, Ins, Pecam, and Pdx1, among others. These cells may be doublets, the droplets capturing these cells may have been severely contaminated with RNA from lysed cells, or the number of genes sequenced in these cells may be too low for good segregation, since the mean number of genes per cell was 1528 (52, 53). This cluster contains many Tie-1+ and Pecam+ cells, both of which are endothelial cell markers.

Because islet Lepr expression appears within the mouse endothelial cell population, we assessed whether it is also expressed in human islet endothelial cells, again using publicly available data uploaded to Panglao DB (51). Unlike in the mouse islet, only a small percentage of cells within the human islet endothelial cluster expressed LEPR and most are observed in the delta-cell cluster (Figure 8D).

Conclusions

Multiple labs have demonstrated that leptin decreases insulin secretion from isolated islets from multiple species. In addition, beta cells from control mice hyperpolarize in response to leptin, but this response is lost in beta cells from global Lepr null mice (54). These data suggest that a cell type within the islet mediates altered insulin secretion in response to leptin. However, pinpointing this cell type has proven to be challenging.

Pdx1-Cre is expressed throughout the pancreatic epithelium; this Cre line induces recombination of Lepr in the islet endocrine and exocrine cells but not in the immune, endothelial, or smooth muscle cells isolated along with the islet (55). Pdx1-Cre;Leprfl/fl male and female mice on a normal chow diet exhibited improved glucose tolerance, normal insulin tolerance, and increased fasting serum insulin (18). Isolated Pdx1-Cre;Leprfl/fl islets display increased Ca2+ influx and insulin secretion compared to Leprfl/fl controls without Cre. Furthermore, leptin treatment represses insulin secretion in isolated islets from control but not Pdx1-Cre;Leprfl/fl mice (18).

Many Cre lines that are expressed in the islet are also expressed in other tissues. RIP-Cre is expressed in the brain, including in hypothalamic neurons, and RIP-Cre25Mgn deletion of Lepr results in obesity, impaired glucose-stimulated insulin secretion, and a seemingly paradoxical reduced fasting blood glucose (19, 56). Pdx1-Cre is also expressed in the brain, primarily in the hypothalamus, and the overall Pdx1-Cre;Leprfl/fl phenotype may result from this limited neuronal Lepr ablation (22, 56); however, whether neuronal deletion can explain altered insulin secretion Ca2+ influx in islets isolated from Pdx1-Cre;Leprfl/fl mice is less clear. Neuronal effects on islets have been reported to be lost ex vivo (57).

Glucagon and Gcg-Cre are expressed in the hindbrain, olfactory neurons, and gut enteroendocrine L cells, as well as in islet alpha cells (21). The transgenic Gcg-Cre exhibits silencing, with recombination in only 30-45% of alpha cells, and the inducible gene replacement Gcg-CreERT2 line suffers from glucagon haploinsufficiency (58). Somatostatin, Sst-Cre, and the Sst-rtTA used here are all expressed in gut enteroendocrine D cells, hypothalamic neurons, and the motor cortex (50).

Had the alpha or delta-cell Lepr ablation models resulted in altered glucose homeostasis, the cell type responsible would have been unclear. When using inducible Sst- and Gcg-driven lines, though, it is important to note a washout period can allow high-turnover cell populations, like gut enteroendocrine cells, to regenerate while the more slow-growing islet endocrine cells retain their deletion.

The Pdx1-Cre;Leprfl/fl phenotype data suggest that pancreatic epithelial cells are responsible for the leptin-induced depression of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in isolated islets. However, loss of Lepr in alpha cells using an inducible Glucagon-Cre (21), in beta cells using Ins1-Cre (21), or in delta cells (demonstrated here) does not result in altered glucose tolerance or insulin secretion. Additionally, bulk RNAseq of sorted mouse alpha, beta, or delta cells cannot detect Lepr. In addition, when we examined Lepr expression in control and LeprΔδ islets, we saw no difference in Lepr expression. We initially attributed this lack of change despite seeing recombined DNA to the rarity of the delta cell. However, after examining Lepr in mouse islet scRNAseq data and in RNAseq data from sorted alpha, beta, and delta cells, we now deduce that detectable Lepr in the islet is likely expressed in endothelial cells (11, 18).

