- Department of Cardiology, The Fourth Affiliated Hospital of School of Medicine, and International School of Medicine, International Institutes of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Yiwu, Zhejiang, China

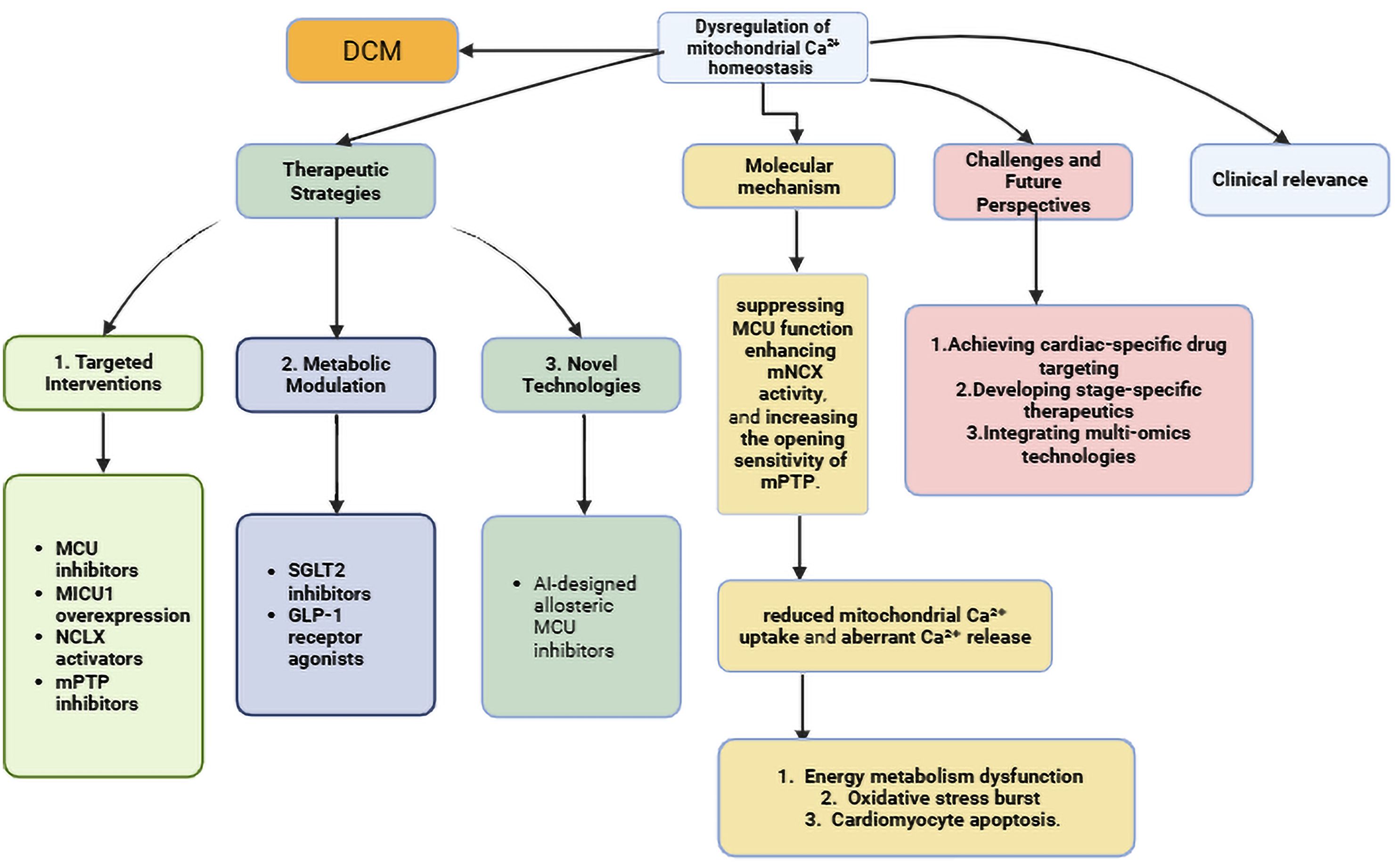

Diabetic cardiomyopathy (DCM), as a devastating complication of diabetes mellitus (DM), arises from a complex interplay between systemic metabolic derangements and myocardial vulnerability. While hyperglycemia, lipotoxicity, and insulin resistance are established drivers of cardiac dysfunction, the precise mechanisms linking these metabolic insults to cardiac dysfunction remain elusive. Recent evidence suggests that the dysregulation of mitochondrial calcium homeostasis plays a critical role in integrating diabetic metabolic stress and cardiomyocyte fate. This review synthesizes recent advances in understanding how mitochondrial calcium mishandling—encompassing impaired uptake, excessive release, and buffering failure—orchestrates the pathological triad of bioenergetic deficit, oxidative stress, and cell death in DCM. We delve into the molecular mechanisms underpinning this dysregulation, highlighting its interplay with the diabetic metabolic milieu. Furthermore, we critically evaluate novel therapeutic strategies targeting mitochondrial calcium fluxes, including the inhibition of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter (MCU), the activation of the mitochondrial Na+/Ca2+/Li+ exchanger (NCLX), and the modulation of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP), discussing their clinical translation potential and existing challenges. By reframing DCM through the lens of mitochondrial calcium homeostasis, this review not only synthesizes current knowledge but also provides a critical comparison of emerging therapeutic strategies and evaluates the formidable challenges in their clinical translation, thereby bridging the gap between endocrine metabolism and cardiac pathophysiology and offering nuanced perspectives for biomarker discovery and stage-specific interventions.

Highlights

● Mitochondrial calcium (Ca2+) imbalance is a core mechanism linking systemic metabolic stress to cardiac dysfunction in diabetes.

● Diabetic conditions (hyperglycemia, advanced glycation end products (AGEs), and oxidative stress) directly impair the molecular machinery of mitochondrial calcium uptake (MCU) and release (mPTP, NCLX).

● Mitochondrial calcium imbalance triggers a vicious cycle of energy crisis, oxidative damage, and cardiomyocyte death, culminating in heart failure.

● Therapeutic strategies targeting mitochondrial calcium fluxes (e.g., cardiac-specific MCU inhibitors, NCLX activators) show promise in preclinical models.

● Translating these strategies to the clinic requires stage-specific approaches and reliable biomarkers of mitochondrial function.

1 Introduction

1.1 Background

Diabetic cardiomyopathy (DCM), a pathophysiological condition induced by diabetes mellitus (DM), is a significant contributor to heart failure (HF) (1). Leading global health organizations, including the World Health Organization (WHO), the American Heart Association (AHA), and the International Diabetes Federation (IDF), have identified DCM as a predominant cause of mortality in patients with diabetes (2–4).

Recent population-based studies report that 12–17% of patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) are diagnosed with DCM, while systematic cardiac phenotyping reveals subclinical cardiac dysfunction in over 50% of these patients (5, 6). Prospective cohort data indicate that 29% of asymptomatic T2D patients progress to overt DCM within 5 years, primarily driven by metabolic stress and microvascular injury (7). The trajectory involves progressive myocardial fibrosis and inflammation, ultimately culminating in HF (8). Notably, DCM is associated with a 75% higher risk of cardiovascular mortality than non-diabetic HF, after adjustment for comorbidities (9). The persistent and significant contribution of diabetic cardiomyopathy to the global burden of cardiovascular mortality has been further emphasized in recent large-scale epidemiological studies (10).

The global burden of DCM has mirrored the diabetes pandemic, with age-standardized prevalence rising by 7.9% annually between 2017 and 2022. This increase strongly correlates with regional T2D growth rates (ρ=0.91, p<0.001) (11). More recent estimates from the Global Burden of Disease Study underscore the escalating burden, highlighting the urgent need for targeted interventions (12). Mechanistic drivers (e.g., mitochondrial dysfunction, lipotoxicity) remain therapeutic targets; however, no disease-modifying therapies currently exist (13, 14). Ongoing research continues to delineate the intricate mechanisms, including mitochondrial calcium dysregulation, that underpin the progression from diabetes to heart failure (15). This therapeutic gap is further emphasized in contemporary reviews, which call for a deeper understanding of the fundamental pathophysiological processes, such as mitochondrial quality control and ion homeostasis (16).

Mitochondrial calcium (Ca2+) imbalance is a key pathophysiological link between diabetic metabolic derangements and myocardial dysfunction. Given the multitude of Ca2+-handling proteins that regulate the Ca2+ transients in cardiomyocytes, DCM has been shown to disrupt these proteins through altered expression, function, or both (17). Mitochondria buffer cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations, thereby playing a central role in cardiac excitation-contraction coupling (ECC) (18, 19). Impairment of this mitochondrial function compromises cardiac contractility and contributes to cardiac dysfunction (18). In diabetic mice, studies have demonstrated impaired cardiac mitochondrial function associated with ultrastructural defects (20). Conversely, under pathological conditions—such as ischemia, infarction, and pressure overload—cellular stress induces excessive cytosolic Ca2+ accumulation, leading to mitochondrial Ca2+ overload. This overload increases reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, disrupts mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨ), and promotes opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP), accompanied by ATP depletion (21, 22). Collectively, these events trigger cardiomyocyte death and progressive cardiac dysfunction. Therefore, maintaining the mitochondrial Ca2+ homeostasis is essential for cardiomyocyte survival and functional integrity. Reflecting this, mitochondrial calcium homeostasis is increasingly recognized as a central integrator of metabolic stress and cardiac dysfunction in diabetes, bridging systemic derangements to myocardial injury (23).

This review summarizes recent advances in mitochondrial Ca2+homeostasis, emphasizing its critical role in cardiac Ca2+ regulation. It also outlines emerging therapeutic strategies targeting mitochondrial Ca2+ pathways for DCM treatment and prevention.

