- 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Taichung Veterans General Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan

- 2Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, School of Medicine, National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University, Hsinchu, Taiwan

- 3Department of Public Health, Chung Shan Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan

- 4Department of Nursing, College of Nursing, HungKuang University, Taichung, Taiwan

Background: Patients with adenomyosis frequently experience menorrhagia and dysmenorrhea. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (LNG-IUD) and oral norethindrone are widely used non-surgical treatment options. However, their associated risks of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) and bacterial vaginosis (BV) have not been well reported in the previous studies.

Methods: This multi-institutional retrospective analysis was performed using de-identified electronic health records from the TriNetX Research Network. Patients with adenomyosis treated with LNG-IUD or oral norethindrone were identified. A 1:1 propensity score matching (PSM) was conducted to control for potential confounding variables. Subgroup analysis was performed to evaluate the outcomes of the patient group with hemoglobin (Hb) ≥10 g/dL or Hb <10 g/dL. Primary outcomes include risks of PID and BV. Secondary outcomes included risks of severe anemia (Hb < 10 g/dL), breast cancer, mood disorder, and cancer antigen 125 (CA-125) >35 U/mL.

Results: After PSM, the LNG-IUD group showed a significantly lower risk of PID (hazard ratio (HR) 0.545; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.483–0.616) and Hb <10 g/dL (HR 0.850; 95% CI 0.775–0.932) compared with the oral norethindrone group. In contrast, the risk of BV was significantly higher in the LNG-IUD group (HR 1.223; 95% CI 1.116–1.342). No significant differences were observed between the two groups regarding associated breast cancer, mood disorder, or CA-125 ≥ 35 U/mL.

Conclusion: This study demonstrated that in patients with adenomyosis, treatment with LNG-IUD, compared with oral norethindrone, was associated with a lower risk of PID and severe anemia (Hb < 10 g/dL) but a higher risk of BV.

Introduction

Uterine adenomyosis is characterized by the ectopic presence of endometrial glandular tissues within the myometrium and affects approximately 20% of women during their reproductive ages (1). It is associated with a variety of distressing symptoms, including cyclical pelvic pain, dyspareunia, abnormal uterine bleeding, and infertility. Conservative treatment strategies, aimed at preserving fertility and alleviating symptoms, include levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (LNG-IUD), oral progestins, gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues, combined oral contraceptives, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (2).

Among these options, LNG-IUD and oral progestins are commonly accepted, and their common adverse effects including abnormal menstrual bleeding, hypoestrogenic symptoms, headache, weight gain, and bone loss have been reported in previous studies, as summarized in Supplementary Table S1 (3–8). Intrauterine device (IUD), particularly traditional copper IUD, have been linked to a higher incidence of bacterial vaginosis (BV) (9), whereas evidence regarding LNG-IUD remains inconsistent. In contrast, oral contraceptives containing progestins have been linked to a reduced risk of BV (10). With respect to pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), LNG-IUD have been shown to carry a lower risk than copper IUD (11), while oral contraceptives may also reduce PID risk, potentially due to their effects on thickening cervical mucus and decreasing menstrual flow (12, 13). However, a direct comparative evidence between LNG-IUD and oral progestins in this context is lacking.

In this study, we conducted a retrospective analysis using real-world data to compare the risks of PID and BV in adenomyosis patients treated with either LNG-IUD or oral norethindrone (primary outcomes). Secondary outcomes included risks of severe anemia (Hb < 10 g/dL), breast cancer, mood disorder, and cancer antigen 125 (CA-125) >35 U/mL.

Methods

This retrospective, multi-institutional study utilized de-identified electronic health record data from the TriNetX Research Network (Cambridge, MA, USA), a global federated health research platform that aggregates real-time electronic health record data from healthcare organizations. Data for this study were initially extracted on April 28, 2025 from a cohort comprising approximately 126 million patients across 96 healthcare organizations primarily located in the United States and Europe. Additional subgroup analyses were performed using data extracted on November 7, 2025. Because the TriNetX database continuously updates with newly available records, the total number of patients may vary across different data extractions. The extraction dates for each dataset are provided in the footnotes of the corresponding tables. The TriNetX platform complies with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and has received a waiver from the Western Institutional Review Board due to its use of de-identified data.

