- 1Department of Reproductive Immunology, Shanghai First Maternity and Infant Hospital, School of Medicine, Tongji University, Shanghai, China

- 2Shanghai Key Laboratory of Maternal and Fetal Medicine, Shanghai First Maternity and Infant Hospital, Shanghai, China

- 3Center for Reproductive Medicine, Shanghai First Maternity and Infant Hospital, School of Medicine, Tongji University, Shanghai, China

Background: Recurrent implantation failure (RIF) leads to a significant waste of embryos and imposes substantial physical, emotional, and financial stress on patients. Given its complex and diverse etiology, identifying the underlying causes and developing effective interventions are crucial. Previous studies have shown that insulin resistance (IR) has negative effects on reproductive health, and metformin pre-treatment helps improve the pregnancy outcomes in IR patients. However, its role in patients with RIF remains unclear, especially in those without polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).

Methods: A retrospective cohort study was conducted. The FET cycles of RIF patients without PCOS were stratified based on the presence or absence of IR. We used the univariate and multivariate generalized estimating equations (GEE) analysis to compare pregnancy outcomes between patients with IR and without IR, as well as between metformin-exposed and metformin-unexposed groups of RIF patients with IR.

Results: In a subgroup of 941 cycles without IR and 145 cycles with IR, we found that patients with IR had a lower live birth rate (10.34% vs 20.94%, P = 0.0039) and a higher early miscarriage rate (52.77% vs 27.52%, P = 0.0034). After adjusting for potential confounders, the IR group still had a lower live birth rate (aOR = 0.5, 95% CI: 0.28-0.89, P = 0.019). In the subgroup of IR patients (n=330 cycles), patients in the metformin-exposed group (n=185 cycles) had a higher clinical pregnancy rate (43.24% vs 24.83%, P < 0.001), implantation rate (33.22% vs 17.04%, P < 0.001) and live birth rate (33.51% vs 10.34%, P < 0.001), as well as a lower early miscarriage rate (12.50% vs 52.78%, P < 0.01), compared to the metformin-unexposed group (n=145 cycles). These differences remained significant after adjusting for potential confounders using GEE analysis.

Conclusions: Our results demonstrated that IR may be a risk factor for a low live birth rate in RIF patients without PCOS. However, the negative impact of IR on the live birth rate can be alleviated by metformin pre-treatment before FET cycles.

Introduction

In vitro fertilization⁃embryo transfer (IVF⁃ET) offers infertile couples a chance to conceive their biological children. However, approximately 10%–20% of patients experience recurrent implantation failure (RIF) (1), characterized by the failure to achieve a clinical pregnancy after transferring high-quality embryos in multiple transfer cycles. The emotional and financial burden of RIF is considerable, highlighting the need for a detailed investigation into its underlying causes and potential therapeutic interventions. Nevertheless, the precise mechanisms remain inadequately understood, and effective interventions for RIF patients are limited. Currently, there are no standardized criteria for diagnosing RIF. A recent comprehensive survey defined RIF as the failure to achieve a clinical pregnancy after two or three transfers with good-quality embryos (2, 3). Evidence suggests that RIF has a multifactorial etiology, including maternal factors, embryonic factors, unhealthy lifestyle, and unknown causes (4). Among these, insulin resistance (IR) has emerged as a critical area of investigation, particularly in its impact on reproductive health (5).

IR is characterized by decreased sensitivity to exogenous or endogenous insulin, resulting in compensatory hyperinsulinemia to maintain metabolic homeostasis (6). IR and associated hyperinsulinemia may contribute to the reproductive and endocrine features of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) by disrupting androgen and gonadotrophin secretion (7). This disruption may worsen reproductive and metabolic outcomes in women with PCOS undergoing ovulation induction and potentially impact pregnancy outcomes (8). IR is also a risk factor for spontaneous abortion in PCOS women undergoing IVF-ET (9). Notably, studies have shown that 23.8% of women without PCOS are also diagnosed with IR (10). However, the effects of IR on pregnancy outcomes in non-PCOS women undergoing IVF-ET remain debated (11–13). Further research is necessary to clarify its implications on reproductive outcomes in this population.

Recent research has also explored potential therapeutic interventions targeting IR to improve reproductive outcomes. Lifestyle modifications, including dietary changes and increased physical activity, enhance insulin sensitivity and restore hormonal balance in women with IR (14). Additionally, pharmacological treatments such as metformin, commonly used to improve insulin sensitivity, have been widely studied for managing PCOS (15–17). Adjunct metformin therapy could be used before and/or during FSH ovarian stimulation in women with PCOS undergoing IVF/ICSI treatment with a GnRH agonist long protocol, to reduce the risk of developing ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome and miscarriage (18). Although previous research has shown that metformin pre-treatment can improve ongoing pregnancy and implantation rates in non-PCOS women receiving IVF-ET (19), its clinical effectiveness in these patients remains controversial. A randomized double-blind controlled trial (RCT) on metformin pre-treatment for patients undergoing in vitro fertilization/intracytoplasmic sperm injection-embryo transfer (IVF/ICSI-ET) showed no difference in the implantation rate, miscarriage rate, or live birth rate (LBR) (20). Further investigation is needed to elucidate how IR affects reproductive outcomes in this population and to explore the potential benefits of metformin pre-treatment on fertility outcomes.

In the current study, we aim to evaluate the impact of IR status on pregnancy outcomes in non-PCOS RIF patients undergoing frozen embryo transfer (FET) cycles. Additionally, we aim to assess whether metformin pre-treatment could improve pregnancy outcomes in non-PCOS RIF patients diagnosed with IR.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

This retrospective cohort study was conducted at Shanghai First Maternity and Infant Hospital. Data for this study were obtained from the hospital’s electronic database, containing all medical records of patients who underwent IVF/ICSI-ET treatments. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Shanghai First Maternity and Infant Hospital (NO.KS25210), and informed consent was waived because of its retrospective design.

We screened the intact medical records of FET cycles conducted at the Center for Reproductive Medicine, and of the various examinations and treatments for RIF patients at the Department of Reproductive Immunology in our hospital from January 2019 to December 2023. Patients were enrolled in the study if they met the following criteria: (i) they were diagnosed with RIF; (ii) their records included fasting blood sugar and insulin values. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (i) preimplantation genetic testing (PGT) cycles, or cycles in which more than 50% of the blastomeres are absent; (ii) patients aged > 40 years; (iii) diagnosed with PCOS according to Rotterdam criterion (21); (iv) abnormal thyroid function or prolactin levels; (v) history of recurrent spontaneous abortion (22); (vi) patients with autoimmune diseases; and (vii) abnormal anatomy including untreated hydrosalpinx, endometrial polyps, genital tuberculosis and chronic endometritis; (viii) with missing data.

Diagnosis

RIF was defined as a failure to achieve a clinical pregnancy despite transferring good-quality embryos under the following conditions: (1) three or more transfer cycles; or (2) at least three embryos transferred within two cycles, with at least one high-quality blastocyst or two high-quality cleavage-stage embryos transferred in each cycle. Consistent with previous studies, a good-quality blastocyst was defined as a blastocyst at stage 3 or higher, with neither inner cell mass nor trophectoderm graded C by the Gardner score system. A good-quality cleavage-stage embryo on day 3 was defined as an embryo with 7–12 blastomeres, rated as grade I-II or compacted (23). For the following analysis, we assign the group that transfers at least one high-quality embryo as Group A, while the others will be classified as Group B.

IR was diagnosed using the homeostasis model assessment for insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), calculated as [fasting insulin (µIU/mL) × fasting glucose (mmol/L)]/22.5 (24). The cutoff value for HOMA-IR was 2.71 (25).

PCOS was diagnosed based on the Rotterdam criterion (21), which require at least two of the following three conditions: chronic ovulatory dysfunction or oligomenorrhea, hyperandrogenism, and the presence of polycystic ovaries on ultrasound.

