- 1School of Nursing, Peking University, Beijing, China

- 2Department of Social Medicine and Health Education, School of Public Health, Peking University, Beijing, China

- 3Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Peking University Third Hospital, Beijing, China

Background: Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) affects pregnancy outcomes and increases the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) postpartum. Traditional health education interventions have shown positive effects, but adherence to lifestyle management and motivation for continued postpartum care still require improvement. This study aimed to develop a comprehensive structured program for Chinese women with GDM to improve adherence to lifestyle management and motivation for postpartum care, thereby reducing future T2DM risk.

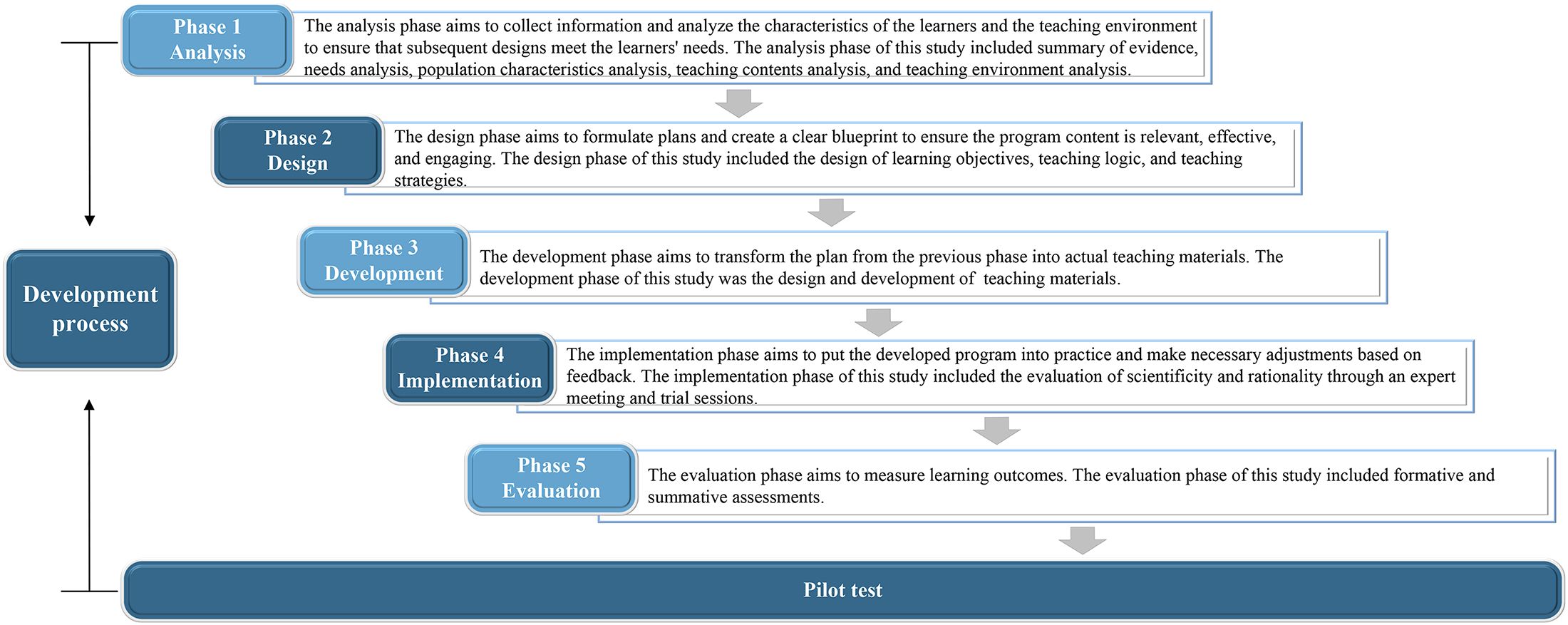

Methods: The development of this program was divided into five steps: (1) Analysis: a summary of evidence and the analysis of needs, population characteristics, teaching content, and teaching environment; (2) Design: the design of learning objectives, teaching logic, and teaching strategies; (3) Development: the creation and development of teaching materials; (4) Implementation: the evaluation of scientific validity and rationality through an expert meeting and trial sessions; (5) Evaluation: formative and summative assessments. Finally, a pilot test was conducted to evaluate its feasibility and acceptability.