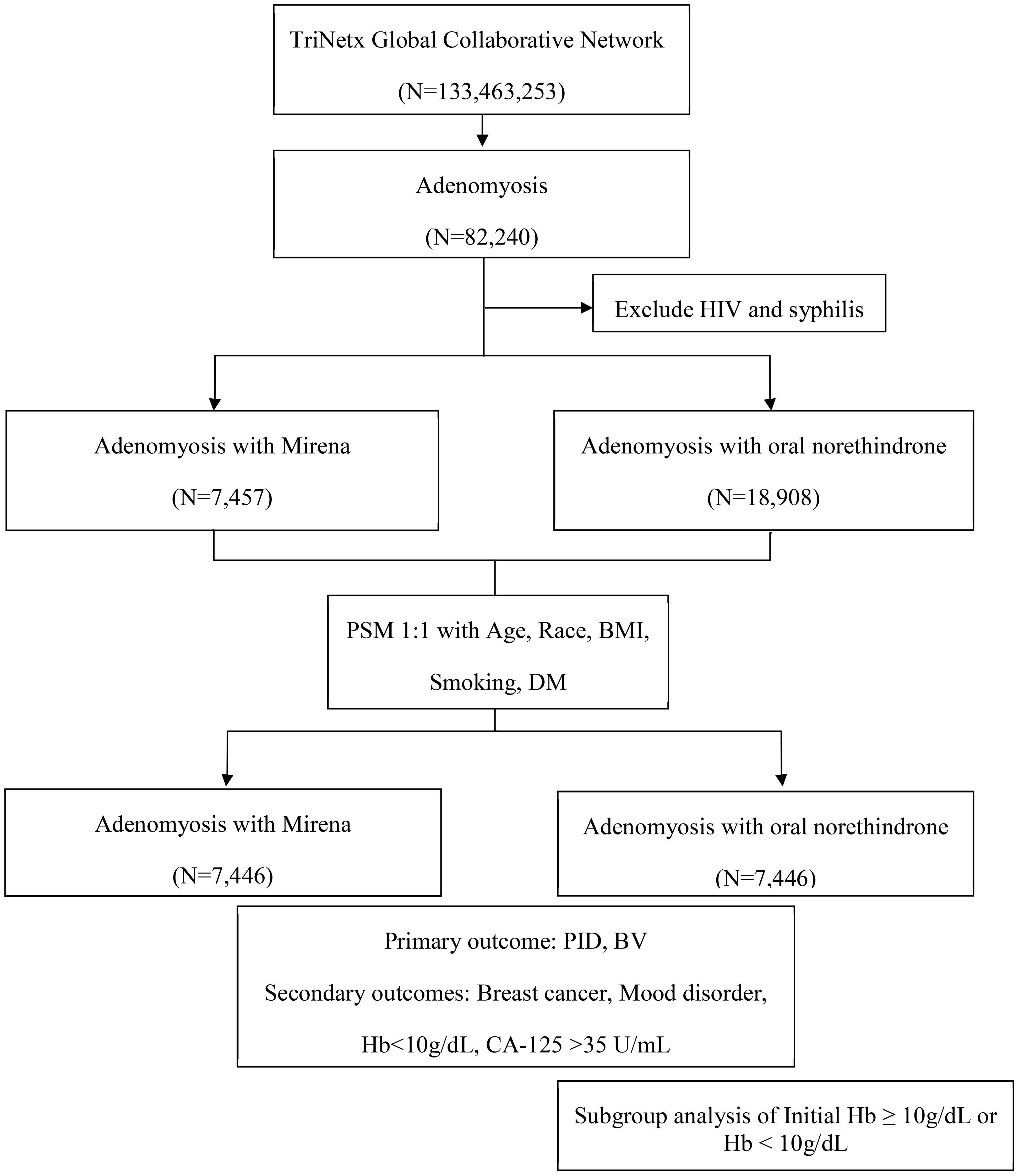

The study design and patient selection algorithm are illustrated in Figure 1. Female patients diagnosed with adenomyosis (ICD-10-CM: N80.0, N80.03) were included, excluding those with a prior history of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (ICD-10-CM: B20) or syphilis (ICD-10-CM: A53.9, A53). The participants were categorized into two treatment groups based on the first recorded prescription or procedure code following diagnosis: LNG-IUD insertion (Mirena, RxNorm: 6373; HCPCS: J7298) or oral norethindrone (Norina, RxNorm: 7514).

Figure 1. Flowchart of patient selection from the TriNetX research network. BMI, body mass index; BV, bacterial vaginosis; CA-125, cancer antigen 125; DM, diabetes mellitus; Hb, hemoglobin; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; PID, pelvic inflammatory disease.

To minimize confounding factors, propensity score matching (PSM) was applied using the integrated TriNetX tool to create 1:1 matched groups with similar baseline characteristics. Patients were matched based on age, ethnicity, body mass index (BMI), smoking status (ICD-10-CM: Z72.0), and diabetes mellitus (ICD-10-CM: E08–E13, excluding E10). Ethnicity was categorized as White, Black or African American, Asian, and others or unknown. Baseline characteristics between the treatment groups were compared using chi-square test for categorical variables and t-test for continuous variables. A greedy nearest-neighbor matching algorithm with a caliper width of 0.1 pooled standard deviations was employed to optimize the quality of matching. A standardized mean difference (SMD) of less than 0.1 was considered indicative of a negligible difference between groups, reflecting successful matching.

The analysis period began 1 day after the initial administration of the prescribed treatment, either the LNG-IUD or oral norethindrone, and extended for 10 years. The primary outcomes of interest were the diagnoses of PID (N73, N73.1, A56.11, N73.0, A49.3, A56.19, N73.9, A74.89, N73.8, N73.2, and N97.8) and BV (B96.8 and N76.0). The secondary outcomes included mood disorder (ICD-10-CM: F32.0, F32.1, F32.2, F32.4, F32.5, F32.8, and F32.9), breast cancer (ICD-10-CM: C50, C50.91, and C50.919), Hb <10 g/dL, and CA-125 ≥35 U/mL. Following PSM, the incidence of each outcome was evaluated over a 10-year follow-up period using hazard ratio (HR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). A two-sided p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses. Subgroup analyses were conducted to evaluate how the risk of each outcome varied according to anemia status (Hb ≥ 10 g/dL or < 10 g/dL), serving as an indirect indicator of the severity of adenomyosis.