2 Mitochondrial calcium homeostasis: basics and regulatory mechanisms

2.1 Mechanisms of mitochondrial calcium uptake and release

In general, the physiological concentration of mitochondrial Ca2+ is tightly regulated by two major operative regulatory systems that either release Ca2+ into the cytosol or take up Ca2+ from the cytosol. Voltage-dependent anion channel 1 (VDAC1), located on the outer mitochondrial membrane, acts as the first gatekeeper of Ca2+ entering mitochondria (24). Initially, Ca2+ accumulates in the mitochondrial intermembrane space (IMS), and then, it enters the mitochondrial matrix through the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter (MCU). By interacting with various regulatory proteins, such as calcium uptake proteins (MICUs), the MCU forms a functional complex that precisely controls the uptake of Ca2+ into the matrix. Conversely, Ca2+ stored in the matrix can be transported back to IMS through Na+/Ca2+ (NCX) or H+/Ca2+exchangers (25), as well as by mPTP opening when the cell is under stress (26, 27). Although Ca2+ uptake and release appear to be two independent processes, some studies indicate that an interlink may exist between them. For example, mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake may affect the initiation and activation of the releasing system, particularly mPTP opening during stress (28–30). In addition to these conventional regulatory apparatuses, newly identified proteins are being discovered that contribute to mitochondrial Ca2+ homeostasis and cardiac mitochondrial function. One such example is valosin-containing protein (VCP), an AAA+ ATPase that has been recently implicated in the regulation of both mitochondrial calcium uptake (by modulating MCU complex stability) and mPTP opening under stress conditions (31).

2.1.1 Mitochondrial calcium uptake

Mitochondria possess a low-affinity, high-capacity calcium ion uptake system, primarily mediated by the MCU (32). MCU is present in almost all cell types and functions as a highly selective calcium channel responsible for Ca2+ uptake in mitochondria (33). There are two transmembrane domains located in the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM), with both the N-terminal and C-terminal domains facing the mitochondrial matrix. The N-terminal domain (NTD) is believed to regulate Ca2+ uptake rate (34). Although studies on the molecular nature of the MCU complex began in the 1970s, MCU itself was not identified and confirmed as an essential component of the MCU until 2011 (35–37). Since then, the structure of the MCU has been elucidated in various species, including fungi, C. elegans, zebrafish, and humans (33). The transmembrane and NTD structures are conserved across species, highlighting their essential role in mitochondrial Ca2+ homeostasis. Over the years of effort, the core components of the MCU complex (MCU, EMRE, MICU1, MICU2) and associated regulatory factors (such as MCUR1 and MICU3) have been identified. Cryo-electron microscopy technology has specifically elucidated the structure of the MCU-EMRE core channel, offering a molecular foundation for comprehending its functional mechanisms. The identification of MICU1 and MICU2 as gatekeepers that prevent Ca2+ uptake under resting conditions represented a breakthrough in understanding the regulation of the uniporter (38). Wang, Y., and his team further elucidated the molecular basis of the MICU1/2 gating role using cryo-electron microscopy (39).

2.1.1.1 Cytosolic low-calcium state ([Ca2+]₋ < 1–3 μM)

Biological systems feature exquisitely designed molecular switches. The response of MICU1/2 to calcium ions is not a binary “on/off” switch but rather the result of graded conformational changes. At calcium concentrations below 1 μM, MICU1/2 stably blocks the channel; between 1 and 3 μM, it partially opens; and at approximately 3 μM, the channel becomes fully open (enabling efficient calcium uptake). Thus, activation occurs over a concentration range rather than at a single threshold. The MICU1/MICU2 heterodimer (or, in some cases, MICU1 homodimers) interacts via its positively charged domain with negatively charged regions near the entrance of the MCU-EMRE pore. This physical blocking effect significantly reduces the MCU channel’s affinity for Ca2+ (manifested as an increased Kd), effectively closing the channel and preventing leakage of low-level Ca2+ into the mitochondria under resting conditions. This regulation is crucial for maintaining matrix ion homeostasis and energy efficiency.

2.1.1.2 Cytosolic elevated-calcium state ([Ca2+]₋ > 10 μM)

When cytosolic (or intermembrane space) [Ca2+] levels rise, Ca2+ binds to the EF-hand domains of MICU1 and MICU2. Ca2+ binding induces a significant conformational change in MICU1, weakening or abolishing the physical blockade of the MCU pore by the MICU1/MICU2 complex. As a result, the channel “gate” opens, significantly enhancing the MCU channel’s affinity for Ca2+. This allows efficient and rapid Ca2+ uptake into the mitochondrial matrix, supporting cellular processes such as energy production and signal transduction.

2.1.2 Mitochondrial calcium release

The mechanisms of mitochondrial calcium release are primarily categorized into the following three types:

2.1.2.1 mPTP

The mPTP is a non-selective, high-conductance channel in the inner mitochondrial membrane. Its sustained opening is a catastrophic event, fundamentally altering mitochondrial homeostasis. While it can lead to the release of Ca2+ and other small molecules, its primary pathological role is to cause the irreversible collapse of the ΔΨm, uncoupling oxidative phosphorylation and leading to ATP depletion. Furthermore, osmotic imbalance causes mitochondrial swelling and rupture of the outer membrane, releasing pro-apoptotic factors like cytochrome c, thereby initiating cell death pathways (26, 27, 40). Transient opening leads to the release of calcium ions and small molecules. The molecular composition of mPTP has been a subject of significant recent controversy. The classical model previously described the mPTP as comprising three components: adenine nucleotide translocase (ANT—located in the inner membrane), the voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC—located in the outer membrane), and cyclophilin D (CypD—a matrix protein, regulatory subunit). CypD binding to ANT promotes pore opening (41). However, recent studies propose a revised model: compelling recent evidence strongly points towards the F0F1-ATP synthase—specifically its dimers, oligomers, or the c-subunit ring—possibly forming the core pore channel. Genetic knockout experiments have shown that the absence of ANT or VDAC does not completely prevent mPTP opening (42), whereas experimental targeting of F-ATP synthase effectively modulates the mPTP (43).

2.1.2.2 Mitochondrial Na+/Ca2+ exchanger

Under specific conditions (e.g., decreased cytosolic Ca2+ levels, reduced ΔΨm), mitochondria can also release calcium via the sodium-calcium exchanger (38). This exchanger represents the primary “physiological” pathway for mitochondrial calcium efflux. It utilizes the Na+ electrochemical gradient across the inner membrane (positive outside, negative inside, and high cytosolic Na+ concentration) to actively exchange matrix Ca2+ for cytosolic Na+ at a stoichiometry of 3 Na+: 1 Ca2+. The primary physiological pathway for mitochondrial Ca2+ efflux is mediated by the mitochondrial Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (mNCX), whose molecular identity is the Na+/Ca2+/Li+ exchanger (NCLX), encoded by the SLC8B1 gene (44).

2.1.2.3 Rapid mode release

In response to brief, high-frequency cytosolic Ca2+ pulses, mitochondria exhibit an extremely rapid calcium release (and uptake), far exceeding the rate mediated by mNCX. This release is independent of the mPTP, and while its molecular identity remains an area of active investigation, it represents a distinct mode of mitochondrial Ca²+ flux (22).

2.2 Mitochondrial Ca2+ buffering

Mitochondrial Ca2+ buffering mechanisms (such as calcium phosphate precipitation) are key processes for maintaining matrix calcium homeostasis. They temporarily sequester excess Ca2+ in the form of chemical precipitation, thereby preventing cellular damage caused by calcium overload.

Regulatory factors, such as the phosphate transporter (PiC), are part of this process. Kwong, J. Q., and colleagues, using a cardiac-specific model of PiC knockout mice (cPiC-KO), demonstrated the following pathway:

PiC deficiency → Reduced mitochondrial phosphate (Pi) uptake → Inhibition of calcium phosphate precipitation formation → Mitigation of respiratory chain damage caused by calcium overload → →Maintenance of ATP synthesis.

Furthermore, cPiC-KO mice exhibited a 60% reduction in myocardial infarct size and improved cardiac function (LVEF improved by 35%) following ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury (45).

It has been reported that the mitochondrial calcium buffering mechanism can prevent mPTP opening triggered by calcium oscillations, such as those occurring during systole in cardiomyocytes (46).

2.3 Core functions of mitochondrial calcium signaling

Mitochondrial Ca2+ signaling orchestrates cellular homeostasis through three cardinal mechanisms: optimization of bioenergetic output via TCA cycle and oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) regulation, bidirectional modulation of ROS homeostasis, and regulation of cell death pathways via the mPTP. Precise spatiotemporal control of this signaling axis is indispensable for physiological function; its dysregulation precipitates metabolic insufficiency, oxidative injury, or apoptotic cell death.

2.3.1 Regulation of energy metabolism

Calcium influx into the mitochondrial matrix serves as a critical activator of rate-limiting dehydrogenases within the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle. Specifically, Ca2+ directly stimulates:

Pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDH), relieving inhibitory constraints to accelerate pyruvate decarboxylation to acetyl-CoA (47); isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH3) (48); and α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex (OGDH) (49).

This concerted activation markedly elevates NADH and FADH2 production. These electron carriers subsequently fuel the electron transport chain (ETC), augmenting the proton gradient (Δψm) across the inner mitochondrial membrane. The resulting hyperpolarization potentiates ATP synthase activity, substantially enhancing OXPHOS efficiency (47). Critically, mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake through the MCU provides a rapid transduction mechanism that synchronizes mitochondrial energy production with cytosolic Ca2+ transients evoked by physiological stimuli (e.g., hormonal signaling or excitation-contraction coupling). This enables real-time matching of mitochondrial ATP production with cellular energy demand (49).

2.3.2 Bidirectional control of ROS

Mitochondrial Ca2+ exerts context-dependent effects on redox balance. At physiological concentrations, Ca2+ attenuates ROS generation through dual mechanisms: (i) enhanced ATP synthesis mitigates ETC over-reduction, limiting electron leakage; and (ii) activation of the NRF2 antioxidant pathway upregulates mitochondrial ROS-scavenging systems, including manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) and peroxiredoxin 3 (Prx3) (50). Conversely, pathological Ca2+ overload induces oxidative stress via (i) structural impairment of ETC complexes (notably Complex I), exacerbating electron escape; (ii) mPTP induction culminating in Δψm dissipation and catastrophic ROS release (51); (iii) context-dependent activation of pro-oxidant enzymes (e.g., glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) (52); and (iv) suppression of endogenous antioxidant capacity (53).