Metformin exposure

For RIF patients with IR, those who received metformin for ≥2 months before FET were classified into the metformin-exposed group, clinicians adjusted the dosage based on body mass index (BMI), IR severity and gastrointestinal tolerance. Those who did not receive any insulin-lowering medication were classified as the metformin-unexposed group. Metformin was discontinued upon pregnancy confirmation.

Endometrial preparation and FET

As previously described (26–29), endometrial preparation was performed in a natural cycle, ovarian induction cycle, or hormone replacement therapy based on the patient’s situation and physicians’ preference. Cleavage-stage embryo transfer was performed on the third day after ovulation or the fourth day after progesterone administration, whereas blastocyst transfer was scheduled on the fifth day after ovulation or the sixth day after progesterone administration. One or two embryos were transferred in each FET cycle.

Progesterone supplementation was continued until 10 weeks of gestation once pregnancy was confirmed. Serum beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG) levels were measured two weeks after embryo transfer. Patients with a positive test result underwent a transvaginal ultrasonographic examination an additional two weeks later to confirm the presence of an intrauterine gestation sac with a fetal heartbeat.

Outcome measurement

The primary outcome of this study was the LBR per FET cycle. Secondary outcomes included the biochemical pregnancy rate, clinical pregnancy rate, multiple pregnancy rate, implantation rate, early miscarriage rate, and late miscarriage rate. Serum β-hCG levels were measured 14 days after embryo transfer. For women with positive results (β-hCG ≥ 10 mIU/mL), transvaginal ultrasonography was routinely conducted 4 weeks after embryo transfer. Biochemical pregnancy was defined as a pregnancy confirmed only by the detection of β-hCG in the serum, which did not progress to a clinical pregnancy. Clinical pregnancy was defined as a pregnancy confirmed through ultrasonographic detection of one or more gestational sacs, including ectopic pregnancies. The implantation rate was calculated as the number of gestational sacs divided by the number of embryos transferred. Early miscarriage was the loss of a clinical pregnancy before the 12th week of gestation, while late miscarriage occurred after 12 weeks. Multiple pregnancy was defined as two or more gestational sacs detected by ultrasonography. A live birth was defined as the delivery of at least one live-born baby. For neonatal outcomes, low birth weight was defined as a birth weight of less than 2,500g.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using R (http://www.R-project.org) (v.4.2.3). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Continuous variables were presented as means with standard deviation (SD), and categorical variables were presented as counts with percentages. Statistical comparison was performed using the Mann–Whitney U-test for continuous variables. Differences in categorical variables between the two groups were compared using Fisher’s exact tests or the Chi-square test as appropriate.

We used the geeglm function from the geepack package (v.1.3.9) to perform the univariate and multivariate generalized estimating equations (GEE) analyses. Both crude odds ratio (OR) and adjusted odds ratio (aOR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated using GEE.

According to the objectives of our study, it was divided into two parts. In part one, we employed GEE analysis to examine the effect of IR on pregnancy outcomes by comparing 941 FET cycles without IR to 145 FET cycles with IR, all without metformin exposure. The analysis adjusted for confounders, including maternal age, infertility duration, BMI, number of transferred embryos, endometrial thickness on the day of embryo transfer, endometrial preparation regimen, type of infertility, and infertile factors.

In part two, we used GEE analysis to investigate the impact of metformin pre-treatment on pregnancy outcomes by comparing 145 FET cycles without metformin exposure to 185 FET cycles with metformin exposure, with both groups diagnosed with IR based on the HOMA-IR cutoff values. The analysis adjusted for confounders, including the maternal age, infertility duration, BMI, number of transferred embryos, endometrial thickness on the embryo transfer day, endometrial preparation regimen, type of infertility, infertile factors, and HOMA-IR values.

Results

Study groups

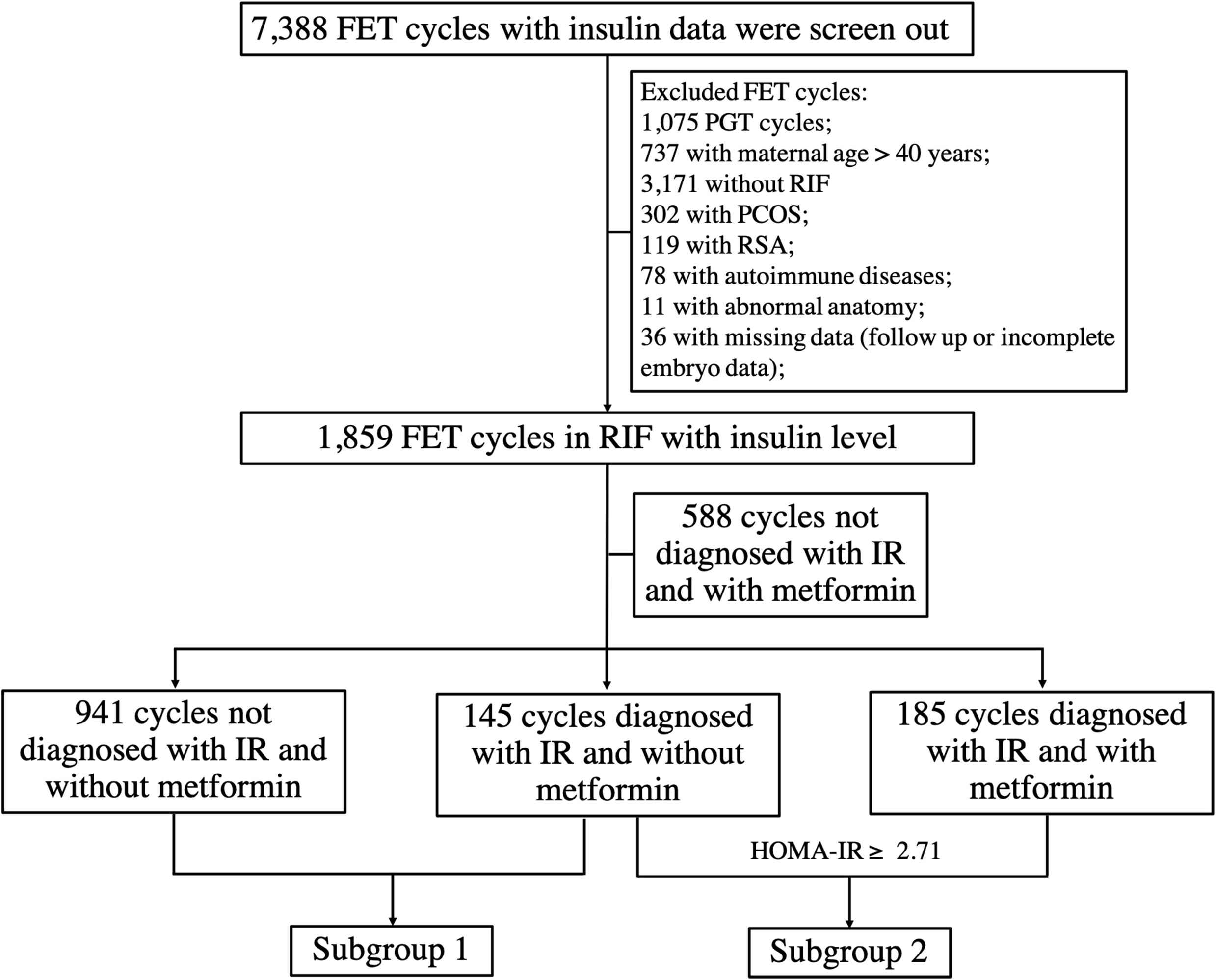

The flowchart of the study is presented in Figure 1. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, a total of 1,859 FET cycles were enrolled in the study. Of those, 1,529 cycles were diagnosed as non-IR, while 330 cycles were diagnosed as IR according to the HOMA-IR cutoff value (HOMA-IR ≥ 2.71). Among the 330 cycles, 145 cycles were unexposed to metformin, while 185 FET cycles were exposed to metformin.