We unsuccessfully attempted to detect LEPR protein expression in the mouse pancreas using immunofluorescence and immunohistochemistry using an antibody previously used to detect LEPR mouse endothelial cells in other tissues (59). These data may indicate that no LEPR protein is synthesized in the pancreas; however, multiple groups have had difficulty immunolabeling LEPR, even in the hypothalamus (60). Because of the difficulty of LEPR immunolabeling, Lepr-Cre lines have been utilized in conjunction with a reporter mouse to detect Lepr expression patterns. In a Lepr-Cre;TdTomato line, TdTomato did not colocalize with insulin or glucagon in tissue sections, and the images shown had no TdTomato expression within the islets (61). However, TdTomato was detected in cells located in circular structures outside of the islets resembling blood vessels.

Lepr is expressed in mouse T cells (62, 63), endothelial cells (64), and smooth muscle cells (64). Here, we show the presence of Lepr in mouse islet endothelial cells using publicly available RNAseq data. These data suggest that, in the mouse, islet endothelial cells mediate the effect of leptin on insulin secretion. However, mice with Lepr deleted specifically in endothelial cells using a Tie2-Cre display unchanged ad libitum-fed blood glucose (41, 59). A more systematic analysis of glucose homeostasis was not performed.

Endothelial cells regulate beta-cell function and insulin release through factors such as Endothelin-1 and Thrombospondin-1 (65, 66). Thus, signaling changes between endothelial and beta cells in response to leptin treatment may mediate decreased insulin secretion in mouse islets. However, Pdx1-Cre should not have activity in endothelial cells; therefore, the endothelial cells are unlikely to underlie altered insulin secretion in the Pdx1-Cre;Leprfl/fl model. In human islets, LEPR is seen in scant endothelial cells by scRNAseq; thus, in human islets, any effect of leptin on insulin release is unlikely through endothelial cells. Instead, LEPR enrichment within the human delta-cell population suggests that the delta cell mediates the reduced insulin secretion response to leptin in human islets.

In contrast to what likely occurs in humans, we provide evidence that the mouse delta cell does not control this response. Further work will be necessary to definitively determine how leptin affects insulin secretion in various species. These data should serve as a deterrent from extrapolating the effects and mechanisms of islet leptin treatment from one species to another.

Data availability statement

Original datasets are available in a publicly accessible repository: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/, accession number: GSE243984. Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study and can be found at hpap.pmacs.upenn.edu. Publicly available datasets were used as previously analyzed and can be found at https://huisinglab.com/islet_txomes_2016/index.html and at https://panglaodb.se/, accession numbers SRA745567 and SRA701877. All other data is available upon reasonable request.

Ethics statement

For studies involving human cadaveric material, a waiver was obtained by Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with local legislation and institutional requirements. The human samples used in this study were acquired from the Integrated Islet Distribution Program, funded by Special Statutory Funding Program for Type 1 Diabetes Research, administered by the NIDDK. The IIDP works with islet isolation centers throughout the United States to provide de-identified islets from cadaveric donors to researchers. Written informed consent for participation was obtained from relatives of donors by OPOs before the IIDP received and disseminated islets. The animal studies were approved by Johns Hopkins University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

JZ: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. KK: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. EM: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. AY: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. GP: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. MG: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

Human pancreatic islets were provided by the NIDDK-funded Integrated Islet Distribution Program (IIDP) at City of Hope (U24-DK-098085). Human islet scRNAseq data was obtained from the NIDDK-funded Human Pancreas Analysis Program (HPAP) Database, a Human Islet Research Network (HIRN) consortium (UC4-DK-112217, U01-DK-123594, UC4-DK-112232, AND U01-DK-123716). This work was supported by R01-DK-110183 to MLG and a sub-award to MLG from NIH P30-DK-019525 to MAL.