2.3.3 Apoptotic regulation via mPTP

Matrix Ca2+ accumulation serves as an essential trigger for mPTP opening, with co-factors (elevated ROS, diminished Δψm) synergistically lowering its activation threshold. Pore induction initiates a lethal cascade: mitochondrial swelling and irreversible Δψm collapse terminate OXPHOS, while efflux of pro-apoptotic factors (cytochrome c, apoptosis-inducing factor) activates caspase-dependent apoptosis (40). Key regulatory components include CypD, whose Ca2+-facilitated binding to the ATP synthase c-ring promotes pore formation (54), and modulatory proteins adenine nucleotide translocator (ANT) and phosphate carrier (PiC) that fine-tune mPTP sensitivity (55). The susceptibility to mPTP-mediated cell death is profoundly influenced by the systemic metabolic milieu. AMPK is a crucial integrator of energy and oxidative stress, critically regulates cardiac tolerance to ischemia/reperfusion injury, and its dysregulation in diabetes exacerbates mPTP-dependent cell death (56).

3 Mitochondrial calcium homeostasis dysregulation in DCM

3.1 Mitochondrial Ca2+ dysregulation phenomena observed in both preclinical and clinical studies of DCM include specific manifestations and consequences resulting from mitochondrial Ca2+ overload or impaired uptake

3.1.1 Core dysregulation phenomena (preclinical and clinical evidence)

Reduced Mitochondrial Ca2+ Uptake Studies have demonstrated the following: In preclinical models of DCM, such as models (db/db mice, STZ rats), exhibit decreased baseline mitochondrial Ca2+ content in cardiomyocytes and significantly attenuated mitochondrial Ca2+ elevation following β-adrenergic stimulation (17, 57).

Conversely, evidence from human DCM comes from myocardial biopsies of T2DM patients, which reveal reduced MCU protein expression and impaired mitochondrial Ca2+ buffering capacity (58). This phenomenon is attributed to direct hyperglycemic impairment: high glucose reduces the myocardial mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake rate, correlating with impaired MCU function (57). Transcriptional downregulation: Boudina et al. demonstrated that decreased PGC-1α expression in diabetic myocardium leads to reduced transcription of mitochondrial calcium transporters (including MCU and MICU1) (59). Oxidative damage: Ye, G. et al. proved that persistent ROS generation oxidatively modifies MCU channel subunits, diminishing their activity (30).

Increased release of mitochondrial Ca2+ and heightened sensitivity of mPTP are observed.

Experimental evidence demonstrates that in db/db mouse cardiac mitochondria, significantly less Ca2+ load is required to induce mPTP opening. Calcium retention capacity (CRC) is decreased. Inhibition of the mNCX improves calcium homeostasis (60). In isolated mitochondria: Mitochondria incubated under high glucose conditions exhibit increased susceptibility to mPTP opening (61). Mechanisms underlying elevated mPTP sensitivity: Upregulation of mNCX: Hyperglycemia activates protein kinase C (PKC) and Rho-associated kinase (ROCK), leading to increased expression and activity of mNCX (62). ROS/RNS-mediated modification of CypD: Accumulation of ROS (particularly H2O2 generated from superoxide dismutation) and lipid peroxidation products (e.g., 4-HNE) directly modify CypD, significantly lowering the threshold for mPTP opening (61). Increased intracellular [Na+]: Inhibition of Na+/K+-ATPase by advanced glycation end products (AGEs) in late stages elevates intracellular [Na+]. This promotes mNCX-mediated Ca2+ efflux from mitochondria (63).

3.1.1.1 Decoupling of cytosolic-mitochondrial calcium transients

Reported findings: Confocal imaging (64) (STZ rat cardiomyocytes): Cytosolic Ca2+ transients exhibit reduced amplitude and delayed recovery. Mitochondrial Ca2+ responses display a more pronounced lag relative to cytosolic signals. Electron microscopy (65) (human diabetic myocardium): Reduced sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR)-mitochondria contact sites are observed. Mechanisms underlying this decoupling include Sarcoplasmic Reticulum (SR) Dysfunction: Hyperglycemia suppresses SERCA2a (66) activity via oxidative modifications and O-GlcNAcylation modifications. Hyperglycemia increases RyR leak due to pathological hyperphosphorylation by PKA/PKC (67). Structural Disruption: Decreased Junctophilin-2 (JPH2) expression in diabetic myocardium increases the coupling distance between SR and mitochondria and impairs the efficiency of microdomain Ca2+ transfer (68).

3.1.2 Pathological consequences of mitochondrial Ca2+ overload or impaired uptake

The dysregulation of mitochondrial Ca2+ homeostasis, whether it manifests as insufficiency, local overload, or signaling decoupling, sets in motion a cascade of pathological events that drive the progression of DCM. As summarized in Table 1, these consequences are multifaceted and interlinked.

Insufficient mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake, driven by persistent hyperglycemia and insulin resistance, creates a profound energy crisis. The lack of Ca2+-mediated activation of TCA cycle dehydrogenases leads to reduced NADH/FADH2 production and, consequently, impaired ATP synthesis (69, 70). This bioenergetic deficit directly compromises cardiac contractility (71). Furthermore, this metabolic stagnation promotes a reliance on fatty acid oxidation while suppressing glucose utilization, exacerbating lipotoxic accumulation within the myocardium. Clinically, this manifests initially as early diastolic dysfunction, which progressively deteriorates into overt systolic failure.

Local mitochondrial Ca2+ overload, often triggered by acute stressors like ischemia or sympathetic excitation in the diabetic heart, initiates a destructive cycle. The overload induces a massive burst of ROS and sensitizes the mPTP, leading to irreversible opening. This results in oxidative damage to lipids and proteins and the release of pro-apoptotic factors like cytochrome c, triggering both apoptotic and necrotic cell death (74, 75). The ensuing loss of cardiomyocytes is replaced by fibrotic tissue, leading to cardiac chamber enlargement and progressive remodeling.

3.1.2.1 Ca2+ Signal decoupling between cytosolic and mitochondrial compartments

DCM severely compromises the efficient transfer of calcium from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) to the mitochondria, which is crucial for matching energy production to demand. This decoupling of Ca2+ signals arises from a combination of SR dysfunction and structural damage. Hyperglycemia suppresses SERCA2a activity through oxidative and O-GlcNAcylation modifications, impairing SR Ca2+ reuptake and delaying cytosolic Ca2+ clearance (66). Concurrently, it promotes pathological hyperphosphorylation of the ryanodine receptor (RyR) by PKA/PKC, increasing its leakiness (67). The downregulation of Junctophilin-2 (JPH2) in the diabetic myocardium increases the physical distance between the SR and mitochondria (68). This combination of functional and structural defects results in electromechanical desynchrony, manifesting as delayed cytosolic Ca2+ transients and worsened diastolic dysfunction. Additionally, mitochondria do not detect or respond to cytosolic Ca2+ signals, resulting in an energy supply lag that cannot accommodate abrupt metabolic demands, thereby diminishing exercise tolerance and elevating the risk of arrhythmias.

3.1.2.2 Inflammatory activation

Mitochondrial Ca2+ dysregulation is a potent trigger of sterile inflammation in DCM. Pathological mPTP opening and ROS bursts can cause the release of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) and other damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) into the cytosol. These molecules serve as strong danger signals that activate the inflammasome, especially the NLRP3 inflammasome. This, in turn, catalyzes the maturation and release of potent pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and IL-18 and promotes immune cell infiltration into the myocardium. This chronic, low-grade inflammatory activation amplifies initial injury, promotes fibrotic remodeling, and creates a vicious cycle that further deteriorates cardiac function.

3.1.2.3 Impaired mitophagy

The selective removal of damaged mitochondria, known as mitophagy, is essential for maintaining a healthy mitochondrial network. This process is often Ca2+-dependent. In DCM, the loss of proper Ca2+-mediated activation signals, combined with oxidative damage to key mitophagy proteins (e.g., PINK1/Parkin), impairs mitophagic flux. The resulting accumulation of damaged mitochondria becomes a persistent source of ROS and contributes to the energy deficit. This failure in mitochondrial quality control accelerates cardiomyocyte senescence and death, as the cell is unable to clear its dysfunctional power plants.

3.1.2.4 Mitochondrial dynamics imbalance

Mitochondria exist in a dynamic equilibrium of fission and fusion. Ca2+ is a key regulator of this process. In DCM, pathological matrix Ca2+ levels promote the activation of fission proteins like Drp1, while fusion processes (mediated by proteins like Mitofusin 2) are often suppressed. This condition leads to a mitochondrial dynamics imbalance skewed towards excessive fission. The result is a fragmented mitochondrial network characterized by small, punctate organelles that are bioenergetically inefficient and more susceptible to apoptosis. This loss of metabolic flexibility and interconnectivity further deepens the energetic crisis in the failing diabetic heart.

3.1.2.5 Sustained ER stress

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and mitochondria are physically and functionally connected at mitochondria-associated membranes (MAMs), where they exchange Ca2+. Disruption of this ER-mitochondria Ca2+ crosstalk in DCM, often due to the structural and functional defects mentioned earlier, leads to sustained ER stress. The accumulation of unfolded proteins in the ER activates the unfolded protein response (UPR) pathways (PERK, IRE1α, ATF6). Chronic UPR activation exacerbates insulin resistance, promotes apoptosis, and further worsens cellular Ca2+ handling defects, creating a feed-forward loop of cellular injury and aggravated contractile dysfunction.

3.1.2.6 Microvascular dysfunction

The impact of mitochondrial Ca2+ dysregulation extends beyond cardiomyocytes to cardiac endothelial cells. In these cells, similar dysregulation, compounded by insults from AGEs and ROS, contributes to microvascular dysfunction. This manifests as reduced nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability, increased endothelial permeability, inflammation, and impaired vasodilation. The resulting compromise in coronary microcirculation leads to myocardial ischemia and a perfusion-contraction mismatch, further starving cardiomyocytes of oxygen and nutrients and exacerbating the core pathology of DCM.

3.2 Key pathways/mechanisms underlying mitochondrial calcium dysregulation in DCM

3.2.1 Energy metabolism impairment

McCormack, J.G., and colleagues demonstrated the reduction in activity of the Ca2+-dependent dehydrogenase OGDH (69). Inhibited mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake obstructs the TCA cycle (70). This leads to decreased ATP production and consequent reduction in myocardial contractility (71).