Results

Baseline characteristics before and after matching

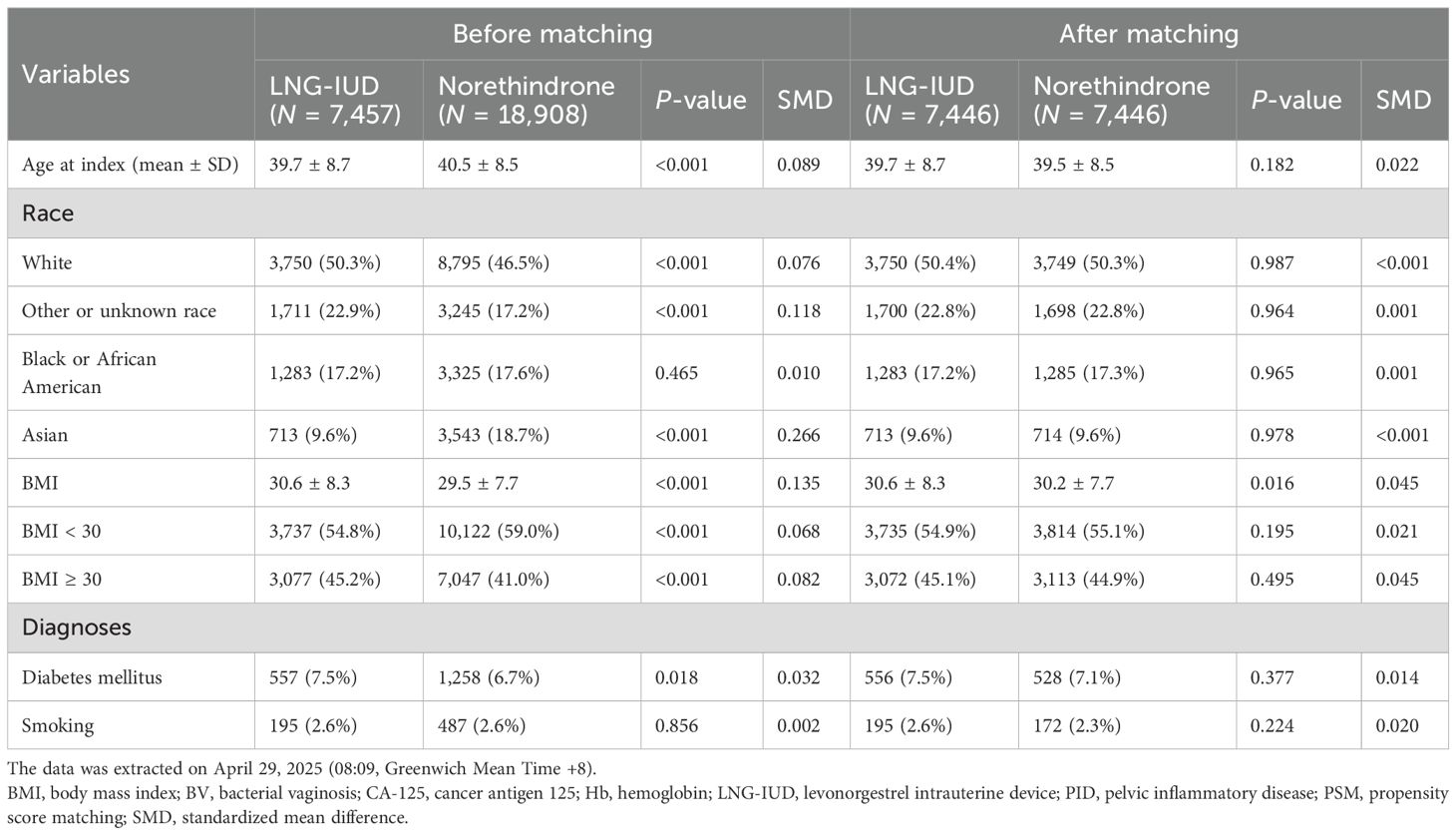

Prior to PSM, the LNG-IUD group comprised 7,457 individuals, while the oral norethindrone group included 18,908 individuals. As shown in Table 1, after PSM, both groups were matched 1:1, resulting in 7,446 patients in each group for subsequent analyses. The average age across both cohorts was approximately 40 years, and the mean BMI was around 30. In terms of race, the majority of patients were white, accounting for 50.3% in the LNG-IUD group and 46.5% in the norethindrone group. Regarding comorbidities, approximately 7% of patients were diagnosed with diabetes mellitus and 2.6% reported tobacco use. The matching process was considered successful as indicated by SMD below 0.1 for all matched variables, as shown in Table 1.