Figure 1. The flowchart of the study. RSA, recurrent spontaneous abortion; PGT, preimplantation genetic testing; PCOS, polycystic ovary syndrome.

Subgroup analysis based on IR diagnosed

Initially, we investigated the role of IR in pregnancy outcomes of non-PCOS RIF patients. Among 1,086 FET cycles without metformin pre-treatment, 99 patients (145 cycles) had IR (IR group), while 605 patients (941 cycles) did not (non-IR group).

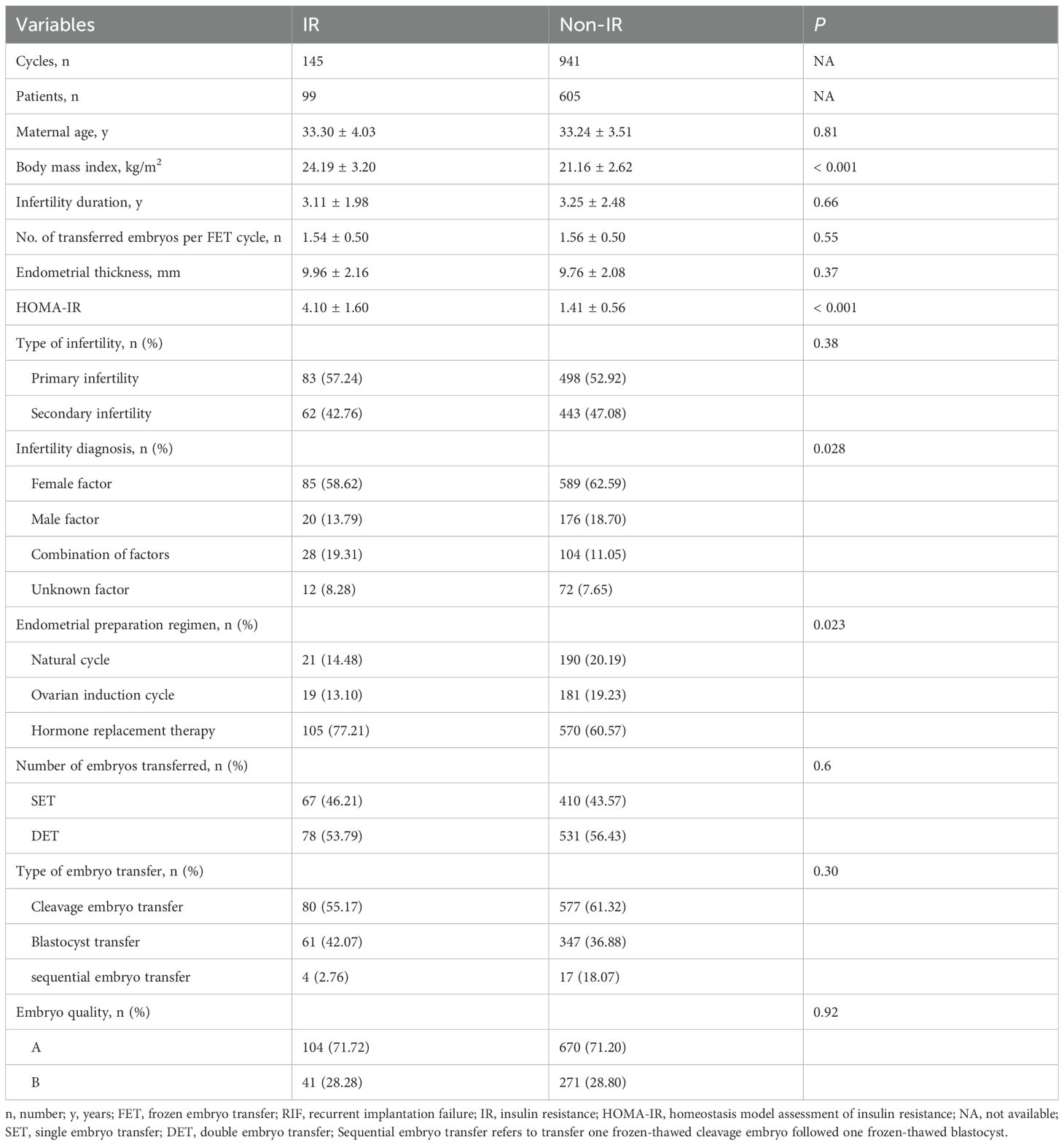

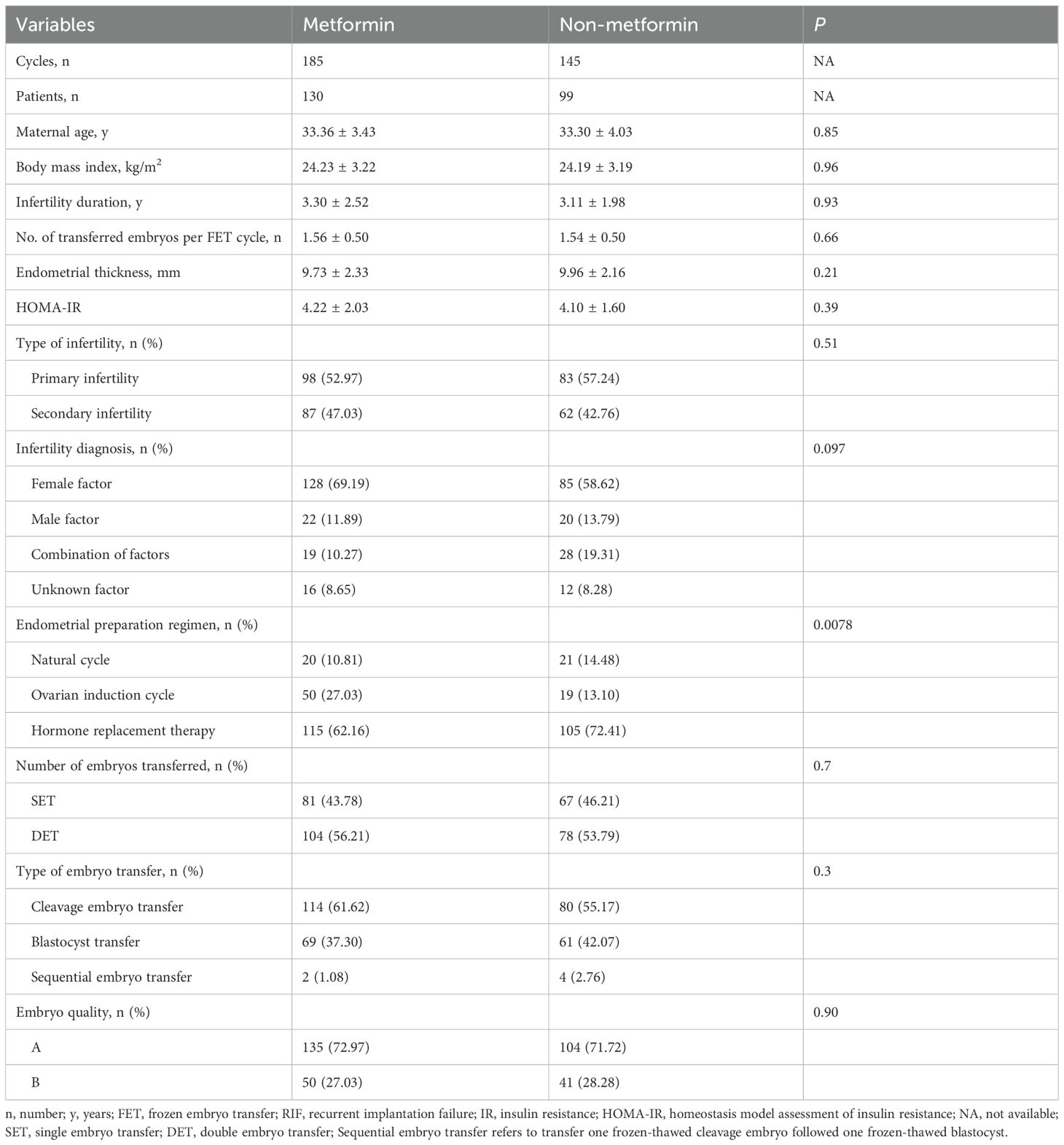

The baseline characteristics of this subgroup were summarized in Table 1. No significant differences were observed between the IR and non-IR groups regarding maternal age, duration of infertility, type of infertility, number of transferred embryos per FET cycle, embryo quality, or endometrial thickness on the embryo transfer day (P > 0.05). However, significant differences were observed in BMI, HOMA-IR values, infertility diagnosis, and the endometrial preparation regimens (P < 0.05) (Table 1).