3.2.1.1 Exacerbated oxidative stress

Ca2+ overload induces excessive ROS generation (72), causing oxidative damage to mitochondrial proteins, lipids, and DNA (73). This establishes a vicious cycle of mitochondrial dysfunction and progressive oxidative injury (81). Mitochondrial calcium dysregulation exacerbates oxidative stress in diabetic cardiomyopathy through converging mechanisms, with the core pathways summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Mechanisms of oxidative stress exacerbation by mitochondrial Ca2+ dysregulation in DCM. Ca2+, ROS, and ATP engage in a close, dynamic, and bidirectional interplay at both mitochondrial and cellular levels, forming a core pathological network in DCM. Under diabetic conditions, they form a vicious cycle, particularly characterized by Ca2+ overload triggering ROS production, which further disrupts Ca2+ homeostasis and energy metabolism. Mitochondria serve as the primary site of convergence for these factors. Their internal dynamics—such as mPTP opening and changes in ΔΨm—combined with the unique ROS-induced ROS release (RIRR) mechanism, enable rapid amplification of minor perturbations, ultimately leading to a drastic switch in cellular fate. Potential therapeutic strategies to break this cycle are highlighted: (1) Inhibition of the Mitochondrial Calcium Uniporter (MCU) to reduce pathological Ca2+ influx; (2) Activation of the mitochondrial Na+/Ca2+/Li+ Exchanger (NCLX) to enhance Ca2+ efflux. MCU, Mitochondrial Calcium Uniporter; NCLX, Mitochondrial Na+/Ca2+/Li+ Exchanger; mPTP, Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore; ETC, Electron Transport Chain; SERCA, Sarco/Endoplasmic Reticulum Ca2+-ATPase; ROS, Reactive Oxygen Species; RIRR, ROS-Induced ROSRelease.

3.2.1.2 Pathological mPTP opening

Ca2+ overload serves as the primary trigger for mPTP opening (74). Sustained opening results in mitochondrial swelling and rupture, cytochrome c release, and activation of cardiomyocyte apoptosis and necrosis (75). And myocyte loss and cardiac fibrosis. Pathological opening of the mPTP triggers a lethal cascade in myocardial cells, with the resultant pathological outcomes depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Pathological consequences of mPTP opening in DCM. Ca2+ directly binds to CypD and induces its conformational change; the Ca2+-CypD complex targets the F-ATP synthase (involving the F-ATP synthase pore-forming hypothesis), leading to mPTP opening and triggering a pathological cascade reaction. Ca2+, Calcium; Cyp D, Cyclophilin D; Mptp, Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore; ROS, Reactive Oxygen Species.

3.2.1.3 Abnormal calcium signaling

The interplay between cytosolic and mitochondrial Ca2+ handling is crucial. Dysregulation of SERCA2a, as occurs in DCM, delays cytosolic Ca2+ clearance during diastole, contributing to diastolic dysfunction. This persistent elevation in cytosolic Ca2+ can, in turn, lead to passive, pathological loading of mitochondria, especially if the MCU complex is dysregulated. Recent studies higdemonstrate that in DCM, the coexistence of reduced MCU expression and impaired SERCA2a function leads to a mishandling of Ca both compartments, severely compromising excitation-contraction coupling and overall cardiac performance (76–78, 82).

3.3 Pathological interconnections with diabetic metabolic dysregulation

Scholars summarize four major injury axes in diabetes: glucotoxicity, lipotoxicity, oxidative stress, and insulin resistance. Through crosstalk, they collectively suppress the calcium homeostasis network (83).

In greater detail:

Glucotoxicity: Suarez and his team discovered that high glucose activates PKCβ, which phosphorylates the MCU subunit (MiCu1) at Ser57, inhibiting calcium uptake capacity (↓40%), leading to cardiomyocyte energy metabolism disorders (84).

Advanced Glycation End Products (AGEs): Bidasee, K. R., and his team found that AGEs, via RAGE activation, inhibit SERCA activity, resulting in passive mitochondrial Ca2+ overload (85).

Oxidative Stress: In the pathogenic mechanisms of diabetes, oxidative stress has a significant influence. Seifer, D. R., and his team discovered that the PERK-ATF4 axis downregulates MICU1 expression, causing dysregulated mitochondrial calcium uptake (79). High glucose-induced ROS activates PKCδ to phosphorylate CypD at Ser191, lowering the mPTP opening threshold (ΔΨm collapse accelerated 3-fold) (86).

Lipotoxicity and Insulin Resistance: Anderson, E. J., and their team discovered that abnormal fatty acid metabolism inhibits NCLX activity (87).

Collectively, these diabetic injury axes converge on the molecular machinery of mitochondrial Ca2+ homeostasis, making it a final common pathway translating systemic metabolic insults into overt cardiac disease.

3.4 Clinical translation: diagnostic and therapeutic implications

The dysregulation of mitochondrial Ca2+ homeostasis identified in DCM presents significant opportunities for advancing clinical management. Critically, specific dysregulation patterns—such as reduced MCU expression in myocardial biopsies from T2DM patients (58) and heightened mPTP sensitivity in preclinical models (60, 61)—may serve as novel stratification biomarkers. These could identify high-risk individuals progressing from subclinical cardiac dysfunction to overt heart failure, a transition observed in ~29% of asymptomatic T2DM patients within 5 years (7).

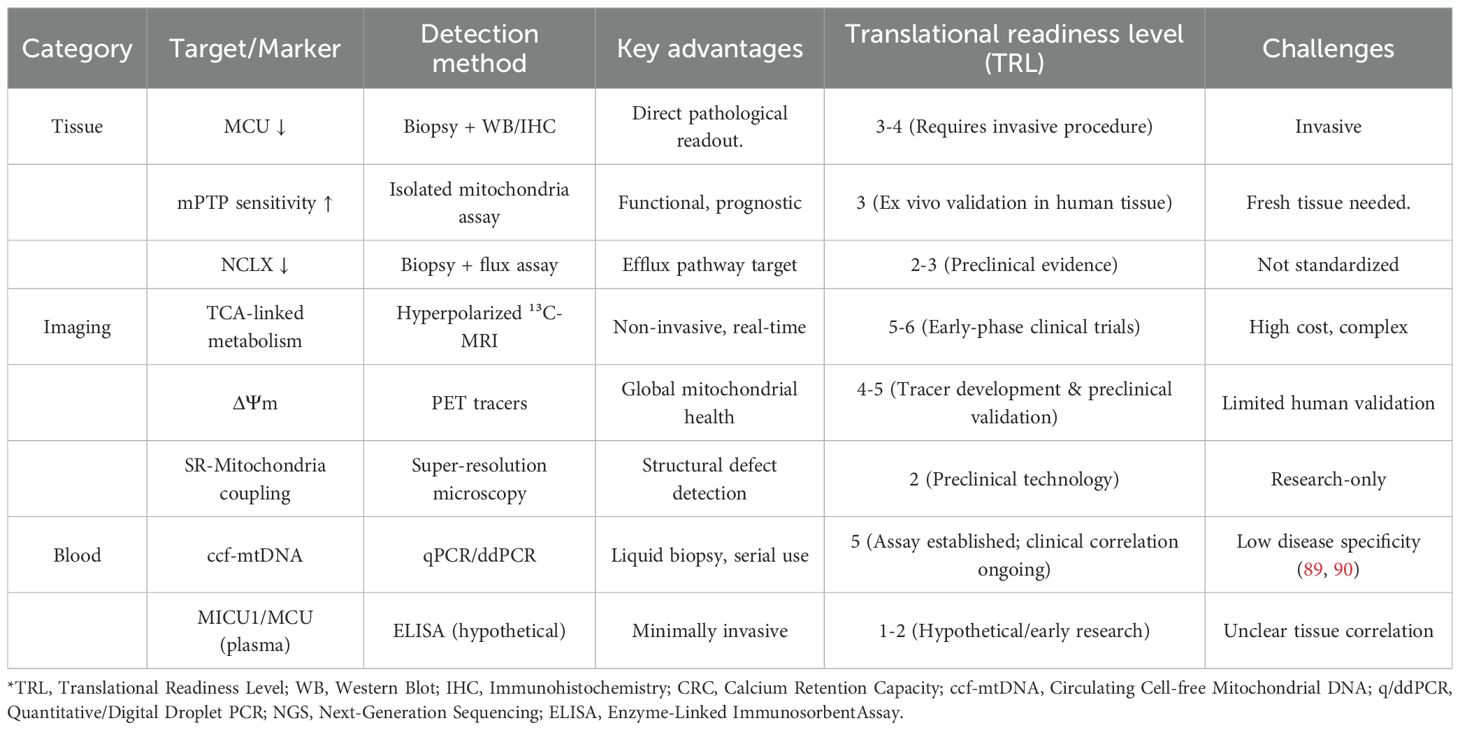

However, current clinical tools (e.g., echocardiography, serum BNP) lack the sensitivity to evaluate mitochondrial Ca2+ handling directly. Emerging noninvasive techniques—such as hyperpolarized ¹³C-MRI probing calcium-associated metabolic disturbances (88) or mitochondria-targeted PET tracers—hold promise for bridging this gap. It is very important to test these methods against histological gold standards, such as MCU protein quantification in biopsies. Building upon these emerging imaging techniques, a multi-modal biomarker approach is crucial for the early detection, risk stratification, and therapeutic monitoring of DCM. Table 2 summarizes a range of possible biomarkers based on mitochondrial calcium dysregulation. It compares their detection methods, benefits, and how ready they are for use in clinical settings. The “Translational Readiness Level” (TRL) is scored on a 1–9 scale, where 1–3 indicates basic research, 4–6 indicates clinical assay development/validation, and 7–9 indicates routine clinical application.

Table 2. Potential diagnostic biomarkers of mitochondrial calcium dysregulation in diabetic cardiomyopathy.

Therapeutically, the identification of such biomarkers would enable stage-specific interventions. For instance, patients with predominant MCU downregulation and bioenergetic deficit (e.g., early-stage DCM) might benefit from strategies to augment mitochondrial Ca2+uptake. In contrast, those with evidence of heightened mPTP sensitivity or impaired NCLX function (e.g., advanced DCM) could be prioritized for trials with mPTP inhibitors or NCLX activators, respectively. The development of these biomarkers is therefore not merely diagnostic but foundational to a precision medicine approach for DCM.