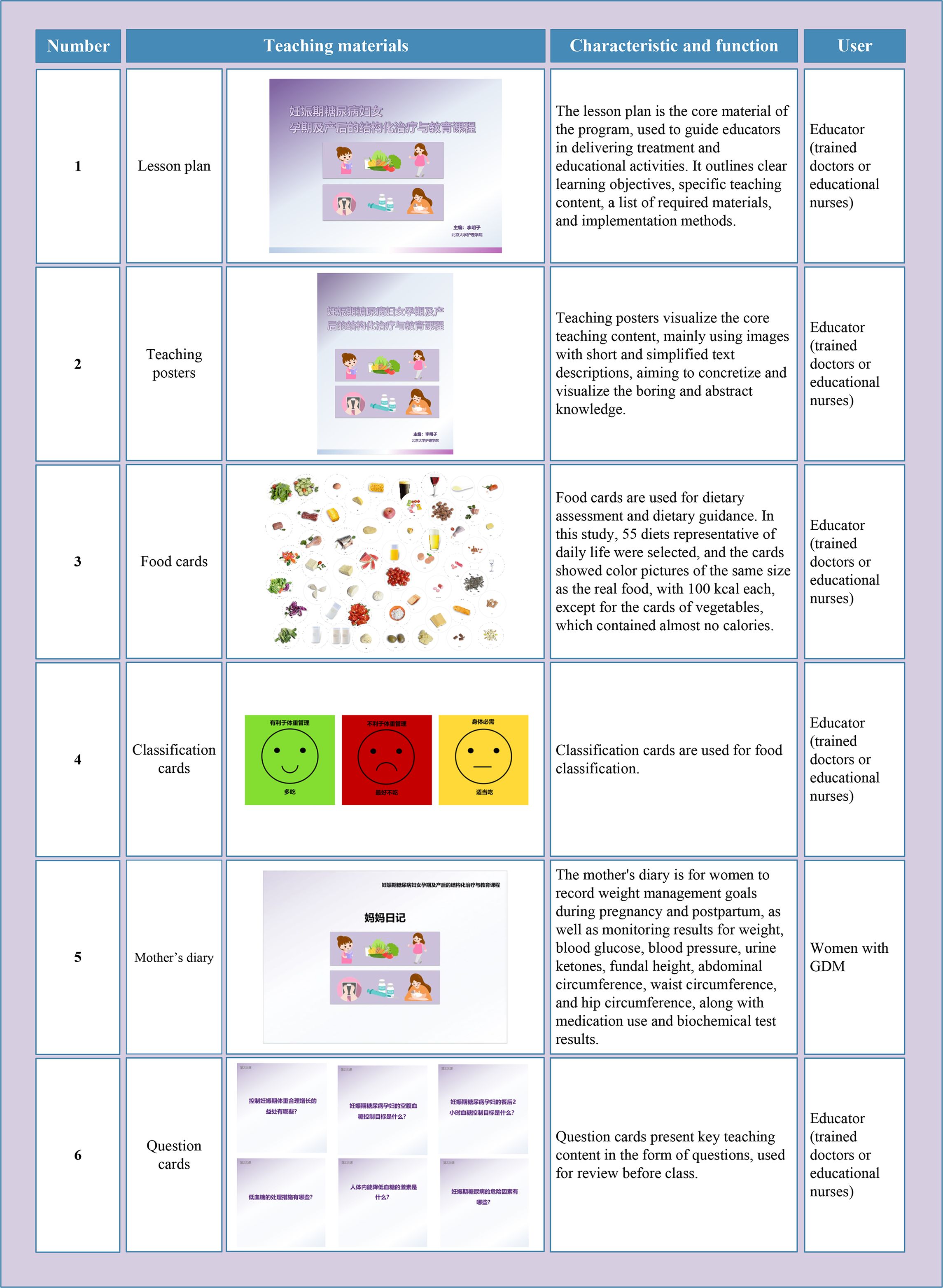

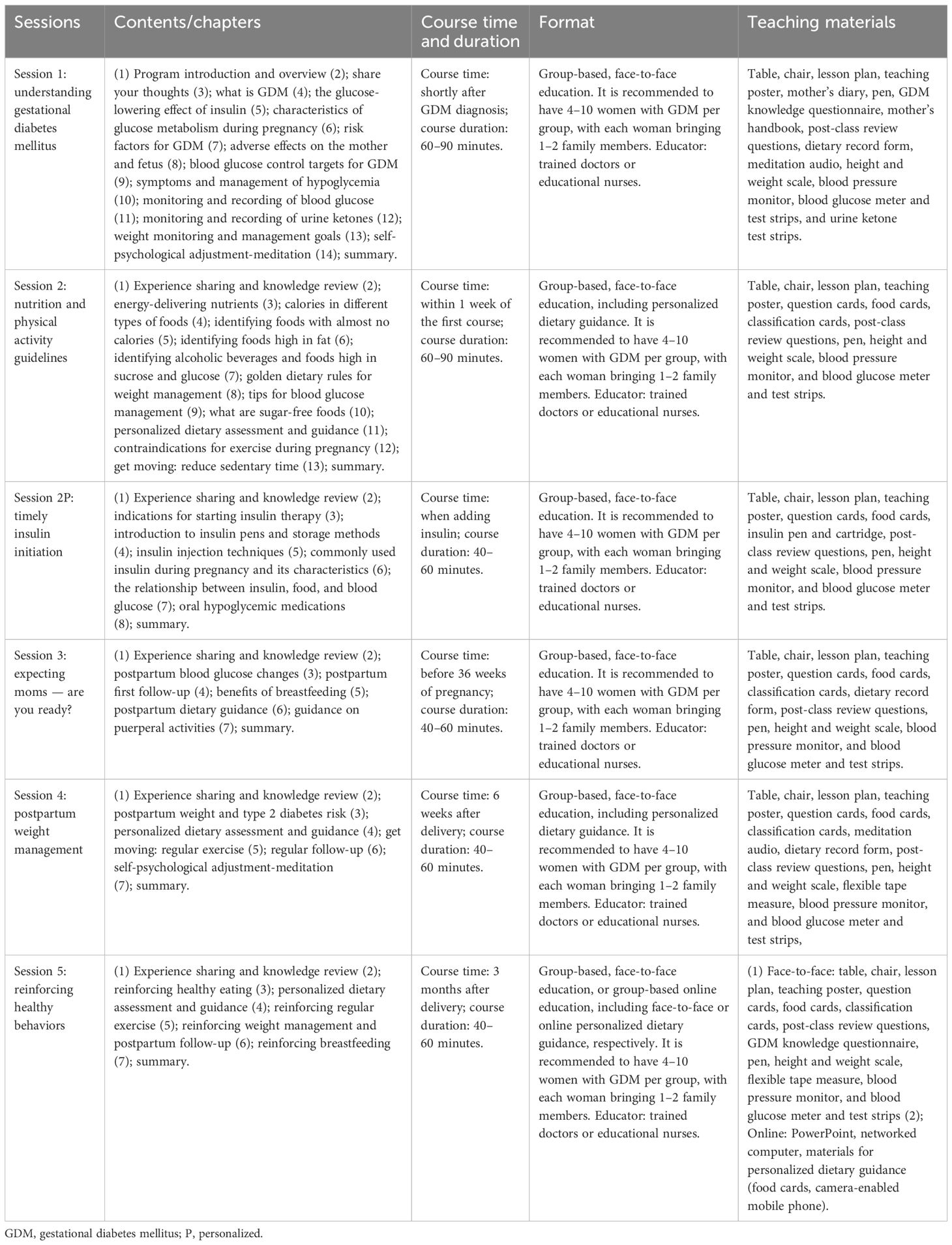

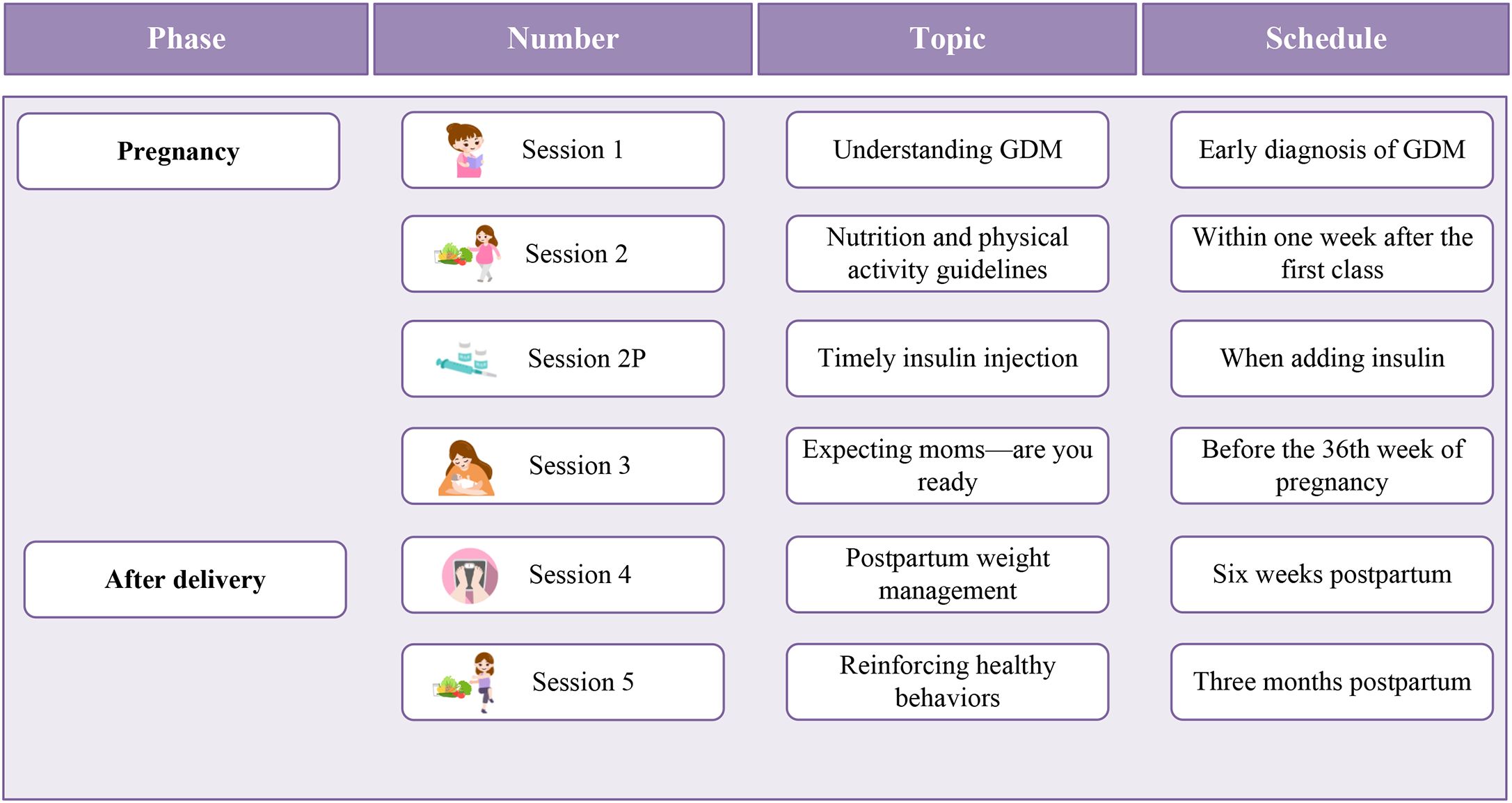

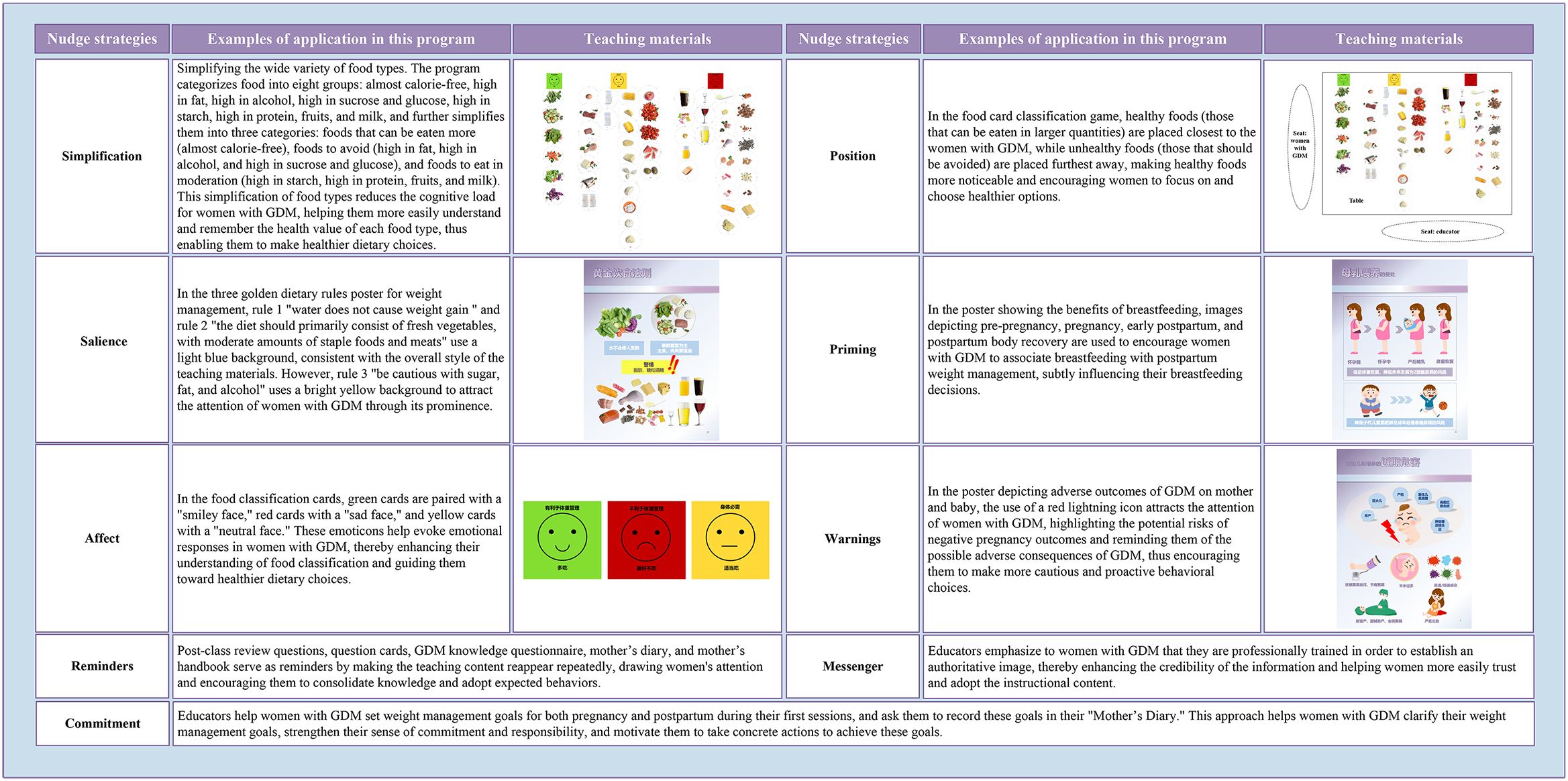

Results: Learning objectives were set in the cognitive, affective, and psychomotor domains, with a total of 189 items. The program consisted of five sessions, including: understanding GDM, nutrition and physical activity guidelines, expecting moms—are you ready, postpartum weight management, and reinforcing healthy behaviors. In addition, there was a session specifically for women starting insulin treatment, with the theme: timely insulin injection. Teaching materials included lesson plans, teaching posters, food cards, and a mother’s handbook, etc., totaling 11 items. The pilot study included eight women with GDM, all of whom expressed a positive acceptance of the program.

Conclusions: The feasibility and acceptability of the program were confirmed, and a final version was developed. It features clear objectives, detailed teaching content, engaging teaching materials, and standardized implementation processes, all of which are of significant importance for both short- and long-term management of GDM.