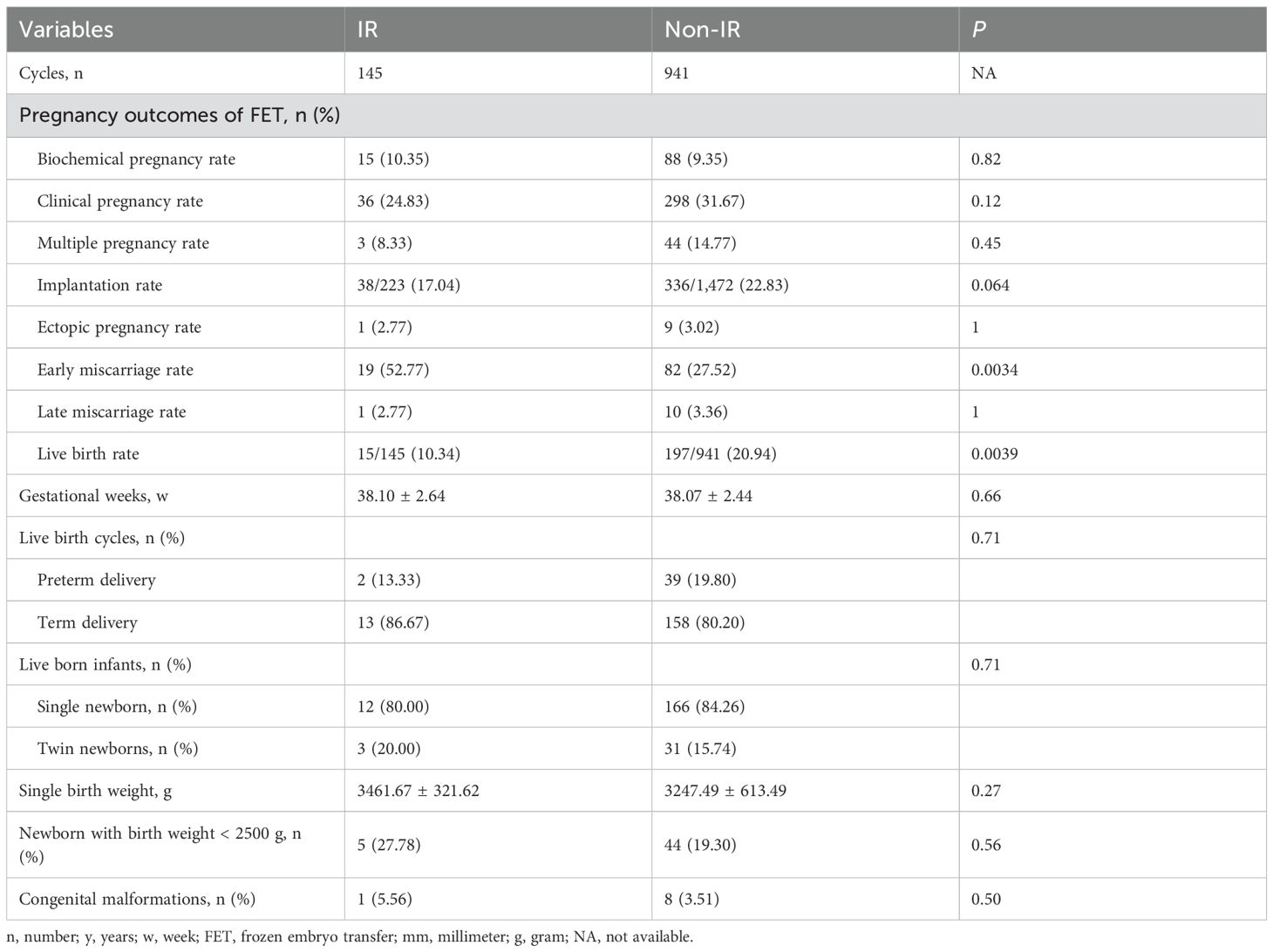

Pregnancy and neonatal outcomes were presented in Table 2; Supplementary Figure 1. No significant differences were observed in biochemical pregnancy rate, clinical pregnancy rate, multiple pregnancy rate, implantation rate, ectopic pregnancy rate, or late miscarriage rate (P > 0.05). However, the IR group had a lower LBR (10.34% vs 20.94%, P = 0.0039) and a higher early miscarriage rate (52.77% vs 27.52%, P = 0.0034), compared to non-IR group. Neonatal outcomes revealed that IR and non-IR patients were similar in terms of gestational weeks, preterm birth rate, proportion of singletons, percentage of low birthweight newborns, and incidence of congenital malformations (P > 0.05).

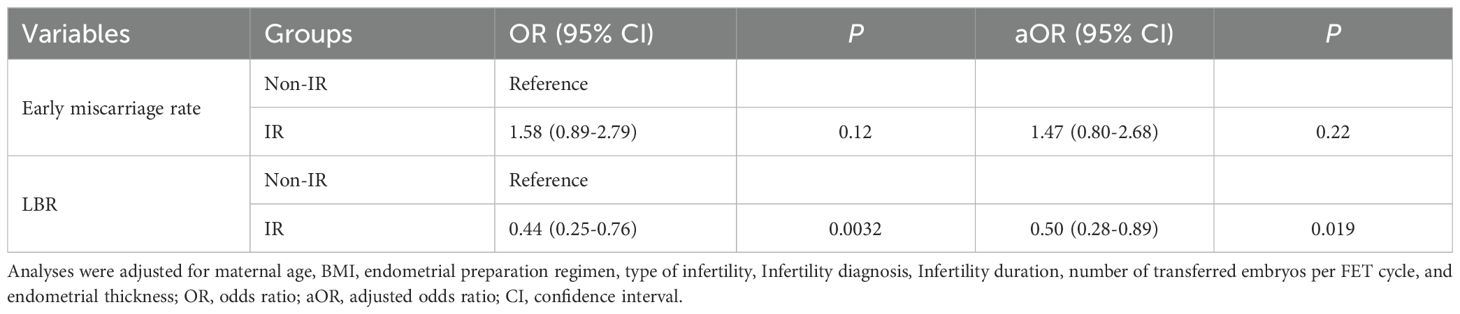

To further explore the association between IR and LBR and early miscarriage rate, we conducted univariate and multivariate GEE analyses (Table 3). Both univariate and multivariate GEE analyses revealed no significant differences in early miscarriage rate (P > 0.05). However, the univariate GEE analysis showed that IR group had a lower LBR (OR 0.44, 95% CI: 0.25-0.76, P = 0.0032) (Table 3). After adjusting for potential confounders, including the maternal age, infertility duration, BMI, number of transferred embryos, endometrial thickness on the embryo transfer day, endometrial preparation regimen, type of infertility, and infertile factors in the multivariable GEE model, IR group still remained a lower LBR (aOR 0.50, 95% CI 0.28-0.89, P = 0.019) (Table 3; Supplementary Table 1).

Table 3. Univariate and multivariate generalized estimating equations analyses results of the association between IR status and clinical outcomes.

Subgroup analysis based on metformin exposure

Next, we tried to explore whether metformin pre-treatment would improve the pregnancy outcomes in non-PCOS patients with IR. A total of 330 transfer cycles were involved in the analysis. Among these, 130 patients who completed 185 transfer cycles had been exposed to metformin (Metformin group) prior to FET, while 99 patients underwent 145 transfer cycles unexposed to metformin (Non-metformin group) prior to FET.