Therapeutically, stage-specific interventions are warranted:

Early-stage DCM (compensatory phase): Augmenting mitochondrial Ca2+uptake [e.g., via AMP-activated Protein Kinase AMPKγ1/PGC-1α axis activation (91)] may correct bioenergetic insufficiency.

Advanced DCM (decompensated phase): Inhibiting mPTP opening (e.g., CypD-targeted agents) or enhancing Ca2+ efflux [e.g., NCLX activators (92)] could attenuate cardiomyocyte loss.

Clinical trials should prioritize agents with cardioselectivity [e.g., MCU-i4 (93)] to minimize off-target effects.

4 Therapeutic strategies targeting mitochondrial calcium homeostasis

Table 3 summarizes recent advances in the pharmacological modulation of mitochondrial Ca2+ flux. Key strategies include direct MCU inhibition, MICU1 modulation, NCLX activation, mPTP inhibition, targeting, and mitochondrial antioxidants with distinct efficacy and safety profiles.

Table 3. Pharmacological strategies targeting mitochondrial calcium homeostasis in cardiac and non-cardiac models.

4.1 MitoQ: mitochondria-targeted antioxidant

4.1.1 Inhibiting mitochondrial Ca2+ overload/restoring physiological uptake

4.1.1.1 MCU inhibitors

Research on MCU inhibitors has yielded progress while also revealing temporary limitations. Xie, Y., and colleagues discovered that the novel inhibitor Ru265 (IC50=28 nM) mitigated calcium overload post-myocardial infarction (mitochondrial [Ca2+] ↓62%), but >5 mg/kg dosing caused a 40% decline in murine exercise endurance (94). Although not tested in a pure DCM model, the cardiac-specific MCU inhibitor MCU-i4 shows promise in ischemia-reperfusion injury models, a common comorbidity in patients with diabetes. It reduced infarct size by 35% without detectable hepatorenal toxicity (93). Researchers are still looking into the translational potential of MCU inhibition. Recent studies have further elucidated the role of MCU in cardiac physiology and disease, confirming its inhibition as a potent strategy to protect against calcium overload injury in various models, including ischemia-reperfusion (102). A particularly promising development is the emergence of novel, tissue-specific MCU inhibitors designed to minimize systemic side effects, as highlighted in recent preclinical assessments (103). However, the critical challenge remains in achieving a therapeutic window that mitigates pathology without compromising physiological energy production, especially in the chronic setting of DCM.

4.1.1.2 MICU 1/2 functional regulation

Researchers targeting MICU1/2 functional regulation have achieved significant progress. MICU1 overexpression improved mitochondrial function in diabetic cardiomyopathy (ATP ↑50%) by stabilizing cristae structure—an effect distinct from MCU regulation (95). Conversely, Tomar, D., and team found that whole-body MICU1 knockout exacerbated sepsis-induced cardiac dysfunction, while cardiac-specific overexpression required precise dose control (*>2-fold expression induced contractile suppression*) (92).

4.1.1.3 NCLX activation strategies

Research on NCLX activation strategies has become a prominent focus. Luongo, T. S., and colleagues showed that AAV9-NCLX therapy increased the rate at which calcium leaves the mitochondria by 70% and the left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) by 25% (P<0.01) in heart failure models (96). Concurrently, studies revealed that the compound NCLX-273 (EC50=0.15 μM) selectively activates renal tubular NCLX, mitigating acute kidney injury while exhibiting significantly reduced cardiotoxicity compared to CGP-37157 (97).

4.1.1.3 Inhibition of mPTP opening

Research has revealed the therapeutic potential of mPTP inhibitors, though limitations persist. Atar, D., and team demonstrated that the CsA analog TRO40303 reduced infarct size by 18% (*P=0.03*) in diabetic STEMI patients yet failed to improve long-term LVEF and resulted in a 2.4-fold increase in nephrotoxicity incidence (98). Complementarily, Karch, J.’s group found Sanglifehrin A attenuated myocardial fibrosis by 40%, but its <5% oral bioavailability necessitates nano-carrier delivery systems (99).

4.1.1.4 Mitochondrial-targeted antioxidant therapy

Researchers targeting mitochondrial antioxidants have mitigated Ca2+-induced ROS damage with nuanced outcomes. Dare, A. J., and team demonstrated that MitoTEMPO (1.5 mg/kg) reduced mitochondrial ROS by 65% and improved diastolic function (E/e’ ↓28%) in diabetic hearts, yet failed to reverse fibrosis (100). Zielonka, J.’s group uncovered a paradoxical effect: chronic MitoQ administration suppressed mitophagy (PINK1/Parkin pathway ↓40%), accelerating myocardial damage in aging models (101).

4.1.1.5 Counteracting mitochondrial metabolic dysregulation

Current hypoglycemic/lipid-modulating drugs demonstrate potential indirect protective effects on mitochondrial Ca2+ homeostasis. Lopaschuk, G. D.’s team demonstrated that empagliflozin reduces mitochondrial calcium overload risk by elevating ketone body β-HB (calcium transient amplitude ↓25%) (104). Pugazhenthi, S.’s group indicated that liraglutide activates PKA, thereby enhancing MCU closure threshold (*calcium overload threshold ↑3-fold*) (105). Foretz, M., and colleagues found that metformin inhibits the MCU complex via AMPK (calcium uptake ↓30%), while potentially exacerbating energy crises in heart failure patients (106).

4.2 Emerging next-generation therapeutic strategies

Zaha, V. G., and their team discovered that AAV9-mediated AMPKγ1 overexpression enhances PGC-1α activity, improving calcium handling in DCM (calcium transient decay accelerated by 40%) (91). Rocha, A. G., and their team discovered that delivering a Mitofusin 2 (MFN2) agonist using the mitochondria-targeted peptide SS-31 restores mitochondrial fusion in diabetic cardiomyopathy (fission/fusion ratio decreased by 60%), resulting in a doubled mPTP opening threshold (80).

Comparative analysis of mitochondrial calcium-targeting strategies reveals distinct advantages and limitations. MCU inhibition (e.g., MCU-i4) effectively prevents calcium overload but risks impairing physiological energy production, creating a therapeutic window challenge. In contrast, NCLX activation enhances calcium efflux without compromising uptake, offering a more physiological approach, but it faces specificity hurdles. The translation of these strategies from preclinical models to clinical practice faces several barriers: (1) species differences in calcium handling proteins, (2) the dynamic nature of the diabetic metabolic milieu that alters drug responses, and (3) the heterogeneity of DCM progression stages requiring personalized approaches. Notably, while MCU inhibitors show promise in acute injury models, NCLX activators may be better suited for chronic DCM management where calcium efflux capacity is progressively impaired.

4.2.1 Comparative analysis of mitochondrial calcium-targeting therapeutic strategies

While the array of therapeutic strategies targeting mitochondrial calcium is expanding, a critical and comparative evaluation reveals distinct advantages, limitations, and potential synergies.

4.2.1.1 MCU inhibition vs. NCLX activation

This represents a fundamental philosophical dichotomy in therapeutic approach. MCU inhibition (e.g., with MCU-i4) is primarily a preventive strategy, aiming to block the entry point of calcium during pathological overload, as seen in ischemia-reperfusion injury. Its main strength is that it works well in emergency situations. However, its major limitation is the “therapeutic window” challenge; since MCU is essential for physiological energy production, excessive or chronic inhibition risks exacerbating the bioenergetic deficit that characterizes DCM. In contrast, NCLX activation is a corrective or facilitative strategy. It does not interfere with physiological uptake but enhances the clearance of excess calcium, thereby breaking the cycle of overload. This makes it theoretically more suitable for chronic conditions like DCM, where efflux mechanisms are progressively impaired. The translational hurdle for NCLX activators lies in achieving tissue and context specificity to avoid systemic disturbances in calcium signaling.

4.2.1.2 Stage-specific considerations

The choice of strategy may be critically dependent on the stage of DCM. In early-stage DCM, characterized by impaired calcium uptake and bioenergetic deficit, strategies to augment physiological uptake (e.g., via AMPK/PGC-1α activation) or stabilize the MCU complex might be beneficial. Conversely, in advanced DCM, where calcium overload and mPTP sensitization dominate, MCU inhibitors, NCLX activators, or mPTP blockers would be more logical choices. This underscores the necessity of precision medicine and reliable biomarkers to stratify patients.

4.2.1.3 Combination therapies

Given the complexity of DCM, multitarget approaches may be required. For instance, a combination of a mild MCU modulator (to prevent severe overload) with an NCLX activator (to promote efflux) and a mitochondrial antioxidant (to reduce ROS-triggered mPTP opening) could offer synergistic benefits, potentially at lower, safer doses of each agent. However, the combination also increases the risk of unforeseen off-target effects and necessitates sophisticated pharmacokinetic studies.

5 Challenges and future directions

The translation of mitochondrial calcium homeostasis as a therapeutic target from compelling preclinical data to clinical reality for DCM patients is fraught with challenges. This section delineates the principal barriers and outlines promising avenues for future research.

5.1 The specificity and safety hurdle of pharmacological intervention

A primary concern in targeting mitochondrial calcium fluxes is achieving therapeutic efficacy without disrupting physiological function. MCU inhibitors exemplify this “double-edged sword” effect. While they potently prevent pathological calcium overload, their chronic use risks exacerbating the pre-existing bioenergetic deficit that characterizes DCM by blunting the calcium signals essential for stimulating ATP production (107, 108). Furthermore, systemic inhibition of a ubiquitous protein like MCU may incur off-target effects in other high-energy-demand tissues, such as skeletal muscle and neurons. Therefore, the development of cardiac-targeted delivery systems (e.g., using cardiotropic viral vectors or nanoparticle carriers) or conditionally activatable prodrugs (designed to be active only in the pathological microenvironment, e.g., during excessive ROS or Ca2+ levels) is a critical future direction (93, 107).

5.2 Heterogeneity in mitochondrial calcium dysregulation across different stages of DCM

DCM is a progressive disease, and the nature of mitochondrial calcium dysregulation evolves with its stages. In the early compensatory phase, the primary defect is often impaired mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake due to downregulation of the MCU complex and PGC-1α. This condition leads to a bioenergetic deficit but not overt overload. The heart may try to make up for it in other ways. However, as the disease advances to the decompensated phase, chronic metabolic stress and cellular damage predispose the myocardium to pathological Ca2+ overload. This process is characterized by increased susceptibility to mPTP opening, exacerbated by oxidative stress and the dysregulation of efflux pathways like NCLX. Wu, S., and their team gave us important information by demonstrating stage-specific regulatory mechanisms, such as FBXL4-mediated degradation of MCU in the decompensated phase, which fundamentally alters the mitochondrial calcium handling phenotype (109, 110). This heterogeneity necessitates stage-specific therapeutic interventions.