Incidence of outcomes between LNG-IUD and oral norethindrone group

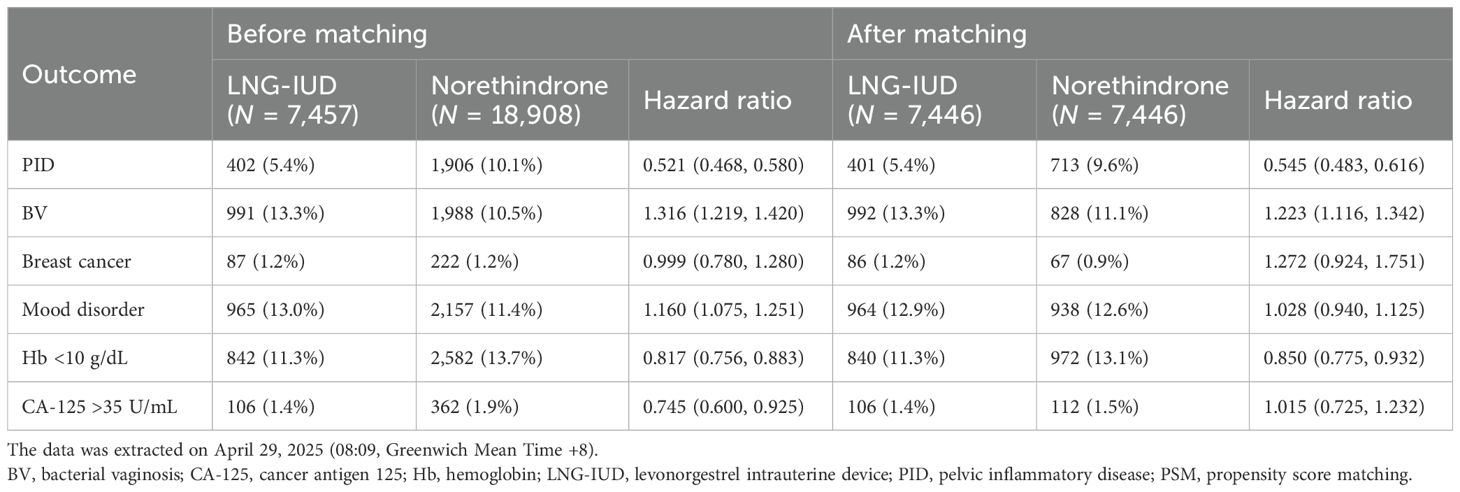

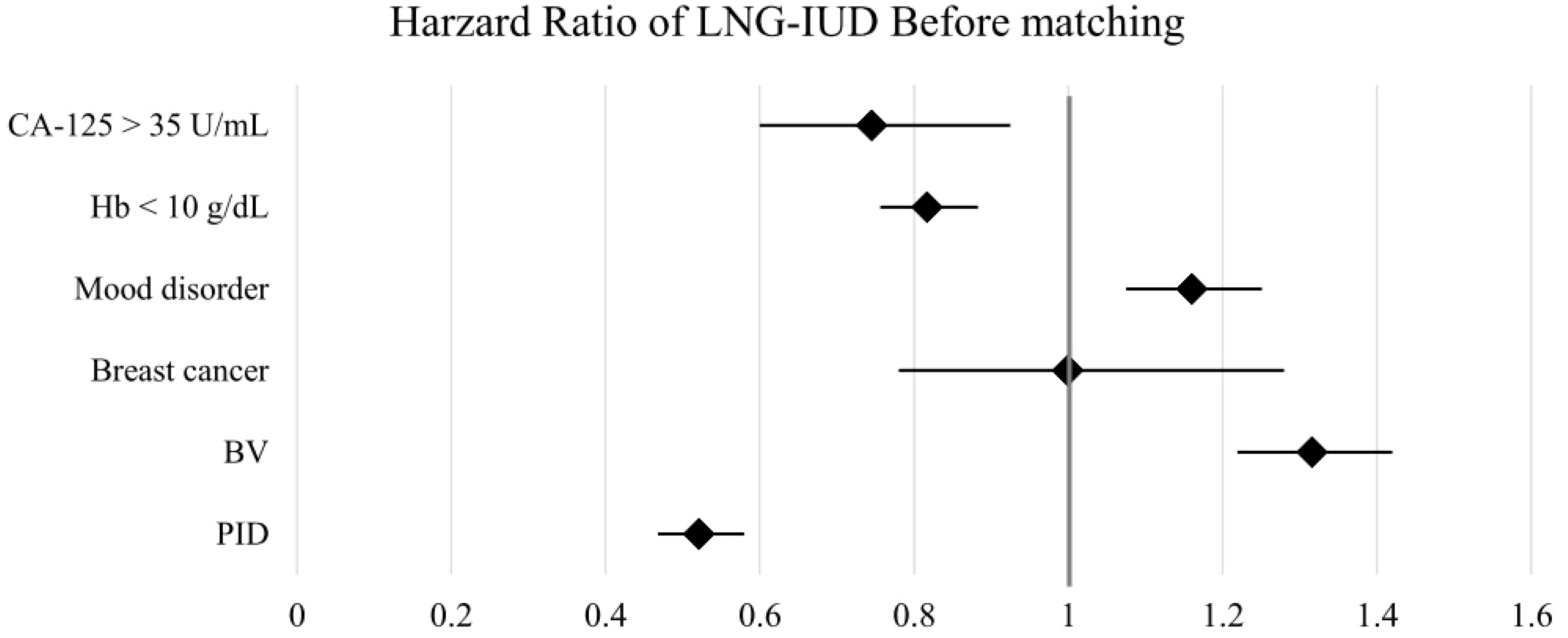

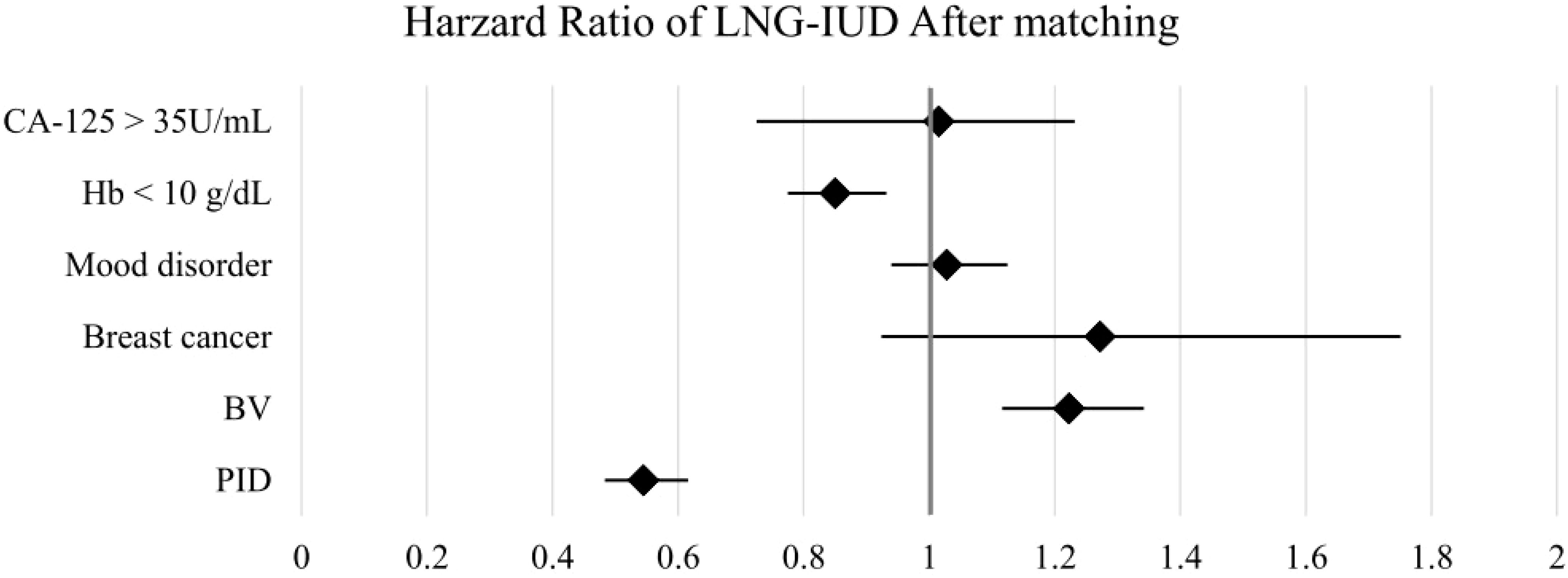

The HR for clinical outcomes were presented in Table 2 and Figures 2, 3. Following PSM, the LNG-IUD group demonstrated a significantly lower risk of PID (HR 0.545; 95% CI 0.483–0.616) and Hb < 10 g/dL (HR 0.850; 95% CI 0.775–0.932) compared with the norethindrone group. Conversely, the risk of BV was higher in LNG-IUD group (HR 1.223; 95% CI 1.116–1.342). No statistically significant differences were observed between the two groups for other outcomes, including breast cancer, mood disorder, and CA-125 ≥35 U/mL.

Figure 2. Forest plots of outcomes before matching. BV, bacterial vaginosis; CA-125, cancer antigen 125; Hb, hemoglobin; LNG-IUD, levonorgestrel intrauterine device; PID, pelvic inflammatory disease; PSM, propensity score matching.

Figure 3. Forest plots of outcomes after matching. BV, bacterial vaginosis; CA-125, cancer antigen 125; Hb, hemoglobin; LNG-IUD, levonorgestrel intrauterine device; PID, pelvic inflammatory disease; PSM, propensity score matching.