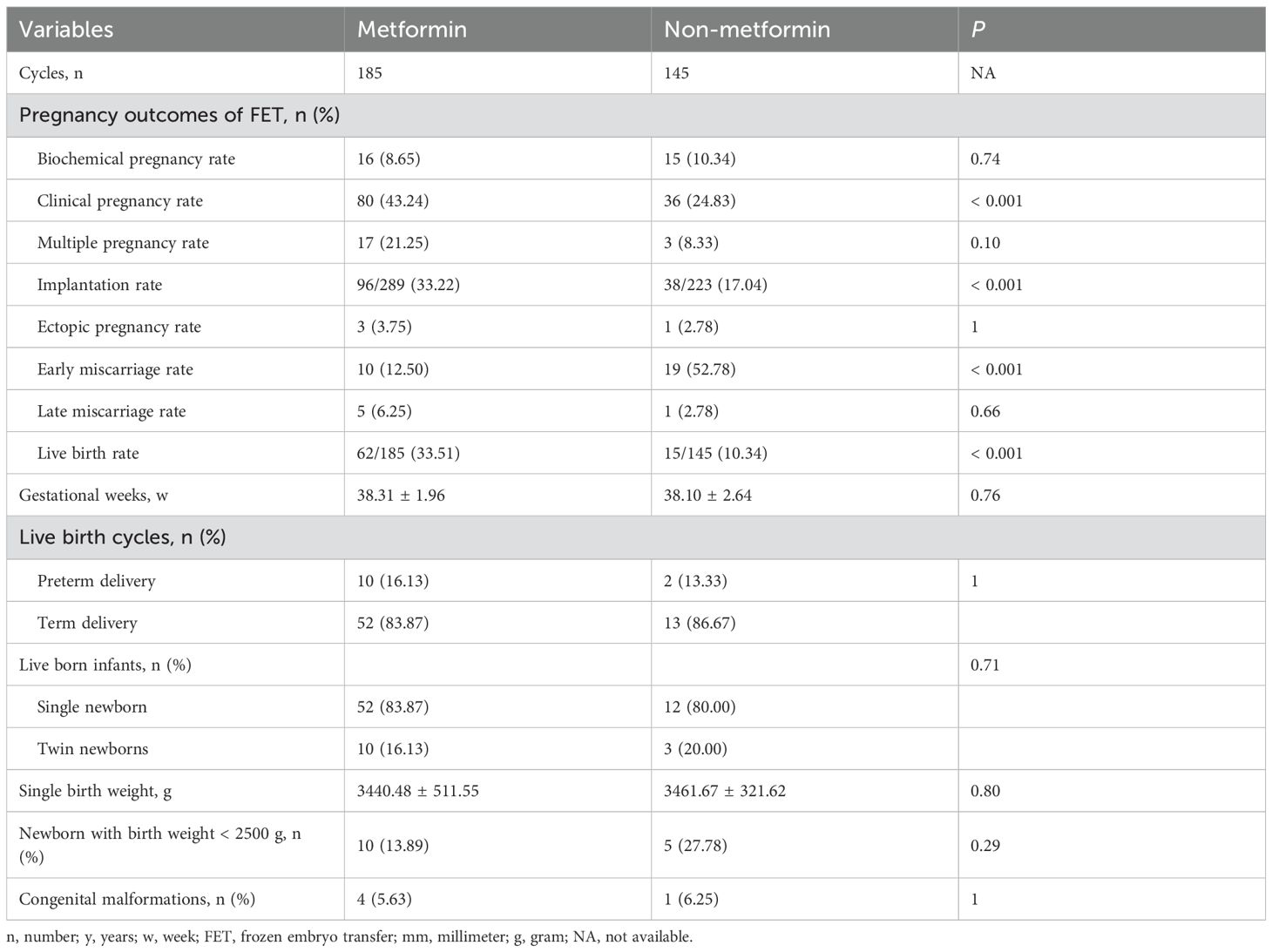

The baseline characteristics of this subgroup were presented in Table 4. Except for the endometrial preparation regimen, which showed a statistical difference between the two groups, (P = 0.0078), no significant differences were observed in maternal age, BMI, duration of infertility, number of transferred embryos per FET cycle, embryo quality, endometrial thickness, HOMA-IR, type of infertility, infertility diagnosis, number of embryos transferred, or type of embryo transfer between the two groups (P > 0.05). Pregnancy and neonatal outcomes indicated that Metformin group was associated with a higher clinical pregnancy rate (43.24% vs 24.83%, P < 0.001), implantation rate (32.22% vs 17.04%, P < 0.001), and LBR (33.51% vs 10.34%, P < 0.001), as well as a lower early miscarriage rate (12.50% vs 52.78%, P < 0.001) (Table 5; Supplementary Figure 2). However, no statistical differences were found in other indicators, such as biochemical pregnancy rate, ectopic pregnancy rate, and late miscarriage rate (P > 0.05). Additionally, there were no statistical differences in neonatal outcomes, including preterm birth rate, multiple pregnancy rate, singleton birth weight, and congenital malformation rate (P > 0.05).

Table 4. Baseline characteristics of RIF women undergoing FET in the metformin and non-metformin group.

Table 5. Pregnancy and neonatal outcomes of RIF women undergoing FET in the metformin and non-metformin group.