5.3 Bridging the translational gap: from animal models to human DCM

A significant barrier to clinical progress is the limited predictive value of current preclinical models. Rodent models of diabetes (e.g., db/db mice, STZ rats) capture certain metabolic features but fail to fully recapitulate the chronic, multi-factorial nature of human DCM, which develops over decades amidst complex genetic backgrounds and comorbidities.

Key limitations include:

● Species Differences: The expression, regulation, and relative importance of proteins like MCU and NCLX can differ between rodents and humans.

● Model Uniformity vs. Patient Heterogeneity: Genetically uniform animal models do not reflect the vast heterogeneity of human DCM, leading to over-optimistic drug efficacy that fails in diverse clinical populations.

● The Dynamic Diabetic Milieu: Preclinical testing often occurs in a stable metabolic state, unlike the fluctuating glucose, insulin, and adipokine levels in patients, which can profoundly alter drug responses.

● To bridge this gap, future research must prioritize:

● Human-Relevant Models: Utilizing induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes (iPSC-CMs) from diabetic patients with and without cardiomyopathy.

● Comorbidity-Incorporated Designs: Testing drug efficacy in models that combine diabetes with other common comorbidities like hypertension or aging.

● Biomarker-Driven Stratification: The discovery and validation of non-invasive biomarkers (as proposed in Table 2) are paramount for identifying responsive patient subpopulations in clinical trials.

5.4 The rationale for multitarget combination therapies

Given the complex, interconnected pathology of DCM, simultaneously targeting multiple nodes in the mitochondrial calcium network may yield synergistic benefits. Hamilton, S., and colleagues provided a proof-of-concept, demonstrating that dual inhibition of the inositol trisphosphate receptor (IP3R) and MCU was more effective in modulating mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in heart failure than either approach alone (111). Logical combinations for DCM could include a mild MCU modulator (to prevent severe overload) with an NCLX activator (to enhance clearance) and a mitochondrial antioxidant (to reduce ROS-mediated mPTP sensitization). However, such strategies require sophisticated pharmacokinetic and safety studies to avoid unforeseen off-target effects.

5.5 Harnessing novel technologies for mechanistic insight and drug discovery

Cutting-edge technologies stand poised to transform the future of DCM research and therapy development:

● Single-Cell and Spatial Omics: Technologies like scRNA-seq are already illuminating the cellular heterogeneity of the failing heart, identifying distinct cardiomyocyte subpopulations with unique calcium handling gene expression profiles (112). This makes it possible to find new cell-specific targets and biomarkers.

● Advanced Imaging: Real-time mitochondrial calcium monitoring with improved genetically encoded indicators (e.g., mtGCaMP) and hyperpolarized ¹³C-MRI, which can probe calcium-related metabolic fluxes, offer non-invasive windows into mitochondrial function in vivo (88, 113).

● Artificial Intelligence (AI): AI-driven drug design is breaking new ground in targeting complex proteins, like the MCU complex (114). AI-designed allosteric inhibitors have demonstrated effectiveness in alleviating mitochondrial calcium overload in heart failure models (115), and quantum machine learning is currently facilitating the precise prediction of drug-channel interactions (116).

6 Conclusions

Mitochondrial calcium homeostasis has emerged from the periphery to claim its position as a central integrator in the pathogenesis of diabetic cardiomyopathy. It functions as a critical signaling nexus, translating the systemic metabolic insults of diabetes—hyperglycemia, lipotoxicity, oxidative stress, and insulin resistance—into the cardinal features of myocardial dysfunction: bioenergetic deficit, oxidative injury, and cardiomyocyte loss. The diabetic environment directly attacks the molecular machinery that controls mitochondrial calcium. This causes problems with uptake through the MCU complex, sensitized efflux through the mPTP, and dysregulated extrusion through NCLX.

The therapeutic landscape is evolving to target this hub, but our analysis reveals that the choice of strategy is not trivial. The fundamental dichotomy between MCU inhibition (a preventive strategy against overload) and NCLX activation (a corrective strategy to enhance efflux) represents a critical trade-off between preventing toxicity and maintaining physiological energy production. The optimal choice varies depending on the stage of DCM and the predominant nature of the calcium handling defect in a particular patient.

Therefore, the path forward must be guided by precision medicine. Success will depend on our ability to leverage emerging technologies—from single-cell omics and AI to advanced imaging—to develop reliable biomarkers for patient stratification and to design cardioselective therapies that are effective within the complex, dynamic metabolic context of diabetes. Ultimately, safeguarding the mitochondrial calcium gateway may be the key to protecting the diabetic heart and altering the devastating cardiovascular destiny of millions of patients worldwide.

Author contributions

SD: Writing – original draft. FT: Writing – original draft. YJ: Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Generative AI tools were used to assist with language translation and text editing; all content has been verified by the authors.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

AHA, American Heart Association; AAV9, Adeno-Associated Virus serotype 9; AGEs, Advanced Glycation End products; AMPK, AMP-activated Protein Kinase; ATP, Adenosine Triphosphate; Bax, BCL2-Associated X protein; β-HB, β-Hydroxybutyrate; Ca2+, Calcium; Casp3, Caspase 3; CypD, Cyclophilin D; Cyt c, Cytochrome c; DCM, Diabetic Cardiomyopathy; DM, Diabetes Mellitus; ΔΨm, Mitochondrial Membrane Potential; EC50, Half-Maximal Effective Concentration; EMRE, Essential MCU Regulator; ETC, Electron Transport Chain; FBXL4, F-Box and Leucine-Rich Repeat Protein 4; F-ATP synthase, FoF1-ATP Synthase; HF, Heart Failure; H+/Ca2+ exchanger, Proton/Calcium Exchanger; IC50, Half-Maximal Inhibitory Concentration; IDH3, Isocitrate Dehydrogenase 3; IMM, Inner Mitochondrial Membrane; JPH2, Junctophilin-2; MCU, Mitochondrial Calcium Uniporter; MCUR1, Mitochondrial Calcium Uniporter Regulator 1; MICU1/2/3, Mitochondrial Calcium Uptake protein 1/2/3; mNCX, Mitochondrial Na+/Ca2+ Exchanger; mPTP, Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore; Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX), Sodium/Calcium Exchanger; NCLX, Mitochondrial Na+/Ca2+/Li+ Exchanger; RIRR, ROS-Induced ROS Release; ROS, Reactive Oxygen Species; Ru265, MCU inhibitor compound; RyR, Ryanodine Receptor; T2D/T2DM, Type 2 Diabetes (Mellitus); ΔΨm, Mitochondrial Membrane Potential.

References

1. Dillmann WH. Diabetic cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. (2019) 124:1160–2. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.314665

2. World Health Organization. Global Report on Diabetes. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization (2016).

3. American Diabetes Association. Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease. Arlington: American Diabetes Association (2019).

4. International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas. 10th ed. Brussels: International Diabetes Federation (2021).

5. Paolillo S, Marsico F, Prastaro M, Dellegrottaglie S, Esposito L, Marciano C, et al. Diabetic cardiomyopathy: definition, diagnosis, and therapeutic implications. Heart Failure Clinics. (2019) 15:341–7. doi: 10.1016/j.hfc.2019.02.003

6. Lu Y, Zhang H, Teng D, Liu L, Chen L, Wang Y, et al. Prevalence and prognosis of subclinical diabetic cardiomyopathy: a prospective cohort study using cardiac MRI. JACC: Cardiovasc Imaging. (2022) 15:1462–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2022.02.016

7. Jensen MT, Søgaard P, Andersen HU, Bech J, Hansen TF, Jørgensen PG, et al. Progression of diabetic cardiomyopathy in type 1 diabetes: the FinnDiane study. Diabetes Care. (2021) 44:2050–6. doi: 10.2337/dc21-0092

8. Jia G, Hill MA, and Sowers JR. Diabetic cardiomyopathy: an update of mechanisms contributing to this clinical entity. Circ Res. (2018) 122:624–38. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.311586

9. Seferović PM, Petrie MC, Filippatos GS, Anker SD, Rosano G, Bauersachs J, et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and heart failure: a position statement from the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Failure. (2018) 20:853–72. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1170

10. Chen D, Sindone A, Huang MLH, Peter K, and Jenkins AJ. Diabetic cardiomyopathy: insights into pathophysiology, diagnosis and clinical management. J Mol Cell Cardiol. (2025) 206:55–69. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2025.06.013

11. Roth GA, Mensah GA, Johnson CO, Addolorato G, Ammirati E, Baddour LM, et al. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk factors, 1990–2019: update from the GBD 2019 study. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2020) 76:2982–3021. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.11.010

12. Roth GA, Mensah GA, Johnson CO, Addolorato G, Ammirati E, Baddour LM, et al. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk factors, 1990–2022: update from the GBD 2022 study. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2024) 83:2619–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2024.03.543

13. Murarka S and Movahed MR. Diabetic cardiomyopathy. J Cardiac Failure. (2020) 26:291–303. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2019.12.017

14. Tan Y, Zhang Z, Zheng C, Wintergerst KA, Keller BB, and Cai L. Mechanisms of diabetic cardiomyopathy and potential therapeutic strategies: preclinical and clinical evidence. Nat Rev Cardiol. (2020) 17:585–607. doi: 10.1038/s41569-020-0339-2

15. Mann C, Braunwald E, and Zelniker TA. Diabetic cardiomyopathy revisited: The interplay between diabetes and heart failure. Int J Cardiol. (2025) 438:133554. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2025.133554

16. Tan Y, et al. Diabetic cardiomyopathy: from molecular mechanisms to therapeutic strategies. J Mol Cell Biol. (2023) 15:mjad041. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjad041

17. Santulli G, Xie W, Reiken SR, and Marks AR. Mitochondrial calcium overload is a key determinant in heart failure. Proc Natl Acad Sci United States America. (2015) 112:11389–94. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1513047112