Subgroup analysis by hemoglobin level

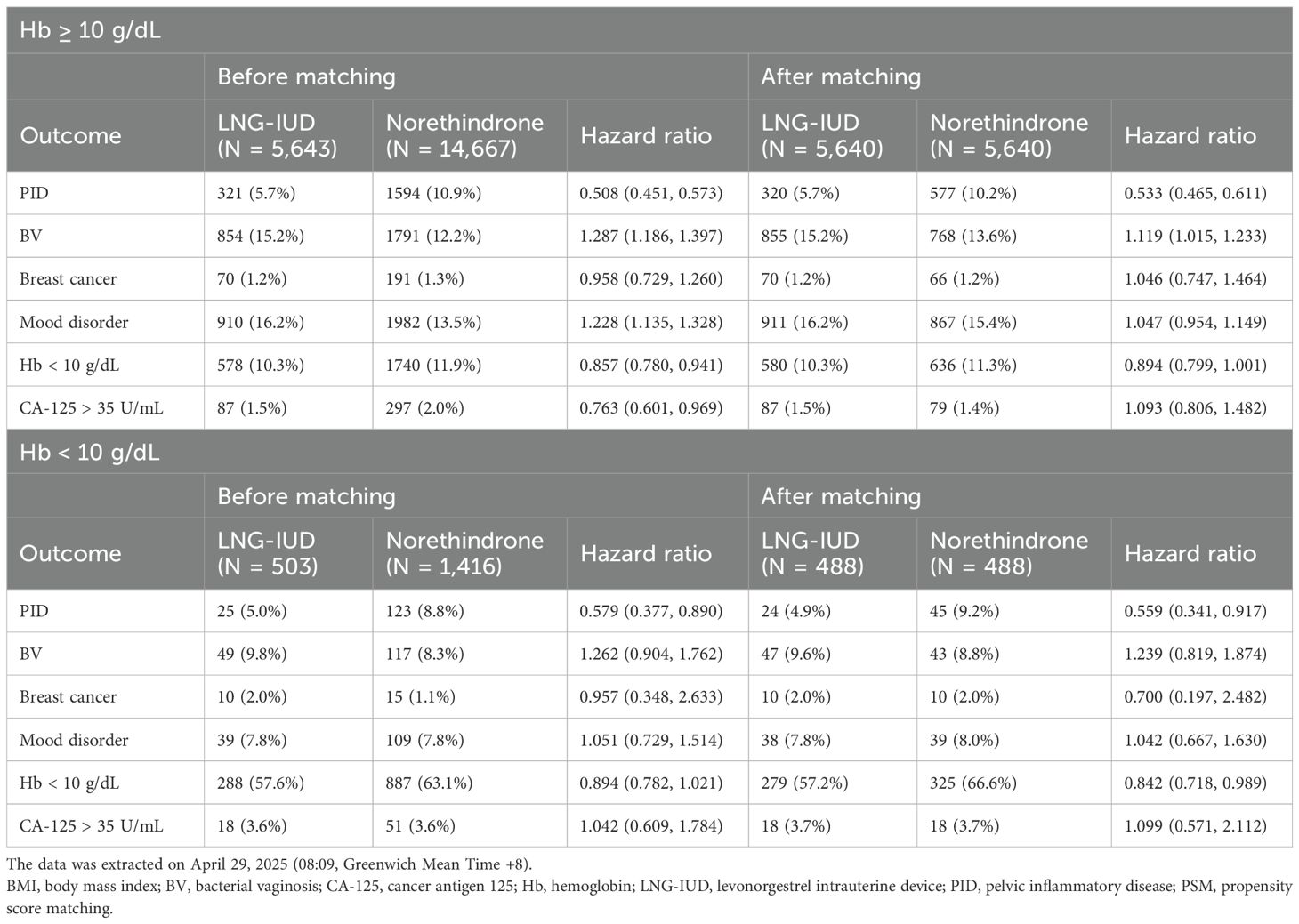

The baseline characteristics of patients stratified by Hb ≥10 g/dL or <10 g/dL are presented in Supplementary Tables S2, S3. The total number of patients in these subgroups was smaller than in the overall cohort because hemoglobin data were not available for all individuals. After PSM, the number of patients in both the LNG-IUD and oral norethindrone groups was 5,640 for the Hb ≥10 g/dL subgroup and 488 for the Hb <10 g/dL subgroup, respectively, as shown in Table 3. In the Hb ≥10 g/dL subgroup, the LNG-IUD group showed a significantly lower risk of PID compared with the norethindrone group (HR 0.533; 95% CI 0.465–0.611). However, the risk of BV was significantly higher in the LNG-IUD group (HR 1.119; 95% CI 1.015–1.233). No statistically significant differences were observed between the two groups for breast cancer, mood disorder, or CA-125 ≥35 U/mL. In the Hb <10 g/dL subgroup, which had a smaller sample size, the LNG-IUD group similarly exhibited a significantly reduced risk of PID (HR 0.559; 95% CI 0.341–0.917). Although BV showed a similar trend toward a higher incidence in the LNG-IUD group, the difference did not reach statistical significance (HR 1.239; 95% CI 0.819–1.874). For all other outcomes, including breast cancer, mood disorder, and elevated CA-125 levels, no statistically significant differences were observed between the treatment groups.

Discussion

Most existing studies comparing LNG-IUD and oral progestins have been conducted in the context of contraception (9, 10, 14). More recently, a meta-analysis evaluated the efficacy and adverse effects of LNG-IUD for adenomyosis, both as monotherapy and in combination with other treatments (15). Our study demonstrated a novel real-world study directly comparing LNG-IUD and oral norethindrone in patients with adenomyosis. Unlike contraception, the management of adenomyosis involves long-term treatment, often from a woman’s 20s through her 50s, and requires careful clinical counseling regarding both efficacy and safety (1, 2). Among these concerns, the potential risk of breast cancer is frequently raised by patients. The LNG-IUD provides a convenient, locally acting therapy; however, some patients report abdominal or vaginal discomfort following insertion. This raises important clinical questions about whether the risks of PID, BV, breast cancer, mood disorder, and disease control differ between LNG-IUD and oral norethindrone use. In our study, LNG-IUD use was associated with a reduced risk of PID and severe anemia but an increased risk of BV compared with oral norethindrone after PSM.

We observed a reduced risk of PID and severe anemia (Hb < 10 g/dL) among adenomyosis patients treated with LNG-IUD compared with those receiving oral norethindrone after PSM. The association between LNG-IUD use and PID remains controversial, with existing research limited by methodological constraints (14). While copper IUDs have been linked to an increased risk of PID (16), LNG-IUD appears to confer a lower risk compared with copper IUDs (11); however, no prior studies have directly compared LNG-IUD with oral norethindrone in this context. We hypothesize that levonorgestrel released by the LNG-IUD may exert a protective effect due to its anti-inflammatory and endometrial-thinning properties. On the other hand, clinical trials have further demonstrated that LNG-IUD significantly improves Hb levels in patients with adenomyosis, with one randomized trial showing comparable hematologic outcomes to hysterectomy but superior psychological and social well-being (17). Another randomized study found LNG-IUD to be more effective than combined oral contraceptives in reducing menstrual blood loss (18). Our findings are consistent with these results, confirming a greater improvement in anemia among adenomyosis patients treated with LNG-IUD.

Previous research has shown that norethindrone does not significantly alter the mucosal microbial environment (19), and further studies have reported a negative association between BV and the use of oral contraceptives (20, 21). In contrast, BV has been frequently linked to copper IUD use (9, 22), whereas the evidence regarding LNG-IUD remains limited and inconsistent (19). Short-term LNG-IUD use has been reported to transiently decrease lactobacillary dominance and increase BV, with risks returning to baseline after 1–5 years (23). Comparative analyses further suggest that copper IUDs are associated with higher rates of BV and Actinomyces species, while LNG-IUD are more often linked to candidiasis (24). Although most available data are derived from contraceptive populations, our findings similarly indicate an elevated risk of BV with LNG-IUD use compared with oral norethindrone in adenomyosis patients.

The associations of breast cancer and mood disorder remain major concerns among users of hormonal therapy. Although LNG-IUD is primarily locally acting, prior studies have reported that both oral combined estrogen–progestin contraceptives and LNG-IUD are associated with an increased risk of breast cancer compared with non-users, with risk rising in proportion to duration of use (25). A meta-analysis further suggested that LNG-IUD use may increase breast cancer risk irrespective of age or indication, with a stronger effect observed in older women (26). In contrast, our 10-year follow-up analysis found no significant difference in breast cancer incidence between LNG-IUD and oral norethindrone users.

Regarding mood disorder, the available evidence remains inconsistent. While most studies have not demonstrated a consistent adverse impact of hormonal contraceptives on mood in the general population, certain individuals may be particularly susceptible to mood-related side effects (27). LNG-IUD, in particular, have been linked to an elevated risk of depression in a UK cohort study (28), and it has been suggested that patients should be counseled regarding the potential risk of psychiatric symptoms prior to use (29). In our study, however, no significant difference in the incidence of mood disorder was observed between LNG-IUD and oral norethindrone users.

This study provided clinically relevant information to guide the counseling and management of patients with adenomyosis. For individuals with a history of recurrent BV, oral norethindrone may be the preferred treatment option. Conversely, in patients with a prior history of PID or those experiencing severe menorrhagia, LNG-IUD may be more appropriate. Regarding concerns about the risk of breast cancer and mood disorder, our findings indicated no significant differences between the two treatment modalities; however, according to previous studies, appropriate counseling of the breast cancer and psychiatric risks is essential before prescribing these medications.