1 Introduction

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is defined by elevated blood glucose levels that first occur during pregnancy but do not meet the criteria for overt diabetes (1). In China, the prevalence of GDM increased from 4% in 2010 to 21% in 2020, and this trend is likely to persist due to economic development, lifestyle changes, and adjustments in fertility policies (2). GDM is not only associated with obstetric and neonatal complications but also serves as a significant risk factor for type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in affected women (3, 4). Therefore, effective management of GDM is essential for reducing both short- and long-term health risks. Lifestyle management is the cornerstone of GDM treatment (5). However, in many Chinese hospitals, GDM education is primarily delivered verbally, with its quality varying due to differences in healthcare providers’ knowledge. This approach lacks evidence-based, personalized, and systematic management. Since 2011, some hospitals in China have established one-day GDM clinics, which have shown positive effects on pregnancy outcomes (6, 7). However, the one-day clinic model does not sufficiently address long-term outcomes for women with GDM, highlighting the need for a continuous, integrated GDM program that covers both pregnancy and postpartum health risks.

Face-to-face, intensive, individualized or group-based lifestyle interventions are the most common and effective forms of GDM management (8, 9). While these programs produce positive short-term outcomes, their high cost and intensity pose challenges to long-term adherence after childbirth (10). Qualitative studies suggest that concerns about fetal health and the desire to avoid hypoglycemic medications often motivate lifestyle changes during pregnancy (11). However, these motivations often diminish postpartum, making it difficult to maintain a healthy lifestyle (12). Thus, future research should focus on behavioral theories that enhance motivation and adherence to lifestyle management during both pregnancy and postpartum, thereby improving long-term intervention effectiveness. Nudge refers to strategies such as designing choice frameworks and introducing subtle environmental cues to promote predictable behavioral changes while preserving individual autonomy (13). Nudge-based interventions have demonstrated positive outcomes in promoting healthy behavior (14, 15). Therefore, nudge strategies may effectively encourage women with GDM to adopt and maintain healthy behaviors and improve adherence to lifestyle management during pregnancy and postpartum. The Attention, Relevance, Confidence, and Satisfaction (ARCS) motivation model aims to stimulate, sustain, and reinforce behavioral motivation through the design of the teaching process (16). It has been widely applied in educational settings and has achieved significant results in enhancing learner motivation (17, 18). Hence, motivation-enhancing strategies based on this model may be effective in improving women’s motivation to adopt healthy behaviors.

A structured treatment and education program (STEP) is a patient education program that designs relevant content and procedures based on evidence, theory, and patient needs and organizes teaching activities and materials systematically using pedagogical principles (19). The program has clear learning objectives, standardized teaching methods, and customized teaching materials. It increases patient knowledge, skills, and motivation, improves health outcomes, and has been proven to be highly cost-effective (20, 21). Therefore, STEPs are evidence-based, systematic, personalized, and effective, showing great promise in addressing GDM management issues in China.

Therefore, this study aimed to develop an evidence-based, theory-driven STEP to address the existing gaps in GDM management in China. Through comprehensive care during pregnancy and postpartum, this project aims to support women with GDM in developing sustainable, healthy habits, thereby reducing their future metabolic risks. This study may also offer valuable insights to countries and regions facing similar challenges, contributing to the overall improvement of women’s health and well-being.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Principles of development

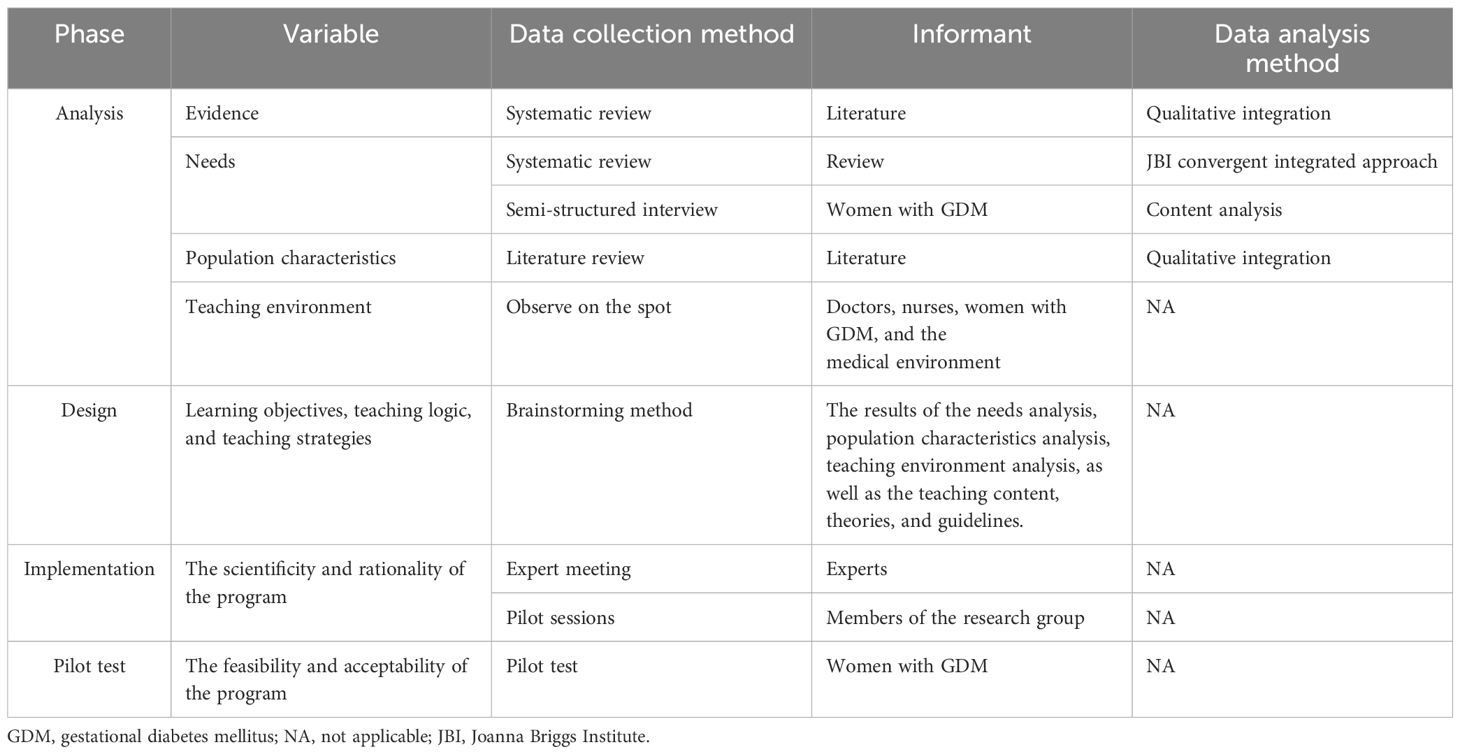

This study followed the Analysis, Design, Development, Implementation, and Evaluation (ADDIE) model for program development (22). The flow diagram of the development process is shown in Figure 1. The different methods of data collection and analysis used at different phases are summarized in Table 1. In addition, we also followed the Template for Intervention Description and Replication checklist and guide during the development process to ensure a complete description of the intervention (23).

2.2 Development process

2.2.1 Phase 1: analysis

The analysis phase comprised five components: evidence summary, needs analysis, population characteristics analysis, teaching content analysis, and teaching environment analysis.

2.2.1.1 Summary of evidence

In April 2023, we conducted a systematic search across 9 databases and 18 websites to identify clinical decisions, guidelines, recommended practices, evidence summaries, expert consensus, and systematic reviews related to lifestyle management for women with GDM. The detailed methodology is described in our previously published study (5).

2.2.1.2 Needs analysis based on a systematic review

We conducted a systematic review of PubMed, EMBASE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials to collect studies related to the needs and preferences of women with GDM. The search period was from the establishment of each database up to June 2023. Relevant references from these studies were also traced to gather additional related literature. Detailed search strategies are shown in Supplementary Table 1.

During the systematic review, two researchers (Jing Huang and Hua Li) independently screened the literature, assessed quality, and extracted data. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion with the third researcher (Yi Wu) until a consensus was reached. Inclusion criteria were based on the PICo framework: ① participants: women with GDM or a history of GDM; ② phenomena of interest: health education needs and preferences, with no restrictions on the literature type (qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-methods studies); ③ context: any setting (hospital, community, or home). Studies that were not available in full text, duplicates, or not published in English or Chinese were excluded.

The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Checklist for Qualitative Research was used to assess the quality of qualitative and mixed-methods studies’ qualitative components, while the JBI Critical Appraisal Instrument for Studies Reporting Prevalence Data was used for the quality of quantitative and mixed-methods studies’ quantitative components (24). Basic information and content on health education needs and preferences were extracted. Data were synthesized using the convergent integrated approach (25).

2.2.1.3 Needs analysis based on semi-structured interviews

Based on the philosophical foundation of naturalistic inquiry and the methodology of descriptive qualitative research, semi-structured interviews were conducted to confirm and expand the findings from the systematic review. Purposive sampling was used to identify eligible women to interview at the Outpatient Department of Peking University Third Hospital from September to October 2023. The inclusion criteria were: ① diagnosis of GDM; ② age ≥ 18 years; and ③ voluntary participation and informed consent. The exclusion criteria were: ① history of psychiatric disorders; ② cognitive, visual, or hearing impairments; and ③ severe organ dysfunction or physical disabilities. The interview outlines were: ① after being diagnosed with GDM, what kind of support do you feel you need? ② what are your preferences regarding the format and setting of health education? Pre-interviews with two women with GDM were conducted to assess the feasibility of the interview outline.

Basic information of the participants was collected through questionnaires. The researcher (Jing Huang) conducted the semi-structured interviews, and another researcher (Hua Li) audio-recorded the interviews with consent and took written notes. Interviews were conducted in a quiet patient education room and lasted 5–20 minutes each. Recordings were transcribed into written form within 24 hours and analyzed using NVivo 12.0 software. The content analysis method was used for data analysis (26).

2.2.1.4 The analysis of population characteristics and teaching contents

The population characteristics of women with GDM were analyzed through an extensive literature search in PubMed. During the literature search, we focused on studies that reported on sociodemographic characteristics, the current situation of self-management, and levels of social support among women with GDM, in order to gain a comprehensive understanding of the characteristics of this population. Then, the teaching contents were determined based on the results of needs analysis and population characteristics analysis.