Acknowledgments

CM Cherry Consulting analyzed gene expression in HPAP scRNAseq data. The authors used Grammarly 1.33.2.0 to help edit the manuscript but reviewed all suggested changes.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Obradovic M, Sudar-Milovanovic E, Soskic S, Essack M, Arya S, Stewart AJ, et al. Leptin and obesity: role and clinical implication. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) (2021) 12:585887. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2021.585887

2. Morris DL, Rui L. Recent advances in understanding leptin signaling and leptin resistance. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab (2009) 297:E1247–1259. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00274.2009

3. Kelesidis T, Kelesidis I, Chou S, Mantzoros CS. Narrative review: the role of leptin in human physiology: emerging clinical applications. Ann Intern Med (2010) 152:93–100. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-2-201001190-00008

4. Gorska E, Popko K, Stelmaszczyk-Emmel A, Ciepiela O, Kucharska A, Wasik M. Leptin receptors. Eur J Med Res (2010) 15 Suppl 2:50–4. doi: 10.1186/2047-783X-15-S2-50

5. Bjorbaek C, Elmquist JK, Michl P, Ahima RS, van Bueren A, McCall AL, et al. Expression of leptin receptor isoforms in rat brain microvessels. Endocrinology (1998) 139:3485–91. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.8.6154

6. Lee GH, Proenca R, Montez JM, Carroll KM, Darvishzadeh JG, Lee JI, et al. Abnormal splicing of the leptin receptor in diabetic mice. Nature (1996) 379:632–5. doi: 10.1038/379632a0

7. Golson ML, Misfeldt AA, Kopsombut UG, Petersen CP, Gannon M. High Fat Diet Regulation of beta-Cell Proliferation and beta-Cell Mass. Open Endocrinol J (2010) 4:66–66. doi: 10.2174/1874216501004010066

8. Tu H, Kastin AJ, Hsuchou H, Pan W. Soluble receptor inhibits leptin transport. J Cell Physiol (2008) 214:301–5. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21195

9. Drori A, Gammal A, Azar S, Hinden L, Hadar R, Wesley D, et al. CB(1)R regulates soluble leptin receptor levels via CHOP, contributing to hepatic leptin resistance. Elife (2020) 9. doi: 10.7554/eLife.60771

10. Butiaeva LI, Slutzki T, Swick HE, Bourguignon C, Robins SC, Liu X, et al. Leptin receptor-expressing pericytes mediate access of hypothalamic feeding centers to circulating leptin. Cell Metab (2021) 33:1433–1448 e1435. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2021.05.017

11. Emilsson V, Liu YL, Cawthorne MA, Morton NM, Davenport M. Expression of the functional leptin receptor mRNA in pancreatic islets and direct inhibitory action of leptin on insulin secretion. Diabetes (1997) 46:313–6. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.2.313

12. Fei H, Okano HJ, Li C, Lee GH, Zhao C, Darnell R, et al. Anatomic localization of alternatively spliced leptin receptors (Ob-R) in mouse brain and other tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (1997) 94:7001–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.13.7001

13. Kieffer TJ, Heller RS, Leech CA, Holz GG, Habener JF. Leptin suppression of insulin secretion by the activation of ATP-sensitive K+ channels in pancreatic beta-cells. Diabetes (1997) 46:1087–93. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.6.1087

14. Kulkarni RN, Wang ZL, Wang RM, Hurley JD, Smith DM, Ghatei MA, et al. Leptin rapidly suppresses insulin release from insulinoma cells, rat and human islets and, in vivo, in mice. J Clin Invest (1997) 100:2729–36. doi: 10.1172/JCI119818

15. Tanizawa Y, Okuya S, Ishihara H, Asano T, Yada T, Oka Y. Direct stimulation of basal insulin secretion by physiological concentrations of leptin in pancreatic beta cells. Endocrinology (1997) 138:4513–6. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.10.5576

16. Ookuma M, Ookuma K, York DA. Effects of leptin on insulin secretion from isolated rat pancreatic islets. Diabetes (1998) 47:219–23. doi: 10.2337/diab.47.2.219

17. Ceddia RB, William WN Jr., Carpinelli AR, Curi R. Modulation of insulin secretion by leptin. Gen Pharmacol (1999) 32:233–7. doi: 10.1016/S0306-3623(98)00185-2

18. Morioka T, Asilmaz E, Hu J, Dishinger JF, Kurpad AJ, Elias CF, et al. Disruption of leptin receptor expression in the pancreas directly affects beta cell growth and function in mice. J Clin Invest (2007) 117:2860–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI30910

19. Covey SD, Wideman RD, McDonald C, Unniappan S, Huynh F, Asadi A, et al. The pancreatic beta cell is a key site for mediating the effects of leptin on glucose homeostasis. Cell Metab (2006) 4:291–302. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.09.005