In addition to these considerations, patient-specific factors should also guide treatment selection. Previous studies have reported a higher risk of LNG-IUD expulsion in obese patients (30), suggesting that norethindrone may be more suitable for individuals with higher BMI. Smoking has been associated with an increased risk of bacterial vaginosis (31), further supporting the use of oral norethindrone in smokers. Conversely, for younger women who also require contraception, the LNG-IUD may be preferred for its dual therapeutic and contraceptive benefits.

Our study has several limitations that should be acknowledged, most of which are inherent to the use of the TriNetX database. Because imaging data are not included in TriNetX, parameters such as uterine size and myometrial thickness, which may influence treatment efficacy and IUD expulsion rates, could not be evaluated. As a retrospective analysis, this study cannot establish causal relationships between treatments and outcomes, and residual confounding may remain despite propensity score matching. Detailed information on medication dosage, adherence, and treatment duration was also unavailable, which may have affected the accuracy of outcome assessment. Given that the approved duration of LNG-IUD use is 5 years, we additionally performed a 5-year follow-up analysis, which demonstrated trends consistent with those observed in the original cohort. The results are presented in Supplementary Tables S4, S5. In addition, while menorrhagia is a predominant symptom of adenomyosis, data on LNG-IUD removal, expulsion, or discontinuation were unavailable, potentially reducing the accuracy of outcome assessment. Furthermore, reliance on standardized coding systems (ICD and RxNorm) may lead to misclassification or reporting delays, particularly for conditions such as BV or mood disorder that may be underdiagnosed in clinical practice.

Future prospective studies with standardized, protocol-based follow-up assessments are warranted to provide more precise and clinically informative results. In addition, we conducted an extended exploratory analysis including patients diagnosed with both adenomyosis and concomitant endometriosis to further elucidate treatment outcomes in this subgroup. The preliminary findings, presented in Supplementary Tables S6, S7, demonstrated trends consistent with those observed in the original cohort.

Despite these limitations, this study provides an advantageous real-world evidence comparing two widely used conservative treatments for adenomyosis. The large sample size, diverse patient population, and rigorous application of PSM strengthen the validity of our findings and support their relevance for clinical decision-making.

Conclusion

In patients with adenomyosis, treatment with LNG-IUD, compared with oral norethindrone, was associated with a reduced risk of PID and severe anemia (Hb < 10 g/dL) but an increased risk of BV. No significant differences were observed between the two treatments regarding breast cancer, mood disorder, or CA-125 >35 U/mL.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Institutional Review Board of Taichung Veterans General Hospital, under approval number CE25848A. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The ethics committee/institutional review board waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin, because the data is anonymized.

Author contributions

S-YN: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Y-CY: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. Y-HS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. J-JT: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research project is funded by TCVGH-1136401E.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Biostatistics Task Force of Taichung Veteran General Hospital for their assistance.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fendo.2025.1703310/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Donnez J, Donnez O, and Dolmans MM. Introduction: Uterine adenomyosis, another enigmatic disease of our time. Fertil Steril. (2018) 109:369–70. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2018.01.035

2. Vannuccini S, Luisi S, Tosti C, Sorbi F, and Petraglia F. Role of medical therapy in the management of uterine adenomyosis. Fertil Steril. (2018) 109:398–405. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2018.01.013

3. Dhamangaonkar PC, Anuradha K, and Saxena A. Levonorgestrel intrauterine system (Mirena): An emerging tool for conservative treatment of abnormal uterine bleeding. J Midlife Health. (2015) 6:26–30. doi: 10.4103/0976-7800.153615

4. Santos M, Hendry D, Sangi-Haghpeykar H, and Dietrich JE. Retrospective review of norethindrone use in adolescents. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. (2014) 27:41–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2013.09.002

5. Wang J, Deng K, Li L, Dai Y, and Sun X. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system vs. systemic medication or blank control for women with dysmenorrhea: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Glob Womens Health. (2022) 3:1013921. doi: 10.3389/fgwh.2022.1013921

6. Toivonen J, Luukkainen T, and Allonen H. Protective effect of intrauterine release of levonorgestrel on pelvic infection: three years’ comparative experience of levonorgestrel-and copper-releasing intrauterine devices. Obstetrics Gynecology. (1991) 77:261–4. doi: 10.1097/00006250-199102000-00019

7. Dal’Ava N, Bahamondes L, Bahamondes MV, de Oliveira Santos A, and Monteiro I. Body weight and composition in users of levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system. Contraception. (2012) 86:350–3. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.01.017

8. Dean J, Kramer KJ, Akbary F, Wade S, Huttemann M, Berman JM, et al. Norethindrone is superior to combined oral contraceptive pills in short-term delay of menses and onset of breakthrough bleeding: a randomized trial. BMC Womens Health. (2019) 19:70. doi: 10.1186/s12905-019-0766-6

9. Peebles K, Kiweewa FM, Palanee-Phillips T, Chappell C, Singh D, Bunge KE, et al. Elevated risk of bacterial vaginosis among users of the copper intrauterine device: A prospective longitudinal cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. (2021) 73:513–20. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa703

10. Bradshaw CS, Vodstrcil LA, Hocking JS, Law M, Pirotta M, Garland SM, et al. Recurrence of bacterial vaginosis is significantly associated with posttreatment sexual activities and hormonal contraceptive use. Clin Infect Dis. (2013) 56:777–86. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis1030

11. Toivonen J. Protective effect of intrauterine release of levonorgestrel on pelvic infection_three years’ comparative experience of levonorgestrel- and copper-releasing intrauterine devices. Obstetrics Gynecology. (1991) 77:261–4. doi: 10.1097/00006250-199102000-00019