2.2.1.5 The analysis of teaching environment

We conducted on-site visits to the obstetrics outpatient clinics and nutrition outpatient clinics of four tertiary hospitals in Beijing, China, to analyze the characteristics of the teaching environment by observing the current status of GDM management.

2.2.2 Phase 2: design

The design phase focused on developing a detailed teaching plan using the brainstorming method, including three key components: learning objectives, teaching logic, and teaching strategies. This was based on the guidelines, the results of needs analysis, population characteristics analysis and teaching environment analysis, teaching contents, motivation-enhancing and nudging strategies, and Knowles’ adult learning theory.

One week before the brainstorming meeting, the researcher (Jing Huang) provided the group members with printed materials related to the meeting, so that participants could familiarize themselves with the purpose and content of the meeting in advance. At the meeting, the researcher (Jing Huang) first introduced the goals of the meeting, including:

1. Identify teaching objectives: ① based on the Chinese Guideline of Diagnosis and Treatment of Hyperglycemia in Pregnancy, determine the overall goals of the program (27, 28); ② based on the analysis results of the needs, population characteristics, teaching environment, and teaching contents, using Bloom’s Taxonomy, identify the specific learning objectives of the program from the cognitive, affective, and psychomotor domains (29).

2. Identify teaching logic: considering the distinct psychological and physiological characteristics of women with GDM during pregnancy and postpartum, clarify the teaching logic by thoroughly understanding and analyzing the findings from the needs analysis and the analysis of population characteristics.

3. Identify teaching strategies: ① at the macro level, in order to improve the adherence and motivation among women with GDM during pregnancy and postpartum in managing their lifestyle, determine nudge strategies that contribute to lifestyle management adherence and promote the achievement of the learning objectives based on the Ten Important Nudges, the TIPPME (Typology of Interventions in Proximal Physical Micro-Environments), and the MINDSPACE (Messenger, Incentives, Norms, Defaults, Salience, Priming, Affect, Commitment, and Ego) frameworks (30–32), and identify motivation-enhancing strategies that contribute to strengthen both learning and lifestyle management motivation based on the attention, relevance, confidence, and satisfaction strategies in the ARCS motivation model; ② determine the teaching strategies at the micro level based on Knowles’ theory of adult learning (33).

Then, the researcher emphasized that group members should actively participate in discussions, with no right or wrong answers, and no arbitrary criticism or interruption of others’ speech. The researcher was also responsible for controlling the meeting time and progress. Another researcher (Tianxue Long) audio-recorded the meeting with consent and took written notes. Before concluding the discussion on each issue, the researcher (Jing Huang) summarized the discussion points and asked if there were any additions. If no new content emerged, the meeting moved to the next issue until all topics were covered. Finally, the facilitator and the recorder summarized and organized the content determined during the meeting, forming the program’s learning objectives, teaching logic, and teaching strategies.

2.2.3 Phase 3: development

Based on the population characteristics, needs, teaching environment, teaching contents, learning objectives, teaching logic, teaching strategies, evidence summaries, relevant authoritative literature and books, and the STEP previously developed by our research team for patients with T2DM, the first draft of the teaching materials was designed and developed in collaboration with a graphic design professional (34).

2.2.4 Phase 4: implementation

2.2.4.1 Expert meeting

After the first draft was constructed, an expert meeting was conducted to assess the scientificity (adherence to guidelines and clinical practices) and rationality (alignment with typical medical visits and follow-up routines for women with GDM) of the program. Expert selection criteria included: ① a Master’s degree or higher; ② an intermediate or senior professional title; and ③ voluntary participation. Experts’ basic information was collected through information forms. Before the meeting started, each expert was provided with a printed structured checklist and a tablet loaded with all the teaching materials for evaluation and review during the meeting. During the expert meeting, the researcher (Jing Huang) introduced the program’s development process and content to the experts. Then, the experts were free to review the materials on the tablet, and the researcher invited them to provide suggestions based on the structured checklist. The suggestion was adopted when the experts reached a consensus on it, and the meeting ended when no new suggestions were made. To ensure transparency and accuracy, another researcher (Tianxue Long) audio-recorded the meeting with consent and took written notes. Within 24 hours, the suggestions were summarized into a written document. Based on the feedback from the expert meeting and internal discussions within the research team, revisions were made, resulting in the development of a second version.

2.2.4.2 Trial session

Based on the second version, trial sessions were conducted. Research team members role-played women with GDM and interacted with the educator (Jing Huang). The basic information of the research team members was collected through a questionnaire. After each trial session, suggestions from the team were collected, and any suggestion that reached a consensus was adopted. Another researcher (Tianxue Long) audio-recorded the discussion with consent and took written notes. The recordings were summarized and organized into a written document within 24 hours. The program was revised based on the feedback, followed by another trial session, continuing this cycle until no new suggestions emerged. After all trial sessions and revisions, the third version was finalized.

2.2.5 Phase 5: evaluation

The evaluation of the program consisted of both formative and summative assessments. Formative assessment was conducted throughout the program, focusing on the use of teaching materials, classroom interactions, and completion of assignments. Summative assessment was performed at the end of the program, evaluating cognitive, affective, and psychomotor outcomes. In addition, health changes in women with GDM were assessed using objective indicators.

2.3 Pilot test

We conducted a pilot test of the third version in the obstetric outpatient department of a tertiary hospital in Beijing to explore its feasibility (whether the program could be successfully implemented in the clinic) and acceptability (attitudes and responses of women with GDM to the program). Inclusion criteria were: ① diagnosis of GDM according to the Chinese guideline for the diagnosis and management of hyperglycemia in pregnancy (2022) (28); ② age ≥ 18 years; ③ singleton intrauterine pregnancy; ④ ability to understand Mandarin; and ⑤ voluntary participation. Exclusion criteria were: ① history of mental illness; ② cognitive, visual, or hearing impairment; ③ serious organ damage or physical disability; ④ abnormal pregnancy conditions such as placental abruption or placenta previa; and ⑤ concurrent participation in other studies.

Obstetric physicians recruited eligible women with GDM, one researcher (Hua Li) coordinated participant enrollment, and another researcher (Jing Huang) conducted the sessions. All sessions were held in the patient education room, with each session involving one woman. After the session, feedback was collected using the question, “What do you think of the content and format of this session?” The researcher (Hua Li) audio-recorded the feedback with consent and took written notes. The recordings were summarized and organized into a written document within 24 hours. In addition, we collected participants’ pregnancy weight gain and postpartum blood glucose through the medical record system.

2.4 Ethical considerations

This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committees of the Peking University Health Science Center (IRB00001052-23063; July 3rd, 2023) and Peking University Third Hospital (IRB00006761-M2023463; August 14th, 2023). All women with GDM provided written informed consent, and all data were kept confidential and anonymous.

3 Results

3.1 Development process

3.1.1 Phase 1 analysis

3.1.1.1 The results of evidence summary

A total of 12,196 records were retrieved, 55 articles were included in the analysis, and 69 pieces of evidence were summarized. The flowchart of the literature screening, the results of the quality assessment, and the evidence extraction form can be found in our previously published article (5).

3.1.1.2 The results of needs analysis

In the systematic review, a total of 379 records were initially retrieved. Ten articles were included in the data analysis, of which 5 were qualitative studies, 4 were quantitative studies, and 1 was a mixed-methods study. The flowchart of the literature screening is shown in Supplementary Figure 1, the results of the quality assessment of the articles are shown in Supplementary Tables 2 and 3, and the basic characteristics of the included studies are presented in Supplementary Table 4. The results of the needs and preferences in the systematic review are shown in Supplementary Table 5. In the interviews, we conducted interviews with 21 women with GDM, and their basic information is provided in Supplementary Table 6. The results of the needs and preferences in the interviews are shown in Supplementary Table 7.

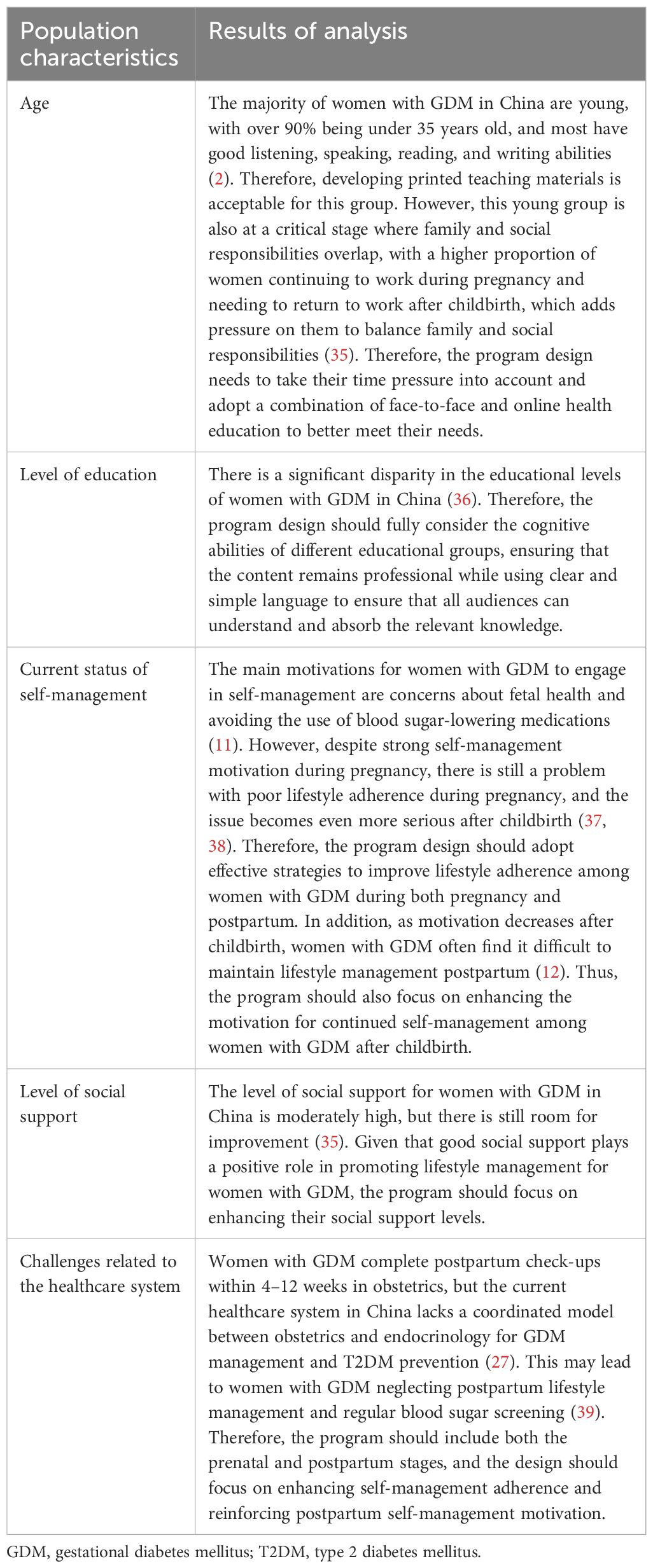

3.1.1.3 The results of the analysis of population characteristics

Based on the analysis of population characteristics, the program design should consider the cognitive abilities of different educational groups, combining both face-to-face and online education to alleviate women’s time pressures. It should also adopt effective strategies to improve adherence to lifestyle management, enhance motivation for postpartum management, strengthen social support, and include comprehensive management throughout both the prenatal and postpartum periods. The detailed results are shown in Table 2.