20. Singha A, Palavicini JP, Pan M, Farmer S, Sandoval D, Han X, et al. Leptin receptors in RIP-Cre(25Mgn) neurons mediate anti-dyslipidemia effects of leptin in insulin-deficient mice. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) (2020) 11:588447. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2020.588447

21. Soedling H, Hodson DJ, Adrianssens AE, Gribble FM, Reimann F, Trapp S, et al. Limited impact on glucose homeostasis of leptin receptor deletion from insulin- or proglucagon-expressing cells. Mol Metab (2015) 4:619–30. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2015.06.007

22. Tuduri E, Denroche HC, Kara JA, Asadi A, Fox JK, Kieffer TJ. Partial ablation of leptin signaling in mouse pancreatic alpha-cells does not alter either glucose or lipid homeostasis. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab (2014) 306:E748–755. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00681.2013

23. Lawlor N, George J, Bolisetty M, Kursawe R, Sun L, Sivakamasundari V, et al. Single-cell transcriptomes identify human islet cell signatures and reveal cell-type-specific expression changes in type 2 diabetes. Genome Res (2017) 27:208–22. doi: 10.1101/gr.212720.116

24. Sahu A. Intracellular leptin-signaling pathways in hypothalamic neurons: the emerging role of phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase-phosphodiesterase-3B-cAMP pathway. Neuroendocrinology (2011) 93:201–10. doi: 10.1159/000326785

25. Ratke J, Entschladen F, Niggemann B, Zanker KS, Lang K. Leptin stimulates the migration of colon carcinoma cells by multiple signaling pathways. Endocr Relat Cancer (2010) 17:179–89. doi: 10.1677/ERC-09-0225

26. El-Zein O, Kreydiyyeh SI. Leptin inhibits glucose intestinal absorption via PKC, p38MAPK, PI3K and MEK/ERK. PloS One (2013) 8:e83360. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083360

27. Biden TJ, Schmitz-Peiffer C, Burchfield JG, Gurisik E, Cantley J, Mitchell CJ, et al. The diverse roles of protein kinase C in pancreatic beta-cell function. Biochem Soc Trans (2008) 36:916–9. doi: 10.1042/BST0360916

28. Hofmann F. PKC and calcium channel trafficking. Channels (Austin) (2018) 12:15–6. doi: 10.1080/19336950.2017.1397924

29. Denwood G, Tarasov A, Salehi A, Vergari E, Ramracheya R, Takahashi H, et al. Glucose stimulates somatostatin secretion in pancreatic delta-cells by cAMP-dependent intracellular Ca(2+) release. J Gen Physiol (2019) 151:1094–115. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201912351

30. van der Meulen T, Donaldson CJ, Caceres E, Hunter AE, Cowing-Zitron C, Pound LD, et al. Urocortin3 mediates somatostatin-dependent negative feedback control of insulin secretion. Nat Med (2015) 21:769–76. doi: 10.1038/nm.3872

31. DiGruccio MR, Mawla AM, Donaldson CJ, Noguchi GM, Vaughan J, Cowing-Zitron C, et al. Comprehensive alpha, beta and delta cell transcriptomes reveal that ghrelin selectively activates delta cells and promotes somatostatin release from pancreatic islets. Mol Metab (2016) 5:449–58. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2016.04.007

32. Orgaard A, Holst JJ. The role of somatostatin in GLP-1-induced inhibition of glucagon secretion in mice. Diabetologia (2017) 60:1731–9. doi: 10.1007/s00125-017-4315-2

33. Briant LJB, Reinbothe TM, Spiliotis I, Miranda C, Rodriguez B, Rorsman P. delta-cells and beta-cells are electrically coupled and regulate alpha-cell activity via somatostatin. J Physiol (2018) 596:197–215. doi: 10.1113/JP274581

34. Huising MO, van der Meulen T, Huang JL, Pourhosseinzadeh MS, Noguchi GM. The difference delta-cells make in glucose control. Physiol (Bethesda) (2018) 33:403–11. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00029.2018

35. Vierra NC, Dickerson MT, Jordan KL, Dadi PK, Katdare KA, Altman MK, et al. TALK-1 reduces delta-cell endoplasmic reticulum and cytoplasmic calcium levels limiting somatostatin secretion. Mol Metab (2018) 9:84–97. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2018.01.016