18. Dorn GW 2nd and Kitsis RN. The mitochondrial dynamism–mitophagy–cell death interactome in heart failure. Circ Res. (2020) 127:1051–3. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.317777

19. Kim JC, Son MJ, and Woo SH. Regulation of cardiac calcium by mechanotransduction: role of mitochondria. Arch Biochem Biophysics. (2018) 659:33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2018.09.021

20. Vásquez-Trincado C, García-Carvajal I, Pennanen C, Parra V, Hill JA, Rothermel BA, et al. Mitochondrial dynamics, mitophagy, and cardiovascular disease. J Physiol. (2016) 594:509–25. doi: 10.1113/JP271301

21. Griffiths EJ, Balaska D, and Cheng WHY. The ups and downs of mitochondrial calcium signalling in the heart. Biochim Biophys Acta. (2010) 1797:856–64. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.04.004

22. Finkel T, Menazza S, Holmström KM, Parks RJ, Liu J, Sun J, et al. The ins and outs of mitochondrial calcium. Circ Res. (2015) 116:1810–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.305484

23. Choudhury P, Kosuru R, and Cai Y. Editorial: The complex phenotype of diabetic cardiomyopathy: clinical indicators and novel treatment targets. Front Endocrinol. (2024) 15:1497352. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2024.1497352

24. Camara AKS, Zhou Y, Wen PC, Tajkhorshid E, and Kwok WM. Mitochondrial VDAC1: a key gatekeeper as potential therapeutic target. Front Physiol. (2017) 8:460. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2017.00460

25. Pathak T and Trebak M. Mitochondrial Ca2+ signaling. Pharmacol Ther. (2018) 192:112–23. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2018.07.003

26. Molnár MJ and Kovács GG. Mitochondrial diseases. Handb Clin Neurol. (2017) 145:147–55. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-802395-2.00010-9

27. Zhou B and Tian R. Mitochondrial dysfunction in the pathophysiology of heart failure. J Clin Invest. (2018) 128:3716–26. doi: 10.1172/JCI120849

28. Demaurex N and Rosselin M. Redox control of mitochondrial calcium uptake. Mol Cell. (2017) 65:961–2. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.03.010

29. Samanta K, Mirams GR, and Parekh AB. Sequential forward and reverse transport of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger generates Ca2+ oscillations within mitochondria. Nat Commun. (2018) 9:156. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02638-2

30. Feno S, Butera G, Vecellio Reane D, Rizzuto R, and Raffaello A. Crosstalk between calcium and ROS in pathophysiological conditions. Oxid Med Cell Longevity. (2019) 2019:9324018. doi: 10.1155/2019/9324018

31. Stoll S, Xi J, Ma B, Leimena C, Behringer EJ, Qin G, et al. The valosin-containing protein protects the heart against pathological Ca2+ overload by modulating Ca2+ uptake proteins. Toxicological Sci. (2019) 168:450–67. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfz009

32. Rizzuto R, De Stefani D, Raffaello A, and Mammucari C. Mitochondria as sensors and regulators of calcium signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. (2012) 13:566–78. doi: 10.1038/nrm3412

33. Liu JC. Is the MCU indispensable for normal heart function? J Mol Cell Cardiol. (2020) 143:175–83. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2020.04.034

34. Lee SK, Shanmughapriya S, Mok MCY, Dong Z, Tomar D, Carvalho E, et al. Structural insights into mitochondrial calcium uniporter regulation by divalent cations. Cell Chem Biol. (2016) 23:1157–69. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2016.07.012

35. Baughman JM, Perocchi F, Girgis HS, Plovanich M, Belcher-Timme CA, Sancak Y, et al. Integrative genomics identifies MCU as an essential component of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Nature. (2011) 476:341–5. doi: 10.1038/nature10234

36. De Stefani D, Raffaello A, Teardo E, Szabo I, and Rizzuto R. A forty-kilodalton protein of the inner membrane is the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Nature. (2011) 476:336–40. doi: 10.1038/nature10230

37. Marchi S and Pinton P. The mitochondrial calcium uniporter complex: molecular components, structure and physiopathological implications. J Physiol. (2014) 592:829–39. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.268235

38. Wang Y, Nguyen NX, She J, Zeng W, Yang Y, Bai XC, et al. Structural mechanism of EMRE-dependent gating of the human mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Cell. (2019) 177:1252–1261.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.03.050

39. Fan C, Fan M, Orlando BJ, Fastman NM, Zhang J, Xu Y, et al. Structural basis of the MICU1-MICU2 heterodimer interface in MCU regulation. Nature. (2020) 585:641–6. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2679-9

40. Bernardi P, Rasola A, Forte M, and Lippe G. The mitochondrial permeability transition pore: channel formation by F-ATP synthase, integration in signal transduction, and role in pathophysiology. Physiol Rev. (2015) 95:1111–55. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00001.2015

41. Baines CP, Kaiser RA, Sheiko T, Craigen WJ, and Molkentin JD. Voltage-dependent anion channels are dispensable for mitochondrial-dependent cell death. Nat Cell Biol. (2007) 9:550–5. doi: 10.1038/ncb1575

42. Wu Y, Rasmussen TP, Koval OM, Joiner MLA, Hall DD, Chen B, et al. The mitochondrial uniporter controls fight or flight heart rate increases. Nat Commun. (2015) 6:6081. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7081

43. Mnatsakanyan N, Llaguno MC, Yang Y, Yan J, Weber J, Sigworth FJ, et al. A mitochondrial megachannel resides in monomeric F1FO ATP synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci United States America. (2019) 116:19963–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1904776116

44. Palty R, Silverman WF, Hershfinkel M, Caporale T, Sensi SL, Parnis J, et al. NCLX is an essential component of mitochondrial Na+/Ca2+ exchange. Cell Metab. (2010) 12:54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.05.011

45. Kwong JQ, Huo J, Bround MJ, Boyer JG, Schwan J, Oydanich M, et al. The mitochondrial phosphate carrier modulates cardiac metabolism and protects against ischemia-reperfusion injury. Nat Metab. (2021) 3:1382–96. doi: 10.1038/s42255-021-00468-7

46. Boyman L, Kekenes-Huskey PM, Lederer WJ, Marsh JD, Chatham JC, Lindert S, et al. Mitochondrial calcium buffering contributes to the maintenance of basal cardiac function. Circ Res. (2019) 124:664–78. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.313444

47. Glancy B and Balaban RS. Role of mitochondrial Ca2+ in the regulation of cellular energetics. Biochemistry. (2012) 51:2959–73. doi: 10.1021/bi2018909

48. Spinelli JB and Haigis MC. The multifaceted contributions of mitochondria to cellular metabolism. Nat Cell Biol. (2018) 20:745–54. doi: 10.1038/s41556-018-0124-1

49. Nemani N, Shanmughapriya S, and Madesh M. Molecular regulation of MCU: implications in physiology and disease. Cell Calcium. (2020) 87:102186. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2020.102186

50. Zorov DB, Juhaszova M, and Sollott SJ. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) and ROS-induced ROS release. Physiol Rev. (2014) 94:909–50. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00026.2013

51. Görlach A, Bertram K, Hudecova S, and Krizanova O. Calcium and ROS: a mutual interplay. Redox Biol. (2015) 6:260–71. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2015.08.010

52. Mráček T, Drahota Z, and Houštěk J. The function and the role of the mitochondrial glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase in mammalian tissues. Biochim Biophys Acta. (2013) 1827:401–10. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.11.014

53. Angelova PR and Abramov AY. Role of mitochondrial ROS in the brain: from physiology to neurodegeneration. FEBS Lett. (2018) 592:692–702. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.12964

54. Baines CP, Kaiser RA, Purcell NH, Blair NS, Osinska H, Hambleton MA, et al. Loss of cyclophilin D reveals a critical role for mitochondrial permeability transition in cell death. Nature. (2005) 434:658–62. doi: 10.1038/nature03434

55. Bonora M, Morganti C, Morciano G, Pedriali G, Lebiedzinska-Arciszewska M, Aquila G, et al. Mitochondrial permeability transition involves dissociation of F1FO ATP synthase dimers and C-ring conformation. EMBO Rep. (2017) 18:1077–89. doi: 10.15252/embr.201643602

56. Kandula N, Kumar S, Mandlem VKK, Siddabathuni A, Singh S, and Kosuru R. Role of AMPK in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury-induced cell death in the presence and absence of diabetes. Oxid Med Cell Longevity. (2022) 2022:7346699. doi: 10.1155/2022/7346699

57. Lu Z, Jiang YP, Xu WH, Ballou LM, Cohen IS, and Lin RZ. Hyperglycemia acutely decreases mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in cardiac myocytes. Cardiovasc Diabetol. (2018) 17:151. doi: 10.1186/s12933-018-0795-8

58. Marques MD, Santos C, Costa T, Ferreira J, Oliveira M, Silva R, et al. Diabetes and cardiac fibrosis: a tissue-based post-mortem analysis with real-world data. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2022) 107:e2776–84. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgac234

59. Karamanlidis G, Bautista-Hernandez V, Feneley M, Garcia-Menendez L, Margulies KB, Tian R, et al. Defective DNA replication impairs mitochondrial biogenesis in human failing hearts. Circ Res. (2013) 112:673–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.300374

60. Liu T, Takimoto E, Dimaano VL, DeMazumder D, Kettlewell S, Smith G, et al. Inhibiting mitochondrial Na+/Ca2+ exchange prevents sudden death in a Guinea pig model of heart failure. Circ Res. (2014) 115:44–54. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.303062

61. Thandavarayan RA, Giridharan VV, Sari FR, Arumugam S, Pitchaimani V, Karuppagounder V, et al. Dominant-negative p38α mitogen-activated protein kinase prevents cardiac apoptosis and remodeling after streptozotocin-induced diabetes mellitus. Am J Physiology-Heart Circulatory Physiol. (2015) 309:H911–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00282.2015

62. Shi K, Wang F, Xia T, Wang X, Sun D, Jiang L, et al. PKCβII-activated NOX4-derived reactive oxygen species in cardiomyocytes induces mitochondrial damage and apoptosis during hyperglycemia. Free Radical Biol Med. (2020) 146:234–47. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2019.11.007