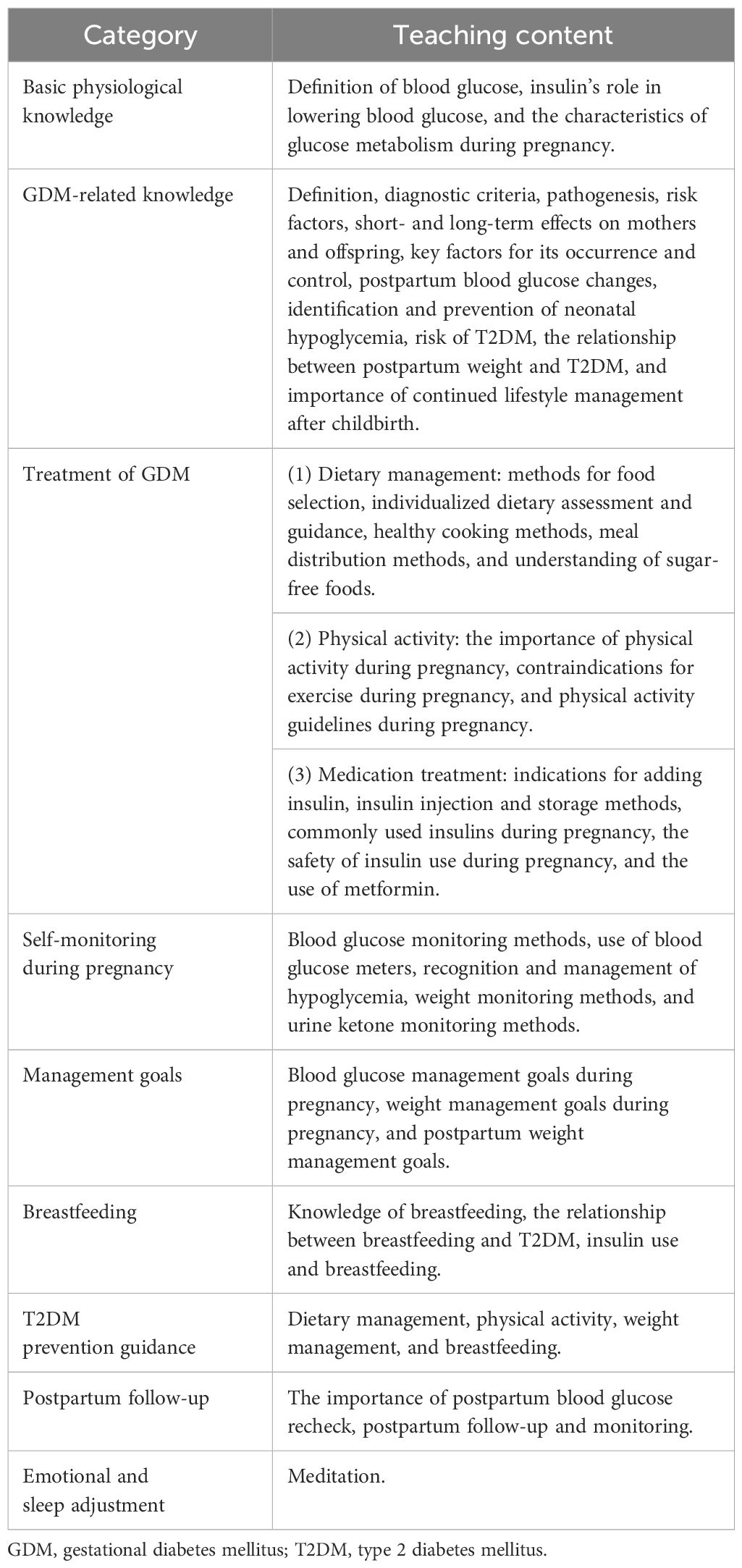

3.1.1.4 The results of the analysis of teaching content

Based on the population characteristics and needs analysis of women with GDM, the teaching content was determined, as shown in Table 3.

3.1.1.5 The results of the analysis of teaching environment

According to the requirements of basic public health services in China, pregnant women are required to visit hospitals for registration and management, and all levels of hospitals provide registration and management services for pregnant women. The prenatal examination and postpartum follow-up for women with GDM are completed at outpatient clinics, and hospitalization is not needed if no abnormalities are found. Lifestyle management such as dietary adjustments, physical activity, and weight control is generally carried out by the women themselves or with family support at home. Therefore, program design should consider the availability of teaching resources at different hospital levels and the practicality of the knowledge and skills for home environment application.

3.1.2 Phase 2 design

In the design phase, 7 members of the research team participated in a brainstorming meeting. The basic information of the group members is shown in Supplementary Table 8. During the brainstorming session, the teaching logic was clarified, learning objectives were established, and teaching strategies were determined. The analysis approach and results for these steps are as follows.

3.1.2.1 The results of the design of teaching logic

Based on the brainstorming meeting, through the analysis of the population characteristics and needs of women with GDM, we found that most lack knowledge and skills for self-management during pregnancy. They are concerned about the potential harm of hyperglycemia to the fetus and urgently need to acquire self-management knowledge and skills. In the postpartum period, the blood glucose levels of most women return to normal due to hormonal changes, leading them to overlook the long-term impacts of GDM. Further, the current clinical management model in China provides insufficient postpartum support, which may exacerbate unhealthy lifestyle behaviors. Therefore, prenatal sessions should focus on helping women quickly acquire self-management knowledge and skills while increasing their awareness of long-term health risks. Postpartum sessions should emphasize continued self-management after childbirth and reinforce the learned knowledge and skills. Based on the logic, we designed five sessions, as detailed in Figure 2. Among them, the personalized session was developed specifically for women who start insulin treatment.

Figure 2. The results of the design of teaching logic. GDM, Gestational diabetes mellitus; P, personalized.

3.1.2.2 The results of the design of learning objectives

According to the brainstorming meeting, the overall goal of the program was to assist women with GDM in acquiring the knowledge and skills necessary for self-management, improving self-management behaviors and metabolic control, enhancing pregnancy outcomes, and reducing the risk of developing T2DM. The specific learning objectives were based on the characteristics and needs of the GDM population as well as the teaching content and in accordance with Bloom’s Taxonomy. The cognitive domain included 103 objectives, the psychomotor domain included 66 objectives, and the affective domain included 20 objectives, as detailed in Supplementary Table 9.