36. Cigliola V, Ghila L, Thorel F, van Gurp L, Baronnier D, Oropeza D, et al. Pancreatic islet-autonomous insulin and smoothened-mediated signalling modulate identity changes of glucagon(+) alpha-cells. Nat Cell Biol (2018) 20:1267–77. doi: 10.1038/s41556-018-0216-y

37. Perl AK, Wert SE, Nagy A, Lobe CG, Whitsett JA. Early restriction of peripheral and proximal cell lineages during formation of the lung. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2002) 99:10482–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152238499

38. Cohen P, Zhao C, Cai X, Montez JM, Rohani SC, Feinstein P, et al. Selective deletion of leptin receptor in neurons leads to obesity. J Clin Invest (2001) 108:1113–21. doi: 10.1172/JCI200113914

39. Peng G, Mosleh E, Yuhas A, Katada K, Cherry C, Golson ML. FOXM1 acts sexually dimorphically to regulate functional beta-cell mass. bioRxiv (2023). doi: 10.1101/2023.01.12.523673

40. Bankhead P, Loughrey MB, Fernandez JA, Dombrowski Y, McArt DG, Dunne PD, et al. QuPath: Open source software for digital pathology image analysis. Sci Rep (2017) 7:16878. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-17204-5

41. Hubert A, Bochenek ML, Schutz E, Gogiraju R, Munzel T, Schafer K. Selective deletion of leptin signaling in endothelial cells enhances neointima formation and phenocopies the vascular effects of diet-induced obesity in mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol (2017) 37:1683–97. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.117.309798

42. Mosleh E, Ou K, Haemmerle MW, Tembo T, Yuhas A, Carboneau BA, et al. Ins1-Cre and Ins1-CreER gene replacement alleles are susceptible to silencing by DNA hypermethylation. Endocrinology (2020) 161. doi: 10.1210/endocr/bqaa054

43. Hrvatin S, Deng F, O’Donnell CW, Gifford DK, Melton DA. MARIS: method for analyzing RNA following intracellular sorting. PloS One (2014) 9:e89459. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089459

44. Dorrell C, Schug J, Canaday PS, Russ HA, Tarlow BD, Grompe MT, et al. Human islets contain four distinct subtypes of beta cells. Nat Commun (2016) 7:11756. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11756

45. Dorrell C, Abraham SL, Lanxon-Cookson KM, Canaday PS, Streeter PR, Grompe M. Isolation of major pancreatic cell types and long-term culture-initiating cells using novel human surface markers. Stem Cell Res (2008) 1:183–94. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2008.04.001

46. Saunders DC, Brissova M, Phillips N, Shrestha S, Walker JT, Aramandla R, et al. Ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase-3 antibody targets adult human pancreatic beta cells for In Vitro and In Vivo analysis. Cell Metab (2019) 29:745–754 e744. doi: 10.1006/j.cmet.2018.10.007

47. Bramswig NC, Everett LJ, Schug J, Dorrell C, Liu C, Luo Y, et al. Epigenomic plasticity enables human pancreatic alpha to beta cell reprogramming. J Clin Invest (2013) 123:1275–84. doi: 10.1172/JCI66514

48. Shapira SN, Naji A, Atkinson MA, Powers AC, Kaestner KH. Understanding islet dysfunction in type 2 diabetes through multidimensional pancreatic phenotyping: The Human Pancreas Analysis Program. Cell Metab (2022) 34:1906–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2022.09.013

49. Kiselev VY, Andrews TS, Hemberg M. Challenges in unsupervised clustering of single-cell RNA-seq data. Nat Rev Genet (2019) 20:273–82. doi: 10.1038/s41576-018-0088-9

50. Huang JL, Lee S, Pourhosseinzadeh MS, Krämer N, Guillen JV, Cinque NH, et al. Paracrine signaling by pancreatic δ cells determines the glycemic set point in mice. bioRxiv (2022):496132. doi: 10.1101/2022.06.29.496132

51. von Berger L, Henrichs I, Raptis S, Heinze E, Jonatha W, Teller WM, et al. Gastrin concentration in plasma of the neonate at birth and after the first feeding. Pediatrics (1976) 58:264–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.58.2.264