12. Henry-Suchet J. Hormonal contraception and pelvic inflammatory disease. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. (1997) 2:263–7. doi: 10.3109/13625189709165305

13. Burkman RT Jr. Noncontraceptive effects of hormonal contraceptives: bone mass, sexually transmitted disease and pelvic inflammatory disease, cardiovascular disease, menstrual function, and future fertility. Am J Obstet Gynecol. (1994) 170:1569–75. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(12)91817-7

14. Hubacher D, Grimes DA, and Gemzell-Danielsson K. Pitfalls of research linking the intrauterine device to pelvic inflammatory disease. Obstet Gynecol. (2013) 121:1091–8. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31828ac03a

15. Zhang B, Shi J, Gu Z, Wu Y, Li X, Zhang C, et al. The role of different LNG-IUS therapies in the management of adenomyosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. (2025) 23:23. doi: 10.1186/s12958-025-01349-4

16. Grimes DA. Intrauterine devices and pelvic inflammatory disease: recent developments. Contraception. (1987) 36-1:97–109. doi: 10.1016/0010-7824(87)90063-1

17. Maruo T, Laoag-Fernandez JB, Pakarinen P, Murakoshi H, Spitz IM, and Johansson E. Effects of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system on proliferation and apoptosis in the endometrium. Hum Reproduction. (2001) 16:2103–08. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.10.2103

18. Maia H Jr., Maltez A, Coelho G, Athayde C, and Coutinho EM. Insertion of mirena after endometrial resection in patients with adenomyosis. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. (2003) 10:512–6. doi: 10.1016/s1074-3804(05)60158-2

19. Balle C, Happel AU, Heffron R, and Jaspan HB. Contraceptive effects on the cervicovaginal microbiome: Recent evidence including randomized trials. Am J Reprod Immunol. (2023) 90:e13785. doi: 10.1111/aji.13785

20. Shoubnikova M. Contraceptive use in women with bacterial vaginosis. Contraception. (1997) 55:355–8. doi: 10.1016/s0010-7824(97)00044-9

21. Vodstrcil LA, Hocking JS, Law M, Walker S, Tabrizi SN, Fairley CK, et al. Hormonal contraception is associated with a reduced risk of bacterial vaginosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One. (2013) 8:e73055. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073055

22. Achilles SL, Austin MN, Meyn LA, Mhlanga F, Chirenje ZM, and Hillier SL. Impact of contraceptive initiation on vaginal microbiota. Am J Obstet Gynecol. (2018) 218:622 .e1– e10. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.02.017

23. Donders GGG, Bellen G, Ruban K, and Van Bulck B. Short- and long-term influence of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (Mirena®) on vaginal microbiota and Candida. J Med Microbiol. (2018) 67:3:308–13. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000657

24. Eleuterio JJ, Giraldo PC, Silveira Goncalves AK, and Nunes Eleuterio RM. Liquid-based cervical cytology and microbiological analyses in women using cooper intrauterine device and levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. (2020) 255:20–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.09.051

25. Morch LS, Skovlund CW, Hannaford PC, Iversen L, Fielding S, and Lidegaard O. Contemporary hormonal contraception and the risk of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. (2017) 377:2228–39. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1700732

26. Conz L, Mota BS, Bahamondes L, Teixeira Doria M, Francoise Mauricette Derchain S, Rieira R, et al. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system and breast cancer risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. (2020) 99:970–82. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13817

27. Robakis T, Williams KE, Nutkiewicz L, and Rasgon NL. Hormonal contraceptives and mood: review of the literature and implications for future research. Curr Psychiatry Rep. (2019) 21:57. doi: 10.1007/s11920-019-1034-z

28. Slattery J, Morales D, Pinheiro L, and Kurz X. Cohort study of psychiatric adverse events following exposure to levonorgestrel-containing intrauterine devices in UK general practice. Drug Saf. (2018) 41:951–8. doi: 10.1007/s40264-018-0683-x

29. Elsayed M, Dardeer KT, Khehra N, Padda I, Graf H, Soliman A, et al. The potential association between psychiatric symptoms and the use of levonorgestrel intrauterine devices (LNG-IUDs): A systematic review. World J Biol Psychiatry. (2023) 24:457–75. doi: 10.1080/15622975.2022.2145354

30. Masten M, Yi H, Beaty L, Hutchens K, Alaniz V, Buyers E, et al. Body mass index and levonorgestrel device expulsion in adolescents and young adults. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. (2024) 37:407–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2024.03.001

Keywords: adenomyosis, anemia, bacterial vaginosis, levonorgestrel intrauterine device, norethindrone, pelvic inflammatory disease, progesterone

Citation: Niu S-Y, Yi Y-C, Shih Y-H and Tseng J-J (2025) Risks of pelvic inflammatory disease and bacterial vaginosis in adenomyosis patients using levonorgestrel intrauterine device or oral norethindrone. Front. Endocrinol. 16:1703310. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2025.1703310

Received: 11 September 2025; Accepted: 13 November 2025; Revised: 08 November 2025;

Published: 01 December 2025.

Edited by:

Cao Li, Capital Medical University, ChinaReviewed by:

Francesco Giuseppe Martire, University of Rome Tor Vergata, ItalyLei Han, Binzhou Medical University Hospital, China

Copyright © 2025 Niu, Yi, Shih and Tseng. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jenn-Jhy Tseng, dGpqMTAxOEBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Szu-Yun Niu

Szu-Yun Niu Yu-Chiao Yi1,2

Yu-Chiao Yi1,2 Yu-Hsiang Shih

Yu-Hsiang Shih Jenn-Jhy Tseng

Jenn-Jhy Tseng