3.1.2.3 The results of the design of teaching strategies

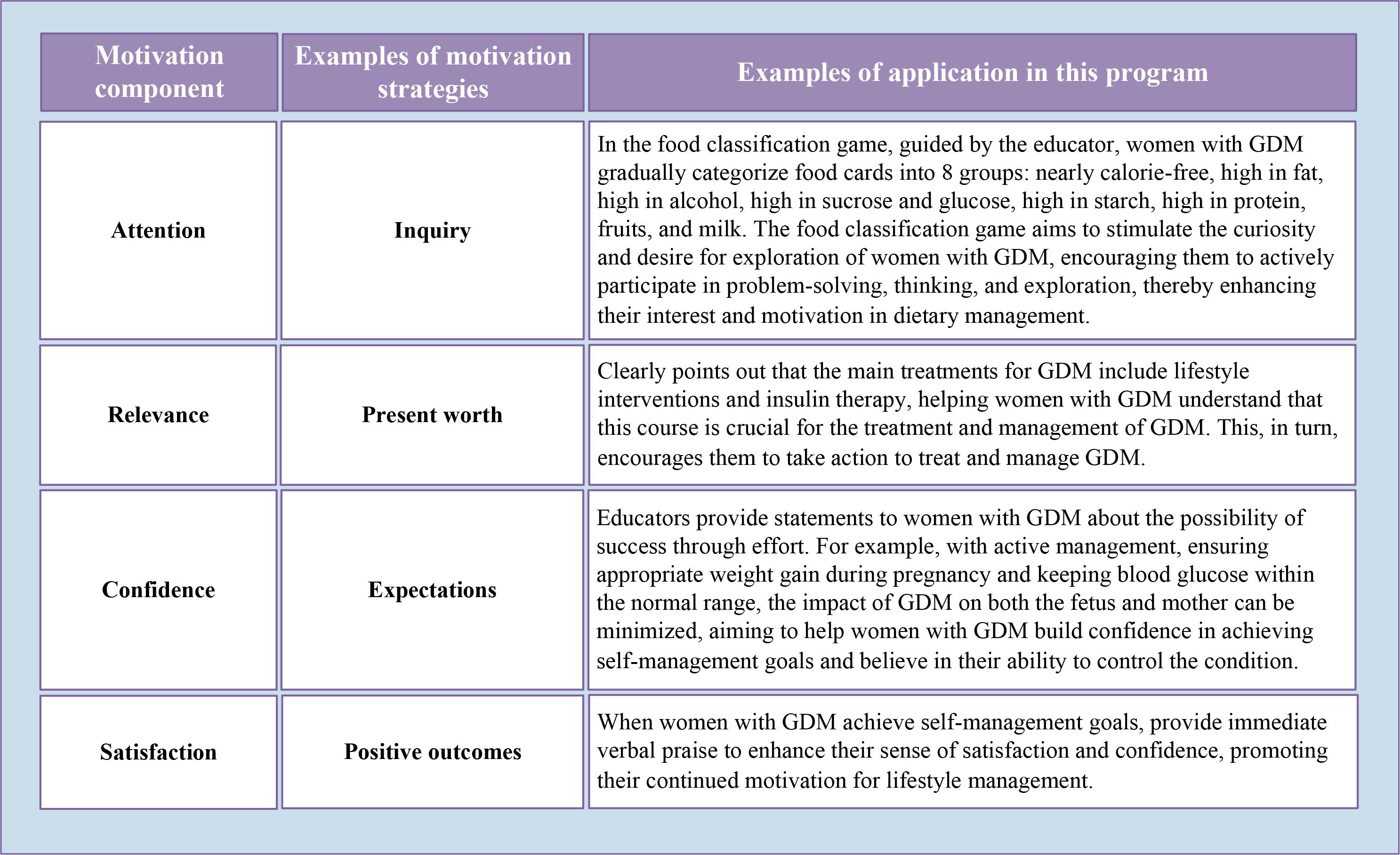

Based on the brainstorming meeting, at the macro level, the nudge strategies applied in this program included messenger, simplification, salience, affect, position, priming, commitment, warnings, and reminders, while the motivational enhancement strategies included attention, relevance, confidence, and satisfaction. Figures 3 and 4 provide examples of these strategies, detailed in Supplementary Tables 10 and 11.

Figure 3. Examples of the application of nudge strategies in the program. GDM, Gestational diabetes mellitus.

Figure 4. Examples of the application of motivation-enhancing strategies in the program. GDM, Gestational diabetes mellitus.

At the micro level, this program combined group-based teaching with individualized guidance. Group education encourages active participation and discussion, while individualized guidance addresses specific needs. To ensure full participation in discussions and to raise personalized questions, the group size was limited to 10 participants. The program utilized various teaching strategies, including lectures, questions and answers, discussions, demonstrations, games, exercises, and assignments, promoting a problem-centered learning process. One to two family members were recommended to participate in each session. Each session began with experience sharing and a knowledge review, and ended with assignments and distribution of educational materials aligned with the teaching content. The assignments included self-management tasks, such as self-monitoring of blood glucose, urine ketones, weight, and diet. Sessions were primarily in-person, but Session 5 included a PowerPoint for online participation due to postpartum time pressures. The program was implemented by trained doctors or education nurses.

3.1.3 Phase 3 development

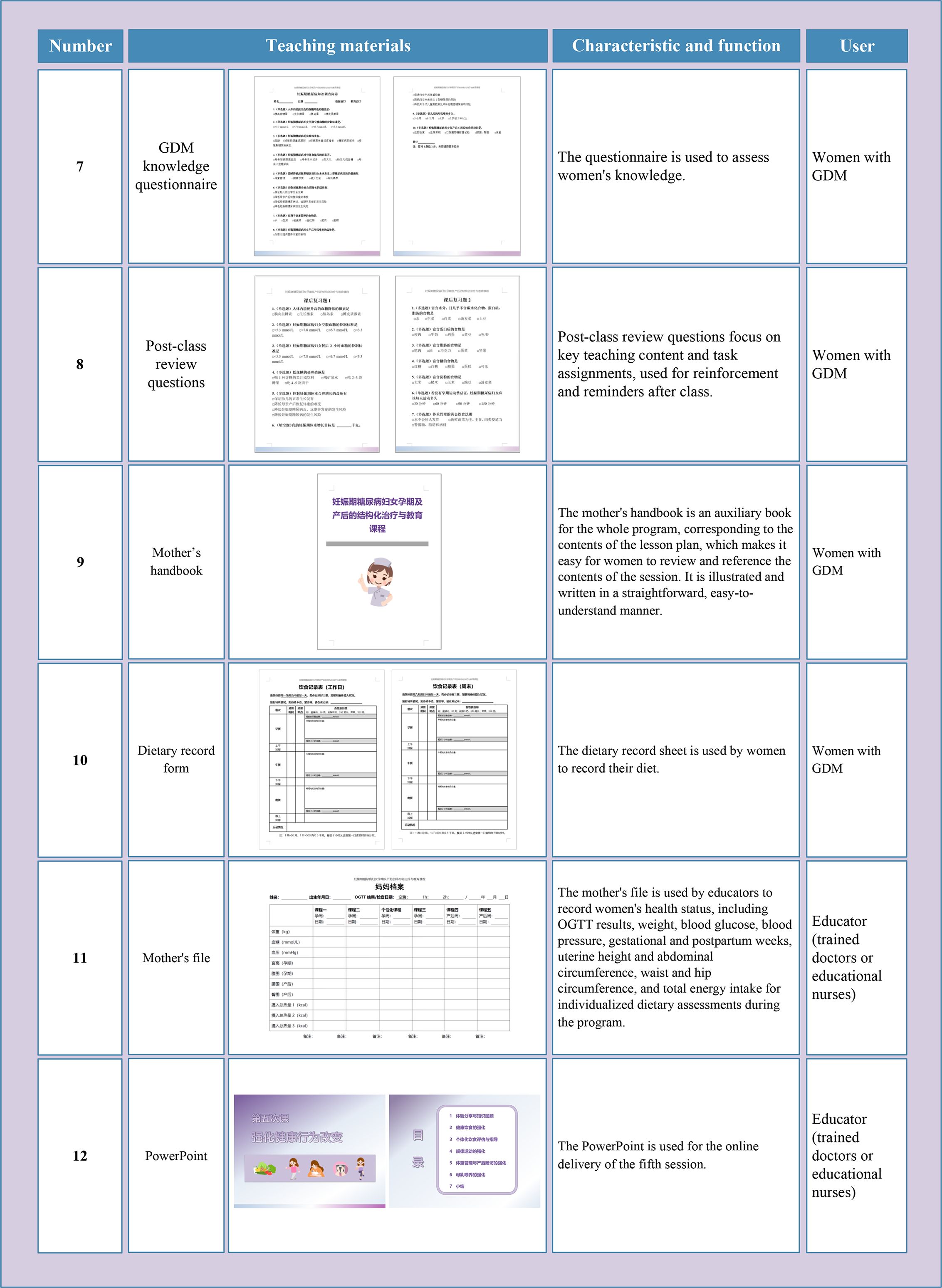

The developed teaching materials were in paper format, portable, and can be used in any setting. All teaching materials were printed in color, with vivid and engaging content that is easy for women with GDM from various educational backgrounds to understand and accept. Specific items for teaching materials are shown in Figures 5 and 6.

Figure 6. The teaching materials developed in this study (B). GDM, Gestational diabetes mellitus; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test.

3.1.4 Phase 4 implementation

3.1.4.1 Expert meeting

After the first draft was formed, this study invited 6 experts from the fields of obstetrics, nutrition, public health, chronic disease management, and psychology to participate in an expert meeting. The basic characteristics of the experts are shown in Supplementary Table 12. The meeting lasted for one hour, and the summary of the experts’ suggestions is shown in Supplementary Table 13.

3.1.4.2 Trial session

After revising the teaching materials based on the experts’ opinions, 7 members of the research team participated in the trial sessions, and the basic information of the group members is shown in Supplementary Table 8. During the trial, one researcher (Jing Huang) served as the educator, while the remaining 6 team members played the role of women with GDM and interacted with the educator. After each trial, the program was improved based on feedback from the team members and retaught until no new suggestions were made. The trial process and feedback are provided in Supplementary Table 14.

3.1.5 Phase 5 evaluation

Formative assessment included aspects such as the use of the mother’s diary, responses to questions, and completion of post-class review exercises. Summative assessment involved evaluation in the cognitive domain using the GDM knowledge questionnaire, assessment in the psychomotor skills domain through food frequency questionnaires and pregnancy physical activity questionnaire, and evaluation in the affective domain using diabetes management self-efficacy scale, regulation of eating behaviors scale, and perceived social support scales. Moreover, health changes were assessed through objective indicators such as weight, blood glucose, blood lipids, waist circumference, hip circumference, and glycated hemoglobin.

3.2 Pilot test

In March 2024, 8 women with GDM participated in the pilot study, and the basic information of the participants is provided in Supplementary Table 15. For women shortly after the diagnosis of GDM (24–30 weeks), we provided sessions 1 and 2; for women using insulin, we offered session 2P (personalized); for women in the later stages of pregnancy (32 to 36 weeks), we provided session 3; and for postpartum women attending follow-up, we provided session 4. Since the purpose of session 5 is reinforcement and its content was learned previously, it was not delivered to the participants.

Among the 6 participants who attended the pregnancy session, 4 women had appropriate weight gain during pregnancy, while 2 women gained excessive weight. Among the 8 participants, 7 women underwent an OGTT within 4–12 weeks postpartum. The pregnancy weight gain and postpartum blood glucose of participants are shown in Supplementary Table 15. The interview found that women with GDM highly endorsed the program and believed it contributed to improving their disease-related knowledge and their self-management knowledge and skills. No further suggestions or revisions were provided by the participants, and the feedback is shown in Supplementary Table 16. At this point, the final version of the program is built. The description and design of the program are shown in Table 4, the printed version is presented in Supplementary Figure 2.

3.3 Implementation cost estimates and time requirements

The estimated implementation costs for this program include: ① wage costs (salaries for the trainers and the doctors or nurses involved in the training and implementation of the program); ② material costs (printing fees for teaching materials, estimated at 806 RMB per set for this program, with an additional 44 RMB for each additional woman with GDM participating); ③ transportation costs (postage costs for the teaching materials); ④ travel costs (travel expenses for the trainers). The time requirements for implementing this program include: ① the time for trainers and doctors or nurses to participate in training and assessment (training session time: 420 minutes; assessment session time: 420 minutes*number of doctors or nurses participating in training); ② the time for doctors or nurses to officially implement the program (420 minutes for 4–10 women with GDM). Decision-makers can refer to our cost and time estimates, and based on local wages, postage, and transportation conditions, estimate the possible costs of implementing the project locally.