52. Do VH, Canzar S. A generalization of t-SNE and UMAP to single-cell multimodal omics. Genome Biol (2021) 22:130. doi: 10.1186/s13059-021-02356-5

53. Arceneaux D, Chen Z, Simmons AJ, Heiser CN, Southard-Smith AN, Brenan MJ, et al. A contamination focused approach for optimizing the single-cell RNA-seq experiment. iScience (2023) 26:107242. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2023.107242

54. Cochrane VA, Wu Y, Yang Z, ElSheikh A, Dunford J, Kievit P, et al. Leptin modulates pancreatic beta-cell membrane potential through Src kinase-mediated phosphorylation of NMDA receptors. J Biol Chem (2020) 295:17281–97. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA120.015489

55. Gu G, Dubauskaite J, Melton DA. Direct evidence for the pancreatic lineage: NGN3+ cells are islet progenitors and are distinct from duct progenitors. Development (2002) 129:2447–57. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.10.2447

56. Wicksteed B, Brissova M, Yan W, Opland DM, Plank JL, Reinert RB, et al. Conditional gene targeting in mouse pancreatic beta-Cells: analysis of ectopic Cre transgene expression in the brain. Diabetes (2010) 59:3090–8. doi: 10.2337/db10-0624

57. Thorens B. Neural regulation of pancreatic islet cell mass and function. Diabetes Obes Metab (2014) 16 Suppl 1:87–95. doi: 10.1111/dom.12346

58. Ackermann AM, Zhang J, Heller A, Briker A, Kaestner KH. High-fidelity Glucagon-CreER mouse line generated by CRISPR-Cas9 assisted gene targeting. Mol Metab (2017) 6:236–44. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2017.01.003

59. Gogiraju R, Witzler C, Shahneh F, Hubert A, Renner L, Bochenek ML, et al. Deletion of endothelial leptin receptors in mice promotes diet-induced obesity. Sci Rep (2023) 13:8276. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-35281-7

60. Patterson CM, Leshan RL, Jones JC, Myers MG Jr. Molecular mapping of mouse brain regions innervated by leptin receptor-expressing cells. Brain Res (2011) 1378:18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.01.010

61. Fujikawa T, Berglund ED, Patel VR, Ramadori G, Vianna CR, Vong L, et al. Leptin engages a hypothalamic neurocircuitry to permit survival in the absence of insulin. Cell Metab (2013) 18:431–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.08.004

62. De Rosa V, Procaccini C, Cali G, Pirozzi G, Fontana S, Zappacosta S, et al. A key role of leptin in the control of regulatory T cell proliferation. Immunity (2007) 26:241–55. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.01.011

63. Reis BS, Lee K, Fanok MH, Mascaraque C, Amoury M, Cohn LB, et al. Leptin receptor signaling in T cells is required for Th17 differentiation. J Immunol (2015) 194:5253–60. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402996

64. Mellott E, Faulkner JL. Mechanisms of leptin-induced endothelial dysfunction. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens (2023) 32:118–23. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000867

65. Johansson A, Lau J, Sandberg M, Borg LA, Magnusson PU, Carlsson PO. Endothelial cell signalling supports pancreatic beta cell function in the rat. Diabetologia (2009) 52:2385–94. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1485-6

Keywords: delta cells, beta-cell activity, leptin receptor (LEPR), differential expression (DE), mouse models, beta cells

Citation: Zhang J, Katada K, Mosleh E, Yuhas A, Peng G and Golson ML (2023) The leptin receptor has no role in delta-cell control of beta-cell function in the mouse. Front. Endocrinol. 14:1257671. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2023.1257671

Received: 12 July 2023; Accepted: 05 September 2023;

Published: 02 October 2023.

Edited by:

Sangeeta Dhawan, City of Hope National Medical Center, United StatesReviewed by:

Abdelfattah El Ouaamari, New York Medical College, United StatesMark O. Huising, University of California, Davis, United States

Amelia K. Linnemann, Indiana University Bloomington, United States

Copyright © 2023 Zhang, Katada, Mosleh, Yuhas, Peng and Golson. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Maria L. Golson, bWdvbHNvbjFAamhtaS5lZHU=

Jia Zhang1

Jia Zhang1 Maria L. Golson

Maria L. Golson