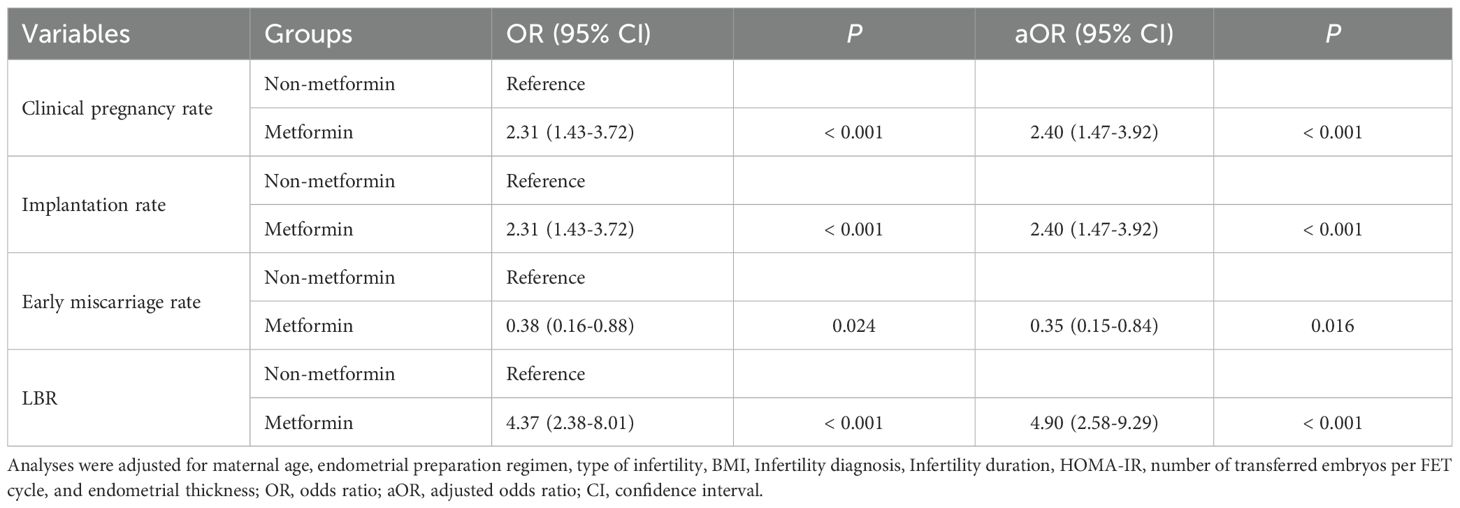

Then, we assessed the association between the metformin pre-treatment and the clinical pregnancy rate, implantation rate, LBR, and early miscarriage rate using univariate and multivariable GEE models. In the univariate GEE model, metformin pre-treatment was significantly associated with higher clinical pregnancy rate (OR 2.31, 95% CI: 1.43-3.72, P < 0.001), implantation rate (OR 2.31, 95% CI 1.43-3.72, P < 0.001), and LBR (OR 4.37, 95% CI: 2.38-8.01, P < 0.001), as well as lower early miscarriage rate (OR 0.38, 95% CI: 0.16-0.88, P = 0.024) (Table 6). After adjusting for potential confounders, such as maternal age, infertility duration, BMI, number of transferred embryos, endometrial thickness on the embryo transfer day, endometrial preparation regimen, type of infertility, infertile factors, and HOMA-IR values, metformin pre-treatment remained associated with reduced risk of early miscarriage rate (aOR 0.35, 95% CI: 0.15-0.84, P = 0.016) and increased likelihood of clinical pregnancy rate (aOR 2.40, 95% CI: 1.47-3.92, P < 0.001), implantation rate (aOR 2.40, 95% CI: 1.47-3.92, P < 0.001), and LBR (aOR 4.90, 95% CI 2.58-9.29, P < 0.001) (Table 6 and Supplementary Table 2).

Table 6. Univariate and multivariate generalized estimating equations analyses results of the association between metformin status and clinical outcomes.

Discussion

RIF is a complex condition with multiple causes (e.g., immunology, thrombophilias, endocrine disorders, metabolic dysregulation, microbiome alterations, anatomical defects, male factors, and genetics), posing significant challenges for patients and clinicians (30). This study investigated the association between IR and pregnancy outcomes in non-PCOS RIF patients and the effect of metformin pre-treatment in IR patients. We found that IR is a risk factor for reduced LBR in non-PCOS patients. However, metformin pre-treatment for ≥2 months before FET mitigated this effect, leading to improvements in clinical pregnancy, implantation rate, and LBR, while also reducing early miscarriage rate. Our findings highlight the detrimental effects of IR and support metformin pre-treatment for improving outcomes.

IR is a metabolic condition characterized by the diminished ability of cells to respond effectively to insulin. This phenomenon is increasingly prevalent among women of reproductive age (31). The rising incidence of IR among women has significant implications for reproductive health, as it is closely linked to various endocrine disorders, including PCOS, infertility, and other reproductive dysfunctions (32). IR is thought to contribute to adverse outcomes in ART cycles, including lower pregnancy rate, reduced implantation rate, and higher miscarriage rate (25, 33, 34). The mechanisms underlying the impact of IR on adverse pregnancy outcomes are multifaceted. In addition to the impact on reproductive hormones and ovulation, studies have shown that women with IR often experience endometrial abnormalities, which can increase the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes (35). Furthermore, IR is associated with chronic low-grade inflammation, which can adversely affect ovarian function, endometrial receptivity, and live birth (36).

Some studies have shown that as HOMA-IR values increased, the LBR markedly decreased across different PCOS groups (37) and that IR is significantly associated with LBR in fresh ET cycles in women with PCOS (38). However, the correlation between IR and the LBR in assisted reproduction is still controversial. A study by Luo et al. found that IR had no significant effect on pregnancy rate and LBR in the first fresh embryo transfer cycles (39). Among non-PCOS subjects, previous studies have reported that hyperinsulinemia and IR have no impact on the reproductive outcomes in women undergoing assisted reproduction (13). However, a recent study has confirmed that in the context of ART, infertile non-PCOS women with IR showed a higher clinical miscarriage, leading to fewer live births compared with the insulin-sensitive infertile patients (40). In our study, when comparing the pregnancy outcomes between IR and non-IR groups, we also found that patients diagnosed with IR had a lower LBR, even after adjusting for the potential confounders. This suggests that IR may be a risk factor for low LBR. Thus, our findings highlight the importance of managing IR in women undergoing fertility treatment to improve reproductive outcomes.

In clinical practice, the treatment of RIF is also very tricky. To improve treatment efficacy for individuals facing RIF with IR, we pay attention to whether pre-treating IR with metformin improves pregnancy outcomes in RIF patients. However, the effect of metformin pre-treatment in ART remains debated. A 2020 meta-analysis of women with PCOS found no conclusive evidence that metformin improves LBR (41). Additionally, an RCT analysis also showed no difference in implantation rate, miscarriage rate, or LBR with or without metformin pre-treatment (20). Moreover, studies have shown that metformin can improve ongoing pregnancy, implantation rates, and LBR, as well as lower clinical miscarriage (19, 40). We found that IR patients with metformin pre-treatment showed higher clinical pregnancy rate, implantation rate, and LBR, along with lower early miscarriage rate. The significant difference still remained in the GEE model. These results emphasize the need for further studies to confirm the effects of metformin pre-treatment on pregnancy outcomes in ART.

Metformin can suppress appetite to reduce weight and plasma insulin levels. It can decrease hyperandrogenism and improve menstrual cycles and ovulation in women with PCOS (42, 43). Metformin has been shown to enhance SLC2A4 function in the endometrium, which is the crucial role of the insulin-dependent glucose transporter SLC2A4 in endometrial glucose uptake, and a low expression of SLC2A4 can impair endometrial metabolism (9). Additionally, other studies suggested that although embryonic development may not be directly affected by IR, endometrial receptivity was often compromised, which may reduce the implantation rate and LBR (44). Metformin appears to improve endometrial receptivity, thereby enhancing both implantation rate and LBR (45). A recent study using spatial transcriptome sequencing and single-cell transcriptome sequencing techniques indicated that 16 weeks of metformin treatment can improve the health of the endometrium in PCOS patients by targeting integrin signaling and dysregulated pathways (46). It was also reported that metformin could improve dyslipidemia in a non-PCOS population of patients (47); therefore, it is evident that metformin has potential benefits for non-PCOS patients. Since there is little research on non-PCOS at present, we hypothesize that similar to the PCOS group, metformin may improve the pregnancy outcomes by improving endometrial function in the non-PCOS group, but further studies are still needed to verify it.

Effective endometrial preparation before FET is crucial for synchronizing the embryonic and endometrial windows of receptivity, which is key to achieving successful implantation. This preparation can be achieved through a natural cycle, an ovarian induction cycle, or a hormone replacement therapy. In the current study we found statistical differences between IR and non-IR group, as well as between metformin and non-metformin group in terms of endometrial preparation regimens (Tables 1 and 4). To assess the potential impact of different regimens on the study outcomes, we performed a GEE analysis. Both univariate and multivariate GEE analyses confirmed that the endometrial preparation regimens had no effect on the conclusions of the current study. This aligns with previously reported findings, which suggest that different endometrial preparation regimens do not impact clinical outcomes (48, 49). However, the possibility of residual confounders cannot be ruled out. For example, due to the absence of corpus luteum in HRT, is likely contributing to the increased risk of obstetric complications and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (50, 51). Since progesterone is primarily secreted by the corpus luteum, it remains unclear whether the lack of an endogenous progesterone could influence outcomes of assisted reproductive treatments. This highlights the need for further studies involving larger cohorts to explore more uniform endometrial preparation regimens or to stratify by preparation regimens to minimize variability and provide clearer insights into the current conclusions.