4 Discussion

This study designed and developed a STEP during pregnancy and the postpartum period for women with GDM in China, and this article outlines all stages of its development. The program consists of five educational sessions that are strategically mapped and ordered to align with and achieve the program’s objectives, including systematic teaching materials such as lesson plans that ensure the quality and standardization of the educational process, vivid and engaging teaching posters, patient handbooks that correspond to the lesson plans, food cards for 55 common foods, question cards for pre-class review, post-class review exercises, and diaries to support self-management for women. The results of the pilot test showed that the program was well accepted among women with GDM, enhanced their relevant knowledge and skills, and had a positive impact on weight management and postnatal blood glucose screening. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive and structured program designed to manage GDM and prevent T2DM among Chinese women.

Dietary management is a crucial component of lifestyle intervention for GDM. Guidelines from multiple countries recommend that women with GDM control their total caloric intake and optimize the macronutrient balance of carbohydrates, proteins, and fats to regulate blood glucose, weight gain, and improve pregnancy outcomes (5). A review of previous studies found that dietary guidance for women with GDM primarily relies on precise energy calculations and food weighing (8, 9). This method is associated with a high cognitive load in dietary management, which can lead to negative effects such as distress, postpartum dietary indulgence, and poor adherence (40). In this program, we aim to help women make healthier dietary decisions in daily life by providing concise dietary guidance materials, easy-to-understand educational posters, and practical dietary recommendations that are easy to follow and implement. For example, this program provides dietary guidance to women with GDM based on food cards. After the educator shows all the food cards needed for the day, the women can visually understand the types and portions of food required for the day (the food size of 100 kcal displayed on the cards is equivalent to the actual size of the food). After returning home, they only need to follow the food types and portion sizes on the food cards without needing to perform additional caloric calculations or weighing. This simplified food quantification method helps reduce the cognitive load, thereby improving adherence to dietary management. In addition, the motivation-enhancing strategy not only boosts the motivation for course learning but also focuses on enhancing the motivation for continued postpartum lifestyle management, which helps promote the development of healthy dietary habits among women with GDM. Therefore, compared to traditional dietary guidance, the dietary guidance in this study integrates both nudge strategies and motivation-enhancing strategies, not only conveying dietary knowledge but also focusing on improving dietary management adherence and motivation, which will have a positive impact on the lifelong metabolic health of women with GDM.

Previous studies have identified inadequate guidance from healthcare providers as a barrier to effective self-management among women with GDM. Ge et al. conducted interviews with Chinese women with GDM and found that some perceived healthcare advice as overly basic and lacking depth (41). Similarly, Hui et al. also interviewed women with GDM in Nepal and found that some of them felt that dietary advice was too general and that they desired more guidance (42). High-quality patient education requires a systematic and reliable instructional design model. The ADDIE model is one of the most commonly used models for instructional design, which has been widely used in the development and design of curricula in many fields such as school education, medical education, and corporate training (43, 44). This program employed this model as its framework, ensuring the integrity and high quality of the development process through meticulous design and implementation across the five key phases of analysis, design, development, implementation, and evaluation. The program is implemented by trained doctors or education nurses, using standardized lesson plans, clear learning objectives, specific teaching content, and detailed teaching materials and implementation methods, which ensures the standardization of the implementation process. The lesson plans contain the key phrases of the teaching content, allowing trained doctors and nurses to deliver the program according to the prompts, which ensures the accuracy of the content and the smoothness of the teaching process to the greatest extent possible. Therefore, even in under-resourced hospitals or clinics, the program can be effectively delivered after appropriate training, based on systematic teaching materials and standardized teaching processes. In addition, with the rapid development of information technology, future postpartum support could integrate information technology-based follow-up methods (such as mobile applications or WeChat-based reminders) as a solution to improve resource efficiency and promote long-term health management and follow-up. Future studies could integrate digitalization and intelligent management into this program, thereby more effectively enhancing women’s health throughout their entire life cycle.

Based on the analysis of the needs, population Characteristics, and teaching environment, we recommend that 1~2 family members attend the classes with the woman with GDM. Women with GDM interviewed by Wah et al. reported support from husbands, parents, and in-laws, such as help preparing meals and reminders about healthy eating (45). However, Dennison et al. and Teh et al. found that some women face resistance when preparing healthy meals because family members believe that healthy eating is not in line with traditional food culture or personal preferences (40, 46). Therefore, good social support plays a positive role in lifestyle management for women with GDM, but insufficient social support is a significant barrier. The family participation model designed by this program aims to increase family members’ understanding of GDM management and promote joint participation in lifestyle management, thus creating a more supportive environment.

Currently, lifestyle intervention programs for women with GDM mainly include face-to-face individual/group health education, remote education or counseling via phone, text messages, or emails, and digital therapies based on mobile apps (10, 47, 48). Compared to these previous interventions, the program developed in this study has the following positive aspects. In terms of objectives, it not only focuses on health management during pregnancy, but also on reducing the risk of T2DM in the long term; in terms of theoretical basis, it pays more attention to the pedagogical principles of curriculum design, activation of self-management motivation, and improvement of self-management adherence; in terms of teaching logic, it pays more attention to the continuity of health management during pregnancy and postpartum; in terms of teaching strategies, it pays more attention to the active participation of women with GDM and joint participation of their families; in terms of program development, it pays more attention to building systematic and standardized teaching materials based on the needs and evidence-based evidence. The program developed in this study considered the strengths and weaknesses of previous lifestyle intervention studies for women with GDM and addressed the current lack of systematic, personalized, effective, and sustainable approaches to GDM management in China.

However, this study also has some limitations. First, in the needs analysis, this study conducted a systematic review to comprehensively determine the health education needs and preferences of women with GDM. However, the semi-structured interviews, which aimed to confirm and expand the findings from the systematic review, were conducted only at a tertiary hospital in Beijing, China. Women in hospitals of different levels and regions may differ in terms of economic status, cultural habits, and educational levels, which may lead to varying needs for them, thus affecting the representativeness of the results of needs analysis. Nonetheless, this limitation may have little impact on the results of the study, as the results of the needs analysis based on the systematic review were comprehensive. Second, the pilot test was conducted only in a tertiary hospital in Beijing, with a sample size of only 8 cases, and participants were predominantly undergraduate or above. Participants from resource-intensive tertiary hospitals may have access to more advanced and abundant medical resources, which could cause the study results to reflect feedback more from high-resource settings. Moreover, individuals with higher education levels generally have better information comprehension abilities and higher socioeconomic status, which could make them more receptive to the program and more capable of applying the knowledge they acquire. Therefore, the sample of the pilot test may not fully represent the general situation of women with GDM from hospitals of different levels and with various educational backgrounds. Despite this, when constructing this program, we considered its applicability for women with different educational backgrounds and hospitals of different levels through population characteristics analysis and teaching environment analysis, aiming to ensure that even hospitals or clinics in under-resourced areas can effectively implement the program based on systematic teaching materials and standardized teaching procedures. Furthermore, the pilot test did not conduct a quantitative analysis, and the explanatory power of the qualitative data may be limited. Therefore, to improve the generalizability of this program, future research should consider conducting multi-center trials for broader validation across different levels of hospitals and among populations with varying educational backgrounds. Of note, a multicenter randomized controlled trial for the formal implementation of this program is underway (ChiCTR2400081700). Once completed, feedback from researchers and participants will be collected, and any suggestions for program modifications will be considered.

5 Conclusion

This study developed an evidence−based, theory−driven STEP tailored for women with GDM in China. The program features clear learning objectives, concise and comprehensive content, clear and vivid teaching materials, and a standardized educational process, making it easy for educators to deliver and for women with GDM to understand. This design also facilitates the promotion and replication of the program, providing practical resources and tools for the health management of women with GDM during pregnancy and postpartum, and has significant potential to promote their health throughout the life cycle. The pilot test demonstrated the feasibility and acceptability of the program, making it worthy of further clinical validation and dissemination.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committees of the Peking University Health Science Center (IRB00001052-23063; July 3rd, 2023) and Peking University Third Hospital (IRB00006761-M2023463; August 14th, 202). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

JH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. TL: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. HL: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. HC: Investigation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. DZ: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. YW: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. YYZ: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. XS: Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. YZ: Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. YW: Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. ML: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number: 72074008), the International Institute of Population Health of Peking University Health Science Center Fund (grant number: JKCJ202304), and the Peking University Nursing Discipline Research and Development Fund (grant number: LJRC23YB03).

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank all the experts who participated in the expert meeting for their professional guidance on this project. We also appreciate the staff of the Obstetrics Department at Peking University Third Hospital for their assistance during the pilot phase of this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fendo.2025.1627702/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Figure 1 | PRISMA Flow Diagram.

Supplementary Figure 2 | The printed version of the program.

References

1. Sweeting A, Hannah W, Backman H, Catalano P, Feghali M, Herman WH, et al. Epidemiology and management of gestational diabetes. Lancet. (2024) 404:175–92. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00825-0

2. Zhu H, Zhao Z, Xu J, Chen Y, Zhu Q, Zhou L, et al. The prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus before and after the implementation of the universal two-child policy in China. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). (2022) 13:960877. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.960877

3. Sweeting A, Wong J, Murphy HR, and Ross GP. A clinical update on gestational diabetes mellitus. Endocr Rev. (2022) 43:763–93. doi: 10.1210/endrev/bnac003

4. Vounzoulaki E, Khunti K, Abner SC, Tan BK, Davies MJ, and Gillies CL. Progression to type 2 diabetes in women with a known history of gestational diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis. Bmj. (2020) 369:m1361. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1361

5. Huang J, Wu Y, Li H, Cui H, Zhang Q, Long T, et al. Weight management during pregnancy and the postpartum period in women with gestational diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and summary of current evidence and recommendations. Nutrients. (2023) 15:5022. doi: 10.3390/nu15245022

6. Cao YM, Wang W, Cai NN, Ma M, Liu J, Zhang P, et al. The impact of the one-day clinic diabetes mellitus management model on perinatal outcomes in patients with gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. (2021) 14:3533–40. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S316878

7. Yan J and Yang H. Gestational diabetes in China: challenges and coping strategies. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. (2014) 2:930–1. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(14)70154-8

8. Ural A and Kizilkaya Beji N. The effect of health-promoting lifestyle education program provided to women with gestational diabetes mellitus on maternal and neonatal health: a randomized controlled trial. Psychol Health Med. (2021) 26:657–70. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2020.1856390

9. Zhang Y, Han Y, and Dong Q. The effect of individualized exercise prescriptions combined with dietary management on blood glucose in the second-and-third trimester of gestational diabetes mellitus. Am J Transl Res. (2021) 13:7388–93.