63. Pal PB, Roy SG, Chattopadhyay S, Bandyopadhyay A, Basu S, Pal P, et al. Glycated albumin suppresses myocardial contraction by antagonizing SERCA2a and impairing mitochondrial function. Biochem Pharmacol. (2022) 195:114862. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2021.114862

64. Zhang L, Cannell MB, Kim SJ, Watson PA, Roderick HL, and Bootman MD. Altered calcium homeostasis in the cardiac myocytes of dystrophin-deficient mdx mice. Cardiovasc Res. (2010) 87:63–73. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq021

65. Frustaci A, Kajstura J, Chimenti C, Jakoniuk I, Leri A, Maseri A, et al. Myocardial cell death in human diabetes. Circ Res. (2000) 87:1123–32. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.87.12.1123

66. Kho C, Lee A, Jeong D, Oh JG, Chaanine AH, Kizana E, et al. SUMO1-dependent modulation of SERCA2a in heart failure. Nature. (2022) 582:79–84. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04712-2

67. Santulli G, Pagano G, Sardu C, Xie W, Reiken S, D’Ascia SL, et al. Calcium release channel RyR2 regulates insulin release and glucose homeostasis. J Clin Invest. (2015) 125:1968–78. doi: 10.1172/JCI79273

68. Seidlmayer LK, Gomez-Garcia MR, Blatter LA, Pavlov E, and Dedkova EN. Inorganic polyphosphate is a potent activator of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore in cardiac myocytes. J Gen Physiol. (2012) 139:321–31. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201210788

69. Ritchie RH and Abel ED. Basic mechanisms of diabetic heart disease. Circ Res. (2020) 126:1501–25. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.315913

70. Garbincius JF and Elrod JW. Mitochondrial calcium exchange in physiology and disease. Physiol Rev. (2022) 102:893–992. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00041.2020

71. Brown DA, Perry JB, Allen ME, Sabbah HN, Stroud DM, Das S, et al. Mitochondrial function as a therapeutic target in heart failure. Nat Rev Cardiol. (2019) 16:33–44. doi: 10.1038/s41569-018-0079-8

72. Schofield JH and Schafer ZT. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and mitophagy: A complex and nuanced relationship. Antioxidants Redox Signaling. (2021) 34:517–30. doi: 10.1089/ars.2020.8058

73. Sies H and Jones DP. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) as pleiotropic physiological signalling agents. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. (2020) 21:363–83. doi: 10.1038/s41580-020-0230-3

74. Bernardi P and Di Lisa F. The mitochondrial permeability transition pore: molecular nature and role as a target in cardioprotection. J Mol Cell Cardiol. (2015) 78:100–6. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.09.023

75. Halestrap AP and Richardson AP. The mitochondrial permeability transition: a current perspective on its identity and role in ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Mol Cell Cardiol. (2015) 78:129–41. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.08.018

76. Liu T, Yang N, Sidor A, O'Rourke B, O'Rourke J, Sadoshima J, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in diabetic cardiomyopathy: The role of mitochondrial Ca2+. Circ Res. (2020) 126:1533–50. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.119.315432

77. Lu X, Ginsburg KS, Kettlewell S, Bossuyt J, Smith GL, and Bers DM. Measuring local gradients of intramitochondrial [Ca2+] in cardiac myocytes during sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release. Circ Res. (2013) 112:424–31. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.300501

78. Drago I, De Stefani D, Rizzuto R, and Pozzan T. Mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake contributes to buffering cytosolic Ca2+ peaks in cardiomyocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci United States America. (2012) 109:12986–91. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210718109

79. Seifer DR, Ly LD, Han X, Nassif NT, Johnson P, Ho P, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress activates PERK-ATF4 to induce mitophagy in diabetic hearts. Cardiovasc Res. (2021) 117:2367–82. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvaa271

80. Rocha AG, Franco A, Krezel AM, Rumsey JM, Alberti JM, Knight WC, et al. MFN2 agonists reverse mitochondrial fragmentation in diabetic cardiomyopathy. J Clin Invest. (2022) 132:e162357. doi: 10.1172/JCI162357

81. Indo HP, Yen HC, Nakanishi I, Matsumoto KI, Tamura M, Nagano Y, et al. A mitochondrial superoxide theory for oxidative stress diseases and aging. J Clin Biochem Nutr. (2015) 56:1–7. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.14-42

82. Gómez J, Santiago D, Martínez L, and Rodríguez P. Cardiomyocyte dysfunction in diabetic cardiomyopathy is mediated by mitochondrial calcium uniporter (MCU) and sodium/calcium/lithium exchanger (NCLX) imbalance. Diabetes. (2020) 69:1192–205. doi: 10.2337/db19-0999

83. Rrown DA and Griendling KK. Metabolic regulation of calcium signaling in cardiomyocytes: Implications for diabetic cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. (2022) 131:182–203. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.122.320448

84. Suarez J, Hu Y, Makino A, Fricovsky E, Wang H, and Dillmann WH. Alterations in mitochondrial Ca2+ handling in cardiac myocytes from diabetic db/db mice. Diabetes. (2013) 62:2921–30. doi: 10.2337/db12-1653

85. Eric JR, Bidasee KR, Uhl K, Zhang Y, Shao CH, Patel K, et al. Advanced glycation end products (AGEs) and receptor for AGEs (RAGE) in patients with diabetic cardiomyopathy. Diabetes. (2019) 68. doi: 10.2337/db19-175-LB

86. Javadov S, Jang S, and Agostini B. Mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening as an endpoint to initiate cell death and as a putative target for cardioprotection. Cell Physiol Biochem. (2014) 33:1363–81. doi: 10.1159/000358697

87. Hamilton S, Terentyeva R, Kim TY, Bronk P, Clements RT, Choi BR, et al. Combined inhibition of IP3R and MCU modulates mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2021) 77:195. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(21)01319-1

88. Rider OJ, Apps A, Miller JJJ, Lau JYC, Lewis AJM, Peterzan MA, et al. Non-invasive in vivo assessment of cardiac metabolism in the healthy and diabetic human heart using hyperpolarized ¹³C MRI. Circ Res. (2020) 126:725–36. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.119.316260

89. Li H, Yao W, and Liu Z. Circulating mitochondrial DNA as a potential biomarker for cardiac injury. Crit Care. (2020) 24:259. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-02974-8

90. Bredy C, Ministeri M, Kempny A, Alonso-Gonzalez R, Swan L, Uebing A, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction and cardiovascular disease: role of non-coding RNAs and liquid biopsy. J Am Heart Assoc. (2022) 11:e026711. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.122.026711

91. Zaha VG and Young LH. AMPK activation: a therapeutic target for type 2 diabetes? Diabetes Metab J. (2021) 45:516–28. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2021.0197

92. Tomar D, Thomas M, Garbincius JF, Kolmetzky DW, Salik O, Jadiya P, et al. MICU1 protects against sepsis-induced myocardial dysfunction by preventing calpain-mediated RyR2 degradation. Cell Death Dis. (2021) 12:899. doi: 10.1038/s41419-021-04194-6

93. Feng J, Zhu M, Schaub MC, Gehrig P, Roschitzki B, Lucchinetti E, et al. MCU-i4: a novel mitochondrial calcium uniporter inhibitor with cardioprotective effects. Br J Pharmacol. (2021) 178:2956–71. doi: 10.1111/bph.15487

94. Xie Y, Li J, Kang R, and Tang D. Mitochondrial calcium uniporter inhibitor Ru265 improves cardiac function in mice with acute myocardial infarction. J Am Heart Assoc. (2023) 12:e029123. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.122.029123

95. Zhang H, Wang P, Bisetto S, Yoon Y, Chen Q, Sheu SS, et al. MICU1 regulates mitochondrial cristae structure and function independent of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Circ Res. (2023) 132:999–1015. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.122.321994

96. Luongo TS, Lambert JP, Gross P, Nwokedi M, Lombardi AA, Shanmughapriya S, et al. Enhanced NCLX-dependent mitochondrial calcium efflux attenuates pathological remodeling in heart failure. JACC: Basic to Trans Sci. (2020) 5:786–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jacbts.2020.06.008

97. Nita II, Hershfinkel M, and Sekler I. Mitochondrial NCLX prevents calcium overload and necrosis in the renal tubules. Kidney Int. (2022) 101:990–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2021.12.034

98. Atar D, Arheden H, Berdeaux A, Bonnet JL, Carlsson M, Clemmensen P, et al. TRO40303 for myocardial protection in diabetic patients with STEMI: a post hoc analysis of the MITOCARE trial. Cardiovasc Diabetol. (2021) 20:132. doi: 10.1186/s12933-021-01326-2

99. Karch J, Bround MJ, Khalil H, Sargent MA, Latchman N, Terada N, et al. Inhibition of mitochondrial permeability transition by sanglifehrin A alleviates necrosis and fibrosis in pressure overload cardiomyopathy. Nat Commun. (2022) 13:4241. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-31942-9

100. Dare AJ, Logan A, Prime TA, Rogatti S, Goddard M, Bolton EM, et al. The mitochondria-targeted anti-oxidant MitoTEMPO improves cardiac function in diabetic cardiomyopathy. JACC: Basic to Trans Sci. (2021) 6:900–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jacbts.2021.09.005

101. Zielonka J, Joseph J, Sikora A, and Kalyanaraman B. Mitochondria-targeted triphenylphosphonium-based compounds: syntheses, mechanisms of action, and therapeutic and diagnostic applications. Chem Rev. (2017) 117:10043–120. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00042

102. Rajesh M, Mukhopadhyay P, Bátkai S, Patel V, Saito K, Matsumoto S, et al. Cannabidiol attenuates cardiac dysfunction, oxidative stress, fibrosis, and inflammatory and cell death signaling pathways in diabetic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2010) 56:2115–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.07.033

103. García-Rivas G, Lozano O, Bernal-Ramírez J, Silva-Platas C, Salazar-Ramírez F, Méndez-Fernández A, et al. Cannabidiol prevents heart failure dysfunction and remodeling through preservation of mitochondrial function and calcium handling. JACC. Basic to Trans Sci. (2025) 10:800–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jacbts.2024.12.009

104. Lopaschuk GD and Verma S. Mechanisms of cardiovascular benefits of SGLT2 inhibitors. Circ Res. (2020) 126:1586–602. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.316949