Our study provides novel insights into how IR influences pregnancy outcomes and how metformin treatment for IR enhances reproductive outcomes in women with RIF who do not have PCOS before FET. However, some limitations still exist. First, the small sample size means our findings should be interpreted with caution. Future research should evaluate the effects of metformin treatment in larger, independent cohorts of RIF patients without PCOS. Additionally, incomplete data on fasting plasma glucose and insulin levels after metformin treatment further limit the strength of our findings. Future studies should include prospective trials with larger cohorts to assess the impact of metformin on FET outcomes in patients with RIF and IR. Furthermore, due to the retrospective nature of our study, we cannot fully eliminate the potential impact of sample selection bias, embryonic factors, and the information regarding the embryos transferred in previous IVF cycles of RIF patients on the conclusions, which may limit the generalizability of the conclusions. Therefore, future prospective cohort studies are needed to validate the findings of this study further. Lastly, women with IR who are exposed to metformin may be more attentive to their health status and, as a result, may pursue additional healthcare interventions to improve the success of FET. This combined effect suggests that the improvement in clinical outcomes for RIF patients with IR may not be solely attributed to the effect of metformin. This represents another limitation of the study that should be addressed in future research.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study highlights the detrimental effect of IR on the pregnancy outcomes in non-PCOS patients with RIF and the beneficial effects of metformin treatment before FET on pregnancy outcomes in patients with RIF without PCOS. Our findings support the importance of addressing IR during IVF/ICSI treatments. Identifying women at high risk of IR is crucial for optimizing preventative and therapeutic strategies in patients with RIF. However, more large-scale prospective studies are warranted to ascertain the benefits of metformin on pregnancy outcomes and determine the optimal dose and duration of metformin treatment based on the severity of IR.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethics Committee of the Shanghai First Maternity and Infant Hospital. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The ethics committee/institutional review board waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin because Informed consent was waived because of its retrospective design.

Author contributions

LP: Writing – original draft, Data curation. WY: Methodology, Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition. MD: Data curation, Writing – original draft. XD: Data curation, Writing – original draft. RZ: Data curation, Writing – original draft. DQ: Methodology, Writing – original draft. SB: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Shanghai Municipal Natural Science Foundation General Program (23ZR1450100), Shanghai Pudong New Area obstetrics and gynecology medical consortium project (PDYLT2022-04), and Shanghai First Maternity and Infant Hospital, affiliated with Tongji University School of Medicine (2025B23).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the staff of the Center for Reproductive Medicine and Department of Reproductive Immunology at Shanghai First Maternity and Infant Hospital for their cooperation and support. We would also like to thank the patients who participated in this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fendo.2025.1671899/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

IVF-ET, in vitro fertilization⁃embryo transfer; RIF, recurrent implantation failure; IR, insulin resistance; PCOS, polycystic ovary syndrome; RCT, randomized double-blind controlled trial; IVF/ICSI-ET, in vitro fertilization/intracytoplasmic sperm injection-embryo transfer; LBR, live birth rate; FET, frozen embryo transfer; HOMA-IR, homeostasis model assessment for insulin resistance; β-hCG, beta-human chorionic gonadotropin; SD, standard deviation; GEE, generalized estimating equations; OR, crude odds ratio; aOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

References

1. Coughlan C, Ledger W, Wang Q, Liu F, Demirol A, Gurgan T, et al. Recurrent implantation failure: definition and management. Reprod BioMed Online. (2014) 28:14–38. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2013.08.011

2. Cimadomo D, Craciunas L, Vermeulen N, Vomstein K, and Toth B. Definition, diagnostic and therapeutic options in recurrent implantation failure: an international survey of clinicians and embryologists. Hum Reprod. (2021) 36:305–17. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deaa317

3. ESHRE Working Group on Recurrent Implantation Failure, Cimadomo D, de Los Santos MJ, Griesinger G, Lainas G, Le Clef N, et al. ESHRE good practice recommendations on recurrent implantation failure. Hum Reprod Open. (2023) 2023:hoad023. doi: 10.1093/hropen/hoad023

4. Zohni KM, Gat I, and Librach C. Recurrent implantation failure: a comprehensive review. Minerva Ginecol. (2016) 68:653–67.

5. Herman T, Csehely S, Orosz M, Bhattoa HP, Deli T, Torok P, et al. Impact of endocrine disorders on IVF outcomes: results from a large, single-centre, prospective study. Reprod Sci. (2023) 30:1878–90. doi: 10.1007/s43032-022-01137-0

6. Diamanti-Kandarakis E and Dunaif A. Insulin resistance and the polycystic ovary syndrome revisited: an update on mechanisms and implications. Endocr Rev. (2012) 33:981–1030. doi: 10.1210/er.2011-1034

7. Norman RJ, Dewailly D, Legro RS, and Hickey TE. Polycystic ovary syndrome. Lancet. (2007) 370:685–97. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61345-2

8. Zhang D, Yang X, Li J, Yu J, and Wu X. Effect of hyperinsulinaemia and insulin resistance on endocrine, metabolic and fertility outcomes in women with polycystic ovary syndrome undergoing ovulation induction. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). (2019) 91:440–8. doi: 10.1111/cen.14050

9. Sun Y-F, Zhang J, Xu Y-M, Cao Z-Y, Wang Y-Z, Hao G-M, et al. High BMI and insulin resistance are risk factors for spontaneous abortion in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome undergoing assisted reproductive treatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). (2020) 11:592495. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2020.592495

10. Ohgi S, Nakagawa K, Kojima R, Ito M, Horikawa T, and Saito H. Insulin resistance in oligomenorrheic infertile women with non-polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. (2008) 90:373–7. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.06.045

11. Wang H, Zhang Y, Fang X, Kwak-Kim J, and Wu L. Insulin resistance adversely affect IVF outcomes in lean women without PCOS. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). (2021) 12:734638. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2021.734638

12. Dickerson EH, Cho LW, Maguiness SD, Killick SL, Robinson J, and Atkin SL. Insulin resistance and free androgen index correlate with the outcome of controlled ovarian hyperstimulation in non-PCOS women undergoing IVF. Hum Reprod. (2010) 25:504–9. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep393

13. Cai W-Y, Luo X, Song J, Ji D, Zhu J, Duan C, et al. Effect of hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance on endocrine, metabolic, and reproductive outcomes in non-PCOS women undergoing assisted reproduction: A retrospective cohort study. Front Med (Lausanne). (2021) 8:736320. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.736320

14. Šišljagić D, Blažetić S, Heffer M, Vranješ Delać M, and Muller A. The interplay of uterine health and obesity: A comprehensive review. Biomedicines. (2024) 12:2801. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines12122801

15. Kjøtrød SB, Carlsen SM, Rasmussen PE, Holst-Larsen T, Mellembakken J, Thurin-Kjellberg A, et al. Use of metformin before and during assisted reproductive technology in non-obese young infertile women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a prospective, randomized, double-blind, multi-centre study. Hum Reprod. (2011) 26:2045–53. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der154

16. Tang T, Glanville J, Orsi N, Barth JH, and Balen AH. The use of metformin for women with PCOS undergoing IVF treatment. Hum Reprod. (2006) 21:1416–25. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del025

17. Morin-Papunen L, Rantala AS, Unkila-Kallio L, Tiitinen A, Hippeläinen M, Perheentupa A, et al. Metformin improves pregnancy and live-birth rates in women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): a multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2012) 97:1492–500. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-3061

18. Teede HJ, Tay CT, Laven JJE, Dokras A, Piltonen TT, Costello MF, et al. Recommendations from the 2023 international evidence-based guideline for the assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Eur J Endocrinol. (2023) 189:G43–64. doi: 10.1093/ejendo/lvad096

19. Jinno M, Kondou K, and Teruya K. Low-dose metformin improves pregnancy rate in in vitro fertilization repeaters without polycystic ovary syndrome: prediction of effectiveness by multiple parameters related to insulin resistance. Hormones (Athens). (2010) 9:161–70. doi: 10.14310/horm.2002.1266

20. Abdalmageed OS, Farghaly TA, Abdelaleem AA, Abdelmagied AE, Ali MK, and Abbas AM. Impact of metformin on IVF outcomes in overweight and obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome: A randomized double-blind controlled trial. Reprod Sci. (2019) 26:1336–42. doi: 10.1177/1933719118765985

21. Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. (2004) 81:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.10.004

22. ESHRE Guideline Group on RPL, Bender Atik R, Christiansen OB, Elson J, Kolte AM, Lewis S, et al. ESHRE guideline: recurrent pregnancy loss. Hum Reprod Open. (2018) 2018:hoy004. doi: 10.1093/hropen/hoy004