10. Shek NW, Ngai CS, Lee CP, Chan JY, and Lao TT. Lifestyle modifications in the development of diabetes mellitus and metabolic syndrome in Chinese women who had gestational diabetes mellitus: a randomized interventional trial. Arch Gynecol Obstet. (2014) 289:319–27. doi: 10.1007/s00404-013-2971-0

11. Neufeld HT. Food perceptions and concerns of aboriginal women coping with gestational diabetes in Winnipeg, Manitoba. J Nutr Educ Behav. (2011) 43:482–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2011.05.017

12. Eades CE, France EF, and Evans JMM. Postnatal experiences, knowledge and perceptions of women with gestational diabetes. Diabetes Med. (2018) 35:519–29. doi: 10.1111/dme.13580

13. Thaler RH and Sunstein CR. Nudge: improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press (2008).

14. Thorndike AN, Riis J, Sonnenberg LM, and Levy DE. Traffic-light labels and choice architecture: promoting healthy food choices. Am J Prev Med. (2014) 46:143–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.002

15. Yamada Y, Uchida T, Sasaki S, Taguri M, Shiose T, Ikenoue T, et al. Nudge-based interventions on health promotion activity among very old people: A pragmatic, 2-arm, participant-blinded randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc. (2023) 24:390–4.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2022.11.009

16. Keller JM. Development and use of the ARCS model of instructional design. J instructional Dev. (1987) 10:2–10. doi: 10.1007/BF02905780

17. Li K and Keller JM. Use of the ARCS model in education: A literature review. Comput Education. (2018) 122:54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2018.03.019

18. Cai X, Li Z, Zhang J, Peng M, Yang S, Tian X, et al. Effects of ARCS model-based motivational teaching strategies in community nursing: A mixed-methods intervention study. Nurse Educ Today. (2022) 119:105583. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2022.105583

19. NICE. Type 1 diabetes in adults: diagnosis and management. (2022). Available online at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng17/chapter/Recommendations#education-and-information.

20. Chatterjee S, Davies MJ, Heller S, Speight J, Snoek FJ, and Khunti K. Diabetes structured self-management education programmes: a narrative review and current innovations. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. (2018) 6:130–42. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30239-5

21. Jiang X, Jiang H, Tao L, and Li M. The cost-effectiveness analysis of self-efficacy-focused structured education program for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in mainland China setting. Front Public Health. (2021) 9:767123. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.767123

22. Allen WC. Overview and evolution of the ADDIE training system. Adv Developing Hum Resources. (2006) 8:430–41. doi: 10.1177/1523422306292942

23. Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, Milne R, Perera R, Moher D, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. Bmj. (2014) 348:g1687. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1687

24. Lockwood C, Porrit K, Munn Z, Rittenmeyer L, Salmond S, Bjerrum M, et al. JBI manual for evidence synthesis. In: Chapter 2: Systematic reviews of qualitative evidence: JBI Adelaide Australia (2020). Available online at: https://synthesismanual.jbi.globa.

25. Stern C, Lizarondo L, Carrier J, Godfrey C, Rieger K, Salmond S, et al. Methodological guidance for the conduct of mixed methods systematic reviews. JBI evidence synthesis. (2020) 18:2108–18. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-D-19-00169

26. Graneheim UH and Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. (2004) 24:105–12. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001

27. Yang HX. Guideline for the diagnosis and management of hyperglycemia in pregnancy (2022) [Part II. Chin J Obstetrics Gynecology. (2022) 57:81–90. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112141-20210917-00529

28. Yang HX. Guideline for the diagnosis and management of hyperglycemia in pregnancy (2022) [Part I. Chin J Obstetrics Gynecology. (2022) 57:3–12. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112141-20210917-00528

30. Dolan P, Hallsworth M, Halpern D, King D, Metcalfe R, and Vlaev I. Influencing behaviour: The mindspace way. J economic Psychol. (2012) 33:264–77. doi: 10.1016/j.joep.2011.10.009

32. Hollands GJ, Bignardi G, Johnston M, Kelly MP, Ogilvie D, Petticrew M, et al. The TIPPME intervention typology for changing environments to change behaviour. Nat Hum Behaviour. (2017) 1:0140. doi: 10.1038/s41562-017-0140

33. Knowles MS, Holton EF III, and Swanson RA. The adult learner: The definitive classic in adult education and human resource development. Oxon, New York: Routledge (2014).

34. Liu Y, Li M, and Jiang H. A pilot study of structured treatment and education program for type 2 diabetic patients without insulin therapy. Chin J Diabetes. (2016) 24:638–44. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1006-6187.2016.07.016

35. Wang Y, Zhang R, and Feng S. Social support and physical activity in pregnant women with gestational diabetes mellitus: exploring the mediating role of fear of falling. Nurs Open. (2025) 12:e70174. doi: 10.1002/nop2.70174

36. Leng J, Shao P, Zhang C, Tian H, Zhang F, Zhang S, et al. Prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus and its risk factors in Chinese pregnant women: a prospective population-based study in Tianjin, China. PloS One. (2015) 10:e0121029. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121029

37. Zheng X, Zhang Q, Su W, Liu W, Huang C, Shi X, et al. Dietary intakes of women with gestational diabetes mellitus and pregnancy outcomes: A prospective observational study. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. (2024) 17:2053–63. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S455827

38. Li M, Shi J, Luo J, Long Q, Yang Q, OuYang Y, et al. Diet quality among women with previous gestational diabetes mellitus in rural areas of hunan province. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:5942. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17165942

39. He J, Hu K, Xing C, Wang B, Zeng T, and Wang H. Puerperium experience and lifestyle in women with gestational diabetes mellitus and overweight/obesity in China: A qualitative study. Front Psychol. (2023) 14:1043319. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1043319

40. Teh K, Quek IP, and Tang WE. Postpartum dietary and physical activity-related beliefs and behaviors among women with recent gestational diabetes mellitus: a qualitative study from Singapore. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2021) 21:612. doi: 10.1186/s12884-021-04089-6

41. Ge L, Wikby K, and Rask M. ‘Is gestational diabetes a severe illness?’ exploring beliefs and self-care behaviour among women with gestational diabetes living in a rural area of the south east of China. Aust J Rural Health. (2016) 24:378–84. doi: 10.1111/ajr.12292

42. Hui AL, Sevenhuysen G, Harvey D, and Salamon E. Barriers and coping strategies of women with gestational diabetes to follow dietary advice. Women Birth. (2014) 27:292–7. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2014.07.001

43. Luo R, Li J, Zhang X, Tian D, and Zhang Y. Effects of applying blended learning based on the ADDIE model in nursing staff training on improving theoretical and practical operational aspects. Front Med (Lausanne). (2024) 11:1413032. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2024.1413032

44. Lee E and Baek G. Development and effects of adult nursing education programs using virtual reality simulations. Healthcare (Basel). (2024) 12:1313. doi: 10.3390/healthcare12131313

45. Wah YYE, McGill M, Wong J, Ross GP, Harding AJ, and Krass I. Self-management of gestational diabetes among Chinese migrants: A qualitative study. Women Birth. (2019) 32:e17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2018.03.001

46. Dennison RA, Ward RJ, Griffin SJ, and Usher-Smith JA. Women’s views on lifestyle changes to reduce the risk of developing Type 2 diabetes after gestational diabetes: a systematic review, qualitative synthesis and recommendations for practice. Diabetes Med. (2019) 36:702–17. doi: 10.1111/dme.13926

47. Ferrara A, Hedderson MM, Albright CL, Ehrlich SF, Quesenberry CP Jr., Peng T, et al. A pregnancy and postpartum lifestyle intervention in women with gestational diabetes mellitus reduces diabetes risk factors: a feasibility randomized control trial. Diabetes Care. (2011) 34:1519–25. doi: 10.2337/dc10-2221

Keywords: gestational diabetes mellitus, type 2 diabetes mellitus, patient education, adherence, motivation

Citation: Huang J, Long T, Li H, Cui H, Zhang D, Wu Y, Zhang Y, Sun X, Zhao Y, Wei Y and Li M (2025) Developing a comprehensive structured program for managing gestational diabetes mellitus and preventing type 2 diabetes mellitus in Chinese women: a multi-method study. Front. Endocrinol. 16:1627702. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2025.1627702

Received: 13 May 2025; Accepted: 14 July 2025;

Published: 01 August 2025.

Edited by:

Javier Diaz-Castro, University of Granada, SpainReviewed by:

Nguyen Bao Tri, Hung Vuong Hospital, VietnamThamudi Sundarapperuma, University of Ruhuna, Sri Lanka

Copyright © 2025 Huang, Long, Li, Cui, Zhang, Wu, Zhang, Sun, Zhao, Wei and Li. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mingzi Li, bGltaW5nemlAYmptdS5lZHUuY24=

†ORCID: Jing Huang, orcid.org/0000-0002-5740-1767

Tianxue Long, orcid.org/0000-0002-8033-2843

Hua Li, orcid.org/0009-0004-3974-4450

Hangyu Cui, orcid.org/0009-0000-3984-1665

Dan Zhang, orcid.org/0009-0007-4611-6868

Yi Wu, orcid.org/0000-0001-9281-7891

Yiyun Zhang, orcid.org/0000-0002-2521-8132

Xinying Sun, orcid.org/0000-0001-6638-1473

Yan Zhao, orcid.org/0009-0002-9256-9730

Yuan Wei, orcid.org/0000-0003-3387-7549

Mingzi Li, orcid.org/0000-0003-0186-8859

Jing Huang

Jing Huang Tianxue Long

Tianxue Long Hua Li1†

Hua Li1† Hangyu Cui

Hangyu Cui Xinying Sun

Xinying Sun Mingzi Li

Mingzi Li