23. Sun Y, Cui L, Lu Y, Tan J, Dong X, Ni T, et al. Prednisone vs placebo and live birth in patients with recurrent implantation failure undergoing in vitro fertilization: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. (2023) 329:1460–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2023.5302

24. Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, and Turner RC. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. (1985) 28:412–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00280883

25. Yang T, Yang Y, Zhang Q, Liu D, Liu N, Li Y, et al. Homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance is associated with late miscarriage in non-dyslipidemic women undergoing fresh IVF/ICSI embryo transfer. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). (2022) 13:880518. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.880518

26. Zhu X, Ye J, and Fu Y. Late follicular phase ovarian stimulation without exogenous pituitary modulators. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). (2020) 11:487. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2020.00487

27. Zhu X, Ye H, and Fu Y. Use of Utrogestan during controlled ovarian hyperstimulation in normally ovulating women undergoing in vitro fertilization or intracytoplasmic sperm injection treatments in combination with a “freeze all” strategy: a randomized controlled dose-finding study of 100 mg versus 200 mg. Fertil Steril. (2017) 107:379–386.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.10.030

28. Zhu X, Ye H, and Fu Y. Duphaston and human menopausal gonadotropin protocol in normally ovulatory women undergoing controlled ovarian hyperstimulation during in vitro fertilization/intracytoplasmic sperm injection treatments in combination with embryo cryopreservation. Fertil Steril. (2017) 108:505–512.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.06.017

29. Zhu X and Fu Y. Evaluation of ovarian stimulation initiated from the late follicular phase using human menopausal gonadotropin alone in normal-ovulatory women for treatment of infertility: A retrospective cohort study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). (2019) 10:448. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2019.00448

30. Ma J, Gao W, and Li D. Recurrent implantation failure: A comprehensive summary from etiology to treatment. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). (2022) 13:1061766. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.1061766

31. Zhao X, An X, Yang C, Sun W, Ji H, and Lian F. The crucial role and mechanism of insulin resistance in metabolic disease. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). (2023) 14:1149239. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2023.1149239

32. Zhao H, Zhang J, Cheng X, Nie X, and He B. Insulin resistance in polycystic ovary syndrome across various tissues: an updated review of pathogenesis, evaluation, and treatment. J Ovarian Res. (2023) 16:9. doi: 10.1186/s13048-022-01091-0

33. Stepto NK, Cassar S, Joham AE, Hutchison SK, Harrison CL, Goldstein RF, et al. Women with polycystic ovary syndrome have intrinsic insulin resistance on euglycaemic-hyperinsulaemic clamp. Hum Reprod. (2013) 28:777–84. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des463

34. Cassar S, Misso ML, Hopkins WG, Shaw CS, Teede HJ, and Stepto NK. Insulin resistance in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of euglycaemic-hyperinsulinaemic clamp studies. Hum Reprod. (2016) 31:2619–31. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dew243

35. Masjedi M, Izadi Y, Montahaei T, Mohammadi R, Ali Helforoush M, and Rohani Rad K. An illustrated review on herbal medicine used for the treatment of female infertility. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. (2024) 302:273–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2024.09.028

36. Ascaso Á, Latorre-Pellicer A, Puisac B, Trujillano L, Arnedo M, Parenti I, et al. Endocrine evaluation and homeostatic model assessment in patients with cornelia de lange syndrome. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. (2024) 16:211–7. doi: 10.4274/jcrpe.galenos.2022.2022-4-14

37. Chen Y, Guo J, Zhang Q, and Zhang C. Insulin resistance is a risk factor for early miscarriage and macrosomia in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome from the first embryo transfer cycle: A retrospective cohort study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). (2022) 13:853473. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.853473

38. Wu S, Wu Y, Fang L, and Lu X. Association of insulin resistance surrogates with live birth outcomes in women with polycystic ovary syndrome undergoing in vitro fertilization. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2025) 25:25. doi: 10.1186/s12884-024-07131-5

39. Luo Z, Wang L, Wang Y, Fan Y, Jiang L, Xu X, et al. Impact of insulin resistance on ovarian sensitivity and pregnancy outcomes in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome undergoing IVF. J Clin Med. (2023) 12:818. doi: 10.3390/jcm12030818

40. Albert AB, Corachán A, Juárez-Barber E, Cozzolino M, Pellicer A, Alecsandru D, et al. Association of insulin resistance with in vitro fertilization outcomes in women without polycystic ovarian syndrome: potential improvement with metformin treatment. Hum Reprod. (2025) 40(8):1562–9. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deaf100

41. Tso LO, Costello MF, Albuquerque LET, Andriolo RB, and Macedo CR. Metformin treatment before and during IVF or ICSI in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2020) 12:CD006105. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006105.pub4

42. Jin J, Ma Y, Tong X, Yang W, Dai Y, Pan Y, et al. Metformin inhibits testosterone-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress in ovarian granulosa cells via inactivation of p38 MAPK. Hum Reprod. (2020) 35:1145–58. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deaa077

43. Naderpoor N, Shorakae S, de Courten B, Misso ML, Moran LJ, and Teede HJ. Metformin and lifestyle modification in polycystic ovary syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. (2015) 21:560–74. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmv025

44. Chang EM, Han JE, Seok HH, Lee DR, Yoon TK, and Lee WS. Insulin resistance does not affect early embryo development but lowers implantation rate in in vitro maturation-in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer cycle. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). (2013) 79:93–9. doi: 10.1111/cen.12099

45. Yuan L, Wu H, Huang W, Bi Y, Qin A, and Yang Y. The function of metformin in endometrial receptivity (ER) of patients with polycyclic ovary syndrome (PCOS): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. (2021) 19:89. doi: 10.1186/s12958-021-00772-7

46. Eriksson G, Li C, Sparovec TG, Dekanski A, Torstensson S, Risal S, et al. Single-cell profiling of the human endometrium in polycystic ovary syndrome. Nat Med. (2025) 31(6):1925–38. doi: 10.1038/s41591-025-03592-z

47. Salpeter SR, Buckley NS, Kahn JA, and Salpeter EE. Meta-analysis: metformin treatment in persons at risk for diabetes mellitus. Am J Med. (2008) 121:149–157.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.09.016

48. Kalem Z, Kalem MN, Bakirarar B, Kent E, and Gurgan T. Natural cycle versus hormone replacement therapy cycle in frozen-thawed embryo transfer. SMJ. (2018) 39:1102–8. doi: 10.15537/smj.2018.11.23299

49. Glujovsky D, Pesce R, Sueldo C, Quinteiro Retamar AM, Hart RJ, and Ciapponi A. Endometrial preparation for women undergoing embryo transfer with frozen embryos or embryos derived from donor oocytes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2020) 10:CD006359. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006359.pub3

50. Busnelli A, Schirripa I, Fedele F, Bulfoni A, and Levi-Setti PE. Obstetric and perinatal outcomes following programmed compared to natural frozen-thawed embryo transfer cycles: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod. (2022) 37:1619–41. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deac073

Keywords: recurrent implantation failure, insulin resistance, frozen embryo transfer, metformin, pregnancy outcomes

Citation: Peng L, Yang W, Du M, Deng X, Zhang R, Qin D and Bao S (2025) Metformin improves pregnancy outcomes in non-PCOS women with insulin resistance and recurrent implantation failure before frozen embryo transfer. Front. Endocrinol. 16:1671899. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2025.1671899

Received: 23 July 2025; Accepted: 18 November 2025; Revised: 05 November 2025;

Published: 10 December 2025.

Edited by:

Konstantinos Dafopoulos, University of Thessaly, GreeceCopyright © 2025 Peng, Yang, Du, Deng, Zhang, Qin and Bao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shihua Bao, YmFvc2hpaHVhQHRvbmdqaS5lZHUuY24=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Liying Peng1,2†

Liying Peng1,2† Wanli Yang

Wanli Yang Ruixiu Zhang

Ruixiu Zhang Shihua Bao

Shihua Bao